Abstract

Previous studies have consistently observed that women are more likely to perceive themselves as overweight compared to men. Similarly, women are more likely than men to report trying to lose weight. Less is known about the impact that self-perceived weight has on weight loss behaviors of adults and whether this association differs by gender. We conducted a cross-sectional analysis among an employee sample to determine the association of self-perceived weight on evidence-based weight loss behaviors across genders, accounting for body mass index (BMI) and demographic characteristics. Women were more likely than men to consider themselves to be overweight across each BMI category, and were more likely to report attempting to lose weight. However, perceiving oneself to be overweight was a strong correlate for weight loss attempts across both genders. The effect of targeting accuracy of self-perceived weight status in weight loss interventions deserves research attention.

Keywords: Perceived weight, weight loss attempts, gender, body mass index

Introduction

The health risks associated with being overweight and obese are well-established (Wyatt, Winters, & Dubbert, 2006), and include type 2 diabetes, heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, sleep disorders and certain types of cancer (Calle, Rodriguez, Walker-Thurmond, & Thun, 2003; Lucove, Huston, & Evenson, 2007). Prevalence estimates of overweight and obesity among US adults have increased steadily over recent decades, with an estimated 66% overweight or obese (Ogden et al., 2006). This trend is expected to continue, even in view of the call for public health attention to this important risk factor (US Department of Health and Human Services & Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2000).

Evidence supports that this increase in rates of overweight and obesity has been accompanied by decreased perceptions of overweight/obese status among persons who are overweight and obese. Johnson-Taylor and colleagues observed substantial decreases in the percentage of overweight (body mass index (BMI) 25.0-29.9 kg/m2) persons who perceived themselves to be overweight between the 1988-1994 (57% of men, 84% of women) and 1999-2004 (51% of men, 78% of women%) study periods of the National Health and Nutrition Surveys (Johnson-Taylor, Fisher, Hubbard, Starke-Reed, & Eggers, 2008). Previous studies have consistently observed that women are more likely to perceive themselves as overweight compared to men (Bish et al., 2006; Chang & Christakis, 2003; Paeratakul, Lovejoy, Ryan, & Bray, 2002; Schieman, Pudrovska, & Eccles, 2007; Wardle & Johnson, 2002). Similarly, women are more likely than men to report trying to lose weight (Bish et al., 2005; Chang & Christakis, 2003; Kruger, Galuska, Serdula, & Jones, 2004). Less is known about the impact that self-perceived weight has on weight loss behaviors of adults and whether this association differs by gender. Further research is needed to determine the utility of targeting accuracy of self-perceived weight as a motivator for weight loss among women and men in behavioral interventions.

The purpose of this study was to examine the association of weight perception and participation in evidence-based weight loss practices in a particular population, employees of six hospitals that are participating in an intervention promoting weight control through lifestyle changes. We also explore if these associations differ according to body mass index and gender.

Method

Study Design and Setting

Cross-sectional data from a site-matched randomized trial of an ecologic intervention promoting healthy eating and physical activity are used for this analysis. Details of the intervention and study design are published elsewhere (Pratt et al., 2007; Zapka, Lemon, Estabrook, & Jolicoeur, 2007). The study was conducted at six member hospitals of the largest health care system in central Massachusetts. Approximately 6,910 total employees were listed on human resources records in January, 2005.

Study Sample and Recruitment

A cohort of employees was selected for participation from human resources records of each hospital using a stratified simple random sampling (SRS) frame. Employees of each hospital were stratified according to gender and minority status, a SRS sample was selected from among the strata, with over-sampling of male and minority employees because they were under-represented among hospital employees. All eligible employees had a known non-zero sampling probability. Eligibility criteria included being between ages 18 and 65, English or Spanish speaking, planning to be employed at the hospital for the next 2 years, working at least 20 hours per week, not working in more than one participating hospital and the ability to be weighed and measured.

Employees were recruited from March to December, 2005. Lists of current employees were obtained through the Human Resources Offices at each site. An initial invitation letter signed by the Principal Investigator and the president of the individual hospital was sent to selected employees at their work address. Invited employees were enrolled in one of three ways: contacting study staff and scheduling an appointment, attending scheduled drop-in sessions or by being contacted by study staff to schedule an appointment. Two baseline assessments were conducted six months apart as part of the RCT. Both assessments collected anthropometric data. Baseline 1 collected demographic information. Baseline 2 collected behavioral and psychosocial survey data. 899 participants enrolled in the study (56% response rate), 849 (94.4%) of whom completed both baseline assessments.

