Abstract

Exercise training (ET) causes functional and morphologic changes in normal and injured brain. While studies have examined effects of short-term (same day) training on functional brain activation, less work has evaluated effects of long-term training, in particular treadmill running. An improved understanding is relevant as changes in neural reorganization typically require days to weeks, and treadmill training is a component of many neurorehabilitation programs.

Adult, male rats (n=10) trained to run for 40 min/day, 5 days/week on a Rotarod treadmill at 11.5 cm/sec, while control animals (n=10) walked for 1 minute/day at 1.2 cm/sec. Six weeks later, [14C]-iodoantipyrine was injected intravenously during treadmill walking. Regional cerebral blood flow-related tissue radioactivity was quantified by autoradiography and analyzed in the three-dimensionally reconstructed brain by statistical parametric mapping.

Exercised compared to nonexercised rats demonstrated increased influence of the cerebellar-thalamic-cortical (CbTC) circuit, with relative increases in perfusion in deep cerebellar nuclei (medial, interposed, lateral), thalamus (ventrolateral, midline, intralaminar), and paravermis, but with decreases in the vermis. In the basal ganglia-thalamic-cortical circuit significant decreases were noted in sensorimotor cortex and striatum, with associated increases in the globus pallidus. Additional significant changes were noted in the ventral pallidum, superior colliculus, dentate gyrus (increases), and red nucleus (decreases).

Following ET, the new dynamic equilibrium of the brain is characterized by increases in the efficiency of neural processing (sensorimotor cortex, striatum, vermis) and an increased influence of the CbTC circuit. Cerebral regions demonstrating changes in neural activation may point to alternate circuits, which may be mobilized during neurorehabilitation.

Keywords: brain mapping, cerebral blood flow, plasticity, exercise, motor training, rehabilitation

1. Introduction

Past work suggests that exercise training (ET) causes functional and morphologic changes within several motor areas, including the motor cortex (Adkins et al., 2006; Kleim et al., 2002; McCloskey et al., 2001), basal ganglia (Conner et al., 2003; Graybiel, 2005; Kelley et al., 2003), cerebellum (De Zeeuw and Yeo, 2005; Kleim et al., 1998; Kleim et al., 1997), and red nucleus (Murakami et al., 1982; Nakamura et al., 1974; Tsukahara et al., 1975). Recently attention has been drawn to the fact that the type of task and the way it is performed has different effects on the brain. Whereas skill training of complex finger sequences may result in functional increases in neural activation during finger tasks, prolonged training involving overtrained movements results in a relative deactivation (reviewed in (Munte et al., 2002)), suggesting that extensive training results in a more efficient way to control these movements. Similar findings have been made after training subjects on skilled ankle (Perez et al., 2004) or tongue tasks (Schieber, 2001).

Different terminologies have been used to describe different forms of ET. A distinction has been made between tasks that require a high amount of attentional guidance (i.e. skilled training) and those that don’t (overlearned, automatic, or endurance based), and each has been linked with different patterns of functional brain activation (reviewed in (van Eimeren and Siebner, 2006), and (Adkins et al., 2006)). Others have made the distinction between training that is internally or externally guided and have proposed the recruitment of different motor circuits based on this distinction (Lewis et al., 2007). In the former, there is volitional initiation of movement, whereas in the latter movement is guided through external cues. In particular, physical therapy guided by externally placed visual or auditory cues is known to be beneficial for the gait and balance of patients with Parkinson’s Disease (Freeman et al., 1993; Thaut et al., 1996). Lewis et al. (Lewis et al., 2007) and others (Debaere et al., 2003; Taniwaki et al., 2003; Taniwaki et al., 2006) have highlighted the dominance of the cerebellar-thalamic-cortical circuit (CbTC) during the performance of externally guided motor movement, and contrasted this with the dominance of the basal ganglia-thalamic-cortical (BTC) circuit during the performance of internally guided motor movements. It has been proposed that BTC and CbTC circuits are in balance. During initial learning, at a time when motor movements are largely internally guided, the BTC circuit predominates. As learning progresses and becomes automatic or externally guided, the influence of this circuit diminishes and that of the CbTC circuit predominates.

Significant performance improvements can be seen after only brief exposure to ET, however, the changes in cortical reorganization, typically require days to weeks, and occur only after a behavioral asymptote has been achieved (Kleim et al., 2000). While several studies have examined the effects of short-term (same day) exercise training of finger exercises has on subsequent functional brain activation, few studies have examined the effects long-term exercise, in particular treadmill training, has on functional brain activation. A better understanding of this is relevant in so far as treadmill exercise is a key component of many neurorehabilitation programs. In our study, we compared functional brain activation elicited during walking in rats exposed to 6 weeks of treadmill exercise to those with minimal treadmill exposure. Because treadmill training is dominantly an externally guided endurance task, we hypothesized that differences would be most apparent in the CbTC circuit.

2. Results

Significant group differences in regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) obtained after statistical parametric mapping are shown in the form of significant T-score differences mapped onto select coronal sections of the rat brain (Fig. 1). A comprehensive list of significant group differences is shown in Table 1 (P < 0.01). Figure 2 places our results into the context of the BTC and CbTC circuits.

Figure 1.

Regions of statistically significant differences of functional brain activation in exercised (n = 10) and nonexercised (n = 10) rats during treadmill walking. Depicted is a selection of representative coronal slices (anterior– posterior coordinates relative to bregma). Colored overlays show statistically significant positive (red) and negative (blue) differences (voxel level, P < 0.05, clusters > 100 contiguous voxels). Line drawings have been adapted from those from the Paxinos and Watson (2005) rat atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 2005) with the permission of Elsevier: 2Cb, 3Cb (2nd and 3rd cerebellar lobules), Au (auditory cortex), CA3 (hippocampus CA3 region), Ce (central nucleus of the amygdala), Cg1 (cingulate cortex area 1), cp (cerebral peduncle), CPu (striatum), DEn (dorsal endopirform nucleus), DG (dorsal geniculate of the hippocampus), DLEnt (dorsolateral entorhinal cortex), DMTg (dorsomedial tegmental area), DPGi (dorsal paragigantocellular nucleus), GPE (external globus pallidus), GPI (internal globus pallidus), Hb (Habenula), IRT (intermediate reticular nucleus), IntA (interposed cerebellar nucleus), Lat (lateral or dentate cerebellar nucleus), M1, M2 (primary, secondary motor cortex), MD (medial thalamic nucleus), MeD (medial or fastigial cerebellar nucleus), PeFLH (perifornical part of the lateral hypothalamus), PF (parafascicular thalamus), PnC (pontine reticular nucleus, caudal), RN (red nucleus), RS (retrosplenial cortex), S1HL (primary somatosensory cortex, hindlimb), S2 (secondary somatosensory cortex), SC (superior colliculus), Sim A (simple lobule of the cerebellum), VL (ventrolateral thalamus), ZI (zona incerta),

TABLE 1. Regions of statistically significant differences of functional brain activation during a treadmill challenge between exercised and nonexercised rats.

