Abstract

Background

Participation in physical activity is important for childhood cancer survivors because inactivity may compound cancer/treatment-related late-effects. However, some survivors may have difficulty participating physical activity and these individuals need to be identified so that risk-based guidelines for physical activity, tailored to specific needs, can be developed and implemented.

Purpose

To document physical activity patterns in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) cohort, compare physical activity patterns to siblings in CCSS and a population based sample from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, and evaluate associations between diagnosis, treatment, and personal factors and risk for inactive lifestyle.

Methods

Percentages of participation in recommended physical activity were compared among survivors, siblings and population norms. Generalized linear models were used to evaluate associations between cancer diagnosis and therapy, sociodemographics and risk for inactive lifestyle.

Results

Participants included 9301 adult survivors of childhood cancer and 2886 siblings. Survivors were less likely than siblings (46% vs. 52%) to meet physical activity guidelines and more likely than siblings to report inactive lifestyle (23% vs. 14%). Medulloblastoma (35%) and osteosarcoma (27%) survivors reported highest levels of inactive lifestyle. Treatments with cranial radiation or amputation was associated with an inactive lifestyle as were female gender, black race, older age, lower educational attainment, underweight or obese status, smoking, and depression.

Conclusion

Childhood cancer survivors are less active than a sibling comparison group or an age and gender-matched population sample. Survivors at risk for inactive lifestyle should be considered high priority for developing and testing of intervention approaches.

Keywords: Childhood Cancer, Physical Activity, Survivorship

INTRODUCTION

As the number of individuals who survive childhood cancer continues to increase, so does the need for long-term medical follow-up and interventions to address or prevent adverse late effects in this population. Both individualized medical follow-up for long-term survivors of childhood cancer, and adoption of a healthy lifestyle that includes physical activity, are encouraged by pediatric professional medical organizations, including the American Society of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, the International Society of Pediatric Oncology, and the American Academy of Pediatrics.1, 2

In the general population, physical activity decreases the risk of both all-cause mortality and mortality related to cardiovascular disease,3-8 and is inversely associated with the risk of developing breast,9, 10 endometrial,9 colon,11-13 and lung cancer.14, 15 Physical activity is also associated with a decreased risk of developing dyslipidemia and insulin resistance,16 osteoporosis,17-19 and cognitive decline.20, 21 An active lifestyle has demonstrated benefits even among those who have substantial functional loss.22-24 Some evidence exists to support the contention that a healthy lifestyle that includes an adequate amount of physical activity has the potential to prevent or attenuate many of the long-term problems experienced by childhood cancer survivors.25 Late-effects that have been associated with an inactive lifestyle include early mortality,26 cardiovascular disease,27 lipid abnormalities,28 osteoporosis,28 cognitive decline,29 and physical performance limitations.30

Because of the heterogeneous nature of histologies and treatments experienced by childhood cancer survivors, there is a need to provide a comprehensive documentation of specific risk factors for an inactive lifestyle in this population. Certain groups of cancer survivors may benefit from targeted interventions that address their unique limitations so they can modify their lifestyle choices. Others may have treatment related late effects amenable to existing programs designed to improve physical health, such as those that target obesity,31 diabetes,32, 33 or cardiovascular disease.34 This manuscript documents physical activity patterns in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) cohort, compares physical activity patterns between survivors and siblings and evaluates the association between diagnosis, treatment, and demographic/personal factors and risk for inactive lifestyle. For external validation of the use of the sibling comparison group, physical activity patterns among both siblings and survivors are compared to an age and gender-matched population reference group from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey. These analyses are designed to provide initial information for the eventual development of evidence-based, risk-based guidelines and interventions for physical activity promotion among long-term childhood cancer survivors.

METHODS

Sample

Details of the CCSS study have been published elsewhere.35 Briefly, eligible participants were 5+ year cancer survivors, diagnosed between 1970 and 1986 when younger than 21 years of age at one of twenty-six institutions. Eligible diagnoses included leukemia, Hodgkin disease and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, CNS malignancies, Wilms' tumor, neuroblastoma, soft tissue sarcoma, and bone tumors. Of the 20,346 eligible individuals, 14,357 survivors were successfully contacted and enrolled. A comparison group of 3899 siblings was also recruited and completed the same baseline questionnaire as that of the survivors in 1995-1996. Survivor and sibling participants who completed the 2003 follow-up questionnaire, had their treatment records abstracted, and who were 18 years of age or older in 2003 were eligible for these analyses. The entire set of study questionnaires and the medical record abstraction form can be found at www.stjude.org/ccss.