Data Collection Methods

Data sources included human resources administrative data files; anthropometric measurements; and employee self-administered surveys. Human resources data provided information on gender, age, race/ethnicity and job category. Anthropometric measurements were conducted by trained study staff using a standardized protocol. Surveys were self-administered during in-person sessions, with the option to take surveys to complete at their convenience and return, taking approximately 15-30 minutes to complete.

Measures

Weight perception

Participants were asked to report their perception of their own current weight on a seven-point scale with responses ranging from very underweight to very overweight. Because few individuals reported themselves to be underweight, individuals who reported themselves as slightly, moderately or very underweight were collapsed into a single category. Thus, the variable used in analysis included five categories, underweight, just right, slightly overweight, moderately or very overweight.

Weight loss attempts

Participants reported (yes/no) whether they were currently trying to lose weight. For those who reported yes, a list of 12 categories of possible strategies and space to write down additional strategies was provided. Strategies were classified by a trained dietitian (VA). Eating strategies included: cutting calories/portions, low-fat diet, low-carb diet, joining a commercial weight loss program that provided meals (e.g. Jenny Craig) or not (e.g. Weight Watchers). Physical activity strategies included: walking, going to a gym or fitness center/class, and doing other recreational activities. Additional strategies included: use of medications or herbs to lose weight, hypnosis and past receipt of weight loss surgery.

Evidence-based weight loss attempts was defined according recommendations from several organizations, including the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (US Department of Health and Human Services & US Department of Agriculture, 2005), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, 1998), and the American Dietetic Association (Cummings, 2002), which recommend the use of both a reduction in caloric intake (through dietary modification) and increase in energy expenditure (through increased physical activity) for effective weight loss. A binary variable was then created to indicate evidence-based weight loss attempts. Secondary analyses were performed on separate indicators of weight loss attempts using dietary approaches and physical activity approaches.

Body mass index (BMI)

Measures of height and weight were collected in person by trained study staff at all data collection time points using standardized protocols. Weight measurements were taken on digital scales, and heights were measured using portable stadiometers. BMI was defined as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. The average BMI across baseline 1 and baseline 2 assessments were used. BMI was categorized according to standard classifications: underweight (BMI < 18.5), normal weight (BMI 18.5-24.9); overweight (BMI 25.0-29.9), class I obese (BMI 30.0-34.9), class II obese (BMI 35.0-39.9) and class III obese (BMI >= 40.0). Because few individuals were underweight (n=6 women, 0 men), this category was collapsed with the normal weight group.

Demographic characteristics

Gender was of primary interest in this analysis. Additional demographic co-variates included age group (18-40, 41-50, >50), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, other), and educational level (≤ high school, some post-high school/college, college graduate or more).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata SE 9.1 software (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). The analyses accounted for stratified sampling by site, gender and race, and were weighted by the inverse of the stratum-specific sampling probability. Frequency distributions described the total sample and contingency tables with chi-square statistics compared the characteristics of the sample according to gender. The bivariate associations of gender with self-perceived weight status and current weight loss attempts, stratified by BMI category, were then computed. Gender-specific multivariate logistic regression models were developed among persons who were overweight and obese (BMI ≥ 25.0 kg/m2) to assess the odds of current weight loss attempts associated with self-perceived weight status controlling for BMI and demographic characteristics. It was not possible to assess multivariate gender-specific models among the normal weight group (BMI < 25.0 kg/m2) because of insufficient cell sizes among men. A secondary model was conducted among the entire sample.

Results

A description of the study sample is presented in Table 1. Seventy-nine percent of participants were female and 30.5% were age 50 and over. The majority (87%) was non-Hispanic White and 13.1% had a high school degree or less. The distribution of BMI was approximately equal across categories, with 33.0% normal weight, 32.1% overweight and 34.8% obese. There were gender differences in the study sample (all P<.001). Women were less likely to be in the middle age group (41-50) (31.2% vs. 41.0%), more likely to be non-Hispanic White (88.0% vs. 80.8%) and less likely to have a college degree (38.6% vs. 45.7%) than men. There was a statistically significant difference when the BMI categorical variable was used. A lower proportion of men were in the normal and obese categories while greater proportion were in the overweight category then women.

