Abstract

Motivation for change has historically been viewed as the crucial element affecting responsiveness to drug treatment. Various external pressures, such as legal coercion, may engender motivation in an individual previously resistant to change. Dramatic relief may be the change process that is most salient as individuals internalize such external pressures. Results of structural equation modeling on data from 465 drug users (58.9% male; 21.3% Black, 34.2% Hispanic/Latino, and 35.1% White) entering drug treatment indicated that internal motivation and external pressure significantly and positively predicted dramatic relief and that dramatic relief significantly predicted attitudes towards drug treatment: χ2=142.20, df=100, p<0.01; Robust Comparative Fit Index=0.97, Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation=0.03. These results indicate that when external pressure and internal motivation are high, dramatic relief is also likely to be high. When dramatic relief is high, attitudes towards drug treatment are likely to be positive. The findings indicate that interventions to get individuals into drug treatment should include processes that promote Dramatic Relief. Implications for addictions health services are discussed.

Treatment motivation has historically been viewed as a crucial element promoting client responsiveness to treatment and favorable treatment outcomes.1,2 However, empirical research typically finds only modest association between motivation and treatment success.2 This may be because drug treatment motivation has routinely been measured solely as an internal characteristic.3,4 Simpson and Joe identified three dimensions of drug treatment motivation: drug problem recognition, desire for help, and treatment readiness.4 However, this model of motivation overlooks various external pressures, such as coercion from family members, loved ones, and the criminal justice system, that can lead someone to enter drug treatment despite resistance or doubt about its benefits. In other words, drug users enter treatment for a variety of internal and external reasons and treatment success more likely depends on the interplay of these reasons.5 For example, external pressure could translate to high motivation for drug treatment when that pressure is properly internalized.

Previous research has led to the development of multiple models of behavior change.6 Among them, the Transtheoretical Model of Change appears to be the best candidate for further study as it represents the combination of many tenants of the behavior change models that came before it (i.e., the Health Belief Model, the Theory of Reasoned Action, and Social Learning Theory).7 The Transtheoretical Model is a framework that describes behavior change through three major constructs: Stages, Levels, and Processes of Change.8–10

DiClemente and Scott state that the first major construct of the Transtheoretical Model, the Stages of Change, “represent the temporal, motivational, and developmental aspects of the process of change” (p. 139).10 As applied to drug abuse and dependence, the Stages of Change are (1) Precontemplation: the individual does not recognize problems arising from drug use and is not considering change, (2) Contemplation: the individual recognizes problems arising from drug use and is considering change but remains ambivalent, (3) Preparation: the individual plans to change behavior soon, (4) Action: the individual makes an overt behavior change (e.g., stops using drugs or enters drug treatment), and (5) Maintenance: the individual works to prevent relapse and to consolidate steps taken at the Action stage.

The second major construct, the Levels of Change, offers a framework for identifying significant problem areas for individuals attempting to initiate behavior change.8 The levels of change that are theorized to be involved in both the initiation and cessation of alcohol and drug use behaviors are Symptomatic/Situational, Maladaptive, Interpersonal Conflicts, Family Systems Conflicts, and Intrapersonal. They represent areas of functioning in which an individual may be experiencing significant problems. The levels help to identify the number and severity of problems. The problems can occur at any level or at multiple levels. The purpose of the levels, in terms of the change process, is to identify problems that may interfere with an individual’s ability to move through the stages of change to the Maintenance Stage.

The third major construct, the Processes of Change, facilitates movement through the Stages of Change.11 There are four types: cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and environmental. The Consciousness Raising (cognitive process of acquiring information about the problem) and Dramatic Relief (emotional response to problem recognition) Processes of Change are prominent as people move from the Precontemplation to Contemplation stages. Movement to the Preparation and Action stages tends to be a function of behavioral and environmental processes.