Outcome of interest

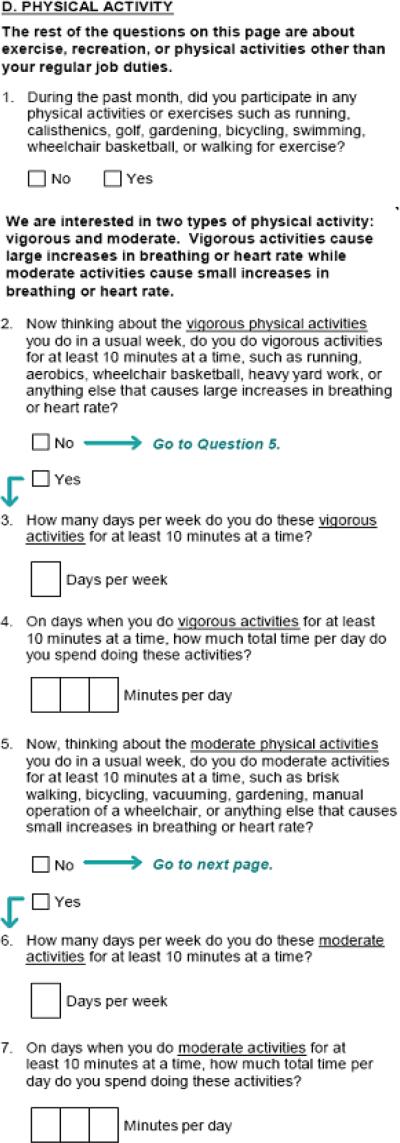

The primary outcome of interest for these analyses was activity status indicated on the 2003 CCSS Questionnaire. Based on participants' answers to six questions from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey (BRFSS)36 about physical activity, and one question about participation in physical activity over the past month (Figure 1), this outcome was summarized as: 1) a binary variable classifying the participant as either meeting or not meeting the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for physical activity (30 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity on 5 or more days of the week or 20 minutes of vigorous intensity physical activity on 3 or more days of the week),37 and 2) a binary variable classifying an inactive lifestyle if the participant indicated that they did not participate in any leisure-time physical activity over the past month. Additionally, a three-to-one population-based sample was selected, frequency matched on age and gender, from individuals who answered the same six questions on the 2003 BRFSS, to serve as a comparison group for both survivors and siblings.38

Figure 1.

Physical activity questions from the 2003 follow-up questionnaire.

Independent (explanatory) variables

Diagnosis and treatment variables were abstracted from the medical record and included: cancer diagnosis; age at diagnosis; surgery status classified as amputation, other surgery or none; chemotherapy classified as anthracyclines, other chemotherapy or none; and radiation classified as cranial radiation, chest radiation, other radiation or none. Demographic and personal factors for both survivors and for members of the sibling comparison group were obtained from the 2003 CCSS Questionnaire.

Explanatory variables from the 2003 CCSS Questionnaire included race, current age, highest level of educational attainment, employment status, annual household income, height and weight, smoking status, and depression. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing self-reported weight in kilograms by height in meters squared, and grouped as underweight (<18.5 kilograms per meter squared - kg/m2), normal weight (18.5-24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25-29.9 kg/m2), and obese (30+ kg/m2). Depression was assessed and classified according to the respondent's score on the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18).39 A T-score of 63 or higher was classified as depression.40

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic and personal factors and compared between survivors and siblings. The frequencies and percents of survivors and siblings who did not meet CDC guidelines for physical activity, and who reported an inactive lifestyle, were compared in separate multivariate models, adjusted for demographic and personal factors. The proportion of survivors within each cancer diagnosis by gender stratification who did not meet CDC guidelines for physical activity and who reported an inactive lifestyle were also compared to siblings in separate age adjusted models. All comparisons between survivors and siblings utilized relative risk regression models (generalized estimating equations) to account for potential intra-family correlation.41, 42 The impact of treatment variables on not meeting CDC guidelines for physical activity and for an inactive lifestyle were evaluated in analyses limited to survivors only, using generalized linear models (log-link and a binomial error term),43 stratifying by gender, and adjusting for age at questionnaire completion, and age at diagnosis.

The frequencies of survivors, siblings and the BRFSS sample who did not meet CDC guidelines for physical activity, and who reported an inactive lifestyle, were calculated and compared between survivors, overall and by diagnosis, and the BRFSS sample using Chi-squared statistics. Percentages were compared between siblings and the BRFSS sample in generalized linear regression models,43 adjusted for age and gender.

Data were evaluated to assure that the assumptions of each procedure were met prior to statistical testing. Results of multivariate analyses are reported as risk ratios with 99% confidence intervals. Although analyses were hypothesis driven, because of the large sample size and multiple comparisons conducted, confidence intervals are reported to one decimal place in the tables, adjusted to reflect a p-value cut-point of 0.001. SAS version 9.1 (Cary, North Carolina) was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

There were 9301 survivors and 2886 siblings who were 18 years of age or older when they completed 2003 CCSS Questionnaire. This represents 76% of living adult survivors and siblings who were eligible to participate in this survey. Non-participants included 2385 survivors and 458 siblings who either actively or passively declined participation and 905 survivors and 27 siblings lost to follow-up. Among both survivors and siblings who completed the 2003 CCSS Questionnaire, 12,139 answered the question about inactive lifestyle (99.6%) and 11,805 (96.9%) answered the questions about physical activity. Participant survivors did not differ from non-participant survivors by diagnosis or age at diagnosis. Participant survivors and siblings were older, more likely to be female and report their race as white than non-participant survivors or siblings (all p values < 0.001).

