Abstract

The extract of plant Shilianhua (SLH; Sinocrassula indica Berge) is a component in a commercial product for control of blood glucose. However, it remains to be investigated whether the SLH extract enhances insulin sensitivity in a model of type 2 diabetes. To address this question, the SLH crude extract was fractionated into four parts on the basis of polarity, and bioactivities of each part were tested in cells. One of the fractions, F100, exhibited a strong activity in the stimulation of glucose consumption in vitro. Glucose consumption was induced significantly by F100 in 3T3-L1 adipocytes, L6 myotubes, and H4IIE hepatocytes in the absence of insulin. F100 also increased insulin-stimulated glucose consumption in L6 myotubes and H4IIE hepatocytes. It increased insulin-independent glucose uptake in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and insulin-dependent glucose uptake in L6 cells. The glucose transporter-1 (GLUT1) protein was induced in 3T3-L1 cells, and the GLUT4 protein was induced in L6 cells by F100. Mechanism study indicated that F100 induced GSK-3β phosphorylation, which was comparable with that induced by insulin. Additionally, the transcriptional activity of NF-κB was inhibited by F100. In RAW 264.7 macrophages, mRNA expression of NF-κB target genes (TNFα and MCP-1) was suppressed by F100. In KK.Cg-Ay/+ mice, F100 decreased fasting insulin and blood glucose and improved insulin tolerance significantly. We conclude that the F100 may be a bioactive component in the SLH plant. It promotes glucose metabolism in vitro and in vivo. Inhibition of GSK-3β and NF-κB may be the potential mechanism.

Keywords: glycogen synthase kinase-3β, tumor necrosis factor-α, monocyte chemotactic protein-1, nuclear factor-κB, KK-Ay mice, insulin resistance

type 2 diabetes is one of the major obesity-associated morbidities, and the number of diabetes patients has reached 17.5 million in the US population (1). Insulin resistance is the pathogenic hallmark of type 2 diabetes and has many adverse effects on health. It increases the risk of hyperglycemia, cardiovascular disease, stroke, and hypertension. More and more diabetic patients use dietary supplements to facilitate the conventional treatment of insulin resistance and hyperglycemia. Among these dietary supplements, botanical extract is a popular component. It is believed that botanicals are able to enhance the therapeutic activity and reduce the side effects of synthetic drugs. However, efficacy and action mechanism of many botanicals have not yet been well understood. In this study, we examined the antidiabetes effects of extracts of a plant, Shilianhua (SLH; Sinocrassula indica Berge).

The plant SLH is a shrub that grows in the southwestern part of China, which includes the Yunnan, Guangxi, and Guizhou provinces. The plant typically blooms from June through August in the Northern Hemisphere. Consumption of SLH in the Pama County of the Guangxi Province in China may be associated with longevity in the local population. Crude extract of SLH is one of the popular botanical products in the control of blood glucose in the US market. Its hypoglycemic activity is patented in the US (patent no. 5,911,993), Japan, and China.

In this study, we isolated the bioactive ingredients of SLH and explored the mechanisms of action of the F100 fraction. Our result suggests that the F100 fraction of SLH exhibited a significant activity in enhancing insulin sensitivity in the KK.Cg-Ay/+ mice. This activity may be related to the inhibition of GSK-3β and NF-κB by F100.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of SLH extract.

The extract of SLH used in this study was prepared from the SLH plant. The plant was collected from Guizhou Province, southwestern China, where SLH has been used as a medicinal herb by the local residents for hundreds of years. The SLH sample was certified by a taxonomist at the Institute of Medicinal Plant Development, a Chinese authority in identification and authentication of traditional Chinese herbs and medicinal plants. The SLH was extracted using 95% ethanol, as described previously (17). Then SLH extract was fractionated using a HPLC system with a C18 column (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) that was eluted with water and 20, 50, and 100% MeOH in a sequence to obtain four subfractions, i.e., F00, F20, F50, and F100. The F100 concentration is calculated on the basis of the weight of the lyophilized extract in the solution. The stock solution was made by dissolving F100 in DMSO.

Animals.

Male KK.Cg-Ay/+ (KK.Cg-Ay mutant) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory and single housed. The mice were fed a defined low-fat diet (D12329; Research Diets) throughout the experiment. Body weight, adiposity, and 4-h fasting glucose were used to assign the mice into two groups. Mice in the two groups had identical body weight and fat content before the F100 treatment. The fat content was measured with quantitative nuclear magnetic resonance using a Brucker model mq10 nuclear magnetic resonance analyzer (Milton, ON, Canada). The control group was fed the defined diet, and the F100 group was fed the same diet containing F100 at 0.05% (wt/wt). The diet with F100 supplementation was prepared as a customerized diet by Research Diets. Serum insulin concentration was determined using Ultra Sensitive Mouse Insulin ELISA Kit from Crystal Chem (Downers Grove, IL). Insulin sensitivity was determined using insulin tolerance test, as described previously (5). All procedures were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and use of animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center.

