Abstract

Spontaneous intrusive recollections (SIRs) follow traumatic events in clinical and non-clinical populations. To determine whether any relationship exists between SIRs and enhanced memory for emotional events, participants viewed emotional or neutral films, had their memory for the films tested two days later, and estimated the number of SIRs they experienced for each film. SIR frequency related positively to memory strength, an effect more pronounced in the emotional condition. These findings represent the first demonstration of a relationship between SIRs occurring after an emotional experience and subsequent memory strength for that experience. The results are consistent with the possibility that emotional arousal leads both to elevated SIR frequency and better memory, and that the covert rehearsal associated with SIRs enhances memory for emotional relative to neutral stimuli. Additional evidence of menstrual cycle influences on SIR incidence in female participants appears to merit consideration in future work.

Keywords: memory, emotion, intrusions, sex differences, menstrual cycle

INTRODUCTION

Emotional events are often remembered in a particularly strong and lasting manner relative to neutral events. Emotional stimuli are typically associated with a substantial long-term memory enhancement relative to neutral stimuli, whether the stimuli are words (Rubin & Friendly, 1986; Kensinger & Corkin, 2004), pictures (Bradley, Greenwald, Petry, & Lang, 1992), films (Cahill et al, 1996), or slide shows accompanied by a narrative (Heuer & Reisberg, 1990; Cahill & McGaugh, 1995). Although some conflicting studies suggest that emotional arousal may be associated with impaired memory in some instances, the overwhelming majority of evidence collected from clinical and laboratory studies suggests an enhancement of memory for emotional events and stimuli, especially for those elements defined as central as opposed to peripheral details (see Christianson, 1992, for a review). One hypothesis to account for this observed enhancement of memory under emotional conditions concerns the role of rehearsal. By this view, emotional events are better remembered in part because they are talked about (overt rehearsal) and thought about (covert rehearsal) much more frequently than are relatively neutral events (Bohannon, 1988). Although evidence indicates that overt rehearsal is insufficient to explain enhanced long-term memory for emotional materials (Guy & Cahill, 1999), the potential contribution of covert rehearsal to memory strength has not been ruled out.

Post-event experience of spontaneous intrusive recollections (SIRs), particularly after traumatic events, is a widely known phenomenon. Many studies document SIRs occurring after emotional events including natural disasters (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991), the collapse of man-made structures (Wilkinson, 1983), and the assassination of presidents (Brown & Kulik, 1977). Additionally, SIRs are known to occur following traumatic events in both clinical (Reynolds & Brewin, 1998; Reynolds & Brewin, 1999) and nonclinical (Brewin, Christodoulides, & Hutchinson, 1996; Reynolds & Brewin, 1998) populations. Insofar as they constitute additional rehearsal opportunities, SIRs following traumatic events would likely contribute to the enhanced memory for these events. To the extent that SIRs occur after neutral events, they can potentially contribute to memory strength in those circumstances as well.

As plausible as it may sound, it has never been formally demonstrated that emotional stimuli are associated with more SIRs than are neutral stimuli, or that any relationship exists between SIRs and later memory strength. In order to make a case that increased SIR frequency under emotionally arousing conditions contributes to enhanced memory for emotional relative to neutral stimuli, several results should be obtained. First, one’s experimental conditions should demonstrate enhanced memory for emotional versus neutral stimuli. Second, it should be established that more SIRs are reported in the emotional condition than the neutral condition. Lastly, if post-event SIRs contribute to memory enhancement, it should be possible to establish a quantitative relationship between the frequency of SIRs occurring after exposure to stimuli and strength of subsequent memory for those stimuli. Here we provide the first experimental evidence that emotional stimuli are associated with more SIRs than neutral stimuli, that a relationship exists between SIRs and memory, and furthermore that this relationship is more pronounced in emotional than neutral conditions.

Recent work strongly indicates that potential influences of subject sex must be taken into account in studies of emotionally influenced memory (Cahill et al, 2001; Canli, Desmond, Zhao, & Gabrieli, 2002; Cahill, 2003; Cahill, 2006). This may be especially true in the case of SIRs. Women are nearly twice as likely to suffer from depression and posttraumatic stress disorder as men (Kendler, Thornton, & Prescott, 2001; Breslau, Davis, Andreski, Peterson, & Schultz, 1997), conditions both characterized by an increased tendency toward intrusive thoughts and memories (Reynolds & Brewin, 1999). Insofar as SIRs observed in laboratory settings are similar to intrusive memories experienced in naturalistic settings after trauma exposure, potential sex differences in SIR frequency may underlie or reflect, at least in part, differential susceptibility to developing these disorders. For these reasons potential influences of sex were investigated in this study. In addition to the possibility of sex differences, recent evidence suggests that the position of female subjects within the menstrual cycle may influence various aspects of cognition (Halpern & Tan, 2001; Rosenberg & Park, 2002) as well as patterns of brain activity during cognitive task performance (Maki & Resnick, 2001). Furthermore, evidence also indicates that menstrual cycle position may affect responses to stressors as well as learning and memory under stressful conditions (Kirschbaum, Kudielka, Gaab, Schommer & Hellhammer, 1999; Andreano, Arjomandi & Cahill, 2008); hence the potential influences of menstrual phase were also examined in the current study.

