Abstract

Determining how personality disorder traits and panic disorder and/or agoraphobia relate longitudinally is an important step in developing a comprehensive understanding of the etiology of panic/agoraphobia. In 1981, a probabilistic sample of adult (≥ 18 years old) residents of east Baltimore were assessed for Axis I symptoms and disorders using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS); psychiatrists re-evaluated a sub-sample of these participants and made Axis I diagnoses, as well as ratings of individual DSM-III personality disorder traits. Of the participants psychiatrists examined in 1981, 432 were assessed again in 1993–1996 using the DIS. Excluding participants who had baseline panic attacks or panic-like spells from the risk groups, baseline timidity (avoidant, dependent, and related traits) predicted first-onset DIS panic disorder or agoraphobia over the follow-up period. These results suggest that avoidant and dependent personality traits are predisposing factors, or at least markers of risk, for panic disorder and agoraphobia - not simply epiphenomena.

Introduction

Determining how personality disorder traits and panic disorder and/or agoraphobia relate longitudinally is an important step in developing a comprehensive understanding of the etiology of panic/agoraphobia. Cluster C (anxious cluster) personality traits, especially avoidant and dependent traits, are strongly related to anxiety disorders, including panic disorder and agoraphobia, cross-sectionally [1–3].

Some have argued that avoidant and dependent traits are predisposing factors for (or prodromal factors in) panic/agoraphobia, based on retrospective reports of anxious patients’ premorbid personalities [4]. However, relying on retrospective reports introduces potential recall bias; i.e., patients with current panic/agoraphobia may have biased memories of their premorbid personality traits.

Others have argued that early panic symptoms probably shape personality, e.g., enhancing avoidant and dependent tendencies [5, 6]. Indeed, personality abnormalities can be diminished somewhat by effective treatment of panic disorder and agoraphobia [7, 8], and this may indicate some degree of state-trait confounding in the context of acute psychopathology [9]. Of course, a state-trait confounding explanation presumes that treatment of panic/agoraphobia has no influence on personality traits themselves; this may not be correct [10, 11].

The most informative method for determining whether or not personality disorder traits are risk factors for panic/agoraphobia is to longitudinally relate the former to later first onset of the latter; we know of only one prior study that used this method [12]. [Note that we are using the term “risk factor” in a broad sense here – i.e., a risk factor is an attribute or exposure that is associated with an increased probability of a specified outcome [13], not necessarily a causal factor.] The current study uses general population cohort data to determine whether baseline personality disorder characteristics predict subsequent first onset of panic disorder or agoraphobia over a 13-year period, excluding participants with baseline spontaneous panic attacks or subthreshold panic-like spells from the risk groups. If personality abnormalities are merely epiphenomena of panic/agoraphobia, baseline personality disorder traits should be unrelated to subsequent onset. Since avoidant and dependent traits are strongly related to panic and agoraphobia cross-sectionally, these were the strongest a priori candidates as personality disorder trait risk factors.

Methods

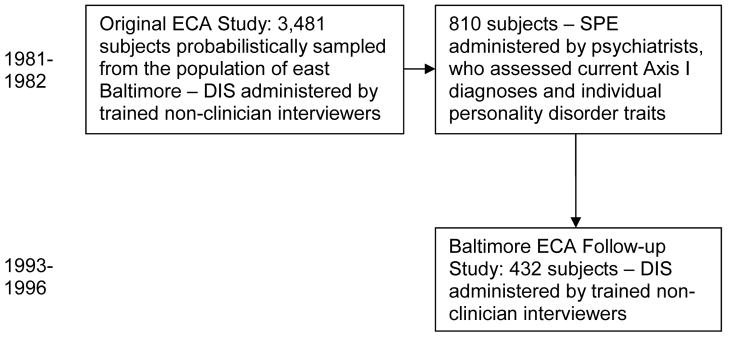

The current study, which was approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board, involves the longitudinally-assessed Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) cohort. In 1981, trained non-clinician interviewers administered a DSM-III version of the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS-III) [14] to a probabilistic sample of the adult population of eastern Baltimore (n=3,481). Psychiatrists interviewed 810 of these participants using the Standardized Psychiatric Examination, which assessed current DSM-III Axis I disorders and each of the DSM-III personality disorder criteria [15, 16]. In the assessment of personality disorder traits, the examining psychiatrist rated enduring characteristics based on the participant’s personal history, psychiatric history, mental state, and answers to specific personality-related questions [16].

