Abstract

Objectives

Cigarette smoke exposure is a significant risk factor in the development of otitis media (OM). Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) is a ubiquitous transcription factor known to mediate cigarette smoke effects on gene regulation in multiple cell types. The MUC5B mucin gene contains several putative NF-κB sites in its promoter and is the predominant mucin expressed in human OM. We hypothesized that in vitro stimulation of a recently developed model system, murine middle ear epithelial cells (MEEC), with cigarette smoke condensate (CSC) activates NF-κB and subsequently induces Muc5b gene expression.

Methods

Luciferase reporter assays, electromobility shift assays (EMSA), and quantitative microplate transcription factor assays (TFA) were performed to evaluate NF-κB activation with CSC in immortalized murine MEEC (mMEEC). Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays and quantitative real time RT-PCR were performed to determine whether time course CSC stimulation upregulates Muc5b mRNA levels in differentiated mMEEC. Luciferase reporter assays were performed to determine whether CSC activates the Muc5b promoter.

Results

Reporter assays, EMSA, and TFA demonstrated three- to five-fold dose-dependent activation of NF-κB with CSC in mMEEC. CSC stimulation likewise increased Muc5b mRNA abundance and induced reporter activity 1.8- to 4.8-fold in plasmids containing −556 and −255 base pairs upstream of the Muc5b transcriptional start site in mMEEC.

Conclusions

CSC activates NF-κB in immortalized MEEC. Furthermore, this activation correlates with CSC-induced Muc5b promoter activation and gene expression. Taken together, these results hint that much as in lung cells, the activation of mucins by cigarette smoke is mediated in part by NF-κB.

Keywords: Muc5b, mouse middle ear epithelial cells, NF-kappaB, cigarette smoke condensate

INTRODUCTION

Otitis Media (OM) is a ubiquitous condition of early childhood accounting for 16 million physician office visits a year1 at a national cost of 3 to 6 billion dollars.2 Exposure to tobacco smoke in children has been shown to be a significant risk factor in the development of OM. Links between environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) and OM have been promulgated by various federal agency reports: the Surgeon General,3 the National Research Council,4 the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA),5 and the National Cancer Institute (NCI)/California EPA.6 Other environmental and genetic risk factors, such as day care and family history of OM, are associated with middle ear disease in childhood.7–10 In the presence of smoke exposure, the combined interaction of factors may mean the difference in becoming otitis-prone or not.11 Despite strong casual epidemiologic data, direct mechanisms by which cigarette smoke exposure contributes to middle ear pathology are significantly under-investigated.

Multiple genes increased in inflammatory disease states are regulated by NF-κB, a ubiquitous deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA)-binding transcription factor.12 Likewise, NF-κB is a known mediator of cigarette smoke effects on gene regulation in many cell types.13–15 Its activated form has been shown to be increased in bronchial biopsies of smokers.16 In rabbit middle ear epithelial cells, NF-κB has been identified as a key intracellular modulator of chronic inflammation.17 In cancer cells, it is known to directly up-regulate mucin gene expression through promoter interactions.18

Epithelial cells that encompass mucosal surfaces are increasingly recognized as the first line of defense against infectious or environmentally harmful stimuli, including cigarette smoke. First-line innate immune responses occur at the epithelial mucosal surface.19–21 As part of these epithelial defense mechanisms, mucin glycoproteins act as physiologic barriers to contaminants and bacteria by forming mucus, a viscoelastic gel. To date, 18 human mucin (MUC) genes have been identified (reviewed by Rose and Voynow22). These genes encode gene products that are classified as secretory mucins, of which MUC2, MUC5AC, and MUC5B are the best studied, and membrane-tethered mucins, of which MUC1 and MUC4 are presently the best investigated. Within the confines of the middle ear, mucin over-production and the resulting mucous obstruction or stagnation clearly contributes to OM pathology.23 Although MUC5AC and MUC5B are the primary mucins in respiratory secretions, MUC5B appears to be the predominant mucin involved in human otitis media.24–28 However, very little work has evaluated MUC5B mRNA expression in animal and/or cell models of OM. This is likely due to the fact that cellular models of MEEC have only recently been established and that the mouse Muc5b gene was only recently cloned.29,30 Much like the human MUC5B gene, the mouse Muc5b promoter contains several putative NF-κB sites.

For this study, we hypothesized first that in vitro stimulation of murine MEEC (mMEEC) with the particulate fraction of cigarette smoke (cigarette smoke condensate; CSC) activates NF-κB, and second, that this activation results in increased Muc5b expression in mMMEC.