METHODS

Participants

18 male and 40 naturally cycling female undergraduates at the University of California, Irvine between the ages of 18 and 28 (mean age = 20.58 ± 2.28) participated in this study, which was approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board. 1 man and 5 women were excluded due to emotionality, memory, or SIR measures more than 2 standard deviations from the mean. Additionally, 1 man and 3 women chose to withdraw from the experiment before its completion. The final analyses involved data from 32 women and 16 men, with equal numbers of each in the emotional and neutral conditions. Female participants were asked to report the date of onset of their most recent menstruation, and equal numbers (16 per phase) of women in the follicular and luteal phases of the menstrual cycle were studied.

Experimental Procedure

Each participant was shown a series of either six brief emotional or neutral film clips (described below). After each film clip the subject was asked to subjectively rate the emotionality of the film on a 10 point Likert scale, with 1 representing ‘completely unemotional’ and 10 representing ‘extremely emotional.’ Participants were advised that they could stop the study at any time with no penalty if they became uncomfortable while watching the films. Saliva samples were collected before viewing the films, as well as immediately and twenty minutes after film completion to enable the potential analysis of stress hormone response to the films (data not reported here). Participants were also connected to galvanic skin response electrodes and a heart rate monitor, and told that physiological measurements would be taken throughout the experiment. The participants were told that the experiment concerned physiological responses to the films, a ruse commonly used in our laboratory which is designed to keep subjects unaware of the subsequent memory test (Cahill & McGaugh, 1995; Cahill, Gorski & Le, 2003; Cahill, Gorski, Belcher & Huynh, 2004).

48 hours later, participants returned, having been told that they would watch a different set of film clips, but instead received a surprise free recall memory test for the films they had previously watched. First subjects were instructed to write down as many films as they could remember, not providing any specific details but rather to simply write one or two words to describe each film. These self-generated lists of recalled films were used for the subsequent tasks in order to avoid contamination of other free recall measures. Next they were asked to order the films according to their subjective assessment as to which film they remembered best, second best, and so on for all films they recalled. Finally they were asked to indicate in which order the recalled films were shown. Next, subjects were asked how many times each of the recalled films or scenes from those films had “spontaneously popped into their minds” since viewing them. Our definition of SIRs is very similar to that used in the intrusive memory literature, which describes intrusions as non-deliberate or involuntary spontaneously occurring recollections of events or stimuli (Holmes, Brewin & Hennessy, 2004; Holmes & Bourne, 2008). To reduce the likelihood that subjects would use their subjective rankings of memory strength when estimating SIR frequencies, subjects were asked to estimate SIR frequency for the films in a pseudorandom order. For example, subjects were asked to first estimate SIR frequency for the third best remembered film, followed by the fifth best remembered film, the second best remembered film, the fourth best remembered film, the best remembered film, and then the sixth best remembered film. After having done this, subjects were given sheets of blank lined paper and were instructed to write as many details as they could recall about each of the films they remembered, writing one detail per line with no time limit. After the experimental procedures were completed, subjects were debriefed and compensated for their time with course credit.

Films

Six emotional and six neutral film clips were taken from commercially available films and rated by a set of 13 independent judges. The neutral and emotional films were matched in length, content (half of the films were about animals and half were about humans), and understandability, but were significantly different from each other in the emotional reaction they produced on a 1 to 10 scale (NEUTRAL, emotion mean = 2.01 ± 0.38, mean length = 110.67 ± 27.02; EMOTIONAL, emotion mean = 8.51 ± 0.41, mean length = 106.83 ± 29.56 seconds), [Rating, F(1, 10) = 808.33, p <.0001].

Statistical Analysis

Emotion ratings, free recall memory, and SIR measures were compared between men and women in emotional and neutral conditions using two-way ANOVAs using Condition as a between-subjects variable. In analyses of detail memory, only correctly recalled details were analyzed. Scoring of the freely recalled details was determined by a single judge (N.F.). In the vast majority of cases, recalled items were readily identifiable as accurately pertaining to a specific film or clearly erroneous. In the rare cases in which the accuracy of a response was questionable, a second judge unconnected to the study was consulted and a consensus between the two judges was established. The relationship between the number of reported SIRs and subjective memory strength ranking was compared between emotional and neutral conditions by a two-way ANOVA and Fisher’s PLSD post-hoc tests. In all analyses involving subjective rank, the 5-level factor Subjective Rank was used. Only the first five best remembered films were included in analyses of subjective rank because only 21% of subjects remembered all six films, and the overall rate of recall of all six films was too low to allow valid conclusions about SIR incidence to be made for this group. The analyses of subjective rank included the 31% of subjects who remembered only four films. The relationships between memory measures and SIRs were characterized using regression analysis. Correlation coefficients (R) were computed for linear regression lines, and p values for significance of fit were computed using correlation z tests.

