Abstract

Problem statement

Health care delivery in Germany is highly fragmented, resulting in poor vertical and horizontal integration and a system that is focused on curing acute illness or single diseases instead of managing patients with more complex or chronic conditions, or managing the health of determined populations. While it is now widely accepted that a strong primary care system can help improve coordination and responsiveness in health care, primary care has so far not played this role in the German system. Primary care physicians traditionally do not have a gatekeeper function; patients can freely choose and directly access both primary and secondary care providers, making coordination and cooperation within and across sectors difficult.

Description of policy development

Since 2000, driven by the political leadership and initiative of the Federal Ministry of Health, the German Bundestag has passed several laws enabling new forms of care aimed to improve care coordination and to strengthen primary care as a key function in the German health care system. These include on the contractual side integrated care contracts, and on the delivery side disease management programmes, medical care centres, gatekeeping and ‘community medicine nurses’.

Conclusion and discussion

Recent policy reforms improved framework conditions for new forms of care. There is a clear commitment by the government and the introduction of selective contracting and financial incentives for stronger cooperation constitute major drivers for change. First evaluations, especially of disease management programmes, indicate that the new forms of care improve coordination and outcomes. Yet the process of strengthening primary care as a lever for better care coordination has only just begun. Future reforms need to address other structural barriers for change such as fragmented funding streams, inadequate payment systems, the lack of standardized IT systems and trans-sectoral education and training of providers.

Keywords: primary care, care coordination, continuity of care, disease management programmes, gatekeeping, medical care centres

Introduction

Health care delivery in Germany is highly fragmented, resulting in poor vertical and horizontal integration and a system that is focused on curing single diseases instead of managing patient populations. While it is now widely accepted that a strong primary care system can help to improve coordination and responsiveness in health care, with the endorsement of the government, primary care in the German system has only recently begun to move in that direction. Traditionally there has been no gatekeeper function; patients can freely choose and directly access both primary and secondary care providers, making coordination and cooperation within and across sectors difficult.

Since 2000, in an unusually long phase of programmatic and personal continuity in health care policy in Germany, the Federal Ministry of Health prepared several decisive legislative moves to improve care continuity with primary care as a hub. It promoted more integrative forms of care via disease management programmes and medical care centres, it induced competition via selective contracting among providers and payers, it fostered gatekeeping and introduced patient registries for the chronically ill, and it began to align financial incentives for physicians, insurers, and patients.

In this article, we will first give a brief working definition of integrated primary care and then outline the current status of the German health care system from an integrated primary care perspective. We will identify existing barriers to integrated primary care in Germany. Against this background, we will then present different reforms and policies implemented in Germany since 2000. All these reforms have placed primary care in the centre, strengthening its role as the patient’s navigator through the health care system. As far as evaluation results are available—implementation of most of the reforms is ongoing and systematic evaluation is not always a requirement—we will discuss the impact of the new forms of care on coordination and health outcomes. In the concluding section we will assess future implications for policy makers: have these reforms pulled the right levers for promoting stronger coordination and strengthening the primary care system’s role as navigator through the health system? What other barriers must be addressed by future reforms?

Primary care: at the centre of a fragmented system

A brief working definition of integrated primary care

A strong primary care system can help improve continuity and responsiveness in health care especially for specific population groups such as frail elderly or people with complex conditions, but also for the population in general [1, p. 15]. According to Starfield, primary care has four main functions. A primary care system should enable first-contact access for each new need; provide long-term person-focused care; ensure comprehensive care for most health needs, and it should coordinate care, both horizontally and vertically, when services from other providers are needed [2]. This is because person-focused, comprehensive care can only be provided when primary care is supported by other levels of care, including community services and hospital care. For our purposes, we define integrated primary care as a system that fulfils all these four functions and especially the coordinative function.

In the following section, we will assess how well the current German system is prepared to fulfil this coordinative function and thus to provide integrated primary care. How well does cooperation between different professions work—within the primary care sector, between the primary care sector and other sectors of health care, and between health and social care? What role does primary care play in the coordination process, and what are the barriers to a more integrated role of primary care?

Primary care in Germany: status quo

Primary care in Germany includes all ambulatory care services provided by office-based, mostly single-handed, private for-profit general practitioners/family doctors, general internists or paediatricians. Primary care providers make up 49% of office-based physicians in Germany. The other half are specialists—almost all specialities are offered in Germany by office-based secondary care providers [3].

Traditionally primary care physicians do not have a formal gatekeeper function. Individuals can freely choose their primary care provider, and patients have free choice of specialists, psychotherapists (since 1998), dentists, pharmacists and emergency care [4, p. 5]. Since office-based primary and secondary care physicians work in solo practice, health care is often not coordinated. Doctor hopping is a well-known phenomenon and consequence from the way the system is set up [5].

