Abstract

Research shows high comorbidity between Cluster B Personality Disorders (PDs) and Alcohol Use Disorders (AUDs). Studies of personality traits and alcohol use have identified coping and enhancement drinking motives as mediators of the relation among impulsivity, negative affectivity or affectivity instability, and alcohol use. To the extent that certain PDs reflect extreme expression of these traits, drinking motives were hypothesized to mediate the relation between PD symptoms and presence/absence of an alcohol use disorder (AUD). This hypothesis was tested using a series of cross-sectional and prospective path models estimating the extent that coping and enhancement drinking motives mediated the relation between cluster A, B, and C PD symptom counts and AUD diagnosis among a sample of 168 young adults between ages 18 and 21. Enhancement motives mediated the cross-sectional relation between Cluster B symptoms and AUD. Prospectively, enhancement motives partially mediated the relation between Cluster B personality symptoms and AUD through the stability of Year 1 AUD to Year 3 AUD. Results suggest that enhancement motives may be especially important in understanding the relation between Cluster B personality disorders and AUDs.

The rate of comorbidity between Personality Disorders (PDs) and Alcohol Use Disorders (AUDs) is high in both clinical and population-based samples (Ball, Tennen, Poling, Kranzler, & Rounsaville, 1997; Grant, Stinson, Dawson, Chou, & Ruan, 2005; Sher, Trull, Bartholow, & Vieth, 1999; Sher & Trull, 2002; Skodol, Oldham, & Gallagher, 1999; Verheul, Hartgers, van den Brink, & Koeter, 1998). Despite numerous studies showing a high association between these disorders, little is known about why these disorders tend to co-occur. Knowledge of those factors that contribute to this comorbidity would not only guide research on each of these disorders, individually, but would also inform clinical approaches and treatment options for those with co-occurring disorders.

According to the dimensional approach to personality pathology, these disorders represent extreme maladaptive variants of normal personality traits (see Trull & Durrett, 2005, for a review). From this perspective, one approach to understanding the associations between PDs and AUDs may be through identifying those shared personality features that contribute to symptoms of both disorders. Trull, Sher, Minks-Brown, Durbin, and Burr (2000) suggest that the combination of the underlying personality traits of impulsivity and affective instability/negative affectivity may account for high rates of AUDs among specific PDs, such as Cluster B personality disorders (Trull et al., 2000; Trull, Waudby, & Sher, 2004). Impulsivity and negative affectivity are two personality traits that are represented in the normal population, as evidenced by their representation in standard conceptualizations of personality such as the Five-Factor Model (Digman, 1997; Goldberg, 1993; John, 1990; John & Srivastava, 1999; McCrae & Costa, 1999) and “Big Three” (Eysenck, 1947; Eysenck & Eysenck, 1975) approaches, and are characteristic of Cluster B PDs (e.g., borderline personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder).

There is considerable research on the association between the personality traits of impulsivity and affective instability and the Cluster B personality disorders (e.g., see Trull et al., 2000). Furthermore, high scores on measures of these traits are associated with alcohol use problems (Sher et al., 1999). For example, impulsivity in childhood and adolescence is related to greater risk of future alcohol dependence (e.g., Bates & Labouvie, 1995; Caspi et al., 1997; Cloninger, Sigvardsson, & Bohman, 1988; Hawkins, Catalano, & Miller, 1992; Schuckit, 1998; Zucker, Fitzgerald, & Moses, 1995), and adults with high impulsivity scores are more likely to be diagnosed with alcoholism (e.g., Bergman & Brismar, 1994), as are offspring of highly impulsive individuals (e.g., Alterman et al., 1998; Sher, 1991).

