Abstract

Stress has been cited as an important precipitator of smoking relapse. Dysregulation of neurobiological pathways related to stress might mediate effect of stress on smoking relapse. This study assessed the extent to which beta endorphin response to stress is associated with early smoking relapse. Forty-five smokers interested in smoking cessation were recruited and attended a laboratory session 24 h following the beginning of their abstinence period. During this session beta endorphin samples were collected before and after performing two acute stressors (public speaking and cognitive tasks). Participants also attended four weekly follow up sessions to assess their smoking status. Results were compared between smokers who relapsed within the 4-week follow-up period and those who maintained abstinence over the same period. The acute stressors were associated with significant increases in measures of craving and withdrawal symptoms (ps < 0.01). While baseline measures of beta endorphin did not differ between relapsers and successful abstainers (F < 1), results demonstrated that smokers who relapsed exhibited attenuated beta endorphin response to the two stressors relative to those who maintained abstinence over the same period (ps < 05). These results support recent evidence indicating that a dysregulated stress response is a key component in predicting smoking relapse.

Keywords: Stress, beta endorphin, smoking, relapse, endogenous opioid

Introduction

This study examined the extent to which beta endorphin response to acute psychological stress predicted smoking relapse. Stress has been shown to lead to higher rates of smoking relapse (Kassel et al., 2003; Brown et al., 2005). Previous evaluations of the stress response during acute nicotine withdrawal have focused on the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and cardiovascular responses (al’Absi et al., 2005; Swan et al., 1996). Other neuroendocrine systems including the endogenous opioid system are known to be activated by nicotine, and nicotine withdrawal may change their activity (Biala et al., 2005; Pomerleau, 1998).

Smoking relapse rates are very high during the first few week of abstinence, with approximately 50% of smokers relapsing within the first 3 days and 75% relapsing within 2 weeks (Garvey et al., 1992; Duncan et al., 1992; Arnsten et al., 2004). Smoking abstinence is associated with increased discomfort and stress (Hatsukami et al., 1988;Hughes, 1992; Pritchard et al., 1992; Stitzer and Gross, 1988), and these symptoms may exacerbate effects of stress (Perkins et al., 1992; al’Absi et al., 2002). Stress has been considered a significant risk factor for smoking relapse (Cohen and Lichtenstein, 1990). Identifying neurobiological factors that are involved in the interactions of stress and relapse may point towards future targets for pharmaceutical manipulations (Weiss, 2005; Self and Nestler, 1998; Koob and Le Moal, 1997).

Endogenous opioids play a role in addiction and reward of multiple drugs, including alcohol and tobacco (Gianoulakis, 2004; Pomerleau, 1998; Heinz et al., 1995). Beta endorphin is an opioid that is synthesized from proopiomelanocortin (POMC), with influence on reward, mood, and pain regulation through action on Delta- and Mu- opioid receptors (Herz, 1997). The mesolimbic dopamine system plays a well-established role in mediating the rewarding properties of addiction (Herz, 1997; Pecina and Berridge, 2005), and there is evidence that it interacts considerably with the endogenous opioid system (Dilts and Kalivas, 1989; Gonzales and Weiss, 1998). This is evidenced by a suppressed dopamine response with opioid blockade by naltrexone (Gonzales and Weiss, 1998; Gianoulakis, 2001), as well as a rich supply of opioid receptors in reward centers of the brain, such as the ventral tegmental area and the nucleus accumbens (Dilts and Kalivas, 1989; Gianoulakis, 2001). Drugs with abuse potential, such as opioids and alcohol, increase synthesis of beta endorphin (Laviolette et al., 2002; Oswald and Wand, 2004). In contrast, chronic exposure to drugs, such as alcohol and nicotine, causes a relative beta endorphin deficiency (Scanlon et al., 1992), and this deficiency persists for several weeks following withdrawal (Rasmussen, 1998; Rasmussen et al., 2000).

Beta endorphin is a unique component of the reward pathway and is possibly involved in reinforcing smoking behavior (Pomerleau, 1998; Rasmussen, 1998; Lutfy et al., 2006). Nicotine has been shown to require Mu-opioid receptors to have addictive potential (Berrendero et al., 2002; Walters et al., 2005). Cellular studies show that hypothalamic neurons release beta endorphin in response to acute nicotine treatment, have desensitized beta endorphin response with chronic nicotine exposure, and demonstrate withdrawal response after cessation of nicotine intake (Boyadjieva and Sarkar, 1997). Opioid blockade with naloxone also led to withdrawal symptoms and attenuated cortisol response in smokers compared to nonsmokers (Krishnan-Sarin et al., 1999). The dose-dependent rise in plasma beta endorphin response to nicotine suggests that the rate of nicotine infusion is critical to nicotine reinforcement value (Pomerleau, 1992), however animal studies show that chronic nicotine intake produces an opioid deficient state which may contribute to maintenance of nicotine dependence (Rasmussen, 1998).