Table 1. Employee characteristics by gender (n=899)*.

| Total | Women % | Men % | P-values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 21.0% | - | - | |

| Female | 79.0% | - | - | |

| Age Group | <.001 | |||

| ≤40 | 36.5% | 37.2% | 33.1% | |

| 41-50 | 33.0% | 31.2% | 41.0% | |

| > 50 | 30.5% | 31.6% | 25.9% | |

| Race/Ethnicity | <.001 | |||

| Asian/Other | 2.0% | 1.8% | 3.2% | |

| Hispanic | 6.0% | 5.4% | 6.4% | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 5.0% | 4.1% | 7.7% | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 87.0% | 88.8% | 80.8% | |

| Educational Status | <.001 | |||

| High school degree or less | 13.1% | 12.2% | 16.2% | |

| 1-3 years of college/post high school | 46.8% | 49.2% | 38.1% | |

| College graduate | 26.9% | 28.4% | 21.8% | |

| Master's or Doctoral degree | 13.2% | 10.2% | 23.9% | |

| BMI | <.001 | |||

| Underweight | .5% | .7% | 0% | |

| Normal | 32.5% | 35.5% | 21.4% | |

| Overweight | 32.1% | 28.1% | 47.1% | |

| Class I Obese | 20.4% | 20.1% | 21.2% | |

| Class II Obese | 9.8% | 10.6% | 6.6% | |

| Class III Obese | 4.7% | 5.4% | 3.7% | |

| Perceived weight status | <.001 | |||

| Underweight | 6.2% | 5.4% | 9.2% | |

| Just right | 17.3% | 15.5% | 23.8% | |

| Slightly overweight | 39.4% | 38.4% | 42.8% | |

| Moderately overweight | 23.5% | 24.8% | 18.8% | |

| Very overweight | 13.6% | 15.9% | 5.5% | |

| Current Evidence-Based Attempts to | <.001 | |||

| Lose Weight | ||||

| Yes | 43.7% | 47.6% | 29.0% | |

| No | 56.3% | 52.4% | 71.0% |

Analyses were weighted by the inverse of the stratum-specific sampling probability to account for sampling design.

