Abstract

Mycobacterium leprae is an intracellular pathogen that survives within the phagosome of host macrophages. Several host factors are involved in producing tolerance, while others are responsible for killing the mycobacterium. Tryptophan aspartate-containing coat protein (TACO; also known as CORO1A or coronin-1) inhibits the phagosome maturation that allows intracellular parasitization. In addition, the Toll-like receptor (TLR) activates the innate immune response. Both CORO1A and TLR-2 co-localize on the phagosomal membrane in the dermal lesions of patients with lepromatous leprosy. Therefore, we hypothesized that CORO1A and TLR-2 might interact functionally. This hypothesis was tested by investigating the effect of CORO1A in TLR-2-mediated signalling and, inversely, the effect of TLR-2-mediated signalling on CORO1A expression. We found that CORO1A suppresses TLR-mediated signal activation in human macrophages, and that TLR2-mediated activation of the innate immune response resulted in suppression of CORO1A expression. However, M. leprae infection inhibited the TLR-2-mediated CORO1A suppression and nuclear factor-κB activation. These results suggest that the balance between TLR-2-mediated signalling and CORO1A expression will be key in determining the fate of M. leprae following infection.

Keywords: CORO1A, leprosy, Mycobacterium leprae, phagosome, TLR

Introduction

Pathogen recognition systems, which include the Toll-like receptors (TLRs), melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 and retinoic acid-inducible gene-1, function as biosensors for infection. Upon infection, activation of the innate immune system not only induces a primary biodefensive reaction, but is essential for activation of the adaptive immune system. TLRs are the pattern recognition receptors that sense and distinguish pathogen-associated molecular patterns that are found on a broad range of infectious agents [1]. TLRs also play an essential role in the eradication of engulfed pathogens [2,3]. Of the 13 known TLRs, TLR-2, in combination with TLR-1 or TLR-6, is responsible for the recognition of mycobacteria [4,5]. Bacterial and fungal cell wall components, such as peptidoglycan (PGN), lipoarabinomannan (LAM) and zymosan are well-known ligands of TLR-2 [6]. Notably, several studies have demonstrated that TLR-2 is recruited and localized to the phagosomal membrane following exposure to its ligands [7,8]

Macrophages play a central role in the innate immune system. They use cell surface TLR-2 and TLR-4 to recognize PGN, LAM or lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which stimulates phagocytosis and destruction of bacterial pathogens. Therefore, macrophages are part of the principal host defence system that operates during the early period of infection. However, some intracellular microorganisms evade detection and survive. It is thought that they reside and proliferate within cells by changing the intracellular environment. However, there is no one escape mechanism, and many have evolved their own strategies for intracellular survival. Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guérin (M. bovis BCG) utilizes a host protein, tryptophan aspartate-containing coat protein (TACO; also known as CORO1A or coronin-1), to escape detection by the immune system [9]. Upon M. bovis BCG infection, CORO1A is recruited, in association with tubulin, from the plasma membrane to the phagosomal membrane to play an essential role in inhibiting the phagosome–lysosome fusion, as well as in the survival of bacilli within macrophages. The phagosomal localization is transient in macrophages exposed to dead mycobacteria, whereas localization is quite stable when live bacilli are used. M. bovis BCG was digested completely in liver Küpffer cells, which lack CORO1A expression [9]. In addition, M. tuberculosis uses CORO1A to activate Ca2+-dependent phosphatase calcineurin, which blocks phagosome–lysosome fusion [10,11].

The M. leprae, the aetiological agent of leprosy, is a highly successful intracellular pathogen. M. leprae can survive within macrophage phagosomes as well as M. bovis and M. tuberculosis. We have reported recently that both TLR-2 and CORO1A localize on the membrane of phagosomes containing M. leprae[12]. However, the association between TLR-2 and CORO1A in leprosy is unknown. The goal of the present study was to investigate the functional interaction between two host proteins, CORO1A and TLR-2, which have opposing effects on the intracellular survival of M. leprae.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and infection

The human promonocytic cell line THP-1 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). They were cultured in 10-cm tissue culture dishes in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% charcoal-treated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2% non-essential amino acids and 50 mg/ml penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C in 5% CO2. Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells were obtained from ATCC. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS and 50 mg/ml of penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C in 5% CO2. M. leprae was prepared from the footpads of nude mice as described [12]. In some experiments, THP-1 cells were differentiated into macrophages by incubation in 50 nM phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) for 24 h before use.

