Abstract

Background:

Fibronectin (FN) undergoes fragmentation in periodontal disease sites and in poorly-healing diabetic wounds. The biological effects of FN fragments on wound healing remain unresolved. This study characterized the pattern of FN fragmentation and its effects on cellular behavior compared to intact FN.

Methods:

Polyclonal antibodies were raised against FN and three defined recombinant segments of FN and used to analyze gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) from periodontal disease sites in systemically healthy and diabetic patients as well as chronic leg and foot wound exudates from patients with diabetes. Subsequently, the behavior of human gingival fibroblasts (hGF) and HT1080 reference cells were analyzed by measuring cell attachment, migration, and chemotaxis in the presence of intact FN or recombinant FN fragments.

Results:

FN fragmentation was evident in fluids from periodontal disease sites and diabetic leg and foot wounds. However, no fragmentation pattern distinguished systemically healthy patients from patients with diabetes. Both hGF and HT1080 cells required significantly higher concentrations of FN fragments to achieve attachment comparable to intact FN. Cells cultured on FN fragments also were morphologically very different from cells cultured on full-length FN. Migration was reduced for hGF cultured on FN fragments relative to full-length FN. In contrast, FN fragments increased HT1080 fibrosarcoma cell migration over intact FN.

Conclusions:

These experiments demonstrated that FN fragmentation is a prominent feature of both periodontal and chronic leg and foot wounds in diabetes. Furthermore, cell culture assays confirmed the hypothesis that exposure to defined FN fragments significantly alters cell behavior.

Keywords: Fibronectin, proteolysis, periodontal disease, diabetes, cell behavior, wound healing

INTRODUCTION

Understanding cell behavior during wound healing may be critical for designing strategies to treat poorly healing wounds. Among the mechanisms that control cell behavior are interactions of cells with intact and proteolytically modified forms of extracellular matrix molecules. For example, cleavages of laminin-5 (LM-5) by matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) and membrane type-1 (MT-1)-MMP result in enhanced migration of epithelial cells seeded on LM-5 1,2. The cleavage of LM-5 also exposes a putative pro-migratory site on the gamma-2 chain which is found in tumors and in tissues undergoing remodeling, but not in quiescent tissues 1. Similarly, processing of triple helical type I collagen molecules to the ¾ and ¼ initial cleavage fragments by MMP-1 is required for endothelial cell migration across a collagen matrix 3. It is noteworthy that recent data from our laboratory determined that MMP-2 is essential to migration of fibroblast and fibrosarcoma cells on a collagen matrix 4. Together these observations have provided important evidence that laminin and collagen as well as proteolytically modified forms of these molecules are essential for regulating cell migration.

Fibronectin (FN) is an essential high molecular weight dimeric glycoprotein of the extracellular matrix (ECM) which has discrete binding sites for collagen, heparin, fibrin, integrin receptors, DNA and bacteria 5,6. By virtue of these interactions, FN plays a key role in maintaining structural integrity of the ECM, cell attachment, spreading, and migration, and control of cell morphology and differentiation. FN is present in plasma at high concentration (0.3 mg/ml) and also occurs in a cellular membrane-associated form 7. Alternative splicing events result in a number of modified forms of FN that are associated with specific functions in aging and development 8,9.

In the context of wound healing, Wysocki and Grinnell 10,11 determined that FN was degraded to a greater extent in fluids from poorly healing diabetic wounds compared to normal wounds. Initial characterization of the proteolytic mechanism responsible for FN degradation pointed to elastase as a key enzyme (Grinnell, 1996)12. Yet, additional enzymes, including MMPs, are upregulated in diabetic wounds 13 and have the capacity to cleave FN 4,14,15. Gingival fluids collected from periodontal disease sites also contain FN fragments and that could result in part from activities of bacterially-derived proteases 16. Recently, the presence of fragments of FN was investigated in patients with periodontal disease, and 40-, 68-, and 120-kDa fragments were associated with severe periodontitis 17.

Extending from prevailing evidence supporting a concept according to which different modes of FN cleavage may produce protein fragments with unique biological properties, considerable effort has been devoted to deciphering the biological effects of discrete segments of FN. Cellular exposure to FN fragments alters the regulation of MMP expression. For example, a 120-kDa central FN fragment, which contains the cell binding region, elevated collagenase and stromelysin expression in rabbit synovial fibroblasts 18,19 and the urokinase-type plasminogen activator in periodontal ligament cells 20. Although an N-terminal 45-kDa gelatin binding fragment did not elicit similar proteinase responses in periodontal ligament cells 20, this fragment and a 29-kDa gelatin-binding FN fragment increased the gelatinolytic and collagenolytic activities along with concomitant proteoglycan release in bovine articular cartilage explant cultures 21. These observations indicate that responses to FN fragments are cell type specific. Interactions of HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells with intact FN enhanced activation of proMMP-2 by a mechanism involving processing of MT1-MMP to a shorter 45 kDa form 22. In comparison, we found that two recombinant fragments containing type II modules from the collagen binding segments of FN supported cell attachment, but reduced cellular activation of proMMP-2 and proMMP-9 compared to full-length FN 23. Recently, fibroblast interaction with the high-affinity heparin-binding domain of FN (modules III10-III15) was found to induce apoptotic events.24 The present studies expanded investigations on FN fragments corresponding to the collagen binding segment of FN, which is associated with the two type II modules in the N-terminal part of FN23. In addition, we engaged in analyses of two fragments from the central part of FN that were previously shown by others to occur by self-degradation of FN in the presence of Ca2+ and, interestingly, to possess gelatin and FN degrading properties.25,26

Because the observed in vitro effects may translate and be highly significant for in vivo diseases, wound healing, and tissue remodeling, understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying the cellular responses to FN-fragments is of both fundamental biological and clinical interest.

The data from the present experiments support the concept that the pathogenic events of poorly healing leg wounds are similar to those of periodontal disease. Having first detected the presence of specific segments among the FN degradation products in these wound types, our subsequent results demonstrated that the behavior of periodontal cells was significantly altered by exposure to well-defined FN fragments compared to intact FN.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Analyses of Wound Fluids

Wound fluid sampling procedures

Periodontal wounds

Adult patients with no history of recent dental care were screened from 2000-2003 at the University of Texas Health Science Center (UTHSCSA) Dental School for the presence of advanced periodontal disease. Criteria included radiographic alveolar bone loss exceeding 50% of the root length adjacent to at least 2 teeth and associated extensive, visible gingival inflammation. Two sites with periodontal disease were selected for sampling and the following parameters were then recorded: Age, gender, absence or presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) (self-reported), most recent blood glucose levels (if DM), and tooth type and number. Bone loss was measured from periapical radiographs and expressed in percent of the root length along the axis of the tooth (apex to CEJ) at each sampling site 27. Bone defects were measured from the most apical and clearly discernible aspect of the defects. Gingival fluid samples were collected on 2×10 mm sterilized filter strips placed gently into the periodontal pockets until slight resistance was felt and maintained in place until they were saturated or up to 30 sec. To prevent confounding effects from bleeding, no sites were probed prior to sampling and strips with visible blood were discarded. All periodontal defects were verified following sample collection. Samples were immediately placed in microcentrifuge tubes on ice and transported to the laboratory for storage at −80°C.

Leg and foot wounds

Study patients were adults with a confirmed diagnosis of type II diabetes and long-standing, poorly healing leg or foot wounds in the Foot Clinic at the Texas Diabetes Institute, University Hospital System, San Antonio, Texas. Wounds with infection or in treatment with proteolytic agents were excluded. The following parameters were recorded: Age, gender, most recent hemoglobin A1c level and/or blood glucose levels (laboratory or self reported), wound location, size, and duration. Wound fluid samples were collected on 3 × 10 mm sterile filter paper strips for up to 30 sec or until strip saturation. Samples with visible blood were discarded. Strips with wound fluid were placed on ice and transferred to −80° C.

