Abstract

Interactions between dopamine (DA) and glutamate systems in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) are important in addiction and other psychiatric disorders. Here, we examined DA receptor regulation of NMDA receptor surface expression in postnatal rat PFC neuronal cultures. Immunocytochemical analysis demonstrated that surface expression (synaptic and non-synaptic) of NR1 and NR2B on PFC pyramidal neurons was increased by the D1 receptor agonist SKF 81297 (1 µM, 5 min). Activation of protein kinase A (PKA) did not alter NR1 distribution, indicating that PKA does not mediate the effect of D1 receptor stimulation. However, the tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein (50 µM, 30 min) completely blocked the effect of SKF 81297 on NR1 and NR2B surface expression. Protein cross-linking studies confirmed that SKF 81297 (1 µM, 5 min) increased NR1 and NR2B surface expression, and further showed that NR2A surface expression was not affected. Genistein blocked the effect of SKF 81297 on NR1 and NR2B. Surface-expressed immunoreactivity detected with a phospho-specific antibody to tyrosine 1472 of NR2B also increased after D1 agonist treatment. Our results show that tyrosine phosphorylation plays an important role in the trafficking of NR2B-containing NMDA receptors in PFC neurons and the regulation of their trafficking by DA receptors.

Keywords: D1 receptor, D2 receptor, glutamate receptors, prefrontal cortex neurons, protein tyrosine kinase, receptor trafficking

Dopamine (DA) is an important regulator of neuronal excitability and glutamate-dependent plasticity in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) (Jay 2003; Otani et al. 2003; Seamans and Yang 2004; Castner and Williams 2007). This may contribute to the ability of DA-releasing psychomotor stimulants like cocaine to influence synaptic plasticity and addiction-related behaviors (Wolf et al. 2004; Kauer and Malenka 2007). Changes in synaptic strength during several types of plasticity involve regulated trafficking of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoazole-4-proprionic acid (AMPA) receptors (Malinow and Malenka 2002; Shepherd and Huganir 2007) and N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors (Wenthold et al. 2003; Pèrez-Otaño and Ehlers 2005; Lau and Zukin 2007). Changes in the subunit composition of ionotropic glutamate receptors also contribute to synaptic plasticity (Cull-Candy and Leszkiewicz 2004; Cull-Candy et al. 2006). Our prior studies have shown that DA receptors regulate AMPA receptor trafficking in the PFC and other regions (Chao et al. 2002; Mangiavacchi and Wolf 2004; Sun et al. 2005, 2008; Gao et al. 2006; Gao and Wolf 2007). In this study, we investigated the effect of DA receptor stimulation on NMDA receptor trafficking in PFC pyramidal neurons in primary cultures.

Functional NMDA receptors are tetrameric complexes of NR1, an obligatory subunit, and different NR2 subunits, with subunit composition determining NMDA receptor channel properties (Dingledine et al. 1999; Cull-Candy and Leszkiewicz 2004). NR2A and NR2B are the major NR2 subunits in cortical neurons (Kutsuwada et al. 1992; Ishii et al. 1993; Watanabe et al. 1993; Monyer et al. 1994), including pyramidal neurons of the rat PFC (Rudolf et al. 1996). At mature synapses in most regions, NMDA receptors likely consist of NR1/NR2B, NR1/NR2A and NR1/NR2A/ NR2B subtypes (Cull-Candy and Leszkiewicz 2004; Lau and Zukin 2007). Trafficking of NMDA receptors is regulated at several steps, including export from the endoplasmic reticulum and activity-dependent redistribution of receptors into and away from the synapse (Wenthold et al. 2003; Lau and Zukin 2007).

In the present study, we examined DA receptor regulation of NMDA receptor trafficking in rat PFC cultures using a combination of fluorescence microscopy and protein cross-inking approaches. Our results suggest that brief D1 receptor stimulation increases synaptic and non-synaptic surface expression of NR1/NR2B-containing receptors through a mechanism involving tyrosine phosphorylation of NR2B. A similar pathway has been described in striatal neurons (Dunah and Standaert 2001; Dunah et al. 2004; Hallett et al. 2006).

Materials and methods

Animals

All animal use procedures were in strict accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science. Pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA; Zivic Miller, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), obtained at 19–20 days of gestation, were housed individually in breeding cages. One-day-old offspring were used to prepare PFC cultures.

Prefrontal cortex cultures

The PFC from postnatal (P1) rats was isolated and dissociated with papain (20–25 U/mL; Worthington Biochemical Corp, Lakewood, NJ, USA) at 37°C for 20–30 min. Cells were plated onto coverslips coated with poly-d-lysine (100 µg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) in 24-well culture plates at a density of 20 000 cells/well (for analysis by fluorescence microscopy) or in 6-well culture plates at a density of 200 000 cells/well (for analysis by western blotting). Cells were grown in NeuroBasal media (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) with 2 mM GlutaMax, 0.5% Gentamicin, and 2% B27 (Gibco). One-half of the media was replaced with above NeuroBasal growth medium every 4 days. Cultures were used for experiments between weeks 2 and 3.

Immunocytochemistry

Cell surface NR1 was labeled by incubating live cultures (neither fixed nor permeabilized) with a monoclonal antibody to the extracellular N-terminus of NR1 (ABR-Affinity BioReagents, Golden, CO, USA) in NeuroBasal growth media (1 : 24, 15 min, 37°C in 5% CO2 incubator). Unfortunately, we found that only certain lots of this antibody were useful for live cell labeling; with many lots, non-specific labeling was very high. Cells were then fixed with 4% formaldehyde (containing 4% sucrose) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 15 min, blocked with 5% donkey serum in PBS for 2 h and incubated with Alexa 488 donkey anti-mouse antibody (1 : 1000; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) for 1 h under non-permeant conditions. Then, cells were permeabilized with 0.3% saponin in PBS for 15 min, blocked with 5% donkey serum in PBS for 1 h, and incubated with polyclonal antibody to the synaptic marker synaptophysin (1 : 2000; Zymed Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at 4°C overnight followed by Cy3 donkey anti-rabbit antibody (1 : 500; Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature (RT).

Cell surface NR2B was labeled in cells that were fixed but not permeabilized. Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde (containing 4% sucrose) in PBS for 10 min, blocked with 5% donkey serum in PBS for 2 h and incubated with rabbit antibody directed against the extracellular N-terminus of NR2B (1 : 100; Zymed Laboratories) in PBS for 1 h, followed by Cy3 donkey anti-rabbit antibody (1 : 500) for 1 h at RT. Then, cells were permeabilized with 0.1 Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min, blocked with 5% donkey serum in PBS for 1 h, and incubated with monoclonal antibody to the synaptic marker synaptobrevin/vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 (1 : 2000; Synaptic Systems, Göttingen, Germany) overnight at 4°C followed by donkey anti-mouse secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa 488 (1 : 2000) for 1 h at RT.

Surface receptor cross-linking with bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate (BS3)

Following two washes with Hanks’ Balanced salt solution, cultures were incubated with 2 mM BS3 (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) in this solution for 10 min with agitation at 37°C (Hall and Soderling 1997a, b; Hall et al. 1997). Cross-linking was terminated by quenching the reaction with 100 mM glycine (10 min, 4°C). Cultures were harvested by scraping in ice-cold buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors [25 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 500 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride, 20 mM NaF, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate (Na3VO4), 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 µM microcystin-LF, 1 µM okadaic acid, 1X protease inhibitor cocktail set I (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA) and 0.1% Nonidet P-40 (v/v)]. Then cells were sonicated three times for 5 s each time on ice in 1.5 mL eppendorf tubes and centrifuged at 10 000 g for 5 min. The supernatant was aliquoted and stored at −80°C. Protein concentration was determined by the Bio-Rad assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Western blotting

Samples (15–20 µg total protein/lane) were run on 4–15% gradient Tris–HCl gels (Bio-Rad) under reducing conditions, and proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes for immunoblotting (Boudreau and Wolf 2005). Membranes were washed in double-deionized H2O (ddH2O) and blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk (for NR1, 30 min at RT) or 1% polyvinylpyrrolidone (for NR2A or NR2B, 1 h at RT) in TBS-Tween 20 (TBS-T). Membranes were then incubated with one of the following antibodies overnight at 4°C: NR1 (1 : 500; Upstate Cell Signaling, Lake Placid, NY, USA), NR2A (1 : 500; Santa Cruz, CA, USA), NR2B (1 : 1500; Calbiochem), phospho-specific NR2B-Tyr1472 (1 : 500; Calbiochem). Only some lots of the NR1 antibody gave satisfactory results in this assay; other lots did not recognize the cross-linked band. Membranes were washed extensively with TBS-T solution, incubated for 1 h with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG (goat anti-mouse, 1 : 5000; donkey anti-goat, 1 : 20 000; goat anti-rabbit, 1 : 5000; Upstate Cell Signaling), and washed extensively again in TBS-T. Membranes were then rinsed with ddH2O and immersed in chemiluminescence detecting substrate (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA) for 1 min. Images were collected on a Versa Doc Model 5000 (Bio-Rad) for 100–300 s. The diffuse densities of surface and intracellular bands in each lane were determined using TotalLab (Nonlinear Dynamics, Newcastle, UK). Equal loading was verified by staining membranes with Ponceau S (Sigma-Aldrich).