Plasmid preparation

The cDNA encoding human CORO1A was polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-amplified using cDNA prepared from THP-1 cells and introduced into the MluI-XbaI site of the pCIneo mammalian expression vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The cDNAs encoding human TLR-2 and TLR-3 were purchased from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA, USA) and transferred to the pGA mammalian expression vector [13]. Human TLR expression plasmids were made using a luciferase reporter plasmid, p5×nuclear factor (NF)-κB-luc, purchased from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA, USA). pGL3 h interferon (IFN)-β was constructed using the human IFN-β promoter region −110 to +20 (relative to the transcription initiation site), which was PCR-amplified from human genomic DNA and cloned into the pGL3 basic luciferase reporter plasmid (Promega). The pGL3 control vector, with a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter, was also purchased from Promega. The sequences of the PCR products were verified using an ABI PRISM Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Transfection and reporter gene assay

The HEK293 (2 × 104) or THP-1 (1 × 106) cells were used in the reporter gene assays. Transfection into THP-1 cells was conducted using diethylaminoethyl-dextran [14]. The HEK293 cells were transfected using FuGene 6 (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol [15]. HEK293 cells were transfected with 40 ng of a human TLR expression plasmid (TLR-2, TLR-3 or TLR-4) in the presence or absence of 40, 80, 160 or 320 ng of CORO1A expression plasmid and 25 ng of either luciferase reporter plasmid (p5×NF-κB-luc), pGL3 Control or pGL3-hIFNβ. The total amount of DNA was adjusted using empty CMV4 plasmid. Cells were incubated for 36 h after transfection and then treated with 2 µg/ml PGN from Staphylococcus aureus (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) or M. leprae, poly(IC) (50 µg/ml), LPS (1 µg/ml) or tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α (50 µg/ml) for an additional 12 h. Luciferase activity was measured using the luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol [15,16]. To simulate infection, cells were incubated for 36 h after transfection of p5×NF-κB-luc, then treated with 2 µg/ml PGN and either live or heat-killed M. leprae (multiplicity of infection: 10), or a combination of the two for 12 h. Latex beads were used as a negative control for M. leprae infection.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed in a buffer containing 50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid, 0·1% NP40, 20% glycerol and protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete Mini; Roche) for 1 h. Samples were heated in sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) sample loading buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at 80°C for 10 min, then loaded onto a 10% denaturing SDS-Tris-glycine gel (Invitrogen). After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene membrane (Invitrogen). The membrane was washed with phosphate-buffered saline 0·1% Tween 20 (PBST), blocked with PBST containing 5% non-fat milk, and incubated with TACO antibodies. The membrane was probed subsequently with biotinylated donkey anti-rabbit antibodies and streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and then developed using the ECL Plus Western Blotting Detection Reagents (GE Healthcare).

Reverse transcription PCR and real-time PCR

RNA was prepared using RNeasy Mini Kits (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) with minor modifications of the manufacturer's protocol, as described previously [16,17]. Briefly, cells were washed with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline, resuspended in 600 µl of lysis solution and passed through a QIAshredder. After 600 µl of 70% ethanol was added, the mixture was purified through a spin column, washed with 600 µl of RW1 wash solution, and washed twice with 500 µl of RPE wash solution. Total RNA was eluted with 30 µl of RNase-free water.

To perform the semi-quantitative reverse transcriptional assay, 1 µg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). Touchdown PCR was adopted to adjust β-actin levels as the endogenous reference housekeeping gene. The following PCR primers were used: human β-actin, 5′-AGCCATGTACGTAGCCATCC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGTGGTGGTGAAGCTGTAGC-3′ (reverse); and human CORO1A, 5′-ACCTCCTGCCGTGACAAGCG-3′ (forward) 5′-TCCTGGAACAGGTCCGACTTTC-3′(reverse). PCR products were run on a 2% agarose gel.

