Abstract

Mannose-binding lectin (MBL) is a pattern recognition receptor of the complement system and plays an important role in innate immunity. Whether or not MBL acts as an acute-phase response protein in infection has been an issue of extensive debate, because MBL responses have shown a high degree of heterogeneity. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the promoter (wild-type Y versus X) and exon 1 (A versus 0) of the MBL2 gene can lead to MBL deficiency. This study investigated the influence of SNPs in the promoter and exon 1 of the MBL2 gene on the acute-phase responsiveness of MBL in 143 patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Acute-phase reactivity was observed only in MBL-sufficient genotypes (YA/YA, XA/YA, XA/XA and YA/0). In patients with wild-type exon 1 genotype A/A, positive acute-phase responses were associated with the presence of the YA haplotype and negative responses with its absence. Genotypes YA/0 and XA/XA produced equal levels of MBL in convalescence. In the acute phase, however, patients with genotype XA/XA displayed negative acute-phase responses more often than those with genotype YA/0. Correlation of MBL and C-reactive protein levels in the acute phase of pneumonia also depended upon the MBL2 genotype. In conclusion, acute-phase responsiveness of MBL was highly dependent upon the MBL2 genotype. These data suggest that heterogeneity in protein responses in the acute phase of disease should always be viewed in the light of possible influences of genetic differences in both structural and regulatory parts of the gene.

Keywords: complement, human studies, immunogenetics, mannose-binding lectin, pneumonia

Introduction

Mannose-binding lectin (MBL) is a multimeric pattern recognition protein of innate immunity and activates the lectin pathway of complement. It binds to a variety of microorganisms, including respiratory pathogens such as influenza A virus [1], pneumococci, Haemophilus influenzae[2] and Legionella pneumophila[3]. MBL deficiency has been correlated with increased risk of infection, including repeated respiratory tract infections [4], as early opsonization is compromised.

The MBL levels in serum are influenced by single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in exon 1 and in the promoter region of the MBL2 gene. Coding SNPs in exon 1 (‘0’ alleles B, C and D versus wild-type A allele) lead to non-functional MBL monomers in homozygotes, impairing early complement activation. The X/Y promoter SNP at position −220 influences MBL serum levels in heterozygotes by controlling transcription of the functional A allele. Genotypes 0/0 and XA/0 display MBL levels < 0·2 µg/ml and are considered deficient [5,6]. Other promoter SNPs are found at positions −550 (H/L) and +4 (P/Q) [5].

It has been suggested that MBL acts as an acute-phase protein responding to inflammation, consistent with its role in early infection [7]. However, this has been debated extensively, as MBL responses have shown a high degree of heterogeneity. Conflicting results have been described in postoperative patients [8–10], patients with severe infections [11] and patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) [12]. Although some of these studies considered MBL2 exon 1 polymorphisms in the analysis, none of them reported the influence of the X/Y promoter SNP on MBL acute-phase responsiveness in individual patients. However, increasing MBL levels in the first 5 days of febrile neutropenia were reported to be associated with the HY haplotype in paediatric oncology patients [13]. Therefore, including the promoter SNP seems important when considering acute-phase responsiveness of MBL.

We determined MBL levels and MBL2 genotypes in patients with CAP and analysed whether acute-phase responsiveness was associated with the observed genotypes, including the X/Y promoter SNP.

Materials and methods

Patients and controls

All adult patients (> 18 years) presenting with CAP in our general 600-bed teaching hospital during the period from October 2004 to August 2006 were included in this prospective study, as described previously [14]. Patients with a history of recent hospitalization (< 30 days) or a congenital or acquired immunodeficiency (including the use of prednisone 20 mg/day for more than 3 days) were excluded.

Pneumonia was defined as a new infiltrate on chest X-ray and the presence of two of the following six clinical signs of pneumonia: cough, production of sputum, signs of consolidation on respiratory auscultation, temperature > 38°C or < 35°C, C-reactive protein (CRP) three times above the upper limit of normal (5 mg/dl) or a leucocyte reaction {leucocytosis [white blood count (WBC) > 10 g/l], leucopenia (WBC < 4 g/l) or more than 10% rods in the differential count}. The chest X-ray was interpreted at presentation in the emergency department by a resident. For this study, it was evaluated the next day by an experienced radiologist who was blinded to the clinical information.