Sample elution

To elute collected wound fluids, filters were placed in 0.7 ml microcentrifuge tubes with small holes in the bottom inserted into 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes. Fifty μl PBS was added to each filter for 1 min. The assembly was then centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 1 min and the eluted sample collected in the outer tube. Elution was repeated three times, and the protein concentrations were quantified by a bicinchoninic acid (BCA)-based assay.1

Preparation of Polyclonal Antibodies Specific for Intact and Fragmented Fibronectin

Polyclonal antibodies were raised against full-length and proteolytically digested human plasma FN as detailed previously4. In brief, aliquots of intact FN purified from human plasma by gelatin affinity chromatography28 and FN differentially digested with trypsin or chymotrypsin to yield multiple fragment sizes were pooled to constitute the immunogen for polyclonal antibody production. The titer of antibodies against FN was ∼3 × 105 by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

For antibodies against the collagen binding domain of FN, recombinant (r) I6I7 expressed in E. coli and purified as detailed previously23 was used as immunogen. For immunization of the rabbits, cleaved FN or rI6I7 were injected subcutaneously bi-weekly adhering to a standard 63-day protocol.2 Titers and specificities of the antisera were monitored by ELISA until reaching final titers of ∼1:3 x 105. Antibodies were immunoaffinity-purified for optimal specificity.

Antibodies specific for FN fragment 1043 (see below) were immunoaffinity purified from the rabbit serum raised against proteolytically digested human plasma FN4. In brief, r1043 was conjugated to periodate-oxidized Sepharose 4B beads3 at 1 mg protein/ml resin by reductive amination with sodium cyanoborohydride29 and blocked with ethanolamine. Anti-FN serum was diluted 10 fold by 20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, and applied to an r1043-conjugated Sepharose 4B affinity column. The column was washed with 0.5 M NaCl in 20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, and then with 20 mM Tris, pH 7.4. The specific anti-FN 1043 antibodies were eluted with glycine at pH 2.4, neutralized immediately with 1 M Tris pH 8.0, dialyzed against 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl overnight, and aliquoted for storage at −80 °C.

Collectively, these antibodies enabled us to detect virtually all possible FN fragments or specific FN segments 1043 and I6I7.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of wound fluids

Aliquots of wound fluid (∼10 μg/lane) were separated under reducing conditions (65 mM dithiothreitol (DTT)) by 7.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) according to Laemmli30. After transfer to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes,4 intact FN or fragments of FN in the samples were probed with affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies specific for trypsin/chymotrypsin-digested FN, r1043, or rI6I7. Western blotting procedures have been reported previously23, 31. Briefly, membranes were incubated with primary antibodies at 1:500 dilutions and target antigens visualized using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody5 diluted 1:5000, enhanced chemiluminescence reagents6, and autoradiography film.7

Analysis of FN fragmentation pattern

To analyze FN fragmentation patterns in the wound samples, images of films from Western blotting were captured using a digitizing camera and electrophoresis analytical software.8 Molecular masses for all FN fragments were then determined by their migration relative to the positions of prestained and regular high and low molecular mass standards.9 From this information and analyses with each specific antibody, we generated tables showing the presence or absence of each of the multiple FN fragments in each of the collected samples. These tables revealed fragmentation patterns and permitted comparisons of between individual patient samples and across patient groups.

Human Fibronectin and Recombinant Fibronectin Fragments

Purification of human fibronectin

FN was purified from human plasma by established procedures32 with the following modifications. Briefly, particulate matter was sedimented by centrifugation of the plasma at 3,000 × g for 20 min which was then diluted in chromatography buffer (50 mM Tris, 0.2 M NaCl, pH7.4) and loaded on a gelatin-Sepharose affinity column.3 After extensive washes with chromatography buffer alone, non-specifically bound proteins were removed with buffer containing 1 M NaCl, and bound FN was eluted with 10% (v/v) dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in chromatography buffer. FN was separated from co-eluted gelatin-binding MMP-2 and -9 by gel filtration using a preparative grade gel filtration column.10 Fractions were analyzed for purity by SDS-PAGE and the identity of the final product verified by Western blotting using anti-FN antibodies4. Elimination of MMPs-2 and -9 was verified by gelatin enzymography using 10% SDS-PAGE gels co-polymerized with heat-denatured type I collagen and processing as detailed previously.31, 33 Purified FN was quantified by the BCA assay,6 frozen slowly, and stored at −80° C.

Expression constructs for recombinant fibronectin segments

Three different segments of human FN were expressed as recombinant proteins in E.coli based on the DNA sequence of human plasma FN presented by Kornblihtt et al. (1985)34(GeneBank X02761). In the following, we use the prefix ”r“ for recombinant proteins, i.e. r1043, whereas the module type (I, II, or III) and number in the native protein are referred to as exemplified by ”I5-I9“. The designs for expression construct rI6I7, r1043, and r1177 are presented in Table 1 and were described previously in greater detail.23, 35 Coding cDNAs were amplified by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reactions (RT-PCR) (25 cycles; 94 °C 30 s, 62°C 1 min,72 °C 1 min 50s) from total RNA isolated from human gingival fibroblasts (hGFBS) as detailed previously.9, 36 HGF were isolated from gingival biopsies as described below. Specific oligonucleotide pairs added 5′-NheI and 3′-PstI restriction sites for directional ligation into the pGYMX expression vector, which expresses recombinant proteins with a 16 amino acid NH2-terminal fusion tag.37, 38 The fidelity of reactions and reading frames were verified by double-stranded chain termination DNA sequencing.11

Table 1.

Positions and characteristics of three recombinant FN segments

| FN fragment | FN modules | Amino acids | Mass (Da) |

|---|---|---|---|

| rI6I7 | I6-II1-II2-I7 | Gly275-Ala479 | 24,772 |

| r1043 | III5-III9 | Glu1043-Arg1407 | 40,932 |

| r1177 | III7-III9 | Arg1177-Arg1407 | 26,905 |

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins

Expression and purification of the recombinant FN segments followed procedures detailed in our prior reports with slight modifications31, 33. In brief, freshly transformed colonies of E.coli Le392F′ were cultured in super broth (1% Bactotryptone, 0.8% yeast extract, 0.5% NaCl) under selective pressure by 100 μg/ml ampicillin. Recombinant proteins that were expressed in inclusion bodies were dissolved and denatured with 8 M urea, 0.1 M NaH2PO4, 0.01 M Tris, pH 8.0, at 22 °C and then refolded by dialysis against 0.1 M B4Na2O7, pH 10.0, for 6 h at 22 °C. After extensive dialysis against chromatography buffer (100 mM NaH2PO4, 0.5 NaCl, pH 8.0) at 4 °C, refolded proteins were purified by Ni3+-Sepharose affinity chromatography according to established procedures23. Briefly, after sample loading and extensive washes in chromatography buffer, non-specifically bound bacterial proteins were removed first with 1.0 NaCl and then by elution with 35 mM imidazole in chromatography buffer. The bound recombinant protein then was eluted at high purity with 150 mM imidazole. Because rI6-I7, but not r1043 or r1177, bound gelatin, rI6I7 was further affinity-purified using a gelatin-Sepharose column23. In preparation for cell culture experiments, all recombinant proteins were dialyzed against PBS (137 mM NaCl, 2.68 mM KCl, 4.29 mM Na2HPO4, 1.47 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4), filter-sterilized, quantified by the BCA assay, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until analysis. Identities of the proteins were verified by their predicted migration by SDS-PAGE, correct masses by MALDI TOF mass spectrometry,12 and by Western Blotting using polyclonal affinity-purified anti-His6 antibodies.31

Cell Culture Experiments

Cell cultures

Primary cultures of human gingival fibroblasts (hGF) were generated from biopsies of gingiva according to published methods.39 Immediately upon procurement, tissues were placed into serum-free 50% Dulbecco's minimal essential medium/50% Ham F-12 (w/w) (DF)9 at RT °C and transported to the laboratory. Here, the tissue explants were rinsed with DF supplemented with 10% newborn calf serum (NCS), 2.5 μg/ml fungizone, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin,13 sliced into small pieces, and immobilized in tissues culture plates. Once extensive cell outgrowth from the tissues was evident, cells were expanded and stored in liquid nitrogen. Cells from passages 3 to 10 were used for all experiments. Established cell cultures were maintained in DF supplemented with 10% NCS, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Human fibrosarcoma HT1080 cells14 that served as control cells in these studies were maintained in α-minimal essential medium (α-MEM)9 containing 10% newborn calf serum (NCS), 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin.

