Abstract

Models have been developed for the analysis of dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) data that do not require direct measurements of the arterial input function; such methods are referred to as reference region models. These models typically return estimates of the volume transfer constant (Ktrans) and the extravascular extracellular volume fraction (ve). To date such models have assumed a linear relationship between the measured R1 (≡1/T1) and the concentration of contrast agent, a transformation referred to as the fast exchange limit, but this assumption is not valid for all concentrations of an agent. A theory for DCE-MRI reference region models which accounts for water exchange is presented, evaluated in simulations, and applied in tumor-bearing mice. Using reasonable parameter values, simulations show that the assumption of fast exchange can underestimate Ktrans and ve by up to 82% and 46%, respectively. By analyzing a large region of interest and a single voxel the new model can return parameters within approximately ±10% and ±25%, respectively, of their true values. Analysis of experimental data shows that the new approach returns Ktrans and ve values that are up to 90% and 73%, respectively, greater than conventional fast exchange analyses.

Keywords: DCE-MRI, reference region, fast exchange regime, tumor, pharmacokinetic

Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) involves the serial acquisition of images before and after the injection of a paramagnetic contrast agent (CA) (1,2). As the agent enters the tissue region under investigation, it changes the T1 and T2 relaxation times of the tissue water, thereby altering the MR signal intensity. As the agent is transported out of the tissue, T1 and T2 return to their native values. An MR signal intensity time course can be constructed for each image voxel or a selected region of interest. The theory typically used to analyze these time courses returns estimates of the volume transfer constant (Ktrans) and the extravascular extracellular volume fraction (ve), parameters which have been shown to be sensitive to tumor growth and treatment response (3–6). This analysis is usually based on indicator dilution theory and requires knowledge of the time rate of change of the concentration of the contrast agent in the blood, the arterial input function (AIF). Characterizing the AIF is a relatively difficult process and several techniques have been developed to try to capture its time course (7–10). The time course of the AIF changes rapidly, so that all of these methods require rapid acquisition schemes, which results in a reduction in both spatial resolution and image signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Consequently, there has been much recent interest in developing methods for analyzing DCE-MRI data that do not require direct measurement of the AIF.

By calibrating signal intensity changes to that in a well-characterized reference region (e.g., healthy muscle), explicit characterization of the AIF is no longer required. Such methods are referred to as reference region (RR) models and originate from the positron emission tomography literature (11). Several such models have recently been presented which incorporate RR formalism into the DCE-MRI analysis (12–15). By not requiring the AIF to be known, high temporal resolution imaging is no longer required, which allows for images to be acquired with both higher spatial resolution and higher SNR. This in turn provides a more powerful technique to probe tumor heterogeneity—one of the principle applications of DCE-MRI. Recent studies with an RR model have reported both good correlation with direct AIF measurement analysis (16) as well as reasonable repeatability (17) and reproducibility (18).

Independent of these developments, there has also been interest in increasing the rigor with which pharmacokinetic parameters are estimated. One of these developments has been the incorporation of the effects of transcytolemmal water exchange into the usual Kety analysis (19–22). The concentration of the CA is not usually measured in a DCE-MRI study, so a calibration from the measured signal intensity to the longitudinal relaxation rate constant R1 (≡1/T1) and then to the concentration of the CA is required. Almost universally a linear relationship between the concentration of CA and R1 has been assumed (1). This linear relationship (essentially) assumes that water exchange between the extravascular–extracellular space and the extravascular–intracellular space is fast compared to the absolute difference in relaxation rates of those components and has been termed the fast exchange limit (FXL) (18,19). Recently it has been shown that such an FXL assumption may be erroneous in the majority of DCE-MRI studies (23–25). By explicitly incorporating finite exchange rates into the Bloch equations, a more accurate model can be obtained. We note that there have also been efforts to account for transendothelial water exchange (that is, water exchange from the intravascular extracellular space to the extravascular extracellular space) as well as an effort to account for both effects simultaneously and the interested reader is referred to such references (26–29). Here we describe how such exchange can be combined with an RR model to exploit the strengths of both approaches.

The analysis of DCE-MRI data using this approach involves several free parameters, including Ktrans for both the RR and the tissue of interest (TOI), ve, and τi (the intracellular lifetime of a water molecule). A model with multiple free parameters can potentially be sensitive to initial guess values and experimental noise. Since the precision and accuracy of the analysis influences the degree to which it is sensitive to longitudinal changes in (for example) tumor physiology, we have investigated the model’s sensitivity to noise and initial guesses using the approach of Buckley et al. (30). Thus, the overall goals of this contribution are: 1) to build an RR model which incorporates the effects of transcytolemmal water exchange, thereby providing a more rigorous model of DCE-MRI analysis at an increased level of spatial resolution and signal-to-noise; 2) to test the model in simulations and assess the accuracy and precision of the model when experimental noise levels are present; and 3) to apply it experimentally in studies of mice with implanted 4T1 mammary carcinomas.

THEORY

(Although it makes the equations longer and more cumbersome, we employ the standardized notation and symbolic conventions described by Tofts et al. (1).) The RR method establishes a relationship between the concentration of CA in the tissue of interest (CTOI) and the RR (CRR), yielding a model that is independent of the concentration in the blood plasma, Cp. Briefly, two copies of the Kety rate law are considered (one for the TOI and one of the RR) and by assuming a common AIF between the two regions, one can substitute one copy into the other, thereby eliminating the explicit dependence on the AIF. Details are presented elsewhere (15) and the main result of the theory as Eq. [1]:

| [1] |

where Ktrans,RR and Ktrans,TOI are Ktrans for the RR and TOI, respectively; ve,RR and ve,TOI are ve for the RR and TOI, respectively; and R = Ktrans,TOI/Ktrans,RR. A relation that calibrates CTOI to the longitudinal relaxation rate, R1,TOI, is required and this is typically taken as a form of Eq. [2]:

| [2] |

where r1 is the longitudinal relaxivity of the CA, and R10 is the native longitudinal relaxation rate of the tissue before CA administration. Eq. [2] is a fast exchange limit (FXL) model; thus, by inserting two copies (one each for the RR and the TOI) of Eq. [2] into Eq. [1] an FXL-RR model is obtained and is given by Eq. [3]:

| [3] |

where R10,TOI and R10,RR are the TOI and RR R1’s before contrast administration, respectively. As stated above, the linear relationship between CTOI and R1 may at times be erroneous and equations accounting for the effects of slower water exchange have been derived to account for transcytolemmal water exchange from the extravascular intracellular space to the extravascular extracellular space. The details of the relevant theory have been presented elsewhere (20,21,23), and the end result is Eq. [4], which incorporates a nonlinear relationship between CA concentration and R1:

