Abstract

Electrophysiological and pharmacological studies have demonstrated that alpha-1 adrenergic receptor (α1AR) activation facilitates dopamine (DA) transmission in the striatum and ventral midbrain. However, because little is known about the localization of α1ARs in dopaminergic regions, the substrate(s) and mechanism(s) underlying this facilitation of DA signaling are poorly understood. To address this issue, we used light and electron microscopy immunoperoxidase labeling to examine the cellular and ultrastructural distribution of α1ARs in the caudate putamen, nucleus accumbens, ventral tegmental area, and substantia nigra in the rat. Analysis at the light microscopic level revealed α1AR immunoreactivity mainly in neuropil, with occasional staining in cell bodies. At the electron microscopic level, α1AR immunoreactivity was found primarily in presynaptic elements, with scarce postsynaptic labeling. Unmyelinated axons and about 30–50% terminals forming asymmetric synapses contained the majority of presynaptic labeling in the striatum and midbrain, while in the midbrain a subset of terminals forming symmetric synapses also displayed immunoreactivity. Postsynaptic labeling was scarce in both striatal and ventral midbrain regions. On the other hand, only 3–6% of spines displayed α1AR immunoreactivity in the caudate putamen and nucleus accumbens,. These data suggest that the facilitation of dopaminergic transmission by α1ARs in the mesostriatal system is probably achieved primarily by pre-synaptic regulation of glutamate and GABA release.

Keywords: norepinephrine, Parkinson’s disease, addiction, dopamine, axon, electron microscopy

Introduction

Norepinephrine (NE) is a monoamine neurotransmitter that is synthesized in distinct brainstem nuclei that project widely throughout the brain. The mesolimbic (ventral tegmental area, VTA; nucleus accumbens, NAc), and nigrostriatal (substantia nigra, SN; caudate putamen, CP) dopamine (DA) systems receive noradrenergic innervation. The locus coeruleus (LC), A1 and A2 noradrenergic nuclei project directly to midbrain DA neurons and to the dorsal and ventral striatum (Glowinski and Iversen, 1966, Lindvall and Bjorklund, 1974, Liprando et al., 2004), where in general, NE facilitates DA transmission (reviewed by Weinshenker and Schroeder, 2007). For example, stimulation of the locus coeruleus (LC), the major brainstem noradrenergic nucleus, promotes burst firing of midbrain DA neurons (Grenhoff et al., 1993), while pharmacological or genetic NE depletion diminishes basal and evoked striatal DA release (Russell et al., 1989, Lategan et al., 1990, Schank et al., 2006).

Of the three classes of adrenergic receptors (Gilsbach and Hein, 2008), α1-adrenergic receptor (α1AR) activation likely accounts for the majority of the noradrenergic influence on DA transmission. The increase in DA neuron burst firing induced by LC stimulation can be blocked by systemic administration of the α1AR antagonist prazosin (Grenhoff and Svensson, 1993). Pharmacological or genetic blockade of α1ARs can also attenuate psychostimulant-induced locomotor activity and DA release in the NAc (Darracq et al., 1998, Weinshenker et al., 2002, Auclair et al., 2004). While the importance of α1AR activation in the prefrontal cortex for the regulation of striatal DA release has been well described (Blanc et al., 1994, Darracq et al., 1998), local α1ARs in the mesolimbic and nigrostriatal pathways also contribute to DA transmission and behavior. For instance, the stimulation of DA neuron burst firing by NE in midbrain slices can be mimicked by the α1AR agonist phenylephrine and blocked by the α1AR antagonist prazosin (Grenhoff et al., 1993, Grenhoff and Svensson, 1993). Direct infusion of prazosin into the striatum reduces basal extracellular DA levels (Sommermeyer et al., 1995), and intra-VTA infusion of prazosin attenuates the facilitation of DA release in the NAc caused by intra-VTA infusion of amphetamine (Pan et al., 1996). Finally, direct infusion of NE into the NAc induces locomotor activity in rats, while infusion of the α1AR antagonist into the NAc attenuates exploratory activity in mice (Svensson and Ahlenius, 1982, Stone et al., 2004), and striatal NE loss exacerbates L-DOPA-induced dyskinesias in DA-depleted rats (Fulceri et al., 2007).

Despite these behavioral, pharmacological, and electrophysiological data showing a significant regulatory influence of NE on the dopaminergic system, the interpretation of these functional studies remains speculative because very little information is available on the precise localization of α1ARs within the mesolimbic and nigrostriatal systems. While α1ARs are detectable in the NAc using radioligand binding and in the dorsal striatum by in situ hybridization, α1AR mRNA has not been found in accumbal neurons (Young and Kuhar, 1980, Rainbow and Biegon, 1983, Jones et al., 1985, Morrow and Creese, 1986, Day et al., 1997, Domyancic and Morilak, 1997). Furthermore, neither radioligand binding nor in situ hybridization have reliably detected α1ARs in midbrain DA neurons (Jones et al., 1985, Palacios et al., 1987, Pieribone et al., 1994), although the α1bAR was detected in the VTA using laser capture microdissection and expression microarray analysis (Greene et al., 2005). Although informative, the functional significance of these localization studies is limited by the lack of data on the exact sites of α1AR protein expression in the mesolimbic and nigrostriatal DA systems. Therefore, in order to further understand the potential substrate that underlies NE-mediated regulation of DA transmission, we used specific antibodies at the electron microscopic level (Nakadate et al., 2006) to characterize the ultrastructural localization of α1ARs in the rat mesolimbic and nigrostriatal DA pathways.

Experimental Procedures

Animals and tissue preparation

Six male Sprague Dawley rats (250 g; 2 months old) were used for this study. All procedures were approved by the animal care and use committee of Emory University and conform to the U.S. National Institutes of Health guidelines. All rats were anesthetized with a cocktail of ketamine (60–100 mg/kg i.p.) and dormitor (0.1 mg/kg). Rats were transcardially perfused with cold oxygenated Ringer’s solution, followed by a fixative containing 2% paraformaldehyde and 3.75% acrolein (or 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.1% glutaraldehyde) in phosphate buffer (0.1 M; pH 7.4). After perfusion, brains were removed from the skull and postfixed in 2% (or 4%) paraformaldehyde for 24hrs, cut into 60 µm sections with a vibrating microtome, and stored in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to 4°C until processing for immunocytochemistry. Prior to immunocytochemical processing, a series of sections including the caudate putamen, nucleus accumbens shell and nucleus accumbens core or the ventral tegmental area and substantia nigra were placed in a 1% sodium borohydride solution for 20 minutes, then washed with PBS.

Alpha-1 receptor antiserum

Commercially available polyclonal antibodies to the α1AR (Affinity BioReagents Inc.; Golden, CO, USA) were used at a concentration of 1:1000 as described in the original manuscript that published data on the synthesis and specificity of this antiserum (Nakadate et al., 2006). The antibody was raised against the amino acids 339–349 (FSREKKAAK) of the 3rd intracellular loop of the human α1AR, which is common to all alpha-1 receptor subtypes, but is not found in other GPCRs (Stewart et al., 1994, Schwinn et al., 1995, Strausberg et al., 2002). Western blots in rat brain tissue identified a single band between 70–80 kDa (Nakadate et al., 2006), which was eliminated by preadsorption with preincubation of a synthetic peptide corresponding to the α1AR antibody epitope.

