Summary

Mechanotransduction, the conversion of a mechanical stimulus into an electrical signal is critical for our ability to hear and to maintain balance. Recent findings indicate that two members of the cadherin superfamily are components of the mechanotransduction machinery in sensory hair cells of the vertebrate inner ear. These studies show that cadherin 23 (CDH23) and protocadherin 15 (PCDH15) form several of the extracellular filaments that connect the stereocilia and kinocilium of a hair cell into a bundle. One of these filaments is the tip link that has been proposed to gate the mechanotransduction channel in hair cells. The extracellular domains of CDH23 and PCDH15 differ in their structure from classical cadherins and their cytoplasmic domains bind to distinct effectors, suggesting that evolutionary pressures have shaped the two cadherins for their function in mechanotransduction.

Introduction

The cadherin superfamily consists of about 100 members with a variety of roles in tissue development, maintenance and function. The defining feature of the superfamily is the extracellular cadherin (EC) domain that occurs in varying repetitions in all cadherins. Classical cadherins are the founding members of the superfamily and mediate Ca2+-dependent adhesive interactions between cells [1,2]. Recent studies reveal that cadherin 23 (CDH23) and protocadherin 15 (PCDH15), two distant relatives of classical cadherins, also mediate adhesive interactions. CDH23 and PCDH15 are expressed in mechanosensory hair cells of the inner ear where they are components of the extracellular filaments that control the morphogenesis and function of the mechanically sensitive hair bundle. While classical cadherins mediate adhesion between different cells, CDH23 and PCDH15 connect different membrane compartments within the hair bundle of a hair cell. These studies link cadherins to mechanotransduction and indicate that members of the cadherin superfamily guide morphogenesis not only at the tissue level, but also at the cellular level.

Mechanosensory hair cells

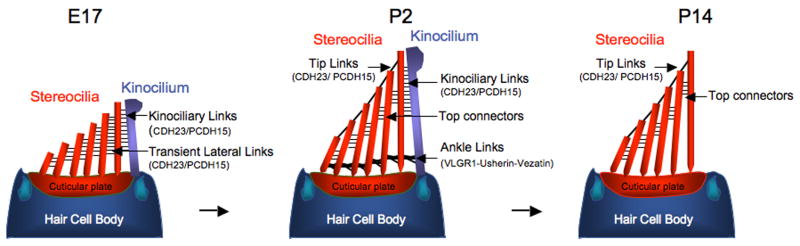

Our ability to perceive sound and maintain balance is critically dependent on the process of mechanotransduction, i.e. the conversion of mechanical stimuli that are evoked by sound waves and head movements into electrical signals that are processed by the nervous system. Hair cells in the inner ear are the specialized mechanosensory cells that carry out the conversion process. Hair cells carry at their apical surface a bundle of F-actin rich stereocilia that form the mechanically sensitive organelle of the cell (Fig. 1). Cation-selective mechanotransduction channels are localized towards stereocilia tips, and open upon stereocilia deflection, within microseconds and without second-messenger intervention. The stereocilia of a hair cell are not randomly organized but form a staircase of decreasing height that is polarized in the apical hair cell surface. Polarization is critical for hair cell function because only deflection of the hair bundle in the direction of the longest stereocilia increases the open probability of mechanotransduction channels. The tallest rows of stereocilia abut a single microtubule based kinocilium, which degenerates in some hair cells once the hair bundle has matured (Fig. 1). While the kinocilium is not required for mechanotransduction, it is likely important for hair bundle development and polarity. Consistent with this model, the stereociliary staircase of a hair bundle is established by differential elongation of microvilli, where microvilli next to the kinocilium become the longest stereocilia, while those that are further away remain shorter [3-5].

Figure 1. Development of the hair bundle in murine cochlear hair cells.

Hair bundles develop by the elongation of a single microtubule based kinocilium and of actin rich stereocilia that project from the apical surface of each hair cell. The actin filaments in stereocilia are oriented in parallel, with the barbed end pointing to the top of stereocilia. Stereocilia that are next to the kinocilium grow into the longest stereocilia, while those that are further away remain shorter. The kinocilium degenerates in murine cochlear hair cells when the hair bundle has matured. The stereocilia are tapered at their base and anchored in the cuticular plate that contains highly crosslinked F-actin filaments of mixed polarity. Stereocilia are connected to each other and to the kinocilium by a various filaments that are remodeled during hair cell development as indicated in the diagram.

The plasma membrane of a hair cell is extensively folded to cover the entire hair bundle. Extracellular linker filaments with distinct morphological and biochemical features connect the plasma membranes surrounding adjacent stereocilia and the kinocilium (Fig. 1). These linkages undergo dramatic remodeling during hair cell maturation and show some variations between hair cells in different species. Prominent linkages in developing mouse cochlear hair cells are transient lateral links, ankle links and kinociliary links. Functionally mature hair cells contain horizontal top connectors and tip links (Fig. 1) [6]. Until recently, the function of the linkages in hair cells has mostly been inferred by indirect means because their molecular composition has remained unknown. Linkages in developing hair cells are thought to propagate signals or forces that shape the mechanically sensitive hair bundle while tip links are implicated in gating mechanotransduction channels in hair cells [3-5].

Mutations in CDH23 and PCDH15 cause Usher Syndrome and recessive forms of deafness

