Abstract

Expression of nuclear angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) receptors in rat kidney provides further support for the concept of an intracellular renin-angiotensin system. Thus we examined the cellular distribution of renal ANG II receptors in sheep to determine the existence and functional roles of intracellular ANG receptors in higher order species. Receptor binding was performed using the nonselective ANG II antagonist 125I-[Sar1,Thr8]-ANG II (125I-sarthran) with the AT1 antagonist losartan (LOS) or the AT2 antagonist PD123319 (PD) in isolated nuclei (NUC) and plasma membrane (PM) fractions obtained by differential centrifugation or density gradient separation. In both fetal and adult sheep kidney, PD competed for the majority of cortical NUC (≥70%) and PM (≥80%) sites while LOS competition predominated in medullary NUC (≥75%) and PM (≥70%). Immunodetection with an AT2 antibody revealed a single ∼42-kDa band in both NUC and PM extracts, suggesting a mature molecular form of the NUC receptor. Autoradiography for receptor subtypes localized AT2 in the tubulointerstitium, AT1 in the medulla and vasa recta, and both AT1 and AT2 in glomeruli. Loading of NUC with the fluorescent nitric oxide (NO) detector DAF showed increased NO production with ANG II (1 nM), which was abolished by PD and N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester, but not LOS. Our studies demonstrate ANG II receptor subtypes are differentially expressed in ovine kidney, while nuclear AT2 receptors are functionally linked to NO production. These findings provide further evidence of a functional intracellular renin-angiotensin system within the kidney, which may represent a therapeutic target for the regulation of blood pressure.

Keywords: nucleus, kidney, intracellular renin angiotensin system

ang ii, the major bioactive component of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) functions to induce a multitude of events that contribute to the regulation of blood pressure, body fluid volume, and electrolyte balance. The actions of ANG II include vasoconstriction, stimulation of tubular sodium reabsorption and aldosterone release, oxidative stress, and inflammation. The majority of these actions are thought to be mediated through the AT1 receptor subtype. AT1 receptor antagonists (ARBs) are now one of the major classes of blood pressure-lowering therapies associated with target organ protection. However, ANG II may also interact with the G protein-coupled AT2 receptor, which generally opposes or attenuates the actions of the ANG II-AT1 axis (6, 7). The role of the AT2 receptor may be particularly relevant during ARB therapy, as the circulating levels of ANG II markedly increase due to the disinhibition of ANG II feedback on renin release.

The classic view by which ANG II exerts its cellular actions is by binding to receptors embedded in the plasma membrane, which induces a conformational change in the receptor and an ensuing cascade of downstream signaling events that may include activation of various kinases and phosphatases (12, 15, 59). This tenet for peptide hormones and their G protein-coupled receptors has undergone a revision as a number of studies have demonstrated a role for intracellular or “intracrine” ANG II (3, 4, 11, 13, 27–29, 64). Similarly, the localization of intracellular ANG II has been reported in several tissues, including heart and kidney (31, 33, 41, 60–61). Accordingly, recent studies in the rat have demonstrated that ANG II receptors in the kidney can be associated with the cell nucleus as well as the plasma membrane (39, 40, 48). Indeed, we reported the expression of nuclear AT1 receptors in the medullary and cortical regions of the mRen2.Lewis hypertensive rat (48). However, the characterization of intracellular ANG II receptors in species more closely related to humans is important, particularly if an intracellular angiotensin system is relevant to cardiovascular disease. Moreover, the functional role of these intracellular receptors has yet to be established. Therefore, the objective of the current studies was to determine the expression and functional significance of intracellular ANG II receptor subtypes in the sheep kidney, an animal model in which renal development and nephrogenesis closely parallel that of humans (18).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Tissues were obtained from 14 adult (8 males, 6 females; 1.5 yr of age) and 6 fetal (3 males, 3 females; 139 days gestation; term = 145–150 days) mixed-breed sheep housed in the Wake Forest University School of Medicine animal facility. Animals were fed a normal diet with access to water ad libitum, and maintained on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle. Kidneys were obtained from animals anesthetized with ketamine and halothane, dissected in saline on ice into renal cortex and medulla, then immediately frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C or processed at 4°C for density gradient separation (see below). All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Wake Forest University School of Medicine.

Preparation of nuclei and plasma membrane by differential centrifugation.

Frozen tissue (∼500 mg) was homogenized in buffer containing 25 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 20 mM Tricine-KOH, and 25 mM sucrose (pH 7.8) utilizing a Polytron Ultra-Turrax T25 Basic (setting 4), followed by a Barnant Mixer (Series 10, setting 3). The homogenate was passed through a 100-μm mesh filter and centrifuged twice at 1,000 g (4°C) for 10 min to obtain the nuclear fraction. The resultant supernatant was centrifuged at 25,000 g for 20 min (4°C), yielding the plasma membrane fraction.

Preparation of nuclei by OptiPrep density gradient separation.

Apart from the crude preparation of nuclei obtained by differential centrifugation, an additional pure fraction of cortical and medullary nuclei was obtained by an isosmotic density gradient separation. As described above, renal cortices and medullas were homogenized and centrifuged at 1,000 g for 10 min (4°C), the pellet was resuspended in 20% OptiPrep solution (Accurate Chemical and Scientific, Westbury, NY) according to manufacturer's recommendations and layered on a discontinuous density gradient column. The columns, consisting of descending layers of 10, 20, 25, 30, and 35% OptiPrep solution to form the gradient, were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 20 min (4°C). The enriched fraction of isolated nuclei was recovered at the 30–35% layer interface (48).

ANG II receptor radioligand binding.

Characterization of angiotensin receptor binding was performed as previously described (9, 48). Briefly, isolated nuclei and plasma membrane, as prepared above, were suspended in HEPES buffer supplemented with 0.2% BSA (pH 7.4) and coincubated with the radioligand 125I-[Sar1,Thr8]-ANG II (125I-sarthran) in the presence of losartan (the AT1-receptor antagonist), PD123319 (the AT2-receptor antagonist), or nonlabeled sarthran. The final concentrations of all receptor antagonists used were 10 μM. Sarthran was radiolabeled with Na125I using the chloramine T method and purified by HPLC as described (9).