It is possible that beta endorphin mediates effects of stress on nicotine addiction, although the nature of this interaction is not yet well understood. Animals exposed to chronic stress have enhanced beta endorphin release in response to nicotine intake compared to unstressed animals (Lutfy et al., 2006). Importantly, plasma levels of beta endorphin rise with acute stress (Owens and Smith, 1987; Smith et al., 1986). This study was performed to explore the extent to which beta endorphin responses to stress after one day of nicotine abstinence predict smoking relapse. Based on previous research reviewed above and our work showing that attenuated ACTH response to stress predicted early relapse, we hypothesize that plasma beta endorphin hyporesponsiveness to stress predicts increased risk for smoking relapse.

Methods

Participants

Participants were smokers who were interested in smoking cessation and were otherwise free from any medical or psychiatric problems. This paper includes a sample of forty-five participants drawn from a larger study (al’Absi et al., 2005), and the sample was composed of all those who had blood samples that were assayed for beta endorphin. Participants were recruited from the community using newspaper advertisements for a quit-smoking study and by posters placed in the university community. Interested participants completed a preliminary telephone screening interview. This interview included questions concerning current or recent history of medical or psychiatric disorders, medication intake, and whether potential participants met smoking criteria (having smoked an average of 10 cigarettes or more per day for a minimum of two years). Those who met the initial phone screening criteria were invited to an on-site screening session. Based on information collected during the screening session, participants were included if they had no history of a major illness or psychiatric disorder, weighed within ± 30% of Metropolitan Life Insurance norms, consumed two or less alcoholic drinks a day, and did not routinely use prescription medications (except contraceptives). Participants signed a consent form approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Minnesota and were monetarily compensated for their participation at a rate of approximately 20$/hour. Although the initial 24-hour abstinence was required prior to the lab session for continuation in the study, the compensation was not contingent upon maintained abstinence after that session.

Procedures

Participants interested in quitting and who passed phone screening were scheduled for on-site screening and orientation. Upon arrival at the laboratory, the participant read and signed a consent form. The participant then provided a breath sample for the assessment of expired carbon monoxide (CO), completed forms related to medical history, smoking history, previous attempts to quit, rating of current motivation to quit, demographics, and other psychosocial variables described below. Weight and height were then measured, and this was followed by a brief interview conducted to explain the study, confirm eligibility, and address any questions or concerns the participant might have had. Female participants were asked about regularity of their menstrual cycle and use of contraceptive medications. Quit date for menstruating women was scheduled during the follicular phase (day 3 to day 10) of the menstrual cycle based on self-report of regularity and time of the previous menstrual cycle.

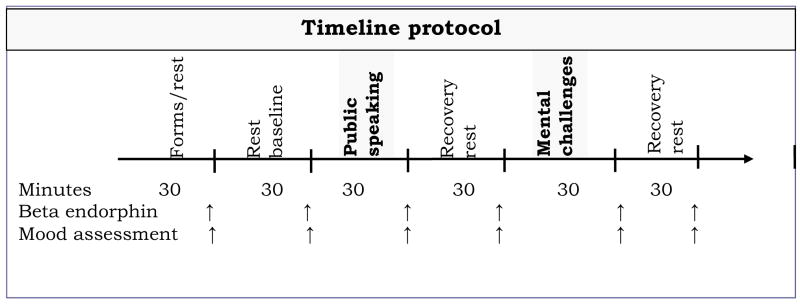

The laboratory session was conducted after 24 hours after the onset of abstinence from smoking. This 24-hour period of abstinence was required of all participants. Participants reported to the laboratory between 12:30 and 1:30 pm. Prior to the session, participants were instructed to have a light lunch at least two hours prior to the session. Upon arriving at the laboratory, a breath sample was obtained for assessment of CO, and participants were instrumented for cardiovascular measurements with BP cuff and surface electrodes. Intravenous catheter insertion was completed. Participants then sat awake, while watching emotionally neutral nature films and/or documentaries. The protocol included a 30-minute baseline rest period, followed by the public-speaking challenges (30 min), and a 30-minute recovery period. Then participants performed the mental arithmetic and the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task (PASAT) tasks (30 min), which were followed by a final recovery period for 30 minutes. Blood samples for hormonal assessment and ratings of mood and withdrawal symptoms were collected before, during, and after working on two stressors (described below). Interval between samples was approximately 30 minutes (see Figure 1). Each sample was collected in an 8 ml EDTA Vacutainer tube. At the end of the session, samples were centrifuged and stored at −70°C.

Figure 1.

Timeline protocol during the laboratory sessions (time in minutes)

The order of the two stressors (public speaking and cognitive math challenge) was fixed with the public-speaking task presented first. The public-speaking stressor involved three scenarios in which participants were asked to construct and deliver a four-minute speech after four minutes of silent preparation. They were instructed that their speeches would be videotaped and then evaluated by two staff members from the experimental team. The three scenarios were presented in a counterbalanced order. In one scenario, participants were presented with a controversial social issue and were asked to introduce their positions and defend them. In another scenario, participants were given an article about an issue of general interest and were asked to construct a presentation based on this article. In a third scenario, participants were asked to imagine a hypothetical situation where they were being accused of shoplifting. Participants were asked to construct arguments for a speech to defend themselves. Before each scenario, participants were asked to make their statements specific and precise, since the evaluation of performance was going to be based on how convincing, organized, articulate, and enthusiastic they were during each presentation. This task has been shown to be a potent laboratory stressor, inducing significant cardiovascular, endocrine, and mood changes (al’Absi et al. 1997).

