Introduction

Despite significant progress over the last decade in the characterization and validation of numerous forms of preschool psychopathology, the area of bipolar disorder remains perhaps the most controversial. The difficulty of distinguishing normative extremes in mood intensity and lability known to characterize early childhood from those emotions and behaviors that cross the threshold into clinically significant psychopathology is a central issue. Further, another fundamental problem is the ongoing lack of clarity about the diagnostic criteria and validity of the diagnosis in older children as phenotypes in older children are a key source for the downward extension of nosologies in the preschool period. Along this line, contrasting definitions of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents have been proposed and tested. This definitional debate remains a salient issue in the existing literature. Questions about the basic validity of the diagnosis in children, its temporal features and continuity into adulthood, as well as treatment are only a few key areas debated in both the psychiatric literature and in public forums [1].

While a growing body of empirical research is available to inform these issues in older children, studies in preschoolers remain scarce. Along this line, the studies that are available in preschoolers with suspected bipolar disorder are limited predominantly to case reports and chart reviews. There is a smaller body of systematic literature but many of these studies are limited by retrospective designs with small sample size. More recently, for example Danielyan et al [2] reviewed 26 outpatient charts of preschoolers referred to a psychiatric clinic and found high recovery and relapse rates. Similarly, Ferreira Maia et al [3] also retrospectively reviewed outpatient charts in a mood disorders clinic and found preschoolers to have classic symptoms of mania, but the reports were also limited by the small sample size of preschoolers who met DSMIV bipolar disorder criteria (n=8). Classic features of mania such as elation, grandiosity, psychomotor agitation and decreased need for sleep were also observed by Dilsaver & Akiskal [4] over two years and a family history notable for affective illness was described. Three presumptive cases of preschool bipolar disorder were also described as having classic symptoms or “cardinal features” by Luby et al [5], but these cases were from a specialty preschool mood disorders clinic and with potentially limited generalizability. One larger systematic investigation of preschoolers in a community-based sample investigated the presence of age adjusted mania symptoms [6]. Ironically, there is a somewhat larger body of literature on treatment in preschoolers although this is limited to case reports and retrospective chart reviews with only a couple of open label investigations available to date.

Review of Nosology in Older Children: Implications for Study of Preschoolers

Amidst the ongoing debate on the appropriate criteria for diagnosis in older children, the rate of clinical diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children has increased 40-fold between 1994-2003 [7]. The precise sources of this increase in diagnosis remain unclear. However, there is significant concern that the diagnosis may be liberally and non-specifically applied in many cases. Multiple perspectives exist as to what primary symptoms best characterize the disorder and importantly how to distinguish it from other disruptive behavioral disorders, especially Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) [8-11]. Geller and colleagues [12] have provided empirical data suggesting that all DSM-IV symptom, but not standard episode, criteria must be met to make the diagnosis in childhood. This group has provided data suggesting that the cardinal features of mania, elation, grandiosity, hypersexuality, flight of ideas (racing thoughts), and increased energy along with decreased need for sleep are the best discriminators from ADHD. While some argue that irritability is a highly non-specific symptom in childhood psychopathology, others suggest that “extreme irritability” is a key marker of the disorder in childhood [13, 14]. The supporters of this perspective have argued that extreme irritability is a central feature of the diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Others have suggested that the irritability is a non specific feature of many childhood psychiatric disorders and therefore cannot be used as a marker of childhood bipolar disorder [12, 15]. Leibenluft et al [16] have proposed another view, outlined below, in which a distinction between broad and narrow phenotypes is made.

Symptom Duration and Frequency Criteria in Older Children

In addition to questions about the most sensitive and specific symptom criteria for diagnosis, the duration and related temporal features of these symptoms are also an area of debate. The question of whether the same duration criteria for adult bipolar disorder should be applied to children is currently unclear. Leibenluft and colleagues [16] have suggested that only those children who meet full symptom criteria and who demonstrate discrete episodes of mania would be designated as “bipolar” also referred to as the “narrow” phenotype. Alternatively, the “broad” phenotype encompasses those who had a chronic, non-episodic illness characterized by irritability and hyper-arousal but do not necessarily manifest cardinal features of mania (elation and grandiosity). In addition to this narrow and broad phenotype, they suggested two intermediate groups: one to include those with shorter duration criteria of 1 to 3 days including distinct manic episodes; the second to incorporate distinct episodes of severe irritability but not “cardinal” mania symptoms of elation and grandiosity [16].

