Abstract

Background

A number of western studies have suggested that the 6-month duration requirement of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) does not represent a critical threshold in terms of onset, course, or risk factors of the disorder. No study has examined the consequences of modifying the duration requirement across a wide range of correlates in both developed and developing countries.

Methods

Population surveys were carried out in 7 developing and 10 developed countries using the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (total sample size = 85,052). Prevalence of GAD was estimated using different minimum duration criteria. Age of onset, symptom persistence, subsequent mental disorders, impairment, and recovery were compared across GAD subgroups defined by different duration criteria.

Results

Lifetime prevalence estimates for GAD lasting 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months were 7.5%, 5.24%, 4.11%, and 2.95% for developed countries and 2.65%, 1.78%, 1.47%, and 1.17% for developing countries, respectively. There was little difference between GAD of 6 months duration and GAD of shorter durations (1–2 months, 3–5 months) in symptom severity, age of onset, persistence, impairment, or comorbidity. Those with GAD lasting 12 months or more were the most severe, chronic, and impaired of the four duration subgroups.

Conclusion

In both developed and developing countries, the clinical profile of GAD is similar regardless of duration. The DSM-IV 6-month duration criterion is not an optimal marker of severity, impairment, or need for early treatment. Future iterations of the DSM and ICD should consider shortening the duration requirement of GAD.

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is increasingly recognized as a prevalent anxiety disorder with characteristic symptoms, significant morbidity, and specific risk factors (World Health Organization, 1993; American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Nevertheless, repeated revisions of the GAD diagnostic criteria in recent decades reflect continued uncertainty over the definition and diagnosis of the disorder. Apart from debates over the centrality of pathological worry, the number and type of associated anxiety symptoms, and the level of impairment required for diagnosis (Rickels & Rynn, 2001; Slade & Andrews, 2001), a primary focus for nosological revision has been the duration criterion of GAD. Although early classifications of pathological anxiety did not specify a minimum duration for diagnosis (Feighner et al., 1972; World Health Organization, 1978), efforts to improve diagnostic reliability and differentiation from normal anxiety reactions led to the requirement of a minimum GAD duration of one month in DSM-III (American Psychiatric Association, 1980) and an increase to six months in DSM-III-R (American Psychiatric Association, 1987), ICD-10 (World Health Organization, 1993), and DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

Among the anxiety disorders, the requirement of such a long and specific duration is almost unique to GAD, and questions about its necessity remain. This suggests that, despite improved reliability of diagnosis (Brown et al., 2001), questions about the validity of GAD are by no means resolved. Following criticisms of the questionable clinical utility of the current duration criterion in defining GAD (Rickels & Rynn, 2001), a number of empirical studies in western countries have recently addressed this question. Taken together, they suggest that GAD lasting one month is comparable to GAD lasting 6 or more months in sociodemographic characteristics, clinical course, pattern of comorbidity, functional impairment, antecedent childhood adversity, and heritability (Kendler et al., 1992; Kendler et al., 1994; Bienvenu et al., 1998; Maier et al., 2000; Carter et al., 2001; Hettema et al., 2001; Kessler et al., 2005; Angst et al., 2006)

Such findings have led a number of experts to call for shortening the duration criterion of GAD in DSM-V (Bienvenu et al., 1998; Rickels & Rynn, 2001; Kessler et al., 2005; Angst et al., 2006; Ruscio et al., 2007). Before this change can be considered seriously, however, additional data are needed on at least two fronts. First, the GAD duration criterion originally was increased from one to six months because of concerns that the shorter duration did not adequately distinguish GAD from normative, transient reactions to stress (Breslau & Davis, 1985). Similar concerns about reduced diagnostic validity and pathologizing of normal stress reactions are likely to be raised for DSM-V. Addressing these concerns will require systematic comparisons of GAD of varying durations on a wide range of relevant validators. Second, although the DSM aspires to be a global diagnostic system, empirical studies of the GAD criteria outside of western countries have been scarce. Recently published data from developing countries such as Nigeria and China have begun to address this gap, but have so far been confined to reporting basic prevalence estimates and sociodemographic correlates of GAD based only on DSM-IV diagnostic criteria (Gureje et al., 2006; Shen et al., 2006) rather than evaluating the impact of modifying these criteria. It is therefore desirable to evaluate how varying the duration of GAD may affect its validity in a range of developed and developing countries, ideally using unselected, general population samples to minimize the impact of sampling biases on results.

The present study examined the validity of GAD of different durations in a large data set including representative samples from 10 developed and 7 developing countries. After estimating the prevalence of GAD defined by different minimum duration criteria (1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months), we compared the characteristics of four mutually exclusive groups that met the symptom criteria for DSM-IV GAD but differed in the duration of their longest GAD episode.

Method

Samples

As part of the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative (Demyttenaere et al., 2004), 17 countries in the Americas (Colombia, Mexico, United States), Europe (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Spain), Ukraine, the Middle East (Israel, Lebanon), Africa (Nigeria, South Africa) and Asia-Pacific (Japan, New Zealand, People’s Republic of China - Beijing, Shanghai) were surveyed. Developing countries were those with a Human Development Index lower than 0.90, namely China (Beijing, Shanghai), Columbia, Lebanon, Mexico, Nigeria, South Africa, and Ukraine. Developed countries were those with a Human Development Index of 0.90 or greater, namely, Belgium, France, Germany, Israel, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Spain, and the United States (United Nations Development Programme, 2004).

All surveys were based on multi-stage, clustered area probability household samples. Interviews were carried out face-to-face by trained lay interviewers. The combined total sample size was 85,052 (Table 1). Most of the respondents were age 18 or older, with the exception of respondents from New Zealand (age 16 or older), Japan (age 20 or older), and Israel (age 21 or older). Survey response rates varied, with a weighted average response rate across surveys of 71%. Other than in the Israel survey, where all respondents were administered the full interview, internal sub-sampling was used to reduce respondent burden by dividing the interview into two parts. Part 1 assessed core mental disorders, including GAD, and was administered to all respondents. Part 2 included additional disorders and correlates relevant to a wide range of survey aims. It was administered to all Part 1 respondents who met criteria for any mental disorder as well as a probability sample of other respondents. Part 2 respondents were weighted by the inverse of their probability of selection for Part 2 of the interview to adjust for differential sampling. Additional weights were used to adjust for differential probabilities of selection within households and to match the samples to population sociodemographic distributions.

Table 1.