Negative affectivity and problems with emotion regulation are also shown to relate to alcohol problems. Because these features involve lack of the ability to regulate one’s emotional states, some suggest that substance abuse results from the attempt to regulate negative emotions (Grayson & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2005; Sher et al., 1999; Sher & Grekin, 2007). Consistent with this hypothesis, negative affectivity is characteristic of both AUDs and mood disorders such as anxiety and depression (e.g., Kessler et al., 1997; Kushner et al., 1996; Sher & Trull, 1994), and scores on measures of negative affectivity are higher among individuals who meet criteria for AUDs (e.g., Brooner, Templer, Svikis, Schmidt, & Monopolis, 1990; Meszaros, Willinger, Fischer, Schonbeck, & Aschauer, 1996) and vice versa (e.g., McGue, Slutske, Taylor, & Iacono, 1997). This relationship has also been demonstrated in nonclinical samples (Sher et al., 1999), where participants with higher negative affectivity scores were more likely to meet diagnostic criteria for an AUD.

Drinking motives are one set of factors that have been identified as potential mediators in the relation between impulsivity and affective instability and alcohol use (Cooper, 1994), specifically due to their theoretical connections to alcohol dependence as a means of coping with negative affectivity (i.e., coping motives) and excessive alcohol use as a means of enhancing positive emotional states (i.e., enhancement motives) among individuals high on traits associated with sensation seeking (Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995). Drinking motives are hypothesized to represent the function alcohol use is serving for individuals and are thought to be the proximal mechanisms through which other factors, such as personality traits, operate (Sher et al., 1999). Drinking to cope with negative subjective states and emotions (coping motives) and drinking to enhance positive emotions (enhancement motives; Cooper, 1994; Cooper et al., 1995) are the two types of motives predicted to be most relevant for explaining the relation between Cluster B PDs and alcohol problems. Given that problems with emotion regulation and affective instability are characteristic of Cluster B personality disorders (Linehan, 1993; Newhill, Mulvey, & Pilkonis, 2004; Trull et al., 2000; Trull, 1992), it follows that Cluster B PD individuals’ alcohol use might be motivated by the desire to regulate these negative emotions. Furthermore, in personality trait research in normal populations, coping motives tend to be associated with personality traits such as negative emotionality, anxiety sensitivity, and affective lability (Simons, Gaher, Correia, Hansen, & Christopher, 2005; Stewart, Loughlin, & Rhyno, 2001; Stewart & Devine, 2000; Stewart, Zvolensky, & Eifert, 2001; Theakston, Stewart, Dawson, Knowlden-Loewen, & Lehman, 2004). Enhancement motives tend to be associated with low conscientiousness (Stewart, Loughlin, & Rhyno, 2001; Stewart & Devine, 2000), sensation seeking (Cooper et al., 1995; Simons et al., 2005), and impulsivity (Lynam et al., 2005), features relevant to Cluster B PDs such as BPD (Trull et al., 2000) and antisocial personality disorder (Slutske et al., 2002).

Coping and enhancement motives are also important because they are likely to be associated with excessive alcohol consumption and negative alcohol consequences characteristic of the alcohol problems commonly seen in PD individuals. A recent review of the drinking motives literature (Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels, 2006) found that coping motives are the most likely to lead to negative consequences from drinking while enhancement motives tend to have the highest associations with heavy drinking, which in turn leads to alcohol-related problems. Coping motives have been shown to lead to drinking problems both directly and indirectly, whereas enhancement motives typically lead to drinking problems indirectly through heavier alcohol consumption (Cooper, Russell, Skinner, & Windle, 1992; Cooper et al., 1995; Cutter & O’Farrell, 1984; McCarty & Kaye, 1984).

Recently, Tragesser, Sher, Trull, and Park (2007) tested whether coping and enhancement motives mediated the relation between Cluster B PD symptoms and alcohol use and problems. In that study, coping motives mediated the cross-sectional association between Cluster B symptoms and both alcohol consequences and dependences features, and enhancement motives mediated the relation between Cluster B symptoms and alcohol use quantity, consequences, dependence features, and concurrent and prospective development of an AUD.

