Abstract

The active DNA-dependent ATPase A domain (ADAAD), a member of the SWI2/SNF2 family, has been shown to bind DNA in a structure-specific manner, recognizing DNA molecules possessing double-stranded to single-stranded transition regions leading to ATP hydrolysis. Extending these studies we have delineated the structural requirements of the DNA effector for ADAAD and have shown that the single-stranded and double-stranded regions both contribute to binding affinity while the double-stranded region additionally plays a role in determining the rate of ATP hydrolysis. We have also investigated the mechanism of interaction of DNA and ATP with ADAAD and shown that each can interact independently with ADAAD in the absence of the other. Furthermore, the protein can bind to dsDNA as well as ssDNA molecules. However, the conformation change induced by the ssDNA is different from the conformational change induced by stem-loop DNA (slDNA), thereby providing an explanation for the observed ATP hydrolysis only in the presence of the double-stranded:single-stranded transition (i.e. slDNA).

INTRODUCTION

DNA-dependent ATPases utilize the energy released by ATP hydrolysis to facilitate DNA-metabolic processes (1–4). During these processes, the nucleic acid might be modified (i.e. as for a helicase) or remain unmodified, and thus function as an effector (i.e. SWI2/SNF2 ATPases). DNA-dependent ATPase A, also known as SMARCAL1, is a member of the SWI2/SNF2 family of DNA-dependent ATPases. It hydrolyzes ATP only in the presence of a DNA effector (5,6). Furthermore, the enzyme interacts with DNA in a structure-specific manner, recognizing double-stranded to single-stranded transition regions (5). These structural elements are common physical features of those regions of chromosomes where replication, repair, recombination or transcription processes occur: processes where proteins of the SWI2/SNF2 family of DNA-dependent ATPases have been shown to be essential (7,8).

All members of SWI2/SNF2 family possess seven helicase-related motifs that form a catalytic domain necessary to mediate DNA binding and ATP hydrolysis (9). However, none, including DNA-dependent ATPase A, has been demonstrated to possess DNA-unwinding activity (10). Instead these proteins use the energy from ATP hydrolysis to remodel chromatin (11–13).

The role of the seven helicase-related motifs in DNA binding and ATP hydrolysis in DEAD box enzymes and SWI2/SNF2 proteins, both members of SF2 superfamily, has been analyzed through genetic, biochemical and structural analysis. Mutational analysis of eukaryotic initiation factor, eIF-4A, indicates that motif VI is required for RNA binding and ATP hydrolysis (14). Furthermore, mutations in motif I (GKT box) and motif II (DEAD box) affect ATP binding and hydrolysis (15). Functional analysis of Has1p also confirms these results (16). Additionally, Has1p is maximally stimulated by rRNA and poly(A) RNA, though the structural requisites for maximal stimulation have not been delineated (16). FRET studies with SsoRad54cd suggest that binding to a DNA effector drives conformational changes in the protein (17).

Studies using overexpressed ADAAD have led to the suggestion that these helicase-related motifs are not bona fide helicase motifs but formulated recognition mechanisms for specific DNA structural elements (5,18). The SWI2/SNF2 proteins show wide diversity vis-à-vis DNA effectors. For example, Snf2p is stimulated by both naked DNA and nucleosomal DNA, while ISWI recognizes only nucleosomal DNA and Rad54 is a dsDNA-stimulated ATPase (18–20). Mot1p binds TBP–DNA complex, while DNA-dependent ATPase A specifically recognizes DNA molecules possessing double-stranded to single-stranded transition regions (5,21). These proteins show extensive homology only in their seven-helicase motifs. From a physicochemical perspective, these observations lead to the question of how these protein molecules recognize different DNA molecules and translate that sequence-independent recognition into ATP hydrolysis.

In this article we have used ATP hydrolysis assays and fluorescence spectroscopy to identify elements of the mechanism of interaction between ADAAD and its DNA effector that results in ATP hydrolysis. We show that ADAAD can bind to DNA in the absence of ATP and conversely, to ATP in absence of DNA. The resulting [E.ATP] or [E.DNA] complex can then interact with the other ligand to form a ternary complex. We further show that there is an order to the interaction with ATP and DNA such that only the ternary complex formed by the interaction of DNA with ADAAD prior to interaction with ATP yields productive ATP hydrolysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

ATP was procured from GE Biosciences (USA); all other chemicals were from Merck, Qualigens, or Sigma Aldrich (USA). Oligonucleotides possessing a 3′ hydroxyl were synthesized either by Sigma-Aldrich (USA), the University of Virginia's Biomolecular Research Facility or by Integrated DNA Technologies, USA.

Protein

The ATP hydrolysis data, unless otherwise specified, was generated using bacterially expressed ADAAD purified as per Muthuswami et al. (5). Fluorescence measurements were executed using His-tagged ADAAD. Both ADAAD and His-ADAAD showed similar KDNA for the reference DNA effector, oligonucleotide 950 (Table 1).