Whole blood samples were taken at day 1 of admission for DNA extraction. Serum samples were drawn at the acute phase (day 1) and during convalescence (day 30 or later) and stored for further analysis. Data on clinical parameters on the day of admission were collected and used to calculate the pneumonia severity index (i.e. Fine-score), as described previously [14,15]. The Fine-score stratifies patients with CAP in categories with low (score < 91; 0·0%–2·8% risk), medium (91–130; 8·2–12·5%) and high (> 130; > 25%) risk of mortality [15]. The study was approved by the local Medical Ethics Committee and informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Genotyping of MBL2

Combined MBL X/Y promoter and exon 1 haplotypes of MBL2 were determined using a previously described denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) assay [16] with modifications in a nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) protocol [17]. For each sample, two PCR assays specific for the promoter X SNP (forward primer ATT TGT TCT CAC TGC CAC C; reverse primer GAG CTG AAT CTC TGT TTT GAG TT; annealing temperature 63°C; 25 cycles) or Y SNP (forward primer TTT GTT CTC ACT GCC ACG; same reverse primer and PCR conditions) were run. The two PCR products were diluted separately 1 : 100 in distilled water. MBL2 exon 1 was amplified from these two dilutions with an extra GC-clamp attached to one primer to meet DGGE requirements [forward primer with 41-base pair clamp: CCG CCC GCC GCG CCC CGC GCC CGG CCC GCC GCC CCC GCC CCT CCA TCA CTC CCT CTC CTT CTC; reverse primer: GAG ACA GAA CAG CCC AAC ACG].

The amplified DNA was run overnight on a 6% polyacrylamide gel containing a denaturing gradient increasing linearly from 35% to 55% formamide and urea. All MBL2 exon 1 genotypes could be distinguished by their different patterns of migration. The corresponding MBL2 X/Y promoter haplotype could be inferred from the presence or absence of a product in the two nested PCR assays. Genotypes 0/0 and XA/0 were considered ‘MBL-deficient’, and genotypes YA/0, XA/XA, XA/YA and YA/YA were considered ‘MBL-sufficient’[5,6].

The MBL enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Serum levels of the multimeric MBL protein were determined using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Sanquin, Amsterdam, the Netherlands). Briefly, MBL bound to coated mannan was quantified with the use of an anti-MBL antibody recognizing the multimeric form only [13].

Statistical analysis

Data on MBL2 genotypes and MBL protein levels in convalescence were analysed using a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The cut-off value derived from the ROC curve analysis was used to assess the MBL level as a predictor of MBL-deficient genotypes 0/0 and XA/0. Serum levels below this cut-off value were considered deficient.

The difference in MBL level between the acute and convalescent phases sera was analysed by genotype to measure the influence of the MBL2 genotype on acute-phase responsiveness of MBL. A decrease or increase of the MBL level by at least 25% in the acute phase compared with the convalescent phase was considered an acute-phase reaction [11,18]. When patients displayed deficient MBL concentrations in both the acute and convalescent phases, they were classified as not showing acute-phase responsiveness; therefore, the relative change in MBL level was considered 0%.

Genotype groups were compared first by means of univariate analysis. Unpaired continuous variables were analysed with a Student's t-test after correction for inequality of variances (based on Levene tests). Normality of the difference between two paired variables was analysed with use of a Kolmogorov–Smirnov procedure. For paired continuous variables with normally distributed differences, a paired Student's t-test was used. Paired continuous variables without normally distributed differences were analysed using a Wilcoxon's signed-ranks test. Categorical variables were analysed with a χ2 test or Fisher's exact test.

To adjust for confounders, multivariate logistical regression models using backward stepwise elimination by likelihood ratio tests were used. Because the Fine-score incorporates both patient (i.e. age and gender) and clinical characteristics, this score was used as the only extra covariate.