These initial binding assays were carried out in fresh renal cortices and medullas. Frozen tissue paired to fresh tissue samples from each animal were similarly used in radioligand binding assays to assess the impact of freezing on receptor binding. After an identical receptor subtype profile between fresh and frozen tissues (data not shown) was established, all subsequent experiments were conducted using tissue stored at −80°C.

Western blotting and immunodetection.

Samples of renal homogenate were retained and assayed for protein analysis and Western blotting. Cellular fractions were suspended in PBS and added to Laemmli buffer containing mercaptoethanol. Proteins were separated on 10% SDS polyacrylamide gels for 1 h at 120 V in Tris-glycine buffer and electrophoretically transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Immunodetection was performed on blots blocked for 1 h with 5% dry milk (Bio-Rad) and Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween, then probed with antibodies against annexin II (1:5,000; BD Transduction Laboratories, San Diego, Ca), nuclear pore complex proteins (1:2,500; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), AT1 (1:5,000; Alpha Diagnostics, San Antonio, TX), AT2 (1:500; Life Span Biosciences, Seattle, WA), endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS; 1:500; Upstate Cell Signaling Solutions, Lake Placid, NY), and soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC; 1:200; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). Reactive proteins were detected with Pierce Super Signal West Pico Chemiluminescent substrates and exposed to Amersham Hyperfilm enhanced chemiluminescence (Piscataway, NJ).

Receptor autoradiography.

A piece of kidney tissue taken at necropsy was frozen on dry ice, covered with Tissue Tek-Optimum Cutting Temperature (OCT) Embedding medium (Ft. Washington, PA) and stored at −80°C until use. Sections (14 μm) of kidney were treated with 5 μM receptor antagonists and incubated with 0.2 nM 125I-sarthran. Nonspecific labeling was obtained by preincubation with unlabeled sarthran. Tissue slides were exposed against Kodak Biomax MR X-ray film, and quantification of autoradiograms was performed using an MCID image-analysis system (Micro Computer Imaging Device, Imaging Research, Ontario, Canada).

Measurement of nitric oxide production.

Isolated cortical nuclei from adult sheep kidney, prepared by OptiPrep density gradient separation as described above, were preincubated with the fluorescence dye 4-amino-5-methylamino-2′,7′-difluorofluorescein diacetate (DAF; 5 μg/ml; Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) in buffer containing 140 mM NaCl, 14 mM glucose, 4.7 mM KCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1.8 mM MgSO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, and 100 μM l-arginine (pH 7.4) for 30 min at 37°C. Nuclei were washed twice in HEPES buffer to remove any unbound dye, then incubated with 1 nM ANG II in the presence of losartan (the AT1-receptor antagonist), PD123319 (the AT2-receptor antagonist), the NOS inhibitor N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME; 1 mM) or buffer alone. Increases in DAF fluorescence, indicative of nitric oxide (NO) production, were measured using a SpectraMax M2e microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) at wavelengths of 488 (excitation) and 510 nm (emission). DAF has a detection limit of 5 nM and does not react with other stable oxidized forms of NO, such as NO2, or reactive oxygen species (36).

Statistical analysis.

Data are represented as means ± SE. A paired Student's t-test, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison post hoc, and nonlinear regression were performed using GraphPad Prism 4.0 plotting and statistical software.

RESULTS

Determination of ANG II receptor subtypes.

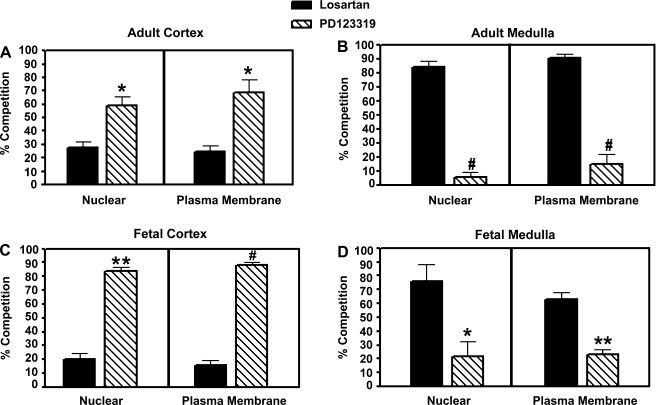

The relative proportions of ANG II receptor subtypes were determined by use of specific ANG II receptor antagonists. Both nuclei and plasma membrane fractions isolated from the cortex and medulla of the sheep kidney by differential centrifugation exhibit specific binding with the nonselective ANG II receptor antagonist 125I-sarthran. As shown in Fig. 1A, PD123319, the selective AT2-receptor antagonist, competes for the majority of cortical ANG II receptors in both the nuclear and plasma membrane fractions of the adult kidney. Conversely, in the medulla, competition by the AT1 antagonist losartan resulted in ∼90% displacement of 125I-sarthran binding in both nuclei and plasma membrane fractions (Fig. 1B). To determine whether the distribution of ANG II receptor subtypes in adult ovine kidney (1.5 yr of age; approximately equivalent to an 18- to 20-yr-old human) differed significantly from that during fetal development, when AT2 expression is thought to be greatest, the expression of ANG II receptors in fetal kidney (139-day gestation) was examined. Similar to the adult, competition by PD123319 represented >85% of ANG II receptor binding in the nuclei and plasma membranes of the fetal kidney cortex (Fig. 1C), while losartan competition in the fetal medulla was 76 and 63% in the nuclei and plasma membranes, respectively (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of ovine renal angiotensin receptor subtypes in isolated nuclei and plasma membrane fractions of adult (1.5 yr of age; n = 8) cortex (A) and medulla (B) and fetal (139 days' gestation; n = 4) cortex (C) and medulla (D). Cellular fractions were derived by differential centrifugation of homogenates from equivalent wet tissue weight of fetal and adult cortices and medullas. Competition binding was carried out using 0.5 nM 125I-sarthran and receptor antagonists at a final concentration of 10 μM. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.01 vs. losartan. **P < 0.001 vs. losartan. #P < 0.0001 vs. losartan.

