Abstract

Since the discovery of the mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channel (mitoKATP) more than 13 years ago, it has been implicated in the processes of ischemic preconditioning (IPC), apoptosis and mitochondrial matrix swelling. Different approaches have been employed to characterize the pharmacological profile of the channel, and these studies strongly suggest that cellular protection well correlates with the opening of mitoKATP. However, there are many questions regarding mitoKATP that remain to be answered. These include the very existence of mitoKATP itself, its degree of importance in the process of IPC, its response to different pharmacological agents, and how its activation leads to the process of IPC and protection against cell death. Recent findings suggest that mitoKATP may be a complex of multiple mitochondrial proteins, including some which have been suggested to be components of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. However, the identity of the pore-forming unit of the channel and the details of the interactions between these proteins remain unclear. In this review, we attempt to highlight the recent advances in the physiological role of mitoKATP and discuss the controversies and unanswered questions.

Keywords: Mitochondria, Potassium, Ischemic preconditioning, Diazoxide, Glibenclamide, Succinate dehydrogenase, Apoptosis, Reactive oxygen species

1. Introduction

Ischemic heart disease remains a major health problem in the world. Most of the research in this field has focused on finding ways to prevent ischemic injury by increasing blood supply to the myocardial area at risk. However, identification of an autoprotective mechanism known as ischemic preconditioning (IPC) has raised interest that endogenous pathways can be stimulated to protect the heart from ischemic injury [1]. IPC is a mechanism by which brief periods of ischemia produce protection against subsequent longer ischemic periods [1-3]. If specific cellular pathways or proteins can be targeted to stimulate the IPC protective process, the injury from an ischemic insult can be significantly attenuated. Thus, much effort over the past couple of decades has focused on identifying the underlying molecular basis of IPC. These studies have revealed multiple intracellular pathways to mediate IPC. These include the activation of protein kinase C, G-protein receptors, nitric oxide and generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [4-6]. The end-effector molecule(s) targeted by these pathways remain elusive.

Early studies suggested that adenosine triphosphate sensitive potassium channels (KATP channels) may be the common effector in IPC. Since opening of the surface KATP channels results in membrane hyperpolarization and shortens phase 3 of the cardiac action potential, the cardioprotective effects were initially attributed to surface KATP channels [7]. However, Yao and Gross [8] showed that a low dose of bimakalin, which did not shorten the action potential, had a similar cardioprotective effect as higher doses that enhanced action potential shortening. Similar lack of correlation between the extent of action potential shortening and the reduction of infarct size has also been shown with cromakalim and BMS-180448 [9,10]. Furthermore, Grover et al. [11] showed that prevention of action potential shortening by concomitant treatment of dofetilide did not reverse cardioprotective effects of cromakalim. These studies suggested that the opening of the surface KATP channel may not be necessary for the cardioprotection induced in IPC. An alternative mechanism involving the mitochondrial KATP channel (mitoKATP) subsequently emerged as the possible effector of IPC [12,13].

Since early 1990s, K+ selective transport has been widely observed in the mitochondria. A K+ channel activity, with characteristics similar to those of surface KATP channel, was discovered in 1991 [14]. This mitoKATP channel is modulated by a variety of K+ channel openers and inhibitors [13]. Furthermore, these modulators significantly influence mitochondrial function and cell survival, suggesting a link between mitoKATP and protection against ischemic injury. This protective effect of mitoKATP has been demonstrated in several tissues besides the heart, including liver, brain, kidney and gut [15-18].

2. Pharmacology of mitoKATP

Table 1 lists the known activators and inhibitors of mitoKATP. Several of these chemicals are not specific for mitoKATP and can also modulate the activity of the surface KATP channel. We will detail the studies on the role of these chemicals in mitoKATP activity throughout this review.

Table 1.

Modulators of KATP channels and their selectivity toward mitochondrial and surface channels

| mitoKATP | mitoKATP and surface KATP | Surface KATP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Openers | Diazoxide | Cromakalim | P-1075a |

| Nicorandil | Pinacidil | MCC-134b | |

| BMS 191095 | P-1060 | ||

| Sildenafil | |||

| Isoflurane | |||

| EMD60480 | |||

| Aprikalim | |||

| EMD60480 | |||

| Minoxidil Sulfate | |||

| KRN2391 | |||

| Levosimendan | |||

| Blockers | 5-Hydroxydecanoate | Glibenclamide | HMR1098 (1833) |

| MCC-134 | Glipizide | Glimepiridec |

Diazoxide and nicorandil can activate surface KATP channel at high concentrations [90,91]. 5-Hydroxydecanoate can inhibit surface KATP channel at low pH [92].

P-1075 is selective for surface KATP channel in rabbit myocytes [29]. In isolated rat mitochondria, it activated mitoKATP [93].

MCC-134 selectively activates surface KATP and inhibits mitoKATP [32].

Glimepiride inhibits surface KATP without any effect on cardioprotection [94].

3. Evidence for the existence of mitoKATP

3.1. Studies on intact mitochondria

3.1.1. Patch-clamp of mitochondria

In 1991, Inoue et al. [14] identified the mitoKATP channel in single channel patch-clamp recordings of rat liver mitochondrial inner membrane. Although the technique used is challenging and subject to the criticism that the mitochondrial preparation may have been contaminated with surface proteins, this study remains a compelling argument for the existence of mitoKATP. These authors identified a single K+ selective channel, which was inhibited by ATP with a Ki of ∼0.8 mM when applied to the matrix face of the channel. The channel displayed a lower unitary conductance compared with the surface KATP channel (10 pS in 100 mM matrix K+ and 33 mM cytosolic K+). The channel was inhibited by the K+ channel inhibitor 4-aminopyridine and a sulfonylurea, glibenclamide at 5 μM concentrations. Since the surface KATP channel is sensitive to glibenclamide, this observation was used as additional evidence that the measured conductance was due to a KATP channel. This original report remains one of the only studies thus far directly demonstrating the presence of a mitoKATP channel on intact mitochondrial inner membrane.