To measure the correlation between parameters, the Spearman's rho or Pearson's correlation coefficient was calculated, depending on the type and distribution of the data. Data were analysed with SPSS software version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

For 143 of the 201 included patients, whole blood samples and both acute and convalescent phases serum samples were available for analysing the dynamics of MBL levels in patients with CAP. In the remaining 58 patients, MBL acute-phase responsiveness could not be analysed because no convalescent-phase serum sample was available. They did not differ from the remaining study group in MBL levels on day 1 of admission (Student's t-test, P = 0·25) or MBL2 genotype (Fisher's exact test, P = 0·744). They were older than the remaining study group [67·9 ± 18·5 years versus 61·1 ± 16·7 years; mean ± standard deviation (s.d.); Student's t-test, P = 0·01], and they showed a higher mortality (nine of 58 versus one of 143; Fisher's exact test, P < 0·001).

The ROC curve of the data on MBL2 genotypes and MBL protein levels in convalescence suggested a cut-off value of 0·2 µg/ml for predicting genotypic MBL deficiency. The ROC curve had an area under the curve of 0·961 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0·925–0·997], and using 0·2 µg/ml as cut-off for MBL deficiency the sensitivity and specificity were maximized at 87·5% and 91·6% respectively. Therefore, MBL serum levels below the cut-off value of 0·2 µg/ml were considered deficient.

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The MBL2 genotype groups did not differ in age [analysis of variance (anova), P = 0·98], sex (χ2 test, P = 0·66) or Fine-score (anova, P = 0·50).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) by MBL2 genotype.

| MBL2 genotype | n | Age (years ± s.d.) | Sex (M : F) | Fine-score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 143 | 61·1 ± 16·7 | 1·6 : 1 | 81·2 ± 30·6 |

| YA/YA | 43 | 60·7 ± 15·6 | 1·2 : 1 | 75·5 ± 27·6 |

| XA/YA | 34 | 61·5 ± 17·1 | 2·1 : 1 | 86·2 ± 36·9 |

| YA/0 | 34 | 61·9 ± 14·7 | 2·1 : 1 | 87·4 ± 26·0 |

| XA/XA | 8 | 58·5 ± 24·9 | 1·7 : 1 | 76·0 ± 37·6 |

| XA/0 | 19 | 59·6 ± 19·3 | 1·4 : 1 | 78·1 ± 31·5 |

| 0/0 | 5 | 65·6 ± 16·5 | 0·7 : 1 | 75·6 ± 21·4 |

M; male; F; female; n; number of patients; s.d.; standard deviation.

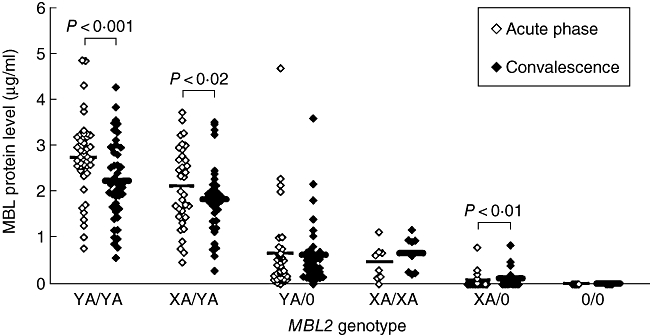

In overall analysis, the mean MBL level was increased significantly in the acute phase of disease compared with convalescence (1·51 ± 1·31 versus 1·30 ± 1·10 µg/ml, mean ± s.d. in acute phase versus convalescence respectively; Wilcoxon's signed-ranks test, P < 0·001). When analysed by genotype, the mean MBL level was increased significantly only in genotypes YA/YA (2·73 ± 0·86 versus 2·23 ± 0·88 µg/ml; paired Student's t-test, P < 0·001) and XA/YA (2·11 ± 0·85 versus 1·82 ± 077 µg/ml; paired Student's t-test, P = 0·02) (Fig. 1). No significant differences between the two time-points were found in genotype YA/0 (0·65 ± 0·91 versus 0·62 ± 0·72 µg/ml; Wilcoxon's signed-ranks test, P = 0·75), genotype XA/XA (0·46 ± 0·38 versus 0·66 ± 0·38 µg/ml; paired Student's t-test, P = 0·124) and genotype 0/0 (0·00 ± 0·00 versus 0·00 ± 0·00 µg/ml). Statistically, the MBL level was significantly lowered in the genotype XA/0 in the acute phase compared with convalescence, although the actual values and their difference were small (0·08 ± 0·19 versus 0·11 ± 0·23 µg/ml; Wilcoxon's signed-ranks test, P = 0·01).