Between 1993 and 1996, in the Baltimore ECA Follow-up study, 88% of the original Baltimore cohort was traced, and 73% of those known to be alive provided informed, written, voluntary consent and were re-interviewed using a DSM-III-R version of the DIS (n=1920; 432 of these participants were examined by psychiatrists in 1981) [17]. Mortality in the intervening thirteen years was substantial as a result of the high proportion of elderly respondents originally sampled [18]. No baseline personality disorder factors were associated with participation in the Follow-up study. The overall design is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Design of the current study. DIS = Diagnostic Interview Schedule; ECA = Epidemiologic Catchment Area; SPE = Standardized Psychiatric Examination.

For the current study, participants were considered at risk for first-onset DIS-III-R panic disorder or agoraphobia over the follow-up period if 1) they did not have a lifetime history of the DIS-III syndrome in 1981, 2) they did not have the DSM-III syndrome currently at the time of the 1981 psychiatric interview, and 3) they did not have a lifetime history of spontaneous panic attacks or panic-like spells in 1981 (assessed using the DIS-III). Participants at risk for the disorder were considered first-onset cases if they met lifetime DIS-III-R criteria at follow-up (1993–1996). This method is similar to that used in prior work on the incidence of these conditions [19, 20], with 2 important distinctions: 1) in prior work, we did not incorporate the 1981 psychiatrist interview data, as it was only present for a subset of the entire sample (unlike the present study, which only includes subjects who had a baseline psychiatric interview); and 2) in this study, we excluded participants with a lifetime history of spontaneous panic attacks or panic-like spells from the risk groups, because these symptoms have been hypothesized to shape personality in persons who later develop panic disorder and/or agoraphobia [6].

Statistical Analysis

In this general population sample, using the above methods, there were too few cases of baseline personality disorder for meaningful longitudinal analyses; e.g., there were no participants who met full criteria for avoidant personality disorder [16]. Thus, we chose to create dimensional scales for analyses. We note that this dimensional approach is consistent with the direction many in the field have been taking with regard to defining personality pathology [21–23]. Particularly in DSM-III, there was substantial overlap across personality disorders in criterion content [24]. In addition, personality disorders and their constituent traits frequently co-occur [22, 25]. Our group previously used dichotomous factor analysis to explore the structure of the 1981 psychiatrist-assessed DSM-III personality disorder items. A five-factor model appeared the most apt, based on the scree plot and examination of 7 possible factor solutions (from 2-factor to 8-factor models) [26]. For the current study, we created unit-weighted scales to represent the five empirically derived, relatively orthogonal factors: unscrupulousness, timidity, animation, distrust, and coldness (we have modified the factor names slightly from the previous publication to reflect the meaning of a high scale score). In creating these scales, we selected items with factor loadings 0.60 and no double-loadings (only 1 item loaded on more than 1 factor; “indifference to praise” had a loading of 0.67 on both timidity and coldness). The items defining each factor are listed in Table 1. Notably, the timidity factor includes all of the DSM-III avoidant items, 2 of 3 dependent items, 3 of 8 schizotypal items, 1 schizoid item, and 1 borderline item; the particular schizotypal and schizoid items relate meaningfully to the others in the factor in that they index self-consciousness, sensitivity to criticism, and social isolation. The unscrupulousness factor includes most of the antisocial items; the animation factor is made up of histrionic and a few other Cluster B items; the distrust factor is mainly made up of paranoid items; and the coldness factor includes a mixture of remaining Cluster A and other items.

Table 1.

Items defining personality disorder factors in this study

| unscrupulousness (21 items) | ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

| timidity (12 items) | ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

| animation (10 items) | ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

| distrust (12 items) | ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

| coldness (9 items) | ||

|

|

|

pr=paranoid, sz=schizoid, st=schizotypal, an=antisocial, b=borderline, h=histrionic, n=narcissistic, av=avoidant, d=dependent, ps=passive-aggressive

We used Stata (v. 8.0) to conduct all analyses. To compare the demographic profiles of participants at risk who did and did not develop first-onset panic disorder or agoraphobia over the follow-up period, we used Fisher’s Exact tests. We used the 5 factor scales as predictors of subsequent development of first-onset DIS-III-R panic disorder or agoraphobia in univariable and multivariable logistic regression models. Note that the outcomes of the primary analyses were first-onset panic disorder or first-onset agoraphobia. Though panic and agoraphobia are strongly related, either can develop in the absence of the other [19, 20, 27].

