Abstract

Transient receptor potential channels function in a wide spectrum of tissues and transduce sensory stimuli. The vanilloid (capsaicin) channel TRPV4 is sensitive to osmotic changes and plays a central role in osmoregulatory responses in a variety of organisms. We cloned a zebrafish trpv4 cDNA and assayed its expression during embryogenesis. trpv4 is expressed as maternal mRNA in 4-cell embryos and later zygotic expression is first observed in the forming notochord at the one somite stage. Notochord expression persists to 24 hpf when broad expression in the brain is observed. At 32 hpf trpv4 expression is observed in the endocardium, restricted primarily to the ventricular endothelium. Low level expression of trpv4 is also seen from 32–48 hpf in the pronephric kidney with strongest expression in the most distal nephron segment and in the cloaca. Expression is also observed in lateral line organs starting at 32 hpf, primarily in the hair cells. At 72 hpf, expression of trpv4 in heart, kidney, brain and lateral line organs persists while expression in the notochord is down-regulated.

Keywords: TRPV4, osm-9, zebrafish, osmosensory, ion channel

1. Results and Discussion

Transient receptor potential (TRP) ion channels, initially described in Drosophila, now form a superfamily of proteins divided into 7 sub-families (Caterina et al., 1997; Clapham, 2003; Hellwig et al., 2005). More than 50 proteins belonging to this superfamily of non-selective cation channels have been described in organisms ranging from yeast to human (Nilius and Voets, 2005). TRP channels have been linked to signaling pathways involved in sensing and responding to environmental stimuli which include mechanical/physical stimuli (such as temperature, light, pressure), or chemical stimuli (including phorbol esters, hormone ligands, and metabolites of arachadonic acid). Mutations in a number of different TRP channels have been linked to a variety of diseases. Specifically, the genes implicated in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), polycystin1 and polycystin2, belong to the TRPP subfamily, and play a role in intracellular Ca2+ ion signaling (Cai et al., 1999; Geng et al., 1996; Harris et al., 1995; Liu et al., 2006). In zebrafish, four TRP channel genes have been described (Corey et al., 2004; Elizondo et al., 2005; Sato et al., 2005; Sidi et al., 2003). trpm7 was identified as the gene defective in the mutant touchtone/nutria (Elizondo et al., 2005) which exhibits altered skeletal structure, a diminished response to touch, and kidney stones. trpm7 is expressed in mesonephric kidney tubules, corpuscles of Stannius, and the liver. trpA1 and trpn (nompc) have been shown to contribute to ear and lateral line hair cell function (Corey et al., 2004; Sidi et al., 2003). trpC2 is expressed in the adult olfactory epithelium superficial layer (Sato et al., 2005).

TRPV4, another Ca2+ entry channel, belongs to the vanilloid sub-family and responds to a number of different physical and chemical stimuli including osmotic stress (Clapham, 2003). In Caenorhabditis elegans, mammalian TRPV4 can partially rescue the osmotically and nocireceptive mutant osm-9 (Liedtke et al., 2003). Abundantly expressed in mouse kidney, TRPV4 (also known as TRP12, VR-OAC, OTRPC4, and VRL-2) was the first member of this subfamily to be described in mammals (Caterina and Julius, 2001; Wissenbach et al., 2000). Interestingly, an association between TRPV4 and the water permeability channel aquaporin 5 has been described (Liu et al., 2006), implicating TRPV4 in regulating osmotic homeostasis. A recent study has shown that in mammals, epithelial ciliary beat frequency is also regulated by TRPV4 in response to changes in fluid viscosity (Andrade et al., 2005). Our previous work has implicated the importance of functional cilia to normal zebrafish organogenesis and pronephros integrity (Kramer-Zucker et al., 2005). To analyze the zebrafish TRPV4 homolog we cloned zebrafish trpv4 and characterized its spatial and temporal expression pattern during embryogenesis.