| [4] |

where R1i is the intracellular R1, τi is the average intracellular water lifetime of a water molecule, and fw is the fraction of water that is accessible to a mobile CA. This theory has previously been termed the fast exchange regime (FXR) to indicate that while the exchange rate is still fast compared to the absolute difference in relaxation rates of those components, there is a deviation from linearity in the calibration between R1(t) and CTOI(t) (19). By substituting Eq. [1] into Eq. [4], a fast exchange regime reference region model (FXR-RR) is obtained:

| [5] |

To perform a fit to data with the FXR-RR model, a CRR time course is required and this should also include the effects of transcytolemmal water exchange. For this a gamma variate form of CRR is assumed and incorporated into an RR version of Eq. [4] (i.e., with CTOI replaced by CRR) with τi,RR = 1.0 sec, fw,RR = 0.8, and ve,RR = 0.08 (reasonable values for muscle (15,19,31)). Eq. [4] is then fit to an R1 time course obtained from an RR (muscle) and the CRR time course that yields a best fit of the data is used in all subsequent fits of the TOI data to Eq. [5]. Throughout this article we have also assumed R1i = R10. Equation [3] is an FXL-RR model, whereas Eq. [5] is the FXR-RR model and it is these two models that we compare below.

We conclude this section by noting that a plasma component has not been incorporated into the formalism and is thus a limitation of the approach. While a preliminary attempt to incorporate a plasma component into a reference region model has been performed (32), incorporating a plasma term into a reference region model that also accounts for water exchange is quite complex. The reason is that three compartments must be considered: the intravascular space, the extravascular extracellular space, and the extravascular intracellular space. Indeed, Li et al. (22) have developed such a model which contains (at least) five free parameters. Extending this model into a reference region approach would increase the number of free parameters and make it numerically unstable at reasonable signal-to-noise levels. Furthermore, Li et al. showed that, provided Ktrans > 0.1 min−1, eliminating the plasma component is a reasonable assumption. Thus, the model presented here is an effective balance between optimizing signal-to-noise, experimental reality, and rigor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Simulations

To evaluate the method, we simulated AIF, RR, and TOI CA curves. Figure 1 displays the order of operation in conducting the simulations. First, an AIF time course (i.e., the Cp time course) was generated using Eq. [6]:

| [6] |

where A = 9.4 mM · min−1, B = 1.0 min−1, C = 0.15 mM, D = 0.5 min−1, E = 0.013 min−1. This AIF is of the form employed in Simpson et al. (7) and models the initial passage (first term on right-hand side) and the equilibrium and dispersion of the bolus (second term on right-hand side). The resulting AIF was discretized with 51.2-sec temporal resolution (to match the resolution of the experimental data described below). This Cp curve was then converted to CRR and CTOI curves via Eq. [7]:

| [7] |

with Ktrans = 0.045 min−1 and ve = 0.08 assigned for the CRR curve; while Ktrans = 0.096 min−1 and ve = 0.31 were assigned for the CTOI curve. The RR values are reasonable for muscle tissue (15,19,31), and the TOI values are reasonable for enhancement kinetics seen in a variety of tumor types (e.g., 33–35) and represent the average of those values obtained in the mouse studies described below. CRR and CTOI curves are then converted to R1 curves via the fast exchange regime model (Eq. [4]) with τi,RR = 1.0 sec and τi,TOI = 0.60 sec; the τi,TOI value was also the average of τi,TOI obtained in the mouse studies. The CA relaxivity was set at 3.6 mM−1 · s−1 (appropriate for Gd-DTPA (gadolinium diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid) at 7.0 T), and R10 values of 0.85 s−1 and 0.55 s−1 were used for the RR and TOI, respectively. To assess the performance of the models over a range of values, simulations were also performed with TOI parameter values assigned at approximately ±50% of the values obtained in the experiments; that is, a second set of simulations was run with Ktrans,TOI = 0.05 min−1, ve,TOI = 0.15, and τi,TOI = 0.3 sec while a third set was run with Ktrans,TOI = 0.15 min−1, ve,TOI = 0.45, and Ti,TOI = 0.9 sec. The RR and TOI curves were then analyzed by both Eq. [3] and Eq. [5] by a curve fitting routine written in IDL (Research Systems, Boulder, CO). For the FXL-RR analysis (Eq. [3]), the ve,RR value was fixed at its assigned value (0.08), while the Ktrans,RR, Ktrans,TOI, and ve,TOI values were allowed to vary. For the FXR-RR analysis (Eq. [5]), the Ti,RR value was also fixed at 1.0 sec and Ktrans,RR, Ktrans,TOI, ve,TOI, τi,TOI values were allowed to vary. As there are three free parameters in the FXL-RR model and four free parameters in the FXR-RR model, their different sensitivities to initial guesses and noise should be investigated. In applying these models to real experimental data we first fit a large TOI (using a large TOI provides a high SNR) with the full model to obtain a value for Ktrans,RR, which is then fixed. All subsequent fits are performed on a voxel-by-voxel basis and float only Ktrans,TOI and ve,TOI for the FXL-RR model and Ktrans,TOI, and ve,TOI, and τi,TOI for the FXR-RR model.

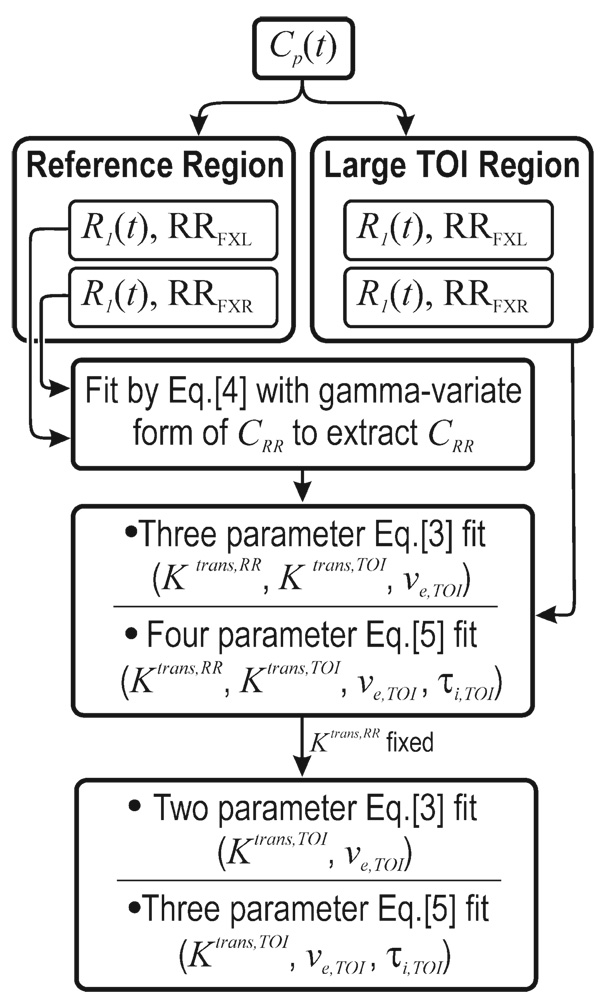

FIG. 1.