Significant increases or decreases are noted, respectively, for the right and left hemispheres. Significance is shown at the voxel level (P < 0.01) for clusters > 100 contiguous voxels. Abbreviations are taken from the Paxinos and Watson rat atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 2005).

| Cortex | R/L |

|---|---|

| Auditory (Au) | − / − |

| Cingulate (Cg1) | − / − |

| Motor, primary, secondary (M1, M2) | − / − |

| Prelimibc (PrL) | − / − |

| Somatosensory, primary, forelimb, hindlimb (S1FL, S1HL) | − / − |

| Somatosensory, secondary (S2) | − / − |

| Entorhinal, dorsolateral (DLEnt) | + / + |

| Retrosplenial (RS) | + / + |

| Subcortex | |

| Caudate putamen, anterior lateral, anterior dorsolateral (CPu) | − / − |

| Cerebellum, 1–4th lobule of vermis (1Cb-4Cb) | − |

| Hypothalamus, lateral, dorsal, lateral perifornical (LH, DA, PeFLH) | − / − |

| Red n. (RN, parvicellular, magnocellular) | − / − |

| Septum, medial (MS) | − |

| Zona incerta (ZI) | − / − |

| Amygdala, basolateral, central, lateral, medial posterior (BL, Ce, La, MeP) | + / + |

| Cerebellum, interposed n. (IntA), medial n. (fastigial n., Med), lateral n. (dentate, Lat) | + / + |

| Cerebellum, simple lobule A (Sim A (intermediate lobe)) | + / + |

| Cingulum (Cg) | + / + |

| Endopiriform n., dorsal (DEn) | + / + |

| Globus pallidus, external, internal (GPE, GPI (entopeduncular n.)) | + / + |

| Habenula (Hb) | / + |

| Hippocampus, dentate gyrus, CA3, fimbria (DG, CA3, fi) | + / + |

| Internal capsule, cerebral peduncle (ic, cp) | + / + |

| Paragigantocellular n., dorsal (DPGi) | + / + |

| Pedunculopontine tegmental nuclear area (PTg) | / + |

| Periaqueductal gray, lateral, ventrolateral (lPAG, vlPAG) | + / + |

| Pontine reticular n., caudal part (PnC) | + / + |

| Reticular formation, mesencephalic (mRt) | / + |

| Reticular n., intermediate alpha part (lRtA) | + / + |

| Septal complex, lateral (Sfi, LS) | + / + |

| Septohippocampal n. (SHi) | + |

| Subthalamic n. (STN) | / + |

| Superior cerebellar peduncle (scp) | + / + |

| Superior colliculus (SC) | + / + |

| Tegmental area, dorsomedial (DMTg) | + / + |

| Thalamus, intralaminar (centromedial, CM; central lateral, CL; paracentral, PC; parafascicular, PF) | + / + |

| Thalamus, mediodorsal (MD) | + / + |

| Thalamus, midline (intermediodorsal, IMD; retrouniens, Re; rhomboid, Rh) | + / + |

| Thalamus, ventrolateral (VL) | + / + |

| Trigeminal n., motor part (5) | + / + |

| Ventral pallidum (VP) | / + |

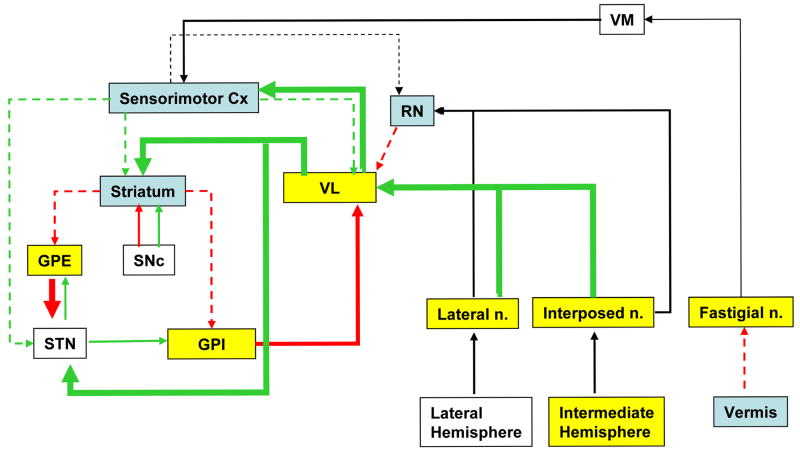

Figure 2.

Summary of the significant changes in functional brain activation between exercised and nonexercised rats during treadmill walking, as they pertain to the basal ganglia-thalamic-cortical (BTC) and cerebellar-thalamic-cortical (CbTC) circuits. Yellow shading indicates a relative increase in regional cerebral perfusion, while blue denotes a relative decrease. Green and red arrows, respectively, denote excitatory or inhibitory neural connections based on review of the literature. Proposed relative increases in input/output are shown by solid, wide arrows, while decreases are shown by stippled arrows. GPE (external globus pallidus), GPI (Internal globus pallidus), RN (red nucleus), STN (subthalamic nucleus), VL (ventrolateral thalamus), VM (ventromedial thalamus). Adapted from DeLong and Wichmann (DeLong and Wichmann, 2007) and Warner (Warner, 2001).

Exercised compared to nonexercised rats showed an attenuation of functional activation in primary and secondary motor cortex (M1, M2), dorsal cingulate and prelimbic cortex (Cg1, PrL), primary somatosensory cortex of the hind- and forelimbs (S1HL, S1FL), secondary somatosensory cortex (S2) and auditory cortex (Au). Increases were limited to dorsolateral entorhinal (DLEnt) and retrosplenial (RS) cortex.

In the subcortex, relative increases in rCBF in exercised compared to nonexercised rats, were increased bilaterally, but frequently were accentuated in the left hemisphere. Within the motor circuit, increases were noted in the deep cerebellar nuclei (interposed, IntA; medial, Med; lateral, Lat), cerebellar simple lobule A (paravermis, SimA), the external and internal globus pallidus (GPE, GPI), the intralaminar (centromedial, CM; central lateral, CL; paracentral, PC; parafascicular, PF), midline (intermediodorsal, IMD; reuniens, Re; rhomboid, Rh), ventrolateral (VL), and mediodorsal (MD) thalamic nuclei, and associated motor regions including the superior colliculus (SC) and ventral pallidum (VP). Decreases within the motor circuit were noted in the striatum (anterior lateral, anterior dorsolateral caudate putamen, CPu), the midline cerebellum (lobules 1-4, 1Cb-4Cb), and red nucleus (RN). Additional significant differences are outlined in table 1.

ROI analysis confirmed significant group differences in the primary and secondary motor cortex, external globus pallidus, caudate putamen, ventrolateral thalamus, vermis, and the medial and interposed nuclei (P < 0.05). ROI analysis of the intermediate cerebellar lobe and lateral cerebellar nucleus showed a nonsignificant trend (P < 0.09), which may reflect the difficulty in consistent manual placement of an ROI on these small structures. There were no statistical differences between the locomotor and control group in nontransformed cerebral blood flow tracer distribution (CBF-TR) or z scores of CBF-TR calculated by slice or globally across all cortical regions.

3. Discussion

Long-term ET elicited plastic changes in the brain resulting in changes in functional activation, both at the level of the CbTC and BTC circuits. The new dynamic equilibrium of the brain was characterized by an increased recruitment of the CbTC circuit, with increases in relative perfusion at the level of the deep cerebellar nuclei (fastigial, interposed, lateral), thalamus (ventrolateral, centromedial), and paravermis, but with decreases in the vermis. The activation of the CbTC circuit may have compensated for functional changes in the BTC circuit, in particular significant decreases in activation noted in sensorimotor cortex and the striatum, and associated increases in the external and internal globus pallidus.

Brain regions that showed significant functional differences in response to ET were many of the same brain regions that have previously been shown to be activated/deactivated acutely during Rotarod walking as compared to the resting state (Holschneider et al., 2003; Nguyen et al., 2004). Prolonged ET, compared to no ET, resulted in relative decreases in rCBF during treadmill walking in several cortical areas (Cg1, M1, M2, PrL, S1FL, S1HL, S2), the dorsolateral striatum, and cerebellar vermis. These changes were opposite to the increases in these regions noted in our prior work during locomotion as compared to the resting state. This finding is consistent with the notion that ET results in a reorganization of neural circuits in many of the same regions activated during an acute motor challenge, and suggests that in these regions, ET results in increased efficiency of neural processing. Likewise, whereas in the current study prolonged ET, compared to no ET, resulted in relative increases in rCBF during treadmill walking in the GPE, superior colliculus (SC), thalamus (VL, CM), trigeminal nucleus (5), and amygdala, these same regions showed decreases in prior work during locomotion as compared to the resting state. These differences may reflect both the reorganization of neural activity downstream from the changes in neural efficiency noted above (e.g. increases in rCBF in the GPE in response to decreases in rCBF in motor cortex and striatum, as discussed below), as well as the recruitment of additional brain regions (e.g. increases in rCBF at the level of the thalamus in response to the increased influence by the CbTC circuit).