Cells.

The mouse fibroblast 3T3-L1 preadipocytes, rat skeletal myoblast L6, rat hepatoma cell line H4IIE, and RAW 264.7 macrophages were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and maintained in DMEM culture medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 50 mg/l gentamicin in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. For adipogenesis, 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were grown into confluence in a 100-mmol/l plate and then treated with the adipogenic cocktail (5 μg/ml insulin, 0.5 mmol/l isobutylmethylxanthine, and 10 μmol/l dexamethasone) for 4 days. This was followed by incubation in insulin-supplemented medium for an additional 3 days. The normal medium was used on day 7 to maintain the adipocytes. For differentiation of myotubes, L6 cells were placed into six-well or 12-well plates in DMEM with 10% FBS for 24 h. The cells were then maintained in 2% FBS medium (α-MEM) for 6 days to induce differentiation. The medium was changed every 48 h (15).

Glucose consumption and glucose uptake.

Glucose consumption was conducted as described previously (16). In brief, the cells were cultured in 96-well tissue culture plates and treated with F100 and/or insulin (final concentration 100 nmol/l) for 24 h. The glucose concentration in the culture medium was determined by glucose oxidase method. The amount of glucose consumption was calculated by subtracting the glucose from the control (blank well). 2-deoxy-d-[3H]glucose uptake was conducted according to a method described previously (6). In brief, the cells were cultured in 12-well plates and treated with F100 overnight and/or insulin (200 nmol/l) for 20 min. Then the cells were incubated with 2-deoxy-d-glucose (0.1 mmol/l) and 2-deoxy-d-[3H]glucose (1 μCi/ml) for 5 min and solubilized in 0.4 ml of 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate. Radioactivity of 3H-glucose was determined in the whole cell lysate using a Beckman LS6500 scintillation counter.

Quantative RT-PCR.

Real-time quantative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was conducted with total RNA of RAW 264.7 cells that were treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS). The total RNA was extracted with Tri reagent (T9424; Sigma) according to the manufacturer's instructions. qRT-PCR was conducted using ABI 7900HT fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The primer and probe were ordered from Applied Biosystems: TNFα (Mm00443258_m1) and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1; Mm00441242_m1). The mRNA signal was normalized over 18S ribosomal RNA signal. A mean value of triplicates was used for relative mRNA level or calculation of mRNA fold induction.

NF-κB assay.

A NF-κB-responsive luciferase was transfected into RAW 264.7 cells to determine the transcriptional activity of NF-κB. The reporter activity was induced with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 6-h treatment and determined using a 96-well luminometer.

Insulin-signaling assay.

Differentiated 3T3-L1 or L6 cells were treated with insulin for 30 min and harvested for insulin-signaling assay. F100 pretreatment was 1 h. The whole cell lysate was made and analyzed in Western blot, as described elsewhere (6). Antibodies included phospho (p)IRS-1 Tyr632 (sc-17196; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), pIRS-1 Ser307 (07-247; Upstate Biotechnology), pAkt Thr308 (9275; Cell Signaling Technology), Akt (sc-8312; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), pGSK-3β Ser9 (sc-11757-R; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), GSK-3 (sc-7291; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), glucose transporter (GLUT)1 (ab14683-100; Abcam), GLUT4 (ab654-250; Abcam), β-actin (ab6276; Abcam), and Tubulin (ab7291; Abcam). ImageJ 1.37V was used to quantify the Western blot signals.

Statistical analysis.

In this study, all of the in vitro experiments were conducted at least three times with consistent results. In the bar figures, a mean value and standard error of multiple data points or samples were used to represent the final result. Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA was used in statistical analysis of the data, with significance at P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

