Abstract

The contribution of the parietal cortex to episodic memory is a fascinating scientific puzzle. On one hand, parietal lesions do not normally yield severe episodic memory deficits, but on the other hand, parietal activations are seen frequently in functional neuroimaging studies of episodic memory. A review of these two categories of evidence suggests that the answer to the puzzle requires us to distinguish between dorsal and ventral parietal regions and between top-down vs. bottom-up attention as they are applied to memory.

If twenty years ago a neurologist had been asked if the parietal cortex played an important role in episodic memory, the answer probably would have been negative. Such an answer would have been quite reasonable given the fact that parietal lesions do not yield severe episodic memory deficits, such as the ones associated with damage to the medial temporal lobe (MTL). During the last two decades, however, numerous studies using event-related potentials (ERPs),1 positron emission tomography (PET), and functional MRI (fMRI)2 have shown that the parietal cortex is one of the regions most frequently activated during episodic memory retrieval. Thus, the contribution of parietal regions to episodic memory constitutes an intriguing scientific puzzle. Potential answers to this problem have begun to emerge only recently. First, the development of event-related fMRI methods has allowed imaging researchers to specify the types of memory processes that are associated with activations in different parietal subregions. Second, a few neuropsychological studies have demonstrated that parietal lesions do impair certain episodic memory processes. Finally, memory researchers have started focusing on the contributions of the parietal cortex and have proposed several hypotheses with clear, testable predictions. As result, a new domain of cognitive neuroscience research has emerged with a critical mass of empirical evidence and a set of testable hypotheses.

The goal of the present article is to provide a concise overview of this new domain of inquiry. We begin by summarizing accepted ideas regarding the anatomy and function of the parietal cortex. This is followed by a review of recent findings from neuropsychology and neuroimaging studies that link parietal function to episodic retrieval. This review is intended for the general neuroscience audience; more detailed reviews intended for memory experts can be found in other related publications.72,73 Finally, we review the potential explanations for these findings and discuss our attention-based hypothesis. We end by considering several open questions about the contribution of parietal lobe to episodic memory.

Anatomy and Functions of Parietal Cortex

The parietal cortex includes a strip posterior to the central sulcus that is specialized for somatosensory function (Brodmann areas [BAs] 1, 2, 3, and 5) as well as regions posterior to that strip that are known as posterior parietal cortex and may be grossly divided into a medial and a lateral portion. The medial parietal lobe consists primarily of the precuneus. The precuneus is sometimes considered together with posterior cingulate and retrosplenial regions, which are areas where lesions can produce amnesia.3-5 However, posterior cingulate and retrosplenial cortices are not parietal regions, and hence, they are not discussed in this review. The posterior parietal cortex may also be divided into the dorsal and ventral regions. The dorsal parietal cortex (DPC) includes the lateral cortex in the banks of the intraparietal sulcus (IPS) and the superior parietal lobule, as well as medial parietal cortex (precuneus). The ventral parietal cortex (VPC) includes lateral cortex ventral to the IPS, including the supramarginal gyrus and the angular gyrus (see Figure 1A) The DPC roughly corresponds to BA7 (lateral and medial), and the VPC to BAs 39 and 40 (typically called the inferior parietal lobe).

Figure 1.

Subdivisions and connectivity of the posterior parietal cortex. A. The posterior parietal cortex may be divided into the dorsal parietal cortex (DPC), which comprises the lateral cortex including and superior to the intraparietal sulcus and the medial parietal cortex (precuneus—not shown), and the ventral parietal cortex (VPC), which includes the supramarginal gyrus and the angular gyrus. DPC largely correspond to Brodmann Area 7, and VPC, to Areas 40 and 39 B. The parietal cortex has direct anatomical connections with many brain regions, including the frontal lobes (via the superior longitudinal fasciculus—SFL, the fronto-occipital fasciculus—FOF, and the arcuate fasciculus—AC), the temporal lobes (via the middle longitudinal fasciculus—MdlF, and inferior longitudinal fasciculus—ILF). (Fasciculi drawings were adapted from ref.10)

As illustrated by Figure 2B, the lateral parietal cortex has direct anatomical connections with many brain regions, including the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex,6-9 temporal cortex,10 and medial parietal11, 12 regions. It also has reciprocal connections with entorhinal, parahippocampal, and hippocampal regions of the MTL.13-19 Analyzing spontaneous fluctuations in the fMRI bold signal20 revealed that the human hippocampal formation has strong functional connections with the VPC. As discussed later, this evidence supports the idea that VPC processes memory information in the same way that it processes sensory information.21

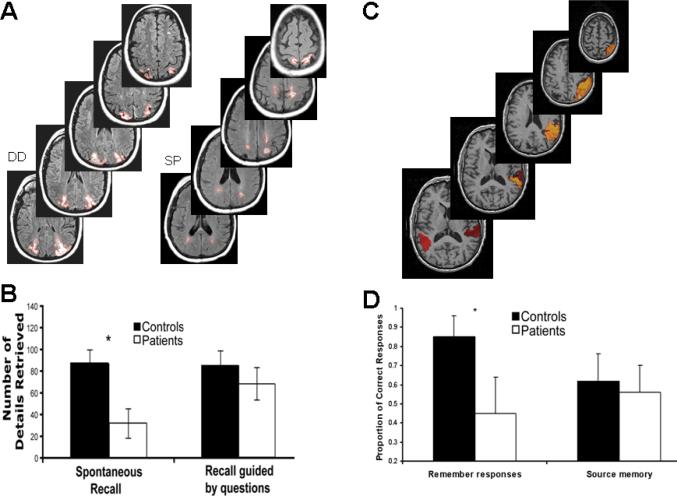

Figure 2.

Parietal lesions and episodic memory. A-B. Autobiographical memory was investigated in two patients with bilateral posterior parietal lesions, which were larger in VPC than DPC32. A. MRI images showing the lesions outlined in red. B. Participants were impaired when they freely recalled events from their lifetime in as much detail as possible, but not when they answered specific questions about the recalled memories. C-D. Recognition and source memory were compared in patients with left and right VPC lesions33. C. The brain slices show the overlap of the lesions. D. Patients were impaired in recollection but not in source memory.

Traditionally, the lateral parietal cortex was not thought to support episodic memory, but rather to be implicated in attention to spatial information, planning and control of movement, multisensory integration, and working memory.21-24 Indeed, unilateral lesions in the inferior parietal cortex often result in hemispatial neglect.25-28 Neglect patients fail to report or to respond spontaneously to stimuli in the contralesional hemifield,28, 29 but they can rely on top-down mechanisms to direct attention or action voluntarily towards locations in any regions of space.30 Bilateral parietal lobe damage can lead to partial or full-blown Balint's syndrome,31 including simultanagnosia, the inability to perceive or attend to more that one visual object or location at a time. However, these lesions do not lead to amnesia.