Solo doctors and their support

Sixty-eight percent of primary care physicians in Germany work in solo practice; 31% work in small group practices with 2−4 full-time equivalent doctors [6]—sharing office space but not patients or patients’ health care files. Medical care in the primary care setting is exclusively provided by physicians—other health care workers with a ‘midlevel’ of training (like nurse practitioners or physician assistants in the US, Canada, or the Netherlands) does not exist in German primary care [7]. Traditionally doctors have worked with medical assistants (‘Arzthelferin’) who complete a three-year vocational training, and whose role in physicians’ practices combines administrative and some clinical tasks. In a medical assistant’s daily work administrative tasks prevail, their clinical responsibilities are limited to minor tasks like taking blood pressure, giving injections or taking and analysing blood samples. There have been efforts to develop the medical assistants’ profession into something closer to a nurse practitioner (see below in the section on ‘Community Medicine Nurses’), but most doctors in Germany (56%) oppose the idea of expanding the role of non-physicians in delivering care to patients [6].

Health information technology is not very advanced in primary care practice and still mostly used for administrative purposes, not for clinical decision support or patient management. The most common feature is electronic prescribing of medication (used routinely by 59% of primary care physicians in Germany) [6]. In the use of electronic medical records (used by 42%), electronically ordering tests or accessing test results or hospital records, Germany lags behind other countries (see Table 1 Percentage of primary care physicians using electronic support).

Table 1.

Percentage of primary care physicians using electronic support

| Percent reporting routine use of: | AUS | CAN | GER | NL | NZ | UK | US |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic patient medical records | 79 | 23 | 42 | 98 | 92 | 89 | 28 |

| Electronic prescribing of medication | 81 | 11 | 59 | 85 | 78 | 55 | 20 |

| Electronic access to patients’ test results | 76 | 27 | 34 | 78 | 90 | 84 | 48 |

| Electronic access to patients’ hospital records | 12 | 15 | 7 | 11 | 44 | 19 | 40 |

Source: 2006 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey of Primary Care Physicians.

Cooperation between primary care and other sectors

Care coordination between the ambulatory sector and the hospital is a challenge for the German health care system. Hospitals have legally been restricted to focus on inpatient care and to provide outpatient emergency care; only university hospitals have formal outpatient facilities [4, p. 16]. Health care reforms in 2004 and 2007 have granted hospitals additional competencies to provide outpatient services to patients. Today, the main forms of ambulatory care provided by hospitals are day surgery, highly specialised outpatient care, and outpatient care as part of disease management programmes and integrated care contracts.

If inpatient treatment is needed, office-based physicians refer their patients (but do not follow them during their hospital stay) and usually—but not systematically—receive them back after discharge. Post-surgical care is usually also done by office-based physicians. Not surprisingly is diverging pharmaceutical treatment, prior, during and post hospitalization, hard to explain to patients, and it is a typical bone of contention between hospitals and primary care providers.

More than 50% of primary care physicians report that it takes more than 14 days for them to receive a full report from a hospital once their patient has been discharged [6]; for 15% it takes more than a month. Electronic access to their patients’ hospital records is available only for 14% of primary care physicians [6]. Seventy percent of the respondents stated that better integration of information systems between office-based physicians and hospitals would be an effective way to improve quality of care [6].

Poor linkages between the health care system and services in the community like long-term care, social services, self-help or patient groups, family and lay carers, are also notorious in Germany, and constitute another obstacle to more holistic care and better care coordination. Social care in Germany is provided by a myriad of mainly private organizations that complement family and lay support for people with special needs and various levels of dependency, i.e. the elderly, children with special needs, mentally ill and the physically or mentally handicapped [4, p. 16]. One major reason for poor coordination between health and social care is financing: services in these sectors are financed by different funding streams and insurance regimes.

Thus, mainstream health care in Germany is still far from being an integrated system with primary care at its centre. Current access rules, i.e. free choice of providers, do not provide incentives for coordination through a primary care provider. Moreover, the financing and the organisational set-up of the system are two additional barriers to stronger cooperation. Also, with the spatial separation of care providers and poor use of health information technology, providers’ administrative costs for coordinating care are still rather high and are not appropriately reimbursed in the doctors’ fee schedule. Further, the development of new professions such as academically trained nurses who could complement GP services has only just begun [8, 9].

Aware of these problems, the German government has introduced a number of reforms during the last nine years, which address the various barriers identified above.

Health care reform in Germany: steps toward better care coordination

Since the year 2000, the German government has introduced a variety of managed care tools and structures, through three subsequent reforms [10–12]. The most recent reform act of 2007 [12] has broadened opportunities of care coordination between providers and across sectors.