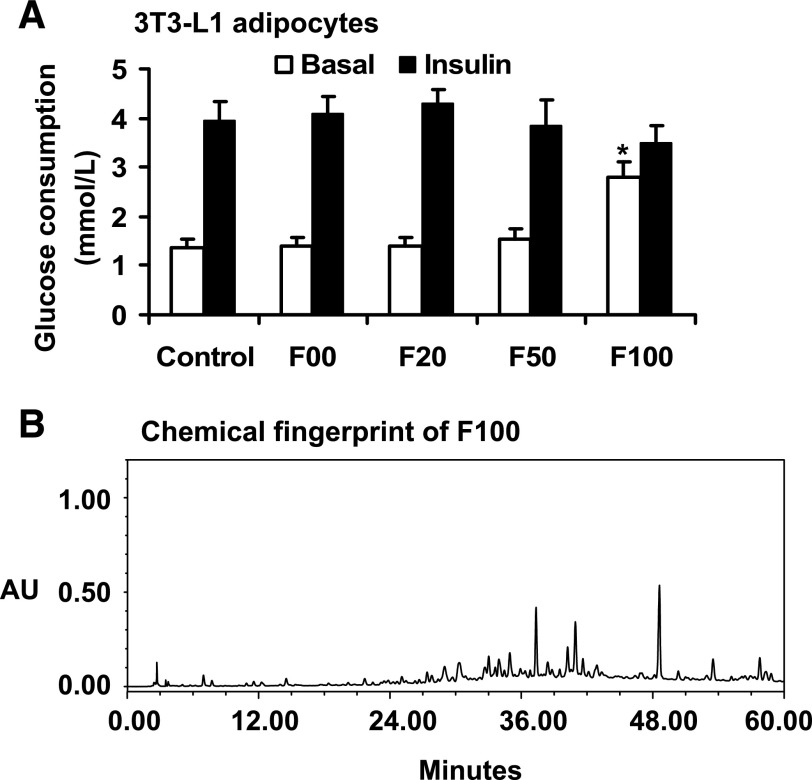

F100 increased glucose consumption in 3T3-L1 adipocytes in the absence of insulin.

To investigate metabolic activity of SLH, we examined four extracts of SLH in the regulation of glucose consumption in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. After 24-h treatment with the extracts, the cells exhibited increased glucose consumption by 102% (P < 0.05) in the presence of F100 (Fig. 1A). The induction was observed in the absence of insulin. The other three SLH fractions (F00, F20, and F50) exhibited no activities in the same assay (Fig. 1A). Insulin also induced glucose consumption in this system. Insulin-induced glucose consumption was not changed by F100 (Fig. 1A). The data suggest that F100 can act in an insulin- independent manner to stimulate glucose utilization. F100 may use the insulin-signaling pathway to enhance the glucose consumption. The chromatographic fingerprints were determined using HPLC. The result is presented in Fig. 1B.

Fig. 1.

Effects of Shilianhua (Sinocrassula indica Berge) subfractions on glucose consumption in vitro. A: F100 enhanced glucose consumption significantly in the absence of insulin in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. B: chromatographic fingerprints of F100 developed with HPLC-UV. The HPLC conditions included the use of Agilent SB-C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm), a mobile phase consisting of acetonitrile and 0.2% phosphoric acid in water and running in gradient elution of 0–20 min at 10–20% acetonitrile and 20–60 min at 44% acetonitrile, dual detection wavelengths of 205 and 254 nm, and a flow rate at 1.0 ml/min. Compared with control: *P < 0.05. AU, absorbance units.

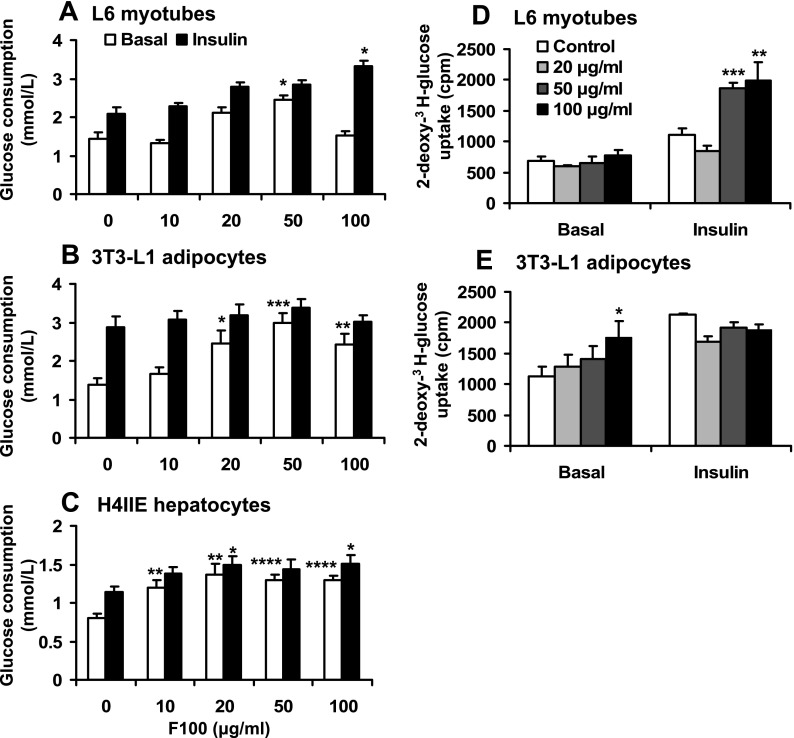

Dose-dependent activity of F100.