Immunoperoxidase labeling for electron microscopy

After sodium borohydride treatment, sections were placed in cryoprotectant solution for 20 minutes (PB 0.05 M, pH 7.4, 25% sucrose, 10% glycerol), frozen at −80°C for 20 minutes, returned to a decreasing gradient of cryoprotectant solutions, and rinsed in PBS. Sections were then pre-incubated for 1 hour at room temperature (RT) in PBS containing 10% normal goat serum (NGS), 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and then followed by incubation in primary antibody solution containing 1% NGS, 1% BSA, and the α1AR antibodies (1:1000) for 48 hours at 4°C. After 3 rinses in PBS, sections were incubated in secondary biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgGs (1:200 dilution; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 90 minutes. The sections were rinsed again in PBS and then incubated for another 90 minutes with the avidin-biotin peroxidase complex (ABC) at a dilution of 1:100 (Vector Laboratories). Then, sections were washed in PBS and Tris buffer (50 mM; pH 7.6) and transferred to a solution containing 0.025% 3,3’-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB; Sigma), 1 mM imidazole, and 0.005% hydrogen peroxide in Tris buffer for 10 minutes. Sections were then rinsed in PB (0.1 M, pH 7.4) and treated with 1% OsO4 for 20 minutes. The tissue was then returned to PB and dehydrated with increasing concentrations of ethanol. With exposure to 70% ethanol, 1% uranyl acetate was added to the solution and the tissue was incubated for 35 minutes to increase the contrast of the tissue at the electron microscope. After dehydration, sections were treated with propylene oxide and embedded in epoxy resin for 12 hours (Durcupan ACM; Fluka, Buschs, Switzerland), mounted onto slides, and placed in a 60°C oven for 48 hours. Samples of the caudate putamen, nucleus accumbens shell and core, ventral tegmental area, and substantia nigra were mounted onto resin blocks, and cut into 60 nm sections with an ultramicrotome (Leica Ultracut T2). The 60nm sections were collected on Pioloform coated copper grids, stained with lead citrate for 5 minutes to enhance tissue contrast, and examined on the Zeiss EM-10C electron microscope. Electron micrographs were taken and saved with a CCD camera (DualView 300W; Gatan, Inc., Pleasanton, CA) controlled by DigitalMicrograph software (version 3.10.1; Gatan, Inc.). Some of the digitally acquired electron micrographs were adjusted only for brightness and/or contrast in either the DigitalMicrograph software or Adobe Photoshop 8.0. Micrographs were then compiled to figures using Adobe Illustrator 11.0.

Data Analysis

Data were collected from a total of 27 blocks of tissue, i.e. 1 block/animal in each brain region from 5–6 rats. About 100 electron micrographs of randomly selected immunoreactive elements were digitized at X25,000 from each rat per brain region, which resulted in a total tissue surface of 19,851 µm2 for the caudate putamen, 30,332 µm2 for the nucleus accumbens shell, 29,946 µm2 for the nucleus accumbens core, 25,502 µm2 for the VTA and 28,159 µm2 for the SN. Labeled elements were categorized as dendrites, spines, axons, axon terminals and glia on the basis of ultrastructural features described by Peters and colleagues (Peters et al., 1991). The density of labeled elements was calculated by dividing the number of elements labeled by the total area of tissue examined. Significant differences were assessed by using SigmaStat software for one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s posthoc test. The density of labeled elements was compared within brain regions. The percentage of labeled terminals forming asymmetric synapses and the percentage of labeled spines in the nucleus accumbens and caudate putamen were compared between brain regions by determining the proportion of labeled and unlabeled terminals involved in asymmetric synaptic contact or spines in ultrathin sections collected from the surface of striatal and accumbens tissue with complete antibody penetration. One more block was taken in CP, VTA and SNc to examine the general pattern of labeling in immunoreactive neuronal cell bodies.

Results

Light Microscopy

At the light microscopic level, the immunoperoxidase labeling in both striatal and ventral midbrain regions was mainly associated with fine punctate structures. In both regions, neuronal cell body labeling was scarce, except for the cell bodies of a small proportion of large striatal interneurons and putative dopaminergic neurons in the SNc that displayed low to moderate immunoreactivity. In contrast, putative striatal projection neurons and cells in the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr) did not display a significant level of immunoreactivity (Fig. 3A). The rich neuropil labeling is consistent with the large number of immunoreactive unmyelinated axons seen at the electron microscope level (see below).

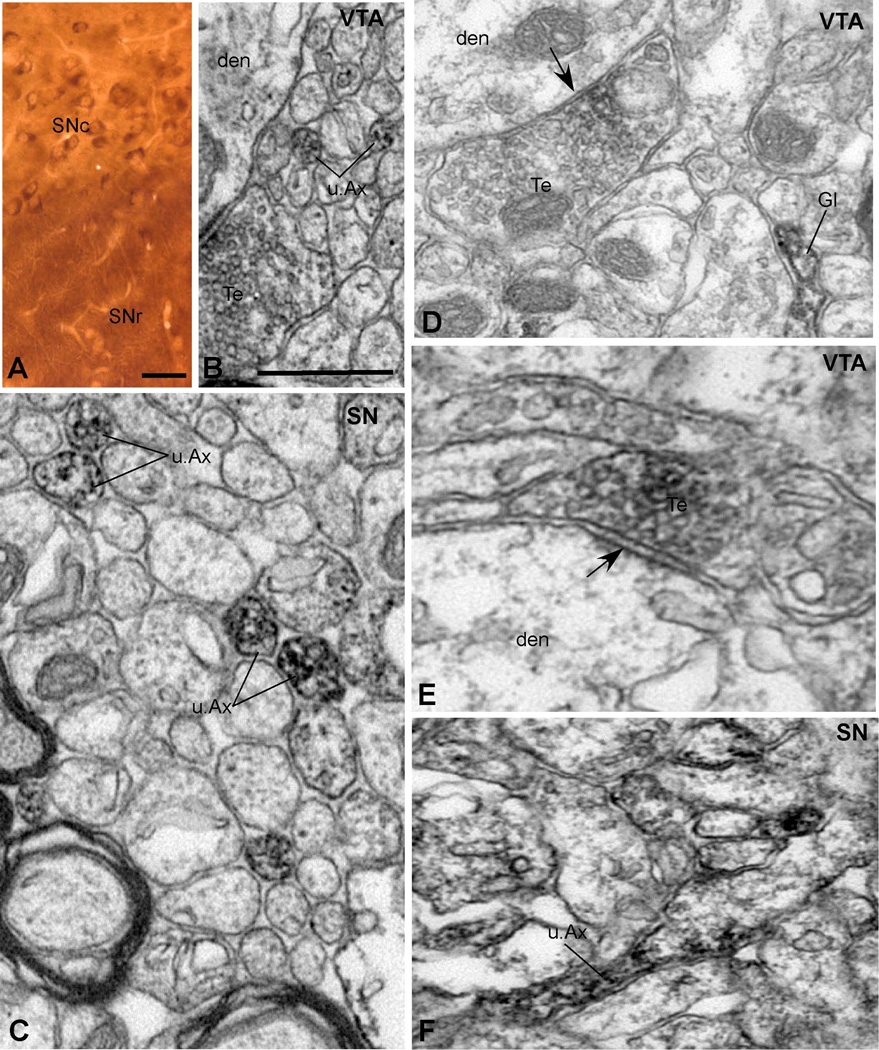

Figure 3. Representative examples of α1AR-immunoreactive elements in the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area of rat.

(A) Examples of immunoreactive neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc), but not the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr) (B) Examples of labeled unmyelinated axons (u.Ax) and an axon terminal (Te) that forms an asymmetric axo-dendritic synapse in the ventral tegmental area (VTA). (D, E) Labeled boutons (Te) forming symmetric axo-dendritic synapses (arrow) in the VTA. An immunoreactive glial process (Gl) is also shown in (D). (C, F) Examples of immunoreactive unmyelinated axons (u.Ax) in the SN. Scale bars: 0.5 µm.

