Abstract

We previously demonstrated that induction of splenic cytokine and chemokine secretion in response to Streptococcus pneumoniae (Pn) is MyD88-, but not critically TLR2-dependent, suggesting a role for additional TLRs. In this study, we investigated the role of TLR2, TLR4 and/or TLR9 in mediating this response. We show that a single deficiency in TLR2, TLR4, or TLR9 has only modest, selective effects on cytokine and chemokine secretion, whereas substantial defects were observed in TLR2-/- × TLR9-/- and TLR2-/- × TLR4-/- mice, though not as severe as in MyD88-/- mice. Chloroquine, which inhibits the function of intracellular TLRs, including TLR9, completely abrogated detectable cytokine and chemokine release in spleen cells from TLR2-/- × TLR4-/- mice, similar to what is observed for mice deficient in MyD88. These data demonstrate significant synergy between TLR2 and both TLR4 and TLR9 for induction of the MyD88-dependent splenic cytokine and chemokine response to Pn.

Keywords: Toll-like receptor, Streptococcus pneumoniae, innate immunity, cytokine, chemokine, MyD88, bacteria, mouse, in vitro

Introduction

Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which recognize conserved moieties on pathogens, also known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns, are critical mediators of innate and adaptive immunity (1). TLRs are type I transmembrane proteins located at either the cell surface (TLRs 2 [with or without TLR1 or TLR6], 4, 5, 10, and 11) or in endosomes (TLRs 3, 7, 8, and 9) (2-4). Of the 11 identified TLRs, all but TLR3 and TLR4 are completely dependent upon the adaptor protein MyD88 for signaling (2, 5-8). TLR4 utilizes both MyD88 and another TLR adaptor protein, Trif/Ticam-1, for cell signaling, whereas TLR3-mediated signaling largely depends on Trif/Ticam-1 alone (9, 10). Upon ligand binding, MyD88 is recruited to the C-terminal domain of the TLR, resulting in a series of phosphorylation events that leads to the subsequent release of NF-κB into the nucleus and the transcription and production of various cytokines and chemokines (11-13).

We and others have previously shown that MyD88-/-, in distinct contrast to TLR2-/-, mice are markedly defective in their secretion of a number of cytokines and chemokines, and in their innate response to the Gram-positive bacterium, Streptococcus pneumoniae (Pn) (14-19). These striking differences suggested that TLRs in addition to TLR2 are critical for the MyD88-dependent response. There are a number of structures expressed by Pn that are recognized by TLRs. TLR2 has been reported to recognize lipoteichoic acid and peptidoglycan (20, 21), both of which are exposed at the bacterial surface, although more recent data suggests that peptidoglycan can also be sensed in a TLR2-independent manner by NOD proteins (22), mannose-binding lectin (23) and other receptors (24). Pneumolysin, a pore-forming cytoplasmic cytotoxin released by Pn upon its lysis, is a ligand for TLR4 (25). Both TLR2 and TLR4 mediate signaling at the cell surface of the responding cell (26). Pn also contains unmethylated CpG-containing DNA and single-stranded RNA that could potentially bind TLR9 and TLR7/8, respectively, in an intracellular, endosomal location (14, 26). In this regard, inhibition of endosomal acidification using agents such as chloroquine blocks TLR9- and TLR7/8-, but not TLR2- and TLR4-mediated signaling (27-29).

Although a number of the TLR ligands expressed by Pn have been identified, the collective role of the individual TLRs in mediating early cytokine and chemokine responses to Pn remains unknown. In this regard, we utilized the Q-plex™ mouse cytokine array to determine the in vitro secretion of a panel of 16 cytokines and chemokines from spleen cells, derived from wild-type and various TLR-deficient mice, in response to Pn. We demonstrate, for the first time, significant synergy between TLR2 and both TLR4 and TLR9 for induction of the pneumococcal, MyD88-dependent splenic cytokine and chemokine response.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C3H/HeJ (TLR4-mutant) and C3H/HeOuJ (wild-type), and B6129PF2/J mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD). MyD88-/- (C57BL/6 background), TLR2-/- (B6129 background), and TLR9-/- (B6129 background) mice were obtained from S. Akira (Osaka University, Osaka, Japan), and bred in our facility. TLR2-/- × TLR9-/- mice (B6129 background) were generated in our laboratory by crossing of TLR2-/- and TLR9-/- mice followed by crosses of resultant F1 mice. Spleen cells from appropriate, strain-matched wild-type controls were used in all experiments. The above mice were maintained in a pathogen-free environment at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences [U.S.U.H.S.] (Bethesda, MD). TLR2-/- × TLR4-/- mice (C57BL/6 background) were obtained from P. Matzinger (National Institutes of Health [N.I.H.], Bethesda, MD) and housed in a pathogen-free environment at the N.I.H. All mice were used between 6 and 8 wk of age. The experiments in this study were conducted according to the principles set forth in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, Institute of Animal Resources, National Research Council, Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (N.I.H.) 78-23.

