Abstract

There is broad acceptance for the idea that during development estradiol ‘organizes’ many aspects of reproductive behavior including partner preferences in the laboratory rat. With respect to partner preference, this idea is drawn from studies where estrogen action was in someway blocked, either through aromatase or estrogen receptor inhibition, during development in male rats. The lack of estrogens neonatally results in a decrease in the male rat’s preference for females. In this study, the effect of early postnatal estradiol treatment on the partner preferences of female rats was examined as a further test of the hypothesis that male-typical partner preference is dependent upon early exposure to estrogens. Our principal finding was that increased postnatal estradiol exposure during development affected partner preference in the expected direction, and this effect was seen under several adult hormonal and behavioral testing conditions. Female rats that received exogenous estradiol during development spent more time with an estrous female and less time with a sexually active male than did cholesterol treated females. The estradiol treatment also disrupted normal female sexual behavior, receptivity, and proceptivity.

Keywords: partner preference behavior, sexual behavior, sexual orientation, estradiol, neonatal development, laboratory rats

INTRODUCTION

There is a critical period in development during which testosterone or its metabolites organize both the brain and behavior of male rats (For reviews, Baum, 1979; Baum, 2006). This is a time of masculinization, the enhancement of male-typical responses, and defeminization, the suppression of female-typical responses (Adkins-Regan, 1988; Bakker, 2003). Testosterone can have its effects by acting directly on the androgen receptor, or by being metabolized into dihydrotestosterone by 5α-reductase (Jaffe, 1969) and into estradiol by aromatase (Ryan et al., 1972). The two metabolites have differential effects on the expression of normal male behavior. Female rats treated neonatally with testosterone show a decrease in receptivity (Barraclough and Gorski, 1962) and in some cases an increase in male typical responses (Mullins and Levine, 1968; Whalen and Edwards, 1967). In addition, neonatal treatment with estradiol benzoate defeminizes both female and neonatally castrated male rats (Baum, 1979).

Adult male partner preference is organized early in development, and it appears that the estrogenic metabolites of testosterone are responsible for the ontogeny of partner preference behavior. Neonatal castration significantly reduces a male’s preference for an estrous female compared to controls (Brand and Slob, 1991); this decrease in preference is prevented (Brand and Slob, 1991) when testosterone is given following castration. However, if dihydrotestosterone, which cannot be aromatized, is given after neonatal castration, it does not prevent the lower preference for the estrous female (Brand and Slob, 1991). On the other hand, postnatal testosterone treatment increases an adult female’s preference to approach an estrous female (Meyerson and Lindstrom, 1973).

Other studies also support the notion that estrogens play a role in the organization of adult partner preference behavior. Blocking estrogen action during development, either through aromatase inhibitors (Bakker et al., 1993a; Bakker et al., 1993b), antiestrogens (Matuszczyk and Larsson, 1995), estrogen receptor knock outs (Rissman et al., 1997; Wersinger and Rissman, 2000; Wersinger et al., 1997) or aromatase gene knock outs (Bakker et al., 2002) results in a decrease in the male rat’s preference for a female.

From these studies, it appears that estradiol plays a significant role in the organization of partner preference behavior in the rat during neonatal development. However, this idea is drawn from studies where estrogen action was in someway blocked in male rats. In the present study, the effect of estrogens was tested directly by treating female rats during the early postnatal period with estradiol and examining their adult partner preference.

METHODS

Animals

Experimental Females

Time-mated pregnant Long-Evans rats (Charles River, Raleigh, NC) were housed individually with ad lib food and water in plastic cages (45.5 × 24 × 21 cm) in a 14:10-hr light-dark cycle with lights on at 01:00. For nest building material thirty, one-inch paper towel strips were given to the dams on gestation day 20. A subset of the female offspring of these dams became the experimental females of this study (see below). On the day of birth, postnatal day (PND) 0, the litter was reduced to four male and four female pups. For litter reductions, the anogenital distance (AGD) for each pup was measured, and since the AGD is shorter in females than in males, the 4 shortest and the 4 longest were retained.

-Stimulus Animals

Sexually experienced, gonadally intact, adult Long Evans rats (Charles River, Raleigh, NC) were used as stimulus animals for the behavioral tests (females at least 60 days old; males at least 90 days old).

Animals were maintained in a facility accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, and all experimental procedures were approved by the Michigan State University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Hormone Treatments

Silastic capsules (Dow Corning; inner diameter 1.47 mm; outer diameter 1.96 mm; length 5 mm) were used to administer estradiol treatments. Estradiol benzoate (Sigma; EB) was mixed with cholesterol (Sigma; C) to achieve 5% and 10% EB to cholesterol mixtures. On PND 1, pups received silastic capsules containing either cholesterol or 5% or 10% EB-cholesterol mixtures. These animals are referred to as C, 5%, and 10% females, respectively. While these estradiol treatments are most likely outside of the physiologically range of estrogen exposure, this study was also designed to provide a positive estradiol control to evaluate the claim from studies in this laboratory that environmental contaminants, such as polychlorinated biphenyls, that have estrogenic effects (Jansen et al., 1993; Nesaretnam et al., 1996; Seegal et al., 2005) affect partner preference in female rats (Cummings et al, in press).

Capsules were implanted subcutaneously (s.c.; one treatment per litter) through a small incision on the back of the animal, while the pups were under ice anesthesia. Following surgery, pups were warmed under a heat lamp until the incision was dry (approximately one hour) and then returned to their mothers. Capsules were left in place for 3 weeks. On PND 21, at weaning, the pups were anesthetized with isoflurane (Isoflo, Abbot Laboratories), and the implants were removed through an incision made near one end of the capsule. The incision was closed with an Auto Clip (Clay Adams) and covered with First Aid Cream (Johnson and Johnson). Pups were then housed with same-sex littermates. Only female pups were used in this experiment.