Relative quantification of CORO1A mRNA expression was also performed with real-time PCR using TaqMan-N-(3-Fluoranthyl) maleimide (FAM)-minor groove binder (MGB) assays and automated analysis in an Applied Biosystems 7000 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The sequences of the human CORO1A primers were 5′-GTGCGCATCATCGAGCC-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACGAACACTGCACGCACG-3′ (reverse). The sequence of the TaqMan probe was 5′FAM-CACTGTCGTAGCTGAGAA-MGB3′. TaqMan β-actin detection reagents (Applied Biosystems) were used as a control.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated at least three times. Statistical significance was evaluated using Student's t-test with P < 0·05 considered statistically significant.

Results

CORO1A suppresses TLR-mediated signalling

Although both CORO1A and TLR-2 are expressed in macrophages and play important roles in mycobacterial infection, it is unclear if an interaction exists between the two. CORO1A and TLR-2 are recruited to, and co-localize on, the phagosomal membrane upon M. leprae infection [12], even though the two molecules have opposing effects. While CORO1A is involved in the survival of mycobacteria, TLR participates in the elimination of bacterial pathogens by activating the immune system. Thus, the co-localization of both proteins on the membrane of phagosomes that contain M. leprae prompted us to determine if there is a functional interaction between CORO1A and TLR.

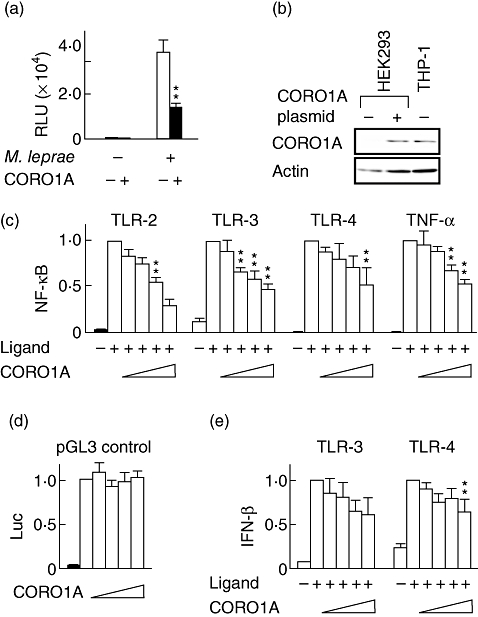

The effect of CORO1A on the activation of TLR-2-mediated signalling was examined using the THP-1 cell line. THP-1 cells express functional TLR-2 that can detect PGN and the cell wall glycolipids of M. leprae[18]. THP-1 cells transfected with either CORO1A expression plasmid or control plasmid were infected with M. leprae. NF-κB activation was evaluated by the measurement of luciferase levels. As shown in Fig. 1a, CORO1A suppressed NF-κB activation induced by M. leprae infection. CORO1A also suppressed NF-κB activation induced by PGN stimulation (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Tryptophan aspartate-containing coat protein (TACO; also known as CORO1A or coronin-1) suppresses Toll-like receptor (TLR) signalling. The human promonocytic cell line (THP-1) cells were transfected with a luciferase reporter plasmid, p5×nuclear factor (NF)-κB-luc, and incubated for 48 h before the addition of Mycobacterium leprae (multiplicity of infection: 10) or peptidoglycan (PGN) (2 µg/ml). Luciferase activity was measured 12 h after stimulation (a). Western blot analysis of CORO1A protein levels in human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells transfected with a CORO1A expression plasmid and in THP-1 cells (control) demonstrated that the same amount of cellular protein was present in both cell types (b). HEK293 cells were transfected with a luciferase reporter plasmid, p5×NF-κB-luc (c), pGL3-control (d) or pGL3-h interferon (IFN)-β (e) along with the indicated human TLR expression plasmid (TLR-2, TLR-3 or TLR-4) in the presence or absence of the CORO1A expression plasmid. PGN, poly(IC) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) were used as specific TLR-2, TLR-3 and TLR-4 ligands. Each ligand or tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α was added 36 h after transfection, and luciferase activity was measured 12 h after ligand stimulation. The results are presented as relative promoter activity in which luciferase activity in the absence of the CORO1A expression plasmid was set to 1·0 (c,d,e). The graph shows the mean ± standard deviation. One asterisk (*) indicates a value of P < 0·05, two asterisks (**) indicate a value of P < 0·01.

