Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate outcomes following implementation of a checklist with criteria for switching from intravenous (iv) to oral antibiotics on unselected patients on two general medical wards.

Methods

During a 12 month intervention study, a printed checklist of criteria for switching on the third day of iv treatment was placed in the medical charts. The decision to switch was left to the discretion of the attending physician. Outcome parameters of a 4 month control phase before intervention were compared with the equivalent 4 month period during the intervention phase to control for seasonal confounding (before–after study; April to July of 2006 and 2007, respectively): 250 episodes (215 patients) during the intervention period were compared with the control group of 176 episodes (162 patients). The main outcome measure was the duration of iv therapy. Additionally, safety, adherence to the checklist, reasons against switching patients and antibiotic cost were analysed during the whole year of the intervention (n = 698 episodes).

Results

In 38% (246/646) of episodes of continued iv antibiotic therapy, patients met all criteria for switching to oral antibiotics on the third day, and 151/246 (61.4%) were switched. The number of days of iv antibiotic treatment were reduced by 19% (95% confidence interval 9%–29%, P = 0.001; 6.0–5.0 days in median) with no increase in complications. The main reasons against switching were persisting fever (41%, n = 187) and absence of clinical improvement (41%, n = 185).

Conclusions

On general medical wards, a checklist with bedside criteria for switching to oral antibiotics can shorten the duration of iv therapy without any negative effect on treatment outcome. The criteria were successfully applied to all patients on the wards, independently of the indication (empirical or directed treatment), the type of (presumed) infection, the underlying disease or the group of antibiotics being used.

Keywords: stewardship, policy, guidelines, antimicrobials, internal medicine

Introduction

The appropriate use of antimicrobial agents is crucial for patients’ safety and public health,1–5 particularly in view of increasing drug resistance.6 Hence, antimicrobial stewardship programmes were developed as an essential field of work for infectious diseases (ID) specialists7 with the goal of optimizing clinical outcomes and minimizing the unintended consequences of antimicrobial use, i.e. toxicity, the selection of pathogenic organisms, emergence of resistance and high costs. The adoption of antimicrobial stewardship programme activities has, therefore, recently been advocated.8 Nevertheless, the best strategies of these programmes are not yet well established because of a paucity of evidence from well-designed studies in this field.9

One way of optimizing antibiotic use is to switch earlier from intravenous (iv) to oral therapy, with the following advantages: (i) benefits to the patient, (ii) lower costs and (iii) reduced workload, e.g. reduced incidence of catheter-related infections, a shorter length of hospital stay, a reduction in costs and an associated reduction in workload without sacrificing patient safety.10–18 Most iv antibiotics are more expensive than oral formulations, and the costs of preparing and administering are additional:12 Indirect costs have been estimated to add from 13% to 113% to the costs of the drugs themselves.19

The optimal time for switching to oral antibiotics is on days 2–4 of iv therapy, when the culture results and the initial clinical course allow a reassessment of the treatment plan.18,20–23 This reassessment is often neglected due to time constraints, change of staff, unwillingness to change the mode of therapy in an improving patient or insufficient training.24

Most studies on switching the mode of therapy have so far been restricted to specific antibiotics25–29 or medical conditions, e.g. community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).11,15,30–34 A few studies have evaluated the criteria for switching from iv antibiotics in a general population of medical patients (Table 1).12–14,16,17,35,36 However, the before–after studies were not controlled for seasonal confounding,12,14,17,36 and others were limited to specific conditions16 or to community-acquired infections,14,16 which hampers generalization to general medical ward patients. Only two studies12,13 provided information about the reason for not switching to oral antibiotics.

Table 1.

Summary comparison of previously published articles on ‘switch’ criteria on medical wards

| Authors (in chronological order) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahkee et al.13 | Laing et al.14 | Sevinc et al.12 | von Gunten et al.16 | Vogtländer et al.36 | Senn et al.35 | McLaughlin et al.17 | Mertz et al. (current study) | |

| Study design | no comparison | before–aftera | before–after | pilot study, randomized | before–after | randomized | before–after | before–after |

| Type of intervention | study team | guideline | guideline | pharmacist | guideline | study team | guideline | guideline |

| Duration of intervention | 6 months | 2 × 2 monthsa | 2 months | 6 weeks | 3 months | 5 months | 2 × 4 weeks | 12 monthsb |

| Patient population (C/I) | 0/655 | 111/113a/103a | 230/182 | 26/29 | 247/250 | 125/126 | 118/107a/93a | 698b; 176/250 |

| Population constraints | none | included only patients with CA infection | none | limited to specific diagnosesc | none | intervention on weekdays only | none | none |

| Reasons for not switching to oral antibiotic | provided | not provided | provided | not provided | not provided | not provided | not provided | provided |

| Duration of iv-Rx (C/I) | 3 days | 4.4/3.7 daysd | 6/4 daysd (iv to oral switch) | 5/5.5 dayse | −1.6 daysd iv to oral switch | −14%e to ‘modification’ of iv-Rx | 3/2 daysd | 6/5 daysd (−19%) |

| Percentage of patients switched/within number of days | 40%/7 days | 28%/3 days | 23%/no time limit | not provided | not provided | 64%/no time limit | 73%/no time limit | 30%/3 days |

| Outcome measure | relapse | readmissione, mortalitye | readmissione | not provided | not provided | mortalitye | not provided | relapsee, readmissione, mortalitye |

| Cost/savings | not provided | not provided | estimated | savings per patient | not provided | not provided | savings per patient | workload and antibiotic costs |

CA, community-acquired; iv-Rx, treatment with iv antibiotics; C/I, control group/intervention group.

Search terms: switch, oral antibiotics, antibiotic stewardship and antimicrobial stewardship.

aOne control group and two groups after implementation of the intervention.

bn = 698, number of patients in which the intervention was performed (12 months); n = 176/250, number of patients in the control and intervention groups for statistical analysis (4 months per group).

cPopulation constricted to the following diagnoses: pneumonia, urinary tract infection, gastro-enteritis or skin and soft tissue infection.

dStatistical significant difference between groups (if applicable).

eNo statistical significant difference between groups (if applicable).

We performed a before–after study with the goal to assess the effect of an adapted published checklist14,35 for physicians to follow with respect to switching from iv to oral antibiotics in a population of unselected, hospitalized patients on general medical wards.