Modification of duration criteria more appropriate for children has been suggested by several additional research groups who study the disorder in school age children [15, 17, 18]. More specifically, Tillman & Geller [18] have described and distinguished between episodes and cycling. Episodes are used to describe the entire duration of illness, whereas cycling refers to fluctuations of mood within an episode. Tilllman & Geller [18] adapted definitions from Kramlinger and Post [19] and redefined what was previously referred to as rapid cycling as four or more episodes in a year; ultra-rapid as mood fluctuations every few days to a few weeks, and fluctuation within one day as ultradian cycling. Their data suggest that children have a more non-episodic, chronic course than older adolescents and adults who often have distinct episodes of fluctuation in mood [15, 18]. This apparent developmental difference in the phenomenology of pre-pubertal bipolar disorder suggests that assuming that adult based criteria can be simply extrapolated to children is unwise. Along this line, even greater caution in the generalization of adult based phenomenology to the youngest of children is also advisable.

Emerging Literature in Preschoolers

While there is a dearth of studies which have systematically studied mania symptoms in preschoolers as outlined above, the existing literature has begun to shed some light on this area of early psychopathology. Developmental manifestations of mania symptoms among preschool aged children have been described in case reports of preschoolers with suspected bipolar disorder. For example, common among these case reports are observations of excessive energy, decreased need for sleep, impairing elation as well as hyper-sexuality although the latter appears perhaps less common than the others. Furthermore these preschoolers were generally described as highly impaired and challenging to treat. Historically, case histories have depicted presumptively manic, impaired preschoolers as far back as the late 1800s [20-24]. More recently, increasing numbers of published case series describing mania manifestations during the preschool period have emerged [2-5, 25]. Tumuluru et al [25] described mania in six hospitalized preschoolers who had irritable but not elated mood, decreased need for sleep, with significant impairment leading to hospitalization. They further noted that all met DSM criteria for ADHD at some time point as well; further all six children were described to have a strong family history of affective illness. Similarly, family history of affective illness was also noted in an additional open case series of community mental health clinic patients with mania, but in contrast to the former study, more classical features of mania were described including elation [4]. Elation along with other age adjusted classical features of mania were described in a series of suspected bipolar cases in several outpatient specialty mood disorders clinics [3, 5]; these studies also reported family history of affective illness in the affected preschoolers. Conversely, aggression and irritability were the most common symptoms reported among presumptive bipolar preschoolers in a chart review of 26 outpatients [2]. This review contributed to the literature by noting high relapse rates (defined as meeting hypomania or mania criteria along with moderate symptoms requiring intervention as rated by the Clinical Global Impression Scale-Severity (CGI-S greater or equal to 5 and minimally improved for at least 2 weeks) of these preschoolers with suspected bipolar disorder based on an outpatient record review [2]. The phenomenology of preschoolers with presumptive bipolar disorder has recently been more detailed in a systematic investigation outlined below [6].

Luby & Belden [6] reported on a small group (N=26) of preschoolers meeting symptom criteria for BP-I from a larger community-based sample (N=306) over sampled for preschoolers with mood symptoms. An age-appropriate parent informant measure was used to assess for mania symptoms. This specific mania module was developed in collaboration with the authors of the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA) [26, 27] in order to ascertain DSM-IV bipolar symptoms in a developmentally-appropriate manner. Favorable test-retest reliability of the mania module of the PAPA have been established and reported elsewhere [6]. The characteristics of this group and which symptoms distinguished them from both depressed and disruptive preschoolers were described. Study findings indicated that 5 out of 13 DSM-IV bipolar symptoms including elation, grandiosity, hypertalkative, flight of ideas, and hypersexuality, could differentiate bipolar preschoolers from those with disruptive disorders (ADHD, ODD, and/or CD) 92% of the time [6]. Most notably, the bipolar group was found to be more impaired than healthy but notably also more impaired than preschoolers with other Axis I psychiatric disorders (Major Depressive Disorder and DSM IV disruptive groups). This finding emerged even after controlling for co-morbid disorders (important due to high rates of co-morbidity found in this study and well known in the childhood disorder). This sample has been followed longitudinally over two years and longitudinal stability of the bipolar diagnosis has been demonstrated. For example, results indicated that preschoolers diagnosed with bipolar disorder at wave 1 were at 12 times greater risk than non-bipolar preschoolers to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder when assessed 2 years later [28]. Longitudinal data pertaining to symptoms, psychosocial status and family history of psychiatric disorders in this population assessed at preschool age is currently being obtained during school age.

Evidence for Alterations in Emotional Reactivity Characteristics

A key issue in investigating the question of whether bipolar disorder can manifest in preschool children is whether those who manifest symptoms of the disorder also demonstrate differences in patterns of emotional reactivity. Since the disorder is characterized by a fundamental impairment in mood and affect regulation, and related to this, by periods of extremely intense emotional responses, investigating the typical emotion reactivity characteristics (in response to incentive events) of this group relative to others is of interest. Building on the emerging body of data on atypical emotion development, the idea that early onset bipolar disorder may be characterized by alterations in patterns of emotional reactivity has been previously proposed [6].