After animals reached 60 days of age, two females (C, n=16; 5%, n=14; 10%, n=16) from each litter were ovariectomized and implanted with a silastic cholesterol-containing capsule with either 25% or 12.5% EB. The capsules were implanted s.c. while the animals were anesthetized with isoflurane; the incision was closed with an Auto Clip and covered with First Aid Cream. After 4 weeks, the capsules begin to lose efficacy because of connective tissue growth around the capsule (personal observation). The capsules were removed and reimplanted via a new incision in the neck. For some tests (see below), the females were injected s.c. with 0.5 mg progesterone (Sigma; P in sesame oil) four hours prior to data collection. Adult behavioral tests were run after treatment with one of two doses of EB treatment in adulthood and with or without progesterone treatment. This hormonal regime was used to test the females under two naturally occurring hormonal conditions: estrogen alone, typical of early proestrus, and estrogen plus progesterone, typical of late proestrus. Female rats mate during both early proestrus, when estradiol is available but before the surge in progesterone, and during late proestrus, when both ovarian hormones are present (Blaustein, 2008).

Stimulus females were implanted with a silastic capsule containing 25% EB prior to testing but were not ovariectomized. Stimulus females were injected s.c. with 0.5 mg P four hours prior to partner preference and sexual behavior testing.

Maternal Licking and Grooming

Studies have shown that neonatal hormone treatments can alter the display of maternal behavior (Cummings et al., 2005; Moore, 1982), and changes in maternal care can affect the behavior of the offspring (Cameron et al., 2008; Champagne et al., 2001; Champagne and Meaney, 2006; Francis et al., 1999). To determine if the early postnatal treatments caused alterations in maternal care, the maternal licking and grooming of the mothers of the experimental females was analyzed. Maternal behavior was video taped during the last hour of the light phase and the first hour of the dark phase of the light-dark cycle on PND 1, 2, 4, and 6. These recordings, as well as those for all other behavioral tests, were analyzed using The Observer 5.0 (Noldus), a behavioral data acquisition computer program. The amount of time the dam spent licking and grooming the litter was determined.

Behavioral Testing

-Partner Preference

Tests for partner preference were conducted in a 3 chamber apparatus (91 × 61 × 41 cm) made of Plexiglas with a transparent front and opaque sides and inner walls. Each chamber (30 × 61 × 41 cm) had openings in the two inner walls at the back of the apparatus which allowed the experimental animal to move freely among the 3 chambers. One intact male and one sexually receptive female stimulus animal were tethered to a bar at the front end of the two outer chambers using a 25 cm wire fitted with a swivel. The stimulus animals wore a harness that was attached to the bar allowing the experimental animal to make physical contact, but limiting the movement of the stimulus animal to its chamber. The middle chamber had no stimulus animal. Both experimental and stimulus animals were adapted to the apparatus, and stimulus animals were adapted to the harness prior to testing. Behavioral testing took place under dim red light illumination in the middle part of the dark phase of the light-dark cycle.

During the 20-minute partner preference test, the experimental animal could freely move among the three chambers and interact with the stimulus animals. The test was video taped, and the following behaviors were quantified: time spent in each chamber, latency to first enter each chamber, and the occurrence of mounts, intromissions, and ejaculations between the experimental and stimulus animals. Preference scores were calculated by subtracting the duration of time spent in the stimulus male chamber from the duration of time spent in the stimulus female chamber. Therefore, a positive score indicates a preference for the stimulus female. The experimental females were sexually naïve prior to the initial partner preference test.

-Female sexual behavior

When tested for female sexual behavior, a barrier with four holes (4.5 × 4.5 cm) was placed in a Plexiglas observation chamber (46 × 58 × 51 cm), which divided it into a female escape chamber (46 × 22 × 51 cm) and a male chamber (46 × 36 × 51 cm). The holes in the barrier were too small for the male to get through but gave the female free access to both chambers. The tests lasted 30 minutes. Behavioral testing took place under dim red light illumination in the middle part of the dark phase of the light-dark cycle. The test was videotaped, and frequency of male mounts, intromissions and ejaculations were scored, as was the latency to show these behaviors. The latency of the experimental female to approach the male, the amount of time the female spent in male chamber, and sexual receptivity were also recorded. Receptivity was measured using lordosis quotient (LQ), which was calculated for all females who received at least six mounts. For the first 10 mounts (including intromissions or ejaculations) female responses were scored as a 0 (no lordosis) or 1 (lordosis), from which a percentage of number of lordoses per test was calculated. The frequency of exits and latency to return to the male were not measured because the females treated with estradiol neonatally did not receive intromissions or ejaculations from the stimulus male (see Results). Finally, proceptive behaviors, which include hopping and darting, ear wiggling, and approaching the male were scored during the test following progesterone treatment.

-Male-like sexual behavior

Tests for male-like sexual behavior displayed by the experimental females were conducted in a Plexiglas observation chamber (46 × 58 × 51 cm). During the test, the experimental female had unrestricted access to the female stimulus animal. The tests lasted 30 minutes. Behavioral testing took place under dim red light illumination in the middle part of the dark phase of the light-dark cycle. Video recordings of these tests were analyzed to determine frequency of mounts, intromissions, and ejaculatory patterns shown by the experimental females and the latency to show these behaviors.