The cognitive challenge included two tasks, the mental arithmetic task and the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task (PASAT) presented in a counterbalanced order. The mental arithmetic task required continuously adding the digits of a three-digit number and adding the sum to the original number (al’Absi et al. 1997). When a mistake was made, the participant was asked to go back to the previous correct number. Participants performed the PASAT for eight minutes (Gronwall 1977). The participant must sum each number with the digit presented immediately before it. Four trials of the PASAT were used with different lengths of the interstimulus interval (Sherman et al. 1997). The version used in this experiment included 200 items and the interstimulus intervals of the four trials were 2.4, 2.0, 1.6, and 1.2 seconds. We also conducted four weekly follow-up sessions. At the beginning of each of these sessions participants provided a breath sample for carbon monoxide assessment and a saliva sample for cotinine assay, and they also completed a form about their smoking behavior. Furthermore, participants attended brief support sessions to encourage reduction in smoking rate or to help prevent relapse. Due to occasional scheduling difficulties, intervals between sessions ranged between 7 and 12 days.

Measures and instruments

Beta endorphin was assayed using radioimmunoassay kits (Nicols Institute, Bad Nauheim Germany) with a lower sensitivity of 1 pg/mL. Cotinine concentrations in saliva were measured by enzyme immunoassay (EIA) (DRG Diagnostics, Marburg, Germany). Inter- and intra-assay variations were below 12%. Measurement of expired CO was performed using MicroCO™ monitors (Micro Direct Inc., Auburn, Maine). Participants also completed the Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale (MNWS) to measure withdrawal symptoms and the Questionnaire of Smoking Urges (QSU-brief; Cox et al., 2001) to measure craving. Participants also completed positive affect and distress, two factors previously shown to be reliable in tracking laboratory states-related changes in mood (al’Absi et al. 1994; al’Absi et al. 1998). Positive affect was assessed using items of cheerfulness, content, calmness, controllability, and interest. Distress was assessed using items of anxiety, irritability, impatience, and restlessness. The two factors were previously shown to be sensitive to acute stress and to have sound psychometric properties, including Cronbach’s alpha for positive affect and distress of 0.85 and 0.82, respectively (al’Absi et al., 2003).

In addition, during the screening session participants completed the Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence (FTND; Heatherton et al. 1991), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale (Radloff 1977), the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (Trait Form; STAI) (Spielberger et al. 1983), and the 10-item version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (Cohen et al. 1983).

Data analysis

Analyses were conducted to examine differences in demographics, smoking, psychological measures, and baseline cardiovascular and hormonal measures between those who relapsed within the 4-week period and those who maintained abstinence using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Relapse was defined as self-report smoking of at least one cigarette during the four weeks after their quit date. Hormonal and subjective measures were analyzed using a 2 (Groups: relapsers and successful abstainers) × 6 (Times) mixed multivariate repeated measure analysis of variance (MANOVA). Beta endorphin samples were collected from 45 participants, and 34 of them relapsed within the four-week follow-up period. Effects of the initial abstinence period on salivary cotinine concentrations and carbon monoxide were analyzed using a 2 (Groups) × 2 (Assessments prior to and after quitting) mixed ANOVA. Due to technical difficulties in obtaining all blood samples only 29 participants had complete beta endorphin data for the entire session (9 remained abstinent for the entire follow-up period while 20 relapsed). Due to these missing data, variations existed between sample size and degrees of freedom for the reported variables. Analyses were conducted using the SYSTAT software package (SYSTAT, Inc., Evanston, IL).

Results

Relapsers and those who maintained abstinence over the 4 week period did not differ in age, cigarettes smoked per day, or years of education (ps > 0.1; see Table 1). Similarly there were no differences between relapsers and abstainers in levels of nicotine dependence, trait anxiety, depression, or perceived stress as measured by FTND, the Trait Form of STAI, the CES-D scale, and the PSS, respectively (Fs < 1.7; ps > .20).

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics

| Variables | Abstainers | Relapsers | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 42.9 (4.2) | 36.4 (2.4) | NS |

| Education (yrs) | 13.00 (0.9) | 14.7 (0.5) | NS |

| Cigarettes | 18.8 (2.4) | 20.4 (1.4) | NS |

| Physical work | 2.2 (1.0) | 3.8 (0.7) | NS |

| CO (ppm) | 25.3 (3.2) | 25.2 (1.8) | NS |

| Caffeine | 6.1 (0.9) | 3.8 (0.53) | 0.03 |

| Positive Affect | 23.5 (2.6) | 22.3 (1.5) | NS |

| Negative Affect | 4.0 (1.6) | 6.0 (0.9) | NS |

| FTND | 5.5 (0.38) | 5.4 (0.67) | NS |

| CESD | 8.8 (2.7) | 12.5 (1.5) | NS |

| STAI | 33.5 (2.6) | 35.7 (1.5) | NS |

| PSS | 11.6 (2.0) | 14.5 (1.1) | NS |

Note, means (standard error of the mean); NS = not significant; CO = carbon monoxide; FTND = Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence; CESD = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale; STAI = State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (Trait Form); PSS = Perceived Stress Scale.