The flow chart indicates how the simulations were performed. First an arterial input function was assumed and used to create R1 time courses using both the FXL and FXR formalism. The R1 time course from a large region of interest within (simulated) muscle tissue is then used to extract a CRR time course. A three-parameter FXL-RR and a four-parameter FXR-RR fit are then performed to determine a value for Ktrans,RR, which is then assigned so that subsequent two-parameter (Ktrans and ve) FXL-RR fit and three-parameter (Ktrans, ve, and τi) FXR-RR fits can be performed on a voxel-by-voxel basis.

To test the models’ sensitivity to initial guesses, we employed the approach outlined by Buckley et al. (30). First, Gaussian noise with different standard deviations δ was added to simulated RR and TOI curves to generate 1000 curves using the parameter values listed above. For the simulated RR curves the average percent difference between the RR data and a gamma variate fit was computed for each animal and then averaged; this average value provided the value for δ. By calculating the noise levels in the experimental animal data and using this value to assign the noise levels in the simulations, we can be certain that the noise levels included in the simulations are realistic. Similarly, for the TOI simulated curves the average percent difference between the TOI data curves and the Eq. [3] or Eq. [5] best fit were computed across all animals and averaged to provide one δ for the FXL simulations and one δ for the FXR simulations. The simulated RR and TOI curves were then fit by the four-parameter FXR-RR model with initial guesses that varied about the correct values by 5% and 50%. An identical approach was followed for the three-parameter fit of the individual voxels. The histogram distributions of the parameters were computed for the 1000 runs.

Experimental

Eight female mice were injected subcutaneously in the hindlimb with 106 4T1 mammary carcinoma cells and imaged using a Varian 7.0T scanner equipped with a 38 mm quadrature birdcage coil 16 days postinjection. A series of gradient echo (GRE) images were acquired with different flip angles (12°, 24°, 36°, 48°, 60°) to obtain a T1 map. The DCE-MRI protocol employed a T1-weighted, GRE sequence to obtain 35 serial images for each of eight axial planes in 40 min of imaging. The parameters were: TR/TE/α = 100ms/3.1ms/30°, field of view (FOV) = (30 mm)2, slice thickness = 1.0 mm, matrix = 1282, NEX = 4. (It is important to note that reference region models do not require high temporal resolution data and this allows for acquiring a larger matrix and boosting the SNR via multiple acquisitions.) A bolus of 0.2 mmol/kg Magnevist was delivered within 30 sec via a jugular catheter.

For each mouse, 40 voxels within the perivertebral muscle were selected as the RR and 75 voxels within the tumor were selected as the TOI. The large TOI time course was fit with the three-parameter (Ktrans,TOI, Ktrans,RR, and ve,TOI) FXL-RR model to obtain a value for Ktrans,RR which was then fixed so that a subsequent two-parameter (Ktrans,TOI and ve,TOI) FXL-RR analysis could be performed on all individual voxels within the tumor. Similarly, the TOI time courses were also fit with the four-parameter (Ktrans,TOI, Ktrans,RR, ve,TOI, and τi,TOI) FXR-RR model to obtain a value for Ktrans,RR which was then fixed so that a subsequent three-parameter (Ktrans,TOI, ve,TOI, and τi,TOI) FXR-RR analysis could be performed on individual voxels. By using the whole TOI for the higher-parameter fits, a high SNR is obtained, which leads to improved accuracy and precision, as is commonly done with PET measurements (e.g., 36–39).

Five voxels were randomly selected from each tumor and the results from the two-parameter FXL-RR and three-parameter FXR-RR fits were tabulated. The extracted parameters were averaged across all eight animals to provide the input values for the model testing via simulations. Regression analysis was performed on the differences between the two models as a function of τi.