-Testing Schedule

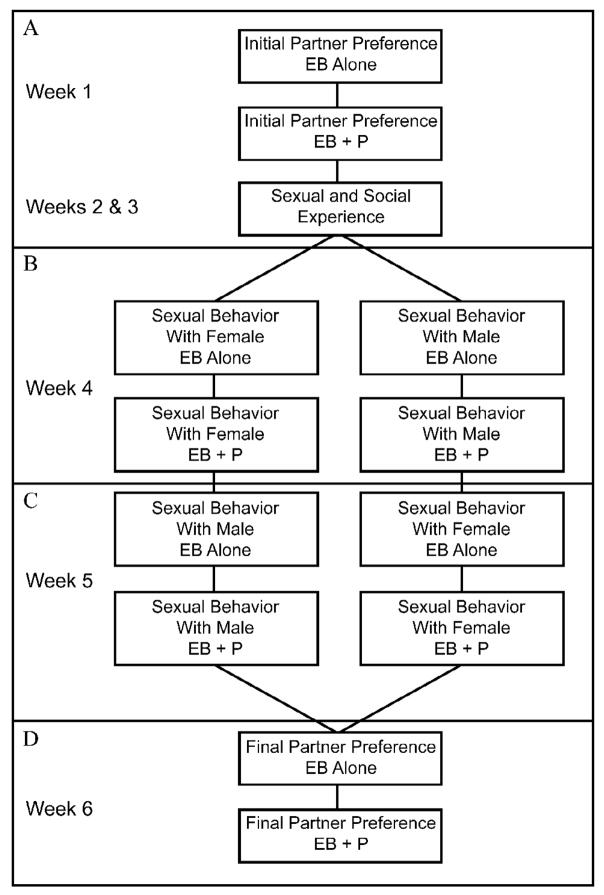

Experimental animals were tested twice a week for 6 weeks (Fig. 1). During the first test each week, the females were tested with only the estradiol treatment (EB alone). For the second test, each female was injected with 0.5 mg progesterone four hours prior to testing (EB + P). The initial partner preference of the female was tested in week 1 (Fig 1A). Each experimental female received sexual and social experience with both male and female stimulus animals during weeks 2 and 3, but data were not collected. During experience weeks, experimental females were partnered with stimulus animals for 30 minutes during which time sexual behavior could occur. During week 4, half of the experimental females were tested for sexual behavior with a male and the other half with a female (Fig 1B). The sex of the stimulus animals was switched for week 5 (Fig 1C). Sexual behavior during weeks 4 and 5 was recorded and scored. In week 6, the female’s final partner preference was evaluated (Fig 1D).

Fig 1.

Behavioral testing schedule for the experimental females receiving neonatal treatments of cholesterol (C, n=16) or estradiol benzoate [EB either 5% (n=14) or 10% (n=16)]. Data were not collected during weeks 2 and 3 during which the animals received sexual/social experience. EB and P represent adult hormone treatments prior to each behavioral test. Note: Although not shown here, there were two doses (12.5% and 25%) of adult EB treatment (see text for more details).

Analysis

Maternal licking and grooming data were analyzed using a 3 × 4 (early postnatal treatment × day) ANOVA with repeated measures on the second factor. The data for the behavioral measures during the partner preference tests were analyzed using a 3 × 2 × 2 × 2 (early postnatal treatment × adult estradiol treatment × progesterone treatment × initial or final test) ANOVA with repeated measures on the third and fourth factors. The data for the behavioral measures during the sexual behavior tests were analyzed separately for female or male behaviors using a 3 × 2 × 2 (early postnatal treatment × adult estradiol treatment × progesterone treatment) ANOVA with repeated measures on the third factor.

For some variables, the data did not meet homogeneity of variance assumptions, even after the prescribed transformations (i.e. square root). For these measures, nonparametric statistics were used for analysis. In these situations, data from the 5% and 10% females were collapsed into an early postnatal-estradiol treated group (EB females) because no significant differences between the two early postnatal estradiol treatments were found for any of the variables analyzed using nonparametric statistical tests. Also, no significant differences were found with the same tests between the two adult estradiol treatments within the early postnatal treatment groups, so data were collapsed across adult estradiol treatments as well. The Mann-Whitney U and the Fisher’s exact probability tests were used for these analyses.

RESULTS

Maternal Licking and Grooming

No significant differences in maternal licking and grooming were seen among treatment groups (p=.292) or days (p=0.078), with no significant interaction (p=0.147; data not shown).

Partner Preference

Effects of Early Postnatal Treatments

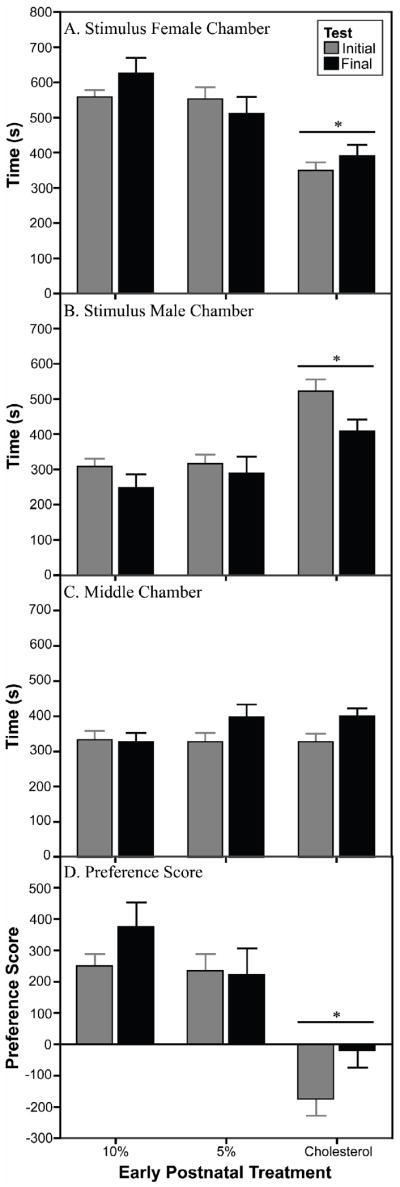

Early postnatal treatment with EB altered the partner preference of the female experimental animals. The 10% and 5% females spent more time in the stimulus female chamber (Fig. 2A; [F(2,40) = 20.3, p<0.001]) and less time in the stimulus male chamber (Fig. 2B; [F(2,40) = 13.7, p<0.001]) than did the C females. Early postnatal treatment did not affect the time the females spent in the middle chamber (Fig. 2C). The 10% and 5% females also showed a positive preference score, indicating a preference for the stimulus female, whereas the C females showed a negative score, indicating a preference for the stimulus male (Fig. 2D; [F(2,40) = 18.7, p<0.001]). Thus, early estradiol treatments reduced the preference for the male and increased the preference for the female, and these effects were seen with no significant interactions between them and those of adult treatments or week of test. Also for all conditions, early postnatal treatments did not affect the latencies to enter the male or female chambers.

Fig. 2.

Duration of time experimental females spent (A) with the stimulus female, (B) with the stimulus male, and (C) in the middle chamber during the partner preference tests. Preference score (D) is calculated as time spent with stimulus female – time spent with stimulus male. C females spend less time with the female and more time with the male compared with 10% and 5% females. *Significantly different from 10% and 5% females, p<0.001. See text for details.

