Abstract

We describe the rational design of a novel class of magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents with engineered proteins (CAi.CD2, i = 1, 2, …, 9) chelated with gadolinium. The design of protein-based contrast agents involves creating high coordination Gd3+ binding sites in a stable host protein using amino acid residues and water molecules as metal coordinating ligands. Designed proteins show strong selectivity for Gd3+ over physiological metal ions such as Ca2+, Zn2+, and Mg2+. These agents exhibit a 20-fold increase in longitudinal and transverse relaxation rate values over the conventional small molecule contrast agents, e.g., Gd-DTPA (diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid), used clinically. Furthermore, they exhibit much stronger contrast enhancement and much longer blood retention time than Gd-DTPA in mice. With good biocompatibility and potential functionalities, these protein contrast agents may be used as molecular imaging probes to target disease markers, extending applications of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

1. Introduction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a non-invasive technique providing high resolution, three-dimensional images of anatomic structures as well as functional and physiological information about tissues in vivo. It is capable of detecting abnormalities in deep tissues and allows for whole body imaging. It has emerged as a primary diagnostic imaging technique.1, 2 Exogenous MRI contrast agents are often used to enhance the contrast between pathological and normal tissues by altering the longitudinal and transverse (i.e., T1 and T2) relaxation times of water protons.3–5 Gadolinium (Gd3+) chelators are the most frequently used MRI contrast agents due to their high magnetic moment, asymmetric electronic ground state, and potential for increased MRI intensity.6, 7 The relaxivity (unit capability of the agent to change the relaxation time) of a contrast agent is dependent on several factors including the number of water molecules in the coordination shell, the exchange rate of the coordinated water with the bulk water, and the rotational correlation time τR of the molecule.8–10 It is important for an MRI contrast agent to have: 1) high relaxivity for high contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) and dose efficiency, 2) thermodynamic and chemical stability, especially metal selectivity for the selected lanthanide ions over excess physiological metal ions, to minimize the release of toxic lanthanide ion, 3) adequate vascular, tissue retention time for sufficient imaging time, and 4) propensity for timely excretion from the body.

To date, the most commonly used MRI contrast agent in diagnostic imaging is Gd-DTPA (diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid), or related derivatives such as Gd-DTPA-BMA (bismethylamide). However, with an intrinsic rotational correlation time, τR, of 100 picoseconds, these small molecular Gd3+ chelators have longitudinal and transverse proton relaxivities, r1 and r2, less than 10 mM−1s−1, much lower than the theoretically maximal value (>100 mM−1 s−1).9, 11 In addition, these small molecule contrast agents exhibit very short blood circulation (less than 30 minutes) and tissue retention time, limiting some MRI applications that require longer data collection time.12 To increase correlation time, τR, small molecular contrast agents were covalently or non-covalently bound to macromolecules such as linear polymers,13 dendrimers,14, 15 carbohydrates,16 proteins,17–21 viral capsids,22 and liposomes23. An increase in relaxivity was observed when Gd3+ binds to calcium binding peptides24 or proteins such as concanavalin A and bovine serum albumin (BSA).6 However, the application of these short EF-hand peptides or proteins as MRI contrast agents is limited due to their weak metal binding affinity for Gd (Kd ~ 100 μM for Eu3+) and dynamic flexibility.24, 25 In addition, conjugation yields limited improvement due to internal mobility and restricted water exchange rate (Fig. 1a).11

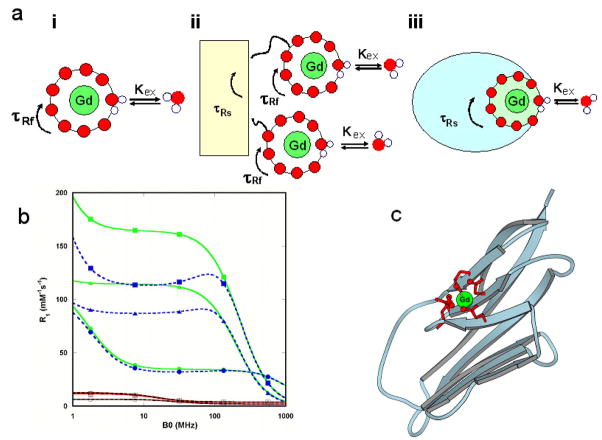

Figure 1.

Schematic descriptions of different classes of MRI contrast agents and simulation of T1 relaxivity. (a) Different constructs of MRI contrast agents. (i) Small chelator DPTA with a fast τR (τRf) at ~ 100ps level; (ii) small contrast agents after being covalently conjugated to macromolecules with a slow τR (τRs) still possess a fast τR due to its internal mobility; (iii) Schematic description of the design of reported MRI contrast agents by directly coordinating Gd3+ ions to ligand residues on a rigid protein frame to eliminate the high internal mobility. The rotational correlation time of the Gd3+ binding site is the same as that of the whole protein (τRs). (b) Simulated T1 relaxivity at the given rotational correlation time τR (100 ps, red and black, or 10 ns, green and blue), dwell time τm, correlation time of splitting τv (1 and 10 ps, solid and dashed lines, respectively), and mean square zero field splitting energy Δ2 (1018 s−2). The τm values are 10−10 (○), 10−9 (□), and 10−8 s (Δ) for 100 ps τR and 10−9 (●), 10−8 (■), and 10−7 s (▲) for 10 ns τR according to the theory developed by Blombergen and Solomon.6, 7 The water coordination number, q, is assumed to be 1 and the agent concentration is 0.001 M. See online supporting materials for r1 and r2 simulations. (c) Modeled structure of designed Gd3+-CA1.CD2 based on the designed NMR structure 1T6W.28 Ligand residues E15, E56, D58, D62 and D64 at the B, E, and D β-strands of the host protein CD2 are shown in red.