Fig. 1.

Mannose-binding lectin (MBL) protein levels at the acute and convalescent phases of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) by MBL2 genotype. Mean MBL levels were increased significantly at the acute phase compared with convalescence in patients with genotypes YA/YA and XA/YA (paired Student's t-test). In patients with genotype XA/0, the mean MBL level was decreased only slightly yet statistically significant (Wilcoxon's signed-ranks test). (◊/♦, MBL level of an individual patient at the acute phase/convalescence; –, mean).

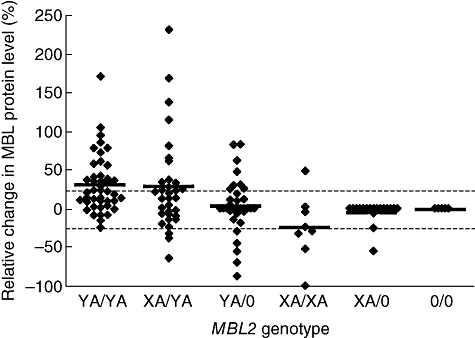

The relative change in MBL levels in the acute phase compared with convalescence, and hence the acute-phase responsiveness, also differed between genotypes (Fig. 2 and Table 2). Acute-phase responses of MBL were observed in 55 of 143 (38·5%) patients with CAP, of whom 40 (28·0%) showed a positive acute-phase response of MBL and 15 (10·5%) showed a negative response. Significantly more patients with MBL-sufficient genotypes showed acute-phase responses of MBL than patients with MBL-deficient genotypes [53 of 119 versus 2/24 patients respectively; χ2 test, P < 0·01, odds ratio (OR) 8·8, (95% CI 2·0–39·3)].

Fig. 2.

Dynamics of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) protein levels in community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) according to genotype. The relative change (%) of the MBL level in the acute phase of disease compared with the convalescent level is plotted, stratified by MBL2 genotype. The cut-off for positive (+25%) and negative (−25%) acute-phase responses are plotted (dotted lines). Positive acute-phase responses were associated with the presence of the YA haplotype and negative responses with its absence. (♦, individual patient; –, mean)

Table 2.

Relative change in mannose-binding lectin (MBL) levels in the acute phase compared with convalescence and acute-phase responsiveness (APR) of MBL by genotype.

| APR† (n, (%)) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBL2 genotype | n | Change in MBL level (mean % ± s.d.) | Total APR | Positive APR | Negative APR |

| Total | 143 | 14·6% ± 44·2 | 55 (38·5%) | 40 (28·0%) | 15 (10·5%) |

| YA/YA | 43 | 30·8% ± 37·5 | 20 (46·5%) | 19 (44·2%) | 1 (2·3%) |

| XA/YA | 34 | 27·7% ± 60·0 | 16 (47·1%) | 13 (38·2%) | 3 (8·8%) |

| YA/0 | 34 | 3·13% ± 35·8 | 12 (35·3%) | 7 (20·6%) | 5 (14·7%)‡ |

| XA/XA | 8 | −24·1% ± 43·0 | 5 (62·5%) | 1 (12·5%) | 4 (50·0%)‡ |

| XA/0 | 19 | −4·6% ± 13·6 | 2 (10·5%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (10·5%) |

| 0/0 | 5 | 0·0% ± 0·0 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

An increase (positive APR) or decrease (negative APR) of the MBL level by at least 25% in the acute phase compared with the convalescent phase was considered an acute-phase reaction. Patients displaying deficient MBL concentrations in both the acute and convalescent phases were classified as not showing acute-phase responsiveness and the relative change in MBL level was considered 0%.

Negative APR in genotype YA/0 versus XA/XA; P = 0·050, Fisher's exact test; s.d., standard deviation.

In patients with wild-type exon 1 genotype A/A who displayed acute-phase responsiveness of MBL, positive acute-phase responses were observed significantly more often in patients having at least one wild-type promoter Y allele (32 of 36 patients with genotype YA/YA or XA/YA versus one of five patients with genotype XA/XA; Fisher's exact test, P < 0·01). This correlation remained significant when corrected for possible confounding by differences in severity of disease, as expressed by the Fine-score in the multivariate logistic regression model [OR 32·0 (95% CI 2·9–361·8)].