In the Transtheoretical Model, drug users highly ambivalent about stopping their use are at the Precontemplation stage of change. Dramatic relief involves emotional arousal about one’s current behavior and the psychological relief that can come from changing from Precontemplation to Contemplation.12 Dramatic Relief is a trigger that prompts people to acknowledge, at an emotional level, their problem behavior and its impact on those around them. Fear, inspiration, guilt, and hope are some of the emotions that can promote dramatic relief and move people from Precontemplation to Contemplation. Motivational interviewing, psychodrama, role playing, grieving, and personal testimonies are examples of techniques used to create such movement.13

While earlier behavior change research concluded that interventions using education and fear arousal techniques did not motivate behavior change, many of these intervention studies were evaluated by their ability to move people to immediate action (e.g., Abrams et al.14). Processes like Dramatic Relief are intended to move people to the Contemplation stage, not necessarily the Action stage.15 Therefore, the effectiveness of these processes should be determined by whether they produce progress across these two initial stages as expected.16–18

The purpose of this study was to determine the role of a specific Process of Change taken from the Transtheoretical of Change in predicting attitudes towards drug treatment, which served as a proxy for readiness for change. It was hypothesized that there would be significant positive predictive relationships from External Pressure and Internal Motivation to Dramatic Relief and a significant negative predictive relationship between Dramatic Relief and Negative Drug Treatment Attitudes. These hypotheses were tested using structural equation modeling.

Methods

Participants

Participants (n=465) were men (58.9%) and women (41.1%) between the ages of 18 and 68 (M=40.0, SD=10.7) who were consecutively admitted into drug treatment at several of the Matrix Clinics throughout the Greater Los Angeles area. Data were collected between September 2002 and January 2005. As participants entered treatment, they were asked by study staff if they would like to participate in this study. If they agreed, they completed the study intake measures. All participants gave informed consent and were compensated for their participation. The study had the approval of the UCLA Institutional Review Board (IRB) as well as the approval of the Matrix Clinics IRB.

The final sample was racially and ethnically diverse (35.1% White, 21.3% Black, 34.2% Hispanic/Latino, and 9.5% other). The participants reported a variety of different drugs as their primary drug of choice: 52.7% reported Heroin, 23.4% reported Methamphetamine, 16.1% reported Cocaine/Crack, and 7.7% reported some other drug.

Measures

The measured items that loaded onto the latent variables used in this study are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Factor loadings, means, and standard deviations of the variables of interest

| Factor Measured item | Factor loading | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| External Motivation | |||

| EP1 | I was referred for treatment by the legal system | 0.82 | 2.05 (1.32) |

| EP2 | I will get in trouble if I don’t remain in treatment | 0.83 | 2.47 (1.35) |

| EP3 | I don’t feel I have a choice about remaining in treatment | 0.64 | 2.19 (1.25) |

| EP4 | I came to treatment because I was pressured to come | 0.63 | 1.93 (1.13) |

| Internal Motivation | |||

| IM1 | I came for treatment because I want to make changes | 0.63 | 3.84 (0.50) |

| IM2 | I came for treatment because it’s important to me personally | 0.71 | 3.84 (0.45) |

| IM3 | I came to treatment because I was interested in getting help | 0.83 | 3.82 (0.49) |

| IM4 | I chose treatment because it’s an opportunity to change | 0.75 | 3.88 (0.41) |

| Dramatic Relief | |||

| I want to stop using drugs because: | |||

| DR1 | I owe it to the people who are trying to help me | 0.50 | 3.91 (1.12) |

| DR2 | I will hurt the people that I care about if I continue to use | 0.73 | 4.35 (0.78) |

| DR3 | I often don’t like myself because of my drug use | 0.63 | 4.18 (0.91) |

| DR4 | I feel bad that my drug use has hurt other people | 0.83 | 4.39 (0.91) |

| Negative Drug Treatment Attitudes | |||

| TA1 | Most counselors in drug treatment programs are “squares” who don’t understand drug users | 0.57 | 3.79 (0.97) |

| TA2 | Drug treatment programs have too many rules and regulations to suit me | 0.71 | 3.50 (1.07) |

| TA3 | I don’t think I could trust many of the people who work in the drug treatment programs | 0.73 | 3.52 (1.00) |

| TA4 | It takes too much time and effort to get into a drug treatment program | 0.55 | 3.60 (0.93) |