A significant reduction in cotinine levels after the abstinence period was found compared with the ad libitum period (F (1, 42) = 23.0, p < 0.0001). This reduction was similar between those who relapsed and those who maintained abstinence (F < 1). Although significant cotinine concentrations were present after the 24-hour abstinence (95.0 ng/mL), these values were approximately 50% less than concentrations in the ad libitum condition, however (180.6 ng/mL). This reduction is consistent with data on cotinine half-life (Curvall et al. 1990) where abstinence for 24 hours was expected to lead to a decline of about 50% of cotinine concentrations. These results are also consistent with previous data obtained from smokers not interested in quitting after a period of 18-hour abstinence (al’Absi et al. 2002). Expired carbon monoxide readings after the 24-hour initial abstinence did not exceed 8 parts per million (ppm; M ± SEM = 4.56 ± .46). Carbon monoxide levels were lower after the abstinence period than before quitting (F (1, 39) = 75.7.8, p < 0.0001). No difference was found between relapsers and abstainers (F (1, 39) = 2.65, p > .1).

The acute stressors were associated with significant increases in measures of craving, withdrawal symptoms, and distress as well as reduction of positive affect among all participants (Fs (4, 36) > 3.7, ps < 0.01). However, differences were not observed in positive affect, withdrawal, or craving between participants who relapsed and those who maintained abstinence (Fs < 1; Table 2).

Table 2.

Craving and Withdrawal Symptoms

| Measures | Successful Quitters | Relapsers |

|---|---|---|

| Craving | ||

| Baseline rest 1 | 2.9 (0.7) | 3.4 (0.4) |

| Baseline rest 2 | 2.7 (0.8) | 3.1 (0.4) |

| Public Speaking | 3.0 (0.7) | 3.3 (0.4) |

| Public Speaking + 30 min | 2.2 (0.7) | 3.0 (0.4) |

| Cognitive tasks | 2.7 (0.7) | 3.4 (0.4) |

| Cognitive tasks + 30 min | 2.8 (0/7) | 3.1 (0.4) |

| Withdrawal Symptoms | ||

| Baseline rest 1 | 7.8 (1.9) | 8.6 (1.1) |

| Baseline rest 2 | 5.1 (1.7) | 7.3 (1.0) |

| Public Speaking | 7.0 (2.0) | 9.4 (1.2) |

| Public Speaking + 30 min | 6.2 (1.9) | 7.7 (1.1) |

| Cognitive tasks | 8.9 (2.3) | 11.0 (1.3) |

| Cognitive tasks + 30 min | 7.8 (2.0) | 8.9 (1.2) |

Means (standard error of the mean)

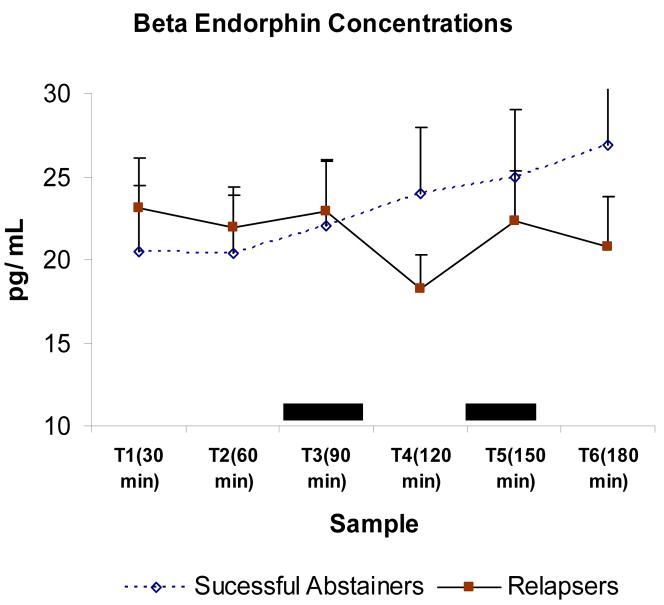

The two baseline measures of beta endorphin yielded no difference between relapsers and successful abstainers (F < 1). When analyzing all sample to examine changes over time due to the stressors, we found no main effect of group (F < 1), indicating no difference in the overall beta endorphin concentrations between those who relapsed and those who maintained abstinence. There was however significant differences among times (F (5, 21) = 2.96, p = 0.04) reflecting effects of the acute stressors (see Figure 2). Furthermore, we found a sample by group interaction (F (5, 21) = 2.8; p = 0.04). As shown in Figure 2, this was due to reduced responses to the acute stressors by the relapsing group relative to the successful abstainers. We further conducted simple effect tests comparing relapsers and abstainers at each sample and found no difference between the groups on any of the first three samples (T1, T2, T3) or on T5 (Fs<1). Abstainers however had significantly greater beta-endorphin concentrations than relapsers in T4 (obtained after the public speaking stress) (F (1, 35) = 4.17, p < 0.05). A similar, albeit not significant trend (F1, 33) = 3.47, p = 0.07) was found in beta endorphin concentrations obtained from T6 (obtained after the math stressor)

Figure 2.