Although Tragesser et al.’s (2007) results supported the hypothesis that Cluster B features may relate to alcohol problems through mechanisms of impulse control and emotion regulation, as evidenced by the association through drinking motives, their study was limited by the fact that the personality disorder data were only available for individuals in their late 20s and over. This is a significant limitation based on research showing that the highest rates of alcohol dependence are in the late teens and early 20s (Grant et al., 2004). Personality traits related to emotional instability are typically only consistently associated with AUDs in adult samples (Sher et al., 1999), and this has led researchers in the area of alcoholism and personality to consider subtypes of alcoholism based on age of onset and associations with personality traits. Specifically, neuroticism and emotional instability and later age of onset characterized one type of alcoholism, whereas antisocial or impulsive features and younger age of onset is more characteristic of the other (Babor et al., 1992; Cloninger, 1987; Finn et al., 1997; Gomberg, 1997; Sher & Trull, 1994). There has been no known research to date examining these associations from the perspective of Cluster B symptoms and the development of AUDs through drinking motives in younger individuals such as late adolescence or early adulthood who are in their period of peak risk for heavy drinking (Johnston, O’Malley, & Bachman, 1995; Midanik & Clark, 1993) and alcohol abuse and dependence (Grant et al., 2004). The purpose of the present study was to see if similar patterns of comorbidity and their associations with drinking motives can be observed when observing individuals who are in their heaviest drinking years and relatively unconstrained by incompatibilities with various adult roles (e.g., wage earner, spouse, parent).

METHOD

Participants in the present analyses included 168 (94 females, 74 males) primarily Caucasian (n = 142) college students between age 18 and 19 at Year 1 and age 19 and 21 approximately two years later (Year 3) selected from a sample collected in the investigation of borderline personality features among young adults (see Trull, 2001 for details).

MATERIALS AND PROCEDURE

Alcohol abuse/dependence diagnoses and personality disorder symptom counts were obtained through the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders/Nonpatient Version 2.0 (SCID-I NP; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1995), and the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SIDP-IV; Pfohl, Blum, & Zimmerman, 1997), respectively.

AUD and PD

Presence of AUD in the past 30 days was determined using the SCID-I NP (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1995). Interrater reliability (kappa) for the presence of an AUD was 0.97 and 1.0 at Year 1 and at Year 3, respectively. Personality disorder features were assessed using SIDP-IV. Year 1 average intraclass correlation coefficient for the number of criteria met for each Cluster personality disorder was .66, .77, and .81 (Clusters A, B, and C, respectively).

Drinking Motives

At Year 1, participants completed the 20-item Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised (Cooper, 1994). Coping included 5 items such as “drink to forget about your problems” and “drink to forget about worries.” Enhancement included 5 items such as “drink because it’s exciting” and “drink because it gives me a pleasant feeling.” Items were rated on the following scale: (1) “Never,” (2) “Almost Never,” (3) “Some of the time,” (4) “About half of the time,” (5) “Most of the time,” (6) “Almost Always.” Coping and enhancement motive composites were created using an average of the 5 items on each scale. Reliability estimates for both coping motives (α = .93) and for enhancement motives (α = .91) were excellent.