Electron Microscopy: Caudate Putamen and Nucleus Accumbens

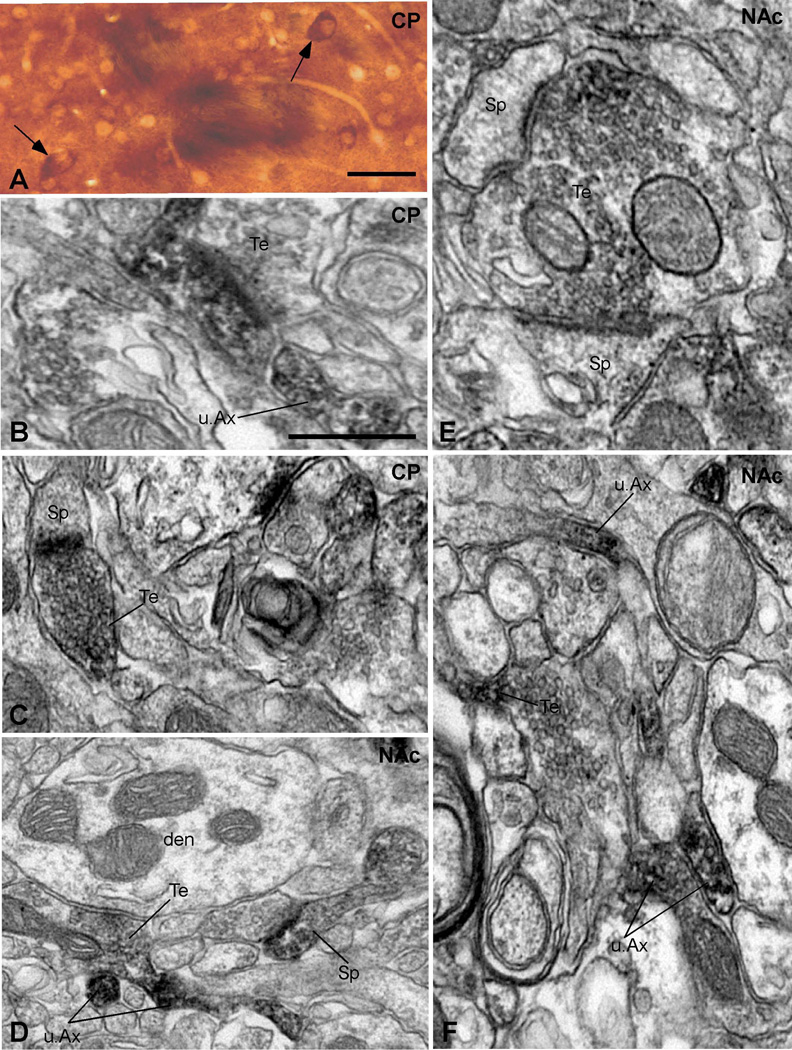

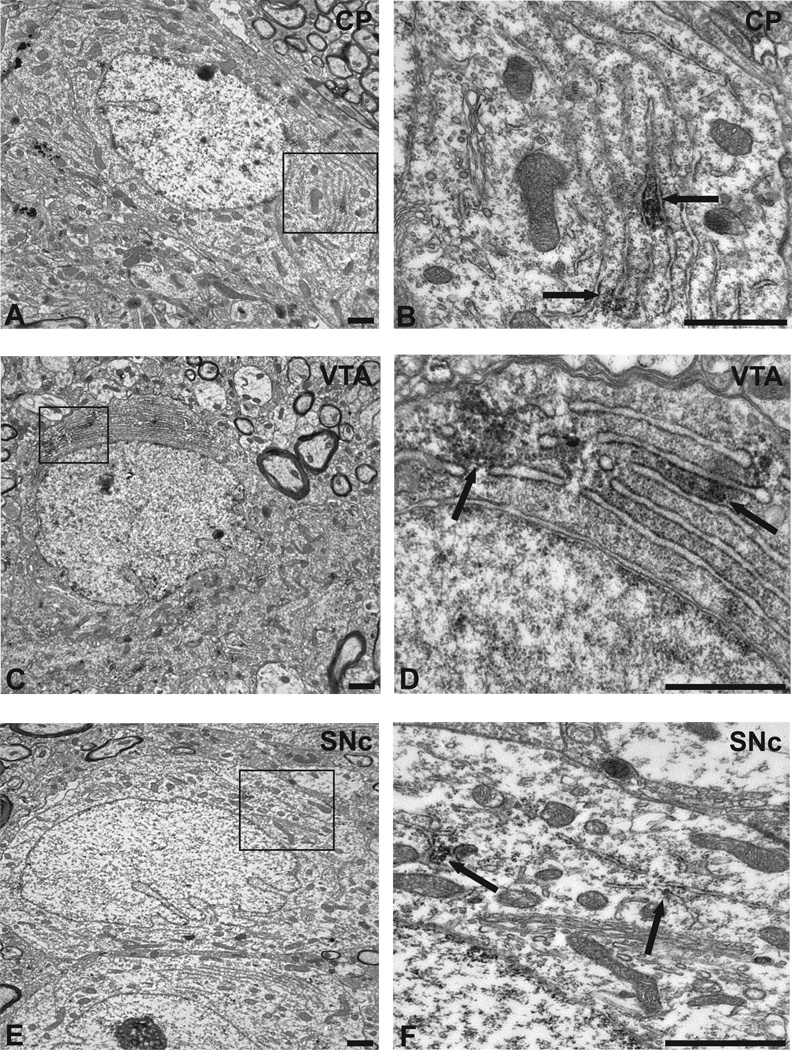

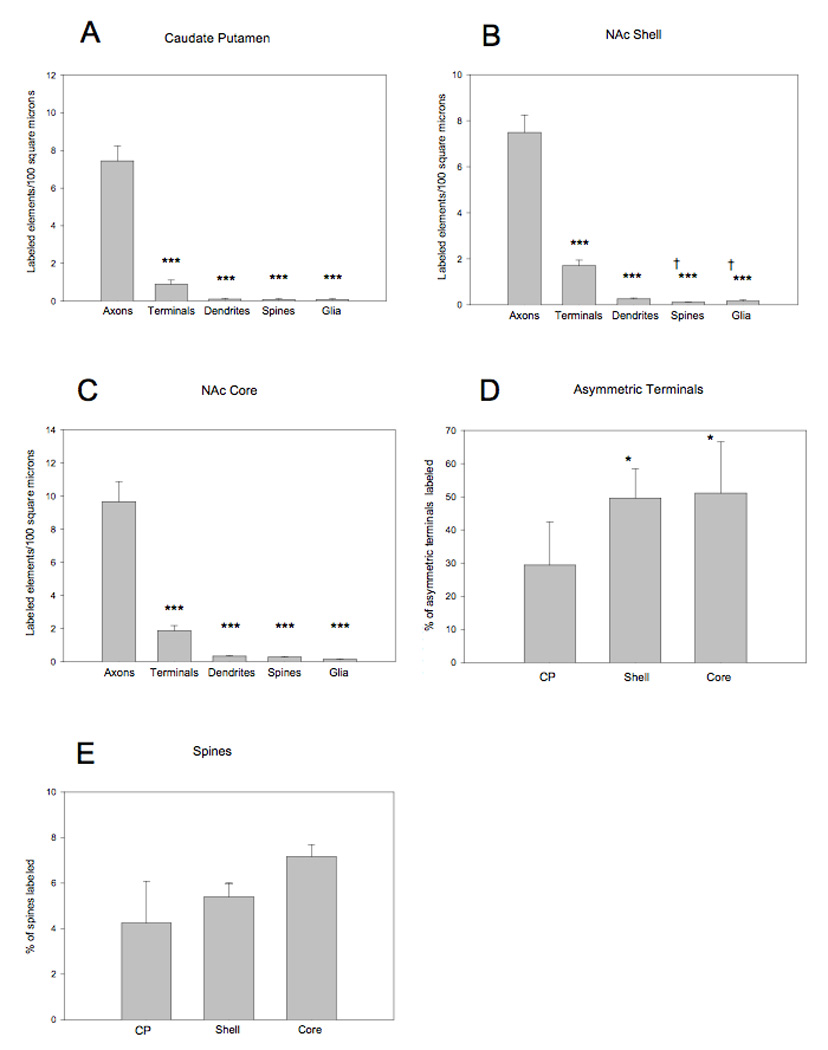

In general, α1AR labeling in both the nucleus accumbens (NAc) and caudate putamen (CP) was localized primarily in presynaptic elements including unmyelinated axons and axon terminals. To a much lower extent, labeling was also detected in postsynaptic structures such as dendrites and spines, but these accounted for less than 5% of total labeled neuronal elements. In both regions, sparse labeling was found in glia (Fig. 1B–F, Fig. 2A–C). Labeling in axons was significantly greater than in any other elements identified in the NAc shell (F(4,25) =78.258, p<0.001; Fig. 2B), NAc core (F(4,25) =52.958, p<0.001; Figs 2B,C) and CP (F(4,20) =76.782, p<0.001; Fig. 2A). In the NAc shell, but not the core or the CP, the prevalence of terminal labeling was significantly greater than in spines or glia (F(4,25) =78.258, p<0.001; Fig. 2B). In other striatal regions, no significant difference was found between the relative abundance of labeled terminals, dendrites, spines and glia (Figs. 2A–C). The majority of immunoreactive terminals displayed the ultrastructural features of putative glutamatergic boutons. In total, 771 terminals were identified in the CP, 1054 in the NAc shell, and 1152 in the NAc core. In the CP, 456 of identified terminals formed a clear asymmetric synapse and 130 of these (~30%) displayed α1AR immunoreactivity (Fig. 1B,C,Fig. 2). This proportion was significantly higher in the NAc shell (221 labeled of 455 identified asymmetric synapses; F(2,14) =4.823, p=0.025 compared to CP) and core (320 labeled of 618 asymmetric synapses; F(2,14) =4.823, p=0.025 compared to CP; Fig. 2D). In contrast, a similar analysis of postsynaptic labeling in spines revealed that only about 4–7% of total spines in the CP and NAc displayed α1AR immunoreactivity (Fig. 2E). Spine labeling was found in both the neck and head of the labeled structures (Figs. 1B,D). Dendritic labeling was very rare but when present, it was observed in medium and large shafts. Immunoperoxidase labeling in large cell bodies of putative CP interneurons was discrete and often associated with membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 5A, 5B). There was no evidence of labeling associated with the plasma membrane of immunoreactive cell bodies. Due to the small sample size that could be observed at the electron microscopic level, the number of labeled and unlabeled cell bodies was not quantified.

Figure 1. Representative examples of α1AR-immunoreactive elements in the rat caudate putamen and the nucleus accumbens.

(A) Example of immunoreactivity seen in large neurons of the caudate putamen (CP). (B) Example of an immunoreactive spine (Sp) and immunoreactive unmyelinated axons (u.Ax) in the rat CP. The labeled spine is contacted by an unlabeled terminal (u.Te) forming an asymmetric synapse. (C) An immunoreactive terminal (Te) forming an asymmetric axo-spinous synapse in the CP. (D) Example of a labeled terminal (Te) that forms a symmetric axo-dendritic synapse, some immunoreactive unmyelinated axons (u.Ax) and a labeled spine (Sp) in the nucleus accumbens (NAc). (E) Example of an immunoreactive terminal (Te) forming multiple asymmetric axo-spinous synapses in the NAc. (F) Immunoreactive unmyelinated axons (u.Ax) in the NAc. Scale bars: 0.5 µm.

