Abstract

Major advances in cancer control depend upon early detection, early diagnosis and efficacious treatment modalities. Current existing markers of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, generally incurable by available treatment modalities, are inadequate for early diagnosis or for distinguishing between pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis. We have used a proteomic approach to identify proteins that are differentially expressed in sera from pancreatic cancer patients, as compared to control. Normal, chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer serum samples were depleted of high molecular weight proteins by acetonitrile precipitation. Each sample was separated by chromatofocusing, and then further resolved by reversed-phase (RP)-HPLC. Effluent from the RP-HPLC column was split into two streams with one directly interfaced to an electrospray time-of-flight (ESI-TOF) mass spectrometer for MW determination of the intact proteins. The remainder went through a UV detector with the corresponding peaks collected with a fraction collector, subsequently used for MS/MS analysis. The ion intensities of proteins with the same MW obtained from ESI-TOF-MS analysis were compared, with the differentially expressed proteins determined. An 8915 Da protein was found to be up-regulated while a 9422 Da protein was down-regulated in the pancreatic cancer sera. Both proteins were identified by MS and MS/MS as proapolipoprotein C-II and apolipoprotein C-III1, respectively. The MS/MS data of proapolipoprotein C-II was searched using “semi-trypsin” as the search enzyme, thus confirming that the protein at 8915 Da was proapolipoprotein C-II. In order to confirm the identity of the protein at 9422 Da, we initially identified a protein of 8765 Da with a similar mass spectral pattern. Based on MS and MS/MS, its intact molecular weight and “semi-trypsin” database search, the protein at 8765 Da was identified as apolipoprotein C-III0. The MS and MS/MS data of the proteins at 8765 Da and 9422 Da were similar, thus confirming the protein at 9422 Da as being apolipoprotein C-III1. The detection of differentially-expressed proapolipoprotein C-II and apolipoprotein C-III1 in the sera of pancreatic cancer patients may have utility for detection of this deadly malignancy.

Keywords: accurate sequence identification, serum proteins, apolipoprotein C-II, apolipoprotein C-III, pancreatic cancer, glycoprotein

1. Introduction

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is one of the most deadly human malignancies, with an overall 5- year survival rate of less than 4%. An estimated 30 300 new cases were diagnosed in the USA in 2005, with an equivalent number of cancer-related deaths, making it the fourth leading cause of cancer death in both men and women in the USA (1). Early diagnosis and treatment is critical for improving survival rates in pancreatic cancer. An accurate serum-based approach may have utility for pancreatic cancer detection. However, existing markers are inadequate for early detection or for distinguishing between pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis.

Candidate markers of cancer and other diseases may be identified as circulating proteins in serum. However, the presence of high-abundance proteins, where 22 proteins (and their protein isoforms) account for 99% of the total protein content of serum, greatly complicates the separation and analysis of the protein content of serum (2). A number of different methods have been developed for the removal of high abundance serum proteins. In particular, the use of affinity columns, including a Protein A/G column, antibody columns or a mixture of different antibodies, have shown utility for depletion of albumin and other abundant proteins (3). Alternatively, chicken IgY has been used to deplete proteins from serum (4–7). However, a major drawback of these immunoaffinity methods is that they usually have low capacity. Thus, as only a small amount of serum can be immunodepleted, only a limited amount of sample is available for further analysis. Of even greater concern is that the high abundance proteins, such as albumin, can bind low abundance proteins that may be important markers and remove them from the serum (8–9). Importantly, intact low molecular weight proteins, or peptide fragments, in serum may have utility as candidate markers for cancer detection (8).

Acetonitrile precipitation, for preferential depletion of high molecular weight proteins, has been applied to serum samples. Acetonitrile decreases the binding of low molecular weight proteins to the carrier proteins. Moreover, this methodology mitigates possible loss of protein due to membrane adsorption as no membrane is used. Alpert et al (10) used this method in conjunction with size exclusion chromatography to separate serum and found it effectively eliminated high molecular weight proteins. Merrell et al (11) further modified the acetonitrile precipitation method by using slow-precipitation and found good reproducibility, with better depletion.

Due to the high complexity of serum, multidimensional separation methodology is required for analysis of the protein content. Liquid-based multidimensional protein fractionation facilitates the interrogation of distinct protein-containing fractions by a variety of techniques and, importantly, allows for increased protein load, thereby facilitating identification of the lower abundance proteins. To this end, we have introduced a multi-dimensional liquid-based methodology that separates complex mixtures of proteins in the first dimension by chromatofocusing and in the second dimension by nonporous silica (NPS) RP-HPLC (12–13), which resolves proteins according to their hydrophobicity.