METHODS

Cell Lines

The mouse middle ear epithelial cell line mMEEC was immortalized by temperature-sensitive simian virus 40 (SV40), allowing for a proliferative phenotype at 33°C and for differentiation at 37°C.31 mMEEC were maintained in full growth medium (FGM), which is comprised by Ham’s F-12 K culture medium supplemented with 1.5 g/l sodium bicarbonate, 2.0 mmol/L L-glutamine, 10 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (EGF; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), 10 mg/mL insulin_/transferrin_/sodium selenite (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 2.7 g/l glucose, 500 ng/mL hydrocortisone, 0.1 mmol/L logicessential amino acids and 4% fetal bovine serum. The cells were grown and passaged at 33°C in a 5% carbon dioxide (CO2)-humidified atmosphere. Prior to experimentation, cells were transferred to a 37°C, 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere to inactivate the SV-40 virus. Cells were then grown on plastic or on Transwells (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) submerged in FGM until they achieved confluence. At that point, they were placed at an air liquid interface (ALI) for 14 days, with FGM being supplied only to the basal side of the cells. These ALI conditions have been reported to further differentiate middle ear cells, with diffuse formation of goblet cells, mimicking in vivo OM metaplastic epithelium.32

CSC was purchased from Murty Pharmaceuticals (Lexington, KY) where it was prepared using a Phipps-Bird 20-channel smoking machine (Phipps & Bird, Inc., Richmond, VA). The particulate matter from Kentucky standard cigarettes (1R3F; University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY) was collected on Cambridge glass fiber filters (Cambridge Filter Corporation, Gilbert, AZ), and the amount obtained determined by weight increase of the filter. CSC was prepared by dissolving the collected smoke particulates in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to yield a 4% solution (w/v). The average yield of CSC was 26.1 mg/cigarette. The CSC was diluted into DMSO, and aliquots were kept at −80°C. CSC concentrations of 0 to 40 μg/mL total particulate matter (TPM) stimulate cytokine secretion in cultured endothelial cells.33 Secondhand smoke has been shown to have concentrations estimated to be in the range of this experimental dosage.34

Preparation of Nuclear Extracts

Cells were grown in 75-cm2 flasks to 60% to 80% confluence and then stimulated with 10, 20, or 40 μg/mL of CSC in DMSO or plain DMSO for 60 minutes. Cell suspensions were prepared by Trypsin-EDTA treatment, and the cells were washed twice in cold phosphate-buffered saline and pelleted at 500 × g. Cytoplasmic and nuclear protein extraction was then performed using a kit from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Briefly, the cell pellets were lyzed with cytoplasmic extract reagent I and proteinase inhibitor on ice for 10 minutes. After adding cytoplasmic extract reagent II, the lysates were microfuged for 5 minute at 16,000×G. The supernatant was collected and saved as cytoplasmic extract at −80°C. The nuclear pellet was then resuspended in nuclear extract reagent and proteinase inhibitor, incubated on ice for 40 minutes, and then microfuged at 15,000×G for 10 minutes. The remaining nuclear extracts were aliquoted and stored at −80°C. The protein concentrations of the extracts were determined in triplicate by using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) modification of the biuret reaction (Pierce Protein Assay Kit, Pierce, Rockford, IL) scaled for microtiter plate analysis. BSA was used as a standard, and the plates were read at 580 nm on a BioTek 311 microtiter plate reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT). Standard curves were generated using computer software. The correlation coefficients for the functions were greater than 0.95 in all experiments.

Chemiluminescent Transcription Factor Microplate Assay (TFA)

NF-κB chemiluminescent transcription factor assays (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) were performed per the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the nuclear extract samples were thawed and mixed with a double stranded biotinylated oligonucleotide containing the flanked consensus sequence for NF-κB binding (5′-GGGACTTTCC-3′). Cold competition was performed in some groups by including provided unlabeled NF-κB competitor oligonucleotide probes in the binding reaction. TNF-α treated HeLa whole-cell extracts were used as a positive control. Sample nuclear extracts without NF-κB capture probes in the binding reaction served as negative controls. The binding reactions were allowed to sit at room temperature for 1 hour prior to loading them onto a provided 96-well chemiluminescent plate coated with streptavidin. After a 1-hour incubation, the wells were washed three times with 1× enhanced transcription factor assay buffer and incubated at room temperature with 100 μL of 1:1000 diluted antiNF-κB p65 antibody. After washing, the sample wells were incubated with 1:1000 diluted rabbit IgG-HRP conjugated secondary antibody for 30 minutes. After washing off unbound secondary antibody, chemiluminescent development was performed by adding chemiluminescent detection reagent in chemiluminescent reaction buffer at room temperature for 5 minutes. The absorbance was measured in a microplate luminometer.