Patients and methods

Setting

The University Hospital Basel is a 780 bed tertiary care centre serving ∼27 000 admissions annually. The study was conducted on two general internal medicine wards with ∼2500 admissions yearly and annual antibiotic costs of about €300 000.

Seven interns and residents with two senior physicians were in charge of the two study wards on weekdays. On weekends, only two interns or residents of the same team were in charge, with a senior physician on call. An ID service was available at all hours.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Cantons Basel-Stadt and Basel-Land (EKBB, Nr 126/06), which waived the patient consent, since the study was part of a quality improvement project.

Study population

All adults who were receiving iv antibiotics at the time of the study were enrolled at the moment they were admitted to one of the study wards. We excluded patients who were referred to the wards with iv antibiotic treatment that had already lasted longer than 3 days, patients on iv antibiotics who were transferred to other wards or hospitals before the third day of treatment and patients who were receiving prophylactic iv antibiotics.

Study design

The study was a before–after design study with an a priori defined time frame consisting of a 4 month control phase from 1 April 2006 through 31 July 2006 and an intervention phase from 1 April 2007 through 31 July 2007. To eliminate seasonal confounding, only these 4 months were compared although the intervention was performed during 1 year (1 August 2006 through 31 July 2007).

All patients were consecutively screened for enrolment. The patients in the control phase were enrolled retrospectively using the same criteria as for patients during the intervention phase.

Intervention

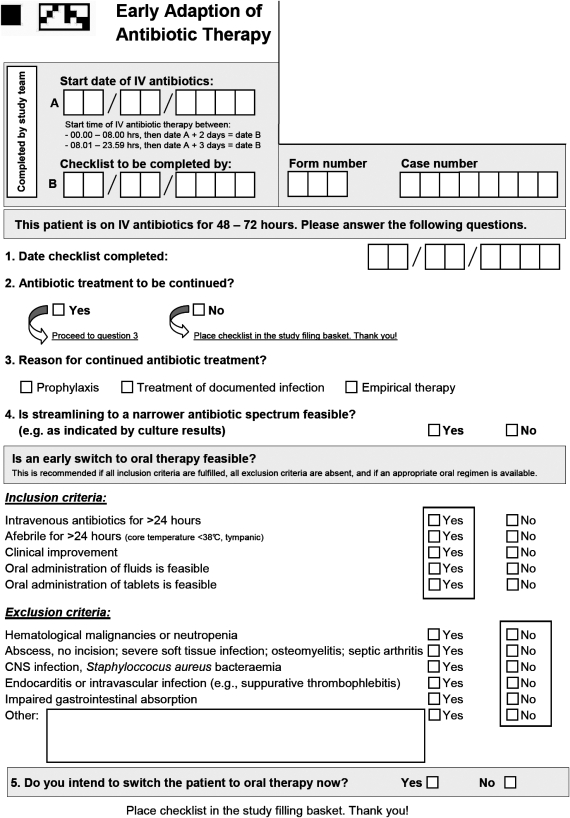

The intervention consisted of a printed checklist of criteria for switching to oral antibiotics, adapted from Laing et al.14 and Senn et al.35 (Figure 1). The checklist was placed in the patient's chart. On day 3 of iv antibiotic therapy, the physician in charge of the patient was to complete the checklist and make a decision on the basis of the checklist criteria about whether to switch to oral antibiotics. The protocol allowed the physician to complete the checklist before the third day if switching to oral antibiotics. The final decision to switch to oral antibiotics, however, was left to the discretion of the treating physician.

Figure 1.

The checklist.

If the reason for not switching to oral antibiotics was only the patient's inability to swallow tablets or fluids or was a presumed impairment in gastrointestinal absorption, a clinical pharmacist was consulted to recommend other alternatives to iv therapy if possible.

When a physician did not switch a patient to oral antibiotics despite the patient meeting all checklist criteria for doing so, he was asked to indicate the reason in a free text box on the checklist. Otherwise, there were no additional interventions by, or formal consultations with, the study team. If a physician did not complete the checklist by the end of the third day on iv therapy, he was asked to complete the checklist with respect to the target day indicated on the checklist.

We defined an episode as one uninterrupted course of antibiotic treatment. The primary antibiotic was defined as the iv antibiotic that was applied for the longest duration.

Outcome parameters

The primary endpoint was the duration of iv therapy in days. Secondary endpoints were the total number of times iv antibiotics were administered during an episode of treatment and the associated workload for nurses, the length of hospital stay, the costs and consumption of the antibiotics and the incidence of complications during iv therapy, i.e. phlebitis. We used the following indicators for assessing the safety and efficacy of the antibiotic treatment regimen: re-initiation of iv antibiotic treatment, in-hospital mortality and readmissions within 90 days of discharge.

The safety of the intervention, the adherence to the checklist's criteria and the reasons for physicians not switching patients were analysed over the entire year of the intervention (1 August 2006 to 31 July 2007). The antibiotic consumption in ‘defined daily doses’ (DDD) and costs were compared with those in the 2 years before the start of the intervention and with the year after the stop of the intervention.

Baseline assessment

The baseline assessment consisted of demographic data, the Charlson Co-morbidity Index37,38 and the presumed or documented ID.

Statistical analysis

We analysed the primary endpoint using the first treatment episode for each patient only. In a secondary analysis, we analysed all treatment episodes for all patients and corrected the standard errors for the correlation of treatment durations in patients who received more than one treatment episode.

Because the primary outcome measure showed a log normal distribution, we performed statistical analyses on the log data. For the primary analysis, we fitted a univariate and a multivariate adjusted linear regression model for the log-transformed response and used treatment as covariate. For the secondary analysis involving all treatment episodes, we used generalized estimating equations (the GEE approach)39 on the log-transformed response using the robust method to correct the confidence intervals (CIs) and P values for the within-patient correlation.

The effect estimates from both the linear models and the GEE models were finally back-transformed to the original scale. The back-transformed effect estimate corresponds to the ratio of the median antibiotic treatment duration in the control group to the median antibiotic treatment duration in the intervention group. We used R statistical software, version 2.5.1, to fit these models and for inferential statistics.

