Abstract

The human adenovirus type 5 early region 1A (E1A) is one of two oncogenes present in the adenovirus genome and functions by interfering with the activities of cellular regulatory proteins. The E1A gene is alternatively spliced to yield five products. Earlier studies have revealed that E1A can regulate the function of thyroid hormone (T3) receptors (TRs). However, analysis in yeast compared to transfection studies in mammalian cell cultures yields surprisingly different effects. Here, we have examined the effect of E1A on TR function by using the frog oocyte in vivo system, where the effects of E1A can be studied in the context of chromatin. We demonstrate that different isoforms of E1A have distinct effects on TR function. The two longest forms inhibit both the repression by unliganded TR and activation by T3-bound TR. We further show that E1A binds to unliganded TR to displace the endogenous corepressor N-CoR, thus relieving the repression by unliganded TR. On the other hand, in the presence of T3, E1A inhibits gene activation by T3-bound TR indirectly, through a mechanism that requires its binding domain for the general coactivator p300. Taken together, our results thus indicate that E1A affects TR function through distinct mechanisms that are dependent upon the presence or absence of T3.

Keywords: adenoviral E1A, thyroid hormone receptor, corepressor, coactivator, chromatin

INTRODUCTION

Thyroid hormone receptors (TRs) are believed to mediate the vast majority of diverse biological effects of thyroid hormone (T3). TRs belong to the superfamily of nuclear hormone receptors [1, 2]. One of the unique features of TRs is that they can constitutively, regardless of ligand availability, bind to T3 response elements (TREs) in the promoter region of T3-response genes. In other words, TRs can adopt either the unliganded or the liganded conformation, and both unliganded and liganded TRs are recruited to TREs [3-6]. Various in vitro studies have demonstrated that unliganded TRs repress T3-response genes and liganded TRs activate the same genes. The dual effects of TRs are accomplished by recruiting mutually exclusive sets of coregulators to the target promoters [3, 4, 7-20]. Corepressor complexes composed of N-CoR (nuclear corepressor) or SMRT (silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid hormone receptors) with HDAC3 (histone deacetylase 3), TBL1 (transducin beta-like protein 1)/TBLR1 (TBL1-related protein 1), and GPS2 (G-protein pathway suppressor 2) associate with unliganded TR and deacetylate histones [13-16, 21-31]. The presence of T3 induces a conformational change in TR, promoting the release of corepressor complexes and recruitment of coactivator complexes such as those composed of SRCs (steroid receptor coactivators) with p300 and pCAF (p300 associated factor) that increase histone acetylation [10-13, 17-19] [32-38].

T3 is critical for adult organ function and development in vertebrates [2, 12, 39, 40]. The effects of T3 are predominantly mediated by TRs [2, 12, 41] and alterations of the function of cellular proteins such as TR by viral proteins are important mechanisms in disease development and progression. The human adenovirus type 5 early region 1A (E1A) was originally identified as one of two oncogenes that are present in the adenovirus genome and functions by interfering with the activities of cellular regulatory proteins [42-44]. The E1A gene is alternatively spliced to yield 5 mRNA products (Fig. 1). These spliced variants encode proteins ranging in size from 289 residues to 55 residues, among which E1A12S and E1A13S are the major products. E1A proteins, which do not directly bind DNA, associate with key various cellular proteins to regulate gene transcription and cell growth [42-50]. Using the human choriocarcinoma cell line, JEG3 cells, Wahlström GM et al. [51] demonstrated that the largest form of E1A, E1A13S, interacts with TR and activate TR-dependent gene transcription both in the absence and in the presence of T3. On the other hand, a recent study using a yeast system revealed that E1A13S protein interacts with TR and activate TR-dependent gene transcription only in the absence of T3 [20, 52]. The presence of T3 reduces the interaction of E1A with TR but E1A is able to downregulate TR-dependent gene transcription in the presence of T3 [20, 52]. It was proposed that this apparent discrepancy was due to the difference in the cellular context of co-regulatory proteins between yeast and mammalian cells. In contrast to mammalian cells, yeast is devoid of the p160 and p300/CBP co-activator proteins as well as the N-CoR and SMRT co-repressor proteins [52].

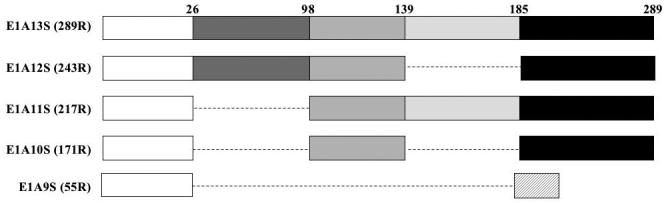

Figure 1. Schematic representation of E1A variants used in this study.

The E1A gene is alternatively spiced to yield 5 mRNA products ranging in size from 13S to 9S. These encode proteins ranging in size from 289 residues (R) to 55 R. The positions for the ends of the regions encoded by alternatively spliced exons are indicated on the top. Note that splicing preserves reading frame except where indicated by hatched box in E1A9S. E1A9S was not used in this study because it lacks most of the highly conserved functional domains.