RESULTS

Simulations

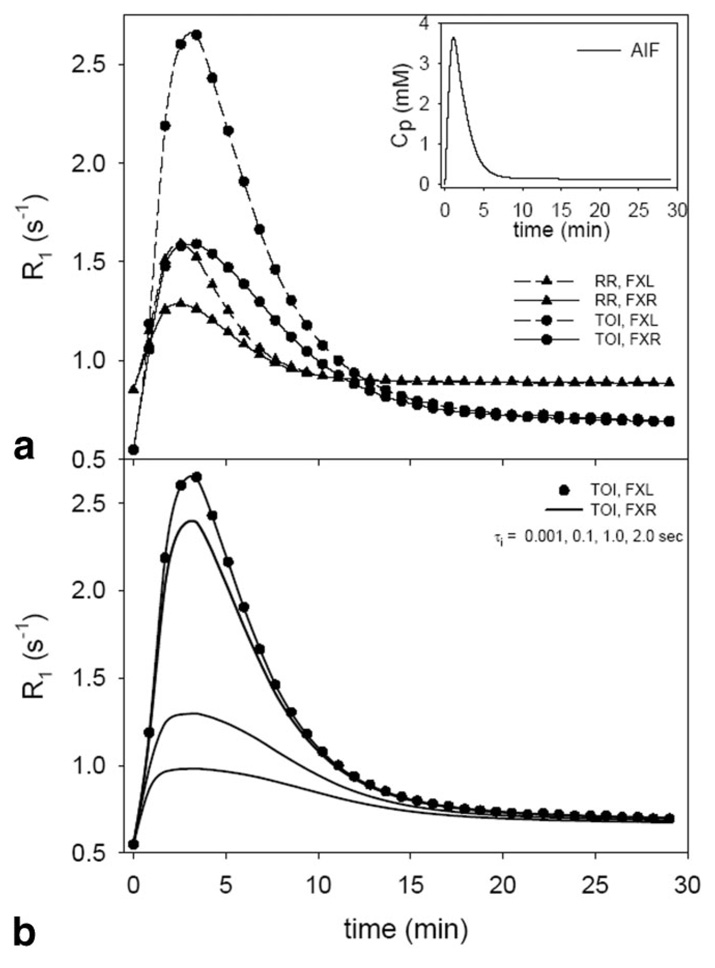

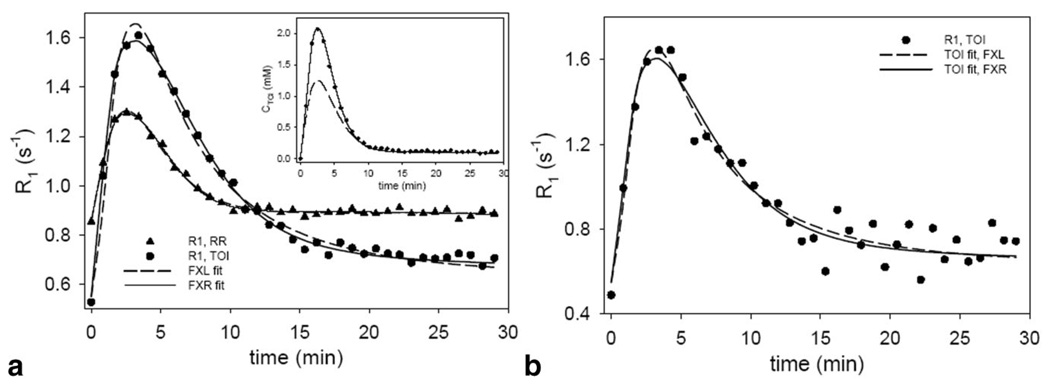

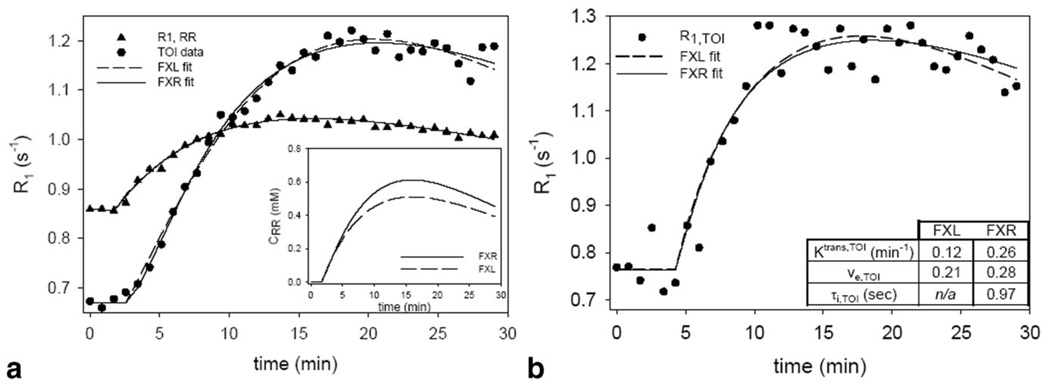

Figure 2 depicts the R1 vs. time curves for the RR and TOI resulting from using the parameter values listed in Table 1 and the AIF depicted in the inset in Fig. 2a. The FXL curves (dashed lines) for both the RR and the TOI rise significantly higher than the corresponding FXR lines. The dependence on the FXR specific parameter τi of the differences between the FXL and FXR curves is displayed in Fig. 2b in which the FXR TOI curves (solid lines) converge to the FXL data (filled circles) as τi decreases. This behavior has previously been reported in a nonreference region formulation of the FXR model (21). The results of fitting such simulated data with the models are illustrated in Fig. 3. The filled circles and triangles represent the TOI and RR R1 curves, respectively, obtained from Fig. 2 with 2% noise added (2% is the average noise that was found in the large TOI selected from each of the eight mice). The dashed and solid lines represent the best three-parameter FXL-RR and four-parameter FXR-RR fits, respectively, and the parameter values returned from these fits are listed in Table 1. The FXL underestimates the true Ktrans,RR and ve,TOI values by 31.6% and the Ktrans,TOI value by 63.5%, whereas the FXR returns values within 8% of their true value. Note that the FXL fit (dashed line) overshoots the peak of the data, then periodically undershoots and overshoots the data. This pattern has also been seen in a nonreference region FXR approach (21). The value for Ktrans,RR was fixed so that a two-parameter FXL-RR and three-parameter FXR-RR fit could be performed and the results are depicted in Fig. 3b and in Table 1. Again, the FXL model underestimates the true values by 63.5% for Ktrans,TOI and 31.6% for ve,TOI, while the FXR returns values within 8.33% of their true values. The table also presents the results seen for the other two TOI parameter combinations considered in the simulations. Note that as the τi,TOI value increases, the discrepancy seen between the FXL and FXR parameters increases.

FIG. 2.

a: The AIF (inset) used to drive the simulations and the results of R1 time courses for the reference region (RR) and tissue of interest (TOI). One set of parameter values was used to make both RR curves and another set were used to make both TOI curves. The differences in R1 time courses as predicted by the FXL and FXR models are evident. b: Highlights that the FXR curve shape converges to the FXL curve shape as the value of τi is reduced.

Table 1.

Parameter Values Extracted from the Fits Presented in Fig. 3

|

Four-parameter fits |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| True | FXL | % error | FXR | % error | |

| Ktrans,RR | 0.045 | 0.037 +/− 0.001 | −18.33 | 0.0445 +/− 0.006 | −0.47 |

| Ktrans,TOI | 0.05 | 0.033 +/− 0.001 | −33.86 | 0.0489 +/− 0.005 | −2.03 |

| ve,TOI | 0.15 | 0.131 +/− 0.002 | −12.80 | 0.149 +/− 0.001 | −0.41 |

| τi,TOI | 0.30 | n/a | n/a | 0.281 +/− 0.09 | −0.4 |

| Ktrans,RR | 0.045 | 0.031 +/− 0.001 | −31.56 | 0.0452 +/− 0.004 | 0.44 |

| Ktrans,TOI | 0.096 | 0.035 +/− 0.001 | −63.54 | 0.0884 +/− 0.009 | −7.92 |

| ve,TOI | 0.31 | 0.212 +/− 0.002 | −31.61 | 0.298 +/− 0.009 | −3.87 |

| τi,TOI | 0.60 | n/a | n/a | 0.560 +/− 0.03 | −6.67 |

| Ktrans,RR | 0.045 | 0.026 +/− 0.001 | −42.00 | 0.0454 +/− 0.005 | 0.89 |

| Ktrans,TOI | 0.15 | 0.028 +/− 0.001 | −81.69 | 0.147 +/− 0.01 | −1.84 |

| ve,TOI | 0.45 | 0.242 +/− 0.001 | −46.02 | 0.445 +/− 0.03 | −1.16 |

| τi,TOI | 0.90 | n/a | n/a | 0.894 +/− 0.02 | −0.68 |

|

Three-parameter fits |

|||||

| True | FXL | % error | FXR | % error | |

| Ktrans,TOI | 0.05 | 0.033 +/− 0.001 | −33.40 | 0.0503 +/− 0.009 | 0.56 |

| ve,TOI | 0.15 | 0.130 +/− 0.004 | −13.33 | 0.149 +/− 0.01 | −0.06 |

| τi,TOI | 0.30 | n/a | n/a | 0.280 +/− 0.1 | −6.67 |

| Ktrans,TOI | 0.096 | 0.035 +/− 0.002 | −63.54 | 0.0895 +/− 0.02 | −6.77 |

| ve,TOI | 0.31 | 0.212 +/− 0.007 | −31.61 | 0.300 +/− 0.03 | −3.23 |

| τi,TOI | 0.60 | n/a | n/a | 0.550 +/− 0.12 | −8.33 |

| Ktrans,TOI | 0.15 | 0.027 +/− 0.001 | −81.68 | 0.149 +/− 0.02 | −1.87 |

| ve,TOI | 0.45 | 0.244 +/− 0.006 | −45.84 | 0.447 +/− 0.02 | −1.16 |

| τi,TOI | 0.90 | n/a | n/a | 0.894 +/− 0.05 | −0.68 |

The FXL consistently returns values below the FXR values and this pattern is seen in the real data fits as well. Note that as the τi,TOI value increases the discrepancy between the FXL and FXR parameters increases.