Parietal lesions and episodic memory

Because parietal lobe damage does not produce retrograde or anterograde amnesia, few investigators have assessed memory in these patients, suggesting that subtle episodic memory deficits could have been overlooked. Recent studies of the effects of parietal lobe damage on autobiographical memory and episodic memory supports this contention.32 Patients with parietal lesions that were mostly in VPC (see Figure 2A) and matched controls were required to recollect various autobiographical memories. In the first condition, they freely recalled events from their lifetime in as much detail as possible. In a second condition, they answered specific questions about the recalled memories. The results showed that parietal lobe damage decreased the vividness and amount of detail freely recalled (similar results were obtained in patients with unilateral lesions; see ref.33). However, when patients were probed for specific details pertaining to their memories, they performed normally (see Figure 2B).32 This memory deficit was not restricted to spatial aspects of memories. Rather, deficits generalized to perceptual, emotional and referential details. Because this task did not require encoding, the patients' impoverished performance is best characterized as a memory retrieval deficit.

In another study, patients with left and right VPC lesions (see Figure 2C) and normal controls took part in a source memory test33. Participants heard pairs of stimuli, read by a female or a male voice. Later, they were required to recall and recognize the item associated with each stimulus, and to determine its source (i.e. male vs. female voice). Last, for each recognized pair, participants had to judge whether recognition of the pair elicited recollection or familiarity. Recollection refers to a sense of reliving the encoding context vividly, whereas familiarity refers to a sense that the event happened in the past, but without any information as to the circumstances and context of its occurrence.34 The results showed no impairment in cued recall, recognition and source memory in parietal patients compared to normal controls, indicating they were objectively able to access some aspects of the encoding context. However, compared to controls, patients were reluctant to classify their memories as recollected, suggesting that retrieval of contextual details did not trigger remembering states in these patients (see Figure 2D). One patient, SM, commented that despite objectively remembering things in real life, she always lacked confidence in her memories, as if she did not know where they had come from.

This evidence of impaired memory after parietal lobe damage must be tempered by several negative findings. In the study described above, unilateral parietal lobe damage was found to have no effect on source memory. In a similar vein, source memory was assessed in a group of patients whose unilateral parietal lobe lesions overlapped with regions found to be activated in an fMRI study by a source memory task and stimuli35. Again, the patients and controls had similar levels of source memory accuracy. Preliminary evidence shows that this finding cannot be attributed to compensation from the intact parietal lobe because patients with bilateral parietal lobe damage also exhibit intact source memory, whether tested with verbal or visual stimuli (Ingrid Olson, unpublished findings). Also, parietal patients may describe some autobiographical memories as recollected when they are allowed to select the memories by themselves. Even then, however, memories unique to the event are not as detailed as that of controls, suggesting that simple, subjective assessment of recollection may not be a sensitive enough measure when applied to complex and extended autobiographical events.33There is also evidence that parietal lobe dysfunction has no effect on item recognition memory. One study 36 found no impairment in recognition of words, pictures, and sounds in patients with left parietal lesions, and only a slight deficit in picture recognition in patients with right parietal lesions, which may have been attributable to extra-parietal damage. Likewise, another group37 reported that recognition memory was unaffected by temporary disruption of the intraparietal sulcus by application of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to this region during memory retrieval.

In summary, a review of the available data indicates that parietal lobe damage in some instances causes episodic memory impairments. We note that there are only a small number of studies and that future research may bring different evidence to bear on this topic. The deficits are most apparent when there is poor retrieval support. Thus, when patients with parietal lobe damage try to remember complex events, the events' contextual details do not spring to mind automatically32 and they do not trigger vivid remembering states.33 In tasks with better retrieval support, however, performance is normal: If appropriately probed, patients can access item information normally,33, 36 as well as source information,33, 35 and even multiple contextual features of complex events.32 It is tempting to conclude that the observed deficits point towards a general problem in top-down control. Indeed, memory deficits in frontal lobe patients have been described in a similar vein, thus explaining their proclivity to false-alarm and to insert non-stimulus materials into recollected memories. Neither of these problems is evident in PPC patients 32 suggesting that an alternative hypothesis must be sought.

Parietal activations during episodic retrieval

As noted above, the parietal cortex is one of the regions most frequently activated during episodic retrieval.2 The prominence of these activations was noted first in ERP studies1 and then in early PET studies38-40 but theoretical debates focused more on the role of the precuneus in mental imagery41, 42 than on the contributions of lateral parietal regions, which were considered mainly in relation to context memory for spatial43 and temporal44 information. Interest in the contributions of lateral parietal regions grew rapidly with the publication of the first crop of event-related fMRI studies of recognition memory, which typically compared neural activity for hits versus correct rejections.45-47 The resulting retrieval success activations were frequently found in lateral parietal cortex (see Figure 3A). Retrieval success activations fit very well with the results of event-related potential (ERP) studies of recognition memory, which typically find that, compared with correct rejections, hits are associated with positive potentials over parietal scalp regions around 300-600 ms post-stimulus.1 Interestingly, as recognition performance increases, retrieval success activations in left parietal cortex tend to become more ventral (see Figure 3B). In addition to retrieval success activations, event-related fMRI studies identified several other activation patterns in parietal cortex. For example, a group of studies found that certain parietal regions showed recollection-related activations, i.e., greater activity for recollection than for familiarity.48, 49

Figure 3.

Parietal activation patterns during episodic memory tasks A. Retrieval success activations in the parietal cortex (for the list of studies and coordinate, see supplementary materials online). Event-related fMRI studies that compare hits to correct rejections (CR) typically find activations in posterior parietal regions, including both DPC and VPC. B. Retrieval success activation in left parietal regions tend to become more ventral (smaller Z coordinate) as a function of recognition accuracy (d'). This finding is consistent with the AtoM model. C. Retrieval activation patterns. Retrieval success activity in the parietal cortex is defined as greater activity for hits than for correct rejections (CRs) Recollection-related activity is defined as greater activity for trials associated with recollection than with familiarity (e.g., greater activity for Remember than for Know trials in the Remember/Know paradigm95. Perceived oldness is defined as greater activity for or items classified as “old” than for items classified as “new”, regardless of whether these responses are correct or incorrect.50, 51. Recollection orienting is defined as greater activity source than for item memory tasks independently of the accuracy of responses (F).52-54

Although retrieval success and recollection-related activation patterns (see Figure 3C) suggest that parietal regions are directly involved in the recovery of episodic information, other activation patterns challenged this idea. First, a group of studies found that certain parietal regions showed a pattern known as perceived oldness (see Figure 3C), whereby activity is greater for items classified as “old” than for items classified as “new”, regardless of whether these responses are correct or incorrect.50, 51 This pattern suggests that parietal activity reflects a judgement that an item is old rather than the actual recovery of accurate information about the item. Second, another group of studies reported parietal activations showing a pattern known as recollective orienting (see Figure 3C), whereby parietal activity is greater for source memory tasks (where, when, how?) than for item memory tasks (what?) independently of the accuracy of responses.52-54 This finding suggests that parietal activity reflects the attempt to recollect information rather than recollection per se. These patterns challenge the idea that parietal regions are involved in retrieval success and recollection.