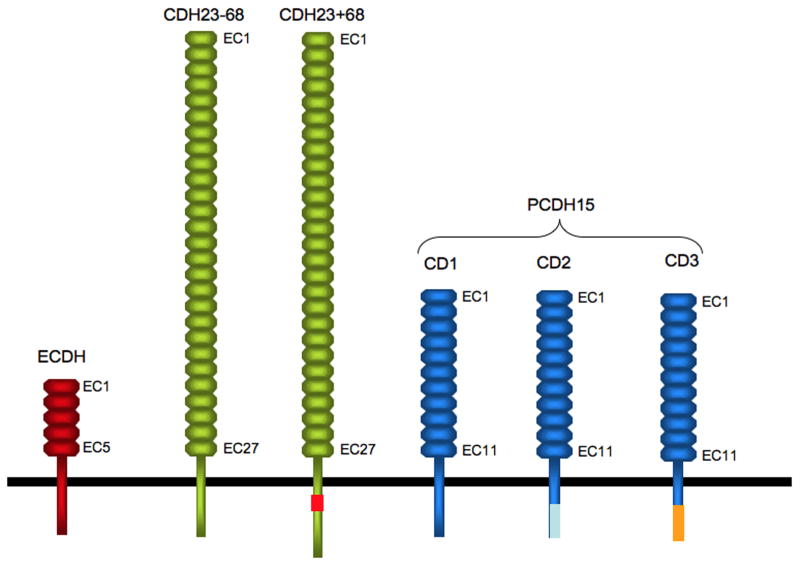

Based on the membrane topology of hair bundles, transmembrane receptors with adhesive properties are good candidates to form at least some of the linkages that connect the stereocilia to each other and to the kinocilium. A first indication that cadherins may be involved came from the study of human patients suffering from Usher Syndrome (USH), a complex genetic disease and the leading cause of deaf-blindness in humans. Usher Syndrome Type I (USH1) is the most severe form of the diseases. USH1 patients are born deaf, show vestibular dysfunction, and suffer from progressive retinitis pigmentosa. Five genes have been linked to USH1. They encode the transmembrane receptors CDH23 and PCDH15, the actin based molecular motor myosin VIIa (Myo7a), and the adaptor proteins harmonin and SANS [7,8]. Sequence analysis has revealed that CDH23 and PCDH15 belong to different branches of the cadherin superfamily. CDH23 is a relative of FAT cadherins. One hallmark of FAT cadherins is the structure of their extracellular domain, which consists of many more EC domains than the extracellular domains of classical cadherins. While classical cadherins typically contain 5 EC domains, the full-length CDH23 protein contains 27 EC domains (Fig. 2) [9-12]. Alternative splicing generates CDH23 isoforms including the CDH23-68 and CDH23+68 isoforms that differ in their cytoplasmic domain by exclusion/inclusion of exon 68 encoded amino acids (Fig. 2) [13-16]. The amino acid sequence and structure of the extracellular domain of PCDH15 also differs from classical cadherin and is related to the protocadherin branch of the cadherin superfamily [17-19]. Full-length PCDH15 contains 11 EC domains, but smaller splice variants and isoforms with distinct cytoplasmic domains have also been reported (Fig. 2) [20-24].

Figure 2. Diagram of CDH23 and PCDH15.

Cadherin 23 and PCDH15 belong to the cadherin superfamily. Their extracellular domains contain substantially more EC domains than present in classical cadherins such as ECDH. Different splice variants of CDH23 and PCDH15 that differ in their cytoplasmic domains and are discussed in the text are shown. Extracellular splice variants have been omitted for clarity.

Interestingly, mutations in CDH23 and PCDH15 cause not only USH1 but also recessive deafness without vestibular and retinal impairment. While mutations that cause disease are located throughout the CDH23 and PCDH15 genes with no apparent hot spots, there is an interesting correlation. Mutations that are predicted to truncate CDH23 and PCDH15 in the extracellular domains typically cause USH1, while missense mutations that are predicted to change single amino acids are commonly associated with recessive deafness [9,10,17,19,25-32]. The mutation spectrum suggests that functional null alleles cause USH1, while hypomorphic alleles lead to less severe forms of the disease.

Expression and function of CDH23 and PCDH15 in developing hair cells

Mouse models have been instrumental in providing insights into the function of CDH23 and PCDH15 in the inner ear and into potential disease mechanisms. CDH23 colocalizes in developing murine stereocilia with transient lateral links and kinociliary links. [14,15,33,34]. Intriguingly, while CDH23 is expressed in several additional tissues within the body including the retina, the CDH23+68 splice variant (Fig. 2) has so far only been detected in stereocilia [34]. Three prominent PCDH15 isoforms (PCDH15-CD1, -CD2, -CD3) that contain distinct cytoplasmic domains can also be distinguished (Fig. 2) [17-20]. The CD1 isoform is expressed along the length of stereocilia with highest concentration towards the base and little expression at tips [20,35]. The CD2 isoform has been reported to be distributed widely in hair bundles, while the CD3 isoform appears to become concentrated at stereociliary tips [20]. The expression patterns suggest that different PCDH15 isoforms are likely components of transient lateral links and kinociliary links, but higher resolution studies are necessary before definitive conclusions can be reached. Mice with predicted null alleles in the genes encoding CDH23 and PCDH15 show fragmentation of hair bundles and displacement of the kinocilium within the apical hair cell surface, indicating that transient lateral links and kinociliary links control hair bundle development and cohesion [11,12,18,35-37]. The elongation of stereocilia also appears to be affected in hair cells from the mutant mice [36], suggesting that CDH23 and PCDH15 may control the assembly of the cytoskeleton in hair bundles. This model is supported by studies of Cad99C, the drosophila ortholog of PCDH15. In flies, Cad99C controls the length of microvilli of ovarian follicle cells [38]. Stereocilia in hair cells are generated by elongation of microvilli, suggesting a potential evolutionary conserved function for PCDH15 in controlling the growth of microvilli.

Despite the emerging picture that CDH23 and PCDH15 are components of linkages in developing hair cells, several questions remain. First, we do not know the spatial arrangement of CDH23 and PCDH15 in these linkages. Are there two linkage types, one that is formed by homophilic interactions between CDH23 molecules and a second that is formed by homophilic interactions between PCDH15 molecules? Or do CDH23 and PCDH15 interact heterophilically to form the linkages? Biochemical studies have shown that CDH23 molecules can mediate homophilic adhesive interactions [34]. In addition, CDH23 can bind heterophilically to PCDH15 [39]. However, homophilic binding activity for PCDH15 has not been observed [39]. As one caveat, regulation of posttranslational modification or splicing may affect homo- and heterophilic binding activity in vivo in hair cells. It can also not be excluded that transient lateral links and kinociliary links contain additional molecules, or that several molecularly distinct linkages co-exist. In fact, some linkages still connect the stereocilia in the fragmented hair bundles of mice with mutations in Cdh23 and Pcdh15 [35-37]. Candidate molecules that could contribute to the remaining linkages are the very large G-protein-coupled receptor 1 (VLGR1), Usherin, vezatin, and the receptor tyrosine phosphatase receptor Q (PTPRQ). VLGR1, Usherin and vezatin are thought to be components of ankle links (Fig. 1) [40-42], but additional functions cannot be excluded. RTPRQ is required for the formation/maintenance of extracellular linkages in hair bundles [43], but it is not clear if it is a direct component of the linkages. The clarification of the molecular composition of the different linkages in developing hair bundles is important in order to define their specific functions. Many different proteins appear to contribute, suggesting that the linkages are not just serving as passive adhesive structures.