Figure 2. Quantification and Distribution of α1AR labeling in caudate putamen and nucleus accumbens.

Histograms showing the density of α1AR-immunoreactive elements in the caudate putamen (CP) (A) and nucleus accumbens (NAc) shell (B) and core (C). ***p<0.001 compared to axons, †p<0.05 compared to terminals. N=5–6 animals per brain region. (D) Shows the percentage of total terminals forming asymmetric synapses that display α1AR immunoreactivity in the CP and NAc. (E) Illustrates the percentage of α1AR-immunoreactive spines in the CP and NAc. *p<0.05 compared to CP. N=94–114 micrographs from 5–6 animals for each brain region.

Figure 5. Representative examples of α1AR cell body labeling in the caudate putamen, ventral tegmental area, and substantia nigra.

(A) Example of a labeled cell body in thecaudate putamen (CP) (magnification: 5000X). (B) Magnified image (20000X) of the area indicated in the square in (A). Note the labeling indicated by the arrows, adjacent to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). (C) Example of a labeled cell body in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) (5000X). (D) Magnified image (25000X) of the area indicated in the square in (C) with labeling close to the ER, also indicated by the arrows. (E) Example of labeled cell bodies in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) (5000X). (F) Magnified image (25000X) of area in the square of (E) with labeling close to the ER as shown by the arrows. Scale bars = 1 µm.

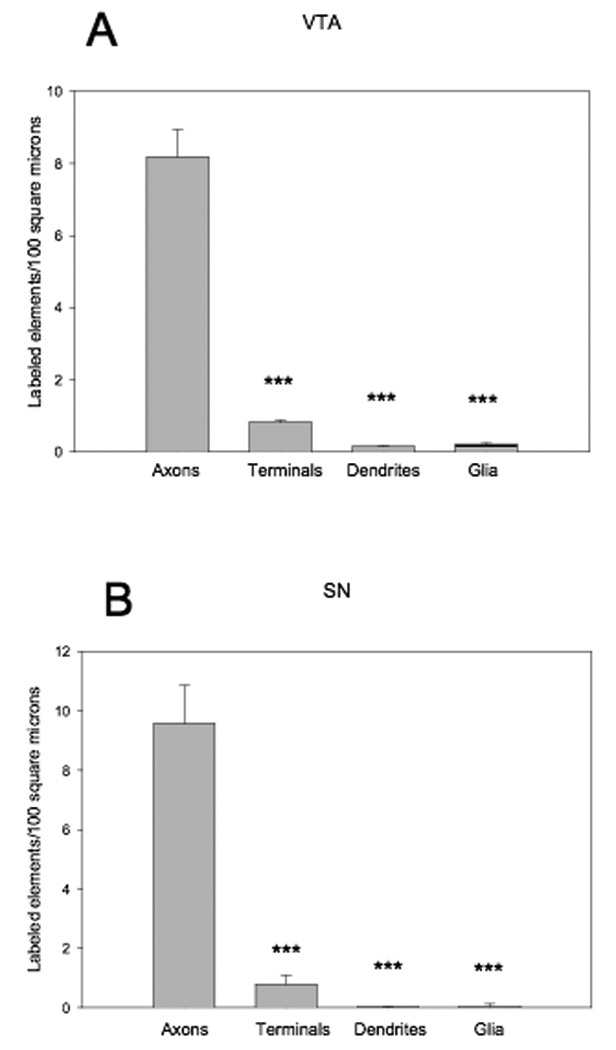

Electron Microscopy: Substantia Nigra and Ventral Tegmental Area

Like the CP and NAc, α1AR immunoreactivity in the SN and VTA was localized predominantly in presynaptic unmyelinated axons and axon terminals (Fig. 3,Fig. 4), and to a much lower extent in postsynaptic dendrites and glia (Fig. 4). In both structures, the labeling in axons was significantly greater than in any other elements identified (F(3,16) =106.286, p<0.001 in VTA; F(3,16) =251.788, p<0.001 in SN; Fig. 4). In contrast, no significant difference was found between the density of labeled terminals, dendrites, and glia (Fig. 4). Of the 714 identified terminals in the VTA and 597 terminals in SN, ~30% (210 labeled in the VTA and 184 labeled in the SN) displayed α1AR immunoreactivity. Although the synaptic specialization associated with many of these boutons could not be clearly seen in single sections, a small proportion of terminals could be categorized as forming symmetric axo-dendritic synapses (110 out of 714 terminals in VTA and 22 out of 597 terminals in SN) or asymmetric synapses (82 out of 714 terminals in VTA and 3 out of 597 terminals in SN). Of these terminals with clear symmetric or asymmetric synaptic specialization in the VTA, 30–50% (52 out of 110 symmetric and 26 out of 82 asymmetric) displayed α1AR immunoreactivity. In the SN, ~ 30% (8 out of 22) of identified terminals forming symmetric synapses displayed α1AR immunoreactivity, while none of the 3 terminals with clear asymmetric synapses contained immunoreactivity. Labeled dendrites were rare in both SN and VTA. The pattern of neuronal cell body labeling in these regions was the same as in the striatum, i.e. relatively discrete, patchy and associated predominantly with the endoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 5 C–F), without any significant relationship with the plasma membrane.