Genotyping of mice

All mice used in these experiments were first confirmed by genotyping. DNA was prepared from mouse tail snips. The primers and conditions used for genotyping by PCR are as follows: 1) MyD88, A: 5′ TGG CAT GCC TCC ATC ATA GTT AAC C 3′; B: 5′ GTC AGA AAC AAC CAC CAC CAT GC 3′; C: 5′ ATC GCC TTC TAT CGC CTT CTT GAC G 3′ (94°C for 3 min; 35 cycles of: 94°C for 40 s, 65°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 50 s; and 72°C for 10 min. The amplified products are both about 500 bp); 2) TLR2 (B6129), A: 5′GTT TAG TGC CTG TAT CCA GTC AGT GCG 3′; B: 5′ AAT GGG TCA AGT CAA CAC TTC TCT GGC 3′; C: 5′ ATC GCC TTC TAT CGC CTT CTT GAC GAG 3′ (94°C for 1 min; 35 cycles of: 94°C for 30 s, 67°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min; and 72°C for 10 min. For detection of the mutated allele, we used primers B and C. For the wild-type allele, we used primers A and B. The amplified products are both about 1,200 bp); 3) TLR2 (C57BL/6), A: 5′ CAT TGA CAA CAT CAT CGA T 3′; B: 5′ GTA GGT CTT GGT GTT CAT T 3′ (94°C for 3 min; 12 cycles of: 94°C for 20 s, 64°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 35 s, followed by 25 cycles of: 94°C for 20 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 35 s; and 72°C for 2 min); 4) TLR4 (HeJ), A: 5′ TGT CAG TGG TCA GTG TGA TTG 3′; B: 5′ TCA GGT CCA AGT TGC CGT TTC 3′ (94°C for 5 min; 30 cycles of: 94°C for 1 min, 59°C for 30 s, and 70°C for 1 min; and 72°C for 2 min. The amplified product of the wild-type allele will appear as a double band at 300-350 bp, and that of the mutant allele will appear as a smaller and larger band at 300 and 400 bp); 5) TLR4 (C57BL/6), A: 5′ AGG ACT GGG TGA GAA ATG 3′; B: 5′ GAT TCG AGG CTT TTC CAT C 3′ (94°C for 3 min; 12 cycles of: 94°C for 20 s, 64°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 35 s, followed by 25 cycles of: 94°C for 20 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 35 s; and 72°C for 2 min); 6) TLR9, A: 5′ GAA GGT TCT GGG CTC AAT GGT CAT GTG 3′; B: 5′ GCA ATG GAA AGG ACT GTC CAC TTT GTG 3′; C: 5′ ATC GCC TTC TAT CGC CTT CTT GAC GAG 3′ (94°C for 1 min; 35 cycles of: 94°C for 30 s, 67°C for 30 s, and 74°C for 1 min; and 74°C for 10 min. For detection of the mutated allele, we used primers B and C. For the wild-type allele, we used primers A and B. The amplified products are both about 1,200 bp). All products were separated on a 1% agarose gel.

Reagents

Lipopeptide Pam3Cys-Ser-Lys4 (Pam3Cys) and purified lipopolysaccharide from E. coli K12 strain (LPS) were purchased from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA). Phosphorotriated 30-mer (CpG-ODN) (AAA AAA AAA AAA AAC GTT AAA AAA AAA AAA) and suppressive 16-mer (sODN) (CCT CAA GCT TGA GGG G) were synthesized in the Biomedical Instrumentation Center (U.S.U.H.S). Chloroquine was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Preparation of heat-killed Pn14

Streptococcus pneumoniae, capsular type 14 (Pn14), was prepared as previously described (30), heat inactivated by incubation at 60°C for 1h, then aliquoted at 1010 CFU/ml, and frozen at -80°C until their use.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of splenic cells

Red blood cells (RBC) were removed from spleen cell suspensions using ACK lysing buffer. Cells were stained with various combinations of the following mAbs which, unless indicated, were obtained from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA): PE-labeled anti-CD3ε (clone 145-2C11), anti-F4/80 (clone BM8, eBioscience, San Diego, CA), anti-NK-1.1 (clone PK136), anti-CD45R/B220 (clone RA3-6B2), or anti-CD11c (Caltag, Burlingame, CA); biotin-anti-IgM (clone R6.60.2) + FITC-streptavidin, FITC-anti-Thy1.2 [CD90.2] (clone 53-2.1), FITC-anti-I-Ab (clone AF6-120.1), biotin-anti-CD49b (clone DX5) + FITC-streptavidin, FITC-anti-CD11b (clone M1/70). The cells were sorted electronically using an EPICS-FACAria (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA), and the negative population of cells was collected for in vitro stimulation.

In vitro stimulation of cultured spleen cells

RBC-lysed spleen cell suspensions were cultured at a density of 5 × 105 cells/well in 0.5ml in 48-well tissue culture plates. After a 24 hr stimulation period with various doses of heat-inactivated Pn14 or TLR ligands, the cells were pelleted by centrifugation for 10 min at 1200 rpm and the supernatants were collected for measurement of cytokine and chemokine concentrations.

Measurement of cytokine concentrations in spleen cell culture supernatant

The Q-plex™ mouse cytokine array screen (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) was used, according to manufacturer's instructions, to measure the concentration of 16 cytokines and chemokines from culture supernatant (SN). Briefly, 1:2 serial dilutions were made of the various cytokines and chemokines of known concentration in order to generate a standard curve. Standards and samples were added to the plate for 1 hr at RT, and washed. The detection mix was added for 1 hr at RT and washed. HRP-streptavidin was added for 15 min at RT, washed, and the substrate mix was added and the plate was read for exposure times of 30 s to 1 min using a Fuji LAS-1000 CCD camera. Relative pixel intensity was determined with image analysis software provided by the manufacturer. The minimal level of detection, in pg/ml, of the cytokines and chemokines were as follows: IL-1α (7.8), IL-1β (30.6), IL-2 (5.6), IL-3 (6.9), IL-4 (7.2), IL-5 (3.1), IL-6 (8.8), IL-9 (162.5), IL-10 (30), IL-12 (0.7), MCP-1 (31.3), IFN-γ (62.5), TNF-α (26.9), MIP-1α (123.8), GM-CSF (5.6), RANTES (7.5). The concentration of IL-6 in culture SN or sera was also measured using an optimized standard sandwich ELISA (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Recombinant cytokines used as standards, as well as the capture monoclonal antibodies, biotinylated monoclonal antibodies used for detection and streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase (AP) were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Streptavidin-AP was used in combination with p-nitrophenyl phosphate, disodium (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) as substrate to detect the specific binding.