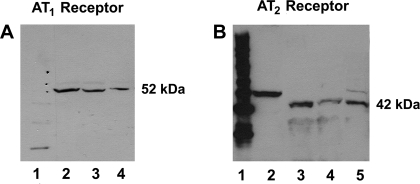

To further illustrate the expression of intracellular ANG II receptors within the adult ovine kidney, immunoblots of isolated cortical nuclei were probed with an antibody directed against the AT1 subtype and revealed a single 52-kDa band (Fig. 2A). Similarly, immunoblots of both cortical nuclei and plasma membranes were probed with an AT2 antibody, which yielded a single band at ∼42 kDa (Fig. 2B). Homogenates of sheep adrenal tissue, known to express a high density of AT2 receptors, were used as a positive control for AT2 immunoreactivity.

Fig. 2.

Intracellular ANG II receptor subtype immunoreactivity of adult kidney cortex. A: ANG II type 1 (AT1) receptor immunoreactivity using rabbit anti-human polyclonal antibody (1:5,000) and anti-rabbit IgG (1:5,000). The full-length gel represents molecular weight marker (lane 1) and kidney cortex nuclear fraction from 3 distinct animals (lanes 2–4). B: AT2 receptor immunoreactivity utilizing rabbit anti-human polyclonal antibody (1:500) and anti-rabbit IgG (1:3,000). The full-length gel represents molecular weight marker (lane 1), adrenal plasma membrane (lane 2), kidney cortex nuclear fraction (lane 3), kidney cortex plasma membrane (lane 4), and adrenal nuclear fraction (lane 5). Differences in molecular weights between renal and adrenal AT2 immunoreactivity may reflect varying degrees of glycosylation of this protein between tissue types.

Receptor density and binding affinity.

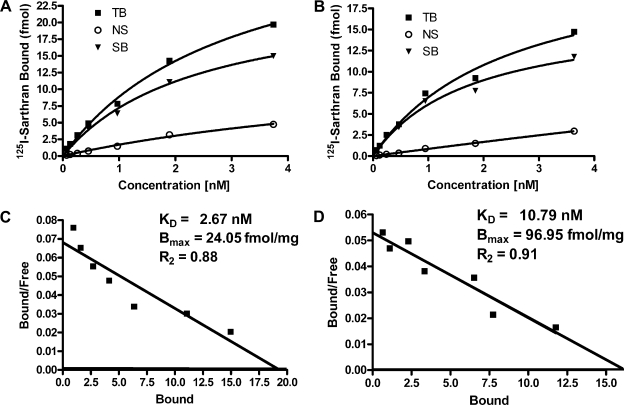

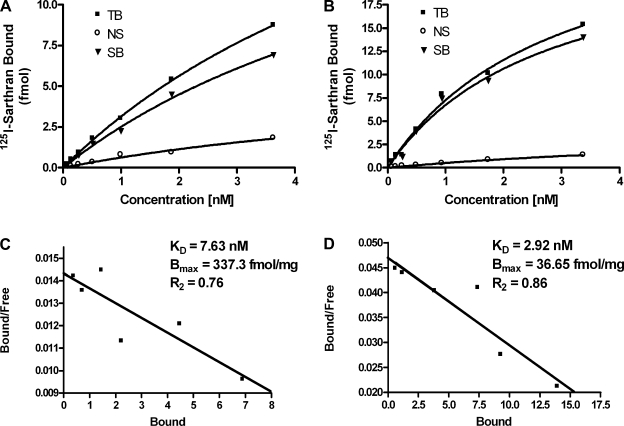

As indicated in Table 1, the density of ANG II receptors (Bmax) in the plasma membranes of the cortex was significantly greater than that of the nuclear membranes (n = 4; P < 0.05); albeit the cortical nuclear receptors demonstrate a higher binding affinity (KD) than those of the plasma membranes (P < 0.05). Conversely, the medullary nuclei possess a 10-fold greater density of receptors than found in the medullary plasma membranes (n = 4; P < 0.001), while the affinity of these receptors (KD) was lower than that of the plasma membrane receptors in this same region (P < 0.05). As demonstrated in the representative saturation binding curves and Scatchard analysis for the renal cortex (Fig. 3) and the renal medulla (Fig. 4), linear plots were obtained for both nuclear and plasma membrane fractions, indicating a single population of binding sites.

Table 1.

Renal ANG II receptor density and binding affinity

| Kidney Region | KD, nM | Bmax, fmol/mg | R2 | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortex | ||||

| Nucleus | 2.67 | 24.05 | 0.88 | 4 |

| Plasma membrane | 10.79 | 96.95 | 0.91 | 4 |

| Medulla | ||||

| Nucleus | 7.63 | 337.30 | 0.76 | 4 |

| Plasma membrane | 2.92 | 36.65 | 0.87 | 4 |

Saturation binding and Scatchard analysis were performed on isolated nuclei and plasma membranes from the renal cortex and medulla using increasing concentrations of the specific angiotensin receptor antagonist 125I-[Sar1, Thr8]-ANG II (sarthran). Receptor density and affinity are defined as Bmax and KD, respectively. Nonspecific binding was obtained by the addition of 10 μM unlabeled sarthran.

Fig. 3.

Representative saturation binding for ANG II receptors in nuclear (A) and plasma membrane (B) fractions obtained by differential centrifugation of the renal cortex. Scatchard analysis for isolated cortical nuclei (C) and plasma membrane (D) is shown. Saturation binding and Scatchard analysis were performed with increasing concentrations of the specific receptor antagonist 125I-sarthran. Nonspecific binding was determined by use of 10 μM unlabeled sarthran. The receptor density and affinity are defined as Bmax and KD, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Representative saturation binding for ANG II receptors in nuclear (A) and plasma membrane (B) fractions obtained by differential centrifugation of the renal medulla. Scatchard analysis of isolated medullary nuclei (C) and plasma membrane (D) is shown. Saturation binding and Scatchard analysis were performed with increasing concentrations of the specific receptor antagonist 125I-sarthran. Nonspecific binding was determined by use of 10 μM unlabeled sarthran.