RESULTS

Subjective arousal ratings

The mean (± SEM) rating of emotionality of the films was 7.71 ± 1.34 in the emotional condition and 2.75 ± 1.05 in the neutral condition. A 2 (Condition) × 2 (Sex) ANOVA revealed significant main effects of Condition [F(1,44) = 262.23, p <.0001], Sex [F(1,44) = 21.50 p <.0001], and a Condition × Sex interaction [F(1, 44) = 10.16, p <.01]. Men and women rated the neutral films similarly (MEN, mean = 2.47 ± 1.04; WOMEN, mean = 2.89 ± 1.06) but women rated the emotional films significantly higher than did the men (MEN, mean = 6.21 ± 0.96; WOMEN, mean = 8.46 ± 0.73).

Memory Measures

A 2 (Condition) × 2 (Sex) ANOVA of number of recalled films revealed a main effect of Condition [F(1,44) = 9.34, p <.01]. Participants in the emotional condition recalled significantly more films than did those in the neutral condition (emotional mean: 5.17 ± 0.70, neutral mean: 4.63 ± 0.65. Neither Sex effects nor Condition × Sex interactions were observed in this analysis.

A 2 (Condition) × 2 (Sex) ANOVA of the mean number of details recalled per film revealed a main effect of Condition [F(1,44) = 24.09, p <.0001], such that subjects in the emotional condition recalled nearly twice as many details as did those in the neutral condition (emotional mean: 7.12 ± 2.44, neutral mean: 3.97 ± 1.39). Neither Sex effects nor Condition × Sex interactions were observed in this analysis.

A 2 (Condition) × 2 (Sex) ANOVA of performance on the film order task revealed no main effects of Condition (emotional mean: 70.44 ± 25.94% accuracy, neutral mean: 60.61 ± 25.78% accuracy), Sex, nor a Condition × Sex interaction (all p ≥.20).

Relationship between Subjective Ranking of Memory Strength and Recall of Film Details

To provide an independent validation of the use of subjects’ subjective ranking to determine strength of film recall, we assessed the relationship between subjective rank and number of recalled details for both the emotional and neutral films. We surmised that the more strongly subjects subjectively felt they recalled a film, the greater should be the number of recalled details for that film. Indeed, this proved to be the case. A 2 (Condition) × 5 (Subjective Rank) ANOVA revealed main effects of Condition [F(1,215) = 57.31, p <.0001] and Subjective Rank [F(4,215) = 2.55, p <.05], and a trend toward a Condition × Rank Category interaction [F(4,215) = 2.25, p =.06]. Subjects recalled more details for the best remembered film than the second best remembered film, the second best remembered film was associated with more details than the third best, and so on, although this effect appeared driven by the emotional films (Mean ± SEM number of details recalled for the best recalled film: 8.17 ± 4.48 emotional, 3.92 ± 1.86 neutral; for the second best recalled film: 7.21 ± 3.34 emotional, 4.17 ± 2.24 neutral; for the third best recalled film: 7.04 ± 3.65 emotional, 3.50 ± 1.45 neutral; for the fourth best recalled film: 5.88 ± 2.40 emotional, 3.92 ± 1.77 neutral; for the fifth best recalled film: 4.80 ± 1.77 emotional, 3.77 ± 1.48 neutral). The results of this analysis therefore indicate that subjects’ subjective reports of memory strength are corroborated by the number of recalled details about each film, particularly for emotional films.

Spontaneous Intrusive Recollections

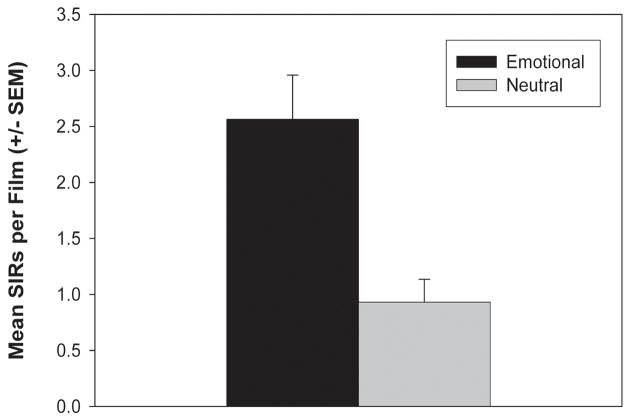

A 2 (Condition) × 2 (Sex) ANOVA of the average number of SIRs per film revealed a main effect of Condition [F(1,44) = 12.05, p =.001], such that subjects in the emotional condition reported nearly three times as many SIRs as did those in the neutral condition (see Figure 1). Neither Sex effects nor Condition × Sex interactions were observed.

Figure 1.

Mean SIRs in emotional and neutral conditions. Subjects in the emotional condition reported more intrusions than subjects in the neutral condition (p =.001).