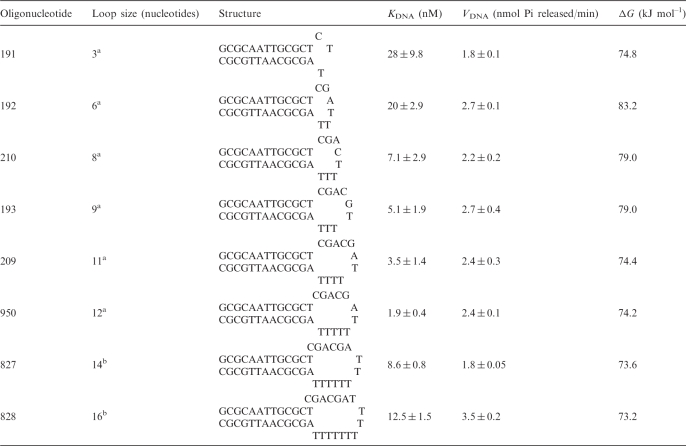

Table 1.

Effect of increasing loop size of the stem-loop DNA effector on KDNA and VDNA

|

Stem-loop DNA oligonucleotides containing 13 bp stem length but differing loop sizes, and closed by an AT bp were used for estimating binding constants. The oligonucleotides were heated to 70°C for 3 min and quickly cooled to 4°C prior to using them in the assays. Oligonucleotides are listed in the increasing order of loop sizes. ΔG has been calculated using the method of Breslauer et al. (26).

aADAAD was purified as described in Muthuswami et al. ATPase activity was measured by colorimetric method.

bHis-tagged ADAAD protein was used in these assays. ATPase activity was measured using NADH oxidation assay.

Purification of His-tagged ADAAD

The gene sequence encoding ADAAD was moved from the original plasmid pRM102 into pCP101 to yield a protein, His-ADAAD. The protein was purified as described in Supplementary Data, File 1.

Protein estimation

Protein was estimated using Bradford reagent as well as by measuring absorbance at 280 nm (22).

Calculation of the free energy of the oligonucleotides

The optimal structures of the oligonucleotides were predicted using Mfold (23–25) and the possible free energies for their destabilization were calculated per Breslauer et al. (26). The free energies for loop formation were calculated per Bloomfield et al. (27).

ATPase assays

The activity of the enzyme was measured either using the colorimetric assay described in Hockensmith et al. (10) or by coupling NADH oxidation to ATP hydrolysis (28). The data used was an average of each experiment done in triplicates. Oligonucleotide 950 from Muthuswami et al. (5) was used as the reference effector.

Calculation of the binding constants using ATPase activity

The model used to calculate the apparent dissociation constant is described in Supplementary Data, File 1.

Fluorescence measurements

His-ADAAD (0.37 μM) was excited at 295 nm and emission recorded between 310 and 400 nm at 25°C (details in Supplementary Data, File 1). Upon titration with ligand all spectra were corrected for buffer background, dilution (≤10% of the sample volume) and inner filter effects (see Supplementary Data, File 1). All binding data were analyzed using a one-site saturation model (details in Supplementary Data, File 1).

Fluorescence quenching using acrylamide

Protein samples were titrated with small aliquots of a 5 M acrylamide solution. The observed Trp emission intensities at 340 nm were used to obtain Stern–Volmer (SV) plots as well as modified SV plots. The equations for these plots are provided in Supplementary Data, File 1.

Deriving a theoretical framework for ATP hydrolysis by ADAAD in presence of slDNA

Four models were derived to understand the mechanism by which ATP is hydrolyzed by ADAAD in presence of slDNA (Supplementary Data, File 1).

RESULTS

Previously we showed that ADAAD hydrolyzes ATP maximally in the presence of slDNA (5). We now extend these studies to refine the definition of the double-stranded and single-stranded regions of slDNA required for maximal activity.

The length of the single-stranded region of the DNA effector contributes to the overall dissociation constant for ADAAD–DNA interaction

Using our earlier observations that a slDNA possessing a 12 base loop and a 13 bp stem is a good effector (5), we chose this molecule as a platform to explore the importance of the length of the single-stranded region for the activity of ADAAD.

Eight different slDNA constructs were synthesized by varying the single-stranded region (loop size) from 3 bases to 16 bases (Table 1). Measurement of ATP hydrolysis affected by these oligonucleotides demonstrated that as the loop size increases KDNA decreases until the loop size reaches ∼12 bases, with no coincident change in the VDNA (Table 1, Supplementary Figure 1A). Thereafter, increases in loop size resulted in increases in KDNA. Thus, any variation in single-stranded length below or above 12 nt has a demonstrable effect, with KDNA increasing by a factor of 10 for loop sizes shorter than 8 nt (Table 1, Supplementary Figure 1B).

The ability of a replication fork or a flayed molecule to induce ATP hydrolysis by ADAAD was also monitored. Both molecules can bind and induce ATP hydrolysis. However, neither are optimal effectors for ADAAD as suggested by the higher KDNA for these molecules compared to slDNA possessing a 12 base loop (Supplementary Table 1).

The double-stranded region of the DNA effector is important for binding and ATP hydrolysis

In order to evaluate the contribution of the double-stranded region of the slDNA to the ADAAD–DNA interaction, we examined (i) the nucleotide pair closing the loop and (ii) the length of the double-stranded stem of the slDNA. The nucleotide pair closing the loop was found to have a critical effect on KDNA. That is, given two DNA molecules with single-stranded regions of less than optimal length the enzyme can maximize favorable protein:ssDNA interactions by melting into the DNA but only at the cost of protein:dsDNA interactions. (Supplementary Table 2, experimental details and results are provided in Supplementary File 1).