The characteristics of the cancer survivors and the sibling comparison group are shown in Table 1. Cancer survivors were more likely to be male and younger than age 40 years than siblings. Siblings were more likely to have graduated from college, to be working or caring for a home and family, and to have an annual household income greater than $20,000. Cancer survivors were more likely than siblings to be underweight, and to be never-smokers. Cancer survivors reported less exercise than siblings. Over half (52%) of cancer survivors, and slightly less than half (47%) of siblings, reported not meeting CDC guidelines for physical activity.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| Survivors (N=9301) N | % | Siblings (N=2886) N | % | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 4586 | 49.3 | 1548 | 53.6 | <.0001 |

| Male | 4715 | 50.7 | 1338 | 46.4 | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Black - non Hispanic | 332 | 3.6 | 59 | 2.0 | |

| White - non Hispanic | 8277 | 89.0 | 2499 | 86.6 | |

| Hispanic | 394 | 4.2 | 81 | 2.8 | <.0001 |

| Other | 262 | 2.8 | 75 | 5.4 | |

| Not indicated | 36 | 0.4 | 172 | 6.0 | |

| Age group (years) | |||||

| 18-29 | 3843 | 41.3 | 1011 | 35.0 | |

| 30-39 | 3868 | 41.6 | 1084 | 37.6 | <.0001 |

| 40-49 | 1503 | 16.2 | 682 | 23.6 | |

| 50+ | 87 | 0.9 | 109 | 3.8 | |

| Educational attainment | |||||

| < High school | 439 | 4.7 | 85 | 3.0 | |

| High School graduate | 4888 | 52.6 | 1356 | 47.0 | <.0001 |

| College graduate | 3874 | 41.7 | 1436 | 49.8 | |

| Not indicated | 100 | 1.1 | 9 | 0.3 | |

| Employment | |||||

| Working/caring for home or family | 7450 | 80.1 | 2628 | 91.1 | |

| Student | 504 | 5.4 | 124 | 4.3 | |

| Unemployed/looking for work | 429 | 4.6 | 68 | 2.4 | <.0001 |

| Unable to work | 717 | 7.7 | 37 | 1.3 | |

| Not indicated | 201 | 2.2 | 29 | 1.0 | |

| Annual household income | |||||

| < $20.000 | 1057 | 11.4 | 192 | 6.7 | |

| ≥ $20.000 | 6897 | 74.2 | 2401 | 83.2 | <.0001 |

| Not indicated | 1347 | 14.5 | 293 | 10.2 | |

| Body mass index | |||||

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 391 | 4.2 | 68 | 2.4 | |

| Normal weight (18.5-24.9 kg/m2) | 4020 | 43.2 | 1261 | 43.7 | |

| Over weight (25-29.9 kg/m2) | 2698 | 29.0 | 883 | 30.6 | <.0001 |

| Obese (30+ kg/m2) | 1828 | 19.7 | 587 | 20.3 | |

| Height and/or weight not indicated | 364 | 3.9 | 87 | 3.0 | |

| Depression status | |||||

| Yes | 870 | 9.4 | 211 | 7.3 | .0007 |

| No | 8431 | 90.7 | 2675 | 92.7 | |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Current | 1468 | 15.8 | 583 | 20.2 | |

| Ever | 1443 | 15.5 | 643 | 22.3 | <.0001 |

| Never | 6365 | 68.4 | 1659 | 57.4 | |

| Not indicated | 25 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.03 | |

| Meets Guidelines for Physical Activity | |||||

| Yes | 4146 | 44.6 | 1458 | 50.5 | |

| No | 4847 | 52.1 | 1354 | 46.9 | <.0001 |

| Not indicated | 308 | 3.3 | 74 | 2.6 | |

| Inactive lifestyle | |||||

| No | 7153 | 76.9 | 2472 | 85.7 | <.0001 |

| Yes | 2111 | 22.7 | 403 | 14.0 | |

| Not indicated | 37 | 0.4 | 11 | 0.4 |

From generalized estimating equations

The associations between cancer survivor status, specific demographic and lifestyle factors, and activity status are shown in Table 2. After adjusting for demographic and lifestyle factors, cancer survivors were 1.2 (99% confidence interval (CI) 1.1-1.3) times more likely to report not meeting CDC guidelines for physical activity, and 1.6 (99% CI 1.4-1.8) times more likely to report no physical activity during the previous month (inactive lifestyle) than siblings. In the same adjusted models, female gender, black race, older age, an inability to work, and either being underweight or obese were also positively associated with not meeting CDC guidelines for physical activity and with inactive lifestyle. Individuals with higher levels of education were less likely to report an inactive lifestyle than those who did not finish high school. Current smokers compared to never smokers, and persons whose BSI was ≥63 compared to those with a BSI score < 63 were more likely to report an inactive lifestyle.

Table 2.

Risk ratios and 99% confidence intervals (CI) describing the association between survivor status, sociodemographic indicators, and not meeting nationally recommended guidelines for physical activity or reporting no leisure time physical activity over the past month (inactive lifestyle)

| Did not meet physical activity guidelines (Total N=11805) | Inactive lifestyle (Total N=12139) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | %† | Risk Ratio* | 99% CI* | N | %† | Risk Ratio* | 99% CI* | |

| Participant group | ||||||||

| Siblings | 2812 | 48.2 | 1.0 | 2875 | 14.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Survivors | 8993 | 53.9 | 1.2 | 1.1-1.3 | 9264 | 22.8 | 1.6 | 1.4-1.8 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 5951 | 55.2 | 1.2 | 1.1-1.3 | 6027 | 21.5 | 1.2 | 1.1-1.3 |

| Male | 5854 | 49.8 | 1.0 | 6112 | 20.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White - non Hispanic | 10450 | 51.7 | 1.0 | 10731 | 20.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Black - non Hispanic | 367 | 68.7 | 1.2 | 1.2-1.3 | 389 | 35.0 | 1.7 | 1.3-2.2 |