Figure 4. Quantification and distribution of α1AR labeling in ventral tegmental area and substantia nigra.

Histograms showing the density of α1AR-immunoreactive elements in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) (A) and substantia nigra (SN) (B). ***p<0.001 compared to axons, †p<0.05 compared to terminals. N=5–6 animals per brain regions.

Discussion

To provide an anatomical basis for the modulation of DA transmission in the mesostriatal system by α1ARs, we characterized the cellular and ultrastructural localization of the α1AR in the CP, NAc, SN and VTA. At the light microscopic level, the α1AR labeling was mainly associated with punctate neuropil elements in both striatal and midbrain regions. A population of putative interneurons displayed cell body immunoreactivity in the CP and NAc, but medium spiny projection neurons were not significantly labeled. Blocks from SN were taken from the rich neuropil that contained SNr neurons and dendrites of SNc dopaminergic neurons. At the electron microscopic level, α1AR immunoreactivity was mainly located in presynaptic elements (unmyelinated axons and terminals), while sparse labeling was observed in dendrites, spines, neuronal cell bodies and glia. These results suggest that pre-synaptic regulation of excitatory (presumably glutamatergic) and inhibitory (putatively GABAergic) afferents comprises a significant component of the physiological effect of NE on DA transmission in the mesostriatal system.

Direct influence of α1ARs on DA neuron activity

Electrophysiological, pharmacological, and behavioral data indicate that NE signaling via α1ARs increases VTA and SN firing and facilitates DA transmission (Grenhoff and Svensson, 1993, Auclair et al., 2002, Auclair et al., 2004). NE also has direct α1AR-mediated effects on midbrain DA neurons. For instance, activation of α1ARs modulates activity of DA neurons in midbrain slice culture, an effect that was not attenuated by blockade of synaptic transmission with tetrodotoxin (Grenhoff et al., 1995). Another set of slice culture experiments revealed that activation of α1ARs increases amphetamine-induced DA neuron activity by counteracting the inhibitory effect of mGluR1 activation (Paladini et al., 2001). This effect is also likely due to direct action on DA neurons, both because the noradrenergic drugs were applied iontophoretically, instead of being superfused in the bath, and because the effects persisted in the presence of TTX and in the absence of Ca2+(Grenhoff et al., 1995, Paladini et al., 2001). Interestingly, this group subsequently identified an inhibitory effect of α1AR activation on DA neurons, which is in line with the expression of presynaptic α1ARs in putative inhibitory terminals reported in our study.

However, these results are somewhat difficult to reconcile with our findings that α1ARs are only sparsely expressed on dendrites of presumptive DA neurons in the midbrain. Although we did observe occasional cell body staining by light and electron microscopy, the functional role of α1ARs in these perikarya is unclear because at the electron microscopic level, the immunoreactivity was found to be intracellular, associated predominantly with the endoplasmic reticulum, but not with the plasma membrane. One previous study has demonstrated TH-lableled dendrites directly apposed to NE transporter (NET)-positive axons and terminals in the VTA (Liprando et al., 2004), suggesting that some of the dendritic α1ARs identified in our study could be located on DAergic dendrites in close contact with noradrenergic terminals, but this remains to be investigated in more detail. It is possible that the very small population of dendritic α1ARs on midbrain DA neurons can transduce a signal powerful enough to affect neuronal firing properties when maximally stimulated in slice culture, but may not be the primary site mediating the effects of NE on DA neuron activity in vivo. Albeit scarce, α1ARs on striatal dendrites and spines may be functional, as NE can modulate the activity of striatal medium spiny neurons in slices and culture (Nicola and Malenka, 1998, Geldwert et al., 2006).

Indirect influence of α1ARs on DA neuron activity

Although our data do not provide strong anatomical support for a direct effect of postsynaptic α1AR signaling on DA transmission, they rather suggest that the α1AR-mediated facilitation of DA transmission is most likely mediated by presynaptic effects of NE on glutamate and/or GABA signaling. We observed robust α1AR labeling in a significant proportion of putative glutamatergic terminals (i.e. formed asymmetric synapses) in the striatum and VTA, with less in the SN. Because the cerebral cortex is the main source of glutamatergic inputs to both the NAc and CP (Smith et al., 1994, Fremeau et al., 2004, Smith et al., 2004), the majority of α1AR-immunoreactive terminals in the striatum likely originate from corticostriatal axons. However, other sources such as the thalamus, amygdala and hippocampus must also be considered as being potential targets of NE-mediated presynaptic regulation, as well as the recently discovered vGlut2-positive neurons in the VTA (Yamaguchi et al., 2007). Glutamate is also important in the VTA for DA neuron excitability (Tzschentke and Schmidt, 2000, Grillner and Mercuri, 2002). Again, activity of cortical glutamatergic neurons has been implicated in the regulation of midbrain DA neuron firing, but the source of the locally released glutamate is unclear and may involve a relay nucleus (Carr and Sesack, 2000). Based on these results, we propose that NE modulates striatal DA transmission indirectly by stimulating α1ARs on glutamatergic terminals, which facilitates glutamate release and potentiates DA transmission. This interpretation is consistent with the findings that α1AR activation has an excitatory effect on pyramidal neurons in the prefrontal cortex and that local blockade of α1ARs attenuates DA release in the NAc (Sommermeyer et al., 1995, Marek and Aghajanian, 1998). However, double-label EM studies will be required to further characterize the sources and chemical phenotype(s) of the α1AR-containing axons and terminals in the ventral midbrain to confirm our hypothesis. We also observed α1AR expression in a significant proportion of presumptive inhibitory terminals that may be GABAergic (i.e. those which form symmetric synapses) in the midbrain, which could contribute to the reported, but not extensively studied, inhibitory effect of α1ARs on midbrain DA neurons (Paladini and Williams, 2004).

Because of the sparse noradrenergic innervation of the striatum, our finding of significant α1AR immunoreactivity in this structure raises questions about the source of activation and function of α1ARs in this region. On the other hand, the ventral striatum, particularly the caudomedial nucleus accumbens, is densely innervated by noradrenergic fibers probably originating from the LC and nucleus tractus solitarius, and the tissue levels of NE approach those of DA in this brain region in both humans and rodents (Delfs et al., 1998, Tong et al., 2006b,a). Although tissue levels of NE in the dorsal striatum are very low compared to dopamine (~ 50–100 fold difference), basal extracellular NE levels are higher than expected (~ 20-fold lower than dopamine), suggesting that the noradrenergic terminals in the striatum are quite active (Gobert et al., 2004, Fulceri et al., 2007, Weinshenker and Schroeder, 2007). Most, if not all of the NE in the striatum comes from the LC, since 6-OHDA lesions of the LC severely reduce striatal NE levels (Fulceri et al., 2007).