Statistics

Data are expressed as the arithmetic mean ± SEM of the individual values. Significance of the differences between groups was determined by Student's t test. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Spleen cells from MyD88-/- mice are markedly defective in secretion of multiple cytokines and chemokines in response to Pn14 in vitro

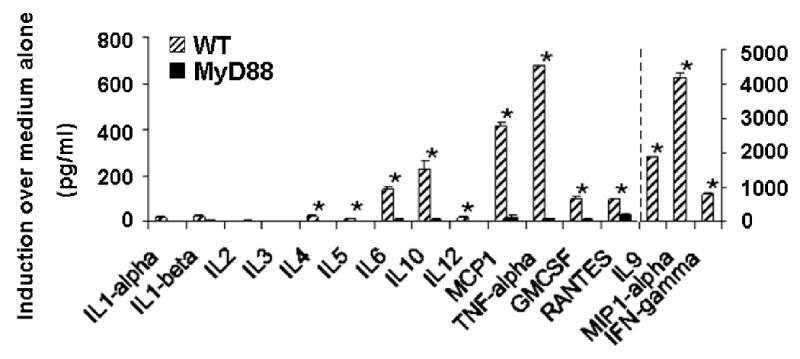

We previously reported that mice deficient in the TLR adaptor protein, MyD88 (MyD88-/-), are markedly defective in eliciting a number of cytokines and chemokines (i.e. IL-1, IL-6, IL-12, IFN-γ, TNF-α, MIP-1α and MCP-1) in response to heat-inactivated Pn14 in vitro and/or in vivo (14). To confirm and extend these findings to additional cytokines and chemokines, we used the ELISA-based chemiluminescent Q-plex™ mouse cytokine array screen that allows simultaneous quantitation of 16 cytokines and chemokines. As shown in Fig. 1, MyD88-/- mice indeed exhibit an essentially complete and global loss in their ability to elicit cytokine and chemokine responses to Pn14, arguing against a significant MyD88-independent component to the Pn14-mediated splenic response in vitro.

Figure 1. MyD88-/- spleen cells are defective in their ability to release innate cytokines and chemokines in vitro in response to Pn14.

Cytokine and chemokine concentrations in cell SN were measured by the Q-plex™ assay after 24 h of treatment of wild-type and MyD88-/- spleen cells in vitro with 107 cfu/ml of Pn14. The arithmetic mean of triplicates and SEM are shown. *p<0.05. Data represent one of two similar experiments.

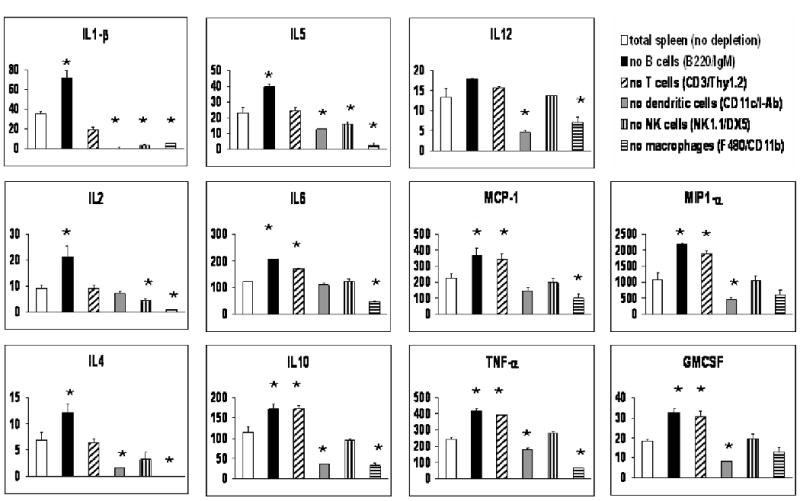

Cytokine and chemokine secretion by spleen cells in response to Pn14 in vitro is largely due to splenic macrophages and dendritic cells

We next wished to determine which specific cell populations in the spleen were responsible for the observed in vitro cytokine and chemokine response to Pn14. For this purpose, we used electronic cell sorting to individually remove T cells, B cells, NK cells, DCs or macrophages from whole spleen cells obtained from wild-type mice. Each cell population was identified on the basis of dual, positive staining with two distinct mAbs as illustrated in Figure 2. The various depleted spleen cell populations were then stimulated for 24 h in vitro with Pn14, and the concentration of secreted cytokines and chemokines was measured by the Q-plex™ assay and compared to sorted, whole spleen cells. We observed that macrophages and dendritic cells collectively contributed to most of the secreted cytokines and chemokines induced by Pn14 in vitro (Figure 2). Of note, neither B cells nor T cells made any measurable contribution to this early splenic response to Pn14, whereas NK cells appeared to play a significant role in induction of IL-1β and IL-2.

Figure 2. Macrophages and dendritic cells are responsible for most of the observed cytokine induction by WT splenic cells in vitro in response to Pn14.

Spleen cells from WT mice were stained with pairs of mAbs exhibiting the specificities shown in parentheses. Cells staining positively for both mAbs were subsequently removed by electronic cell sorting. The remaining cells were treated with 107 cfu/ml of Pn14 for 24 hr and cytokine and chemokine concentrations in culture SN were determined using the Q-plex™ assay. The arithmetic mean of triplicates and SEM are shown. *p<0.05 relative to “total spleen (no depletion)”. Data represent one of two similar experiments.