Similarly to the findings of an optimal length for the single-stranded region, we found that the optimal length of the double stranded region was 13 bp and that the length of the double-stranded region is critical both for KDNA and VDNA (Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Data, File 1).

The 3′-terminal but not the 5′-terminal moiety plays an important role in the ADAAD–DNA interaction

Previously we have shown that gapped or nicked DNA, with 3′-hydroxyl ends, are effectors of DNA-dependent ATPase A (10). However, micrococcal nuclease digested DNA which have 3′-phosphate ends cannot effect ATP hydrolysis. Furthermore, ADAAD can distinguish between a 3′- and a 5′-recessed terminus (5). Using paired oligonucleotides with and without 3′-phosphates we confirmed that the 3′-hydroxyl is the preferential end moiety to effect ATP hydrolysis (Supplementary Table 3 details provided in Supplementary Data, File 1).

ssDNA can compete for binding

Our previous experimental data showed that neither ssDNA nor dsDNA is an effector for ATP hydrolysis (5). Therefore, we used ssDNA molecules containing either 3′-OH or 3′-PO4 to assess their ability to inhibit ATP hydrolysis in the presence of slDNA (oligonucleotide 950). We found ssDNA molecules capable of inhibiting ATP hydrolysis only at concentrations a thousand-fold higher than the effector concentrations (Supplementary Figure 4).

Fluorescence spectrum of ADAAD

We employed fluorescence spectroscopy, a technique previously used to study protein–DNA interactions, to understand the interaction of ADAAD with its ligands, ATP and DNA (29–31). ADAAD contains 13 Trp residues and when excited at 295 nm, displays a Trp-specific fluorescence emission with a maximum at 340 nm, which is sensitive to the binding of both ATP and DNA (oligonucleotides shown in Supplementary Table 4). Representative spectra for ATP and DNA titration are provided in Supplementary Figure 5.

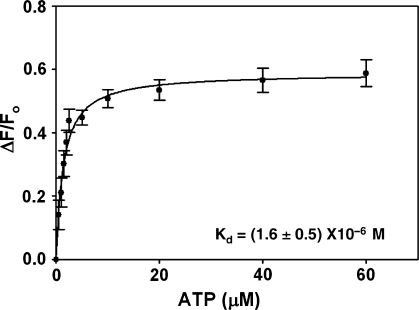

Binding of ATP to ADAAD

To study the interaction of ATP with ADAAD, we titrated ADAAD with increasing concentrations of ATP and monitored fluorescence quenching. Analysis of the data using a one-site saturation model revealed a Kd of 1.6 ± 0.5 μM for the interaction (Figure 1, Table 2).

Figure 1.

Binding of ATP to ADAAD in absence of DNA. The data was fit to one-site saturation model and the Kd was calculated to be 1.6 ± 0.5 μM.

Table 2.