Mean beta endorphin concentrations during the laboratory session. Bar lines represent standard error of the mean. Dark boxes indicate the acute psychological challenges. Sample by group interaction was significant (p < 0.05), due to attenuated responses by relapsers relative to successful abstainers.

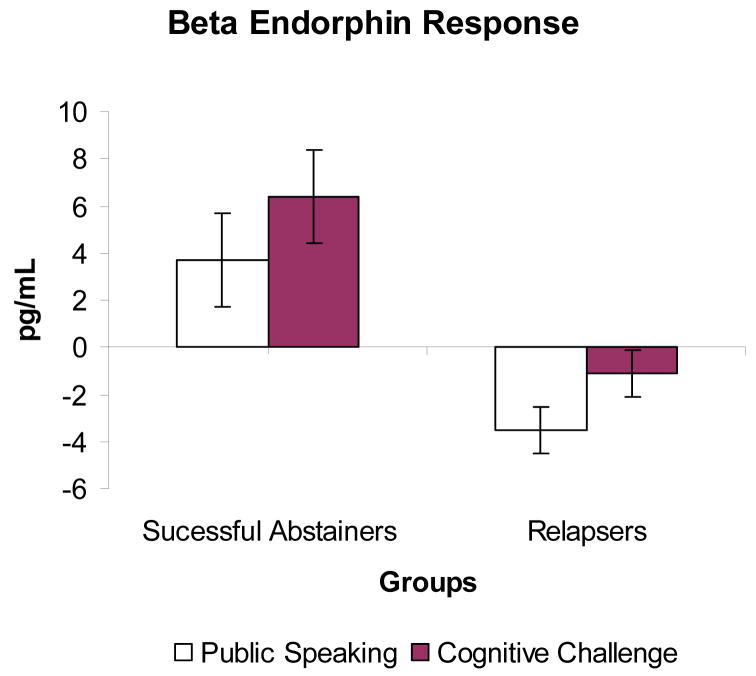

Further analyses using changes in beta endorphin levels after stress (calculated by subtracting the pre-stress T2 concentrations from average levels obtained after public speaking and after cognitive challenges) showed that responses to public speaking were greater in the successful abstainers than in relapsers (F (1, 29) = 5.7, p = 0.02; see Figure 3). Similarly, responses to mental math stress were greater in the abstainers than in the relapsers (F (1, 27) = 5.5, p = 0.03).

Figure 3.

Mean beta endorphin changes in response to the public speaking and cognitive stressors. Bar lines represent standard error of the mean. Relapsers exhibited smaller beta endorphin responses to both stressors than successful abstainers (ps < 0.05).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that attenuated beta endorphin response to stress was associated with early smoking relapse. This is a novel finding and is consistent with previous results showing that attenuated adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) responses to stress predicted early relapse (al’Absi et al., 2005). Beta endorphin response is formed from the same precursor protein (i.e., proopiomelanocortin) as ACTH (Guillemin et al., 1977), suggesting that the earlier findings may be due to changes at the level of the proopiomelanocortin expression and the hypothalamic-opioid interaction.

The present results extend previous evidence that a dysregulated stress response predicts smoking relapse (al’Absi et al., 2005). Although the release of beta endorphin is related to HPA activity, this hormone has a more defined and established role in reward and mood regulation (Herz, 1997). Administration of drugs of abuse including alcohol, cocaine, and nicotine, provides a reinforcing effect in part by stimulating beta endorphin and dopamine release in the ventral tegmental area and the nucleus accumbens (Nisell et al., 1994; Olive et al., 2001; Roth-deri et al., 2003; Pomerleau, 1998). These areas are integral to drug reward (Day and Carelli, 2007; Kalivas and Nakamura, 1999). The nucleus accumbens contains opioid receptors innervated by beta endorphin neurons (Khachaturian et al., 1984; Mansour et al., 1988). Higher beta endorphin expression in the nucleus accumbens increases dopamine release (Koob, 1992), reinforcing use of addictive substances as well as dissuading disuse of pleasurable stimuli (Salamone, 1994). A drop in beta endorphin release during the withdrawal state could lead to reduction in dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens making smokers more vulnerable to the rewarding effects of nicotine (Rasmussen et al., 2000; Laviolette and van der Kooy, 2003).