FIG. 3.

The results of fitting simulated data to the FXL-RR and FXR-RR models. a: The three-parameter FXL-RR fits and the four-parameter FXR-RR fits to high SNR data simulating a large region of interest. It is evident that the FXL models display a systematic deviation from the data by first overshooting the peak of the data and then oscillating below and above the data. b: The two-parameter FXL-RR and the three-parameter FXR-RR fits. Again, a systematic deviation from the data is evident. The parameter estimates returned by each model are presented in the table.

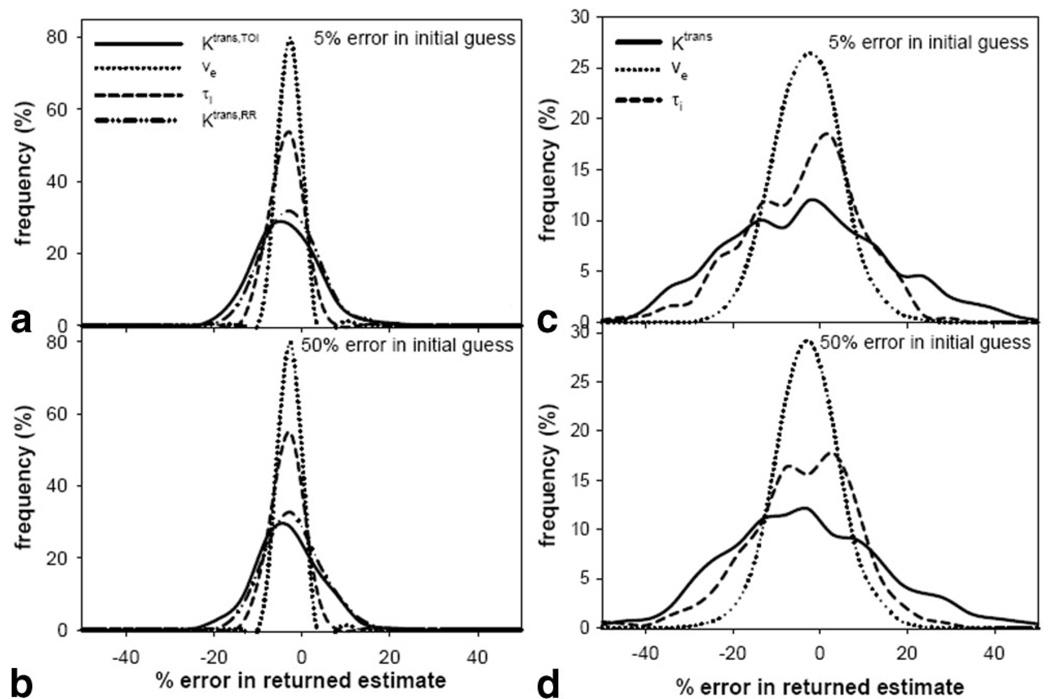

Figure 4a,b depict the errors returned in the four-parameter fit of the TOI data when the initial guesses are within 5% and 50%, respectively, of their true values. The SNR is high in the TOI data, so there is very little difference between the two plots. Thus, the true parameters can be returned within approximately ±15% of their true values with the smallest error seen in ve (ca. ±5%) and the largest error seen in Ktrans,TOI (ca. ±15%). This indicates that the four-parameter FXR-RR fit is stable in the presence of experimental noise levels and is not susceptible to lack of knowledge concerning true parameter values when a large (high SNR) TOI is used. Figure 4c,d present the errors returned in the 3-parameter fits of single voxels when the initial guesses are within 5% and 50% of their true values. The 50% plots indicate that the parameters can be determined only within approximately ±25% of their true values for single voxel (lower SNR) fits. It is important note that these results are for noise levels found in individual voxels and they compare favorably with studies from the literature (40).

FIG. 4.

a,b: The error in the returned estimate when the initial guesses are within 5% and 50%, respectively, of the correct value when the four-parameter FXR-RR model is used. As long as the initial guess is within 50% of the value, the model seems to be stable to noise levels seen in a large region of interest that would be used in the three-parameter fit. c,d: The error in the returned estimate when the initial guesses are within 5% and 50%, respectively, of the correct value when the three-parameter FXR-RR model is used. The three-parameter fit is used for single voxel analysis and the SNR is significantly reduced when compared to a large region of interest and this translates into less certainty about the returned value.

Experimental

Figure 5a presents the results of fitting (representative) real data obtained from a representative mouse with the three-parameter FXL-RR (dashed line) and the four-parameter FXR-RR (solid line) models. The same relationship between the FXL and FXR fits exists in this real data as it did in the simulation. The Ktrans,RR values returned by the FXR and FXL models were 0.056 min−1 and 0.045 min−1, respectively. These values are then fixed for the subsequent two-parameter FXL-RR and three-parameter FXR-RR analyses and the results of those are displayed in Fig. 5b with a table indicating the returned parameter values. Here, the FXL theory returns parameter values that are 88% (Ktrans,TOI) and 25% below those returned by the FXR theory.

FIG. 5.

The results of fitting experimental data to the FXL-RR and FXR-RR models. a: The three-parameter FXL-RR fits and the four-parameter FXR-RR fits to high SNR data from a large region of interest. The systematic FXL error seen in the Fig. 3 simulations is also displayed here. b: The two-parameter FXL-RR and the three-parameter FXR-RR fits and the characteristic FXL mismatch is again evident. The parameter values returned by these fits are presented in the inset in b.