Proteins and/or peptides often co-elute in complex biological samples, thus necessitating methodologies with high sensitivity/precision to confirm the actual identity of the protein. We have utilized information obtained from additional MS and MS/MS analysis, combined with precise molecular weight measurements, for the accurate identification of proteins. This methodology was employed to analyze differentially expressed proteins between sera from pancreatic cancer patients as compared to non-cancer (normal and chronic pancreatitis) controls. Two proteins were identified as being differentially expressed, with the concentration of the protein at 8915 Da, identified as proapolipoprotein C-II, found to be increased and the concentration of the protein at 9422 Da, identified as apolipoprotein C-III1, decreased in pancreatic cancer serum samples as compared to controls. This methodology may have utility to identify novel markers of cancer.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. High molecular weight protein depletion of sera

Serum purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) was used as a standard for the optimization of the methodology. Serum was divided into aliquots of 1 mL, and then stored at −80°C until use. The depletion of high molecular weight proteins was carried out by acetonitrile precipitation. 800 μL sera were divided into four 200 μL aliquots. For the fast-precipitation method, each aliquot was mixed with 200 μL acetonitrile directly to precipitate the high molecular proteins. For the slow-precipitation method, 10 μL acetonitrile was added to the 200 μL serum aliquot each time and vortexed; this procedure was repeated 20 times. Following precipitation, the samples were centrifuged, the supernatants transferred to new tubes and the samples concentrated to ~50 μL with a CentriVap concentrator (Labconco, Kansas City, MO, USA). The samples were further diluted with water to a final volume of 550 μL. 10 μL non-immunodepleted serum was also diluted by adding 0.5 mL water. Serum depletion was performed in duplicate, with the depletion of high molecular weight proteins verified by RP-HPLC.

2.2. Serum

Patients’ serum was obtained at the time of diagnosis following informed consent using IRB-approved guidelines. Three serum samples were obtained from patients with a confirmed diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma who were seen in the Multidisciplinary Pancreatic Tumor Clinic at the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center. Sera from the pancreatic cancer patients were randomly selected from a clinic population that sees, on average, at the time of initial diagnosis, 15% of pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients presenting with early stage (i.e., stage 1/2) disease and 85% presenting with advanced stage (i.e., stage 3/4). Inclusion criteria for the study included patients with a confirmed diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, the ability to provide written, informed consent, and the ability to provide 40 ml of blood. Exclusion criteria included inability to provide informed consent, patient’s actively undergoing chemotherapy or radiation therapy for pancreatic cancer, and patient’s with other malignancies diagnosed or treated within the last 5 years. Sera were also obtained from 3 patients with chronic pancreatitis who were seen in the Gastroenterology Clinic at University of Michigan Medical Center, and from 3 control healthy individuals collected at University of Michigan under the auspices of the Early Detection Research Network (EDRN). The mean age of the tumor group was 65.4 years (range 54–74 years) and from the chronic pancreatitis group was 54 years (range 45–65). The sera from the normal subject group was age and sex-matched to the tumor group. All of the chronic pancreatitis sera were collected in an elective setting in the clinic in the absence of an acute flare. All sera were processed using identical procedures. The samples were permitted to sit at room temperature for a minimum of 30 min (and a maximum of 60 min) to allow the clot to form in the red top tubes, and then centrifuged at 1300 g at 4°C for 20 min. The serum was removed, transferred to a polypropylene, capped tube in 1 ml aliquots, and frozen. The frozen samples were stored at −70°C until assayed. All serum samples were labeled with a unique identifier to protect the confidentiality of the patient. None of the samples were thawed more than twice before analysis.

After protocol optimization, three each of normal, chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer serum samples were depleted using the slow-precipitation method described above. Following depletion, the samples were subjected to less than three freeze-thaw cycles prior to analysis. 800 μL samples were divided into four 200 μL aliquots and depleted with the slow-precipitation method independently. The supernatants of each sample were recombined and concentrated to about 50 μL with a CentriVap concentrator (Labconco).

2.3. Chromatofocusing separation of depleted serum

The depleted serum samples were separated by chromatofocusing using a CF column (Beckman-Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA) with an HPLC system assembled in-house. The HPLC system consisted of a Series 200 LC pump (Perkin-Elmer, Wellesley, MA, USA), a six-port injection valve (Valco, Houston, TX, USA) with a 2.5 mL sample loop, a flow-through electrode (Lazar Research, Los Angeles, CA, USA) and a Spectra 100 UV detector (Thermo Separation Products, Reviera Beach, FL, USA). The start buffer, containing 6 M urea (Sigma) and 25 mM Bis-Tris (Sigma), was adjusted to pH 7.1 with saturated iminodiacetic acid (Sigma). The elution buffer, containing 6M urea and 1/10 volume Polybuffer 74 (GE Healthcare), was adjusted to pH 4.0 with saturated iminodiacetic acid. The flow rate was 0.2 mL/min. Each of the concentrated depleted serum samples was diluted with start buffer to 2.2 ml; 2.0 ml of this mixture was injected to the chromatofocusing column. The pH was measured online, with the UV absorbance of the eluent monitored at 280 nm. The system was allowed to equilibrate for 1 hour and a linear pH gradient from 7.1 to 4.0 was generated by changing the mobile phase from the start buffer to the elution buffer. The pH gradient elution was followed by a 1 M NaCl salt-wash to remove residual protein. The fractions were collected at 0.2 pH unit intervals from pH 7.0 to 4.0.