Expression and functions of CDH23 and PCDH15 in functionally mature hair cells

Of all the extracellular filaments in hair cells, tip links have received the most attention, because of their potential function in mechanotransduction. Tip links are appropriately positioned in the direction of the mechanical sensitivity of the hair bundle to participate in transduction channel gating [44]. Consistent with the tip-link model of channel gating, treatment of hair bundles with elastase or Ca2+ chelators that disrupt tip links also abolish opening of transduction channels in response to mechanical stimuli [45]. After removal of the disrupting agents, regeneration of tip links and recovery of the mechanical sensitivity follow a similar time course [46]. High-resolution ultrustructural studies have shown that tip links consist of two strands that form a helical filament approximate 150 – 200 nm in length [47,48]. The axial periodicity of tip links is 20 – 25 nm with each strand being composed of globular structures that are approximately 4 nm in diameter [48]. The spacing of the globular structures is similar to the 4.3 nm center-to-center spacing that has been reported for cadherin repeats [49]. At both insertion points into the membrane, the tip-link helix seems to separate into several strands. More than two strands have been observed at the insertion points, suggesting that anchoring filaments attach to the two strands of the tip-link filament [47].

The genetic linkage of mutations in CDH23 and PCDH15 to deafness, the structural signature of tip links, and tip-link sensitivity to Ca2+ chelators suggests that tip links may be adhesion complexes that contain CDH23 and/or PCDH15. Using high-resolution immunolocalization studies and antibodies to the CDH23 cytoplasmic domain, CDH23 has been localizes to tip links of mature hair cells [34]. Antibodies to the cytoplasmic domain of the CD1 isoform of PCDH15 stain stereocilia broadly, including the side of stereocilia where the upper end of the tip link inserts into the stereociliary membrane [20]. An antibody to the CD3 isoform stains the tips of stereocilia, overlapping the region where the lower end of the tip link inserts [20]. These findings are compatible with the idea that the extracellular domains of CDH23 and PCDH15 form the tip-link filament. However, several findings initially suggested that CDH23 and PCDH15 might not be tip-link components. First, some laboratories failed to observe CDH23 expression in functionally mature hair cells [14,15]. Second, PCDH15 expression was observed in mature hair cells from chickens but not from mammals [20].

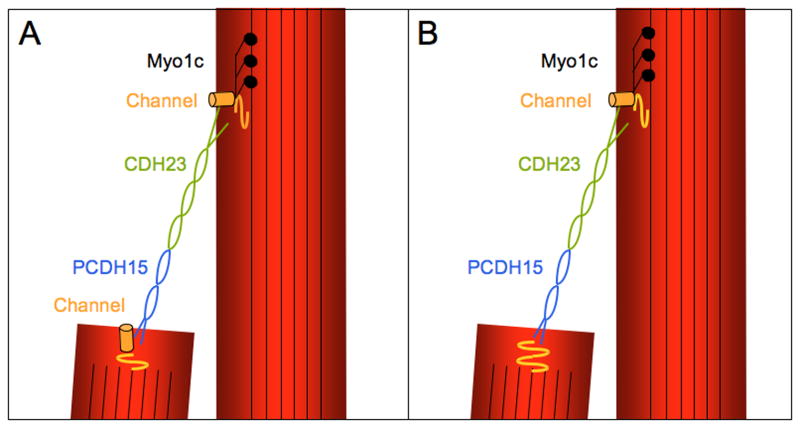

To resolve the controversy, additional antibodies were raised that recognize different epitopes along the extracellular domain of CDH23 and PCDH15. Staining of hair cells from mice, rats, and guinea pigs confirmed robust expression of CDH23 and PCDH15 in adult hair cells [39], suggesting that the failure to detect CDH23 and PCDH15 by some laboratories was a consequence of low antibody affinity, low detection sensitivity, or epitope masking. Subsequent mapping of the distribution of CDH23 and PCDH15 epitopes along the tip-link filament have demonstrated that CDH23 localize towards the upper tip-link part, PCDH15 to the lower tip-link part, with epitopes that are close to the N-terminus of the two proteins showing an overlap [39]. The immunolocalization studies suggest that the extracellular domains of CDH23 and PCDH15 interact via their N-termini to form the tip-link filament (Fig. 3). This model is supported by the analysis of recombinant purified extracellular domains of CDH23 and PCDH15 at single molecule resolution using negative staining transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The TEM images show that the extracellular domains of both CDH23 and PCDH15 form parallel homodimers and interact via their N-termini to form an intertwined filament. The filament is approximately 180 nm in length, which is in excellent agreement with tip-link dimensions [39]. Biochemical experiments have confirmed that CDH23 and PCDH15 adhere to each other via their N-termini. Adhesive interactions between CDH23 and PCDH15 and tip-link integrity show similar ion dependence, requiring Ca2+, while being labile in the presence of LaCl3 [39]. Finally, studies in zebrafish, which contain hair cells in their lateral line organ for sensing fluid motion, support that CDH23 is an essential tip-link component. CDH23 is expressed in the hair cells of zebrafish and mutations in CDH23 lead to tip-link loss [50]. Taken together, these findings provide strong evidence that the tip-link filament is formed by a CDH23 homodimer interacting in trans with a PCDH15 homodimer (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Molecular tip-link models.

(A) Tip links are heterophilic cell adhesion complexes that consist of CDH23 homodimers interacting in trans with PCDH15 homodimers. Additional anchoring filaments that interact with CDH23 and/or PCDH15 may also be present but have been omitted from the diagram. According to current models, mechanotransduction channels are located at both ends of a tip link and connected to the cytoskeleton. It is unclear whether the connection of the channels to the tip link and the cytoskeleton is direct or mediate by additional proteins. Myo1c molecules are thought to act as adaptation motors for the transduction channel. (B) The molecular asymmetry within the tip link raises the possibility that transduction channels are also asymmetrically localized in stereocilia. A model is shown where the channel is located at the upper end of a tip link, but other models can be envisioned.

Are CDH23 and PCDH15 the only components of tip links? As described above, analysis of tip links by electron microscopy suggests that additional proteins are present at the anchoring points [47]. Furthermore, reports on the length of tip links vary, with extremes ranging up to 300 nm in length. At present it is not clear whether this is an artifact of sample preparation. A recent systematic analysis using guinea-pig hair cells reports length variations for tip links between ∼135 and 190 nm depending on the Ca2+ concentration [51]. A value of ∼185 nm was reported at 50 μM Ca2+, which is similar to the Ca2+ concentration of the endolymph that surrounds tip links in vivo [52], and is in excellent agreement with the ∼180 nm for the filament formed by the extracellular domains of CDH23 and PCDH15 [39]. Guinea pig tip links are shorter at higher Ca2+ concentrations [51], raising the interesting possibility that variations in length could be functionally relevant and affect the gating of mechanotransduction channels. While tip links appear in the electron microscope as rigid molecules that buckle under strain [47], it cannot be excluded that rigidity is a consequence of sample fixation. It will be particularly important to determine the properties of CDH23 and PCDH15 under forces that are exerted on the tip link during mechanical stimulation. Finally, the observation that tip links are asymmetric structures has important implications for prevailing tip-link models. Tip links are frequently depicted as filaments that connect to the extracellular domain of mechanotransduction channels, with channels at both tip-link ends (Fig. 3A) [5,53]. While experimental evidence lends support to this model [54], the recent findings raise the possibility that tip links consist of transmembrane proteins with functionally distinct ends, where a transduction channel(s) may only be located at one end (Fig. 3B).