Here, we report the development of a new class of MRI contrast agents with significantly improved relaxivity using rational design of Gd3+-binding proteins (CAi.CD2, i = 1, 2, …, 9). We chose domain 1 of rat CD2 (referred to as CD2), a cell adhesion protein with a common immunoglobin fold, as a scaffold. CD2 protein exhibits strong stability against pH changes and excellent tolerance against various mutations,26 which are essential features required for functional protein engineering. In addition, CD2 has a compact structure with rotational correlation time, τR, of ~10 ns, corresponding to optimal relaxivity for the current clinically allowed magnetic field strength.27 Moreover, its molecular size (12 kDa) is suitable for good intravascular distribution and easy renal excretion.17 Our contrast agents was created by designing the metal binding sites into CD2 with desired dynamic properties and metal selectivity to increase relaxivity by optimizing local τR.. This approach provides a new platform for developing MRI contrast agents with high relaxivity and functionality.

2. Materials and Methods

Determination of the dynamic properties of the designed proteins

The dynamic properties of the proteins have been monitored via hydrogen exchange and dynamic nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) using established methods27, 28 and 15N labeled proteins29–31 by measuring T1, T2, and nuclear overhauser effect (NOE) to calculate order parameters S2. Briefly, 15N-enriched protein contrast agents with either 10 mM CaCl2 or 1 mM EGTA used for the backbone dynamic study were engineered, expressed, and purified as previously described.32 The assignment of NMR spectra of the protein was achieved through standard methods and procedures as previously described.33 The T1 and T2 relaxation times and heteronuclear NOE were measured using conventional pulse sequences.34, 35 The S2 order parameters were calculated using Modelfree version 4.15 provided by Dr. Palmer of Columbia University.36, 37 The D‖/D⊥ and τm were also obtained from the calculation, and the axes of inertia were automatically assigned by the Modelfree program.

Determination of r1 and r2 Relaxivity Values

Relaxation times, T1 and T2, were determined at 1.5, 3, 9.4 Tesla using Siemens whole-body MR system (1.5, 3T) or a Bruker MRI scanner (9.4T). T1 was determined using inversion recovery and T2 using a multi-echo Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) sequence. The contrast agent samples (200 μl) with different concentrations were placed in Eppendorf tubes. The tubes were placed on a tube rack, which was placed in the MRI scanners for the measurement of relaxation times. r1 and r2 were calculated based on r1 (mM−1S−1) = (1/T1s −1/T1c)/C and r2 (mM−1S−1) = (1/T2s-1/T2c)/C, where T1s and T2s are relaxation times with contrast agent and T1c and T2c are relaxation times without contrast agent. C is the concentration of contrast agent in mM (the measured Gd3+ concentrations by Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS)).

Measurement of Water Coordination Number by Terbium Lifetime Luminescence

The number of water ligands coordinated to Gd3+-CA1.CD2 complex was determined by measuring Tb3+ luminescence decay in H2O or D2O. The Tb3+ excited state lifetime was measured using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Photon Technology International, Inc.) with a 10 mm path length quartz cell at 22 °C. Following excitation at 265 nm with a XenoFlash lamp (Photon Technology International, Inc.), Tb3+ emission was monitored at 545 nm in a time series experiment in both H2O and D2O systems. Luminescence decay lifetime was obtained by fitting the acquired data with a mono-exponential decay function. H2O in CA1.CD2 solution was replaced with D2O by lyophilization and re-dissolved in D2O at least three times. A standard curve correlating the difference of rate constants obtained in H2O and D2O (Δkobs = kH2O - kD2O) with water number (q) under our experimental conditions was established by using well-characterized chelators, such as Tb3+-EDTA (q=3), Tb3+-DTPA (q=1), Tb3+-NTA (q=5), and Aquo Tb3+ (q=9) solution with R2=0.997.38, 39 The water number coordinated to the Tb3+-CA1.CD2 complex was then obtained by fitting the acquired Δkobs value to the standard curve.

Gd3+-binding Affinity Determination

Gd3+-binding affinity of CA1.CD2 was determined by a competition titration with Fluo-5N (a metal ion indicator, Invitrogen Molecular Probes) applied as a Gd3+ indicator. The fluorescence spectra of Fluo-5N were obtained with a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Photon Technology International, Inc.) with a 10 mm path length quartz cell at 22 °C. Fluo-5N emission spectra were acquired at 500 nm to 650 nm with an excitation at 488 nm. Gd3+-binding affinity of Fluo-5N, Kd1, was first determined by a Gd3+ titration with Gd3+ buffer system of 1 mM nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA). Free Gd3+ concentration was calculated with a NTA Gd3+-binding affinity of 2.6 × 10−12 M.40 Fluo-5N was mixed with Gd3+ in 1:1 ratio for a competition titration. The experiment was performed with a gradual addition of CA1.CD2. An apparent dissociation constant, Kapp, was estimated by fitting the fluorescence emission intensity of Fluo-5N at 520nm with different CA1.CD2 concentrations as a 1:1 binding model. Gd3+-binding affinity of CA1.CD2, Kd2, was calculated with the following equation:

| (1) |

Mouse MR Imaging

CD-1 mice (25 – 30 g, N=4) were used for MRI experiments. Care of experimental animals was conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines. Each animal was anesthetized with an isoflurane gas mixture and then positioned and stabilized in the scanner in the coil cradle. Each animal was kept warm during the MRI scan. The mice were scanned before and after the administration of any contrast agents. For contrast enhanced MRI, approximately 50 μl of Gd3+-CA1.CD2 (~1.2 mM) or Gd3+-DTPA (~300 mM) were injected into the animal via the tail vein. MR images were collected at multiple times. For T1 weighted imaging at 3T, spin echo sequence with TE/TR = 15 ms/500 ms was employed. Rectangular Field of View (FOV) at 100/40 mm, an acquisition matrix of 1962 and 1.1 mm slice thickness without gap were used. Images were collected from both transverse and coronal sections. The in-plane resolution of images was less than 0.5 mm after they were reconstructed to the matrix of 1962. For T2 weighted imaging at 9.4T, MR images were recorded using a multi-echo Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) sequence. The data were collected and analyzed using Dicomworks software. The MR signal intensity in several organs was ascertained by the average intensity in the defined regions of interest (ROIs) or voxels within the organs. Signal intensity for each organ was normalized to that of the leg muscle.

