Abstract

Background

Keratins 8 and 18 (K8/K18) are important hepatoprotective proteins. Animals expressing K8/K18 mutants exhibit a marked susceptibility to acute/subacute liver injury. K8/K18 variants predispose to human end-stage liver disease and associate with fibrosis progression during chronic hepatitis C infection.

Aims

We sought direct evidence for a keratin mutation-related predisposition to liver fibrosis using transgenic mouse models, since the relationship between keratin mutations and cirrhosis is based primarily on human association studies.

Methods

Mouse hepatofibrosis was induced by carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) or thioacetamide. Nontransgenic mice, or mice that overexpress either human Arg89-to-Cys (R89C mice) or wild-type K18 (WT mice) were used. The extent of fibrosis was evaluated by quantitative real time RT-PCR of fibrosis-related genes, liver hydroxyproline measurement, and Sirius red and collagen immunofluorescence staining.

Results

Compared to control animals, CCl4 led to similar liver fibrosis but increased injury in K18 R89C mice. In contrast, thioacetamide caused more severe liver injury and fibrosis in K18 R89C as compared to WT and nontransgenic mice and resulted in increased mRNA levels of collagen, TIMP1, MMP2 and MMP13. Analysis in nontransgenic mice showed that thioacetamide and CCl4 have dramatically different molecular expression-responses involving cytoskeletal and chaperone proteins.

Conclusion

Overexpression of K18 R89C predisposes transgenic mice to thioacetamide- but not CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. Differences in the keratin mutation-associated fibrosis response among the two models raise the hypothesis that keratin variants may preferentially predispose to fibrosis in unique human liver diseases. Findings herein highlight distinct differences in the two widely used fibrosis models.

Keywords: actin, carbon tetrachloride, chaperones, cirrhosis, cytoskeleton, Hsp27, Hsp60, Hsp70, intermediate filaments, keratin 18, keratin mutation

INTRODUCTION

Intermediate filaments (IFs), actin microfilaments and tubulin microtubules are the three major cytoskeletal systems found in eukaryotic cells.1 Among these systems, IFs are the most heterogeneous and comprise >50 proteins that are cell-specific and whose mutations associate with a wide range of tissue-selective human diseases.1,2 For example, desmin and neurofilaments are the major cytoplasmic IF proteins in muscle and neuronal cells, respectively,3,4 whereas lamins are ubiquitously-expressed nuclear IFs.5,6 All IFs share a common structure consisting of a conserved α-helical “rod” domain, which is flanked by non-α-helical N-terminal “head” and C-terminal “tail” domains.3 Keratins are the IFs of epithelial cells, and are divided into type-I keratins 9–20 (K9–K20) and type-II keratins 1–8 (K1–K8).7,8 All epithelial cells express unique keratin complements consisting of at least one type-I and one type-II keratin which assemble into obligate non-covalent heteropolymers9 that contribute to partner keratin protein stability.10,11 Examples of cell-preferential keratin pairs include keratinocyte K5/K14 (basally) and K1/K10 (suprabasally), and glandular epithelial K8/K18 with variable levels of K7/K19/K20 depending on the cell type.7,12

IFs are intrinsically dynamic structures that undergo continuous remodeling to accommodate changing cellular needs.4,13,14 IF dynamics are modulated by posttranslational modifications, particularly phosphorylation,15 and by IF-associated proteins.16 The major in vivo phosphorylation sites of human K8/K18 are K8 Ser73/Ser431 and K18 Ser33/Ser52, which undergo increased or decreased phosphorylation in a site-specific manner during apoptosis, mitosis and different stresses.15 Site-specific blocking of keratin phosphorylation in transgenic mice showed that K8/K18 phosphorylation plays important roles in cell cycle progression, sensitivity to apoptosis, and predisposition to toxin-mediated liver injury.15 In chronic liver diseases, K8/K18 phosphorylation status serves as a marker of liver disease progression.17

Adult hepatocytes are unique in that they express K8/K18 as their only cytoplasmic IFs.1 This simple keratin composition is likely responsible for the primary hepatic phenotype of several transgenic mouse models either lacking or overexpressing mutant K8/K18.18 For example, overexpression of human K18 Arg-89-Cys (R89C) causes a mild chronic hepatitis but a marked predisposition to toxin-induced acute liver injury and to apoptosis.19,20 The K18 Arg89 residue was targeted for animal model development since it is highly conserved and is mutated in ~40% of epidermal keratin diseases.21 Findings in these mice led to the search then identification of several K8/K18 variants as a risk factor for end-stage liver disease18,22,23 and for liver disease progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C.18,24

Although extensive animal studies support the importance of K8/K18 in predisposing to acute and subacute liver injury,18 the relationship between K8/K18 mutation and the development of liver cirrhosis is based solely on human association studies.18,22–24 Therefore, we undertook this study and used the two well-established fibrosis models25–28 of carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) and thioacetamide (TAA) to directly address whether keratin mutation affects predisposition to fibrosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal experiments

We used the well-described heterozygous transgenic mice that overexpress the human (h) wild-type (WT) or R89C K18 genes using the endogenous K18 promoter to maintain tissue-specific expression.19,20,29 All mice are in an FVB genetic background, and transgenic mouse genotyping was done as described.30 The copy number of the mutant K18 transgene is slightly less than the WT, so any observed effects are not due to transgenic overexpression.29 Also, expression of the h-transgene (85% identity to mouse K18 protein) down-regulates endogenous mouse K18 to maintain similar overall keratin levels to nontransgenic mice.31

In order to induce liver fibrosis, two-months old age- and sex-matched mice (mainly females) were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 0.2–1ml CCl4/kg mouse weight diluted in olive oil (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) or TAA, (100 mg/kg mouse weight diluted in distilled water; Sigma) and sacrificed 72h and 48h after the last injection, respectively. In both cases, 100μl/25g mouse weight was injected. CCl4 was administered twice/week for 8 weeks, whereas TAA was injected 3x/week for 6 weeks. Mice were euthanized using CO2 inhalation. Blood was collected by intracardiac puncture and stored overnight (4 °C). Serum was then collected and used to measure alanine aminotransferase (ALT [IU/L]), alkaline phosphatase (ALP [IU/L]), and total bilirubin (mg/dL). Livers were removed, weighed and divided into four pieces for: fixation in 10% formaldehyde (histological staining); embedding over dry ice followed by sectioning (immunofluorescence staining); flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen (biochemical analysis); or submerging in RNAlater™ Stabilization Reagent (Qiagen; Valencia, CA) and storage at −80 °C (real time RT-PCR). Non-treated, four-months old female mice were used as controls. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee at the Palo Alto VA.