3.1. BTC Circuit

The classic view of basal ganglia connections is based upon the identification of two distinct striato–pallidal pathways (Fig. 2) (Albin et al., 1989; Alexander and Crutcher, 1990; Alexander et al., 1990). Though this model is currently recognized to represent a simplification of the neural circuitry (Obeso et al., 2000), in it a ‘direct’ pathway leads from the striatum straight to the globus pallidus pars interna (GPI, entopeduncular nucleus) and other basal ganglia output nuclei, while an ‘indirect’ pathway first transmits to the globus pallidus pars externa (GPE) and the subthalamic nucleus (STN) prior to projecting to the GPI. The GPI is considered to be the major outflow nucleus of the basal ganglia. Terminals from GPI are found in the ipsilateral ventral anterior/ventrolateral (VA/VL) and ventromedial (VM) thalamic nuclei, lateral habenular and centromedian-parafascicular complex (Finkelstein et al., 1996). Efferent fibers from the VL-VM nuclei project to the cortex. Though questions remain regarding the exact pattern of organization of the motor cortical areas in rodents, it has been suggested that the rostral forelimb area in the rat may be an equivalent of the premotor or supplementary motor area in the primate (Neafsey et al., 1986; Rouiller et al., 1993).

Exercised rats showed significantly less activation than nonexercised rats in response to a locomotor challenge in motor, cingulate, prelimbic and somatosensory cortex of the fore- and hindlimbs, as well as in the striatum. Within the striatum this relative ‘deactivation’ was noted prominently dorsolaterally. This observation is in agreement with histologic evidence in rats that demonstrates specific projections from forelimb and hindlimb areas of the somatosensory cortex to the dorsolateral quarter of the striatum (Cospito and Kultas-Ilinsky, 1981; Ebrahimi et al., 1992), as well as evidence of functional activation of this region in response to treadmill walking or a manual reaching task (Greenough, 1984; Holschneider et al., 2003; Nguyen et al., 2004). This localization may represent increased efficiency of neural processing of a specific corticostriatal loop.

Our results suggest that decreased activation in the striatum and cortex was associated with an increased activation in the GPI (Fig. 2). This is consistent with a decrease in the well-documented inhibitory striatal projections to the GPI within the direct basal ganglia circuit. Decreased activation of the striatum also was associated with increased activation of the GPE. This finding is consistent with a decrease in inhibitory input of the striatum within the indirect striatal-pallidal circuit. However, the increased, largely inhibitory output from the GPE did not result, as expected based on the BTC circuit, in decreased activation of the STN. A possible explanation is that such increased inhibitory output was countered by increased activation of the STN by the VL from input originating in the cerebellar-thalamic circuit (see Fig. 2). At the level of the VL, competing influences also appeared to be present. On one hand, increased activation of the GPI would result, as predicted, in increased inhibition of the VL. On the other hand, increased activation of the deep cerebellar nuclei counteracted this, resulting in a net activation of the VL (see discussion below).

3.2. CbTC circuit

The CbTC circuit is a physically segregated, but functionally distinct, motor circuit of the brain that is task-specifically recruited. The CbTC circuit has been implicated in somatosensory integration (Manzoni, 2007), information updating (Bonnefoi-Kyriacou et al., 1998), and may have to be intact for the acquisition of motor coordination and spatial learning (Joyal et al., 1996). The precise nature of the influence of the CbTC pathway has remained elusive but numerous studies suggest that it provides the motor cortex with information pertinent to the timing, velocity or force of movement (reviewed in (Horne and Butler, 1995)). In particular, the vermis and intermediate lobes are felt to play an important role in the control of the actual execution of movement by correcting for deviations from an intended movement through feedback comparison with information coming from the spinal cord (Barlow, 2002; Shumway-Cook and Woollacott, 2001). They also modulate muscle tone through output from the medial (fastigial) and interposed nucleus.

Several lines of evidence suggest that the CbTC circuit is capable of motor adaptation (reviewed in (Aumann, 2002)). Cerebellar-thalamic synapses exhibit structural characteristics suggestive of a capacity for both formation of new synapses, and alterations in efficacy of transmission across existing synapses. Long-term potentiation can be evoked across cerebellar-thalamic synapses in vitro, at least in young animals. Evidence for synaptic plasticity associated with motor adaptation has been noted at the level of the VL (Aumann and Horne, 1999), as well as primary motor cortex (Meftah and Rispal-Padel, 1994; Rispal-Padel and Meftah, 1992).

Lewis et al. (Lewis et al., 2007) and others (Debaere et al., 2003; Taniwaki et al., 2003; Taniwaki et al., 2006) have proposed that in the normal condition, externally guided tasks are primarily processed through the CbTC pathway, with the secondary involvement of the BTC pathway, whereas for internally guided tasks this relationship is reversed. Consistent with this notion, and the fact that 6 weeks of treadmill running represents an externally guided, overlearned motor task, our results showed significant movement adaptation of the CbTC circuit during ET.

Within the CbTC circuit, exercised compared to nonexercised rats showed increased activation of the deep cerebellar nuclei. Our study showed activation of the intermediate cerebellar hemisphere, the interposed nucleus and lateral (dentate) cerebellar nuclei and the VL. Steriade has proposed this to constitute a separate pathway within the CbTC circuit (Steriade, 1995). It has been proposed that neurons from the interposed cerebellar nucleus provide an excitatory connection to the VA-VL thalamic nuclei and from there project to motor cortex (Aumann et al., 1998; Na et al., 1997; Shinoda et al., 1985; Steriade, 1995). In our study, the vermis showed significant deactivation, which in light of prior evidence of inhibitory connections of the vermis onto the medial (fastigial) nucleus (Dean, 1995; Ohtsuka, 1988; Xu and Frazier, 2002), might explain the activation noted in the medial nucleus.

3.3. Thalamus

The ventrolateral (VL) and ventromedial nuclear (VM) complex of the thalamus (VL-VM) can be considered the main motor thalamic relay to the cerebral cortex, constituting a point of convergence for neural pathways from the cerebellar and extrapyramidal system (Groenewegen and Witter, 2004). Patterns of termination of cerebellar and basal ganglia efferents in the rat have been shown to be strictly segregated, although partial overlap of the projections exists (Deniau et al., 1992). Cerebellar efferent fibers predominantly extend to all parts of VL, as well as to intralaminar nuclei, such as the centrolateral nucleus (CL), and the VM (Aumann et al., 1994; Donoghue and Parham, 1983; Haroian et al., 1981), although the latter mainly receives also non-overlapping basal ganglia input (Deniau et al., 1992). The largest volume of VA/VL is devoted to the cerebellar influences on the motor thalamocortical system. Basal ganglia inputs to the VA/VL are fewer and are found primarily within the VA (Sakai et al., 1998). Efferent fibers from the VL then project in a topographic fashion to primary motor cortex, while the VM projects more widely to the neocortex (Herkenham, 1979).

Exercised compared to nonexercised rats showed significant activation of the VL. Because the VL lies directly dorsal to the VM, we cannot fully rule out activation in the peripheral border of the VM. However, no evidence was found of central VM activation (for instance, in areas directly medial to the tips of the medial lemniscus, where the VM is largest). Neither was there any evidence of activation in the VA. This suggests that group differences in functional activation in our study at the level of the thalamus were dominantly determined by the cerebellar-thalamic projections, rather than pallidal-thalamic projections.