WMH Sample Characteristics

| Country | Survey1 | Sample Characteristics2 | Field Dates | Age Range | Sample Size | Response Rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part I | Part II | Part II and Age ≤ 444 | ||||||

| I. Developed | ||||||||

| Belgium | ESEMeD | Stratified multistage clustered probability sample of individuals residing in households from the national register of Belgium residents. NR | 2001–2 | 18+ | 2419 | 1043 | 486 | 50.6 |

| France | ESEMeD | Stratified multistage clustered sample of working telephone numbers merged with a reverse directory (for listed numbers). Initial recruitment was by telephone, with supplemental in-person recruitment in households with listed numbers. NR | 2001–2 | 18+ | 2894 | 1436 | 727 | 45.9 |

| Germany | ESEMeD | Stratified multistage clustered probability sample of individuals from community resident registries. NR | 2002–3 | 18+ | 3555 | 1323 | 621 | 57.8 |

| Israel | NHS | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of individuals from a national resident register. NR | 2002–4 | 21+ | 4859 | -- | -- | 72.6 |

| Italy | ESEMeD | Stratified multistage clustered probability sample of individuals from municipality resident registries. NR | 2001–2 | 18+ | 4712 | 1779 | 853 | 71.3 |

| Japan | WMHJ2002–2006 | Un-clustered two-stage probability sample of individuals residing in households in nine metropolitan areas (Fukiage, Higashi-ichiki, Ichiki, Kushikino, Nagasaki, Okayama, Sano, Tamano, Tendo, and Tochigi) | 2002–6 | 20+ | 3417 | 1305 | 425 | 59.2 |

| Netherlands | ESEMeD | Stratified multistage clustered probability sample of individuals residing in households that are listed in municipal postal registries. NR | 2002–3 | 18+ | 2372 | 1094 | 516 | 56.4 |

| New Zealand | NZMHS | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents. NR | 2004–5 | 16+ | 12992 | 7435 | 4242 | 73.3 |

| Spain | ESEMeD | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents. NR | 2001–2 | 18+ | 5473 | 2121 | 960 | 78.6 |

| United States | NCS-R | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents. NR | 2002–3 | 18+ | 9282 | 5692 | 3197 | 70.9 |

| II. Developing | ||||||||

| Colombia | NSMH | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents in all urban areas of the country (approximately 73% of the total national population) | 2003 | 18–65 | 4426 | 2381 | 1731 | 87.7 |

| Lebanon | LEBANON | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents. NR | 2002–3 | 18+ | 2857 | 1031 | 595 | 70.0 |

| Mexico | M-NCS | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents in all urban areas of the country (approximately 75% of the total national population). | 2001–2 | 18–65 | 5782 | 2362 | 1736 | 76.6 |

| Nigeria | NSMHW | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of households in 21 of the36 states in the country, representing 57% of the national population. The surveys were conducted in Yoruba, Igbo, Hausa and Efik languages. | 2002–3 | 18+ | 6752 | 2143 | 1203 | 79.3 |

| PRC | B-WMH S-WMH | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents in the Beijing and Shanghai metropolitan areas. | 2002–3 | 18+ | 5201 | 1628 | 570 | 74.7 |

| South Africa | SASH | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents. NR | 2003–4 | 18+ | 4351 | -- | -- | 87.1 |

| Ukraine | CMDPSD | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents. NR | 2002 | 18+ | 4725 | 1720 | 541 | 78.3 |

ESEMeD (The European Study Of The Epidemiology Of Mental Disorders); NHS (Israel National Health Survey); WMHJ2002–2006 (World Mental Health Japan Survey); NZMHS (New Zealand Mental Health Survey); NCS-R (The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication); NSMH (The Colombian National Study of Mental Health); LEBANON (Lebanese Evaluation of the Burden of Ailments and Needs of the Nation); M-NCS (The Mexico National Comorbidity Survey); NSMHW (The Nigerian Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing); B-WMH (The Beijing World Mental Health Survey); S-WMH (The Shanghai World Mental Health Survey); SASH (South Africa Stress and Health Study); CMDPSD (Comorbid Mental Disorders during Periods of Social Disruption);

Most WMH surveys are based on stratified multistage clustered area probability household samples in which samples of areas equivalent to counties or municipalities in the US were selected in the first stage followed by one or more subsequent stages of geographic sampling (e.g., towns within counties, blocks within towns, households within blocks) to arrive at a sample of households, in each of which a listing of household members was created and one or two people were selected from this listing to be interviewed. No substitution was allowed when the originally sampled household resident could not be interviewed. These household samples were selected from Census area data in all countries other than France (where telephone directories were used to select households) and the Netherlands (where postal registries were used to select households). Several WMH surveys (Belgium, Germany, and Italy) used municipal resident registries to select respondents without listing households. The Japanese sample is the only totally un-clustered sample, with households randomly selected in each of the four sample areas and one random respondent selected in each sample household. 11 of the 17 surveys are based on nationally representative (NR) household samples, while two others are based on nationally representative household samples in urbanized areas (Colombia, Mexico).

The response rate is calculated as the ratio of the number of households in which an interview was completed to the number of households originally sampled, excluding from the denominator households known not to be eligible either because of being vacant at the time of initial contact or because the residents were unable to speak the designated languages of the survey.

Israel and South Africa did not have an age restricted Part II sample. All other countries, with the exception of Nigeria, People’s Republic of China, and Ukraine (which were age restricted to ≤ 39) were age restricted to ≤ 44.

Training and Field Procedures

The central WMH staff trained bilingual supervisors in each country. Consistent interviewer training documents and standardized translation protocols were used across surveys. The institutional review board of the organization that coordinated the survey in each country approved and monitored compliance with procedures for obtaining informed consent and protecting human subjects.

Diagnostic measures

Mental disorders were assessed using Version 3.0 of the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (Kessler & Ustun, 2004), a fully structured lay-administered interview that generates diagnoses according to both ICD-10 (World Health Organization, 1993) and DSM-IV criteria. DSM-IV anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders were included in analyses, as were several disorders that share a common feature of difficulties with impulse control (intermittent explosive disorder, oppositional-deviant disorder, conduct disorder, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder). Diagnostic hierarchy rules and organic exclusion rules were used in making diagnoses. As detailed elsewhere (Kessler et al., 2005; Haro et al., 2006), blind clinical re-interviews using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; (First et al., 2002)) with a probability sub-sample of respondents from Spain, Italy, France and United States found generally good concordance between DSM-IV diagnoses based on the CIDI and the SCID for anxiety (including GAD), mood, and substance use disorders (CIDI diagnoses of impulse-control disorders were not validated).

Respondents were assessed for the symptoms of GAD, then asked about the number and length of episodes of worry or anxiety experienced in their lifetime and in the last 12 months. “Episode” was explicitly defined as “a time lasting one month or longer when most days you were (worried or anxious/nervous or anxious/anxious or worried) and also had some of the other problems we just reviewed. The episode ends when you no longer have these feelings for a full month.” Respondents reporting multiple episodes were grouped for analysis based on their longest lifetime episode.