In this study, we used the reconstituted frog oocyte system to examine the effects of E1A proteins in TR-dependent gene transcription. The frog oocyte system is an excellent model to explore the mechanism of TR-dependent gene regulation. First, minimal expression of endogenous TRs in frog oocytes allows us to define the basal transcription level of a TRE-targeted gene. Second, since frog oocytes contains abundant amount of endogenous co-regulators that are required for TR-dependent gene regulation, the expression of TR is sufficient to simulate the physiological situation of TR action. Third, since DNA injected into the oocyte nucleus is remodeled into a minichromosomal structure, we can explore TR-dependent gene regulation in the context of chromatin [4, 53]. The results presented here demonstrate that E1A binds to unliganded TR to displace endogenous corepressor N-CoR, thus relieving the repression by unliganded TR. In the presence of T3, E1A does not interact with TR but inhibits gene activation by T3-bound TR indirectly, most likely through its binding to the general coactivator p300. These results thus support the argument that cellular context and ligand can influence the effects of E1A on gene regulation by TR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning and constructs

JMB312, JMB1024, JMB1338, JMB1390, JMB2218, JMB2221, and JMB2246 vectors, which contain cDNAs for E1A13S, E1A12S, E1A11S, E1A10S, E1A12SΔ30-49, E1A12SΔ48-60, and E1A12SΔ61-69, respectively, were described previous or constructed by PCR based mutagenesis [20]. The sequence of these E1A variants and E1A12S mutants were tagged with a myc sequence at their 5′-end and subcloned into the T7Ts vector, which contains the 5′ and 3′-untranslated regions of the Xenopus laevis β-globin gene flanking the multiple cloning sites [54].

Luciferase assays using frog oocytes

The plasmids pSP64-FLAG-TRα and pSP64-RXRα [4] were used to synthesize the corresponding mRNAs with a SP6 in vitro transcription kit (mMESSAGE mMACHINE; Ambion), T7Ts-myc-E1A13S, 12S, 11S, 10S, E1A12SΔ30-49, E1A12SΔ48-60, and E1A12SΔ61-69 were used to synthesize the corresponding mRNAs with a T7 in vitro transcription kit (mMESSAGE mMACHINE; Ambion). The mRNAs for FLAG-TRα/RXR (5.75 ng/oocyte each) and/or mRNAs for myc-E1As (5.75 or 23 ng/oocyte) were injected into the cytoplasm of 12 Xenopus laevis stage VI oocytes. The reporter plasmid DNA (0.33 ng/oocyte), which contained the T3-dependent Xenopus TRβ promoter driving the expression of the firefly luciferase was injected into the oocyte nucleus, together with a control construct that contains the herpes simplex virus tk promoter driving the expression of Renilla luciferase (0.03 ng/oocyte). Following overnight incubation at 18°C in the absence or presence of 100 nM T3, oocytes were prepared for luciferase assay by the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay system (Promega), according to the manufacturer's recommendations. To verify the protein translation from the injected mRNAs, the same oocyte lysates were subjected to Western blotting using anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma) for detection of FLAG-TRα and anti-myc antibody (Invitrogen) for detection of myc-E1A proteins.

Co-immunoprecipitation using frog oocytes

The above-prepared mRNAs for FLAG-TRa/RXR (23 ng/oocyte each) and/or mRNA for myc-E1A12S (23 ng/oocyte) were injected into the cytoplasm of 20 Xenopus laevis stage VI oocytes. After overnight incubation at 18°C with or without 100 nM of T3, the oocytes were lysed in IP buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM glycerophosphate, 50 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science)). After centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, parts of the supernatant were kept as input samples and the rest were used for immunoprecipitation with Ezview Red ANTI-FLAG M2 Affinity Gel (Sigma). Each lysate was incubated with the gel for 4 hours and washed three times in the same IP buffer. The immunoprecipitates were boiled in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading buffer, separated on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and immunoblotted with anti-myc, anti-N-CoR [55], or anti-SRC3 antibody [36].

RESULTS

Differential effects of different E1A splice forms on TR function in vivo

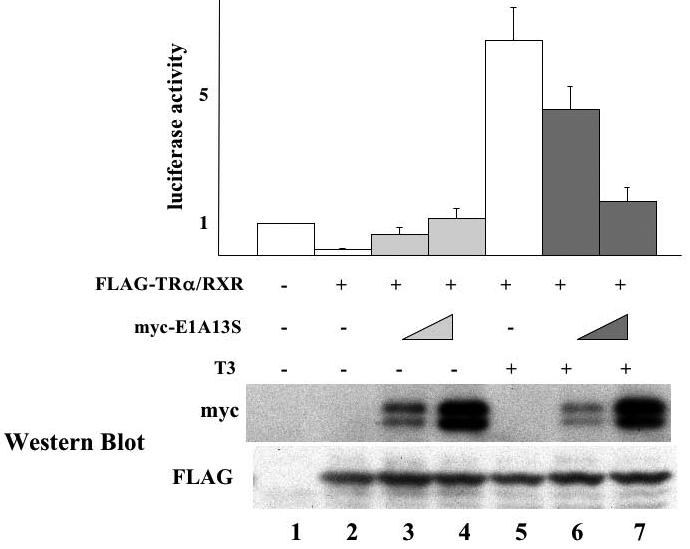

To study the effects of E1A on gene regulation by TR in the context of chromatin in vivo, we analyzed the effect of full length E1A13S on the transcription of a TR-target gene in the reconstituted X. laevis oocyte system [4]. As a reporter for T3-dependent transcriptional activity, a plasmid containing the T3-dependent promoter of Xenopus laevis TRβA gene driving the expression of firefly luciferase (TRE-Luc) was microinjected into the oocyte nucleus together with an internal control plasmid driving the expression of Renilla luciferase. Since the oocyte has little endogenous TR/RXR, in vitro transcribed mRNAs encoding FLAG-tagged Xenopus TRα and untagged RXR with or without the mRNA for myc-E1A13S were coinjected into the cytoplasm. After overnight incubation in the presence or absence of T3, the oocytes were lysed and assayed for luciferase activities. The ratio of firefly luciferase activity to Renilla luciferase was determined as a measure for transcription level from the reporter gene. In the absence of T3, over-expression of TR and RXR reduced the reporter gene transcription and E1A13S overexpression reversed this repression in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2, lanes 2-4). When T3 was added to the oocyte culture medium, the repression by unliganded TR/RXR was relieved and the promoter was further activated (Fig. 2, lane 5). Interestingly, unlike the promoter activation effect in the absence of T3, overexpression of E1A13S inhibited transcription in a dose-dependent manner in the presence of TR/RXR and T3 (Fig. 2, compare lanes 6-7 to lane 5).