Electromobility Shift Assays (EMSA)

A supply of 5′ and 3′ biotinylated labeled and unlabeled oligonucleotides of the NF-κB consensus sequence 5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGG-3′ was obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA) and annealed to an unlabeled complementary oligonucleotide to generate double-stranded probes for logicradioactive, chemiluminescent EMSA. Nuclear extracts (3μg) were equilibrated in binding buffer [10 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.5; 1 mmol/L DTT, 2.5% glycerol, 5 mmol/L MgCl2, 50 mmol/L KCl, 0.05% NP-40, 0.05 μg/ul poly (dI:dC)-(dI:dC) (Pierce, Rockland, IL) with unlabeled double-stranded oligonucleotide probes (5 pm) in some samples for 15 minutes at room temperature. Double-stranded biotinylated probe (20 fm) was then added to all samples and incubated for an additional 20 minutes at room temperature. Nuclear extracts from 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) + calcium ionophore (CI) stimulated Jurkat cells (Active Motif; Carlsbad, CA) served as a positive control. Samples were loaded onto 6% polyacrylamide gel and run in 0.5× TBE at 4°C. The binding reactions were then transferred from the gel to a presoaked nylon membrane (Ambion, Austin, TX) with a semidry electroblotting transfer unit (Owl Scientific, Woburn, MA). The transferred DNA was cross-linked to the membrane using an ultraviolet-light cross linker at 120 mJ/cm2 for 60 seconds. The membrane was developed for chemiluminescent detection with a kit from Pierce (Rockland, IL). Briefly, the membrane was first blocked with blocking buffer prior to adding stabilized streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate. After washing four times, the membrane was equilibrated with substrate equilibration buffer prior to adding luminol enhancer solution in stable peroxide. The membrane was exposed and visualized with a CCD camera equipped Gel Doc 2000 chemiluminescent imaging documentation station (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Construction of Murine Muc5B Luciferase Reporter Plasmids

The promoter sequence for Muc5B was identified on Gen-Bank as accession number AY744445. The following primers tagged with 5′ restriction enzyme sequences were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA): −556 F5′-CAGGAGCCCAGAGACTCATC-3′; −359 F5′-ACAAGCCAAG-GTTGTTGTCC-3′; −255 F5′-GGCTTCGAATCCAGAGTAG-3′; and +23 R5′-GCAGGAGGGACTGAGACAAG-3′ (Xho1 restriction sites on the F primers’ 5′ end, and Bgl1 restriction site on the R primer 5′ end). PCR was performed using these primers and mouse liver genomic DNA extract as template. After purification, resulting products were restricted and ligated to the PGL4 vector (Promega, Madison, WI). After confirmation of the nucleotide sequences, the plasmids were then transformed in competent DH5′ cells and amplified with MaxiPrep kits (Promega, Madison, WI).

Transient Transfection and Luciferase Assays

The pIgκB Luc reporter construct containing three immunoglobulin G-κ chain NF-κB binding sites upstream of the luciferase gene has been previously described35 and was generously provided by Frank Ondrey MD, PhD, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota. This NF-κB reporter plasmid and the Muc5b promoter plasmids were transiently transfected into mMEEC cells for luciferase assays as follows. Cell line cultures at 70% confluence were co-transfected with the luciferase plasmids (2 μg/mL) and a pCMV-βGal reporter construct (0.4 μg/mL) (Clontech, Mountainview, CA) in Opti-MEM medium containing 3 μg/mL of lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After 6 hours, the medium was removed, and the cells were placed in FGM. The next day, the cells were treated with CSC at 10, 20, and 40 μg/mL in DMSO, or plain DMSO for 8 hours. After stimulation, the relative luciferase activity was determined with the dual light reporter gene assay (Tropix, Medford, MA) and a Monolight 2010 plate luminometer (Analytical Luminescence Laboratories, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Results for relative luciferase units (RLU) were determined as a ratio of the luciferase constructs over the pCMV-βGal reporter to normalize for harvesting efficiency.

RT-PCR and Real Time RT-PCR Analyses of Muc5b Gene Expression

For experiments of mucin gene expression, the cells were grown under conditions allowing for further differentiation and goblet cell formation.32 Briefly, mMEEC were grown on transwells submerged in FGM until they achieved confluence. At that point, they were placed at an air liquid interface (ALI) for 14 days, with FGM being supplied only to the basal side of the cells. Ribonucleic acid (RNA) was extracted from these differentiated mMEEC cells exposed to CSC (10, 20, 40 μg/mL) or vehicle for 2, 8, and 24 hours using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). RNA was precipitated with isopropyl alcohol, washed and dissolved in RNase-free water. Reverse transcription reaction was then performed by using 1 μg of total RNA from each sample with 10 mmol/L dNTPs, an 50 μmol/L oligo(dT) and heating this mixture to 65°C for 5 minutes, followed by a 1-minute ice incubation. Then, 200 units of SuperScript III reverse transcriptase enzyme (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 40 units of RNaseOUT, 0.1 mol/L DTT, and 5× first-strand buffer were then added to the mixture and the reaction was incubated at 50°C for 60 minutes. The reaction was then inactivated at 70°C for 15 minutes. At that point, cDNA was used for PCR, using specific pairs of primers as follows: Muc5b forward primer, 5′-ACTTGAGGAGGGTTCCAGGT-3′; Muc5b reverse primer, 5′-ACAGTGCCAGGGTTTATGC-3′ (accession number AJ311906). As an internal control, β-actin was used, and primers for mouse β-actin were obtained from GeneLink (Hawthorne, NY). Muc5b and β-actin PCR product sizes are 307 and 349 bp respectively. PCR reactions were carried out in 50-μL solutions, including 45 μL of PCR Supermix (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 2 μL of cDNA, and 1.5 μL each of 10 μmol/L forward and reverse Muc5b and β-actin primers. PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on a 2% in 1× TAE agarose gel containing 50 nglml ethidium bromide and were visualized with a Gel Doc 2000 gel imaging documentation station (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Real-time RT-PCR was performed on the generated cDNA products in the ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using the power SYBR green PCR master mix from Applied Biosystems (Branchburg, NJ) with the same primers as described above. β-actin was unchanged by CSC exposure and was used as an internal control for normalizing Muc5b mRNA levels in control and experimental samples. Dilution curves confirmed the linear dependence of the threshold cycles on the concentration of template RNA samples. Relative quantification of Muc5b mRNA in control and experimental samples was obtained using the standard curve method.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical difference between experimental and control groups for all experiments was determined by two-tailed Student t tests. Significance level was set at P < .05.