Cell attachment assay

Tissue culture-treated 96-microwell plates were coated with 2-fold serially diluted FN, rI6I7, r1043 or r1177 (typically 25 - 0.5, and 0 μg/ml) in 100 μl PBS/well for 18 h at 4 °C. After blocking with 10 mg/ml heat-denatured bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 min, 4 × 104 cells were added per well in serum-free α-MEM to avoid confounding effects from serum proteins and incubated for ∼90 min at 37 °C. Non-attached cells were removed by gentle rinses with PBS. Attached cells were then fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS and stained with 0.1% crystal violet in 200 mM boric acid, pH 6.0. After extensive rinses to remove free dye, cell-bound stain was dissolved with 10% acetic acid and quantified by measurement of the optical density at 590 nm in a microplate reader.15 Cell attachment to non-coated but BSA-blocked wells served to adjust for nonspecific attachment. Experiments were performed in duplicate or triplicate and repeated several times, but results from different conditions were only compared for experiments on the same plate.

Cell morphology assay

Glass cover slips (1 cm2)16 were coated overnight at 4 °C with FN, rI6I7, r1043, or r1177 at concentrations that resulted in half-maximal attachment in the preceding assays. Non-specific binding sites were blocked with 10 mg/ml heat-inactivated BSA and 5 × 103 hGF or HT1080 cells per slide were seeded in a chemically defined, serum-free medium.17 After 12 h in the tissue culture incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2), two slides from each condition were rinsed with PBS and fixed with 4% formaldehyde and 5% sucrose in PBS. Slides were rinsed, air-dried, and stained with crystal violet. At least 100 cells per experimental condition were measured at a 200 × magnification to determine the morphological parameters cell area and cell length (straight line between two most distant points) from images captured with a research light microscope18 and using image analysis software.19

Cell migration assay

Cell migration on surfaces coated with intact FN and FN segments was quantified by the expansion of cells deposited in standard-sized areas. Briefly, cells suspended in serum-free α-MEM to eliminate any confounding effects from serum proteins were seeded at 2 × 105/ml into wells formed by perforated membranes in close contact with tissue culture-treated coverslips.20 The coverslips were coated with 25 μg/ml FN, r1043, r1177, or rI6I7 in PBS overnight at 4°C and non-specific binding sites were blocked with BSA. After a 2 h attachment period in the tissue culture incubator (37°C, 5% CO2 in air), membranes were removed, medium added, and the migration monitored for 2-3 days. To reduce confounding effects from serum proteins, media contained the pre-determined minimal concentration of NCS that allowed for cell viability and migration (cell type specific; 0.1-0.25%). Slides with cells were then fixed and stained with crystal violet, and cell migration was quantified digitally by the change in size of cell areas from images captured at a 10-fold magnification using the light microscope18 and image analysis software.19 The diameter and area were measured for each cell area. For the diameter, we used the average of three measurements taken different angles across the center. The area was defined by carefully outlining the outer border of the cells. Changes were calculated by adjusting for baseline values and expressed by the mean and standard deviation from analyses of at least three circles of cells for each experimental condition. To reduce measurement errors, one calibrated examiner analyzed all cell areas.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis included Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U tests with Bonferronis correction for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Fibronectin fragmentation in periodontal crevicular fluid from healthy and diabetic patients

Gingival crevicular fluid samples were collected and analyzed from 7 patients with type 2 diabetes and 11 systemically healthy patients. The demographics of the study patients are presented in Table 2. Based on the most recent blood glucose level (≤ 140 mg/dl = well controlled; 140-200 mg/dl = moderate; ≥ 200 mg/dl = poorly controlled) or glycosylated hemoglobin test (≤8% = well controlled; 8-10% = moderate, ≥10% = poorly controlled), one study patient had well-, one had moderately-, and five had poorly-controlled diabetes. Clinical examinations after sample collection verified that all sampled sites were characterized by moderate to advanced periodontal disease. In addition to having >50% radiographic bone loss and gingival inflammation, all sites displayed bleeding on probing and probing depths greater than 5 mm.

Table 2.

Distribution of patients from whom periodontal fluid samples were collected

| A. Patients with Diabetes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Sex | TT1 | BL%2 | Glu3 | HgAlc4 |

| 55 | F | S | 50 | 160 | 10.9 |

| 36 | M | S | 35 | 239 | 9.6 |

| 47 | M | S | 50 | 198 | -5 |

| 58 | M | S | 50 | -5 | 9.9 |

| 63 | M | MS | 50 | 133 | -5 |

| 63 | M | S | 50 | 121 | 6.3 |

| 49 | F | M | 50 | 300 | - |

|

B. Systemically Healthy Patients | |||

| 25 | F | S | -5 |

| 52 | F | S | 50 |

| 51 | M | MS | 35 |

| 29 | M | S | 60 |

| 44 | F | MS | 60 |

| 78 | F | S | 60 |

| 63 | F | M | 50 |

| 37 | F | S | 60 |

| 55 | M | S | 50 |

| 46 | F | S | 50 |

| 35 | M | M | 80 |

TT, Tooth type: S = single-rooted; M = multiple-rooted; MS = Both single and multi-rooted

BL%, Percent radiographic bone loss at time of sampling (% of root length)

Glu, most recent reported blood glucose level (mg/dl)

HgAlc, Most recent glycosylated hemoglobin laboratory value (%)

Data not collected / recorded at time of sampling

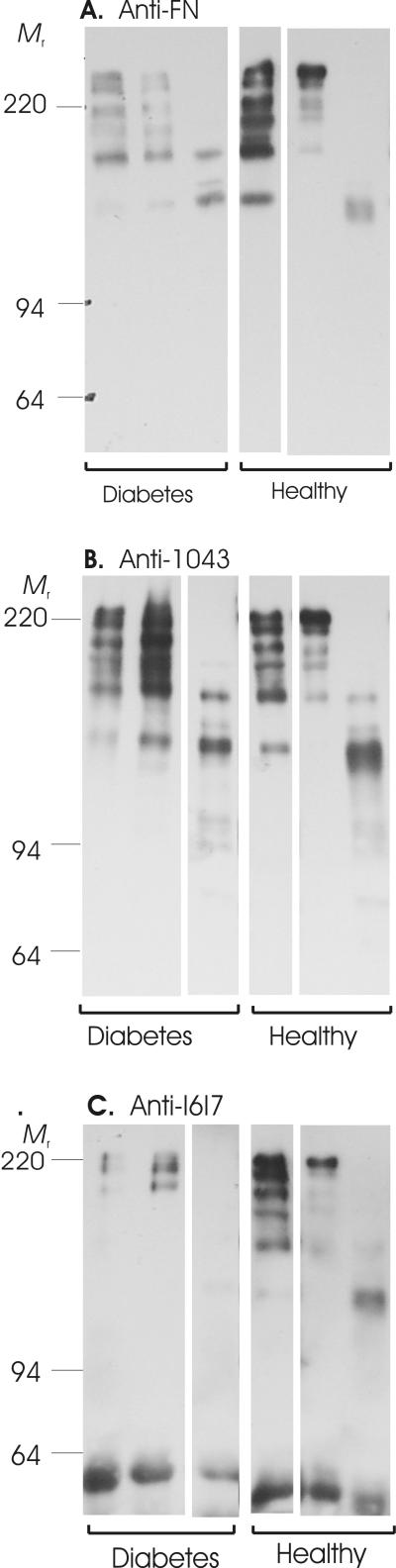

Using antibodies reacting with either multiple proteolytic FN fragments or well-defined segments of FN, we analyzed the collected wound fluids by Western blotting. Representative Western blots are presented in Figure 1. The analyses detected multiple FN fragments in periodontal wound fluids from both diabetic and non-diabetic subjects (Fig. 1A). Analyses with antibodies specific for r1043 and rI6I7 demonstrated that these segments were contained within several FN fragments of different sizes (Fig. 1B, C).

Figure 1.

Fibronectin fragmentation in gingival crevicular fluid (GCF). Samples collected from periodontal pockets with moderate to advanced clinical disease in systemically healthy (Healthy) and diabetic patients (Diabetes) (See Table 2 for patient demographics) were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and probed in Western blots with affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies specific for either a broad range of FN fragments (Panel A), FN segment 1043 (Panel B), or FN segment I6I7 (Panel C). Shown are representative samples from healthy and diabetic patients. Masses (kDa) of reference proteins are indicated (Mr).