Blood Circulation Time, Tissue Retention Time, and Bio-distribution

Appropriate dosages of Gd3+-CA1.CD2 or Gd3+-DTPA were intravenously-injected (via tail vein). Blood (~50 μl) samples were collected via orbital sinus at different time points. Each of animals (N=4) was euthanized at the final time point. Tissue samples from kidney, liver, heart, and lung were collected. Serum samples were prepared from the collected blood. For the bio-distribution analyses, the animals were euthanized at single time point (indicated) after IV administration of the contrast agent (indicated). The organ/tissue samples were collected. Tissue extracts were freshly made from collected samples using commercially-available tissue extracting kits (Qiagen). CA1.CD2 was detected and quantified by immunoblotting and Sandwich Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay (Sandwich-ELISA) using a monoclonal antibody (OX45, detecting antibody) and a homemade polyclonal antibody (PabCD2, capture antibody). A series of known amounts of CA1.CD2 samples mixed with blank mouse serum or tissue extracts were used as standard in Sandwich-ELISA. ELISA signal from Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was monitored using a Fluostar fluorescence microplate reader. For quantification of Gd3+ in the serum and tissue samples one hour (or indicated times) after the contrast agent administration, animals were sacrificed and critical organs were collected, and the tissues were then digested with concentrated nitric acid at 120–130°C with proper amount of 157Gd spike as an internal marker. The digested solution was analyzed by ICP-MS (Element 2) using an isotope dilution method.

Toxicity Analyses

After MRI experiments, CD-1 mice that received Gd3+-CA1.CD2 (at a dose of ~2.4 μmol/kg) were returned to their cages (one mouse per cage). The mice were observed for five days and were euthanized at the end of the fifth day. Tissue samples from kidney, liver, spleen, and lung were collected. Gd3+ ion contents in the tissue samples were analyzed by ICP-MS (see above paragraph).

Two groups of mice were used to examine potential renal and/or liver damage by Gd3+-CA1.CD2. One group of mice received (IV tail veil) 50 μl of saline-buffer as control. Another group received (IV tail veil) Gd3+-CA1.CD2 at a dosage of 4 μmol/kg. The mice were observed for 48 hours and were euthanized. Blood samples were collected from the experimental mice. Serum samples were prepared from the collected blood. Liver enzymes in serum samples, including Alanine transaminase (ALT), Alkaline phosphatase (ALP), Aspartate transaminase (AST), Gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), and bilirubin and urea nitrogen were analyzed by a commercially-available source (MU Research Animal Diagnostic Laboratory). All histo-chemistry parameters were measured on an Olympus AU 400 analyzer.

Cytotoxicity was analyzed by MTT (3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay of the cells that were treated with Gd-CA1.CD2 at appropriate doses (indicated in Supplementary Fig. S4b). The cells were grown under normal growth medium in 96 well plates. Gd-CA1.CD2 or saline-phosphate buffer was added to the cell culture medium. The cells were incubated for appropriate times. A standard MTT assay was employed to assess the cell growth status of the treated cells.

Serum stability

CA1.CD2 (40 μM) in complex with Gd3+ was incubated with 75% human serum over 3 or 6 hours at 37 °C. The degradation of the protein (disappearance of 12 kDa protein band) was analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and visualized by coomassie blue staining. In parallel, the degradation of the protein was also analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies OX54 or PabCD2. The identities of the 12 kDa bands as CA1.CD2 were always verified by immunoblotting using antibody PabCD2.

3. Results

Rational Design of Gd3+-binding Proteins

Fig. 1 shows the simulation of the dependence of r1 and r2 on the rotational correlation time, τR, of a contrast agent at different magnetic field strengths according to the theory developed by Blombergen and Solomon6, 7 (for detailed simulation procedures, please see online supporting materials). For small molecules such as Gd3+-DPTA with τR at hundreds of ps, the relaxivity is < 10 mM−1s−1 regardless of how the other parameters are adjusted. On the other hand, the simulation clearly suggests that contrast agents with τR of 10–50 ns have the highest r1 and r2 values at clinically relevant magnetic field strengths from 0.47–4.7 Tesla (T).11 Thus, we envisioned that high-relaxivity MRI contrast agents can be developed by directly designing Gd3+ binding sites in proteins with desired τR. Coordinating Gd3+ ions directly to the rigid protein frame eliminates the high internal mobility associated with chelator-macromolecule conjugates (Fig. 1a).

We next designed a series of Gd3+ binding sites into CD2 using computational methods.41, 42 These designs were based on established structural parameters obtained from detailed analysis of metal binding sites in over 500 small chelators and metalloproteins. Gd3+, Tb3+, La3+ and other Ln3+ ions have coordination properties similar to those of Ca2+ with a strong preference for oxygen ligand atoms.43 Small chelators usually have on average 9.3 and 6.9 total coordinating atoms for Gd3+ and Ca2+, respectively. For example, DTPA has 5 oxygen ligand atoms and 2 nitrogen ligand atoms. For macromolecules such as proteins, the coordination atoms are almost always oxygen atoms, and the coordination numbers are lower than small chelators with an average of 7.2 for Ln3+ and 6.0–6.5 for Ca2+. These effects are possibly due to steric crowding and sidechain packing.43 Previously, we successfully designed Ca2+ and Ln3+ binding sites in a scaffold protein with strong target metal selectivity in the presence of excess physiological metal ions.32 Structure determination by solution NMR revealed that the actual coordination geometry in a designed variant is the same as our design, verifying the computational methods and the design strategy of metal-binding sites in proteins.28

The designed proteins were named as CAi.CD2, i = 1, 2, …, 9, reflecting Gd3+-binding sites at different locations. Fig. 1c shows an example of designed Gd3+-binding protein CA1.CD2 with a metal binding site formed by the six potential oxygen ligands from the carboxyl side chains of Glu15, Glu56, Asp58, Asp62 and Asp64. Based on our studies of charged residues in the coordination shell,44 we placed 5 negatively-charged residues in the coordination shell of CA1.CD2 to provide six oxygen ligand atoms to increase the selectivity for Gd3+ over Ca2+. To achieve the desired relaxation property, one position of the metal binding geometry was left open in the design to allow fast water exchange between the paramagnetic metal ion and the bulk solvent (Fig. 1a). Importantly, the Gd3+-binding site has minimal internal flexibility as the ligand residues originate from rigid stretches of the protein frame. To test the requirement for rigid embodiment in achieving high relaxivity, another Gd3+-binding protein, CA9.CD2, was engineered by fusing a continuous cation-binding EF-hand loop from calmodulin (CaM) with flexible glycine linkers to the host protein.45, 46 The properties of this protein mimic previously reported, highly flexible chelate-based contrast agents conjugated to macromolecules.24, 25