All factor loadings significant, p<0.001

External pressure and internal motivation

Eight items from the Treatment Motivation Questionnaire19 were used as indicators of two latent variables, External Pressure and Internal Motivation (see Table 1). Four items loaded onto each latent variable. The scale began with the prompt: “Please tell me how true each reason for entering or staying in treatment is for you right now”. This was followed by each measured item and a corresponding four-point Likert-type scale (4=Very True, 3=Sort of True, 2=Not Very True, and 1=Not True at All). The items that loaded onto the External Pressure factor had a Cronbach’s α= 0.82. The items that loaded onto the Internal Motivation latent variable had a Cronbach’s α=0.82. Both of these values indicate good internal consistency, or reliability, among the items loading onto their respective latent variables.

Dramatic relief

Four measured items from the Dramatic Relief Scale20 loaded onto the Dramatic Relief latent variable (see Table 1). The scale began with the prompt: “For these questions, please tell me how much you agree or disagree with the statement”. This was followed by a sentence stem: “I want to stop using drugs because:” and then each measured item and a corresponding five-point Likert-type scale (5=Strongly Agree, 4=Agree, 3=Undecided or Not Sure, 2=Disagree, and 1=Strongly Disagree). The items that loaded onto the Dramatic Relief latent variable had a Cronbach’s α= 0.74, indicating good internal consistency.

Negative drug treatment attitudes

Four measured items from the Negative Attitudes towards Formal Treatment Programs factor of the Treatment Attitude Profile21 loaded onto the Negative Drug Treatment Attitudes latent variable (see Table 1). This factor includes five items that deal with an individual’s lack of trust or confidence in treatment program staff, dislike of program rules, and other negative perceptions and barriers to the use of formal treatment. The scale begins with the prompt: “Please tell me how much you agree or disagree with each of the following statements”. This was followed by each measured item and a corresponding five-point Likert-type scale (5=Strongly Agree, 4=Agree, 3=Undecided or Not Sure, 2=Disagree, and 1=Strongly Disagree). The items that loaded onto the Negative Drug Treatment Attitudes latent variable had a Cronbach’s α=0.73, indicating good internal consistency.

Analyses

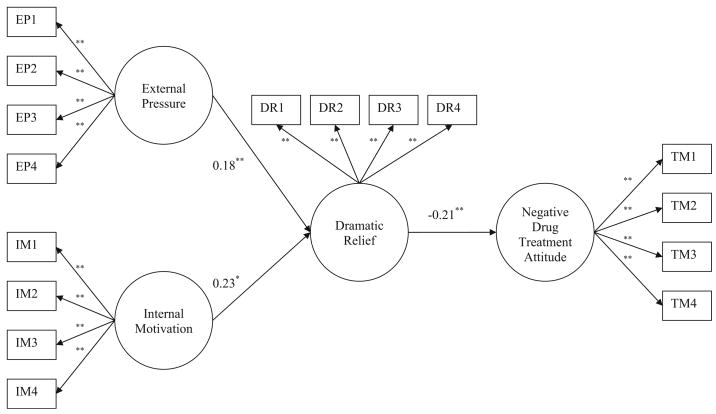

The EQS statistical software package22 (EQS) was used to estimate a model in which External and Internal Motivation latent variables predicted the Dramatic Relief latent variable, which, in turn, predicted the Treatment Attitude Profile latent variable (see Fig. 1). The advantages of using latent variable structural equation models are that they offer goodness-of-fit statistics that compare the hypothesized factor structure to the factor structure within the data. Latent variable structural equation modeling also allows for the examination of error-free constructs. Data were initially analyzed using the maximum likelihood (ML) estimation procedure; however, preliminary analyses indicated that the data violated assumptions of multivariate normality under the ML solution, so the models were evaluated using the Maximum Likelihood Robust (MLR) solution and the Satorra–Bentler (S–B) scaled χ2 statistic.23 The MLR solution, offered in the EQS software, is an alternative method of estimating the standard errors of parameters when assumptions of multivariate normality are not satisfied.24,25 This method is recommended when such violations are present in the data.26

Figure 1.