3.1.2. Measurement of mitochondrial volume

K+ influx into the mitochondria, accompanied by the movement of water, leads to mitochondrial matrix swelling. The cation flux is tightly regulated to avoid rupture of the mitochondrial membranes. This is accomplished by movement of K+ out of the matrix through the K+/H+ exchanger [19,20]. However, K+ influx by mitoKATP can transiently exceed the counterbalancing activity of the K+/H+ exchanger, resulting in mitochondrial matrix swelling [21]. Garlid's group has used the extent of light scattering at 520 nm to assess the steady-state matrix volume [22]. These studies have supported the results obtained in other systems as far as the effect of different pharmacological agents on mitoKATP. There are limitations associated with this technique, including the use of supraphysiological ion gradients, nucleotide concentrations or metabolic substrates, hypo-osmotic conditions of the experiments to maintain linearity of the response, and the loss of normal cytoskeletal architecture [22,23]. Nevertheless, this approach is advantageous as compared to the reconstitution studies in that the mitochondrial channels and other proteins are intact, and that the pharmacological reagents can be applied directly to the mitochondria.

3.2. Studies on intact myocytes

3.2.1. Flavoprotein oxidation

The autofluorescence properties of the mitochondrial flavoproteins and NADH can be used to monitor mitochondrial redox state in intact cells and tissues [24-26]. The maximum and minimum oxidation states of the mitochondria can be calibrated using an uncoupler (i.e. 2,4-dinitrophenol) and an inhibitor of electron transport, such as cyanide [27]. Opening of mitoKATP results in mild uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation, since the energy that would otherwise be used to produce ATP, gets dissipated. The partial uncoupling would then lead to an increase in flavoprotein fluorescence if the rate of NADH oxidation exceeds the rate of its production. Liu et al. [12] have used this technique to make a connection between mitoKATP activation and cardioprotection in isolated cardiomyocytes. This was the first demonstration of mitoKATP activation by a K+ channel opener (diazoxide) in intact cells. Diazoxide caused the reversible net oxidation of flavoproteins to ∼40% of the completely uncoupled state, with a K1/2 of ∼27 μM, similar to the protective efficacy of diazoxide in intact cells, whole hearts, and animal studies. In these experiments, diazoxide did not activate surface KATP channels, and 5-HD reversed its effects on redox state, providing important support that mitoKATP channels are involved.

Several studies have been reported since the initial report by Liu et al. on the pharmacology and regulation of mitoKATP using the flavoprotein oxidation technique [6,28-32]. These studies support the previous results from isolated mitochondria as far as the selectivity of K+ channel modulators for the mitoKATP vs. the surface isoform. One exception to this rule is the pinacidil derivative P-1075, which was found to be quite selective in isolated cells, but activates mitoKATP in mitochondrial preparations [29].

There have been reports by several groups discussing limitations associated with this technique. These issues have been reviewed recently, and will not be detailed here [33]. However, it should be mentioned that partial oxidation of the flavoprotein pool may not represent a significant change in the mitochondrial membrane potential under oxygenated conditions. In order to better understand the degree of mitochondrial uncoupling by the opening of mitoKATP, the change in oxygen consumption has been studied (see below).

3.2.2. Effects of mitoKATP on respiration and membrane potential

Induction of IPC or treatment with diazoxide or adenosine in C2C12 skeletal myoblast cells leads to stimulation of cellular oxygen consumption, a small decrease in ΔΨm and reduction of cellular ATP levels [34]. These changes, which are consistent with mild uncoupling, were reversed by 5-HD, suggesting a link between IPC and the uncoupling effects. A recent report on isolated rat skeletal muscle mitochondria and L6 myoblast cells, supports these results [35]. The rate of respiration in both systems was increased in response to diazoxide and nicorandil in a saturable and concentration dependent manner. These reagents caused a small change in K+ specific depolarization of ΔΨm (∼8 mV with diazoxide and 4 mV with nicorandil), and this was completely reversed by glibenclamide and partially by 5-HD. Furthermore, both diazoxide and nicorandil caused a K+ specific oxidation of the NADH redox pool with K1/2's of less than 50 μM.

Why would the opening of mitoKATP channel cause a change in respiration and ΔΨm? In theory, the opening of the channel would contribute to an inward current and would lead to the utilization of a portion of the proton gradient to export K+ ions through the K+/H+ exchanger. These effects would cause a partial dissipation of the energy stored as the proton motive force. This uncoupling effect would then lead an increase in proton pumping and consumption of oxygen to maintain ΔΨm. However, since opening of mitoKATP causes only a small change in K+ concentrations in the mitochondria, other nonspecific effects of mitoKATP openers can mask their effects on respiration. Diazoxide has been shown to inhibit succinate-supported respiration by inhibiting succinate dehydrogenase (Complex II) without affecting NADH-supported respiration [36,37]. Thus, when NADH-linked substrates are used, mitochondrial oxygen consumption is increased by ∼20% in the heart and liver [38] and ∼50% in the brain [35,39] (due to higher levels of mitoKATP in the brain). These changes represent the uncoupling effects of mitoKATP. However, the nonspecific effects of diazoxide remain a controversial issue when it comes to studying the effects of this drug on metabolism as a whole.

3.3. Reconstitution studies on mitoKATP

3.3.1. Lipid bilayer studies

In the 1980s, several groups observed K+ channel activity of proteins purified from mitochondrial membranes and reconstituted into bilayer lipid membranes (BLM) [40,41]. In 1992, Paucek et al. [42] showed K+ channel activity with a conductance of ∼30 pS in a highly purified mitochondrial fraction. However, a very high concentration of K+ (1 M KCl) was used in these studies. A subsequent study from the same lab suggested that modulation of the mitoKATP channel by ATP, GTP and palmitoyl coA was polarized, and the regulatory site was proposed to be on the cytosolic face of the channel [43].

The group of Mironova and Marinov have also studied mitoKATP activity in BLM. A 55 kDa protein was isolated using an ethanol/water method and was shown to confer mitoKATP activity in BLM [44-46]. This protein has not yet been identified. Nevertheless, the channel showed increased activity and reduced selectivity in the presence of the reducing agents, dithiothreitol at 1–3 mM. The channel is inhibited by ATP and is activated by GTP. A recent report demonstrated K+ channel activity in BLM with a conductance of 56 pS in 150 mM KCl [4]. The channel was modulated by ATP and GTP when they were added to the matrix side of the bilayer. Furthermore, diazoxide activated, while 5-HD and glibenclamide inhibited the channel. In contrast to the earlier report mentioned above [44], these authors observed activation of the channel by exogenously generated superoxide, and this activation was reversed by pretreatment with a thiol reducing agent or 5-HD.