Figure 2. E1A13S protein relieves unliganded-TR induced gene repression and inhibits liganded TR-induced gene activation in the reconstituted frog oocyte system.

The mRNAs for FLAG-TRa/RXR (5.75 ng/oocyte each) with or without increasing amounts of myc-tagged E1A13S mRNA (0.92 ng/oocyte or 4.6 ng/oocyte) were injected into the cytoplasm of the frog oocytes. The firefly luciferase reporter vector (TRE-Luc) together with the control Renilla luciferase plasmid (tk-Luc) was then injected into the nucleus. After overnight incubation with or without 100 nM of T3, the oocytes were lysed and assayed for luciferase activities (top panel). As a measure of the reporter gene transcription level, the ratio of firefly luciferase activity to Renilla luciferase activity was determined and was normalized with the basal level in the absence of T3 and TR as 1. The result from each group was expressed as a percentage of the basal transcription level that was obtained from the oocytes without TRα/RXR mRNA injection. This experiment was repeated 3 times. The same oocyte samples used in luciferase assay were subjected to Western blotting with anti-myc and anti-FLAG antibodies to detect the E1A and TR expression, respectively and representative results were shown in the lower panels, confirming the protein expression of E1A13S and FLAG-TRα.

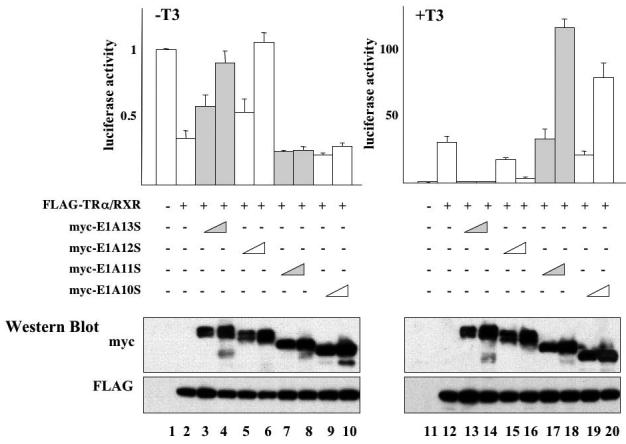

We next investigated whether different splice forms of E1A had similar effect on TR function. We analyzed 4 of the 5 splice forms. E1A9S was not analyzed as it lacked all of the common functional domains except the N-terminal 26 aa, thus making it difficult to interpret the outcome of the experiment. We microinjected mRNA for myc-tagged E1A13S, E1A12A, E1A11S, or E1A10S together with mRNAs for TR/RXR into the cytoplasm of Xenopus oocytes, followed by the injection of the reporter DNA as above. Luciferase assays showed that E1A12S behaved similarly as E1A13S, i.e., inhibited both transcription repression by unliganded TR (Fig. 3, lanes 5-6) and activation by liganded TR (Fig. 3, lanes 15-16). On the other hand, E1A11S and E1A10S had no effect on the repression by unliganded TR (Fig. 3, lanes 7-10). Interestingly, at high concentration, they enhanced the gene activation by T3-bound TR (Fig. 3, lanes 17-20), in contrast to the inhibition observed with E1A13S and E1A12S (Fig. 3, lanes 13-16). These contrasting effects were clearly due to isoform specific functions since similar levels of the different isoforms were expressed after mRNA injection (Fig. 3, bottom panels).

Figure 3. Differential effects of E1A variants on TR-regulated gene transcription.

The mRNAs for FLAG-TRα/RXR (5.75 ng/oocyte each) with or without increasing amounts of myc-tagged E1A13S, 12S, 11S, or 10S mRNA (0.92 ng/oocyte or 4.6 ng/oocyte) were injected into the cytoplasm of the frog oocytes as indicated. After overnight incubation with or without 100 nM of T3, the oocytes were lysed for luciferase assays. The ratio of firefly luciferase activity to Renilla luciferase activity was determined as a measure of the reporter gene transcription level with the basal level in the absence TR set to 1 (top panels). The same oocyte samples were subjected to Western blotting with anti-myc and anti-FLAG antibodies to confirm the protein expression (lower panels). This experiment was repeated twice with similar results. As observed with E1A13S, E1A12S derepressed unliganded TR-induced gene repression and inhibits liganded TR-induced gene activation. In contrast, the shorter forms of E1A, E1A11S and E1A10S, enhanced liganded TR-induced gene activation. E1A11S and E1A10S had little effect on unliganded TR-induced gene repression. Note that the + and −T3 samples were plotted on different scales to highlight the effects of E1A.