Exercised compared to nonexercised rats showed significant activation of intralaminar (centromedial, CM; central lateral, CL; paracentral, PC, parafascicular, PF) and midline thalamic nuclei (intermediodorsal, IMD; reuniens, Re; rhomboid, Rh). The PC and the CL and the anterior part of the CM, is considered to have its predominant connections with the dorsal striatum and the anterior cingulate cortex (Groenewegen and Witter, 2004). This group of nuclei, at least in human studies, is thought to be involved in executive functions, in particular cognitive awareness (Van der Werf et al., 2002). The RE and the Rh and the posterior part of the CM, only sparsely projects to the striatum. Instead, the nuclei in this group have rather widespread and strong projections to superficial and deep layers of motor, gustatory, visceral, insular, and auditory cortical areas. In addition, the RE and, more sparsely, the Rh project to the hippocampus and entorhinal cortices. This group of nuclei is thought to play a role in polymodal sensory awareness (Van der Werf et al., 2002). Posteriorly, the PF primarily projects to basal ganglia structures and, in addition, reaches the sensory and motor cortices. It has been postulated that the PF has an important role in the generation of motor responses following awareness of salient stimuli and, in this way, serves a role in limbic-motor functions (Van der Werf et al., 2002).

Exercised compared to nonexercised rats also showed clear activation of the medial dorsal thalamic nucleus. The functions of this nucleus remain somewhat unclear, although it has long been implemented in learning and memory (Groenewegen and Witter, 2004; Markowitsch, 1982). With regard to the motor circuit, there is some evidence that the MD provides efferent projections to the motor cortex (Matelli and Luppino, 1996; Moran et al., 1982), as well as to striatopallidal structures (Gorbachevskaya and Chivileva, 2004), while receiving afferent input from the ventral pallidum and substantia nigra reticulata (Kuroda et al., 1998).

3.4. Red nucleus

The red nucleus (RN) receives inputs from the sensorimotor cortex, the cerebellum (interposed and lateral nuclei) and spinal cord. The rubrospinal tract has been implicated to be involved in controlling limb movements, both skilled movements of the forelimbs (Whishaw, (Jarratt and Hyland, 1999; Whishaw et al., 1998)), as well as more general limb actions such as locomotion or scratching (Arshavsky et al., 1988; Muir and Whishaw, 2000). The rubral complex functions as an important premotor center, however, the exact nature of how its functions relate to the corticospinal system remains unclear. It has been suggested that the RN may provide a tonic framework against which the motor cortex can produce more precise movements (Whishaw and Gorny, 1996). In addition, the RN may function as a switching device designed for automatization of learned movements (Kennedy, 1990). The RN may also be involved in long-term plastic events such as the processes that underlie functional motor readaptation following lesions of the CNS (Murakami et al., 1982; Nakamura et al., 1974; Tsukahara et al., 1975).

In our study, exercised compared to nonexercised rats showed decreases in rCBF in the RN. This suggests a decreased contribution by this premotor center and may be related to decreased input by the sensorimotor cortex.

3.5. Superior Colliculus

In addition to its role in the visual orientation of animals, the SC has been implicated in a wide number of functions. Of possible relevance to the current study is prior work suggesting a role for the SC in turning and locomotor exploration, navigation and spatially guided movements (Sefton et al., 2004). Complex circuitries linking the multimodal intermediate and deep tectal layers with cerebellar nuclei, SN, and basal ganglia may enable the SC to participate in the selection of appropriate (and suppression of competing or inappropriate) motor programs in response to novel stimuli (Niemi-Junkola and Westby, 1998; Niemi-Junkola and Westby, 2000).

Exercised compared to nonexercised rats showed bilateral relative increases in rCBF in the SC during walking. In contrast, an earlier study of ours in rats showed decreases in rCBF in the SC during walking compared to the resting state (Holschneider et al., 2003; Nguyen et al., 2004). Together, this suggests that chronic exercise may attenuate decreases in the activation of the SC elicited during treadmill walking. This may occur possibly through activation of the deep cerebellar nuclei which provide an excitatory projection to the SC (May and Hall, 1986; Westby et al., 1993; Westby et al., 1994).

3.6. Hippocampus

Exercise training is well-established to promote neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus, with associated increases of trophic factors, alterations in dendritic structure, enhanced expression of long-term potentiation, and improvement on learning and memory on hippocampal-dependent tasks (O’Callaghan et al., 2007; Olson et al., 2006; Pereira et al., 2007; Uda et al., 2006). Such neurogenesis has been reported in rats, as well as human subjects, in response to treadmill training and is dominantly seen in the dentate gyrus. In agreement with this, our study showed exercised compared to nonexercised rats to with significant increases in rCBF in the dentate gyrus, CA3 region and hippocampal fimbria.

3.7. Motor Training and Functional Imaging

Activation patterns associated with practice and repetition of motor movements remain incompletely understood, with both no change, increases and decreases reported. Factors influencing this heterogeneity include the type of ET, variability in the duration and intensity of ET exposure, timing of the imaging in relation to training, and the nature of the activational procedure during which brain imaging is performed. Of greatest consistency in this literature are human studies comparing functional brain activation of trained musicians with novices during the performance of finger sequences (reviewed in (Munte et al., 2002)). Here the extensive skill training of the experts compared to novices results in enlargement of the digit map, as well as neuroanatomic enlargements. However, in the experts, the magnitude of the activational response to simple, overpracticed finger tasks is attenuated relative to that seen in novices. This has been reported for motor cortex, basal ganglia, cingulate cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, the cerebellar vermis, and substantia nigra, and suggests that extensive training results in a more efficient way to control these movements (Jancke et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2004; Koeneke et al., 2004). In nonmusicians, attenuation of activation in sensory and motor cortex as subjects become more practiced on finger tasks has been also suggested earlier by Friston et al. (Friston et al., 1992), and more recently by Morgen et al. (Morgen et al., 2004). When finger sequences are prelearned, a lesser and more circumscribed activation has been noted in the cerebellum (vermis and hemispheres) (Jenkins et al., 1994), and in the striatum, cingulate gyrus and thalamus (Tracy et al., 2001).

We did not observe any significant changes in parietal cortex in response to treadmill training. Several human studies employing finger training exercises have reported significant changes here in response to learning. These studies typically have ascribed these differences to perceptual learning (Morgen et al., 2004) or planning or the complex spatial and timing components of musical performance (Lotze et al., 2003). This difference may reflect the difference between our treadmill task and the tasks used in these other studies.

3.8. Implications for Neurorehabilitation

Given the inherent balance between the BTC and CbTC circuits, conditions that show deficits in the BTC circuit (e.g. Parkinson’s Disease), may elicit increased recruitment of the CbTC circuit, as a means of partial compensation. In the PD patient, this enhanced recruitment in the CbTC circuit may be exaggerated during EG tasks, and may explain the observation that PD patients compared to normal controls tend to show increased activity in motor cortical areas and in the cerebellum during the performance of overlearned motor tasks. Conversely, motor cortical areas tend to be underactive if the motor task demands a high amount of internal guidance (reviewed in (van Eimeren and Siebner, 2006)).

ET is currently being used for the improvement of motor function in PD subjects. Results from the current study are consistent with the viewpoint that prolonged treadmill training enhances activation of the CbTC circuit. At the same time, ET acts to diminish the inhibitory effects the striatum has on the GPE, resulting in a relative enhancement of the GPE’s own inhibitory effects on the subthalamic nucleus. Such an effect could, in principle, act to ‘normalize’ the overactivity of the STN that has been typically reported in PD subjects (Obeso et al., 2000). Thus, treadmill training, in addition to boosting activity in CbTC and cerebellar-thalamic-striatal circuits, may act to ‘normalize’ activity within the indirect loop of the classical circuit.