All of the designed Gd3+ binding proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli and subsequently purified by procedures previously published from our laboratory.27, 28 All of the designed proteins form the expected metal-protein complex as demonstrated by electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) (Supplementary Fig. S1). Since metal selectivity for Gd3+ over other physiological metal ions is important for minimizing the toxicity of the agents,47, 48 we measured metal binding constants using dye-competition assays with various chelate-metal buffer systems (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. S2). Low limit metal binding affinities of the proteins were also estimated based on Tb3+-sensitized fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) and competition assays. CA1.CD2 exhibited disassociation constants (Kd, M) of 7.0 × 10−13, 1.9 × 10−7, 6 × 10−3, and > 1×10−2 for Gd3+, Zn2+, Ca2+, and Mg2+, respectively. The selectivity KdML/KdGdL for Gd3+ over physiological divalent cations Zn2+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ are 105.34, >109.84, and > 1010.06, respectively. The Gd3+ selectivity of CA1.CD2 is significantly greater than or comparable to that of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved contrast agents DTPA-and DTPA-BMA48 (Table 1). The high Gd3+ binding selectivity of CA1.CD2 was further supported by the observation that r1 and r2 of Gd3+-CA1.CD2 were not altered in the presence of excess Ca2+ (10 mM) (Fig. 2). Further assays showed that potential chelators in serum, such as phosphate (50 mM), were not able to remove the Gd3+ from the Gd3+-protein complex. This is important for in vivo applications of the contrast agent as the phosphate concentration in serum is maintained at ~1.3 mM.6, 9 The stability of a contrast agent in blood circulation is another important factor for in vivo applications. We characterized the stability by incubating Gd3+-CA1.CD2 with 75% human serum at 37 °C for 3 and 6 hours. The Gd3+-protein complex remained intact after 6 hours of incubation, indicating that the Gd3+-protein complex is stable in blood. Taken together, the designed Gd3+-protein contrast agent is comparable to the clinically used contrast agents in Gd3+ binding stability and selectivity.6, 7

Table 1.

Metal binding constants (Log Ka) and metal selectivity of DTPA, DTPA-BMA and CA1.CD2

| Sample | Gd3+ | Zn2+ | Ca2+ | Mg2+ | Log (KGd/KZn) | Log (KGd/KCa) | Log (KGd/KMg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DTPA40 | 22.45 | 18.29 | 10.75 | 18.20 | 4.17 | 11.70 | 4.25 |

| DTPA-BMA49 | 16.85 | 12.04 | 7.17 | na* | 4.81 | 9.68 | na* |

| CA1.CD2 | 12.06 | 6.72 | <2.22 | <2.0 | 5.34 | >9.84 | >10.06 |

na: not available.

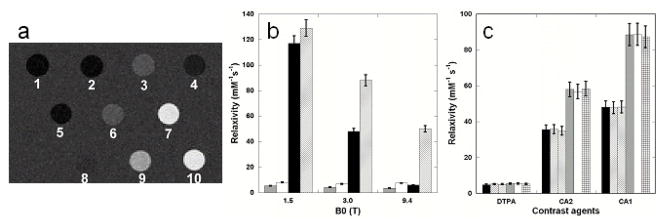

Figure 2.

Comparison of in vitro relaxivity between DTPA and designed contrast agents. (a) MR images produced using an inversion recovery sequence (TR 6000 ms, TI 960 ms, and TE 7.6 ms) at 3T. Samples are 1) dH2O, 2) 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 3) 0.10 mM Gd3+-DTPA in H2O, 4) 0.10 mM Gd3+-DTPA in 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 5) 0.10 mM Gd3+ and CD2, 6) 0.077 mM Gd3+-CA4.CD2, 7) 0.050 mM Gd3+-CA2.CD2, 8) 0.10 mM Gd3+-CA9.CD2, 9) 0.020 mM Gd3+-CA1.CD2, and 10) 0.050 mM Gd3+-CA1.CD2. (b) Proton relaxivity values of Gd3+-CA1.CD2 (r1, solid black; r2, cross) and Gd3+-DPTA (r1, shield; r2, open) at indicated field strength were measured as a function of field strength. (c) In vitro relaxivity of contrast agents Gd3+-DPTA (DTPA), Gd3+-CA1.CD2 (CA1) and Gd3+-CA2.CD2 (CA2) in the absence of Ca2+ (black and grey), presence of 1 mM Ca2+ (left strip and open) and 10 mM Ca2+ (right strip and cross) at 3T. T1 (black, left & right strips) and T2 (grey, open and cross) were determined using a Siemens whole-body MR system.

The designed Gd3+-binding proteins exhibit high r1 and r2 relaxivity

We have determined the relaxivity values of the designed protein contrast agents at field strengths of 1.5, 3.0 and 9.4 Tesla field strengths (Fig. 2). Fig. 2a shows that, at a concentration of 50 μM, the designed contrast agents Gd3+-CA1.CD2 and Gd3+-CA2.CD2 were able to introduce contrast enhancement in T1 weighted imaging at 3.0 T while 100 μM Gd3+-DTPA and protein CA1.CD2 alone did not lead to significant enhancement. The in vitro relaxivity values of the designed Gd3+-binding proteins were measured (Table 2). Gd3+-CA1.CD2 exhibits r1 up to 117 mM−1 s−1 at 1.5T, about 20-fold higher than that of Gd3+-DTPA. In contrast, Gd3+-CA9.CD2, which carries a flexibly-conjugated Gd3+-binding site, had significantly lower relaxivity values (3.4 and 3.6 mM−1s−1, for r1 and r2 respectively, at 3.0 T), that are comparable to those of Gd3+-DTPA (Table 2). These data support the conjecture that elimination of the intrinsic mobility of the metal binding site resulted in the desired high relaxivity values.