Axonal localization of α1ARs

Consistent with previous electron localization studies of other G protein-coupled receptors, including DA receptors, metabotropic glutamate receptors, and GABAB receptors, the majority of pre-synaptic labeling for α1ARs was found in unmyelinated axons in both the striatum and ventral midbrain (Villalba et al., 2006, Dumartin et al., 2007, Mitrano and Smith, 2007). Although the functional significance of such axonal labeling remains unclear for most transmitter systems, it strongly suggests that the stimulation of such receptors relies on extrasynaptic spillover or volume transmission of the activating neurotransmitter. This mechanism of neural communication is consistent with the current view that NE is released by volume transmission and may stimulate non-synaptic receptors located far away from the transmitter release sites (Fuxe, 1991). Based on recent immunogold studies of other GPCRs showing that axonal immunoreactivity for D1, metabotropic glutamate receptor and GABAB receptor labeling is largely bound to the axonal plasma membrane (Villalba et al., 2006, Dumartin et al., 2007, Mitrano and Smith, 2007), it is reasonable to suggest that the α1ARs axonal immunoreactivity described in our study represents functional pre-synaptic NE receptors that could be activated by extracellular NE to regulate glutamate and GABA release in the striatum and ventral midbrain.

Localization of α1ARs in glia

Although NE is traditionally considered a neuron-to-neuron messenger in the central nervous system, NE has also been shown to promote communication between neurons and glia (Duffy and MacVicar, 1995). The localization, although sparse, of α1AR receptors in astrocytic processes is of interest given the recent evidence that glial cells actively participate in mediating responses to drugs of abuse (Narita et al., 2006). Intracellular Ca2+ release in glia can be initiated by glutamate and NE (Duffy and MacVicar, 1995), and α1ARs can regulate intracellular Ca2+ in cultures of striatal astrocytes (Delumeau et al., 1991a, Delumeau et al., 1991b, Giaume et al., 1991).

Implications for diseases of dopaminergic dysfunction

NE has been implicated in a number of diseases of dopaminergic dysfunction, such as Parkinson’s disease (PD), drug addiction, and attention-deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). For example, severe LC degeneration and NE loss is observed clinically in PD and experimental models of PD have shown that LC or NE loss exacerbates PD-like motor abnormalities (Mavridis et al., 1991, Marien et al., 2004, Rommelfanger et al., 2004, Rommelfanger et al., 2007). The regulation of SN activity by α1ARs could account for these findings (Grenhoff and Svensson, 1993, Grenhoff et al., 1995). In addition, α1ARs in the nigrostriatal DA system may be critical for the effects of L-DOPA treatment. For example, the α1AR antagonist prazosin attenuates some beneficial effects of L-DOPA in MPTP-treated Parkinsonian monkeys (Visanji et al., 2006, Fox, 2007). The subthalamic nucleus (STN), which has been a target for therapeutic lesioning and deep brain stimulation in PD (Krack et al., 1998, Limousin et al., 1998), may also be of interest for NE-mediated PD pharmacotherapy. α1AR immunoreactivity has been detected postsynaptically in STN cell bodies, and α1AR activation modulates the firing properties of STN neurons (Arcos et al., 2003, Belujon et al., 2007). A brief survey of STN tissue from rats used in the present study did reveal immunoperoxidase staining in this region (data not shown), but a more detailed examination of the subcellular localization of α1ARs in STN neurons will be required to clarify the substrate by which NE can mediate its functional effects in these cells.

α1ARs have also been implicated in the neural mechanisms that underlie behavioral and neurochemical changes in response to drugs of abuse in rodents (Drouin et al., 2002, Villegier et al., 2003, Auclair et al., 2004). Genetic or pharmacological blockade of α1ARs attenuates the effects of psychostimulants and opiates on DA release in the NAc, locomotor activity, sensitization, reward, the escalation of cocaine seeking produced by extended access to drug or prior cocaine exposure, and cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug seeking following extinction (Zhang and Kosten, 2005, Olson et al., 2006, Weinshenker and Schroeder, 2007, Zhang and Kosten, 2007, Wee et al., 2008). While the importance of prefrontocortical α1ARs for some of these phenomena has been established (Darracq et al., 1998), the prominent presynaptic expression of these receptors in the NAc and VTA suggests that local α1ARs also contribute to drug-induced changes in DA neurochemistry and behavior.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jeff Pare and Susan Jenkins for technical assistance. KSR was supported by the NINDS Training Grant at Emory University (T32 DA 15040–01A1). This work was partly supported by NIH/NIDA (DA017963) and the NIH base grant of The Yerkes National Primate Research Centre (RR000165).

Abbreviations

- CP

caudate putamen

- NAc

nucleus accumbens

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

- SN

substantia nigra

- LC

locus coeruleus

- STN

subthalamic nucleus

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

- alpha1AR

alpha1 adrenergic receptor

- ABC

avidin-biotin-complex

- DA

dopamine

- NE

norepinephrine

- mGluR

metabotropic glutamate receptor

- GABAR

gamma-amino-butyric acid receptor

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- ADHD

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

References

- Arcos D, Sierra A, Nunez A, Flores G, Aceves J, Arias-Montano JA. Noradrenaline increases the firing rate of a subpopulation of rat subthalamic neurones through the activation of alpha 1-adrenoceptors. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45:1070–1079. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00315-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auclair A, Cotecchia S, Glowinski J, Tassin JP. D-amphetamine fails to increase extracellular dopamine levels in mice lacking alpha 1b-adrenergic receptors: relationship between functional and nonfunctional dopamine release. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9150–9154. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09150.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auclair A, Drouin C, Cotecchia S, Glowinski J, Tassin JP. 5-HT2A and alpha1b-adrenergic receptors entirely mediate dopamine release, locomotor response and behavioural sensitization to opiates and psychostimulants. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:3073–3084. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belujon P, Bezard E, Taupignon A, Bioulac B, Benazzouz A. Noradrenergic modulation of subthalamic nucleus activity: behavioral and electrophysiological evidence in intact and 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9595–9606. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2583-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc G, Trovero F, Vezina P, Herve D, Godeheu AM, Glowinski J, Tassin JP. Blockadeof prefronto-cortical alpha 1-adrenergic receptors prevents locomotor hyperactivity induced by subcortical D-amphetamine injection. Eur J Neurosci. 1994;6:293–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr DB, Sesack SR. Projections from the rat prefrontal cortex to the ventral tegmentalarea: target specificity in the synaptic associations with mesoaccumbens and mesocortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3864–3873. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03864.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darracq L, Blanc G, Glowinski J, Tassin JP. Importance of the noradrenaline-dopamine coupling in the locomotor activating effects of D-amphetamine. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2729–2739. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-07-02729.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day HE, Campeau S, Watson SJ, Jr, Akil H. Distribution of alpha 1a-, alpha 1b-and alpha 1d-adrenergic receptor mRNA in the rat brain and spinal cord. J Chem Neuroanat. 1997;13:115–139. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(97)00042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfs JM, Zhu Y, Druhan JP, Aston-Jones GS. Origin of noradrenergic afferents to the shell subregion of the nucleus accumbens: anterograde and retrograde tract-tracing studies in the rat. Brain Res. 1998;806:127–140. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00672-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delumeau JC, Marin P, Cordier J, Glowinski J, Premont J. Synergistic effects in the alpha 1-and beta 1-adrenergic regulations of intracellular calcium levels in striatal astrocytes. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1991a;11:263–276. doi: 10.1007/BF00769039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delumeau JC, Tence M, Marin P, Cordier J, Glowinski J, Premont J. Synergistic Regulation of Cytosolic Ca2+ Concentration by Adenosine and alpha1-Adrenergic Agonists in Mouse Striatal Astrocytes. Eur J Neurosci. 1991b;3:539–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1991.tb00841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domyancic AV, Morilak DA. Distribution of alpha1A adrenergic receptor mRNA in the rat brain visualized by in situ hybridization. J Comp Neurol. 1997;386:358–378. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970929)386:3<358::aid-cne3>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouin C, Darracq L, Trovero F, Blanc G, Glowinski J, Cotecchia S, Tassin JP. Alpha1b-adrenergic receptors control locomotor and rewarding effects of psychostimulants and opiates. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2873–2884. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02873.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy S, MacVicar BA. Adrenergic calcium signaling in astrocyte networks within the hippocampal slice. J Neurosci. 1995;15:5535–5550. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-08-05535.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumartin B, Doudnikoff E, Gonon F, Bloch B. Differences in ultrastructural localization of dopaminergic D1 receptors between dorsal striatum and nucleus accumbens in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 2007;419:273–277. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox SHV NP, Johnston TH, Millan MJ, Brotchie JM. The alpha-1 adrenoreceptor antagonist, prazosin, attenuates l-dopa-induced hyperactivity without affecting antiparkinsonian actions of l-dopa in MPTP-treated macaques. Society For Neuroscience Annual Meeting Abstract, vol. #693.5; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fremeau RT, Jr, Kam K, Qureshi T, Johnson J, Copenhagen DR, Storm-Mathisen J, Chaudhry FA, Nicoll RA, Edwards RH. Vesicular glutamate transporters 1 and 2 target to functionally distinct synaptic release sites. Science. 2004;304:1815–1819. doi: 10.1126/science.1097468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulceri F, Biagioni F, Ferrucci M, Lazzeri G, Bartalucci A, Galli V, Ruggieri S, Paparelli A, Fornai F. Abnormal involuntary movements (AIMs) following pulsatile dopaminergic stimulation: severe deterioration and morphological correlates following the loss of locus coeruleus neurons. Brain Res. 2007;1135:219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuxe KaA L. Volume versus wiring transmission. New York: Raven Press; 1991. Two principal modes of electrochemical communication in thebrain. [Google Scholar]