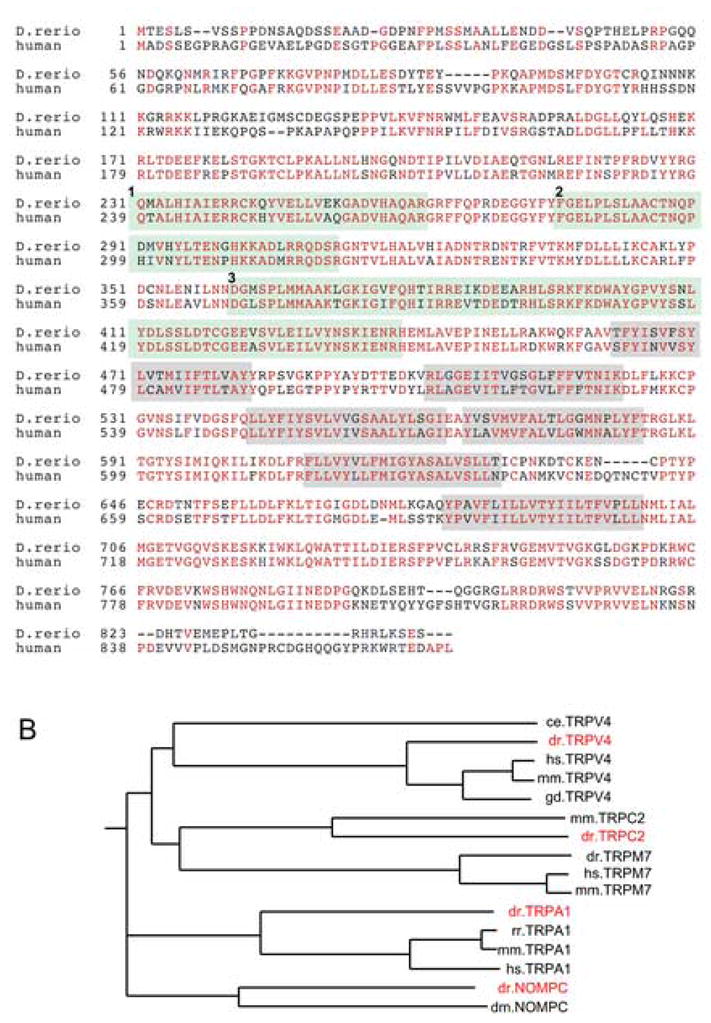

RT-PCR using total RNA from 48 hpf and 4 dpf embryos and zebrafish trpv4 specific primers were used to clone zebrafish trpv4. The resulting open reading frame is predicted to encode a protein product of 841 amino acids containing a conserved, N-terminal domain containing three ankyrin repeats and six transmembrane domains similar to the human TRPV4 (Figure 1A; genbank accession DQ858167). Zebrafish Trpv4 is 72% identical and 82% similar to the human TRPV4 (Figure 1A) and 26% identical and 44% similar to Caeanorhabditis elegans Osm-9.

Figure 1. Conservation of TRPV4 protein sequence and phylogeny of zebrafish TRP channels.

(A) Zebrafish Trpv4 is 72% identical to human TRPV4 (red residues represent identity). N-terminal ankyrin repeats are individually highlighted in light green (numbered 1–3) and transmembrane domains that constitute the ion transporting domain are highlighted in grey. Accession numbers used for alignment of protein sequences were zebrafish trpv4 (DQ858167; this paper), and human TRPV4 (AAG16127). Alignment was carried out using the ClustalW algorithm (Thompson et al., 1994) and shaded with Boxshade. (B) Phylogenetic tree representation of evolutionary relationships between zebrafish TRP channel orthologs and cloned full length TRP channels of other species (dr: zebrafish; mm: mouse; hs: human; ce: c. elegans; rr: rat; gd: chicken with branch length proportional to evolutionary distance.