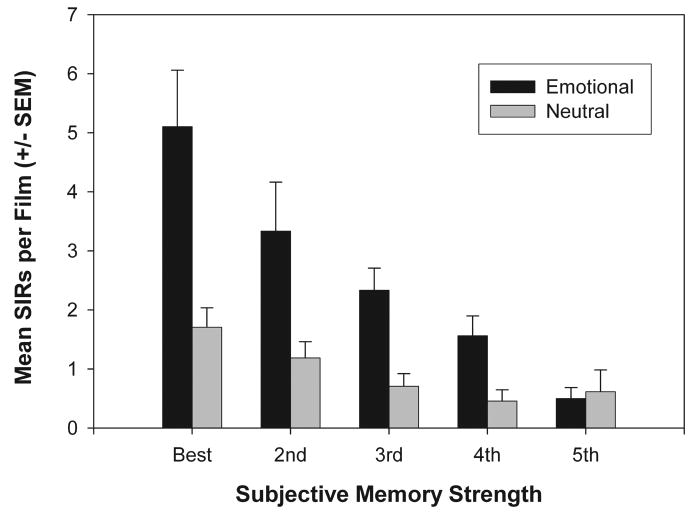

A 2 (Condition) × 5 (Subjective Rank) ANOVA of the mean number of SIRs for the first five best remembered films revealed main effects of Condition [F(1,215) = 25.81, p <.0001,], Subjective Rank [F(4,215) = 9.65, p <.0001], and a Condition × Subjective Rank interaction [F(4, 215) = 2.99, p <.05]. Participants in the emotional condition reported more SIRs than did those in the neutral condition, more SIRs were reported for the films subjectively rated as better remembered, and this effect was more pronounced in the emotional condition (see Figure 2). Fisher’s PLSD post-hoc tests revealed that the best recalled emotional film was associated with more SIRs than was the second, third, fourth, or fifth best remembered films, and that the second best remembered film was associated with more SIRs than the fourth or fifth best remembered films (all p <.01).

Figure 2.

Relationship between SIRs and subjective memory strength. More SIRs were reported by subjects in the emotional condition (p <.0001), more SIRs were associated with films subjectively rated as better remembered (p <.0001), and this relationship was more pronounced in the emotional condition (Condition × Subjective Rank interaction, p <.05).

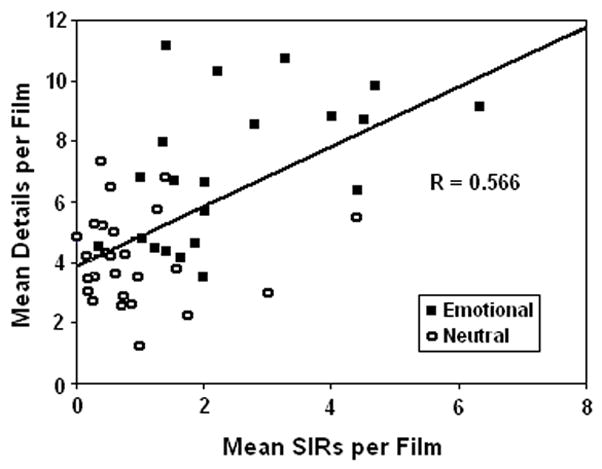

Relationship between SIR incidence and recall of details

We next determined whether a significant relationship existed between SIR frequency and detail recall of films in either the emotional or neutral conditions. To do this, we performed a regression analysis relating the mean number of SIRs reported per film to the mean number of details later recalled per film. As seen in Figure 3, an analysis combining subjects in both neutral and emotional conditions revealed a significant correlation between mean SIR frequency and the mean number of recalled details per film (R2 = 0.32, R = 0.57, p <.0001). While an analysis including only subjects who watched emotional films confirmed the existence of this relationship under emotional conditions (R2 = 0.26, R = 0.51, p =.01), an identical analysis using only subjects who watched neutral films indicated that no such correlation existed between SIR frequency and number of details under neutral conditions (R2 =.004, R = 0.07, p =.76).

Figure 3.

Correlation between SIR frequency and number of recalled details, including data from both emotional (solid squares) and neutral (open circles) conditions. A significant positive correlation was observed between the average number of reported SIRs and the average number of recalled details (R = 0.57, p <.0001).

Relationships between emotion ratings, SIRs, and details

To explore the influence of emotional arousal at the time of exposure to the stimuli on subsequent SIRs and memory, we performed regression analyses relating mean emotional arousal ratings to mean SIRs reported per film and mean details recalled per film. Analyses combining subjects in both emotional and neutral conditions revealed significant positive correlations between emotional arousal ratings and SIRs (R2 = 0.33, R = 0.57, p <.0001) as well as emotional arousal ratings and details (R2 = 0.38, R = 0.62, p <.0001).

A multiple regression analysis revealed that a model combining SIR frequency and emotion ratings (R2 = 0.44, adjusted R2 = 0.42, R = 0.66, p <.0001) predicted the number of recalled details better than univariate models considering either SIR frequency (R2 = 0.32, R = 0.57, p <.05) or emotion ratings (R2 = 0.15, R = 0.39, p <.01) alone. Within the bivariate model the factor with the most weight was emotion ratings (β = 0.42; β = 0.32 for SIR frequency).