Data Analysis

Images were acquired and analyzed as described previously (Sun et al. 2005; Gao et al. 2006) with an imaging system consisting of a Nikon inverted microscope, ORCA-ER digital camera (Hamamatsu Corp., Bridgewater, NJ, USA) and MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging Co., Downingtown, PA, USA). All experimental groups to be compared were run simultaneously using cells from the same culture preparation and all images were taken using identical acquisition parameters. For each experimental group, we selected approximately six cells each from at least four different wells. Cells were selected under phase contrast imaging, to avoid the possibility of experimenter bias based on the intensity of fluorescence staining. Processes located about one soma diameter from the soma were analyzed (processes were also selected under phase contrast imaging). The soma was excluded from all measurements. For each image, the total area of cell surface NMDA receptor subunit labeling (comprising synaptic plus non-synaptic labeling) was measured automatically using a threshold set at least two times higher than the average background fluorescence in processes of untreated control cells. The area of synaptobrevin or synaptophysin staining was defined using the same approach. Non-synaptic NMDA receptor subunit staining area was defined as the area of NR1 or NR2B surface staining (in arbitrary units) that did not overlap with synaptophysin or synaptobrevin staining, respectively. Synaptic staining area was defined as the area of NR1 or NR2B surface staining (in arbitrary units) that overlapped with synaptophysin or synaptobrevin staining, respectively. Overlap was assessed using the co-localization function of the MetaMorph software. Results from each experimental group were normalized to untreated control cells. All values refer to mean ± SEM. Independent group t-tests were used for comparisons between two experimental groups. For multiple groups, analysis of variance (anova) was used followed, when appropriate, by a Dunn’s test (significance set at p < 0.05; n = number of cells analyzed).

Drugs

(±)-6-Chloro-7,8-dihydroxy-1-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-3-benzazepine hydrobromide (SKF 81297), R-(+)-7-chloro-8-hydroxy-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-3-benzazepine hydrochloride (SCH 23390), Sp-Adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate triethylammonium salt hydrate (SpcAMPS), quinpirole, raclopride, and genistein were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Genistein was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide. Others were dissolved in water. Pervanadate was made by combining Na3 VO4 and H2O2 (50 : 1) just before use.

Results

DA agonists regulate NR1 surface expression in PFC cultures

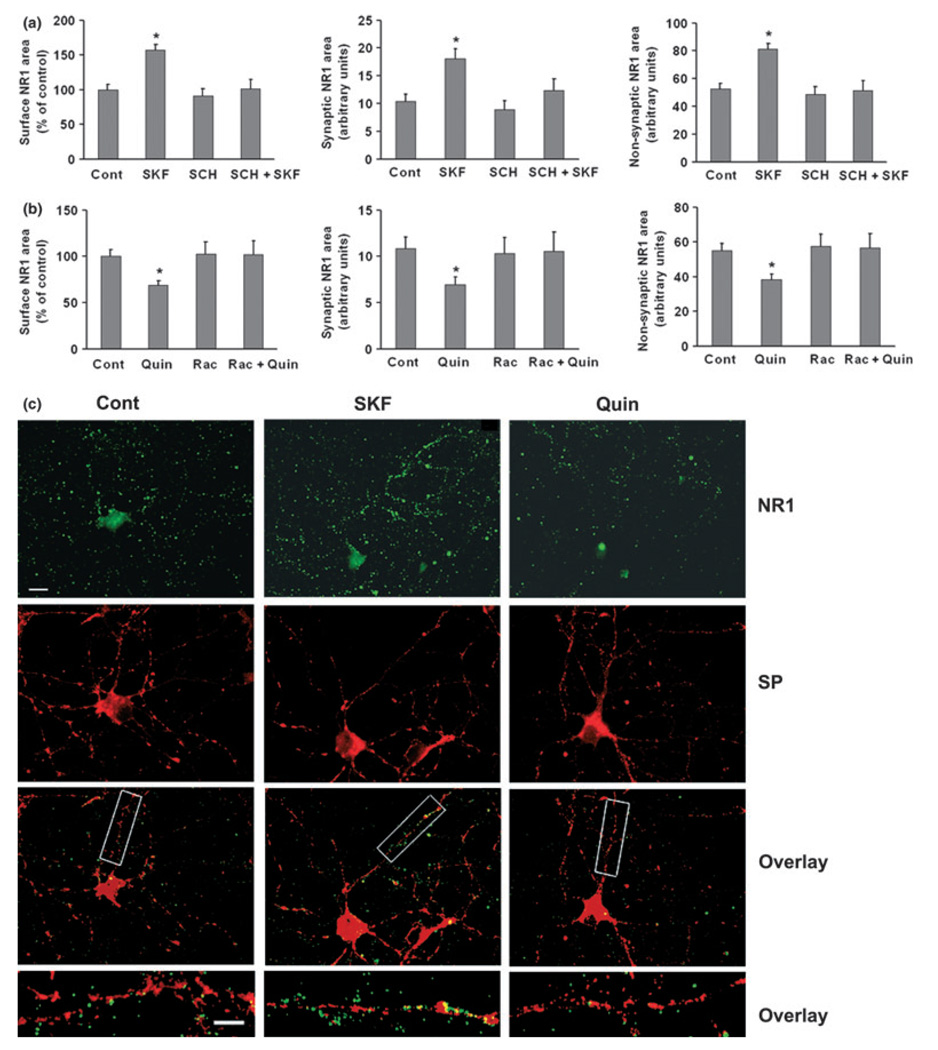

We began by examining NR1 because it is an obligatory NMDA receptor subunit. PFC cultures (2–3-weeks old) were incubated with media (control group), the D1 agonist SKF 81297 (SKF, 1 µM, 5 min) or the D2 agonist quinpirole (Quin, 1 µM, 5 min) to determine the effect of DA receptor stimulation on cell surface NR1 expression. Drug concentrations and incubation times were based on prior studies (Mangiavacchi and Wolf 2004; Sun et al. 2005; Gao et al. 2006). After drug treatment, cell surface NR1 was labeled by incubating live cells (neither fixed nor permeabilized) with antibody against the extracellular N-terminus of NR1. Then the cells were fixed, stained with secondary antibody, permeabilized, and stained for the synaptic marker synapt-ophysin. Staining area for total surface NR1 (synaptic plus non-synaptic), synaptic NR1 (surface NR1 staining co-localized with synaptophysin), and non-synaptic NR1 (surface NR1 staining not co-localized with synaptophysin) increased after SKF 81297 incubation (Fig. 1a and c), and decreased after quinpirole treatment (Fig. 1b and c). These effects were blocked if the D1 receptor antagonist SCH 23390 (10 µM) was added 5 min before SKF 81297 (Fig. 1a), or if the D2 receptor antagonist raclopride (1 µM) was added 5 min before quinpirole (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

D1 receptor stimulation increases synaptic and non-synaptic NR1 surface expression in cultured PFC pyramidal neurons, while D2 receptor stimulation has the opposite effect. (a) Neurons were treated with medium, the D1 agonist SKF 81297 (SKF, 1 µM, 5 min), the D1 receptor antagonist SCH 23390 (SCH, 10 µM, 5 min), or SCH+SKF (SCH was added 5 min before SKF). SKF 81297 significantly increased total surface NR1 expression including both synaptic and non-synaptic NR1 area (n = 23–51, Dunn’s test, *p < 0.05). (b) Neurons were treated with medium, the D2 receptor agonist quinpirole (Quin, 1 µM, 5 min), the D2 receptor antagonist raclopride (Rac, 10 µM, 5 min), or Rac+Quin (Rac was added 5 min before Quin). Quinpirole significantly decreased total surface NR1 expression including both synaptic and non-synaptic NR1 area (n = 20–48, Dunn’s test, *p < 0.05). Values are mean ± SEM. (c) Representative images of surface expression of NR1 (green), synaptophysin (red), and overlay (yellow). Lower panels show higher resolution of boxed regions. Scale bars: 20 µm for upper panels, 5 µm for lowest panels.

D1 receptors regulate NR1 surface expression through a PKA-independent pathway

Because D1 receptors are positively coupled to protein kinase A (PKA), we also tested the effect of incubation with SpcAMPS (10 µM, 5 min), a membrane-permeable PKA activator. SpcAMPS did not change surface NR1 expression (97.8 ± 13.0%, p > 0.05 compared with control, n = 22,). While these results do not rule out a role for PKA in the regulation of NR1 trafficking, they indicate that PKA activation is not sufficient for increased NMDA receptor surface expression. This contrasts with evidence that PKA mediates the effect of D1 receptor stimulation on AMPA receptor surface expression in PFC pyramidal neurons (Sun et al. 2005), hippocampal pyramidal neurons (Smith et al. 2005; Gao et al. 2006), and medium spiny neurons of the nucleus accumbens (Mangiavacchi and Wolf 2004; Sun et al. 2008).

