Abstract

In addition to specific changes in cis- and trans-regulatory elements, structural changes in the genome are hypothesized to underlie a large number of differences in gene expression between species. Accordingly, we show that species-specific segmental duplications are enriched with genes that are differentially expressed between humans and chimpanzees.

CHANGES in gene regulation have likely played an important role in evolution, including in primates (Britten and Davidson 1971; King and Wilson 1975; Carroll et al. 2001; Cresko et al. 2004; Gilad et al. 2006b; Carroll 2008). In addition to changes in cis- and trans-regulatory elements, a possible mechanism that might explain differences in gene regulation between species may be structural changes in the genome, such as chromosomal rearrangements, segmental duplications, and copy number variation (e.g., Haberer et al. 2004; Huminiecki and Wolfe 2004; Teichmann and Babu 2004; Force et al. 2005). In primates, some measure of support for this idea was found in the observation that human-specific large-scale chromosomal rearrangements are slightly, but significantly, enriched with genes that are differentially expressed between humans and chimpanzees (Khaitovich et al. 2004; Blekhman et al. 2008).

In this context, it is interesting to investigate the contribution of smaller-scale structural genomic differences, such as segmental duplications (Bailey et al. 2002; She et al. 2006), to differences in gene expression between humans and chimpanzees. Previous microarray studies reported that duplicated genes, in either human or chimpanzee, tend to be highly expressed in the species in which the duplication has occurred (Khaitovich et al. 2004; Cheng et al. 2005). This observation probably reflects the fact that, unless specific measures are taken, duplicated genes are expected to cross-hybridize to the same probes and therefore their expression level may appear elevated. In that sense, previous observations cannot exclude a technical, rather than a biological, explanation for the enrichment of differentially expressed genes in segmental duplications. Moreover, previous studies used multispecies expression data that were collected using a single-species array. As a result, previous estimates of gene expression differences between species may be confounded by the effect of sequence mismatches on hybridization intensity (Gilad et al. 2005, 2006a; Sartor et al. 2006).

To study the effect of segmental duplications on the evolution of gene regulation in human and chimpanzee, we used previously published gene expression data from a genomewide multispecies array (Blekhman et al. 2008). Gene expression data were collected for 18,109 genes, from three tissues (liver, kidney, and heart), using 18 samples from each species. Genes that are differentially expressed between species were identified using likelihood-ratio tests in the framework of nested mixed linear models (Blekhman et al. 2008).

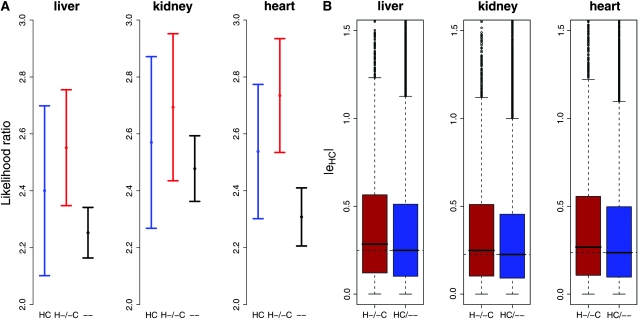

Using a data set of human and chimpanzee segmental duplications, we identified genes located within segmental duplications in one or both species (see supporting information, File S1 and Figure S1). Our approach was to compare estimates of interspecies gene expression differences between genes that are not associated with any duplication and genes within a segmental duplication in one or both species. Using this approach, we found that species-specific segmental duplications are enriched with genes that are differentially expressed between species, regardless of the tissue (P = 2.4 × 10−3, P = 0.057, and P = 5 × 10−4 in liver, kidney, and heart, respectively, by a permutation test on the medians; see File S1 and Figure 1A). Moreover, genes that are within species-specific segmental duplications (i.e., the duplicated genes) show significantly higher absolute fold difference in expression level between human and chimpanzee compared with genes that are not associated with duplications (P < 10−3 in all tissues; Figure 1B and Figure S5).

Figure 1.—

Expression divergence is associated with segmental duplications. (A) Medians of the likelihood-ratio values for testing differential expression between human and chimpanzee. Black, 11,822 genes not associated with duplications (–); blue, 1715 genes associated with duplications in both species (HC); red, 3084 genes associated with either human-specific (H-) or chimpanzee-specific (-C) duplications. The error bars are 95% confidence intervals calculated using bootstrapping (1000 repetitions). See File S1 for more information on the statistical analyses. (B) Box plots of estimates of absolute log fold change in gene expression between the species for liver, kidney, and heart. These estimates were generated using linear models for each species (see File S1); the difference in expression level was estimated as |eHC| = |μh − μc|, which is the absolute value of the difference between the log expression level estimates of humans and chimpanzees. The difference between the two distributions is significant in all tissues (P < 10−3, using a permutation test on the difference in medians).