The specificity of the suppressive effect of CORO1A on NF-κB was investigated using HEK293 cells, which do not express TLR-2. Prior to the experiment, we confirmed that transfection of the CORO1A expression plasmid in HEK293 cells results in an amount of protein comparable to that produced in the THP-1 controls (Fig. 1b). HEK293 cells were co-transfected with hTLR-2 expression plasmid and an NF-κB-dependent luciferase reporter plasmid. Thirty-six hours after transfection, the cells were stimulated with PGN for 12 h and reporter gene activity was analysed. Consistent with the data obtained from THP-1 macrophage cells (Fig. 1a), CORO1A suppressed PGN-induced, TLR-2-mediated NF-κB activity in a dose-dependent manner in HEK293 cells (Fig. 1c). Interestingly, CORO1A suppressed both dsRNA-induced NF-κB activation through TLR-3 and LPS-induced NF-κB activation through TLR-4 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1c). Because TNF-α is a classic cytokine that induces NF-κB activation, it was possible that CORO1A influences the action of TNF-α. Indeed, CORO1A suppressed TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1c). Transfection of a plasmid carrying unrelated cDNA had no effect (data not shown). Therefore, suppression was specific to expressed CORO1A. The suppression was also specific to an NF-κB-dependent promoter, because pGL3 control (in which luciferase activity is controlled by the CMV promoter) was not influenced by CORO1A (Fig. 1d). These results suggest that CORO1A suppresses NF-κB activation, most probably by influencing the common signalling pathway shared by TLR and TNF-α. In a similar experiment using an IFN-β promoter-dependent luciferase reporter plasmid, CORO1A suppressed both TLR-3- and TLR-4-mediated IFN-β promoter activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1e), suggesting that CORO1A helps intracellular pathogens survive by suppressing activation of the innate immune system.

Activation of innate immunity modulates CORO1A expression

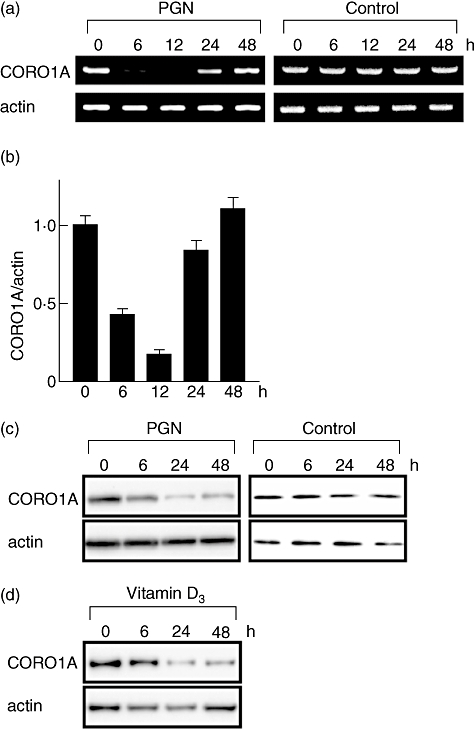

The effect of TLR-2-mediated signalling on CORO1A expression was assessed in THP-1 cells. THP-1 cells preactivated by PMA were used to test for an effect of PGN on differentiated macrophages; PGN decreased significantly CORO1A mRNA expression in 6–12 h (Fig. 2a). Quantitative evaluation of CORO1A mRNA levels by real-time PCR confirmed that RNA expression decreased 1/60 in 12 h, but returned to original levels in 24 h (Fig. 2b). CORO1A protein levels decreased 24–48 h after PGN stimulation (Fig. 2c). A similar decrease in CORO1A was induced by 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol (Fig. 2d), an active metabolite of 25-hydroxycholecalciferol (vitamin D3), which activates anti-mycobacterial mechanisms more effectively than IFN-γ in human macrophages [19]. These data suggest that macrophage activation results in CORO1A suppression regardless of the pathway of activation. Such a decrease in CORO1A protein levels might promote lysosomal fusion, thereby enhancing bacterial elimination within the phagosome.