2.4. Determination of differentially expressed proteins with NPS RP-HPLC coupled to ESI-TOF-MS

The fractions collected from CF separations of the nine samples were further resolved by NPS RP-HPLC. As the initial analysis found more peaks appearing at a relatively low pH range, we focused on the proteins in the pH 5.0–5.2 range. To allow for possible peak shift, three CF fractions (pH 4.8–5.0, pH 5.0–5.2 and pH 5.2–5.4) of each sample were separated with NPS RP-HPLC (Beckman, PF2D HPRP column, 33 mm × 4.6 I.D.). We used 0.5% formic acid in water as solvent A and 0.5% formic acid in acetonitrile as solvent B. The fractions from CF were multiply injected in 100 μL to the NPS RP-HPLC column. The gradient used for each RP-HPLC run was 5% B for 2 minutes, 5% to 10% B in 1 min, 10% to 30% B in 5 min, 30% to 40% B in 8 min, 40% to 50% B in 5 min and 50% to 100% B in 5 min, followed by two fast gradient washes. The flow rate was 0.75 ml/min. The temperature of the column was kept at 50°C with a column heater. The column eluent was split into two fractions with a post-column Analytical Adjustable Flow splitter (Analytical Scientific Instruments, El Sobrante, CA, USA): about 0.05 ml/min flow went to a LCT ESI-TOF mass spectrometer (Waters/Micromass, Milford, MA, USA) to determine the molecular weight of the proteins and the corresponding intensities, and about 0.7 ml/min flow went to UV detector and collected according to peaks for further analysis by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization quadrupole ion trap time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-QIT-TOF-MS).

The ESI-TOF-MS experiments were performed with a LCT Premier mass spectrometer (Waters/Micromass) operating in V mode. The instrument was calibrated with the cluster peaks of a mixture of sodium iodide and cerium iodide, according to manufacturer’s instructions. The parameters for the LCT Premier and for ionization were: capillary voltage 3500 V; sample cone 115 V; extraction cone 1V; reflection lens 750 V; desolvation temperature 220°C; source temperature 110°C; MCP detector 2200 V; nitrogen gas flow 300 L/h. One μg of bovine insulin (Sigma) was added to the sample as an internal standard for the normalization of the ion intensities. MaxEnt1 software (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) was used to deconvolute the combined ESI spectra to obtain the intact molecular weight of the proteins as well as the corresponding ion intensities. To minimize ion intensity deviation due to the software processing, the elution time ranges of the molecules were initially determined from extracted multiple-charged ion current, followed by combination and deconvolution with MaxEnt1. Deconvolution was performed with a destination mass range of 4–10 kDa (also checked mass range of 4–85 kDa to ascertain that the analyzed peaks were not harmonic peaks of higher molecular weight molecules), 1 Da resolution and 0.75 uniform Gaussian peak widths.

2.5. Trypsin digestion and MALDI-QIT-TOF-MS and MS/MS identification

The fractions collected from the second dimension were concentrated to 20 μL with a CentriVap concentrator (Labconco); 20 μL 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate and one μL of 18 μg/μL sequencing grade modified trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was added to each sample. The solution was allowed to digest in the dark at 37°C overnight. Each sample was then desalted, concentrated to 5 μL with a ZiptipC18 tip (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and spotted onto the target plate by mixing 0.5 μL matrix with standards followed by 0.5 μL of a ziptipped sample. The spots were allowed to air dry. MALDI-QIT-TOF-MS or MS/MS experiments were performed on an AXIMA QIT (Shimadzu Biotech, Kyoto, Japan and Kratos Analytical, Manchester, UK) mass spectrometer equipped with a 337 nm nitrogen laser in either positive ion or negative ion mode. The matrix was 20 mg/ml 2,5-dihydroxybenzonic acid (DHB) (Waters) in 80% acetonitrile, as instructed by the manufacturer. The TOF was externally calibrated either in the positive mode or negative mode with the mixture of 500 fmol/l bradykinin fragment 1–7 (positive: 757.40 m/z, negative: 755.38 m/z), angiotensin II (positive: 1046.54 m/z, negative: 1044.53 m/z), P14R (positive: 1533.86 m/z, negative: 1531.84 m/z) and ACTH 18–39 (positive: 2465.20 m/z, negative: 2463.18 m/z).

As the baseline was not flat in the MS spectrum for the tryptic digests of the 8915 Da and 8204 Da proteins, it was determined that automatic peak picking via setting a single noise threshold would arbitrarily exclude a significant number of actual peaks. To avoid this, the spectrum was divided into a several sections, each section having a relatively flat baseline, and signal peaks of each section were selected by the software. The m/z values of the peaks were searched online against the UniProt database using the Mascot search engine (Matrix Science, Boston, MA, USA), with the tolerance for peptide mass set as 100 ppm, the charge state set as 1+, the maximum missed cleavage set as 1 and the enzyme set as trypsin. Several MS peaks were selected for subsequent MS/MS analysis and the m/z values of the MS/MS peaks were searched against the UniProt database using Mascot search engine. The parameters for the MS/MS search were as follows: the tolerance for peptide mass set as 150 ppm, the tolerance for fragment mass was 0.6 Da, the maximum missed cleavage set as 2 and the enzyme set as semi-trypsin.