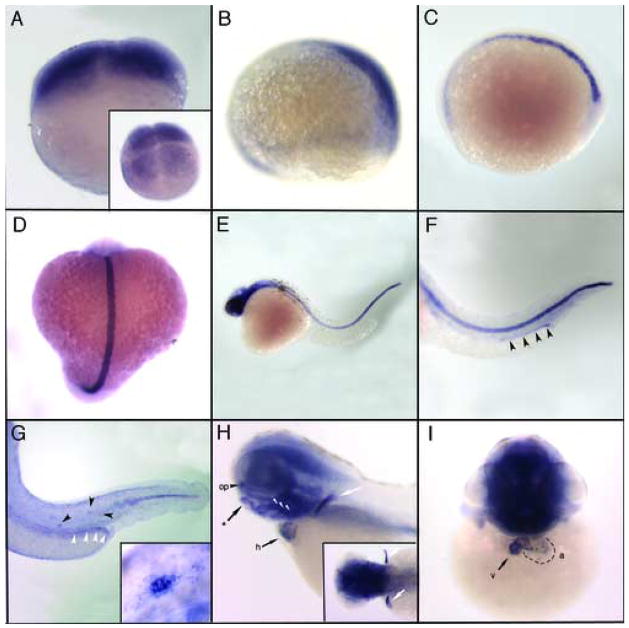

Whole mount in situ hybridization revealed expression of trpv4 in zebrafish embryos from various stages ranging from 4-cells to 3 days post fertilization (dpf) (Figure 2). The detection of trpv4 mRNA at the 4 cell stage (Figure 2A) indicates that it is maternally supplied to the embryo. Expression is restricted to posterior-dorsal cells by 75% epiboly (Figure 2B). At the 1 somite stage (Figure 2C), trpv4 can only be detected in the notochord. This pattern of expression extends to at least the 18 somite stage (Figure 2D). Expression continues in the notochord and extends strongly into the head region of the embryo by 24 hpf (Figure 2E). Organ-specific expression becomes evident beginning at 32 hpf (Figure 2F), when trpv4 is localized to the posterior region and in the cloaca of the pronephros, equivalent to segments S3 and S4 (Nichane et al., 2006). These segments of the pronephric nephron are similar to the distal tubule and collecting system of the mammalian kidney (Nichane et al., 2006). In the zebrafish mesonephric kidney, the trpm7 calcium transporter gene also shows segment specific expression in more proximal nephron segments and the collecting tubule (Elizondo et al., 2005). At 40 hpf (Figure 2G) trpv4 expression can be detected in sensory structures, specifically the developing posterior lateral line organs (PLL) (Dambly-Chaudiere et al., 2003). Expression of the related TRP channel trpn (nompc) has been observed in sensory patches of the embryonic zebrafish ear (Sidi et al., 2003). Also evident by this stage is a reduction of trpv4 expression in the notochord. Anterior expression is markedly reduced as posterior notochord expression remains. At 3 dpf, trpv4 expression is enhanced in chondrogenic tissues including the developing jaw, pharyngeal arches and pectoral fins (Figure 2H). Cells of the olfactory pit also show strong expression at this stage. Zebrafish trpc2 and Xenopus TRPN1 are also expressed in olfactory epithelial cells (Sato et al., 2005; Shin et al., 2005). A frontal view of a 3 dpf embryo (Figure 2I) shows the cardiac chamber-specific expression pattern of trpv4, primarily in the ventricle with some expression in atrial endocardium adjacent to the A/V junction.