Other measures

Impairment was assessed by the Sheehan Disability Scales (Leon et al., 1997), which asked respondents to focus on the one month in the past year when their GAD was most severe and to rate how much GAD interfered with their home management, work, social life, and personal relationships on scales of none (0), mild (1–3), moderate (4–6), severe (7–9), and very severe (10). In addition, role impairment in the past year was assessed by two variables: days out of role, defined as the number of days out of 365 during which the respondent was “totally unable” to work or carry out daily activities because of GAD; and role impairment in episode, defined as the percentage of all days in the GAD episode that were spent out of role.

Analysis methods

We estimated the 1-month, 12-month, and lifetime prevalence of GAD using the minimum duration requirements of 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. Subsequently, mutually exclusive subgroups with durations of 1–2, 3–5, 6–11, and 12+ months were compared on age of onset, clinical course, persistence, role impairment, and time to recovery using chi-square tests or analysis of variance. Associations with other mental disorders were estimated using a discrete-time survival model with person-year as the unit of analysis, in which variably defined GAD predicted the subsequent first onset of a class of disorders (another anxiety disorders, mood disorders, substance use disorders and impulse control disorders). We used the actuarial method (Halli & Vaninadha Rao, 1992) to calculate age-of-onset (AOO) and time to recovery curves for these duration subgroups. Using the Taylor series linearization method (Wolter, 1985) implemented in the SUDAAN software package (Research Triangle Park, 2002), we adjusted for weighting and clustering when calculating standard errors and performing significance tests. Statistical significance was evaluated at the 0.05 level.

Results

Prevalence

The estimated prevalence of GAD increases as the duration criterion is shortened. (Table 2) For developed countries, lifetime prevalence estimates range from a low of 3.0% when the minimum duration is 12 months to a high of 7.5% when the minimum duration is 1 month. The corresponding estimates for developing countries are lower, but in the same direction, ranging from 1.2% for 12-month to 2.4% for 1-month minimum duration. The same pattern is evident for 12-month prevalence estimates for developed (1.3%–3.2%) and developing (0.7%–1.4%) countries as well as for one-month estimates in both country groups (developed: 0.6%–1.1%; developing: 0.3%–0.6%).

Table 2.

Lifetime, one year, and one month prevalence estimates of DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder when the duration threshold was set at minimal requirement as 1, 3, 6 and 12 months, in developing and developed countries

| Prevalence of GAD when minimal duration threshold is set at…. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 month | 3 months | 6 months(DSM-IV criterion) | 12 months | |

| % (se) | % (se) | % (se) | % (se) | |

| Developed countries | ||||

| 1-month | 1.1 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.0) | 0.7 (0.0) | 0.6 (0.0) |

| 12-month | 3.2 (0.1) | 2.2 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) | 1.3 (0.1) |

| Lifetime | 7.5 (0.2) | 5.2 (0.2) | 4.1 (0.1) | 3.0 (0.1) |

| Developing countries | ||||

| 1-month | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.0) |

| 12-month | 1.4 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.7 (0.1) |

| Lifetime | 2.7 (0.1) | 1.8 (0.1) | 1.5 (0.1) | 1.2 (0.1) |

Onset and Course

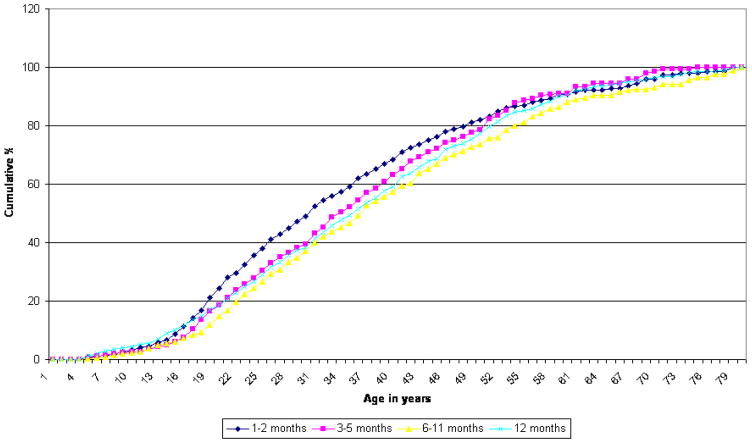

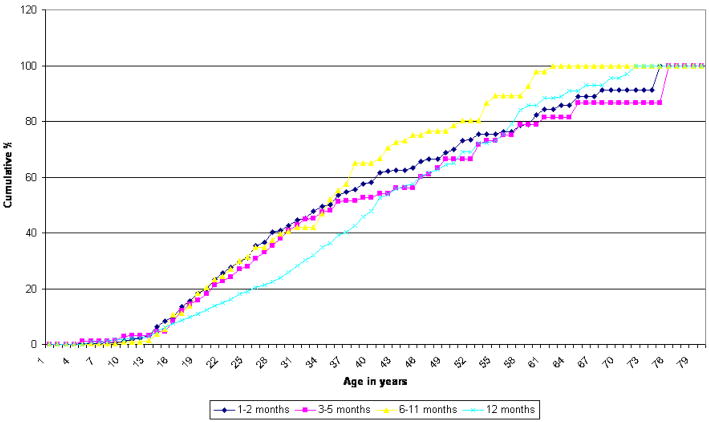

Cumulative age-of-onset (AOO) distributions are similar in shape for the four mutually exclusive duration subgroups, although the distributions differ significantly (χ23–developed = 26.0, χ23–developing = 18.0, p <.001). (Figure 1) In both groups of countries, all four subgroups have median AOO in the thirties and rarely have onsets after age 60. Mean AOO is also quite similar among the subgroups, falling in the age range of 25 to 30. (Table 3) In developed countries, the 1–2 month subgroup has a somewhat later onset than the other three subgroups. In developing countries, there is no significant difference in mean AOO by subgroup.

Figure 1.

Age of onset - developed countries Chi-Square = 26.0 p-value < 0.0001

Age of onset - developed countries Chi-Square = 18.0 p-value = 0.0004

Table 3.