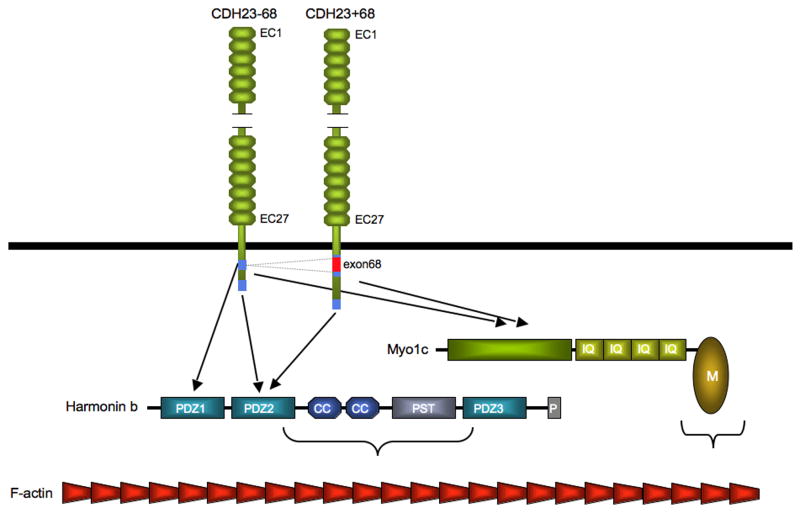

The PDZ domain protein harmonin binds to the cytoplasmic domains of CDH23 and PCDH15

The cytoplasmic domains of CDH23 and PCDH15 are not related and show no sequence homology to classical cadherins, suggesting that each of the two cadherins recruits a unique set of effectors. One exception is the extreme C-terminus of CDH23-68, CDH23+68, PCDH15-CD1, -CD2, and -CD3, which fit the consensus for binding motifs that recruit PDZ domain proteins. Using yeast-two hybrid analysis and protein interaction studies, the PDZ domain protein harmonin has been identified as a binding partner for CDH23-68, CDH23+68 and PCDH15-CD1 [16,35,55-57] (Fig. 4,5). By immunohistochemistry, harmonin has been localized to developing sensory hair cells and their stereocilia [36,56], suggesting that the biochemical interactions with CDH23 and/or PCDH15 are of functional significance. Additional biochemical studies have led to a surprising finding. While the PDZ2 domain of harmonin binds to the extreme C-terminus of CDH23-68, CDH23+68, and PCDH15-CD1 [36,56], there is an additional membrane proximal binding site for PDZ1 in CDH23-68. Intriguingly, this binding site is disrupted by inclusion of exon 68 in CDH23+68 (Fig. 4) [16]. Since CDH23+68 expression has only been detected in hair cells [34], tissue specific splicing may be critical for the structural organization of the CDH23-harmonin complex in the inner ear. Functional studies will be important to evaluate this possibility. In addition, it remains to be determined whether harmonin can bind to PCDH15-CD2 and PCDH15-CD3.

Figure 4. Interaction partners for the cytoplasmic domain of CDH23.

The PDZ domain protein harmonin interacts with the cytoplasmic domain of CDH23-68 and CDH23+68 and with F-actin. The CDH23-68 isoform binds to the PDZ1 and PDZ2 domain of harmonin via an internal and C-terminal binding motif within the CDH23 cytoplasmic domain (blue rectangles), respectively. The internal binding motif is disrupted in CDH23+68 by amino acids that are encoded by alternatively spliced exon 68. A harmonin fragment encompassing the two coiled coil (CC) domains, the proline-serine-threonine (PST) domain, and PDZ3 contains the F-actin binding domain. CDH23-68 and CDH23+68 can also be co-immunoprecipitated with Myo1c, but it has not been shown that the proteins bind directly to each other or are linked by other molecules.

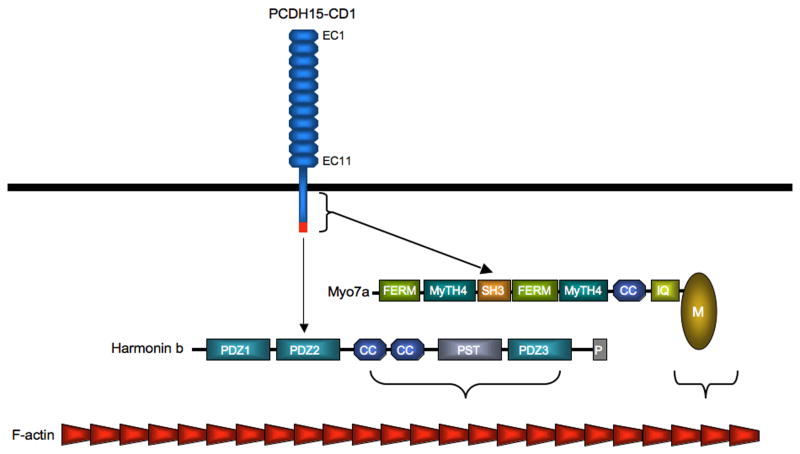

Figure 5. Interaction partners for the cytoplasmic domain of PCDH15-CD1.

The PDZ1 domain of harmonin interacts with the extreme C-terminus of PCDH15-CD1 (red rectangle) (although other modes of interaction have also been proposed [55]). Myo7a binds directly to the PCDH15-CD1 cytoplasmic domain via the SH3 domain of Myo7a.