To understand whether the samples collected from diabetic and non-diabetic periodontal disease sites had unique fragmentation patterns, the frequency of occurrence and molecular weights (masses) of all fragments were determined. Of note, due to difficulties in collecting sufficient amounts of fluid from some sites, we were not able to perform full fragment spectrum analyses for all samples. Among all fragments detected using the α-FN antibodies, fragments of 135 and 155 kDa were frequent in both diabetic and non-diabetic patients. Only fluids from diabetic patients contained 125 and 174 kDa bands, and the healthy patients had a 148 kDa fragment not seen in diabetes, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Masses and frequencies of FN-fragments detected with analytical antibodies in GCF samples from diabetic and systemically healthy subjects

| Analytical antibodies1 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mr3 | α-FN4 | α-I6I75 | α-10436 | |||

| DM2 | H2 | DM | H | DM | H | |

| 220 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| 213 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 208 | 1 | |||||

| 202 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 192 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 188 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| 182 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 174 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 166 | 2 | 3 | 1 | |||

| 155 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 148 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| 144 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| 135 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| 125 | 3 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 118 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |||

| 112 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 108 | 1 | |||||

| 77 | 1 | |||||

| 68 | 1 | |||||

Antibodies specific for FN fragments (α-FN), I6I7 (α- I6I7), and 1043 (α1043)

DM denotes subjects with diabetes and H systemically healthy subjects

Masses of FN fragments in kiloDaltons (kDa)

5 samples from patients with DM and 5 samples from patients without DM

3 samples from patients with DM and 3 samples from patients without DM

4 samples from patients with DM and 3 samples from patients without DM

The 1043 segment-specific antibodies reacted with multiple fragments (Fig. 1B), several of which had similar masses as those detected with the α-FN antibody (Fig. 1A). Among patients in the diabetes group only, the 1043 segment was frequently detected in a 118 kDa fragment (4 of 4 subjects) and in 148 and 188 kDa fragments (3 of 4 subjects) (Table 3).

Segment I6I7 was observed most frequently in diabetic subjects in a FN fragment of 202 kDa (2 of 3 subjects) (Fig. 1C, Table 3). In general, we had less reactivity among the fragments with the α-I6I7 antibody. It is perceivable that the proteolytic cleavage of FN altered the antigenic epitopes or the epitope presentation leading to reduced recognition by this antibody.

Comparison of samples from systemically healthy and diabetic patients found only one fragment of 174 kDa which was common in diabetic patients and reacted with all three antibodies, but was not detected in healthy subjects. Overall, our analyses detected significant FN fragmentation in sites with periodontal disease. However, besides the possible single 174 kDa fragment indicator, we did not identify a distinct global FN fragmentation pattern in periodontal lesions which distinguished patients with diabetes from systemically healthy patients (Table 3, Fig. 1),

FN fragmentation in poorly healing leg wounds

To test the working hypothesis that FN fragmentation is a phenomenon of both longstanding periodontal and leg or foot wounds, we analyzed wound fluid samples collected from poorly healing leg or foot wounds in patients with diabetes. Samples were collected from such wounds in 22 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. See Table 4 for patient demographics. Among these patients with diabetes, 6 were classified as having good, 5 moderate, and 13 poor glycemic control. The 25 wounds had been present for periods of 3 weeks to 12 years, and ranged in size from 4 mm to 200 mm in diameter at the time of sample collection.

Table 4.

Distribution of patients with chronic foot or leg wounds and diabetes mellitus1 from whom fluid samples were collected

| No. | Age | Sex | Glu2 | HgAlc3 | Site4 | Time5 | Size6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 53 | M | -7 | 8.4 | f | 6 m | - |

| 2 | 45 | M | 246 | 8.6 | t | 12 y | 7 |

| 3 | 55 | F | 160 | 10.9 | f | 1 m | 10 |

| 4 | 53 | M | - | 7.7 | l | 1 y | 200 |

| 5 | 36 | M | 239 | 9.6 | f | 2 w | 10 |

| 6 | 41 | M | 135 | 8.3 | f | 2 m | 30 |

| 7 | 53 | M | 224 | 8.4 | f | 4 y | 15 |

| 8 | 58 | M | 134 | 6.8 | f | 2 y | - |

| 9 | 50 | M | - | - | f | 1 y | 20 |

| 10 | 47 | M | 198 | - | f | 6 m | 30 |

| 11 | 60 | M | 155 | - | f | 4 m | 10 |

| 12 | 42 | M | 153 | - | f | 1 m | 20 |

| 13 | 58 | M | - | 9.9 | f | 1 m | 7 |

| 14 | 49 | M | 140 | 7 | t | 3 w | 7 |

| 15 | 60 | M | - | - | f | 7 m | 4 |

| 16 | 55 | M | 276 | - | f,l | 5 m | 30 |

| 17 | 48 | F | 200 | - | f | 8 m | 15 |

| 18 | 60 | M | 190 | - | f | 6 w | - |

| 19 | 36 | F | 170 | - | f | 5 w | 10 |

| 20 | 84 | M | 80 | 5.8 | l | 9 m | 50 |

| 21 | 38 | F | 97 | - | l | 4 w | 20 |

| 22 | 72 | M | 160 | 7 | f | 1 m | 50 |

| 23 | 43 | F | 180 | - | f | 2 m | 45 |

| 24 | 49 | M | 287 | 11.5 | t | 5 m | 6 |

| 25 | 45 | M | 176 | 8.5 | f | 1 m | 115 |

Subject reported having diabetes mellitus and verified by medical record, if available.

Glu, most recent blood glucose level (medical record or self-recorded) in mg/dl

HgAlc, most recent glycosylated hemoglobin laboratory value in %

Location of wound (f = foot, l = leg, t = toe)

Self-reported time since wound first appeared (w = weeks, m = months, y = years)

Diameter of wound at time of sampling (mm)

Data not collected / recorded at time of sampling

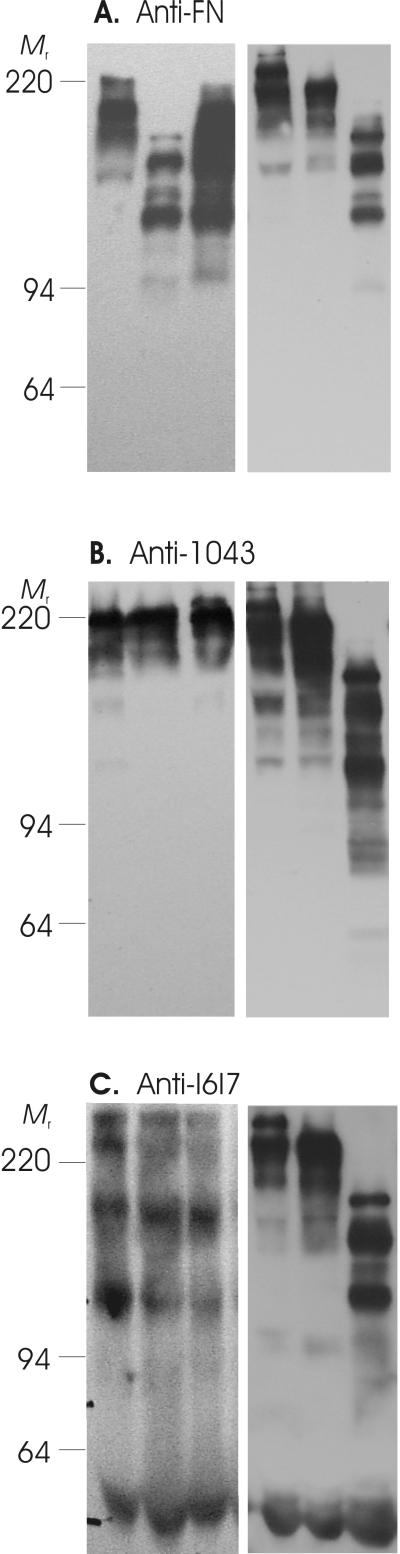

The collected wound samples were analyzed with the same antibodies and procedures used for periodontal crevicular fluids to allow for comparison of the results. Confirming the initial observations by Wysocki and Grinnell, 199010, we detected FN fragmentation in wounds from all subjects (Figure 2) and, furthermore, demonstrated that multiple fragments contained the I6I7 and 1043 segments of FN.

Figure 2.