The proportion of experimental females that displayed male-like sexual behavior directed to the stimulus female during partner preference tests did not differ significantly between EB and C females (Fisher’s exact probability tests). However, five out of thirty females (four 10% females and one 5% female) that received early postnatal estradiol showed the full ejaculatory reflex pattern during the preference tests, whereas none of the C females did. The proportion of experimental females that received mounts, intromissions, or ejaculations from the stimulus male differed significantly between early postnatal treatment groups (see Table 1 for the specific comparisons). The stimulus males showed more sexual behavior toward the C females compared to the EB females in both partner preference tests.

Table 1.

Proportion of experimental females that received sexual behavior from the stimulus male during the partner preference tests. C females are more likely than EB females to receive sexual behavior from the stimulus male. Data for both adult EB alone and adult EB + P treatment tests are shown. Data are collapsed across the two adult EB doses.

| Initial Tests | Adult Estradiol Alone | Adult Estradiol and Progesterone | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavior | Mount | Intromission | Mount | Intromission | Ejaculation |

| Cholesterol | 9/16 | 7/16 | 8/16 | 8/16 | 4/16 |

| Estradiol * | 6/30 | 1/30 | 4/30 | 3/30 | 0/30 |

| Final Tests | Adult Estradiol Alone | Adult Estradiol and Progesterone | |||

| Behavior | Mount | Intromission | Mount | Intromission | Ejaculation |

| Cholesterol | 7/16 | 6/16 | 12/16 | 9/16 | 6/16 |

| Estradiol ** | 2/30 | 1/30 | 1/30 | 1/30 | 0/30 |

Significantly different from cholesterol, p<0.05.

Significantly different from cholesterol, p<0.01.

Effects of Experience and Adult Treatments

Across hormone treatments, the average latency to enter the male chamber was significantly shorter for the final test compared to the initial one ( X̄ ± SEM: all measures are in seconds: 31.9 ± 3.4 vs 13.6 ± 1.5; [F(1,40) = 49.6, p<0.001]). Also, for time spent in the middle chamber, comparisons showed that the experimental females spent significantly more time in the middle chamber during the final tests than during the initial tests ( X̄ ± SEM: 374.9 ± 15.8 vs 330.1 ± 13.4; [F(1,40) = 4.8, p=0.035]).

Two measures were affected by progesterone treatment. Across all tests and conditions, the experimental females spent less time with the stimulus female after EB + P treatment compared to after treatment with adult EB alone ( X̄ ± SEM: 517.2 ± 15.9 vs 479.1 ± 17.9; [F(1,40) = 6.0, p=0.019]). In addition, the experimental females spent significantly more time in the middle chamber when treated with EB + P than when treated with adult EB alone (X̄ ± SEM: 378.3 ± 13.4 vs 326.7 ± 13.1; [F(1,40) = 10.0, p=0.003]).

Both the amount of time spent with the male [F(1,40) = 5.5, p=0.024] and latency to enter the female chamber [F(1,40) = 49.6, p<0.001] were affected by a progesterone by test interaction. During the initial partner preference test, females treated with adult EB alone spent more time in the stimulus male chamber than did females treated with EB + P (X̄ ± SEM: 404.1 ± 17.4 vs 361.0 ± 18.6). There was also a decrease in time spent with the male in the adult EB alone treatment group from the initial to final preference test (X̄ ± SEM: 404.1 ± 17.4 vs 306.4 ± 23.1) but no change in the EB + P treatment group. The latency to enter the female chamber was significantly reduced from the initial to the final test when the females received adult EB alone ( X̄ ± SEM: 35.0 ± 4.6 vs 11.6 ± 1.0) but not when progesterone was also given ( X̄ ± SEM: 15.8 ± 1.8 vs 12.4 ± 2.0). Adding progesterone significantly reduced the latency to enter the female chamber, but only for the initial test.

Finally, there were significant adult EB by test interactions for time spent with the female [F(1,40) = 10.8, p=0.002], time spent with the male [F(1,40) = 5.1, p=0.030], and preference score [F(1,40) = 10.0, p=0.003]. Individual comparisons showed that females treated with the high adult EB dose increased the time they spent with the female from initial to final test (X̄ ± SEM: 478.6 ± 20.8 vs 570.4 ± 30.4), but no significant effect of test was found for the females treated with the low adult EB dose ( X̄ ± SEM: 495.9 ± 20.8 vs 447.8 ± 30.4). During the final test, the high adult EB females spent more time in the female chamber than their low dose counterparts. Females treated with the high adult EB dose spent significantly less time with the male from initial to final test (X̄ ± SEM: 392.6 ± 22.6 vs 278.2 ± 31.2), but females receiving the low adult EB dose remained the same ( X̄ ± SEM: 372.5 ± 22.6 vs 352.2 ± 31.2). This lead to an increase in preference score for the females treated with the high adult EB dose (X̄ ± SEM: 86.0 ± 39.1 vs 292.2 ± 57.4) but no change for the low EB dose females (X̄ ± SEM: 123.4 ± 39.1 vs 95.6 ± 57.4).

