Abstract

We present the case of a 70-year-old man who had a prostate adenocarcinoma that metastatized to a previously unknown cranial meningioma. Central nervous system (CNS) metastases are very uncommon in patients with prostate cancer, and metastases to pre-existing primary CNS tumours are even more uncommon. Rare events like this can cause diagnostic uncertainty, as shown by this case. This case is a reminder for clinicians to consider prostate metastases in patients with known prostate carcinoma and focal neurological symptoms.

Résumé

Nous décrivons le cas d'un homme de 70 ans présentant un adénocarcinome métastatique de la prostate secondaire à un méningiome intracrânien non diagnostiqué auparavant. Les métastases au niveau du SNC sont très rares chez les patients atteints de cancer de la prostate et les métastases sont encore plus rares dans le cas de tumeurs primitives pré-existantes au niveau du SNC. La rareté de ces cas peut soulever des incertitudes au niveau du diagnostic, comme nous le montrerons. Ce cas permet de rappeler aux cliniciens d'envisager la possibilité de métastases chez les patients atteints d'un carcinome prostatique confirmé et présentant des signes neurologiques focaux.

Case report

In the summer of 2006, a 68-year-old man presented with weakness, fatigue and right hip pain. Investigations revealed a serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level of 933 μg/L, a serum alkaline phosphatase level of 975 U/L and multiple sclerotic bone metastases. On digital rectal examination, he had a nodular, firm prostate involving both lobes. A diagnosis of metastatic prostate cancer was made. No prostate biopsy was obtained. In July 2006, he was started on androgen deprivation therapy with bicalutamide followed by goserelin. Bicalutamide was discontinued after 4 weeks. The patient’s serum PSA level reached a nadir in December 2006 at 0.23 μg/L with a suppressed testosterone level.

One year later, in July 2007, the patient’s serum PSA level started to rise to 11.48 μg/L, despite androgen deprivation therapy. He was asymptomatic and there were no changes in his management. In October 2007, his serum PSA level was 32.7 μg/L.

In January 2008, he presented to his local emergency department with a 2 to 3–week history of left-sided facial droop, left-sided weakness and subsequently slurred speech. He also reported having headaches for several weeks prior. Investigations included enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the brain. The CT scan (Fig. 1) revealed an 8.3-cm lobulated dural lesion in the right parietal area with significant mass effect and moderate midline shift to the left. A primary central nervous system (CNS) tumour was the provisional diagnosis. The patient was admitted to hospital and initially given dexamethasone 10 mg intravenously 4 times per day. He was assessed by the palliative care team and, given his condition at that time and the underlying diagnosis of hormone refractory prostate cancer (HRPC), it was decided he would receive best supportive care. He was discharged home 3 days later on dexamethasone 4 mg orally twice daily and followed up by the palliative care home team. The patient’s serum PSA level at that time was 60.8 μg/L.

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography scan showing an 8.3-cm right parietal dural lesion with midline shift.

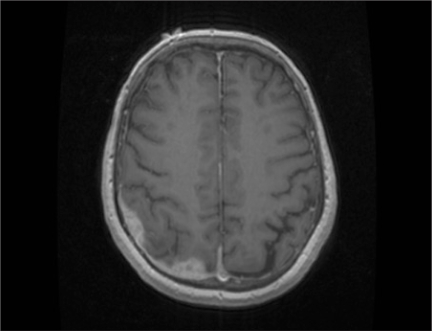

In March 2008, he had his regularly scheduled follow-up with his urologist. Given his marked clinical improvement, he was referred to a neurosurgeon for an opinion on the diagnosis and management. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen and pelvis at that time showed findings consistent with metastatic bone disease. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed marked decrease in the dural-based lesion (Fig. 2). Given the dramatic reduction in lesion size and the clinical response, presumably from steroids, it was felt that this was potentially a lymphoma. Interestingly, the serum PSA level at this time was 8.52 μg/L. A repeat bone scan showed variable changes, but new uptake of radiopharmaceutical at the right posterior pelvis and sacroiliac joint compared with July 2006. The patient underwent a right parietal craniotomy and subtotal resection of the tumour for tissue diagnosis. He was put on a tapering dose of steroids.

Fig. 2.

T1-weighted magnetic resonance image showing marked decrease in the parietal dural–based lesion following treatment with dexamethasone.

Pathology revealed 2 distinct neoplasms arising from the dura: meningothelial meningioma and metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. The meningioma was composed of cells disposed in meningothelial nests and whorls with rare psammoma bodies (Fig. 3). This tumour was infiltrated by irregular nests and cords of epithelial cells that stained positive for PSA (Fig. 4). The diagnosis of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma within a meningioma was made.

Fig. 3.

Hematoxylin–eosin stain showing both meningothelial meningioma and metastatic prostate carcinoma (original magnification × 200).

Fig. 4.

Prostate-specific antigen stain showing metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma cells (original magnification × 200).

Currently, the patient continues to take goserelin, as well as prednisone 5 mg twice daily. His CNS symptoms have resolved, but he continues to have mild discomfort in his low back on the right side. He was seen in consultation by radiation oncology and medical oncology. He is to receive localized radiotherapy to the residual dural-based mass, with delivery of 40 Gy in 15 fractions. He will be reassessed by medical oncology for consideration of subsequent systemic therapy.