Figure 2. Expression of zebrafish trpV4 by whole mount in situ hybridization.

trpv4 mRNA expression is ubiquitous in blastomeres beginning at the 4 cell stage (A, inset-dorsal view) through to late epiboly. (B) At 75% epiboly, trpv4 shows enhanced expression on the posterior dorsal side of the embryo. At the one somite stage (C) and continuing on until 18 hpf (D), expression is predominately in the notochord with low level expression in the anterior presumptive head region. (E) Head expression becomes enhanced by 24 hpf. (F) At 32 hpf, notochord expression remains strong and trpv4 signal can be detected in the pronephric ducts (black arrow heads). (G) Expression in the notochord is reduced by 40 hpf, decreasing in an anterior to posterior direction. Pronephric duct expression (white arrow heads) persists and staining can be detected in the lateral line organs (black arrow heads, and inset). (H–I) At 3 dpf trpv4 mRNA is highly expressed in brain and head structures. Expression can be seen in the olfactory placodes (op), in chondrogenic tissues including the forming jaw bones (asterisk), pharyngeal arches (white arrow heads) and pectoral fin buds (white arrows, and inset). Expression in the heart (h) is easily detected at this stage, primarily in the ventricle (v) and upper atrium (a).

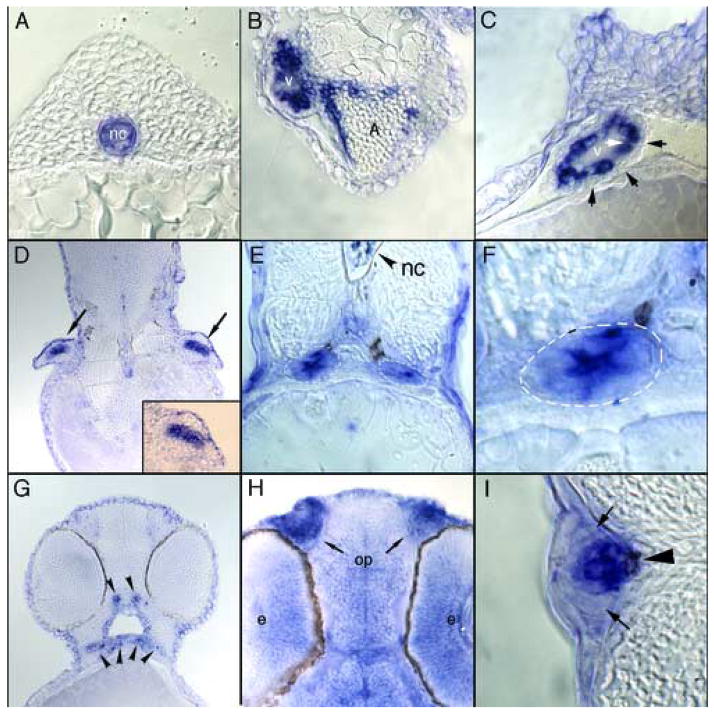

To examine trpv4 expression at higher resolution, whole mount in situ stained embryos were histologically sectioned. Consistent with early stage whole-mount in situ hybridized embryos, trpv4 expression is initially restricted to the notochord (Figure 3A). The asymmetric expression of trpv4 in the heart is clearly seen in cross-section (Figure 3B). The intense expression in the ventricle appears to be restricted to the endocardial cells, since there is a surrounding myocardial layer of non-expressing cells (Figure 3C). Intense expression of trpv4 can also be seen within chondrogenic tissues as illustrated by expression in the forming cartilage of the pectoral fins (Figure 3D) and developing craniofacial bones (Figure 3G). trpv4 expression in the kidney was confirmed by examining cross-sections of in situ hybridized embryos at 32 hpf (Figure 3E, F). Expression in neural tissue appears to be uniform (Figure 3H) and the enhanced expression in the olfactory pits is clearly visible in frontal sections through the head of 32 hpf embryos. A cross-section through a posterior lateral line organ of a 32 hpf embryo shows expression of trpv4 in the hair cells of the developing neuromast with little expression in the surrounding support or mantle cells (Figure 3I).

Figure 3. Histological analysis of trpv4 expression.