Fig. 2.

Mycobacterium leprae infection modulates tryptophan aspartate-containing coat protein (TACO; also known as CORO1A or coronin-1) expression. Human promonocytic cell line (THP-1) cells (1 × 106) were cultured in a six-well plate, treated with 20 ng/ml of phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) for 48 h, and incubated with or without 2 µg/ml of peptidoglycan (PGN) (a, b and c) or 1 µM of the active form of vitamin D3 (1,25-dihydroxycholecalcifenol) (d). After incubating for the indicated time, total RNA and total cellular protein were isolated, and reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (a), quantitative real-time PCR (b) and Western blot analysis (c,d) were performed as described in the Materials and methods.

The M. leprae infection modulates CORO1A expression

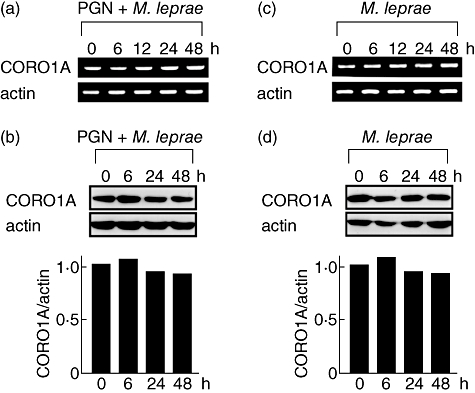

Although PGN suppressed CORO1A expression significantly (Fig. 2), the addition of M. leprae inhibited the ability of PGN to suppress CORO1A mRNA (Fig. 3a) and protein (Fig. 3b) levels, despite the fact that both PGN and M. leprae are recognized by TLR-2 and are capable of activating NF-κB. M. leprae infection alone did not modulate CORO1A expression significantly (Fig. 3c and d).

Fig. 3.

Mycobacterium leprae infection reverses peptidoglycan (PGN)-induced reduction of tryptophan aspartate-containing coat protein (TACO; also known as CORO1A or coronin-1) protein levels. Human promonocytic cell line (THP-1) cells (1 × 106) were cultured in a six-well plate, treated with 20 ng/ml of phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) for 48 h, and stimulated with 2 µg/ml of PGN and/or M. leprae (multiplicity of infection: 10). After incubating for the indicated time, total RNA and total cellular protein were purified and reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction analysis (a,c) and Western blot analysis (b,d) were performed. Densitometric analysis of the specific bands detected in the Western blot is shown in a bar graph.