RESULTS

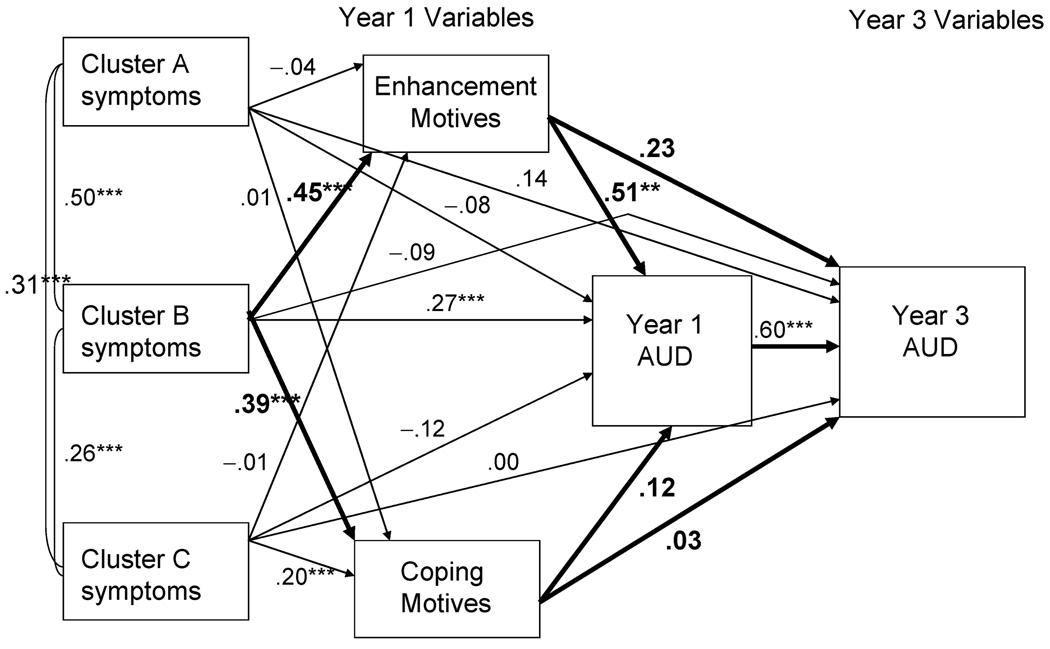

A path analysis was conducted using Mplus version 3.13 (Muthen & Muthen, 2005) to test the hypothesis that the relation between Year 1 Cluster B symptoms (expected to reflect impulsive and affectively unstable personality traits) and Year 3 alcohol-related variables was mediated by Year 1 drinking motives within a fully saturated model (see Figure 1). Symptoms associated with other PD Clusters (A and C), were also controlled. Sex was modeled as an exogenous variable (with all other variables regressed onto sex) to control for gender effects.

FIGURE 1.

Path Model of Structural Paths from Year 1 Personality Disorder Symptoms to Year 1 Drinking Motives to Alcohol Use Disorder (Year 1 and Year 3). Predicted paths are indicated in bold.

Three types of mediation were tested in the present study. First, cross-sectional mediation represents the case where all variables of interest were measured at a single time point. Cross-sectional mediation does not address the direction of these relations and therefore does not warrant a strong conclusion of whether Cluster B symptoms or drinking motives leads to subsequent AUD diagnosis. In addition to this cross-sectional mediation, we also tested two types of prospective mediation. The first type, which we refer to as unique prospective mediation, is a test of the effects of a predictor and mediating variable on an outcome variable at a later point in time, controlling for concurrent shared variance among the predictor and outcome variables at the initial time point. In this type of mediation, inferences concerning direction are more appropriate.

A second type of prospective mediation, which we refer to as “prospective mediation via Year 1,” is similar to cross-sectional mediation. In this instance, the variables of interest are measured at a single time point, as in cross-sectional mediation, with the addition that the outcome variable is also measured at a second time point. In this case, the mediating variable(s) can account for variance in the prospective outcome variable through a relation with the outcome variable measured at a concurrent time point. These three types of mediation will be heretofore referred to as cross-sectional mediation, unique prospective mediation, and prospective mediation via Year 1, respectively.

Bivariate relations are presented in Table 1. Direct paths and indirect effects from the saturated model are presented in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. Structural paths are presented in Figure 1. Enhancement motives at Year 1 partially mediated the relation between Cluster B symptoms and AUD at Year 1 (cross-sectional mediation). Unique prospective effects were not significant; prospective indirect effects from Cluster B symptoms through enhancement and coping motives to Year 3 AUD, controlling for Year 1 AUD, were not significant. However, there was evidence of prospective mediation via Year 1, such that enhancement motives mediated the relation between Year 1 Cluster B symptoms and Year 3 AUD through Year 1 AUD stability.

TABLE 1.

Bivariate Correlations Between Personality Disorder Symptom Counts, Drinking Motives, and AUD Years 1 and 3

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cluster A count | — | ||||||

| 2. Cluster B count | .40** | — | |||||

| 3. Cluster C count | .42** | .24** | — | ||||

| 4. Enhancement | .05 | .36** | −.02 | — | |||

| 5. Coping | .17* | .40** | .19** | .58** | — | ||

| 6. AUD Year 1 | .02 | .44** | −.05 | .44** | .37** | — | |

| 7. AUD Year 3 | .08 | .26** | −.03 | .38** | .36** | .43** | — |

Note. N = 168. AUD = DSM-IV past-month alcohol use disorder

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

TABLE 2.