Fibronectin fragmentation in diabetic foot and leg wound fluids. Samples were obtained from poorly healing foot or leg wounds in patients with diabetes (Table 4 shows patient demographics). After separation by SDS-PAGE, samples were transferred to PVDF membranes, and fragments detected with affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies as detailed under Experimental Procedures and in the legend for Fig. 1, which reacted specifically with multiple FN fragments (Panel A), FN segment 1043 (Panel B), or FN segment I6I7 (Panel C). Blots show representative samples and protein mass standards (Mr).

Wound samples from these patients with diabetes exhibited FN fragments with masses ranging widely from 68 to 213 kDa (the ∼220 kDa band being native FN) (Fig. 2, Table 5). The 1043 segment was most frequent in 112 kDa, 144 kDa, and 182 kDa fragments (each in 6 of 22 samples), and in 125 kDa and 135 kDa fragments (each in 5 of 22 samples). In comparison, the I6I7 segment was most frequently detected in 77 kDa, 135 kDa, and 202 kDa fragments (18, 10, and 9 of 22 samples, respectively).

Table 5.

Massesand frequencies of FN-fragments detected in leg and foot wound samples from diabetic subjects

| Analytical antibodies |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mr1 | α-FN2 | α-I6I73 | A-10433 |

| 220 | 9 | 11 | 11 |

| 213 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 208 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 202 | 9 | 2 | |

| 192 | 5 | 7 | |

| 188 | 2 | 3 | |

| 182 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| 174 | 7 | 3 | 4 |

| 166 | 9 | 7 | 2 |

| 155 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 148 | 2 | ||

| 144 | 2 | 6 | |

| 135 | 8 | 10 | 5 |

| 125 | 3 | 8 | 5 |

| 118 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 112 | 1 | 6 | |

| 108 | 8 | 8 | 1 |

| 77 | 18 | 4 | |

| 68 | 6 | 1 | |

Mass (molecular weight) of FN fragments

Based on 21 samples from patients with diabetes

Based on 22 samples from patients with diabetes

It is noteworthy that FN fragments with apparently similar masses containing 1043 (213, 208, 188, 174, 166, 148, 144, and 118 kDa) and containing I6I7 (202, 192, and 174 kDa) were detected in both poorly healing leg wounds (Table 5) and in periodontal disease sites (Table 3).

Cell behavior is modified in the presence of FN fragments

Having defined the fragmentation patterns of FN in periodontal disease and diabetic foot and leg wounds, we investigated whether FN fragments had the potential to alter cell behavior and thereby potentially also wound healing. For this purpose, we generated first recombinant FN segments rI6I7, r1043, and r1177, which were present in the FN fragments in the wounds. Subsequently, we quantified alterations in cell attachment, morphology, and migration on coated full-length FN and the FN fragments, and also chemotactic migration for cells exposed to these proteins in soluble form. Cells analyzed were primary human gingival fibroblasts and HT1080 cells as a control.

Cell Attachment

All tested FN segments supported cell attachment but efficiency of cell attachment varied significantly. To compare cell attachment properties between the proteins, a concentration range of protein was coated onto experimental surfaces enabling determination of the molar concentration which yielded half-maximal cell attachment for each cell line. The molar concentration for half-maximal attachment to full-length FN was 2.5×10−9 M and 1.1 × 10−9 M for hGF and the HT1080 reference cells, respectively (Table 6). In comparison, the three analyzed FN-fragments (1043, 1177, and I6I7) required nearly a 100-fold higher molar concentrations over that of full-length FN to achieve half-maximal attachment for either hGF or HT1080 (Table 6). For hGF, the total cell attachment at half-maximal and maximal levels was also less than that found with full-length FN.

Table 6.

Concentrations of intact FN and defined FN segments required to achieve half-maximal attachment of hGF and HT1080 cells

| Cell Line |

||

|---|---|---|

| Protein | hGF | HT1080 |

| FN | 2.5 × 10−9 M1 | 1.1 × 10−9 M |

| r1043 | 4.8 × 10−7 M* | 5.7 × 10−7 M* |

| r1177 | 1.5 × 10−7 M* | 1.3 × 10−7 M* |

| rI6I7 | 6.6 × 10−7 M* | 3.5 × 10−7 M* |

Protein coating concentration that yielded half-maximal cell attachment

P<0.05 versus FN (Kruskal-Wallis and Mann Whitney)

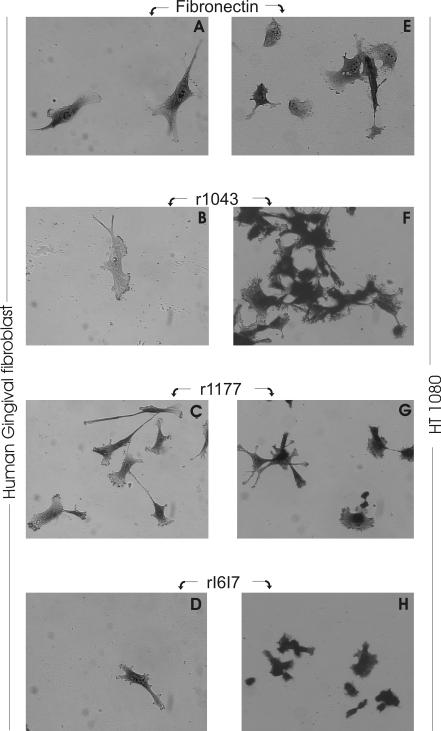

Cell Morphology

Using coating concentrations which yielded half-maximal cell attachment in the preceding cell attachment assays (Table 6), we subsequently characterized the effects of full-length FN and each of the defined recombinant FN segments on the morphology of hGF and HT1080. Experiments analyzed cell lengths and areas from captured images of cells 12 hours after seeding. Representative images are presented in Figure 3. Cells on intact FN and on FN fragments had visibly different cell shapes by light microscopy (Fig. 3). While hGF on full-length FN demonstrated good spreading, cells seeded on either of the FN segments were characterized by extension of delicate filopodia and less spreading (Fig. 3). HT1080 cells also spread less and former clusters of cells. On r1177, HT1080 extended fine filipodia and cells on rI6I7 remained in clusters with virtually no spreading. From quantification of more than 100 cells per condition, we found that both hGF and HT1080 cells seeded on full-length FN were significantly (P<0.001) longer and spread to cover more surface area than those seeded on either of the FN-fragments (Table 7). Compared to intact FN, the mean cell lengths were reduced by 10 - 24% and the mean areas of cells on the three FN fragments were reduced by 28 - 39% for gingival fibroblasts. The corresponding reductions in cell length and area for HT1080 cells were even greater and ranged from 44 to 60% and 57 to 70%, respectively. Thus, the morphology was substantially altered for cells cultured on all FN fragments compared to intact FN.

Figure 3.

Effects of fibronectin fragments on cell morphology. Human gingival fibroblasts and HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells were seeded on full-length FN (Fibronectin), or on recombinant proteins corresponding to FN segments 1043 (r1043), 1177 (r1177), or I6I7 (rI6I7) as defined in Table 1. Surfaces were coated with proteins at their half-maximal attachment concentrations and non-specific sites blocked with heat inactivated BSA. Seeded cells were incubated for 12 h (shown here) prior to fixation, staining, and morphological analysis from digitized images (see results in Table 7). Photomicrographs were exposed at 200 × magnification and >100 cells were analyzed per condition.

Table 7.