To compare differences in the distribution of baseline characteristics between patients who were enrolled in the control phase and patients who were enrolled in the interventional phase, we used the χ2 test for binary data and the Mann–Whitney U-test or log-rank test for continuous data (SPSS 15.0 software, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

All analyses are reported with 95% CIs. Tests with a two-sided P value <5% were regarded as significant.

Results

Patient populations

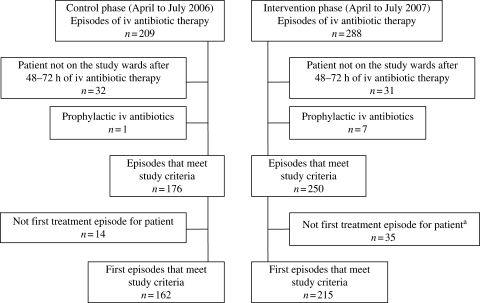

For detailed analysis, a total of 250 iv antibiotic treatment episodes in 215 patients during the intervention phase were compared with 176 episodes in 162 patients during the control phase. For primary analysis, only the first episode per patient was analysed. For statistical analysis, all episodes were included. Potentially eligible patients who were excluded are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Patient populations in the control and intervention phases. aThree of these episodes were excluded because these patients had already been included in the control phase.

To assess the safety of the intervention, the adherence to the checklist's criteria and the reasons for physicians not switching patients, all patients enrolled over the entire year of the intervention were analysed (n = 698 episodes, August 2006 to July 2007).

Analysis of checklists

All of the 698 checklists that were distributed from 1 August 2006 through 31 July 2007 were retrieved. Of these, 546 (78%) were completed on the target day for switching to oral antibiotics or earlier. In 52/698 episodes (7.4%), antibiotic treatment was stopped and in 646/698 episodes (92.6%), antibiotic treatment was continued (Table 2). A switch to oral antibiotics was decided in 191/646 episodes (29.6%). Therefore, iv therapy was discontinued on the third day of iv therapy—either by stopping or switching to oral therapy—in 243/698 (34.8%) episodes. During the 4 month intervention phase, the subgroup of patients with lower respiratory tract infections (n = 72) were switched more often to oral antibiotics (rate of 42%).

Table 2.

Analysis of 646 checklists completed between 1 August 2006 and 31 July 2007 indicating continued antibiotic treatment after 48–72 h

| Episodes switched after 48–72 h |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| yes (n = 191, 29.6%) |

no (n = 455, 70.4%) |

|||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Indications | ||||

| documented infection | 142 | 74.3 | 291 | 64.0 |

| empirical treatment | 49 | 25.7 | 164 | 36.0 |

| Reasons indicated for not switching to oral therapya | ||||

| not afebrile >24 h | 16 | 8.4 | 187 | 41.1 |

| no clinical improvement | 10 | 5.2 | 185 | 40.7 |

| oral administration of fluids not feasible | 1 | 0.5 | 26 | 5.7 |

| oral administration of tablets not feasible | 3 | 1.6 | 38 | 8.4 |

| haematological malignancies or neutropenia | 16 | 8.4 | 97 | 21.3 |

| infections with strict iv indicationa | 4 | 2.1 | 94 | 20.7 |

| abscess without incisions, severe soft tissue infection, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis | 3 | 1.6 | 61 | 13.4 |

| CNS infections, Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia | 0 | 0 | 24 | 5.3 |

| endocarditis or intravascular infection | 1 | 0.5 | 20 | 4.4 |

| Impaired gastrointestinal absorption | 2 | 1.0 | 26 | 5.7 |

| Other exclusion criteria for oral therapyb | 1 | 0.5 | 94 | 20.7 |

aMore than one reason could be checked per patient as applicable.

bFor 74 patients, ‘Other exclusion criteria’ was the only criterion checked on the checklist for not switching to oral antibiotics. Of these other criteria, the most frequently mentioned reasons were: diagnoses that were thought to require iv therapy (n = 15, 16.0%); the (presumed) absence of an alternative oral therapy (n = 12, 12.7%); a senior attending physician's decision to not follow the checklist (n = 11, 11.7%); patients on immunosuppressive therapy (n = 9, 9.6%); administrative problem related to target date occurring on a weekend or other organizational issues (n = 8, 8.5%); the physician's waiting for the ward round or additional results (n = 7, 7.4%) and the physician in charge was unsure about the situation (n = 7, 7.4%).

In 38% (246/646) of the episodes of continued iv antibiotic therapy, patients met all criteria for switching to oral antibiotics on the third day; 151/246 (61.4%) of these were actually switched on the third day. The most frequent reasons indicated for not switching to oral antibiotics in the remaining cases (available in 74/95 cases) are summarized in Table 2. The physicians in charge of the study wards adhered increasingly to our guideline. In the first months of the intervention (August to October), adherence to the checklist was 48%; this rate increased continuously to 68.7%.

Of note, 40 patients were switched even though they did not meet all the criteria, but with no negative consequences; among those were 16 (14.2%) of the 113 neutropenic patients.

Patients’ characteristics in the control and intervention phase

The patients in the two study phases were comparable with respect to gender, age, co-morbidities, C-reactive protein concentration and underlying presumed or documented infection (Table 3).

Table 3.

Statistical analysis of patient characteristics with first episode of antibiotic treatment

| Patient characteristic | Control phase (1 April 2006 to 31 July 2006) n = 162 | Intervention phase (1 April 2007 to 31 July 2007) n = 215 | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender, n (%) | 73 (45.1) | 84 (39.1) | 0.243 |

| Age, median (IQR) | 66 (58–77) | 67 (55–78) | 0.950 |

| Highest C-reactive protein value within 72 h after initiation of antibiotic treatment, median (IQR) | 151 (89–232) | 144 (80–226) | 0.564 |

| Charlson Co-morbidity Index, median (IQR) | 2 (1–5) | 2 (1–4) | 0.301 |

| Malignancy, n (%) | 54 (33.3) | 87 (40.5) | 0.157 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 42 (25.9) | 48 (22.3) | 0.417 |