| Hispanic | 459 | 56.9 | 1.1 | 1.0-1.2 | 474 | 24.3 | 1.1 | 0.9-1.5 |

| Other | 330 | 55.8 | 1.1 | 1.0-1.2 | 337 | 23.2 | 1.2 | 0.8-1.6 |

| Age group (years) | ||||||||

| 18-29 | 4700 | 49.3 | 1.0 | 18.2 | 1.0 | |||

| 30-39 | 4794 | 55.0 | 1.1 | 1.0-1.2 | 4842 | 22.6 | 1.5 | 1.3-1.7 |

| 40-49 | 2125 | 54.0 | 1.1 | 1.0-1.2 | 4935 | 21.9 | 1.5 | 1.3-1.8 |

| 50+ | 186 | 55.4 | 1.2 | 1.1-1.4 | 2169 | 22.3 | 2.0 | 1.4-3.0 |

| Educational attainment | ||||||||

| < High school | 493 | 61.3 | 1.0 | 520 | 36.0 | 1.0 | ||

| High School graduate | 5997 | 53.6 | 0.9 | 0.8-1.0 | 6227 | 24.6 | 0.8 | 0.6-1.0 |

| College graduate | 5213 | 50.1 | 0.9 | 0.8-1.1 | 5285 | 14.4 | 0.4 | 0.3-0.6 |

| Employment | ||||||||

| Working/caring for home or family | 9794 | 51.6 | 1.0 | 10042 | 18.9 | 1.0 | ||

| Student | 612 | 42.0 | 0.8 | 0.7-0.9 | 626 | 16.1 | 0.9 | 0.7-1.2 |

| Unemployed/looking for work | 479 | 56.2 | 1.0 | 0.9-1.2 | 494 | 27.1 | 1.3 | 1.0-1.6 |

| Unable to work | 712 | 73.2 | 1.2 | 1.1-1.3 | 750 | 43.5 | 2.1 | 1.7-2.5 |

| Annual household income | ||||||||

| < $20.000 | 1197 | 56.4 | 1.0 | 1240 | 29.5 | 1.0 | ||

| ≥ $20.000 | 9082 | 51.3 | 1.1 | 0.9-1.1 | 9272 | 18.6 | 0.8 | 0.7-0.9 |

| Body mass index | ||||||||

| Underweight | 441 | 60.8 | 1.2 | 1.1-1.3 | 457 | 27.1 | 1.5 | 1.2-1.9 |

| Normal weight | 5134 | 48.2 | 1.0 | 5265 | 17.9 | 1.0 | ||

| Over weight | 3476 | 51.1 | 1.1 | 1.0-1.2 | 3562 | 19.0 | 1.0 | 0.9-1.2 |

| Obese | 2342 | 61.6 | 1.2 | 1.1-1.3 | 2410 | 26.5 | 1.4 | 1.3-1.7 |

| Smoking status | ||||||||

| Current | 1965 | 54.2 | 1.0 | 0.9-1.1 | 2044 | 27.7 | 1.5 | 1.2-1.9 |

| Ever | 2033 | 50.3 | 0.9 | 0.8-1.0 | 2075 | 19.0 | 1.0 | 0.8-1.1 |

| Never | 7786 | 52.7 | 1.0 | 7996 | 19.4 | 1.0 | ||

| Depression at time of survey | ||||||||

| No | 10766 | 52.4 | 1.0 | 10790 | 20.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Yes | 1039 | 54.0 | 1.0 | 0.9-1.1 | 1271 | 27.0 | 1.4 | 1.2-1.7 |

From generalized estimating equations with a binomial distribution and a log link to allow for intra-family correlation

Row percent

Table 3 shows the associations between specific cancer diagnoses and activity status by gender. Among females, survivors of brain tumors and leukemia were the least likely to meet guidelines for physical activity. Among males, survivors of CNS tumors and osteosarcoma were the least likely to meet CDC physical activity guidelines. Both female and male survivors in every diagnostic category were more likely than siblings to report an inactive lifestyle. Amputation and cranial radiation were also associated with not meeting CDC physical activity guidelines and with an inactive lifestyle (Table 4).

Table 3.

Percent of survivors and siblings not meeting nationally recommended guidelines for physical activity or reporting no physical activity over the past month (inactive lifestyle)

| Did not meet physical activity guidelines (Total N=11805) | Inactive lifestyle (Total N=12139) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | %† | Risk Ratio* | 99% CI* | N | %† | Risk Ratio* | 99% CI* | |

| Female | ||||||||

| Siblings | 1511 | 49.7 | 1.0 | 1543 | 14.3 | 1.0 | ||

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 1333 | 58.1 | 1.2 | 1.1-1.3 | 1377 | 25.3 | 1.9 | 1.6-2.2 |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 127 | 58.3 | 1.2 | 1.0-1.4 | 131 | 19.1 | 1.4 | 1.0-2.0 |

| Other or unspecified leukemia | 83 | 56.6 | 1.2 | 1.0-1.4 | 87 | 25.3 | 1.9 | 1.3-2.8 |