E1A competes with N-CoR for binding to TR in the absence of T3

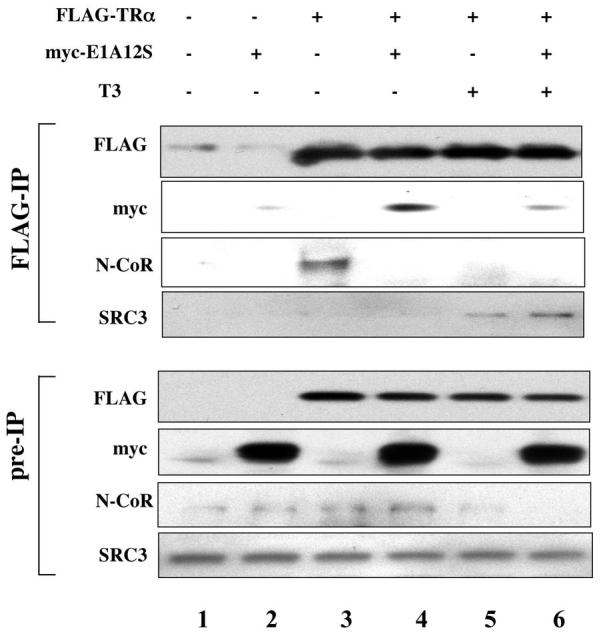

Earlier studies have shown that E1A is capable of binding to unliganded TR and that full length N-CoR could competitively inhibit the binding and functional effects of E1A [20, 52]. To investigate whether E1A affected TR function by competing for binding to TR, we carried out co-immunoprecipitation assay to analyze the binding of endogenous cofactors to TR in the presence or absence of E1A. (Due to the similar effects of E1A12S and E1A13S and the smaller size of E1A12S, we chose E1A12S for the remainder of the studies). We microinjected mRNAs for myc-E1A12S, FLAG-TR, and RXR into Xenopus oocytes. After overnight incubation in the presence or absence of T3, oocyte lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG antibody against the TR. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by western blot with different antibodies. As expected, similar amounts of FLAG-TR were immunoprecipitated in all samples with mRNA injection (Fig. 4, lanes 3-6). Western blot with the antibody against the myc-tag indicated that E1A was co-immunoprecipitated with TR in the absence T3 (Fig. 4, lane 3) while in the presence of T3, the co-immunoprecipitated E1A was significantly reduced (Fig. 4, lane 6). Similarly, the corepressor N-CoR was also co-immunoprecipitated with TR in the absence of T3 (Fig. 4, lane 3). As expected, N-CoR dissociated from TR in the presence of T3 (Fig. 4, lane 5). In the presence of E1A, N-CoR binding to TR was abolished even in the absence of T3 (Fig. 4, lane 4 vs. 3), suggesting that E1A competed against N-CoR for binding to unliganded TR. On the other hand, the coactivator SRC3 was, expectedly, not bound to unliganded TR (Fig. 4, lanes 3) but bound to TR in the presence of T3 (Fig. 4, lane 5). This liganded-dependent binding of SRC3 to TR was not significantly affected by E1A overexpression (Fig. 4, lane 6), consistent with the reduced binding of E1A to TR in the presence of T3.

Figure 4. E1A 12S competes against corepressor binding to unliganded TR but not coactivator binding to T3-bound TR.

The mRNAs for FLAG-TRα/RXR (23 ng/oocyte each) with or without myc-E1A 12S mRNA (4.6 ng/oocyte) were injected into the cytoplasm of oocytes as indicated. After overnight incubation with or without 100 nM of T3, the oocytes were lysed and subjected to IP with anti-FLAG antibody against TRα. Pre-IP lysates and IP samples were immunoblotted with anti-FLAG, anti-myc, anti-N-CoR, and anti-SRC3 antibodies. Myc-E1A 12S was co-immunoprecipitated with FLAG-TR in the sample without T3 treatment (lane 4). The amount of co-immunoprecipitated myc-E1A12S was markedly reduced in T3 treated sample (lane 6). Overexpression of myc-E1A12S dissociated the endogenous corepressor N-CoR from FLAG-TR, resembling T3 treatment (lanes 3-5). Unlike T3 treatment, however, the coactivator SRC3 binding to FLAG-TR was not affected by myc-E1A12S in the presence or absence of T3 (lanes 3-6). Note that the N-CoR signal in the pre-IP samples was expected to be the same in all lanes as it was from endogenous N-CoR in the oocyte. However, it appeared to be stronger in the center lanes but weaker in the flanking ones, especially lane 6. This was likely due to difficulty to transfer the large protein, resulting in some variation with the center lanes transferred better than the flanking ones. However, this does not affect the conclusion about the competition by myc-E1A12S against endogenous N-CoR for binding to TR as shown by lanes 3 and 4 in the center.

The p300-binding domain of E1A is required for its ability to inhibit TR function in the presence of T3

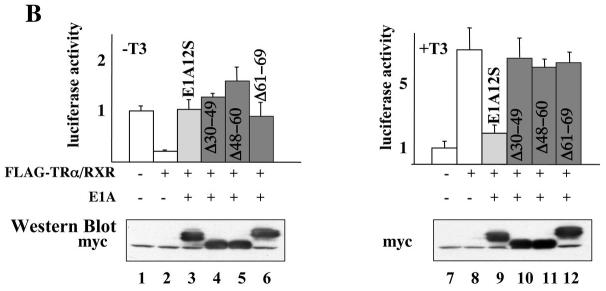

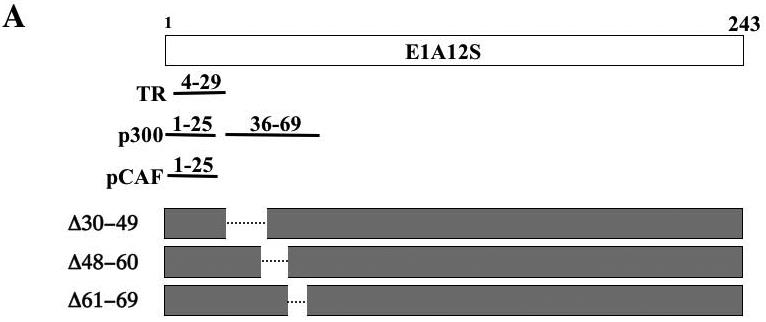

The N-terminus of E1A binds to the general transcription coactivators p300 and pCAF as well as to TR via a short peptide CoR-NR interaction motif at amino acids 20-28 (LDQLIEEVL) (Fig. 5A) [20]. The binding of p300 requires E1A amino acids 1-25 and 36-69 [56] and pCAF binding requires amino acids 1-25 [57, 58]. Thus, to investigate how E1A inhibits gene activation by liganded TR, we analyzed the effects of three E1A mutants that retained the ability to bind to TR and pCAF but not p300 (Fig. 5A). As shown in Fig. 5B, the wild type E1A12S again inhibited both the repression by unliganded TR (lane 3) and activation by T3-bound TR (lane 9). The three mutant E1A12S all inhibited the repression by unliganded TR (Fig. 5B, lanes 4-6), just like the wild type E1A12S. On the other hand, all these mutants failed to affect the activation by TR in the presence of T3 (Fig. 5B, lanes 10-12). Since the mutants bind pCAF but not p300 [57, 58], our results suggest that E1A inhibits gene activation by T3-bound TR through binding p300 but not pCAF.