Analysis of a protein peak observed at 9422 Da was considerably more involved. The MS analysis of the tryptic digests of this protein revealed four dominant peaks and several lower intensity peaks; however the PMF database did not return any positive matches. Interestingly, the MS analysis of the fractions containing the m/z 8765 peaks showed that it has two similar major peaks to those observed for the m/z 9422 peak, indicating the m/z 9422 peak could be a derivative form of the m/z 8765 peak. MS/MS analysis was performed on the tryptic peaks m/z 2137.0, m/z 1097.4, m/z 1462.9, m/z 2644.5 and m/z 1907.5, with all the above-mentioned MS and MS/MS analyses performed in positive mode. Identification of the 9422 Da molecule from positive mode mass spectrometry analysis was found to be difficult. Negative mode mass spectrometry analysis may provide additional information, as the molecule may have different stability and ionization property under different modes. Thus, negative mode MS analyses were also performed for the tryptic digests of the 9422 Da and 8765 Da proteins and negative mode MS/MS analysis was performed for the peak m/z 2791.3.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Determination of differentially expressed low molecular weight serum proteins

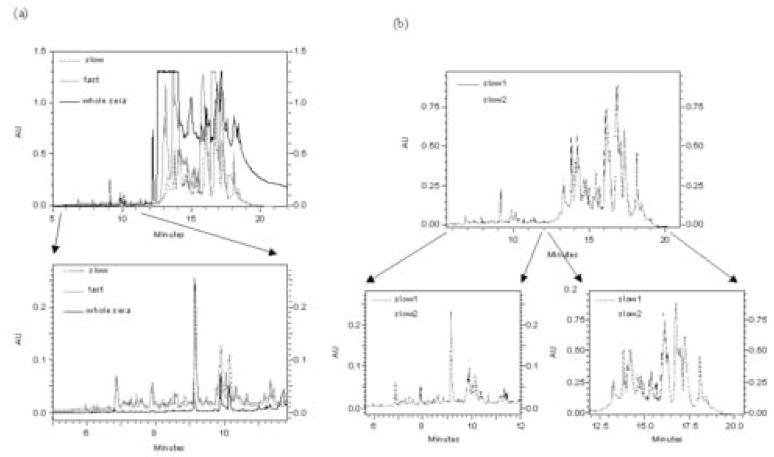

Acetonitrile preferentially precipitates high molecular weight proteins as well as disrupts the interaction of low molecular weight proteins to the carrier proteins (such as human serum albumin). It was previously shown that different precipitation rates produce qualitatively different results. Slow precipitation causes a larger amount of high molecular weight proteins to precipitate, and removed more protein, making it easier to analyze low abundance molecules (Figure 1a). Subsequent analysis of intact protein molecular weights demonstrated the inclusion of a significant number of low molecular weight proteins. On the other hand, the slow precipitation procedure may also decrease co-precipitation, possibly improving overall recovery. As shown in Figure 1b, the slow precipitation method is highly reproducible, based upon the UV absorbance of the proteins in depleted serum samples. This reproducibility should also reflect the abundant proteins in the depleted serum samples

Figure 1.

Effect of depletion with acetonitrile precipitation. (a) Comparison of the chromatograms for depleted serum with the slow precipitation, depleted serum with the fast precipitation and undepleted serum. Black line: chromatogram of whole serum; grey line: chromatogram of supernatant of serum by fast precipitation; dashed line: chromatogram of supernatant of serum by slow precipitation. (b) Chromatograms of the supernatants of two aliquots of serum depleted separately with the slow precipitation method. Please see the text for other information.