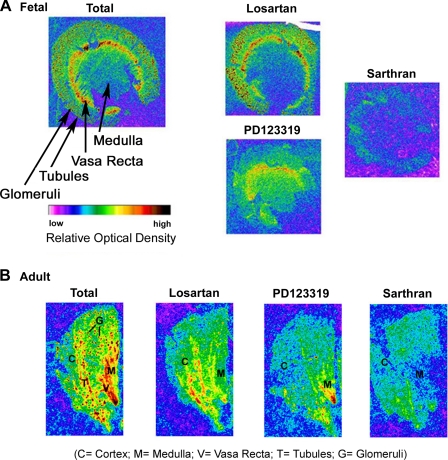

Autoradiographic analysis of ANG II receptor subtypes in sheep kidney.

The distribution of ANG II receptor subtypes, as detected using 125I-sarthran in both fetal (Fig. 5A) and adult (Fig. 5B) sheep kidney, is similar. Autoradiograms show dense binding in the inner medulla and area of the vasa recta, the tubulointerstitial area, and glomeruli. Blockade of AT1 receptors with the antagonist losartan reveals receptors remaining throughout the tubulointerstitial area of the cortex, consistent with the presence of AT2 sites in this region. Binding in the inner medulla and area of the vasa recta is visibly reduced, suggesting predominant localization of AT1 receptors to these regions. Incubation with the AT2 antagonist PD123319 essentially abolishes binding in the tubulointerstitial area of the cortex, although there is evidence of remaining binding in glomeruli. Blockade of AT2 receptors does not abolish binding in the medullary region or area of the vasa recta, the area of dense AT1 receptors as indicated by nuclear/plasma membrane binding assays.

Fig. 5.

Autoradiography of fetal (A) and adult (B) sheep kidney. Frozen-thawed kidney sections were incubated with 5 μM receptor antagonists and probed with 0.2 nM 125I-sarthran. Nonspecific labeling was obtained by preincubation with unlabeled sarthran.

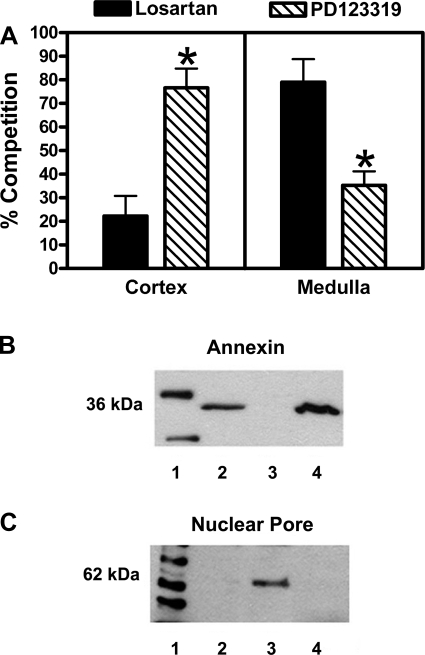

Nuclear ANG II receptor binding.

To ensure the specificity of nuclear ANG II receptor binding, 125I-sarthran binding assays were performed with isolated nuclei derived from OptiPrep density gradients. Receptor binding utilizing isolated nuclei from OptiPrep medium yielded receptor profiles essentially identical to those observed in nuclei from differential centrifugation (Fig. 6A). Hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed on enriched nuclei from the OptiPrep gradient, demonstrating intact nuclei (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Characterization of angiotensin receptor subtypes in isolated renal cortical and medullary nuclei derived by OptiPrep density gradient. A: competition binding was carried out using 0.5 nM 125I-sarthran and receptor antagonists at a final concentration of 10 μM. Values are means ± SE (n = 3; *P = 0.02). B: immunodetection of cortical nuclei and plasma membrane fractions of fetal kidney. Annexin, a plasma membrane-specific cellular marker was used to distinguish nuclear and plasma membrane fractions: molecular weight marker (lane 1), rat kidney cortex plasma membrane (lane 2), sheep kidney cortex nuclear fraction (lane 3), and sheep kidney cortex plasma membrane (lane 4). C: nuclear pore complex protein immunoreactivity: molecular weight marker (lane 1), rat kidney cortex plasma membrane (lane 2), sheep kidney cortex nuclear fraction (lane 3), and sheep kidney cortex plasma membrane (lane 4).

Immunoblot analysis of membrane fractions.

To distinguish nuclear and plasma membrane receptor populations, anti-annexin II, a plasma membrane cellular marker, was employed to confirm the purity of the OptiPrep nuclear preparation. As shown in Fig. 6B, immunoblots revealed a single 36-kDa band for sheep kidney cortical plasma membranes. The nuclear fraction of the sheep kidney showed no immunoreactive band, indicating the absence of any contamination by plasma membrane receptors. Similarly, Fig. 6C demonstrates immunodetection of the nuclear pore complex, as indicated by a single 62-kDa band for cortical nuclei.

ANG II-mediated induction of NO through nuclear ANG receptors.

To assess whether the nuclear AT2 receptors are functional, nuclei were isolated from fresh adult renal cortices by OptiPrep density gradient separation and preincubated with the selective NO fluorescence detector DAF. Stimulation with 1 nM ANG II elicited a significant increase in DAF fluorescence, which was abolished by the AT2-receptor antagonist PD123319 but not by the AT1 antagonist losartan (Fig. 7A). In similar fashion, the ANG II-mediated production of NO was abrogated by the NO synthase inhibitor, l-NAME. Representative tracings of ANG II-stimulated DAF fluorescence and inhibition with antagonists are presented in Fig. 7, B–D.

Fig. 7.