Figure 5. Effects of mutant E1A12S on TR-regulated reporter gene transcription.

(A). Schematic diagrams of E1A12S and its mutants. The regions in wild-type E1A12S protein that are required for interaction with TR, p300, and pCAF are shown. Three deletion mutant constructs, Δ30–49, Δ48–60, and Δ61–69 were generated in the context of the E1A 12S cDNA by PCR based mutagenesis. All of these mutants retained the TR binding site (amino acids 4-29 [52]) and the ability to bind pCAF (amino acids 1-25 [57, 58]). Mutants Δ30–49, Δ48–60 and Δ61–69 are unable to bind p300 [56]).

(B). The mRNAs for FLAG-TRα/RXR (5.75 ng/oocyte each) with or without the mRNA for myc-tagged E1A12S, Δ30–49, Δ48–60, or Δ61–69 (4.6 ng/oocyte) were injected into the cytoplasm of the frog oocytes as indicated. The reporter DNA was injected next. After overnight incubation with (lanes 7-12) or without (lanes 1-6) 100 nM of T3, the oocytes were lysed for luciferase assays. The ratio of firefly luciferase activity to Renilla luciferase activity was determined as a measure of the reporter gene transcription level with the basal level in the absence TR set to 1 (top panels). The same oocyte samples were subjected to Western blotting with anti-myc antibody to show similar levels of the expression of different E1A mutants (bottom panels). As shown in left panel, all of these mutants de-repressed unliganded TR-induced gene repression just like E1A12S. In contrast to E1A12S, which inhibited liganded TR-induced gene activation, all these mutants had minimal effect on liganded TR-induced gene activation. This experiment was repeated twice with similar results.

DISCUSSION

The human adenoviral gene E1A encodes 5 proteins due to alternative splicing. The E1A proteins have been shown to affect diverse cellular processes, leading to disease development. Earlier studies have shown that the longest form of E1A, E1A13S, is capable of affecting transcriptional regulation by TR. Interestingly, different results were obtained in the yeast model system compared to the mammalian cell culture transfection studies, suggesting that cellular context and/or chromatin structure may influence how E1A affects TR function. By using the reconstituted frog oocyte model system, where the effect of E1A can be studied in the context chromatin in vivo, we have shown for the first time that different E1A isoforms have distinct effects on gene regulation by TR. More importantly, we show that E1A inhibits gene regulation by TR in both the presence and absence of T3 but with distinct mechanisms.

In the reconstituted frog oocyte system, the reporter gene is assembled into chromatin and this allows one to study both gene repression by unliganded TR and activation by liganded TR in the context chromatin [4, 53]. Overexpression of E1A13S inhibited the repression by unliganded TR as well as the activation by T3-bound TR. While these findings appear to differ from the yeast studies [20, 52] and the transient transfection studies in mammalian cell cultures, a careful analysis suggests that results are consistent in several key aspects. First, in the absence of T3, E1A enhanced transcription by unliganded TR in all three systems (In the transient transfection assays [51], although the authors focused the discussion on the effects in the presence of T3, there was clear upregulation of the reporter gene expression in the absence of T3. In fact, the fold enhancement in the absence of T3 appeared to be similar than that in the presence of T3). This is consistent with the binding of E1A to unliganded TR to release corepressors as we have shown in this study. In yeast, there is no repression by unliganded TR due to the lack of equivalent N-CoR type of corepressors that TRs utilize in vertebrate cells and thus, a different mechanism would likely exist there. Second, our immunoprecipitation data demonstrated for the first time that TR binds to E1A in vivo in the absence of T3. This is consistent with the two hybrid studies in yeast and with the in vitro GST-fusion protein pull-down assays in earlier studies [20, 52]. Third, our immunoprecipitation data showed that TR binding to E1A in vivo was reduced in the presence of T3. While this contrasts with the in vitro GST-fusion protein pull-down assays that showed that TR bound to E1A largely independent of T3, it is consistent with the yeast two-hybrid assays that showed a T3-induced dissociation of E1A from TR in vivo [20, 52]. Taken together, these data suggest that the different findings on the binding between TR and E1A were likely due to either inappropriate conformation of the proteins in the in vitro assays or more likely the involvement of other proteins that rendered the dissociation of E1A from TR T3-dependent in vivo.