Antibodies

We used antibodies (Ab) directed to: K8/18 (Ab-8592), K18 (Ab-4668), K8 pS431 (Ab-2D6) and K18 pS33 (Ab-8250);32 Hsp60 (Ab-LK2), α-tubulin (Ab-DM1A), and β-actin (Ab-ACTN05) from Labvision (Fremont, CA); heat shock protein (Hsp)-27 (Ab-sc-1049) and Hsp70 (Ab-sc1060) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); K8 (Ab-Troma-1) (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank; Iowa City, IA); and α1(I) collagen (Ab-LF67).33

Histological and statistical analysis

The extent of liver pathology was evaluated using an established scoring system.34 Picro-sirius red (PSR) staining was used to grade the extent of fibrosis and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections to asses the remaining histological parameters. An average score was generated (Table 1) and values are shown as means ±SE for histological parameters and as means ±SD otherwise. Statistical analysis was performed using two-tailed Student’s t-test and p<0.05 was considered significant.

Table 1.

Serum analysis, histological analysis and liver weight of CCl4- and TAA-treated mice

| FVBa | K18 WT | K18 R89C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCl4 model | |||

| # of mice survived/total | 7/8 | 7/8 | 8/8 |

| Liver weight/body weight (%) | 4.9±0.4 | 4.9±0.4 | 5.2±0.5 |

| Bilirubin | 0.6±0.6 | 0.7±0.6 | 0.7±0.6 |

| ALT | 90±22 | 102±38 | 123±55 |

| ALP | 60±14 | 63±15 | 60±8 |

| Portal/Periportal activity | 1.2±1.0 | 0.9±0.6b | 1.9±0.6b |

| Lobular activity | 2.0±0.8 | 1.8±0.5b | 2.6±0.4b |

| Fibrosis | 1.4±0.4 | 1.6±0.5 | 1.6±0.3 |

| TAA model | |||

| # of mice survived/total | 8/8 | 8/8 | 5/7 |

| Liver weight/body weight (%) | 5.9±0.4c | 7.6±0.8c,d | 8.7±0.5d |

| Bilirubin | 0.4±0.3 | 0.6±0.3 | 0.6±0.2 |

| ALT | 455±267 | 396±174 | 385±50 |

| ALP | 131±23 | 176±50c | 78±17c |

| Portal/Periportal activity | 0.5±0.5e | 1.5±1.2e,f | 2.8±0.4f |

| Lobular activity | 2.2±0.4 | 2.6±0.6 | 2.5±0.5 |

| Fibrosis | 0.8±0.5 | 0.8±0.5g | 1.6±0.2g |

Normal value for untreated FVB mice for %Liver-to-body weight is 5.1±0.3. The histological and fibrosis scoring ranged from 0 (normal) to 4 (most severe) as described.34

p=0.01

p=0.001

p=0.02

p=0.06

p=0.02

p=0.004 (when comparing the indicated strains)

Immunofluorescence staining and quantitative real time RT-PCR

6-μm thick frozen liver sections were fixed with acetone followed by immunofluorescence staining as described.32 Stained sections were analyzed using a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope (Zeiss MicroImaging; Thornwood, NY). Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed using an oligo-dT method and specific primers (Supplemental Table 1).35

Protein analysis

Total liver homogenates were prepared using a Dounce homogenizer and 3% SDS-containing sample buffer, then diluted to a desired protein concentration using 4x reducing SDS-containing sample buffer. A highly enriched liver keratin fraction was generated by a standard procedure that involves sequential collection of the Triton-insoluble fraction then extraction using a high salt buffer as described.32 This high salt extraction method recovers more than 95% of the tissue/cell keratin fraction and yields a relatively pure keratin preparation.32 Proteins were separated using 10% SDS-PAGE and visualized by Coomassie staining or immunoblotting.32 Antigen-antibody complexes were detected with an ECLplus Detection kit (PerkinElmer; Boston, MA).

Hydroxyproline assay

Liver tissue hydroxyproline content was measured colorimetrically.36,37 Briefly, liver tissues were weighed and homogenized in distilled water using a polytron homogenizer. Homogenates were hydrolyzed in 6N HCl (110 °C, 18 h) then filtered and evaporated by speed vacuum centrifugation. The sediments or 0.5–20 μg of trans-4-hydroxy-L-proline standards (Sigma) were dissolved in 50 μl of distilled water, mixed with 450 μl of 56mM chloramines-T in acetate-citrate buffer (pH 6.5), and incubated for 25 min at room temperature. Ehrlich’s solution (500 μl) containing 1.0 M p-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde in n-propanol/perchloric acid (2:1 v/v; Sigma-Aldrich) was then added and incubated (65 °C, 20 min), followed by measuring the absorbance (562 nm). The results are expressed as means ±SD and statistical significance was assessed using Student’s t-test.