Viable M. leprae suppresses TLR-2-mediated NF-κB activation

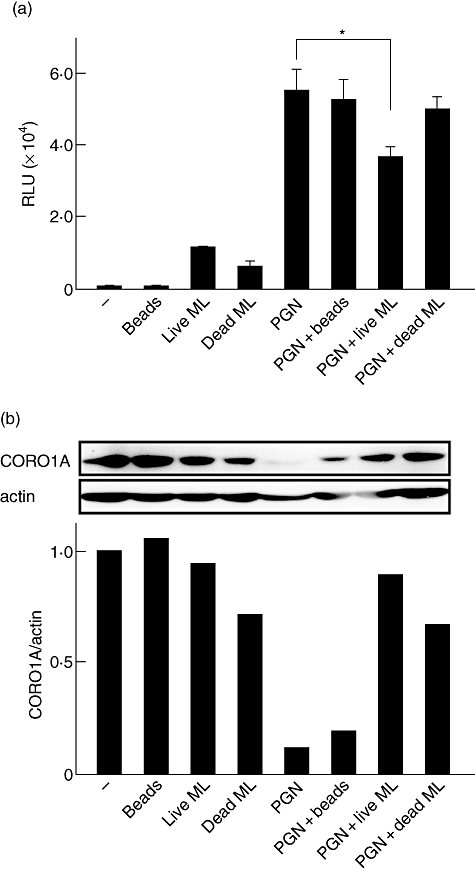

The modulation of CORO1A after M. leprae infection led to the hypothesis that M. leprae partially influences TLR-mediated signalling for survival within macrophages by sustaining CORO1A expression levels. To test this hypothesis, THP-1 cells were differentiated into macrophages by PMA, transfected with the NF-κB-dependent luciferase reporter plasmid and stimulated with PGN combined with viable M. leprae, heat-killed M. leprae or latex beads (control). Although viable and dead M. leprae activated NF-κB weakly, only the live bacteria suppressed PGN-induced NF-κB activation, while dead M. leprae and the latex beads did not (Fig. 4a). The CORO1A protein levels were suppressed only by PGN treatment, but were maintained by M. leprae (Fig. 4b), which corresponds to the results shown in Figs 2 and 3 respectively. PGN-induced suppression of CORO1A protein was counteracted by M. leprae (Fig. 4b). These results suggest that M. leprae infection antagonizes the suppressive effect of PGN on CORO1A levels, and that live bacilli have the ability to inhibit TLR-2-mediated activation of NF-κB.

Fig. 4.

Viable Mycobacterium leprae suppresses Toll-like receptor-2 (TLR-2)-mediated nuclear factor (NF)-κB activation. Human promonocytic cell line (THP-1) cells were transfected with the p5×NF-κB-luc plasmid and stimulated with latex beads, peptidoglycan (PGN) and either viable M. leprae, heat-killed (multiplicity of infection: 10) or a combination of the two. The graph shows the mean ± standard deviation of luciferase activity representing NF-κB-dependent promoter activation. The asterisk (*) indicates a value of P < 0·05. Three independent experiments produced similar results (a). Total cellular protein was purified 12 h after each treatment and Western blot analysis was performed (b). Densitometric analysis of the specific bands detected in the Western blot is shown in a bar graph.

Discussion

This study revealed evidence of a functionally inverse relationship between CORO1A and TLRs. In M. bovis BCG, CORO1A contributes to survival of bacilli by inhibiting fusion of the lysosome to the phagosome, a suppression that is abolished when CORO1A is absent [9]. TLR-2, upon recognition of mycobacteria, activates the innate immune response in order to protect cells from infection. The observation that both CORO1A and TLR-2 localize to phagosomal membranes that contain mycobacteria [12] was of interest because of the opposing functions of these two host factors. Previous studies in M. tuberculosis or M. bovis BCG focused upon the roles of either CORO1A or the TLRs in the process of mycobacterial infection, not their combinatorial effect. We used M. leprae, probably the most typical example of an intracellular pathogen, to investigate a possible interaction between CORO1A and TLR. Their co-localization on the phagosomal membrane led us to hypothesize that these two factors might interact, thereby influencing the fate of mycobacteria within infected macrophages.

An interaction between CORO1A and TLR-2 was confirmed using a number of different approaches. Although a physical interaction between CORO1A and TLRs was not observed in immunoprecipitation and yeast two-hybrid assays (data not shown), we found reciprocal antagonism in a functional interaction. CORO1A suppressed TLR-2-mediated NF-κB activation; TLR-3-, TLR-4- and TNF-α-stimulated NF-κB activation; and IFN-β promoter activation. One possible explanation is that CORO1A associates directly with a molecule that is downstream of both TLR and TNF-α signalling, such as NIK (NF-κB inducing kinase), inhibitor (I)κB or NF-κB. Another possibility is that CORO1A associates with other molecules such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase to suppress TLR signalling indirectly, as components of NADPH oxidase suppress TLR-2-mediated signalling [20]. Regardless of the molecular mechanism, our data suggest clearly that CORO1A not only blocks phagosome–lysosome fusion, but also reduces signalling in the pathways that lead to activation of innate immunity.

Conversely, the activation of macrophage, either by TLRs or the active form of vitamin D3, resulted in the suppression of CORO1A expression. Although the relationship between TLR and CORO1A is poorly understood, evidence suggests that vitamin D might be a factor that connects these two molecules. Thus, TLR might trigger the vitamin D-mediated human anti-microbial response through induction of cathelicidin [21,22]. Liu et al. found that the vitamin D receptor is up-regulated in monocytes stimulated with a synthetic 19-kDa M. tuberculosis-derived lipopeptide, and that cathelicidine mediates anti-microbial activity against M. tuberculosis. The suppressive effect of vitamin D on CORO1A gene expression was also found in human macrophages [23]. Therefore, it is plausible that activated TLR signalling by mycobacteria suppresses CORO1A expression through vitamin D.