3.3.2. Proteoliposome studies

Work from the laboratory of Garlid, using reconstituted proteoliposomes, has significantly contributed to our understanding of the regulation of mitoKATP [39,42,43,47,48]. The technique involves formation of proteoliposomes containing the protein(s) of interest with the fluorescent K+ indicator, PBFI, trapped inside the vesicles [49]. Upon transport of K+, the excitation peak of PBFI narrows, and the rate of fluorescence increase can be used as a measure of K+ transport into the proteoliposomes. A permeable anion such as SCN− or a pH gradient can be used to facilitate K+ transport and compensate for the charge gradient produced by the transport of the cation. The proteins that constitute the mitoKATP channel were affinity purified on an ATP-binding column, and were shown to have sizes of about 55 and 63 kDa [39,42]. The larger band was reported to specifically bind to fluorescent glibenclamide [39]. However, since the initial report of partial purification of these proteins in early 1990s, their identities remain elusive.

This method has been used extensively to study the regulation of the mitoKATP channel by different reagents. The channel was inhibited in a Mg2+-dependent fashion by ATP (Ki ∼ 40 μM). ADP and glibenclamide inhibited the channel with Kis of 280 and 3.1 μM, respectively [42]. The channel was also modulated by GTP, GDP, palmitoyl or oleyl-coA and the alkylating agent DCCD [48]. It was highly selective for K+ over Na+ and had a Km for K+ of 32 mM.

This system has allowed a direct comparison of mitoKATP and surface KATP channels. Diazoxide is about 2000-fold more potent in opening the mitoKATP channel compared with the surface KATP channel [47]. Furthermore, the effect of diazoxide is blocked by 5-HD (Ki of 45–85 μM) and glibenclamide (Ki of 1–6 μM). It should be noted that glibenclamide, but not 5-HD, can also inhibit mitoKATP activated by removing ATP or Mg2+. Cromakalim and two of its derivatives, EMD60480 and EMD57970 were also demonstrated to activate the channel, however, they proved not to be selective for the mitochondrial isoform.

4. Controversies regarding mitoKATP

4.1. Lack of molecular identity

Despite the critical role mitoKATP plays in IPC and apoptosis, its molecular identity remains unclear. The surface KATP channels are thought to be composed of a tetramer of inward rectifier K+ channels (Kir6.x) surrounded by four subunits of sulfonylurea receptors (SUR) [50-53]. The SUR subunits confer sensitivity to glibenclamide and many KATP channel modulators [54,55]. Based on similarities between mitoKATP and surface KATP channels, it has been proposed that mitoKATP may also consist of Kir and SUR subunits.

In support of this hypothesis, Garlid's group has purified a mitochondrial fraction containing a 63 kDa sulfonylurea binding protein and a putative pore-forming subunit of 55 kDa in size [39,42]. When reconstituted in proteoliposomes, the purified mitochondrial fraction confers ATP-sensitive potassium channel activity. This fraction was purified by applying mitochondrial extracts from the heart to a DEAE-cellulose column followed by further purification on an ATP column. Similar size proteins have been isolated from the brain and liver mitochondria [39]. The 63 kDa protein from brain was recently reported to bind to labeled glyburide, supporting that idea that this protein may be the sulfonylurea binding subunit of the mitoKATP channel [39].

Other groups have also attempted to identify a sulfonylurea binding protein in the mitochondria. Suzuki et al. [56] reported that a Kir6.1 antibody immunolocalizes to the mitochondria and binds to a 51 kDa protein in mitochondrial membrane preparations. In another study, a dominant negative Kir6.1 adenovirus, in which the pore signature sequence GFG was mutated to AFA, was constructed and infected into adult myocytes [57]. This construct had no effect on diazoxide activated mitochondrial redox state, indicating that the mitochondria probably do not contain a Kir6.1. However, the authors suggested that it is still possible that a mitochondrial Kir6.1 could exist, that does not heteromultimerize with the dominant negative form of Kir6.1, hence the lack of any effect by the adenovirus. Other recent studies also suggest that Kir6.1, Kir6.2 and SUR2A subunits are present in the mitochondria of the heart and brain [58,59]. The antibodies against Kir6.1 and Kir6.2 recognized proteins of 48 and 40 kDa in size in a mitochondrial preparation, but it remains to be proven if these antibodies are binding to a kin-like protein. Knockout of kir6.1 gene in intact mice, does not disrupt mitoKATP opening, but results in sudden death associated with Printz-metal's angina and vasospasm [60].