RESULTS

CCl4 treatment leads to similar fibrosis in K18 WT and K18 R89C mice

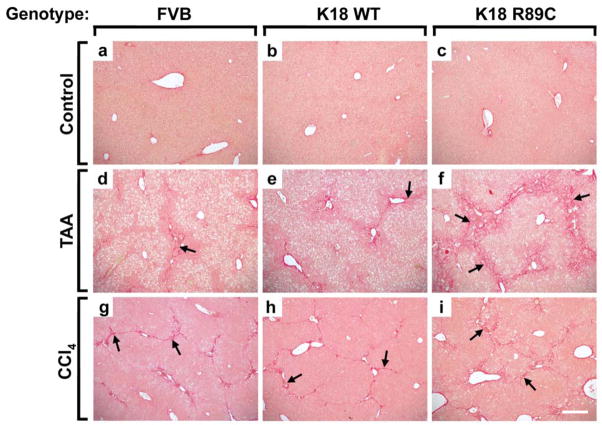

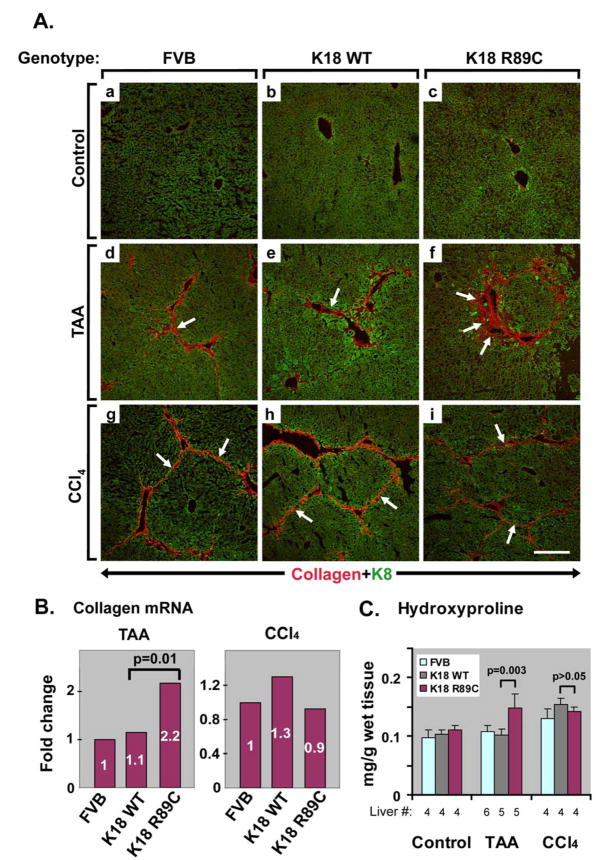

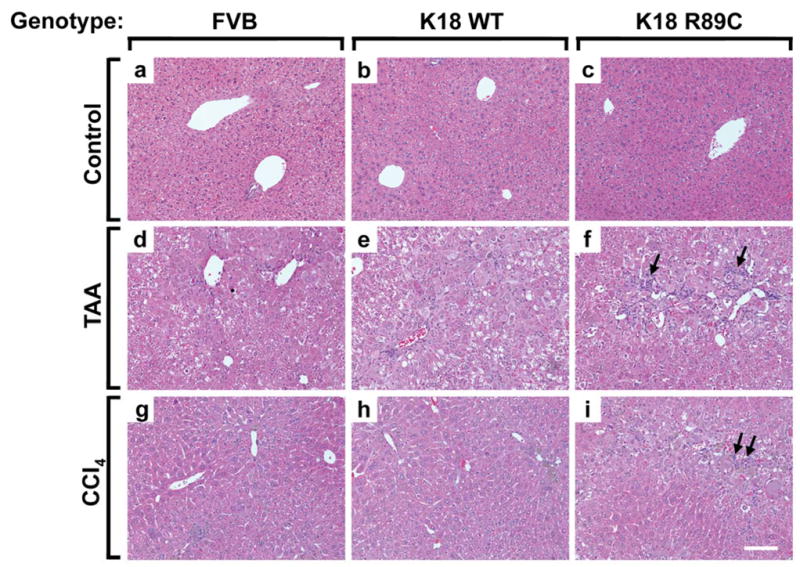

To test whether keratin mutation leads to accelerated liver fibrosis, we treated K18 WT and K18 R89C mice with CCl4, an established liver fibrosis inducer. In pilot experiments, we used a dose of 1 ml CCl4/kg mouse weight as commonly described.26,28 This dose led to marked lethality in FVB/n mice within four weeks prior to the development of significant hepatic fibrosis (not shown). Notably, strain differences in responsiveness to CCl4 have been described.38 Lower doses of CCl4 administered to males caused considerable lethality, whereas minimal-to-no lethality was observed in female animals. Therefore, we used only female mice in subsequent experiments and injected them with 0.2 ml CCl4/kg i.p., which resulted in minimal lethality (Table 1). Despite similar elevations in ALT, histological analysis demonstrated a significant difference in liver injury when comparing K18 R89C with K18 WT and nontransgenic animals, which was evident in the lobular and periportal areas (Fig. 1g–i; Table 1). The CCl4 treatment led to moderate liver fibrosis, as noted after PSR staining (Fig. 2g–i, Table 1), by collagen immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 3Ag–i), and by hydroxyproline measurement (Fig. 3C). However the extent of fibrosis did not differ significantly between nontransgenic, K18 WT and K18 R89C livers after CCl4 treatment (Fig. 3).

Figure 1. K18 R89C mice develop more pronounced liver injury after CCl4 and TAA treatment.

Nontransgenic mice (FVB; a,d,g) and mice overexpressing human K18 (K18 WT; b,e,h) or K18 R89C (c,f,i) were treated with TAA- (d–f) or CCl4 (g–i) for 6 and 8 weeks, respectively. Note that both TAA- and CCl4-treated K18 R89C mice develop more pronounced liver injury as evidenced by an increased inflammatory reaction after H&E staining (arrows in f,i) which is quantified in Table 1. Scale bar=100 μm.

Figure 2. K18 R89C mice develop increased liver fibrosis after TAA but not CCl4 treatment.

The extent of liver fibrosis in control mice (a–c) and mice given TAA for 6 weeks (d–f) or CCl4 for 8 weeks (g–i) was evaluated using PSR staining. Nontransgenic mice (FVB; a,d,g), and mice overexpressing human K18 WT (b,e,h) or K18 R89C (c,f,i) were analyzed. Note that TAA-treated K18 R89C mice exhibit more pronounced fibrosis than K18 WT and nontransgenic mice (arrows in d–f), whereas no difference is noted in the three strains treated with CCl4 (arrows in g–i). Scale bar=200 μm.

Figure 3. K18 R89C livers harbor increased collagen mRNA and protein, and hydroxyproline levels, after TAA but not CCl4 treatment as compared with nontransgenic and K18 WT livers.

(A) Double immunofluorescence staining using antibodies to K8 (green) and collagen (red) highlights the extent of collagen deposition in nontransgenic mice (FVB; a,d,g), mice overexpressing K18 (K18 WT; b,e,h) or K18 R89C (c,f,i) under basal conditions (a–c) or after six weeks of TAA (d–f) or eight weeks of CCl4 administration (g–i). Note the increased collagen staining in livers of TAA-treated (arrows, d–f), but not CCl4-treated (arrows, g–i) K18 R89C versus K18 WT and nontransgenic mice. Scale bar=200 μm. (B) 6 weeks of TAA treatment (left panel) causes a higher hepatic collagen mRNA expression in K18 R89C versus K18 WT and nontransgenic livers as determined by quantitative real time RT-PCR. In contrast, similar collagen mRNA levels are observed in all three strains after eight weeks of CCl4 administration (right panel). The expression in nontransgenic mice was arbitrarily set as 1. Four mice were analyzed/strain/treatment condition. (C) Hydroxyproline is measured as described in “Materials and Methods” using livers from control (untreated), TAA-treated or CCl4-treated nontransgenic (FVB), K18 WT and K18 R89C mice. The number of independent livers used for each condition is shown below the x-axis. All three CCl4-treated strains of mice and the TAA-treated K18 R89C mice have significantly elevated levels of hydroxyproline content (p <0.05, not shown) when compared with their counterparts in the untreated control groups.