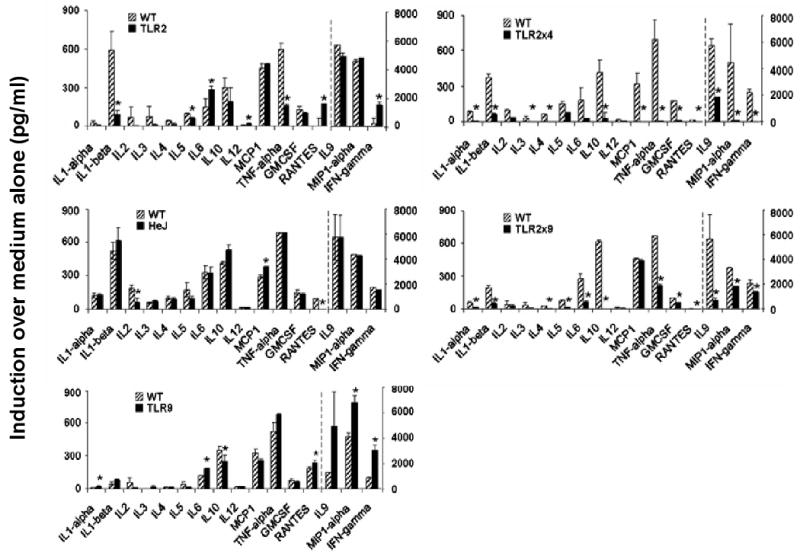

Dual, but not single, deficiencies in TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 result in significant, but not absolute, loss of the in vitro splenic cytokine and chemokine response to Pn14

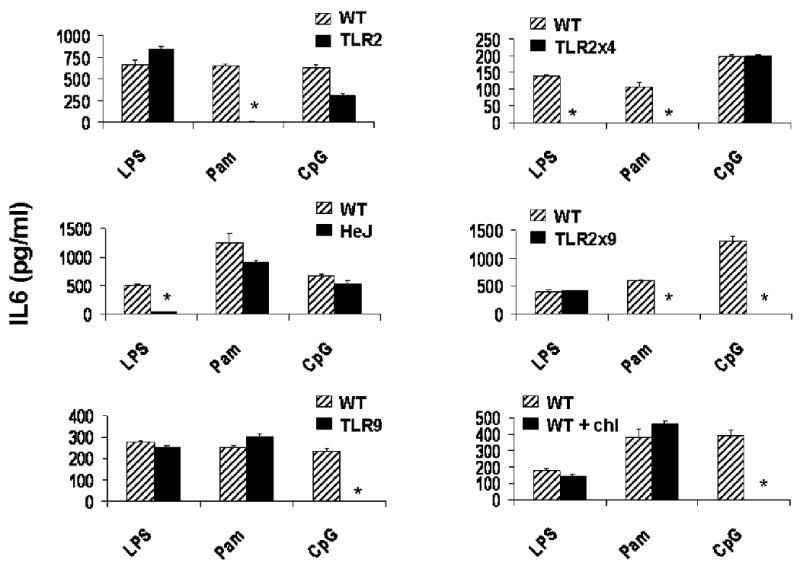

Of the MyD88-dependent TLRs, three have particular potential for mediating the initial recognition of Pn. Specifically, TLR2 recognizes lipoteichoic acid and peptidoglycan, TLR4 recognizes pneumolysin and TLR9 recognizes bacterial DNA containing unmethylated CpG motifs. In order to determine whether innate cytokine and chemokine induction by Pn is dependent upon signaling via TLR2, TLR4 and/or TLR9, we measured Pn14-induced cytokine and chemokine production by spleen cells from mice deficient in one or two of these receptors (i.e. TLR2-/-, C3H/HeJ (TLR4-mutant), TLR9-/-, TLR2-/- × TLR4-/- or TLR2-/- × TLR9-/-). TLR agonists (LPS [TLR4], Pam3Cys [TLR2], and CpG-ODN [TLR9]) were used as controls in each experiment to functionally confirm that mice were correctly genotyped (Figure 3). Additionally, we confirmed the ability of chloroquine, an inhibitor of endosomal acidification, to selectively block signaling via intracellular TLRs (e.g. TLR9) while leaving unaffected responses through the membrane TLRs (e.g. TLR4 and TLR2) (Figure 3). A single deficiency in TLR2, TLR4 or TLR9 caused only selective and relatively modest reductions or enhancements in cytokine and chemokine production by Pn14-activated spleen cells, with the exception of a substantial loss of IL-1β and TNF-α secretion in TLR2-/- mice (Figure 4, left panels). However, cytokine production was more dramatically and globally reduced in spleen cells from TLR2-/- × TLR4-/- and TLR2-/- × TLR9-/- mice, with the former exhibiting a more marked defect (Figure 4, right panels). These data strongly suggest that distinct TLRs synergize for optimal induction of innate release of multiple splenic cytokines and chemokines in response to Pn.

Figure 3. IL-6 secretion by various TLR-deficient and chloroquine-treated WT spleen cells in response to TLR agonists in vitro.