Gatekeeping, disease management programmes, integrated care contracts, medical care centres and community medicine nurses all can lead to a stronger role for primary care. Receiving previously unknown political support, primary care providers can now fulfil a more integrating function and act as patient navigators through the health care system. Other objectives pursued in the series of reforms mentioned above are quality improvement and cost control, as care coordination is expected to contribute to a more efficient use of health care.

To make new forms of care possible, the government changed the rules of contracting between health insurance funds and providers. Prior to 2000, contracting between ambulatory care practitioners and health insurance funds had been compulsory and indirect—for physicians contracting with statutory health insurance funds, membership in a regional association of statutory health insurance physicians has been (and still is) mandatory. These regional associations negotiate collective contracts for ambulatory care with the health insurance funds that operate in their region. They receive a total budget from the health insurance funds based on historical data and distribute it among their physician members on a fee-for-service basis. The Reform Act of Statutory Health Insurance 2000 [10] for the first time broke with the strict system of collectively negotiated contracts and budgets, introducing the possibility for physicians to selectively sign contracts with health insurance funds for integrated care schemes, gatekeeper models and disease management programmes.

Integrated care contracts

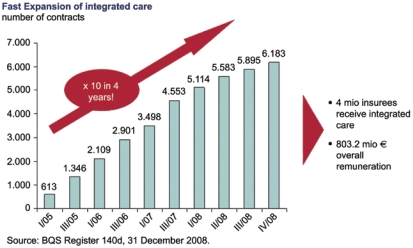

The 2000 reform thus established the legal basis for health insurance funds and providers to enter selective integrated care contracts, besides the above-mentioned unitary but mandatory collective contractual system. Under integrated care contracts, care is provided in provider networks that can be managed by independent management organizations. But uptake of integrated care contracts was initially very slow. A key measure toward accelerating care coordination was the offer of financial incentives for providers, introduced by law but for a limited period of time: from 2004 to 2008, one percent of the total Statutory Health Insurance budget available for ambulatory and hospital care has been earmarked to initially fund integrated care contracts. In total, the start-up financing scheduled until the end of 2008 amounted to approximately e 800 million [13]. From just over 600 contracts in early 2005, by December 2008 their number had risen to more than 6000 with about four million patients being treated under this contractual form of integrated care (see also Figure 1 Fast expansion of integrated care) [13].

Figure 1.

Fast expansion of integrated care.

The Statutory Health Insurance Competition Strengthening Act of 2007 [12] established further integrated care opportunities. Since then, long-term care providers can be included in contracts, and non-medical professionals can become the main contractual partner to health insurance funds, a position formerly restricted to physicians. Also since 2007, integrated care contracts now are to focus on population-oriented integrated care, a term not defined by the lawmaker to allow for creativity in designing integrated care models. It is usually understood as proactive, patient-centred health care for a defined population with providers taking responsibility for the coordination of care and for improving or maintaining the health status of the insured population, thereby putting a focus on health promotion or prevention [14]. So far, however, disease- or procedure-oriented contracts continue to constitute the bulk of the integrated care contracts signed [15]. Only a few companies are developing ambitious models of population-oriented integrated care in Germany [16, p. 129–223].

Particularly the move towards population-oriented integrated care can imply a strengthening of primary care as the coordinating agent in a patient’s care process. Population-oriented care implies a more comprehensive concept of health care, in which a multidisciplinary group of providers is not only responsible for curing illness but also for maintaining or improving the health status of the population. This comes very close to Starfield’s model of integrated primary care as an ongoing, person-focused, comprehensive and coordinating system of care [2]. Existing models of population-oriented integrated care in Germany use either a primary care physician or team as the coordinating agent for participating patients [16].

Gatekeeping models

Gatekeeping based on primary care physicians was introduced in 2000. Gatekeeping in primary care also exists in other countries with SHI systems like the Netherlands and has recently been implemented in France in 2004 [17]. In Germany, patients are free to choose a family physician who then serves as gatekeeper and guide through the health care system. Once a patient has subscribed to a gatekeeping scheme, specialists can only be seen upon referral, although exceptions apply for gynaecologists, paediatricians and ophthalmologists.

Since 2007 legislation requires health insurance funds to offer gatekeeper contracts. For patients, enrolment in gatekeeping arrangements is voluntary and can be rewarded through financial incentives by their health insurance fund. About six million patients had signed up for the gatekeeping scheme by the end of 2007 [18]. Family physicians willing to enter a gatekeeper contract with a health insurance fund have to fulfil certain criteria: participate in quality circles, follow evidence-based treatment guidelines, run a quality management programme in their practice, and attend trainings in areas like patient-oriented communication, basic treatment and diagnostics of mental disorders, palliative or geriatric care [19].