Parietal cortex and episodic retrieval: hypotheses

Three different hypotheses were proposed to account for the different parietal activation patterns observed in the neuroimaging studies.55 As illustrated in Table 1, each of these hypotheses can account for some, but not all available functional neuroimaging evidence. The output buffer hypothesis55 postulates that parietal regions contribute to holding retrieved information in a form accessible to decision-making processes, similarly to the working memory buffers proposed by Baddeley.56 In other words, parietal regions are assumed to help hold the qualitative content of retrieved information (such as mental images). The strongest support for this hypothesis is provided by the recollection-related activations because the retrieval of qualitative content is, by definition, greater for recollection than for familiarity. However, the output buffer hypothesis cannot easily explain the perceived oldness and recollective orienting patterns, as one would expect that activity associated with the recovery of memory contents should be greater for correct than incorrect trials.

Table 1.

Data and theory regarding parietal lobe involvement in episodic memory. The left column presents various findings, the right columns signify four hypotheses explaining the relationship between the parietal lobe and episodic memory. OBH= output buffer hypothesis, MAH = mnemonic accumulator hypothesis; AIRH = attention to internal representations hypothesis; AtoM = Attention to Memory model. + to +++ degree of fit, - poor fit. * DAP can account for these finding under the assumption that hit vs. CR and old vs. new contrasts are confounded by differences in top-down or bottom-up attention.

| Evidence (with representative studies) | OBH | MAH | AIRH | AtoM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parietal Lesions | ||||

| VPC lesions Impair spontaneous but not prompted autobiographical recall32 | - | - | - | +++ |

| VPC lesions impair the conscious experience of recollection94 | +++ | - | - | +++ |

| Parietal lesions do not impair episodic memory tests with few response alternatives, including source memory33,35 | - | - | + | + |

| Parietal activation patterns | ||||

| Retrieval success activations (hit > CR) activations45-47 | + | + | - | + |

| Recollection-related activations48,49 | +++ | + | - | +++ if VPC |

| Perceived oldness activations50,51 | - | +++ | - | + |

| Recollective orienting activations52-54 | - | - | +++ | +++ if DPC |

| Dorsal vs. ventral parietal activations | ||||

| Recollection is associated with VPC, familiarity is associated with DPC58,59 | +++ | - | - | +++ |

| High-confidence recognition is associated with VPC, low-confidence recognition is associated with DPC61,62 | +++ | - | - | +++ |

The mnemonic accumulator hypothesis55 posits that parietal regions do not help to hold actual memories but they temporally integrate a memory-strength signal to summarize information coming from other brain regions. Depending on whether the accumulated signal is above or below a criterion, “old”; or “new” recognition judgments are made, as described by signal-detection models of recognition memory.55 The strongest support for the mnemonic accumulator hypothesis is provided by perceived oldness activations, because the accumulation of an oldness signal would lead to an “old” response, regardless of the accuracy of the signal. This hypothesis can account for recollection-related activations under the assumption that recollected items are perceived as older than familiar items. However, this hypothesis cannot easily account for the recollective orienting pattern of findings showing that parietal activations may be associated with the intentions of the rememberer, rather than with the type of memory decision.

Finally, the attention to internal representation hypothesis55 states that parietal regions shift attention to, or maintain attention on, internally generated mnemonic representations. The strongest support for this hypothesis is provided by recollective orienting activations, which suggests that parietal regions track the intention to remember, that is, they direct voluntary attention to memory contents. However, voluntary attention cannot explain retrieval success, recollection-related, and perceived-oldness activations because the attempt to remember information is constant across the different conditions compared in these studies.

Although several authors have suggested that dorsal and ventral parietal regions play distinct roles in episodic retrieval,55, 57-59 none of the three hypotheses makes an explicit distinction between these regions. We believe that this distinction is crucial if we are to understand the contribution of the parietal lobes to episodic memory. A functional dissociation between these regions was observed in studies comparing recollection vs. familiarity. For example, VPC activity was found to be greater for items which participants classified as recollected than for items they classified as familiar, whereas DPC activity showed the opposite pattern (see Figure 4A)58. In this study, the recollection-related VPC activation was in the supramarginal gyrus but in other studies these activations extend posteriorly, towards the angular gyrus,60 and anteriorly, towards the temporo-parietal junction.59 Another kind of ventral-dorsal dissociation was found in studies that compared high vs. low confidence recognition responses.61, 62 For instance, VPC activity was reported to be greater for high than low confidence hits while the converse was true for DPC activity (see Figure 4B)61.

Figure 4.

Ventral-dorsal dissociations in activity. A. In an fMRI study of the Remember/Know paradigm,58 VPC showed greater activity for Remember than Know trials, whereas DPC showed the opposite pattern. B. In an fMRI study of confidence during recognition memory,61 VPC showed greater activity for high- than low-confidence hits whereas DPC showed greater activity for low- than high-confidence hits. C. Meta-analysis of parietal activity during episodic retrieval. The figure plots the peaks of activations in two kinds of event-related fMRI studies (for the list of studies and coordinate, see supplementary materials online). A first group of peaks is from studies that identified activity related to recollection or familiarity using the Remember/Know paradigm, distinguishing successful vs. unsuccessful source memory retrieval, or comparing the retrieval of items encoded under deep vs. shallow study tasks. A second group of peaks is from studies that investigated recognition confidence. In general, recollection and high-confidence recognition were associated with VPC activations, whereas familiarity and low-confidence recognition were associated with DPC activations. (Image A was adapted from ref.58, Image B was adapted from ref.61)

To investigate the consistency of these dissociations, we can compare, across studies, activations associated with recollection vs. those associated with familiarity, and those associated with high-confidence decisions vs. those associated with low-confidence decisions. As illustrated by Figure 4C, with a few exceptions, familiarity and low-confidence activations tend to be more frequent in the DPC (BA 7), whereas recollection and high-confidence activations tend to more frequent in the VPC (BAs 40 and 39). The former activations occur mainly in or above IPS, while the latter occur mainly in the angular and supramarginal gyri extending into the temporo-parietal junction. These data converge with the results of other meta-analyses57, 63 in supporting the idea that the DPC and VPC play different roles in episodic memory retrieval. However, to clarify the specific contribution of these two regions in episodic retrieval, one needs to identify a cognitive process that is shared by familiarity and low-confidence recognition, and one that is shared by recollection and high-confidence recognition. To identify these processes, it helps to take a brief detour outside the episodic memory domain, and consider the role of parietal regions in attention.

Parietal cortex and attention

As noted above, attention is one of the cognitive functions traditionally associated with posterior parietal regions.24 Several of the cognitive deficits associated with parietal lobe lesions, including neglect and simultanagnosia, may be described as attention deficits. Recent evidence suggests that the DPC and VPC play different roles in attention. A recent attention model proposes that the DPC, together with dorsal frontal regions, is associated with top-down attention, whereas the VPC, together with ventral frontal regions, is associated with bottom-up attention21. The dorsal attention system is involved in “preparing and applying goal-directed selection for stimuli and responses”, whereas the ventral attention system is involved in the "detection of behaviorally relevant stimuli, particularly when they are salient and unexpected”.