Significant regression paths predicting treatment attitude. Squares represent measured items. Circles represent the latent variables. Arrows from circles to squares represent factor loadings. Arrows between circles represent regression paths. Regression coefficients are standardized. The model had excellent fit: S–B χ2 (df=97, n=463)=142.20, p<0.01; RCFI=0.97, RMSEA=0.03. *p<0.01, **p<0.001

Non-significant values of the scaled χ2 statistic are preferred; however, as any χ2 distribution is sensitive to sample size, additional indicators of goodness-of-fit were used: the Robust Comparative Fit Index (RCFI) and the Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA).27 The RCFI has values that range from 0 to 1. Values of 0.95 and higher are considered preferable and indicate that 95% or more of the covariation in the data is reproduced by the hypothesized model. The RMSEA is an index that measures the amount of residual between the observed and predicted covariance structure. More specifically, the RMSEA, which also has values ranging from 0 to 1, is a measure of fit per degrees of freedom, controlling for sample size. RMSEA values of less than 0.06 indicate a relatively good fit between the hypothesized model and the observed data.

Results

Initial data screening indicated that the data were non-normally distributed; they were multivariately kurtose (Mardia’s coefficient=152.25, normalized estimate z=69.59). As a result, the robust corrections were used for interpretations of all results. Additionally, two of the participants had missing data and therefore were dropped from the analyses, leaving a final sample size of 463.

Confirmatory factor analysis

Table 1 presents the factor loadings, means, and standard deviations of the variables used in the model. Table 2 presents the correlations among the latent variables. The measurement model had excellent fit: S–B χ2 (df=98, n=463)=142.9, p<0.01; RCFI=0.97, RMSEA=0.03. All measured variables loaded significantly onto their hypothesized factors (p<0.01). No model modifications were needed as the specified model fit the data quite well.

Table 2.

Correlations among the latent variables

| IM | EP | DR | NDTA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Motivation (IM) | – | |||

| External Pressure (EP) | −0.25** | – | ||

| Dramatic Relief (DR) | 0.12* | 0.21** | – | |

| Negative Drug Treatment Attitude (NDTA) | 0.09 | −0.15* | −0.18* | – |

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Path analysis

The final model depicting significant predictive paths among latent variables is presented in Figure 1. All paths were significant and in the expected direction. The final model had excellent fit: S–B χ2 (df=97, n=463)=142.20, p<0.01; RCFI=0.97, RMSEA=0.03. No model modification was needed in order to achieve fit. Both Internal Motivation and External Pressure significantly positively predicted Dramatic Relief, which, in turn, significantly negatively predicted Negative Drug Treatment Attitudes.

Discussion

In this study, when both Internal Motivation and External Pressure were high, Dramatic Relief was also likely to be high. Additionally, Dramatic Relief inversely predicted negative attitudes towards formal drug treatment. As noted, Dramatic Relief is an emotional Process of Change that prompts individuals to acknowledge their behavior and its impact on themselves and those around them.11 It is hypothesized that Dramatic Relief is one of the process that moves individuals with drug abuse and dependence problems from the Precontemplation stage to the Contemplation stage in the Stages of Change model.7

Within the drug treatment field, there is a long-held belief that, in order for drug treatment to be successful, those receiving help must want that help. The findings from this study indicate that, in addition to internal motivation, external pressure can be effective at motivating change. The key appears to be that the pressure must be internalized. Dramatic Relief is often experienced when those seeking treatment for the drug dependence recognize the connection between their drug use, the problems their drug use causes, and the concerns of those around them. What is necessary then is to identify and implement processes that promote Dramatic Relief. Previous research indicates that motivational interviewing, psychodrama, grieving losses, and role playing are all mechanisms that promote Dramatic Relief.8 A group process promoting Dramatic Relief among drug users in treatment has also been developed and empirically supported.28 The process starts with group participants identifying individuals in their life that have expressed concern for them. Following this identification, the group leader facilitates a discussion among the group members about this concern, what may motivate it, why it may matter, and how they might respond.