Of the three studies conducted in different model systems to date, one of the major differences among the studies is that we observed an inhibition of T3-induced activation by E1A. In mammalian cells, E1A further activated the reporter while in yeast, the constitutive activation induced by E1A was downregulated in the presence of T3 and overcome whenever SRC1 or GRIP1 coactivators were present [20, 52]. This discrepancy is likely due to the difference in cellular context and/or the chromatin structure of the reporter. As indicated above, E1A had much weaker or little interaction with TR in vivo when T3 was present. Thus, it is unclear how E1A influences TR function when T3 is present. Our mutational analysis provided one possible mechanism. Any deletions affecting the p300 interacting domains of E1A abolished the inhibition of E1A on transcriptional activation by liganded TR but not on the repression by unliganded TR. This suggests that E1A affected TR function through its association with p300, a protein that is absent in the cellular context of yeast. Liganded TR is known to bind coactivators such as SRCs [10-13, 17-19] [35, 36, 38]. SRCs in turn form large complexes containing p300/CBP [32-34, 37]. Thus, it is possible that E1A interferes with liganded TR in vivo by disrupting SRC-p300 type of coactivator complexes important for gene activation either through squelching or at the target promoter. As yeast lacks the SRC type of coactivators, E1A, therefore, has little effect on the promoter activity in the presence of T3. On the other hand, the different levels and/or compositions of coactivators present in the mammalian JEG cells used in the transient transfection study compared to those in the frog oocyte might underlie the observed enhancement by E1A on gene activation by liganded TR in JEG cells. Alternatively, the SRC-p300 coactivator complexes may play a more critical role in the frog oocyte system, where the promoter DNA is packaged into chromatin. The interaction of E1A with p300 may interfere with the histone acetyltransferase activity important for the activation on this chromatinized template. In the transient transfection studies in JEG cells, the reporter plasmid likely has a less compact chromatin structure. In this case, the histone acetyltransferase activity of SCR-p300 complexes may thus not be critical. This coupled with different cofactor compositions and levels is likely responsible for the observed activation by E1A, which functions as an activator of viral transcription [42-44]. This cellular context-dependent effects of E1A on TR function clearly deserves further studies in the future as this will not only help our understanding on how TR functions but also have implications on the pathogenic effects of E1A.

E1A has 5 different spliced forms. With the exception of the smallest form, all differ from each other by the inclusion of different number of alternatively spliced domains. Interestingly, the two longest forms, E1A13S and E1SA12S, both contain the N-terminal TR- and p300-binding domains and can inhibit the repression and activation by TR in the absence and presence of T3, respectively. In contrast, the two shorter forms, E1A11S and E1A10S, lack the intact N-terminal domains for binding to TR and p300, and failed to inhibit either the repression by unliganded TR or the activation by T3-bound TR. Instead, at high levels of overexpression, these short forms actually enhanced gene activation by TR in the presence of T3. These interesting findings may help to explain some of the differences observed in the earlier studies in yeast and JEG cells. First, although in vitro GST-fusion protein pull-down assays suggest that E1A has multiple regions that bind to TR [20, 51, 52], a yeast two-hybrid assay showed that the N-terminal 29 amino acids were essential for the interaction in vivo [20] and further studies identified a leucine-rich CoR-NR box consensus motif in the N-terminal (20-28) amino acids of E1A as well as in the interacting domains of N-CoR and SMRT [52]. Our transcription assay in vivo also showed a requirement for this region for interaction with TR in vivo. Specifically, the isoforms produced as a result of alternative splicing lack amino acids 26-98. This removes several key residues required for interaction with TR, and these E1A isoforms lost the ability to inhibit repression by unliganded TR. Thus, while other regions of E1A may interact with TR in vitro, the interaction is likely too weak in vivo and/or not able to disrupt the interaction between endogenous corepressors and unliganded TR in order to affect repression. Second, the smaller isoforms E1A11S and E1A10S also lack the functional domain for binding to p300 and pCAF. Consistent with our studies with the E1A mutants, these forms failed to inhibit activation by T3-bound TR. Furthermore, the ability of these short forms to enhance activation by TR in the presence of T3 also supports the model proposed above. Specifically, SRC-p300 complexes play an essential role in T3-dependent gene activation in the frog oocyte system. In the absence of inhibition of the activation due to E1A interaction with p300, the activation effects of other regions of the multifunctional E1A proteins now become detectable. In JEG cells, SRC-p300 complexes may be less critical for gene activation by liganded TR or function through a mechanism that cannot be disrupted by E1A binding to p300, E1A thus does not inhibit gene activation by T3-TR through its N-terminal p300 binding domain but can enhance the transcription through its C-terminal domains. In this regard, it is worth noting that yeast lacks an N-CoR suppressor of TR in the absence of ligand. N-CoR, when coexpressed in yeast, can function as a repressor. Interestingly, however, spliced variants of N-CoR devoid of its repressor domains can act as an activator via its intact interacting domains (CoR-NR box motifs) [52, 59]. Since the cellular context of yeast also lacks SRC-p300 complexes needed for E1A to inhibit gene activation by T3-TR, E1A functions as a TR coactivator in this model system [20, 52, 59]. Clearly, further studies are needed to clarify all the details of the mechanism.