TAA treatment induces more prominent liver fibrosis in K18 R89C versus K18 WT mice

We used TAA to further test whether keratin mutation predisposes to liver fibrosis. TAA was well tolerated in female FVB mice, but not in male animals (not shown). Therefore, we used female animals for our subsequent experiments. Unlike CCl4, TAA was tolerated less in the K18 R89C mice and led to ~30% lethality whereas no deaths were noted in K18 WT or nontransgenic mice (Table 1). TAA induced an increase in liver size, which was not seen after CCl4 treatment (Table 1) or prior to TAA administration (not shown). The increased liver size differed between strains, with % liver-to-body weights being K18 R89C>K18 WT>FVB (Table 1). ALT levels were moderately elevated but similar in all three mouse lines, while ALP levels were lower in the K18 R89C mice. In addition, TAA induced a more significant periportal but not lobular liver injury in K18 R89C versus K18 WT mice (Fig. 1d–f, Table 1). There was also a trend towards increased periportal injury in K18 WT versus FVB livers that did not reach statistical significance (Table 1). In contrast to the findings in the CCl4 model, TAA led to significantly more pronounced liver fibrosis in K18 R89C as compared with K18 WT and nontransgenic mice as determined using PSR staining (Fig. 2d–f; Table 1) and anti-collagen immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 3A,d–f). Quantitative real time RT-PCR and hydroxyproline analysis confirmed the increased collagen production and deposition in K18 R89C livers in TAA- but not the CCl4-treated mice (Fig. 3). K18 WT and R89C mice do not develop spontaneous fibrosis (tested up to 18 month of age, not shown).

TAA treatment leads to a stronger induction of genes associated with matrix remodeling in K18 R89C versus K18 WT mice

To assess the impact of K18 R89C mutation on the accelerated TAA-induced liver fibrogenesis, we analyzed the expression level of several fibrosis-associated genes (Table 2). K18 R89C, when compared with K18 WT, exhibited up-regulation of several genes associated with matrix remodeling such as TIMP1, TIMP2, MMP2 and MMP13. No changes were detected in genes responsible for stellate cell activation, such as PDGF-R, TGFβ or SMA. K18 WT mice showed increased expression of MMP13 and a trend towards overexpression of TGFβ and TIMP1 when compared with nontransgenic animals. Therefore, the hepatocyte K18 R89C mutation led to the up-regulation of several fibrosis-associated genes. Changes in both pro/anti-fibrotic genes likely reflects extra-cellular matrix turnover with a net fibrosis outcome.

Table 2.

mRNA expression of fibrosis-relevant genes in TAA-treated mice

| Marker | FVB | K18 WT | K18 R89C | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hK18 | none | 1 | 1.1 | ns |

| mK18 | 1 | 1.0 | 1.1 | ns |

| TNFα | 1 | 2.0 | 2.2 | ns |

| PDGF-R | 1 | 1.1 | 1.7 | ns |

| TGFβ | 1b | 1.5b | 1.8 | ns |

| SMA | 1 | 1.0 | 1.1 | ns |

| TIMP1 | 1c | 2.0c | 3.7 | 0.02 |

| TIMP2 | 1 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 0.05 |

| MMP2 | 1 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 0.04 |

| MMP3 | 1 | 1.9 | 2.0 | ns |

| MMP13 | 1d | 4.2d | 9.3 | 0.02 |

| ICAM1 | 1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | ns |

K18 WT and K18 R89C mice were compared

p=0.05

p=0.06

p=0.008 (when comparing the indicated strains)

TAA but not CCl4 treatment leads to K8/K18 overexpression and to increased keratin phosphorylation

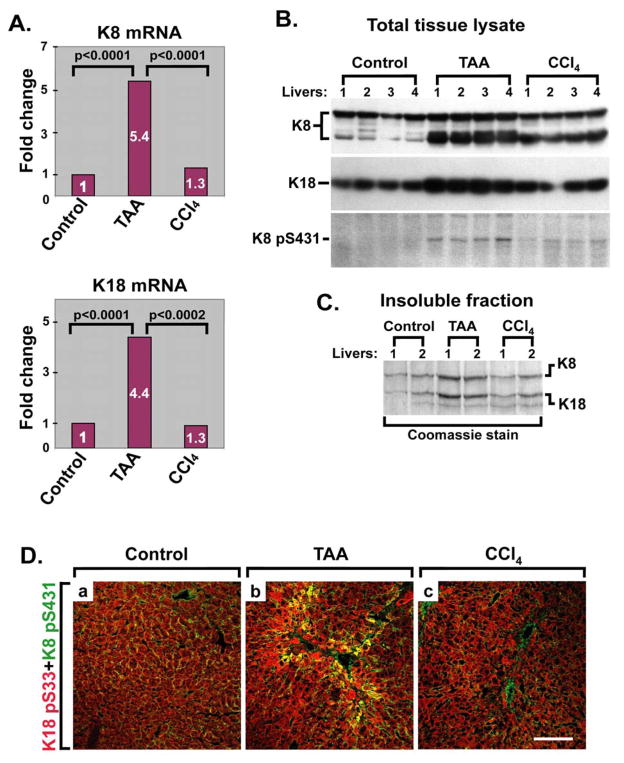

To further characterize the different impact of K18 R89C on liver fibrosis in the two models, we analyzed the effect of TAA and CCl4 on keratin expression. We addressed this aspect given the known induction of keratin expression during some forms of liver injury such as exposure to drugs that induce Mallory-Denk body formation,39 but not in the context of liver injury induced by a high fat diet.40 TAA, but not CCl4 induces a prominent increase in K8 and K18 mRNA in nontransgenic FVB mouse livers (Fig. 4A). The mRNA up-regulation was confirmed at the protein level by immunoblotting of total liver homogenates (Fig. 4B) or by isolation of the insoluble keratin fraction and visualization by Coomassie staining (Fig. 4C), with higher keratin protein in livers derived from TAA- versus CCl4-treated mice. Analysis of keratin protein in K18 WT and K18 R89C livers after TAA exposure afforded similar trends to the mRNA findings (Supplemental Fig. 1, Table 2). TAA also resulted in increased keratin phosphorylation at K8 pS431 and K18 pS33 as confirmed by immunostaining and blotting (Fig. 4B,D). The increased keratin phosphorylation occurs primarily in perifibrotic areas of TAA-treated mice as determined by staining using antibodies to K8 pS431 and collagen (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Figure 4. TAA but not CCl4 treatment increases keratin expression and phosphorylation.