In all A/A patients, negative acute-phase responsiveness was correlated with the absence of the promoter Y allele. MBL showed a negative acute-phase response in four of eight patients (50·0%) with genotype XA/XA, but in only four of 77 (5·2%) patients with either genotype XA/YA (three of 34 patients) or YA/YA (one of 43 patients) (Table 2; Fisher's exact test; P < 0·01). This correlation also remained significant in the multivariate analysis [OR 0·06 (95% CI 0·01–0·30)].

Mean convalescent MBL levels were similar in patients with genotypes XA/XA and YA/0 (0·66 ± 0·38 µg/ml versus 0·62 ± 0·72 µg/ml; Student's t-test; P = 0·87). Also in the acute phase, the mean MBL level did not differ significantly (0·46 ± 0·38 µg/ml versus 0·65 ± 0·91 µg/ml respectively; Student's t-test; P = 0·56). However, the mean difference between MBL levels at the acute phase and convalescence differed significantly between the two genotypes (−0·20 ± 0·32 µg/ml in XA/XA versus 0·04 ± 0·29 µg/ml in YA/0; Student's t-test; P = 0·05). Furthermore, negative acute-phase responses were observed significantly more often with genotype XA/XA than with YA/0 (4/8 XA/XA versus 5/34 YA/0; Fisher's exact test; P = 0·05).

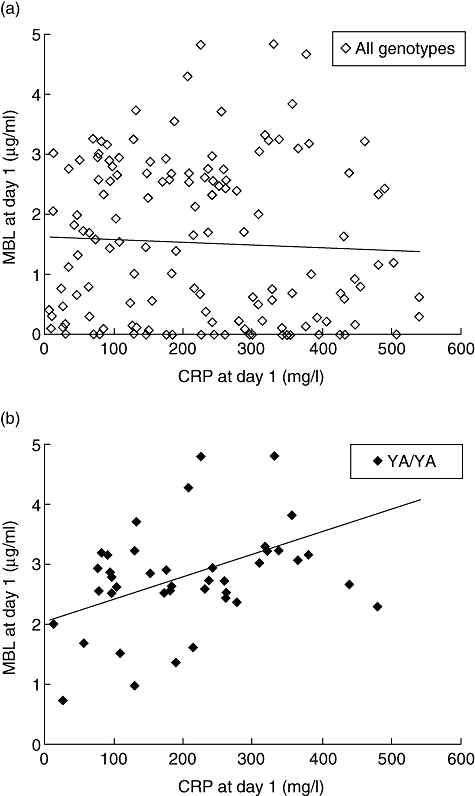

There was no significant correlation between MBL and CRP at day 1 of admission in overall analysis of all patients (Fig. 3a; Spearman's rho correlation coefficient −0·049, P = 0·56). However, in patients with wild-type genotype YA/YA there was a significant correlation between the two parameters (Fig. 3b; Spearman's rho 0·41, P = 0·01).

Fig. 3.

Correlation between mannose-binding lectin (MBL) protein levels and CRP in community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) at day 1 of admission. (a) There was no correlation between MBL and CRP in overall analysis of all genotypes. (b) However, MBL and CRP were correlated in patients with MBL2 genotype YA/YA (P = 0·01). (◊/♦, individual patient; –, regression line).

The correlation between the Fine-score and MBL levels at day 1 could be analysed in all 201 included patients. MBL levels at day 1 were not correlated with the Fine-score when all genotypes were included in the analysis (n = 201; Pearson's correlation coefficient −0·14, P = 0·85). However, when only patients with genotype YA/YA were analysed, a non-significant, negative trend was found between the Fine-score and MBL levels in the acute phase (n = 56; Pearson's correlation coefficient −0·241, P = 0·073). Acute-phase responsiveness, either positive or negative, was not correlated with the Fine-score in the patient group as a whole (n = 143), nor in those with genotype YA/YA (n = 43) (Spearman's rho, P > 0·09 for all analyses).