Sex Effects in the Relationship between SIRs and memory strength

Although, as indicated above, there were no significant effects of sex on either the overall incidence of SIRs or on the number of films or film details recalled, we also determined whether sex significantly influenced the relationship between SIRs and memory strength (i.e. subjective rank). A 2 (Condition) × 5 (Subjective Rank) × 2 (Sex) ANOVA of the mean number of SIRs for the five best remembered films revealed main effects of Condition, [F(1, 205) = 21.33, p <.0001], Subjective Rank [F(4, 205) = 7.18, p <.0001], Sex [F(1, 205) = 5.44, p <.05] and a trend toward a Condition × Subjective Rank interaction [F(4, 205) = 1.96, p = 0.09]. Participants in the emotional condition reported more SIRs than did those in the neutral condition, women reported more SIRs than men, and more SIRs were reported for the films subjectively rated as better remembered.

Menstrual Phase Effects

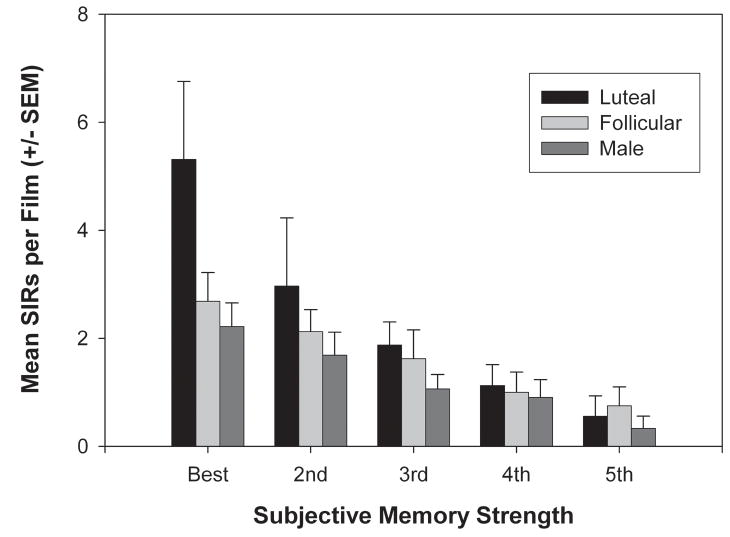

A 2 (Condition) × 5 (Subjective Rank) × 3 (Menstrual Phase) ANOVA of the mean number of SIRs for the first five best remembered films revealed main effects of Condition [F(1,195) = 26.73, p <.0001], Subjective Rank [F(4,195) = 10.07, p <.0001], and Menstrual Phase [F(2,195) = 4.45, p <.05], as well as a Condition × Subjective Rank interaction [F(4, 195) = 3.220, p <.05]. Women in the luteal phase reported more SIRs for the five best remembered films than did either men or women in the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle (see Figure 4), and Fisher’s PLSD post-hoc tests revealed that these differences were significant [luteal vs. men, p =.001; luteal vs. follicular, p <.05].

Figure 4.

Menstrual phase and sex effects in the relationship between SIRs and subjective memory strength, with data from emotional and neutral conditions combined for clarity. Women in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle report more SIRs than women in the follicular phase (p <.05) or men (p =.001), and the latter two groups do not differ (p >.05).

DISCUSSION

The primary finding from this study is that a heightened incidence of spontaneous intrusive recollections (SIRs) after viewing short film clips is associated with greater subjective long-term memory strength under both emotional and neutral film conditions, and that emotional stimuli are associated with both increased SIR frequency and enhanced detail of memory at recall. These findings are consistent with the possibility that the elaboration and rehearsal properties associated with SIRs may serve to strengthen memory for any stimuli that evoke them, but that emotional stimuli increase SIR frequency, which may in turn serve to enhance memory for emotional stimuli. The finding of a significant relationship between SIRs and detail memory under emotional but not neutral conditions raises the possibility that covert, spontaneous recollections occurring after an emotional event may help to explain why such events are remembered especially well. When neutral stimuli are associated with SIRs, these rehearsals are likely to contribute to enhanced memory for these stimuli as well, but it appears that the relationship between SIR frequency and memory is more robust under emotional conditions. The fact that the correlation between intrusion frequency and details is observed under emotional but not neutral conditions may reflect the fact that the emotional stimuli are associated with both a much broader range and generally higher rates of intrusion frequencies than neutral stimuli. Because there is less variability in the frequency of SIRs in the neutral group, a relationship between details and intrusion frequency is likely more difficult to detect under neutral conditions. While it may seem intuitively plausible that emotional arousal drives SIRs moreso for emotional than neutral events, and that such intrusive recollections are associated with stronger memory, this study is the first of which we are aware to directly demonstrate such a relationship.