3.9. Limitations

The Rotarod treadmill task differs from the horizontal treadmill in that the former may require a greater measure of active balance than the latter. Future work may need to examine whether the increased recruitment of the CbTC pathway is seen also after chronic exercise on the horizontal treadmill. It must be noted, while increases in rCBF may suggest a predominant ‘activation’ in specific brain regions such as, for example, the VL, this pattern determined largely by cerebellar-thalamic efferents might co-exist or even mask decreases in rCBF (or ‘deactivation’) in a subset of neural fibers reaching the VL from the GPI. Detection of such differences would be considered below the spatial resolution of our method of brain mapping (~100 μm).

Cerebral blood flow, being a proxy measure for neuronal activity, operates under several assumptions (Gsell et al., 2000; Keri and Gulyas, 2003; Mintun et al., 2001). Unresolved issues include the role of excitatory compared to inhibitory neurotransmitters in altering brain perfusion and metabolism, and the fact that hemodynamic changes may be driven by subthreshold synaptic activity. In addition, there are the limits of proxy measures such as CBF have in detecting changes in spatial and temporal neural processing, in which the overall energy demands may remain unchanged.

3.10. Conclusion

Long-term ET elicits plastic changes in the brain whose functional activation patterns during a locomotor challenge represent a new dynamic equilibrium between separate motor circuits. Treadmill training on the Rotarod results in a combination of increases in the efficiency of neural processing (sensorimotor cortex, striatum, vermis) and an increased influence of the CbTC circuit. This may represent a response to changes in activity noted in the BTC circuit, as well as a way for the brain to shift its control from a motor task that in the early stages of learning requires skill and internal guidance, to one which over time becomes increasingly externally guided and automatic.

Future studies evaluating the effects ET has on neural activational patterns in animal models or patients suffering from brain injury will need to consider that ET itself results in neuroplastic changes in the normal brain. Hence, comparison of the effects of ET on the injured brain would benefit from the use of ‘exercised’ controls, not simply nonexercised, ‘normal volunteers’. Identification of brain regions demonstrating changes in neural activation in response to ET may inform the design of future neurorehabiliative programs and may provide a basis for rational surgical or pharmacologic interventions.

4. Experimental Procedures

4.1 Animals

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (350–375 g, Harlan Sprague –Dawley Labs, Indianapolis, IN) were used under a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Southern California in adherence with the guidelines for the care and use of animal care (National Research Council of the National Academies, 2003).

4.2 Exercise Training

Rats (n = 10) were trained 5 days per week for 6 weeks on a Rotarod treadmill (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH, U.S.A.). Animals trained in groups of 4 on a scored, cylindrical spindle of 7.3 cm diameter, each separated by a series of lateral, opaque plastic panels. Training was initialized at low speed (10 rpm, 3.8 cm/sec) for 15 min/day for three days. Thereafter, the duration of running was increased to 40 min/day, and the speed was gradually increased from 10 rpm to 30 rpm (11.5 cm/sec) in daily increments of 5-rpm (1.9 cm/sec). The rats continued to train for 6 weeks. Control animals (n = 10) were placed 5 days/week on the Rotarod for 1 minute at 3 rpm (1.2 cm/sec.).

4.3. Cannulation of the External Jugular Vein

Five days prior to brain mapping and following the day’s training, rats were anesthetized (isoflurane 1.5% maintenance). Using aseptic technique, a 5-Fr silastic catheter was inserted into the external jugular vein and advanced into the superior vena cava. The catheter’s distal end was tunneled subcutaneously from the ventromedial aspect of the neck to the infrascapular region, externalized and then capped with a stainless steel plug. Catheters were flushed every other day with (0.8 ml of 0.9% saline, followed by 0.1 ml of a lok solution of 20 U/ml heparin in 0.9% saline). Rats continued their daily exercise training for four days postoperatively.

4.4. Injection of the CBF radiotracer, [14C]-iodoantipyrine

Catheters were connected to 3.5 Fr silastic tubing loaded sequentially with 125 μCi/kg of [14C]-iodoantipyrine in 300 μl of 0.9% saline (American Radiolabelled Chemicals, MO), followed by pentobarbital (75 mg/kg) and a euthanasia solution (pentobarbital 75 mg/kg, 3 M KCl). All rats were then exposed to slow walking on the Rotarod at a reduced speed of 8 rpm (3.1 cm/sec.). Injection of the tracer occurred by motorized pump at 2.25 ml/min after 2 minutes of treadmill walking. Immediately after bolus injection of the tracer, the euthanasia solution was injected into the circulatory system. This resulted in cardiac arrest within ~10 seconds, a precipitous fall of arterial blood pressure, termination of brain perfusion, and death. This 10 second time window provided the temporal resolution during which the distribution of CBF-TR was mapped (Holschneider et al., 2002). Cerebral blood flow related tissue radioactivity (CBF-TR) was measured by the classic [14C]-iodoantipyrine method (Goldman and Sapirstein, 1973; Patlak et al., 1984; Sakurada et al., 1978). In this method, there is a strict linear proportionality between tissue radioactivity and cerebral blood flow when the radioactivity data is captured within a brief interval (~10 sec.) after the radiotracer injection (Jones et al., 1991; Van Uitert and Levy, 1978).

4.5. Brain slicing and tissue handling

Brains were rapidly removed, flash frozen in dry ice/methylbutane (−55°C), embedded in OCT™ compound (Miles Inc., Elkhart, IN), and stored in a freezer at −70°C. Brains were subsequently cut in a cryostat at − 18°C in 20-μm-thick coronal sections between bregma +4.5 mm and −11.4 mm. Sections were heat-dried on glass slides and exposed for 2 weeks at room temperature to Kodak Ektascan film in spring-loaded x-ray cassettes along with 16 radioactive 14C standards (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Autoradiographs were placed on a voltage stabilized light box (Northern Lights Illuminator, InterFocus Ltd, England), imaged with a Retiga 4000R charge-coupled device monochrome camera (Qimaging, Canada) and a 60 mm Micro-Nikkor macro lens (Nikon, USA), digitized on an 8-bit gray scale using Qcapture Pro 5.1 (Qimaging, Canada) using an ATI FireGL V3100 128 MB digitizing board on a microcomputer.

4.6. Image Analysis

The process of aligning slices to reconstruct the three dimensional (3D) brain, the spatial normalization and the smoothing of individual brains has been described in our earlier work (Nguyen et al., 2004). In brief, fifty-four digitized, serial coronal sections (bregma +4.5 mm to −11.4 mm, interslice distance 300 μm) were selected and stored as two-dimensional arrays of 41 μm2 pixels. Adjacent sections were aligned both manually and using TurboReg (Thevenaz et al., 1998), an automated pixel-based registration algorithm, with final voxel dimensions of 0.041 × 0.041 × 0.3 mm3.

4.6.1 Creation of the rat brain template

Individual 3D images were spatially normalized using a 12- parameter, nonlinear affine transformation into a standard space defined by a single, ‘artifact free’ rat brain, followed by a nonlinear spatial normalization using the low-frequency basis functions of the three-dimensional discrete cosine transform (7×7×8 in each direction for 1176 parameters), plus a linear intensity transformation (4 parameters).

4.6.2. SPM Analysis

Significant group differences in regional CBF-related tissue radioactivity (CBF-TR) were determined by statistical parametric mapping. Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM2) (Friston, 1995; Friston et al., 1990), which was introduced in 1991, (Wellcome Dept. of Cognitive Neurology, Institute of Neurology, London, UK), is a collection of tools available in the public domain for basic visualization and voxel-based analysis of neuroimages (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/). SPM was developed for analysis of imaging data in humans and has been recently adapted by us for use in rat brain autoradiographs (Nguyen et al., 2004). Global differences in the absolute amount of radiotracer delivered to the brain were adjusted by the SPM software in each animal by scaling the voxel intensities so that the mean intensity for each brain was the same. Voxels for each brain failing to reach a specified threshold (80%) were masked out to eliminate the background and ventricular spaces.