The metabolic activity of F100 was investigated using L6 myotubes, 3T3-L1 adipocytes, or H4IIE hepatocytes. The glucose consumption was analyzed at multiple dosages of F100. In these cell lines, F100 induced glucose consumption in a dose-dependent manner ≤50 μg/ml. At 50 μg/ml, the glucose consumption was increased by 69, 115, or 61% in the three types of cells (Fig. 2, A–C). In the presence of insulin, synergy between F100 and insulin was observed in L6 muscle cells but not in 3T3-L1 adipocytes (Fig. 2B). In the hepatocytes, F100 clearly increased glucose consumption in the absence or presence of insulin (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that F100 induces glucose consumption in adipocytes, muscle cells, and hepatocytes in a dose-dependent manner. It may promote insulin activity in cell type-dependent manner (myotubes and hepatocytes).

Fig. 2.

Effects of F100 on glucose metabolism in vitro. Dose effects of F100 on glucose consumption in the L6 myotubes (A), 3T3-L1 adipocytes (B), and H4IIE hepatocytes (C) in the absence and presence of 100 nmol/l insulin (n = 8). Dose effects of F100 on glucose uptake in L6 myotubes (D) and 3T3-L1 adipocytes (E) in the absence and presence of insulin (n = 3). Compared with control (or 0 μg/ml): *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

F100 stimulates glucose uptake.

Glucose uptake was examined using 2-deoxy-[3H]glucose in L6 cells and 3T3-L1 adipocytes. In the absence of insulin, the glucose uptake was not changed by F100 in the L6 myotube cells (Fig. 2D). In the presence of insulin, F100 significantly enhanced insulin activity in the stimulation of glucose uptake in L6 myotubes. Such an effect of F100 was observed at 50–100 μg/ml (Fig. 2D). In the 3T3-L1 adipocytes, F100 significantly enhanced glucose uptake independently of insulin (Fig. 2E). However, in the presence of insulin, F100 did not enhance insulin-induced glucose uptake in adipocytes. These data suggest that F100 promotes glucose uptake in myotubes and adipocytes. Its impact on insulin action may be dependent on cell types.

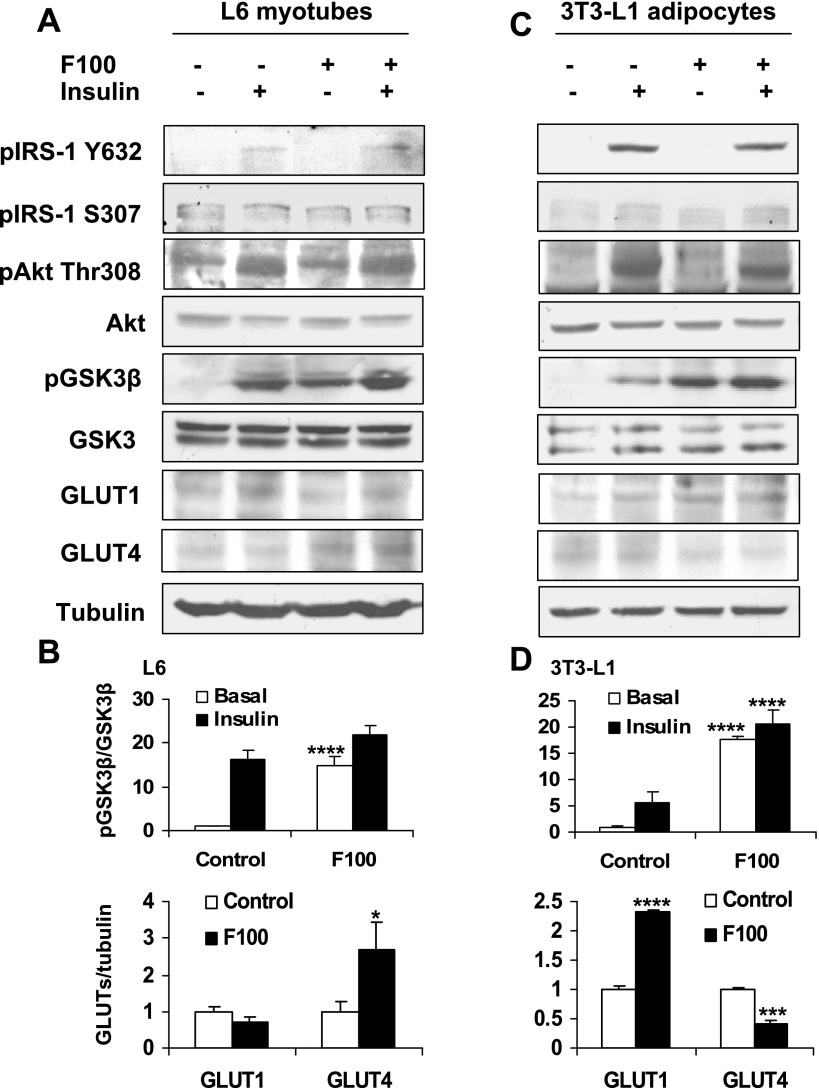

Induction of GSK-3 phosphorylation.