ANG II-mediated production of nitric oxide (NO) through nuclear receptors. Fresh renal cortical nuclei were isolated from adult sheep kidneys by OptiPrep density gradient separation and preincubated with the selective NO fluorescence detector DAF. Values are expressed as % change in mean fluorescence intensity over control (baseline). A: nuclei were stimulated with ANG II (1 nM) in the presence of the AT1 antagonist losartan (1 μM), the AT2 antagonist PD123319 (1 μM), or the nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester(l-NAME; 1 mM). Values are means ± SE; n = 6, *P < 0.05 vs. ANG II. Representative DAF fluorescence tracings over a 5-min time course in the presence of the AT1 antagonist losartan (B), the AT2 antagonist PD123319 (C), or the NOS inhibitor l-NAME (D) following a 2-minute prestimulation with 1 nM ANG II are also shown. Data are expressed as relative fluorescence units.

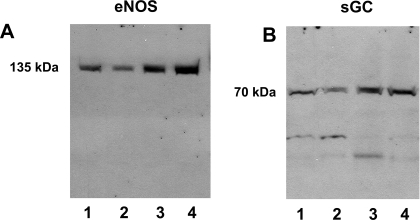

Protein analysis showed the presence of endothelial NOS (eNOS/NOSIII, 135 kDa) (Fig. 8A) as well as soluble guanylate cyclase (70 kDa), the principal NO receptor (Fig. 8B), in full-length immunoblots of isolated cortical nuclei.

Fig. 8.

Immunodetection of endothelial NOS (eNOS) and soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC). Isolated cortical nuclei were probed with antibodies raised against eNOS (A) and sGC (B). In each full-length gel, lanes 1–4 represent samples from 4 distinct animals.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we characterized angiotensin receptor expression in the sheep kidney and demonstrated the expression of both nuclear AT1 and AT2 receptors in fetal and adult kidney, where functional expression of nuclear AT2 receptors in the cortex is linked to the production of NO. As revealed by 125I-sarthran binding and competition with selective ANG II-receptor antagonists, the AT1 is the predominate receptor subtype expressed in the sheep renal medulla, while the renal cortex expresses primarily AT2 receptors. To date, the majority of studies characterizing renal ANG II receptor expression have been conducted using either rat or mouse models, where very little AT2 expression is observed in the kidney at adulthood (6, 7, 39, 40, 48). Indeed, we reported nearly complete competition of 125I-sarthran binding with the AT1 antagonists losartan or candesartan, demonstrating AT1 as the predominant receptor subtype in both the cortex and medulla of the Lewis and mRen2.Lewis rat kidney (48). In contrast, AT2 sites represent the predominant receptor subtype in the large preglomerular vessels and perivascular region of the human (5, 21) and nonhuman primate (17) cortex. AT2 receptor mRNA expression during fetal development in humans parallels that of sheep, in that AT2 receptors are detected early in nephrogenesis and decline abruptly with the end of nephron differentiation (18, 50, 53), although a significant number of AT2 receptors remain postnatally. Thus both sheep and human adult kidneys express significant AT2 receptors, in marked contrast to the rat kidney.

The density of ANG II receptors was significantly greater in the cortical plasma membrane vs. the nuclear fraction; however, medullary nuclei expressed a larger number of receptors than the plasma membranes. The differences in receptor density between the nuclei and plasma membranes of the sheep kidney may reflect internalization and trafficking of the receptors into the cell, and ultimately to the nucleus. It is well established that the AT1 receptor undergoes rapid internalization following binding of extracellular ANG II, which results in trafficking of both the peptide and receptor into intracellular compartments (31, 37). Importantly, the ANG II-AT1 receptor internalization is thought to contribute to the functional effects of AT1 activation (4, 34, 52, 58). Saturation binding and Scatchard analysis indicate the density of ANG II receptors in the medulla, consisting predominantly of AT1, is greater in the nucleus than in the plasma membrane. In this regard, the ligand-induced internalization of the AT1 may contribute to the greater density of intracellular receptors within the nuclei of the renal medulla. However, the density of cortical ANG II receptors, primarily AT2, is greater in the plasma membrane fraction. These observations are not surprising, as the AT2 receptor is not considered to undergo internalization and trafficking. Thus nuclear AT2 receptors within the kidney cortex may entail the direct transport of these receptors to the nucleus. Salomone and colleagues (51) report that a cytosolic pool of AT2 receptors may translocate and fuse to the plasma membrane in tubular epithelial cells following dopamine stimulation. Senbonmatsu and coworkers (54), however, reported colocalization of AT2 with promyelocytic zinc finger protein, which promotes internalization of AT2 receptors into the perinuclear space in Chinese hamster ovary K1 cells. This mechanism may contribute to the population of nuclear AT2 receptors; however, the source(s) from which intracellular AT2 arise remains to be determined. We employed antibodies raised against AT1 and AT2 receptors to further demonstrate the expression of nuclear ANG II receptors. Immunoblots revealed a single 52-kDa band for nuclear AT1 and a ∼42-kDa band in both nuclear and plasma membrane fractions for AT2, suggesting a mature molecular form of both nuclear receptor subtypes. Various molecular forms of the AT2 receptor have been reported, which likely reflect the extent of receptor glycosylation, as well as the epitope of the receptor the antibodies recognize.

Autoradiography using the sarthran radioligand further supports the differential expression of ANG II receptor subtypes within both fetal and adult sheep kidneys and reveals localization of AT1 receptors to the medulla and vasa recta, while AT2 receptors are found predominantly in the tubulointerstitial area, which would include the vasculature, interstitial cells, and tubule components. Glomeruli appear to posses both receptor subtypes. These findings are consistent with those of Butkus et al. (5), who reported AT1 mRNA in the medulla and AT2 mRNA in the glomeruli and interstitium of the mesonephros in fetal lambs up to 131 days' gestation. In the rat, the distribution of AT2 receptors includes proximal and distal tubules, collecting ducts, glomeruli, and blood vessels (43, 45), although at a much lower expression. Moreover, AT2 receptors in human kidney cortex are found predominantly in the large preglomerular vessels (21) and the adventitia of intralobular arteries (63), while both AT1 and AT2 subtypes are found in glomeruli and tubulointerstitial regions (21).