Kd values determined for ADAAD–DNA–ATP interaction using various models

| Conditions | One-site saturation analysis |

|

|---|---|---|

| Kd(M) | R2 | |

| +ATP | (1.6 ± 0.5) × 10−6 | 0.98 |

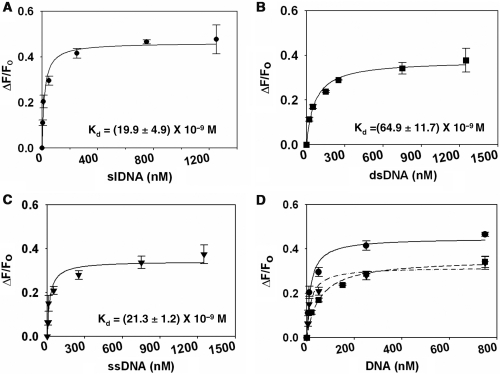

| +slDNA | (19.9 ± 4.9) × 10−9 | 0.98 |

| +dsDNA | (64.9 ± 11.7) × 10−9 | 0.98 |

| +ssDNA | (21.3 ± 1.2) × 10−9 | 0.95 |

| Presence of DNA | ||

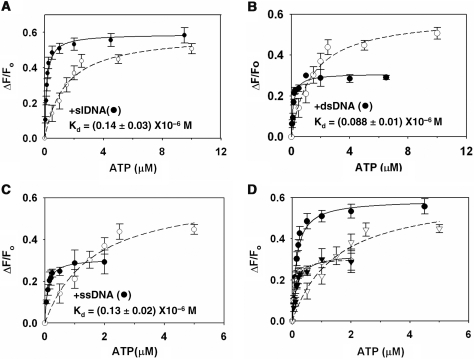

| +slDNA + ATP | (0.14 ± 0.03) × 10−6 | 0.96 |

| +dsDNA + ATP | (0.088 ± 0.01) × 10−6 | 0.99 |

| +ssDNA + ATP | (0.13 ± 0.02) × 10−6 | 0.96 |

| Presence of ATP | ||

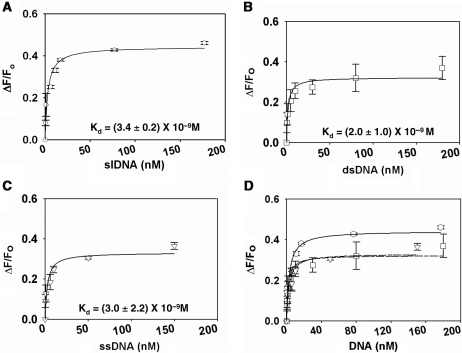

| +slDNA | (3.4 ± 0.2) × 10−9 | 0.97 |

| +dsDNA | (2.0 ± 1.0) × 10−9 | 0.94 |

| +ssDNA | (3.0 ± 2.2) × 10−9 | 0.93 |

n: Hill's coefficient. The Kd values are average of two separate experiments. The R2 value is reported for the representative figure.

Binding of DNA to ADAAD

To study the interaction of effector DNA with ADAAD, increasing concentrations of slDNA were titrated against ADAAD and fluorescence quenching monitored. Analysis of the data revealed a single binding site with Kd of 19.9 ± 4.9 nM (Figure 2A, Table 2).

Figure 2.

Binding of DNA to ADAAD in absence of ATP. (A) slDNA (filled circle). (B) dsDNA (filled square). (C) ssDNA (filled inverted triangle). (D) Comparison of binding of DNA to ADAAD in absence of ATP. (filled circle) slDNA; (filled square) dsDNA; (filled inverted triangle) ssDNA.

We next asked whether ssDNA or dsDNA with no discernible secondary structure could also bind to ADAAD. We used a 12 nt Mun I oligonucleotide identical to the 12 nt double-stranded DNA stem of the slDNA as an example of dsDNA (5). Oligonucleotide 496 was used as an example of ssDNA. Previous studies have shown that neither oligonucleotide elicits ATP hydrolysis by ADAAD. ADAAD was titrated with increasing concentrations of either oligonucleotide and it was found that both molecules could interact with the protein (Figure 2B and C, Table 2).

It is pertinent to note that the total amount of fluorescence quenching observed upon binding of dsDNA and ssDNA is only 72% that of slDNA binding to ADAAD (Figure 2D). It is possible that the dsDNA and ssDNA bind ADAAD in a mode or region different from that of slDNA and therefore differentially affect its Trp fluorescence.

ATP binding in the presence of slDNA

ADAAD can hydrolyze ATP only in the presence of its effector DNA. It is well known that DNA polymerases bind in a sequential manner; the protein interacts first with DNA and undergoes a conformational change that permits dNTP binding. Successive conformational changes result in polymerization (32). We postulated that ADAAD could also follow this kind of sequential interaction with DNA and ATP.

Hence, we studied the interaction of ATP in the presence of slDNA. ADAAD was saturated with slDNA and then titrated with ATP. We found that the Kd decreased 10-fold in the presence of DNA as compared to in its absence (Figure 3A, Table 2). The presence of slDNA, thus, greatly enhanced the affinity of ADAAD for ATP.

Figure 3.

Binding of ATP to ADAAD in presence of saturating concentration of DNA. (A) ADAAD was saturated with 3 μM slDNA. (B) ADAAD was saturated with 4 μM dsDNA. (C) ADAAD was saturated with 6 μM ssDNA. In all the graphs: (open circle) titration of ATP in absence of DNA and (filled circle) titration in presence of DNA. (D) Comparison of ATP binding to ADAAD in presence and absence of DNA. (open circle) absence of DNA, (filled circle) presence of slDNA, (open inverted triangle) presence of dsDNA and (filled inverted triangle) presence of ssDNA.

Since slDNA effects ATP hydrolysis by ADAAD, it is possible that the above results do not describe true dissociation constants. Therefore, we estimated ATPase activity of ADAAD under these conditions (25°C without an ATP regeneration buffer) and found minimal ATP hydrolysis (Supplementary Figure 6A). Additionally, we used an inactive mutant, K241A, where the invariant lysine in motif I was mutated to alanine. This mutant bound ATP and DNA similarly to ADAAD but did not hydrolyze ATP (Supplementary Table 5 and Supplementary Figure 6B).

ATP binding in presence of ssDNA and dsDNA

We next analyzed the interaction of ATP with ADAAD in presence of saturating concentrations of either ssDNA or dsDNA. We found that the affinity for ATP increased ∼10-fold (Figure 3B and C, Table 2). However, the maximal fluorescence quenching by ATP in the presence of ssDNA and dsDNA was 65% and 50%, respectively, of that seen with slDNA (Figure 3D), suggesting once again that the mode of interaction of these molecules with ADAAD is different from that of slDNA.

DNA binding in the presence of ATP

To study the binding of DNA in presence of ATP, ADAAD was saturated with ATP and slDNA was titrated in. Analysis of the data showed that the Kd decreased 6-fold (Figure 4A, Table 2).

Figure 4.