To understand the molecular mechanism of F100 in the regulation of glucose uptake, we examined F100 impact on the insulin-signaling pathway by analysis of major signaling molecules. In the L6 cells and 3T3-L1 adipocytes, F100 induced GSK-3β phosphorylation at Ser9 (Fig. 3). However, IRS-1 phosphorylation (Tyr632, Ser307) and Akt phosphorylation (Thr308) were not induced by F100. In the control, phosphorylation of GSK-3β, Akt, and IRS-1 was induced by insulin. The GSK-3β phosphorylation induced by insulin was also enhanced significantly by F100 in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Since phosphorylation of Ser9 in GSK-3β leads to inhibition of its activity, F100 may inhibit GSK-3β through the phosphorylation. In addition, the protein level of GLUT4 was markedly increased by F100 in the L6 myotubes (Fig. 3, A and B). In the adipocytes, the GLUT1 level was increased and GLUT4 level decreased by F100 (Fig. 3, C and D).

Fig. 3.

Effects of F100 on insulin-signaling pathway. A: L6 myotubes were pretreated with F100 (50 μg/ml) for 8 h. Then the cells were treated with insulin (100 nmol/l) for 30 min. Western blot was performed with the whole cell lysate. B: quantification of the Western blot signal for L6 cells (n = 3). C: effects of F100 on 3T3-L1 adipocytes. D: quantification of the Western blot signal for 3T3-L1 cells (n = 3). Compared with control: *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. pIRS-1, phosphorylated insulin receptor substrate-1; GLUT1 and -4, glucose transporter-1 and -4, respectively.

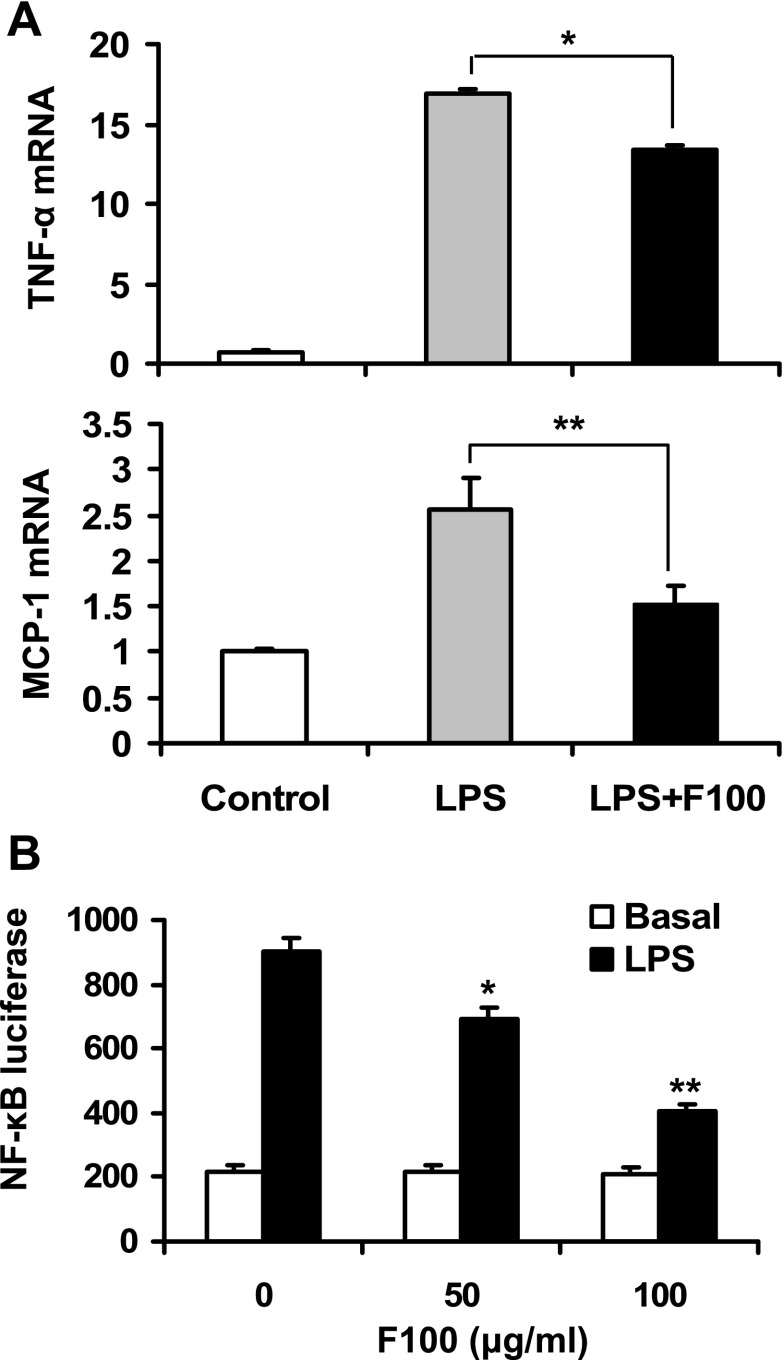

Inhibition of NF-κB and inflammatory cytokines by F100.