Effects of full-length and defined fragments of FN on the morphology of human gingival fibroblasts and HT1080 cells

| Protein1 | Human gingival fibroblasts | HT1080 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length2 | Area3 | Length | Area | |

| FN | 106.4 (29.3) |

2160 (854) |

79.2 (32.7) |

1376 (1139) |

| r1043 | 80.8** (29.1) |

1549** (696) |

37.4** (9.5) |

531** (317) |

| r1177 | 86.8** (33.3) |

1313** (591) |

44.3** (16.5) |

589** (377) |

| rI6I7 | 95.2** (29.3) |

1467** (579) |

31.4** (13.5) |

416** (305) |

Proteins coated at concentrations yielding half-maximal cell attachment

Longest dimension of cells (μm; N>100)

Area of cells (μm7; N>100)

Presented are means and standard deviation (parentheses)

P<0.01 versus FN, NS between fragments (Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney);

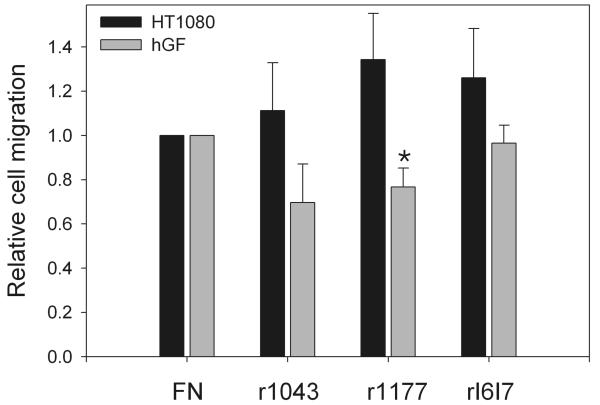

Cell migration

The migration of hGF on surfaces coated with r1043, r1177, or rI6I7 was clearly altered compared with intact FN (Fig. 4). The mean expansion of standard-sized hGF cell areas on r1043 or r1177 was reduced by 20 - 30% relative to cells on intact FN. In contrast, migration of hGF seeded on rI6I7 was the same as that of cells on intact FN. Contrary to hGF, HT1080 demonstrated a 15 to 25% increase in migration on all recombinant FN segments compared to that on intact FN (Fig. 4). Of note, a sample of FN which had degraded over an extended period of time of storage and therefore contained a large number of undefined fragments, induced a nearly 70% increase in mean migration area over that on intact FN (not shown). These experiments showed that three defined FN segments had substantial and different impacts on cell migration compared with intact FN.

Figure 4.

Cell migration on fibronectin fragments compared to full-length fibronectin. Human gingival fibroblasts (hGF) or HT1080 cells were seeded at 2 × 105 cells/ml into standard-sized wells on surfaces coated with full-length FN (FN) or recombinant fragments (r1043, r1177, rI6I7) and treated with BSA to block non-specific protein interactions. After attachment, cells expanded on surfaces in low serum medium allowing for migration but minimal proliferation. After 2 days, cells were fixed, stained, and the migration quantified by digital analysis and expressed relative to FN defined as 1. All experiments were in triplicate and repeated at least twice. Bars present means and standard error. Star denotes P<0.01 versus FN (Kruskal-Wallis and Mann Whitney).

DISCUSSION

The present series of experiments demonstrated that degradation of FN is a feature of both poorly healing diabetic foot and leg wounds and of sites with periodontal disease in patients with and without diabetes. Furthermore, our cell culture assays comparing the effects of intact FN and three recombinant well defined segments of FN provided further evidence that such fragments may significantly alter cellular behavior.

Unique to the present studies, we generated specific antibodies to mixed tryptic and chymotryptic FN fragments and the rI6I7 and r1043 FN segments for use in immunoblotting of chronic foot and leg wound fluid samples. Our results first confirmed the observation of FN fragmentation in diabetic wounds reported by Wysocki and Grinnell (1990)10. In addition, our quantification of fragment mass and frequency showed varying patterns of FN fragmentation in the samples. We did not consistently observe the 125 and 93 kDa FN fragments seen in the two patients examined by Wysocki and Grinnell (1990). Rather, in foot and leg wound fluids, we frequently detected 192, 188, 182, 166, 135 and 108 kDa fragments. Indeed, our samples from 22 diabetic patients revealed a great deal of variation in FN fragmentation between collected wound samples.

Cleavage of FN in periodontal disease was previously detected by Talonpoika et al (1989)16. These investigators proposed that the fragmentation resulted from proteolytic cleavage by plaque and P. gingivalis-derived proteases40. Periodontal treatment also was found to reduce the extent of FN degradation in the periodontal disease sites41. Later, Huynh et al. (2002) evaluated GCF among 94 systemically healthy (diabetes excluded) subjects with untreated periodontitis and samples collected from clinically healthy, mild to moderate, and severe periodontitis sites17. Using Western blotting and antibodies reactive for several discrete parts of FN, these investigators reported that 40, 68, and 120 kDa FN fragments were more frequently present in severe periodontal disease. Interestingly, our analyses detected a similarly-sized 125 kDa fragment in 3 of 5 diabetic periodontitis GCF samples. However, we did not detect the 125 kDa fragment in the non-diabetic periodontitis samples. Differences between the antibodies used in the different studies may well have lead to detection of different fragmentation patterns by different investigators. Of particular interest, our present results complement prior studies and for the first time have demonstrated that degradation of FN is a feature of periodontal disease in both systemically healthy and diabetic patients. Overall, it is reasonable to conclude that more studies remain essential to define whether specific FN fragments occurring in periodontal disease could be used for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes.

Wound healing involves regulated interactions between cells and the extracellular matrix environment. Integrin receptors mediate cell attachment to matrix molecules15, 42-44, and proteases, such as MMPs and other proteases classes facilitate localized detachment of cells from the matrix45. In this process, MMPs are transported to sites of cell-matrix adhesion, where they are activated locally to degrade the matrix molecules and release cells for locomotion45. Interestingly, upon proteolytic fragmentation, matrix molecules may be recognized by the same or other integrins and provide signals that can vary from those of the intact molecules. The proteolytic process may also expose cryptic binding sites on the matrix molecules for interaction with additional integrins, thereby inducing signaling events that are different from those occurring via integrins that positioned the cell on the intact molecules.1 Because cleavage of matrix molecules has the potential to induce altered cell behavior, an understanding of the molecular mechanisms of proteases and matrix degradation fragments is critical for deciphering cell behavior during wound healing.46

It was in the context of the developing understanding of altered cell behavior in the presence of FN fragments that we extended our studies to investigate the biological impact of the well-defined FN segments rI6I7, r1043, and r1177 relative to intact, full-length FN. We found that two regions of FN located outside the classical RGD-containing cell binding site initially described by Ruoslahti and Pierschbacher (1986)47 supported cell attachment although neither contains an RGD sequence. These alternative cell binding sites are in rI6I7, which extends from G27 at the N-terminus of the 6th type I repeat to A47 at the C-terminus of the 7th type I repeat, and in r1043, which includes E104 at the C-terminus of the 5th type III repeat to R140 at the C-terminus of the 9th type III repeat. It is noteworthy that the concentrations of these FN fragments required to reach 50%-maximal cell attachment were substantially higher (by 85 to 280 times) compared to intact FN. That cell spreading on these shorter FN fragments, reflected by cell area and length, was reduced agrees with observations by others who found that cells can attach to peptides as small as the RGDX peptide whereas spreading requires a heparin binding site.48 Furthermore, PHSRN, an amino acid sequence which is located in the 9th type III repeat and forming another cell binding region of FN, interacts with the RGD sequence in the 10th type III repeat leading to increased α5β1 integrin attachment.49

FN and FN fragments are important for tissue and cell type-specific control of MMP expression in tissues. For example, a 120 kDa FN fragment containing the cell-binding domain induced PDL cells to express collagenase and stromelysin, increased secretion of the serine proteinase uPA, and promoted expression of a 20 kDa MMP inhibitor.20 In those studies, 60 kDa heparin-binding and 45 kDa collagen-binding FN fragments did not produce similar responses in PDL cells.20 In comparison, a FN fragment containing the C-terminal heparin-binding domain stimulated type II collagen degradation in bovine articular cartilage by inducing collagenase, proMMP-13 and proMMP-3,50 and FN fragments of 29-, 50-, and 140-kDa caused a 25- to 120-fold enhanced stromelysin-1 release when added to bovine articular cartilage.51 MMP-1 production was induced by a recombinant extra domain-A FN fragment in rabbit cartilage explant cultures and chondrocytes,52 likely through expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1α and IL-1β. A 90 kDa FN fragment was expressed by human retinal endothelial cells of diabetic and non-diabetic origin after exposure to glucose.53 This FN fragment was strongly attached to MMP-2 and inhibited MMP-2 autoactivation.