As a part of an ongoing NIMH funded longitudinal study focusing on preschool mood disorders, the assessment of emotional development and reactivity styles in the study population (and the mood disordered groups in particular) was of interest. Standardized developmental measures of emotion recognition, regulation and social display rules were obtained. However, to assess the child's typical pattern of emotionality, a novel parent report assessment of the intensity and duration of the child's characteristic emotional responses was developed. This measure was designed to elicit from the parent details of the timing and intensity of the child's typical emotional reactions through the use of a narrative depicting commonly experienced evocative events. This approach was thought to capture the child's typical emotional functioning by detailing quantifiable features of emotional response rather than global ratings which are more vulnerable to reporter bias. This measure, dubbed “The Emotion Reactivity Questionnaire” was developed based on an emotion dynamic model of mood disorders described in detail in Luby & Belden [6]. This model posits that the temporal and dynamic features of emotional response may be key to identifying the emotional developmental precursors and characteristics of early onset mood disorders. Observational measures of emotion reactivity or temperament in the laboratory that also quantify the child's emotional response to an evocative event were obtained and will be reported elsewhere. Such objective measures, while potentially highly informative, are limited by lack of representativeness based on the cross-sectional nature of the observation.

The Emotion Reactivity Questionnaire (ERQ) [29] is 28 item measure that assesses the intensity of children's emotional reactions during a 24-hour period based on caregiver report. Four vignettes depicting situations that occur at the very beginning of the day and that are thought to elicit Joy, Sadness, Guilt, or Anger in young children are read to caregivers by an examiner. After hearing each vignette, caregivers are asked to rate the intensity of the emotion reactions they would expect to observe from their children. Caregivers are given an “emotion meter” which allows them to slide and place a red line on an exact intensity from 0 (no emotion reaction) to 100 (very intense emotional reaction). Caregivers were asked to rate their child's emotional reactions at 7 time points immediately after the incentive event depicted in the narrative, 30 minutes after, 60 minutes after, lunchtime, dinnertime, bedtime, and again the next morning when the child woke up. Basic psychometric properties for this new measure have been tested and are described below.

Internal consistency for each of the four emotion subscales using Chronbach's alpha ranged from .87 to .89. The ability of the ERQ to assess emotionally specific reactions of children (vs. global reactions) was evidenced by the results of a Principal Component Analysis illustrating four predominate factors that represented each of the 4 emotions assessed in the ERQ. As described in the findings below, initial indicators are that the ERQ also has strong face validity. Additional analyses were conducted to examine convergent validity between the ERQ and the Child Behavioral Questionnaire (CBQ)[30]; a well established measure of children's dispositional temperament. It was hypothesized that caregivers' reports on the CBQ one year prior to completing the ERQ would be predict mothers' reports of children's initial (i.e., trait like affect disposition) scores on each of the 3 ERQ emotions (the CBQ does not include a guilt subscale). As hypothesized the CBQ sadness subscale was associated to ERQ initial sadness scores 1year later (r = .20, p <.01), CBQ anger subscale scores were associated with ERQ initial anger scores 1 year later (r = .25, p < .001), and CBQ pleasure subscale scores were correlated with ERQ initial joy scores 1 year later (r = .14, p<.05).

Based on these preliminary findings suggesting the ERQ is a psychometrically acceptable measure, we tested whether BP preschoolers' ERQ scores differed significantly from same age peers in healthy and psychiatric comparison groups. Analyses were also conducted to determine whether BP preschoolers versus comparison groups had longer emotion reaction durations, suggesting difficulty with emotion regulation. To address this question, non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test were conducted because of the small sample sizes in 2 out of 3 comparison groups.

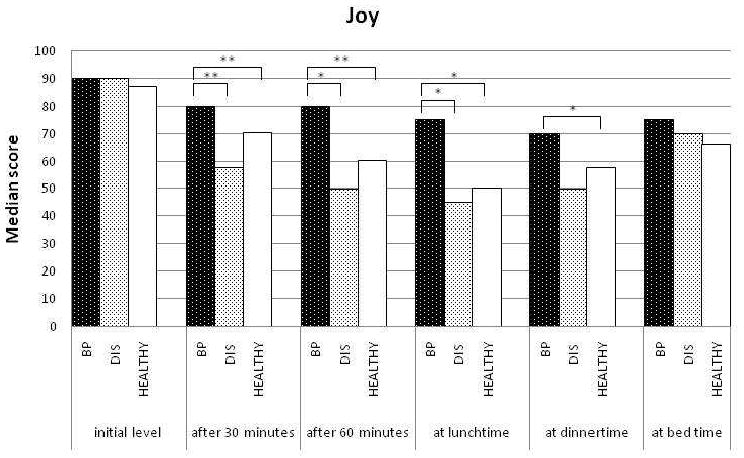

Compared to healthy preschoolers, bipolar preschoolers were described by their parents as expressing significantly higher levels of joy after 30 (M-W test, Z = -2.847, p < .01) and 60 (M-W test, Z = -2.831, p < .01) minutes in response to a joy inducing incentive event (see Figure 1). Bipolar preschoolers also retained higher levels of joy by lunch time (M-W test, Z = -2.514, p < .05) and by dinner time (M-W test, Z = -2.024, p < .05) compared to healthy peers.