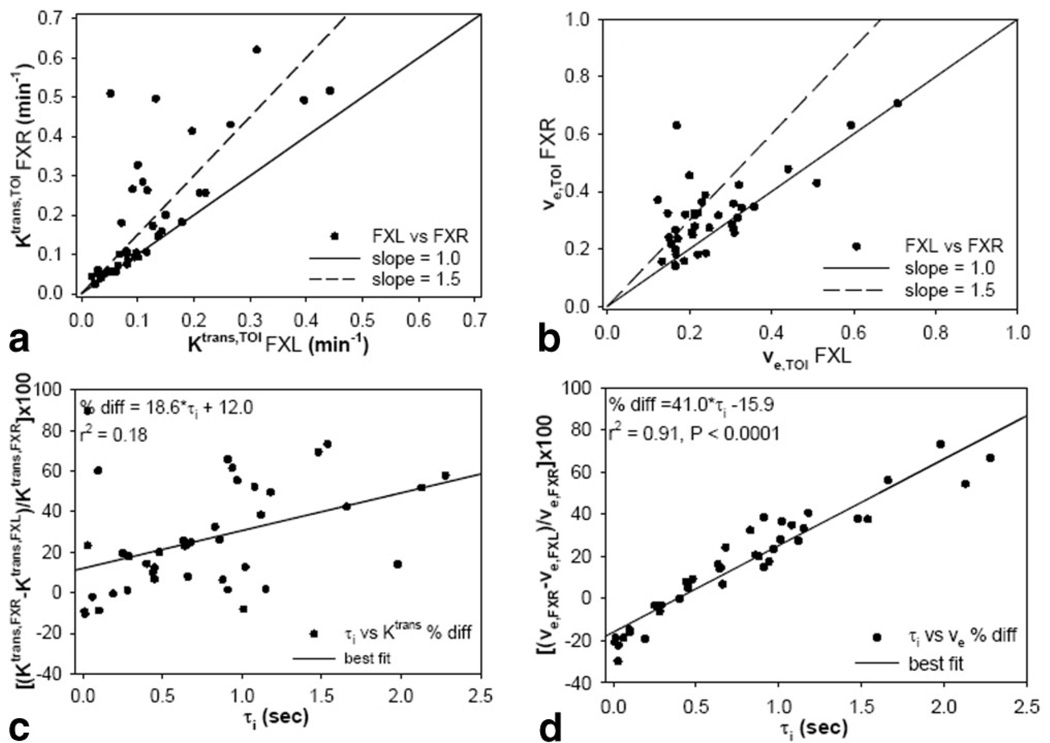

The results of all 40 single voxels fits (five per mouse) are displayed in Fig. 6. In Fig. 6a,b the FXL values are plotted against the FXR values along with a line of unit slope and a line with a slope of 1.5. It is evident that most voxels lie above the unit slope and many above the line of slope 1.5, indicating an FXL underestimation of greater than 50%. A Student’s t-test shows that there is a significant difference between the two parameter sets (P < 0.02 and P < 0.04 for the data depicted in Fig. 6a,b, respectively). Figure 6c,d display the parameter differences returned by each theory as a function of τi; while there is a trend toward increased differences between the two models as τi,TOI increases, only the ve,TOI differences correlate significantly with τi,TOI (r2 = 0.91, P < 0.0001).

FIG. 6.

a,b: Scatterplots of Ktrans,TOI and ve,TOI, respectively, as returned by the FXL-RR and FXR-RR models for all 40 voxels randomly selected from each mouse tumor (five voxels per mouse). It is evident that the FXL model consistently reports parameter values below that returned by the FXR model. c,d: Scatterplot of the percent difference between Ktrans and ve, respectively, as a function of τi value. As τi increases there is a trend for the two models to have a great disparity; this trend is significant in the ve plot (d) but not in the Ktrans plot (c).

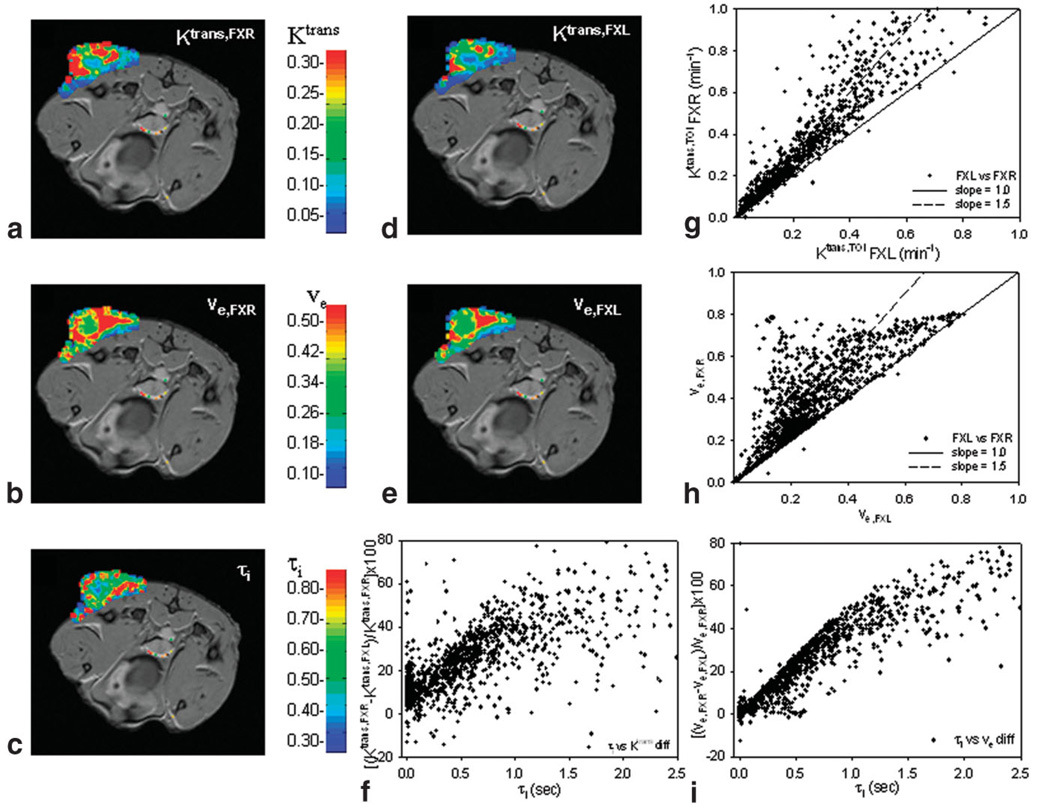

Parametric pharmacokinetic maps of the central slice of the tumor in mouse 2 obtained by each approach are displayed in Fig, 7; Fig. 7a–c are the FXR-RR maps while Fig. 7d,e are the FXL-RR maps. The FXR-RR Ktrans,TOI map indicates increased values throughout the tumor and particularly along the periphery of the lesion that is mimicked, although not to the same degree, as in the FXL-RR map. Both ve,TOI maps yield similar patterns, although the FXL again reports values smaller than the FXR. It is evident that FXL maps yield consistently lower values of the parameters and this is quantified in the scatterplots of Fig. 7g (Ktrans,TOI) and 7h (ve,TOI), which represent the results over all 2000 voxels contained within this particular tumor. Fig. 7f,i display the differences in returned parameters as a function of τi,TOI. Although the patterns are the same as in Fig. 6c,d (i.e., an increased discrepancy between the models as τi,TOI increases), there is no significant linear relationship. Observe that as τi,TOI increases beyond ≈1.0 sec, the linear trend seems to taper.