Several factors strongly suggest that the quantification of SIRs by our subjects was not simply a consequence of the demand characteristics of the study. First, the subjective ranking of memory strength for the films related significantly to the number of details recalled for those films. Second, in order to further separate the subjective memory strength rankings and the SIR estimates, subjects were asked to complete a task indicating the order in which films were viewed. Third, subjects were asked to estimate SIR frequency for each film in a pseudorandom order, making it difficult or impossible for them to intentionally adjust their responses to a given film. Fourth, subjects uniformly responded to the SIR frequency inquiry in a rapid, confident manner, displaying nothing in their mannerisms to indicate that they were intentionally manipulating their responses, and leaving them little or no time to do so as well. Finally, subjects were also misled into believing that no memory test would occur, but that we were instead interested only in physiological measurements of emotion. Thus, all subjects remained unaware of the true nature of the study until after their assessment of SIR incidence was obtained and they were thoroughly debriefed. Considering these facts together, it is very unlikely that these findings were influenced in any meaningful way by the experimental demand characteristics.

Unlike some other studies of rumination (Holmes, Brewin, & Hennessy, 2004), subjects in the present study were not asked to keep rumination diaries, but rather to estimate the frequency of SIRs for each film. We employed this approach in order to eliminate the confounding effects of additional intentional elaboration or rehearsal caused by recording each individual instance of rumination in a diary. In order to promote relative accuracy of SIR estimation, the retention interval was relatively short (48 hours) compared to the one-week interval typically used in our previous studies of emotional memory. Subjects in our conditions appeared to have little difficulty in estimating SIR frequency. Indeed, after-the-fact descriptions of the content of intrusive thoughts and memories have been successfully used in several previous investigations of rumination in clinical and nonclinical populations (Brewin, Christodoulides, & Hutchinson, 1996; Reynolds & Brewin, 1998; Steil & Ehlers, 2000). Because we used retrospective estimations of intrusion frequency instead of diaries, we cannot rule out the possibility of a confound between strength of recall of SIRs and the true frequency of SIRs. In other words, it is possible that subjects reported more SIRs in the emotional condition because SIRs for emotional films are inherently more memorable or accessible to free recall than are those for neutral films, although we are not aware of any evidence that this is the case. It seems that the only way to be absolutely certain of the true frequency of intrusions is to record each instance of intrusion in a diary, but we elected not to do this for the reasons mentioned above.

In a study designed to determine the effect of concurrent tasks on the formation of intrusive memories, Holmes, Brewin, and Hennessy (2004) measured rumination frequency and memory after subjects viewed emotional stimuli. These authors failed to detect significant relationships between intrusive memory frequency and their recall or recognition measures; however, this study differed from the present study in many respects. For example, the explicit memory measures used differed substantially between the two studies. The recall task used by Holmes et al. (2004) involved the use of directed questions to cue memory for specific aspects of stimuli, whereas the present study employed a more traditional free recall test in which subjects were asked to recall any information from the previously seen stimuli. Perhaps when subjects are asked to guide their own recall there is greater association between intrusive recollections and memory. Additionally, the present study determined strength of memory by subjective assessment in each participant as well as more objective measures such as the listing of remembered details. This approach is perhaps more sensitive to detecting effects of SIRs than traditional recognition or guided recall tests. Also, Holmes et al. (2004) asked their subjects to keep diaries of intrusion content, and it is possible that the additional overt rehearsal opportunities caused by recording intrusions into the diary may have obscured the relationship between the covert rehearsals themselves and subsequent long-term memory.

In another recent study, enhanced short-term memory for emotional versus neutral pictures persisted even under conditions in which selective rumination was assumed to be prevented by a distractor task (Harris & Pashler, 2005). The results of this study also do not necessarily conflict with those from the current study, since the two studies again differed in many respects. For example, Harris and Pashler (2005) used an extremely short delay between encoding and memory testing, and their testing was of an intentional nature, unlike the more naturalistic incidental memory test utilized in the current study. Furthermore, negative results in the limited conditions of Harris and Pashler (2005) do not, of course, signify that rumination is unrelated to memory for emotional stimuli in other conditions.

Because depression and PTSD, two disorders characterized in part by an increased tendency toward intrusive thoughts and memories, are much more common among women than in men, it was perhaps not surprising that women in the current study reported more SIRs for their best-remembered films than did men. While our subjects obviously did not develop PTSD after viewing our film stimuli, the films were sufficiently arousing to cause intrusions. Given that intrusions are one of the key clinical features of PTSD, our results would seem to have some clinical relevance. In fact, the sex differences observed in this study may reflect an increased likelihood of women to experience post-event SIRs, which may in turn contribute to a higher susceptibility to develop PTSD compared to men. Although women rated the emotional films higher than did men, women did not on average experience more SIRs, recall more films, or recall more details. In fact, a sex effect emerged only in an analysis of the relationship between SIRs and subjective memory strength, and this effect appeared to be driven by an increase in the number of reported SIRs for the best-remembered film in women compared to men. It is plausible that the magnitude of the difference in emotional arousal between men and women may not have been large enough to allow us to detect a corresponding sex difference in overall SIRs or detail memory. This is an issue that should be addressed in future studies of this type. In fact, our findings of menstrual phase effects suggest that in order to more fully characterize sex effects, the potential influence of menstrual cycle position in female subjects should be considered.