Course of lifetime GAD by specific episode duration (1–2 months, 2–5 months, 6–11 months, +12 months), in developed and developing countries

| Duration of generalized anxiety | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Developed countries | 1–2 months (n=1128) | 3–5 months (n=557) | 6–11 months (n=604) | ≥ 12 months (n=1603) | F test (df=3) | p |

| Mean age of onset (se) | 26.7 (0.5) | 28.9 (0.7) | 30.1 (0.7) | 28.9 (0.4) | 25.8* | <0.01 |

| Mean years with GAD (se) | 5.7 (0.3) | 5.6 (0.5) | 5.3 (0.4) | 8.7 (0.3) | 55.7* | <0.01 |

| Proportion of years with GAD since onseta (se) | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.7 (0) | 2.5 | 0.48 |

| Mean longest duration of GAD in months(se) | 1.4 (0) | 3.4 (0) | 6.8 (0.1) | 80.6 (3.9) | 457.1* | <0.01 |

| Annual persistence of GADb | 41.8 (1.9) | 44.2 (2.4) | 41.4 (2.3) | 42.7 (1.5) | 5.5 | 0.14 |

| Mean months in previous year (se) with anxiety among those with GAD in previous year (np) | 3.0 (0.2) (np=474) |

3.8 (0.2) (np=248) |

5.2 (0.3) (np=251) |

7.2 (0.2) (np=363) |

272.1* | <0.01 |

| Developing countries | (n=301) | (n=109) | (n=108) | (n=432) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Mean age of onset (se) | 25.2 (0.8) | 25.8 (1.3) | 26.6 (0.7) | 29.8 (0.8) | 0.5 | 0.92 |

| Mean year with GAD (se) | 3.7 (0.3) | 3.5 (0.5) | 4.4 (0.6) | 6.5 (0.5) | 14.9* | <0.01 |

| Proportion of years with GAD since onset | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.5 (0) | 1.2 | 0.74 |

| Mean longest duration (month) of GAD in months (se) | 1.3 (0) | 3.4 (0.1) | 6.8 (0.1) | 92 (7.5) | 148.9* | <0.01 |

| Annual persistence of GADb %(se) | 53.1 (3.4) | 42.6 (5.5) | 54.8 (5.4) | 56.4 (2.8) | 5.4 | 0.14 |

| Mean months in previous year (se) with anxiety among those with GAD in previous year (np) | 3.2 (0.3) (np=157) |

3.5 (0.4) (np=52) |

5 (0.5) (np=54) |

6.4 (0.3) (np=251) |

37.1* | <0.01 |

np: number of respondents with GAD in previous 12-months

Number of years in episode divided by the total years between onset age of generalized anxiety and current age

Percent of lifetime cases that had generalized anxiety in the past 12 months (ratio of 12-month to lifetime prevalence x 100%)

significant at p<0.05

On several indices of persistence, GAD lasting 12 months or more is more chronic than the other subgroups. In both developed and developing countries, this subgroup reported more years with GAD (8.7, 6.5) than the other subgroups, which were more similar to one another (5.3–5.7, 3.5–4.4). Increasing duration of GAD is associated not only with an increase in the longest lifetime GAD episode, but also with more months in episode during the past year. By contrast, the four subgroups do not differ in annual persistence (the proportion of lifetime cases that had GAD in the past 12 months) of GAD. The subgroups also do not differ in lifetime persistence of GAD, as they all experience generalized anxiety in roughly half of the years since the onset of their respectively defined GAD.

Severity and impairment

Lifetime GAD severity (mild, moderate, severe) was calculated by submitting 11 nested dichotomous variables representing uncontrollability, distress, and impairment associated with worry and generalized anxiety into an item response theory (IRT) analysis, and trichotomizing the resulting dimension. There was a significant trend in developed (χ26 = 110.5, p < 0.01) as well as developing (χ26 = 20.7, p < 0.01) countries of fewer mild cases and more severe cases with increasing GAD duration (results not shown, but available on request). The highest proportion of severe cases was in the ≥ 12 month subgroup in both developed (41.7%) and developing (36.7%) countries. Nevertheless, severity was substantial even in the 1–2 month subgroup, where the majority of cases (55.9% in developed and 60.6% in developing countries) were classified as having moderate or severe GAD.

Impairment is also related to duration of GAD (Table 4). In developed countries, the ≥12 month subgroup is more severely impaired on all SDS domains (4.1–4.7) than the 1–2 month subgroup (3.4–3.8), with the 3–5 and 6–11 month subgroups being intermediate in impairment. Although they differ significantly, the subgroup means for each domain and for the highest-rated domain are within one point of each other on the 0–10 response scale. There is a larger difference between the ≥ 12 month subgroup (48.2) and the other subgroups (15.8–24.7) on days out of role due to GAD. In developing countries, the overall pattern is also one of increasing impairment with increasing duration, although the increase is less monotonic than in developed countries and is statistically significant only for social impairment and for days out of role, where the largest difference is between the 1–2 month subgroup (10.8) and the other subgroups (24.4–30.8).

Table 4.

Past-year impairment in Sheehan Disability Scale domains and days out of role among respondents with lifetime GAD defined by specific episode duration (1–2 months, 2–5 months, 6–11 months, +12 months), in developed countries

| Duration of generalized anxiety | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 month | 3–5 month | 6–11 month | 12 month or more | F test, df=3 | p | |

| Developed (np) | (np=474) | (np=248) | (np=251) | (np=363) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Homea | 3.4 (0.2) | 3.6 (0.2) | 3.7 (0.2) | 4.1 (0.2) | 12.0* | 0.01 |

| Worka | 3.7 (0.2) | 4.0 (0.3) | 3.7 (0.2) | 4.3 (0.2) | 10.7* | 0.01 |

| Relationshipsa | 3.8 (0.2) | 4.3 (0.3) | 4.6 (0.2) | 4.7 (0.2) | 18.8* | <0.01 |

| Social lifea | 3.7 (0.2) | 4.2 (0.3) | 4.3 (0.2) | 4.4 (0.2) | 19.3* | <0.01 |

| Highest-rated domaina | 5.2 (0.2) | 6.1 (0.2) | 5.8 (0.2) | 6.2 (0.2) | 24.5* | <0.01 |

| Days out of roleb | 15.8 (2.7) | 24.7 (4.7) | 21.3 (4) | 48.2 (4.6) | 39.9* | <0.01 |

| Role impairment in episodec (se) | 0.1 (0.0) | 0.2 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.0) | 0.2 (0.0) | 13.0* | 0.01 |

| Developing (np) | (np=157) | (np=52) | (np=54 | (np=251) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Mean SDS, home (se) | 2.5 (0.3) | 3.4 (0.5) | 3.4 (0.5) | 3.9 (0.3) | 7.7 | 0.05 |

| Mean SDS, work (se) | 2.7 (0.3) | 3.1 (0.6) | 4.0 (0.6) | 3.1 (0.3) | 5.1 | 0.16 |

| Mean SDS, relationships (se) | 3.0 (0.4) | 3.4 (0.5) | 3.8 (0.7) | 3.0 (0.3) | 6.4 | 0.09 |

| Mean SDS, social (se) | 3.2 (0.4) | 3.4 (0.6) | 4.6 (0.6) | 3.4 (0.3) | 8.8* | 0.03 |

| Mean SDS, highest-rated domain (se) | 4.3 (0.4) | 4.9 (0.6) | 5.5 (0.5) | 4.9 (0.3) | 9.0* | 0.03 |

| Day out of role a, % (se) | 10.8 (2.8) | 24.4 (11) | 30.8 (10) | 29.3 (5.2) | 10.3* | 0.02 |

| Role impairment during anxiety b (se) | 0.1 (0.0) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.0) | 3.0 | 0.39 |

Note. Estimated among 12-month cases (np)

Mean (standard error) on the Sheehan Disability Scales (SDS), which were rated on a scale of 0 (no impairment) 1–3 (mild), 4–6 (moderate), 7–9 (severe), 10 (very severe impairment).