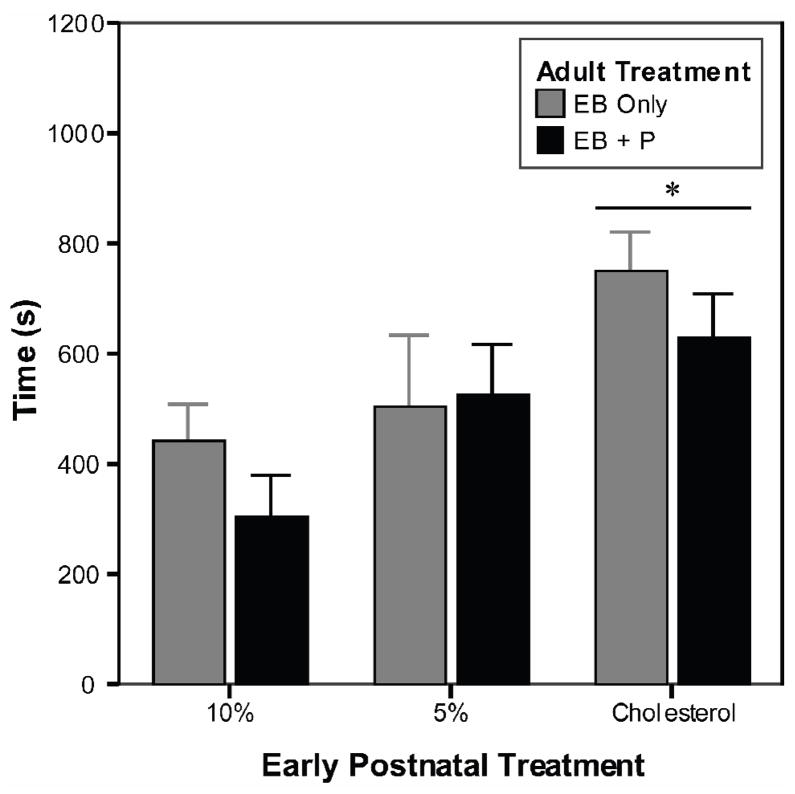

Female Sexual Behavior

The 10% females spent significantly less time in the male area of the testing arena than the C females did (Fig. 3; [F(2,39) = 4.4, p = 0.020]). Also, regardless of other hormone treatments, all females spent less time with the male after EB + P treatment (X̄ ± SEM: 560.0 ± 48.5 vs 486.3 ± 49.3; [F(1,39) = 4.1, p = 0.049]).

Fig 3.

Time experimental females spent in the male chamber during the female sexual behavior tests. Regardless of progesterone treatment, females treated with 10% EB spent significantly less time with the male than did females treated with cholesterol. *Significantly different from 10% females, p=0.02. See text for details.

Non-parametric statistics were used to analyze the remaining measures for the female sexual behavior tests. A Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the behaviors displayed by the stimulus males on tests with EB females (combining the 5% and 10% groups as explained in Methods) and with C females treated as adults with EB alone (combining both adult doses) or with EB + P.

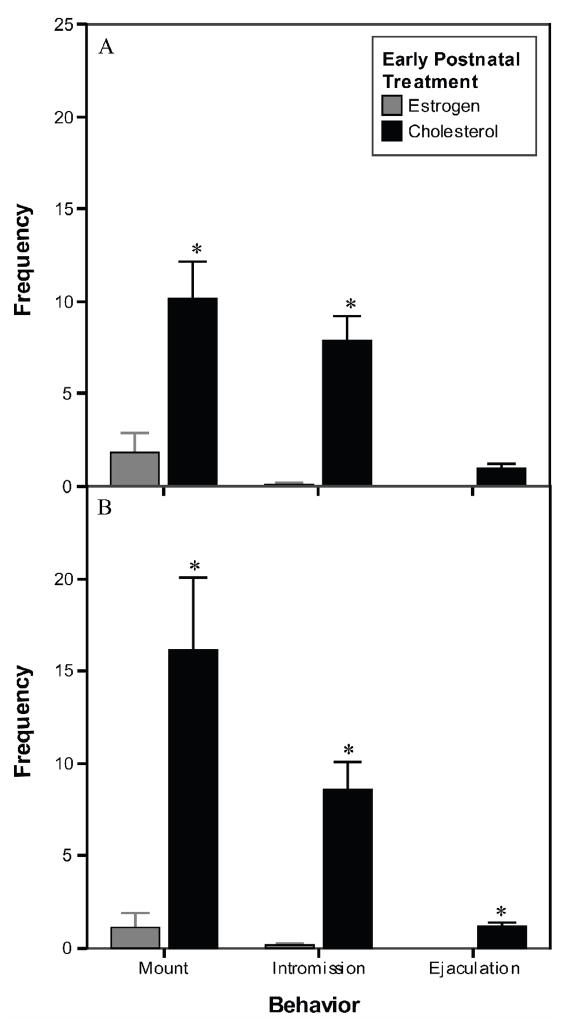

Male mount, intromission, and ejaculation frequencies were significantly affected by the early postnatal treatment of the experimental females. The stimulus males displayed fewer mounts, intromissions, and ejaculations in tests with EB females as compared to C females (Fig. 4). The proportion of experimental females that received mounts, intromissions, and ejaculations by the stimulus male was analyzed using Fisher’s exact probability test. In both tests with and without progesterone, significantly fewer EB females received mounts, intromissions, and ejaculations compared to C females (Table 2).

Fig. 4.

Frequencies of mounts, intromissions, and ejaculations during the female sexual behavior tests. Males showed fewer behaviors when paired with the EB females compared to the C females. (A) Test with adult EB alone treatment. (B) Test with adult EB + P treatment. * Significantly different from EB females, p<0.001. See text for details.

Table 2.

Proportion of experimental females that received sexual behavior from the stimulus male during the female sexual behavior test. C females receives more mounts, intromissions and ejaculations from the stimulus male in both female sexual behavior tests. Data for both adult EB alone and adult EB + P treatment tests are shown. Data are collapsed across the two adult EB doses.

| Adult Estradiol Alone | Adult Estradiol and Progesterone | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavior | Mount | Intromission | Ejaculation | Mount | Intromission | Ejaculation |

| Cholesterol | 14/16 | 12/16 | 10/16 | 14/16 | 14/16 | 12/16 |

| Estradiol* | 6/29 | 3/29 | 0/29 | 6/30 | 1/30 | 0/30 |

Significantly different from cholesterol, p<0.001

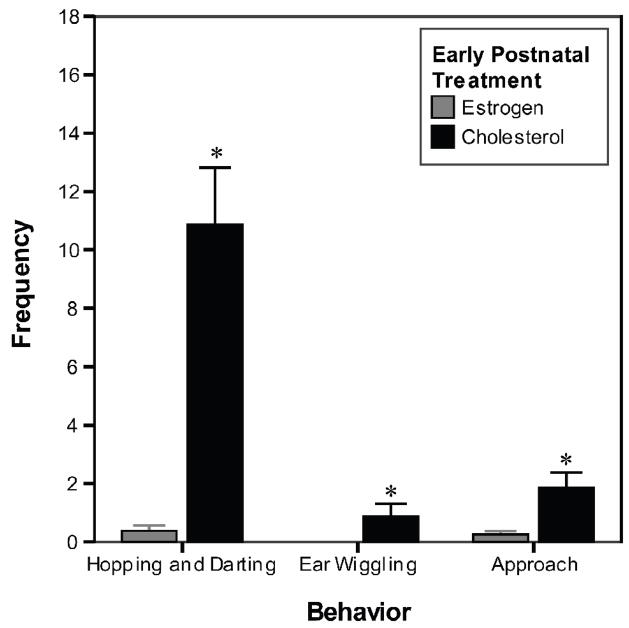

Too few EB females (n = 2) received at least six mounts to allow meaningful statistical comparisons of the LQ scores of EB vs. C females. During tests with adult EB alone treatment, one 10% female received six mounts, but showed no lordosis responses. One 5% female received six mounts during the EB + P test, but showed no lordosis responses. In contrast, all the C females that received at least 6 mounts showed lordosis responses with average LQs of 87% (n=12) for the EB alone (combining both adult doses) tests and 97% (n=14) for the EB + P tests. The data for the proceptive behaviors were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test, which revealed that EB females showed significantly fewer proceptive behaviors than C females did (Fig. 5). Separate statistical tests were used to compare the EB and C females for each specific proceptive behavior.