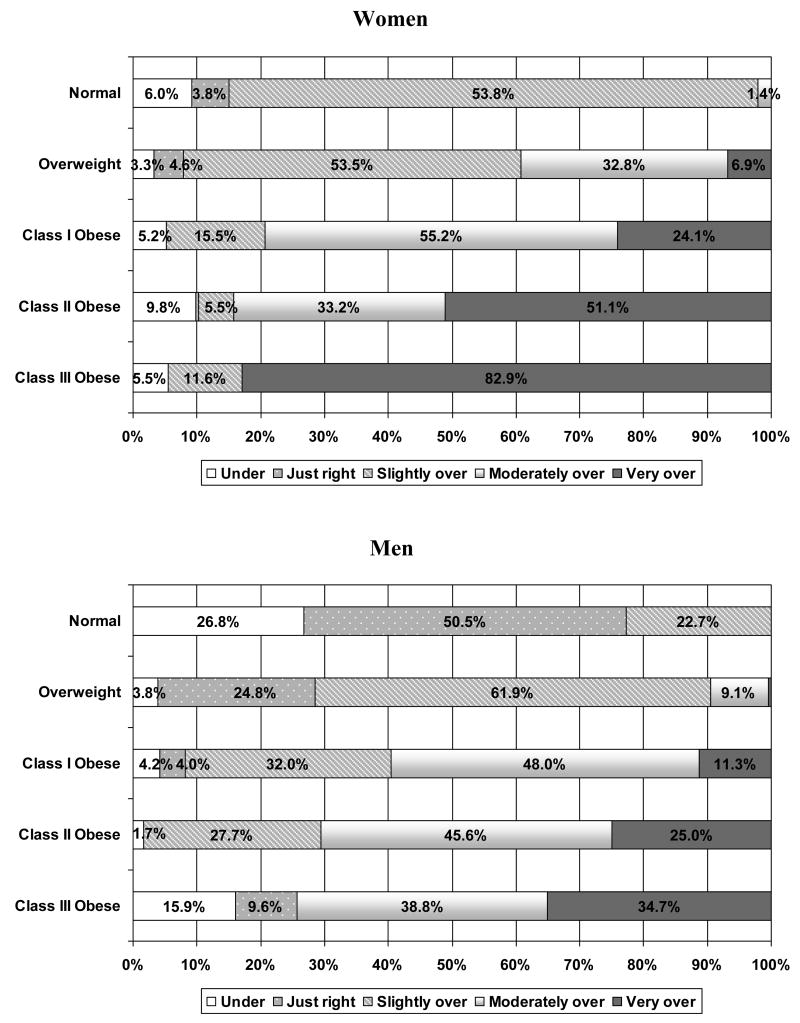

Gender Differences in Weight Perceptions among BMI Groups

Women were more likely to perceive themselves to be moderately or very overweight than were men (41% vs. 24%) (Table 1). Figure 1 details self-perceived weight status according to BMI category stratified by gender. Among the normal BMI group, men were more likely to perceive themselves as underweight (26.8% vs. 6.0%), while women were more likely to perceive themselves a slightly or moderately overweight (55.2% vs. 22.7%). Among the overweight BMI group, 53.5% of women considered themselves slightly overweight and 39.7% considered themselves moderately or very overweight, compared to 61.9% and 9.5% of men, respectively. Among the class I obese, women were more likely to consider themselves very or moderately overweight (24.1%, 55.2%, 15.5%, respectively) as opposed to slightly overweight compared to men (11.3%, 48.0%, 32.0%, respectively). These differences were more prominent among the class II and class III obese groups, although the unweighted numbers of participants in these categories was considerably smaller (women: class II n=67, class III n=35; men: class II n=18, class III n=11).

Figure 1. Perceived weight status according to gender and BMI*.

*Analyses were weighted by the inverse stratum-specific sampling probability to account for sampling design.

+ Percentages equal to < 1% not shown

Weight Loss Attempts

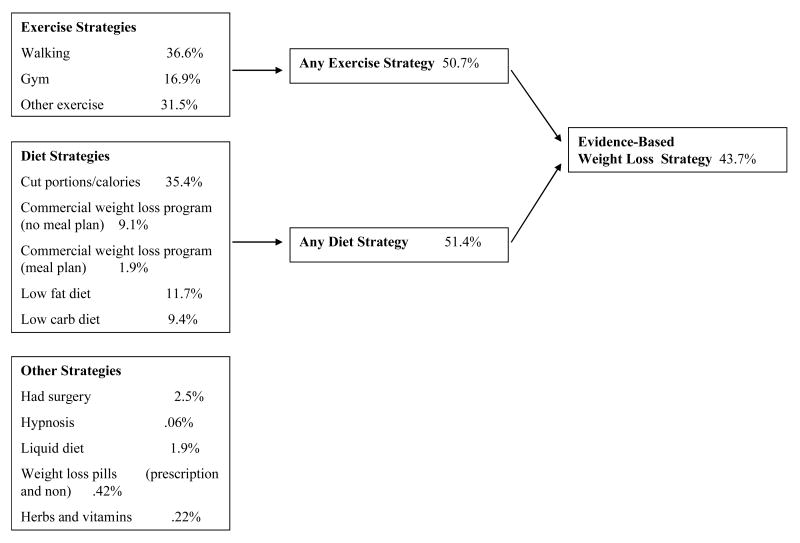

The majority of the sample (62.5%) reported that they were currently trying to lose weight using any method, which included 45% of the normal weight group, 65% of the overweight and 78% of the obese. Figure 2 describes specific weight loss strategies used. Fifty-one percent reported using dietary strategies to lose weight, with the same percentage reporting using an evidence-based physical activity strategy to lose weight. Less than half of the total sample (43.7%) reported current attempts to try to lose weight using evidence-based methods, which included using both dietary methods focused on reducing calories and increasing physical activity.

Figure 2. Prevalence of current weight loss strategies*.

*Analyses were weighted by the inverse of the stratum-specific sampling probability to account for sampling design

Current uses of non-physical activity and dietary weight loss strategies were uncommon. Less than one percent reported each of the following: liquid diets, prescription or non-prescription pills, herbs or other supplements, and hypnosis. Twenty-one individuals (2%) reported undergoing bariatric surgery. Of these 14.3% had normal BMI, 38.1% were overweight, and 23.8%, 9.5% and 14.3% were class I, class II and class III obese, respectively. The majority of this group (71.4%) reported using evidence-based physical activity and dietary strategies to lose weight. Perceived weight status was strongly correlated with BMI category (P<.001).

Gender Differences in Weight Loss Attempts

Women were more likely than men to report attempting to lose weight through evidence-based diet and physical activity strategies (47.6% vs. 29.0%). Table 2 describes gender differences in prevalence rates of current evidence-based weight loss attempts according to self-perceived weight status within BMI categories. Women were more likely to report evidenced-based weight loss attempts within each BMI and perceived weight status strata.

Table 2. Percentage reported current attempts to lose weight using evidence-based practices according to perceived weight status among gender and BMI strata*.

| WOMEN | MEN | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Over weight |

Class I Obese |

Class II Obese |

Class III Obese |

Normal | Over weight |

Class I Obese |

Class II Obese |

Class III Obese |

|

| Perceived weight status | ||||||||||

| Underweight | 2.0% | 0% | 11.7% | 16.7% | 0% | 0% | 13.1% | 0% | + | + |

| Just right | 14.4% | 0% | - | - | - | 2.4% | 0% | 0% | - | + |

| Slightly overweight | 58.1% | 62.4% | 68.9% | 91.6% | - | 24.7% | 36.8% | 34.4% | 79.3% | - |

| Moderately overweight | 88.7% | 57.5% | 76.2% | 28.0% | 36.6% | - | 61.2% | 46.0% | 70.9% | 37.0% |

| Very overweight | - | 46.5% | 50.1% | 58.4% | 57.3% | - | + | 75.8% | 26.3% | 17.1% |

Analyses were weighted by the inverse of the stratum-specific sampling probability to account for sampling design.