RESULTS

CSC Increases NF-κB Activity in mMEEC

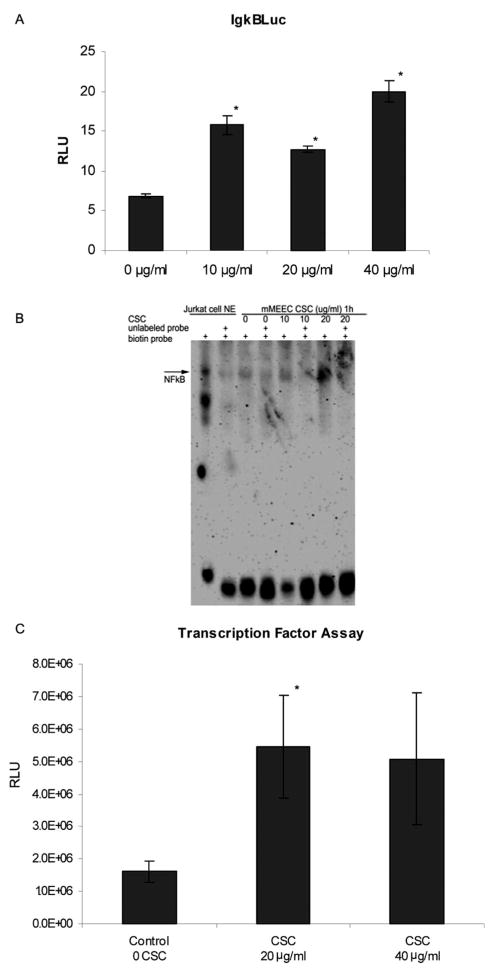

NF-κB is a mediator of cigarette smoke effects in multiple epithelial cell types.13–15 To elucidate whether this is also the case in mouse ear epithelium, we performed reporter assays, EMSA, and chemiluminescent NF-κB TFA as three complementary means to determine whether CSC activates NF-κB in mMEEC. Reporter gene assays demonstrated statistically significant 2.3, 1.85, and 2.9 increases in activity of the pIgκB Luc plasmid relative to β-gal in mMEEC with 10, 20, and 40 μg/mL of CSC, respectively (Fig 1A). EMSA demonstrated increased presence of NF-κB in nuclear extracts from mMEEC stimulated with 20 μg/mL CSC for 1 hour (Fig. 1B). This result correlated with quantitative chemiluminescent NF-κB TFA results demonstrating that nuclear extracts from mMEEC treated with 20 μg/mL CSC contain a statistically significant increase in NF-κB protein that is capable binding of its consensus oligonucleotide sequence when compared to cells treated with plain DMSO (Fig 1C). Similarly, at the 40 μg/mL dose of CSC there was also increased binding noted, but this did not reach statistical significance (P < .08). Taken together, the results shown in Figure 1 qualitatively and quantitatively demonstrate that CSC at 20 μg/mL caused nuclear translocation of activated NF-κB and that CSC at 10, 20, and 40 μg/mL functionally activated transfected NF-κB reporter plasmids in mMEEC.

Fig. 1.

Cigarette smoke condensate (CSC) increases nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activity in murine middle ear epithelial cells (mMEEC). (A) Luciferase assay results with the pIgκB Luc reporter construct42 activity normalized to β-gal activity demonstrate significant increases in functional NF-κB activity with CSC (*all P < .05). (B) Electromobility shift assays (EMSA) demonstrate increased binding of an NF-κB consensus oligonucleotide binding complex with nuclear extracts from mMEEC treated with 20 μg/mL CSC. (C) Chemiluminescent transcription factor assays quantitatively demonstrate statistically significant increases in nuclear NF-κB with 20 μg/mL CSC (*P = .03).