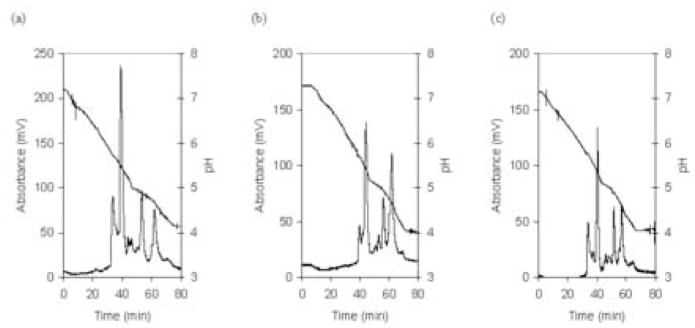

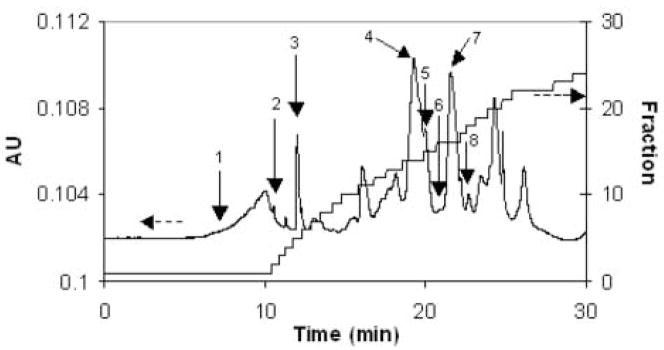

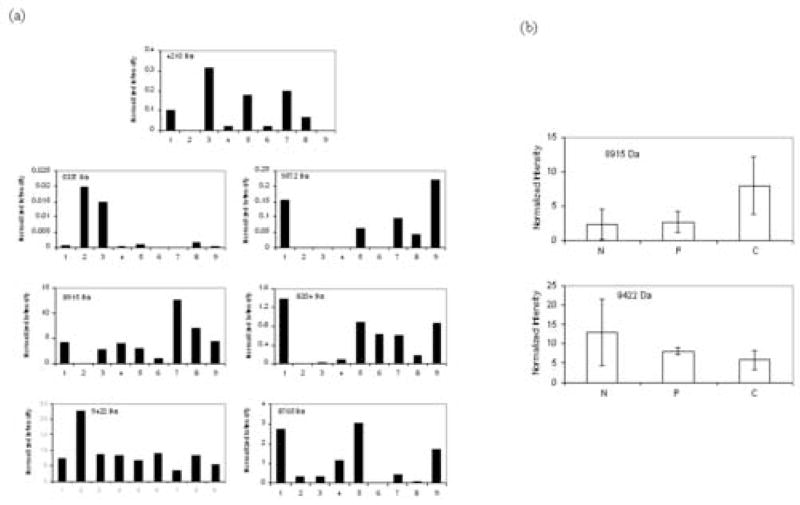

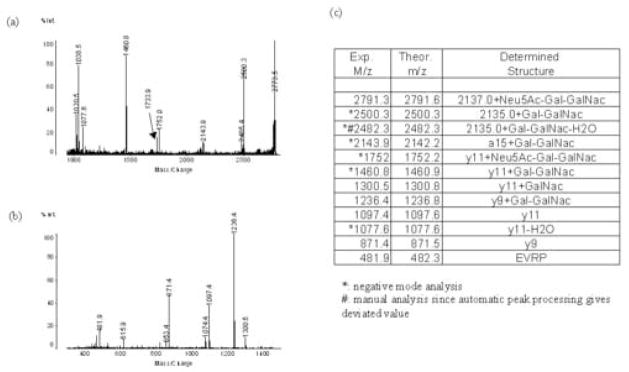

Based upon these results, the slow precipitation method was used to deplete three normal, three chronic pancreatitis and three pancreatic cancer serum samples. The depleted serum samples were then separated by chromatofocusing (Figure 2), as described. Because of a shift between the fractions of different samples due to the response drift of the electrode, it was necessary to compare the neighboring fractions together in order to reliably find differentially expressed proteins. Although the primary focus in this work was on proteins eluting between pH 5.0 and 5.2, data analysis was also carried out on adjacent fractions, i.e. 4.8–5.0 and 5.2–5.4. Each fraction was analyzed with NPS RP-HPLC coupled with ESI-TOF-MS. An example UV chromatogram of the NPS RP-HPLC separation is shown in Figure 3. The chromatograms obtained were combined and deconvoluted to find the molecular weights and the corresponding intensities of the molecules (14). Only a small degree of variation in ion intensity of the insulin internal standard was observed, indicating the ionization conditions were nearly the same in all experiments. To further decrease the variation of the ion intensity due to the small change of the ionization, we used the ion intensity of the insulin peak to normalize the sample peaks. This procedure was repeated for the three fractions of each sample and intensities for proteins with the same molecular weight were summed. Figure 4a shows the relative intensity of six low molecular weight proteins for the nine samples (some other proteins were detected, but they either did not show reproducible changes or the changes were too small to provide a meaningful comparison considering the accuracy of the methods). In particular, the intensity of the protein at 8915 Da appeared to be up-regulated in pancreatic cancer serum samples. In contrast, the protein at 9422 Da appeared to be down-regulated. Figure 4b shows the average intensities of the three samples for each type of patient for the two proteins. The average concentration of the protein at 8915 Da in serum from pancreatic cancer patients is about twice that found in normal serum samples and pancreatitis serum samples.

Figure 2.

Comparison of chromatofocusing separation of depleted normal, chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer serum samples: (a) normal, (b) chronic pancreatitis and (c) pancreatic cancer.

Figure 3.

An UV chromatogram of a NPS-HPLC separation. The sample was collected during pH interval 5.0–5.2 of chromatofocusing separation of a pancreatic cancer serum sample. The dashed arrow indicates the axes corresponding to the UV absorbance at 280 nm and related fractions. The peaks labeled as 1 is the position corresponding to the elution of the 5337 Da molecule (not observed in this chromatogram), 2–8 are the peaks of 4210 Da, insulin, 9422 Da, 8765 Da, 9572 Da, 8915 Da and 8204 Da molecules.

Figure 4.

Comparison of normalized intensities of low molecular weight molecules of normal, chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer serum samples. (a) The ion intensities of the nine serum samples. 1–3: normal, 4–6: chronic pancreatitis and 7–9: pancreatic cancer. (b) The average ion intensities of normal, chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer serum samples. N: normal, P: chronic pancreatitis, C: pancreatic cancer. The error bar is one standard deviation.

3.2. Identification of proapolipoprotein C-II and mature apolipoprotein C-II

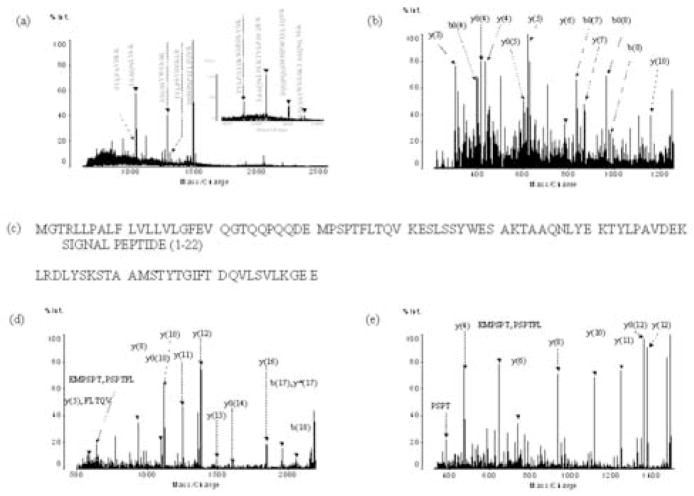

For the fractions corresponding to the protein at 8915 Da, the MS analysis of the digested peptides is shown (Figure 5a). MS/MS analysis of the peak m/z 1286.5, one of the tryptic-digested peptides, provided a high quality spectrum (Figure 5b). The database search, using the Mascot search engine, identified the protein as apolipoprotein C-II precursor. However, the molecular weight of apolipoprotein C-II precursor from the database is 11,284 Da, 2369 Da higher than the intact molecular weight determined by LCT-MS, possibly caused by post-translational protein modifications.