Gatekeeping is a very forthright provision of the lawmaker to strengthen primary care, installing the primary care physician as the coordinating agent in patient health care and restricting the patient’s free choice of specialists. Through better care coordination and the above-mentioned criteria for participating physicians, gatekeeping contracts are to enhance the quality of care and to reduce costs by preventing unnecessary specialist visits.

There is no mandatory evaluation of gatekeeper contract outcomes. However, a survey among health insurance members conducted by the Bertelsmann Stiftung between 2004 and 2007 revealed that in their current set-up, gatekeeping arrangements do not achieve their aims of controlling the number of patient visits to specialists or of improving health outcomes. Patients enrolled in gatekeeper contracts do not report better health outcomes than patients who are not enrolled, and the number of visits to specialists does not seem to go down [20]. In future contracts, more incentives for physicians to improve the quality of care seem to be necessary if gatekeeping models are to actually reach their goals.

Disease management programmes

Disease management programmes (DMPs) were introduced in Germany in 2002, in continuation of an earlier reform. In 1996, a risk equalization scheme based on average spending by age and sex was introduced between statutory health insurance funds. However, the costs of providing care for chronically ill patients had not been taken into account adequately, which led to health insurance funds particularly targeting young, healthy insurees. In 2004, a separate high-risk structure compensation scheme for patients enrolled in disease management programmes was added. Under the new scheme, DMP participants no longer generate a deficit: health insurance funds receive an additional lump sum from the risk equalization scheme for each person enrolled.

There are six requirements for DMP accreditation by the German Federal Insurance Authority [21]:

Treatment according to evidence-based guidelines with respect to the relevant sectors of care;

Quality assurance measures;

Required procedure for enrolment of insured, including duration of participation;

Training and information for care providers and patients;

Electronic documentation of diagnostic findings, applied therapies and outcomes;

Evaluation of clinical outcomes and costs.

Disease management programmes currently exist for six major chronic conditions: diabetes type 1, diabetes type 2, coronary heart disease, breast cancer, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [21]. In June 2008, more than 5.2 million patients were enrolled, the largest share (2.7 million) of which participate in Diabetes type 2 DMPs [Personal conversation with representative of the German Federal Insurance Authority (Bundesversicherungsamt) on February 6, 2009].

For patients and physicians DMP participation is voluntary. Incentives exist for both: patients are exempt from out-patient fees and co-payments; physicians receive a lump sum payment for coordination and documentation activities. Usually, primary care physicians take on the role of coordinating care for DMP patients over time, referring them to specialists when necessary and documenting the care process [22].

A growing number of DMP evaluations show them to meet expectations and be successful [23–28]. All studies indicate a better care process as well as improved clinical outcomes. Participants experience less complications and emergency hospital admissions; instead, the number of early-stage hospitalization is higher. Compared to non-enrolled control group patients, diabetes type 2 patients enrolled in DMPs self-report higher quality of life and a better physical and mental health status; their abilities for self-management of their condition are strengthened. Similarly, a representative case-control study published in mid-2008 reported less relapses, less pain, better results for blood pressure and cholesterol for patients participating in a coronary heart disease DMP [29]. Among physicians, acceptance is also rising, although initially documentation requirements were perceived as an extra burden.

Most of the time in the implementation of disease management programmes, primary care takes a central coordinating position. Among diabetes type 2 patients, the largest patient group enrolled in DMPs, 90% have a primary care physician as their partner in the programme [22].

When developing its disease management programmes, Germany had looked at managed care models in the USA. Meanwhile, with their clearly defined requirements for documentation, evaluation and treatment guidelines and their careful mix of incentives for payers, providers, and patients, German DMPs have themselves become a model for other countries. One of the next challenges to solve is how to adapt DMPs to multimorbidity. Most chronically ill patients suffer from concurrent chronic conditions [30]—a fact slowly taken into account in disease management. One of the first DMPs to address this problem is the programme on coronary heart disease to which recently a module on chronic heart failure has been added [31].

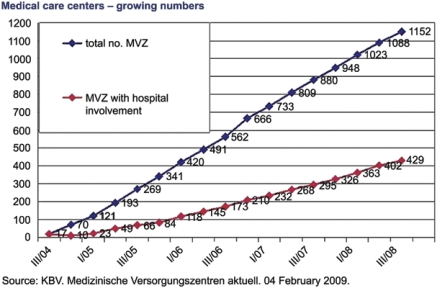

Medical care centres

Medical care centres are another innovation introduced in 2004. While integrated care contracts (see the previous section on integrated care contracts) allow for contracts between providers of inpatient and outpatient care, medical care centres are legally required to only provide ambulatory care. Medical care centres, also referred to as polyclinics, build upon a state-run primary care delivery model that was well established in former East Germany. By law, they are defined as interprofessional institutions, headed by physicians, with other registered physicians working as employees [11]. Medical care centres usually offer a primary care delivery system that brings together general practitioners and specialists under one roof. The average centre still only employs four physicians—just about the size of a small group practice in other countries [6]. Today ownership and management arrangements may vary—medical care centres can be run by hospitals or medical groups; legislation also permits the integration of pharmacies and non-medical health care services (e.g. physiotherapy, ergotherapy).