Mean (standard error) number of days in the past 12 months during which the respondent was “totally unable” to work or carry out daily activities because of GAD

In the past 12 months, proportion of days with GAD that respondents were out of role for the whole day

significant at p<0.05

Comorbidity and suicidality

All four GAD subgroups are significantly associated with the subsequent first onset of other mental disorders (Table 5). Where significant differences exist, the highest odds of subsequent disorders are found for the ≥ 12 month subgroup. Differences between the other subgroups are generally non-monotonic across disorder classes and inconsistent across developed and developing countries. In predicting the onset of any comorbid mental disorder, only the ≥ 12 month subgroup differs significantly from the 1–2 months subgroups in developed countries by exhibiting more elevated associations with other anxiety disorders and any mood disorders, whereas none of the subgroups differ significantly in developing countries. In follow-up analyses examining past-year comorbidity of GAD with individual mental disorders, the four subgroups had elevated odds-ratios with every anxiety and mood disorder assessed in the surveys, as well as with intermittent explosive disorder and alcohol abuse (results available on request).

Table 5.

Association between generalized anxiety disorder defined with specific duration and risk of subsequent first onset of other disorders, presented in odds ratios ORs (95% CI), in developed countries

| Duration of generalized anxiety | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 months | 3–5 months | 6–11 months | ≥12 months | Wald χ2 (df=3) | p | |

| Developed | ||||||

| Any other anxiety disorders a | 2.4 (1.9–3.0) | 2.5 (1.9–3.4) | 2.8 (2.0–4.0) | 3.7 (3.1–3.4) | 13.4* | <0.01 |

| Any mood disorders b | 2.1 (1.7–2.7) | 2.8 (2.0–3.8) | 2.6 (1.9–3.6) | 3.3 (2.8–4.0) | 10.3* | 0.02 |

| Any substance use disorders a | 2.3 (1.7–3.2) | 1.7 (1.0–2.7) | 1.5 (0.9–2.6) | 2.7 (2.0–3.5) | 5.6 | 0.13 |

| Any impulse-control disorders c | 4.8 (2.5–9.1) | 3.7 (0.9–15.7) | 1.4 (0.3–7.4) | 2.1 (0.9–5.3) | 3.7 | 0.29 |

| Any disorders a | 2.1 (1.5–2.9) | 1.8 (1.0–3.2) | 1.6 (0.9–2.8) | 3.4 (2.6–4.5) | 10.1* | 0.02 |

| Developing | ||||||

| Any other anxiety disorders a | 3.6 (2.0–6.5) | 4.5 (2.1–9.8) | 2.9 (1.5–5.4) | 6.4 (4.5–9.2) | 6.6 | 0.09 |

| Any mood disorders b | 3.7 (2.4–5.6) | 1.3 (0.6–2.8) | 2.5 (1.2–5.3) | 4.2 (3.0–6.0) | 9.1* | 0.02 |

| Any substance use disorders a | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | 2.2 (0.7–6.4) | 1.9 (0.8–4.4) | 3.4 (1.9–6.0) | 2.2 | 0.54 |

| Any impulse-control disorders c | 1.1 (0.2–7.3) | 2.0 (0.5–9.0) | 0.8 (0.1–6.3) | 11.3 (4.0–31.9) | 8.6* | 0.04 |

| Any disorders a | 2.0 (1.0–3.7) | 3.9 (1.0–15.5) | 4.1 (2.2–7.9) | 4.7 (3.0–7.3) | 4.9 | 0.18 |

Note. Based on bivariate analysis using a discrete-time survival model with person-year as the unit of analysis, controlling for person-year, person-year squared, age at interview, sex. No distinctions are made between respondents whose target disorder was active vs. remitted at the time that the secondary disorder began. Disorders are diagnosed without diagnostic hierarchies.

weighed on Part II sample (developed=27545, developing=15579)

weighed on Part I sample (developed=50791, developing=34057)

weighed on Part II sample in age 44 years or younger (developed=14262, developing=10121)

significant at p<0.05

In contrast to GAD of shorter durations, the ≥ 12 month subgroup had a significantly elevated risk of suicidality (results not shown, but available on request). The odds ratios (OR) in developed and developing countries were significant for subsequent suicidal ideation (2.0, 2.0), plan (1.7, 2.0), and attempt (1.6, 2.1). The ORs for the other GAD subgroups were non-significant and non-monotonic.

Treatment and recovery

Duration of GAD in the 12-month period was unrelated to 12-month treatment for the disorder (results not shown, but available on request). In developed countries, the lifetime treatment rate for GAD was significantly lower for the 1–2 month subgroup (46.3%) than for the other subgroups (50.7–53.9%), although the proportions were not very different in substantive terms. Duration was not associated with lifetime treatment in developing countries (Wald χ23 = 2.7, p = 0.4), probably because of low rates of GAD treatment there (18.5–31.4%).