(A) Liver K8 (upper panel) and K18 (lower panel) expression levels in nontransgenic mice increase after TAA but not CCl4 treatment as determined by quantitative real time RT-PCR. Keratin expression in untreated mice (Control) was arbitrarily set as 1, and four mice were analyzed/strain/treatment condition. (B) Immunoblot analysis of nontransgenic mouse total liver lysates before (Control) and after TAA and CCl4 administration. Four individual livers/genotype were analyzed. Note that TAA leads to a significant increase in total K8/K18 protein levels and K8 phospho-S431, whereas CCl4 administration shows less prominent changes. (C) Livers from two nontransgenic mice/treatment group, from control or TAA/CCl4-treated mice, were homogenized to isolate the high-salt insoluble keratin fraction followed by analysis by SDS-PAGE then Coomassie staining. Equal fractions were loaded in each lane and normalization was done by using equal weights of liver pieces. (D) Immunofluorescence double-staining was carried out on livers similar to those used in panels A–C, using antibodies to K8 phospho-S431 (green) and K18 phospho-S33 (red). Yellow color indicates co-localization of the two epitopes. Scale bar=100 μm.

TAA and CCl4 are distinct fibrosis models leading to unique molecular alterations in cytoskeletal and chaperone proteins

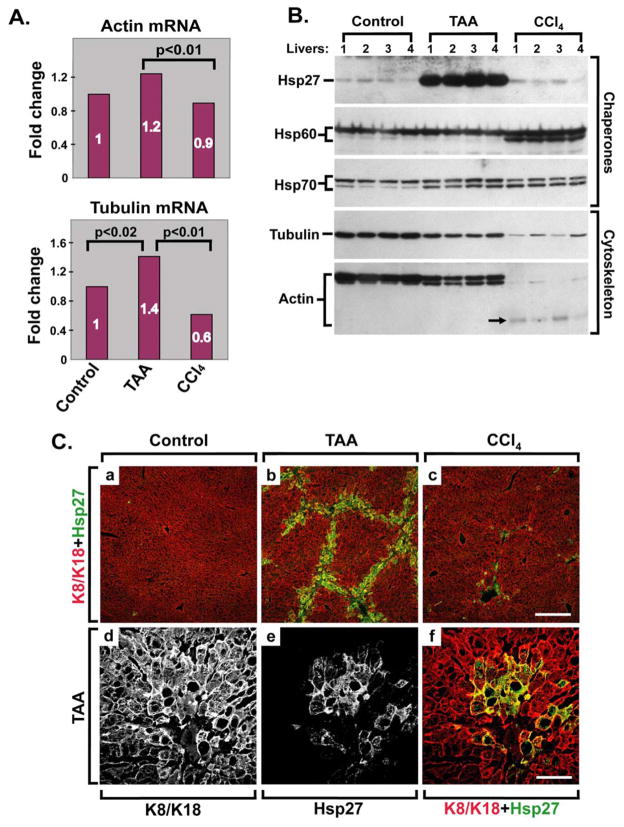

To further characterize the differences between the TAA and CCl4 fibrosis models, we examined their histological features in more detail. TAA resulted in more prominent hepatocyte vacuolization, acidophil bodies and oval cell accumulation, and the appearance of reactive nuclei with prominent nucleoli (Supplemental Fig. 3A,C; Supplemental Table 2), whereas CCl4 led to bridging fibrosis being more uniformly seen in all the animals which was also accompanied by capsular inflammation (Supplemental Fig. 3B,D; Supplemental Table 2). In addition, we analyzed the expression of several cytoskeleton- and chaperone-related genes after both drug treatments. We studied the cytoskeletal proteins β-actin and α-tubulin because they are known to associate with keratins indirectly via linker proteins such as plectin.41 We also focused on chaperones given the known association of Hsp70 with K8/K18.42 CCl4 results in diminished β-actin and α-tubulin mRNA and protein levels when compared with TAA (Fig. 5A,B). However, both fibrosis models exhibit lower actin and tubulin protein levels than control livers, and the impact on actin and tubulin is particularly prominent in the CCl4 model. The decrease in actin and tubulin protein is due, at least in part, to protein degradation as evidenced by the presence of lower molecular weight Ab-positive cross-reactive species for several of the tested proteins (K8 in Fig. 4; Hsp60, Hsp70 and actin in Fig. 5B). Phalloidin staining, which labels F-actin, shows retained peri-membranous hepatocyte staining in the CCl4 and TAA models (not shown) which suggests that some of the decreased antibody reactivity (Fig. 5B, actin blot, lanes 9–12) may be related to epitope modification.

Figure 5. TAA and CCl4 are distinct fibrosis models that lead to unique molecular alterations.

(A) β-actin and α-tubulin mRNA levels were compared in livers from four nontransgenic mice/treatment group (control or TAA/CCl4-treated mice) using quantitative real time RT-PCR. The levels observed in untreated mice (Control) were arbitrarily set as 1. (B) Liver pieces from the same mice analyzed in panel A were homogenized and the homogenates were blotted using antibodies to the indicated cytoskeletal and chaperone proteins. Note that TAA induces prominent overexpression of Hsp27, which is not seen in control or CCl4-treated livers. Both models result in decreased actin and tubulin levels, but the change is much more prominent after CCl4 administration. The decrease in actin and tubulin protein levels is related at least in part to actin (arrow) and tubulin (not shown) degradation. (C) (a–c): Liver sections from nontransgenic mice similar to those used in Panels A,B were double-stained using antibodies to K8/K18 (red) and Hsp27 (green). Scale bar=200 μm. (d–f): A higher magnification of a liver from animals given TAA (similar to that shown in image b) is displayed to highlight each individual staining and the merged image. Scale bar=50 μm.

Among the chaperone proteins, TAA treatment induces dramatic up-regulation of Hsp27, which is not seen after CCl4 administration (Fig. 5B). Hsp27 becomes abundantly expressed in perifibrotic areas of TAA-treated livers as noted after double-staining with antibodies to collagen/Hsp27 (Supplemental Fig. 2A,B). Induction of Hsp27 occurs in hepatocytes, based on co-localization with keratin-positive cells (Fig. 5C) but not in cells undergoing keratin hyperphosphorylation (Supplemental Fig. 2A,C). In contrast with Hsp27, Hsp70 levels increase similarly in the TAA and CCl4 models, while Hsp60 increases only in the CCl4 model. Therefore, the TAA and CCl4 models manifest drastically different cytoskeletal and chaperone molecular responses.