Figure 1.

Comparison of joy levels between healthy and bipolar preschoolers.

* p < .05 ** p < .01

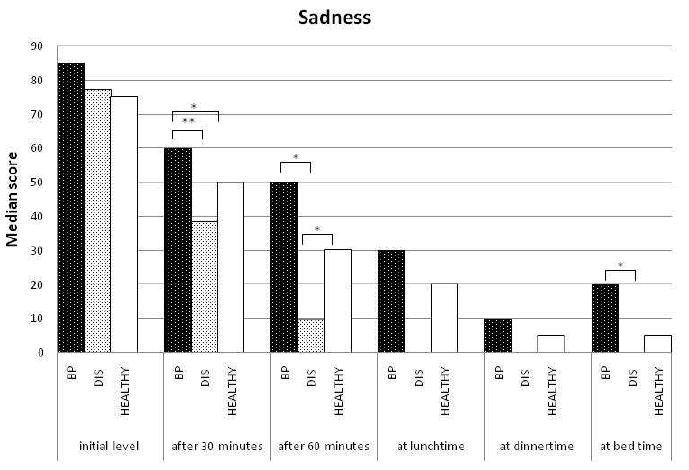

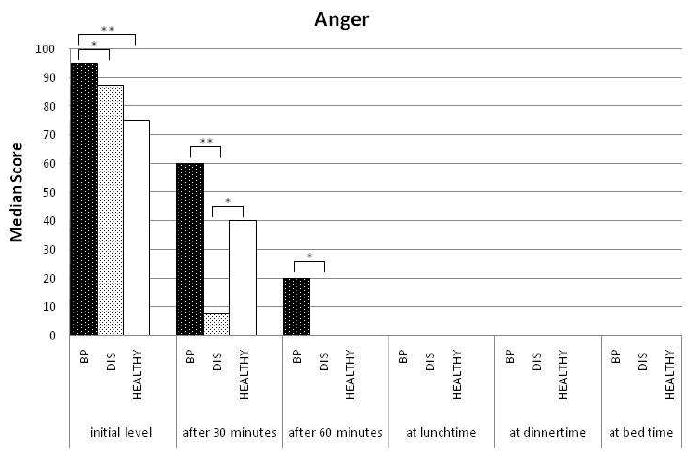

Bipolar preschoolers were also rated as having significantly higher levels of sadness after 30 minutes (M-W test, Z = -2.439, p < .05) compared to healthy preschoolers. Notably, the domain of anger, bipolar preschoolers were also reported to have significantly higher initial levels of anger (M-W test, Z = -3.400, p < .01) and higher levels after 30 minutes (M-W test, Z = -2.111, p < .05) than healthy preschoolers. No other differences between bipolar and healthy preschoolers were found.

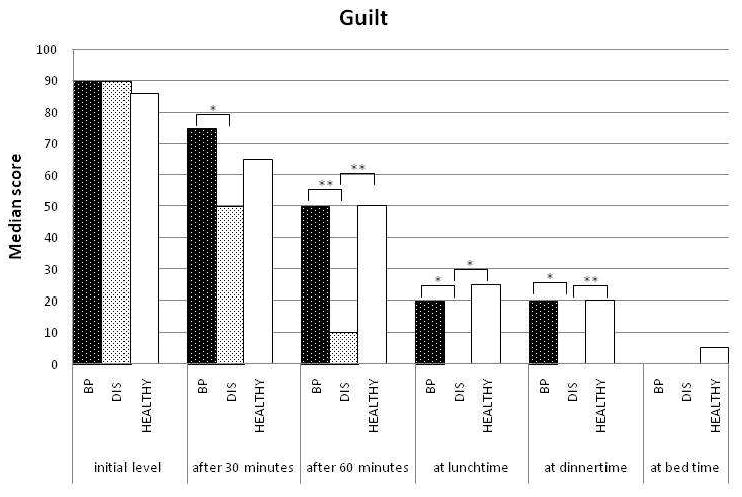

Notably and in contrast to the findings above, preschoolers without bipolar disorder but who had a DSM-IV disruptive disorder were rated by parents as displaying significantly lower levels of sadness than healthy preschoolers after 60 minutes (M-W test, Z = -1.997, p < .05, see Figure 2). Disruptive preschoolers were also reported to display significantly lower levels of anger after 30 (M-W test, Z = -2.129, p < .05), and 60 (M-W test, Z = -1.957, p = .05) minutes compared to healthy peers (see Figure 3). Furthermore, in the area of guilt, they were reported to display significantly lower levels of guilt after 60 minutes (M-W test, Z = -2.845, p < .01), at lunch time (M-W test, Z = -2.558, p < .05) and at dinner time (M-W test, Z = -2.664, p < .01) compared to healthy peers (see Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Comparison of sadness levels between healthy and bipolar preschoolers.