| Astrocytoma | 355 | 61.4 | 1.3 | 1.1-1.4 | 371 | 26.2 | 1.9 | 1.6-2.4 |

| Medulloblastoma, PNET | 106 | 68.9 | 1.4 | 1.2-1.6 | 109 | 41.3 | 3.0 | 2.4-4.0 |

| Other CNS tumor | 74 | 55.4 | 1.2 | 0.9-1.4 | 77 | 31.2 | 2.3 | 1.6-3.2 |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 574 | 51.6 | 1.0 | 0.9-1.1 | 581 | 20.5 | 1.3 | 1.1-1.6 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 221 | 57.0 | 1.1 | 1.0-1.3 | 227 | 23.8 | 1.7 | 1.3-2.1 |

| Wilms' tumor (kidney tumors) | 472 | 54.0 | 1.1 | 1.0-1.3 | 482 | 20.3 | 1.6 | 1.3-2.0 |

| Neuroblastoma | 342 | 53.2 | 1.1 | 1.0-1.3 | 354 | 17.5 | 1.4 | 1.1-1.8 |

| Osteosarcoma/other bone tumor | 258 | 59.7 | 1.2 | 1.1-1.3 | 265 | 29.8 | 1.9 | 1.5-2.4 |

| Ewings sarcoma | 113 | 69.0 | 1.4 | 1.2-1.6 | 115 | 22.6 | 1.5 | 1.1-2.2 |

| Soft tissue sarcoma | 382 | 56.8 | 1.2 | 1.1-1.3 | 393 | 23.4 | 1.6 | 1.3-2.0 |

| Male | ||||||||

| Siblings | 1301 | 46.4 | 1.0 | 1332 | 13.7 | 1.0 | ||

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 1314 | 48.0 | 1.1 | 1.0-1.2 | 1357 | 20.7 | 1.6 | 1.3-1.9 |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 100 | 49.0 | 1.1 | 0.9-1.3 | 102 | 20.6 | 1.6 | 1.0-2.3 |

| Other or unspecified leukemia | 96 | 49.0 | 1.1 | 0.9-1.3 | 98 | 20.4 | 1.5 | 1.0-2.3 |

| Astrocytoma | 359 | 56.3 | 1.2 | 1.1-1.3 | 369 | 25.8 | 1.9 | 1.5-2.3 |

| Medulloblastoma, PNET | 131 | 64.1 | 1.4 | 1.2-1.6 | 139 | 30.2 | 2.3 | 1.7-3.0 |

| Other CNS tumor | 105 | 61.0 | 1.3 | 1.1-1.5 | 107 | 31.7 | 2.3 | 1.7-3.2 |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 579 | 47.5 | 1.0 | 0.9-1.1 | 597 | 19.4 | 1.3 | 1.1-1.7 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 459 | 53.2 | 1.1 | 1.0-1.3 | 473 | 22.6 | 1.6 | 1.3-2.0 |

| Wilms' tumor (kidney tumors) | 370 | 46.5 | 1.0 | 0.9-1.2 | 386 | 19.7 | 1.6 | 1.2-2.0 |

| Neuroblastoma | 260 | 50.8 | 1.1 | 1.0-1.3 | 266 | 18.8 | 1.5 | 1.1-2.0 |

| Osteosarcoma/other bone tumor | 251 | 57.4 | 1.2 | 1.1-1.3 | 258 | 23.3 | 1.6 | 1.2-2.1 |

| Ewings sarcoma | 119 | 49.6 | 1.0 | 0.9-1.3 | 120 | 19.2 | 1.3 | 0.9-2.0 |

| Soft tissue sarcoma | 410 | 50.7 | 1.1 | 1.0-1.2 | 423 | 22.5 | 1.6 | 1.3-2.0 |

From generalized estimating equations with a binomial distribution and a log link to allow for intra-family correlation, adjusted for age

Row percent

CNS=Central Nervous System, PNET=Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor

Table 4.

Percent of survivors not meeting nationally recommended guidelines for physical activity or reporting no physical activity over the past month (inactive lifestyle) by treatment

| Did not meet physical activity guidelines (Total N=8993) | Inactive lifestyle (Total N=9264) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | %† | Risk Ratio* | 99% CI* | N | %† | Risk Ratio* | 99% CI* | |

| Female | ||||||||

| Surgery | ||||||||

| Amputation of lower limb | 196 | 69.9 | 1.3 | 1.2-1.5 | 202 | 31.2 | 1.6 | 1.2-2.0 |

| Other surgery | 2842 | 56.6 | 1.1 | 1.0-1.2 | 2919 | 23.4 | 1.2 | 1.0-1.4 |

| No surgery | 1073 | 55.7 | 1.0 | 1100 | 22.2 | 1.0 | ||

| Not indicated | 329 | 58.4 | 348 | 29.0 | ||||

| Chemotherapy | ||||||||

| Chemotherapy including anthracyclines | 1545 | 58.8 | 1.1 | 1.0-1.2 | 1596 | 24.1 | 1.1 | 1.0-1.3 |

| Chemotherapy without anthracyclines | 1695 | 56.3 | 1.0 | 0.9-1.1 | 1731 | 23.5 | 1.1 | 1.0-1.3 |

| No chemotherapy | 877 | 55.1 | 1.0 | 900 | 22.4 | 1.0 | ||

| Not indicated | 323 | 59.1 | 342 | 28.7 | ||||

| Radiation € | ||||||||

| Any cranial radiation | 1227 | 62.4 | 1.2 | 1.1-1.3 | 1273 | 28.4 | 1.5 | 1.3-1.7 |