Medical care centres offer physicians the possibility to work as salaried employees in ambulatory care, an option that did not exist prior to 2004. It is a particularly attractive option to the rising number of women physicians looking for a better work-life balance, or to doctors who prefer team work over single-handed practice. Medical care centres furthermore provide the opportunity to practice in ambulatory care without taking the financial risk of a solo practice, enabling physicians to concentrate on clinical work without having to deal with practice administration or documentation requirements, and allow for flexible work hours [5, 33]. For patients, medical care centres are supposed to improve the quality of care through fewer visits (the larger ones offering one-stop-shop services), faster diagnosis using electronic medical records, standardized processes, coordinated care according to treatment guidelines and better access to specialists. However, since medical care centres are not systematically evaluated in Germany, very little data exists to affirm these assumptions.

A patient survey published in 2007 showed that patients treated in medical care centres gave better ratings for quality of care, accessibility and service, infrastructure and organisational structures than patients treated in solo practices. Ninety-five percent of patients stated that they would return to the medical care centre for receiving care and also 95% stated that they would recommend the centre to others [5].

Some concerns regarding the introduction of medical care centres were stated by an English study discussing the introduction of ‘polyclinics’ in the UK [34]:

Bringing professions together under one roof does not necessarily lead to integrated care—infrastructure and processes have to be in place to assist integration. However, [5] about 50% of German medical care centres still have no shared electronic patient record in place.

Integration of ambulatory care providers within a medical care centre does not yet imply a good coordination of care between the centre and the hospitals.

Lack of personal continuity of care can be a problem if a patient cannot choose a personal primary care physician in a medical care centre.

The existence of primary and specialist care within the same institution might encourage overuse of specialty care, thereby increasing costs.

Whether medical care centres in less populated regions of Germany lead to access barriers— because of a concentration of physicians in one place—or to improved access—flexible working conditions may as well attract further physicians [32]—is still being disputed.

With medical care centres the lawmaker gave physicians in ambulatory care and hospitals the option of a new form of cooperation that allows for a shared use of resources. Although the law does not include mandatory participation of primary care providers, many medical care centres offer primary care services. Since 2004, more than 1000 medical care centres have been set up (see Figure 2 Medical care centres—growing numbers), with ca. 4800 staff physicians—compared to the total of 130,000 doctors who work in ambulatory care in Germany. Among them are about 793 general practitioners and 488 internists—making primary care physicians the largest specialty group working in this type of health care delivery system [32, p.3, 7].

Figure 2.

Medical care centres—growing numbers.

‘Community Medicine Nurses’

As depicted in the previous section on a brief working definition of integrated primary care, medical care in the German primary care setting is exclusively provided by physicians. Under the name of AGNES the Institute of Community Medicine at the University of Greifswald started several pilots in 2005 to test if nurse practitioners, so-called ‘Community Medicine Nurses’, can support primary care physicians in sparsely populated areas in prevention, nursing and assistance during routine home visits. They are expected to ensure regular access to basic health care services for elderly patients.

‘Community Medicine Nurses’ act only by order of a family physician. They visit patients at home, run basic diagnostic tests, apply new bandages or take blood samples and they serve as contact persons for mostly elderly patients, supervise their medication, consider preventive action, and offer advice and support. They are provided with a tablet PC that enables them to transfer medical data from the patient’s home to the doctor’s practice immediately and to reach the physician via video communication at any time.

Pilots in four states were evaluated for the first time in July 2008 by surveying participating physicians and patients. Ninety-eight percent of the patients perceived the nurse practitioner as a competent partner in health care, 94% supported the delegation of regular home visits to nurse practitioners. A large majority of primary care physicians stated that the nurse practitioners provided valuable support (38 of 42 physicians) and had a positive effect on patient compliance (37 of 42 physicians). For 92% of patients, physicians perceived the delegation of task as having no negative effect on the quality of care [35].

To qualify physician assistants or traditional nurses for the work profile of a ‘Community Medicine Nurse’ the University of Greifswald developed an advanced training programme. The profession of ‘Community Medicine Nurses’ implies the redistribution of some of the tasks that today are the sole responsibility of physicians. If implemented on a larger scale, this would have a rather fundamental impact on German health care structures. However, the open question of how to include the new profession into financing structures in ambulatory care is still a major obstacle to a large-scale implementation.