An unexpected outcome of the present results was the influence of menstrual phase on frequency of SIRs after viewing emotional stimuli. This effect was particularly apparent for the stimuli which were best remembered, such that women in the luteal phase showed greater SIRs than women in the follicular phase for those stimuli that were best remembered. There are many indications that menstrual cycle position affects various aspects of cognition, including verbal and spatial performance (Halpern & Tan, 2001; Rosenberg & Park, 2002), patterns of brain activity during performance of cognitive tasks (Maki & Resnick, 2001), and the neural circuitry underlying the response to stress and arousal (Goldstein, et al, 2005). Further evidence suggests that menstrual phase position potentially affects both the stress response and the influence of stressors on memory performance (Kirschbaum et al., 1999; Andreano, Arjomandi & Cahill, 2008). However, the present results appear to be the first to suggest that position within the menstrual cycle might influence the frequency of SIRs. This intriguing observation could have important implications for understanding the pathology of post-traumatic stress disorder in women. For example, the current results raise the possibility that a woman’s position within the menstrual cycle at the time of a traumatic event may influence the likelihood of subsequently developing PTSD. This possibility of menstrual cycle position influences as a future direction in PTSD research has been raised by other investigators (Saxe & Wolfe, 1999; Rasmusson & Friedman, 2002; Milad et al., 2006), but to the best of our knowledge no formal investigation has been made. Although the SIRs experienced by our subjects appear to be similar in nature to intrusive memories in clinical settings in that both tend to involve visual experiences, the intrusive memories observed in PTSD are typically accompanied by significant distress and a feeling of reliving the events (Reynolds & Brewin, 1999). Because the distress levels associated with laboratory SIRs and intrusive memories in clinical samples are likely to be rather different, it important to be cautious when making claims about the potential clinical implications of these laboratory findings until further work is done exploring these results. Indeed, we intend to replicate and extend this finding of a menstrual phase effect in future experiments.

Our key finding of a relationship between SIRs and memory strength is correlational in nature, and as such can be interpreted in a number of ways. First, the results could reflect the fact that SIRs provide additional opportunities for rehearsal and thereby facilitate consolidation of emotional stimuli. Although that account seems rather plausible, we cannot exclude the possibility that certain films are initially associated with stronger memory and this enhanced memory causes subjects to experience more SIRs for those films. Some unpublished findings from a separate experiment in our lab, however, argue against this possibility. In female subjects, the level of salivary progesterone at the time of encoding is correlated with subsequent SIR frequency (manuscript in preparation). Because progesterone is correlated with SIR frequency but cannot be affected by initial memory strength, these findings suggest that an independent biological factor affects SIRs without being influenced by initial memory strength. This appears to provide evidence that initial memory strength alone cannot fully explain SIR frequency. It is also possible that another factor—emotional arousal is a likely candidate—leads to both more SIRs and enhanced detail memory. In fact, the observed relationships between arousal ratings and both SIRs as well as details may be viewed as supporting this interpretation. This does not rule out the possibility that emotional arousal leads to both increased SIRs and details, but that the additional rehearsal associated with SIRs contributes to the stronger memory seen under emotionally arousing conditions. The multiple regression analysis revealing that emotion ratings and SIR frequency, when considered together, predict the amount of recalled detail better than either factor alone suggests that some interaction between emotional arousal and covert rehearsal frequency is what ultimately determines memory strength.

In summary, the present findings represent the first experimental demonstration that emotional stimuli are associated with increased SIR frequency and that a relationship exists between intrusive recollections experienced after exposure to emotional stimuli and strength of memory for those stimuli. Despite the intuitive likelihood of such a relationship, it had to our knowledge never been demonstrated quantitatively. Having established this relationship, it is now possible to explore its neuroendocrine (sex and stress hormones) and neuroanatomical underpinnings. While the relationship between SIRs and memory strength observed in the present study seems unlikely to constitute a complete explanation of enhanced memory for emotional stimuli, it is certainly one promising candidate deserving of additional investigation.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Daniel Avesar for valuable assistance in data collection. This work was supported by NIMH grant RO1 MH 57808 to L.F.C.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andreano JM, Arjomandi H, Cahill L. Menstrual cycle modulation of the relationship between cortisol and long-term memory. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohannon JN., III Flashbulb memories for the space shuttle disaster: A tale of two theories. Cognition. 1988;29:179–96. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(88)90036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, Greenwald MK, Petry MC, Lang PJ. Remembering pictures: Pleasure and arousal in memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1992;18:379–90. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.18.2.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson EL, Schultz LR. Sex differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:1044–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230082012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Christodoulides J, Hutchinson G. Intrusive thoughts and intrusive memories in a nonclinical sample. Cognition & Emotion. 1996;10:107–12. [Google Scholar]

