Abstract

Recent theoretical work has provided a basic understanding of signal propagation in networks of spiking neurons, but mechanisms for gating and controlling these signals have not been investigated previously. Here we introduce an idea for the gating of multiple signals in cortical networks that combines principles of signal propagation with aspects of balanced networks. Specifically, we study networks in which incoming excitatory signals are normally cancelled by locally evoked inhibition, leaving the targeted layer unresponsive. Transmission can be gated on by modulating excitatory and inhibitory gains to upset this detailed balance. We illustrate gating through detailed balance in large networks of integrate-and-fire neurons. We show successful gating of multiple signals and study failure modes that produce effects reminiscent of clinically observed pathologies. Provided that the individual signals are detectable, detailed balance has an enormous capacity for gating multiple signals.

Experimental observations1,2 as well as theoretical arguments3,4 suggest that excitation and inhibition are globally balanced in cortical circuits. In a globally balanced network, each neuron receives large but approximately equal amounts of excitation and inhibition that, on average, cancel each other. Spontaneous activity is driven by fluctuations in the total synaptic input, leading to asynchronous and irregular patterns of spiking5–8. Such networks have been used to study signal propagation and to determine conditions that support various signaling schemes9–16. However, neurons in these networks are typically only part of a single signaling pathway, and the transmitted signals cannot be gated or rerouted. Cognitive processing requires signal paths to change dynamically according to the information content of the signal and the processing demands of the receiver17. This requires precise control and gating of signal-carrying pathways.

We propose a mechanism for gating based on an extension of the concept of globally balanced networks to local cortical circuits in a form that we call “detailed balance”. Detailed balance implies that, in addition to an overall or global balance, neurons receive equal amounts of excitation and inhibition on subsets of their synaptic inputs that correspond to specific signaling pathways. Activation of a balanced pathway produces little response in the excitatory neurons of the signal-receiving region, but responses can be gated on by a command signal that disrupts the detailed balance. We analyze properties of the resulting gating mechanism and examine some of its failure modes. We show that the mechanism can gate the propagation of signals from multiple different sources to a single group of neurons, and we determine its capacity for gating large numbers of signals.

Results

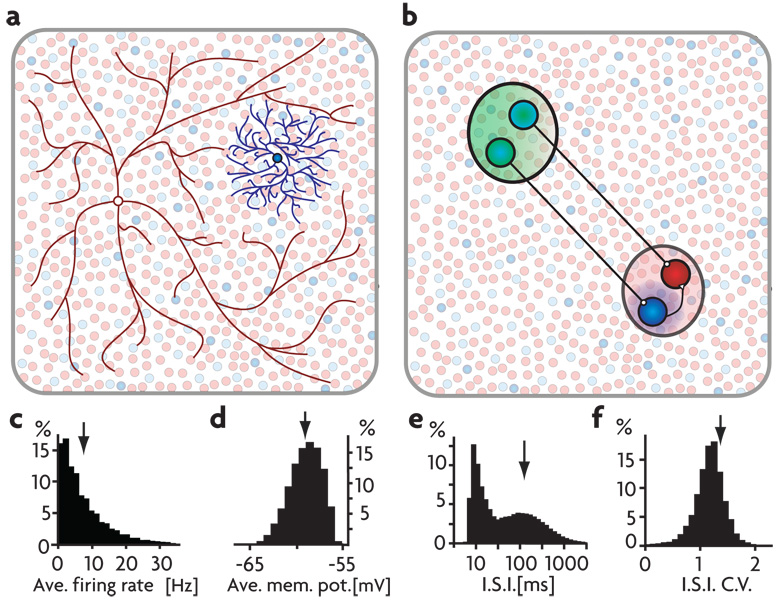

We explored the idea of detailed balance in a large network of roughly 20,000 integrate-and-fire neurons with both short- and long-range connectivity (Fig. 1a, methods). With appropriately adjusted parameters, this network operates in a globally balanced manner, producing irregular, asynchronous activity in the absence of any time-varying or random external input 5–8. The distribution of firing rates for the network is approximately exponential with an average firing rate per neuron of 8 Hz (Fig. 1c), the distribution of average membrane potentials is approximately Gaussian with a mean of −60 mV (Fig. 1d), the distribution of interspike intervals (ISIs) is broad with peaks reflecting normal firing and bursting (Fig. 1e), and the distribution of coefficients of variation for the ISIs is centered at a value slightly greater than 1 (Fig. 1f). Average excitatory and inhibitory membrane currents are of approximately equal magnitude and the net current is near zero (Fig. 2c, first column), indicating the globally balanced state of the network. This network model is intended to provide a sparse representation of the neurons over a fairly large area, not a full description of a single local circuit such as a cortical column.