DISCUSSION

K18 R89C mutation predisposes to increased TAA/CCl4-induced liver injury and to TAA-mediated fibrosis

Human association studies identified an over-representation of K8/K18 variants in patients with end-stage liver disease as compared to healthy blood-bank donors, with an odds ratio of 3.7 (95% CI:2.0–6.8).18 In addition, patients with chronic hepatitis C have a 2.1-fold increased risk (95% CI:1.33–3.15) to harbor a keratin variant with each progressive stage of fibrosis encompassing stages 1–4.18,24 The findings herein support these observations by providing the first animal-based direct evidence that a keratin mutation does predispose to liver fibrosis. Such predisposition may extent to other epithelial tissues such as lung or kidney but this remains to be tested. Furthermore, predisposition of K18 R89C mice to liver injury after CCl4/TAA treatment represents the first evidence showing the importance of keratin variants in the context of chronic liver injury. This is relevant since previous reports focused on acute/subacute liver injuries18,43 and a recent study did not detect a differential impact of K18 R89C as compared with K18 WT on liver injury after chronic feeding with a compound that induces Mallory-Denk body formation.30,39

Properties of the K18 R89C mutation

K18 R89 is conserved in many IF proteins and its homologous mutation in stratified-epithelial-specific K14 (Arg125) causes epidermolysis bullosa simplex in association with keratinocyte fragility.2,21 However, no K18 R89C mutations have been identified to date in more than 2500 patients and controls (not shown) likely because of its presumed lethality in humans (but not mice).18 Therefore, it remains to be determined whether findings related to K18 R89C will translate to other K8/K18 natural variants known to occur in liver disease patients. In this regard, recent studies suggest that mechanisms of keratin variant predisposition to liver injury are likely to be mutation-specific. For example, introducing the second most common K8/K18 human variant seen in patients with liver disease (K8 Gly61Cys) into mice predisposes to apoptosis (similar to K18 R89C) but does not have any effect on hepatocyte fragility (in contrast to K18 R89C).44 In addition, different K8 and K18 variants have different solubility, phosphorylation states, crosslinking, and filament organization properties under basal conditions and/or in response to oxidative stress.22,23,45 Therefore, further studies are needed to assess the impact of other human liver disease-associated K8/K18 variants on the development of liver fibrosis.

Potential mechanisms for K18 R89C predisposition to TAA-induced liver fibrosis

Several mechanisms that are likely involved in keratin mutation-associated predisposition to acute/subacute liver injury are becoming understood,18 but the cause(s) of keratin mutation-mediated predisposition to liver fibrosis are unknown. Accentuation/perpetuation of liver injury are likely culprits given the cytoprotective role of keratins as demonstrated in several transgenic mouse models that express K8/K18 mutants or lack K8/K18,14,18,43 though indirect effects on neighboring non-hepatocyte cells46,47 are possible. For example, keratin protein and mRNA are induced upon various insults, including TAA treatment, and this stress-inducible overexpression may facilitate the protective role of normal keratins, or the injury-predisposing role of mutant keratins.18,43,48 Also, K8/K18 associate with several important signaling molecules such as JNK, Raf-1 and p38 kinases, 14-3-3 proteins;15 and mutation (e.g. K8 G61C) can alter keratin’s ability to serve as a kinase substrate in vivo.44 In addition, keratins sequester some oxidatively-damaged proteins 49 albeit the effect of keratin mutation on such sequestration is unknown except that K18 R89C mutation primes the liver towards oxidative injury as determined using expression profiling analysis and metabolites of some of the altered gene products.50 In that context, several studies support the importance of oxidative stress in mouse and human hepatofibrosis.51–53

K18 R89C mutation also causes hepatocyte fragility and mild liver inflammation under basal conditions,29 but these consequences alone are not sufficient to induce an appreciable level of liver fibrosis in unperturbed livers of aged mice (not shown). Importantly, K8/K18 are anti-apoptotic proteins and keratin mutation leads to increased susceptibility to Fas-induced apoptosis.20,44,54,55 An increased rate of apoptotic death might lead to liver fibrosis46 as demonstrated in mice with liver-specific disruption of Bcl-xL.56

TAA and CCl4 induce distinct fibrosis models

Our findings demonstrate dramatic differences in the molecular response to TAA versus CCl4 which are summarized in Fig. 6. Earlier studies have indicated that TAA and CCl4 are likely to induce different mechanistic pathways. For example, CCl4 causes significant lipid peroxidation with subsequent membrane damage26 whereas TAA metabolites bind covalently to proteins thereby causing hepatotoxicity.57 Also, administration of TAA versus CCl4 to rats induces different acute gene expression patterns when analyzed within 24 hours of administration.58 TAA is an established liver carcinogen, which is consistent with the observed nuclear changes (Supplemental Table 2), and both chemicals differ in their effect on cell-cycle related proteins.59 Similarly, the increased hepatomegaly in the TAA model may also be related to the prominent nuclear changes associated with this model. With respect to fibrosis, both TAA and CCl4 induce centrilobular necrosis with activation of stellate cells and subsequent centrilobular fibrosis.26 However, TAA is toxic to portal tracts and leads to their enlargement and to cholangiocyte proliferation.60 Therefore, one potential contributory explanation for our findings is that portal fibroblast activation after exposure to TAA but not CCl4 might contribute to the differences in the keratin-related fibrosis development and unique chaperone and cytoskeletal protein differences between the two models. Furthermore, genetic strain and immune-modulation differences, as previously demonstrated for CCl4-induced fibrosis,61 may manifest different responses to TAA-mediated fibrosis but this possibility remains to be tested.

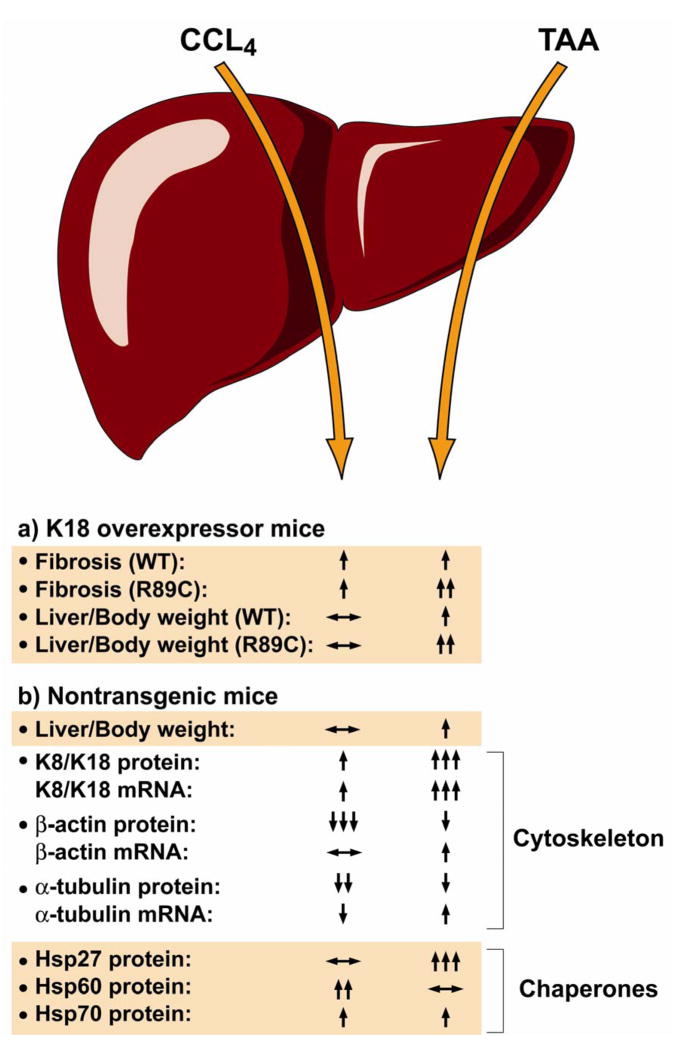

Figure 6. Summary of findings from the CCl4 and TAA fibrosis models in the context of normal and mutant K18.