Binding of DNA to ADAAD in presence of saturating concentration of ATP. (A) Binding of slDNA (open circle) to ADAAD. Total 20 μM ATP was used for saturating the protein. (B) Binding of dsDNA (open square) to ADAAD in the presence of ATP. Total 40 μM ATP was used for saturating the protein. (C) Binding of ssDNA (open inverted triangle) to ADAAD in the presence of ATP. Total 40 μM ATP was used for saturating the protein. (D) Comparison of binding of DNA binding to ADAAD in presence of ATP. (open circle) slDNA, (open square) double-strand DNA and (open inverted triangle) ssDNA.

A similar decrease in Kd was observed when ADAAD saturated with ATP was titrated with either dsDNA or ssDNA (Figure 4B and C, Table 2). Again, notably, dsDNA and ssDNA caused only 70–80% fluorescence quenching as compared to slDNA, once more confirming that the interaction of both ssDNA and dsDNA with ADAAD is different as compared to slDNA (Figure 4D).

Thus we conclude that slDNA induces a conformational change in ADAAD that neither the ssDNA nor the dsDNA can effect.

Conformational changes in ADAAD monitored by fluorescence quenching with acrylamide

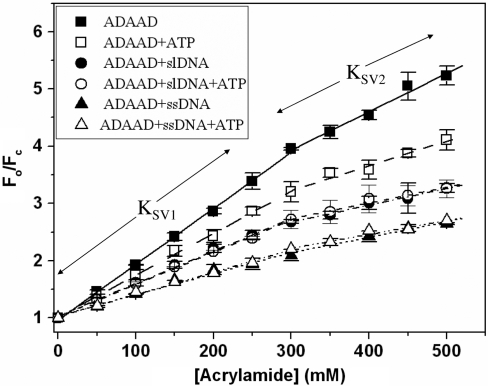

In order to explore whether our hypothesis of additional conformational change induced by the slDNA is borne out by our experimental system, we looked at the accessibility of ADAAD's Trp residues to acrylamide, a neutral quencher (33).

Titrating ADAAD with acrylamide resulted in significant fluorescence quenching (∼70%). The Stern–Volmer (SV) plots (Figure 5) for this quencher were biphasic, indicating that not all 13 Trp residues of the protein were equally accessible. As can also be seen from Figure 5 and Supplementary Table 6, one fraction of Trp residues was relatively easily accessed by acrylamide (KSV1 = 9.76 ± 0.10 M−1) while another set was less accessible (KSV2 = 6.70 ± 1.00 M−1). From modified SV plots, the fraction accessible to the quencher (fa) was estimated to be ∼95% with a SV constant for the accessible fraction (Ka) being 9.95 ± 0.05 M−1. In the presence of ATP, both KSV1 and KSV2 were reduced, as were the Ka values (Figure 5, Supplementary Table 6).

Figure 5.

Stern–Volmer plots. ADAAD was titrated with acrylamide in absence and presence of ATP and DNA. (Filled square) protein alone; (open square) in presence of saturating concentration of ATP; (filled circle) in presence of saturating concentration of slDNA; (open circle) in presence of saturating concentrations of slDNA and ATP; (filled triangle) in presence of ssDNA; and (open triangle) in presence of saturating concentration of ssDNA and ATP.

Interestingly, the binding of DNA to ADAAD also results in a very different set of KSV1, KSV2, fa and Ka values (Figure 5, Supplementary Table 6). Based on these results we postulate that the conformation of the protein in presence of ATP is different from that in presence of slDNA or ssDNA. Furthermore, the conformation of the protein in presence of slDNA is different from that in presence of ssDNA, thereby providing an explanation as to why ADAAD hydrolyzes ATP only in the presence of slDNA.

As ADAAD–slDNA and ADAAD–slDNA–ATP show similar SV quenching parameters, it appears that when both ligands are present, slDNA rather than ATP dictates the conformation of ADAAD (Figure 5, Supplementary Table 6).

It is possible that ATP/DNA themselves bind to the Trp residues and the quenching studies are not directly probing conformational changes. Hence, we considered accessibility of N-bromosuccinimide (NBS), to the Trp residues of ADAAD in the absence and presence of its ligands. If the Trp residues were within either ATP-/DNA-binding sites, the ligands would have physically blocked them from oxidation by NBS. Instead, the changes in the fluorescence spectra in the absence and presence of ligands were identical (Supplementary Figure 7), suggesting that the fluorescence quenching upon ligand binding is a result of conformational changes rather than direct interaction of the Trp residues with the ligands.

A theoretical model for ATP hydrolysis by ADAAD in presence of effector DNA

Based on the binding data, we formulated a model for the interaction of ADAAD with its ligands. ADAAD can bind to either ATP or DNA forming [E.ATP] or [E.DNA]. Interaction of [E.ATP] with DNA would result in [E.ATP.DNA] while interaction of [E.DNA] with ATP would result in [E.DNA.ATP] complex. Are these two complexes equivalent?