The main goal of the AGNES project is not to improve care coordination but to establish a new structure of support for primary care physicians in rural areas. Still, the introduction of nurse practitioners into the German health care system and the current discussion about the delegation of clinical tasks to non-physician staff might over time turn out to be a step towards integrated primary care in Germany. To deliver continuing, person-focused, comprehensive care and fulfil a coordinating role, a multidisciplinary primary care team is better fitted than a physician in solo practice with little support [36, 37]. The discussion around AGNES nurse practitioners might open the door for new forms of cooperation within primary care practices.

Conclusion: towards integrated primary care in Germany—drivers and future challenges

The reforms described in the previous section can be considered as the first careful steps towards a better integrated care system in which primary care takes on a stronger role as coordinator and navigator. Reforms since 2000 have activated a number of drivers. The government, assuming a leading role throughout a year-long reform process, negotiated with all stakeholders in the system, introduced legal changes, making possible selective contracting between health insurance funds and providers. Health insurance funds are obliged by law to offer gatekeeping programmes to their insured, thus strengthening the role of general practitioners in the system. The role of primary care is also strengthened through DMPs, the majority of which is coordinated by general practitioners. To increase uptake of the new schemes, financial incentives for providers and patients were introduced.

For patients, the rather complex developments of several new forms of care in Germany are hard to comprehend as a general trend towards more coordination and more competition in health care. However, patients participating in the new primary care arrangements most often approve of the more patient-oriented care delivery. The increasing number of integrated care contracts, DMPs, gatekeeping programmes and medical care centres as well as the increasing number of enrolled patients indicate that these new forms of care slowly gain acceptance in the German system.

Nevertheless, the reforms have also met with considerable resistance and implementation of primary care-focused care has not yet been achieved on a large scale. One reason is that it is difficult to change long-established traditions, expectations of providers and patients, practice habits and structures. German physicians feel threatened in many ways by the structural changes that policy makers have initiated. Their complaints are about increased reporting and documentation requirements associated with DMPs. Tools for transparency and benchmarking are by some physicians seen as an attack on their independence and professionalism, as are new forms of care and care management, such as larger medical care centres, or the staff physician status in ambulatory care. However, younger physicians and female doctors are more likely to consider the advantages in new workplace and contractual arrangements in more professionally managed settings, and of (peer) evaluation and feedback.

Future reforms—and a constant dialogue between policy makers and health professionals—will have to address the following challenges:

Primary care as the foundation of the health care system and as a public good needs continuing regulatory endorsement and political protection;

Shared leadership: interdisciplinary and horizontal cooperation between providers from different specialties and sectors needs support and SHI-endorsed incentives, particularly in regional negotiations about budgetary redistribution with SHI physician associations where primary care providers are often outweighed by specialists;

Population orientation: DMPs and most integrated care contracts still are predominantly single disease-oriented and lack a broader population-centred approach that embraces both prevention and multimorbidity.

In short, in Germany the debate about granting a stronger role to primary care as a lever for better care coordination and integration has only just begun. Continuing political support, a rare window of opportunity in the form of prolonged personal continuity at the head of the Federal Ministry of Health, and a visionary leadership willing to learn from primary care experiences elsewhere have been instrumental throughout the reform years. Or as Marc Danzon has put it more broadly when commenting on similar developments across Europe: “These types of fundamental organizational adjustments are, by their very nature, long-term endeavours. Progress must be counted in years and requires focused and persistent efforts from key actors” [38, p. XVII].

Contributor Information

Sophia Schlette, Bertelsmann Stiftung, Carl-Bertelsmann-Str. 256, 33311 Gütersloh, Germany.

Melanie Lisac, International Network Health Policy and Reform, Bertelsmann Stiftung, Carl-Bertelsmann-Str. 256, 33311 Gütersloh, Germany.

Kerstin Blum, International Network Health Policy and Reform, Bertelsmann Stiftung, Carl-Bertelsmann-Str. 256, 33311 Gütersloh, Germany.

Reviewers

Mark Harris, Prof., Executive Director Centre for Primary Health Care and Equity, Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

Geoff Meads, Hon. Professor of International Health Studies, Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, UK

Petra Riemer-Hommel, Prof., PhD, HTW des Saarlandes, School of Social Sciences, Saarbrücken, Germany