| Chest radiation without cranial radiation | 760 | 54.1 | 1.0 | 0.9-1.1 | 774 | 21.7 | 1.0 | 0.8-1.2 |

| Other radiation | 694 | 59.2 | 1.1 | 1.0-1.2 | 713 | 23.2 | 1.1 | 0.9-1.3 |

| No radiation | 1439 | 52.8 | 1.0 | 1470 | 20.3 | 1.0 | ||

| Not indicated | 320 | 59.1 | 339 | 28.6 | ||||

| Male | ||||||||

| Surgery | ||||||||

| Amputation of lower limb | 228 | 54.4 | 1.3 | 1.1-1.5 | 234 | 25.2 | 1.4 | 1.0-1.9 |

| Other surgery | 3339 | 50.6 | 1.1 | 1.0-1.2 | 3447 | 21.1 | 1.0 | 0.9-1.3 |

| No surgery | 543 | 45.3 | 1.0 | 558 | 20.3 | 1.0 | ||

| Not indicated | 443 | 56.4 | 456 | 26.5 | ||||

| Chemotherapy | ||||||||

| Chemotherapy including anthracyclines | 1693 | 49.8 | 1.0 | 0.9-1.1 | 1742 | 19.2 | 0.8 | 0.7-1.0 |

| Chemotherapy without anthracyclines | 1594 | 49.5 | 1.0 | 0.9-1.1 | 1659 | 21.8 | 0.9 | 0.8-1.1 |

| No chemotherapy | 830 | 52.1 | 1.0 | 845 | 24.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Not indicated | 436 | 56.7 | 449 | 27.0 | ||||

| Radiation € | ||||||||

| Any cranial radiation | 1297 | 54.5 | 1.2 | 1.1-1.3 | 1344 | 24.6 | 1.3 | 1.1-1.6 |

| Chest radiation without cranial radiation | 681 | 501 | 1.1 | 1.0-1.2 | 699 | 20.3 | 1.0 | 0.9-1.3 |

| Other radiation | 793 | 49.3 | 1.0 | 0.9-1.1 | 818 | 19.3 | 1.0 | 0.8-1.2 |

| No radiation | 1350 | 46.4 | 1.0 | 1389 | 19.3 | 1.0 | ||

| Not indicated | 432 | 56.7 | 445 | 27.2 | ||||

Row percent;

From generalized linear models with a binomial distribution and a log link. Adjusted for age at diagnosis and age at interview

These categories are not mutually exclusive

Figure 2 shows the proportion of individuals meeting CDC guidelines for physical activity, and the proportion of individuals who reported no leisure-time physical activity over the past month for survivors, siblings, and the BRFSS sample. Survivors were less likely to meet the CDC guidelines for physical activity than the BRFSS reference group, and siblings were less likely to report an inactive lifestyle than the BRFSS group.

Figure 2.

Percent not meeting CDC guidelines for physical activity, or reporting no leisure-time physical activity over the past month (inactive lifestyle) comparing survivors and siblings to an age and gender matched sample of the US population.

*Age matched sample

**Sibling, BRFSS comparisons from generalized linear models with a binomial distribution/log link, adjusted for age, gender.

DISCUSSION

This analysis of physical activity status among a large heterogeneous cohort of adult survivors of childhood cancer indicates that they are less active than either the siblings in the study or the general population of similar age and sex. While statistically significant, the percentage differences in individuals who do not meet CDC physical activity guidelines are probably not clinically meaningful. What is more important is that the prevalence of no activity over than past month is 60% higher among childhood cancer survivors when compared to siblings. Our results characterize the features of survivors who are in particular need of interventions that promote physical activity. These include survivors who are female, black, older, underweight or obese, as well as survivors of CNS or bone tumors, especially those who had cranial radiation or an amputation.

Our study population reports less physical activity than other groups of childhood cancer survivors, including adolescents and young adults,44-46 but more physical activity than a smaller group of childhood cancer survivors comprised of nearly half CNS tumor survivors.47 Keats et al.45 reported average participation in combined moderate and vigorous physical activities 5+ times per week, 36-42 minutes per time, among 51 adolescent survivors. CNS tumor survivors comprised 13%, and osteosarcoma survivors 8.5% of their cohort. Tercyak et al.46 reported adequate physical activity among 80% of 75 childhood cancer survivors 11-21 years of age. Just over half of these individuals were females; 52% were leukemia survivors. Finnegan et al.44 indicated that 81% of childhood cancer survivors, recruited via the internet, reported being physically active. These survivors were younger (18-37 years) than our cohort, and were mostly well educated, Caucasian, females. The proportions of CNS tumor (13% vs. 10%) and bone tumor (8% vs. 11%) survivors in our cohort were similar to the proportions in their study. A small group of adult survivors of childhood cancer in Queensland, Australia were less active, with only 36% reporting sufficient physical activity.47 This group of individuals included a greater percentage of CNS tumor survivors (43%) and more females (61%) than our study.