In light of the close interplay between FN fragments and MMP activities, it may be important that wounds in people with poorly controlled diabetes exhibit impeded healing and that poorly healing diabetic wounds have persistently elevated MMP levels, decreased TIMP expression, or both54. FN is sensitive to proteolysis. It was early recognized that FN could be cleaved by plasmin55, 56, trypsin, thrombin, thermolysin, chymotrypsin, cathepsin D, pronase, cyanide,57 elastase, cathepsin G from neutrophils, and mast cell chymase58. Reviews of MMP substrate specificities have revealed that FN is also readily degraded by a series of MMPs including MMPs-2, -3, -4, -7, -10, -11, -12, -13, -14, and -1514, 15, 59. On this basis, it is very plausible that the elevated levels of MMPs in both diabetic wounds and periodontal disease sites may be an important source of enzyme in the proteolytic attack on FN. Please see available reviews for further information on FN and MMPs in normal and diabetic wound healing15, 43, 44, 46, 60-63.

It is interesting that MMP levels also are increased in fluids collected from periodontal disease sites64. A common thought is that the chronic bacterial challenge induces immune reactions that result in release of MMPs from inflammatory cells65. Thus, the question arose: If FN fragmentation occurs both in the periodontal and chronic leg wound, are there similar mechanisms which govern the pathogenesis and healing for both types of wounds?

Results from this study did in fact detect FN fragments of similar sizes in fluids from both periodontal and chronic diabetic leg wounds which were reactive to antibodies specific against portions of the FN molecule included in our constructs r1043 and rI6I7. While we did not analyze the specific amino acid sequences of these proteins, the size and antibody reactivity suggest they could be FN fragments generated from cleavage of FN by similar enzymes in the two different wound types.

Our analyses also showed that recombinant protein segments from the FN molecule induced changes in human gingival fibroblast behaviors of attachment, morphology, and migration. It is known that acetylation and amidation of the PHSRN sequence in the 9th type III module described above, increases keratinocyte and fibroblast cell invasion of sea urchin embryos, and that this peptide has greater activity on a molar basis than the 120 kDa proteolytically-generated cell-binding domain.49 Since the PHSRN sequence is present in both the r1043 and r1177 FN fragments utilized in our experiments, it is possible that this recognition site contributed to the modified migration noted on our FN fragments. The fact that 1043 also contains a portion of the heparin binding region may further explain the decrease in migration we found among gingival fibroblasts cultured on that FN fragment. This observation in consistent with the results from experiments using a 60 kDa proteolytic, as well as 120 kDa cell-binding and 45 kDa collagen-binding fragments that had reduced chemotactic effects on periodontal ligament cells than intact FN.66 It is noteworthy that fibrosarcoma cancer HT1080 cells behaved differently than hGF cells in migration assays pointing to different effects of FN fragments in cancer and normal tissues

In summary, our results have demonstrated that FN fragmentation is a feature of both leg wounds and periodontal disease sites in diabetes. Our analyses concluded that the behavior of periodontal cells is altered in response to contact with fibronectin fragments compared to intact FN. Since FN is cleaved by several enzymes, including several MMPs, novel strategies for wound healing management should be considered. It is possible that targeted inhibition of FN cleavage by locally- or systemically-administered MMP-inhibitors could promote normal healing and tissue maintenance in chronic leg wounds and periodontal disease sites in patients with diabetes.

Acknowledgments

This research was only possible with generous contributions to identification of patients by Dr. Kathleen Satterfield, Dr. John Steinberg, and Dr. Patricia Smith at the Texas Diabetes Institute, San Antonio, Texas. Supported by grants DE12818, DE14236, DE17139, DE016312 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, and South Texas Health Research Center, San Antonio, Texas.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and are not to be construed as official nor as reflecting the views of the United States Air Force or Department of Defense

Conflict of interests: None of the investigators report any financial relationships to any product or sponsor involved in this study

Pierce, Rockford, IL

Alpha Diagnostics International, San Antonio, TX

Amersham-Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ

Immobilon-P; Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA

Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA

Pierce, Rockford, IL

BioMax, Kodak, Rochester, NY

DC120 Camera, K1D software, Kodak, Rochester, NY

Gibco, Rockville, MA

HiLoad 16/60 Superdex, Amersham-Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ

UTHSCSA Core facility for Advanced DNA Technologies

UTHSCSA Mass Spectrometry Laboratory

Sigma, St. Louis, MO

ATCC, Rockville, Manasas, VA

Opsys MR, Dynex Technologies, Chantilly, VA

Corning Inc., Acton, MA

OptiMEM, Gibco, Rockville, MA

Vanox-T Olympus, Olympus, Melville, NY

Image Pro Plus, Media Cybernetics, Silver Springs, MD

Thermanox, NUNC™ Brand Products, Rochester, NY

Summary: The experiments characterized fibronectin degradation in periodontal disease and diabetic leg and foot wounds and demonstrated that the fibronectin fragments modified cell behavior in a manner that could affect both pathogenesis and wound healing