Inflammation is involved in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance. Inhibition of inflammation pathways is able to protect cells or mice from insulin resistance. The GSK-3β activity is required for the transcriptional activity of NF-κB (7, 8, 11). Inhibition of GSK-3β may lead to suppression of NF-κB. To test this possibility, we examined F100 in the regulation of inflammation response. The NF-κB target genes (TNFα and MCP-1) were induced by LPS treatment in the mouse macrophage cell line (RAW 264.7). The mRNA expression was significantly inhibited by F100 (Fig. 4A), suggesting inhibition of NF-κB. To confirm the inhibition, transcription activity of NF-κB was examined using a luciferase reporter in a transient transfection assay. F100 significantly inhibited the NF-κB activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4B). The result suggests that F100 may inhibit inflammation through targeting the transcription factor NF-κB.

Fig. 4.

Effects of F100 on inflammation. A: RAW 264.7 macrophages were pretreated with 50 μg/ml F100 for 1 h and followed by lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 1 ug/ml) treatment for 6 h. Quantitative RT-PCR was conducted to examine mRNA expression of TNFα and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1; n = 3). B: luciferase reporter controlled by NF-κB response element was transfected into RAW 264.7 cells. The reporter assay was conducted after F100 and LPS treatment (n = 3). Compared with control (0 μg/ml) or as indicated: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

F100 improved insulin sensitivity in KK.Cg-Ay/+ mice.

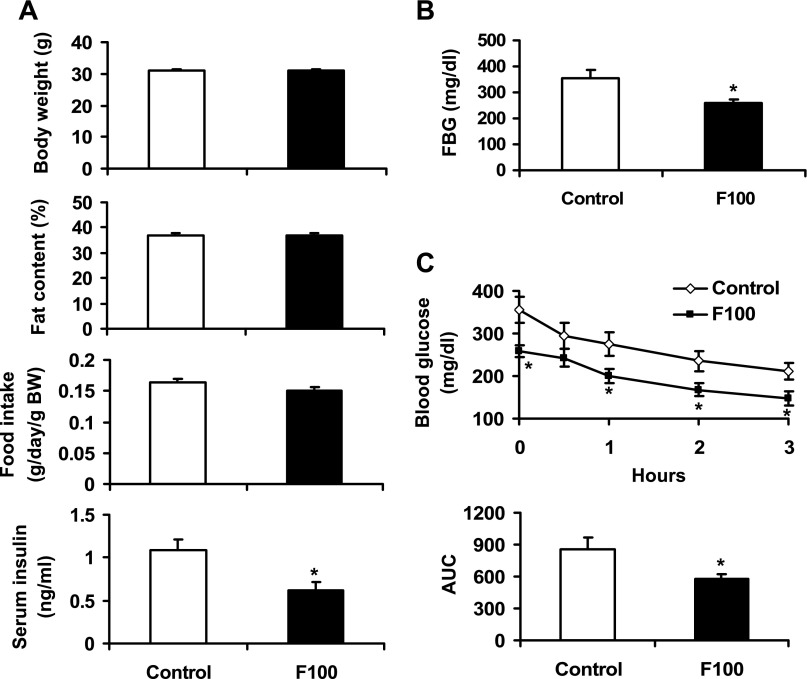

F100 was administrated to diabetic KK.Cg-Ay/+ mice through dietary supplementation at 0.05% wt/wt in the low-fat diet. This dosage of F100 was chosen to avoid toxicity according to preliminary study. At 0.05% wt/wt in diet, F100 did not exhibit any toxicity in mice. After 8-wk treatment, no significant change was observed in body weight, fat content, or food intake in the mice. The fasting insulin and fasting blood glucose (FBG) were reduced by 43 and 27%, respectively, with F100 treatment (P < 0.05; Fig. 5, A and B). In insulin tolerance test, the F100 group exhibited a much lower glucose curve than the control group (Fig. 5C). The area under the curve was reduced by 33% in the F100 group (P < 0.05; Fig. 5C). These data suggest that F100 is able to improve insulin action in the diabetic KK.Cg-Ay/+ mice.

Fig. 5.