Both CCl4 and TAA induce fibrosis in nontransgenic and K18 WT-overexpressing mice, but the K18 R89C mutation leads to an accelerated fibrosis in the TAA but not the CCl4 model. Hepatomegaly (liver-to-body weight size) is also more prominent in the K18 R89C mice and in the TAA model in general. In nontransgenic mice, the CCl4 and TAA models evoke very different molecular responses as manifested by markedly different effects on cytoskeletal proteins and chaperones.

Given our overall findings in terms of the K18 mutation-related unmasking of differential susceptibility to TAA versus CCl4 induced fibrosis, we hypothesize that differences between the CCl4/TAA models reflect distinct fibrosis pathways that are keratin-related or keratin-unrelated. Keratin-related fibrosis includes keratin up-regulation/modification, and changes in proteins that directly or indirectly associate with keratins such as the cytoskeletal proteins β-actin and α-tubulin (e.g., via plectin)41 and the chaperones Hsp70 and Hsp27.40,62 The differential biologic response of the K18 R89C mutant to TAA versus CCl4 may relate to earlier observations that K18 R89C mice are markedly more susceptible to Fas but not TNF induced apoptosis.20 Interestingly, hepatocyte apoptosis (i.e., a state analogous to the presence of a relevant keratin mutation) correlates with hepatic fibrosis activity in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.63 Our findings have potential significant implications for human fibrosis in different liver diseases, which are likely to be impacted by the presence of keratin variants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Evelyn Resurrection for assistance with immune staining, Pauline Chu for assistance with histochemical staining, Phillip So for technical assistance and Dr. Larry Fisher (Matrix Biochemistry Unit, NIH/NIDCR) for the generous gift of anti-collagen antibodies. This work was supported by NIH grant DK52951 and the Department of Veterans Affairs (M.B.O.), NIH Center grant DK56339 and in part by an EMBO postdoctoral fellowship (P.S.).