TLR agonists were used as controls in each experiment to ensure that the mice were correctly genotyped. LPS [TLR4] (1 ug/ml), Pam3Cys [TLR2] (Pam) (300 ng/ml) or CpG-ODN [TLR9] (4 ug/ml) were used to stimulate spleen cells from the indicated mice for 24 h in vitro. IL-6 concentrations were measured by ELISA. A representative result is shown. The arithmetic mean of triplicates and SEM are shown. *p<0.05

Figure 4. Spleen cells from mice with a double, but not single, deficiency in TLR2, 4 and/or 9, are defective in innate cytokine secretion in response to Pn14 in vitro.

Cytokine and chemokine concentrations in culture SN from spleen cells obtained from the indicated mice were measured using the Q-plex™ assay, following 24 hr of treatment with 107 cfu/ml of Pn14. The arithmetic mean of triplicates and SEM are shown. *p<0.05. Data represent one of two similar experiments.

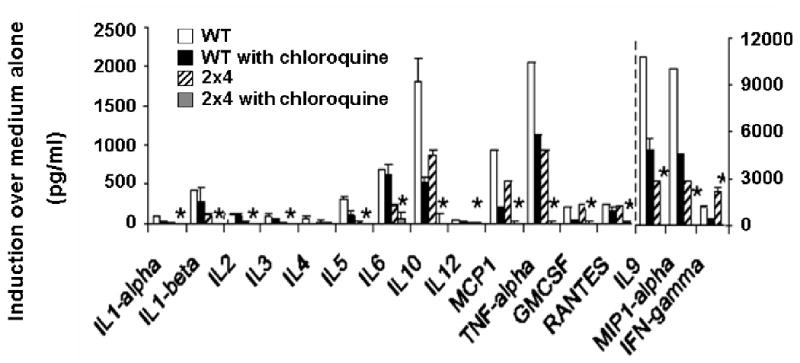

The combination of TLR2, TLR4 and an intracellular TLR(s) recapitulate the MyD88-/- phenotype for splenic cytokine and chemokine induction in response to Pn14

Since the defect in splenic cytokine and chemokine release, even in TLR2-/- × TLR4-/- mice was not as absolute as that observed in MyD88-/- mice, we wished to determine whether a combination of TLR2, TLR4, and intracellular TLR(s) [e.g. TLR9] could recapitulate the MyD88-/- phenotype. While bacterial DNA contains immunostimulatory CpG motifs that signal through TLR9, recent reports have shown that certain oligodeoxynucleotides rich in poly G or GC sequences are suppressive (sODN) and interfere with this interaction (31-34). The activity of sODN is dominant over TLR9 stimulation by CpG-ODN (35). However, we observed that sODN, used at optimal doses, failed to completely block CpG-ODN-induced cytokine and chemokine release in wild-type cells, and had no significant effect on Pn14-induced stimulation of spleen cells from either wild-type or TLR2-/- × TLR4-/- mice (data not shown).

The antimalarial drug chloroquine blocks endosomal acidification (36), a process specifically critical for productive interactions between intracellular TLRs (TLR3, TLR7/8, and TLR9) with their respective ligands (27-29). Treatment of spleen cells from TLR2-/- × TLR4-/- mice with chloroquine resulted in a complete loss of the detectable splenic cytokine and chemokine response to Pn14 in vitro (Figure 5), similar to what we observed using MyD88-/- mice (Figure 1). Of interest, whereas TLR9-/- mice exhibited no significant defect in splenic-mediated release (Figure 4), chloroquine treatment induced a modest but significant reduction in secretion of several cytokines and chemokines from wild-type spleen cells (Figure 5). These data suggest a possible role of other intracellular TLRs (e.g. TLR7 interaction with single-stranded RNA) (37, 38) in the Pn14-mediated response.

Figure 5. Chloroquine-treated TLR2-/- × TLR4-/-, like MyD88-/-, spleen cells are completely defective in cytokine and chemokine release in response to Pn14 in vitro.

Spleen cells from WT or TLR2-/- × TLR4-/- mice were stimulated in vitro for 24 h with 107 cfu/ml of Pn14 in the absence or presence of 3 ug/ml chloroquine. The arithmetic mean of triplicates and SEM are shown. *p<0.05 WT vs 2×4 with chloroquine. Data represent one of two similar experiments.

Discussion

We earlier reported that Pn induces a mixed type 1 and type 2 cytokine response in wild-type mice in vivo (39). Our more extended Q-plex™ cytokine analysis showing splenic release of mediators associated with type 1 (i.e. IL-12, IFN-γ, and MIP-1α) and type 2 (i.e. IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, and MCP-1) responses (40, 41) to Pn14 is consistent with this observation. Our previous observation that MyD88-/- mice exhibit a profound defect in cytokine and chemokine expression in response to heat-inactivated Pn14, whereas TLR2-/- mice are largely similar to wild-type mice (42), was confirmed in this more extensive analysis, and suggested that additional TLRs were critically involved in the innate immune response to this bacterium. Although Pn is known to express ligands for TLR2 (21), TLR4 (43) and TLR9 (44), the collective role of TLRs in Pn-induced innate cytokine and chemokine responses has remained unknown. Utilizing mice with single or dual deficiencies in these TLRs, we demonstrate significant synergy between TLR2 and TLR4, and TLR2 and TLR9, for Pn14-induced splenic cytokine and chemokine release. The ability of chloroquine (45), an inhibitor of signaling mediated by intracellular TLRs (i.e. TLR3, TLR7/8, and TLR9) (27), to completely abrogate cytokine and chemokine release by TLR2-/- × TLR4-/- spleen cells in response to Pn14, strongly suggests that TLR2, TLR4 and intracellular TLRs (i.e. TLR9 and possibly TLR7) collectively mediate the MyD88-dependent response in a synergistic fashion. In control experiments, chloroquine inhibited cytokine secretion by spleen cells in response to CpG-ODN (TLR9), but not LPS (TLR4) or Pam3Cys (TLR2), confirming its specificity of inhibition for intracytoplasmic, but not membrane, TLRs. Our choice of heat-inactivated Pn14 for these studies was to maintain consistency with our previously published work on in vivo anti-Pn adaptive immunity, where the use of live Pn was precluded because of its lethal effects on the host. Although heat inactivation might potentially destroy the activity of one or more Pn-derived TLR ligands, such as pneumolysin, our results nevertheless demonstrate, for the first time, that at least 3 distinct TLRs (membrane and intracytoplasmic) can synergize to promote the cytokine and chemokine response of splenic macrophages and dendritic cells to Pn. Of interest, mice lacking all TLR function (i.e. MyD88-/- × Trif-/- double knockout) continue to exhibit normal numbers of splenic macrophages and dendritic cells (Kasper Hoebe, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, personal communication), supporting a functional role of these TLRs in the Pn-mediated spleen cell response.