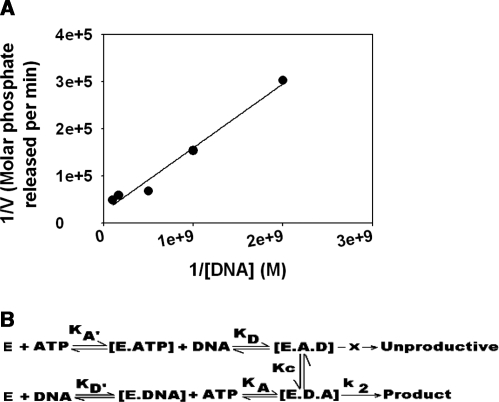

Fluorescence quenching studies suggest that DNA dictates the final conformation of the ternary complex indicating that [E.DNA.ATP] rather than [E.ATP.DNA] is the most likely ternary complex formed. To validate our hypothesis, we first plotted 1/v versus 1/[DNA] for ATP hydrolysis obtained using oligonucleotide 950 (Figure 6A) and employed the slope and the intercept values to calculate vmax and KATP (dissociation constant for ATP in presence of DNA). We then derived four equations based on four different models (see Supplementary Data File 1 for a full discussion). As shown in Table 3, the vmax and KATP values calculated using Model IV agrees very well with the experimentally determined values suggesting that ATP hydrolysis by ADAAD in the presence of slDNA occurs via the framework provided by Model IV.

Figure 6.

(A) Theoretical models for the interaction of ATP and DNA with ADAAD leading to ATP hydrolysis. (A) 1/v versus 1/DNA plot of the ATP hydrolysis data obtained with oligonucleotide 950. The line was described by the equation y = 0.0001x + 24‱053, where y = 1/v and x = 1/DNA. (B) ADAAD interacts with ATP to form E.ATP complex which further interacts with DNA to form [E.A.D] ternary complex. ADAAD can also interact with DNA to form [E.DNA] complex, which interacts with ATP to form [E.D.A] complex. The [E.A.D] complex is unproductive and cannot hydrolyze ATP, whereas the complex [E.D.A] is competent for ATP hydrolysis. However, it is possible that [E.A.D] complex can possibly undergo conformational change to [E.D.A]. Thus, [E.A.D] and [E.D.A] are not equivalent ternary complexes.

Table 3.

Calculation of vmax, KATP and KDNA using the proposed models

| Calculated from Model I | Calculated from Model II | Calculated from Model III | Calculated from Model IV | Experimentally determined from ATP hydrolysis data | Experimentally determined from fluorescence binding data | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vmax (nmol Pi released per min) | ||||||

| From slope | 4.7 | 0.31 × 10−3 | 4.2 | 3.8 | 2.4 | NA |

| From intercept | 4.2 | 4.2 | 7.9 | 4.2 | ||

| KATP (M) | ||||||

| −27.6 × 10−6 | 0.21 × 10−3 | 1.2 × 10−6 | 0.14 × 10−6 | − | 0.13 × 10−6 | |

DISCUSSION

In this article we have investigated the mechanism of the interaction of SWI2/SNF2 protein with its cognate DNA effector resulting in ATP hydrolysis. Using ATPase assays we show that ADAAD recognizes double-stranded:single-stranded transition regions specifically. Recently, Yusufzai and Kadonaga also showed that the protein recognizes such structures and suggested a reverse helicase function (34).

We show that for optimal ATPase activity, the double-stranded region of slDNA should be greater than 11 bp while the single-stranded loop should be between 8 and 12 bases long. Such stringency is consonant with the crystal structure data of Rad54, where a minimal handle of 12–15 bp has been shown to be necessary for the ATPase domain to grab DNA and remodel it (35). Similarly, structural data for Hel308 demonstrate an interaction with a DNA molecule containing a 13 bp duplex (36). Experimental data for Mot1p suggest the requirement of a 17 bp handle, while ISW2 requires a 20 bp handle for remodeling substrate (37,38).

It should be noted that our experimental methods do not allow us to distinguish whether ADAAD remains bound to DNA after ATP hydrolysis or whether it dissociates. The time scale of measurement is long relative to the probable microscopic changes in the enzyme. Hence, it is highly probable that each enzyme molecule catalyzes multiple rounds of ATP hydrolysis either through continued binding of DNA or through binding-dissociation-rebinding of DNA. Pre-steady state kinetic measurements will be required to differentiate between these possibilities (39,40).

Using fluorescence spectroscopy we demonstrate that both ATP and DNA can interact with ADAAD in the absence of the other. Moreover, slDNA, dsDNA and ssDNA, all have the ability to interact with ADAAD. A similar property is observed in Rep helicase where the individual subunits of Rep dimer can interact with both ssDNA and dsDNA. Furthermore, the Rep dimer can simultaneously bind to both ssDNA and dsDNA (41).

Saturation of ADAAD with ATP prior to addition of DNA allows DNA to bind with higher affinity to it. Similarly, saturation of the protein with DNA prior to addition of ATP allows ATP to bind 10-fold more tightly to the protein. The enhanced binding of ATP or DNA in the presence of the other ligand is similar to that reported in YxiN, a RNA helicase from B. subtilis (31) and SsoRad54cd protein (17).

From these observations, we propose a model where each molecule of ADAAD has one binding site for ATP and one for DNA. In the absence of ATP and DNA, ADAAD is in its inactive form (Figure 6B). The conversion of the inactive to active form could occur via two pathways. In the first pathway, ATP binds to the enzyme and induces a conformational change that allows slDNA to bind. Binding of slDNA to the protein induces a second subsequent conformation change. Alternatively, the slDNA binds to the inactive form first, followed by ATP binding and hydrolysis.