Mutations in the harmonin gene in humans lead to USH1 and cause hair bundle defects in mouse models [36,58], consistent with the model that harmonin is required for CDH23 and PCDH15 functions in developing hair cells. Of the different harmonin splice variants that have been reported, the longest b isoform is expressed in developing hair bundles [56]. Significantly, harmonin b can bind and bundle F-actin [56]. While direct experimental evidence is still lacking, this finding suggest that harmonin b may link CDH23 and PCDH15 to the F-actin cytoskeleton of stereocilia (Fig. 4,5). Harmonin also binds to Dock-4, a regulator of RapGTPase that controls the formation of adherence junctions [59]. Dock-4 function is controlled by the small GTPase RohG and its effector ELMO that promote cell migration in a Rac1-dependent manner [60], raising the possibility that harmonin may have an active role in the assembly or maintenance of the F-actin cytoskeleton in stereocilia. The extent to which other proteins that bind to harmonin such as HARP and SANS [61,62] regulate its function in hair cells also remains to be established. In addition, it is unclear whether harmonin mediates CDH23 and PCDH15 function at tip links. It has been reported that harmonin is not expressed in functionally mature hair cells [56], but further experiments are necessary to clarify this point.

Myosin motor proteins and cadherins

Stereocilia of hair cells are densely packed with highly crosslinked actin filaments and do not contain classical transport vesicles. This raises the question how cell surface proteins such as CDH23 and PCDH15 are transported into stereocilia. As one possibility, receptors are inserted into the plasma membrane at the stereociliary base and diffuse passively into stereocilia. Alternatively, the receptors may be transported actively. Candidate molecules to participate in transport are actin-based molecular motors. Genetic studies in mice and humans have identified mutations in genes for several myosin motor proteins that cause deafness. One of these encodes Myo7a [63]. Mutations in the murine Myo7a gene lead to defects in hair bundles [64], reminiscent of the defects caused by mutations in harmonin, Cdh23, and Pcdh15 [12,18,35-37]. Myo7a binds to the cytoplasmic domain of PCDH15 (Fig. 5), and the localization of PCDH15 to stereocilia is disrupted in Myo7a mutant mice, while Myo7a localization is disrupted in Pcdh15 mutant mice [35]. Similarly, the localization of harmonin and Myo7a to stereocilia is affected in Myo7a- and harmonin-deficient mice, respectively [36]. The data are consistent with a model where complex formation between Myo7a, harmonin and PCDH15 is required for transport of the proteins into stereocilia. However, PCDH15 is still localized to stereocilia of harmonin mutant mice [36], suggesting that its localization is not dependent on harmonin and that a different mechanisms may account for mislocalization of the proteins in mutant mice. Similarly, CDH23 is localized to stereocilia independently of harmonin and Myo7a [35,36]. A candidate motor protein that could transport CDH23 is Myo1c. This model is consistent with three observations. First, Myo1c has initially been localized to the tips of stereocilia and subsequently to the upper insertion point of tip links [65-67]. Second, when CDH23 and Myo1c are expressed in heterologous cells, the two proteins can be co-immunoprecipitated (Fig. 4) [34]. Third, recombiant Myo1c protein binds to the tips of stereocilia from wild-type mice but not from Cdh23 mutant mice [68].

However, the mislocalization of cadherins, harmonin and myosin motor proteins in mutant mice could also be explained by alternative mechanisms. Disruptions in hair bundle morphology in mutant mice may secondarily affect the transport and localization of proteins. Moysin motor proteins may help to anchor adhesion complexes at specific locations within stereocilia. Interestingly, Myo1c is though to be the adaptation motor for the mechanotransduction channel [69,70]. Defects in gating mechanotransduction channels have also been observed in Myo7a-deficient mice [71]. Myosin motor proteins and cadherins could be integral part of larger protein complexes that establish cohesion in the hair bundle and adjust tension across the cell membrane which is critical for controlling the motion of hair bundles in response to sound stimulation and for controlling the opening and closing of mechanotransduction channels. It is also noteworthy to remember that CDH23 and PCDH15 are alternatively spliced generating isoforms with distinct cytoplasmic domains [13,16,20,34]. Different cadherin isoforms may assemble functionally distinct protein complexes in developing and adult hair cells.

Conclusions

Current models suggest that the linkages in developing hair bundles control hair bundle morphogenesis, while tip links in functionally mature hair cells are thought to gate mechanotransduction channels. The identification of CDH23 and PCDH15 as components of some of these linkages provides novel opportunities to define the function of the linkages by molecular approaches. One of the most intriguing conclusions from the recent findings is that tip links are asymmetric structures where PCDH15 and CDH23 are localized to opposite ends of tip links. These findings indicate that other components of the mechanotransduction machinery, such as the transduction channel itself, may also be localized asymmetrically at tip links. It seems likely that transient lateral links and kinociliary links in developing hair bundles show a similar asymmetry, but further studies are necessary to clarify the precise composition and structural organization of these linkages. The analysis of the function of proteins that bind to the cytoplasmic domains of CDH23 and PCDH15, and an understanding of the cellular processes that lead to asymmetry in protein distribution may shed light on the mechanism that lead to the establishment of polarity in the stereociliary bundle that is critical for hair cell function in mechanotransduction.

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible with funding from the NIH (DC005965, DC007704), the Bundy Family Foundation, and the Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended reading