The notion that the DPC and VPC play different roles in attention is supported by functional neuroimaging and lesion evidence.21 For example, one fMRI study using a visual search paradigm found that DPC activity began as soon as the search instructions were given and continued throughout the search period, whereas VPC activity was greater than DPC activity when the target was detected.64 Thus, DPC activity mediates preparatory top-down attention, whereas VPC activity is associated with the capture of bottom-up attention by behaviourally relevant stimuli. Activity associated with bottom-up attention can also be captured by using unexpected (spatial and nonspatial) stimuli.65-70. When an relevant stimulus appears that was out of the current attentional focus, the VPC sends a “circuit breaker” signal to DPC, which shifts attention to the previously unattended stimulus.71. The right VPC is also the most frequent location of lesions causing neglect, which may be described as a deficit in bottom-up attention: neglect patients can voluntarily direct attention to the contralesional side and can use cognitive cues to anchor attention to the left visual space, but they have a deficit in detecting stimuli that are outside the focus of ongoing processing.21

Parietal cortex, attention, and episodic memory

Could the distribution of episodic retrieval activations in Figure 4C be associated with the allocation of top-down and bottom-up attention to memory by the DPC and VPC, respectively? The main problem with this theory seems to be that bottom-up attention is typically defined as attention driven by sensory stimuli (that is, “exogenous attention”), whereas memory retrieval is primarily concerned with internally-generated information. However, if one defines bottom-up attention as attention driven by incoming information, regardless of its source, then it is clear that bottom-up attention plays an important role in episodic memory. The most obvious example of bottom-up attention driven by episodic memory is involuntary remembering, as in the case of the Proustian character who experienced an outpouring of autobiographical memories following the taste of a teasoaked Madeleine. However, the phenomenon of memory-guided bottom-up attention is not limited to involuntary personal memories; it occurs whenever an interesting memory enters consciousness and takes over attentional resources.

Thus, extending the distinction between top-down and bottom-up attention to the episodic memory domain, we propose that the DPC is associated with the allocation of attentional resources to memory retrieval according to the goals of the rememberer (top-down attention), whereas the VPC is associated with the capture of attentional resources by relevant memory cues and/or recovered memories (bottom-up attention).72, 73 We call this idea Attention to Memory (AtoM) Model. According to this model, DPC activity maintains retrieval goals, which modulate memory-related activity in the medial temporal lobe (MTL), whereas VPC activity, like a “circuit breaker”, signals the need for a change in the locus of attention following detection of relevant memories retrieved via the MTL. Because VPC activity reflects the attentional adjustments triggered by the products of ongoing MTL activity, it fluctuates continuously over time, as illustrated by Figure 5. According to the AtoM model, VPC detects relevant information generated by MTL but it does not hold or accumulate this information, as proposed by the output buffer and mnemonic accumulator hypotheses.

Figure 5.

Simple graphical description of the Attention to Memory (AtoM) model. Activity in the VPC fluctuates continuously, tracking changes in MTL activity, which in turn reflects the recovery of episodic memories. In contrast, activity in theDPC reflects top-down attentional processes guided by retrieval goals. For example, an earlier segment of the incoming signal may be more relevant to behavioral goals than a later segment. The DPC and VPC interact very closely: the goals maintained by DPC define which targets are relevant, and the targets detected by VPC can alter or change behavioral goals. The attentional processes VPC and DPC contribute to episodic retrieval are the same attentional processes these regions contribute to perception (e.g., dotted arrows in the case of visual attention). (Figure is from ref.72)

Thus, according to the AtoM model, the roles of DPC and VPC in episodic retrieval are largely the same as their respective roles in attention. Bottom-up capture of attention by memory occurs when information is retrieved that is relevant to the current task. On the other hand, top-down attention to memory is necessary when the memory decision is effortful, and therefore attention-demanding pre- and post-retrieval processing is needed to emit the memory judgment. Thus, the AtoM model can explain very well why the VPC and DPC are differentially involved in high vs. low-confidence recognition and in recollection vs. familiarity (see Figure 4). High-confidence hits tend to occur when a great deal of information is rapidly retrieved from memory, which is likely to capture attention bottom-up, engaging the VPC. In contrast, low-confidence hits tend to occur when recovery is poor, requiring an effortful memory search and top-down attention processes that engage DPC. Similar ideas explain differential involvement of the VPC and DPC in recollection vs. familiarity. Recollection involves the spontaneous retrieval of episodic details, which capture bottom-up attentional resources and engage the VPC, whereas familiarity involves more difficult decisions that are more dependent on top-down control and DPC functions. Given that recollection increases with accuracy, the AtoM model is also consistent the data in Figure 3B. The AtoM model can also explain why a study that directly compared an episodic retrieval task to a top-down attention task found overlaps in the DPC but not in VPC.74

Top-down attention and bottom-up attention are two separate dimensions rather than the end points of a single dimension. As illustrated by the phenomenon of involuntary memories, memory detection can occur independently of whether it was preceded by the deployment of top-down attention to memory. Conversely, top-down attention to memory can be triggered even after memory detection has happened, if the retrieved memory does not satisfy some criteria. Thus, even if in some situations they tend to vary in opposite directions (for example in high vs. low confidence hits), top-down and bottom-up attention to memory are independent processes.

The model predicts that top-down and bottom-up attention processing interact very closely during episodic retrieval (see Figure 5), just as they do during perception. In a typical retrieval situation, the intention to remember (for example, where did I park the car?) initiates a memory search guided by top-down attentional processes mediated by the DPC, and the recovered memories (such as the image of the car in the north end of the parking lot) grab bottom-up attentional resources mediated by the VPC. However, because of their close interaction, the distinction between the attentional functions of DPC and VPC is graded rather than sharp. First, because the VPC responds only to relevant stimuli, this region is indirectly sensitive to the behavioral goals that determine the relevancy of stimuli. fMRI studies of attention have shown that the VPC does not responds to all salient stimuli but only to those that share modality66 or other perceptual features75 with the target. Likewise, while searching memory for a parking location, VPC-mediated bottom-up attentional resources are more likely to be captured by spatial images than by memories of words or sounds. Second, because the goals processed by DPC are constantly updated, this region is indirectly sensitive to target detection. fMRI studies of attention have shown that DPC activity starts while the target is being searched but it falls off soon after the target is detected.76 In the case of memory, one would also expect the success or failure in detecting the target leads to a change in the goals being processed by the DPC. Thus, because the DPC and VPC interact very closely, one is more likely to find graded differences than sharp dissociations between the contributions of these regions to episodic retrieval.

Because the AtoM model postulates that the role of parietal cortex in episodic memory is related to attention, this hypothesis can explain why inferior parietal lesions do not yield dramatic episodic memory deficits but, instead, produce subtle effects under certain conditions. In general, attention enhances cognitive processes but is not essential for these processes; when attention fails, cognitive operations are weakened but they are not completely obliterated. In the case of vision, for example, attention deficits may produce neglect but they do not normally lead to blindness.30 For the same reason, the effect of attention deficits on episodic memory should not be expected to yield amnesia. Thus, the AtoM model can explain why parietal lesions do not yield reliable deficits in episodic retrieval tests that provide specific probes about to-be-remembered stimuli. 35, 36, 37 In contrast, significant episodic retrieval deficits are more likely to occur in open-ended tasks, such as spontaneous recall of autobiographical events32 or the introspective evaluation of recovered memories.33 At any rate, the number of studies on the effects of parietal lesions is currently too small to reach definite conclusions.