D1 receptors regulate NR1 and NR2B surface expression via a tyrosine kinase-dependent pathway

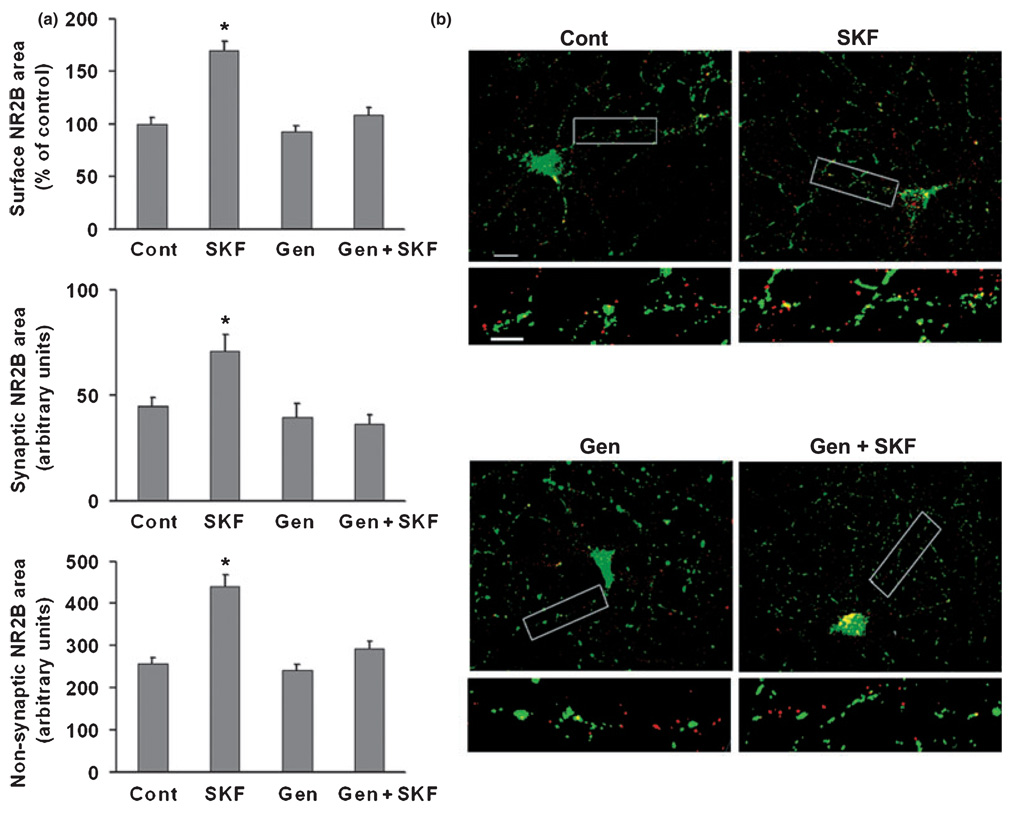

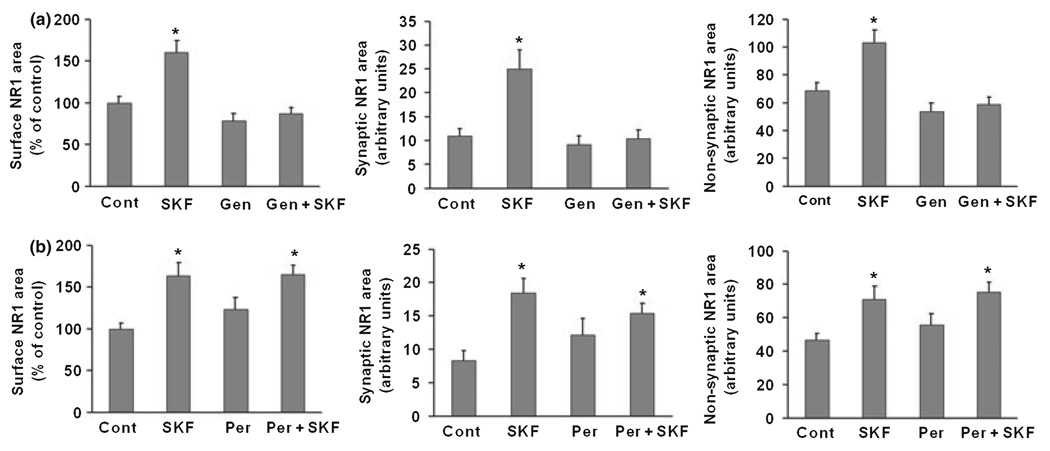

Tyrosine phosphorylation is an important mechanism for regulating NMDA receptor function in the brain (Salter and Kalia 2004; Chen and Roche 2007). Previous work has shown that D1 receptors regulate NMDA receptor trafficking in striatal neurons via a tyrosine kinase-dependent pathway (Dunah and Standaert 2001; Dunah et al. 2004; Hallett et al. 2006). We used genistein, a protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor, to test the role of tyrosine phosphorylation in regulating NMDA receptor trafficking in PFC neurons. We began by examining NR2 subunits because it is well established that they are phosphorylated at tyrosine residues (Moon et al. 1994; Lau and Huganir 1995; Dunah et al. 1998). An antibody to the extracellular domain was available for NR2B but not NR2A, so our immunocytochemical studies were limited to assessing surface expression of NR2B (NR2A surface expression was measured using a protein cross-linking assay; see next section). NR2B surface expression was measured in cells that were fixed but not permeabilized. Similar to results reported above for NR1, enhanced NR2B surface expression (both synaptic and non-synaptic) was observed after incubation with SKF 81297 (1 µM, 5 min) (Fig. 2). The effect of SKF 81297 on NR2B localization was blocked when neurons were pre-treated with 50 µM geni-stein for 25 min prior to addition of SKF 81297 (Fig. 2). Genistein alone had no significant effect on NR2B localization (Fig. 2), indicating that basal NR2B surface expression is not dependent on tyrosine kinase activity. Next we examined NR1. Although NR1 is not a tyrosine kinase substrate (Lau and Huganir 1995), we hypothesized that D1 agonist-induced phosphorylation of NR2B drives increased surface expression of NR1/NR2B-containing receptors. Supporting this hypothesis, genistein completed blocked the SKF 81297-induced increase in total surface NR1, synaptic NR1 and non-synaptic NR1 staining area (Fig. 3a). No significant effects were observed when cultures were incubated with genistein alone (Fig. 3a). Pervanadate, a protein tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor, produced only a small trend towards increased NR1 surface expression, indicating that protein tyrosine phosphatase activity is not exerting a significant inhibitory effect on NMDA receptor surface expression under basal conditions (Fig. 3b). Pervanadate failed to influence D1 agonist effects on NR1 localization (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 2.

Protein tyrosine kinase inhibition blocks the effect of D1 receptor stimulation on NR2B surface expression in cultured PFC pyramidal neurons. (a) Neurons were treated with vehicle (0.2% DMSO), SKF 81297 (SKF, 1 µM), the tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein (Gen, 50 µM), or Gen+SKF. Total incubation time was 30 min, with SKF 81297 added to vehicle or genistein treated cultures for the last 5 min. Genistein blocked the effect of SKF 81297 on surface NR2B expression, synaptic NR2B area, and non-synaptic NR2B area (n = 19–26, Dunn’s test, *p < 0.05). Values are mean ± SEM. (b) Representative images of NR2B (red), synaptobrevin (green), and overlay (yellow). Lower panels show higher resolution of boxed regions. Scale bars: 20 µm for upper panels, 5 µm for lower panels.

Fig. 3.

Protein tyrosine kinase inhibition blocks the effect of D1 receptor stimulation on NR1 surface expression in cultured PFC pyramidal neurons. (a) Neurons were treated with vehicle (0.2% DMSO), SKF 81297 (SKF, 1 µM), the tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein (Gen, 50 µM), or Gen+SKF. Total incubation time was 30 min, with SKF 81297 added to vehicle or genistein treated cultures for the last 5 min. Genistein blocked the effect of SKF 81297 on total surface NR1 expression, synaptic NR1 area, and non-synaptic NR1 area (n = 19–26, Dunn’s test, *p < 0.05). (b) Neurons were treated with medium, SKF 81297 (SKF, 1 µM), the tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor pervanadate (Per, 200 µM), or Per+SKF. Total incubation time was 30 min, with SKF 81297 added to vehicle or pervanadate treated cultures for the last 5 min. Pervanadate alone produced a trend towards increased total surface NR1 expression, synaptic NR1 area, and non-synaptic NR1 area, but did not alter the effect of SKF (n = 18–28, Dunn’s test, *p < 0.05). Values are mean ± SEM.