Embryos used for in situ hybridization analysis were embedded in JB-4 and sectioned at 10–12.5 μm then examined by light microscopy. (A) Expression is restricted to the notochord in 18 hpf embryos. (B) Sections through a 72 hpf embryo heart show strong expression in the ventricle (v) and upper regions of the atrium (a). (C) A closer examination of ventricular staining illustrates that trpv4 mRNA expression is restricted to cells of the endocardium (white arrow) and absent from surrounding myocardial cells (black arrows). (D) Frontal section of 52 hpf embryos highlighting the presence of trpv4 mRNA in the forming cartilage of the pectoral fin buds (black arrows and magnification in inset). (E–F) trpv4 expression in the pronephric duct (white dashes) is detected in 32 hpf embryos. (G) Cross section through 52 hpf embryos shows expression in the developing bones of the jaw (arrowheads). (H) Frontal section through a 32 hpf embryo shows that trpv4 mRNA is strongly expressed throughout the brain and eye (e) with enhanced expression in the olfactory placodes (op). (I) Cross section through a lateral line organ of a 32 hpf embryo shows specific expression in hair cell bodies of the neuromast (arrowhead) and no expression in surrounding mantle cells (small arrows).

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1 Zebrafish embryos

Wild type TL or TÜAB zebrafish lines were maintained and raised as previously described (Westerfield, 1995). Embryos were reared at 28.5°C in E3 solution with 0.003% PTU (1-Phenyl-2-thiourea, Sigma) added to retard pigment formation. Embryonic staging was performed as previously described (Westerfield, 1995).

2.2 In situ hybridization and histology

Antisense DIG-labeled RNA probes were generated, and in situ hybridization analysis was performed as previously described (Jowett, 1999). Expression patterns were assessed using pools of 12–24 embryos for each stage studied on at least 3 separate occasions. Experiments using DIG-labeled sense probes did not show hybridization signals. Some data presented (lateral line whole mount magnification) is the result of employing a probe that was subjected to alkaline hydrolysis to generate a shorter length probe. Embryos older than 24 hpf were subjected to proteinase K treatment for 5–20 minutes depending on age. Embryos were incubated with 5μg/mL of antisense probe overnight at 65°C. After extensive washing, embryos were blocked in Maleic acid buffer (0.1M Maleic Acid, 0.15M NaCl, pH 7.5) containing 10% normalized goat serum (NGS) for a minimum of 2 hours at room temperature to overnight at 4°C. Post-block, embryos were incubated with alkaline–phosphatase conjugated anti-DIG FAB fragments (Roche) at a dilution of 1:5000. Colorimetric reaction was carried out overnight, in the dark at 4°C, and in the presence of 350 μg/ml nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) and 175 μg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (BCIP). Color precipitate was imaged on a Nikon E800 microscope equipped with a Spot Image digital camera.