Using theoretical models, we suggest that the two pathways are not equivalent. This is also supported by fluorescence quenching studies where the conformation of the protein in the presence of both DNA and ATP is dictated by the DNA and not by ATP. Thus, the first pathway results in a conformation, which is not competent for ATP hydrolysis. It is only when DNA binds first to ADAAD followed by ATP that the active conformation is formed and ATP hydrolysis takes place. We further propose that each DNA-binding site has two subsites wherein the single-stranded region binds to one subsite and the double-stranded region binds to the other subsite. The enzyme converts to an active form only in the presence of the appropriate slDNA effector as it possesses both single-stranded and double-stranded regions to contact both subsites simultaneously. Neither ssDNA nor dsDNA can simultaneously bind both subsites and hence, cannot effect the conformational change required for ATP hydrolysis.

It is interesting that though ADAAD can bind to ATP in the absence of DNA, hydrolysis does not occur until DNA is bound. The Rad54 crystal structure provides a plausible reason for this. Here, the binding of DNA allows motif II (DEXX) to change from the β conformation to the active α conformation which permits ATP hydrolysis (35,42). When motif II is in the β conformation, ATP cannot make contacts with the DE residues of this motif, and therefore, no ATP hydrolysis ensues (35).

Mutational analysis with RNA helicases have also shown the importance of the motif VI (on subdomain IB) in RNA binding and ATP hydrolysis (14). Motif I and Motif Q (on subdomain IA) are required for ATP binding as well as hydrolysis (35,43). Furthermore, the crystal structure of SsoRad54 shows that these two helicase-like domains are too far apart to form the catalytic site for ATP hydrolysis (35). From these data, it is possible to envision a model for ADAAD, wherein motif VI, is not in the correct orientation to interact with ATP in absence of DNA. In the presence of slDNA, it is possible that motif VI is oriented so as to interact with and mediate ATP hydrolysis. A ssDNA lacking the double-stranded region is probably unable to induce motif VI to adopt the correct orientation for ATP hydrolysis.

SWI2/SNF2 proteins have a wide range of effector preferences for ATP hydrolysis and it is plausible that the effector preference arises from the ability of the effector to induce the correct conformation in its cognate protein, permitting ATP hydrolysis. With this model, we provide a theoretical framework for ATP hydrolysis by SWI2/SNF2 proteins in the presence of specialized DNA effectors and therein provide a foundation for further experimental design and execution.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

DST Fast track grant SR/FT/L-42/2004 (to R.M.); Junior Research Fellowship from Department of Biotechnology (to M.N.); Rajiv Gandhi Fellowship (to P.D.); University of Virginia School of Medicine support (to J.H.). Funding for open access charge: XIth plan Capacity Buildup.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank Susan E. Hockensmith for her technical proficiency and experimental contribution.