Using SPM, we implemented the Student’s t-test (unpaired) at each voxel, testing the null hypothesis that there is no effect of group, i.e. no difference between [14C]-iodoantipyrine CBF tracer distributions. Maps of positive and negative t values were separately analyzed. A significance threshold was set at P < 0.01 (uncorrected for multiple comparisons) for individual voxels within clusters of contiguous voxels, and a minimum cluster size of 100 contiguous voxels (extent threshold). Regions determined to be significant at the voxel level were required to show significance in two or more consecutive autoradiographic sections. Group subcortical differences in the distribution of CBF-TR were displayed as color-coded statistical parametric maps superimposed on the brain coronal, transverse and sagittal slices. Brain regions were identified using an anatomical atlas of the rat brain (Paxinos and Watson, 2005).

4.6.3. Region-of-interest analysis

For purposes of verification of the SPM results, key regions (primary and secondary motor cortex, external globus pallidus, caudate putamen, ventrolateral thalamus, vermis, intermediate cerebellar lobe, deep cerebellar nuclei) underwent a region-of-interest (ROI) analysis, in which ROIs were manually placed on the digitized autoradiographic images. Z-scores were calculated using methods previously reported (Holschneider et al., 2003). Group differences were examined with the Student’s t-test (2-tailed), P < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jonathan Charles for his help with the three-dimensional brain reconstruction, and Drs. Michael Jakowec and Giselle Petzinger for comments regarding the manuscript. Supported by the NIBIB 1R01 NS050171.

ABBREVIATIONS

- 1-4 Cb

1st through 4th cerebellar lobules

- Au

auditory cortex

- BTC

basal ganglia-thalamic-cortical circuit

- CA3

hippocampus CA3 region

- CBF

cerebral blood flow

- CbTC

cerebellar-thalamic-cortical circuit

- Ce

central nucleus of the amygdala

- Cg

cingulated

- Cg1

cingulate cortex area 1

- CL

centrolateral thalamic nucleus

- CM

centromedial thalamic nucleus

- cp

cerebral peduncle

- CPu

striatum

- Den

dorsal endopirform nucleus

- DG

dorsal geniculate of the hippocampus

- DLEnt

dorsolateral entorhinal cortex

- DMTg

dorsomedial tegmental area

- DPGi

dorsal paragigantocellular nucleus

- ET

exercise training

- GPE

external globus pallidus

- GPI

internal globus pallidus

- Hb

Habenula

- IMD

intermediodorsal thalamic nucleus

- IntA

interposed cerebellar nucleus

- IRT

intermediate reticular nucleus

- Lat

lateral or dentate cerebellar nucleus

- M1,M2

primary, secondary motor cortex

- MD

medial thalamic nucleus

- MeD

medial or fastigial cerebellar nucleus

- PC

paracentral thalamic nucleus

- PeFLH

perifornical part of the lateral hypothalamus

- PF

parafascicular thalamic nucleus

- PrL

prelimbic cortex

- PnC

pontine reticular nucleus, caudal

- rCBF

regional cerebral blood flow

- Re

reuinens thalamic nucleus

- Rh

rhomboid thalamic nucleus

- RN

red nucleus

- ROI

region of interest

- RS

retrosplenial cortex

- S1HL

primary somatosensory cortex, hindlimb

- S2

secondary somatosensory cortex

- SC

superior colliculus

- Sim A

simple lobule of the cerebellum, paravermis

- SPM

statisticalparametric mapping

- STN

subthalamic nucleus

- VA

ventral anterior thalamic nucleus

- VL

ventrolateral thalamic nucleus

- VM

ventromedial thalamic nucleus

- VP

ventral pallidum

- ZI

zona incerta

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Classification terms: Other Systems of the CNS, Section: Brain Metabolism and Blood Flow

References

- Adkins DL, Boychuk J, Remple MS, Kleim JA. Motor training induces experience-specific patterns of plasticity across motor cortex and spinal cord. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:1776–82. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00515.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albin RL, Young AB, Penney JB. The functional anatomy of basal ganglia disorders. Trends Neurosci. 1989;12:366–75. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GE, Crutcher MD. Functional architecture of basal ganglia circuits: neural substrates of parallel processing. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:266–71. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90107-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GE, Crutcher MD, DeLong MR. Basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuits: parallel substrates for motor, oculomotor, “prefrontal” and “limbic” functions. Prog Brain Res. 1990;85:119–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arshavsky YI, Orlovsky GN, Perret C. Activity of rubrospinal neurons during locomotion and scratching in the cat. Behav Brain Res. 1988;28:193–9. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(88)90096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aumann TD. Cerebello-thalamic synapses and motor adaptation. Cerebellum. 2002;1:69–77. doi: 10.1080/147342202753203104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aumann TD, Horne MK. Ultrastructural change at rat cerebellothalamic synapses associated with volitional motor adaptation. J Comp Neurol. 1999;409:71–84. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990621)409:1<71::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aumann TD, Ivanusic J, Horne MK. Arborisation and termination of single motor thalamocortical axons in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1998;396:121–30. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980622)396:1<121::aid-cne9>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aumann TD, Rawson JA, Finkelstein DI, Horne MK. Projections from the lateral and interposed cerebellar nuclei to the thalamus of the rat: a light and electron microscopic study using single and double anterograde labelling. J Comp Neurol. 1994;349:165–81. doi: 10.1002/cne.903490202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow JS. The cerebellum and adaptive control. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnefoi-Kyriacou B, Legallet E, Lee RG, Trouche E. Spatio-temporal and kinematic analysis of pointing movements performed by cerebellar patients with limb ataxia. Exp Brain Res. 1998;119:460–6. doi: 10.1007/s002210050361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner JM, Culberson A, Packowski C, Chiba AA, Tuszynski MH. Lesions of the Basal forebrain cholinergic system impair task acquisition and abolish cortical plasticity associated with motor skill learning. Neuron. 2003;38:819–29. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cospito JA, Kultas-Ilinsky K. Synaptic organization of motor corticostriatal projections in the rat. Exp Neurol. 1981;72:257–266. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(81)90221-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Zeeuw CI, Yeo CH. Time and tide in cerebellar memory formation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:667–74. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean P. Modelling the role of the cerebellar fastigial nuclei in producing accurate saccades: the importance of burst timing. Neuroscience. 1995;68:1059–77. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00239-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debaere F, Wenderoth N, Sunaert S, Van Hecke P, Swinnen SP. Internal vs external generation of movements: differential neural pathways involved in bimanual coordination performed in the presence or absence of augmented visual feedback. Neuroimage. 2003;19:764–76. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong MR, Wichmann T. Circuits and circuit disorders of the basal ganglia. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:20–4. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deniau JM, Kita H, Kitai ST. Patterns of termination of cerebellar and basal ganglia efferents in the rat thalamus. Strictly segregated and partly overlapping projections. Neurosci Lett. 1992;144:202–6. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90750-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue JP, Parham C. Afferent connections of the lateral agranular field of the rat motor cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1983;217:390–404. doi: 10.1002/cne.902170404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimi A, Pochet R, Roger M. Topographical organization of the projections from physiologically identified areas of the motor cortex to the striatum in the rat. Neurosci Res. 1992;14:39–60. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(05)80005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein DI, Reeves AK, Horne MK. An electron microscopic tracer study of the projections from entopeduncular nucleus to the ventrolateral nucleus of the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1996;211:33–6. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12713-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman JS, Cody FW, Schady W. The influence of external timing cues upon the rhythm of voluntary movements in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;56:1078–84. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.56.10.1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ. Commentary and opinion: II. Statistical parametric mapping: ontology and current issues. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1995;15:361–70. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1995.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Frith CD, Liddle PF, Dolan RJ, Lammertsma AA, Frackowiak RS. The relationship between global and local changes in PET scans. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1990;10:458–66. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1990.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Frith CD, Passingham RE, Liddle PF, Frackowiak RS. Motor practice and neurophysiological adaptation in the cerebellum: a positron tomography study. Proc Biol Sci. 1992;248:223–8. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1992.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman H, Sapirstein LA. Brain blood flow in the conscious and anesthetized rat. Am J Physiol. 1973;224:122–126. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1973.224.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbachevskaya AI, Chivileva OG. Organization of the thalamic projections of the striopallidum of the dog brain. Neurosci Behav Physiol. 2004;34:519–24. doi: 10.1023/b:neab.0000022641.44459.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graybiel AM. The basal ganglia: learning new tricks and loving it. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:638–44. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenough W. Structural correlates of information storage in the mammalian brain: a review and hypothesis. TINS. 1984;7:229–233. [Google Scholar]