A possible explanation for the observation that species-specific segmental duplications are enriched with genes that are differentially expressed between humans and chimpanzees is cross-hybridization. For example, if there are more copies of gene A in the human genome compared to the chimpanzee genome (i.e., gene A is within a human-specific duplication), one might expect mRNA transcribed from all copies of gene A to cross-hybridize to the same probe set on the array, resulting in an apparent elevated expression level of gene A in humans compared with chimpanzees.

While increased dosage is an intuitive mechanism by which duplications affect gene regulation, we also wanted to address the possibility that duplications may affect gene regulation independently of simple dosage effects—perhaps due to changes in the proximal regulatory elements that affect the expression of duplicated genes. To do so, we looked for evidence of cross-hybridization by plotting the difference between the values of eHC = μh − μc (i.e., the difference in log expression level between humans and chimpanzees) across the three categories of genes mentioned above. If cross-hybridization underlies most interspecies differences in expression for genes within species-specific segmental duplication, one would expect genes within human-specific duplications to have eHC > 0 and genes within chimpanzee-specific duplications to have eHC < 0.

Importantly, we do not find a trend toward elevated expression levels for genes within species-specific duplications. The proportions of genes with elevated expression level in the species with the duplication are 0.49, 0.48, and 0.49, for genes in liver, kidney, and heart, respectively (Figure S2). We note that some genes within duplications are mapped to regions that are also variable in copy number between individuals. Thus, such genes may not in fact be duplicated in the individuals considered in this study and therefore would not be expected to show elevated expression level in the species with the annotated duplication. However, our observations are virtually unchanged when we exclude genes within segmental duplication that are known to overlap copy number variable regions in humans and chimpanzees (Perry et al. 2008) (Figure S6, Figure S7, and Figure S8).

Thus, cross-hybridization is unlikely to explain the observed association between species-specific segmental duplications and interspecies gene expression differences. In other words, our observations cannot be explained by a simple dosage effect as a result of gene duplications. Instead, it is reasonable to assume that orthologous genes within species-specific duplications are regulated by a different set of elements, as their proximal genomic environment has changed (Haberer et al. 2004; Force et al. 2005; Conrad and Antonarakis 2007). In such cases, duplications may have resulted in the introduction of proximal enhancers, repressors, or boundary regulatory elements, which can result in a shift of expression level in both directions.

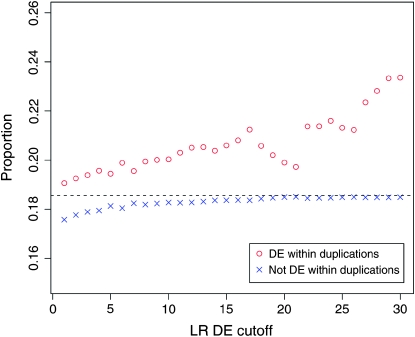

Next we wanted to assess the contribution of segmental duplications to the overall differences in gene regulation between humans and chimpanzees. To do so, we calculated the proportion of genes within species-specific duplications among genes that are differentially expressed between the species. Because such a comparison depends on the statistical cutoff chosen to classify genes as differentially expressed, we examined a wide range of possible cutoffs. Interestingly, regardless of the cutoff chosen (in all tissues), the proportion of genes in segmental duplications is always higher for genes that are classified as differentially expressed between humans and chimpanzees compared with genes that are classified as not differentially expressed between the species (Figure 2 and Table S3). Moreover, the proportion of genes within species-specific duplications is higher when more stringent statistical cutoffs are used to classify genes as differentially expressed between the species. Thus, our analysis suggests that segmental duplications might explain as least 2%, but perhaps as much as 8%, of differences in gene expression between humans and chimpanzees (in the three adult tissues studied here; Figure 2, Figure S3, and Figure S4).

Figure 2.—

The proportion of genes within species-specific segmental duplications (y-axis) is plotted at different likelihood-ratio cutoffs (x-axis) for classifying genes as differentially expressed (DE) between species, using the liver expression data (red circles). The proportion of genes within species-specific segmental duplications among genes that are not classified as differentially expressed (based on the different cutoffs) is plotted with blue x's. The overall proportion of genes within species-specific duplications is shown by the dashed horizontal line. Similar plots using the kidney and heart expression data are available as Figure S3 and Figure S4, respectively.

Finally, we examined the known functions of genes within species-specific segmental duplication (see File S1). We found that human-specific duplications are somewhat enriched with transcription factors and genes in metabolic pathways compared with chimpanzee-specific duplications (Table S1). This enrichment becomes much more pronounced when we also condition on observing a difference in gene expression levels between the species. Indeed, transcription factors and genes in metabolic pathways are the top gene ontology categories that are overrepresented among genes that are differentially expressed between the species and are within human-specific duplications (Table S2). This result is consistent with our previous observations of overrepresentation of transcription factors and metabolic genes among genes whose regulation likely evolves under directional selection exclusively in humans (Gilad et al. 2006b; Blekhman et al. 2008), although, importantly, the genes that underlie the two observations are not the same.