Table 2.

Proton relaxivity of different classes of contrast agents

| CA class | Compounds (ligand residues) | r1 (mM−1 s−1) | r2 (mM−1 s−1) | B0 (T) | MW(kDa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Designed proteins | Gd3+-CA1.CD2 (E15/E56/D58/D62/D64) | 117 | 129 | 1.5 | 12 |

| 48 | 88 | 3 | |||

| 6 | 50 | 9.4 | |||

|

| |||||

| Gd3+-CA2.CD2 (D15/D17/N60/D62) | 35 | 58 | 3 | 12 | |

|

| |||||

| Gd3+-CA3.CD2 (E15/E56/D58/D62/E64) | 130 | 1.5 | |||

| 34 | 57 | 3 | 12 | ||

|

| |||||

| Gd3+-CA9.CD2 (Add EF-loop III from Calmodulin) | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3 | 12 | |

|

| |||||

| Small compound | Gd3+-DTPA | 5.4 | 8 | 1.5 | |

| 4.2 | 6.8 | 3 | 0.743 | ||

|

| |||||

| * Protein carriers | Albumin | 11.5 | 12.4 | 0.25 | 80 |

|

|

|||||

| Poly-lysine | 13 | 15 | 0.47 | 52 | |

|

| |||||

| * Dendrimers | Gadomer-17 | 13 | 1.5 | 35 | |

|

| |||||

| * Liposome | ACPL | 12 | 11 | 1.5 | >103 |

|

| |||||

| * Nanoparticle emulsion | Gd3+-perfluorocarbon nanoparticles | 34 | 50 | 1.5 | >103 |

The r1 and r2 of Gd3+-CA1.CD2 exhibited an inverse relationship with the magnetic field strength (Table 2). In contrast, the r1 and r2 of Gd3+-DPTA showed weak dependence on field strengths. The magnetic field strength dependent changes in relaxivity are consistent with our simulation results based on the rotational τR of the contrast agent (Fig. 1b). The results showed that the protein contrast agent offers much higher relaxivities for MRI contrast enhancement at clinical magnetic field strengths (1.5 – 3.0 T). Interestingly, the transverse relaxivity of the designed contrast agent is very high (i.g. >50 mM−1 s−1) at 9.4T compared to Gd3+-DTPA, making it appropriate as a T2 contrast agent (Table 2) at high fields. It should be pointed out that r2 of our protein-based contrast agent is smaller than the currently used r2 agents such as iron oxides.50 This property allows our contrast agents to fill an important gap between small Gd-chelators and iron oxide nanoparticles, extending the range of MRI applications both at clinically relevant field strength and possibly higher field strength.

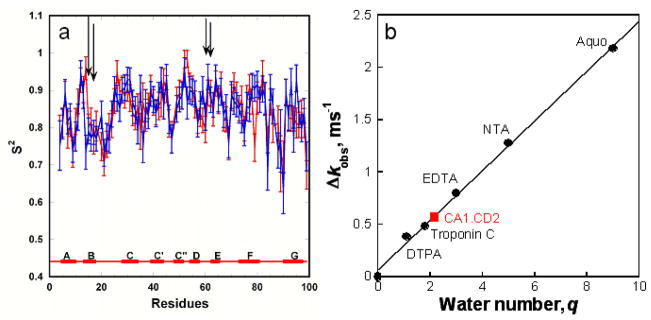

One key factor that contributes greatly to the relaxivity of an MRI contrast agent is its rotational correlation time, τR.11, 27, 28 Dynamic NMR studies showed that the overall correlation time of our designed protein (CA1.CD2) is similar in the absence (9.20 ns) and presence of bound metal ions (9.08 ns), consistent with that for proteins of similar size.51 The values of the order parameter S2 of the ligand residues are similar to the average value of the protein, suggesting that the metal binding pocket tumbles with the protein as a whole (Fig. 3a). Therefore, the measured correlation time of the protein directly reflects the τR of the metal binding site. In contrast, the flexible metal binding loop in CA9.CD2 has an S2 order value of 0.3–0.4 (unpublished data), which is very different from CA1.CD2 with an S2 value very close to that of the backbone of the protein.

Figure 3.

Dynamic properties and hydration water number of designed contrast agents. (a) S2 order values of the engineered metal binding protein. The positions of ligand residues are shown in vertical bars. Order parameters of CA1-CD2 with discontinuous ligand residues have the same dynamic properties as the scaffold protein. Arrows indicate the position of ligand residues. (b) Measurement of coordination water number by monitoring Tb3+ life time. Luminescence decay lifetime was obtained by fitting the acquired data in both H2O and D2O with a mono-exponential decay function. A standard curve correlating the Δkobs with water number (q) was established by using well-characterized chelators, such as EDTA (q=3), DTPA (q=1), NTA (q=5), and Aquo Tb3+ (q=9) solution with R2=0.997.38, 39 Water numbers coordinated to Tb3+-protein complexes were then obtained by fitting the acquired Δkobs value to the standard curve.

The hydration number of an MRI contrast agent is another important determinant for r1 and r2. The hydration number of the designed protein-based contrast agents was determined by measuring the luminescence lifetime of Tb3+.38 The free Tb3+ in H2O and D2O has lifetime values of 410 μs and 2,796 μs, respectively. The formation of Tb3+-protein complex in H2O significantly increases Tb3+ lifetime to 859 μs. The Tb3+ lifetime value of CA1.CD2 was 1,679 μs in D2O, suggesting a hydration number of 2.1 (Fig. 3b). Interestingly, a well-known Ca2+-binding protein troponin C exhibits a hydration number of 1.8 (Fig. 3b). It was determined by the X-ray crystal structure that troponin C has only one water molecule coordinated Tb3+ in the metal binding pocket.52 The effect of second and outer-sphere oscillators on hydration number is further indicated with a revised equation 39 in which the effect of second and outer-sphere oscillators on hydration number results in increased hydrogen numbers 2.5 and 3.0 for troponin C and CA1.CD2, respectively. Therefore, it is conceivable that the hydration water molecules either from the coordination shell or the outer shell of the protein also contribute to the observed high relaxivity of CA1.CD2.