- No observations in cell.

+Cell size < 5.

Gender Differences in the Role of Perceived Weight Status on Weight Loss Attempts

Gender-specific logistic regression models (among persons with BMI ≥ 25.0 kg/m2) of the association of perceived weight status with current evidence-based weight loss attempts, controlling for BMI, age, race/ethnicity and education, are presented in Table 3. Among both genders, perceived weight status was strongly associated with weight loss attempts. The associations were somewhat stronger among men compared to women. Within gender, results for perceptions of being slightly overweight (women: OR=8.9; 95% CI=7.2, 11.1; men: OR=14.4; 95% CI= 9.3, 22.2) were similar to results for perceptions of being moderately overweight (women: OR=8.2; 95% CI=6.4, 10.6; men: OR=13.8; 95% CI= 8.5, 22.5). Although perceptions of being very overweight were strongly associated with weight loss attempts among both genders (women: OR=5.0, 95% CI=3.6, 6.8; men: OR=9.6, 95% CI=5.0, 18.4), these associations were less strong than for slightly and moderately overweight groups The gender-specific models in the entire sample (data not shown) showed similar results to the models only among persons with BMI ≥ 25.0 kg/m2. Analyses assessing the association of perceived weight status with secondary outcomes, weight loss attempts using dietary approaches or using physical activity approaches, yielded similar results to those of the analysis using both diet and physical activity weight loss strategies as the outcome.

Table 3. Logistic regression models of the association of perceived weight status with current evidence-based attempt to lose weight among persons with BMI ≥ 25.0 kg/m2*+.

| Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |

| Perceived weight status | ||

| Underweight | 0.78 (0.57, 1.1) | ± |

| Just right | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Slightly overweight | 8.9 (7.2, 11.1) | 14.4 (9.3 (22.2) |

| Moderately overweight | 8.2 (6.4, 10.6) | 13.8 (8.5, 22.5) |

| Very overweight | 5.0 (3.6, 6.8) | 9.6 (5.0, 18.4) |

Adjusts for BMI, age, race/ethnicity and education.

+Analyses were weighted by the inverse of the stratum-specific sampling probability to account for sampling design.

±Could not be calculated because of small cell sizes.

Discussion

Findings from this study of a demographically diverse health care system employee sample support that gender-differences in self-perception of weight status and dieting occur in adulthood and is consistent across BMI categories, which is similar to studies conducted with other samples (Bish et al, 2006; Frederick, Peplau, & Lever, 2006; Schieman et al., 2007; Wardle & Johnson, 2002). Women were overall less satisfied with their weight as shown by the majority perceiving themselves to be overweight. This was consistent across body mass index classifications, including those considered to be at normal weight. The majority of overweight and obese women (86%) perceived themselves to be overweight. However, more than half of normal weight women (52%) also perceived themselves to be overweight.

In contrast, men were much less likely to perceive themselves as overweight across each BMI category, consistent with previous findings (Chang & Christakis, 2003). Earlier reports found that adolescent males are less vulnerable to body dissatisfaction concerns, especially normal weight and overweight boys (Bearman, Martinez, Stice, & Presnell, 2006; Presnell, Bearman, & Stice, 2004). This study provides further evidence for this problem in our target population, as a third of overweight men perceived their weight as adequate even though there are high rates of overweight (BMI 25.0-29.9) (47%). Additionally, among men categorized as obese, there was a range of self-perceived weight status. For the extremely obese (BMI ≥ 40.0), approximately 25% reported themselves to be underweight or just right. Only approximately 35% rated themselves as very overweight. While this analysis is limited by extremely small sample size (n=11), findings suggest that this group in particular may be in need of interventions that target accuracy of weight perception and associated disease risks.