Our study is the first that we know of to report differences among percentages of individuals who met the nationally recommended guidelines for physical activity in a large heterogeneous cohort of cancer survivors, siblings and a population-based comparison group. Our study includes the all diagnoses in the CCSS cohort, and differs from a previous CCSS report where analyses were limited to survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).48 Our data analyses include data summarized by Florin et al.48 and confirm and extend the findings that female gender and cranial radiation are associated with inadequate physical activity. Our analyses also include siblings of cancer survivors, who report physical activity levels similar to the population based group from the BRFSS, dispelling the notion that siblings of cancer survivors who participate in research introduce either healthy or sick participant bias into the study design.49

The demographic and treatment related risk factors identified in our analyses are supported by other investigators who have demonstrated lower than expected levels of physical activity among adults who were treated for CNS malignancies and bone tumors during childhood, particularly among female survivors. Odame et al.50 reported reduced physical activity levels in a group of 25 survivors of childhood CNS tumor who were 5-29 years of age at evaluation, with scores on two different activity indices lower among those who received cranial radiation when compared to those who did not receive cranial radiation. Gerber et al.51 evaluated 30 survivors of pediatric sarcoma and found that 67% had activity levels below the 50th percentile for their age and gender. Problems were most pronounced among those with lower-extremity or trunk lesions, and among females.

Several study limitations should be considered in the interpretation of these results. First, physical activity was evaluated with self report data that could not be validated. However, over-or under-reporting of physical activity have been evaluated in one study that compared self-reported physical activity on the BRFSS survey to objective monitoring with motion sensors and a heart rate monitor.52 These authors found 80% agreement between the two methods of classifying individuals who did or did not meet the national recommendations for physical activity. Additionally, two of the personal/demographic variables in our model that influenced physical inactivity, obesity and employment status, were measured simultaneously with the physical activity outcomes. We therefore can not be sure of the direction of these associations. Participants may have an inactive lifestyle because they are obese or obese because they have an inactive lifestyle. Participants may have an inactive lifestyle because they are busy looking for a job, or unemployed and sedentary because disability prevents participation in either activity. Finally, these analyses include cancer survivors treated between 1970 and 1986. Because therapy has evolved in response to the documentation of medical late effects, fewer children are receiving cranial radiation or amputation as part of treatment. Not all of our results may be generalizable to children treated with more contemporary therapy. However, this information is applicable to the large cohort of young adult survivors of childhood cancer who were treated on earlier protocols, and to the groups of individuals who still receive chemotherapy that promote obesity, cranial radiation, and extensive lower extremity surgical procedures.

In summary, childhood cancer survivors are less likely than members of a sibling comparison group, or an age- and gender-matched group of BRFSS survey participants to meet the nationally recommended guidelines for physical activity. Female survivors, survivors with obesity or chronic disease, survivors who received cranial radiation and those whose treatment required extensive surgical intervention may benefit from targeted interventions that address unique barriers to participation in regular physical activity.

Financial Support

This work was supported by grant CA 55727 (L.L. Robison, Principal Investigator), National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, with additional support provided to St. Jude Children's Research Hospital by ALSAC.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute Late effects of treatment for childhood cancer (PDQ) Health Professional Version. www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/lateeffects. Accessed March 20, 2008. [PubMed]