FIG. 7.

The results of parametric maps by both models of a representative mouse. The Ktrans (a) and ve FXR (b) maps show increased number of red voxels when compared to the corresponding FXL maps (d,e) and this trend is made quantitative in the scatter plots (g,h). f,i: The percent difference between the two models as presented in Fig. 6c,d; the same trend is evident as in Fig. 6 but the linearity of the relationship tends to diminish once τi moves above 1.0 sec in this animal. The scatterplots indicate all (approximately) 2000 voxels across all slices of this tumor. Also, the color maps are superimposed on the tenth postcontrast image and represent the SNR that is used to construct these parametric maps.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Previous work has shown the utility of incorporating the effects of transcytolemmal water exchange into the usual Kety theory for the analysis of DCE-MRI data (19–25). To this point such an analysis required characterization of the time course of contrast agent within the blood plasma. Reference region models eliminate this difficulty and therefore allow imaging time to be spent on boosting spatial resolution (of great import for characterizing, for example, heterogeneous tumors) and SNR. We have presented a theory for the analysis of DCE-MRI data that combines a reference region approach with the effects of transcytolemmal water exchange. The benefits of this approach include the high spatial resolution and high signal-to-noise that is inherent in an RR approach and the level of rigor associated with incorporating the effects of water exchange. The differences between Ktrans,TOI for the FXR-RR and FXL-RR models, as well as the correlation between τi,TOI and Ktrans,TOI and ve,TOI parallel those described previously by nonreference region FXR analyses of DCE-MRI data; that is, as τi,TOI increases the differences between the parameters common to the FXL and FXR formalism (Ktrans,TOI and ve,TOI) become greater. This pattern is illustrated clearly in Fig. 6 and Fig. 7, in which the percent difference between the ve,TOI as estimated by both models, as well as the percent difference between Ktrans,TOI, are plotted versus τi,TOI. As τi,TOI increases, the system is driven out of the FXL and into the FXR with a corresponding increase in percent differences between the two models.

The accuracy and precision of a FXR-RR model has also been assessed. It was found that four-parameter fits of large tumor regions of interest are stable in the presence of typical experimental noise conditions and that subsequent three-parameter individual voxel fits return results that agree with similar studies from the literature. Thus, the FXR-RR model is relatively stable and combines the rigor of an exchange model with the ease of data acquisition of a reference region model. Ideally, the shape of the 50% error plot (Fig. 4b) should have the same shape as that in Fig. 4a; that is, the outcome should be independent of initial guess. These results could be improved, as suggested by Buckley et al. (30), by use of a simplex minimization procedure.

The most obvious drawback of the proposed method includes the assumption of ve,RR and τi,RR values for the reference region. Some confidence can be placed in the assignment of ve,RR = 0.08 in healthy skeletal muscle, as several studies have reported this value (5,31 and references cited therein); nonetheless, errors in the ve,RR assignment can result in errors in the extracted parameters and this has been investigated in the FXL-RR model (15). The value of τi,RR for healthy muscle has also been reported (19,20). A further drawback of the proposed model is the series of steps required to complete the analysis. As described in Fig. 1, an R1 time course obtained from a large region of interest within muscle tissue needs to be acquired and converted to a CRR(t) time course, which is then used to drive a four-parameter FXR-RR analysis to determine a value for Ktrans,RR. After that value is determined it is fixed and a subsequent three-parameter FXR-RR analysis can be performed. Thus, the proposed method adds an additional step to the analysis of DCE-MRI data. However, this results in a more rigorous analysis at higher SNR and spatial resolution than other methods.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the National Institutes of Health for financial support through U24 CA126588, 1K25 EB005936 and RO1 NS45888. We thank Mr. Jarrod True and Mrs. Jennifer Begtrup for expert animal care assistance, and Mr. Richard Baheza for expert technical MRI assistance. We thank the reviewers of the original article for a very careful and thorough critique of our efforts.

Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; Grant numbers: U24 CA 126588, 1K25 EB005936-01, and R01 NS45888