Mechanisms mediating the association of smoking relapse with attenuated beta-endorphin response to stress are not clear. It is possible that attenuated responses to stress reflect a long-term allostatic adjustment resulting from chronic exposure to nicotine (Koob & Le Moal 1997), in light of the observation that acute smoking increases beta endorphin (Pomerleau, 1998; Rasmussen, 1998). It is therefore possible that nicotine’s actions on levels of beta endorphin contribute to the reinforcing properties of smoking and enhance the benefits smokers draw from nicotine. Attenuated response during stress while smokers are in the process of quitting may prime smokers for greater reinforcement of smoking and may exacerbate abstinence effects on mood, although this hypothesis remains to be tested. The attenuated beta-endorphin response among smokers who relapsed may also be secondary to prolonged exposure to nicotine and other ingredients in cigarettes, possibly leading to long-term alteration of central dopaminergic and opioid systems (Koob and Moal, 1997). The impact of these long-term alterations may be accentuated during abstinence, increasing craving and enhancing the reinforcing properties of smoking. It is also possible that the stress hyporesponsiveness reflects a preexisting alteration in stress and emotion-related processing centers in the brain, such as forebrain and limbic functions (Robledo and Koob, 1993).

Although acute stress was associated with increase in both craving and distress among all participants, our results did not show differences in these measures between relapsers and those who maintained abstinence. This is in contrast to prior literature (Swan et al., 1996; Kenford et al., 2002). Previous research has shown that greater distress and drop in positive affect are linked to failed smoking cessation (Cohen and Lichtenstein, 1990; Covey, 1999; Brown et al., 2001). We note that subjective measures in our study were obtained from both groups after a required period of abstinence (i.e., the first 24 hours of a quit attempt) possibly limiting variance across the two groups.

The absence of differences between groups in resting measure of plasma beta endorphin is consistent with previous studies showing stable basal endorphin concentrations in smokers (Wewers et al., 1994). In the present study, smokers who relapsed and those who were successful in abstaining had comparable histories of smoking and level of nicotine dependence. They also had comparable baseline beta endorphin concentrations. This suggests that altered beta endorphin stress response in relapsers may have been specific to effects of chronic smoking on stress-related brain/limbic processing centers or to preexisting alterations in the stress response regulatory systems.

This study is limited by the small sample size that might have contributed to the lack of differences between the two groups of smokers in withdrawal or craving symptoms (Piasecki et al., 2002). The study design and sample size did not allow for a careful examination of sex differences or effects of smoking versus abstinence. Future studies should examine these effects and explore the interaction of different hormone systems with respect to relapse (Marchesi et al., 1997). The relationship between the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis and endogenous opioids and how they may mediate the effects of stress on smoking and relapse are particularly interesting to explore (del Arbol et al., 2000). Furthermore, research using blockade protocols are needed to directly examine the role of the endogenous opioid system in mediating the effects of stress in smoking behavior and relapse. Such research should also provide information on the therapeutic potential of opioid antagonism in smoking intervention (King and Meyer, 2000; Rukstalis et al., 2005; Epstein and King, 2004).

Because plasma beta-endorphin does not enter the brain in large quantities due to the blood brain barrier, we cannot conclude that the attenuated responses to stress directly affected centrally mediated craving and mood changes during early abstinence, and it is not clear whether altered central beta-endorphin processing is caused by chronic smoking. More research, including pharmacological blockade studies, is warranted to test these possibilities.