Direct Paths From Sex, Drinking Motives, and Personality Disorder Symptom Counts to AUD at Years 1 & 3

| Variable | Year 1 AUD | Year 3 AUD |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | .08 | .05 |

| Enhancement | .51** | .23 |

| Coping | .12 | .03 |

| Cluster A | −.08 | .14 |

| Cluster B | .27** | −.09 |

| Cluster C | −.12 | .00 |

| AUD Year 1 | — | .60** |

Note. N = 168. AUD = DSM-IV past-month alcohol use disorder

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

TABLE 3.

Indirect Effects From Cluster B Personality Disorder Symptom Counts to AUD Years 1 & 3

| Cross-sectional |

Unique Prospective |

Prospective (via Year 1) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | via ENH | via COPE | via ENH | via COPE | via ENH | via COPE |

| AUD | .23* | .05 | .10 | .01 | .14* | .03 |

Note. N = 168. AUD = DSM-IV past-month alcohol use disorder; ENH = enhancement motives scores; COPE = coping motives scores

p <.05

DISCUSSION

Enhancement drinking motives partially mediated the relation between personality disorder symptoms characterized by high affective instability and impulsivity and AUD. However, these effects were limited to tests of mediation that are agnostic with respect to directionality of effects (cross-sectional and prospective mediation via Year 1). While the effects were significant in predicting Year 3 AUD (prospective development of an AUD), this was only through the path from Year 1 AUD to Year 3 AUD, indicating that this prediction was largely accounted for by AUD stability from Years 1 to 3. The hypothesis that coping motives would also mediate the association to AUDs was not supported. Thus, the present results diverge from previous findings in that enhancement motives were the predominant motives mediating the effect from Cluster B PD symptoms to AUD in this younger sample, with much stronger effects compared to coping motives, which were not significant. This is in contrast to Tragesser et al.’s (2007) findings among adults in their late 20s and early 30s, where coping motives showed more similar (and in some cases slightly stronger) associations with alcohol problems compared to enhancement motives.

These findings are important for two reasons. First, these results are consistent with dimensional views of personality disorders that assume a continuum of personality variation ranging from normal-range personality trait variation to personality pathology (Widiger & Trull, 2007). That is, based on evidence that enhancement motives are associated with impulsivity and related traits (Lynam et al., 2005; McCrae & Costa, 1985; Stewart et al., 2001; Stewart & Devine, 2000; Theakston et al., 2004) and the regulation of positive emotions (Grayson & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2005), the present data provide evidence that the features of impulsivity and affective instability may be the mechanisms by which Cluster B personality features tend to be associated with AUDs. This pattern of results suggests that drinking motives operate similarly for normal personality traits and personality disorder symptoms, supporting the theoretical connection between these constructs. Furthermore, these results also suggest that impulsivity and emotion regulation in the form of the maintenance and enhancement of positive emotional states may be an important target for AUD prevention and intervention among individuals with Cluster B PD symptoms.

Second, these findings suggest, albeit indirectly, that developmental differences in the onset of AUDs and alcohol problems may be relevant to the mechanisms underlying PD-AUD comorbidity as well. In particular, although Tragesser et al. (2007) found that coping motives were mediators between Cluster B PD symptoms and alcohol dependence symptoms among older adults, these findings were not found for AUD diagnoses in this late adolescent, collegiate sample. This indicates that just as alcoholism may have different developmental mechanisms at earlier and later time points, the personality mechanisms underlying PD-AUD comorbidity may also be different depending on one’s stage of life. For instance, impulsivity may be the predominant feature predicting alcohol problems among those with Cluster B features at younger ages, whereas affective instability may only be related to the development of alcohol problems in this age group through the tendency to lead to a desire to enhance or maintain what is typically experienced as a fleeting positive emotional state. In other words, this affective instability characteristic of Cluster B symptoms may only become associated with alcohol use for the reduction of negative emotional states later in life. These age-related discrepancies in how alcohol is likely to be used have important treatment implications. For younger individuals with the impulsivity and affective instability characteristic of Cluster B features, alcohol treatment may be most effectively targeted at warning youth against the habitual use of alcohol for the enhancement of their positive emotions as well as treatment strategies that target impulsive tendencies; for adults with these same personality traits, treatment may be most effective when it also includes more adaptive strategies for the amelioration of their negative moods.