In conclusion, our studies here suggest that E1A can affect the function of both unliganded TR and T3-bound TR but through distinct mechanisms, inhibiting repression through direct competition against corepressors for binding to TR and affecting activation indirectly through its interaction with coactivators such as p300. Both E1A and TR are known oncogenes. Unliganded TR mimics the viral oncogene v-erbA, the viral homolog of TR that cannot bind to T3, in promoting cell proliferation and inhibit cell differentiation, while liganded TR does the opposite in cell cultures [60-63]. Thus, it will be of interest in the future to investigate how wild type and different mutant E1As may interact with TR in regulating cell growth and differentiation in different cells types with different cofactor compositions. Such studies will likely provide novel insights on how viruses utilize various cellular mechanisms to transform host cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of NICHD, NIH, unrestricted educational grants from the Joseph and Mildred Sonshine Family Centre for Head and Neck Diseases at Mount Sinai Hospital, and the Julius Kuhl Family Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, et al. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83:835–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lazar MA. Thyroid hormone receptors: multiple forms, multiple possibilities. Endocr Rev. 1993;14:184–93. doi: 10.1210/edrv-14-2-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW. Molecular mechanisms of action of steroid/thyroid receptor superfamily members. Ann Rev Biochem. 1994;63:451–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.002315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong J, Shi Y-B. Coordinated regulation of and transcriptional activation by Xenopus thyroid hormone and retinoid X receptors. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18479–18483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.31.18479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sachs LM, Shi Y-B. Targeted chromatin binding and histone acetylation in vivo by thyroid hormone receptor during amphibian development. PNAS. 2000;97:13138–13143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.260141297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perlman AJ, Stanley F, Samuels HH. Thyroid hormone nuclear receptor. Evidence for multimeric organization in chromatin. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:930–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Puzianowska-Kuznicka M, Damjanovski S, Shi Y-B. Both thyroid Hormone and 9-cis Retinoic Acid receptors are Required to Efficiently mediate the Effects of Thyroid Hormone on Embryonic Development and Specific Gene Regulation in Xenopus laevis. Mol. And Cell Biol. 1997;17:4738–4749. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fondell JD, Roy AL, Roeder RG. Unliganded thyroid hormone receptor inhibits formation of a functional preinitiation complex: implications for active repression. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1400–10. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7b.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsia VS-C, Wang H, Shi Y-B. Involvement of Chromatin and Histone Acetylation in the Regulation of HIV-LTR by Thyroid Hormone Receptor. Cell Research. 2001;11:8–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ito M, Roeder RG. The TRAP/SMCC/Mediator complex and thyroid hormone receptor function. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2001;12:127–134. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(00)00355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rachez C, Freedman LP. Mechanisms of gene regulation by vitamin D(3) receptor: a network of coactivator interactions. Gene. 2000;246:9–21. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yen PM. Physiological and molecular basis of thyroid hormone action. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:1097–142. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang J, Lazar MA. The mechanism of action of thyroid hormones. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2000;62:439–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.62.1.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burke LJ, Baniahmad A. Co-repressors 2000. FASEB J. 2000;14:1876–88. doi: 10.1096/fj.99-0943rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jepsen K, Rosenfeld MG. Biological roles and mechanistic actions of co-repressor complexes. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:689–98. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.4.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones PL, Shi Y-B. N-CoR-HDAC corepressor complexes: Roles in transcriptional regulation by nuclear hormone receptors. In: Workman JL, editor. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology: Protein Complexes that Modify Chromatin. Vol. 274. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 2003. pp. 237–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang Z-Q, Li J, Sachs LM, Cole PA, Wong J. A role for cofactor–cofactor and cofactor–histone interactions in targeting p300, SWI/SNF and Mediator for transcription. EMBO J. 2003;22:2146–2155. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKenna NJ, O'Malley BW. Nuclear receptors, coregulators, ligands, and selective receptor modulators: making sense of the patchwork quilt. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;949:3–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rachez C, Freedman LP. Mediator complexes and transcription. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:274–80. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00209-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meng X, Yang YF, Cao X, et al. Cellular context of coregulator and adaptor proteins regulates human adenovirus 5 early region 1A-dependent gene activation by the thyroid hormone receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:1095–1105. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horlein AJ, Naar AM, Heinzel T, et al. Ligand-independent repression by the thyroid hormone receptor mediated by a nuclear receptor co-repressor. Nature. 1995;377:397–404. doi: 10.1038/377397a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen JD, Evans RM. A transcriptional co-repressor that interacts with nuclear hormone receptors. Nature. 1995;377:454–457. doi: 10.1038/377454a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, Wang J, Wang J, et al. Both corepressor proteins SMRT and N-CoR exist in large protein complexes containing HDAC3. Embo J. 2000;19:4342–4350. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guenther MG, Lane WS, Fischle W, Verdin E, Lazar MA, Shiekhattar R. A core SMRT corepressor complex containing HDAC3 and TBL1, a WD40-repeat protein linked to deafness. Genes & Devel. 2000;14:1048–1057. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones PL, Sachs LM, Rouse N, Wade PA, Shi YB. Multiple N-CoR complexes contain distinct histone deacetylases. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8807–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000879200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang J, Kalkum M, Chait BT, Roeder RG. The N-CoR-HDAC3 nuclear receptor corepressor complex inhibits the JNK pathway through the integral subunit GPS2. Mol Cell. 2002;9:611–623. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00468-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Underhill C, Qutob MS, Yee SP, Torchia J. A novel nuclear receptor corepressor complex, N-CoR, contains components of the mammalian SWI/SNF complex and the corepressor KAP-1. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:40463–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007864200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wen YD, Perissi V, Staszewski LM, et al. The histone deacetylase-3 complex contains nuclear receptor corepressors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:7202–7207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. The coregulator exchange in transcriptional functions of nuclear receptors. Genes Dev. 2000;14:121–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoon H-G, Chan DW, Huang ZQ, et al. Purification and functional characterization of the human N-CoR complex: the roles of HDAC3, TBL1 and TBLR1. Embo J. 2003;22:1336–1346. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tomita A, Buchholz DR, Shi Y-B. Recruitment of N-CoR/SMRT-TBLR1 corepressor complex by unliganded thyroid hormone receptor for gene repression during frog development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:3337–3346. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.8.3337-3346.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen H, Lin RJ, Schiltz RL, et al. Nuclear receptor coactivator ACTR is a novel histone acetyltransferase and forms a multimeric activation complex with P/CAF and CBP/p300. Cell. 1997;90:569–580. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80516-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Voegel JJ, Heine MJ, Tini M, Vivat V, Chambon P, Gronemeyer H. The coactivator TIF2 contains three nuclear receptor-binding motifs and mediates transactivation through CBP binding-dependent and -independent pathways. EMBO J. 1998;17:507–519. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Demarest SJ, Martinez-Yamout M, Chung J, et al. Mutual synergistic folding in recruitment of CBP/p300 by p160 nuclear receptor coactivators. Nature. 2002;415:549–553. doi: 10.1038/415549a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Onate SA, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW. Sequence and characterization of a coactivator for the steroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science. 1995;270:1354–7. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paul BD, Fu L, Buchholz DR, Shi Y-B. Coactivator recruitment is essential for liganded thyroid hormone receptor to initiate amphibian metamorphosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:5712–5724. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5712-5724.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paul BD, Buchholz DR, Fu L, Shi Y-B. SRC-p300 coactivator complex is required for thyroid hormone induced amphibian metamorphosis/ J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:7472–7481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607589200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paul BD, Buchholz DR, Fu L, Shi Y-B. Tissue- and gene-specific recruitment of steroid receptor coactivator-3 by thyroid hormone receptor during development. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:27165–27172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503999200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shi Y-B. Amphibian Metamorphosis: From morphology to molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hetzel BS. The story of iodine deficiency: An international challenge in nutrition. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buchholz DR, Paul BD, Fu L, Shi YB. Molecular and developmental analyses of thyroid hormone receptor function in Xenopus laevis, the African clawed frog. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2006;145:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frisch SM, Mymryk JS. Adenovirus-5 E1A: paradox and paradigm. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:441–452. doi: 10.1038/nrm827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mymryk JS, Smith M. Influence of the adenovirus 5 E1A oncogene on chromatin remodeling. Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;75:95–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pelka P, Ablack JN, Fonseca GJ, Yousef AF, Mymryk JS. Intrinsic structural disorder in adenovirus E1A: a viral molecular hub linking multiple diverse processes. J Virol. 2008;82:7252–63. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00104-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whyte P, Buchkovich KJ, Horowitz JM, et al. Association between an oncogene and an anti-oncogene: the adenovirus E1A proteins bind to the retinoblastoma gene product. Nature. 1988;334:124–9. doi: 10.1038/334124a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chakravarti D, Ogryzko V, Kao HY, et al. A viral mechanism for inhibition of p300 and PCAF acetyltransferase activity. Cell. 1999;96:393–403. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80552-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hamamori Y, Sartorelli V, Ogryzko V, et al. Regulation of histone acetyltransferases p300 and PCAF by the bHLH protein twist and adenoviral oncoprotein E1A. Cell. 1999;96:405–13. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80553-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O'Connor MJ, Zimmermann H, Nielsen S, Bernard HU, Kouzarides T. Characterization of an E1A-CBP interaction defines a novel transcriptional adapter motif (TRAM) in CBP/p300. J Virol. 1999;73:3574–81. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3574-3581.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reid JL, Bannister AJ, Zegerman P, Martinez-Balbas MA, Kouzarides T. E1A directly binds and regulates the P/CAF acetyltransferase. Embo J. 1998;17:4469–77. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.15.4469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schaeper U, Boyd JM, Verma S, Uhlmann E, Subramanian T, Chinnadurai G. Molecular cloning and characterization of a cellular phosphoprotein that interacts with a conserved C-terminal domain of adenovirus E1A involved in negative modulation of oncogenic transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:10467–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wahlstrom GM, Vennstrom B, Bolin MB. The adenovirus E1A protein is a potent coactivator for thyroid hormone receptors. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:1119–1129. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.7.0316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meng X, Webb P, Yang YF, et al. E1A and a nuclear receptor corepressor splice variant (N-CoRI) are thyroid hormone receptor coactivators that bind in the corepressor mode. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:6267–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501491102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wong J, Shi YB, Wolffe AP. A role for nucleosome assembly in both silencing and activation of the Xenopus TR beta A gene by the thyroid hormone receptor. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2696–711. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.21.2696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tomita A, Buchholz DR, Obata K, Shi Y-B. Fusion protein of retinoic acid receptor a with promeyelocytic leukaemia protein or promyelocytic leukaemia zinc-finger protein recruits N-CoR-TBLR1 corepressor complex to repress transcription in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:30788–30795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303309200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sachs LM, Jones PL, Havis E, Rouse N, Demeneix BA, Shi Y-B. N-CoR recruitment by unliganded thyroid hormone receptor in gene repression during Xenopus laevis development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:8527–8538. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.24.8527-8538.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mymryk JS, Lee RW, Bayley ST. Ability of adenovirus 5 E1A proteins to suppress differentiation of BC3H1 myoblasts correlates with their binding to a 300 kDa cellular protein. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:1107–15. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.10.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lang SE, Hearing P. The adenovirus E1A oncoprotein recruits the cellular TRRAP/GCN5 histone acetyltransferase complex. Oncogene. 2003;22:2836–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shuen M, Avvakumov N, Walfish PG, Brandl CJ, Mymryk JS. The adenovirus E1A protein targets the SAGA but not the ADA transcriptional regulatory complex through multiple independent domains. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30844–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201877200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meng X, Arulsundaram VD, Yousef AF, et al. Corepressor/coactivator paradox: potential constitutive coactivation by corepressor splice variants. Nuclear Receptor Signaling. 2006;4:1–4. doi: 10.1621/nrs.04022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bauer A, Mikulits W, Lagger G, Stengl G, Brosch G, Beug H. The thyroid hormone receptor functions as a ligand-operated developmental switch between proliferation and differentiation of erythroid progenitors. Embo J. 1998;17:4291–4303. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.15.4291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Beug H, Mullner EW, Hyman MJ. Insights into erythroid differentiation obtained from studies on av ian erythroblastosis virus. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1994;6:816–824. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wahlström GM, Harbers M, Vennström B. The oncoprotein P75gag-v-erbA represses thyroid hormone induced transcription only via response elements containing palindromic half-sites. Oncogene. 1996;13:843–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gandrillon O, Rascle A, Samarut J. The v-erbA oncogene-A super tool for dissecting the involvement of nuclear hormone receptors in differentiation and neoplasia. Int J Oncol. 1995;6:215–231. doi: 10.3892/ijo.6.1.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]