If the contributions of parietal regions to episodic retrieval are attributed to their role in attention, then the effects of parietal damage on episodic memory should resemble the neglect syndrome. This hypothetical syndrome may be called “memory neglect”.72 The characteristics of memory neglect may be inferred from the characteristics of visual neglect, with the exception of differences between left and right hemi-space, which are not part of our memory neglect concept. Neglect patients typically have VPC damage and show a deficit in bottom-up attention: they have a deficit in detecting stimuli spontaneously but can voluntarily direct attention to stimuli in the neglected hemifield.21 By analogy, the AtoM model predicts that VPC lesions should yield a memory neglect deficit whereby patients cannot spontaneously report relevant details in retrieved memories (bottom-up attention) but can access these details if guided by specific questions (top-down attention). This is exactly what was found:32 patients who had mostly VPC damage were impaired in spontaneous autobiographical recall but they were normal when asked specific questions about their memories (see Figure 2B). In other words, memories are intact but they do not capture bottom-up attention by themselves. This idea can also explain the dissociation 33 between preserved source memory and impaired recollection deficits displayed by VPC patients (see Figure 2D): contextual details of encoding are available to patients but they do not pop-out spontaneously at retrieval, and therefore cannot inform Remember decisions. An alternative interpretation of these findings is that VPC patients have difficulty in retrieving multiple details of memory simultaneously, a deficit that could be termed memory simultanagnosia. This can explain why parietal lesions may not impair episodic retrieval in tasks that focus participants' attention on a single dimension of the stimuli.32, 35 Distinguishing between memory neglect and memory simultanagnosia will require specifically-designed studies, but both ideas are consistent with the AtoM model because both assume that the essential mnemonic deficit after VPC damage is in bottom-up attention to internal representations.

Open questions

Although available evidence supports the idea that the contributions of parietal regions to episodic retrieval can be explained by the distinction between top-down and bottom-up attentional processes, there are many open questions for future research. One group of questions involves left-right and anterior-posterior distribution of activation in episodic retrieval and attention fMRI studies. VPC activations related to bottom-up attention tend to be stronger in the left hemisphere in episodic retrieval studies,57 but in the right hemisphere in perceptual attention studies.21 This is not a serious problem for the AtoM model because perceptual attention studies often find bilateral VPC activations.65-69. Because episodic retrieval studies tend to use meaningful verbal stimuli whereas attention studies tend to use meaningless perceptual materials, it is possible that lateralization differences reflect differences in stimuli77 rather than processes. Regarding anterior-posterior distribution, VPC activations in episodic retrieval studies often extend posteriorly towards the angular gyrus,57 whereas in perceptual attention studies, they often extend anteriorly and ventrally towards the superior temporal gyrus (temporo-parietal junction).21 However, there are several examples of episodic retrieval activations in anterior VPC48, 59 and attention activations in posterior VPC64, 78, 79, and the two distributions show substantial overlap in the supramarginal gyrus. At any rate, further research on the localization of parietal activations during episodic retrieval and perceptual attention tasks is warranted.

Another open question is the relation between parietal and frontal regions. According to the model of attentional systems described above,21 the top-down attention system involves not only the DPC but also dorsal frontal regions, and the bottom-up attention system involves not only the VPC but also ventral frontal regions. Could this also be the case for episodic retrieval? It is not difficult to find examples supporting this idea. In the data shown in Figure 4B, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex activity was greater for low than high confidence recognition hits.61 The involvement of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in low confidence recognition has been also found in other fMRI studies80, 81. Although the model of attentional systems links top-down attention to the frontal eye fields, rather than the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. it is possible that the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex plays a more important role for nonspatial stimuli. Turning to bottom-up attention, several fMRI studies have reported activations in ventrolateral prefrontal cortex regions as a function of the amount of information recovered from episodic and semantic memory82, 83. At any rate, the literature on prefrontal cortex activity during episodic retrieval is large and complex, and reviewing it is beyond the scope of this article. A reasonable conclusion at this point is that it is not implausible that the AtoM model could be extended to include frontal regions.

Summary

The posterior parietal cortex has long been known to be crucial for attention during perception and mental representation of location, but it was rarely, if ever, implicated in memory retrieval. The advent of functional neuroimaging, however, showed clearly that the posterior parietal cortex often was activated during memory retrieval. In this paper we review this evidence and argue that the pattern of parietal activation that is observed during memory retrieval parallels its role in directing attention during perception. Just as the superior parietal cortex is involved in the voluntary allocation of attention during perception, so this region is associated with top-down (voluntary) processes supporting retrieval search, monitoring and verification. By contrast, activation of the inferior parietal cortex is found when the output of such processes leads to a clear, unambiguous outcome, as occurs especially in recollection. This is similar to the inferior parietal activation that is associated with the exogenous capture of attention by a salient stimulus in perception. The findings in the few studies on memory retrieval in people with parietal lobe lesions are consistent with these observations. On this basis, we proposed a dual process model of attention to memory (AtoM), assigning different roles to the superior and inferior parietal cortex, as indicated above. Other models have also been proposed, but each, including our own, has limitations. The emergence of these models will stimulate investigation and lead not only to a better understanding of how attention and memory interact, but also, it is hoped, to a unified theory of attention that is applicable to all domains.

Box 1. VPC: Bottom-up Attention or Episodic Buffer?

A recent version of the output buffer hypothesis proposes that the VPC is the site of the episodic buffer,57 a component of Baddeley's working memory model specialized for maintaining integrated multi-modal information.84 Both this hypothesis and the AtoM model can explain why VPC activity during episodic retrieval tends to increase as a function of recollection and confidence. According to the episodic buffer hypothesis, recollected and high-confidence trials involve the retrieval of greater amounts of integrated multi-modal information, which must be maintained by the episodic buffer. According to the AtoM model, these trials are more likely to capture bottom-up attentional resources and enter consciousness. Both hypotheses can account equally well for evidence that VPC lesions impair recollection.33 However, the episodic buffer model cannot explain why VPC lesions impair spontaneous but not prompted autobiographical recall32 or source memory.33, 35 If the VPC is the site of the episodic buffer, one would expect that VPC damage should impair episodic memory in all conditions.

The AtoM model can also explain the finding that VPC activity shows greater activity for both “definitely old” and “definitely new” items than for low-confidence recognition responses, as shown in the figure (A was adapted from ref. 60, B was adapted from ref. 59). To account for these findings, the episodic buffer hypothesis would need to postulate a recall-to-reject strategy, in which the correct item is first recalled and compared the incorrect target,59 but such a strategy is unlikely during item recognition.85 In contrast, the AtoM model can accommodate strong VPC responses to both “definitely new” and “definitely old“ trials because these are the trials most relevant to the test, and hence, the most likely to capture bottom-up attention.