- Geldwert D, Norris JM, Feldman IG, Schulman JJ, Joyce MP, Rayport S. Dopamine presynaptically and heterogeneously modulates nucleus accumbens medium-spiny neuron GABA synapses in vitro. BMC Neurosci. 2006;7:53. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaume C, Marin P, Cordier J, Glowinski J, Premont J. Adrenergic regulation of intercellular communications between cultured striatal astrocytes from the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:5577–5581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilsbach R, Hein L. Presynaptic metabotropic receptors for acetylcholine and adrenaline/noradrenaline. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008:261–288. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-74805-2_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glowinski J, Iversen LL. Regional studies of catecholamines in the rat brain. I. The disposition of [3H]norepinephrine, [3H]dopamine and [3H]dopa in various regions of the brain. J Neurochem. 1966;13:655–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1966.tb09873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobert A, Billiras R, Cistarelli L, Millan MJ. Quantification and pharmacological characterization of dialysate levels of noradrenaline in the striatum of freely-moving rats: release from adrenergic terminals and modulation by alpha2-autoreceptors. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;140:141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene JG, Dingledine R, Greenamyre JT. Gene expression profiling of rat midbrain dopamine neurons: implications for selective vulnerability in parkinsonism. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;18:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenhoff J, Nisell M, Ferre S, Aston-Jones G, Svensson TH. Noradrenergic modulation of midbrain dopamine cell firing elicited by stimulation of the locus coeruleus in the rat. J Neural Transm Gen Sect. 1993;93:11–25. doi: 10.1007/BF01244934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenhoff J, North RA, Johnson SW. Alpha 1-adrenergic effects on dopamine neurons recorded intracellularly in the rat midbrain slice. Eur J Neurosci. 1995;7:1707–1713. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb00692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenhoff J, Svensson TH. Prazosin modulates the firing pattern of dopamine neurons in rat ventral tegmental area. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;233:79–84. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90351-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillner P, Mercuri NB. Intrinsic membrane properties and synaptic inputs regulating thefiring activity of the dopamine neurons. Behav Brain Res. 2002;130:149–169. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00418-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CR, Hamilton CA, Whyte KF, Elliott HL, Reid JL. Acute and chronic regulation of alpha 2-adrenoceptor number and function in man. Clin Sci (Lond) 1985;68 Suppl 10:129s–132s. doi: 10.1042/cs068s129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krack P, Benazzouz A, Pollak P, Limousin P, Piallat B, Hoffmann D, Xie J, Benabid AL. Treatment of tremor in Parkinson's disease by subthalamic nucleus stimulation. Mov Disord. 1998;13:907–914. doi: 10.1002/mds.870130608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lategan AJ, Marien MR, Colpaert FC. Effects of locus coeruleus lesions on the release ofendogenous dopamine in the rat nucleus accumbens and caudate nucleus asdetermined by intracerebral microdialysis. Brain Res. 1990;523:134–138. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91646-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limousin P, Krack P, Pollak P, Benazzouz A, Ardouin C, Hoffmann D, Benabid AL. Electrical stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in advanced Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1105–1111. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810153391603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindvall O, Bjorklund A. The organization of the ascending catecholamine neuron systems in the rat brain as revealed by the glyoxylic acid fluorescence method. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl. 1974;412:1–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liprando LA, Miner LH, Blakely RD, Lewis DA, Sesack SR. Ultrastructural interactionsbetween terminals expressing the norepinephrine transporter and dopamineneurons in the rat and monkey ventral tegmental area. Synapse. 2004;52:233–244. doi: 10.1002/syn.20023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek GJ, Aghajanian GK. The electrophysiology of prefrontal serotonin systems: therapeutic implications for mood and psychosis. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:1118–1127. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marien MR, Colpaert FC, Rosenquist AC. Noradrenergic mechanisms in neurodegenerative diseases: a theory. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2004;45:38–78. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavridis M, Degryse AD, Lategan AJ, Marien MR, Colpaert FC. Effects of locus coeruleus lesions on parkinsonian signs, striatal dopamine and substantia nigracell loss after 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine in monkeys: apossible role for the locus coeruleus in the progression of Parkinson's disease. Neuroscience. 1991;41:507–523. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90345-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrano DA, Smith Y. Comparative analysis of the subcellular and subsynaptic localization of mGluR1a and mGluR5 metabotropic glutamate receptors in the shell and core of the nucleus accumbens in rat and monkey. J Comp Neurol. 2007;500:788–806. doi: 10.1002/cne.21214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow AL, Creese I. Characterization of alpha 1-adrenergic receptor subtypes in ratbrain: a reevaluation of [3H]WB4104 and [3H]prazosin binding. Mol Pharmacol. 1986;29:321–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakadate K, Imamura K, Watanabe Y. Cellular and subcellular localization of alpha-1 adrenoceptors in the rat visual cortex. Neuroscience. 2006;141:1783–1792. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita M, Miyatake M, Suzuki M, Kuzumaki N, Suzuki T. Role of astrocytes in rewarding effects of drugs of abuse. Nihon Shinkei Seishin Yakurigaku Zasshi. 2006;26:33–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicola SM, Malenka RC. Modulation of synaptic transmission by dopamine and norepinephrine in ventral but not dorsal striatum. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:1768–1776. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.4.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson VG, Heusner CL, Bland RJ, During MJ, Weinshenker D, Palmiter RD. Role of noradrenergic signaling by the nucleus tractus solitarius in mediating opiate reward. Science. 2006;311:1017–1020. doi: 10.1126/science.1119311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacios JM, Hoyer D, Cortes R. alpha 1-Adrenoceptors in the mammalian brain: similar pharmacology but different distribution in rodents and primates. Brain Res. 1987;419:65–75. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90569-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paladini CA, Fiorillo CD, Morikawa H, Williams JT. Amphetamine selectively blocks inhibitory glutamate transmission in dopamine neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:275–281. doi: 10.1038/85124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paladini CA, Williams JT. Noradrenergic inhibition of midbrain dopamine neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4568–4575. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5735-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan WH, Sung JC, Fuh SM. Locally application of amphetamine into the ventral tegmental area enhances dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens and the medial prefrontal cortex through noradrenergic neurotransmission. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;278:725–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters W, Taraschewski H, Latka I. Comparative investigations of the morphology and chemical composition of the eggshells of Acanthocephala. I. Macracanthorhynchus hirudinaceus (Archiacanthocephala) Parasitol Res. 1991;77:542–549. doi: 10.1007/BF00928424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieribone VA, Nicholas AP, Dagerlind A, Hokfelt T. Distribution of alpha 1 adrenoceptors in rat brain revealed by in situ hybridization experiments utilizing subtype-specific probes. J Neurosci. 