When attempting to understand what motivates individuals to seek treatment for their drug use problems, previous research has largely focused on internal factors; however, there are often external pressures, such as pressure from family and loved ones or from the criminal justice system, on an individual to get help and to change their behavior. In particular, the criminal justice system is responsible for an increasing number of referrals of drug-using offenders to treatment. An example can be found in the state of California. In 2001, California enacted the Substance Abuse and Crime Prevention Act,29 allowing individuals who commit non-violent drug offenses or who violate drug-related conditions of their probation or parole to receive drug treatment with probation or parole rather than just incarceration. It may be prudent for those offering treatment to these court mandated participants to make Dramatic Relief processes an integral part of the treatment regime.

Limitations and future directions

In addition to the limitations noted above, these data are non-experimental and cross-sectional; therefore, directionality and causality cannot be established definitively. However, that the a priori specified model fit the data excellently with no model improvements is promising. Additionally, the sample is non-normative as it is based on individuals being admitted to drug treatment, but the strong findings indicate that fioor or ceiling effects, or range restrictions, did not play a role, as can be the case when using samples with variances that might be restricted by common factors. Additionally, this is a sample of convenience that was taken from the population of individuals seeking drug treatment in a large urban environment in Southern California; thus, the sample may not generalize well to populations that are exceedingly different such as in rural areas or in areas that are not as diverse as Southern California. It should also be noted that all of the participants in this study were already accessing treatment, which could indicate that many were already in the Action Stage of Change. A sample of drug users not in treatment was not available. Finally, while it is possible that the findings could be attributed to a number of non-measured or omitted variables, this is a limitation in any non-experimental study.

Future research should test these hypotheses in a longitudinal framework assessing the role of the Processes of Change as individuals move through the Stages of Change. Additionally, a comparison of individuals voluntarily seeking treatment versus those being referred to treatment through the criminal justice system using this longitudinal framework could shed light on specific differences in readiness for change between those seeking treatment versus those seeking diversion from incarceration. Finally, the addition of a comparison sample of individuals who are not seeking or who have left treatment could also bolster the findings of this study.

Implications for Addictions Health Services

The findings presented herein provide some insights into what motivates people to seek treatment to change their drug use behaviors. While not conclusive, the results reported here represent a first step in understanding the role that Dramatic Relief plays in the relationships among motivation, external pressure, and attitudes towards treatment. These findings take on added importance as society moves towards offering drug treatment as an alternative to incarceration for individuals convicted of drug use offenses. Treatment providers treating individuals who enroll in treatment primarily as a result of external pressure may want to utilize treatment techniques to promote Dramatic Relief such as motivational interviewing, role playing, or the group model. Treatment outcomes will likely benefit from engaging in process that translate this external pressure into the internal motivation needed to affect real change in drug use behaviors.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by Grants R03-DA23131, R01-DA12476, and K05-DA00146. Dr. Anglin is also supported by NIDA Senior Research Scientist Award K05 DA00146.

Contributor Information

Bradley T. Conner, Integrated Substance Abuse Programs, Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, University of California, Los Angeles, 1640 South Sepulveda Boulevard, Suite 200, Los Angeles, CA 90025-7535, USA. Phone: +1-310-2675379. Fax: +1-310-4737885. Email: bconner@ucla.edu.

Douglas Longshore, Integrated Substance Abuse Programs, Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA. Drug Policy Research Center, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, USA.