- 1.Gumbiner BM. Regulation of cadherin-mediated adhesion in morphogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:622–634. doi: 10.1038/nrm1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halbleib JM, Nelson WJ. Cadherins in development: cell adhesion, sorting, and tissue morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3199–3214. doi: 10.1101/gad.1486806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hudspeth AJ. How hearing happens. Neuron. 1997;19:947–950. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Müller U, Evans AL. Mechanisms that regulate mechanosensory hair cell differentiation. Trends in Cell Biology. 2001;11:334–342. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vollrath MA, Kwan KY, Corey DP. The micromachinery of mechanotransduction in hair cells. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:339–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodyear RJ, Marcotti W, Kros CJ, Richardson GP. Development and properties of stereociliary link types in hair cells of the mouse cochlea. J Comp Neurol. 2005;485:75–85. doi: 10.1002/cne.20513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed ZM, Riazuddin S, Wilcox ER. The molecular genetics of Usher syndrome. Clin Genet. 2003;63:431–444. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2003.00109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Amraoui A, Petit C. Usher I syndrome: unravelling the mechanisms that underlie the cohesion of the growing hair bundle in inner ear sensory cells. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4593–4603. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bolz H, von Brederlow B, Ramirez A, Bryda EC, Kutsche K, Nothwang HG, Seeliger M, M del CSC, Vila MC, Molina OP, et al. Mutation of CDH23, encoding a new member of the cadherin gene family, causes Usher syndrome type 1D. Nat Genet. 2001;27:108–112. doi: 10.1038/83667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bork JM, Peters LM, Riazuddin S, Bernstein SL, Ahmed ZM, Ness SL, Polomeno R, Ramesh A, Schloss M, Srisailpathy CR, et al. Usher syndrome 1D and nonsyndromic autosomal recessive deafness DFNB12 are caused by allelic mutations of the novel cadherin-like gene CDH23. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:26–37. doi: 10.1086/316954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Palma F, Holme RH, Bryda EC, Belyantseva IA, Pellegrino R, Kachar B, Steel KP, Noben-Trauth K. Mutations in Cdh23, encoding a new type of cadherin, cause stereocilia disorganization in waltzer, the mouse model for Usher syndrome type 1D. Nat Genet. 2001;27:103–107. doi: 10.1038/83660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson SM, Householder DB, Coppola V, Tessarollo L, Fritzsch B, Lee EC, Goss D, Carlson GA, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA. Mutations in Cdh23 cause nonsyndromic hearing loss in waltzer mice. Genomics. 2001;74:228–233. doi: 10.1006/geno.2001.6554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Palma F, Pellegrino R, Noben-Trauth K. Genomic structure, alternative splice forms and normal and mutant alleles of cadherin 23 (Cdh23) Gene. 2001;281:31–41. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00761-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lagziel A, Ahmed ZM, Schultz JM, Morell RJ, Belyantseva IA, Friedman TB. Spatiotemporal pattern and isoforms of cadherin 23 in wild type and waltzer mice during inner ear hair cell development. Dev Biol. 2005;280:295–306. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michel V, Goodyear RJ, Weil D, Marcotti W, Perfettini I, Wolfrum U, Kros CJ, Richardson GP, Petit C. Cadherin 23 is a component of the transient lateral links in the developing hair bundles of cochlear sensory cells. Dev Biol. 2005;280:281–294. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siemens J, Kazmierczak P, Reynolds A, Sticker M, Littlewood-Evans A, Muller U. The Usher syndrome proteins cadherin 23 and harmonin form a complex by means of PDZ-domain interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14946–14951. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232579599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmed ZM, Riazuddin S, Bernstein SL, Ahmed Z, Khan S, Griffith AJ, Morell RJ, Friedman TB, Wilcox ER. Mutations of the protocadherin gene PCDH15 cause Usher syndrome type 1F. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:25–34. doi: 10.1086/321277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alagramam KN, Murcia CL, Kwon HY, Pawlowski KS, Wright CG, Woychik RP. The mouse Ames waltzer hearing-loss mutant is caused by mutation of Pcdh15, a novel protocadherin gene. Nat Genet. 2001;27:99–102. doi: 10.1038/83837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alagramam KN, Yuan H, Kuehn MH, Murcia CL, Wayne S, Srisailpathy CR, Lowry RB, Knaus R, Van Laer L, Bernier FP, et al. Mutations in the novel protocadherin PCDH15 cause Usher syndrome type 1F. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1709–1718. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.16.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmed ZM, Goodyear R, Riazuddin S, Lagziel A, Legan PK, Behra M, Burgess SM, Lilley KS, Wilcox ER, Riazuddin S, et al. The tip-link antigen, a protein associated with the transduction complex of sensory hair cells, is protocadherin-15. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7022–7034. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1163-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ““The study analyses the genomic structure of PCDH15 and describes several new exons that have not been reported earlier and are alternatively spliced to generate several PCDH15 isoforms. Some of these isoforms contain distinct cytoplasmic domains that have been named CD1, CD2 and CD3. Analysis of protein localization with antibodies demonstrates unique expression patterns of PCDH15-CD1, -CD2 and -CD3 in hair cell stereocilia. At least in avian hair cells PCDH15-CD1 and PCDH15-CD3 appears to be localized in the region of stereocilia where tip links are located.

- 21.Ahmed ZM, Riazuddin S, Ahmad J, Bernstein SL, Guo Y, Sabar MF, Sieving P, Griffith AJ, Friedman TB, Belyantseva IA, et al. PCDH15 is expressed in the neurosensory epithelium of the eye and ear and mutant alleles are responsible for both USH1F and DFNB23. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:3215–3223. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alagramam KN, Miller ND, Adappa ND, Pitts DR, Heaphy JC, Yuan H, Smith RJ. Promoter, alternative splice forms, and genomic structure of protocadherin 15. Genomics. 2007;90:482–492. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haywood-Watson RJ, 2nd, Ahmed ZM, Kjellstrom S, Bush RA, Takada Y, Hampton LL, Battey JF, Sieving PA, Friedman TB. Ames Waltzer deaf mice have reduced electroretinogram amplitudes and complex alternative splicing of Pcdh15 transcripts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:3074–3084. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rouget-Quermalet V, Giustiniani J, Marie-Cardine A, Beaud G, Besnard F, Loyaux D, Ferrara P, Leroy K, Shimizu N, Gaulard P, et al. Protocadherin 15 (PCDH15): a new secreted isoform and a potential marker for NK/T cell lymphomas. Oncogene. 2006;25:2807–2811. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Astuto LM, Bork JM, Weston MD, Askew JW, Fields RR, Orten DJ, Ohliger SJ, Riazuddin S, Morell RJ, Khan S, et al. CDH23 mutation and phenotype heterogeneity: a profile of 107 diverse families with Usher syndrome and nonsyndromic deafness. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:262–275. doi: 10.1086/341558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ben-Yosef T, Ness SL, Madeo AC, Bar-Lev A, Wolfman JH, Ahmed ZM, Desnick RJ, Willner JP, Avraham KB, Ostrer H, et al. A mutation of PCDH15 among Ashkenazi Jews with the type 1 Usher syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1664–1670. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bork JM, Morell RJ, Khan S, Riazuddin S, Wilcox ER, Friedman TB, Griffith AJ. Clinical presentation of DFNB12 and Usher syndrome type 1D. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;61:145–152. doi: 10.1159/000066829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Brouwer AP, Pennings RJ, Roeters M, Van Hauwe P, Astuto LM, Hoefsloot LH, Huygen PL, van den Helm B, Deutman AF, B JM, et al. Mutations in the calcium-binding motifs of CDH23 and the 35delG mutation in GJB2 cause hearing loss in one family. Hum Genet. 2003;112:156–163. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0833-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le Guedard S, Faugere V, Malcolm S, Claustres M, Roux AF. Large genomic rearrangements within the PCDH15 gene are a significant cause of USH1F syndrome. Mol Vis. 2007;13:102–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu XZ, Blanton SH, Bitner-Glindzicz M, Pandya A, Landa B, MacArdle B, Rajput K, Bellman S, Webb BT, Ping X, et al. Haplotype analysis of the USH1D locus and genotype-phenotype correlations. Clin Genet. 2001;60:58–62. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2001.600109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ouyang XM, Yan D, Du LL, Hejtmancik JF, Jacobson SG, Nance WE, Li AR, Angeli S, Kaiser M, Newton V, et al. Characterization of Usher syndrome type I gene mutations in an Usher syndrome patient population. Hum Genet. 2005;116:292–299. doi: 10.1007/s00439-004-1227-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roux AF, Faugere V, Le Guedard S, Pallares-Ruiz N, Vielle A, Chambert S, Marlin S, Hamel C, Gilbert B, Malcolm S, et al. Survey of the frequency of USH1 gene mutations in a cohort of Usher patients shows the importance of cadherin 23 and protocadherin 15 genes and establishes a detection rate of above 90% J Med Genet. 2006;43:763–768. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.041954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rzadzinska AK, Derr A, Kachar B, Noben-Trauth K. Sustained cadherin 23 expression in young and adult cochlea of normal and hearing-impaired mice. Hear Res. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siemens J, Lillo C, Dumont RA, Reynolds A, Williams DS, Gillespie PG, Muller U. Cadherin 23 is a component of the tip link in hair-cell stereocilia. Nature. 2004;428:950–955. doi: 10.1038/nature02483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Senften M, Schwander M, Kazmierczak P, Lillo C, Shin JB, Hasson T, Geleoc GS, Gillespie PG, Williams D, Holt JR, et al. Physical and functional interaction between protocadherin 15 and myosin VIIa in mechanosensory hair cells. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2060–2071. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4251-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ““Previous studies have concluded that mutations in Pcdh15 only affect the morphological differentiation of cochlear hair cells. The current study shows that vestibular hair cells are also affected and that the phenotype of Pcdh15-deficient mice closely resembles the phenotype of Myo7a-deficient mice with defects in hair bundle cohesion and polarity. Biochemical studies show that Myo7a binds directly to the cytoplasmic domain of PCDH15-CD1 and that the localization of Myo7a and PCDH15-CD1 in stereocilia is interdependent.