Fig. 5.

Frequency of proceptive behaviors shown by experimental females during the female sexual behavior test after treatment with adult EB + P. EB females exhibited fewer proceptive behaviors than did C females. * Significantly different from EB females, p<0.01. See text for details.

Male-like Sexual Behavior

Nonparametric tests were used to analyze the data from the male sexual behavior tests. No significant differences were seen between EB and C females for any behavioral measure (Fisher’s exact probability tests). However, five out of thirty females (four 10% females and one 5% females) that received early postnatal EB showed the full ejaculatory pattern during the sexual behavior tests, whereas none of the C females did. Four of these five EB females were the same females that showed ejaculatory patterns during the partner preference tests.

DISCUSSION

The overreaching hypothesis tested by this study was that adult partner preference in the laboratory rat is influenced by the presence of estradiol during early development. This idea stems from studies where blocking estrogen action during development, either through aromatase or estrogen receptor inhibition, results in a decrease in a male rat’s preference for an estrous female compared to control males.

Effects of Early Postnatal Treatments

Our principal finding is that increased postnatal EB exposure during development affects female partner preference. As indicated by the preference scores, female rats that receive exogenous EB during development spent more time with an estrous female and less time with a sexually active male than did C females. These differences in duration were not a result of treatment differences in time spent alone, but were due to differences in the time spent with specific stimulus animals. The early postnatal treatments did not alter the amount of maternal licking and grooming received by the litters; therefore, it is unlikely that the early postnatal treatment group differences were mediated by changes in maternal care. The effect of early EB exposure on partner preference was very robust and evident across different adult hormonal conditions and amounts of sexual experience. These findings are consistent with the results of other studies that indirectly tested the effect of estrogens on partner preference during development using various approaches (Bakker et al., 1993a; Bakker et al., 2002; Bakker et al., 1993b; Brand and Slob, 1991; Matuszczyk and Larsson, 1995; Rissman et al., 1997; Wersinger and Rissman, 2000; Wersinger et al., 1997). Further, recent work from our laboratory also shows that female rats that receive early postnatal exposure to the polychlorinated biphenyl congener 3, 4, 3′, 4′-tetrachlorobiphenyl (PCB 77), which has been shown to have estrogenic effects (Jansen et al., 1993; Nesaretnam et al., 1996; Seegal et al., 2005), exhibit a lower preference for a sexually active stimulus male than do controls (Cummings et al, in press).

Additional support for the idea that early estrogen exposure mediates a preference for females can be found in the human literature. Diethylstilbestrol (DES) is a nonsteroidal synthetic estrogen used through 1970 to decrease the occurrence of miscarriages. Because it was found to increase the risk of cervical cancer in female offspring (Herbst et al., 1971), its clinical use was discontinued. Follow-up studies suggest that DES may have affected sexual orientation of female offspring (but see Titus-Ernstoff et al. (2003) for a report of negative results). When interviewed regarding their sexual orientation, DES-exposed women are found to have a higher incidence of bisexuality or homosexuality than non-exposed women (Ehrhardt et al., 1985; Meyerbahlburg et al., 1995).

In the present study, early postnatal EB treatment also affected the sexual behavior of the female rats. The 10% EB dose reduced the time the female spent with the male during the sexual behavior test, and none of the females that received early postnatal EB showed lordosis in response to male mounts. This effect on female receptivity is in agreement with other studies showing that neonatal EB treatment decreases the frequency of lordosis in females and neonatally castrated males (Levine and Mullins, 1964; Whalen and Edwards, 1967; Whalen and Nadler, 1963). Also, perinatal treatment with the aromatase inhibitor 1,4,6 androstatriene-3,17-dione (ATD) enhances the tendency of male rats to show lordosis after castration and treatment with ovarian hormones in adulthood (Clemens and Gladue, 1978; McEwen et al., 1977; Whalen et al., 1986), and perinatal treatment with antiestrogen, but not antiandrogen, increases the frequency of lordosis in male rats (Matuszczyk and Larsson, 1995).

In both the partner preference tests and the female sexual behavior test, the EB females (combined 5% and 10% groups) were less likely than C females to receive mounts, intromissions, or ejaculations from the stimulus male. This reduced interest by the males for the EB females could reflect multiple factors, which are not mutually exclusive. The EB females could be less proceptive, they could be less attractive to the males, or they could be actively avoiding the males, any of which would lead to decreased sexual interest and sexual behavior by the stimulus male. Proceptive behaviors were measured during the female sexual behavior test after the experimental females had received adult EB + P treatment. The EB females showed significantly fewer instances of ear wiggling, hopping and darting, and approaches to the stimulus male compared to C females. Attractivity was not measured in this study but could also be an explanation for the low frequency of male behaviors directed toward the EB females. Stimulus males may find the EB females less attractive than C females resulting in the male showing less sexual behavior. Further support for this idea comes from the fact that the differential behavior of the male was also seen during tests when only adult EB was given, which is a hormonal condition associated with very little proceptivity even for control females (Frye et al., 1998). Finally, avoidance behaviors were not measured, but the lack of sexual interactions with the male may be due to the EB females actively avoiding contact with the males.