Although PGN suppressed CORO1A expression, M. leprae did not affect CORO1A expression significantly despite the fact that M. leprae alone can activate NF-κB weakly. Rather, viable M. leprae has the ability to suppress TLR-2-mediated NF-κB activation. The results indicate that M. leprae activates NF-κB weakly through TLR-2; however, it suppresses PGN-induced NF-κB activation simultaneously. It has been reported that only viable M. bovis BCG can sustain CORO1A on the phagosomal membrane [9]. Therefore, we compared the effect of live and heat-killed M. leprae on CORO1A expression. Although there was no significant difference in total CORO1A protein levels between cells treated with viable or dead M. leprae, the phagosomal localization of CORO1A, which may affect TLR-2-mediated signalling directly, would differ [9,12]. Innate immune reactions would be activated upon recognition of M. leprae at the beginning of infection by TLRs. However, our results suggest that viable M. leprae utilizes a hitherto unknown strategy that leads to suppression of innate immune activities, at least in part, through inhibition of NF-κB activation. Although the suppression of PGN-induced NF-κB activation by M. leprae detected in this study was significant, the level of reduction was not very striking. However, the in vivo biological impact could be much stronger when the long-term parasitization of numerous bacilli within a macrophage is considered. We propose that such a function would be established during the process of successful intracellular parasitization. As a result, M. leprae infection maintains CORO1A expression levels and suppresses NF-κB activation.

A similar situation can be found in the regulation of adipophilin/adipose differentiation-related protein (ADRP) expression in M. leprae-infected macrophages [24]. Although PGN suppresses ADRP expression, infection by M. leprae inhibits the suppression. Therefore, it was speculated that live M. leprae actively induces and supports ADRP expression to facilitate the accumulation of lipids within the phagosome and to maintain a suitable environment for intracellular survival within macrophages [24]. Unlike other mycobacteria, M. leprae is not capable of activating dendritic cell-mediated T cell responses [25,26]. Our results may explain these previous observations by providing evidence that M. leprae suppresses NF-κB activation.

As reported previously, M. leprae can stimulate TLR-2, even though the stimulation is not as strong as that produced by purified PGN in in vitro experiments. The bacterial component that stimulates TLR-2 and activates NF-κB will be PGN or LAM on the M. leprae cell wall. In this study, we found that infection with viable M. leprae attenuates PGN-induced NF-κB activation, although the molecular mechanisms responsible have yet to be identified. This study demonstrates that M. leprae uses a host protein, CORO1A, to inhibit TLR-mediated signalling in order to create an environment more suited for survival. When macrophages are infected by mycobacteria, both killing and tolerant mechanisms are activated. A balance between activation and suppression of NF-κB by M. leprae might modulate disease severity after infection and affect the fate of infected bacilli, i.e. successful rejection or parasitization. Understanding their escape mechanisms will provide new ideas for the development of pharmaceutical or therapeutic strategies to fight pathogens.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sport, Science and Technology of Japan (to K. S.), the International Cooperation Research Grant from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan (to N. I.) and by a Grant-in-Aid for Research on Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan (to N. I.). The authors thank M. Mishima, D. B. Pham, Y. Ishido, S. Aizawa, M. Hayashi and S. Sekimura (LRC, NIID) for discussion.

Disclosure

None.