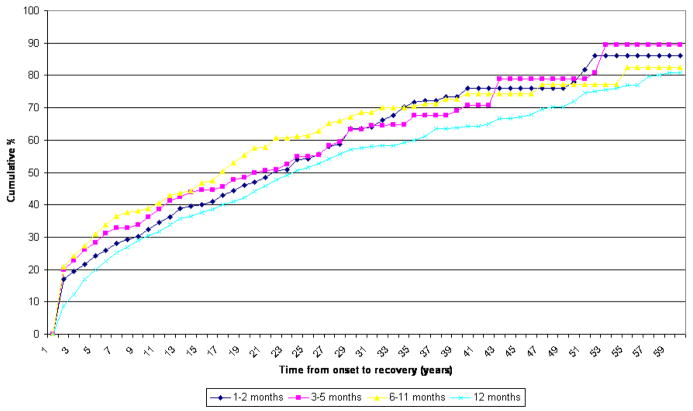

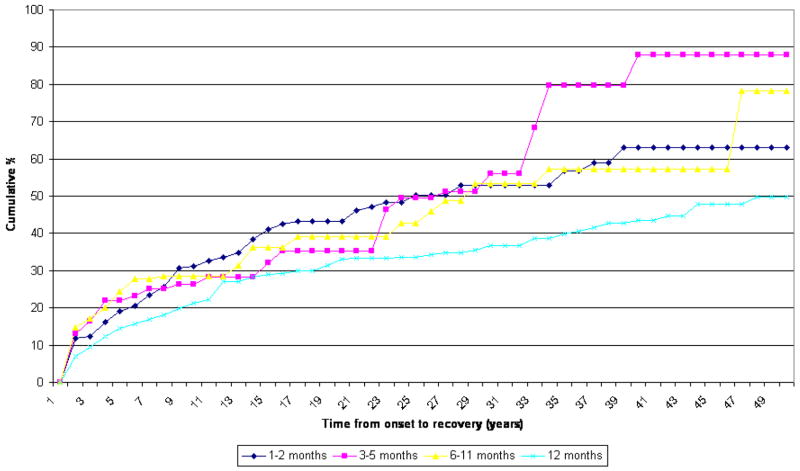

Recovery from GAD, defined as two or more continuous years without symptoms among lifetime cases, was shown in figure 2. For both country groups, the duration subgroups differ from one another significantly, but the patterns are similar. A lower proportion of the >12 month subgroups recover than other subgroups in the same period from onset. Regardless of duration, GAD is a chronic disorder, with only half of those affected recovering after about 20 to 25 years post-onset. An even more chronic course is found for the ≥ 12 month subgroup in developing countries, where the median time to recovery is much as 50 years after onset. A special finding appears in developed countries where the numbers of cases are higher. The 1–2 month subgroup and 3–5 months subgroup have a lower proportion of recovery than the 6–11 month subgroup, that is, the two subgroups take longer to have the same proportion of recovery than the 6–11 subgroup.

Figure 2.

Time to recovery - developed countries Chi-Square = 25.0 p-value < 0.0001

Recovery - developed countries Chi-Square = 15.0 p-value < 0.002

Discussion

Several limitations of the present study are worthy of note. One is the retrospective assessment of the onset, duration, and number of anxiety episodes. Although the probing strategy we used has been shown to improve recall of information such as age of onset (Knauper et al., 1999), it is possible that the quality of respondents’ recall varied. Recall bias may have been especially likely for respondents with multiple lifetime episodes of varying duration that occurred over a long period of time, or for recollection of more complex diagnostic criteria, such as the number of months when symptoms were present more days than not (Ruscio, 2002). A related limitation is the current lack of consensus among clinicians and researchers about when a GAD episode should be considered to have ended. The operational definition that we used (1 month of full symptom remission) was somewhat arbitrary and may have overestimated duration by requiring a full month without any symptoms rather than a month when symptoms occurred on fewer than half of the days. Although our use of a fully structured diagnostic instrument and rigorously trained lay interviewers enhanced reliability in the cross-national assessment of mental disorders, the CIDI does not allow symptom clarification and differential diagnosis in the same manner as clinician-administered semi-structured interviews. This might have resulted in inflated associations between GAD and other disorders. While clinical reappraisal studies have suggested reasonably good concordance between the CIDI and SCID diagnoses, these studies were performed in only a subset of WMH countries, including China, France, Italy, Spain, and the US (Haro et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2007b).

With these limitations in mind, the present study showed that the impact of shifting the GAD duration criterion is quite similar across developing and developed countries, though a few differences between the two country groups are worthy of mention. One is the lower prevalence of both lifetime and 12-month GAD in developing countries. This may reflect a generally lower level of psychiatric morbidity (Demyttenaere et al., 2004), higher diagnostic thresholds related to respondents having a lower level of mental health literacy, or other methodological factors that lead to a downward bias in the estimation of anxiety disorders in these countries (Shen et al., 2006; Chang et al., 2008). Another difference between developed and developing countries was about impairment. Respondents with GAD in developing countries reported less impairment on the SDS, even though they demonstrated similar days-out-of-role as their counterparts in developed countries. Unlike days out of role which are more objectively defined, there may be cross-cultural differences in appraising and responding to questions about how symptoms have interfered with home management, work, social life, and personal relationships. The final difference was the lower treatment rate of GAD in developing countries. This is expected as high levels of unmet needs for mental health treatment are pervasive in low-income countries (Wang et al., 2007).

These differences in prevalence, impairment, and treatment notwithstanding, GAD prevalence estimates showed similar increases in both groups of countries as the duration criterion was broadened. Moreover, varying the duration of GAD resulted in very similar changes in onset, course, impairment, comorbidity, and recovery rate in developing and developed countries. The findings are consistent with previous Western studies (Bienvenu et al., 1998; Maier et al., 2000; Carter et al., 2001; Kessler et al., 2005) and extend these studies by providing findings from developing countries that conducted the surveys using the same methodology.

Compared with respondents who met the DSM-IV duration requirement of 6 months, respondents with GAD duration of 3–5 months had generally similar age of onset, symptom severity, symptom persistence, role impairment, comorbidity with other mental disorders, suicide pattern, treatment pattern, and course of recovery. In cases where associations were found between duration and outcomes, differences between the 3–5 month and 6–11 month duration subgroups were either non-monotonic or inconsistent. Moreover, respondents with 3–5 month GAD recovered more slowly than those with 6–11 month GAD in developed countries. This is a further indication that GAD of less than 6 month duration is not necessarily a milder form of the disorder.

Unlike several Western studies that examined durations of 1 to 6 months and did not find duration to relate to the psychopathological profile of GAD (Bienvenu et al., 1998), we found that the ≥ 12 month subgroup was more impaired and slower to recover than the other subgroups. In developing countries where treatment was greatly limited, the median time to recovery was particularly prolonged. Our findings therefore do not completely support the view of critics that duration is of no utility in defining the severity of GAD (Rickels & Rynn, 2001). Because this subgroup represents a chronic form of GAD that is already captured by the DSM-IV 6-month criterion, it is not the focus of the controversy surrounding the duration criterion of GAD. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that episode durations of one year or longer may reflect a more severe form of GAD. It is possible that this more chronic form of the disorder may be associated with higher rates of comorbid Axis II pathology or other interpersonal difficulties (Yonkers et al., 2000).

Questions related to the duration of GAD are affected by how persistence and termination of episodes are defined. The DSM-IV duration criterion for GAD requires that excessive anxiety and worry occur “more days than not for at least 6 months” ((American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The criterion does not specify how the more than 50% of days with anxiety symptoms should be distributed within the 6-month period, or whether brief periods of complete symptom remission may occur. This is in contrast to the more explicit duration criterion of major depressive episode, in which depressed mood or anhedonia must be present “most of the day, nearly every day” for 2 weeks (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Studies with clinical samples from specialized treatment centers suggest that most patients with DSM-III-R GAD experienced anxiety more days than not (Yonkers et al., 1996), but it is unclear whether the same level of persistence would be found in community-based samples. In fact, our data suggest considerable variability in the course as well as duration of GAD symptoms, with the average respondent in the 1–2 month duration subgroup reporting a pattern of short episodes of anxiety recurring over many years. However, because subjective perceptions of symptom persistence do not always correspond to the objective number of days with anxiety (Ruscio, 2002), there is a need for prospective research that tracks symptoms on daily dairy measures for six months or more to characterize the course and to refine the criteria for GAD.