There were no significant differences between EB females and C females in the display of male sexual behavior. The two treatments did not differ in the frequency of mounts or intromission patterns shown when placed with an estrous stimulus female. Although the expression of ejaculation patterns did not reach statistical significance, it is interesting that a total of six females treated early postnatally with EB showed at least one ejaculation pattern during either the partner preference or male sexual behavior test. Four 10% females showed ejaculatory patterns in both tests, while two 5% females showed ejaculation patterns in one of the tests. None of the C females showed ejaculation patterns in any of the tests. Despite not reaching statistical significance, this effect agrees with previous findings that show estrogen may play a role in the expression of ejaculatory patterns. Brand et al. (1991) found that compared with control males, fewer neonatally ATD-treated males ejaculate when paired with an estrous stimulus female. A similar decrease in male sexual behavior is also seen after neonatal treatment with an antiestrogen (Matuszczyk and Larsson, 1995).

Effects of Experience and Adult Treatments

Although the alteration of adult female partner preference and sexual behavior by early postnatal EB treatment did not change across adult hormone or testing conditions, some effects of adult treatment and experience were evident. The most salient of these effects was that all experimental females, regardless of hormonal condition, decreased their latency to enter the male chamber and increased the time spent in the middle chamber from the initial to the final partner preference test. This effect may be due to the sexual and social experience the females received during the sexual behavior tests since sexual experience can play a role in the display of partner preference (Dejonge et al., 1986; Matuszczyk and Larsson, 1991; Slob et al., 1987).

Also, compared to treatment with EB alone, adult EB + P treatment decreased the amount of time the experimental females spent within the stimulus animals’ chambers during the partner preference tests, while increasing the time spent in the middle chamber. In addition, EB + P treatment decreased the amount of time the experimental females spent in the male chamber during the female sexual behavior test compared to treatment with EB alone. Although these effects were seen across all the early postnatal treatment groups, the mechanism behind these effects may be different for C versus EB females, since sexual behavior is facilitated by progesterone only in the case of the C females. Thus, in the C females the addition of progesterone treatment increases sexual receptivity and the likelihood of a female-paced copulatory bout (Dejonge et al., 1986; Frye et al., 1998). During a female-paced sexual behavior test, a receptive female would approach the stimulus male, be mounted, and then leave the male chamber and enter the escape chamber leading to a decrease in the overall time spent with the male. Similarly, in a partner preference test, a receptive female would enter the male chamber, be mounted, and then move into the middle chamber, thereby decreasing the time spent in the stimulus chambers and increasing the duration in the middle chamber. Therefore, the differences seen for both tests of sexual behavior and partner preferences between the EB and the EB + P conditions can be explained for the C females as a consequence of the enhanced receptivity induced by the addition of progesterone in this group.

While enhanced receptivity and the pacing of copulation may account for the increase in time the C females spent in the escape chambers when given progesterone in addition to EB, a similar explanation cannot be made for the females that received early postnatal EB, since they did not receive any intromissions or ejaculations, and evidently were not pacing copulatory bouts. Perinatal steroid treatments interfere with the activation of female sexual behavior by progesterone (Clemens, 1970; Davidson and Levine, 1969). But the reduction in the amount of time the EB females in the current study spent with the stimulus animals following adult EB + P treatment may reflect other actions of progesterone different from the facilitation of female receptivity. For example, progesterone has been shown to have anesthetic or tranquilizing effects (Bixo and Backstrom, 1990; Merryman et al., 1954; Selye, 1941) that use a progesterone receptor (PR)-independent mechanism of action (Reddy and Apanites, 2005). Such effects might easily account for the EB female’s tendency to stay in the middle chamber in the partner preference test and the escape chamber in the sexual behavior test in the absence of progesterone-induced sexual receptivity.