- Groenewegen HJ, Witter MP. Thalamus. In: Paxinos G, editor. The Rat Nervous System. Elsevier Academic Press; San Diego: 2004. pp. 407–453. [Google Scholar]

- Gsell W, De Sadeleer C, Marchalant Y, MacKenzie ET, Schumann P, Dauphin F. The use of cerebral blood flow as an index of neuronal activity in functional neuroimaging: experimental and pathophysiological considerations. J Chem Neuroanat. 2000;20:215–224. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(00)00095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haroian AJ, Massopust LC, Young PA. Cerebellothalamic projections in the rat: an autoradiographic and degeneration study. J Comp Neurol. 1981;197:217–36. doi: 10.1002/cne.901970205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herkenham M. The afferent and efferent connections of the ventromedial thalamic nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1979;183:487–517. doi: 10.1002/cne.901830304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holschneider DP, Maarek JM, Harimoto J, Yang J, Scremin OU. An implantable bolus infusion pump for use in freely moving, nontethered rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H1713–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00362.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holschneider DP, Maarek JM, Yang J, Harimoto J, Scremin OU. Functional brain mapping in freely moving rats during treadmill walking. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 2003;23:925–32. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000072797.66873.6A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne MK, Butler EG. The role of the cerebello-thalamo-cortical pathway in skilled movement. Prog Neurobiol. 1995;46:199–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jancke L, Shah NJ, Peters M. Cortical activations in primary and secondary motor areas for complex bimanual movements in professional pianists. Cognitive Brain Research. 2000;10:177–83. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(00)00028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarratt H, Hyland B. Neuronal activity in rat red nucleus during forelimb reach-to-grasp movements. Neuroscience. 1999;88:629–42. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins IH, Brooks DJ, Nixon PD, Frackowiak RS, Passingham RE. Motor sequence learning: a study with positron emission tomography. J Neurosci. 1994;14:3775–90. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-06-03775.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SC, Korfali E, Marshall SA. Cerebral blood flow with the indicator fractionation of [14C]iodoantipyrine: effect of PaCO2 on cerebral venous appearance time. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1991;11:236–41. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1991.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyal CC, Meyer C, Jacquart G, Mahler P, Caston J, Lalonde R. Effects of midline and lateral cerebellar lesions on motor coordination and spatial orientation. Brain Res. 1996;739:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)00333-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley AE, Andrzejewski ME, Baldwin AE, Hernandez PJ, Pratt WE. Glutamate-mediated plasticity in corticostriatal networks: role in adaptive motor learning. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1003:159–68. doi: 10.1196/annals.1300.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy PR. Corticospinal, rubrospinal and rubro-olivary projections: a unifying hypothesis. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:474–9. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90079-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keri S, Gulyas B. Four facets of a single brain: behaviour, cerebral blood flow/metabolism, neuronal activity and neurotransmitter dynamics. Neuroreport. 2003;14:1097–106. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200306110-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DE, Shin MJ, Lee KM, Chu K, Woo SH, Kim YR, Song EC, Lee JW, Park SH, Roh JK. Musical training-induced functional reorganization of the adult brain: functional magnetic resonance imaging and transcranial magnetic stimulation study on amateur string players. Hum Brain Mapp. 2004;23:188–99. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleim JA, Cooper NR, VandenBerg PM. Exercise induces angiogenesis but does not alter movement representations within rat motor cortex. Brain Res. 2002;934:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02239-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleim JA, Hogg TM, Whishaw IQ, Reidel CN, Cooper NR, VandenBerg PM. Time course and persistence of motor learning-dependent changes in the functional organization of the motor cortex. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 2000;26 [Google Scholar]