Results

Baseline (1981) demographic characteristics of the 432 participants were as follows: 36% were 18–29 years old, 30% were 30–44, 22% were 45–64, and 12% were 65 or older; 32% were male, and 68% were female; 58% were white, 38% were African-American, and 4% were of another race; 15% had less than or equal to 8 years of education, 29% had 9–11 years, 29% had 12 years, and 27% had more than 12 years; 38% were married, 12% were widowed, 11% were separated, 12% were divorced, and 27% had never married.

Of the 432 participants, 373 were at risk for first-onset panic disorder, and 11 developed the condition during the follow-up period. The demographic characteristics of these participants with first-onset panic disorder were similar to those of the larger group of first-onset cases in the Follow-up study [19]; though, with this smaller sample size, none of the previously identified demographic factors (younger age, female sex, and white race) were statistically significant predictors of onset (Fisher’s Exact p > 0.05). Of these 11 participants, 5 were 18–29 years old in 1981, 6 were 30–44, and none were older; 10 were female, and one was male; 9 were white, 2 were African-American, and none were of another race. For first-onset agoraphobia, 323 were at risk, and 8 developed the condition during the follow-up period. [Note that the 1981 DIS-III diagnosis of agoraphobia was very common, and many of the participants with DIS-III agoraphobia probably would have been diagnosed with simple phobias if assessed by clinicians [28]; nevertheless, we excluded participants with 1981 DIS-III agoraphobia from the agoraphobia risk group. Therefore, if one used these numbers to estimate the incidence of first-onset DIS-III-R agoraphobia, the estimate would be conservative [20].] The demographic characteristics of these participants with first-onset agoraphobia were similar to those of the larger group of first-onset agoraphobia cases in the Follow-up study [20]; again, with this smaller sample size, neither of the previously identified demographic factors (younger age and female sex) were statistically significant predictors of onset (Fisher’s Exact p > 0.05). Of these 8 participants, 4 were 18–29 years old in 1981, 3 were 30–44, 1 was 45–64, and none were older; 6 were female, and 2 were male.

Of the 5 personality disorder factors, only timidity predicted first onset of panic disorder or agoraphobia over the follow-up period (Table 2). Participants with higher timidity scores had a substantially increased risk of first-onset panic disorder or agoraphobia over the follow-up period (odds ratio [OR] = 1.4 to 1.5 for a point higher timidity score; p < 0.005). Results were very similar when the demographic factors age, sex, and race were added as covariates in multivariable models.

Table 2.

Baseline personality disorder (PD) factor scores as predictors of subsequent first-onset panic disorder or agoraphobia over a 13-year period (participants with baseline panic attacks or panic-like spells were excluded from the risk groups)

| panic disorder | agoraphobia | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unadjusted | adjusted 1 | unadjusted | adjusted 2 | ||||||||

| PD factor scales | mean | sd | range 3 | OR 4 | 95% CI 5 | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| unscrupulousness | 1.1 | 2.5 | (0–19) | 1.0 | (0.8–1.3) | 1.1 | (0.8–1.5) | 1.0 | (0.7–1.4) | 1.0 | (0.7–1.4) |

| timidity | 0.6 | 1.5 | (0–11) | 1.4 | (1.2–1.8) | 1.4 | (1.1–1.8) | 1.5 | (1.2–1.9) | 1.5 | (1.1–1.9) |

| animation | 1.2 | 1.8 | (0–8) | 1.0 | (0.8–1.4) | 1.0 | (0.7–1.4) | 0.7 | (0.4–1.4) | 0.7 | (0.3–1.3) |

| distrust | 0.2 | 0.8 | (0–8) | 1.1 | (0.6–2.0) | 1.3 | (0.7–2.4) | 0.8 | (0.2–3.2) | 0.9 | (0.2–3.3) |

| coldness | 0.1 | 0.4 | (0–4) | - 6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

adjusted for age group, sex, and race

adjusted for age group and sex

mean, standard deviation, and range of number of personality disorder factor items in participants at risk (all factor scores were highly skewed)

odds ratio for later first-onset disorder given a single point higher baseline personality disorder factor score

confidence interval

No participants with any coldness traits developed panic disorder or agoraphobia.