References

- 1.Boerma WGW. Coordination and integration in European primary care. In: Saltman R, Rico A, Boerma WGW, editors. Primary care in the driver’s seat? Organizational reform in European primary care. Berkshire: Open University Press; 2006. pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. The Milbank Quarterly. 2005;83(3):457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV) Statistische Informationen aus dem Bundesarztregister. Bundesgebiet insgesamt. [Statistical information from the federal registry of physicians]. Berlin: KBV; 2007. [cited 2008 Oct 5]. Available from: http://www.kbv.de/themen/125.html. [in German] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Busse R, Riesberg A. Health care systems in transition: summary Germany. Copenhagen: WHO o.b.o. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulte H, Schulz C. Verbesserung der ambulanten Patientenversorgung versus Selektion und Exklusion von Patientengruppen. [Medical Care Centres. Improving ambulatory care vs. selection and exclusion of patient groups]. Baden Baden: Nomos; 2007. Medizinische Versorgungszentren. [in German] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris Interactive. 2006. International health policy survey of primary care physicians. Topline results. New York: The Commonwealth Fund; 2006. Available from: http://www.cmwf.org/Content/Surveys/2006/2006-International-Health-Policy-Survey-of-Primary-Care-Physicians.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosemann T, Joest K, Körner T, Schaefert R, Heiderhoff M, Szecsenyi J. How can the practice nurse be more involved in the care of the chronically ill? The perspectives of GPs, patients and practice nurses. BMC Family Practice. 2006 Mar 3;7:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-7-14. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2296/7/14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Appropriateness and efficiency. Report 2000–2001 Summary. Bonn: Advisory Council on the Assessment of Developments in the Health Care System; 2001. Sachverständigenrat zur Begutachtung der Entwicklung im Gesundheitswesen. Available from: http://www.svr-gesundheit.de. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Health care finance, user orientation and quality. Report 2003 Summary. Bonn: Advisory Council on the Assessment of Developments in the Health Care System; 2003. Sachverständigenrat zur Begutachtung der Entwicklung im Gesundheitswesen. Available from: http://www.svr-gesundheit.de. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gesetz zur Reform der Gesetzlichen Krankenversicherung ab dem Jahr 2000 (GKV-Gesundheitsreform 2000) 1999. Available from: http://bundesrecht.juris.de/gkvrefg_2000/. [in German] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Gesetz zur Modernisierung der Gesetzlichen Krankenversicherung (GKV-Modernisierungsgesetz—GMG) [Statutory Health Insurance Modernization Act 2004]. Bundesgesetzblatt. 2003 Nov 19;Part 1(55):2190–258. Available from: http://www.bgblportal.de/BGBL/bgbl1f/bgbl103s2190.pdf. [in German] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gesetz zur Stärkung des Wettbewerbs in der Gesetzlichen Krankenversicherung (GKV-Wettbewerbsstärkungsgesetz—GKV-WSG) [Statutory Health Insurance Competition Strengthening Act 2007]. Bundesgesetzblatt. 2007 Mar 30;Part 1(11):378–473. Available from: http://www.bgblportal.de/BGBL/bgbl1f/bgbl107s0378.pdf. [in German] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Registrierungsstelle zur Unterstützung der Umsetzung des § 140d SGB V. BQS Register 140d. [webpage on the internet]. c2008. Available from: www.bqs-register140d.de. [in German]

- 14.Halpern A, Boulter P. Population-based health care: definitions and applications. Boston: Tufts Managed Care Institute; 2000. Available from: http://www.thci.org/downloads/topic11_00.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blum K. Care coordination gaining momentum in Germany. Health Policy Monitor. 2007 Jul; (Survey 9/2007). Available from: http://www.hpm.org/survey/de/b9/1. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weatherly JN, Seiler R, Meyer-Lutterloh K, Schmid E, Lägel R, Amelung VE. Leuchtturmprojekte integrierter Versorgung und medizinischer Versorgungszentren. Innovative Modelle der Praxis. [Innovative models of integrated care and medical care centres]. Berlin: Medizinisch Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft; 2007. [in German] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dourgnon P. Preferred doctor reform. Health Policy Monitor. 2006 Oct; (Survey 8/2006). Available from: http://www.hpm.org/survey/fr/a8/2. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. [Federal Ministry of Health]. Caspers-Merck: good start for gatekeeper modelCaspers-Merck: Hausarztmodell läuft gut an. Press release, 28 December 2007. Available from: http://www.medinfo.de/index-r-1862-thema-Hausarztmodell.htm#news. [in German] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV) [webpage on the internet]. Available from: http://www.kbv.de. [in German]