It is well known that ANG II is a powerful vasoconstrictor of both pre- and postglomerular vasculature in the rat (42). However, it has recently been demonstrated by Arima (1) that ANG II causes a much stronger constriction of efferent than afferent isolated microperfused rabbit arterioles, due to NO- and prostaglandin-induced effects on ANG II function in the afferent arterioles. Furthermore, this author reports that activation of AT2 receptors causes endothelium-dependent vasodilation which modulates the vasoconstrictor action of the AT1 receptor (1). These findings may account for the exaggerated vasoconstrictor actions of ANG II under conditions where there is a pathological reduction or impaired function of the AT2, such as occurs in some models of hypertension. Thus the receptor distribution whereby AT2 receptors are preglomerular and AT1, postglomerular provides a rationale for reduced glomerular pressure with ARB treatments, and the effectiveness of ARBs to reduce vascular resistance and increase renal blood flow. Blockade of the AT1 receptor may also increase the availability of circulating ANG II to cause AT2-mediated vasodilation.

Recently, studies have been conducted to characterize the role of plasma membrane AT2 receptors in arterial vasodilation and interaction with the bradykinin/NO/cGMP pathway (7). NO, a potent vasodilator, plays an important role in the maintenance of vascular tone. It is also well established that NO acts as a signaling molecule to modulate neurogenic control of blood pressure (62), baroreflex, and cardiopulmonary transmission in the nucleus of the solitary tract (14), as well as stimulating activation of nuclear transcription factor-κB to mediate effects of cardiac protection (10). We report that ANG II generated significant increases in NO production in fresh isolated, intact renal cortical nuclei. Indeed, blockade of AT2 with PD123319 abolished ANG II-mediated production of NO, while blockade of AT1 had no effect. Several reports suggest a direct link between AT1 receptor blockade and NO release (8, 56); however, these studies were conducted in rodents, where AT1 is the predominant receptor expressed. Our studies demonstrate that the AT2 subtype comprises >85% of ANG II receptors in the ovine kidney cortex. Thus, blockade of the AT1, a small proportion of total ANG II receptors, would likely have a negligible effect on NO production. Alternatively, AT1 receptors on the sheep cortical nuclei may not be linked to NOS activation and NO formation.

In the kidney, NO release may originate from several different NOS isoforms (reviewed in Ref. 30). Both endothelial and tubular epithelial cells express eNOS (NOSIII) (46, 47), and NO production contributes to vascular tone and regulation of sodium reabsorption. Within the cortical nuclear fraction, we demonstrate a dense immunoreactive band for eNOS at ∼135 kDa, indicating that the mature form of the enzyme is present within the nuclear compartment. Similarly, eNOS has been reported in nuclei of brown adipocytes (14), rat hepatocytes (20), and rat glioma cells (35), again demonstrating the functional expression of a nuclear NOS system. Moreover, we detected the presence of the heterodimeric hemoprotein sGC, the principal receptor for NO, which catalyzes the conversion of GTP to the second-messenger molecule cGMP. These findings indicate that the nucleus contains the necessary components for NO signaling through ANG II at the AT2 receptor and are in accordance with those of Siragy and coworkers (57), who report that AT2 inhibits the biosynthesis of renal renin through production of NO and cGMP.

AT1 receptors on isolated nuclei from the liver and kidney are functional and capable of modulating gene expression (16, 39). Indeed, our preliminary data in isolated renal nuclei from both rat (49) and sheep (23) suggest that ANG II stimulates the generation of reactive oxygen species via the AT1 receptor. Moreover, AT1 antagonists invariably increase the circulating levels of ANG II such that the functional actions of ARB treatment may invoke activation of AT2 receptors. Whether nuclear AT2 receptors play a role in influencing gene transcription is yet to be determined. Nonetheless, the role of this receptor is becoming increasingly more important in the mechanisms involved in blood pressure maintenance and protection of the kidneys from renal injury and may represent a significant participation in kidneys of higher mammals.

Indeed, the functional significance of intracellular ANG II, as reviewed by Kumar et al. (37), together with the expression of functional nuclear ANG II receptors presented here, gives rise to the notion that the nucleus may be an important target of the RAS that would influence renal function and renal injury. However, the intracellular source for ANG II to bind to nuclear receptors has yet to be established. While Hammond and colleagues (22) suggest that in proximal tubules ANG II internalization is mediated by megalin, a membrane protein involved in receptor-mediated endocytosis, our preliminary findings suggest that intracellular ANG II may arise from the nucleus itself. We recently demonstrated in isolated nuclei from sheep kidney cortex, immunoreactivity for angiotensinogen, the ANG II precursor, and renin, its processing enzyme (23). Our findings are in agreement with those of Sigmund and colleagues (55), who demonstrate nuclear localization of angiotensinogen in astrocytes as well as an intracellular form of active renin (38). Furthermore, we found significant activity for angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) as well as the homolog ACE2 within isolated sheep nuclei (23). Whether these RAS components are synthesized within the nucleus or are translocated to the nucleus after synthesis remains to be determined; however, their nuclear compartmentalization may provide a direct source for the production of intracellular ANG II and Ang-(1-7). Be that as it may, the precise signaling mechanisms by which ANG II activates intracellular receptors to elicit biological responses must be elucidated to develop therapies more effective at preventing or attenuating ANG II-induced organ damage in renal and cardiovascular diseases by blocking the intracellular or nuclear actions of ANG II.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HD-17644, HD-47584, HL-56973, and HL-51952.