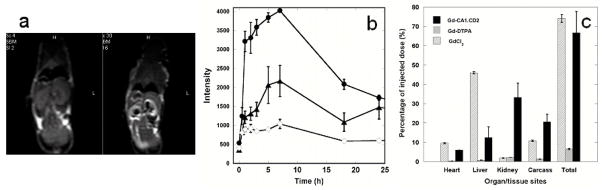

Contrast Enhanced MR Imaging of Mice

The effect of MRI contrast enhancement of the protein contrast agent was tested in mice (CD-1 mice). Gd3+-CA1.CD2 was administered via tail vein at a dose of ~ 2.4 μmole Gd3+ per kilogram of body weight, about 35-fold lower than the dosage of Gd3+-DTPA used in diagnostic imaging. Comparison of pre- and post-contrast T1 weighted spin echo images obtained at 3T showed the contrast enhancement in several organs with the greatest enhancement of the MRI contrast observed in the kidney (Fig. 4a, arrows indicated), which exhibited a time dependent change of the contrast enhancement over a period of 2 hours (Fig. 4b). Quantitative analysis of image data showed the distribution of the contrast enhancement at different organs (Fig. 4b). The tissue dependent enhancement is consistent with the biodistribution of Gd3+ analyzed at 1 hour time point using ICP-MS (Fig. 4c). The T1 contrast enhancement in the kidney cortex diminished substantially at 18 hours after the administration of Gd3+-CA1.CD2, suggesting that the agent was gradually cleared from the kidney and other organs. Consistent with the simulations and relaxivity values determined in vitro, a strong T2 contrast enhancement was observed at 9.4T. T2-weighted images at 9.4T, and T1-weighted images at 3T showed very similar tissue and organ distribution patterns (Supplementary Fig. S3). Conversely, Gd3+-DTPA at the same concentration failed to exhibit contrast enhancements at either 3T or 9.4T.

Figure 4.

In vivo MR images and biodistribution of designed contrast agents. (a) MR images of mouse (26 g) pre-(left) and 40 minutes post-(right) injection of 50 μL of 1.2 mM Gd3+-CA1.CD2 through the tail vein. The MRI was performed using a spin echo sequence with TE/TR = 15 ms/500 ms using a 3T scanner. The arrows indicate the contrast enhancements at different organ sites. (b) The MRI signal intensity changes at kidney (●), liver (▲), and muscle (◇) as a function of time. The 0 refers to the pre-injection. (c) Tissue distributions 1 hour post-intravenous injection of Gd3+-CA1.CD2 (3.0 μmole/kg, solid black), Gd3+-DTPA (150 μmole/kg, grey), and GdCl3 (100 μmole/kg, open). The Gd3+ in tissues was measured by ICP-MS and was calculated and expressed as a percentage of the injected dose.53 The Gd3+ retained in the animal carcass (i.e. - the remainder of the whole body after removing indicated organs) is calculated as the mean from 10 randomly-selected sites. Error bars in (a), (b), and (c) are standard deviations of four measurements or four animals (n=4).

Furthermore, contrast enhancement by Gd3+-CA1.CD2 was sustained over 4–7 hours at multiple organs (Fig. 4b), indicating much longer tissue retention time of Gd3+-CA1.CD2 than that of Gd3+-DTPA. The tissue retention and blood circulation times of Gd3+-CA1.CD2 in mice were characterized by administering various doses of agents in mice and analyzing the collected blood samples or tissue sections from sacrificed animals using immunoblots and ELISA with monoclonal (OX45) and in-house developed polyclonal (PabCD2) antibodies. In contrast to the short blood circulation time of Gd3+-DPTA, Gd3+-CA1.CD2 exhibited a prolonged blood circulation time. No significant decrease in the CA1.CD2 levels in blood was observed until 45 minutes after IV administration. The protein remained in blood circulation for more than 3 hours (Supplementary Fig. S4a). This property is important for imaging of biological events that require prolonged imaging time, or imaging of pathological features that require time for delivery of the agent to the targeted site. In the kidney, CA1.CD2 was first detectable at 15 minutes and peaked at 4–5 hours. There was less than 10% of the injected dose of the contrast agent remaining in the kidney 15 hours after injection (by measurements of both Gd3+ and CA1.CD2). This result, along with the observation of MRI contrast changes in the bladder, suggests a clearance of the agent by kidney.

Gd3+-CA1.CD2 did not exhibit acute toxicity at the dose (~2.4 μmole/kg) used for MRI. All mice that received the contrast agents (>10) showed no adverse effects before euthanization five days after agent injection. The effects of Gd3+-CA1.CD2 on liver enzymes (ALT, ALP, AST), serum urea nitrogen, bilirubin, and total protein from CD-1 mice 48 hours post-contrast injection were negligible compared to those in the control mice (Table S1). In addition, no cytotoxicity was observed in tested cell lines, SW620, SW480 and HEK293 that were treated with 50 μM Gd3+-CA1.CD2, by MTT assay (Supplementary Fig. S4b). Based on the preliminary characterization of toxicity, we conclude that the protein contrast agent did not exhibit acute toxicity at current dosages for mice.