- 2.Landier W, Bhatia S, Eshelman DA, et al. Development of risk-based guidelines for pediatric cancer survivors: the Children's Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines from the Children's Oncology Group Late Effects Committee and Nursing Discipline. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4979–4990. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee IM, Hsieh CC, Paffenbarger RS., Jr. Exercise intensity and longevity in men. The Harvard Alumni Health Study. Jama. 1995;273:1179–1184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leon AS, Connett J, Jacobs DR, Jr., Rauramaa R. Leisure-time physical activity levels and risk of coronary heart disease and death. The Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. JAMA. 1987;258:2388–2395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindsted KD, Tonstad S, Kuzma JW. Self-report of physical activity and patterns of mortality in Seventh-Day Adventist men. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44:355–364. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90074-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lissner L, Bengtsson C, Bjorkelund C, Wedel H. Physical activity levels and changes in relation to longevity. A prospective study of Swedish women. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:54–62. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paffenbarger RS, Jr., Hyde RT, Wing AL, Lee IM, Jung DL, Kampert JB. The association of changes in physical-activity level and other lifestyle characteristics with mortality among men. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:538–545. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302253280804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu S, Yarnell JW, Sweetnam PM, Murray L. What level of physical activity protects against premature cardiovascular death? The Caerphilly study. Heart. 2003;89:502–506. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.5.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown WJ, Burton NW, Rowan PJ. Updating the evidence on physical activity and health in women. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:404–411. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cerhan JR, Chiu BC, Wallace RB, et al. Physical activity, physical function, and the risk of breast cancer in a prospective study among elderly women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1998;53:M251–256. doi: 10.1093/gerona/53a.4.m251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larsson SC, Rutegard J, Bergkvist L, Wolk A. Physical activity, obesity, and risk of colon and rectal cancer in a cohort of Swedish men. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:2590–2597. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samad AK, Taylor RS, Marshall T, Chapman MA. A meta-analysis of the association of physical activity with reduced risk of colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:204–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chao A, Connell CJ, Jacobs EJ, et al. Amount, type, and timing of recreational physical activity in relation to colon and rectal cancer in older adults: the Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:2187–2195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tardon A, Lee WJ, Delgado-Rodriguez M, et al. Leisure-time physical activity and lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16:389–397. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-5026-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee IM, Sesso HD, Paffenbarger RS., Jr. Physical activity and risk of lung cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:620–625. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.4.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamburg NM, McMackin CJ, Huang AL, et al. Physical inactivity rapidly induces insulin resistance and microvascular dysfunction in healthy volunteers. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2650–2656. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.153288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolff I, van Croonenborg JJ, Kemper HC, Kostense PJ, Twisk JW. The effect of exercise training programs on bone mass: a meta-analysis of published controlled trials in pre- and postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 1999;9:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s001980050109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan BK, Marshall LM, Winters KM, Faulkner KA, Schwartz AV, Orwoll ES. Incident fall risk and physical activity and physical performance among older men: the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:696–703. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacInnis RJ, Cassar C, Nowson CA, et al. Determinants of bone density in 30- to 65-year-old women: a co-twin study. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:1650–1656. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.9.1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larson EB, Wang L, Bowen JD, et al. Exercise is associated with reduced risk for incident dementia among persons 65 years of age and older. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:73–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-2-200601170-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jedrziewski MK, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Physical Activity and Cognitive Health. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3:98–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berk DR, Hubert HB, Fries JF. Associations of changes in exercise level with subsequent disability among seniors: a 16-year longitudinal study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:97–102. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fielding RA, Katula J, Miller ME, et al. Activity adherence and physical function in older adults with functional limitations. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:1997–2004. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e318145348d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Physical activity among adults with a disability--United States, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:1021–1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clarke SA, Eiser C. Health behaviours in childhood cancer survivors: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:1373–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mertens AC, Yasui Y, Neglia JP, et al. Late mortality experience in five-year survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3163–3172. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.13.3163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shankar SM, Marina N, Hudson MM, et al. Monitoring for cardiovascular disease in survivors of childhood cancer: report from the Cardiovascular Disease Task Force of the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e387–396. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neville KA, Cohn RJ, Steinbeck KS, Johnston K, Walker JL. Hyperinsulinemia, impaired glucose tolerance, and diabetes mellitus in survivors of childhood cancer: prevalence and risk factors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4401–4407. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duffner PK. Long-term effects of radiation therapy on cognitive and endocrine function in children with leukemia and brain tumors. Neurologist. 2004;10:293–310. doi: 10.1097/01.nrl.0000144287.35993.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ness KK, Mertens AC, Hudson MM, et al. Limitations on physical performance and daily activities among long-term survivors of childhood cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:639–647. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-9-200511010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graffagnino CL, Falko JM, La Londe M, et al. Effect of a community-based weight management program on weight loss and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Obes Res. 2006;14:280–288. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schulz AJ, Zenk S, Odoms-Young A, et al. Healthy eating and exercising to reduce diabetes: exploring the potential of social determinants of health frameworks within the context of community-based participatory diabetes prevention. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:645–651. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.048256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norris SL, Zhang X, Avenell A, et al. Long-term non-pharmacologic weight loss interventions for adults with type 2 diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004095.pub2. CD004095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matson-Koffman DM, Brownstein JN, Neiner JA, Greaney ML. A site-specific literature review of policy and environmental interventions that promote physical activity and nutrition for cardiovascular health: what works? Am J Health Promot. 2005;19:167–193. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-19.3.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robison LL, Mertens AC, Boice JD, et al. Study design and cohort characteristics of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: a multi-institutional collaborative project. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;38:229–239. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire. http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/pdfques/2003brfss.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2008.

- 37.Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity and public health. A recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. JAMA. 1995;273:402–407. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.5.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13:595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Derogatis LR, Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) 18, Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual. NCS Pearson, Inc.; Minneapolis, MN: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liang K, Zeger S. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCullock C, Searle S. Generalized, Linear, and Mixed Models. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Wiley, NY: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allison PD. Logistic Regression Using the SAS System. SAS Institute; Cary, NC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Finnegan L, Wilkie DJ, Wilbur J, Campbell RT, Zong S, Katula S. Correlates of physical activity in young adult survivors of childhood cancers. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34:E60–69. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.E60-E69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keats MR, Culos-Reed SN, Courneya KS, McBride M. Understanding physical activity in adolescent cancer survivors: an application of the theory of planned behavior. Psychooncology. 2007;16:448–457. doi: 10.1002/pon.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tercyak KP, Donze JR, Prahlad S, Mosher RB, Shad AT. Multiple behavioral risk factors among adolescent survivors of childhood cancer in the Survivor Health and Resilience Education (SHARE) program. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;47:825–830. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reeves M, Eakin E, Lawler S, Demark-Wahnefried W. Health behaviours in survivors of childhood cancer. Aust Fam Physician. 2007;36:95–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Florin TA, Fryer GE, Miyoshi T, et al. Physical inactivity in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:1356–1363. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sterling TD, Weinkam JJ, Weinkam JL. The sick person effect. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43:141–151. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90177-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Odame I, Duckworth J, Talsma D, et al. Osteopenia, physical activity and health-related quality of life in survivors of brain tumors treated in childhood. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;46:357–362. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gerber LH, Hoffman K, Chaudhry U, et al. Functional outcomes and life satisfaction in long-term survivors of pediatric sarcomas. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:1611–1617. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.08.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Strath SJ, Bassett DR, Jr., Ham SA, Swartz AM. Assessment of physical activity by telephone interview versus objective monitoring. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:2112–2118. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000099091.38917.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]