REFERENCES

- 1.Matson SW, Bean DW, George JW. DNA helicases: enzymes with essential roles in all aspects of DNA metabolism. Bioessays. 1993;16:13–22. doi: 10.1002/bies.950160103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlson M, Laurent BC. The SNF/SWI family of global transcriptional activators. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1994;6:396–402. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen X, Mizuguchi G, Hamiche A, Wu C. A chromatin remodelling complex involved in transcription and DNA processing. Nature. 2000;406:541–544. doi: 10.1038/35020123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsukiyama T, Daniel C, Tamkun K, Wu C. ISWI, a member of the SWI2/SNF2 ATPase family encodes the 140kDa subunit of the nucleosome remodeling factor. Cell. 1995;83:1021–1026. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90217-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muthuswami R, Truman PA, Mesner LD, Hockensmith JW. A eukaryotic SWI2/SNF2 domain, an exquisite detector of double-stranded to single-stranded DNA transition elements [published erratum appears in J Biol Chem 2000;275(25):19433–4] J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:7648–7655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coleman MA, Eisen J, Mohrenweiser HW. Cloning and characterization of HARP: a prokaryotic HepA related SNF2 helicase protein from human and mouse. Genomics. 2000;65:274–282. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corona DF, Tamkun JW. Multiple roles for ISWI in transcription, chromosome organization and DNA replication. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1677:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2003.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohrmann L, Verrijzer CP. Composition and functional specificity of SWI2/SNF2 class chromatin remodeling complexes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1681:59–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flaus A, Martin DM, Barton GJ, Owen-Hughes T. Identification of multiple distinct Snf2 subfamilies with conserved structural motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:2887–2905. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hockensmith JW, Wahl AF, Kowalski S, Bambara RA. Purification of a calf thymus DNA-dependent adenosinetriphosphatase that prefers a primer-template junction effector. Biochemistry. 1986;25:7812–7821. doi: 10.1021/bi00372a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martens JA, Winston F. Recent advances in understanding chromatin remodeling by Swi/Snf complexes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2003;13:136–142. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(03)00022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langst G, Becker PB. Nucleosome mobilization and positioning by ISWI-containing chromatin-remodeling factors. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:2561–2568. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.14.2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gangaraju VK, Bartholomew B. Mechanisms of ATP dependent chromatin remodeling. Mutat. Res. 2007;618:3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pause A, Methot N, Sonenberg N. The HRIGRXXR region of the DEAD box RNA helicase eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4A is required for RNA binding and ATP hydrolysis. Mol. Cell Biol. 1993;13:6789–6798. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.11.6789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pause A, Sonenberg N. Mutational analysis of a DEAD box RNA helicase: the mammalian translation initiation factor eIF-4A. EMBO J. 1992;11:2643–2654. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05330.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rocak S, Emery B, Tanner NK, Linder P. Characterization of the ATPase and unwinding activities of the yeast DEAD-box protein Has1p and the analysis of the roles of the conserved motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:999–1009. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis R, Durr H, Hopfner KP, Michaelis J. Conformational changes of a Swi2/Snf2 ATPase during its mechano-chemical cycle. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:1881–1890. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quinn J, Fyrberg AM, Ganster RW, Schmidt MC, Peterson CL. DNA-binding properties of the yeast SWI/SNF complex. Nature. 1996;379:844–847. doi: 10.1038/379844a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsukiyama T, Wu C. Purification and properties of an ATP-dependent nucleosomal remodeling factor. Cell. 1995;83:1011–1020. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90216-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petukhova G, Stratton S, Sung P. Catalysis of homologus DNA pairing by yeast Rad51 and Rad54 proteins. Nature. 1998;393:91–94. doi: 10.1038/30037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Auble DT, Hahn S. An ATP-dependent inhibitor of TBP binding to DNA. Genes Dev. 1993;7:844–856. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.5.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bradford M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuker M. Computer prediction of RNA structure. Methods Enzymol. 1989;180:262–288. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(89)80106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zuker M. On finding all suboptimal foldings of an RNA molecule. Science. 1989;244:48–52. doi: 10.1126/science.2468181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zuker M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Breslauer KJ, Frank R, Blocker H, Marky LA. Predicting DNA duplex stability from the base sequence. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83:3746–3750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.3746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bloomfield VA, Crothers DM, Tinoco I., Jr . Physical Chemistry of Nucleic Acids. New York: Harper and Row; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muthuswami R, Mesner LD, Wang D, Hill DA, Imbalzano AN, Hockensmith JW. Phosphoaminoglycosides inhibit SWI2/SNF2 family DNA-dependent molecular motor domains. Biochemistry. 2000;39:4358–4365. doi: 10.1021/bi992503r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bjornson KP, Moore KJM, Lohman TM. Kinetic mechanism of DNA binding and DNA-induced dimerization of the Escherichia coli rep helicase. Biochemistry. 1996;35:2268–2282. doi: 10.1021/bi9522763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bjornson KP, Wong I, Lohman TM. ATP hydrolysis stimulates binding and release of single stranded DNA from alternating subunits of the dimeric E. coli rep helicase: implications for ATP-driven helicase translocation. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;263:411–422. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Theissen B, Karow AR, Kohler J, Gubaev A, Klostermeier D. Cooperative binding of ATP and RNA induces a closed conformation in a DEAD box RNA helicase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:548–553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705488105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel SS, Wong I, Johnson KA. Pre-steady state kinetic analysis of processive DNA replication including complete characterization of an exonuclease-deficient mutant. Biochemistry. 1991;30:511–525. doi: 10.1021/bi00216a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lackowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. New York: Plenum Publishers; 1999. p. 10013. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yusufzai T, Kadonaga JT. HARP is an ATP-driven annealing helicase. Science. 2008;322:748–750. doi: 10.1126/science.1161233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Durr H, Korner C, Muller M, Hickmann V, Hopfner KP. X-ray structures of the Sulfolobus solfataricus SWI2/SNF2 ATPase core and its complex with DNA. Cell. 2005;121:363–373. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buttner K, Nehring S, Hopfner KP. Structural basis for DNA duplex separation by a superfamily-2 helicase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:647–652. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Darst RP, Wang D, Auble DT. MOT1-catalyzed TBP-DNA disruption: uncoupling DNA conformational change and role of upstream DNA. EMBO J. 2001;20:2028–2040. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.8.2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zofall M, Persinger J, Bartholomew B. Functional role of extranucleosomal DNA and the entry site of the nucleosome in chromatin remodeling by ISW2. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;24:10047–10057. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.22.10047-10057.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lohman TM, Tomko EJ, Wu CG. Non-hexameric DNA helicases and translocases: mechanisms and regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:391–401. doi: 10.1038/nrm2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keller D, Bustamante C. The mechanochemistry of molecular motors. Biophys. J. 2000;78:541–556. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76615-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wong I, Lohman TM. Allosteric effects of nucleotide cofactors on Escherichia coli Rep helicase-DNA binding. Science. 1992;256:350–355. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5055.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Subramanya HS, Bird LE, Brannigan JA, Wigley DB. Crystal structure of a DExx box DNA helicase. Nature. 1996;384:379–383. doi: 10.1038/384379a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanner NK, Cordin O, Banroques J, Doere M, Linder P. The Q motif: a newly identified motif in DEAD box helicases may regulate ATP binding and hydrolysis. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:127–138. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.