1994;14:4252–4268. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-07-04252.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainbow TC, Biegon A. Quantitative autoradiography of [3H]prazosin binding sites in rat forebrain. Neurosci Lett. 1983;40:221–226. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(83)90042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rommelfanger KS, Edwards GL, Freeman KG, Liles LC, Miller GW, Weinshenker D. Norepinephrine loss produces more profound motor deficits than MPTP treatment in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13804–13809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702753104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rommelfanger KS, Weinshenker D, Miller GW. Reduced MPTP toxicity in noradrenaline transporter knockout mice. J Neurochem. 2004;91:1116–1124. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell VA, Lamm MC, Allin R, de Villiers AS, Searson A, Taljaard JJ. Effect of selective noradrenergic denervation on noradrenaline content and [3H]dopamine release in rat nucleus accumbens slices. Neurochem Res. 1989;14:169–172. doi: 10.1007/BF00969634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schank JR, Ventura R, Puglisi-Allegra S, Alcaro A, Cole CD, Liles LC, Seeman P, Weinshenker D. Dopamine beta-hydroxylase knockout mice have alterations in dopamine signaling and are hypersensitive to cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2221–2230. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwinn DA, Johnston GI, Page SO, Mosley MJ, Wilson KH, Worman NP, Campbell S, Fidock MD, Furness LM, Parry-Smith DJ, et al. Cloning and pharmacological characterization of human alpha-1 adrenergic receptors: sequence corrections and direct comparison with other species homologues. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;272:134–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Y, Bennett BD, Bolam JP, Parent A, Sadikot AF. Synaptic relationships between dopaminergic afferents and cortical or thalamic input in the sensorimotor territoryof the striatum in monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1994;344:1–19. doi: 10.1002/cne.903440102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Y, Raju DV, Pare JF, Sidibe M. The thalamostriatal system: a highly specific network of the basal ganglia circuitry. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:520–527. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommermeyer H, Frielingsdorf J, Knorr A. Effects of prazosin on the dopaminergic neurotransmission in rat brain. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;276:267–270. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00062-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AF, Rokosh DG, Bailey BA, Karns LR, Chang KC, Long CS, Kariya K, Simpson PC. Cloning of the rat alpha 1C-adrenergic receptor from cardiac myocytes. alpha 1C, alpha 1B, and alpha 1D mRNAs are present in cardiac myocytes but not in cardiac fibroblasts. Circ Res. 1994;75:796–802. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.4.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone EA, Lin Y, Ahsan R, Quartermain D. Role of locus coeruleus alpha1-adrenoceptors in motor activity in rats. Synapse. 2004;54:164–172. doi: 10.1002/syn.20074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strausberg RL, Feingold EA, Grouse LH, Derge JG, Klausner RD, Collins FS, Wagner L, Shenmen CM, Schuler GD, Altschul SF, Zeeberg B, Buetow KH, Schaefer CF, Bhat NK, Hopkins RF, Jordan H, Moore T, Max SI, Wang J, Hsieh F, Diatchenko L, Marusina K, Farmer AA, Rubin GM, Hong L, Stapleton M, Soares MB, Bonaldo MF, Casavant TL, Scheetz TE, Brownstein MJ, Usdin TB, Toshiyuki S, Carninci P, Prange C, Raha SS, Loquellano NA, Peters GJ, Abramson RD, Mullahy SJ, Bosak SA, McEwan PJ, McKernan KJ, Malek JA, Gunaratne PH, Richards S, Worley KC, Hale S, Garcia AM, Gay LJ, Hulyk SW, Villalon DK, Muzny DM, Sodergren EJ, Lu X, Gibbs RA, Fahey J, Helton E, Ketteman M, Madan A, Rodrigues S, Sanchez A, Whiting M, Madan A, Young AC, Shevchenko Y, Bouffard GG, Blakesley RW, Touchman JW, Green ED, Dickson MC, Rodriguez AC, Grimwood J, Schmutz J, Myers RM, Butterfield YS, Krzywinski MI, Skalska U, Smailus DE, Schnerch A, Schein JE, Jones SJ, Marra MA. Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full-length human and mouse cDNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16899–16903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242603899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson L, Ahlenius S. Functional importance of nucleus accumbens noradrenaline in the rat. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh) 1982;50:22–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1982.tb00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong J, Hornykiewicz O, Kish SJ. Identification of a noradrenaline-rich subdivision of the human nucleus accumbens. J Neurochem. 2006a;96:349–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong J, Hornykiewicz O, Kish SJ. Inverse relationship between brain noradrenaline level and dopamine loss in Parkinson disease: a possible neuroprotective role for noradrenaline. Arch Neurol. 2006b;63:1724–1728. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.12.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzschentke TM, Schmidt WJ. Functional relationship among medial prefrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, and ventral tegmental area in locomotion and reward. CritRev Neurobiol. 2000;14:131–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villalba RM, Raju DV, Hall RA, Smith Y. GABA(B) receptors in the centromedian/parafascicular thalamic nuclear complex: an ultrastructural analysis of GABA(B)R1 and GABA(B)R2 in the monkey thalamus. J Comp Neurol. 2006;496:269–287. doi: 10.1002/cne.20950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villegier AS, Drouin C, Bizot JC, Marien M, Glowinski J, Colpaert F, Tassin JP. Stimulation of postsynaptic alpha1b-and alpha2-adrenergic receptors amplifies dopamine-mediated locomotor activity in both rats and mice. Synapse. 2003;50:277–284. doi: 10.1002/syn.10267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visanji NP, Johnston TH, Fox SH, Millan MJ, Brotchie JM. The alpha1-adrenoceptor antagonist prazosin attenuates the antiparkinsonian actions of L-DOPA in MPTP-treated macaques. 2006 Neuroscience Meeting Planner; Atlanta, GA: Society for Neuroscience; 2006. Online. [Google Scholar]

- Wee S, Mandyam CD, Lekic DM, Koob GF. Alpha 1-noradrenergic system role in increased motivation for cocaine intake in rats with prolonged access. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;18:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinshenker D, Miller NS, Blizinsky K, Laughlin ML, Palmiter RD. Mice with chronic norepinephrine deficiency resemble amphetamine-sensitized animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13873–13877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212519999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinshenker D, Schroeder JP. There and back again: a tale of norepinephrine and drug addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1433–1451. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi T, Sheen W, Morales M. Glutamatergic neurons are present in the rat ventraltegmental area. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:106–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young WS, 3rd, Kuhar MJ. Noradrenergic alpha 1 and alpha 2 receptors: light microscopic autoradiographic localization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:1696–1700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.3.1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XY, Kosten TA. Prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist, reduces cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1202–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XY, Kosten TA. Previous exposure to cocaine enhances cocaine self-administration in an alpha 1-adrenergic receptor dependent manner. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:638–645. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]