Figure 5.

MALDI-QIT-TOF-MS analysis of the 8915 Da and 8204 Da peptides. (a) MS spectrum of tryptic digests of the 8915 Da and 8204 Da peptides; the peak labeled with “*” is the specific peptide of proapolipoprotein C-II and the peak labeled with “#” is the specific peptide of mature apolipoprotein C-II, (b) MS/MS spectrum of peak m/z 1286.5; (c) Sequence obtained from the database based on PMF and MS/MS search with the data from Figures 5a and 5b; (d) MS/MS analysis of the specific peptide peak m/z 2203.1 of proapolipoprotein C-II; (e) MS/MS analysis of the specific peptide peak m/z 1492.7 of mature apolipoprotein C-II.

From the amino acid sequence obtained from the database, the apolipoprotein C-II precursor is composed of two parts: a signal peptide (amino acid residues 1–22) and proapoliprotein C-II (amino acid residues 23–101) (Figure 5c). The molecular weight for proapolipoprotein C-II is 8914.9 Da (15), suggesting the protein at 8915 Da is, in fact, proapolipoprotein C-II. However, there should be a tryptic peptide (residues 23–41), which is not present in the database. The m/z value for this peptide was calculated to be 2203.0 and was detected, as shown in Figure 5a. To further confirm the protein at 8915 Da is proapolipoprotein C-II, MS/MS analysis was carried out on the m/z 2203.0 peptide (Figure 5d). Because the database only contains the sequence for apolipoprotein C-II precursor, the in silico tryptic peptide for the proapolipoprotein C-II was not present. However, one side of the peptide sequence was the same as a tryptic peptide in the database. Thus, when we performed the database search, we chose the enzyme “semi-trypsin” instead of trypsin. The searched result indeed demonstrated that it is apolipoprotein C-II precursor. Combining the actual molecular weight of this protein and the specific tryptic peptide identified the protein as apolipoprotein C-II. Taking into consideration the actual sequence, the protein coverage from the database search for this protein is about 70%. The reported pI’s of 4.82 (15) for proapolipoprotein C-II and of 5.01 (16) for apolipoprotein C-II is concordant with the observed pH range 4.8–5.4.

Interestingly, from the literature, we found that the molecular weight of 8204 Da determined by ESI-MS is the same as that of the mature apolipoprotein C-II (15), corresponding to amino acid residues 29–101. The mature apolipoprotein C-II shared most tryptic peptides with proapolipoprotein C-II. Additionally, if the protein at 8204 Da is mature apolipoprotein C-II, then a specific tryptic peptide at m/z 1492.65 should be observed, as shown in Figure 5a. MS/MS analysis of the peak at m/z 1492.65 with “semi-trypsin” as the search enzyme identified it is apolipoprotein C-II precursor (Figure 5e). The combination of the actual molecular weight of this protein and the specific peptide confirmed it is mature apolipoprotein C-II. The protein coverage from the mass spectrometry data is 67% of the actual sequence of mature apolipoprotein C-II.

According to the processing pathways of apolipoprotein C-II precursor proposed previously (17), the up-regulated proapolipoprotein C-II protein may be explained as resulting from a missed proteolytic cleavage that failed to convert proapolipoprotein C-II to mature apolipoprotein C-II.