| HIV positive, n (%) | 3 (1.9) | 10 (4.7) | 0.140 |

| Presumed or documented ID that were treated with iv antibiotics, n (%) | |||

| lower respiratory infection | 53 (32.7) | 68 (31.6) | 0.823 |

| urinary tract infection | 23 (14.2) | 36 (16.7) | 0.500 |

| intra-abdominal infectionsb | 22 (13.6) | 33 (15.3) | 0.630 |

| fever/SIRS of unknown focus | 18 (11.1) | 20 (9.3) | 0.564 |

| skin and soft tissue infections | 10 (6.2) | 19 (8.8) | 0.337 |

| fever in neutropenia | 10 (6.2) | 12 (5.6) | 0.808 |

| infections of bones or joints | 10 (6.2) | 8 (3.7) | 0.269 |

| enteritis or colitis | 3 (1.9) | 3 (1.4) | 0.726 |

| endocarditis | 2 (1.2) | 3 (1.4) | 0.893 |

| CNS infection | 4 (2.5) | 3 (1.4) | 0.445 |

| other infections | 7 (4.3) | 10 (4.7) | 0.878 |

| Consultation by ID specialist | 38 (23.5) | 59 (27.4) | 0.367 |

ID, infectious diseases; IQR, interquartile range; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

aDifferences between groups using the Mann–Whitney U-test for non-categorical data and the χ2 test for categorical data.

bIncludes all (presumed) infections in the abdomen except enteritis and colitis.

At the beginning of the intervention, there was an initial increase in the rate of ID consultations requested by ward physicians (from August to October 2006 it was 34.7% compared with 23.5% in the control phase from April to July 2006). Later in the intervention phase, the rate decreased (27.4% from April to July 2007).

Duration of antibiotic treatment and outcome of treatment

Comparing all first episodes of patients receiving iv antibiotics in the 4 month control phase with the 4 month intervention phase at the end of the intervention—including patients not qualifying for early switch—the median duration of iv antibiotic treatment was reduced from 6.0 to 5.0 days (Table 4). The unadjusted, relative reduction in median days of iv antibiotic treatment was 16% (95% CI 4%–26%, P = 0.01) and 19% (9%–29%, P = 0.001) after adjusting for age, gender, Charlson Co-morbidity Index score, presence of malignancy and consultations with ID specialists. Stratified by group of infection (Table 3), there was a reduction of the median duration of iv therapy in all subgroups except for endocarditis, infections of bones or joints, urinary tract infections and enteritis/colitis. The reduction was statistically significant for lower respiratory tract infections only (6.25–4.5 days in median, P = 0.002).

Table 4.

Statistical analysis of outcomes for the first episode of antibiotic treatment

| Outcomes | Control phase (1 April 2006 to 31 July 2006) all first episodes n = 162 | Intervention phase (1 April 2007 to 31 July 2007) |

P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| all first episodes n = 215 | switched episodesan = 64 | |||

| Number of days of iv antibiotic treatment per patient, median (IQR) | 6 (4–11) | 5 (3.5–8.5) | 3 (3–4) | 0.005 |

| Cumulative number of applications of iv antibiotics per patient, median (IQR) | 15 (8–26) | 12 (6–23) | 6.5 (4–9) | 0.014 |

| Number of days of subsequent oral antibiotic treatment per patient, median (IQR) | 0 (0–3) | 1 (0–3) | 3 (1.25–5.75) | 0.228 |

| Length of hospital stay per patient (days), median (IQR) | 13 (7–24) | 12 (8–25) | 9 (5–15) | 0.873 |

| Restarted iv antibiotic treatment per patient, n (%) | ||||

| overall during the same hospitalization | 13 (8.0) | 22 (10.2) | 7 (11.1) | 0.465 |

| same diagnosis ≤5 days after stopping iv antibiotic therapy | 4 (2.5) | 8 (3.7) | 2 (3.1) | 0.493 |

| Complications of iv line per patientc, n (%) | 9 (5.6) | 17 (7.9) | 2 (3.1) | 0.372 |

| Deaths, n (%) | ||||

| overall | 13 (8.0) | 15 (7.0) | 1 (1.6) | 0.701 |

| due to the treated infections | 3 (1.9) | 8 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.286 |

| Readmissions within 90 days, n (%) | ||||

| overall | 57 (35.2) | 68 (31.6) | 25 (39.1) | 0.468 |

| due to the treated infections | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0.9) | 1 (1.6) | 0.735 |

| Primary antibiotic, n (%) | ||||

| amoxicillin/clavulanate | 66 (40.7) | 75 (34.9) | 31 (48.4) | 0.245 |

| ceftriaxone | 35 (21.6) | 57 (26.5) | 21 (32.8) | 0.272 |

| piperacillin/tazobactam | 29 (17.9) | 58 (27.0)d | 7 (10.9) | 0.863 |

| cefepime | 16 (9.9) | 0 (0.0)d | 0 (0.0) | |

| meropenem | 6 (3.7) | 9 (4.2) | 1 (1.6) | 0.813 |

IQR, interquartile range.

aOnly first episodes which were switched on the third day of iv therapy.

bDifferences between groups using the Mann–Whitney U-test for non-categorical data and the χ2 test for categorical data comparing all first episodes in the control phase with the intervention phase.

cComplications of iv line: phlebitis, septic and non-septic thrombophlebitis.

dCefepime was not available on the Swiss market in 2007 and usually replaced by piperacillin/tazobactam.

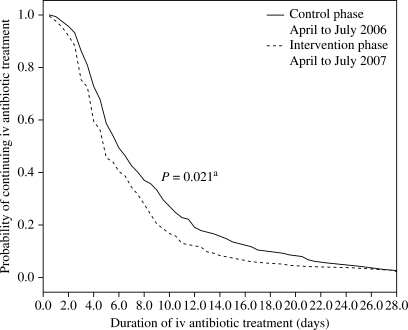

The Kaplan–Meier curve (Figure 3) illustrates that the impact of earlier switching to oral antibiotics on the duration of iv therapy was observed primarily up to the ninth day of antibiotic iv therapy, up to which time the difference between the control and intervention groups continues to increase.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier analysis for the duration of iv antibiotic therapy. aLog-rank test.

The increase in days of oral treatment and the decrease in length of stay were not statistically significant. Nevertheless, there was a trend towards a shorter overall duration of antibiotic treatment from 9.0 to 8.0 days (P = 0.100).