Figure 3.

Comparison of anger levels between healthy and bipolar preschoolers.

* p < .05 ** p < .01

Figure 4.

Comparison of guilt levels between healthy and bipolar preschoolers.

* p < .05 ** p < .01

Comparing bipolar preschoolers to those with disruptive disorders, parents described bipolar preschoolers as expressing significantly higher levels of joy after 30 (M-W test, Z = -2.865, p < .01), and 60 (M-W test, Z = -2.544, p < .05) minutes, as well as at lunch time (M-W test, Z = -2.510, p < .05) compared to parents of disruptive preschoolers. Bipolar preschoolers were also reported to display significantly higher levels of sadness after 30 (M-W test, Z = -3.090, p < .01) and 60 (M-W test, Z = -2.559, p < .05) minutes as well as at bed time (M-W test, Z = -2.377, p < .05). The bipolar group was also rated as having a significantly higher initial level of anger (M-W test, Z = -2.177, p < .05), higher levels of anger after 30 (M-W test, Z = -3.072, p < .01) and 60 (M-W test, Z = -2.168, p < .05) minutes, Similar differences between the groups were also detected in the domain of guilt in which bipolar preschoolers had higher levels of guilt after 30 minutes (M-W test, Z = -2.010, p < .05) and 60 (M-W test, Z = -2.857, p < .01) minutes, at lunch time (M-W test, Z = -2.209, p < .05) and at bed time (M-W test, Z = -2.146, p < .05) compared to disruptive preschoolers.

These findings provide evidence that preschool children who meet DSM-IV symptom criteria for bipolar disorder display more intense emotional responses in the domains of joy, sadness and anger than healthy peers as would be expected. In addition, they also display higher intensities of these emotions (as well as guilt) than a key psychiatric comparison group of children with disruptive disorders. The latter group is of particular importance given that the differential diagnosis between early onset BP and disruptive disorders is particularly difficult clinically. Beyond elevations in intensity, these findings also provide support for the notion that bipolar preschoolers have more difficultly regulating their emotions. This is evidenced by sustained elevations in emotional intensity at periods several hours after the incentive event (e.g. lunch and dinner) compared to healthy and disruptive peers. These findings suggest that an emotion reactivity model may be useful in the understanding and diagnosis of bipolar disorder in young children.

Findings are limited by the fact that they are based on parent report of typical emotional responses. Reporter biases, as well as the fact that diagnostic determinations were also based on parent report, are important issues to consider in the interpretation of these findings. However, this limitation may also be offset by the fact that the measure aimed to obtain an objective and quantitative estimate of the child response through the use of an emotion meter and obtaining estimation at multiple fixed time points over a 24 hour period. Further investigation of emotion reactivity in groups of mood disordered preschoolers using similar measures as well as observational measures is now indicated.

Family History and Bipolar Disorder in Older Children

Elevations in reported rates of bipolar disorder in the older offspring of bipolar parents compared to offspring of healthy parents varies depending on study design. However, prior studies have suggested that the offspring of bipolar parents are at a 4 to 5 times greater risk for any affective disorder (including bipolar disorder) compared to the offspring of parents without mental disorders [31, 32]. One source of variation might be that some meta-analyses have included both adult and child offspring. In a review of studies involving only child and adolescent offspring of parents with bipolar disorder, Delbello & Geller [33] found rates of mood disorders ranging from 5 to 52%. Furthermore, these offspring were also at higher risk for disruptive and anxiety disorders than those from healthy parents [33]. Similarly, Chang et al [34] reported that 51% of the offspring of bipolar parents had psychiatric disorders including bipolar disorder. Parents with earlier onset symptomotology were more likely to have offspring with bipolar disorder [34]. This earlier age of symptom onset has been suggested to be a marker of heritability in a more recent study using genome-wide scanning [35]. In addition to the heritability of early age at onset, poor social functioning and co-morbid conditions have also been suggested to be familial [36].

Implications of Bipolar Family History in Preschool Children

The notion that early onset of bipolar symptoms in a parent may increase the risk of heritability of the disorder suggests that such offspring would be an ideal group in which to search for the study of prodromes or early markers of the disorder. Findings to date in preschool populations have suggested that preschoolers with major depressive disorder (MDD) and family history of bipolar disorder have distinctive symptoms of MDD when compared to preschoolers with MDD but no family history of bipolar disorder. In particular depression in this group was characterized by increased rates of agitation and restlessness [37]. Extrapolating from work of Geller et al [38, 39] suggesting that pre-pubertal children with early onset MDD with a family history of bipolar disorder are at higher risk for later switching to mania, younger depressed children may be an important group to follow and assess for mania based on the hypothesis that they are at a particularly high risk for switching.