Protein cross-linking experiments confirm that D1 receptors increase NR1 and NR2B surface expression via a tyrosine kinase signaling pathway

In order to study the NR2A subunit, and as a means of confirming our immunocytochemical results for NR1 and NR2B, we used the membrane-impermeant protein cross-linking reagent BS3 to study the effect of DA agonists on surface expression of NR1, NR2A, and NR2B subunits. BS3 selectively cross-links surface-expressed proteins, forming high molecular weight aggregates. Intracellular proteins are not modified and therefore retain their predicted molecular weights. Surface and intracellular receptor pools can thus be distinguished by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and western blotting. Previous studies have confirmed that BS3 does not crosslink intracellular proteins unless cross-linking is performed in a lysed preparation (Boudreau and Wolf 2005; Boudreau et al. 2007; Hall et al. 1997; Hall and Soderling 1997a, b; Archibald et al. 1998; Broutman and Baudry 2001; Grosshans et al.. 2002).

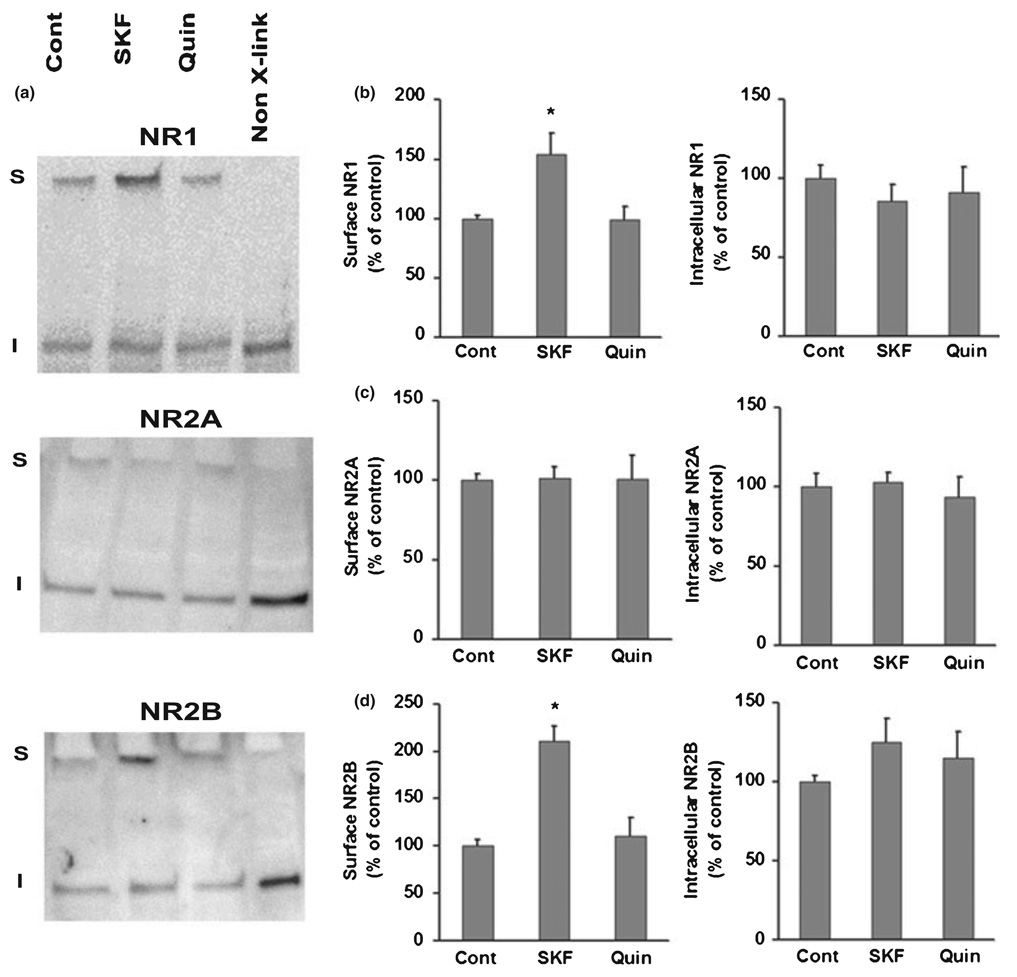

Both a predicted molecular weight band (corresponding to intracellular receptor subunits) and a high molecular weight band (corresponding to surface-expressed receptor subunits) were observed in cross-linked tissue prepared from PFC cultures and immunoprobed for NR1, NR2A or NR2B (Fig. 4a). As expected, no high molecular weight band was found in non-cross-linked tissue (Fig. 4a, right lanes in each blot). Incubation with the D1 agonist SKF 81297 (1 µM, 5 min) prior to cross-linking significantly increased surface levels of NR1 and NR2B, but had no effect on surface NR2A (Fig. 4). These data are consistent with immunocytochemical results indicating that SKF 81297 increases NR1 and NR2B surface staining (Fig 1–Fig 3). Interestingly, intracellular NMDA receptor subunit levels were not significantly altered by SKF 81297 (Fig. 4b–d). Decreased intracellular levels would have been expected if the new surface receptors were attributable to trafficking from intracellular to surface sites, so we interpret results in Fig. 4 to suggest that NR1/NR2B-containing receptors are being stabilized on the surface by SKF 81297 (see Discussion). Incubation with the D2 agonist quinpirole (1 µM, 5 min) prior to cross-linking had no effect on NR1 surface expression measured with BS3 cross-linking (Fig. 4a and b), in contrast to our immunocytochemical results showing decreased NR1 surface staining after quinpirole incubation (Fig. 1). Quinpirole also failed to alter NR2A or NR2B surface expression or intracellular levels of any NMDA receptor subunit measured with BS3 cross-linking(Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

D1 receptor stimulation increases NR1 and NR2B surface expression in PFC cultures, measured by BS3 cross-linking. PFC neurons were treated with medium (control), the D1 agonist SKF 81297 (SKF, 1 µM, 5 min), or the D2 agonist quinpirole (Quin, 1 µM, 5 min). After this incubation, cells were incubated with the membrane impermeant protein cross-linking reagent BS3 for 10 min and then harvested in lysis buffer. Some control cultures were treated identically but in the absence of BS3 (Non-X-link lanes). Protein (15–20 µg/ lane) was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and western blotting. Both high (surface-expressed, cross-linked; S) and predicted (intracellular, unmodified; I) molecular weight bands were detected in tissue from the cross-linked cultures (first 3 lanes in panel a) whereas only the predicted molecular weight bands were detected in non-cross-linked cells (Non-X-link lanes). The S band is estimated to be ~400–600 kDa while I bands for NR1, NR2A and NR2B are 130, 170 and 180 kDa, respectively. SKF 81297 significantly increased surface (S) levels of NR1 (b) and NR2B (d), but not NR2A (c) (n = 6–9, Dunn’s test, *p < 0.05); SKF 81297 had no significant effect on intracellular (I) levels of NR1, NR2A, or NR2B (b–d, n = 6–9, ANOVA, p > 0.05). Values are mean ± SEM.