REFERENCES

- 1.Giannelli G, Falk-Marzillier J, Schiraldi O, Stetler-Stevenson WG, Quaranta V. Induction of cell migration by matrix metalloproteinase-2 cleavage of laminin-5. Science. 1997;277:225–228. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koshikawa N, Giannelli G, Cirulli V, Miyazaki K, Quaranta V. Role of cell surface metalloprotease MT1-MMP in epithelial cell migration over laminin-5. Journal of Cell Biology. 2000;148:615–624. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.3.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pilcher BK, Duman JA, Sudbeck BD, Krane SM, Welgus HG, Parks WC. The activity of collagenase-1 is required for keratinocyte migration on a type I collagen matrix. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1445–1457. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.6.1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu X, Wang Y, Chen Z, Sternlicht MD, Hidalgo M, Steffensen B. MMP-2 contributes to cancer cell migration on collagen. Cancer Res. 2005;65:130–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klebe RJ. Isolation of a collagen-dependent cell attachment factor. Nature. 1974;250:248–251. doi: 10.1038/250248a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hynes RO. Fibronectins. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1990. Interactions of fibronectin; pp. 84–112. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamada KM, Kennedy DW. Fibroblast cellular and plasma fibronectins are similar but not identical. J Cell Biol. 1979;80:492–498. doi: 10.1083/jcb.80.2.492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magnuson VL, Young M, Schattenberg DG, et al. The alternative splicing of fibronectin pre-mRNA is altered during aging and in response to growth factors. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:14654–14662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steffensen B, Magnuson VL, Potempa C, Chen D, Klebe RJ. α5 Integrin subunit expression changes during myogenesis. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1992;1137:95–100. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(92)90105-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wysocki AB, Grinnell F. Fibronectin profiles in normal and chronic wound fluid. Lab Invest. 1990;63:825–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grinnell F, Ho C-H, Wysocki AB. Degradation of fibronectin and vitronectin in chronic wound fluid: Analysis by cell blotting, immunoblotting, and cell adhesion assays. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;98:410–416. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12499839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grinnell F, Zhu M. Fibronectin degradation in chronic wounds depends on the relative levels of elastase, α1-proteinase inhibitor, and α2-macroglobulin. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:335–341. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12342990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wysocki AB, Stalano-Coico L, Grinnell F. Wound fluid from chronic leg ulcers contains elevated levels of metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101:64–68. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12359590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Birkedal-Hansen H, Moore WGI, Bodden MK, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases: A review. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1993;4:197–250. doi: 10.1177/10454411930040020401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steffensen B, Hakkinen L, Larjava H. Proteolytic events of wound healing - coordinated interactions between matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), integrins, and extracellular matrix molecules. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2001;12:373–398. doi: 10.1177/10454411010120050201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Talonpoika J, Heino J, Larjava H, Hakkinen L, Paunio K. Gingival crevicular fluid fibronectin degradation in periodontal health and disease. Scand J Dent Res. 1989;97:415–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1989.tb01455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huynh QH, Wang SH, Tafolla E, et al. Specific fibronectin fragments as markers of periodontal disease status. J Periodontol. 2002;73:1101–1110. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.10.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Werb Z, Tremble PM, Behrendtsen O, Crowley E, Damsky CH. Signal transduction through the fibronectin receptor induces collagenase and stromelysin gene expression. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:877–889. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.2.877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huhtala P, Humphries MJ, McCarthy JB, Tremble PM, Werb Z, Damsky CH. Cooperative signaling by alpha 5 beta 1 and alpha 4 beta 1 integrins regulates metalloproteinase gene expression in fibroblasts adhering to fibronectin. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:867–879. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.3.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kapila YL, Kapila S, Johnson PW. Fibronectin and fibronectin fragments modulate the expression of proteinases and proteinase inhibitors in human periodontal ligament cells. Matrix Biol. 1996;15:251–261. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(96)90116-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Homandberg GA, Meyers R, Xie D-L. Fibronectin fragments cause chondrolysis of bovine articular cartilage slices in culture. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:3597–3604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stanton H, Gavrilovic J, Atkinson SJ, et al. The activation of proMMP-2 (gelatinase A) by HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells is promoted by culture on a fibronectin substrate and is concomitant with an increase in processing of MT1-MMP (MMP-14) to a 45 kDA form. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:2789–2798. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.18.2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steffensen B, Xu X, Martin P, Zardeneta G. Human fibronectin and MMP-2 collagen binding domains compete for collagen binding sites and modify cellular activation of MMP-2. Matrix Biol. 2002;21:399–414. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(02)00032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kapila YL, Wang S, Johnson PW. Mutations in the heparin binding domain of fibronectin in cooperation with the V region induce decreases in pp125FAK levels plus proteoglycan-mediated apoptosis via caspases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30906–30913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Planchenault T, Lambert VS, Imhoff JM, et al. Potential proteolytic activity of human plasma fibronectin: Fibronectin gelatinase. Biol Chem. 1990;371:117–128. doi: 10.1515/bchm3.1990.371.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keil-Dlouha V, Planchenault T. Potential proteolytic activity of human plasma fibronectin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:5377–5381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.15.5377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schei O, Waerhaug J, Lovdal A, Arno A. Alveolar bone loss as related to oral hygiene and age. J Periodontol. 1959;30:7–16. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Engvall E, Roushlahti E. Binding of soluble form of fibroblast surface protein, fibronectin, to collagen. Int J Cancer. 1977;20:1–5. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910200102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hermanson GT, Krishna Mallia A, Smith PK. Immobilized affinity ligand techniques. Academic Press; London: 1992. Immobilization of enzymes; pp. 202–10. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steffensen B, Wallon UM, Overall CM. Extracellular matrix binding properties of recombinant fibronectin type II-like modules of human 72-kDa gelatinase/type IV collagenase. High affinity binding to native type I collagen but not native type IV collagen. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11555–11566. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Engvall E, Bell ML, Ruoslahti E. Affinity chromatography of collagen on collagen-binding fragments of fibronectin. Coll Relat Res. 1981;1:505–516. doi: 10.1016/s0174-173x(81)80032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steffensen B, Bigg HF, Overall CM. The involvement of the fibronectin type II-like modules of human gelatinase A in cell surface localization and activation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20622–20628. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kornblihtt AR, Umezawa K, Vibe-Pedersen K, Baralle FE. Primary structure of human fibronectin: differential splicing may generate at least 10 polypeptides from a single gene. The EMBO Journal. 1985;4:1755–1759. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skorstengaard K, Holtet TL, Etzerodt M, Thogersen HC. Collagen-binding recombinant fibronectin fragments containing type II domains. FEBS Lett. 1994;343:47–50. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80604-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinum thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guillemette JG, Matsushima-Hibiya Y, Atkinson T, Smith M. Expression in E. coli of a synthetic gene coding for horse heart myoglobin. Protein Engng. 1991;4:585–592. doi: 10.1093/protein/4.5.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eltis LD, Iwagami SG, Smith M. Hyperexpression of a synthetic gene encoding a high potential iron sulfur protein. Protein Eng. 1994;7:1145–1150. doi: 10.1093/protein/7.9.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oates TW, Hoang AM. Periodontal ligaments. In: Koller MR, Palsson BO, Masters JRW, editors. Human cell culture. V. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Amsterdam: 2001. pp. 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Larjava H, Uitto V-J, Haapasalo M, Heino J, Vuento M. Fibronectin fragmentation induced by dental plaque and Bacteroides gingivalis. Scand J Dent Res. 1987;95:308–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1987.tb01846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Talonpoika J, Paunio K, Soderling E. Molecular forms and concentration of fibronectin and fibrin in human gingival crevicular fluid before and after periodontal treatment. Scand J Dent Res. 1993;101:375–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1993.tb01135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Danen EH, Sonnenberg A. Integrins in regulation of tissue development and function. J Pathol. 2003;201:632–641. doi: 10.1002/path.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singer AJ, Clark RA. Cutaneous wound healing. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:738–746. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clark, RAF. The Molecular and Cellular Biology of Wound Repair. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 1996. pp. 311–338. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Basbaum CB, Werb Z. Focalized proteolysis: Spatial and temporal regulation of extracellular matrix degradation at the cell surface. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:731–738. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kahari VM, Saarialho-Kere U. Matrix metalloproteinases in skin. Exp Dermatol. 1997;6:199–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.1997.tb00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruoslahti E, Pierschbacher MD. Arg-Gly-Asp: a versatile cell recognition signal. Cell. 1986;44:517–518. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90259-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woods A, Couchman JR, Johansson S, Hook M. Adhesion and cytoskeletal organisation of fibroblasts in response to fibronectin fragments. EMBO J. 1986;5:665–670. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Livant DL, Brabec RK, Kurachi K, et al. The PHSRN sequence induces extracellular matrix invasion and accelerates wound healing in obese diabetic mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1537–1545. doi: 10.1172/JCI8527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yasuda T, Poole AR. A fibronectin fragment induces type II collagen degradation by collagenase through an interleukin-1-mediated pathway. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:138–148. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200201)46:1<138::AID-ART10051>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xie DL, Hui F, Meyers R, Homandberg GA. Cartilage chondrolysis by fibronectin fragments is associated with release of several proteinases: stromelysin plays a major role in chondrolysis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;311:205–212. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saito S, Yamaji N, Yasunaga K, et al. The fibronectin extra domain A activates matrix metalloproteinase gene expression by an interleukin-1-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30756–30763. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grant MB, Caballero S, Bush DM, Spoerri PE. Fibronectin fragments modulate human retinal capillary cell proliferation and migration. Diabetes. 1998;47:1335–1340. doi: 10.2337/diab.47.8.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vaalamo M, Weckroth M, Puolakkainen P, et al. Patterns of matrix metalloproteinase and TIMP-1 expression in chronic and normally healing human cutaneous wounds. Brit J Derm. 1996;135:52–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jilek F, Hormann H. Cold-insoluble globulin, II. Plasminolysis of cold-insoluble globulin. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol Chem. 1977;358:133–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen AB, Amrani DL, Mosesson MW. Heterogeneity of the cold-insoluble globulin of human plasma (CIg), a circulating cell surface protein. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977;493:310–322. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(77)90187-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hynes RO. Fibronectins. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1990. Structures of Fibronectins; pp. 113–75. [Google Scholar]

- 58.McDonald J. Fibronectin in the lung. In: Mosher D, editor. Fibronectin. Academic Press, Inc.; San Diego: 1989. pp. 363–93. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Somerville RP, Oblander SA, Apte SS. Matrix metalloproteinases: old dogs with new tricks. Genome Biol. 2003;4:216. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-6-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grinnell F. Fibronectin and wound healing. Am J Dermatopathol. 1982;4:185–188. doi: 10.1097/00000372-198204000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Saarialho-Kere U. Patterns of matrix metalloproteinase and TIMP expression in chronic ulcers. Arch Dermatol Res. 1998;290(Suppl):S47–S54. doi: 10.1007/pl00007453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Homandberg GA. Potential regulation of cartilage metabolism in osteoarthritis by fibronectin fragments. Front Biosci. 1999;4:D713–D730. doi: 10.2741/homandberg. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barilla ML, Carsons SE. Fibronectin fragments and their role in inflammatory arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2000;29:252–265. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(00)80012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ryan ME, Ramamurthy NS, Sorsa T, Golub LM. MMP-mediated events in diabetes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;878:311–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sorsa T, Ding Y, Salo T, Lauhio A, Teronen O, Ingman T, Ohtani H, Andoh N, Takeha S, Konttinen YT. Effects of tetracyclines on neutrophil, gingival, and salivary collagenases. A functional and western-blot assessment with special reference to their cellular sources in periodontal diseases. In: Greenwald RA, Golub LM, editors. Inhibition of Matrix Metalloproteinases. Therapeutic potential. Vol. 732. The New York Academy of Sciences; New York: 1994. pp. 112–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kapila YL, Lancero H, Johnson PW. The response of periodontal ligament cells to fibronectin. J Periodontol. 1998;69:1008–1019. doi: 10.1902/jop.1998.69.9.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]