Our findings have implications on the duration requirement of GAD in the DSM-V. If the 6-month duration criterion is maintained, we recommend that the DSM-V provide greater description of the longitudinal variability of the course of anxiety. Instead of “more days than not for at least 6 months,” more emphasis can be put on the clinical significance, for example, of individuals who suffer from recurrent short episodes of impairing anxiety.

Shortening the duration criterion in the DSM-V, such as to one month, will increase the proportion of people who are diagnosed with GAD in both developed and developing countries and facilitate earlier clinical diagnosis. This modification is supported by our findings that individuals whose symptom duration falls short of the DSM-IV criterion typically suffer moderate to severe symptoms and impairment and have a risk of future mental disorders that is no different from that of respondents who meet the current duration criterion. Although an episode duration of less than 6 months may be considered subthreshold by DSM-IV standard, affected individuals are not necessarily “less ill.” Rather, the DSM-IV definition excludes a considerable number of people who suffer from GAD that is less than six months in duration but is nonetheless impairing and recurrent (Kessler et al., 2005).

There are, however, potential downsides to reducing the GAD duration requirement. In primary care settings where general practitioners may not have sufficient skills to evaluate pathological worry and quality psychological intervention is barely available, the adoption of a 1-month duration criterion of GAD may contribute to the pathologizing of normal stress responses and indiscriminant pharmacotherapy. The medicalization of normative anxiety responses to stress is especially likely to happen in developing countries where the quantity and quality of mental health resources are greatly limited and the chronic use of benzodiazepine tranquillizers is widespread (Lee et al., 2007a). If the duration criterion of GAD is shortened to 1 month in DSM-V, we would recommend a more objective assessment of pathological anxiety than using a subjective recall of having anxiety “more days than not” within the 1-month period so that clinicians can target treatment to those who need it most. Treatment can be further guided by supplementary assessment of severity such as the use of dimensional anxiety and impairment scales (Rickels & Rynn, 2001), presence of concurrent Axis II pathology (Yonkers et al., 2000), early-onset specific phobias, prior anxiety episodes (especially those that last 12 months or more), and other predictors of onset and persistence of psychopathology (Kessler et al., 2002) When thus identified, GAD based on 1-month duration criterion should not be equated with a diagnosis of adjustment disorder, which is often dismissed by clinicians as having no need for treatment. Instead, it should be a clinically significant condition which may be especially suitable for early intervention and prevention of secondary morbidity (Ruscio et al., 2007). Future trials should examine whether existing therapies would be cost-effective in treating 1-month GAD and preventing its recurrence and progression to chronicity (Heuzenroeder et al., 2004).

Acknowledgments

The surveys discussed in this article were carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative. We thank the WMH staff for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and data analysis. These activities were supported by the United States National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH070884), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the US Public Health Service (R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, and R01 DA016558), the Fogarty International Center (FIRCA R03-TW006481), the Pan American Health Organization, the Eli Lilly & Company Foundation, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. A complete list of WMH publications can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/. The Chinese World Mental Health Survey Initiative is supported by the Pfizer Foundation. The Colombian National Study of Mental Health (NSMH) is supported by the Ministry of Social Protection. The ESEMeD project is funded by the European Commission (Contracts QLG5-1999-01042; SANCO 2004123), the Piedmont Region (Italy), Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain (FIS 00/0028), Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología, Spain (SAF 2000-158-CE), Departament de Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya, Spain, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (CIBER CB06/02/0046, RETICS RD06/0011 REM-TAP), and other local agencies and by an unrestricted educational grant from GlaxoSmithKline. The Israel National Health Survey is funded by the Ministry of Health with support from the Israel National Institute for Health Policy and Health Services Research and the National Insurance Institute of Israel. The World Mental Health Japan (WMHJ) Survey is supported by the Grant for Research on Psychiatric and Neurological Diseases and Mental Health (H13-SHOGAI-023, H14-TOKUBETSU-026, H16-KOKORO-013) from the Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The Lebanese National Mental Health Survey (LEBANON) is supported by the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health, the WHO (Lebanon), Fogarty International, Act for Lebanon, anonymous private donations to IDRAAC, Lebanon, and unrestricted grants from Janssen Cilag, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, and Novartis.The Mexican National Comorbidity Survey (MNCS) is supported by The National Institute of Psychiatry Ramon de la Fuente (INPRFMDIES 4280) and by the National Council on Science and Technology (CONACyT-G30544- H), with supplemental support from the PanAmerican Health Organization (PAHO). Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand Mental Health Survey (NZMHS) is supported by the New Zealand Ministry of Health, Alcohol Advisory Council, and the Health Research Council. The Nigerian Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (NSMHW) is supported by the WHO (Geneva), the WHO (Nigeria), and the Federal Ministry of Health, Abuja, Nigeria. The South Africa Stress and Health Study (SASH) is supported by the US National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH059575) and National Institute of Drug Abuse with supplemental funding from the South African Department of Health and the University of Michigan. The Ukraine Comorbid Mental Disorders during Periods of Social Disruption (CMDPSD) study is funded by the US National Institute of Mental Health (RO1-MH61905). The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; U01-MH60220) with supplemental support from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF; Grant 044708), and the John W. Alden Trust.

Contributor Information

Sing Lee, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, PRC.

Adley Tsang, Hong Kong Mood Disorders Center, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, PRC.

Ayelet Meron Ruscio, Department of Psychology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, United States.

Josep Maria Haro, Sant Joan de Deu-SSM, Barcelona, Spain.

Dan Stein, University of Cape Town, UCT Department of Psychiatry, Cape Town, South Africa.

Jordi Alonso, Health Services Research Unit, IMIM-Hospital del mar; CIBER en Epidemiologia y Salud Publica (CIBERESP), Barcelona, Spain.

Matthias Angermeyer, Center for Public Mental Health, Gösing a.W, Austria.

Evelyn Bromet, SUNY Stony Brook, Stony Brook, New York, New York.

Koen Demyttenaere, University Hospital Gasthuisburg, Leuven, Belgium.

Giovanni de Girolamo, Regional Health Care Agency, Emilia-Romanga Region, Italy.

Ron de Graaf, Netherlands Institute of Mental Health and Addiction, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Oye Gureje, Department of Psychiatry, University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria.

Noboru Iwata, Hiroshima International University, Higashi-Hiroshima, Japan.

Elie G. Karam, Institute for Development, Research, Advocacy, and Applied Care (IDRAAC), St. George Hospital University Medical Center, Beirut, Lebanon

Jean-Pierre Lepine, Hospital Fernand Widal, Paris, France.

Daphna Levinson, Ministry of Health, Mental Health Services, Jerusalem, Israel.

Maria Elena Medina-Mora, National Institute of Psychiatry, Mexico City, Mexico.

Mark Oakley Browne, Department of Rural and Indigenous Health, School of Rural Health, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Victoria, Australia.

José Posada-Villa, Colegio Mayor de Cundinamarca University, Bogotá, Colombia.