3.3. Identification of apolipoprotein C-III0 and apolipoprotein C-III1

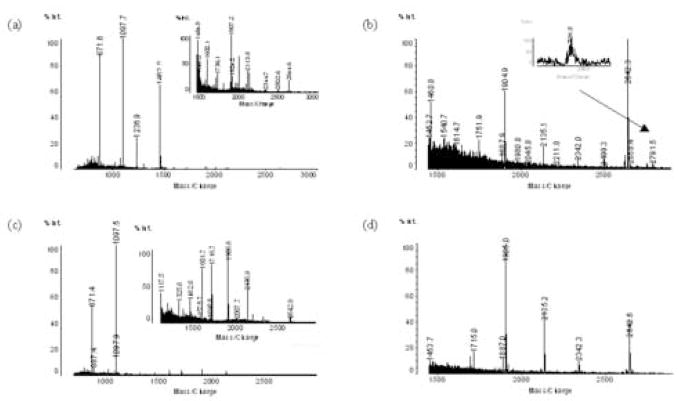

The identification of the protein at 9422 Da was more complicated. Both positive mode and negative mode of MALDI-QIT-TOF-MS analysis of the tryptic digested peptides of the fraction containing the 9422 Da protein showed four strong peaks as well as several minor ones (Figures 6a, 6b). MALDI-QIT-TOF-MS analysis of the tryptic peptide from a fraction containing the m/z 8765 peak showed a similar pattern with two major peaks presented and several smaller peaks (Figures 6c, 6d). By increasing the helium cooling time, the intensity of the tryptic peptide m/z 2137.0 increased and the MS/MS analysis of this m/z 2137.0 peak (Figure 6a) resulted in the same two dominant peaks as shown (Figures 6a, 6c), suggesting that the two peaks in Figures 6a and 6c were the result of the post-source decay fragments of the tryptic peptide m/z 2137.0. The m/z 871.4 peak seen in Figures 6a, 6c and 7a is also the fragment of the m/z 1097.4 peak (Figure 7b). Database searching, using the fragment peaks of 2137.0 and 1097.4, showed that the proteins at 8765 Da and at 9422 Da are both apolipoprotein C-III precursor (Figure 7c). However, the theoretical molecular weight for the apolipoprotein C-III precursor is 10,852 Da, which is 1430 Da higher than the actual molecular weight determined from ESI-TOF-MS. By analysis of the amino acid sequence of the apolipoprotein C-III precursor (Figure 7c), we found that the molecular weight of the apolipoprotein C-III (amino acid residues 21–99) without the signal peptide is approximately 8765 Da (15). The apolipoprotein C-III is also called apolipoprotein C-III0, since it has no sialic acid in comparison with apolipoprotein C-III1 and apolipoprotein C-III2 which contain one and two sialic acids, respectively. To confirm the 8765 Da peak as apolipoprotein C-III0, there should be a specific tryptic peptide (amino acid residues 21–37) or other miss-cleaved peptides starting from sequence 21. The theoretical m/z value for these putative peptides are 1906.9, 2344.1 (one missed cleavage) and 2644.3 (two missed cleavage), with corresponding peptides detected as shown (Figures 6c, 6d). Online search of MS/MS fragments for 1907.5 (Figure 7d) and 2644.2 (Figure 7e) using “semi-trypsin” as the search enzyme with Mascot confirmed the corresponding protein is apolipoprotein C-III0. The pI of apolipoprotein C-III0 was reported to be 4.95 (15) and 5.10 (16), respectively, concordant with the pH range measured here.

Figure 6.

MS spectrum of MALDI-QIT-TOF analysis of tryptic digests of the 8765 Da and 9422 Da proteins. (a) Positive mode, tryptic digests of the 9422 Da protein. (b) Negative mode, tryptic digests of 9422 Da protein. (c) Positive mode, tryptic digests of 8765 Da protein; (d) Negative mode, tryptic digests of 8765 Da protein.

Figure 7.

Identification of the 8765 Da peptide. (a) MALDI-QIT-TOF MS/MS analysis of the tryptic peak m/z 2316.9. (b) MALDI-QIT-TOF MS/MS analysis of the peak m/z 1097.7 in Fig. 6a. (c) Sequence obtained from the database based on MS/MS search with the data from Fig. 7a and 7b. (d) MS/MS analysis of the specific peptide peak m/z 2644.5 of apolipoprotein C-III0. (e) MS/MS analysis of the specific peptide peak m/z 1907.0 of apolipoprotein C-III0.

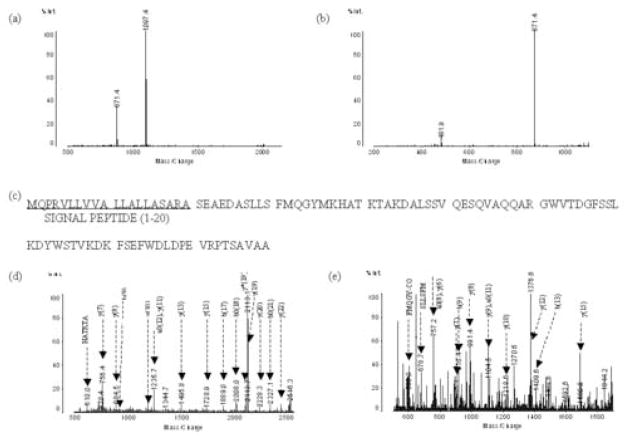

As shown in Figure 6, the tryptic peaks of 8765 Da and 9422 Da proteins share many common peaks, suggesting the 9422 Da protein is a modified form of the protein at 8765 Da. We found that apolipoprotein C-III1, an O-linked glycosylation of apolipoprotein C-III0 at residue 94 (threonine) with N-acetyl-galactosamine followed by galactose and sialic acid, has a similar molecular weight, i.e. 9421.3 Da (15). If the protein at 9422 Da is apolipoprotein C-III1, there should be a corresponding glycosylated peptide for amino acid residues 81–99. The m/z value for this is about 2793.6 in the positive mode, however few peaks were observed in this region during positive mode experiments. As glycosylated peptides are more efficiently ionized in negative mode, we reanalyzed the sample in negative mode. Data analysis revealed a small peak with m/z 2791.3 (Figure 6b), consistent with the theoretical value in the negative mode. The MS/MS analysis of this peak showed many peaks including one with m/z 1460.8 (Figure 8a). The MS/MS analysis of the corresponding positive peak of m/z 1462.9 (Figure 8b) demonstrated that its fragment peaks include m/z 871.4 and m/z 1097.4, the same fragments as those of 2137.0 (Figure 7a), as well as post-source decay peaks shown (Figures 6a and 6c). Comparing the fragment peaks of m/z 2791.3 and 1462.9 with the fragment peaks of peak m/z 2137.0 confirmed that the protein at 9422 Da is the Neu5Ac-Gal-GalNac-O-linked glycosylated apolipoprotein C-III0 or Apolipoprotein C-III1. The previously reported pI’s of 4.80 (15) and 4.92 (16) of Apolipoprotein C-III1 are concordant with the pH range measured here.