A few limitations of the present research are worth noting. One limitation of the present study is that the population consisted of nonclinical participants. Future research is needed to test whether drinking motives operate similarly in clinical samples. One suggestion for future research is to test these relationships among samples that show higher rates of other PDs, particularly a wider range of clinically significant PD features other than BPD. This type of replication would add evidence to the generalizability of these effects by showing that they are not only a function of normal-range functioning levels of these personality traits or alcohol use patterns. This would also enable tests of these relations among each of the specific personality disorders individually. Testing each PD for their specific pathways to alcohol use through mediators such as drinking motives is important for identifying possible etiological distinctions between these disorders, as well as potential differences in the mechanisms underlying comorbidity with AUDs. Testing the relation between alcohol-related problems and specific PD symptomatology would be important for identifying specific AUD-PD relations that, while they may be important for a specific personality disorder, may not be consistent across the other PDs in a particular cluster (e.g., see Sher & Trull, 2002). Finally, a limitation of the present study was the insufficient sample size to test these associations by gender. Although we were able to control for the effects of gender on our structural paths, this does not allow for examination of specific differences in these paths across men and women, which may be important for understanding mediational links between PD features and alcohol problems across coping and enhancement motives. This is based on evidence that rates of the use of coping and enhancement motives are different for men and women, especially during late adolescence (Cooper, 1994; Birch, Stewart, & Zack, 2006; see also Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels, 2006 for review). These differences in rates indicate some gender-specificity that may also be reflected in how motives operate in mediating the paths between alcohol problems and personality constructs or PD symptoms. For example, men show stronger tendencies to use enhancement motives (Cooper, 1994; Birch et al., 2006), and therefore male affective instability and impulsivity associated with Cluster B features may be more likely to be mediated through enhancement motives compared to females.

In conclusion, the present results have two primary implications. First, enhancement motives were more relevant to understanding the relations between Cluster B personality disorder symptoms and AUDs in late adolescence and early adulthood. The association between enhancement motives and the trait of impulsivity in previous research implicates the feature of impulsivity as a major underlying dimension in the relation between Cluster B disorders and alcohol problems, especially in younger samples. Affective instability may be relevant to alcohol problems through the regulation of positive emotional states, consistent with Grayson and Nolen-Hoeksema’s (2005) conceptualization of the association between affective instability and enhancement motives. In contrast, while coping motives were hypothesized to relate to drinking problems through the connection to the tendency to experience negative emotions among individuals with PD symptoms, coping motives were not a significant mediator between Cluster B PDs and AUD diagnosis. Thus we conclude that treatment of comorbid AUDs and PDs in this life stage should focus on not only developing more adaptive strategies for positive emotion regulation/maintenance, but should also focus on managing features related to impulsive or sensation-seeking personality traits. Finally, these results support dimensional/continuum perspectives of personality disorders by showing that mechanisms identified in research on broad personality domains also apply to personality disorders believed to be rooted in normal personality constructs.

Acknowledgments

The present research was supported by NIH grants T32 AA13526 and AA13987 (PI = Kenneth J. Sher), R01MH52695 (PI = Timothy J. Trull), and P50 AA11998 (PI = Andrew Heath).