Unique behavioral features have been identified in studies of the young children of parents with bipolar disorder in at least one study [40]. More specifically, the rate of behavioral disinhibition among offspring of bipolar parents was significantly increased compared to offspring of parents with both panic disorder and unipolar depression even after controlling for parental ADHD, substance use disorders, conduct disorder and antisocial personality disorder. While this pilot study was limited by the small sample size of the bipolar offspring, it proposes early intervention when markers of risk such as behavioral disinhibition are observed among high risk offspring [40]. Similarly, difficulties sharing and challenges in inhibiting aggressive impulses with peers and adults were observed in 2 year olds who had a parent with bipolar disorder, in a naturalistic observation study focusing on social and emotional functioning of offspring of bipolar parents. Conversely, these children were also noted to have a heightened sense of recognizing suffering in others, despite their difficulty in modulating their own emotions [41, 42].

Differential Diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder in the Preschool Period

The controversy about the nosology of bipolar disorder in older children provides an uncertain frame work for studies of nosology in preschoolers as outlined above. Amidst these diagnostic uncertainties, clinicians are increasingly placed in the position of evaluating preschool children for suspected bipolar disorder. As evidenced by dramatic increases in the rates of clinical diagnosis of bipolar disorder in childhood more generally as mentioned above, clinicians appear to more readily consider the diagnosis of bipolar disorder in young children presenting with intense mood lability or bouts of extreme irritability associated with functional impairment. Because further scientific clarity of the clinical characteristics of the disorder in young children is still needed, proper consideration in the differential diagnosis for other more clearly understood disruptive disorders and/or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is even more critical.

ADHD and Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) are disorders known and relatively well characterized in preschool children. ADHD has been reported to have a prevalence rate of 3.3% in preschoolers, and those with ADHD were reported to have an 8-fold greater rate of ODD [43]. Therefore the occurrence of one of these more common disorders is more likely and must be considered first. Further, at least one report has suggested that preschoolers who meet symptom criteria for bipolar disorder have high rates of co-morbid ODD and ADHD similar to those found in school age bipolar samples [6]. In addition, extreme temper tantrums and irritability in young children may also be a marker of an Autistic Spectrum Disorder, a group of disorders increasing in prevalence. Therefore, in preschool children presenting with extreme irritability, such more commonly occurring diagnoses should be considered and ruled in or out prior to consideration of bipolar disorder.

Differentiating bipolar disorder from these more common disorders may be difficult in cases in which there is a complex co-morbid/developmental delay clinical picture. Key features in differentiating bipolar disorder from Autistic Spectrum disorders are that the latter is characterized by core impairment in social relatedness while bipolar preschoolers would be expected to have intact or often high social interest. Further, stereotypes and perseverations that characterize ASD's are not a typical feature of bipolar disorder, although developmental delay and social rejection may be present.

One of the more challenging aspects of the differential diagnosis is distinguishing oppositional behaviors towards adults found in ODD from grandiosity found in bipolar disorder. It is important to determine whether the oppositional or extremely bossy behavior is generalized or relationship specific; the latter would be associated with ODD rather than bipolar disorder. Perhaps even more importantly is whether this behavior is associated with a fixed and false elevated sense of powers and capabilities that is acted upon. Such behavior is an important manifestation of clinical level and delusional grandiosity which appears to be a key feature of mania that may manifest as early as the preschool period.

Treatment Considerations

Although the diagnostic characteristics of bipolar disorder in the preschool period remains ambiguous as outlined and much empirical work is needed, to date there has been relatively more scientific investigation of treatments for presumptive mania in this age group. Most of the available treatment literature has been descriptive and is composed of case reports and retrospective chart reviews. These reports provide some promising findings for the use of atypical antipsychotic and mood stabilizers both singly and in combination [13, 44-48]. Such observations in uncontrolled clinical settings suggest that systematic open label studies of these agents should be pursued as a next step. An open label study of olanzapine and risperidone was conducted in a sample of preschoolers with a form of bipolar disorder that might best be classified as BP NOS [13]. Either medication rapidly decreased mania symptoms but residual symptoms remained. Similarly, case reports of open-label use of the mood stabilizers, valproate, lithium, topiramate, and carbamazepine have described reduction in preschool mania symptoms with atypical antipsychotics used for augmentation of residual symptoms when necessary [44-48]. While studies of psychotherapeutic interventions for preschool bipolar disorder have not been conducted to date, an age appropriated parent child dyadic treatment modality has been designed and described for treatment of preschool BP for future testing in this population [49].