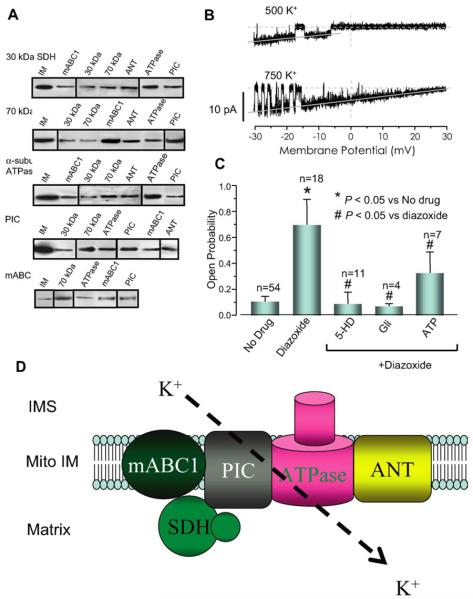

As discussed above, diazoxide is also capable of inhibiting SDH [61]. Other SDH inhibitors, malonate and 3-nitropropionic acid (3-NPA), have also been shown to attenuate oxidant stress on the heart and have cardioprotective effects [62-64]. These observations have led to the alternative hypothesis that respiratory inhibition, rather than K+ channel activation, underlies IPC [36,37]. The pharmacological overlap between SDH and mitoKATP led to the hypothesis that SDH and mitoKATP interact with each other, both physically and functionally [65]. Using co-immunoprecipitation technique, Ardehali et al. [65] identified at least four mitochondrial proteins that interact with SDH (Fig. 1A). These proteins are the following: mitochondrial ATP-binding cassette protein-1 (mABC1), adenine nucleotide translocator (ANT), ATP synthase (ATPase) and inorganic phosphate carrier (PIC). A mitochondrial fraction containing these five proteins displayed K+ channel activity when incorporated into liposomes and lipid bilayer (Fig. 1B). The channel activity also responded appropriately to mitoKATP modulators, ATP, glibenclamide, 5-HD and diazoxide (Fig. 1C). In order to better link the mitochondrial complex to the mitoKATP channel activity, pharmacological agents that target SDH (3-NPA and malonate) were also tested. The addition of these compounds resulted in a significant increase in the mitoKATP channel activity, suggesting that SDH, a member of the inner membrane multiprotein complex, influences mitoKATP activity. It was also shown that ANT modulators did not have an effect on mitoKATP activity, arguing against a role for ANT in the mitoKATP channel pore. These data reconcile the controversy over the basis of IPC by demonstrating that SDH may be a component of mitoKATP, as part of a novel macromolecular supercomplex, and provide the first tangible clue as to the structural basis of mitoKATP channels (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Evidence for physical and functional interaction between SDH and mitoKATP. (A) Co-immunoprecipitation studies revealed that the 30- and 70-kDa components of SDH interact with four mitochondrial proteins: mABC1, ANT, ATPase and PIC. (B) Unitary K+ currents were recorded in lipid planar bilayers after fusion of native microsomes from a partially purified mitochondrial fraction containing the mABC1-SDH-PIC-ANT-ATPase protein complex. (C) The channel activity was increased by diazoxide, and the diazoxide activated channel activity was inhibited by 5-HD, glibenclamide and ATP. (D) Schematic presentation of the proteins associated with mitoKATP activity. The complex containing SDH-PIC-mABC1-ATPase-ANT is capable of transporting K+ with characteristics similar to those of mitoKATP. The pore-forming unit of the channel has not been characterized yet. Gli, glibenclamide; IMS, intermembrane space; Mito IM, mitochondrial inner membrane.

4.2. Nonselectivity for K+ by diazoxide

A recent paper by Terzic's group suggested that diazoxide may not display K+ selectivity in the mitochondria from rat hearts [62]. They found that the levels of ROS produced by isolated mitochondria are reduced by diazoxide and nicorandil in reperfused hearts after 5 min of anoxia. There was also better preservation of the mitochondrial structure and oxidative phosphorylation, and these effects were all reversed by 5-HD. These beneficial effects were also observed in a K+-free medium, suggesting that K+ selective channels may not be required for the protective effects diazoxide or nicorandil.

4.3. Possible independence of protection and depolarization of ΔΨm

As explained above, K+ influx through mitoKATP could lead to partial depolarization of ΔΨm which could in turn decrease the driving force for the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake during ischemia. However, Lawrence et al. [66] recently reported that no change in ΔΨm or flavoprotein oxidation was observed when diazoxide was added under normoxic conditions. However, they observed protection by diazoxide against chemical cell death produced by iodoacetate and cyanide. However, it should be noted that the extent of ΔΨm loss during metabolic inhibition was not examined in this study and it has been argued that diazoxide will induced a marked depolarization under ischemic conditions [67]. Moreover, IPC has been shown to enhance mitochondrial membrane depolarization during ischemia [68], which may contribute to the protective effect.

4.4. Is mitoKATP a trigger or an effector of IPC?

Despite the evidence that strongly suggests that mitoKATP plays a key role in IPC, it is unclear how this channel opens in response to ischemia. Some studies have tried to address the time frame for mitoKATP channel opening and IPC. Fryer et al. [69] administered 5-HD to rats either before or after the preconditioning phase or diazoxide application. In control animals, IPC reduced infarct size significantly. 5-HD applied before IPC reversed the protective effects of IPC, while it did not have any effects on the infarct size in the absence of preconditioning. Administration of diazoxide 15 min before the long ischemia reduced infarct size, and addition of 5-HD either before or after diazoxide administration completely reversed the protective effects. This study suggests that mitoKATP is both a trigger and an effector of IPC. This is in contrast to another study by Pain et al. [70] who showed that the addition of 5-HD or glibenclamide during diazoxide pre-treatment or the preconditioning period blocks the protective effects of IPC. They concluded that mitoKATP may only be a trigger of IPC.

4.5. Role of surface KATP channel

As discussed earlier, pharmacological studies argue against a role for the surface KATP channel in the process of IPC. This issue was recently readdressed in Kir6.2 knockout mice [71,72]. The knockout mice displayed a blunted response to IPC, and their hearts went into contracture within 5 min of exposure to ischemia and did not recover function during reperfusion. This ischemic response was similar to the effect of treating wild-type mice with HMR1098. In the absence of preconditioning, the knockout mice displayed more significant damage in response to ischemia then wild-type animals suggesting that the surface KATP channel may play a role in cardioprotection in mice. In contrast, inhibition of the surface KATP channels with HMR1098 does not seem to have an effect on ischemia or IPC in dogs, rats, rabbits or human myocardium [73-76], indicating a minimal role for sarcolemmal KATP activation in cardioprotection in large animals.

5. Mechanism of protection

Despite efforts by several groups, the mechanism of protection induced by the opening of mitoKATP remains unclear. There are three major hypotheses that have emerged as a result of investigation in this area. Although these hypotheses raise different mechanisms for IPC, they are probably not mutually exclusive, and they may all contribute to this process.

5.1. Changes in the mitochondrial Ca2+ levels

The hypothesis that mitoKATP opening leads to an attenuation of Ca2+ accumulation during IPC was first proposed by Liu et al. [12] in 1998. Subsequent pharmacological studies suggested that diazoxide and pinacidil reduced the magnitude of Ca2+ uptake, and it was reversed by 5-HD [77]. It was proposed that this effect could be through a partial depolarization (in the magnitude of ∼10–24 mV) of ΔΨm in response to mitoKATP openers. Wang et al. [78] has shown that mitoKATP opening attenuates the mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation during ischemia in intact hearts. Similar observations were reported by Murata et al. [79] who showed that mitoKATP opening attenuated mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation during ischemia. In this study, PTP opening was also shown to be attenuated by a reduction in Ca2+ accumulation in the mitochondria. A recent report found that diazoxide caused a depolarization of ΔΨm under anoxic conditions, and a decrease in the mitochondrial Ca2+ loading, which resulted in protection of isolated mitochondria [67]. They also reported that this process prevented a mitochondrial permeability transition with reoxygenation, which could explain the antiapoptotic effects of mitoKATP opening.