Effects of F100 in the KK.Cg-Ay/+ diabetic mice. A: effects of F100 on body weight, fat content, food intake, and serum insulin of KK.Cg-Ay/+ mice (n = 9). B: effect of F100 on fasting blood glucose (FBG) of the mice. C: effects of F100 on insulin tolerance of the mice (n = 9). AUC, area under the curve in the insulin tolerance test. Compared with control: *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

SLH is one of the major botanical dietary supplements for lowering blood glucose. However, the action mechanism of SLH is not clear in the regulation of glucose metabolism. In the present study, we found that the SLH fraction, F100, was able to regulate glucose metabolism in cellular models. Our data suggest that F100 acts through increasing glucose utilization in myotubes, adipocytes, and hepatocytes. This activity was associated with the enhancement of glucose uptake in the myotubes and adipocytes. In L6 myotubes, F100 induced both glucose consumption and glucose uptake in the presence of insulin, suggesting that F100 enhances insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle cells. In 3T3-L1 adipocytes, F100 stimulated glucose consumption and glucose uptake in the absence of insulin, suggesting that F100 has insulin-independent activity in the regulation of glucose metabolism. The increase in glucose uptake may contribute to the glucose consumption in adipocytes.

F100 exhibited different activities in the L6 myotubes and 3T3-L1 adipocytes. In L6 myotubes, the major effect of F100 was to promote insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and glucose consumption. F100 had weak activity in the absence of insulin, although it enhanced glucose consumption at 50 μg/ml without insulin. Such an effect disappeared at 100 μg/ml. In contrast to that in L6 cells, F100 stimulated glucose metabolism only in the absence of insulin in 3T3-L1 cells. The discrepancy may be related to regulation of GLUTs by F100. F100 induced GLUT4 protein without an effect on GLUT1 in the L6 cells. In the 3T3-L1 adipocytes, F100 increased the GLUT1 protein and decreased GLUT4. The increase in GLUT1 may compensate for the loss of GLUT4 in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Thus, the insulin-induced glucose uptake was not reduced by F100 in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. These cell type-specific effects may explain the F100 metabolic activities in L6 myotubes and 3T3-L1 adipocytes.

In this study, F100 exhibited a stronger activity in the induction of glucose consumption in both muscle cells and adipocytes. The effect was observed for F100 at 20 and 50 μg/ml in the absence of insulin. In the glucose uptake assay, the F100 activity was observed only in the adipocytes, not in the muscle cells. The discrepancy may be due to the difference in sensitivity of the two tests. The glucose consumption assay detects the accumulative amount of glucose consumed by cells over 24 h. In the test, the glucose concentration is 25 mmol/l in the culture medium. In contrast, glucose uptake assay detects the amount of glucose uptake in 5 min. The assay was conducted in PBS with low concentration of glucose (0.1 mmol/l deoxyglucose). It is likely that F100 induced a low-grade glucose uptake in the presence of high concentration of glucose. Such an effect can be detected in the glucose consumption assay easily but not in the glucose uptake assay with the low concentration of glucose.

Our in vivo study revealed that F100 was able to improve FBG and insulin sensitivity in KK.Cg-Ay/+ mice. A recent report showed that the methanol extract of SLH did not reduce FBG in KK.Cg-Ay/+ mice (18). Instead, the extract was shown to reduce postprandial blood glucose by inhibiting gastric emptying and reducing activities of aminopeptidase N and aldose reductase in intestines (12, 18). In this study, F100, a nonpolarity subfraction of SLH, was used in KK.Cg-Ay/+ mice. F100 is considered to contain the main bioactive components of SLH, such as saponins and flavonoids, which are water insoluble. Thus, we observed that F100, the bioactive component-enriched fraction of SLH, had hypoglycemic and insulin-sensitizing effects in vivo.

In the molecular mechanism of F100 action, GSK-3β may be a target of F100 in insulin sensitization. GSK-3 inhibits insulin signaling by suppression of IRS-1 function through serine phosphorylation (9, 10). GSK-3 inhibitors were reported to improve insulin sensitivity in cellular and animal models (2, 7, 13, 14). The inhibition of GSK-3 leads to an increase in glycogen synthesis, which promotes insulin sensitivity. Activation of GSK-3 leads to reduction in glycogen synthesis and decrease in insulin sensitivity. The association of glycogen metabolism and insulin sensitivity supports the role of GSK-3 in the regulation of insulin action in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue. In response to insulin, the enzyme activity of GSK-3 is inhibited through Akt-mediated phosphorylation. Our data suggest that this inhibitory mechanism may be used by F100 to stimulate glucose uptake in the cellular models and increase insulin sensitivity in KK.Cg-Ay/+ mice.