Conclusion

Although some empirical work has now been added to the larger body of case material, preschool bipolar disorder remains a highly ambiguous diagnostic area. This is notable in the context of the significant progress that has been made in many other areas of psychopathology in the preschool period. While there is a need for well controlled empirical investigations in this area, a small but growing body of empirical literature suggests that some form of the disorder may arise as early as age 3. The need for large scale and focused studies of this issue is underscored by the high and increasing rates of prescriptions of atypical antipsychotics and other mood stabilizing agents for preschool children with presumptive clinical diagnosis of bipolar disorder or a related variant. Clarifying the nosology of preschool bipolar disorder may also be important to better understand of the developmental psychopathology of the disorder during childhood. Data elucidating this developmental trajectory could then inform the design of earlier potentially preventive interventions that may have implications for the disorder across the lifespan.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the study of Preschool Depression and for preparation of this manuscript was provided by NIMH R01 grant to Joan Luby, M.D.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript.The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ghaemi S, Martin A. Defining the boundaries of childhood bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(2):185–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Danielyan A, Pathak S, Kowatch RA, Arszman S, Johns E. Clinical characteristics of bipolar disorder in very young children. J Affect Disord. 2007;97(13):51–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferreira Maia AP, Boarati MA, Kleinman A, Fu IL. Preschool Bipolar Disorder: Brazilian children case reports. J Affect Disord. 2007;104(13):237–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dilsaver SC, Akiskal HS. Preschool-onset mania: incidence, phenomenology and family history. J Affect Disord. 2004;82 1:S35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luby J, Tandon M, Nicol G. Cardinal symptoms of mania in clinically referred preschoolers: Description of three clinical cases with presumptive preschool bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;17(2):237–244. doi: 10.1089/cap.2007.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luby J, Belden A. Defining and validating bipolar disorder in the preschool period. Dev Psychopathol. 2006;18(4):971–88. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moreno C, Laje G, Blanco C, Jiang H, Schmidt AB, Olfson M. National trends in the outpatient diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder in youth. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(9):1032–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.9.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geller B, Williams M, Zimmerman B, Frazier J, Beringer L, Warner K. Prepubertal and early adolescent bipolarity differentiate from ADHD by manic symptoms, grandiose delusions, ultra-rapid or ultradian cycling. J Affect Disord. 1998;51(2):81–91. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00175-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, Del Bello MP, Bolhofner K, Craney JL, Frazier J, Beringer L, Nickelsburg MJ. DSM-IV mania symptoms in a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype compared to attention-deficit hyperactive and normal controls. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2002;12(1):11–25. doi: 10.1089/10445460252943533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leibenluft E, Rich BA. Pediatric bipolar disorder. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:163–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biederman J, Klein RG, Pine DS, Klein DF. Resolved: mania is mistaken for ADHD in prepubertal children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(10):1091–6. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199810000-00020. discussion 1096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, DelBello MP, Frazier J, Beringer L. Phenomenology of prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder: Examples of elated mood, grandiose behaviors, decreased need for sleep, racing thoughts and hypersexuality. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2002;12(1):3–9. doi: 10.1089/10445460252943524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biederman J, Faraone SV, Wozniak J, Mick E, Kwon A, Clayton GA, Clark SV. Clinical correlates of bipolar disorder in a large, referred sample of children and adolescents. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2005;39:611–622. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wozniak J, Biederman J, Kwon A, Mick E, Faraone S, Orlovsky K, Schnare L, Cargol C, van Grondelle A. How cardinal are cardinal symptoms in pediatric bipolar disorder? An examination of clinical correlates. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(7):583–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geller B, Tillman R, Craney JL, Bolhofner K. Four-year prospective outcome and natural history of mania in children with a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(5):459–67. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.5.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leibenluft E, Charney DS, Towbin KE, Bhangoo RK, Pine DS. Defining clinical phenotypes of juvenile mania. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(3):430–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.3.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biederman J, Mick E, Faraone SV, Spencer T, Wilens TE, Wozniak J. Pediatric mania: a developmental subtype of bipolar disorder? Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(6):458–66. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00911-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tillman R, Geller B. Definitions of Rapid, Ultrarapid, and Ultradian Cycling and of Episode Duration in Pediatric and Adult Bipolar Disorders: A Proposal to Distinguish Episodes from Cycles. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2003;13(3):267–271. doi: 10.1089/104454603322572598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kramlinger KG, Post RM. Ultra-rapid and ultradian cycling in bipolar affective illness. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168(3):314–23. doi: 10.1192/bjp.168.3.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feinstein SC, Wolpert EA. Juvenile manic-depressive illness. Clinical and therapeutic considerations. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1973;12(1):123–36. doi: 10.1097/00004583-197301000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson RJ, Jr, Schindler FH. Embryonic mania. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 1976;6(3):149–54. doi: 10.1007/BF01435496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinberg WA, Brumback RA. Mania in childhood: case studies and literature review. Am J Dis Child. 1976;130(4):380–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1976.02120050038006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greves HE. Acute mania in a child of five years; recovery; remarks. Lancet. 