Discussion

Metastatic hormone refractory prostate cancer most commonly metastasizes to bone and lymph nodes. When a CNS lesion is discovered in a patient with metastatic HRPC, one often considers a primary CNS lesion as opposed to metastatic prostate cancer. Primary CNS lesions can include a number of different diagnoses, including benign and malignant tumours. Meningiomas are the most common benign intracranial tumours and are composed of neoplastic arachnoidal cells arising in the dural coverings of the brain.1 They are often asymptomatic, slow-growing benign tumours and are often incidental findings on CT or MRI.

Central nervous system metastases from HRPC is rare, occurring in 0.63% of patients in one series and 0.2% of patients in another report.2,3 Dural CNS metastases from HRPC may also simulate meningiomas, as pointed out in some case reports.4–8

Our case illustrates a very unique situation in which both metastatic prostate cancer and a meningioma exist in the same lesion. The first reported case of metastatis of prostate cancer to a meningioma was by Doring in 1975.9 The diagnosis was made postmortem after a 75-year-old man with known metastatic prostate cancer presented with instability and falls. The patient died within 10 hours of his admission to hospital. Since that report, there have been 3 other case reports of prostate cancer metastasizing to an intracranial meningioma.10–12

In Doring’s original report, he summarized 16 previously published cases of extracranial cancers metastasizing to a meningioma.9 In most cases the primary cancers were lung, breast or kidney and in many patients, the diagnosis was made postmortem. Subsequent case reports and case series have shown that the metastasizing cancers are usually of the breast or lung, but, at times, a primary cancer diagnosis is not known beforehand.10,12 If a primary cancer diagnosis is known, the disease is almost always widely disseminated. In our patient, as in many of the other case reports, it is likely that the asymptomatic meningioma was present for a period and the presenting neurological symptoms were due to an increase in tumour bulk from a growing prostate cancer.

Given the paucity of case reports of this phenomenon of a primary cancer metastasizing to a meningioma, and given the frequency of both metastatic cancer and of meningiomas, one has to conclude that this is a very rare event. The metastatic spread is almost certainly hematogenous, and disruption of the blood–brain barrier by the meningioma may play a role in this occurrence.

Thus when a patient with metastatic prostate cancer presents with neurological symptoms, and imaging reveals a CNS tumour, one must consider a wide range of diagnoses and investigate appropriately. Better imaging techniques can help to differentiate between diagnoses, but they are still never 100% accurate. Initially, this patient was not investigated further because of his underlying metastatic prostate cancer.

This case also illustrates one other important reminder about metastatic HRPC: that some patients can have a profound clinical, biochemical and, in this case, radiological response to secondary hormonal manipulation. There are many different secondary hormonal manipulations, including reintroduction of a nonsteroidal antiandrogen, and cessation of nonsteroidal antiandrogen, corticosteroids, ketoconazole, estrogens and so forth. Prostate-specific antigen response rates vary from 10% to 60%; however, the lack of randomized clinical trials makes it impossible to draw conclusions on the true clinical benefit of secondary hormonal manipulation.13 In this case, corticosteroids made a profound positive difference in clinical outcome.

Conclusion

Prostate adenocarcinoma within a pre-existing meningioma is a rare event but should be considered in patients presenting with focal neurological symptoms and history of prostate carcinoma.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Competing interests: Dr. Wilke has received speaker honoraria from Novartis, and educational grants from sanofi-aventis, Abbott, Paladin Labs, Inc., and AstraZeneca.

References

- 1.Whittle IR, Smith C, Navoo P, et al. Meningiomas. Lancet. 2004;363:1535–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tremont-Lukats IW. Brain metastasis from prostate carcinoma: the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. Cancer. 2003;98:363–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lynes WL, Bostwick DG, Freiha FS, et al. Parenchymal brain metastases from adenocarcinoma of prostate. Urology. 1986;28:280–7. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(86)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyons MK, Drazkowski JF, Wong WW, et al. Metastatic prostate carcinoma mimicking meningioma: case report and review of the literature. Neurologist. 2006;12:48–52. doi: 10.1097/01.nrl.0000186809.04283.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lippman SM, Buzaid AC, Iacono RP, et al. Cranial metastases from prostate cancer simulating meningioma: report of two cases and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1986;19:820–3. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198611000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tagle P, Villanueva P, Torrealba G, et al. Intracranial metastasis of meningioma? An uncommon clinical diagnostic dilemma. Surg Neurol. 2002;58:241–5. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(02)00831-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirkwood JR, Margolis MT, Newton TH. Prostatic metastasis to the base of the skull simulating meningioma en plaque. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1971;112:774–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.112.4.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fink LH. Metastasis of prostatic adenocarcinoma simulating a falx meningioma. Surg Neurol. 1979;12:253–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doring L. Metastasis of carcinoma of prostate to meningioma. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1975;366:87–91. doi: 10.1007/BF00438681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chambers PW, Davis RL, Blanding JD, et al. Metastases to primary intracranial meningiomas and neuilemomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1980;104:350–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cluroe AD. Metastasis to meningioma: clues and investigation. Pathology. 2006;38:76–8. doi: 10.1080/00313020500468855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernstein RA, Grumet KA, Wetzel N. Metastasis of prostatic carcinoma to intracranial meningioma. J Neurosurg. 1983;58:774–7. doi: 10.3171/jns.1983.58.5.0774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawson NA. Second line hormone therapy for metastatic prostate cancer. 2008;1 UpToDate Version 16. [Google Scholar]