Discussion

Our results show that acute-phase responsiveness of MBL in patients with CAP was highly dependent upon the MBL2 genotype. In general, acute-phase responsiveness was observed more frequently in patients with MBL-sufficient genotypes than in patients with MBL-deficient genotypes. In patients with MBL-deficient genotypes, MBL levels were low in both the acute and convalescent phases of disease. In patients with wild-type exon 1 genotype A/A, acute-phase responsiveness of MBL was influenced by the promoter X/Y polymorphism. Positive acute-phase responsiveness was associated with the presence of the YA haplotype, while negative acute-phase responsiveness was associated with its absence. MBL and CRP levels at day 1 were not correlated in the study population as a whole. However, there was a significant correlation between them in patients with wild-type genotype YA/YA.

The current definition of acute-phase responsiveness based on relative changes in the protein level does not take into account whether absolute MBL levels are considered deficient. In this study, we considered patients with MBL levels below 0·2 µg/ml at both the acute and convalescent stages of pneumonia to be MBL-deficient at all time-points and therefore classified them as not having an acute-phase response of MBL.

The acute-phase response comprises a large number of systemic changes accompanying inflammation that can be distant from the site of inflammation and can involve many organ systems [18]. The concentration of many plasma proteins is changed during the acute-phase response, including several complement components [18]. Whether MBL exhibits an acute-phase response has been an issue of extensive debate since this was first postulated [7], as MBL responses have shown a high degree of heterogeneity. Monitoring of MBL serum levels after surgery has shown conflicting results [8–10]. When the MBL2 exon 1 genotype was considered, postoperatively increased MBL levels were found only in patients carrying wild-type exon 1 A/A alleles [19]. In patients with severe infection, no clear acute-phase response was evident from mean MBL levels, even when stratified by exon 1 genotypes (A/A versus A/0 and 0/0) [11]. However, 58·6% of the patients showed an acute-phase response either by increased (31·4%) or by decreased (27·3%) MBL levels in the acute phase. It was also found that, in community-acquired pneumococcal pneumonia, MBL did not act uniformly as an acute-phase reactant in all patients and no correlation with CRP levels was found [12].

Our results show that, besides exon 1 SNPs, the promoter X/Y polymorphism can also influence individual MBL acute-phase responsiveness. The deficient genotypes, XA/0 and 0/0, cannot display an acute-phase response, as MBL activity is absent at all phases. Positive and negative acute-phase responses in all other genotypes are reflected by the balance of up-regulating transcription of the wild-type A allele and the consumption of MBL. The promoter X SNP is thought to hamper this up-regulation. The influence of the X/Y promoter SNP on the capability of mounting an acute-phase response could be an explanation for the heterogeneity in MBL acute-phase responsiveness described in the studies above [10–12].

Our results are in accordance with a previous study showing that the capacity to increase MBL levels from day 1 to day 5 of febrile neutropenia in paediatric oncology patients was associated with the HY promoter haplotype [13]. In contrast to our results, increasing MBL levels were also found in the three paediatric patients with genotype XA/XA. This difference may be due to a difference in study design, as the MBL levels were followed longitudinally during the acute phase rather than comparing acute-phase and convalescent levels. Second, no cut-off was used to define whether the change in MBL concentration was considered an acute-phase reaction.

In the current study, a significant correlation between MBL and a known acute-phase reactant, CRP, could be demonstrated when genotypes were taken into account. CRP is capable of activating the classical complement pathway [20]. Interestingly, CRP has also been described to inhibit MBL-mediated complement activation via inhibition of the alternative pathway amplification loop, suggesting a co-ordinated role for these proteins in complement activation during the acute-phase response [21].

The effect of the X/Y promoter SNP on acute-phase responsiveness was also reflected in the different responses of genotypes XA/XA and YA/0. Both genotypes displayed comparable intermediate MBL levels in convalescence. In the acute phase, however, patients with genotype XA/XA displayed negative acute-phase responsiveness of MBL more often. This suggests that genotype XA/XA was less able to up-regulate production to compensate for the consumption of MBL in the acute phase than genotype YA/0. Therefore, it could be argued that if certain patient groups were to be supplemented with MBL, this supplementation should not be restricted to MBL-deficient genotypes but should also include genotype XA/XA.

No apparent relationship between MBL levels or acute-phase responsiveness at day 1 and the Fine-score were found when MBL2 genotypes were not taken into account. In patients with genotype YA/YA; however, a negative trend was found between the Fine-score and MBL levels in the acute phase. This observation suggests that in severe CAP the consumption of MBL exceeds the capacity of up-regulating production, even in patients with genotype YA/YA.