5.2. Mitochondrial matrix swelling and changes in ATP synthesis

Matrix swelling of isolated mitochondria has long been used as an assay of mitoKATP opening [22]. Recently, Halestrap's group has used 3H2O and [14C]sucrose to measure mitochondrial volume [36]. Their studies showed that 50 μM diazoxide and two 5-min cycles of preconditioning increased matrix volume by 88% and 58%, respectively. 5-HD not only did not reverse this process, it also increased matrix volume when it was solely added. They also reported that in the mitochondria isolated prior to ischemia, IPC increased state 3 respiration by 2-oxyglutarate or succinate, but had no effect on ascorbate + TMPD, and that diazoxide inhibited state 3 respiration of 2-oxyglutarate by 22%, slightly inhibited that of succinate, but not that of ascorbate + TMPD. However, in mitochondria isolated after 30 min of ischemia, state 3 respiration was inhibited in all groups relative to preischemic mitochondria when oxyglutarate, succinate or ascorbate + TMPD were used as substrate. Diazoxide increased respiration in this group, but 5-HD did not reverse this effect, and actually resulted in an increase in respiration by itself. Respiration partially recovered in the mitochondria that were isolated after reperfusion when compared with the end-ischemic group, and diazoxide did not add any additional effect. This study suggests that protection may not correlate with changes in matrix volume and respiration. However, it should be mentioned that the isolated mitochondria were studied in vitro, under conditions that differ from their native milieu, thus, it is difficult to extrapolate these results to the situation in the intact heart.

Kowaltowski et al. [38] proposed an alternative explanation for protection induced by mitochondrial swelling. According to their model, matrix swelling results in the inner and outer mitochondrial membranes coming closer to each other, which may lead to optimized contact between membrane and channel proteins on the inner and outer membranes. This may then result in an increase in ADP transport and ATP synthesis.

Isolated mitochondria from preconditioned or diazoxide treated hearts were also studied by Fryer et al. [75]. Ischemic reperfusion resulted in a decrease in ATP synthesis which was reversed by IPC. Diazoxide displayed protective effects but did not reverse the decline in ATP synthesis. Another study showed that mitochondria isolated from the chronically hypoxemic rabbit hearts displayed increased basal ATP synthesis rate, which was not changed by Bimkalim treatment, but was reversed by 5-HD and glibenclamide [80]. These observations suggest that mitoKATP channels may remain open in chronic hypoxemia, which could provide resistance to ischemia.

5.3. Changes in the ROS levels

ROS plays a double edge role in the process of IPC. The ROS that is produced during the preconditioning phase is thought to be protective. Several studies have shown that mitoKATP opening increases ROS production [70,81,82], which leads to PKC-dependent protection [83]. This process is reversed by the addition of ROS scavengers [81]. However, the ROS that is generated during reperfusion, which can be suppressed by mitoKATP openers, can cause cell death [62,84,85]. Thus, it is thought that mitoKATP opening increases production of protective ROS during preconditioning and decreases the levels of ROS produced during reperfusion [33].

6. mitoKATP and apoptosis

It is widely believed that apoptosis contributes to ischemia-mediated myocardial cell death and that IPC may decrease both apoptosis and necrosis. Takashi et al. [86] showed that diazoxide pretreatment decreased markers of apoptosis from ischemia/reperfusion injury, and that this effect was reversed by 5-HD. Akao et al. [87] recently showed that diazoxide inhibits H2O2-induced apoptosis in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes, and that 5-HD blocks this effect. In their study, they assessed apoptosis by measuring cytochrome c release, caspase activation, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and cleavage of poly (ADP-ribose)polymerase. These authors later identified three distinct phases in H2O2-induced mitochondrial membrane potential loss and cell death in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes [88]. In the first phase (called the priming phase), there is a calcium-dependent morphological changes with preserved membrane potential, while in the second phase (called the depolarization phase), PTP opening leads to rapid depolarization of the membrane. These two phases are followed by cell fragmentation. Diazoxide decreased the probability of cells undergoing the priming phase, while the PTP opener (cyclosporine A) slowed the process of ΔΨm depolarization and blunted its severity. These results suggest that: 1) mitoKATP plays a protective role in apoptosis, 2) apoptosis (at least in H2O2-induced form) is composed of three distinct phases, and 3) mitoKATP is involved in protection against early stages of apoptosis by preserving mitochondrial integrity.

7. Conclusions

Since its discovery more than 13 years ago, several studies have confirmed that mitoKATP is a key player in the process of IPC. Pharmacological evidence for mitoKATP is based on multiple, and structurally distinct, modulators of the channel. Thus, these studies all support the notion that protection is well correlated with effects on the mitoKATP. However, the selectivity of the tested compounds for mitoKATP remains an issue to be resolved by further investigation.

A significant recent finding in this field is the discovery of a macromolecular complex in the inner membrane of the mitochondria with mitoKATP channel activity. This complex consists of (at least) five proteins in the mitochondrial inner membrane, and transports K+ with characteristics similar to those of native mitoKATP, providing a tangible clue regarding the molecular identity of this channel. These results also link SDH to mitoKATP activity for the first time. Nevertheless, the identity of the pore-forming unit of the channel still remains to be determined. In light of recent evidence linking mitoKATP activation to the inhibition of apoptosis and the permeability transition pore [87,89], the close proximity of mitoKATP and the putative components of the PTP suggest the possibility of a direct functional connection between these processes and new directions for future investigation.