Box 2. Attention and Direct vs. Indirect Episodic Retrieval

It may seem surprising to learn that distraction has a much less detrimental effect on memory retrieval than it does on encoding. To understand this finding, it is necessary to distinguish between direct and indirect retrieval.86, 87 During direct retrieval, a cue interacts automatically with information stored in memory. Direct retrieval is mediated by the MTL and requires few attentional resources. In contrast, during indirect retrieval, the target memory is not automatically elicited by the cue, and has to be recovered through a strategic search process. Indirect retrieval is mediated by the prefrontal cortex and is attentionally demanding. Accordingly, indirect retrieval is impaired by the performance of a concurrent task,88-90 whereas direct retrieval is not.Nevertheless, direct retrieval does inflict costs on the distracting task,e.g., 91, 92 suggesting that, even when mandatory, episodic memory retrieval usurps attentional resources from ongoing processes.

According to the AtoM model, indirect retrieval depends on top-down attention mediated by the DPC, which is connected to PFC regions controlling attention and strategic retrieval.93 Consequently, directing attention away from the memory task will deprive it of the neural mechanisms needed for strategic retrieval. By contrast, direct retrieval depends on bottom-up attention processes mediated by the VPC, which has strong links to MTL.20 Judging from the behavioural results, the MTL seems to have privileged access to VPC, such that attention is directed away from salient events in the environment during direct retrieval. Why that should be the case is not known. Perhaps once a retrieval mode is entered, the system is set so that the VPC is biased to favour information from the MTL as compared to information from posterior neocortical structures involved in perception. Alternatively, it may be the case that the brain is so organized that connections from MTL to VPC are stronger than those from perceptual structures, and always compete effectively against them. Resolution of these issues awaits results from behavioural, neuroimaging and lesion studies.

Box 1 Figure.

VPC activity shows a U-shaped response as a function of oldness

Glossary Terms

- Episodic memory

Memory for personally experienced past events.

- Medial temporal lobe (MTL)

Structures in the medial part of the temporal lobe, including regions critical for declarative memory function such as the hippocampus and the parahippocampal gyrus.

- Event-related fMRI

fMRI designs in which neural activity during specific trial types is extracted and averaged. These designs allow contrasts between trials associated with different behavioral responses, such as successful vs. unsuccessful retrieval trials.

- Hemispatial neglect

A neurological disorder characterized by impaired awareness of the contralesional side of the external world, one's own body, and even internal representations.

- Balint's syndrome

A neurological syndrome, caused by bilateral damage of posterior parietal and lateral occipital cortex, that has three hallmark symptoms: simultanagnosia, optic ataxia, and oculomotor apraxia.

- Retrograde amnesia

Loss of or inability to remember information that was previously stored in long-term memory.

- Anterograde amnesia

The inability to store new information into long-term memory.

- Autobiographical memory

Memory for one's personal past, such as memory for one's birthday party.

- Source memory

Memory for the context in which an item or event was previously encountered.

- Item recognition memory

Deciding whether or not an item (e.g., a word) was previously encountered.

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS)

A technique in which a strong magnetic field is applied to the scalp, disrupting the function of a cortical area on the other side of the cranium. If ongoing cognitive performance is impaired, the affected cortical area can be assumed to be necessary for the task.

- Mental imagery

the visualization of images in the mind's eye in the absence of a stimulus.

- Hits

correctly recognized old items.

- Correct rejections

correctly recognized new items.

- Signal-detection models of recognition memory

These models assume that items in a recognition memory test vary in memory strength (degree of certainty that the items were previously encountered). Although memory strength is on average greater for old items than for new items, the two distributions overlap. When memory strength exceeds a certain criterion the item is classified as old; otherwise, it is classified as new.

- Top-down attention

attention guided by goals.

- Bottom-up attention

attention guided by incoming sensory information.

- Visual search paradigm

an attention task requiring to find a target (e.g., the letter “F”) hidden among distractors (e.g., many instances of the letter “E”).

- Bottom-up attention according to AtoM

attention driven by incoming information, regardless of whether the information comes from the senses or from memory.

- Memory neglect

Hypothetical syndrome associated with a deficit in spontaneously detecting details in retrieved memories (impaired bottom-up attention) but preserved ability to search and find these details when guided by specific goals (spared top-down attention).

- Memory Simultanagnosia

Hypothetical syndrome associated with a difficulty in retrieving multiple details of memory simultaneously.

References

- 1.Rugg MD. In: The Cognitive Neurosciences. Gazzaniga MS, editor. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1995. pp. 789–801. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cabeza R, Nyberg L. Imaging Cognition II: An empirical review of 275 PET and fMRI studies. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2000;12:1–47. doi: 10.1162/08989290051137585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudge P, Warrington EK. Selective impairment of memory and visual perception in splenial tumours. Brain. 1991;114(Pt 1B):349–60. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.1.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valenstein E, et al. Retrosplenial amnesia. Brain. 1987;110:1631–1646. doi: 10.1093/brain/110.6.1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Von Cramon DY, Schuri U. The septo-hippocampal pathways and their relevance to human memory: a case report. Cortex. 1992;28:411–422. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(13)80151-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cavada C, Goldman-Rakic PS. Posterior parietal cortex in rhesus monkey: II. Evidence for segregated corticocortical networks linking sensory and limbic areas with the frontal lobe. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1989;287:422–45. doi: 10.1002/cne.902870403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis JW, Van Essen DC. Corticocortical connections of visual, sensorimotor, and multimodal processing areas in the parietal lobe of the macaque monkey. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2000;428:112–137. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001204)428:1<112::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petrides M, Pandya DN. Projections to the frontal cortex from the posterior parietal region in the rhesus monkey. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1984;228:105–116. doi: 10.1002/cne.902280110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petrides M, Pandya DN. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex: comparative cytoarchitectonic analysis in the human and the macaque brain and corticocortical connection patterns. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;11:1011–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmahmann JD, et al. Association fibre pathways of the brain: parallel observations from diffusion spectrum imaging and autoradiography. Brain. 2007;130:630–53. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobayashi Y, Amaral DG. Macaque monkey retrosplenial cortex: II. Cortical afferents. J Comp Neurol. 2003;466:48–79. doi: 10.1002/cne.10883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris R, Pandya DN, Petrides M. Fiber system linking the mid-dorsolateral frontal cortex with the retrosplenial/presubicular region in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1999;407:183–92. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990503)407:2<183::aid-cne3>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blatt GJ, Pandya DN, Rosene DL. Parcellation of cortical afferents to three distinct sectors in the parahippocampal gyrus of the rhesus monkey: an anatomical and neurophysiological study. J Comp Neurol. 2003;466:161–79. doi: 10.1002/cne.10866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clower DM, West RA, Lynch JC, Strick PL. The inferior parietal lobule is the target of output from the superior colliculus, hippocampus, and cerebellum. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:6283–6291. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-06283.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Insausti R, Munoz M. Cortical projections of the non-entorhinal hippocampal formation in the cynomolgus monkey (macaca fascicularis) European Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;14:435–451. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lavenex P, Suzuki WA, Amaral DG. Perirhinal and parahippocampal cortices of the macaque monkey: projections to the neocortex. J Comp Neurol. 2002;447:394–420. doi: 10.1002/cne.10243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munoz M, Insausti R. Cortical efferents of the entorhinal cortex and the adjacent parahippocampal region in the monkey (macaca fascicularis) European Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;22:1368–1388. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04299.x. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rockland KS, Van Hoesen GW. Some temporal and parietal cortical connections converge in CA1 of the primate hippocampus. Cerebral Cortex. 1999;9:232–237. doi: 10.1093/cercor/9.3.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzuki WA, Amaral DG. Perirhinal and parahippocampal cortices of the macaque monkey: cortical afferents. J Comp Neurol. 1994;350:497–533. doi: 10.1002/cne.903500402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vincent JL, et al. Coherent spontaneous activity identifies a hippocampal-parietal memory network. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:3517–31. doi: 10.1152/jn.00048.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corbetta M, Shulman GL. Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2002;3:201–215. doi: 10.1038/nrn755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article introduces an influential cognitive neuroscience model of attention that distinguishes between dorsal fronto-parietal system mediating top-down attention and a ventral fronto-parietal system mediating bottom-up attention. The AtoM model proposed in this article extends the dorsal/ventral distinction within parietal cortex to the episodic retrieval domain.