- 36.Lefevre G, Michel V, Weil D, Lepelletier L, Bizard E, Wolfrum U, Hardelin JP, Petit C. A core cochlear phenotype in USH1 mouse mutants implicates fibrous links of the hair bundle in its cohesion, orientation and differential growth. Development. 2008;135:1427–1437. doi: 10.1242/dev.012922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ““The study compares hair bundle morphology in mice with mutations in genes for proteins that have been linked to USH1. The study confirms earlier findings that hair bundle cohesion is similarly affected in all USH1 model mice, and reveals defects in the elongation of stereocilia that have not been previously reported. Histochemical data provide evidence that the localization of some of the USH1 proteins in hair bundles is interdependent, consistent with the model that USHS1 proteins act in common molecular pathways.

- 37.Pawlowski KS, Kikkawa YS, Wright CG, Alagramam KN. Progression of inner ear pathology in Ames waltzer mice and the role of protocadherin 15 in hair cell development. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2006;7:83–94. doi: 10.1007/s10162-005-0024-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.D'Alterio C, Tran DD, Yeung MW, Hwang MS, Li MA, Arana CJ, Mulligan VK, Kubesh M, Sharma P, Chase M, et al. Drosophila melanogaster Cad99C, the orthologue of human Usher cadherin PCDH15, regulates the length of microvilli. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:549–558. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kazmierczak P, Sakaguchi H, Tokita J, Wilson-Kubalek EM, Milligan RA, Muller U, Kachar B. Cadherin 23 and protocadherin 15 interact to form tip-link filaments in sensory hair cells. Nature. 2007;449:87–91. doi: 10.1038/nature06091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ““The authors show that tip links in mechanosensory hair cells are asymmetric cell adhesion complexes that are formed by CHD23 homodimers interacting in trans with PCDH15 homodimers. The findings suggest that the mechanotransduction machinery in hair cells has an inherent asymmetry.

- 40.Adato A, Lefevre G, Delprat B, Michel V, Michalski N, Chardenoux S, Weil D, El-Amraoui A, Petit C. Usherin, the defective protein in Usher syndrome type IIA, is likely to be a component of interstereocilia ankle links in the inner ear sensory cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3921–3932. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGee J, Goodyear RJ, McMillan DR, Stauffer EA, Holt JR, Locke KG, Birch DG, Legan PK, White PC, Walsh EJ, et al. The very large G-protein-coupled receptor VLGR1: a component of the ankle link complex required for the normal development of auditory hair bundles. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6543–6553. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0693-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ““The study shows that VLGR1 is a component of ankle links in hair bundles. Immunolocalization studies demonstrate that VLGR1 is localized to the ankle links in hair bundles, that ankle links are absent in mice with mutations in VLGR1, and that ankle links are required for the normal development of cochlear hair bundles.

- 42.Michalski N, Michel V, Bahloul A, Lefevre G, Barral J, Yagi H, Chardenoux S, Weil D, Martin P, Hardelin JP, et al. Molecular characterization of the ankle-link complex in cochlear hair cells and its role in the hair bundle functioning. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6478–6488. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0342-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; “The authors show that immunoreactivity to Usherin, vezatin and whirlin can be observed at the base of stereocilia in wild-type but not VLGR-1 mutant mice, suggesting that the proteins are components of the ankle link complex in hair cells. Localization of other proteins such as CDH23 and Adenylyl cyclase 6 is also affected, indicating a more general defects in protein localization in hair cells of mutant mice. Mechanotransduction currents can still be evoked but directional sensitivity of the hair bundle to mechanical stimulation is perturbed.