There was no significant difference in the frequency of restarting iv therapy, complications associated with the iv line, mortality rate or readmission rate. All deaths that were due to ID happened during treatment with iv antibiotics. Over the entire year of the intervention, only 2/698 (0.3%, or 1.0% of patients who were switched to oral antibiotics according to our guidelines) failed on oral therapy. One patient with pyelonephritis developed neuropsychiatric side effects related to oral ciprofloxacin. Another patient with E. coli sepsis who was switched to oral ciprofloxacin developed a fever again: further follow-up of the patient revealed the presence of multiple liver abscesses. Both patients recovered after continued iv therapy.

Workload and antibiotic costs and consumption

The total number of applications of iv antibiotics per patient was reduced by 3 (a median of 15–12, adjusted relative reduction of 25%) (11%–36%, P < 0.001). A total of 698 patients received iv antibiotics over the 1 year intervention. Because one application of iv antibiotics takes a mean of 10 min [according to the standardized system of workload measure ‘Leistungserfassung in der Pflege’ (LEP), LEP AG], the estimated total reduction in nurses' workload was 350 h/year, equal to 2 month's salary for a nurse (€5438).

The total costs for antibiotics on the two study wards in the years before the intervention were €240 724 (August 2004 to July 2005) and €280 706 (August 2005 to July 2006). During the year of the intervention, there was a reduction of €13 596 (August 2006 to July 2007) to €267 110. The decrease in costs was achieved primarily during the winter months, i.e. from November 2006 to March 2007. The year after the study (August 2007 to July 2008), the costs decreased again by €23 685 to €243 425.

The highest consumption of oral antibiotics was achieved in the year of the intervention (28.44 DDD/100 bed days) when compared with 21.5 and 27.0 DDD/100 bed days in the 2 years before the study and 27.2 DDD/100 bed days in the year after the study.

The most frequently used antibiotic in our hospital, amoxicillin/clavulanate is available in iv and oral forms. The overall consumption decreased by 4.7% in the study year, although there was a 10.9% increase in the consumption of oral amoxicillin/clavulanate.

Discussion

With a printed checklist available at the patient's bedside as a reminder of the criteria for switching from iv to oral antibiotics, we significantly reduced the duration of iv antibiotic therapy without an increase in complications in unselected patients on medical wards. This reduction in treatment duration was associated with a drop in the workload and the costs of antibiotics. We found that the most frequent switch criteria not met were the absence of clinical improvement or no abatement of fever.

Effectiveness of using the checklist

The checklist proved to be an effective method for reducing the median duration of iv therapy from 6.0 to 5.0 days (−19%), which is comparable to results in other related studies (Table 1). The difference was even more significant if only the first episode of iv antibiotic treatment was being analysed. The overall rate of switching patients to oral antibiotics on the third day of iv therapy was 30%, which was comparable to results noted by Laing et al.14 We chose the third day of treatment as the primary day of the intervention, because at that time the culture results and the initial clinical course allow a reassessment of the treating plan.18,20–23 Nevertheless, many patients were switched earlier according to our criteria.

The effect of the checklist on the duration of iv therapy was probably diluted, because the analysis contained all episodes, including those not fulfilling the switch criteria and patients with infections with strict indication for iv treatment. The effect would have been more notable if only patients fulfilling all switch criteria on the third day of iv therapy in the two groups were compared. However, this was not the aim of our study, and a retrospective evaluation of the inclusion criteria for early switch of the patients in the control phase would have been insufficiently reliable and was therefore not performed.

The rate for switching patients with pneumonia to oral antibiotics was higher (42%), which was comparable to studies where intervention was limited to patients with CAP.11 Consequently, the highest rate of switching patients to oral antibiotics was observed during the winter months (34.9%); this fact emphasizes the importance of controlling for seasonal confounding, which was not done in other studies (Table 1).12,14,17,36 During the intervention phase, a reduction of the duration of iv antibiotics was observed in most subgroups of infections. Nevertheless, the reduction was significant only in the subgroup of lower respiratory tract infections, which may be due to the low number of episodes in most other subgroups. As assumed, there was no reduction in patients with endocarditis or infections of bones or joints, as these patients need to be treated iv for a certain time according to guidelines.

Safety of switching patients from iv to oral antibiotics

There was no significant increase in patient relapse or hospital readmissions during the intervention phase, and all infection-related fatalities occurred in patients who were still being administered iv antibiotics. A meta analysis by Rhew et al.15 showed that in terms of outcome in CAP, switching earlier to oral antibiotics was as effective as continued iv therapy. Therefore, the British and American guidelines for the treatment of CAP40,41 suggest switching early to oral therapy if possible. Comparable results have also been observed for intra-abdominal infections,42–44 anaerobic lung infection45 and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.29,46,47

Recently, some authors have recommended primary therapy or switching to oral therapy in neutropenic patients48–50 under some conditions. Therefore, although it was not suggested by the checklist, physicians also switched to oral antibiotics in 16 patients with neutropenia or haematological malignancies, with successful outcomes.

Criteria against switching to oral antibiotics

Sevinc et al.12 observed a persisting fever in 6% and neutropenia in 1% of patients as the main reason against switching to oral antibiotics; in our study, persisting fever and haematological malignancies or neutropenia were more frequent (41.1% and 21.5%, respectively). This contrast highlights the relevance of co-morbidities in patients, and how important the differences in the case-mix of patients can be in evaluating the criteria for switching to oral antibiotics.

Overall, of 246 cases that met all criteria on the checklist, only 151 (61.1%) patients were switched to oral antibiotics. The adherence to our checklist by physicians on the medical wards increased over the duration of the intervention (from 48% to 68.7%), approaching the rate of general adherence to guidelines in other Swiss hospitals (71%–75%).51,52 If we had actively disseminated the information to physicians, rather than having the checklist available only with the patients’ chart, and had collaborated more closely with other specialists, the adherence rate may have been even higher.53 The increase in the rate of adherence to the checklist criteria by physicians over time emphasizes the relevance of information and teaching in order to rely on switch criteria. In addition, many of the reasons presumed by physicians as appropriate for not switching patients to oral antibiotics were incorrect, as was noted in other studies.54,55 This means that in addition to the printed guidelines themselves, continuing education is crucial.56 The increase in ID consultations at the beginning of the intervention was, perhaps, part of this need for additional help and teaching. During the intervention phase, there was no longer any statistically significant increase, and thus the reduction of iv treatment was not due to additional ID consultations during the intervention phase.