CSC Increases Expression of Muc5b in a Primary Immortalized Murine Middle Ear Cell Line Grown Under Differentiating Conditions

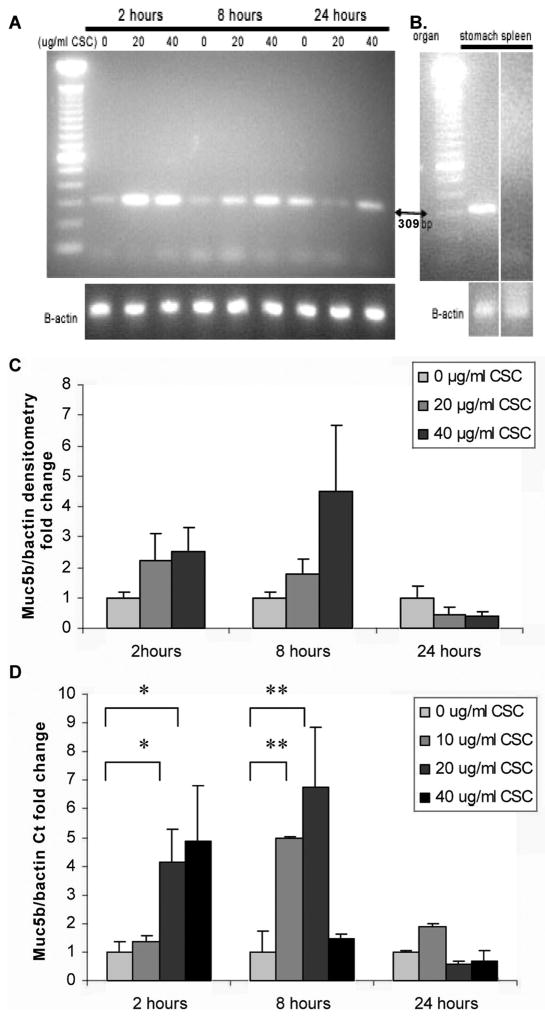

For these experiments, Muc5b expression was evaluated both in mMEEC cells grown on plastic at 37°C and under conditions where they had been reported to differentiate.32 Reverse transcriptase- polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) data indicated low levels of Muc5b mRNA expression in undifferentiated cells, and CSC did not alter Muc5b mRNA levels in mMEEC cells grown submerged on plastic (data not shown). Given the reported lack of goblet cells in MEEC grown on plastic,31,32 this finding was expected. To confirm ALI induced differentiation of the mMEEC, in separate experiments periodic acid schiff (PAS) was performed after 14 days of ALI on Transwell membranes (Corning Inc.). We observed PAS staining in goblet cells, whereas no PAS staining was observed in mMEEC cells grown under submerged conditions on plastic (data not shown). RT-PCR data from experiments performed on differentiated cells demonstrated that CSC increased murine Muc5b mRNA levels in mMEEC in a dose-dependent fashion at 2 and 8 hours (Fig. 2A). Semi-quantitative densitometry of three separate experiments demonstrated a trend toward CSC-induced increased expression (Fig. 2C). In additional experiments on differentiated mMEEC, quantitative real time PCR results showed statistically significant dose and time course dependent increases in Muc5b transcription with CSC (Fig. 2D) with 20 and 40 μg/mL at 2 hours and with 10 and 20 μg/mL at 8 hours. After 8 hours at the higher dose (40 μg/mL) and at longer exposure times (24 hours), a decrease in upregulation was noted. This is likely due to increased apoptosis and decreased cell viability that has been previously observed in epithelial cells exposed to these higher CSC doses and times.36

Fig. 2.

Cigarette smoke condensate (CSC) upregulates Muc5b gene expression in differentiated murine middle ear epithelial cells (mMEEC). (A) Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) shows increased expression of Muc5b mRNA with increasing doses of CSC at 2 and 8 hours. (B) Murine organ tissue controls for PCR primers demonstrate an amplicon of 309 bp, signifying expression of Muc5b mRNA in stomach but not in spleen, as expected. (C) Semiquantitative densitometry from three separate RT-PCR experiments. (D) Quantitative real-time PCR demonstrates statistically significant increases in Muc5b mRNA at 2 and 8 hours (*P = .01, **P < .001).