- Kleim JA, Swain RA, Armstrong KA, Napper RM, Jones TA, Greenough WT. Selective synaptic plasticity within the cerebellar cortex following complex motor skill learning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1998;69:274–89. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1998.3827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleim JA, Swain RA, Czerlanis CM, Kelly JL, Pipitone MA, Greenough WT. Learning-dependent dendritic hypertrophy of cerebellar stellate cells: plasticity of local circuit neurons. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1997;67:29–33. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1996.3742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeneke S, Lutz K, Wustenberg T, Jancke L. Long-term training affects cerebellar processing in skilled keyboard players. Neuroreport. 2004;15:1279–82. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000127463.10147.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda M, Yokofujita J, Murakami K. An ultrastructural study of the neural circuit between the prefrontal cortex and the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;54:417–58. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MM, Slagle CG, Smith AB, Truong Y, Bai P, McKeown MJ, Mailman RB, Belger A, Huang X. Task specific influences of Parkinson’s disease on the striato-thalamo-cortical and cerebello-thalamo-cortical motor circuitries. Neuroscience. 2007;147:224–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotze M, Scheler G, Tan HR, Braun C, Birbaumer N. The musician’s brain: functional imaging of amateurs and professionals during performance and imagery. Neuroimage. 2003;20:1817–29. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzoni D. The cerebellum and sensorimotor coupling: looking at the problem from the perspective of vestibular reflexes. Cerebellum. 2007;6:24–37. doi: 10.1080/14734220601132135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitsch HJ. Thalamic mediodorsal nucleus and memory: a critical evaluation of studies in animals and man. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1982;6:351–80. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(82)90046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matelli M, Luppino G. Thalamic input to mesial and superior area 6 in the macaque monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1996;372:59–87. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960812)372:1<59::AID-CNE6>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PJ, Hall WC. The cerebellotectal pathway in the grey squirrel. Exp Brain Res. 1986;65:200–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00243843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey DP, Adamo DS, Anderson BJ. Exercise increases metabolic capacity in the motor cortex and striatum, but not in the hippocampus. Brain Res. 2001;891:168–175. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03200-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meftah EM, Rispal-Padel L. Synaptic plasticity in the thalamo-cortical pathway as one of the neurobiological correlates of forelimb flexion conditioning: electrophysiological investigation in the cat. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:2631–47. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.6.2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintun MA, Lundstrom BN, Snyder AZ, Vlassenko AG, Shulman GL, Raichle ME. Blood flow and oxygen delivery to human brain during functional activity: theoretical modeling and experimental data. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6859–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111164398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran A, Avendano C, Reinoso-Suarez F. Thalamic afferents to the motor cortex in the cat. A horseradish peroxidase study. Neurosci Lett. 1982;33:229–33. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(82)90376-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgen K, Kadom N, Sawaki L, Tessitore A, Ohayon J, Frank J, McFarland H, Martin R, Cohen LG. Kinematic specificity of cortical reorganization associated with motor training. Neuroimage. 2004;21:1182–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir GD, Whishaw IQ. Red nucleus lesions impair overground locomotion in rats: a kinetic analysis. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:1113–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munte TF, Altenmuller E, Jancke L. The musician’s brain as a model of neuroplasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:473–8. doi: 10.1038/nrn843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami F, Katsumaru H, Saito K, Tsukahara N. A quantitative study of synaptic reorganization in red nucleus neurons after lesion of the nucleus interpositus of the cat: an electron microscopic study involving intracellular injection of horseradish peroxidase. Brain Res. 1982;242:41–53. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90494-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na J, Kakei S, Shinoda Y. Cerebellar input to corticothalamic neurons in layers V and VI in the motor cortex. Neurosci Res. 1997;28:77–91. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(97)00031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Mizuno N, Konishi A, Sato M. Synaptic reorganization of the red nucleus after chronic deafferentation from cerebellorubral fibers: an electron microscope study in the cat. Brain Res. 1974;82:298–301. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90609-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council of the National Academies. Guidelines for the Care and Use of Mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research. The National Academies Press; Washington DC: 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neafsey EJ, Bold EL, Haas G, Hurley-Gius KM, Quirk G, Sievert CF, Terreberry RR. The organization of the rat motor cortex: a microstimulation mapping study. Brain Res. 1986;396:77–96. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(86)80191-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen PT, Holschneider DP, Maarek JM, Yang J, Mandelkern MA. Statistical parametric mapping applied to an autoradiographic study of cerebral activation during treadmill walking in rats. Neuroimage. 2004;23:252–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemi-Junkola UJ, Westby GW. Spatial variation in the effects of inactivation of substantia nigra on neuronal activity in rat superior colliculus. Neurosci Lett. 1998;241:175–9. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00956-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemi-Junkola UJ, Westby GW. Cerebellar output exerts spatially organized influence on neural responses in the rat superior colliculus. Neuroscience. 2000;97:565–73. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan RM, Ohle R, Kelly AM. The effects of forced exercise on hippocampal plasticity in the rat: A comparison of LTP, spatial- and non-spatial learning. Behav Brain Res. 2007;176:362–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeso JA, Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Rodriguez M, Macias R, Alvarez L, Guridi J, Vitek J, DeLong MR. Pathophysiologic basis of surgery for Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2000;55:S7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuka K. Inhibitory action of Purkinje cells in the posterior vermis on fastigio-prepositus circuit of the cat. Brain Res. 1988;455:153–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson AK, Eadie BD, Ernst C, Christie BR. Environmental enrichment and voluntary exercise massively increase neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus via dissociable pathways. Hippocampus. 2006;16:250–60. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patlak CS, Blasberg RG, Fenstermacher JD. An evaluation of errors in the determination of blood flow by the indicator fractionation and tissue equilibration (Kety) methods. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1984;4:47–60. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1984.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotactic Coordinates. Elsevier Academic Press; New York, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira AC, Huddleston DE, Brickman AM, Sosunov AA, Hen R, McKhann GM, Sloan R, Gage FH, Brown TR, Small SA. An in vivo correlate of exercise-induced neurogenesis in the adult dentate gyrus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5638–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611721104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez MA, Lungholt BK, Nyborg K, Nielsen JB. Motor skill training induces changes in the excitability of the leg cortical area in healthy humans. Exp Brain Res. 2004;159:197–205. doi: 10.1007/s00221-004-1947-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rispal-Padel L, Meftah EM. Changes in motor responses induced by cerebellar stimulation during classical forelimb flexion conditioning in cat. J Neurophysiol. 1992;68:908–26. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.3.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouiller EM, Moret V, Liang F. Comparison of the connectional properties of the two forelimb areas of the rat sensorimotor cortex: support for the presence of a premotor or supplementary motor cortical area. Somatosens Mot Res. 1993;10:269–89. doi: 10.3109/08990229309028837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai ST, Grofova I, Bruce K. Nigrothalamic projections and nigrothalamocortical pathway to the medial agranular cortex in the rat: single- and double-labeling light and electron microscopic studies. J Comp Neurol. 1998;391:506–25. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980222)391:4<506::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurada O, Kennedy C, Jehle J, Brown JD, Carbin GL, Sokoloff L. Measurement of local cerebral blood flow with iodo [14C] antipyrine. Am J Physiol. 1978;234:H59–H66. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1978.234.1.H59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieber MH. Constraints on somatotopic organization in the primary motor cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:2125–43. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.5.2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sefton AJ, Dreher B, Harvey A. Visual System. In: Paxinos G, editor. The Rat Nervous System. Elsevier Academic Press; San Diego: 2004. pp. 1083–1165. [Google Scholar]

- Shinoda Y, Futami T, Kano M. Synaptic organization of the cerebello-thalamo-cerebral pathway in the cat. II. Input-output organization of single thalamocortical neurons in the ventrolateral thalamus. Neurosci Res. 1985;2:157–80. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(85)90010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumway-Cook A, Woollacott MH. Motor control: Theory and practical applications. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore, MD: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M. Two channels in the cerebellothalamocortical system. J Comp Neurol. 1995;354:57–70. doi: 10.1002/cne.903540106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniwaki T, Okayama A, Yoshiura T, Nakamura Y, Goto Y, Kira J, Tobimatsu S. Reappraisal of the motor role of basal ganglia: a functional magnetic resonance image study. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3432–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03432.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniwaki T, Okayama A, Yoshiura T, Togao O, Nakamura Y, Yamasaki T, Ogata K, Shigeto H, Ohyagi Y, Kira J, Tobimatsu S. Functional network of the basal ganglia and cerebellar motor loops in vivo: different activation patterns between self-initiated and externally triggered movements. Neuroimage. 2006;31:745–53. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaut MH, McIntosh GC, Rice RR, Miller RA, Rathbun J, Brault JM. Rhythmic auditory stimulation in gait training for Parkinson’s disease patients. Mov Disord. 1996;11:193–200. doi: 10.1002/mds.870110213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thevenaz P, Ruttimann UE, Unser M. A pyramid approach to subpixel registration based on intensity. IEEE Trans Image Process. 1998;7:27–41. doi: 10.1109/83.650848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy JI, Faro SS, Mohammed F, Pinus A, Christensen H, Burkland D. A comparison of ‘Early’ and ‘Late’ stage brain activation during brief practice of a simple motor task. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2001;10:303–16. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(00)00045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukahara N, Hultborn H, Murakami F, Fujito Y. Electrophysiological study of formation of new synapses and collateral sprouting in red nucleus neurons after partial denervation. J Neurophysiol. 1975;38:1359–72. doi: 10.1152/jn.1975.38.6.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uda M, Ishido M, Kami K, Masuhara M. Effects of chronic treadmill running on neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus of adult rat. Brain Res. 2006;1104:64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.05.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Werf YD, Witter MP, Groenewegen HJ. The intralaminar and midline nuclei of the thalamus. Anatomical and functional evidence for participation in processes of arousal and awareness. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2002;39:107–40. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Eimeren T, Siebner HR. An update on functional neuroimaging of parkinsonism and dystonia. Curr Opin Neurol. 2006;19:412–9. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000236623.68625.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Uitert RL, Levy DE. Regional brain blood flow in the conscious gerbil. Stroke. 1978;9:67–72. doi: 10.1161/01.str.9.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner JJ. Atlas of Neuroanatomy with Systems Organization and Case Correlations. Butterworth Heinemann; Boston: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Westby GW, Collinson C, Dean P. Excitatory drive from deep cerebellar neurons to the superior colliculus in the rat: an electrophysiological mapping study. Eur J Neurosci. 1993;5:1378–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westby GW, Collinson C, Redgrave P, Dean P. Opposing excitatory and inhibitory influences from the cerebellum and basal ganglia converge on the superior colliculus: an electrophysiological investigation in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 1994;6:1335–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whishaw IQ, Gorny B. Does the red nucleus provide the tonic support against which fractionated movements occur? A study on forepaw movements used in skilled reaching by the rat. Behav Brain Res. 1996;74:79–90. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(95)00161-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whishaw IQ, Gorny B, Sarna J. Paw and limb use in skilled and spontaneous reaching after pyramidal tract, red nucleus and combined lesions in the rat: behavioral and anatomical dissociations. Behav Brain Res. 1998;93:167–83. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)00152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Frazier DT. Role of the cerebellar deep nuclei in respiratory modulation. Cerebellum. 2002;1:35–40. doi: 10.1080/147342202753203078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]