In conclusion, our data show that MBL acute-phase responsiveness is highly dependent upon the MBL2 genotype, where the X/Y promoter SNP determines the capability of mounting positive acute-phase responses in individuals with exon 1 wild-type genotype A/A. These data suggest that heterogeneity in protein responses should always be viewed in the light of possible influences of genetic differences in both the structural and the regulatory parts of the gene.

Acknowledgments

For each author, there are no potential conflicts of interest.

Disclosure

No funding was received for this study.

References

- 1.Hartshorn KL, Sastry K, White MR, et al. Human mannose-binding protein functions as an opsonin for influenza a viruses. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:1414–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI116345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neth O, Jack DL, Dodds AW, Holzel H, Klein NJ, Turner MW. Mannose-binding lectin binds to a range of clinically relevant microorganisms and promotes complement deposition. Infect Immun. 2000;68:688–93. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.2.688-693.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuipers S, Aerts PC, van Dijk DH. Differential microorganism-induced mannose-binding lectin activation. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003;36:33–9. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gomi K, Tokue Y, Kobayashi T, et al. Mannose-binding lectin gene polymorphism is a modulating factor in repeated respiratory infections. Chest. 2004;126:95–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madsen HO, Garred P, Thiel S, et al. Interplay between promoter and structural gene variants control basal serum level of mannan-binding protein. J Immunol. 1995;155:3013–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garred P, Pressler T, Madsen HO, et al. Association of mannose-binding lectin gene heterogeneity with severity of lung disease and survival in cystic fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:431–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI6861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ezekowitz RA, Day LE, Herman GA. A human mannose-binding protein is an acute-phase reactant that shares sequence homology with other vertebrate lectins. J Exp Med. 1988;167:1034–46. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.3.1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thiel S, Holmskov U, Hviid L, Laursen SB, Jensenius JC. The concentration of the C-type lectin, mannan-binding protein, in human plasma increases during an acute phase response. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;90:31–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb05827.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siassi M, Riese J, Steffensen R, et al. Mannan-binding lectin and procalcitonin measurement for prediction of postoperative infection. Crit Care. 2005;9:R483–9. doi: 10.1186/cc3768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ytting H, Christensen IJ, Basse L, et al. Influence of major surgery on the mannan-binding lectin pathway of innate immunity. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;144:239–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03068.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dean MM, Minchinton RM, Heatley S, Eisen DP. Mannose binding lectin acute phase activity in patients with severe infection. J Clin Immunol. 2005;25:346–52. doi: 10.1007/s10875-005-4702-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perez-Castellano M, Penaranda M, Payeras A, et al. Mannose-binding lectin does not act as an acute-phase reactant in adults with community-acquired pneumococcal pneumonia. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;145:228–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03140.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frakking FN, van de Wetering MD, Brouwer N, et al. The role of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) in paediatric oncology patients with febrile neutropenia. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:909–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Endeman H, Herpers BL, de Jong BA, et al. Mannose-binding lectin genotypes in susceptibility to community acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2008;134:1135–40. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:243–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701233360402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gabolde M, Muralitharan S, Besmond C. Genotyping of the three major allelic variants of the human mannose-binding lectin gene by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Hum Mutat. 1999;14:80–3. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1999)14:1<80::AID-HUMU10>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiertsema SP, Herpers BL, Veenhoven RH, et al. Functional polymorphisms in the mannan-binding lectin 2 gene: effect on MBL levels and otitis media. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1344–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabay C, Kushner I. Acute-phase proteins and other systemic responses to inflammation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:448–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Till JW, Boermeester MA, Modderman PW, et al. Variable mannose-binding lectin expression during postoperative acute-phase response. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2006;7:443–52. doi: 10.1089/sur.2006.7.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marnell L, Mold C, Du Clos TW. C-reactive protein: ligands, receptors and role in inflammation. Clin Immunol. 2005;117:104–11. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suankratay C, Mold C, Zhang Y, Potempa LA, Lint TF, Gewurz H. Complement regulation in innate immunity and the acute-phase response: inhibition of mannan-binding lectin-initiated complement cytolysis by C-reactive protein (CRP) Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;113:353–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00663.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]