CSC Increases the Activity of the Murine Muc5b Promoter in mMEEC

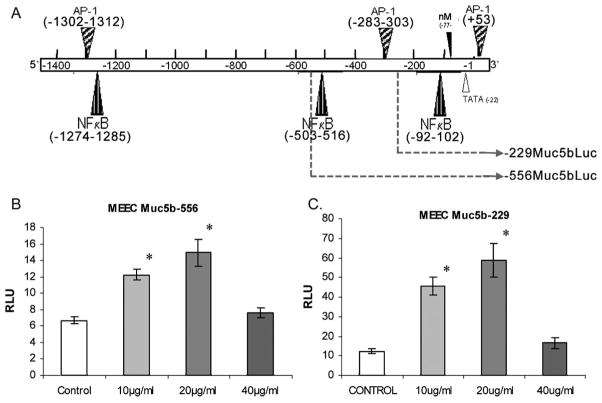

To determine whether the observed increases in Muc5b mRNA levels with CSC were due to increased transcriptional regulation, studies were performed to determine whether CSC increased promoter activity of constructs of differing lengths of the Muc5b 5′ flanking region (Fig. 3A). Luciferase reporter gene assays (Fig. 3B, 3C) demonstrated statistically significant relative Luciferase unit (RLU) 1.8, 2.2, and 1.2 fold activation of the −556 bp Muc5b promoter construct in MEEC with 10, 20, and 40 μg/mL respectively (P < .001). Similarly, results show 3.7, 4.8, and 1.3 fold activation of the −229 bp Muc5b promoter in MEEC with 10, 20, and 40 μg/mL of CSC respectively (P < .001). The results suggest that the observed increase in Muc5b mRNA expression induced by CSC is at least partially regulated at the transcriptional level. As shown in Figure 3A, MatInspector analysis (Genomatix MatInspector, Munich, Germany, www.genomatix.de; v. 3.0, 0.80/Opt. −0.03) shows the presence of two AP-1 and two NFκB cis-sites in the Muc5b −556 construct and one AP-1 and one NFκB site in the −255 construct.

Fig. 3.

Luciferase reporter activity in murine middle ear epithelial cells (mMEEC) after stimulation with CSC. (A) Putative nuclear factor kappa (NFkB) and AP1 transcription factor sites are identified in the 1.7-kb murine Muc5b promoter. Two plasmids containing different lengths of the Muc5b promoter as indicated by dashed lines were cloned into PGL4 Luc (as described in the Methods) vectors and co-transfected along with a β-gal reporter plasmid into mMEEC. (B) Results show significant activation of the −556 bp Muc5b promoter construct relative to β-gal with CSC stimulation (*P < .001). 2C) Similarly, results show significant activation of the −229 bp Muc5b promoter construct relative to β-gal with CSC (*P < .001).

DISCUSSION

Tobacco smoke exposure has been shown to be a significant epidemiologic risk factor for the development of otitis media3,4,6,11,37 but mechanisms whereby cigarette smoke products contribute to the pathogenesis of otitis media have not been previously studied. NF-κB has been demonstrated to be a major intracellular mediator of cigarette smoke effects, and studies have shown that cigarette smoke products activate NF-κB in macrophages,13 human lung epithelial cells,14 and squamous cell lines.15 In studies using lung epithelial cells, CSC-mediated effects have been noted to be dose and time dependent, resulting in the activation of numerous genes with NFκB cis-sites in their 5′-upstream flanking sequences.15,36,38 Increased expression levels of NF-κB have been shown in bronchial biopsies of smokers.16 Given these reports, and the fact that NF-κB has also been purported to be a major mediator of the chronic inflammatory response seen in OM,17 we first sought to investigate whether CSC would be able to activate NF-κB in mMEEC.

Our data shown in Figure 1 qualitatively and quantitatively demonstrate that CSC causes nuclear translocation of NF-κB and functional activation of NF-κB in mMEEC. Luciferase reporter results show that CSC induces activation of consensus NF-κB reporter constructs transiently transfected into mMEEC (Fig. 1A). EMSA results (Fig. 1B) demonstrate increased binding of an NF-κB binding complex in 20 μg/mL CSC stimulated mMEEC nuclear extracts. Chemiluminescent transcription factor assay results (Fig 1C) further confirm that CSC is able to activate nuclear translocation of NF-κB, where it is able to bind to its consensus oligonucleotide sequence.

In the lung cell biology field, studies have shown that cigarette smoke mediated NF-κB activation increases transcription of the secreted mucin gene MUC5AC in respiratory epithelial cells through a signal transduction pathway involving the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)39–41 Because mucin overproduction is also a key pathologic feature of OM, the second aim of this study was to determine whether mucin gene induction would occur in the middle ear cell models exposed to cigarette smoke products. As opposed to the lower airways, where MUC5AC is the predominant mucin in secretions, studies in human OM have shown that MUC5B is the predominant mucin in chronic middle ear disease24–27,28 Therefore, we analyzed whether CSC activated Muc5b transcription in a murine-cultured cell model of OM, mMEEC.