- 43.Goodyear RJ, Legan PK, Wright MB, Marcotti W, Oganesian A, Coats SA, Booth CJ, Kros CJ, Seifert RA, Bowen-Pope DF, et al. A receptor-like inositol lipid phosphatase is required for the maturation of developing cochlear hair bundles. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9208–9219. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-27-09208.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pickles JO, Comis SD, Osborne MP. Cross-links between stereocilia in the guinea pig organ of Corti, and their possible relation to sensory transduction. Hear Res. 1984;15:103–112. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(84)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Assad JA, Shepherd GM, Corey DP. Tip-link integrity and mechanical transduction in vertebrate hair cells. Neuron. 1991;7:985–994. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90343-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao Y, Yamoah EN, Gillespie PG. Regeneration of broken tip links and restoration of mechanical transduction in hair cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:15469–15474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kachar B, Parakkal M, Kurc M, Zhao Y, Gillespie PG. High-resolution structure of hair-cell tip links. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13336–13341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.24.13336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsuprun V, Goodyear RJ, Richardson GP. The structure of tip links and kinocilial links in avian sensory hair bundles. Biophys J. 2004;87:4106–4112. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.049031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boggon TJ, Murray J, Chappuis-Flament S, Wong E, Gumbiner BM, Shapiro L. C-cadherin ectodomain structure and implications for cell adhesion mechanisms. Science. 2002;296:1308–1313. doi: 10.1126/science.1071559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sollner C, Rauch GJ, Siemens J, Geisler R, Schuster SC, Müller U, Nicolson T. Mutations in cadherin 23 affect tip links in zebrafish sensory hair cells. Nature. 2004;428:955–959. doi: 10.1038/nature02484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Furness DN, Katori Y, Nirmal Kumar B, Hackney CM. The dimensions and structural attachments of tip links in mammalian cochlear hair cells and the effects of exposure to different levels of extracellular calcium. Neuroscience. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ““The authors compare the ultrustructural characteristics of tip links in guinea-pig cochlear hair cells with the molecular features of the CDH23-PCDH15 complex. The molecular dimensions of tip links vary with the Ca2+ concentration, where the length of tip links under physiological conditions was determined to be ∼185 nm, which is in excellent agreement with the ∼180 nm length that has been reported for the CDH23-PCDH15 complex.

- 52.Anniko M, Wroblewski R. Ionic environment of cochlear hair cells. Hear Res. 1986;22:279–293. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(86)90104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gillespie PG, Walker RG. Molecular basis of mechanosensory transduction. Nature. 2001;413:194–202. doi: 10.1038/35093011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Denk W, Holt JR, Shepherd GM, Corey DP. Calcium imaging of single stereocilia in hair cells: localization of transduction channels at both ends of tip links. Neuron. 1995;15:1311–1321. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adato A, Michel V, Kikkawa Y, Reiners J, Alagramam KN, Weil D, Yonekawa H, Wolfrum U, El-Amraoui A, Petit C. Interactions in the network of Usher syndrome type 1 proteins. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:347–356. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boeda B, El-Amraoui A, Bahloul A, Goodyear R, Daviet L, Blanchard S, Perfettini I, Fath KR, Shorte S, Reiners J, et al. Myosin VIIa, harmonin and cadherin 23, three Usher I gene products that cooperate to shape the sensory hair cell bundle. Embo J. 2002;21:6689–6699. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reiners J, Marker T, Jurgens K, Reidel B, Wolfrum U. Photoreceptor expression of the Usher syndrome type 1 protein protocadherin 15 (USH1F) and its interaction with the scaffold protein harmonin (USH1C) Mol Vis. 2005;11:347–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Johnson KR, Gagnon LH, Webb LS, Peters LL, Hawes NL, Chang B, Zheng QY. Mouse models of USH1C and DFNB18: phenotypic and molecular analyses of two new spontaneous mutations of the Ush1c gene. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:3075–3086. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yan D, Li F, Hall ML, Sage C, Hu WH, Giallourakis C, Upadhyay G, Ouyang XM, Du LL, Bethea JR, et al. An isoform of GTPase regulator DOCK4 localizes to the stereocilia in the inner ear and binds to harmonin (USH1C) J Mol Biol. 2006;357:755–764. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hiramoto K, Negishi M, Katoh H. Dock4 is regulated by RhoG and promotes Rac-dependent cell migration. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:4205–4216. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Johnston AM, Naselli G, Niwa H, Brodnicki T, Harrison LC, Gonez LJ. Harp (harmonin-interacting, ankyrin repeat-containing protein), a novel protein that interacts with harmonin in epithelial tissues. Genes Cells. 2004;9:967–982. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2004.00776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weil D, El-Amraoui A, Masmoudi S, Mustapha M, Kikkawa Y, Laine S, Delmaghani S, Adato A, Nadifi S, Zina ZB, et al. Usher syndrome type I G (USH1G) is caused by mutations in the gene encoding SANS, a protein that associates with the USH1C protein, harmonin. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:463–471. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weil D, Blanchard S, Kaplan J, Guilford P, Gibson F, Walsh J, Mburu P, Varela A, Levilliers J, Weston MD, et al. Defective myosin VIIA gene responsible for Usher syndrome type 1B. Nature. 1995;374:60–61. doi: 10.1038/374060a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gibson F, Walsh J, Mburu P, Varela A, Brown KA, Antonio M, Beisel KW, Steel KP, Brown SD. A type VII myosin encoded by the mouse deafness gene shaker-1. Nature. 1995;374:62–64. doi: 10.1038/374062a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Garcia JA, Yee AG, Gillespie PG, Corey DP. Localization of myosin-Ibeta near both ends of tip links in frog saccular hair cells. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8637–8647. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-08637.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gillespie PG, Wagner MC, Hudspeth AJ. Identification of a 120 kd hair-bundle myosin located near stereociliary tips. Neuron. 1993;11:581–594. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Steyger PS, Gillespie PG, Baird RA. Myosin Ibeta is located at tip link anchors in vestibular hair bundles. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4603–4615. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04603.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Phillips KR, Tong S, Goodyear R, Richardson GP, Cyr JL. Stereociliary myosin-1c receptors are sensitive to calcium chelation and absent from cadherin 23 mutant mice. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10777–10788. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1847-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ““The molecular motor protein Myo1c functions in adaptation of hair cell-responses to sustained mechanical stimuli. In vitro studies have shown that Myo1c can be co-immunoprecipitated with CDH23. Using an in situ binding assay with recombinant Myo1c protein, the authors show that Myo1c interacts with molecules at stereociliary tips and that localization is perturbed when tip links are disrupted. Myo1c also does not bind to stereocilia from mice that lack CDH23, suggesting that Myo1c and CDH23 interact at tips of sterocilia.

- 69.Holt JR, Gillespie SK, Provance DW, Shah K, Shokat KM, Corey DP, Mercer JA, Gillespie PG. A chemical-genetic strategy implicates myosin-1c in adaptation by hair cells. Cell. 2002;108:371–381. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00629-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stauffer EA, Scarborough JD, Hirono M, Miller ED, Shah K, Mercer JA, Holt JR, Gillespie PG. Fast adaptation in vestibular hair cells requires Myosin-1c activity. Neuron. 2005;47:541–553. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kros CJ, Marcotti W, van Netten SM, Self TJ, Libby RT, Brown SD, Richardson GP, Steel KP. Reduced climbing and increased slipping adaptation in cochlear hair cells of mice with Myo7a mutations. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:41–47. doi: 10.1038/nn784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]