A precise recommendation on how to switch from iv antibiotics with no direct oral equivalent formulation was not offered. The decision was left to the discretion of the physician in charge of the patients. Indeed, we found that patients switched to oral antibiotics on day 3 were initially treated less frequently by an iv formulation which was not available as an oral formulation (e.g. piperacillin/tazobactam or meropenem). This may indicate that, in general, less ill patients were more frequently switched or alternatively, that the physicians in charge were uncertain about which oral antibiotic they could switch patients receiving antibiotics that were not available as an oral formulation to. Consequently, one may speculate that the rate of early switch may be increased by offering precise guidelines regarding which oral antibiotics may be used in specific conditions, or by an ID consultation.

In our study, the need for a physician to consult a clinical pharmacist was rare; there were only 11 consultations in 698 cases (1.6%). Antibiotic stewardship programmes are mainly conducted by ID specialists in Switzerland, in contrast to the USA, where pharmacists can be specially trained in the field of ID.

Effect of switching to oral antibiotics on the workload and antibiotic consumption

The number of hours required for administering iv antibiotics was estimated to be reduced by 350 hours annually on the two study wards. In contrast to studies optimizing antibiotic treatment through consultations with ID specialists57 and studies using laboratory parameters to reduce the duration of antibiotic therapy,58 the implementation of the checklist does not generate additional indirect costs. The checklist criteria may also be used as part of a computerized decision support system with integrated, automatic-reminder procedures,28 which may be as effective as the checklist chosen for this intervention.

The consumption of antibiotics overall in DDD per 100 patient-days was slightly, but not significantly, increased in the study year compared with the previous year. However, the costs were reduced in part because of an increase in the consumption of the cheaper oral application forms by 5%. For the most frequently used antibiotic, amoxicillin/clavulanate, which is available in oral and iv application forms, the increase in the consumption of the oral form was even more impressive (10.9%). To exactly evaluate an intervention, the data must be analysed at an individual level because the consumption at the ward level is influenced by too many other factors, e.g. number of patients in need of iv antibiotics.

Effect of switching to oral antibiotics on length of hospital stay

Various studies have shown that an immediate discharge of the patient from the hospital after stopping iv therapy can be safe.59–62 A reduction in the length of hospital stay is one of the major areas of potential cost savings in using switch criteria;63,64 this has been achieved for patients with lower respiratory tract infections63,65 or other types of infections.64,66 However, like Laing et al.,14 we did not observe an overall reduction in length of hospital stay despite an overall reduction in the duration of iv antibiotic treatment in our study population. One explanation may be the case-mix of patients, which required further diagnostic workup or involved concomitant medical conditions, a possibility corroborated elsewhere in the literature.11,30,60,67

Limitations of the study

There was a difference in the number of observations in the control and intervention phases, which reflects the usual fluctuation of the patient case-mix on general medical wards. It is unlikely that this difference was due to the retrospective analysis of the control phase, because all patients for this phase were selected by using the same criteria that was used for the intervention phase and the patient characteristics were similar in both phases. A selection bias also is unlikely, because all patients were consecutively screened for enrolment for the study.

The results of the intervention may have been less significant if the physicians from the study team had not also been present sometimes on the wards and reminded the physicians in charge of the wards to complete the forms when they forgot to do so. Nevertheless, in most instances in which the checklist was not completed on time and the criteria for switching the patient to oral antibiotics were met, switching was performed before we were able to remind the physician to complete the checklist.

The number of applications of antibiotics per day is influenced partly by what antibiotic is being used and by the renal function in the patient. Therefore, the reduction in the cumulative number of antibiotic applications per patient does not depend only on a reduction in duration of iv antibiotic treatment. Nevertheless, there were no significant differences noted over time in the classes of antibiotics that were administered. The calculation of the workload was an estimate and the precision is therefore limited.

We used a before–after design, of which the main limitations are regression to the mean and inadequate control for confounding. The case-mix was comparable in both phases and we tried to further minimize possible confounding effects by statistical adjustment for possible confounders. A regression to the mean may have influenced the drop of antibiotic costs. A causal interpretation of the results is possible, bearing in mind that other unknown or unmeasured confounders may exist that were not accounted for in this study.

Strengths of the study

To assess the effect of our intervention, the two groups, control and intervention phases, were analysed during the same months in the year to avoid a seasonal bias. The observation period of 1 year was the longest, and the number of patients the highest, of any study to date that has evaluated criteria for switching to oral antibiotics on medical wards. In addition, we have collected data on the safety of switching to oral treatment. Importantly, we have included all patients in the study to evaluate the safety of the checklist and have therefore not excluded patients who are not eligible for an early switch, e.g. patients presenting with infective endocarditis.

Further investigation of various issues may be performed in the future. For example, the checklist may be used as an automatic, computerized reminder if antibiotics are prescribed electronically. In addition, the checklist may be evaluated in other patient populations, e.g. surgical patients. In our hospital, the criteria have been implemented routinely since September 2008 on all Internal Medicine wards.

Conclusions

Our study shows that on general medical wards, a simple, printed checklist with bedside criteria for switching from iv to oral antibiotics can shorten the duration of iv therapy and reduce treatment costs without any negative influence on the outcome of treatment. The criteria were successfully applied to all patients, independently of the indication (whether empirical or treatment of documented infection), the type of (presumed) infection, the underlying disease or the group of antibiotics being used. The setting for our study represents daily medical practice on a general hospital ward, without direct intervention by ID specialists, thus making it possible to generalize the results.

Funding

This study was funded by a non-restricted grant from the ‘Stiftung Forschung Infektionskrankheiten, Basel’, Switzerland. U. F. and M. B. have received grants for the antibiotic stewardship programme from Astra Zeneca AG, Bristol-Myers Squibb SA, GlaxoSmithKline AG, Merck Sharp & Dohme-Chibret AG and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals AG. S. Strom was funded by a non-restricted grant of the Antibiotic Stawardship Programme.

Transparency declarations

None to declare. The authors employed an independent medical writer (Sigrid Strom) to assist in optimising the English language used in the article.