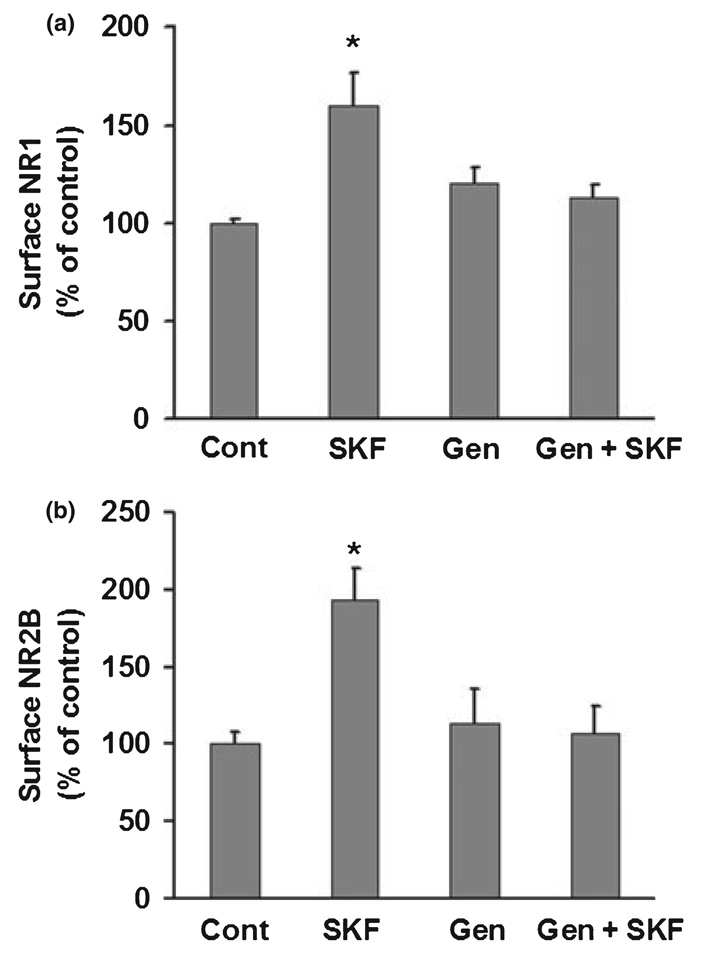

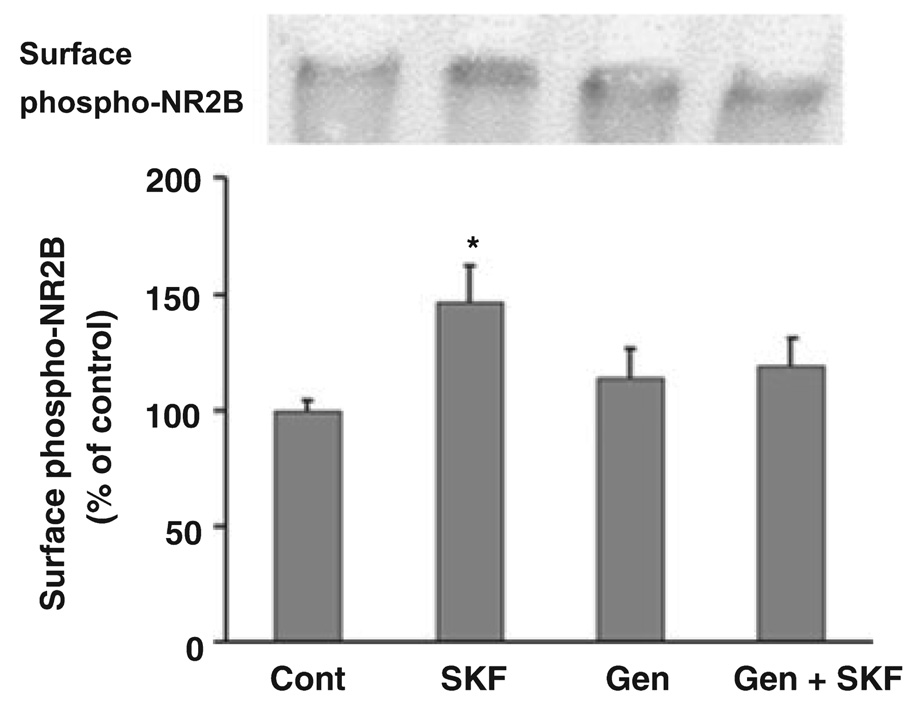

Our immunocytochemical results indicated that the D1 agonist-induced increase in surface NR1 and NR2B expression was mediated by tyrosine phosphorylation because genistein, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, completely blocked this effect of D1 receptor stimulation (Fig 2 and Fig 3). Confirming these results, genistein prevented the D1 agonist-induced increase in NR1 and NR2B surface expression measured using the BS3 cross-linking assay (Fig. 5). Tyrosine phosphorylation at Tyr1472 on NR2B plays an important role in NMDA receptor trafficking (see Discussion). To examine the role of this residue in our experiments, we probed cross-linked tissue with a phospho-specific NR2B-Tyr1472 antibody with the goal of comparing cell surface levels of phosphorylated NR2B in control and D1 agonist-treated cultures. We could not assess phosphorylation of intracellular NR2B because multiple bands in the range of NR2B’s molecular weight were detected in both cross-linked and non-cross-linked tissue (data not shown). However, the phospho-specific NR2B-Tyr1472 antibody detected a high molecular weight band in cross-linked tissue that was not present in non-cross-linked tissue; we used the intensity of this band as a measure of surface-expressed phosphorylated NR2B. Treatment with SKF 81297 increased the intensity of this band, and this effect was prevented by genistein (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Protein tyrosine kinase inhibition blocks the effect of D1 receptor stimulation on NMDA receptor surface expression in PFC cultures, measured by BS3 cross-linking. Neurons were treated with vehicle (0.2% DMSO), SKF 81297 (SKF, 1 µM), the tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein (Gen, 50 µM), or Gen+SKF. Total incubation time was 30 min, with SKF 81297 added to vehicle or genistein treated cultures for the last 5 min. After 10 min of cross-linking with BS3, the cells were harvested in lysis buffer. Western analysis of surface bands was conducted as described in the legend to Fig. 4. Genistein blocked the effect of SKF 81297 on surface levels of both NR1 (a) and NR2B (b) (n = 7, Dunn’s test, *p < 0.05). Values are mean ± SEM.

Fig. 6.

D1 receptor stimulation increases surface-expressed immunoreactivity detected with a phospho-specific antibody to NR2B, measured by BS3 cross-linking. Neurons were treated as described in the legend to Fig. 5. SKF 81297 increased immunoreactivity detected in the cell surface band with NR2B-Tyr1472 phospho-specific antibody. Genistein blocked the effect of SKF 81297 (n = 3–5, Dunn’s test, *p < 0.05). Values are mean ± SEM.

Discussion

D1 receptors regulate NMDA receptor surface expression and function

Using immunocytochemical and protein cross-linking assays, we found that stimulation of D1 family receptors on PFC pyramidal neurons increased total cell surface, synaptic and non-synaptic expression of NR1 and NR2B subunits of the NMDA receptor, but not the NR2A subunit. Cell surface expression of NMDA receptors requires assembly of NR1 and NR2 subunits (McIlhinney et al. 1998; Wenthold et al. 2003), so our observation of parallel changes in NR1 and NR2B suggests that D1 receptors regulate the surface expression of NR1/NR2B-containing NMDA receptors. Our results demonstrate a mechanism that may contribute to the ability of D1 receptor stimulation to enhance NMDA receptor currents in rat PFC pyramidal neurons (Zheng et al. 1999; Seamans et al. 2001; Wang and O’Donnell 2001; Gonzalez-Islas and Hablitz 2003; Chen et al. 2004; Tseng and O’Donnell 2004) and human cortical neurons (Cepeda et al. 1999), although other mechanisms involving PKA- and Ca2+-signaling contribute as well (Wang and O’Donnell 2001; Gonzalez-Islas and Hablitz 2003; Chen et al. 2004; Tseng and O’Donnell 2004). Likewise, D1 receptor stimulation increases NMDA receptor surface expression in adult rat striatal tissue and cultured striatal neurons (Dunah and Standaert 2001; Dunah et al. 2004; Hallett et al. 2006; see next paragraph for more discussion), and this may contribute to D1 receptor-mediated enhancement of NMDA receptor transmission in striatal neurons (Cepeda et al. 1993, 1998; Levine et al. 1996; Flores-Hernández et al. 2002) along with mechanisms involving PKA-DARPP-32 and Ca2+ signaling pathways (Hernández-López et al. 1997; Cepeda et al. 1998; Snyder et al. 1998; Flores-Hernández et al. 2002). Direct interactions between D1 and NMDA receptor proteins, as well as NMDA receptor regulation of D1 receptor trafficking, also contribute to functional interactions between these receptors (Cepeda and Levine 2006; Missale et al. 2006). The role of D1-NMDA receptor interactions in plasticity is considered in the last section of the Discussion.

Most of our results in PFC neurons parallel the findings of Dunah and colleagues in striatal neurons (Dunah and Standaert 2001; Dunah et al. 2004; Hallett et al. 2006). In their initial study, which used subcellular fractionation, they showed that incubation of minced striatal tissue from adult rats with a D1 agonist (10 min) produced rapid redistribution of NR1, NR2A and NR2B subunits from light membrane and synaptic vesicle-enriched compartments to synaptosomal membranes, suggesting an increase in their surface expression (Dunah and Standaert 2001). However, NMDA receptor distribution in cortical tissue was not affected by D1 receptor stimulation. D1 receptors are expressed only in certain cortical regions (Bentivoglio and Morelli 2005), so it is not surprising that D1 receptor-mediated effects were not detected in a cortical dissection that was not specific to DA-innervated regions. Indeed, Dunah and Standaert (2001) speculated that low overall density of D1 receptors accounted for their negative results in cortex. In contrast, our results were obtained by selectively examining PFC pyramidal neurons, which have high levels of D1 receptor expression (Bentivoglio and Morelli 2005).

The NMDA receptor subunit redistribution observed by Dunah and Standaert (2001) using subcellular fractionation supported but did not prove an increase in NMDA receptor surface expression. To address this, they showed that D1 agonist treatment increases NR2B surface expression using striatal cultures and immunocytochemical approaches similar to those used herein. Then, using a surface biotinylation assay, they confirmed the increase in NR2B surface expression, and found a smaller effect of D1 receptor stimulation on NR1 and no significant effect on NR2A (Hallett et al. 2006). Our immunocytochemical and protein cross-linking studies similarly found D1 agonist-induced increases in surface expression of NR2B and NR1, but not NR2A. Together, these results suggest that D1 receptor stimulation increases surface expression of NR1/NR2B but not NR1/NR2A receptors in both striatal and PFC neurons. Observation of D1 agonist-induced effects on NR2A distribution in adult striatal tissue using subcellular fractionation (Dunah and Standaert 2001) but not in cultured embryonic striatal neurons using immunocytochemistry (Hallett et al. 2006) could reflect a methodological difference or a developmental shift towards more NR2A (Monyer et al. 1994; Sheng et al. 1994). However, it is clear that the basic phenomenon of D1 agonist-induced potentiation of NMDA receptor transmission exists in the adult brain, both in PFC and striatum (reviewed by Cepeda and Levine 2006; Missale et al. 2006; Castner and Williams 2007).