4. Discussion

While new developments of Gd3+ chelators4, 5, 11, 21, 54 continue to expand the applications of small molecular contrast agents, macro-molecular agents are increasingly attractive for functional and molecular imaging applications. A common approach of using small molecular Gd3+-DTPA to bind albumin in serum (e.g., MS-325) has the capability to enhance the relaxivity in vivo. However, this class of contrast agents is currently limited to imaging the vascular system55–58 with its complex pharmacokinetics.59 Conjugation or encapsulation of small Gd3+-chelators to or in liposome, fullerene and nanotubes indeed resulted in increases in relaxivity; however, several important drawbacks limit the applications of these agents. Our approach of using an engineered protein to chelate the Gd3+ for contrast enhancing effects differs fundamentally from those previous studies in several respects. First, we have created a Gd3+-binding site with strong metal selectivity in a stable and potentially fully functioning host protein by de novo design. This is significantly different from using a small peptide fragment to cross-link a small Gd3+-chelate for enhanced stability and rigidity of the binding site as well as biological function of the biomolecule matrix. To our knowledge, this is the first example where a protein-based MRI contrast agent was developed using an engineered Gd3+ binding protein without using existing small metal chelators. This is an important achievement in protein design, involving the rational development of a metalloprotein with high coordination number and charged ligand residues in the coordination shell. Second, our approach provides a new platform for developing by protein engineering high-performance MRI contrast agents with further improved relaxivity and metal selectivity and stability. Our studies reveal that three factors are key in achieving high relaxivity: 1) longer rotational correlation time τR of the designed agents, 2) direct coordination of Gd3+ ions to amino acid ligands from the rigid protein matrix to eliminate internal mobility, and 3) increased number of hydration water molecules. As predicted by the Solomon-Bloembergen-Morgan equation (Supplementary Equation 1), relaxivities can be significantly increased by increasing the number of hydration water molecules. Unfortunately, previous attempts to increase relaxivities by increasing the number of coordinating water molecules > 1 for BTPA and DTPA-BMA did not yield expected results. Our studies demonstrated that it is possible to increase relaxivity by increasing the hydration number of a protein MRI contrast agent without sacrificing metal binding properties, such as affinity and metal specificity. Although the Gd/Zn selectivity for our developed CA1.CD2 is better than for Gd3+-DTPA-BMA as shown in Table 1, further improvement in the kinetic stability and metal selectivity may be necessary to prevent the risk of clinical problems such as Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) related to the kinetically-controlled in vivo release of Gd3+ from the chelate complex with increased tissue retention time. Presumably, the concept demonstrated in this study may be applied to the design of other macromolecule-based MRI contrast agents. Using a protein to chelate Gd3+ as an MRI contrast agent has several potential advantages over Gd3+-DTPA in functional and molecular imaging applications: 1) it greatly increases the contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR); 2) it improves dose efficiency with reduced metal toxicity; 3) it prolongs the tissue retention time, which enables imaging of an abnormality that requires prolonged tissue enhancement; and 4) it provides a potential functioning protein or a protein carrier that can conjugate target-specific ligands to a biomarker for targeted molecular MR imaging. Despite the fact that the diffusion rate of protein with proper size (3–5 nm) is slower than that of small chelators, limiting its capability to diffuse to the target, we expect to develop and investigate biomarker targeted molecular imaging in the immediate future with our protein-based contrast agents since the affinity and specificity of molecular recognition is largely dependent upon the proper balance between the on and off rates. Although immunogenicity is a concern when using a protein as a matrix of Gd3+ carrier, we expect that such limitations may be overcome by improved design of protein carrier and the success of protein drugs.60