The pattern of cytokine and chemokine release from TLR9-/- spleen cells stimulated with Pn14 was essentially identical to that observed using wild-type cells. The in vitro splenic response to Pn14 was mediated largely by macrophages and dendritic cells, which readily internalize the bacteria. Hence, Pn14 has access to the endosomal compartment necessary for TLR9-mediated activation by CpG-containing DNA (46). In contrast to our findings, defects in cytokine production have been observed in TLR9-/-mice in response to heat-inactivated Brucella abortus (47), live Mycobacterium tuberculosis (48), and heat-inactivated Propionibacterium acnes (49). In this regard, DNA from distinct bacterial species express different proportions of unmethylated CpG which correlates directly with their TLR9-dependent immunostimulatory properties (44, 50). Relatively high concentrations of DNA, and thus large numbers of bacteria, are necessary to directly induce isolated TLR9-mediated effects (44, 51, 52). Of interest, the proportion of CpG-containing DNA in M. tuberculosis (12.7%), P. acnes (9.6%) (44) and B. abortus (9.2%) (47) is substantially higher than that found in Pn (2.7%) (44). This could explain the critical impact of an isolated deficiency in TLR9 on the innate responses to the former bacteria, in contrast to what we observe for Pn14.

TLR2-/-, in contrast to MyD88-/- mice, elicited a largely normal innate splenic cytokine response, although Q-plex™ analysis revealed a moderate reduction in secretion of IL-1β and TNF-α. In this regard, although TLR2-/- mice have been shown to be more susceptible to experimental Pn meningitis, a substantial part of the inflammatory response was found to be TLR2-independent (16, 17). Additionally, TLR2-/- mice inoculated intranasally with live Pn displayed only a modestly reduced inflammatory response in the lungs, and normal host immunity relative to wild-type mice, despite defective cytokine production from freshly isolated TLR2-/- alveolar macrophages (15). TLR2 was found, however, to be required for efficient clearance of Pn from the upper respiratory tract (53). The modest susceptibility of TLR2-/- mice to pneumococcal infection could, in part, be secondary to a defect in neutrophil phagocytosis and oxidative bactericidal activity (54). In contrast to TLR2-/- mice, MyD88-/- mice exhibit a more severe defect in innate cytokine production and host defense in experimental meningitis (18) and pneumonia models (19), as well as reduced clearance of pneumococci from the upper respiratory tract (19). Thus, in these models as well as in our own, TLR(s) in addition to TLR2 appear to be important for anti-pneumococcal innate immunity.

Mice deficient in TLR4 signaling (C3H/HeJ) (55), like mice with single genetic deficiencies in TLR2 or TLR9, exhibited an essentially normal innate splenic cytokine and chemokine response to Pn14. Pneumolysin, a cytoplasmic, cytotoxic protein expressed by Pn (56) and released upon autolysis, is a TLR4 ligand (43). However, heat inactivation destroys the cytotoxic and cytokine-inducing activity of pneumolysin (43, 57), arguing against a key role for pneumolysin in the in vitro splenic cytokine and chemokine response in our study. Of interest, as discussed below, spleen cells from TLR2-/- × TLR4-/-, but not TLR2-/- or C3H/HeJ, mice exhibited a striking reduction in secretion of cytokines and chemokines in response to heat-inactivated Pn14, suggesting that Pn expresses a novel, heat-resistant, TLR4 ligand in addition to the heat-sensitive pneumolysin.

TLR2-/- × TLR4-/-, and to a lesser extent TLR2-/- × TLR9-/-, mice exhibited striking reductions in secretion of splenic cytokines and chemokines in response to Pn14 in vitro, in contrast to mice deficient in only one of these TLRs, strongly suggesting functional synergy of the distinct TLRs. Our observations are consistent with the finding that TLR2 and TLR4 have differing cytoplasmic tails that mediate distinct, although overlapping, cytokine response patterns in macrophages (58-61) and dendritic cells (62). These data are in contrast to findings by Koedel, et al. in which IFN-γ-primed murine macrophages from mice with a dual deficiency in TLR2 and TLR4 signaling elicited a normal TNF-α response to Pn (16). Distinct TLR ligands have indeed been shown to act synergistically to promote release of inflammatory mediators by macrophages (63-65) and dendritic cells (66, 67). Consistent with these findings, whereas TLR4 alone appears to play a dominant role in macrophage release of IL-6 and TNF-α in response to a variety of Gram-negative bacteria, concomitant deficiency in both TLR2 and TLR4 resulted, synergistically, in a more defective phenotype (68). Likewise, whereas TLR4-/-, but not TLR2-/-, mice were more susceptible to acute infection with the Gram-negative bacterium, Salmonella typhimurium, TLR2-/- × TLR4-/- mice exhibited the most defective host response (69). Of interest, in one study, TLR2-/- × TLR4-/- macrophages elicited normal IL-6 and TNF-α responses to the Gram-positive bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus (68), although another study demonstrated reduced IL-6 and TNF-α in TLR2-/- macrophages in response to this bacterium (70). Synergy between TLR2 and TLR9 (48) and between TLR2 and TLR4 (71, 72) has also been observed in the host response to the intracellular bacterium, Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