Histological analysis on embryos after in situ hybridization analysis was carried out after stained embryos were briefly fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde then dehydrated through a series of washes of 25%/75%, 50%/50%, 75%/25% (PBST/MeOH), 100% MeOH for at least 10 minutes each followed by embedding in JB-4 (Polysciences, Inc.). A Riechert–Jung Supercut 2065 (Leica) microtome was used to generate 10–12.5 μm thick sections. A Nikon E800 microscope equipped with a Spot Image digital camera was used for photography.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank members of the Drummond lab for feedback on this work. This work was supported by NIH grants RO1 DK53093 and DK54711.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andrade YN, Fernandes J, Vazquez E, Fernandez-Fernandez JM, Arniges M, Sanchez TM, Villalon M, Valverde MA. TRPV4 channel is involved in the coupling of fluid viscosity changes to epithelial ciliary activity. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:869–74. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Maeda Y, Cedzich A, Torres VE, Wu G, Hayashi T, Mochizuki T, Park JH, Witzgall R, Somlo S. Identification and characterization of polycystin-2, the PKD2 gene product. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28557–65. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Julius D. The vanilloid receptor: a molecular gateway to the pain pathway. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:487–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–24. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham DE. TRP channels as cellular sensors. Nature. 2003;426:517–24. doi: 10.1038/nature02196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey DP, Garcia-Anoveros J, Holt JR, Kwan KY, Lin SY, Vollrath MA, Amalfitano A, Cheung EL, Derfler BH, Duggan A, Geleoc GS, Gray PA, Hoffman MP, Rehm HL, Tamasauskas D, Zhang DS. TRPA1 is a candidate for the mechanosensitive transduction channel of vertebrate hair cells. Nature. 2004;432:723–30. doi: 10.1038/nature03066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dambly-Chaudiere C, Sapede D, Soubiran F, Decorde K, Gompel N, Ghysen A. The lateral line of zebrafish: a model system for the analysis of morphogenesis and neural development in vertebrates. Biol Cell. 2003;95:579–87. doi: 10.1016/j.biolcel.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elizondo MR, Arduini BL, Paulsen J, MacDonald EL, Sabel JL, Henion PD, Cornell RA, Parichy DM. Defective skeletogenesis with kidney stone formation in dwarf zebrafish mutant for trpm7. Curr Biol. 2005;15:667–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng L, Segal Y, Peissel B, Deng N, Pei Y, Carone F, Rennke HG, Glucksmann-Kuis AM, Schneider MC, Ericsson M, Reeders ST, Zhou J. Identification and localization of polycystin, the PKD1 gene product. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2674–82. doi: 10.1172/JCI119090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PC, Ward CJ, Peral B, Hughes J. Polycystic kidney disease. 1: Identification and analysis of the primary defect. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1995;6:1125–33. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V641125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellwig N, Albrecht N, Harteneck C, Schultz G, Schaefer M. Homo- and heteromeric assembly of TRPV channel subunits. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:917–28. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jowett T. Analysis of protein and gene expression. Methods Cell Biol. 1999;59:63–85. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61821-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer-Zucker AG, Olale F, Haycraft CJ, Yoder BK, Schier AF, Drummond IA. Cilia-driven fluid flow in the zebrafish pronephros, brain and Kupffer’s vesicle is required for normal organogenesis. Development. 2005;132:1907–21. doi: 10.1242/dev.01772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedtke W, Tobin DM, Bargmann CI, Friedman JM. Mammalian TRPV4 (VR-OAC) directs behavioral responses to osmotic and mechanical stimuli in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(Suppl 2):14531–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235619100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Bandyopadhyay B, Nakamoto T, Singh B, Liedtke W, Melvin JE, Ambudkar I. A role for AQP5 in activation of TRPV4 by hypotonicity: concerted involvement of AQP5 and TRPV4 in regulation of cell volume recovery. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15485–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600549200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichane M, Van Campenhout C, Pendeville H, Voz ML, Bellefroid EJ. The Na(+)/PO(4) cotransporter SLC20A1 gene labels distinct restricted subdomains of the developing pronephros in Xenopus and zebrafish embryos. Gene Expr Patterns. 2006;6:667–672. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B, Voets T. TRP channels: a TR(I)P through a world of multifunctional cation channels. Pflugers Arch. 2005;451:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1462-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y, Miyasaka N, Yoshihara Y. Mutually exclusive glomerular innervation by two distinct types of olfactory sensory neurons revealed in transgenic zebrafish. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4889–97. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0679-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin JB, Adams D, Paukert M, Siba M, Sidi S, Levin M, Gillespie PG, Grunder S. Xenopus TRPN1 (NOMPC) localizes to microtubule-based cilia in epithelial cells, including inner-ear hair cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12572–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502403102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidi S, Friedrich RW, Nicolson T. NompC TRP channel required for vertebrate sensory hair cell mechanotransduction. Science. 2003;301:96–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1084370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–80. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield M. The Zebrafish Book. University of Oregon Press; Eugene, Oregon: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wissenbach U, Bodding M, Freichel M, Flockerzi V. Trp12, a novel Trp related protein from kidney. FEBS Lett. 2000;485:127–34. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]