- Brown R, Kulik J. Flashbulb memories. Cognition. 1977;5:73–99. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L. Sex-related influences on the neurobiology of emotionally influenced memory. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;985:163–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L. Why sex matters for neuroscience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2006;7:477–84. doi: 10.1038/nrn1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L, Gorski L, Le K. Enhanced human memory consolidation with post-learning stress: Interaction with the degree of arousal at encoding. Learning & Memory. 2003;10:270–4. doi: 10.1101/lm.62403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L, Gorski L, Belcher A, Huynh Q. The influence of sex versus sex-related traits on long-term memory for gist and detail from an emotional story. Consciousness and Cognition. 2004;13(2):391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L, Haier RJ, Fallon J, Alkire MT, Tang C, Keator D, Wu J, McGaugh JL. Amygdala activity at encoding correlated with long-term, free recall of emotional information. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 1996;93:8016–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.8016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L, Haier RJ, White NS, Fallon J, Kilpatrick L, Lawrence C, Potkin SG, Alkire MT. Sex-related difference in amygdala activity during emotionally influenced memory storage. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2001;75:1–9. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2000.3999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L, McGaugh JL. A novel demonstration of enhanced memory associated with emotional arousal. Consciousness and Cognition. 1995;4:410–21. doi: 10.1006/ccog.1995.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canli T, Desmond JE, Zhao Z, Gabrieli JD. Sex differences in the neural basis of emotional memories. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2002;99:10789–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162356599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson S-A. The handbook of emotion and memory: Research and theory. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JM, Jerram M, Poldrack R, Ahern T, Kennedy DN, Seidman LJ, Makris N. Hormonal cycle modulates arousal circuitry in women using functional magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:9039–16. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2239-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy SC, Cahill L. The role of overt rehearsal in enhanced conscious memory for emotional events. Consciousness and Cognition. 1999;8:114–22. doi: 10.1006/ccog.1998.0379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern DF, Tan U. Stereotypes and steroids: Using a psychobiosocial model to understand cognitive sex differences. Brain and Cognition. 2001;45:392–414. doi: 10.1006/brcg.2001.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris CR, Pashler H. Enhanced memory for negatively emotionally charged pictures without selective rumination. Emotion. 2005;5 (2):191–99. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuer F, Reisberg D. Vivid memories of emotional events: the accuracy of remembered minutiae. Memory & Cognition. 1990;18:496–506. doi: 10.3758/bf03198482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EA, Bourne C. Inducing and modulating intrusive emotional memories: A review of the trauma film paradigm. Acta Psychologica. 2008;127:553–66. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EA, Brewin CR, Hennessy RG. Trauma films, information processing, and intrusive memory development. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2004;133 (1):3–22. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.133.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Thornton LM, Prescott CA. Gender differences in the rates of exposure to stressful life events and sensitivity to their depressogenic effects. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:587–93. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kensinger EA, Corkin S. Memory enhancement for emotional words: Are emotional words more vividly remembered than neutral words? Memory & Cognition. 2003;31:1169–80. doi: 10.3758/bf03195800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Kudielka BM, Gaab J, Schommer N, Hellhammer D. Impact of gender, menstrual cycle phase, and oral contraceptives on the activity of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1999;61:154–62. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199903000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki PM, Resnick SM. Effects of estrogen on patterns of brain activity at rest and during cognitive activity: A review of neuroimaging studies. Neuroimage. 2001;14:789–801. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milad MR, Goldstein JM, Orr SP, Wedig MM, Klibanski A, Pitman RK, Rausch SL. Fear conditioning and extinction: Influence of sex and menstrual cycle in healthy humans. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2006;120(5):1196–1203. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.5.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:115–21. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmusson AM, Friedman MJ. Gender issues in the neurobiology of PTSD. In: Kimmerling R, Oimette P, Wolfe J, editors. Gender and PTSD. New York: The Guilford Press.; 2002. pp. 43–75. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds M, Brewin CR. Intrusive cognitions, coping strategies and emotional responses in depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and a non-clinical population. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;36:135–47. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds M, Brewin CR. Intrusive memories in depression and posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1999;37:201–15. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg L, Park S. Verbal and spatial functions across the menstrual cycle in healthy young women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2002;27:835–41. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00083-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DC, Friendly M. Predicting which words get recalled: Measures of free recall, availability, goodness, emotionality, and pronunciability for 925 nouns. Memory & Cognition. 1986;14:79–94. doi: 10.3758/bf03209231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxe G, Wolfe J. Gender and posttraumatic stress disorder. In: Saigh PA, Bremner JD, editors. Posttraumatic stress disorder: A comprehensive text. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.; 1999. pp. 160–79. [Google Scholar]

- Steil R, Ehlers A. Dysfunctional meaning of posttraumatic intrusions in chronic PTSD. BehaviourResearch and Therapy. 2000;38:537–58. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson CB. Aftermath of a disaster: The collapse of the Hyatt Regency Hotel skywalks. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1983;140:1134–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.9.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]