In summary, this study showed that early smoking relapse was associated with attenuated beta endorphin response to stress. This is consistent with previous research showing an altered HPA axis response to be a predictor of smoking relapse, and it demonstrates the need to further examine the relationships between the endogenous opioid system and the HPA axis in predicting relapse.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by National Institute of Health grants CA88272 and DA016351. We thank Clemens Kirschbaum, Ph.D., of Dresden University in Germany for help in assaying the hormonal samples and to Deanna Ellestad, Laurie Frank, and Angie Harju for help with the data collection and management of the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- al’Absi M, Bongard S, Buchanan T, Pincomb GA, Licinio J. Cardiovascular and neuroendocrine adjustment to public speaking and mental arithmetic stressors. Psychophysiology. 1997;34:266–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al’Absi M, Hatsukami D, Davis GL. Attenuated adrenocorticotropic responses to psychological stress are associated with early smoking relapse. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;181:107–17. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al’Absi M, Lovallo WR, McKey BS, Pincomb GA. Borderline hypertensives produce exaggerated adrenocortical responses to mental stress. Psychosom Med. 1994;56:245–50. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199405000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al’Absi M, Petersen KL, Wittmers LE. Adrenocortical and hemodynamic predictors of pain perception in men and women. Pain. 2002;96:197–204. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00447-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al’Absi M, Wittmers LE, Erickson J, Hatsukami D, Crouse B. Attenuated adrenocortical and blood pressure responses to psychological stress in ad libitum and abstinent smokers. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;74:401–10. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)01011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten JH, Reid K, Bierer M, Rigotti N. Smoking behavior and interest in quitting among homeless smokers. Addict Behav. 2004;29:1155–61. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrendero F, Kieffer BL, Maldonado R. Attenuation of nicotine-induced antinociception, rewarding effects, and dependence in mu-opioid receptor knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10935–40. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10935.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biala G, Budzynska B, Kruk M. Naloxone precipitates nicotine abstinence syndrome and attenuates nicotine-induced antinociception in mice. Pharmacol Rep. 2005;57:755–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyadjieva NI, Sarkar DK. The secretory response of hypothalamic beta-endorphin neurons to acute and chronic nicotine treatments and following nicotine withdrawal. Life Sci. 1997;61:PL59–66. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00444-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Kahler CW, Zvolensky MJ, Lejuez CW, Ramsey SE. Anxiety sensitivity: relationship to negative affect smoking and smoking cessation in smokers with past major depressive disorder. Addict Behav. 2001;26:887–99. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Zvolensky MJ. Distress tolerance and early smoking lapse. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25:713–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Lichtenstein E. Perceived stress, quitting smoking, and smoking relapse. Health Psychol. 1990;9:466–78. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.9.4.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covey LS. Tobacco cessation among patients with depression. Prim Care. 1999;26:691–706. doi: 10.1016/s0095-4543(05)70124-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox LS, Tiffany ST, Christen AG. Evaluation of the brief questionnaire of smoking urges (QSU-brief) in laboratory and clinical settings. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3:7–16. doi: 10.1080/14622200020032051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curvall M, Elwin CE, Kazemi-Vala E, Warholm C, Enzell CR. The pharmacokinetics of cotinine in plasma and saliva from non-smoking healthy volunteers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;38:281–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00315031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JJ, Carelli RM. The nucleus accumbens and Pavlovian reward learning. Neuroscientist. 2007;13:148–59. doi: 10.1177/1073858406295854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Arbol JL, Munoz JR, Ojeda L, Cascales AL, Irles JR, Miranda MT, et al. Plasma concentrations of beta-endorphin in smokers who consume different numbers of cigarettes per day. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;67:25–8. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00291-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilts RP, Kalivas PW. Autoradiographic localization of mu-opioid and neurotensin receptors within the mesolimbic dopamine system. Brain Res. 1989;488:311–27. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90723-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan CL, Cummings SR, Hudes ES, Zahnd E, Coates TJ. Quitting smoking: reasons for quitting and predictors of cessation among medical patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7:398–404. doi: 10.1007/BF02599155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein AM, King AC. Naltrexone attenuates acute cigarette smoking behavior. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;77:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvey AJ, Bliss RE, Hitchcock JL, Heinold JW, Rosner B. Predictors of smoking relapse among self-quitters: a report from the Normative Aging Study. Addict Behav. 1992;17:367–77. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90042-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianoulakis C. Endogenous opioids and addiction to alcohol and other drugs of abuse. Curr Top Med Chem. 2004;4:39–50. doi: 10.2174/1568026043451573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianoulakis C. Influence of the endogenous opioid system on high alcohol consumption and genetic predisposition to alcoholism. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2001;26:304–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales RA, Weiss F. Suppression of ethanol-reinforced behavior by naltrexone is associated with attenuation of the ethanol-induced increase in dialysate dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 1998;18:10663–71. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10663.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronwall D. Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task: A measure of recovery from concussion. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1997;44:373. doi: 10.2466/pms.1977.44.2.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemin R, Vargo T, Rossier J, Minick S, Ling N, Rivier C, et al. beta-Endorphin and adrenocorticotropin are selected concomitantly by the pituitary gland. Science. 1977;197:1367–9. doi: 10.1126/science.197601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatsukami DK, Dahlgren L, Zimmerman R, Hughes JR. Symptoms of tobacco withdrawal from total cigarette cessation versus partial cigarette reduction. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1988;94:242–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00176853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz A, Rommelspacher H, Graf KJ, Kurten I, Otto M, Baumgartner A. Hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, prolactin, and cortisol in alcoholics during withdrawal and after three weeks of abstinence: comparison with healthy control subjects. Psychiatry Res. 1995;56:81–95. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(94)02580-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz A. Endogenous opioid systems and alcohol addiction. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;129:99–111. doi: 10.1007/s002130050169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR. Tobacco withdrawal in self-quitters. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60:689–97. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.5.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Nakamura M. Neural systems for behavioral activation and reward. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9:223–7. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)80031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Stroud LR, Paronis CA. Smoking, stress, and negative affect: correlation, causation, and context across stages of smoking. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:270–304. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenford SL, Smith SS, Wetter DW, Jorenby DE, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Predicting relapse back to smoking: contrasting affective and physical models of dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:216–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khachaturian H, Dores RM, Watson SJ, Akil H. Beta-endorphin/ACTH immunocytochemistry in the CNS of the lizard Anolis carolinensis: evidence for a major mesencephalic cell group. J Comp Neurol. 1984;229:576–84. doi: 10.1002/cne.902290410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Meyer PJ. Naltrexone alteration of acute smoking response in nicotine-dependent subjects. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;66:563–72. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00258-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. Neural mechanisms of drug reinforcement. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;654:171–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb25966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Le Moal M. Drug abuse: Hedonic homeostatic dysregulation. Science. 1997;278:52–57. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan-Sarin S, Rosen MI, O’Malley SS. Naloxone challenge in smokers. Preliminary evidence of an opioid component in nicotine dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:663–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laviolette SR, Nader K, van der Kooy D. Motivational state determines the functional role of the mesolimbic dopamine system in the mediation of opiate reward processes. Behav Brain Res. 2002;129:17–29. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00327-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laviolette SR, van der Kooy D. Blockade of mesolimbic dopamine transmission dramatically increases sensitivity to the rewarding effects of nicotine in the ventral tegmental area. Mol Psychiatry. 2003;8:50–9. 9. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutfy K, Brown MC, Nerio N, Aimiuwu O, Tran B, Anghel A, et al. Repeated stress alters the ability of nicotine to activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. J Neurochem. 2006;99:1321–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour A, Khachaturian H, Lewis ME, Akil H, Watson SJ. Anatomy of CNS opioid receptors. Trends Neurosci. 1988;11:308–14. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(88)90093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchesi C, Chiodera P, Ampollini P, Volpi R, Coiro V. Beta-endorphin, adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol secretion in abstinent alcoholics. Psychiatry Res. 1997;72:187–94. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(97)00101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisell M, Nomikos GG, Svensson TH. Infusion of nicotine in the ventral tegmental area or the nucleus accumbens of the rat differentially affects accumbal dopamine release. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1994;75:348–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1994.tb00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olive MF, Koenig HN, Nannini MA, Hodge CW. Stimulation of endorphin neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens by ethanol, cocaine, and amphetamine. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC184. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-j0002.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald LM, Wand GS. Opioids and alcoholism. Physiol Behav. 2004;81:339–58. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens PC, Smith R. Opioid peptides in blood and cerebrospinal fluid during acute stress. Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;1:415–37. doi: 10.1016/s0950-351x(87)80070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecina S, Berridge KC. Hedonic hot spot in nucleus accumbens shell: where do mu-opioids cause increased hedonic impact of sweetness? J Neurosci. 2005;25:11777–86. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2329-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Grobe JE. Increased desire to smoke during acute stress. Br J Addict. 1992;87:1037–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb03121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki MP, Steinagel GM, Thienhaus OJ, Kohlenberg BS. An exploratory study: the use of paroxetine for methamphetamine craving. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2002;34:301–4. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2002.10399967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau OF. Nicotine and the central nervous system: biobehavioral effects of cigarette smoking. Am J Med. 1992;93:2S–7S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90619-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau OF. Endogenous opioids and smoking: a review of progress and problems. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23:115–30. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(97)00074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard WS, Robinson JH, Guy TD. Enhancement of continuous performance task reaction time by smoking in non-deprived smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992;108:437–42. doi: 10.1007/BF02247417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen DD. Effects of chronic nicotine treatment and withdrawal on hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin gene expression and neuroendocrine regulation. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23:245–59. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(98)00003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen DD, Boldt BM, Bryant CA, Mitton DR, Larsen SA, Wilkinson CW. Chronic daily ethanol and withdrawal: 1. Long-term changes in the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:1836–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robledo P, Koob GF. Two discrete nucleus accumbens projection areas differentially mediate cocaine self-administration in the rat. Behav Brain Res. 1993;55:159–66. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(93)90112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth-Deri I, Zangen A, Aleli M, Goelman RG, Pelled G, Nakash R, et al. Effect of experimenter-delivered and self-administered cocaine on extracellular beta-endorphin levels in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurochem. 2003;84:930–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rukstalis M, Jepson C, Strasser A, Lynch KG, Perkins K, Patterson F, et al. Naltrexone reduces the relative reinforcing value of nicotine in a cigarette smoking choice paradigm. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;180:41–8. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamone JD. The involvement of nucleus accumbens dopamine in appetitive and aversive motivation. Behav Brain Res. 1994;61:117–33. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(94)90153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon MN, Lazar-Wesley E, Grant KA, Kunos G. Proopiomelanocortin messenger RNA is decreased in the mediobasal hypothalamus of rats made dependent on ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1992;16:1147–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb00711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self DW, Nestler EJ. Relapse to drug-seeking: neural and molecular mechanisms. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;51:49–60. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman E, Strauss E, Spellacy F. Validity of the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test (PASAT) in adults referred for neuropsychological assessment after head injury. Clin Neuro-psychol. 1997;11:34–35. [Google Scholar]

- Smith R, Owens PC, Lovelock M, Chan EC, Falconer J. Acute hemorrhagic stress in conscious sheep elevates immunoreactive beta-endorphin in plasma but not in cerebrospinal fluid. Endocrinology. 1986;118:2572–6. doi: 10.1210/endo-118-6-2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch R, Lushene R. State–trait anxiety manual. Consulting Psychological Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Stitzer ML, Gross J. Smoking relapse: the role of pharmacological and behavioral factors. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1988;261:163–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan GE, Ward MM, Jack LM. Abstinence effects as predictors of 28-day relapse in smokers. Addict Behav. 1996;21:481–90. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters CL, Cleck JN, Kuo YC, Blendy JA. Mu-opioid receptor and CREB activation are required for nicotine reward. Neuron. 2005;46:933–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss F. Neurobiology of craving, conditioned reward and relapse. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2005;5:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wewers ME, Tejwani GA, Anderson J. Plasma nicotine, plasma beta-endorphin and mood states during pèriods of chronic smoking, abstinence and nicotine replacement. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994;116:98–102. doi: 10.1007/BF02244878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]