- 20.Böcken J. Hausarztmodelle im Spannungsfeld zwischen ordnungspolitischem Anspruch und Versorgungsrealität. In: Böcken J, Braun B, Amhof R, editors. Gesundheitsmonitor 2008. [Health monitor 2008]. Gütersloh: Verlag Bertelsmann Stiftung; 2008. pp. 105–21. [in German] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bundesversicherungsamt (BVA) [Federal Insurance Authority]. Accreditation of DMPs by the BVAZulassung der Disease Management Programme (DMP) durch das Bundesversicherungsamt (BVA) [webpage on the internet]. c2008. Available from: http://www.bundesversicherungsamt.de/cln_100/nn_1046648/DE/DMP/dmp__node.html?__nnn=true [in German] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scheible D, Neises G, Schlegel T. Perspektiven der sektorenübergreifenden Diabetesversorgung. [Perspectives of diabetes care across sectors]. Deutsches Ärzteblatt. 2008;105:4. [in German] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joos S, Rosemann T, Heiderhoff M, Wensing M, Ludt S, Gensichen J, et al. ELSID diabetes study. Evaluation of a large scale implementation of disease management programmes for patients with type 2 diabetes. Rationale, design and conduct—a study protocol [ISRCTN08471887] BMC Public Health. 2005 Oct 4;5:99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-99. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1260025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szecsenyi J, Rosemann T, Joos S, Peters-Klimm F, Miksch A. German diabetes disease management programs are appropriate for restructuring care according to the Chronic Care Model. An evaluation with the patient assessment of Chronic Illness Care instrument. Diabetes Care. 2008 Feb 25;31:1150–4. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2104. Available from: http://care.diabetesjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/31/6/1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elkeles T, Heinze S, Eifel R. Health care by a DMP for Diabetes mellitus Type 2—Results of a survey of participating insurance costumers of a HI company in Germany. Journal of Public Health. 2007;15(6):473–80. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-970053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elkeles T, Kirschner W, Graf C, Kellermann-Mühlhoff P. Versorgungsunterschiede zwischen DMP und Nicht-DMP aus Sicht der Versicherten. Ergebnisse einer vergleichenden Versichertenbefragung von Typ 2-Diabetikern der BARMER. [Representative comparative survey of BEK insured diabetes patients]. Gesundheits- und Sozialpolitik. 2008;82(1):10–8. [in German] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graf C, Ullrich W, Marschall U. Nutzenbewertung der DMP Diabetes mellitus—Neue Erkenntnisse aus dem Vergleich von DMP-Teilnehmern und Nichtteilnehmern anhand von GKV-Routinedaten und einer Patientenbefragung. [Utility Analysis of Diabetes mellitus DMP]. Gesundheits- und Sozialpolitik. 2008;82(1):19–30. [in German] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luzio S, Piehlmeier W, Tovar C, Eberl S, Lätzsch G, Fallböhmer E, et al. Results of the pilot study of DIADEM—A comprehensive disease management programme for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice Volume. 2007 Jun;76(3):410–7. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.AOK Bundesverband. Ergebnisse der gesetzlichen Evaluation der AOK-Programme für Patienten mit Koronaren Herzkrankheiten (Auswertungen der Zwischenberichte) [Interim report on evaluation results for local health care funds’ DMPs for patients suffering from coronary heart disease]. Berlin: AOK Bundesverband; 2008. [in German] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wittchen HU, Pieper L, Glaesmer H, Eichler T, Klotsche J, Katze E, et al. Results of the DETECT study group. Technical University of Dresden. [webpage on the internet]. Available from: http://www.detect-studie.de. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss (G-BA) [Federal Joint Committee]. Federal Joint Committee adds a module on chronic heart failure to DMP for coronary heart diseasePatienten im DMP „Koronare Herzkrankheit“ können künftig umfassender und zielgerichteter behandelt werden. G-BA aktualisiert das DMP und ergänzt das Modul „Chronische Herzinsuffizienz“. Press release, 20 June 2008. Available from: http://www.g-ba.de/informationen/aktuell/pressemitteilungen/248/. [in German] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV) Medizinische Versorgungszentren aktuell. 2nd Quartal 2008. [Information on medical care centres, 2nd quarter 2008]. Berlin: KBV; 2008. [in German] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pelleter J, Sohn S, Schöffski O. Grundlagen, Chancen und Risiken einer neuen Versorgungsform. [Medical Care Centres. Basics, chances and risks of a new form of care]. Burgdorf: Herz; 2005. Medizinische Versorgungszentren. [in German] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Imison C, Naylor C, Maybin J. Under one roof. Will polyclinics deliver integrated care? London: Kings Fund; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berg N van den, Meinke C, Heymann R, Fiß T, Suckert E, Pöller C, et al. AGnES: Hausarztunterstützung durch qualifizierte Praxismitarbeiter—Evaluation der Modellprojekte: Qualität und Akzeptanz. [AGnES: Supporting General Practitioners With Qualified Medical Practice Personnel—Model Project Evaluation Regarding Quality and Acceptance]. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 2009;106(1–2):3–9. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2009.0003. [in German] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Effective Clinical Practice. 1998 Aug-Sep;1(1):2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bellagio Primary Care. Bellagio model of population-oriented primary care. [publication expected in autumn 2009]. Available from: http://www.bellagioprimarycare.org.

- 38.Danzon M. Foreword. In: Saltman R, Rico A, Boerma WGW, editors. Primary care in the driver’s seat? Organizational reform in European primary care. Berkshire: Open University Press; 2006. pp. XVII–XVIII. [Google Scholar]