Our results demonstrate both qualitatively and quantitatively that CSC upregulates Muc5b mRNA levels in differentiated murine middle ear cell line mMEEC at 2 and 8 hours (Fig. 2A, C, and D). Notably, these findings are consistent with the EMSA and TFA results shown in Figure 1, which demonstrate maximal consensus sequence binding of an NF-κB binding complex at 20 μg/mL of CSC, the same dose at which maximum Muc5b mRNA induction is noted. At the higher CSC dose (40 μg/mL) and at longer exposure times (24 hours) a decrease in Muc5b mRNA upregulation was noted even to below basal levels. This is likely due to the increased apoptosis and decreased cell viability previously observed in epithelial cells exposed to these higher CSC doses and times.36 Considering that the Muc5b promoter contains several putative NF-κB binding sites, we also sought to investigate whether CSC could activate Muc5b promoter reporter plasmids. The −556 bp Muc5b promoter plasmid includes two possible NF-κB sites while the −229 bp Muc5b promoter plasmid has only one NF-κB cis-site (Fig 3A). Our luciferase reporter data (Fig 3B and C) show that CSC induces similar functional activation of both Muc5b promoter deletion constructs transfected into mMEEC. One might have expected the induction to have been greater in the longer deletion construct with one more NF-κB site, but it is possible that the longer construct contains a negative regulator binding element. Also, it is possible that other transcription factors such as Sp1 and AP1 contribute to promoter activity in both plasmids. EMSA and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays are currently ongoing in our lab to determine whether NF-κB actually binds these specific cognate sites in the Muc5b promoter, and whether other transcription factors also play a pivotal role in mMEEC after CSC exposure. Finally, site specific mutagenesis directed luciferase constructs are being generated to determine if these sites are indeed responsible for the CSC induced increased Muc5b promoter activity.

Notably, the higher dose of CSC (40 μg/mL) induced activity of the Muc5b promoter constructs in contradistinction to the RT-PCR results showing a decrease in Muc5b mRNA levels. There are two possible explanations for this. First, luciferase assays measure whether the exogenously transfected Muc5b promoter is upregulated by transcription factors activated by CSC independent of whether there is a potential for diminished cell viability (because of internal normalization with βGal co-transfection) which could account for the decrease in actual gene transcripts measured with RT-PCR. Second, the luciferase assays were performed on mMEEC grown on plastic, while RT-PCR measures of gene transcription were performed on differentiated cells grown on air liquid interface (ALI). It is possible that higher doses of CSC are more toxic to the differentiated cells. We are currently performing measures of cell viability and apoptosis in mMEEC exposed to CSC under both growth conditions.