Tyrosine phosphorylation mediates D1 receptor regulation of NMDA receptor surface expression

Tyrosine phosphorylation of NMDA receptor subunits is an important mechanism for regulating NMDA receptor function (Salter and Kalia 2004; Chen and Roche 2007). For example, increasing protein tyrosine kinase activity enhances NMDA receptor currents (Wang and Salter 1994) and long-term potentiation-inducing stimuli produce a tyrosine kinase-dependent increase in NMDA receptor surface expression (Grosshans et al. 2002). NR2B is the major tyrosine-phosphorylated protein in the postsynaptic density (Moon et al. 1994) and its phosphorylation is strongly implicated in the regulation of NMDA receptor trafficking (below). NR2A, but not NR1, is also tyrosine phosphorylated (Lau and Huganir 1995), but we did not study NR2A phosphorylation because our results indicate that D1 receptors regulate NR2B-containing but not NR2A-containing receptors.

NR2B is phosphorylated by the protein tyrosine kinase Fyn on three tyrosine residues (Tyr1472, Tyr1336 and Tyr1252); of these, the main phosphorylation site is Tyr1472 (Nakazawa et al. 2001). Phosphorylation of NR2B-Tyr1472 stabilizes NMDA receptors at the membrane, while dephos-phorylation by a protein tyrosine phosphatase (striatal-enriched tyrosine phosphatase) is associated with receptor internalization (Lavezzari et al. 2003; Prybylowski et al. 2005; Snyder et al. 2005; Braithwaite et al. 2006). Accordingly, phosphorylation of NR2B-Tyr1472 is associated with expression of NMDA receptor subunits in synaptic membranes and dendritic processes (Goebel et al. 2005; Hallett et al. 2006). The other two phosphorylation sites on NR2B (Tyr1336 and Tyr1252) were not studied. Although Fyn-controlled phosphorylation of Tyr1336 regulates NR2B cleavage by calpain and thus influences NMDA receptor properties, this has not been directly linked to NMDA receptor trafficking (Wu et al. 2007). We are not aware of any evidence linking NR2B-Tyr1252 to NMDA receptor trafficking.

We found that the protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein prevented the D1 agonist-induced increase in NMDA receptor surface expression (synaptic and non-synaptic) on the processes of PFC pyramidal neurons, measured by immunocytochemistry, as well as NMDA receptor surface expression measured with a protein cross-linking assay. Furthermore, using a phospho-specific antibody to NR2B-Tyr1472 in the protein cross-linking assay, we detected an increase in surface expression of phosphorylated NR2B after D1 agonist treatment. These results indicate that tyrosine phosphorylation mediates the D1 receptor-induced increase in NMDA receptor surface expression and strongly implicate NR2B-Tyr1472 as the important site of phosphorylation. A similar mechanism has been described in the striatum. Using minced striatal tissue and subcellular fractionation, Dunah and Standaert (2001) found that redistribution of NMDA receptors to synaptosomal membranes after D1 receptor stimulation was accompanied by increased tyrosine phosphorylation of NR2A and NR2B and blocked by a protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Furthermore, D1 receptor stimulation did not cause NMDA receptor redistribution in striatal tissue from Fyn knockout mice (Dunah et al.. 2004). In cultured striatal neurons, the D1 agonist-induced increase in NR2B surface expression was blocked by genistein and D1 agonist treatment increased immuno-reactivity detected with phospho-specific NR2B-Tyr1472 antibody (although this experiment did not distinguish between surface and intracellular phospho-NR2B; Hallett et al. 2006).

In striatal tissue, the D1 agonist-induced redistribution of NMDA receptors is likely to reflect their trafficking from intracellular compartments to the cell surface, because the observed increase in NMDA receptor subunit levels in the synaptosomal membrane fraction was accompanied by decreased NMDA receptor subunit levels in light membrane and synaptic vesicle-enriched fractions (Dunah and Standaert 2001). Our results suggest that other mechanisms may be contributing in PFC neurons. Thus, while our protein cross-linking studies demonstrated robust increases in NR1 and NR2B surface levels after D1 receptor stimulation, intracellular levels were not significantly altered. Decreased intracellular levels would be expected if the additional surface receptors originated from intracellular sites. Similarly, manipulation of tyrosine phosphorylation in rat hippocampal tissue significantly altered NMDA receptor subunit levels in the synaptosomal membrane fraction without producing statistically significant effects on subunit levels in the intracellular microsomal/light membrane fraction (Goebel et al. 2005). A possible explanation for our results is that NMDA receptors accumulate on the surface after D1 receptor stimulation because tyrosine phosphorylation of NR2B stabilizes them at the surface, decreasing their internalization and degradation. For this to be plausible, normal receptor turnover must be rapid enough that its blockade enables detectable increases in surface expression over the time-frame of our experiments (~15–20 min from addition of SKF 81297 to cell lysis). Supporting this, a significant increase in NMDA receptor currents was observed in cultured cerebellar granule cells within 10 min of interfering with basal NMDA receptor internalization (Prybylowski et al. 2005). Further studies will be required to determine the mechanism accounting for increased surface expression of NR2B-containing receptors in PFC neurons after D1 receptor stimulation.

D1 receptors are positively coupled to PKA, but we found that PKA activation did not alter NMDA receptor surface expression. Likewise, in striatal tissue, D1 receptor-dependent NMDA receptor redistribution to synaptic membrane fractions was not altered by genetic deficiency of the DARPP-32 protein, a critical intermediate in D1 receptor-PKA signaling (Dunah et al. 2004). While these results argue against a role for PKA in D1 receptor-mediated increases in NMDA receptor surface expression, PKA activation over 24–48 h leads to increased NR1 synaptic targeting in cultured hippocampal neurons (Crump et al. 2001). Furthermore, as noted above, D1 receptors enhance NMDA receptor currents through a mechanism requiring PKA and DARPP-32 signaling (Snyder et al. 1998; Wang and O’Donnell 2001; Flores-Hernández et al. 2002; Gonzalez-Islas and Hablitz 2003; Tseng and O’Donnell 2004).

D2 receptors and NMDA receptor surface expression

We found that application of quinpirole (which stimulates all D2 family receptors: D2, D3, and D4) decreased surface expression of NR1 on the processes of PFC pyramidal neurons as measured by immunocytochemistry. A number of studies have reported inhibitory effects of D2 family receptors on NMDA receptor currents in PFC pyramidal neurons (Zheng et al. 1999; Wang et al. 2003; Tseng and O’Donnell 2004). One mechanism underlying this effect may be the activation of GABA interneurons leading to pyramidal cell inhibition (Tseng and O’Donnell 2007). However, consistent with our immunocytochemical findings on NMDA receptor surface expression, Wang et al.. (2003) found that D4 receptor activation reduced NMDA receptor currents in PFC pyramidal neurons, and reduced surface expression of NR1 by triggering NMDA receptor internalization. These effects were mediated by PKA inhibition leading, through PP1 activation, to inhibition of CaMKII (Wang et al. 2003). In contrast to our immunocytochemical findings, protein cross-linking studies failed to show an effect of quinpirole on NR1 surface expression (NR2A and NR2B were also unaffected). It is possible that D1 receptors influence a broader population of NMDA receptors than D2 receptors, and therefore only the D1 receptor effect is detectable with biochemical methods. Stimulation of D2 family receptors with quinpirole did not alter the subcellular distribution of NMDA receptor subunits in adult striatal tissue (Dunah and Standaert 2001) or their surface expression in cultured striatal neurons as detected by surface biotinylation (Hallett et al. 2006).

Possible relevance to plasticity and drug addiction

Coordinated D1 and NMDA receptor signaling is believed to promote persistent activity of PFC cells, which in turn may be critical for learning and memory (Durstewitz and Seamans 2002; Jay 2003; O’Donnell 2003; Otani et al. 2003; Castner and Williams 2007). The D1 receptor-PKA pathway is important for regulating NMDA receptor-dependent plasticity in the PFC both at the synaptic level (Jay et al. 1998; Gurden et al. 2000; Huang et al. 2004; Sun et al. 2005) and the behavioral level (Baldwin et al. 2002). Our results suggest that D1 receptor- and tyrosine kinase-mediated increases in synaptic levels of NMDA receptors may also contribute to facilitation of NMDA receptor-dependent processes in the PFC.