Acknowledgments

The authors especially thank Brian Westwood and Ellen Tomassi for expert technical assistance in these studies and Dr. Sean D. Reid for use of the SpectraMax M2e. H. A. Shaltout is also a faculty member in the Dept. of Pharmacology, School of Pharmacy, University of Alexandria, Alexandria, Egypt.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arima S Role of angiotensin II and endogenous vasodilators in the control of glomerular hemodynamics. Clin Exp Nephrol 7: 172–178, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker KM, Chernin MI, Schreiber T, Sanghi S, Haiderzaidi S, Booz GW, Dostal DE, Kumar R. Evidence of a novel intracrine mechanism in angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Regul Pept 120: 5–13, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker KM, Kumar R. Intracellular angiotensin II induces cell proliferation independent of AT1 receptor. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 291: C995–C1001, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becker BN, Harris RC. A potential mechanism for proximal tubule angiotensin II-mediated sodium flux associated with receptor-mediated endocytosis and arachidonic acid release. Kidney Int 50: S66–S72, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butkus A, Albiston A, Alcorn D, Giles M, McCausland J, Moritz K, Zhuo J, Wintour EM. Ontogeny of angiotensin II receptors, types 1 and 2, in ovine mesonephros and metatnephros. Kidney Int 52: 628–636, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carey RM Angiotensin type-2 receptors and cardiovascular function: are angiotensin type-2 receptors protective? Cur Opin Cardiol 20: 264–269, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carey RM Update on the role of the AT2 receptor. Cur Opin Nephrol Hypertens 14: 67–71, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cervenka L, Horácek V, Vanecková I, Hubácek JA, Oliverio MI, Coffman TM, Navar LG. Essential role of AT1A receptor in the development of 2K1C hypertension. Hypertension 40: 735–741, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chappell MC, Jacobsen DW, Tallant EA. Characterization of angiotensin II receptor subtypes in pancreatic acinar AR42J cells. Peptides 16: 741–747, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen CH, Chuang JH, Liu K, Chan JY. Nitric oxide triggers delayed anesthetic preconditioning-induced cardiac protection via activation of nuclear factor-kappaB and upregulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Shock 30: 241–249, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cook JL, Re R, Alam J, Hart M, Zhang Z. Intracellular angiotensin II fusion protein alters AT1 receptor fusion protein distribution and activates CREB. J Mol Cell Cardiol 36: 75–90, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Gasparo M, Catt KJ, Inagami T, Wright JW, Unger T. International Union of Pharmacology XXIII. The angiotensin II receptors. Pharmacol Rev 52: 415–472, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Mello WC Intracellular angiotensin II regulates the inward calcium current in cardiac myocytes. Hypertension 32: 976–982, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dias AC, Vitela M, Colombari E, Mifflin SW. Nitric oxide modulation of glutamatergic, baroreflex, and cardiopulmonary transmission in the nucleus of the solitary tract. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H256–H262, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Douglas JG, Hopfer U. Novel aspect of angiotensin receptors and signal transduction in the kidney. Annu Rev Physiol 56: 649–669, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eggena P, Zhu JH, Clegg K, Barrett JD. Nuclear angiotensin receptors induce transcription of renin and angiotensinogen mRNA. Hypertension 22: 496–501, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibson RE, Thorpe HH, Cartwright ME, Frank JD, Schorn TW, Bunting PB, Siegl PK. Angiotensin II receptor subtypes in renal cortex of rats and rhesus monkeys. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 261: F512–F518, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gimonet V, Bussieres L, Medjebeur AA, Gasser B, Lelongt B, Laborde K. Nephrogenesis and angiotensin II receptor subtypes gene expression in the fetal lamb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 274: F1062–F1069, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giordano A, Tonello C, Bulbarelli A, Cozzi V, Cinti S, Carruba MO, Nisoli E. Evidence for a functional nitric oxide synthase system in brown adipocyte nucleus. FEBS Lett 514: 135–140, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gobeil F Jr, Zhu T, Brault S, Geha A, Vazquez-Tello A, Fortier A, Barbaz D, Checchin D, Hou X, Nader M, Bkaily G, Gratton JP, Heveker N, Ribeiro-da-Silva A, Peri K, Bard H, Chorvatova A, D'Orléans-Juste P, Goetzl EJ, Chemtob S. Nitric oxide signaling via nuclearized endothelial nitric-oxide synthase modulates expression of the immediate early genes iNOS and mPGES-1. J Biol Chem 281: 16058–16067, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldfarb DA, Diz DI, Tubbs RR, Ferrario CM, Novick AC. Angiotensin II receptor subtypes in the human renal cortex and renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 151: 208–213, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez-Villalobos R, Klassen RB, Allen PL, Navar LG, Hammond TG. Megalin binds and internalizes angiotensin II. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F420–F427, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gwathmey TM, Pendergrass KD, Reid SD, Rose JC, Chappell MC. Evidence that the ACE2-angiotensin-(1-7) pathway counterbalances angiotensin II-induced formation of reactive oxygen species in renal nuclei (Abstract). Hypertension 52: E124–E125, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haithcock D, Jiao H, Cui XL, Hopfer U, Douglas JG. Renal proximal tubular AT2 receptor: signaling and transport. J Am Soc Nephrol 10, Suppl 11: S69–S74, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hakam AC, Siddiqui AH, Hussain T. Renal angiotensin II AT2 receptors promote natriuresis in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F503–F508, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hakam AC, Hussain T. Angiotensin II AT2 receptors inhibit proximal tubular Na+-K+-ATPase activity via a NO/cGMP-dependent pathway. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F1430–F1436, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haller H, Lindschau C, Erdmann B, Quass P, Luft FC. Effects of intracellular angiotensin II in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 79: 765–772, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haller H, Lindschau C, Quass P, Luft FC. Intracellular actions of angiotensin II in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 10, Suppl 11: S75–S78, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harris RC Potential mechanisms and physiologic actions of intracellular angiotensin II. Am J Med Sci 318: 374–379, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herrera M, Garvin JL. Recent advances in the regulation of nitric oxide in the kidney. Hypertension 45: 1062–1067, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunt MK, Ramos SP, Geary KM, Norling LL, Peach MJ, Gomez RA, Carey RM. Colocalization and release of angiotensin and renin in renal cortical cells. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 263: F363–F373, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hunyady L, Catt KJ, Clark AJ, Gaborik Z. Mechanisms and functions of AT1 angiotensin receptor internalization. Regul Pept 91: 29–44, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ingert C, Grima M, Coquard C, Barthelmebs M, Imbs JL. Contribution of angiotensin II internalization to intrarenal angiotensin II levels in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F1003–F1010, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jimenez E, Vinson GP, Montiel M. Angiotensin II binding sites in nuclei from rat liver: partial characterization for the mechanism of Ang II accumulation in nuclei. J Endocrinol 143: 449–453, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klinz FJ, Herberg N, Arnhold S, Addicks K, Bloch W. Phospho-eNOS Ser-1176 is associated with the nucleoli and the Golgi complex in C6 rat glioma cells. Neurosci Lett 421: 224–228, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kojima H, Nakatsubo N, Kikuchi K, Kawahara S, Kirino Y, Nagoshi H, Hirata Y, Nagano T. Detection and imaging of nitric oxide with novel fluorescent indicators: diaminofluoresceins. Anal Chem 70: 2446–2453, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar R, Singh VP, Baker KM. The intracellular renin-angiotensin system: a new paradigm. Trends Endocrinol Metab 18: 208–214, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lavoie JL, Liu X, Bianco RA, Beltz TG, Johnson AK, Sigmund CD. Evidence supporting a functional role for intracellular renin in the brain. Hypertension 47: 461–466, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li XC, Zhuo JL. Intracellular ANG II directly induces in vitro transcription of TGF-β1, MCP-1, and NHE-3 mRNAs in isolated rat renal cortical nuclei via activation of nuclear AT1a receptors. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 294: C1034–C1045, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Licea H, Walters MR, Navar LG. Renal nuclear angiotensin II receptors in normal and hypertensive rats. Acta Physiol Hung 89: 427–438, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mercure C, Ramla D, Garcia R, Thibault G, Deschepper CF, Reudelhuber TL. Evidence for intracellular generation of angiotensin II in rat juxtaglomerular cells. FEBS Lett 422: 395–399, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mitchell KD, Navar LG. Influence of intrarenally generated angiotensin II on renal hemodynamics and tubular reabsorption. Renal Physiol Biochem 14: 155–163. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Miyata N, Park F, Li XF, Cowley AW Jr. Distribution of angiotensin AT1 and AT2 receptor subtypes in the rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 277: F437–F446, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moritz KM, Boon WC, Wintour EM. Aldosterone secretion by the mid-gestation ovine fetus: role of the AT2 receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol 157: 153–160, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ozono R, Wang ZQ, Moore AF, Inagami T, Siragy HM, Carey RM. Expression of the subtype 2 angiotensin (AT2) receptor protein in rat kidney. Hypertension 30: 1238–1246, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patzak A, Mrowka R, Storch E, Hocher B, Persson PB. Interaction of angiotensin II and nitric oxide in isolated perfused afferent arterioles of mice. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1122–1127, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patzak A, Persson AE. Angiotensin II-nitric oxide interaction in the kidney. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 16: 46–51, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pendergrass KD, Averill DB, Ferrario CM, Diz DI, Chappell MC. Differential expression of nuclear AT1 receptors and angiotensin II within the kidney of the male congenic mRen2.Lewis rat. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F1497–F1506, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pendergrass KD, Gwathmey TM, Michalek RD, Grayson JM, Chappell MC. Nuclear angiotensin II AT1 receptors mediate the formation of reactive oxygen species (Abstract). Hypertension 52: E48, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robillard JE, Page WV, Mathews MS, Schutte BC, Nuyt AM, Segar JL. Differential gene expression and regulation of renal angiotensin II receptor subtypes (AT1 and AT2) during fetal life in sheep. Pediatr Res 38: 896–904, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salomone LJ, Howell NL, McGrath HE, Kemp BA, Keller SR, Gildea JJ, Felder RA, Carey RM. Intrarenal dopamine D1-like receptor stimulation induces natriuresis via an angiotensin type-2 receptor mechanism. Hypertension 49: 155–161, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schelling JR, Linas SL. Angiotensin II-dependent proximal tubule sodium transport requires receptor-mediated endocytosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 266: C669–C675, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schütz S, Le Moullec JM, Corvol P, Gasc JM. Early expression of all the components of the renin-angiotensin-system in human development. Am J Pathol 149: 2067–2079, 1996. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Senbonmatsu T, Saito T, Landon EJ, Watanabe O, Price E Jr, Roberts RL, Imboden H, Fitzgerald TG, Gaffney FA, Inagami T. A novel angiotensin II type 2 receptor signaling pathway: possible role in cardiac hypertrophy. EMBO J 22: 6471–6482, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sherrod M, Liu X, Zhang X, Sigmund CD. Nuclear localization of angiotensinogen in astrocytes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288: R539–R546, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sigmon DH, Beierwaltes WH. Renal nitric oxide and angiotensin II interaction in renovascular hypertension. Hypertension 22: 237–242, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Siragy HM, Inagami T, Carey RM. NO and cGMP mediate angiotensin AT2 receptor-induced renal renin inhibition in young rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 293: R1461–R1467, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thekkumkara T, Linas SL. Role of internalization in AT1A receptor function in proximal tubule epithelium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 282: F623–F629, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL. Signal transduction mechanisms mediating the physiological and pathophysiological actions of angiotensin II in vascular smooth muscle cells. Pharmacol Rev 52: 639–672, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vila-Porcile E, Corvol P. Angiotensinogen, prorenin, and renin are co-localized in the secretory granules of all glandular cells of the rat anterior pituitary: an immunoultrastructural study. J Histochem Cytochem 46: 301–311, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang JM, Slembrouck D, Tan J, Arckens L, Leenen FH, Courtoy PJ, De Potter WP. Presence of cellular renin-angiotensin system in chromaffin cells of bovine adrenal medulla. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H1811–H1818, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ye S, Nosrati S, Campese VM. Nitric oxide (NO) modulates the neurogenic control of blood pressure in rats with chronic renal failure (CRF). J Clin Invest 99: 540–548, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhuo J, Dean R, MacGregor D, Alcorn D, Mendelsohn FA. Presence of angiotensin II AT2 receptor binding sites in the adventitia of human kidney vasculature. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol Suppl 3: S147–S154, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhuo JL, Li XC. Novel roles of intracrine angiotensin II and signaling mechanisms in kidney cells. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst 8: 23–33, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]