Many factors are likely associated with gender differences in weight perceptions. Differences in self-esteem (O'Dea & Abraham, 2000) and socio-cultural influences and expectations (Knauss, Paxton, & Alsaker, 2007; Myers & Crowther, 2007; Strahan, Wilson, Cressman, & Buote, 2006) likely contribute. A theoretical model developed by Smolak and colleagues proposes that individuals internalize ideal body types (Smolak & Levine, 2001). Females in Western culture are hypothesized to be most affected by the internalized socially sanctioned thin-ideal which is difficult to attain. Thus, it is hypothesized that the thin-ideal internalization may lead to body dissatisfaction and dieting, in addition to other psychological problems, such as eating disorders, guilt, shame and depression. This theory has been supported among adolescent girls and boys (Presnell et al., 2004), but has not been studied with regard to the association between weight perceptions on adaptive weight management efforts among adults. An additional contributor to gender differences in self-perceived weight status might be attributed to gender-differences in perceptions of standards imposed by others, including significant others and peers. This is consistent with the reflected appraisal process, which postulates that self-concepts of individuals can be shaped based on their perceptions of how others respond to them (Felson, 1985). Women may be more likely to be direct recipients of this type of feedback, and may be more susceptible to these influences than are men (McCabe, Ricciardelli, Sitaram, Mikhail, 2006). In addition, working with a sample of college aged women, Quinlivan and Leary observed that women may over-report their body dissatisfaction in an effort to maintain self-esteem and to gain positive reinforcement from others (Quinlivan & Leary, 2005).

The majority of weight loss attempts were consistent with dietary and physical activity evidence-based recommendations (US Department of Health and Human Services & US Department of Agriculture, 2005). Other methods were less common. Less than 2% of the study population had received weight loss surgery. Among those who had the surgery, the majority reported continuing to try to lose weight using diet and physical activity. A previous report in a sample seeking bariatric surgery found that the majority has previously attempted using conventional weight loss methods (Gibbons, 2006). The current study suggests that these efforts continue after surgery.

This is one of few studies examining associations between weight perceptions and adaptive weight loss efforts, rather than maladaptive efforts. We observed that perceptions of overweight, compared to perceiving one's weight as just right, were strongly associated with efforts to lose weight across genders and BMI categories. However, this association was less strong among those who considered themselves to be very overweight, as opposed to slightly or moderately overweight. We conducted an ancillary analysis (Data Not Shown) using the group that perceived themselves to be slightly overweight as the referent category. This revealed that among both women and men perception of being very overweight was associated with lower likelihood of trying to lose weight, compared to perception of being slightly overweight. It is possible that there is an optimal level of awareness/perception of overweight that motivates women and men to attempt to lose weight. Future longitudinal studies are needed to examine causal effects of weight perceptions on future weight loss efforts and could offer a strong basis for intervening to modify weight perceptions as a way to enhance motivation for weight loss efforts. However, interventions strategies should promote weight loss perceptions as a motivator, not a deterrent of weight loss and be careful not to leave individuals feeling hopeless. Motivation for weight loss efforts is known to be limited among overweight and obese individuals, most of whom fail to achieve weight loss (French, Jeffery, & Murray, 1999). Gregory and colleagues found that among a sample of 2,631 overweight and obese adults, perceptions that current weight was a threat to health was predictive of trying to lose weight (Gregory, Blanck, Gillespie, Maynard, & Serdula, 2008). Self-perceived weight is likely a multi-dimensional concept that captures several elements. Muennig and colleagues observed that greater differences between actual weight and self-reported ideal weight (percentage of desired weight loss), independent of actual BMI, were associated with greater number of physically and mentally unhealthy days in a national Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System sample (Muennig, Jia, Lee, & Lubetkin, 2008). Future studies should attempt to further delineate the meaning and implications of weight perceptions, as they are likely to be multi-factorial and have implication for health both directly and indirectly through behaviors.

The findings of this study related to gender and the influences of weight perception on weight loss behavior suggest several challenges to obesity prevention interventions. Promoting obesity prevention and weight loss must take into consideration weight perceptions. However, it is unclear what strategies can effectively target accurate weight loss perceptions. Accurate perception of healthy weight ranges for height is critical to fostering receptivity to messages regarding weight maintenance or weight loss goals. Additionally however, gender differences must be considered delicately because of the substantial proportion of the female population who are considered at normal weight by standardized measures, but are overly concerned about their weight. The differentiation of cultural expectations and norms from health related norms challenges the design of health promotions messages.

The health education literature highlights the importance of tailored interventions for targeting health behaviors (Slater, 1995). The results of this study suggest that educational campaigns and intervention efforts related to the importance of weight to health risk might miss the mark and be ineffective if individuals do not recognize or acknowledge that they are overweight. In addition, while often focusing on underassessment of weight, interventionists must also not lose sight of the proportion of people, particularly women, who over assess their weight as information on risk factors can result in unnecessary health concerns (Kuchler & Variyam, 2003). Social marketing principles (Andreasen, 1995) and communications theory (Grier & Bryant, 2005) emphasize careful consideration in the delivery of health-related messages. The most effective content of specific messages, delivery channel and message framing are likely to be different for different population segments, in this case by men and women and by BMI groups. These principles are exemplified by commercial entrepreneurs who have developed fitness centers specifically for women with easy access through multiple locations and short time requirements. Future intervention research targeting accuracy of weight perceptions as a motivator for weight loss attempts should evaluate the effectiveness of various segmented strategies.