M. Douglas Anglin, Integrated Substance Abuse Programs, Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

References

- 1.De Leon G, Melnick G, Hawke J. The motivation-readiness factor in drug treatment: implications for research and policy. Advances in Medical Sociology. 2000;7:103–129. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Longshore D, Teruya C. Treatment motivation in drug users: a theory-based analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;81:179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joe GW, Broome KM, Rowan-Szal GA, et al. Measuring patient attributes and engagement in treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22:183–196. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simpson DD, Joe GW. Motivation as a predictor of early dropout from drug abuse treatment. Psychotherapy. 1993;30:357–368. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryan RM, Plant RW, O’Malley S. Initial motivations for alcohol treatment: relations with patient characteristics, treatment involvement, and dropout. Addictive Behaviors. 1995;20:279–297. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)00072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glanz K, Lewis F, Rimer B. Linking theory, research, and practice. In: Glanz K, Lewis F, Rimer B, editors. Health behavior and health education: theory, research and practice. 2. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitelaw S, Baldwin S, Bunton R, et al. The status of evidence and outcomes in Stages of Change research. Health Education Research. 2000;15:707–718. doi: 10.1093/her/15.6.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change: applications to addictive behavior. American Psychologist. 1992;47:1102–1114. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prochaska JO, Norcross JC, DiClemente CC. Changing for good. New York: Morrow; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiClemente CC, Scott CW. Stages of change: interaction with treatment compliance and involvement. In: Onken L, Blaine J, Boren J, editors. Beyond the therapeutic alliance: keeping the drug-dependent individual in treatment. NIDA research monograph series (no. 165) Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1997. pp. 131–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiClemente CC, Schlundt D, Gemmell L. Readiness and stages of change in addiction treatment. American Journal on Addictions. 2004;13:103–119. doi: 10.1080/10550490490435777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norman GJ, Velicer WF, Fava JL, et al. Dynamic typology clustering within the stages of change for smoking cessation. Addictive Behaviors. 1998;23:139–153. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(97)00039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Czuchry M, Dansereau DF. Cognitive skills training: impact on drug abuse counseling and readiness for treatment. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2003;29:1–18. doi: 10.1081/ada-120018837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abrams DB, Herzog TA, Emmons KM, et al. Stages of change versus addiction: a replication and extension. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2000;2:223–229. doi: 10.1080/14622200050147484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perz CA, DiClemente CC, Carbonari JP. Doing the right thing at the right time? The interaction of stages and processes of change in successful smoking cessation. Health Psychology. 1996;15:462–468. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.6.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prochaska JO. Moving beyond the transtheoretical model. Addiction. 2006;101:768–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prochaska JO, Levesque DA. Enhancing motivation of offenders at each stage of change phase of therapy. In: McMurran M, editor. Motivating offenders to change. New York: Wiley; 2002. pp. 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schumann A, Meyer C, Rumpf H-J, et al. Stage of change transitions and processes of change, decisional balance, and self-efficacy in smokers: a transtheoretical model validation using longitudinal data. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:3–9. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryan RM, Plant RW, O’Malley S. Initial motivations for alcohol treatment: relations with patient characteristics, treatment involvement, and dropout. Addictive Behaviors. 1995;20:279–297. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)00072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belding MA, Iguchi MY, Lamb RJ, et al. Stages and processes of change among polydrug users in methadone maintenance treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1995;39:45–53. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01135-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neff JA, Zule WA. Predicting treatment-seeking behavior: psychometric properties of a brief self-report scale. Substance Use and Misuse. 2000;35:585–599. doi: 10.3109/10826080009147473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bentler PM. EQS 6 structural equations program manual. Encino: Multivariate Software; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Satorra A, Bentler PM. A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika. 2001;66:507–514. doi: 10.1007/s11336-009-9135-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bentler PM, Dudgeon P. Covariance structure analysis: statistical practice, theory, and directions. Annual Review of Psychology. 1996;47:563–592. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.47.1.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuan K-H, Chan W, Bentler PM. Robust transformation with applications to structural equation modeling. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 2000;53:31–50. doi: 10.1348/000711000159169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Curran PJ, West SG, Finch JF. The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:16–29. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu L-T, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structural analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Velasquez MM, Maurer GG, Crouch C, et al. Group treatment for substance abuse: a stages of change therapy manual. New York: Guildford; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans E, Longshore D. Evaluation of the substance abuse and crime prevention act: treatment clients and program types during the first year of implementation. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2004 May;(Suppl 2):165–174. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2004.10400052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]