- 22.Milner AD, Goodale MA. The visual brain in action. Oxford University Press; Oxford; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mishkin M, Ungerleider LG, Macko KA. Object vision and spatial vision - 2 cortical pathways. Trends in Neurosciences. 1983;6:414–417. 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Posner MI, Petersen SE. The attention system of the human brain. Annual Review of Neurosciences. 1990;13:25–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.13.030190.000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bisiach E, Luzzatti C. Unilateral Neglect of Representational Space. Cortex. 1978;14:129–133. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(78)80016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Danckert J, Ferber S. Revisiting unilateral neglect. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:987–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Driver J, Vuilleumier P. Perceptual awareness and its loss in unilateral neglect and extinction. Cognition. 2001;79:39–88. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(00)00124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vallar G. Spatial hemineglect in humans. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 1998;2:87–97. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(98)01145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pavani F, Ladavas E, Driver J. Auditory and multisensory aspects of visuospatial neglect. Trends Cogn Sci. 2003;7:407–414. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(03)00189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Driver J, Mattingley JB. Parietal neglect and visual awareness. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:17–22. doi: 10.1038/217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Critchley M. The parietal lobes. Edward Arnold; London: 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berryhill ME, Phuong L, Picasso L, Cabeza R, Olson IR. Parietal lobe and episodic memory: Bilateral damage causes impaired free recall of autobiographical memory. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:14415–14423. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4163-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study reports the first evidence of significant deficits in episodic memory retrieval following parietal lesions. Consistent with the AtoM model, patients with bilateral ventral parietal lesions showed a deficit in spontaneously reporting details in their autobiographical memories but could provide these details when probed.

- 33.Davidson PSR, et al. Does lateral parietal cortex support episodic memory? Evidence from focal lesion patients. Neuropsychologia. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study demonstrates that patients with unilateral parietal lesions show deficits in experiencing recollection, even when they show normal source memory performance when tested with specific probes. This pattern is consistent with the AtoM model.

- 34.Yonelinas AP. The nature of recollection and familiarity: A review of 30 years of research. Journal of Memory and Language. 2002;46:441–517. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simons JS, et al. Is the parietal lobe necessary for recollection in humans? Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:1185–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study shows that unilateral parietal lesions, which overlap with regions activated during source memory tasks, do not significantly impair source memory performance.

- 36.Haramati S, Soroker N, Dudai Y, Levy DA. The posterior parietal cortex in recognition memory: A neuropsychological study. Neuropsychologia. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study investigated patients with lesions that included parietal cortex. Patients with left hemisphere lesions were not impaired in recognition memory for words, pictures, and sounds.

- 37.Rossi S, et al. Prefrontal and parietal cortex in human episodic memory: an interference study by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:793–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study failed did not find a significant effect of TMS stimulation on episodic retrieval performance.

- 38.Kapur S, et al. Functional role of the prefrontal cortex in retrieval of memories: A PET study. Neuroreport. 1995;6:1880–1884. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199510020-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tulving E, et al. Neuroanatomical correlates of retrieval in episodic memory: Auditory sentence recognition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1994;91:2012–2015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schacter DL, Alpert NM, Savage CR, Rauch SL, Albert MS. Conscious recollection and the human hippocampal formation: evidence from positron emission tomography. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:321–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fletcher PC, et al. The mind's eye—Precuneus activation in memory related imagery. Neuroimage. 1995;2:195–200. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1995.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buckner RL, Raichle ME, Miezin FM, Petersen SE. PET studies of the recall of pictures and words from memory. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 1995;21:1441. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moscovitch M, Kapur S, Köhler S, Houle S. Distinct neural correlates of visual long-term memory for spatial location and object identity: A positron emission tomography (PET) study in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1995;92:3721–3725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cabeza R, et al. Brain regions differentially involved in remembering what and when: a PET study. Neuron. 1997;19:863–70. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80967-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buckner RL, et al. Functional-anatomic study of episodic retrieval: II. Selective averaging of event-related fMRI trials to test the retrieval success hypothesis. Neuroimage. 1998;7:163–175. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Konishi S, Wheeler ME, Donaldson DI, Buckner RL. Neural correlates of episodic retrieval success. Neuroimage. 2000;12:276–286. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rugg MD, Henson RNA. In: The cognitive neuroscience of memory encoding and retrieval. Parker AE, Wilding EL, Bussey T, editors. Psychology Press; Hove: 2002. pp. 3–37. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eldridge LL, Knowlton BJ, Furmanski CS, Bookheimer SY, Engle SA. Remembering episodes: a selective role for the hippocampus during retrieval. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3:1149–1152. doi: 10.1038/80671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Henson RNA, Rugg MD, Shallice T, Josephs O, Dolan RJ. Recollection and familiarity in recognition memory: an event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:3962–72. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-03962.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wheeler MA, Buckner RL. Functional dissociation among components of remembering: Control, perceived oldness, and content. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:3869–3880. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-09-03869.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article introduces the perceived oldness hypothesis of parietal contributions to episodic retrieval.

- 51.Kahn I, Davachi L, Wagner AD. Functional-neuroanatomic correlates of recollection: implications for models of recognition memory. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4172–80. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0624-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dobbins IG, Foley H, Schacter DL, Wagner AD. Executive control during episodic retrieval: multiple prefrontal processes subserve source memory. Neuron. 2002;35:989–96. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00858-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dobbins IG, Rice HJ, Wagner AD, Schacter DL. Memory orientation and success: Separable neurocognitive components underlying episodic recognition. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41:318–333. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dobbins IG, Wagner AD. Domain-general and Domain-sensitive Prefrontal Mechanisms for Recollecting Events and Detecting Novelty. Cereb Cortex. 2005 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wagner A, Shannon B, Kahn I, Buckner R. Parietal lobe contributions to episodic memory retrieval. Trends Cogn Sci. 2005;9:445–53. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article reviews fMRi evidence and theoretical accounts about role of parietal cortex in episodic retrieval.