Bold indicates odds ratios significantly greater than 1.0 (p < 0.005).

Notably, 3 participants had first-onset panic disorder and agoraphobia over the follow-up period, 8 had first-onset panic disorder without agoraphobia, and 5 had first-onset agoraphobia without panic disorder. In secondary analyses, we examined timidity as a predictor of these mutually exclusive outcomes. Participants with higher timidity scores had substantially increased risk of each of these outcomes (for panic disorder with agoraphobia, OR = 1.6, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.2 to 2.1, for a point higher timidity score; for panic disorder without agoraphobia, OR = 1.4, 95% CI = 1.1 to 1.9, for a point higher timidity score; and for agoraphobia without panic disorder, OR = 1.4, 95% CI = 1.0 to 2.0, for a point higher timidity score).

Discussion

We found that avoidant, dependent, and related traits (timidity) predicted onset of panic disorder, agoraphobia, or both conditions over the follow-up period. These findings fit conceptions of avoidant and dependent traits as risk factors, as opposed to consequences of panic attacks or panic-like spells (recall that we excluded participants with baseline panic attacks or panic-like spells from the risk groups).

These findings support the contention of Sir Martin Roth that panic and agoraphobia do not always emerge ‘out of an entirely clear sky’ and that ‘the complex repertoire of avoidance behaviors and helpless dependence on others’ are ‘not entirely without premorbid antecedents’ [29] (page 36). Roth urged practitioners to ‘consider the stressful life circumstances that have surrounded the onset of illness’ and a patient’s ‘premorbid personality and its Achilles heels’ [30] (page 154). These sentiments have long been echoed by Fava et al., who have recently reviewed the rich phenomena experienced by these patients in the course of their illnesses [31]. Such information is indispensible to clinicians and researchers who wish to understand panic disorder and agoraphobia in all their complexity. Until recently, this longitudinal data was only available through retrospective investigations.

The one similar previous study was the Children in the Community Study [12]. That project involved different methods than the current study, including: 1) personality disorder traits were assessed by non-clinicians using a fully structured interview (these were assessed by psychiatrists using a semi-structured interview in the current study), and 2) the personality disorder scales were sums of individual personality disorder criteria (vs. empirically derived factors in the current study). Nevertheless, it is interesting to note areas of overlap and difference across studies. Consistent with the current study, Johnson et al. found that schizotypal and dependent personality traits evident by mean age 22 years were associated with significantly increased risk for panic disorder or agoraphobia at mean age 33 years. In contrast to the current study (which found no relationship between baseline unscrupulousness and later first-onset agoraphobia), Johnson et al. found that antisocial personality traits at mean age 22 were associated with significantly increased risk of agoraphobia at mean age 33 years. Differences in results across studies may relate, at least in part, to methodological differences.

Though we can say, with some confidence, that avoidant and dependent traits predated the onset of panic disorder or agoraphobia in this study, it is important to note that it remains unclear whether the former were truly predisposing factors for the latter (as in a diathesis-stress model). Avoidant and dependent traits may be part of an inherited spectrum, as suggested by a family study in which relatives of patients with panic disorder had more avoidant and dependent traits than relatives of controls [32]. Nevertheless, what we can say is that these traits in adults are at least markers of risk for panic disorder and/or agoraphobia; such information may be useful in prevention efforts [33].

The limitations of this study deserve mention. First, attrition was substantial. This was largely due to oversampling of the elderly at baseline; many participants died during the follow-up period [18]. Nevertheless, the participants who developed agoraphobia or panic disorder during the follow-up period were younger participants [19, 20], and there was adequate representation of the elderly in the Follow-up study. In addition, personality factors were unrelated to whether or not participants were interviewed at follow-up.

Second, at follow-up, we relied exclusively on DIS-III-R diagnoses. In previous work, we have shown that the DIS-III-R diagnoses of panic disorder and agoraphobia have good clinical validity; however, the DIS-III-R is a less sensitive diagnostic instrument than a psychiatrist evaluation [19, 20]. This lack of sensitivity should, if anything, bias toward the null hypothesis of no association.