Conclusion

The most robust finding of this study was that early postnatal EB treatment alters female partner preference and sexual behavior. Estradiol seems to have a masculinizing and defeminizing effect. Females treated with early postnatal EB preferred to spend more time with an estrous female and less time with a sexually active male than did C females. Also, EB females showed less female sexual behavior, receptivity, proceptivity, and possibly attractivity to the males, while occasionally showing ejaculatory patterns when placed with an estrous female. These findings support the claim that estrogens during the postnatal critical period plays a role in the development of male partner preference and sexual behavior.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an NIH grant (RDK069991A) to L. Clemens. We would like to thank Erinn Laimon-Thomson, Melannie Richmond, and Erin Gruley for suggestions and technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adkins-Regan E. Sex-hormones and sexual orientation in animals. Psychobiology. 1988;16:335–347. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker J. Sexual differentiation of the neuroendocrine mechanisms regulating mate recognition in mammals. Journal Of Neuroendocrinology. 2003;15:615–621. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker J, et al. Hormonal regulation of adult partner preference behavior in neonatally atd-treated male rats. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1993a;107:480–487. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.3.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker J, et al. Sexual partner preference requires a functional aromatase (cyp19) gene in male mice. Hormones And Behavior. 2002;42:158–171. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2002.1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker J, et al. Organization of partner preference and sexual-behavior and its nocturnal rhythmicity in male-rats. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1993b;107:1049–1058. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.6.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barraclough CA, Gorski RA. Studies on mating behaviour in androgen-sterilized female rat in relation to hypothalamic regulation of sexual behaviour. Journal Of Endocrinology. 1962;25:175–182. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0250175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum MJ. Differentiation of coital behavior in mammals - comparative-analysis. Neuroscience And Biobehavioral Reviews. 1979;3:265–284. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(79)90013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum MJ. Mammalian animal models of psychosexual differentiation: When is ‘translation’ to the human situation possible? Hormones And Behavior. 2006;50:579–588. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bixo M, Backstrom T. Regional distribution of progesterone and 5-alpha-pregnane-3,20-dione in rat-brain during progesterone-induced anesthesia. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1990;15:159–162. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(90)90025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaustein JD. Neuroendocrine regulation of feminine sexual behavior: Lessons from rodent models and thoughts about humans. Annual Review Of Psychology. 2008;59:93–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand T, et al. Adult partner preference and sexual-behavior of male-rats affected by perinatal endocrine manipulations. Hormones And Behavior. 1991;25:323–341. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(91)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand T, Slob AK. Neonatal organization of adult partner preference behavior in male-rats. Physiology & Behavior. 1991;49:107–111. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(91)90239-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron NM, et al. Maternal influences on the sexual behavior and reproductive success of the female rat. Hormones And Behavior. 2008;54:178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne F, et al. Naturally occurring variations in maternal behavior in the rat are associated with differences in estrogen-inducible central oxytocin receptors. Proceedings Of The National Academy Of Sciences Of The United States Of America. 2001;98:12736–12741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221224598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne FA, Meaney MJ. Stress during gestation alters postpartum maternal care and the development of the offspring in a rodent model. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;59:1227–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens LG. Androgen and development of progesterone responsiveness in male and female rats. Physiology & Behavior. 1970;5:673–678. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(70)90229-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens LG, Gladue BA. Feminine sexual-behavior in rats enhanced by prenatal inhibition of androgen aromatization. Hormones And Behavior. 1978;11:190–201. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(78)90048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JA, et al. A cross-fostering analysis of the effects of pcb 77 on the maternal behavior of rats. Physiology & Behavior. 2005;85:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JM, Levine S. Progesterone and heterotypical sexual behaviour in male rats. Journal Of Endocrinology. 1969;44:129–130. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0440129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejonge FH, et al. The influence of estrogen, testosterone and progesterone on partner preference, receptivity and proceptivity. Physiology & Behavior. 1986;37:885–891. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(86)90209-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt AA, et al. Sexual orientation after prenatal exposure to exogenous estrogen. Archives Of Sexual Behavior. 1985;14:57–77. doi: 10.1007/BF01541353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis D, et al. Nongenomic transmission across generations of maternal behavior and stress responses in the rat. Science. 1999;286:1155–1158. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, et al. The neurosteroids, progesterone and 3 alpha,5 alpha-thp, enhance sexual motivation, receptivity, and proceptivity in female rats. Brain Research. 1998;808:72–83. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00764-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst AL, et al. Adenocarcinoma of vagina - association of maternal stilbestrol therapy with tumor appearance in young women. New England Journal Of Medicine. 1971;284:878. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197104222841604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe RB. Testosterone metabolism in target tissues - hypothalamic and pituitary tissues of adult rat and human fetus, and immature rat epiphysis. Steroids. 1969;14:483–498. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(69)80043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen HT, et al. Estrogenic and antiestrogenic actions of pcbs in the female rat - invitro and invivo studies. Reproductive Toxicology. 1993;7:237–248. doi: 10.1016/0890-6238(93)90230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine S, Mullins R. Estrogen administered neonatally affects adult sexual behavior in male and female rats. Science. 1964;144:185–187. doi: 10.1126/science.144.3615.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matuszczyk JV, Larsson K. Role of androgen, estrogen and sexual experience on the female rats partner preference. Physiology & Behavior. 1991;50:139–142. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(91)90510-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matuszczyk JV, Larsson K. Sexual preference and feminine and masculine sexual behavior of male rats prenatally exposed to antiandrogen or antiestrogen. Hormones and Behavior. 1995;29:191–206. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1995.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, et al. Aromatization - important for sexual differentiation of neonatal rat-brain. Hormones And Behavior. 1977;9:249–263. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(77)90060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merryman W, et al. Progesterone anesthesia in human subjects. Journal Of Clinical Endocrinology And Metabolism. 1954;14:1567–1569. doi: 10.1210/jcem-14-12-1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerbahlburg HFL, et al. Prenatal estrogens and the development of homosexual orientation. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Meyerson BJ, Lindstrom LH. Sexual motivation in the female rat. A methodological study applied to the investigation of the effect of estradiol benzoate. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica Suppl. 1973;389:1–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CL. Maternal-behavior of rats is affected by hormonal condition of pups. Journal Of Comparative And Physiological Psychology. 1982;96:123–129. doi: 10.1037/h0077866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins RF, Levine S. Hormonal determinants during infancy of adult sexual behavior in female rat. Physiology & Behavior. 1968;3:333–338. [Google Scholar]

- Nesaretnam K, et al. 3,4,3′,4′-tetrachlorobiphenyl acts as an estrogen in vitro and in vivo. Molecular Endocrinology. 1996;10:923–936. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.8.8843409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy DS, Apanites LA. Anesthetic effects of progesterone are undiminished in progesterone receptor knockout mice. Brain Research. 2005;1033:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rissman EF, et al. Estrogen receptor function as revealed by knockout studies: Neuroendocrine and behavioral aspects. Hormones And Behavior. 1997;31:232–243. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1997.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan KJ, et al. Estrogen formation in brain. American Journal Of Obstetrics And Gynecology. 1972;114:454–460. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(72)90204-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seegal RF, et al. Coplanar pcb congeners increase uterine weight and frontal cortical dopamine in the developing rat: Implications for developmental neurotoxicity. Toxicological Sciences. 2005;86:125–131. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selye H. Anesthetic effect of steroid hormones. Proceedings Of The Society For Experimental Biology And Medicine. 1941;46:116–121. [Google Scholar]

- Slob AK, et al. Homosexual and heterosexual partner preference in ovariectomized female rats - effects of testosterone, estradiol and mating experience. Physiology & Behavior. 1987;41:571–576. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(87)90313-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titus-Ernstoff L, et al. Psychosexual characteristics of men and women exposed prenatally to diethylstilbestrol. Epidemiology. 2003;14:155–160. doi: 10.1097/01.EDE.0000039059.38824.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wersinger SR, Rissman EF. Oestrogen receptor alpha is essential for female-directed chemo-investigatory behaviour but is not required for the pheromone-induced luteinizing hormone surge in male mice. Journal Of Neuroendocrinology. 2000;12:103–110. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2000.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wersinger SR, et al. Masculine sexual behavior is disrupted in male and female mice lacking a functional estrogen receptor alpha gene. Hormones And Behavior. 1997;32:176–183. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1997.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen RE, Edwards DA. Hormonal determinants of the development of masculine and feminine behavior in male and female rats. The Anatomical Record. 1967;157:173–180. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091570208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen RE, et al. Lordotic behavior in male-rats - genetic and hormonal-regulation of sexual-differentiation. Hormones And Behavior. 1986;20:73–82. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(86)90030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen RE, Nadler RD. Suppression of development of female mating behaviour by estrogen administered in infancy. Science. 1963;141:273–274. doi: 10.1126/science.141.3577.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]