1884;ii:824–826. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kraepelin E. Manic-depressive insanity and paranoia. Edinburgh: H.S. Livingson Ltd.; 1921. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tumuluru RV, Weller EB, Fristad MA, Weller RA. Mania in six preschool children. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2003;13(4):489–94. doi: 10.1089/104454603322724878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Egger HL, Ascher B, Angold A. Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA):Version1.1. Center for Developmental Epidemiology, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University Medical Center; Durham, NC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egger HL, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Potts E, Walter B, Angold A. Test-Retest Reliability of the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA) Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45(5):538–549. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000205705.71194.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luby J, Belden A, Tandon M. Bipolar Disorder in the Preschool Period: Focus on Development and Differential Diagnosis. In: Miklowitz DJ, Cicchetti D, editors. Bipolar Disorder: A Development Psychopathology Approach. Guilford Press; New York: in press. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belden A, Luby J. The Emotion Reactivity Questionnaire Unpublished Measure. Washington University School of Medicine. 2005 Early Emotional Development Program. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Hershey KL, Fisher P. Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: the Children's Behavior Questionnaire. Child Dev. 2001;72(5):1394–408. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lapalme M, Hodgins S, LaRoche C. Children of parents with bipolar disorder: a metaanalysis of risk for mental disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 1997;42(6):623–31. doi: 10.1177/070674379704200609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Todd RD, Reich W, Petti TA, Joshi P, DePaulo JR, Jr, Nurnberger J, Jr, Reich T. Psychiatric diagnoses in the child and adolescent members of extended families identified through adult bipolar affective disorder probands. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(5):664–71. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199605000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DelBello MP, Geller B. Review of studies of child and adolescent offspring of bipolar parents. Bipolar Disord. 2001;3(6):325–34. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2001.30607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang KD, Steiner H, Ketter TA. Psychiatric phenomenology of child and adolescent bipolar offspring. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(4):453–60. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200004000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faraone SV, Glatt SJ, Su J, Tsuang MT. Three potential susceptibility loci shown by a genome-wide scan for regions influencing the age at onset of mania. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(4):625–30. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schulze TG, Hedeker D, Zandi P, Rietschel M, McMahon FJ. What is familial about familial bipolar disorder? Resemblance among relatives across a broad spectrum of phenotypic characteristics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(12):1368–76. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.12.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luby JL, Mrakotsky C. Depressed preschoolers with bipolar family history: a group at high risk for later switching to mania? J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2003;13(2):187–97. doi: 10.1089/104454603322163907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Geller B, Fox LW, Clark KA. Rate and predictors of prepubertal bipolarity during follow-up of 6-to 12-year-old depressed children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33(4):461–8. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199405000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, Bolhofner K, Craney JL. Adult psychosocial outcome of prepubertal major depressive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(6):673–7. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200106000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hirschfeld-Becker D, Biederman J, Henin A, Faraone S, Cayton G, Rosembaum J. Laboratory-observed behavioral disinhibition in the young offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;136:265–271. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zahn-Waxler C, Cummings EM, McKnew DH, Radke-Yarrow M. Altruism, aggression, and social interactions in young children with a manic-depressive parent. Child Dev. 1984;55(1):112–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zahn-Waxler C, McKnew DH, Cummings EM, Davenport YB, Radke-Yarrow M. Problem behaviors and peer interactions of young children with a manic-depressive parent. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141(2):236–40. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.2.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Egger HL, Kondo D, Angold A. The Epidemiology and Diagnostic Issues in Preschool Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Review. Infants & Young Children: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Special Care Practices. 2006;19(2):109–122. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mota-Castillo M, Torruella A, Engels B, Perez J, Dedrick C, Gluckman M. Valproate in very young children: an open case series with a brief follow-up. J Affect Disord. 2001;67:193–197. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00431-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pavuluri MN, Janicak PG, Carbray J. Topiramate plus risperidone for controlling weight gain and symptoms in preschool mania. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2002;12(3):271–3. doi: 10.1089/104454602760386978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pavuluri MN, Henry DB, Carbray JA, Sampson GA, Naylor MW, Janicak PG. A one-year open-label trial of risperidone augmentation in lithium nonresponder youth with preschool-onset bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2006;16(3):336–50. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.16.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scheffer RE, Niskala Apps JA. The diagnosis of preschool bipolar disorder presenting with mania: open pharmacological treatment. J Affect Disord. 2004;82 1:S25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tuzun U, Zoroglu SS, Savas HA. A 5-year-old boy with recurrent mania successfully treated with carbamazepine. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;56(5):589–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2002.01059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luby J, Stalets M, Blankenship S, Pautsch J, McGrath M. Treatment of preschool bipolar disorder: A novel parent-child interaction therapy and review of data on psychopharmacology. In: Geller B, DelBello M, editors. Treatment of Childhood Bipolar Disorder. 2008. pp. 270–286. [Google Scholar]