Third, though we excluded participants with baseline lifetime panic attacks or panic-like spells from the risk groups, we did not exclude participants with a history of any anxiety symptoms whatsoever (e.g., social anxiety). In our opinion, such an exclusion would not be desirable. Avoidant or dependent traits should be associated with some anxiety symptoms in certain contexts; the crucial issue, addressed in this report, is that these traits do not appear to be due to panic symptoms themselves.

Fourth, it is likely that personality disorder traits and Axis I conditions relate in many ways [1, 3]. Here, we have addressed personality disorder traits as risk factors, but we have not addressed possible state-trait confounding or “scar” effects of panic/agoraphobia on personality disorder traits in adulthood. Panicky spells in adolescence do appear to predict onset of personality disorders, including Cluster C personality disorders, by young adulthood [34].

Fifth, we did not assess “normal” or “general” personality traits at baseline in this study. We would expect that our timidity factor would relate positively to neuroticism and negatively to extraversion, based on normal personality/personality disorder relations in other studies [35] and examination of the items in the timidity factor. Persons with panic disorder tend to be high in neuroticism, while those with agoraphobia tend to be high in neuroticism, low in extraversion, or both [1, 36, 37]. Neuroticism (negative affectivity) appears to prospectively predict panic attacks in adolescents [38] and panic disorder in adults [39]. We know of no similar longitudinal studies of agoraphobia at present.

Sixth, unlike the Children in the Community Study [12], we focused on only two anxiety disorders in the current study. We chose to examine personality disorder traits as risk factors for panic disorder and/or agoraphobia for both substantive and methodologic reasons. Unlike the Children in the Community Study, which involved baseline personality disorder trait assessments between mean ages 14 and 22 years, our study involved personality disorder trait assessments when subjects were 18 years old or older. Though we had longitudinal data on social phobia, this condition typically has onset in early adolescence (prior to when we assessed personality disorder traits). In contrast, panic disorder and agoraphobia typically have onsets in adulthood [40]. Though generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) can also have onsets in adulthood, we did not assess GAD in 1981, and there were too few cases of first-onset OCD in the current sample for meaningful longitudinal analyses.