This study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. The hospital worksite may not be representative of other occupational settings. While rates of overweight and obesity in this study were similar to national data (Ogden et al., 2006), the target population of hospital employees may differ from other workforces and the general population with respect to other key variables investigated. We conducted an ancillary analysis (data not shown) to determine whether there were differences between clinical employees (e.g. physicians, nurses, physician assistants, etc.) and non-clinical employees (e.g. managers, administrative assistants, clerical workers, laborers) with respect to these factors. Clinical employees, who comprised 61% of the workforce, were less likely to have a BMI ≥ 25.0 than were non-clinical employees (64.2% vs. 71.2%). Among obese employees, perceptions of being overweight were similar for clinical and non-clinical employees across each obesity class. However, among normal weight (52.6% vs. 28.7%) and overweight (83.0% vs. 72.5%) employees, clinical employees were more likely to perceive themselves as overweight. The association of perceived weight status with current evidence-based weight loss attempts, controlling for BMI and demographic factors, were similarly strong among both employee groups. These results suggest that while clinical hospital workers have greater perceptions of being overweight, the association between perceiving oneself as overweight and attempting to lose weight is comparable to that of non-clinical workers, who may be more similar to other occupational groups in the U.S with respect to knowledge related to weight and weight loss.

An additional limitation is that the response rate may have introduced selection bias, with persons who participated being more interested in controlling their weight. Additionally, weight perception was collected using only a single, general measure, and comparisons to other studies using different measures must be interpreted with caution (Kuchler & Variyam, 2003; Schieman et al., 2007). There were considerably more women in this study than men, which could impact findings. BMI is also an imperfect indicator of body composition. In particular, persons with muscular physiques can be misclassified as being overweight, particularly among men (Rothman, 2008). Lastly, weight loss attempts were measured by self-report and because of social desirability bias, may over-estimate actual attempts. Longitudinal studies that examine the prospective influence of weight perceptions on weight loss attempts, and studies that objectively measure the success of weight loss attempts are needed. Despite these limitations, this study provides convincing evidence of the importance of future research on the role of self-perception of weight status on weight loss efforts and studies to facilitate greater understanding of effective strategies aimed at promoting accurate self-perceptions of weight status among men and women.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Stephenie C. Lemon, Division of Preventive and Behavioral Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA

Milagros C. Rosal, Division of Preventive and Behavioral Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA

Jane Zapka, Division of Biostatistics, Bioinformatics and Epidemiology, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC

Amy Borg, Division of Preventive and Behavioral Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA

Victoria Andersen, Division of Preventive and Behavioral Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA

References

- Andreasen AR. Marketing social change: Changing behavior to promote health, social development, and the environment. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bearman SK, Martinez E, Stice E, Presnell K. The skinny on body dissatisfaction: A longitudinal study of adolescent girls and boys. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35:217–229. doi: 10.1007/s10964-005-9010-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bish CL, Blanck HM, Serdula MK, Marcus M, Kohl HW, 3rd, Khan LK. Diet and physical activity behaviors among Americans trying to lose weight: 2000 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Obesity Research. 2005;13:596–607. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bish CL, Michels Blanck H, Maynard LM, Serdula MK, Thompson NJ, Kettel Khan L. Health-related quality of life and weight loss among overweight and obese U.S. adults, 2001 to 2002. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:2042–2053. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348:1625–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang VW, Christakis NA. Self-perception of weight appropriateness in the United States. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2003;24:332–339. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung ST. The effects of chocolates given by patients on the well-being of nurses and their support staff. Nutrition and Health (Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire) 2003;17:65–69. doi: 10.1177/026010600301700108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings S, Parham ES, Strain GW. Position of the American Dietetic Association: Weight management. Journal of the American Dietietic Association. 2002;102:1145–1155. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90255-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felson R. Reflected appraisal and the development of self. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1985;48:71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Frederick DA, Peplau LA, Lever J. The swimsuit issue: Correlates of body image in a sample of 52,677 heterosexual adults. Body Image. 2006;3:413–419. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French SA, Jeffery RW, Murray D. Is dieting good for you?: Prevalence, duration and associated weight and behaviour changes for specific weight loss strategies over four years in US adults. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 1999;23:320–327. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons LM, Sarwer DB, Crerand CE, Fabricatore AN, Kuehnel RH, Lipschutz PE, et al. Previous weight loss experiences of bariatric surgery candidates: How much have patients dieted prior to surgery? Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2006;2:159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory CO, Blanck HM, Gillespie C, Maynard LM, Serdula MK. Perceived health risk of excess body weight among overweight and obese men and women: Differences by sex. Preventive Medicine. 2008;47:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grier S, Bryant CA. Social marketing in public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:319–339. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Taylor WL, Fisher RA, Hubbard VS, Starke-Reed P, Eggers PS. The change in weight perception of weight status among the overweight: comparison of NHANES III (1988-1994) and 1999-2004 NHANES. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2008;5:9. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knauss C, Paxton SJ, Alsaker FD. Relationships amongst body dissatisfaction, internalisation of the media body ideal and perceived pressure from media in adolescent girls and boys. Body Image. 2007;4:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger J, Galuska DA, Serdula MK, Jones DA. Attempting to lose weight: Specific practices among U.S. adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;26:402–406. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchler F, Variyam JN. Mistakes were made: misperception as a barrier to reducing overweight. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 2003;27:856–861. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucove JC, Huston SL, Evenson KR. Workers' perceptions about worksite policies and environments and their association with leisure-time physical activity. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2007;21:196–200. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-21.3.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe MP, Ricciardelli LA, Sitaram G, Mikhail K. Accuracy of body size estimation: Role of biopsychosocial variables. Body Image. 2006;3:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muennig P, Jia H, Lee R, Lubetkin E. I think therefore I am: Perceived ideal weight as a determinant of health. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:501–506. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers TA, Crowther JH. Sociocultural pressures, thin-ideal internalization, self-objectification, and body dissatisfaction: Could feminist beliefs be a moderating factor? Body Image. 2007;4:296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHLBI Obesity Education Initiative Expert Panel. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults (No NIH Pub 98-0483) Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Sep, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- O'Dea JA, Abraham S. Improving the body image, eating attitudes, and behaviors of young male and female adolescents: A new educational approach that focuses on self-esteem. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2000;28:43–57. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200007)28:1<43::aid-eat6>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paeratakul S, Lovejoy JC, Ryan DH, Bray GA. The relation of gender, race and socioeconomic status to obesity and obesity comorbidities in a sample of US adults. International Journal of Obesity & Related Metabolic Disorders. 2002;26:1205–1210. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt CA, Lemon SC, Fernandez ID, Goetzel R, Beresford SA, French SA, et al. Design characteristics of worksite overweight and obesity control interventions supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Obesity. 2007;15:2171–2180. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presnell K, Bearman SK, Stice E. Risk factors for body dissatisfaction in adolescent boys and girls: a prospective study. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;36:389–401. doi: 10.1002/eat.20045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlivan E, L E. Women's perceptions of their bodies: Discrepancies between self-appraisals and reflected appraisals. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2005;24:1139–1163. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman KJ. BMI-related errors in the measurement of obesity. International Journal of Obesity (2005) 2008;32 3:S56–59. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieman S, Pudrovska T, Eccles R. Perceptions of body weight among older adults: Analyses of the intersection of gender, race, and socioeconomic status. The Journals of Gerontology Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2007;62:S415–423. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.6.s415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater MD. Choosing audience segmentation strategies and methods. In: Maibach E, Parrott RL, editors. Designing health messages: Approaches from communication theory and public health practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. pp. 186–198. [Google Scholar]

- Smolak L, Levine MP. A two-year follow-up of a primary prevention program for negative body image and unhealthy weight regulation. Eating Disorders. 2001;9:313–325. doi: 10.1080/106402601753454886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahan EJ, Wilson AE, Cressman KE, Buote VM. Comparing to perfection: How cultural norms for appearance affect social comparisons and self-image. Body Image. 2006;3:211–227. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services, & Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and improving health and objectives for improving health. 2nd. Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services, & US Department of Agriculture. Dietary guidelines for Americans 2005. Washington, D.C: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J, Johnson F. Weight and dieting: Examining levels of weight concern in British adults. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 2002;26:1144–1149. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt SB, Winters KP, Dubbert PM. Overweight and obesity: Prevalence, consequences, and causes of a growing public health problem. American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 2006;331:166–174. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200604000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapka J, Lemon S, Estabrook B, Jolicoeur D. Keeping a Step Ahead -- Formative phase of a workplace intervention trial to prevent obesity. Obesity. 2007;15:27S–36S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]