In summary, these data indicate for the first time that innate immune cells exposed to Pn can integrate signals through at least 3 distinct TLRs (both extracellular and intracellular) to induce a rapid and synergistic cytokine and chemokine response that is critical role in the early host defense against Pn.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by N.I.H. grants 1R01 AI49192 and the U.S.U.H.S. Dean's Research and Education Endowment Fund.

Opinions and assertions contained herein are the private ones of the authors and are not to be construed as official or reflecting the views of the Department of Defense or the U.S.U.H.S.

We thank Shizuo Akira (Osaka University, Osaka, Japan) and Polly Matzinger (N.I.H., Bethesda, MD) for providing TLR9-/- and TLR2-/- breeding pairs, and TLR2-/- × TLR4-/- mice, respectively.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Janssens S, Beyaert R. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:637–646. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.4.637-646.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akira S, Takeda K, Kaisho T. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:675–680. doi: 10.1038/90609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishiya T, DeFranco AL. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19008–19017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311618200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parviz AN, Häcker H, Rutz M, Bauer S, Vabulas RM, Wagner H. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:1958–1968. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200207)32:7<1958::AID-IMMU1958>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akira S, Hoshino K, Kaisho T. J Endotoxin Res. 2000;6:383–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogel SN, Fitzgerald KA, Fenton MJ. Mol Interv. 2003;3:466–477. doi: 10.1124/mi.3.8.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeuchi O, Takeda K, Hoshino K, Adachi O, Ogawa T, Akira S. Int Immunol. 2000;12:113–117. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hacker H, Vabulas RM, Takeuchi O, Hoshino K, Akira S, Wagner H. J Exp Med. 2000;192:595–600. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.4.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, Hoshino K, Kaisho T, Sanjo H, Takeuchi O, Sugiyama M, Okabe M, Takeda K, Akira S. Science. 2003;301:640–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1087262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamamoto M, Sato S, Mori K, Hoshino K, Takeuchi O, Takeda K, Akira S. J Immunol. 2002;169:6668–72. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.6668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wesche H, Henzel WJ, Shillinglaw W, Li S, Cao Z. Immunity. 1997;7:837–847. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80402-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muzio M, Natoli G, Saccani S, Levrero M, Mantovani A. J Exp Med. 1998;187:2097–2101. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.12.2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muzio M, Ni J, Feng P, Dixit VM. Science. 1997;278:1612–1615. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan AQ, Chen Q, Wu ZQ, Paton JC, Snapper CM. Infect Immun. 2005;73:298–307. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.298-307.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knapp S, Wieland CW, van't Veer C, Takeuchi O, Akira S, Florquin S, van der Poll T. J Immunol. 2004;172:3132–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.3132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koedel U, Angele B, Rupprecht T, Wagner H, Roggenkamp A, Pfister HW, Kirschning CJ. J Immunol. 2003;170:438–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.1.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Echchannaoui H, Frei K, Schnell C, Leib SL, Zimmerli W, Landmann R. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:798–806. doi: 10.1086/342845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koedel U, Rupprecht T, Angele B, Heesemann J, Wagner H, Pfister HW, Kirschning CJ. Brain. 2004;127:1437–45. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albiger B, Sandgren A, Katsuragi H, Meyer-Hoffert U, Beiter K, Wartha F, Hornef M, Normark S, Normark BH. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:1603–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michelsen KS, Aicher A, Mohaupt M, Hartung T, Dimmeler S, Kirschning CJ, Schumann RR. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:25680–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011615200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwandner R, Dziarski R, Wesche H, Rothe M, Kirschning CJ. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17406–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Travassos LH, Girardin SE, Philpott DJ, Blanot D, Nahori MA, Werts C, Boneca IG. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:1000–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nadesalingam J, Dodds AW, Reid KB, Palaniyar N. J Immunol. 2005;175:1785–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van de Wetering JK, van Eijk M, van Golde LM, Hartung T, van Strijp JA, Batenburg JJ. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:1143–51. doi: 10.1086/323746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malley R, Henneke P, Morse SC, Cieslewicz MJ, Lipsitch M, Thompson CM, Kurt-Jones E, Paton JC, Wessels MR, Golenbock DT. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100:1966–1971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0435928100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akira S, Takeda K, Kaisho T. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:675–80. doi: 10.1038/90609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macfarlane DE, Manzel L. J Immunol. 1998;160:1122–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heil F, Ahmad-Nejad P, Hemmi H, Hochrein H, Ampenberger F, Gellert T, Dietrich H, Lipford G, Takeda K, Akira S, Wagner H, Bauer S. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:2987–97. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee J, Chuang TH, Redecke V, She L, Pitha PM, Carson DA, Raz E, Cottam HB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6646–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0631696100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan AQ, Lees A, Snapper CM. J Immunol. 2004;172:532–539. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gursel I, Gursel M, Yamada H, Ishii KJ, Takeshita F, Klinman DM. J Immunol. 2003;171:1393–1400. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang LY, Ishii KJ, Akira S, Aliberti J, Golding B. J Immunol. 2005;175:3964–3970. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barrat FJ, Meeker T, Gregorio J, Chan JH, Uematsu S, Akira S, Chang B, Duramad O, Coffman RL. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1131–1139. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lenert P. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;140:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02728.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamada H, Gursel I, Takeshita F, Conover J, Ishii KJ, Gursel M, Takeshita S, Klinman DM. J Immunol. 