Acknowledgements

An abstract of the data was presented at the Eighteenth European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Barcelona, Spain, 2008 (Abstract no. 1286) and at the Annual Congress of the Swiss Society for Infectious Diseases, Lausanne, Switzerland, 2008 (Abstract no. E82) .

We thank Kristian Schneider for his help in organizing the study on the wards and Sigrid Strom, Seattle, for valuable assistance in editing the manuscript. We also thank all the physicians on the study wards for their excellent cooperation.

References

- 1.Burke JP. Infection control—a problem for patient safety. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:651–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr020557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shlaes DM, Gerding DN, John JF, Jr, et al. Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America and Infectious Diseases Society of America Joint Committee on the Prevention of Antimicrobial Resistance: guidelines for the prevention of antimicrobial resistance in hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:584–99. doi: 10.1086/513766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fridkin SK, Steward CD, Edwards JR, et al. Surveillance of antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance in United States hospitals: project ICARE phase 2. Project Intensive Care Antimicrobial Resistance Epidemiology (ICARE) hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:245–52. doi: 10.1086/520193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gould IM. A review of the role of antibiotic policies in the control of antibiotic resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43:459–65. doi: 10.1093/jac/43.4.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davey P, Brown E, Fenelon L, et al. Systematic review of antimicrobial drug prescribing in hospitals. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:211–6. doi: 10.3201/eid1202.05145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spellberg B, Guidos R, Gilbert D, et al. The epidemic of antibiotic-resistant infections: a call to action for the medical community from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:155–64. doi: 10.1086/524891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petrak RM, Sexton DJ, Butera ML, et al. The value of an infectious diseases specialist. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1013–7. doi: 10.1086/374245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dellit TH, Owens RC, McGowan JE, Jr, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:159–77. doi: 10.1086/510393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramsay C, Brown E, Hartman G, et al. Room for improvement: a systematic review of the quality of evaluations of interventions to improve hospital antibiotic prescribing. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;52:764–71. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rojo D, Pinedo A, Clavijo E, et al. Analysis of risk factors associated with nosocomial bacteraemias. J Hosp Infect. 1999;42:135–41. doi: 10.1053/jhin.1998.0543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramirez JA, Vargas S, Ritter GW, et al. Early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics and early hospital discharge: a prospective observational study of 200 consecutive patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2449–54. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.20.2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sevinc F, Prins JM, Koopmans RP, et al. Early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics: guidelines and implementation in a large teaching hospital. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43:601–6. doi: 10.1093/jac/43.4.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahkee S, Smith S, Newman D, et al. Early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics in hospitalized patients with infections: a 6-month prospective study. Pharmacotherapy. 1997;17:569–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laing RB, Mackenzie AR, Shaw H, et al. The effect of intravenous-to-oral switch guidelines on the use of parenteral antimicrobials in medical wards. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42:107–11. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rhew DC, Tu GS, Ofman J, et al. Early switch and early discharge strategies in patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:722–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.5.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Gunten V, Amos V, Sidler AL, et al. Hospital pharmacists’ reinforcement of guidelines for switching from parenteral to oral antibiotics: a pilot study. Pharm World Sci. 2003;25:52–5. doi: 10.1023/a:1023240829761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLaughlin CM, Bodasing N, Boyter AC, et al. Pharmacy-implemented guidelines on switching from intravenous to oral antibiotics: an intervention study. QJM. 2005;98:745–52. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hci114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacGregor RR, Graziani AL. Oral administration of antibiotics: a rational alternative to the parenteral route. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:457–67. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.3.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Zanten AR, Engelfriet PM, van Dillen K, et al. Importance of nondrug costs of intravenous antibiotic therapy. Crit Care. 2003;7:R184–90. doi: 10.1186/cc2388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pestotnik SL, Classen DC, Evans RS, et al. Implementing antibiotic practice guidelines through computer-assisted decision support: clinical and financial outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:884–90. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-10-199605150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamilton-Miller JM. Switch therapy: the theory and practice of early change from parenteral to non-parenteral antibiotic administration. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1996;2:12–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1996.tb00194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fraser GL, Stogsdill P, Dickens JD, Jr, et al. Antibiotic optimization. An evaluation of patient safety and economic outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1689–94. doi: 10.1001/archinte.157.15.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hitt CM, Nightingale CH, Quintiliani R, et al. Streamlining antimicrobial therapy for lower respiratory tract infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24(Suppl 2):S231–7. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.supplement_2.s231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duncan RA. Controlling use of antimicrobial agents. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1997;18:260–6. doi: 10.1086/647608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pablos AI, Escobar I, Albinana S, et al. Evaluation of an antibiotic intravenous to oral sequential therapy program. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14:53–9. doi: 10.1002/pds.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ho BP, Lau TT, Balen RM, et al. The impact of a pharmacist-managed dosage form conversion service on ciprofloxacin usage at a major Canadian teaching hospital: a pre- and post-intervention study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5:48. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-5-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez MJ, Freire A, Castro I, et al. Clinical and economic impact of a pharmacist-intervention to promote sequential intravenous to oral clindamycin conversion. Pharm World Sci. 2000;22:53–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1008769204178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fischer MA, Solomon DH, Teich JM, et al. Conversion from intravenous to oral medications: assessment of a computerized intervention for hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2585–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.21.2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Angeli P, Guarda S, Fasolato S, et al. Switch therapy with ciprofloxacin vs. intravenous ceftazidime in the treatment of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients with cirrhosis: similar efficacy at lower cost. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:75–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee RW, Lindstrom ST. Early switch to oral antibiotics and early discharge guidelines in the management of community-acquired pneumonia. Respirology. 2007;12:111–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.00931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fine MJ, Stone RA, Lave JR, et al. Implementation of an evidence-based guideline to reduce duration of intravenous antibiotic therapy and length of stay for patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Med. 2003;115:343–51. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00395-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marrie TJ, Lau CY, Wheeler SL, et al. A controlled trial of a critical pathway for treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. CAPITAL Study Investigators. Community-Acquired Pneumonia Intervention Trial Assessing Levofloxacin. JAMA. 2000;283:749–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.6.