REFERENCES

- 1.Tofts PS, Brix G, Buckley DL, Evelhoch JL, Henderson E, Knopp MV, Larsson HBW, Lee T-Y, Mayr NA, Parker GJM, Port RE, Taylor J, Weisskoff RM. Estimating kinetic parameters from dynamic contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI of a diffusible tracer: standardized quantities and symbols. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;10:223–232. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199909)10:3<223::aid-jmri2>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yankeelov TE, Gore JC. Dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in oncology. Curr Med Imaging Rev. 2007;3:91–107. doi: 10.2174/157340507780619179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lankester KJ, Taylor NJ, Stirling JJ, Boxall J, D’Arcy JA, Leach MO, Rustin GJ, Padhani AR. Effects of platinum/taxane based chemotherapy on acute perfusion in human pelvic tumours measured by dynamic MRI. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:979–985. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li KL, Wilmes LJ, Henry RG, Pallavicini MG, Park JW, Hu-Lowe DD, McShane TM, Shalinsky DR, Fu YJ, Brasch RC, Hylton NM. Heterogeneity in the angiogenic response of a BT474 human breast cancer to a novel vascular endothelial growth factor-receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor: assessment by voxel analysis of dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;22:511–519. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang B, Gao ZQ, Yan X. Correlative study of angiogenesis and dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging features of hepatocellular carcinoma. Acta Radiol. 2005;46:353–358. doi: 10.1080/02841850510021247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zahra MA, Hollingsworth KG, Sala E, Lomas DJ, Tan LT. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI as a predictor of tumour response to radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:63–74. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)71012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simpson NE, He Z, Evelhoch JL. Deuterium NMR tissue perfusion measurements using the tracer uptake approach. I. Optimization of methods. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42:42–52. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199907)42:1<42::aid-mrm8>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Osch MJO, Vonken E-JPA, Viergever MA, Grond J, Bakker CJG. Measuring the arterial input function with gradient echo sequences. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:1067–1076. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McIntyre DJO, Ludwig C, Pasan A, Griffiths JR. A method for interleaved acquisition of a vascular input function for dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI in experimental rat tumours. NMR Biomed. 2004;17:132–143. doi: 10.1002/nbm.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parker GJ, Roberts C, Macdonald A, Buonaccorsi GA, Cheung S, Buckley DL, Jackson A, Watson Y, Davies K, Jayson GC. Experimentally-derived functional form for a population-averaged high-temporal-resolution arterial input function for dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:993–1000. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lammertsma AA, Bench CJ, Hume SP, Osman S, Gunn K, Brooks DJ, Frackowiak RSJ. Comparison of methods for analysis of clinical [11C]Raclopride studies. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1995;16:42–52. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199601000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kovar DA, Lewis M, Karczmar GS. A new method for imaging perfusion and contrast extraction fraction: input functions derived from reference tissues. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1998;8:1126–1134. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880080519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riabkov DY, Di Bella EV. Estimation of kinetic parameters without input functions: analysis of three methods for multichannel blind identification. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2002;49:1318–1327. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2002.804588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang C, Karczmar GS, Medved M, Stadler WM. Estimating the arterial input function using two reference tissues in dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI studies: fundamental concepts and simulations. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:1110–1117. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yankeelov TE, Luci JJ, Lepage M, Li R, Debusk L, Lin C, Price RR, Gore JC. Quantitative pharmacokinetic analysis of DCE-MRI data without an arterial input function: a reference region model. Magn Reson Imag. 2005;23:519–529. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yankeelov TE, Cron GO, Addison C, Wallace JC, Wilkins RC, Pappas BA, Santyr GE, Gore JC. Comparison of a reference region model to direct measurement of an AIF in the analysis of DCE-MRI data. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57:353–361. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yankeelov TE, Debusk L, Luci JJ, Lin C, Price RR, Gore JC. Repeatability of a reference region model for the analysis of murine DCE-MRI data at 7T. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;24:1140–1147. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walker-Samuel S, Parker CC, Leach MO, Collins DJ. Reproducibility of reference tissue quantification of dynamic contrast-enhanced data: comparison with a fixed vascular input function. Phys Med Biol. 2007;52:75–89. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/1/006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landis CS, Li X, Telang FW, Molina PE, Palyka I, Vetek G, Springer CS., Jr Equilibrium transcytolemmal water-exchange kinetics in skeletal muscle in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42:467–478. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199909)42:3<467::aid-mrm9>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landis CS, Li X, Telang FW, Coderre JA, Micca PL, Rooney WD, Latour LL, Vétek G, Pályka I, Springer CS. Determination of the MRI contrast agent concentration time course in vivo following bolus injection: effect of equilibrium transcytolemmal water exchange. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44:563–574. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200010)44:4<563::aid-mrm10>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yankeelov TE, Rooney WD, Xin Li, Springer CS. Variation of the relaxographic “shutter-speed” for transcytolemmal water exchange affects CR bolus-tracking curve shape. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:1151–1169. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X, Rooney WD, Springer CS., Jr A unified magnetic resonance imaging pharmacokinetic theory: intravascular and extracellular contrast reagents. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:1351–1359. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou R, Pickup S, Yankeelov TE, Springer CS, Glickson JD. Simultaneous measurement of arterial input function and tumor pharmacokinetic in mice by dynamic contrast enhanced imaging: effects of equilibrium transcytolemmal water exchange. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:248–257. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li X, Huang W, Yankeelov TE, Tudorica A, Rooney WD, Springer CS. Shutter-speed analysis of CR bolus-tracking data facilitates discrimination of benign and malignant breast disease. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53:724–729. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yankeelov TE, Rooney WD, Huang W, Dyke JP, Li X, Tudorica A, Lee J-H, Koutcher JA, Springer CS. Evidence for shutter-speed variation in CR bolus-tracking studies of human pathology. NMR Biomed. 2005;18:173–185. doi: 10.1002/nbm.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donahue KM, Weisskoff RM, Chesler DA, Kwong KK, Bogdanov AA, Mandeville JB, Rosen BR. Improving MR quantification of regional blood volume with intravascular T1 contrast agents: accuracy, precision, and water exchange. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36:858–867. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwarzbauer C, Morrissey SP, Deichmann R, Hillenbrand C, Syha J, Adolf H, Noth U, Haase A. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging of capillary water permeability and regional blood volume with an intravascular MR contrast agent. Magn Reson Med. 1997;37:769–777. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910370521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parkes LM, Tofts PS. Improved accuracy of human cerebral blood perfusion measurements using arterial spin labeling: accounting for capillary water permeability. Magn Reson Med. 2002;48:27–41. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cao Y, Brown SL, Knight RA, Fenstermacher JD, Ewing JR. Effect of intravascular-to-extravascular water exchange on the determination of blood-to-tissue transfer constant by magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53:282–293. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buckley DL, Kerslake RW, Blackband SJ, Horsman A. Quantitative analysis of multi-slice Gd-DTPA enhanced dynamic MR images using an automated simplex minimization procedure. Magn Reson Med. 1994;32:646–651. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910320514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Faranesh AZ, Yankeelov TE. Incorporation of a vascular term into a reference region model for the analysis of DCE-MRI data. Proc ISMRM; 2007. p. 2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Donahue KM, Weiskoff RM, Parmelee DJ, Callahan RJ, Wilkinson RA, Mandeville JB, Rosen BR. Dynamic Gd-DTPA enhanced MRI measurement of tissue cell volume fraction. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:423–432. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baudelet C, Cron GO, Gallez B. Determination of the maturity and functionality of tumor vasculature by MRI: correlation between BOLD-MRI and DCE-MRI using P792 in experimental fibrosarcoma tumors. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:1041–1049. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ceelen W, Smeets P, Backes W, Van Damme N, Boterberg T, Demetter P, Bouckenooghe I, De Visschere M, Peeters M, Pattyn P. Noninvasive monitoring of radiotherapy-induced microvascular changes using dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI) in a colorectal tumor model. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:1188–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li KL, Wilmes LJ, Henry RG, Pallavicini MG, Park JW, Hu-Lowe DD, McShane TM, Shalinsky DR, Fu YJ, Brasch RC, Hylton NM. Heterogeneity in the angiogenic response of a BT474 human breast cancer to a novel vascular endothelial growth factor-receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor: assessment by voxel analysis of dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;22:511–519. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wolf AP, Dewey SL, Schlyer DJ, MacGregor RR, Hitzemann R, Bendriem B, Gatley SJ, Christman DR. Graphical analysis of reversible radioligand binding from time-activity measurements applied to [N-11C-methyl]-(−)-cocaine PET studies in human subjects. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1990;10:740–747. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1990.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lammerstma AA, Hume SP. Simplified reference tissue model for PET receptor studies. Neuroimage. 1996;4:153–158. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1996.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bertoldo A, Peltoniemi P, Oikonen V, Knuuti J, Nuutila P, Cobelli C. Kinetic modeling of [(18)F]FDG in skeletal muscle by PET: a four-compartment five-rate-constant model. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;281:E524–E536. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.281.3.E524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang SC, Wu HM, Shoghi-Jadid K, Stout DB, Chatziioannou A, Schelbert HR, Barrio JR. Investigation of a new input function validation approach for dynamic mouse microPET studies. Mol Imaging Biol. 2004;6:34–46. doi: 10.1016/j.mibio.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roberts C, Buckley DL, Parker GJM. Comparison of errors associated with single- and multi-bolus injection protocols in low-temporal-resolution dynamic contrast-enhanced tracer kinetic analysis. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:611–619. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]