Nonstandard abbreviations used

- Ab

antibody

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- CCl4

carbon tetrachloride

- h

human

- IF

intermediate filament

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- Hsp

heat shock protein

- i.p

intraperitoneally

- K

keratin

- p

phospho

- PSR

Picro-sirius red

- TAA

thioacetamide

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ku N-O, Zhou X, Toivola DM, et al. The cytoskeleton of digestive epithelia in health and disease. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:G1108–1137. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.6.G1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Omary MB, Coulombe PA, McLean WH. Intermediate filament proteins and their associated diseases. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2087–2100. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herrmann H, Hesse M, Reichenzeller M, et al. Functional complexity of intermediate filament cytoskeletons: from structure to assembly to gene ablation. Int Rev Cytol. 2003;223:83–175. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(05)23003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coulombe PA, Wong P. Cytoplasmic intermediate filaments revealed as dynamic and multipurpose scaffolds. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:699–706. doi: 10.1038/ncb0804-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Worman HJ, Courvalin JC. Nuclear envelope, nuclear lamina, and inherited disease. Int Rev Cytol. 2005;246:231–279. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(05)46006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattout A, Dechat T, Adam SA, et al. Nuclear lamins, diseases and aging. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coulombe PA, Omary MB. “Hard” and “soft” principles defining the structure, function and regulation of keratin intermediate filaments. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:110–122. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(01)00301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schweizer J, Bowden PE, Coulombe PA, et al. New consensus nomenclature for mammalian keratins. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:169–174. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200603161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quinlan RA, Cohlberg JA, Schiller DL, et al. Heterotypic tetramer (A2D2) complexes of non-epidermal keratins isolated from cytoskeletons of rat hepatocytes and hepatoma cells. J Mol Biol. 1984;178:365–388. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kulesh DA, Cecena G, Darmon YM, et al. Posttranslational regulation of keratins: degradation of mouse and human keratins 18 and 8. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:1553–1565. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.4.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ku NO, Omary MB. Keratins turn over by ubiquitination in a phosphorylation-modulated fashion. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:547–552. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.3.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou Q, Toivola DM, Feng N, et al. Keratin 20 helps maintain intermediate filament organization in intestinal epithelia. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:2959–2971. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-02-0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helfand BT, Chang L, Goldman RD. Intermediate filaments are dynamic and motile elements of cellular architecture. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:133–141. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magin TM, Vijayaraj P, Leube RE. Structural and regulatory functions of keratins. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:2021–2032. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Omary MB, Ku NO, Tao GZ, et al. “Heads and tails” of intermediate filament phosphorylation: multiple sites and functional insights. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green KJ, Bohringer M, Gocken T, et al. Intermediate filament associated proteins. Adv Protein Chem. 2005;70:143–202. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(05)70006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toivola DM, Ku NO, Resurreccion EZ, et al. Keratin 8 and 18 hyperphosphorylation is a marker of progression of human liver disease. Hepatology. 2004;40:459–466. doi: 10.1002/hep.20277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ku N-O, Strnad P, Zhong B, et al. Keratins let liver live: mutations predispose to liver disease and crosslinking generates Mallory-Denk bodies. Hepatology. 2007;46:1639–1649. doi: 10.1002/hep.21976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ku NO, Michie SA, Soetikno RM, et al. Susceptibility to hepatotoxicity in transgenic mice that express a dominant-negative human keratin 18 mutant. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1034–1046. doi: 10.1172/JCI118864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ku N-O, Soetikno RM, Omary MB. Keratin mutation in transgenic mice predisposes to FAS but not TNF induced apoptosis and massive liver injury. Hepatology. 2003;37:1006–1014. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Porter RM, Lane EB. Phenotypes, genotypes and their contribution to understanding keratin function. Trends Genetics. 2003;19:278–285. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(03)00071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ku NO, Gish R, Wright TL, et al. Keratin 8 mutations in patients with cryptogenic liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1580–1587. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105243442103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ku NO, Lim JK, Krams SM, et al. Keratins as susceptibility genes for end-stage liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:885–893. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strnad P, Lienau TC, Tao GZ, et al. Keratin variants associate with progression of fibrosis during chronic hepatitis C infection. Hepatology. 2006;43:1354–1363. doi: 10.1002/hep.21211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krahenbuhl S, Reichen J. Adaptation of mitochondrial metabolism in liver cirrhosis. Different strategies to maintain a vital function. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;193:90–96. doi: 10.3109/00365529209096012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weber LW, Boll M, Stampfl A. Hepatotoxicity and mechanism of action of haloalkanes: carbon tetrachloride as a toxicological model. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2003;33:105–136. doi: 10.1080/713611034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsukamoto H, Matsuoka M, French SW. Experimental models of hepatic fibrosis: a review. Semin Liver Dis. 1990;10:56–65. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1040457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Constandinou C, Henderson N, Iredale JP. Modeling liver fibrosis in rodents. Methods Mol Med. 2005;117:237–250. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-940-0:237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ku NO, Michie S, Oshima RG, et al. Chronic hepatitis, hepatocyte fragility, and increased soluble phosphoglycokeratins in transgenic mice expressing a keratin 18 conserved arginine mutant. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1303–1314. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.5.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harada M, Strnad P, Resurreccion E, et al. Keratin 18 overexpression but not phosphorylation or filament organization blocks mouse Mallory body formation. Hepatology. 2007;45:88–96. doi: 10.1002/hep.21471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ku NO, Michie SA, Soetikno RM, et al. Mutation of a major keratin phosphorylation site predisposes to hepatotoxic injury in transgenic mice. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:2023–2032. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.7.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ku NO, Toivola DM, Zhou Q, et al. Studying simple epithelial keratins in cells and tissues. Methods Cell Biol. 2004;8:489–517. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(04)78017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernstein EF, Fisher LW, Li K, et al. Differential expression of the versican and decorin genes in photoaged and sun-protected skin. Comparison by immunohistochemical and northern analyses. Lab Invest. 1995;72:662–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scheuer PJ. Classification of chronic viral hepatitis: a need for reassessment. J Hepatol. 1991;13:372–374. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(91)90084-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakamichi I, Toivola DM, Strnad P, et al. Keratin 8 overexpression promotes mouse Mallory body formation. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:931–937. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edwards CA, O’Brien WD., Jr Modified assay for determination of hydroxyproline in a tissue hydrolyzate. Clin Chim Acta. 1980;104:161–167. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(80)90192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xia JL, Dai C, Michalopoulos GK, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor attenuates liver fibrosis induced by bile duct ligation. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:1500–1512. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi Z, Wakil AE, Rockey DC. Strain-specific differences in mouse hepatic wound healing are mediated by divergent T helper cytokine responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10663–10668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zatloukal K, French SW, Stumptner C, et al. From Mallory to Mallory-Denk bodies: What, how and why? Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:2033–2049. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tao GZ, Toivola DM, Zhong B, et al. Keratin-8 null mice have different gallbladder and liver susceptibility to lithogenic diet-induced injury. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4629–4638. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sonnenberg A, Liem RK. Plakins in development and disease. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:2189–2203. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liao J, Lowthert LA, Ghori N, et al. The 70-kDa heat shock proteins associate with glandular intermediate filaments in an ATP-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:915–922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.2.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zatloukal K, Stumptner C, Fuchsbichler A, et al. The keratin cytoskeleton in liver diseases. J Pathol. 2004;204:367–376. doi: 10.1002/path.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ku NO, Omary MB. A disease- and phosphorylation-related nonmechanical function for keratin 8. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:115–125. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200602146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Owens DW, Wilson NJ, Hill AJ, et al. Human keratin 8 mutations that disturb filament assembly observed in inflammatory bowel disease patients. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:1989–1999. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Friedman SL. Mechanisms of disease: Mechanisms of hepatic fibrosis and therapeutic implications. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;1:98–105. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iredale JP. Models of liver fibrosis: exploring the dynamic nature of inflammation and repair in a solid organ. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:539–548. doi: 10.1172/JCI30542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhong B, Zhou Q, Toivola DM, et al. Organ-specific stress induces mouse pancreatic keratin overexpression in association with NF-kappaB activation. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:1709–1719. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tao GZ, Zhou Q, Strnad P, et al. Human Ran cysteine-112 oxidation by pervanadate regulates its binding to keratins. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12162–12167. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412505200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou Q, Ji X, Chen L, et al. Keratin mutation primes mouse liver to oxidative injury. Hepatology. 2005;41:517–525. doi: 10.1002/hep.20578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siegmund SV, Dooley S, Brenner DA. Molecular mechanisms of alcohol-induced hepatic fibrosis. Dig Dis. 2005;23:264–274. doi: 10.1159/000090174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Farrell GC, Larter CZ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: from steatosis to cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2006;43:S99–S112. doi: 10.1002/hep.20973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Natarajan SK, Thomas S, Ramamoorthy P, et al. Oxidative stress in the development of liver cirrhosis: a comparison of two different experimental models. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:947–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Caulin C, Ware CF, Magin TM, et al. Keratin-dependent, epithelial resistance to tumor necrosis factor- induced apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:17–22. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gilbert S, Loranger A, Daigle N, et al. Simple epithelial keratins 8 and 18 provide resistance to Fas-mediated apoptosis. The protection occurs through a receptor-targeting modulation. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:763–773. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200102130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takehara T, Tatsumi T, Suzuki T, et al. Hepatocyte-specific disruption of Bcl-xL leads to continuous hepatocyte apoptosis and liver fibrotic responses. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1189–1197. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dyroff MC, Neal RA. Identification of the major protein adduct formed in rat liver after thioacetamide administration. Cancer Res. 1981;41:3430–3435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bulera SJ, Eddy SM, Ferguson E, et al. RNA expression in the early characterization of hepatotoxicants in Wistar rats by high-density DNA microarrays. Hepatology. 2001;33:1239–1258. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.23560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jeong DH, Jang JJ, Lee SJ, et al. Expression patterns of cell cycle-related proteins in a rat cirrhotic model induced by CCl4 or thioacetamide. J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:24–32. doi: 10.1007/s005350170150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guyot C, Combe C, Clouzeau-Girard H, et al. Specific activation of the different fibrogenic cells in rat cultured liver slices mimicking in vivo situations. Virchows Arch. 2007;450:503–512. doi: 10.1007/s00428-007-0390-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shi Z, Wakil AE, Rockey DC. Strain-specific differences in mouse hepatic wound healing are mediated by divergent T helper cytokine responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:10663–10668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Perng MD, Cairns L, van den IJssel P, et al. Intermediate filament interactions can be altered by HSP27 and alphaB-crystallin. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:2099–2112. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.13.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Feldstein AE, Canbay A, Angulo P, et al. Hepatocyte apoptosis and fas expression are prominent features of human nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:437–443. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00907-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.