REFERENCES

- Alterman AI, Bedrick J, Cacciola JS, Rutherford MJ, Searles JS, McKay JR, Cook TG. Personality pathology and drinking in young men at high and low familial risk for alcoholism. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59:495–502. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Hofmann M, DelBoca FK, Hesselbrock V, Meyer RE, Dolinsky ZS, Rounsaville B. Types of alcoholics: I. Evidence for an empirically derived typology based on indicators of vulnerability and severity. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49:599–608. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080007002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball SA, Tennen H, Poling JC, Kranzler HR, Rounsaville BJ. Personality, temperament, and character dimensions and the DSM-IV personality disorders in substance abusers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:545–553. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates ME, Labouvie EW. Personality environment constellations and alcohol use: A process oriented study of intra-individual change during adolescence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1995;9:23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman B, Brismar B. Hormone levels and personality traits in abusive and suicidal male alcoholics. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1994;18:311–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch CD, Stewart SH, Zack M. Emotion and motive effects on drug-related cognition. In: Wiers RW, Stacy AW, editors. Handbook on implicit cognition and addiction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2006. pp. 267–280. [Google Scholar]

- Brooner RK, Templer D, Svikis DS, Schmidt C, Monopolis S. Dimensions of alcoholism: A multivariate analysis. Journal of Studies. 1990;51:77–81. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1990.51.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Begg D, Dickson N, Harrington AL, Langley J, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. Personality differences predict health-risk behaviors in young adulthood: Evidence from a longitudinal study. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1997;73:1052–1063. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.5.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR. A systematic method for clinical description and classification of personality variants. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;44:573–588. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180093014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR, Sigvardsson S, Bohman M. Childhood personality predicts alcohol abuse in young adults. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 1988;12:494–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1988.tb00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, Skinner JB, Windle M. Development and validation of a three-dimensional measure of drinking motives. Psychological Assessment: Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;4:123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Cutter HSG, O’Farrell TJ. Relationship between reasons for drinking and customary drinking behavior. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1984;45:321–325. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1984.45.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digman JM. Higher-order factors of the Big Five. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;73:1246–1256. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.6.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driessen M, Veltrup C, Wetterling T, John U, Dilling H. Axis I and Axis II comorbidity in alcohol dependence and the two types of alcoholism. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22:77–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ. Dimensions of personality. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Manual of the Eysenck personality questionnaire. London: Hodder & Stoughton; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR, Sharkansky EJ, Viken R, West TL, Sandy J, Bufferd GM. Heterogeneity in the families of sons of alcoholics: The impact of familial vulnerability type on offspring characteristics. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:26–36. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV disorders, nonpatient edition (Version 2.0) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. The structure of phenotypic personality traits. American Psychologist. 1993;48:26–34. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomberg ESL. Alcohol abuse: Age and gender differences. In: Wilsnack RW, Wilsnack SC, editors. Gender and alcohol: Individual and social perspectives. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;74:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ. Co-occurrence of DSM-IV personality disorders in the United States: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2005;46:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayson CE, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Motives to drink as mediators between childhood sexual assault and alcohol problems in adult women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:137–145. doi: 10.1002/jts.20021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller V. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John OP. The “big five” factor taxonomy: Dimensions of personality in the natural language and in questionnaires. In: Pervin LA, editor. Handbook of personality. New York: Guilford Press; 1990. pp. 66–100. [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Srivastava S. The big five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In: Pervin LA, John OP, editors. Handbook of personality. Theory and research. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 102–138. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; National survey results on drug use from the monitoring the future study, 1975–1994, (Vol. 2., NIH Publication No. 96–4027) 1995

- Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC. Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:313–321. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Who drinks and why? A review of socio-demographic, personality, and contextual issues behind the drinking motives in young people. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:1844–1857. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MG, Mackenzie TB, Fiszdon J, Valentiner DP, Foa E, Anderson N, Wangensteen D. The effects of alcohol consumption on laboratory-induced panic and state anxiety. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:264–270. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830030086013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Raine A, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Adolescent psychopathy and the Big Five: Results from two samples. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:431–443. doi: 10.1007/s10648-005-5724-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty D, Kaye M. Reasons for drinking: Motivational patterns and alcohol use among college students. Addictive Behaviors. 1984;9:185–188. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(84)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT., Jr Updating Norman’s “adequate taxonomy”: Intelligence and personality dimensions in natural language and in questionnaires. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1985;49:710–721. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.49.3.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT. A five-factor theory of personality. In: Pervin LA, John OP, editors. Handbook of personality. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 139–153. [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Slutske W, Taylor J, Iacono WG. Personality and substance use disorders: I. Effects of gender and alcoholism subtype. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1997;21:513–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meszaros K, Willinger U, Fischer G, Schonbeck G, Aschauer HN. The tridimensional personality model: Influencing variables in a sample of detoxified alcohol dependents. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1996;37:109–114. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(96)90570-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Clark WB. Drinking-related problems in the United States: Description and trends, 1984–1990. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;56:395–402. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Langenbucher J, Labouvie E, Miller KJ. The co-morbidity of alcoholism and personality disorders in a clinical population: Prevalence rates and relation to alcohol typology variables. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:74–84. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Fourth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Newhill CE, Mulvey EP, Pilkonis PA. Initial development of a measure of emotional dysregulation for individuals with cluster B personality disorders. Research on Social Work Practice. 2004;14:443–449. [Google Scholar]

- Pfolh B, Blum N, Zimmerman M. Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality: SIDP-IV. Iowa City, IA: Author; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast ML. Substance use and abuse among college students: A review of recent literature. Journal of American College Health. 1994;43:99–113. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1994.9939094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA. Biological, psychological, and environmental predictors of alcoholism risk: A longitudinal study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59:485–494. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ. Children of alcoholics: A critical appraisal of theory and research. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Grekin ER. Alcohol and affect regulation. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 560–580. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Trull TJ. Personality and disinhibitory psychopathology: Alcoholism and antisocial personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:92–102. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Trull TJ, Bartholow BD, Vieth A. Personality and alcoholism: Issues, methods, and etiological processes. In: Leonard E, Blane H, editors. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. New York: The Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 54–105. [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE, Oldham JM, Gallager PE. Axis II comorbidity of substance use disorders among patients referred for treatment of personality disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:733–738. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutske WS, Heath AC, Madden PAF, Bucholz KK, Stratham DJ, Martin NG. Personality and genetic risk for alcohol dependence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:124–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Devine H. Relations between personality and drinking motives in young adults. Personality and Individual Differences. 2000;29:495–511. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Loughlin HL, Rhyno E. Internal drinking motives mediate personality domain-drinking relations in young adults. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:271–286. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Zvolensky MJ, Eifert GH. Negative-reinforcement drinking motives mediate the relation between anxiety sensitivity and increased drinking behaviour. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;31:157–171. [Google Scholar]

- Theakston JA, Stewart SH, Dawson MY, Knowlden-Loewen SAB, Lehman DR. Big-Five personality domains predict drinking motives. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;37:971–984. [Google Scholar]

- Tragesser SL, Sher KJ, Trull TJ, Park A. Personality disorder symptoms, drinking motives, and alcohol use and consequences: Cross-sectional and prospective mediation. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;15:282–292. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.3.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ. DSM-III-R personality disorders and the five-factor model of personality: An empirical comparison. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101:553–560. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.3.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ. Structural relations between borderline personality disorder features and putative etiological correlates. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:471–481. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.3.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Durrett CA. Categorical and dimensional models of personality disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:355–380. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Sher KJ, Minks-Brown C, Durbin J, Burr R. Borderline personality disorder and substance use disorders: A review and integration. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:235–253. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Waudby CJ, Sher KJ. Alcohol, tobacco, and drug use disorders and personality disorder symptoms. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2004;12:65–75. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.12.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheul R, Hartgers C, Van den Brink W, Koeter MWJ. The effect of sampling, diagnostic criteria and assessment procedures on the observed prevalence of DSM-III-R personality disorders among treated alcoholics. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59:227–236. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Trull TJ. Plate tectonics in the classification of personality disorder: Shifting to a dimensional model. American Psychologist. 2007;62:71–83. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Fitzgerald HE, Moses HD. Emergence of alcohol problems and the several alcoholisms: A developmental perspective on etiologic theory and life course trajectory. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 2. Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation. New York: Wiley; 1995. pp. 677–711. [Google Scholar]