Figure 8.

Identification of the 9422 Da peptide. (a) MALDI-QIT-TOF MS/MS analysis of the tryptic peak 2791.3 (negative mode). (b) MALDI-QIT-TOF MS/MS analysis of peak m/z 1462.9 in Fig. 6a. (c) Identification of the structure of 9422 Da molecules based on the theoretical fragment peaks of 2137.0 and the experimental m/z values in Figure 8a and 8b.

Apolipoprotein C-III is an inhibitor of lipoprotein lipase (18–19) and its elevated concentration is thought to be a strong indicator of coronary risk in men, and contributes to the increased cardiovascular risk and type 2 diabetes (20) by decreasing triglyceride catabolism in serum.

4. Concluding remarks

Normal, chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer serum samples were depleted by acetonitrile precipitation and analyzed by two-dimensional LC separation combined with ESI-TOF-MS. The concentration of an 8915 Da protein was found to be increased, and the concentration of a 9422 Da protein decreased, in pancreatic cancer patient’s sera as compared to both normal and chronic pancreatitis sera. Both proapolipoprotein C-II and apolipoprotein C-III1 were identified by combining typical database search results with the MS and MS/MS data of the tryptic peptides, molecular weight of the intact molecules and the database search results with “semi-trypsin” as the search enzyme for the specific peptides. Additionally, we have developed methodology for the determination of accurate protein sequences by combining precise measures of intact molecular weight with specific peptide confirmation not found in typical bottom-up methods. These methods have enabled us to determine specific protein isoforms and will increase the reliability of identifying candidate markers of cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported under a Michigan Economic Development Grant MEDC03-622 and received partial support by the National Institutes of Health under Grant R01 GM49500. We thank Mr. Koichi Tanaka from Shimadzu Bioscience for his assistance with the identification of two of the dominant post-source decay peaks in Figure 5a, and thank Dr. Subramanian Pennathur for a critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, Samuels A, Tiwari RC, Ghafoor A, Feuer EJ, Thun MJ. Cancer Statistics 2005. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:10–30. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tirumalai RS, Chan KC, Prieto DA, Issaq HJ, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2003;2:1096–1103. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300031-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bjorhall K, Miliotis T, Davidsson P. Proteomics. 2005;5:307–317. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200400900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hinerfeld D, Innamorati D, Pirro J, Tam Sun W. J Biomol Techniques. 2004;15:184–190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fang X, Curran KW, Huang L, Xiao W, Strauss W, Harvie G, Feitelson J, Zhang WW. Frontiers Biotechnol Pharm. 2004;4:222–245. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogata Y, Charlesworth MC, Muddiman DC. J Proteome Res. 2005;4:837–845. doi: 10.1021/pr049750o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao J, Simeone DM, Heidt D, Anderson MA, Lubman DM. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:1792–1802. doi: 10.1021/pr060034r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liotta LA, Ferrari M, Petricoin E. Nature (London, UK) 2003;425:905. doi: 10.1038/425905a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou M, Lucas DA, Chan KC, Issaq HJ, Petricoin EF, III, Liotta LA, Veenstra TD, Conrads TP. Electrophoresis. 2004;25:1289–1298. doi: 10.1002/elps.200405866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alpert AJ, Shukla AK. presented at the 8th Annual Meeting of the Association for Biomolecular Resource Facilities (ABRF 2003); Denver, CO. 10–13 February 2003; poster P111-W. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merrell K, Southwick K, Graves WS, Esplin MS, Lewis NE, Thulin CD. J Biomol Techniques. 2004;15:238–248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang H, Kachman MT, Schwartz DR, Cho KR, Lubman DM. Proteomics. 2004;4:2476–2495. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamler RL, Zhu K, Buchanan NS, Kreunin P, Kachman MT, Miller FR, Lubman DM. Proteomics. 2004;4:562–577. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang H, Kachman MT, Schwartz DR, Cho KR, Lubman DM. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:3168–3181. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200209)23:18<3168::AID-ELPS3168>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bondarenko PV, Cockrill SL, Watkins LK, Cruzado ID, Macfarlane RD. J Lipid Res. 1999;40:543–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bugugnani MJ, Koffigan M, Kora I, Ouvry D, Clavey V, Fruchart JC. Clin Chem. 1984;30:349–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fojo SS, Taam L, Fairwell T, Ronan R, Bishop C, Meng MS, Hoeg JM, Sprecher DL, Brewer HB., Jr J Biol Chem. 1986;261:9591–9594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown WV, Baginsky ML. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1972;46:375–382. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(72)80149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krauss RM, Herbert PN, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Cir Res. 1973;33:403–411. doi: 10.1161/01.res.33.4.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Onat A, Hergenc G, Sansoy V, Fobker M, Ceyhan K, Toprak S, Assmann G. Atherosclerosis (Shannon, Ireland) 2003;168:81–89. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(03)00025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]