References

- 1.Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blander JM, Medzhitov R. Regulation of phagosome maturation by signals from Toll-like receptors. Science. 2004;304:1014–18. doi: 10.1126/science.1096158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brattig NW, Bazzocchi C, Kirschning CJ, et al. The major surface protein of Wolbachia endosymbionts in filarial nematodes elicits immune responses through TLR2 and TLR4. J Immunol. 2004;173:437–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ozinsky A, Smith KD, Hume D, Underhill DM. Co-operative induction of pro-inflammatory signaling by Toll-like receptors. J Endotoxin Res. 2000;6:393–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Underhill DM, Ozinsky A, Smith KD, Aderem A. Toll-like receptor-2 mediates mycobacteria-induced proinflammatory signaling in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14459–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeuchi O, Hoshino K, Akira S. Cutting edge: TLR2-deficient and MyD88-deficient mice are highly susceptible to Staphylococcus aureus infection. J Immunol. 2000;165:5392–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Underhill DM, Ozinsky A, Hajjar AM, et al. The Toll-like receptor 2 is recruited to macrophage phagosomes and discriminates between pathogens. Nature. 1999;401:811–15. doi: 10.1038/44605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ozinsky A, Underhill DM, Fontenot JD, et al. The repertoire for pattern recognition of pathogens by the innate immune system is defined by cooperation between toll-like receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13766–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250476497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrari G, Langen H, Naito M, Pieters J. A coat protein on phagosomes involved in the intracellular survival of mycobacteria. Cell. 1999;97:435–47. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80754-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jayachandran R, Sundaramurthy V, Combaluzier B, et al. Survival of mycobacteria in macrophages is mediated by coronin 1-dependent activation of calcineurin. Cell. 2007;130:37–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trimble WS, Grinstein S. TB or not TB: calcium regulation in mycobacterial survival. Cell. 2007;130:12–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki K, Takeshita F, Nakata N, Ishii N, Makino M. Localization of CORO1A in the macrophages containing Mycobacterium leprae. Acta Histochem Cytochem. 2006;39:107–12. doi: 10.1267/ahc.06010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ross TM, Xu Y, Bright RA, Robinson HL. C3d enhancement of antibodies to hemagglutinin accelerates protection against influenza virus challenge. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:127–31. doi: 10.1038/77802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suzuki K, Lavaroni S, Mori A, et al. Autoregulation of thyroid-specific gene transcription by thyroglobulin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8251–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takeshita F, Suzuki K, Sasaki S, Ishii N, Klinman DM, Ishii KJ. Transcriptional regulation of the human TLR9 gene. J Immunol. 2004;173:2552–61. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki K, Mori A, Saito J, Moriyama E, Ullianich L, Kohn LD. Follicular thyroglobulin suppresses iodide uptake by suppressing expression of the sodium/iodide symporter gene. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5422–30. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.11.7124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki K, Kobayashi Y, Katoh R, Kohn LD, Kawaoi A. Identification of thyroid transcription factor-1 in C cells and parathyroid cells. Endocrinology. 1998;139:3014–17. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.6.6126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krutzik SR, Ochoa MT, Sieling PA, et al. Activation and regulation of Toll-like receptors 2 and 1 in human leprosy. Nat Med. 2003;9:525–32. doi: 10.1038/nm864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang TT, Nestel FP, Bourdeau V, et al. Cutting edge: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 is a direct inducer of antimicrobial peptide gene expression. J Immunol. 2004;173:2909–12. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takeshita F, Ishii KJ, Kobiyama K, et al. TRAF4 acts as a silencer in TLR-mediated signaling through the association with TRAF6 and TRIF. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2477–85. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu PT, Stenger S, Li H, et al. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science. 2006;311:1770–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1123933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu PT, Stenger S, Tang DH, Modlin RL. Cutting edge: vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis is dependent on the induction of cathelicidin. J Immunol. 2007;179:2060–3. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anand PK, Kaul D. Vitamin D3-dependent pathway regulates TACO gene transcription. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;310:876–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanigawa K, Suzuki K, Nakamura K, et al. Expression of adipose differentiation-related protein (ADRP) and perilipin in macrophages infected with Mycobacterium leprae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;289:72–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hashimoto K, Maeda Y, Kimura H, et al. Mycobacterium leprae infection in monocyte-derived dendritic cells and its influence on antigen-presenting function. Infect Immun. 2002;70:5167–76. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.9.5167-5176.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murray RA, Siddiqui MR, Mendillo M, Krahenbuhl J, Kaplan G. Mycobacterium leprae inhibits dendritic cell activation and maturation. J Immunol. 2007;178:338–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]