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramirez JA, Bordon J. Early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics in hospitalized patients with bacteremic community-acquired Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:848–50. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.6.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oosterheert JJ, Bonten MJ, Schneider MM, et al. Effectiveness of early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics in severe community acquired pneumonia: multicentre randomised trial. BMJ. 2006;333:1193. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38993.560984.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Senn L, Burnand B, Francioli P, et al. Improving appropriateness of antibiotic therapy: randomized trial of an intervention to foster reassessment of prescription after 3 days. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;53:1062–7. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vogtländer NP, Van Kasteren ME, Natsch S, et al. Improving the process of antibiotic therapy in daily practice: interventions to optimize timing, dosage adjustment to renal function, and switch therapy. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1206–12. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.11.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Groot V, Beckerman H, Lankhorst GJ, et al. How to measure comorbidity. A critical review of available methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:221–9. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00585-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.BTS Guidelines for the Management of Community Acquired Pneumonia in Adults. Thorax. 2001;56(Suppl 4):IV1–64. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.suppl_4.iv1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 2):S27–72. doi: 10.1086/511159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Solomkin JS, Reinhart HH, Dellinger EP, et al. Results of a randomized trial comparing sequential intravenous/oral treatment with ciprofloxacin plus metronidazole to imipenem/cilastatin for intra-abdominal infections. The Intra-Abdominal Infection Study Group. Ann Surg. 1996;223:303–15. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199603000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wacha H, Warren B, Bassaris H, et al. Comparison of sequential intravenous/oral ciprofloxacin plus metronidazole with intravenous ceftriaxone plus metronidazole for treatment of complicated intra-abdominal infections. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2006;7:341–54. doi: 10.1089/sur.2006.7.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Starakis I, Karravias D, Asimakopoulos C, et al. Results of a prospective, randomized, double blind comparison of the efficacy and the safety of sequential ciprofloxacin (intravenous/oral) + metronidazole (intravenous/oral) with ceftriaxone (intravenous) + metronidazole (intravenous/oral) for the treatment of intra-abdominal infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;21:49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00248-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fernandez-Sabe N, Carratala J, Dorca J, et al. Efficacy and safety of sequential amoxicillin-clavulanate in the treatment of anaerobic lung infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;22:185–7. doi: 10.1007/s10096-003-0898-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Terg R, Cobas S, Fassio E, et al. Oral ciprofloxacin after a short course of intravenous ciprofloxacin in the treatment of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: results of a multicenter, randomized study. J Hepatol. 2000;33:564–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0641.2000.033004564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tuncer I, Topcu N, Durmus A, et al. Oral ciprofloxacin versus intravenous cefotaxime and ceftriaxone in the treatment of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1426–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vidal L, Paul M, Ben-Dor I, et al. Oral versus intravenous antibiotic treatment for febrile neutropenia in cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;issue 4:CD003992. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003992.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Freifeld A, Marchigiani D, Walsh T, et al. A double-blind comparison of empirical oral and intravenous antibiotic therapy for low-risk febrile patients with neutropenia during cancer chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:305–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907293410501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marra CA, Frighetto L, Quaia CB, et al. A new ciprofloxacin stepdown program in the treatment of high-risk febrile neutropenia: a clinical and economic analysis. Pharmacotherapy. 2000;20:931–40. doi: 10.1592/phco.20.11.931.35258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lutters M, Harbarth S, Janssens JP, et al. Effect of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary, educational program on the use of antibiotics in a geriatric university hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:112–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Di Giammarino L, Bihl F, Bissig M, et al. Evaluation of prescription practices of antibiotics in a medium-sized Swiss hospital. Swiss Med Wkly. 2005;135:710–4. doi: 10.4414/smw.2005.11174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mol PG, Wieringa JE, Nannanpanday PV, et al. Improving compliance with hospital antibiotic guidelines: a time-series intervention analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55:550–7. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schouten JA, Hulscher ME, Natsch S, et al. Barriers to optimal antibiotic use for community-acquired pneumonia at hospitals: a qualitative study. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16:143–9. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.017327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Halm EA, Switzer GE, Mittman BS, et al. What factors influence physicians’ decisions to switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics for community-acquired pneumonia? J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:599–605. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009599.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bero LA, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM, et al. Closing the gap between research and practice: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. The Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Review Group. BMJ. 1998;317:465–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7156.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bugnon-Reber A, de Torrente A, Troillet N, et al. Antibiotic misuse in medium-sized Swiss hospitals. Swiss Med Wkly. 2004;134:481–5. doi: 10.4414/smw.2004.10599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Christ-Crain M, Stolz D, Bingisser R, et al. Procalcitonin guidance of antibiotic therapy in community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:84–93. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200512-1922OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dunn AS, Peterson KL, Schechter CB, et al. The utility of an in-hospital observation period after discontinuing intravenous antibiotics. Am J Med. 1999;106:6–10. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00359-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boyter AC, Stephen J, Fegan PG, et al. Why do patients with infection remain in hospital once changed to oral antibiotics? J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39:286–8. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.2.286b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nathan RV, Rhew DC, Murray C, et al. In-hospital observation after antibiotic switch in pneumonia: a national evaluation. Am J Med. 2006;119:512.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Beumont M, Schuster MG. Is an observation period necessary after intravenous antibiotics are changed to oral administration? Am J Med. 1999;106:114–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00368-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ehrenkranz NJ, Nerenberg DE, Shultz JM, et al. Intervention to discontinue parenteral antimicrobial therapy in patients hospitalized with pulmonary infections: effect on shortening patient stay. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1992;13:21–32. doi: 10.1086/646419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Przybylski KG, Rybak MJ, Martin PR, et al. A pharmacist-initiated program of intravenous to oral antibiotic conversion. Pharmacotherapy. 1997;17:271–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ramirez JA, Srinath L, Ahkee S, et al. Early switch from intravenous to oral cephalosporins in the treatment of hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1273–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hendrickson JR, North DS. Pharmacoeconomic benefit of antibiotic step-down therapy: converting patients from intravenous ceftriaxone to oral cefpodoxime proxetil. Ann Pharmacother. 1995;29:561–5. doi: 10.1177/106002809502900601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fine MJ, Medsger AR, Stone RA, et al. The hospital discharge decision for patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Results from the Pneumonia Patient Outcomes Research Team cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:47–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]