In conclusion, dissolved cigarette smoke particulate matter activates NF-κB in immortalized MEEC. Furthermore, this activation correlates with CSC-induced Muc5b promoter activation and gene expression in mMEEC. Taken together, these results indicate that much as in lung cells, the activation of mucin gene expression by cigarette smoke is mediated in part by NF-κB.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Triological Society Career Development Award and by an Avery Scholar Research Award from Children’s National Medical Center to D.P.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Cherry DK, Woodwell DA. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2000 summary. Adv Data. 2002:1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenfeld RM, Casselbrant ML, Hannley MT. Implications of the AHRQ evidence report on acute otitis media. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:440–448. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2001.119326. discussion 439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of involuntary smoking: a report of the Surgeon General DHHS. Publication No. [CDC] 87-8398. Washington, D.C: U.S. DHHS, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Committee on Passive Smoking, Board on Environmental Studies and Toxicology, National Research Council. Environmental tobacco smoke: measuring exposure and assessing health effects. Washington, DC: National Academics Press; 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Respiratory health effects of passive smoking: lung cancer and other disorders. Washington, D.C: USEPA Office of Research and Development; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Cancer Institute. Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 10. US DHHS, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 1999. Health effects of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke: the report of the California Environmental Protection Agency. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daly KA, Giebink GS. Clinical epidemiology of otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:S31–36. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200005001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daly KA, Rovers MM, Hoffman HJ, et al. Recent advances in otitis media. 1. epidemiology, natural history, and risk factors. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 2005;194:8–15. doi: 10.1177/00034894051140s104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhooge IJ. Risk factors for the development of otitis media. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2003;3:321–325. doi: 10.1007/s11882-003-0092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rovers MM, de Kok IM, Schilder AG. Risk factors for otitis media: an international perspective. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70:1251–1256. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stenstrom C, Ingvarsson L. Otitis-prone children and controls: a study of possible predisposing factors. 2. Physical findings, frequency of illness, allergy, day care and parental smoking. Acta Otolaryngol. 1997;117:696–703. doi: 10.3109/00016489709113462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sen R, Baltimore D. Multiple nuclear factors interact with the immunoglobulin enhancer sequences. Cell. 1986;46:705–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang SR, Chida AS, Bauter MR, et al. Cigarette smoke induces proinflammatory cytokine release by activation of NF-kappaB and posttranslational modifications of histone deacetylase in macrophages. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L46–57. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00241.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shishodia S, Potdar P, Gairola CG, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin (diferuloylmethane) down-regulates cigarette smoke-induced NF-kappaB activation through inhibition of Ikappa-Balpha kinase in human lung epithelial cells: correlation with suppression of COX-2, MMP-9 and cyclin D1. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:1269–1279. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anto RJ, Mukhopadhyay A, Shishodia S, Gairola CG, Aggarwal BB. Cigarette smoke condensate activates nuclear transcription factor-kappaB through phosphorylation and degradation of IkappaB(alpha): correlation with induction of cyclooxygenase-2. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:1511–1518. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.9.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Stefano A, Caramori G, Oates T, et al. Increased expression of nuclear factor-kappaB in bronchial biopsies from smokers and patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:556–563. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00272002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrett TQ, Kristiansen LH, Ovesen T. NF-kappaB in cultivated middle ear epithelium. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;67:895–903. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(03)00137-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Seuningen I, Perrais M, Pigny P, Porchet N, Aubert JP. Sequence of the 5′-flanking region and promoter activity of the human mucin gene MUC5B in different phenotypes of colon cancer cells. Biochem J. 2000;348(Pt 3):675–686. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monack DM, Mueller A, Falkow S. Persistent bacterial infections: the interface of the pathogen and the host immune system. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:747–765. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sansonetti PJ. War and peace at mucosal surfaces. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:953–964. doi: 10.1038/nri1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Backert S, Konig W. Interplay of bacterial toxins with host defence: molecular mechanisms of immunomodulatory signalling. Int J Med Microbiol. 2005;295:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rose MC, Voynow JA. Respiratory tract mucin genes and mucin glycoproteins in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:245–278. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00010.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giebink GS, Le CT, Paparella MM. Epidemiology of otitis media with effusion in children. Arch Otolaryngol. 1982;108:563–566. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1982.00790570029007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung MH, Choi JY, Lee WS, Kim HN, Yoon JH. Compositional difference in middle ear effusion: mucous versus serous. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:152–155. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200201000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin J, Tsuboi Y, Rimell F, et al. Expression of mucins in mucoid otitis media. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2003;4:384–393. doi: 10.1007/s10162-002-3023-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin J, Tsuprun V, Kawano H, et al. Characterization of mucins in human middle ear and Eustachian tube. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280:L1157–1167. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.6.L1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schousboe LP, Rasmussen LM, Ovesen T. Induction of mucin and adhesion molecules in middle ear mucosa. Acta Otolaryngol. 2001;121:596–601. doi: 10.1080/000164801316878881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elsheikh MN, Mahfouz ME. Up-regulation of MUC5AC and MUC5B mucin genes in nasopharyngeal respiratory mucosa and selective up-regulation of MUC5B in middle ear in pediatric otitis media with effusion. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:365–369. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000195290.71090.A1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Escande F, Porchet N, Aubert JP, Buisine MP. The mouse Muc5b mucin gene: cDNA and genomic structures, chromosomal localization and expression. Biochem J. 2002;363:589–598. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3630589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Y, Zhao YH, Wu R. In silico cloning of mouse Muc5b gene and upregulation of its expression in mouse asthma model. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1059–1066. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.6.2012114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsuchiya K, Kim Y, Ondrey FG, Lin J. Characterization of a temperature-sensitive mouse middle ear epithelial cell line. Acta Otolaryngol. 2005;125:823–829. doi: 10.1080/00016480510031533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi JY, Kim CH, Lee WS, Kim HN, Song KS, Yoon JH. Ciliary and secretory differentiation of normal human middle ear epithelial cells. Acta Otolaryngol. 2002;122:270–275. doi: 10.1080/000164802753648141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nordskog BK, Fields WR, Hellmann GM. Kinetic analysis of cytokine response to cigarette smoke condensate by human endothelial and monocytic cells. Toxicology. 2005;212:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schick S, Glantz S. Philip Morris toxicological experiments with fresh sidestream smoke: more toxic than mainstream smoke. Tob Control. 2005;14:396–404. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.011288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanno T, Brown K, Siebenlist U. Evidence in support of a role for human T-cell leukemia virus type I Tax in activating NF-kappa B via stimulation of signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11745–11748. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.11745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hellermann GR, Nagy SB, Kong X, Lockey RF, Mohapatra SS. Mechanism of cigarette smoke condensate-induced acute inflammatory response in human bronchial epithelial cells. Respir Res. 2002;3:22. doi: 10.1186/rr172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ilicali OC, Keles N, De er K, Sa un OF, Guldiken Y. Evaluation of the effect of passive smoking on otitis media in children by an objective method: urinary cotinine analysis. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:163–167. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200101000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kode A, Yang SR, Rahman I. Differential effects of cigarette smoke on oxidative stress and proinflammatory cytokine release in primary human airway epithelial cells and in a variety of transformed alveolar epithelial cells. Respir Res. 2006;7:132. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shao MX, Nakanaga T, Nadel JA. Cigarette smoke induces MUC5AC mucin overproduction via tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme in human airway epithelial (NCI-H292) cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287:L420–427. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00019.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takeyama K, Jung B, Shim JJ, et al. Activation of epidermal growth factor receptors is responsible for mucin synthesis induced by cigarette smoke. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280:L165–172. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.1.L165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gensch E, Gallup M, Sucher A, et al. Tobacco smoke control of mucin production in lung cells requires oxygen radicals AP-1 and JNK. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:39085–39093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406866200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duffey DC, Chen Z, Dong G, et al. Expression of a dominant-negative mutant inhibitor-kappaBalpha of nuclear factor-kappaB in human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma inhibits survival, proinflammatory cytokine expression, and tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3468–3474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]