We are particularly interested in the role of glutamatergic mechanisms in neuronal plasticity associated with drug addiction. By increasing DA levels and increasing DA receptor activation, psychomotor stimulants like cocaine can tap into DA receptor-mediated mechanisms for altering glutamate transmission and glutamate-dependent plasticity (Wolf et al. 2004; Kauer and Malenka 2007). The present results raise the possibility that cocaine influences plasticity mechanisms in the PFC by altering NMDA receptor trafficking. This may also occur in other brain regions. In ventral tegmental area DA neurons, acute cocaine produced enhanced NMDA receptor currents by increasing membrane insertion of NR2B-containing NMDA receptors, but this effect required PKA and was not associated with NR2B-Tyr1472 phosphorylation (Schilström et al. 2006). However, in the nucleus accumbens, behavioral sensitization produced by repeated cocaine administration was accompanied by increased NR2B-Tyr1472 phosphorylation (Zhang et al. 2007). NMDA receptor distribution may also be influenced by other drugs of abuse. Behavioral sensitization to methamphetamine was accompanied by enhanced NMDA receptor-mediated currents in striatal slices (Moriguchi et al. 2002), and chronic ethanol exposure increased synaptic targeting of NR1 and NR2B subunits in cultured hippocampal neurons (Carpenter-Hyland et al. 2004). Together, these results suggest that drugs of abuse have in common the ability to enhance NMDA receptor transmission. This may facilitate the neuronal plasticity that focuses behaviors towards drug-seeking.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by DA015835, Independent Scientist Award DA00453, and a NARSAD Distinguished Investigator Award (M.E.W.). We thank Michael Milovanovic for assistance with protein cross-linking assays.

Abbreviations used

- AMPA

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionate

- BS3

bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate

- CaMKII

Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II

- DA

dopamine

- GluR

glutamate receptor

- LTD

long-term depression

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- NR

NMDA receptor

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PFC

prefrontal cortex

- PKA

protein kinase A

- SB

synaptobrevin

- SCH 23390

R-(+)-7-chloro-8-hydroxy-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-3-benzazepine hydrochloride

- SKF 81297

(±)-6-chloro-7,8-dihydroxy-1-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-3-benzazepine hydrobromide

- SP

synaptophysin

- SpcAMPS

Sp-Adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate triethy-lammonium salt hydrate