Figure 1. Network Connectivity and Properties.

a) All excitatory and 65% of the inhibitory neurons are connected randomly with a connection probability of 2% (illustrated in red). The other 35% of the inhibitory neurons have local connectivity, targeting their nearest neighbors (illustrated in blue). b) An embedded signal pathway is created by selecting a group of sender neurons (in green) that target either excitatory or locally inhibitory neurons (in red and blue, respectively, throughout the figures) in a signal-receiving region (in red) of the network. C–f) Asynchronous background activity in the network model. Distributions for network neurons of: c) firing rates, d) average membrane potentials, e) ISIs plotted on a semi-log scale, and f) coefficients of variation for those ISIs. Arrows indicate the means of the distributions.

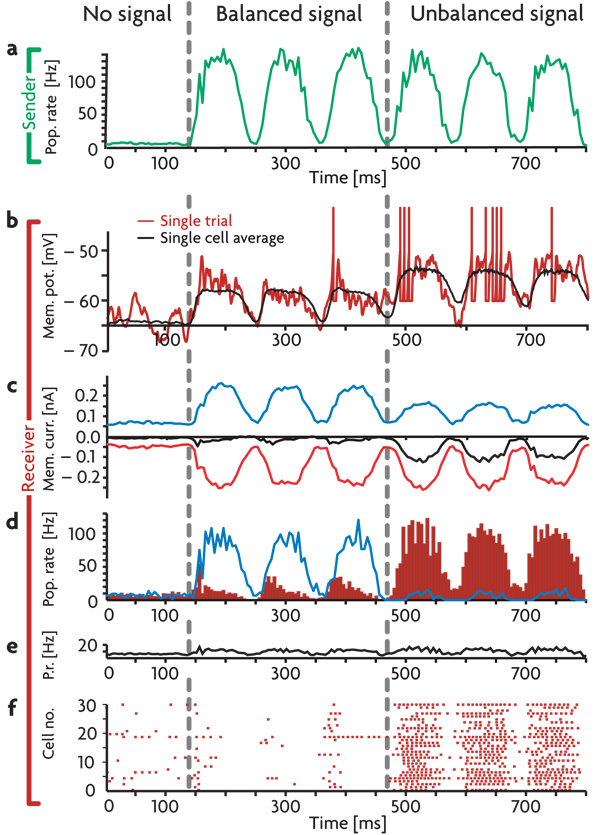

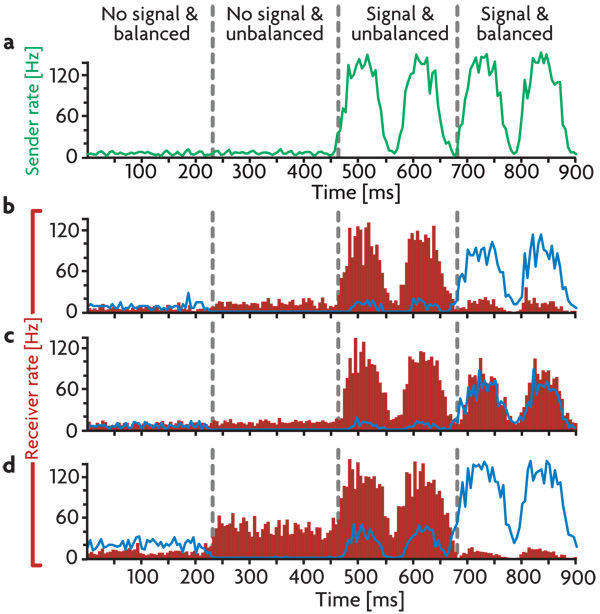

Figure 2. Detailed Balance in a Network.