Inhibition of inflammation may also contribute to the insulin sensitization by F100. We found that F100 was a powerful NF-κB inhibitor. In response to F100, the LPS-induced cytokine (TNFα and MCP-1) expression was reduced in RAW 264.7 macrophages. The inhibition was associated with suppression of transcriptional activity of NF-κB, which is the transcriptional activator for both cytokines. In the reporter assay, the NF-κB activity was significantly reduced in the presence of F100. GSK-3β function is required for the NF-κB activity (7, 8, 11). The NF-κB inhibition may be a result of GSK-3β suppression by F100. Our early studies showed that IKK/NF-κB led to insulin resistance in the signaling pathway of TNFα (3, 4).

In summary, we conclude that F100 is a bioactive component in SLH and able to regulate glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity in mice and in cells. The data suggest that the activity of F100 may be related to the inhibition of GSK-3β. The inhibition may improve insulin signaling in cell. Indirectly, F100 may protect insulin sensitivity by inhibition of NF-κB activity.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P50-AT-02776-030002 and grants from National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine and the Office of Dietary Supplements to J. Ye.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2007. Diabetes Care 31: 596–615, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen X, McMahon EG, Gulve EA. Stimulatory effect of lithium on glucose transport in rat adipocytes is not mediated by elevation of IP1. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 275: E272–E277, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao Z, He Q, Peng B, Chiao PJ, Ye J. Regulation of nuclear translocation of HDAC3 by IkappaBalpha is required for tumor necrosis factor inhibition of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma function. J Biol Chem 281: 4540–4547, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao Z, Hwang D, Bataille F, Lefevre M, York D, Quon MJ, Ye J. Serine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate 1 by inhibitor kappa B kinase complex. J Biol Chem 277: 48115–48121, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao Z, Wang Z, Zhang X, Butler AA, Zuberi A, Gawronska-Kozak B, Lefevre M, York D, Ravussin E, Berthoud HR, McGuinness O, Cefalu WT, Ye J. Inactivation of PKCθ leads to increased susceptibility to obesity and dietary insulin resistance in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292: E84–E91, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao Z, Zhang X, Zuberi A, Hwang D, Quon MJ, Lefevre M, Ye J. Inhibition of insulin sensitivity by free fatty acids requires activation of multiple serine kinases in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mol Endocrinol 18: 2024–2034, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henriksen EJ, Kinnick TR, Teachey MK, O'Keefe MP, Ring D, Johnson KW, Harrison SD. Modulation of muscle insulin resistance by selective inhibition of GSK-3 in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 284: E892–E900, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoeflich KP, Luo J, Rubie EA, Tsao MS, Jin O, Woodgett JR. Requirement for glycogen synthase kinase-3beta in cell survival and NF-kappaB activation. Nature 406: 86–90, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ilouz R, Kowalsman N, Eisenstein M, Eldar-Finkelman H. Identification of novel glycogen synthase kinase-3beta substrate-interacting residues suggests a common mechanism for substrate recognition. J Biol Chem 281: 30621–30630, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liberman Z, Eldar-Finkelman H. Serine 332 phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 by glycogen synthase kinase-3 attenuates insulin signaling. J Biol Chem 280: 4422–4428, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin M, Rehani K, Jope RS, Michalek SM. Toll-like receptor-mediated cytokine production is differentially regulated by glycogen synthase kinase 3. Nat Immunol 6: 777–784, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morikawa T, Xie H, Wang T, Matsuda H, Yoshikawa M. Bioactive constituents from Chinese natural medicines. XXXII. aminopeptidase N and aldose reductase inhibitors from Sinocrassula indica: structures of sinocrassosides B(4), B(5), C(1), and D(1)-D(3). Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 56: 1438–1444, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nikoulina SE, Ciaraldi TP, Mudaliar S, Carter L, Johnson K, Henry RR. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3 improves insulin action and glucose metabolism in human skeletal muscle. Diabetes 51: 2190–2198, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orena SJ, Torchia AJ, Garofalo RS. Inhibition of glycogen-synthase kinase 3 stimulates glycogen synthase and glucose transport by distinct mechanisms in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem 275: 15765–15772, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yin J, Gao Z, Liu D, Liu Z, Ye J. Berberine improves glucose metabolism through induction of glycolysis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 294: E148–E156, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin J, Hu R, Chen M, Tang J, Li F, Yang Y, Chen J. Effects of berberine on glucose metabolism in vitro. Metabolism 51: 1439–1443, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin J, Zuberi A, Gao Z, Liu D, Liu Z, Cefalu WT, Ye J. Effect of Shilianhua extract and its fractions on body weight of obese mice. Metabolism 57: S47–S51, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshikawa M, Wang T, Morikawa T, Xie H, Matsuda H. Bioactive constituents from chinese natural medicines. XXIV. Hypoglycemic effects of Sinocrassula indica in sugar-loaded rats and genetically diabetic KK-A(y) mice and structures of new acylated flavonol glycosides, sinocrassosides A(1), A(2), B(1), and B(2). Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 55: 1308–1315, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]