In summary, our results provide support for a role of segmental duplications in shaping the evolution of gene regulation. Further, our observations suggest that genes within species-specific duplications are more likely to have either reduced or elevated expression levels compared with genes not associated with duplications. A possible explanation may be that the expression levels of genes within species-specific segmental duplications are affected by different proximal cis-regulatory elements compared with those of orthologous genes in their original genomic location.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Perry, L. Barreiro, R. Bainer, and C. Cain for helpful discussions and J. Marioni, Z. Gauhar, and N. Zeus for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Sloan Foundation and National Institutes of Health grant GM077959 to Y.G.

Supporting information is available online at http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/genetics.108.099960/DC1.

References

- Bailey, J. A., Z. Gu, R. A. Clark, K. Reinert, R. V. Samonte et al., 2002. Recent segmental duplications in the human genome. Science 297 1003–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blekhman, R., A. Oshlack, A. E. Chabot, G. K. Smyth and Y. Gilad, 2008. Gene regulation in primates evolves under tissue-specific selection pressures. PLoS Genet. 4 e1000271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten, R. J., and E. H. Davidson, 1971. Repetitive and non-repetitive DNA sequences and a speculation on the origins of evolutionary novelty. Q. Rev. Biol. 46 111–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, S. B., 2008. Evo-devo and an expanding evolutionary synthesis: a genetic theory of morphological evolution. Cell 134 25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, S. B., J. K. Grenier and S. D. Weatherbee, 2001. From DNA to Diversity: Molecular Genetics and the Evolution of Animal Design. Blackwell Scientific, Malden, MA.

- Cheng, Z., M. Ventura, X. She, P. Khaitovich, T. Graves et al., 2005. A genome-wide comparison of recent chimpanzee and human segmental duplications. Nature 437 88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, B., and S. E. Antonarakis, 2007. Gene duplication: a drive for phenotypic diversity and cause of human disease. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 8 17–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresko, W. A., A. Amores, C. Wilson, J. Murphy, M. Currey et al., 2004. Parallel genetic basis for repeated evolution of armor loss in Alaskan threespine stickleback populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101 6050–6055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Force, A., W. A. Cresko, F. B. Pickett, S. R. Proulx, C. Amemiya et al., 2005. The origin of subfunctions and modular gene regulation. Genetics 170 433–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilad, Y., S. A. Rifkin, P. Bertone, M. Gerstein and K. P. White, 2005. Multi-species microarrays reveal the effect of sequence divergence on gene expression profiles. Genome Res. 15 674–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilad, Y., A. Oshlack and S. A. Rifkin, 2006. a Natural selection on gene expression. Trends Genet. 22 456–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilad, Y., A. Oshlack, G. K. Smyth, T. P. Speed and K. P. White, 2006. b Expression profiling in primates reveals a rapid evolution of human transcription factors. Nature 440 242–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberer, G., T. Hindemitt, B. C. Meyers and K. F. Mayer, 2004. Transcriptional similarities, dissimilarities, and conservation of cis-elements in duplicated genes of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 136 3009–3022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huminiecki, L., and K. H. Wolfe, 2004. Divergence of spatial gene expression profiles following species-specific gene duplications in human and mouse. Genome Res. 14 1870–1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaitovich, P., B. Muetzel, X. She, M. Lachmann, I. Hellmann et al., 2004. Regional patterns of gene expression in human and chimpanzee brains. Genome Res. 14 1462–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, M. C., and A. C. Wilson, 1975. Evolution at two levels in humans and chimpanzees. Science 188 107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry, G. H., F. Yang, T. Marques-Bonet, C. Murphy, T. Fitzgerald et al., 2008. Copy number variation and evolution in humans and chimpanzees. Genome Res. 18 1698–1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor, M. A., A. M. Zorn, J. A. Schwanekamp, D. Halbleib, S. Karyala et al., 2006. A new method to remove hybridization bias for interspecies comparison of global gene expression profiles uncovers an association between mRNA sequence divergence and differential gene expression in Xenopus. Nucleic Acids Res. 34 185–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She, X., G. Liu, M. Ventura, S. Zhao, D. Misceo et al., 2006. A preliminary comparative analysis of primate segmental duplications shows elevated substitution rates and a great-ape expansion of intrachromosomal duplications. Genome Res. 16 576–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teichmann, S. A., and M. M. Babu, 2004. Gene regulatory network growth by duplication. Nat. Genet. 36 492–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]