References

- 1.Kloner RA, Bolli R, Marban E, Reinlib L, Braunwald E. Medical and cellular implications of stunning, hibernation, and preconditioning: an NHLBI workshop. Circulation. 1998;97:1848–67. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.18.1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murry CE, Jennings RB, Reimer KA. Preconditioning with ischemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation. 1986;74:1124–36. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.5.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen MV, Baines CP, Downey JM. Ischemic preconditioning: from adenosine receptor of KATP channel. Annu Rev Physiol. 2000;62:79–109. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.62.1.79. In Process Citation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang DX, Chen YF, Campbell WB, Zou AP, Gross GJ, Li PL. Characteristics and superoxide-induced activation of reconstituted myocardial mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Circ Res. 2001;89:1177–83. doi: 10.1161/hh2401.101752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sato T, O'Rourke B, Marban E. Modulation of mitochondrial ATP-dependent K+ channels by protein kinase C. Circ Res. 1998;83:110–4. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sasaki N, Sato T, Ohler A, O'Rourke B, Marban E. Activation of mitochondrial ATP-dependent potassium channels by nitric oxide. Circulation. 2000;101:439–45. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noma A. ATP-regulated K+ channels in cardiac muscle. Nature. 1983;305:147–8. doi: 10.1038/305147a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yao Z, Gross GJ. Effects of the KATP channel opener bimakalim on coronary blood flow, monophasic action potential duration, and infarct size in dogs. Circulation. 1994;89:1769–75. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.4.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grover GJ, D'Alonzo AJ, Parham CS, Darbenzio RB. Cardioprotection with the KATP opener cromakalim is not correlated with ischemic myocardial action potential duration. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1995;26:145–52. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199507000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grover GJ, D'Alonzo AJ, Hess T, Sleph PG, Darbenzio RB. Glyburide-reversible cardioprotective effect of BMS-180448 is independent of action potential shortening. Cardiovasc Res. 1995;30:731–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grover GJ, D'Alonzo AJ, Dzwonczyk S, Parham CS, Darbenzio RB. Preconditioning is not abolished by the delayed rectifier K+ blocker dofetilide. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H1207–H1214. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.3.H1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y, Sato T, O'Rourke B, Marban E. Mitochondrial ATP-dependent potassium channels: novel effectors of cardioprotection? Circulation. 1998;97:2463–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.24.2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grover GJ, Garlid KD. ATP-sensitive potassium channels: a review of their cardioprotective pharmacology. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:677–95. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inoue I, Nagase H, Kishi K, Higuti T. ATP-sensitive K+ channel in the mitochondrial inner membrane. Nature. 1991;352:244–7. doi: 10.1038/352244a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oldenburg O, Cohen MV, Yellon DM, Downey JM. Mitochondrial K(ATP) channels: role in cardioprotection. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;55:429–37. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00439-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Rourke B. Myocardial K(ATP) channels in preconditioning. Circ Res. 2000;87:845–55. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.10.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gross GJ, Fryer RM. Sarcolemmal versus mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ channels and myocardial preconditioning. Circ Res. 1999;84:973–9. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.9.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCully JD, Levitsky S. The mitochondrial K(ATP) channel and cardioprotection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:S667–73. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04689-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brierley GP, Jurkowitz M, Chavez E, Jung DW. Energy-dependent contraction of swollen heart mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:7932–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garlid KD, Paucek P. The mitochondrial potassium cycle. IUBMB Life. 2001;52:153–8. doi: 10.1080/15216540152845948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szewczyk A, Mikolajek B, Pikula S, Nalecz MJ. Potassium channel openers induce mitochondrial matrix volume changes via activation of ATP-sensitive K+ channel. Pol J Pharmacol. 1993;45:437–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaburek M, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Paucek P, Garlid KD. State-dependent inhibition of the mitochondrial KATP channel by glyburide and 5-hydroxydecanoate. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13578–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garlid KD, Beavis AD. Evidence for the existence of an inner membrane anion channel in mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;853:187–204. doi: 10.1016/0304-4173(87)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hassinen I, Chance B. Oxidation–reduction properties of the mitochondrial flavoprotein chain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1968;31:895–900. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(68)90536-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chance B. The kinetics of flavoprotein and pyridine nucleotide oxidation in cardiac mitochondria in the presence of calcium. FEBS Lett. 1972;26:315–9. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(72)80601-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chance B, Salkovitz IA, Kovach AG. Kinetics of mitochondrial flavoprotein and pyridine nucleotide in perfused heart. Am J Physiol. 1972;223:207–18. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1972.223.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romashko DN, Marban E, O'Rourke B. Subcellular metabolic transients and mitochondrial redox waves in heart cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1618–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu H, Sato T, Seharaseyon J, Liu Y, Johns DC, O'Rourke B, Marban E. Pharmacological and histochemical distinctions between molecularly defined sarcolemmal KATP channels and native cardiac mitochondrial KATP channels. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;55:1000–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato T, Sasaki N, Seharaseyon J, O'Rourke B, Marban E. Selective pharmacological agents implicate mitochondrial but not sarcolemmal K(ATP) channels in ischemic cardioprotection. Circulation. 2000;101:2418–23. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.20.2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seharaseyon J, Ohler A, Sasaki N, Fraser H, Sato T, Johns DC, O'Rourke B, Marban E. Molecular composition of mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channels probed by viral Kir gene transfer. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:1923–30. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sato T, Sasaki N, O'Rourke B, Marban E. Adenosine primes the opening of mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channels: a key step in ischemic preconditioning? Circulation. 2000;102:800–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.7.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sasaki N, Murata M, Guo Y, Jo SH, Ohler A, Akao M, O'Rourke B, Xiao RP, Bolli R, Marban E. MCC-134, a single pharmacophore, opens surface ATP-sensitive potassium channels, blocks mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channels, and suppresses preconditioning. Circulation. 2003;107:1183–2118. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000051457.64240.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Rourke B. Evidence for mitochondrial K+ channels and their role in cardioprotection. Circ Res. 2004;94:420–32. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000117583.66950.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Minners J, van den Bos EJ, Yellon DM, Schwalb H, Opie LH, Sack MN. Dinitrophenol, cyclosporin A, and trimetazidine modulate preconditioning in the isolated rat heart: support for a mitochondrial role in cardioprotection. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;47:68–73. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Debska G, Kicinska A, Skalska J, Szewczyk A, May R, Elger CE, Kunz WS. Opening of potassium channels modulates mitochondrial function in rat skeletal muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1556:97–105. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(02)00340-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lim KH, Javadov SA, Das M, Clarke SJ, Suleiman MS, Halestrap AP. The effects of ischaemic preconditioning, diazoxide and 5-hydroxydecanoate on rat heart mitochondrial volume and respiration. J Physiol. 2002;545:961–74. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.031484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hanley PJ, Mickel M, Loffler M, Brandt U, Daut J. K(ATP) channel-independent targets of diazoxide and 5-hydroxydecanoate in the heart. J Physiol. 2002;542:735–41. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.023960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kowaltowski AJ, Seetharaman S, Paucek P, Garlid KD. Bioenergetic consequences of opening the ATP-sensitive K(+) channel of heart mitochondria. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H649–H657. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.2.H649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bajgar R, Seetharaman S, Kowaltowski AJ, Garlid KD, Paucek P. Identification and properties of a novel intracellular (mitochondrial) ATP-sensitive potassium channel in brain. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33369–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103320200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mironova GD, Fedotcheva NI, Makarov PR, Pronevich LA, Mironov GP. Protein from beef heart mitochondria inducing the potassium channel conductivity of bilayer lipid membrane. Biofizika. 1981;26:451–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diwan JJ, Haley T, Sanadi DR. Reconstitution of transmembrane K+ transport with a 53 kDa mitochondrial protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;153:224–30. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)81212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paucek P, Mironova G, Mahdi F, Beavis AD, Woldegiorgis G, Garlid KD. Reconstitution and partial purification of the glibenclamide-sensitive, ATP-dependent K+ channel from rat liver and beef heart mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:26062–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yarov-Yarovoy V, Paucek P, Jaburek M, Garlid KD. The nucleotide regulatory sites on the mitochondrial KATP channel face the cytosol. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1321:128–36. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(97)00051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grigoriev SM, Skarga YY, Mironova GD, Marinov BS. Regulation of mitochondrial KATP channel by redox agents. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1410:91–6. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00179-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marinov BS, Grigoriev SM, Skarga Y, Olovjanishnikova GD, Mironova GD. Effects of pelargonidine and a benzocaine analogue p-diethylaminoethyl benzoate on mitochondrial K(ATP) channel. Membr Cell Biol. 2001;14:663–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mironova GD, Skarga YY, Grigoriev SM, Negoda AE, Kolomytkin OV, Marinov BS. Reconstitution of the mitochondrial ATP-dependent potassium channel into bilayer lipid membrane. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1999;31:159–63. doi: 10.1023/a:1005408029549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garlid KD, Paucek P, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Murray HN, Darbenzio RB, D'Alonzo AJ, Lodge NJ, Smith MA, Grover GJ. Cardioprotective effect of diazoxide and its interaction with mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Possible mechanism of cardioprotection. Circ Res. 1997;81:1072–82. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.6.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paucek P, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Sun X, Garlid KD. Inhibition of the mitochondrial KATP channel by long-chain acyl-CoA esters and activation by guanine nucleotides. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32084–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jezek P, Orosz DE, Garlid KD. Reconstitution of the uncoupling protein of brown adipose tissue mitochondria. Demonstration of GDP-sensitive halide anion uniport. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:19296–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aguilar-Bryan L, Nichols CG, Wechsler SW, Clement JPt, Boyd AE, 3rd, Gonzalez G, Herrera-Sosa H, Nguy K, Bryan J, Nelson DA. Cloning of the beta cell high-affinity sulfonylurea receptor: a regulator of insulin secretion. Science. 1995;268:423–6. doi: 10.1126/science.7716547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Clement JP, Wang CZ, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J, Seino S. A family of sulfonylurea receptors determines the pharmacological properties of ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Neuron. 1996;16:1011–7. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Inagaki N, Tsuura Y, Namba N, Masuda K, Gonoi T, Horie M, Seino Y, Mizuta M, Seino S. Cloning and functional characterization of a novel ATP-sensitive potassium channel ubiquitously expressed in rat tissues, including pancreatic islets, pituitary, skeletal muscle, and heart. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:5691–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.11.5691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Clement JPt, Namba N, Inazawa J, Gonzalez G, Aguilar-Bryan L, Seino S, Bryan J. Reconstitution of IKATP: an inward rectifier subunit plus the sulfonylurea receptor. Science. 1995;270:1166–70. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Babenko AP, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J. A view of sur/KIR6.X, KATP channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 1998;60:667–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seino S. ATP-sensitive potassium channels: a model of heteromultimeric potassium channel/receptor assemblies. Annu Rev Physiol. 1999;61:337–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Suzuki M, Kotake K, Fujikura K, Inagaki N, Suzuki T, Gonoi T, Seino S, Takata K. Kir6.1: a possible subunit of ATP-sensitive K+ channels in mitochondria. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;241:693–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seharaseyon J, Sasaki N, Ohler A, Sato T, Fraser H, Johns DC, O'Rourke B, Marban E. Evidence against functional heteromultimerization of the KATP channel subunits Kir6.1 and Kir6.2. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17561–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.23.17561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lacza Z, Snipes JA, Kis B, Szabo C, Grover G, Busija DW. Investigation of the subunit composition and the pharmacology of the mitochondrial ATP-dependent K+ channel in the brain. Brain Res. 2003;994:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lacza Z, Snipes JA, Miller AW, Szabo C, Grover G, Busija DW. Heart mitochondria contain functional ATP-dependent K+ channels. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:1339–47. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miki T, Suzuki M, Shibasaki T, Uemura H, Sato T, Yamaguchi K, Koseki H, Iwanaga T, Nakaya H, Seino S. Mouse model of Prinzmetal angina by disruption of the inward rectifier Kir6.1. Nat Med. 2002;8:466–72. doi: 10.1038/nm0502-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schafer G, Wegener C, Portenhauser R, Bojanovski D. Diazoxide, an inhibitor of succinate oxidation. Biochem Pharmacol. 1969;18:2678–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ozcan C, Bienengraeber M, Dzeja PP, Terzic A. Potassium channel openers protect cardiac mitochondria by attenuating oxidant stress at reoxygenation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H531–H539. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00552.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ockaili RA, Bhargava P, Kukreja RC. Chemical preconditioning with 3-nitropropionic acid in hearts: role of mitochondrial K(ATP) channel. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H2406–H2411. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.5.H2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Horiguchi T, Kis B, Rajapakse N, Shimizu K, Busija DW. Opening of mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channels is a trigger of 3-nitropropionic acid-induced tolerance to transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Stroke. 2003;34:1015–20. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000063404.27912.5B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ardehali H. AHA Scientific conference on molecular mechanisms of growth, death, and regeneration in the myocardium: basic biology and insights into ischemic heart disease and heart failure. Snowbird; Utah: 2003. Succinate dehydrogenase modulates mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ channel activity as part of a macromolecular complex. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lawrence CL, Billups B, Rodrigo GC, Standen NB. The KATP channel opener diazoxide protects cardiac myocytes during metabolic inhibition without causing mitochondrial depolarization or flavoprotein oxidation. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;134:535–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Korge P, Honda HM, Weiss JN. Protection of cardiac mitochondria by diazoxide and protein kinase C: implications for ischemic preconditioning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3312–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052713199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ylitalo KV, Ala-Rami A, Liimatta EV, Peuhkurinen KJ, Hassinen IE. Intracellular free calcium and mitochondrial membrane potential in ischemia/reperfusion and preconditioning. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:1223–38. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fryer RM, Hsu AK, Gross GJ. Mitochondrial K(ATP) channel opening is important during index ischemia and following myocardial reperfusion in ischemic preconditioned rat hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:831–4. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pain T, Yang XM, Critz SD, Yue Y, Nakano A, Liu GS, Heusch G, Cohen MV, Downey JM. Opening of mitochondrial K(ATP) channels triggers the preconditioned state by generating free radicals. Circ Res. 2000;87:460–6. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.6.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Suzuki M, Sasaki N, Miki T, Sakamoto N, Ohmoto-Sekine Y, Tamagawa M, Seino S, Marban E, Nakaya H. Role of sarcolemmal K(ATP) channels in cardioprotection against ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:509–5016. doi: 10.1172/JCI14270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Suzuki M, Saito T, Sato T, Tamagawa M, Miki T, Seino S, Nakaya H. Cardioprotective effect of diazoxide is mediated by activation of sarcolemmal but not mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channels in mice. Circulation. 2003;107:682–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000055187.67365.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Billman GE, Englert HC, Scholkens BA. HMR 1883, a novel cardioselective inhibitor of the ATP-sensitive potassium channel. Part II: effects on susceptibility to ventricular fibrillation induced by myocardial ischemia in conscious dogs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;286:1465–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ghosh S, Standen NB, Galinanes M. Evidence for mitochondrial K ATP channels as effectors of human myocardial preconditioning. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;45:934–40. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00407-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fryer RM, Eells JT, Hsu AK, Henry MM, Gross GJ. Ischemic preconditioning in rats: role of mitochondrial K(ATP) channel in preservation of mitochondrial function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H305–H312. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.1.H305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jung O, Englert HC, Jung W, Gogelein H, Scholkens BA, Busch AE, Linz W. The K(ATP) channel blocker HMR 1883 does not abolish the benefit of ischemic preconditioning on myocardial infarct mass in anesthetized rabbits. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2000;361:445–51. doi: 10.1007/s002109900212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Holmuhamedov EL, Wang L, Terzic A. ATP-sensitive K+ channel openers prevent Ca2+ overload in rat cardiac mitochondria. J Physiol. 1999;519(Pt 2):347–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0347m.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang L, Cherednichenko G, Hernandez L, Halow J, Camacho SA, Figueredo V, Schaefer S. Preconditioning limits mitochondrial Ca(2+) during ischemia in rat hearts: role of K(ATP) channels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H2321–H2328. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.5.H2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Murata M, Akao M, O'Rourke B, Marban E. Mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channels attenuate matrix Ca(2+) overload during simulated ischemia and reperfusion: possible mechanism of cardio-protection. Circ Res. 2001;89:891–8. doi: 10.1161/hh2201.100205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Eells JT, Henry MM, Gross GJ, Baker JE. Increased mitochondrial K(ATP) channel activity during chronic myocardial hypoxia: is cardioprotection mediated by improved bioenergetics? Circ Res. 2000;87:915–21. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.10.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Forbes RA, Steenbergen C, Murphy E. Diazoxide-induced cardioprotection requires signaling through a redox-sensitive mechanism. Circ Res. 2001;88:802–9. doi: 10.1161/hh0801.089342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vanden Hoek TL, Becker LB, Shao Z, Li C, Schumacker PT. Reactive oxygen species released from mitochondria during brief hypoxia induce preconditioning in cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18092–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Oldenburg O, Cohen MV, Downey JM. Mitochondrial K(ATP) channels in preconditioning. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:569–75. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zweier JL, Flaherty JT, Weisfeldt ML. Direct measurement of free radical generation following reperfusion of ischemic myocardium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:1404–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vanden Hoek TL, Becker LB, Shao ZH, Li CQ, Schumacker PT. Preconditioning in cardiomyocytes protects by attenuating oxidant stress at reperfusion. Circ Res. 2000;86:541–8. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.5.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Takashi E, Wang Y, Ashraf M. Activation of mitochondrial K(ATP) channel elicits late preconditioning against myocardial infarction via protein kinase C signaling pathway. Circ Res. 1999;85:1146–53. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.12.1146. see comments. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Akao M, Ohler A, O'Rourke B, Marban E. Mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channels inhibit apoptosis induced by oxidative stress in cardiac cells. Circ Res. 2001;88:1267–75. doi: 10.1161/hh1201.092094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Akao M, O'Rourke B, Kusuoka H, Teshima Y, Jones SP, Marban E. Differential actions of cardioprotective agents on the mitochondrial death pathway. Circ Res. 2003;92:195–202. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000051862.16691.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM, Mani-Babu S, Duchen MR. Preconditioning protects by inhibiting the mitochondrial permeability transition. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00678.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sato T, Sasaki N, O'Rourke B, Marban E. Nicorandil, a potent cardio-protective agent, acts by opening mitochondrial ATP-dependent potassium channels. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:514–8. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00552-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.D'Hahan N, Moreau C, Prost AL, Jacquet H, Alekseev AE, Terzic A, Vivaudou M. Pharmacological plasticity of cardiac ATP-sensitive potassium channels toward diazoxide revealed by ADP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12162–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Notsu T, Tanaka I, Mizota M, Yanagibashi K, Fukutake K. A cAMP-dependent protein kinase inhibitor modulates the blocking action of ATP and 5-hydroxydecanoate on the ATP-sensitive K+ channel. Life Sci. 1992;51:1851–6. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90036-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jilkina O, Kuzio B, Grover GJ, Folmes CD, Kong HJ, Kupriyanov VV. Sarcolemmal and mitochondrial effects of a KATP opener, P-1075, in “polarized” and “depolarized” Langendorff-perfused rat hearts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1618:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mocanu MM, Maddock HL, Baxter GF, Lawrence CL, Standen NB, Yellon DM, et al. Glimepiride, a novel sulfonylurea, does not abolish myocardial protection afforded by either ischemic preconditioning or diazoxide. Circulation. 2001;103:3111–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.25.3111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]