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dan Adams, April Ellis, and Michael Kirberger, Leland Chung, Delon Barfuss, Jim Prestegard for their critical review of this manuscript and helpful discussions, Siming Wang for Mass spectrometry analysis, Dirck Dillehay for assistance with toxicity analysis, Xiaoxia Wang, PA van der Merwe for CD2 monoclonal antibody, Xianghong, and Lily Yang for the help with animal and MRI, Hsiau-Wei Lee for the dynamic study, Lisa Jones, and David Mpofu for engineered proteins, Jina Qiao for biodistribution study and the other members of the Yang and Liu research groups for their helpful discussions. This work is supported in part by the following sponsors: NIH EB007268 and NIH GM 62999 and ELSA U Pardee Foundation to J. J. Yang, and NIH GM 063874, NIH CA120181and Georgia Cancer Coalition distinguished cancer scholar award to ZRL, and NIH Predoctoral Fellowships to ALW.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: ESI-MS of metal:protein complex, determination of metal binding constants, MRI imaging and its data analysis, tissue retention and blood circulation time of contrast agents, toxicity, and simulation of contrast agent relaxivities. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Tyszka JM, Fraser SE, Jacobs RE. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2005;16(1):93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lippard SJ. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2(10):504–507. doi: 10.1038/nchembio1006-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Louie AY, Huber MM, Ahrens ET, Rothbacher U, Moats R, Jacobs RE, Fraser SE, Meade TJ. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18(3):321–325. doi: 10.1038/73780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frangioni JV. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24(8):909–913. doi: 10.1038/nbt0806-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woods M, Woessner DE, Sherry AD. Chem Soc Rev. 2006;35(6):500–511. doi: 10.1039/b509907m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lauffer RB. Chem Rev. 1987;87:901–927. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aime S, Barge A, Cabella C, Crich SG, Gianolio E. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2004;5(6):509–518. doi: 10.2174/1389201043376580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toth E, Helm L, Merbach AE. In: Contrast Agents I: Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Krause W, editor. Vol. 221. 2002. pp. 61–102. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merbach AE, Toth E. The chemistry of contrast agent agents in medical magnetic resonance Imaging. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geraldes CF, Sherry AD, Cacheris WP, Kuan KT, Brown RD, 3rd, Koenig SH, Spiller M. Magn Reson Med. 1988;8(2):191–199. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910080209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caravan P. Chem Soc Rev. 2006;35(6):512–523. doi: 10.1039/b510982p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinmann HJ, Press WR, Gries H. Invest Radiol. 1990;25(Suppl 1):S49–50. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199009001-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Opsahl LR, Uzgiris EE, Vera DR. Acad Radiol. 1995;2(9):762–767. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(05)80486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langereis S, de Lussanet QG, van Genderen MH, Meijer EW, Beets-Tan RG, Griffioen AW, van Engelshoven JM, Backes WH. NMR Biomed. 2006;19(1):133–141. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bryant LH, Jr, Brechbiel MW, Wu C, Bulte JW, Herynek V, Frank JA. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;9(2):348–352. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199902)9:2<348::aid-jmri30>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sirlin CB, Vera DR, Corbeil JA, Caballero MB, Buxton RB, Mattrey RF. Acad Radiol. 2004;11(12):1361–1369. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lanza GM, Winter P, Caruthers S, Schmeider A, Crowder K, Morawski A, Zhang H, Scott MJ, Wickline SA. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2004;5(6):495–507. doi: 10.2174/1389201043376544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karfeld LS, Bull SR, Davis NE, Meade TJ, Barron AE. Bioconjug Chem. 2007;18(6):1697–1700. doi: 10.1021/bc700149u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gillies RJ. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 2002;39:231–238. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Artemov D, Bhujwalla ZM, Bulte JW. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2004;5(6):485–494. doi: 10.2174/1389201043376553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aime S, Cabella C, Colombatto S, Geninatti Crich S, Gianolio E, Maggioni F. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;16(4):394–406. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson EA, Isaacman S, Peabody DS, Wang EY, Canary JW, Kirshenbaum K. Nano Lett. 2006;6(6):1160–1164. doi: 10.1021/nl060378g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strijkers GJ, Mulder WJ, van Heeswijk RB, Frederik PM, Bomans P, Magusin PC, Nicolay K. MAGMA. 2005;18(4):186–192. doi: 10.1007/s10334-005-0111-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caravan P, Greenwood JM, Welch JT, Franklin SJ. Chem Commun (Camb) 2003;(20):2574–2575. doi: 10.1039/b307817e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim Y, Welch JT, Lindstrom KM, Franklin SJ. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2001;6(2):173–181. doi: 10.1007/s007750000188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilkins AL, Yang W, Yang JJ. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2003;4(5):367–373. doi: 10.2174/1389203033487063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang W, Wilkins AL, Li S, Ye Y, Yang JJ. Biochemistry. 2005;44(23):8267–8273. doi: 10.1021/bi050463n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang W, Wilkins AL, Ye Y, Liu ZR, Li SY, Urbauer JL, Hellinga HW, Kearney A, van der Merwe PA, Yang JJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(7):2085–2093. doi: 10.1021/ja0431307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farrow NA, Muhandiram R, Singer AU, Pascal SM, Kay CM, Gish G, Shoelson SE, Pawson T, Forman-Kay JD, Kay LE. Biochemistry. 1994;33(19):5984–6003. doi: 10.1021/bi00185a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barbato G, Ikura M, Kay LE, Pastor RW, Bax A. Biochemistry. 1992;31(23):5269–5278. doi: 10.1021/bi00138a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nicholson LK, Kay LE, Baldisseri DM, Arango J, Young PE, Bax A, Torchia DA. Biochemistry. 1992;31(23):5253–5263. doi: 10.1021/bi00138a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang W, Jones LM, Isley L, Ye Y, Lee HW, Wilkins A, Liu ZR, Hellinga HW, Malchow R, Ghazi M, Yang JJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125(20):6165–6171. doi: 10.1021/ja034724x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akke M, Skelton NJ, Kordel J, Palmer AG, 3rd, Chazin WJ. Biochemistry. 1993;32(37):9832–9844. doi: 10.1021/bi00088a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kay LE, Keifer P, Saarinen T. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:10663–10665. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bendall MR. J Magn Reson, Ser A. 1995;116:46–58. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palmer AG, III, Rance M, Wright PE. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:4371–4380. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palmer AG., III Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2001;30:129–155. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.30.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sudnick DR, Horrocks WD., Jr Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;578(1):135–144. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(79)90121-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beeby A, Clarkson IM, Dickins RS, Faulkner S, Parker D, Royle L, de Sousa AS, Gareth Williams JA, Woods M. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1999;2:493–504. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martell AE, Simth RM, Motekaitis RJ. NIST Standard Reference Data. Gaithersburg; MD: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deng H, Chen G, Yang W, Yang JJ. Proteins. 2006;64(1):34–42. doi: 10.1002/prot.20973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang W, Lee HW, Hellinga H, Yang JJ. Proteins. 2002;47(3):344–356. doi: 10.1002/prot.10093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pidcock E, Moore GR. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2001;6(5–6):479–489. doi: 10.1007/s007750100214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maniccia AW, Yang W, Li SY, Johnson JA, Yang JJ. Biochemistry. 2006;45(18):5848–5856. doi: 10.1021/bi052508q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ye Y, Lee HW, Yang W, Shealy SJ, Wilkins AL, Liu ZR, Torshin I, Harrison R, Wohlhueter R, Yang JJ. Protein Eng. 2001;14(12):1001–1013. doi: 10.1093/protein/14.12.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ye Y, Lee HW, Yang W, Shealy S, Yang JJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(11):3743–3750. doi: 10.1021/ja042786x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wedeking P, Shukla R, Kouch YT, Nunn AD, Tweedle MF. Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;17(4):569–575. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(98)00203-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kumar K, Tweedle MF, Malley MF, Cougoutas JZ. Inorg Chem. 1995;34:6472–6480. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cacheris WP, Quay SC, Rocklage SM. Magn Reson Imaging. 1990;8(4):467–481. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(90)90055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bulte JW, Kraitchman DL. NMR Biomed. 2004;17(7):484–499. doi: 10.1002/nbm.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wyss DF, Dayie KT, Wagner G. Protein Sci. 1997;6(3):534–542. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rao ST, Satyshur KA, Greaser ML, Sundaralingam M. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1996;52(Pt 5):916–922. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996006166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barnhart JL, Kuhnert N, Bakan DA, Berk RN. Magn Reson Imaging. 1987;5(3):221–231. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(87)90023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Zijl PC, Jones CK, Ren J, Malloy CR, Sherry AD. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(11):4359–4364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700281104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lauffer RB, Parmelee DJ, Ouellet HS, Dolan RP, Sajiki H, Scott DM, Bernard PJ, Buchanan EM, Ong KY, Tyeklar Z, Midelfort KS, McMurry TJ, Walovitch RC. Acad Radiol. 1996;3(Suppl 2):S356–358. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(96)80583-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lauffer RB, Parmelee DJ, Dunham SU, Ouellet HS, Dolan RP, Witte S, McMurry TJ, Walovitch RC. Radiology. 1998;207(2):529–538. doi: 10.1148/radiology.207.2.9577506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parmelee DJ, Walovitch RC, Ouellet HS, Lauffer RB. Invest Radiol. 1997;32(12):741–747. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199712000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Allen MJ, Meade TJ. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2003;8(7):746–750. doi: 10.1007/s00775-003-0475-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brasch R, Turetschek K. Eur J Radiol. 2000;34(3):148–155. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(00)00195-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stockwin LH, Holmes S. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2003;3(7):1133–1152. doi: 10.1517/14712598.3.7.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.