- 56.Baddeley A. Working memory: looking back and looking forward. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:829–39. doi: 10.1038/nrn1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vilberg KL, Rugg MD. Memory retrieval and the parietal cortex: a review of evidence from event-related fMRI. Neuropsychologia. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article includes a metaanalysis of fMRI activations during episodic retrieval and attributes the role of ventral parietal cortex to a working memory module known as the episodic buffer.

- 58.Wheeler ME, Buckner RL. Functional-anatomic correlates of remembering and knowing. Neuroimage. 2004;21:1337–49. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Using the Remember/Know paradigm, this fMRI study demonstrated that recollection engages ventral parietal regions, whereas familiarity engages more dorsal parietal regions.

- 59.Yonelinas AP, Otten LJ, Shaw KN, Rugg MD. Separating the brain regions involved in recollection and familiarity in recognition memory. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3002–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5295-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Daselaar SM, Fleck MS, Cabeza RE. Triple Dissociation in the Medial Temporal Lobes: Recollection, Familiarity, and Novelty. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:1902–1911. doi: 10.1152/jn.01029.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim H, Cabeza R. Trusting our memories: Dissociating the neural correlates of confidence in veridical vs. illusory memories. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:12190–12197. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3408-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moritz S, Glascher J, Sommer T, Buchel C, Braus DF. Neural correlates of memory confidence. Neuroimage. 2006;33:1188–93. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Skinner EL, Fernandes MA. Neuroal correlates of recollection and familiarity: A review of neuroimaging and patient data. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:2163–2179. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Corbetta M, Kincade JM, Ollinger JM, McAvoy MP, Shulman GL. Voluntary orienting is dissociated from target detection in human posterior parietal cortex. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3:292–297. doi: 10.1038/73009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clark VP, Fannon S, Lai S, Benson R, Bauer L. Responses to rare visual target and distractor stimuli using event-related fMRI. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2000;83:3133–9. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.5.3133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Downar J, Crawley AP, Mikulis DJ, Davis KD. A multimodal cortical network for the detection of changes in the sensory environment. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3:277–83. doi: 10.1038/72991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Downar J, Crawley AP, Mikulis DJ, Davis KD. The effect of task relevance on the cortical response to changes in visual and auditory stimuli: an event-related fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2001;14:1256–67. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kiehl KA, Laurens KR, Duty TL, Forster BB, Liddle PF. Neural sources involved in auditory target detection and novelty processing: An event-related fMRI study. Psychophysiology. 2001;38:133–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marois R, Leung HC, Gore JC. A stimulus-driven approach to object identity and location processing in the human brain. Neuron. 2000;25:717–28. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Braver TS, Barch DM, Gray JR, Molfese DL, Snyder A. Anterior cingulate cortex and response conflict: effects of frequency, inhibition and errors. Cerebral Cortex. 2001;11:825–36. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.9.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Corbetta M, Patel G, Shulman GL. The reorienting system of the human brain: from environment to theory of mind. Neuron. 2008;58:306–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cabeza R. Role of posterior parietal regions in episodic memory retrieval: The dual attentional processes hypothesis. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:1813–1827. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ciaramelli E, Grady CL, Moscovitch M. Cueing and detecting memory: A hypothesis on the role of the posterior parietal cortex in memory retrieval. Neuropsychologia. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cabeza R, et al. Attention-related activity during episodic memory retrieval: A cross-function fMRI study. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41:390–399. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Serences JT, et al. Coordination of voluntary and stimulus-driven attentional control in human cortex. Psychol Sci. 2005;16:114–22. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.00791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shulman GL, Ollinger JM, Linenweber M, Petersen SE, Corbetta M. Multiple neural correlates of detection in the human brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:313–318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.021381198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Milner B. Interhemispheric differences in the localization of psychological processes in man. British Medical Bulletin. 1971;27:272–277. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a070866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Arrington CM, Carr TH, Mayer AR, Rao SM. Neural mechanisms of visual attention: Object-based selection of a region in space. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2000;12:106–117. doi: 10.1162/089892900563975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kincade JM, Abrams RA, Astafiev SV, Shulman GL, Corbetta M. An event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging study of voluntary and stimulus-driven orienting of attention. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:4593–4604. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0236-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Henson RNA, Rugg MD, Shallice T, Dolan RJ. Confidence in recognition memory for words: Dissociating right prefrontal roles in episodic retrieval. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2000;12:913–923. doi: 10.1162/08989290051137468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fleck MS, Daselaar SM, Dobbins IG, Cabeza R. Role of prefrontal and anterior cingulate regions in decision-making processes shared by memory and nonmemory tasks. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16:1623–30. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Prince SE, Tsukiura T, Daselaar SM, Cabeza R. Distinguishing the neural correlates of episodic memory encoding and semantic memory retrieval. Psychological Science. 2007 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Thompson-Schill SL, D. Esposito M, Aguirre GK, Farah MJ. Role of left inferior prefrontal cortex in retrieval of semantic knowledge: a reevaluation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:14792–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Baddeley A. The episodic buffer: a new component of working memory? Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2000;4:417–423. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01538-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rotello CM, Heit E. Two-process models of recognition memory: Evidence for recall-to-reject? Journal of Memory and Language. 1999;40:432–453. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Moscovitch M. Memory and working-with-memory: A component process model based on modules and central systems. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1992;4:257–267. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1992.4.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Moscovitch M. In: Memory systems. Schacter DL, Tulving E, editors. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1994. pp. 269–310. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jacoby LL, Woloshyn V, Kelley CM. Becoming famous without being recognized: unconscious influences of memory produced by divided attention. journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1989;118:115–125. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kane MJ, Engle RW. Working-memory capacity, proactive interference, and divided attention: limits on long-term memory retrieval. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 2000;26:336–58. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.26.2.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Moscovitch M. Cognitive resources and dual-task interference effects at retrieval in normal people: The role of the frontal lobes and medial temporal cortex. Special Section: Working memory. Neuropsychology. 1994;8:524–534. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Craik FIM, Govoni R, Naveh-Benjamin M, Anderson ND. The effects of divided attention on encoding and retrieval processes in human memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1996;125:159–80. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.125.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fernandes MA, Moscovitch M. Divided attention and memory: evidence of substantial interference effects at retrieval and encoding. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2000;129:155–76. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.129.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fox MD, Corbetta M, AZ S, JL V, ME R. Spontaneous neuronal activity distinguishes human dorsal and ventral attention systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604187103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Davidson PS, Glisky EL. Neuropsychological correlates of recollection and familiarity in normal aging. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2002;2:174–86. doi: 10.3758/cabn.2.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tulving E. Memory and consciousness. Canadian Psychology. 1985;25:1–12. [Google Scholar]