References

- Archibald K, Perry MJ, Molnar E, Henley JM. Surface expression and metabolic half-life of AMPA receptors in cultured rat cerebellar granule cells. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:1345–1353. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin AE, Sadeghian K, Kelley AE. Appetitive instrumental learning requires coincident activation of NMDA and dopamine D1 receptors within the medial prefrontal cortex. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:1063–1071. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-01063.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentivoglio M, Morelli M. The organization and circuits of mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons and the distribution of dopamine receptors in the brain. In: Dunnett SB, Bentivoglio M, Björklund A, Hökfelt T, editors. Handbook of Chemical Neuroanatomy, Vol. 21: Dopamine. Elsevier, B.V: 2005. pp. 1–106. [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau AC, Wolf ME. Behavioral sensitization to cocaine is associated with increased AMPA receptor surface expression in the nucleus accumbens. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:9144–9151. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2252-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau AC, Reimers JM, Milovanovic M, Wolf ME. Cell surface AMPA receptors in the rat nucleus accumbens increase during cocaine withdrawal but internalize after cocaine challenge in association with altered activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:10621–10635. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2163-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite SP, Adkisson M, Leung J, Nava A, Masterson B, Urfer R, Oksenberg D, Nikolich K. Regulation of NMDA receptor trafficking and function by striatal-enriched tyrosine phosphatase (STEP) Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006;23:2847–2856. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broutman G, Baudry M. Involvement of the secretory pathway for AMPA receptors in NMDA-induced potentiation in hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:27–34. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-00027.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter-Hyland EP, Woodward JJ, Chandler LJ. Chronic ethanol induces synaptic but not extrasynaptic targeting of NMDA receptors. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:7859–7868. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1902-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castner SA, Williams GV. Turning the engine of cognition: A focus on NMDA/D1 receptor interactions in prefrontal cortex. Brain Cogn. 2007;63:94–122. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda C, Levine MS. Where do you think you are going? The NMDA-D1 receptor trap. Science STKE. 2006;333:pe20. doi: 10.1126/stke.3332006pe20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda C, Buchwald NA, Levine MS. Neuromodulatory actions of dopamine in the neostriatum are dependent upon the excitatory amino acid receptor subtypes activated. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:9576–9580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda C, Colwell CS, Itri JN, Chandler SH, Levine MS. Dopaminergic modulation of NMDA-induced whole cell currents in neostriatal neurons in slices: contribution of calcium conductances. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;79:82–94. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda C, Li Z, Cromwell HC, et al. Electrophysiological and morphological analyses of cortical neurons obtained from children with catastrophic epilepsy: dopamine receptor modulation of glutamatergic responses. Dev. Neurosci. 1999;21:223–235. doi: 10.1159/000017402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao SZ, Ariano MA, Peterson DA, Wolf ME. D1 dopamine receptor stimulation increases GluR1 surface expression in nucleus accumbens neurons. J. Neurochem. 2002;83:704–712. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen BS, Roche KW. Regulation of NMDA receptors by phosphorylation. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53:362–368. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Greengard P, Yan Z. Potentiation of NMDA receptor currents by dopamine D1 receptors in prefrontal cortex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:2596–2600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308618100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump FT, Dillman KS, Craig AM. cAMP-dependent protein kinase mediates activity-regulated synaptic targeting of NMDA receptors. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:5079–5088. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05079.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cull-Candy SG, Leszkiewicz DN. Role of distinct NMDA receptor subtypes at central synapses. Science STKE. 2004;255:re16. doi: 10.1126/stke.2552004re16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cull-Candy S, Kelly L, Farrant M. Regulation of Ca2 + - permeable AMPA receptors: synaptic plasticity and beyond. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2006;16:288–297. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingledine R, Borges K, Bowie D, Traynelis SF. The glutamate receptor ion channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 1999;51:7–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunah AW, Standaert DG. Dopamine D1 receptor-dependent trafficking of striatal NMDA receptors to the postsynaptic membrane. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:5546–5558. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05546.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunah AW, Yasuda RP, Wolfe BB. Developmental regulation of tyrosine phosphorylation of the NR2D NMDA glutamate receptor subunit in rat central nervous system. J. Neurochem. 1998;71:1926–1934. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71051926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunah AW, Sirianni AC, Fienberg AA, Bastia E, Schwarzschild MA, Standaert DG. Dopamine D1-dependent trafficking of striatal N-methyl-D-aspartate glutamate receptors requires Fyn protein tyrosine kinase but not DARPP-32. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004;65:121–129. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durstewitz D, Seamans JK. The computational role of dopamine D1 receptors in working memory. Neural Netw. 2002;15:561–572. doi: 10.1016/s0893-6080(02)00049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Hernández J, Cepeda C, Hernández-Echeagaray E, Calvert CR, Jokel ES, Fienberg AA, Greengard P, Levine MS. Dopamine enhancement of NMDA currents in dissociated medium-sized striatal neurons: role of D1 receptors and DARPP-32. J. Neurophysiol. 2002;88:3010–3020. doi: 10.1152/jn.00361.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao C, Wolf ME. Dopamine alters AMPA receptor synaptic expression and subunit composition in dopamine neurons of the ventral tegmental area cultured with prefrontal cortex neurons. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:14275–14285. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2925-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao C, Sun X, Wolf ME. Activation of D1 dopamine receptors increases surface expression of AMPA receptors and facilitates their synaptic incorporation in cultured hippocampal neurons. J. Neurochem. 2006;98:1664–1677. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebel SM, Alvestad RM, Coultrap SJ, Browning MD. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor is enhanced in synaptic membrane fractions of the adult rat hippocampus. Mol. Brain Res. 2005;142:65–79. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Islas C, Hablitz JJ. Dopamine enhances EPSCs in layer II-III pyramidal neurons in rat prefrontal cortex. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:867–875. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00867.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosshans DR, Clayton DA, Coultrap SJ, Browning MD. LTP leads to rapid surface expression of NMDA but not AMPA receptors in adult rat CA1. Nat. Neurosci. 2002;5:27–33. doi: 10.1038/nn779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurden H, Takita M, Jay TM. Essential role of D1 but not D2 receptors in the NMDA receptor-dependent long-term potentiation at hippocampal-prefrontal cortex synapses in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:RC106. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-j0003.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall RA, Soderling TR. Differential surface expression and phosphorylation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits NR1 and NR2 in cultured hippocampal neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 1997a;272:4135–4140. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall RA, Soderling TR. Quantitation of AMPA receptor surface expression in cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience. 1997b;78:361–371. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00525-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall RA, Hansen A, Andersen PH, Soderling TR. Surface expression of the AMPA receptor subunits GluR1, GluR2, and GluR4 in stably transfected baby hamster kidney cells. J. Neurochem. 1997;68:625–630. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68020625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallett PJ, Spoelgen R, Hyman BT, Standaert DG, Dunah AW. Dopamine D1 activation potentiates striatal NMDA receptors by tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent subunit trafficking. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:4690–4700. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0792-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-López S, Bargas J, Surmeier DJ, Reyes A, Galarraga E. D1 receptor activation enhances evoked discharge in neostriatal medium spiny neurons by modulating an L-type Ca2 + conductance. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:3334–3342. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-09-03334.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YY, Simpson E, Kellendonk C, Kandel ER. Genetic evidence for the bidirectional modulation of synaptic plasticity in the prefrontal cortex by D1 receptors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:3236–3241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308280101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T, Moriyoshi K, Sugihara H, et al. Molecular characterization of the family of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:2836–2843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay TM. Dopamine: a potential substrate for synaptic plasticity and memory mechanisms. Prog. Neurobiol. 2003;69:375–390. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay TM, Gurden H, Yamaguchi T. Rapid increase in PKA activity during long-term potentiation in the hippocampal afferent fibre system to the prefrontal cortex in vivo. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1998;10:3302–3306. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauer JA, Malenka RC. Synaptic plasticity and addiction. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:844–858. doi: 10.1038/nrn2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutsuwada T, Kashiwabuchi N, Mori H, et al. Molecular diversity of the NMDA receptor channel. Nature. 1992;358:36–41. doi: 10.1038/358036a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau LF, Huganir RL. Differential tyrosine phosphorylation of Nmethyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:20036–20041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.34.20036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau CG, Zukin RS. NMDA receptor trafficking in synaptic plasticity and neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:413–426. doi: 10.1038/nrn2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavezzari G, McCallum J, Lee R, Roche KW. Differential binding of the AP-2 adaptor complex and PSD-95 to the C-terminus of the NMDA receptor subunit NR2B regulates surface expression. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45:729–737. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00308-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine MS, Altemus KL, Cepeda C, Cromwell HC, Crawford C, Ariano MA, Drago J, Sibley DR, Westphal H. Modulatory actions of dopamine on NMDA receptor-mediated responses are reduced in D1A deficient mutant mice. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:5870–5882. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-18-05870.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinow R, Malenka RC. AMPA receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;25:103–126. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangiavacchi S, Wolf ME. D1 dopamine receptor stimulation increases the rate of AMPA receptor insertion onto the surface of cultured nucleus accumbens neurons through a pathway dependent on protein kinase A. J. Neurochem. 2004;88:1261–1271. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIlhinney RA, Le Bourdelles B, Molnar E, Tricaud N, Streit P, Whiting PJ. Assembly, intracellular targeting and cell surface expression of the human N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits NR1a and NR2A in transfected cells. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:1355–1367. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00121-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missale C, Fiorentini C, Busi C, Collo G, Spano PF. The NMDA/D1 receptor complex as a new target in drug development. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2006;6:801–808. doi: 10.2174/156802606777057562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monyer H, Burnashev N, Laurie DJ, Sakmann B, Seeburg PH. Developmental and regional expression in the rat brain and functional properties of four NMDA receptors. Neuron. 1994;12:529–540. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon IS, Apperson ML, Kennedy MB. The major tyrosine-phosphorylated protein in the postsynaptic density fraction is N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit 2B. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:3954–3958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriguchi S, Watanabe S, Kita H, Nakanishi H. Enhancement of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-mediated excitatory postsynaptic potentials in the neostriatum after methamphetamine sensitization. An in vitro slice study. Exp. Brain Res. 2002;144:238–246. doi: 10.1007/s00221-002-1039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa T, Komai S, Tezuka T, Hisatsune C, Umemori H, Semba K, Mishina M, Manabe T, Yamamoto T. Characterization of Fyn mediated tyrosine phosphorylation sites on GluR epsilon 2 (NR2B) subunit of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:693–699. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008085200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell P. Dopamine gating of forebrain neural ensembles. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2003;17:429–435. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otani S, Daniel H, Roisin MP, Crepel F. Dopaminergic modulation of long-term synaptic plasticity in rat prefrontal neurons. Cereb. Cortex. 2003;13:1251–1256. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhg092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pèrez-Otaño I, Ehlers MD. Homeostatic plasticity and NMDA receptor trafficking. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prybylowski K, Chang K, Sans N, Kan L, Vicini S, Wenthold RJ. The synaptic localization of NR2B-containing NMDA receptors is controlled by interactions with PDZ proteins and AP-2. Neuron. 2005;47:845–857. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolf GD, Cronin CA, Landwehrmeyer GB, Standaert DG, Penney JB, Jr, Young AB. Expression of N-methyl-D-aspartate glutamate receptor subunits in the prefrontal cortex of the rat. Neuroscience. 1996;73:417–427. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter MW, Kalia LV. Src kinases: a hub for NMDA receptor regulation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;5:317–328. doi: 10.1038/nrn1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilström B, Yaka R, Argilli E, et al. Cocaine enhances NMDA receptor-mediated currents in ventral tegmental area cells via dopamine D5 receptor-dependent redistribution of NMDA receptors. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:8549–8558. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5179-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seamans JK, Yang CR. The principal features and mechanisms of dopamine modulation in the prefrontal cortex. Prog. Neurobiol. 2004;74:1–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seamans JK, Durstewitz D, Christie BR, Stevens CF, Sejnowski TJ. Dopamine D1/D5 receptor modulation of excitatory synaptic inputs to layer V prefrontal cortex neurons. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:301–306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011518798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng M, Cummings J, Roldan LA, Jan YN, Jan LY. Changing subunit composition of heteromeric NMDA receptors during development of rat cortex. Nature. 1994;368:144–147. doi: 10.1038/368144a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd JD, Huganir RL. The cell biology of synaptic plasticity: AMPA receptor trafficking. Ann. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2007;23:613–643. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith WB, Starck SR, Roberts RW, Schuman EM. Dopaminergic stimulation of local protein synthesis enhances surface expression of GluR1 and synaptic transmission in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 2005;45:765–779. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder GL, Fienberg AA, Huganir RL, Greengard P. A dopamine/D1 receptor/protein kinase A/dopamine- and cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein (Mr 32 kDa)/protein phosphatase-1 pathway regulates dephosphorylation of the NMDA receptor. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:10297–10303. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10297.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder EM, Nong Y, Almeida CG, et al. Regulation of NMDA receptor trafficking by amyloid-beta. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;5:1051–1058. doi: 10.1038/nn1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Zhao Y, Wolf ME. Dopamine receptor stimulation modulates AMPA receptor synaptic insertion in prefrontal cortex neurons. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:7342–7351. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4603-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Milovanovic M, Zhao Y, Wolf ME. Acute and chronic dopamine receptor stimulation modulates AMPA receptor trafficking in nucleus accumbens neurons co-cultured with prefrontal cortex neurons. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:4216–4230. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0258-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng KY, O’Donnell P. Dopamine-glutamate interactions controlling prefrontal cortical pyramidal cell excitability involve multiple signaling mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:5131–5139. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1021-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng KY, O’Donnell P. D2 dopamine receptors recruit a GABA component for their attenuation of excitatory synaptic transmission in the adult rat prefrontal cortex. Synapse. 2007;61:843–850. doi: 10.1002/syn.20432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, O’Donnell P. D(1) dopamine receptors potentiate nmda-mediated excitability increase in layer V prefrontal cortical pyramidal neurons. Cereb. Cortex. 2001;11:452–462. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.5.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YT, Salter MW. Regulation of NMDA receptors by tyrosine kinases and phosphatases. Nature. 1994;369:233–235. doi: 10.1038/369233a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhong P, Gu Z, Yan Z. Regulation of NMDA receptors by dopamine D4 signaling in prefrontal cortex. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:9852–9861. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-30-09852.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M, Inoue Y, Sakimura K, Mishina M. Distinct distributions of five N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor channel subunit mRNAs in the forebrain. J. Comp. Neurol. 1993;338:377–390. doi: 10.1002/cne.903380305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenthold RJ, Prybylowski K, Standley S, Sans N, Petralia RS. Traffficking of NMDA receptors. Ann. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2003;43:335–358. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.43.100901.135803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf ME, Sun X, Mangiavacchi S, Chao SZ. Psychomotor stimulants and neuronal plasticity. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47S(1):61–79. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HY, Hsu FC, Gleichman AJ, Baconguis I, Coulter DA, Lynch DR. Fyn-mediated phosphorylation of NR2B Tyr-1336 controls calpain-mediated NR2B cleavage in neurons and heterologous systems. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:20075–20087. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700624200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Lee TH, Davidson C, Lazarus C, Wetsel WC, Ellinwood EH. Reversal of cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization and associated phosphorylation of the NR2B and GluR1 subunits of the NMDA and AMPA receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:377–387. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng P, Zhang XX, Bunney BS, Shi WX. Opposite modulation of cortical N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-mediated responses by low and high concentrations of dopamine. Neuroscience. 1999;91:527–535. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00604-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]