Acknowledgments

National Institute of Mental Health grants R01-MH47447, R01-MH50616, and K23-MH64543 supported this study. The authors report no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bienvenu OJ, Stein MB. Personality and anxiety disorders: a review. J Personal Disord. 2003;17:139–151. doi: 10.1521/pedi.17.2.139.23991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou PS, Ruan JW, et al. Co-occurrence of 12-month mood and anxiety disorders and personality disorders in the US: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Psychiatr Res. 2005;39:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tyrer P, Gunderson J, Lyons M, Tohen M. Extent of comorbidity between mental state and personality disorders. J Personal Disord. 1997;11:242–259. doi: 10.1521/pedi.1997.11.3.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Argyle N, Roth M. The phenomenological study of 90 patients with panic disorder, part II. Psychiatr Dev. 1989;3:187–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein DF. Anxiety reconceptualized. Compr Psychiatry. 1980;21:411–427. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(80)90043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cassano GB, Michelini S, Shear MK, Coli E, Maser JD, Frank E. The panic-agoraphobic spectrum: a descriptive approach to the assessment and treatment of subtle symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(6 suppl):27–38. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.6.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marchesi C, Cantoni A, Fonto S, Giannelli MR, Maggini C. The effect of pharmacotherapy on personality disorders in panic disorder: a one year naturalistic study. J Affect Disord. 2005;89:189–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mavissakalian M, Hamann MS. DSM-III personality disorder in agoraphobia. II. Changes with treatment. Compr Psychiatry. 1987;28:356–361. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(87)90072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reich J, Noyes RJ, Coryell W, O’Gorman TW. The effect of state anxiety on personality measurement. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:760–763. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.6.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jorm AF. Modifiability of trait anxiety and neuroticism: a meta-analysis of the literature. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1989;23:21–29. doi: 10.3109/00048678909062588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knutson B, Wolkowitz OM, Cole SW, Chan T, Moore EA, Johnson RC, et al. Selective alteration of personality and social behavior by serotonergic intervention. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:373–379. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S, Brook JS. Personality disorders evident by early adulthood and risk for anxiety disorders during middle adulthood. J Anxiety Disord. 2006;20:408–426. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Last JM. A Dictionary of Epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. p. 148. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS. National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: its history, characteristics and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:381–389. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romanoski AJ, Nestadt G, Chahal R, Merchant A, Folstein MF, Gruenberg EM, et al. Inter-observer reliability of a ‘Standardized Psychiatric Examination (SPE)’ for case ascertainment (DSM-III) J Nerv Ment Dis. 1988;176:63–71. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198802000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samuels JF, Nestadt G, Romanoski AJ, Folstein MF, McHugh PR. DSM-III personality disorders in the community. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1055–1062. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eaton WW, Anthony JC, Gallo J, Cai G, Tien A, Romanoski A, et al. Natural history of Diagnostic Interview Schedule/DSM-IV major depression: the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area Follow-up. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:993–999. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230023003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Badawi MA, Eaton WW, Myllyluoma J, Weimer LG, Gallo J. Psychopathology and attrition in the Baltimore ECA 15-year follow-up 1981–1996. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34:91–98. doi: 10.1007/s001270050117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eaton WW, Anthony JC, Romanoski A, Tien A, Gallo J, Cai G, et al. Onset and recovery from panic disorder in the Baltimore ECA Follow-up. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:501–507. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.6.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bienvenu OJ, Onyike CU, Stein MB, Chen LS, Samuels J, Nestadt G, et al. Agoraphobia in general population adults: incidence and longitudinal relationships with panic. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:432–438. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.010827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Widiger TA, Simonsen E, Krueger R, Livesley WJ, Verheul R. Personality disorder research agenda for the DSM-V. J Personal Disord. 2005;19:315–338. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.3.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Vernon PA. Phenotypic and genetic structure of traits delineating personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:941–948. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.10.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nestadt G, Romanoski AJ, Brown CH, Chahal R, Merchant A, Folstein MF, et al. DSM-III compulsive personality disorder: an epidemiological survey. Psychol Med. 1991;21:461–471. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700020572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Livesley WJ. A systematic approach to the delineation of personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:772–777. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.6.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Connor BP. A search for consensus on the dimensional structure of personality disorders. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61:323–345. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nestadt G, Eaton WW, Romanoski AJ, Garrison R, Folstein MF, McHugh PR. Assessment of DSM-III personality structure in a general-population survey. Compr Psychiatry. 1994;35:54–63. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(94)90170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wittchen HU, Nocon A, Beesdo K, Pine DS, Hofler M, Lieb R, et al. Agoraphobia and panic. Prospective-longitudinal relations suggest a rethinking of diagnostic concepts. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77:147–157. doi: 10.1159/000116608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horwath E, Lish JD, Johnson J, Hornig CD, Weissman MM. Agoraphobia without panic: clinical reappraisal of an epidemiologic finding. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1496–1501. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.10.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roth M. Agoraphobia, panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. Psychiatr Dev. 1984;2:31–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roth M. Some recent developments in relation to agoraphobia and related disorders and their bearing upon theories of their causation. Psychiatr J Univ Ottawa. 1987;12:150–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fava GA, Rafanelli C, Tossani E, Grandi S. Agoraphobia is a disease: a tribute to Sir Martin Roth. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77:133–138. doi: 10.1159/000116606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reich J. Avoidant and dependent personality traits in relatives of patients with panic disorder, patients with dependent personality disorder, and normal controls. Psychiatry Res. 1991;39:89–98. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(91)90011-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bienvenu OJ, Ginsburg GS. Prevention of anxiety disorders. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19:647–654. doi: 10.1080/09540260701797837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goodwin RD, Brook JS, Cohen P. Panic attacks and the risk of personality disorder. Psychol Med. 2005;35:227–235. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saulsman LM, Page AC. The five-factor model and personality disorder empirical literature: A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;23:1055–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2002.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bienvenu OJ, Samuels JF, Costa PT, Reti IM, Eaton WW, Nestadt G. Anxiety and depressive disorders and the five-factor model of personality: a higher- and lower-order personality trait investigation in a community sample. Depress Anxiety. 2004;20:92–97. doi: 10.1002/da.20026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bienvenu OJ, Hettema JM, Neale MC, Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Low extraversion and high neuroticism as indices of genetic and environmental risk for social phobia, agoraphobia, and animal phobia. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1714–1721. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06101667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hayward C, Killen JD, Kraemer HC, Taylor CB. Predictors of panic attacks in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:207–214. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200002000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Angst J, Vollrath M. The natural history of anxiety disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1991;84:446–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1991.tb03176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]