2002;169:5590–5594. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown WJ, Constantinescu E, Farquhar MG. J Cell Biol. 1984;99:320–326. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.1.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diebold SS, Kaisho T, Hemmi H, Akira S, Reis e Sousa C. Science. 2004;303:1529–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1093616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heil F, Hemmi H, Hochrein H, Ampenberger F, Kirschning C, Akira S, Lipford G, Wagner H, Bauer S. Science. 2004;303:1526–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1093620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khan AQ, Shen Y, Wu ZQ, Wynn TA, Snapper CM. Infect Immun. 2002;70:749–61. doi: 10.1128/iai.70.2.749-761.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luther SA, Cyster JG. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:102–7. doi: 10.1038/84205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murphy KM, Reiner SL. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:933–44. doi: 10.1038/nri954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khan AQ, Chen Q, Wu ZQ, Paton JC, Snapper CM. Infect Immun. 2005;73:298–307. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.298-307.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Malley R, Henneke P, Morse SC, Cieslewicz MJ, Lipsitch M, Thompson CM, Kurt-Jones E, Paton JC, Wessels MR, Golenbock DT. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1966–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0435928100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dalpke A, Frank J, Peter M, Heeg K. Infect Immun. 2006;74:940–6. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.2.940-946.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown WJ, Constantinescu E, Farquhar MG. J Cell Biol. 1984;99:320–6. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.1.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hacker H, Mischak H, Miethke T, Liptay S, Schmid R, Sparwasser T, Heeg K, Lipford GB, Wagner H. Embo J. 1998;17:6230–40. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang LY, Ishii KJ, Akira S, Aliberti J, Golding B. J Immunol. 2005;175:3964–70. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bafica A, Scanga CA, Feng CG, Leifer C, Cheever A, Sher A. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1715–24. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kalis C, Gumenscheimer M, Freudenberg N, Tchaptchet S, Fejer G, Heit A, Akira S, Galanos C, Freudenberg MA. J Immunol. 2005;174:4295–300. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Neujahr DC, Reich CF, Pisetsky DS. Immunobiology. 1999;200:106–19. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(99)80036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nonnenmacher C, Dalpke A, Zimmermann S, Flores-De-Jacoby L, Mutters R, Heeg K. Infect Immun. 2003;71:850–6. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.2.850-856.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sparwasser T, Miethke T, Lipford G, Erdmann A, Hacker H, Heeg K, Wagner H. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1671–9. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Rossum AM, Lysenko ES, Weiser JN. Infect Immun. 2005;73:7718–26. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7718-7726.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Letiembre M, Echchannaoui H, Bachmann P, Ferracin F, Nieto C, Espinosa M, Landmann R. Infect Immun. 2005;73:8397–401. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8397-8401.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu MY, Van Huffel C, Du X, Birdwell D, Alejos E, Silva M, Galanos C, Freudenberg M, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Layton B, Beutler B. Science. 1998;282:2085–8. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paton JC. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:103–6. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(96)81526-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Houldsworth S, Andrew PW, Mitchell TJ. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1501–3. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.4.1501-1503.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hirschfeld M, Weis JJ, Toshchakov V, Salkowski CA, Cody MJ, Ward DC, Qureshi N, Michalek SM, Vogel SN. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1477–82. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1477-1482.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jones BW, Heldwein KA, Means TK, Saukkonen JJ, Fenton MJ. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60 3:iii6–12. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.90003.iii6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jones BW, Means TK, Heldwein KA, Keen MA, Hill PJ, Belisle JT, Fenton MJ. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69:1036–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carl VS, Brown-Steinke K, Nicklin MJ, Smith MF., Jr J Biol Chem. 2002;277:17448–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111847200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Re F, Strominger JL. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37692–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105927200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gao J, Zuvanich E, Xue Q, Horn D, Silverstein R, Morrison D. J Immunol. 1999;163:4095–4099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sato S, Nomura F, Kawai T, Takeuchi O, Muhlradt PF, Takeda K, Akira S. J Immunol. 2000;165:7096–101. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yi AK, Yoon JG, Hong SC, Redford TW, Krieg AM. Int Immunol. 2001;13:1391–404. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.11.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Napolitani G, Rinaldi A, Bertoni F, Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:769–76. doi: 10.1038/ni1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gautier G, Humbert M, Deauvieau F, Scuiller M, Hiscott J, Bates EE, Trinchieri G, Caux C, Garrone P. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1435–46. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lembo A, Kalis C, Kirschning CJ, Mitolo V, Jirillo E, Wagner H, Galanos C, Freudenberg MA. Infect Immun. 2003;71:6058–62. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.6058-6062.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weiss DS, Raupach B, Takeda K, Akira S, Zychlinsky A. J Immunol. 2004;172:4463–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Takeuchi O, Hoshino K, Akira S. J Immunol. 2000;165:5392–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tsuji S, Matsumoto M, Takeuchi O, Akira S, Azuma I, Hayashi A, Toyoshima K, Seya T. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6883–90. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.12.6883-6890.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Uehori J, Matsumoto M, Tsuji S, Akazawa T, Takeuchi O, Akira S, Kawata T, Azuma I, Toyoshima K, Seya T. Infect Immun. 2003;71:4238–49. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.8.4238-4249.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]