Ronald C. Kessler, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, United States

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-IV-TR. 4. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, DSM-III-R. 3. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, D.C: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-III. 3. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Angst J, Gamma A, Joseph Bienvenu O, Eaton WW, Ajdacic V, Eich D, Rossler W. Varying temporal criteria for generalized anxiety disorder: prevalence and clinical characteristics in a young age cohort. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:1283–1292. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienvenu OJ, Nestadt G, Eaton WW. Characterizing generalized anxiety: temporal and symptomatic thresholds. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1998;186:51–56. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199801000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Davis GC. DSM-III generalized anxiety disorder: an empirical investigation of more stringent criteria. Psychiatry Research. 1985;15:231–238. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(85)90080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Di Nardo PA, Lehman CL, Campbell LA. Reliability of DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: implications for the classification of emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:49–58. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RM, Wittchen HU, Pfister H, Kessler RC. One-year prevalence of subthreshold and threshold DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder in a nationally representative sample. Depression and Anxiety. 2001;13:78–88. doi: 10.1002/da.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SM, Hahm BJ, Lee JY, Shin MS, Jeon HJ, Hong JP, Lee HB, Lee DW, Cho MJ. Cross-national difference in the prevalence of depression caused by the diagnostic threshold. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2008;106:159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine JP, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, de Girolamo G, Morosini P, Polidori G, Kikkawa T, Kawakami N, Ono Y, Takeshima T, Uda H, Karam EG, Fayyad JA, Karam AN, Mneimneh ZN, Medina-Mora ME, Borges G, Lara C, de Graaf R, Ormel J, Gureje O, Shen Y, Huang Y, Zhang M, Alonso J, Haro JM, Vilagut G, Bromet EJ, Gluzman S, Webb C, Kessler RC, Merikangas KR, Anthony JC, Von Korff MR, Wang PS, Brugha TS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Lee S, Heeringa S, Pennell BE, Zaslavsky AM, Ustun TB, Chatterji S WHO World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA : The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291:2581–2590. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feighner JP, Robins E, Guze SB, Woodruff RA, Jr, Winokur G, Munoz R. Diagnostic criteria for use in psychiatric research. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1972;26:57–63. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1972.01750190059011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition (SCID-I/NP) Biometrics Research, NewYork State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gureje O, Lasebikan VO, Kola L, Makanjuola VA. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of mental disorders in the Nigerian Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;188:465–471. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.5.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halli SS, Vaninadha Rao K. Advanced techniques of population analysis. Plenum Press; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Haro JM, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez S, Brugha TS, de Girolamo G, Guyer ME, Jin R, Lepine JP, Mazzi F, Reneses B, Vilagut G, Sampson NA, Kessler RC. Concordance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) with standardized clinical assessments in the WHO World Mental Health surveys. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2006;15:167–180. doi: 10.1002/mpr.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema JM, Prescott CA, Kendler KS. A population-based twin study of generalized anxiety disorder in men and women. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2001;189:413–420. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200107000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuzenroeder L, Donnelly M, Haby MM, Mihalopoulos C, Rossell R, Carter R, Andrews G, Vos T. Cost-effectiveness of psychological and pharmacological interventions for generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;38:602–612. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ. Clinical characteristics of familial generalized anxiety disorder. Anxiety. 1994;1:186–191. doi: 10.1002/anxi.3070010407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ. Generalized anxiety disorder in women. A population-based twin study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49:267–272. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820040019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Andrade LH, Bijl RV, Offord DR, Demler OV, Stein DJ. The effects of comorbidity on the onset and persistence of generalized anxiety disorder in the ICPE surveys. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:1213–1225. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Brandenburg N, Lane M, Roy-Byrne P, Stang PD, Stein DJ, Wittchen HU. Rethinking the duration requirement for generalized anxiety disorder: evidence from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:1073–1082. doi: 10.1017/s0033291705004538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knauper B, Cannell CF, Schwarz N, Bruce ML, Kessler RC. Improving the accuracy of major depression age of onset reports in the US National Comorbidity Survey. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1999;8:39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Tsang A, Chui H, Kwok K, Cheung E. A community epidemiological survey of generalized anxiety disorder in Hong Kong. Community Mental Health Journal. 2007a;43:319. doi: 10.1007/s10597-006-9077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Tsang A, Zhang MY, Huang YQ, He YL, Liu ZR, Shen YC, Kessler RC. Lifetime prevalence and inter-cohort variation in DSM-IV disorders in metropolitan China. Psychological Medicine. 2007b;37:61–71. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon AC, Olfson M, Portera L, Farber L, Sheehan DV. Assessing psychiatric impairment in primary care with the Sheehan Disability Scale. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 1997;27:93–105. doi: 10.2190/T8EM-C8YH-373N-1UWD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier W, Gansicke M, Freyberger HJ, Linz M, Heun R, Lecrubier Y. Generalized anxiety disorder (ICD-10) in primary care from a cross-cultural perspective: a valid diagnostic entity? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2000;101:29–36. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.101001029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Triangle Park. SUDAAN. NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rickels K, Rynn M. Overview and clinical presentation of generalized anxiety disorder. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2001;24:1–17. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70203-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio AM. Delimiting the boundaries of generalized anxiety disorder: differentiating high worriers with and without GAD. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2002;16:377–400. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00130-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio AM, Chiu WT, Roy-Byrne P, Stang PE, Stein DJ, Wittchen HU, Kessler RC. Broadening the definition of generalized anxiety disorder: effects on prevalence and associations with other disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2007;21:662–676. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen YC, Zhang MY, Huang YQ, He YL, Liu ZR, Cheng H, Tsang A, Lee S, Kessler RC. Twelve-month prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in metropolitan China. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:257–267. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade T, Andrews G. DSM-IV and ICD-10 generalized anxiety disorder: discrepant diagnoses and associated disability. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2001;36:45–51. doi: 10.1007/s001270050289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2004: Cultural liberty in today’s diverse world. United Nations Development Programme; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Angermeyer M, Borges G, Bruffaerts R, Tat Chiu W, DE Girolamo G, Fayyad J, Gureje O, Haro JM, Huang Y, Kessler RC, Kovess V, Levinson D, Nakane Y, Oakley Brown MA, Ormel JH, Posada-Villa J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Heeringa S, Pennell BE, Chatterji S, Ustun TB. Delay and failure in treatment seeking after first onset of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007;6:177–185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolter KM. Introduction to variance estimation. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Mental disorders :glossary and guide to their classification in accordance with the ninth revision of the international classification of diseases. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Yonkers KA, Dyck IR, Warshaw M, Keller MB. Factors predicting the clinical course of generalised anxiety disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science. 2000;176:544–549. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.6.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonkers KA, Warshaw MG, Massion AO, Keller MB. Phenomenology and course of generalised anxiety disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science. 1996;168:308–313. doi: 10.1192/bjp.168.3.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]