a) Average firing rate of the sender neurons responding to a sinusoidally varying input. b) Voltage trace of a randomly selected excitatory receiver neuron. Red trace: single trial. Black trace: the average subthreshold membrane potential over 100 trials. c) Average membrane currents of the excitatory receiver neurons. Excitatory and inhibitory currents are plotted in red and blue respectively, the net current, including voltage-dependent leak and constant background currents, is plotted in black. d) Blue trace: average firing rate of the inhibitory receiver neurons. Red histogram: average firing rate of the excitatory receiver neurons. e) Average firing rate of the entire network. f) Spike raster for 30 randomly chosen excitatory receiver neurons. Conditions shown are: No signal: All neurons fire at background rates. Balanced signal: Sender neurons fire in a correlated manner in response to oscillatory input and project the input firing pattern to both excitatory and inhibitory receiver neurons. Inhibitory receiver neurons reproduce the input pattern, preventing their excitatory neighbors from doing the same. Unbalanced signal: By decreasing the responsiveness of the inhibitory receiver neurons, the signal balance in the excitatory receiver neurons shifts in favor of excitation, and the signal is revealed in their firing pattern. All firing rates and averages are calculated in 5 ms bins.

Signal Gating

To investigate signal gating within the network, we embed a two-layered pathway with “sender” and “receiver” subnetworks (green and red areas in Fig. 1b, respectively). These should be viewed as parts of distinct cortical regions. The connections from the sender region are directed to both excitatory and inhibitory neurons in the receiver region. Such targeting to inhibitory interneurons is consistent with data on the specific targeting of long-range excitatory projections to inhibitory interneurons18. To generate a signal, we drove the neurons in the sender subnetwork with a set of external Poisson spike trains at various rates. This causes neurons in the sender area to fire in a manner that mimics the input signal (Fig. 2a). In the balanced state, excitation from the sender network, a simple oscillatory signal in the example of Fig. 2, activates both excitatory and inhibitory sub-populations in the receiver region. The resulting inhibitory activity (blue trace in Fig. 2d) produces a local countersignal that cancels the excitatory membrane currents (Fig. 2c) and generates only modest firing-rate fluctuations in the excitatory receiver neurons (red histogram in Fig. 2d, Fig. 2f). The signal path is hence gated off in the default (balanced) state of the signal-carrying pathway.

Signal propagation within this network can be gated on in a number of ways, all of which involve unbalancing the excitatory and inhibitory pathways between the sender and receiver regions. The main requirement is a mechanism that differentially modulates the net excitatory and net inhibitory pathways from the sender to the receiver region19. A possible candidate is cholinergic modulation, which satisfies the basic requirements of cell-specific targeting20,21 as well as relatively rapid response times22–24. Rather than modeling such modulation in detail, in the following examples detailed balance is disrupted by decreasing the gain or responsiveness of local inhibitory interneurons in the receiver region. This modulation, in keeping with the strong effects of attention seen for inhibitory neurons25, corresponds to changing the input-output transfer function so that the same synaptic current generates a smaller response. Although the examples we show focus on modulation of inhibition, any combination of modulations that increases the ratio of excitatory to inhibitory transmission along the signaling pathway will perform similarly. To unbalance the signal in Fig. 2, the response gain of the local inhibitory neurons in the receiver region was reduced to 15% of its control value (we discuss more modest gain modulations below).

Gain modulation that decreases the amplitude of the firing-rate modulations of inhibitory neurons in the receiver region (blue trace in Fig. 2d) reduces the inhibition of excitatory neurons in this region, leaving the bulk of the excitatory synaptic current uncanceled (Fig. 2c). This produces robust firing in the excitatory receiver neurons that is locked to the temporal pattern of the input signal (Fig. 2b,d,f). Overall network activity is relatively unaffected by these changes (Fig. 2e) because the modulated interneurons provide only a small fraction of the total inhibition to the network. Average subthreshold membrane potentials (excluding action potentials and their subsequent refractory periods) of the excitatory receiver neurons in the balanced and unbalanced states (Fig. 2b, black trace) differ by only 4 mV, but this is sufficient to produce dramatically different firing patterns.

Response Properties

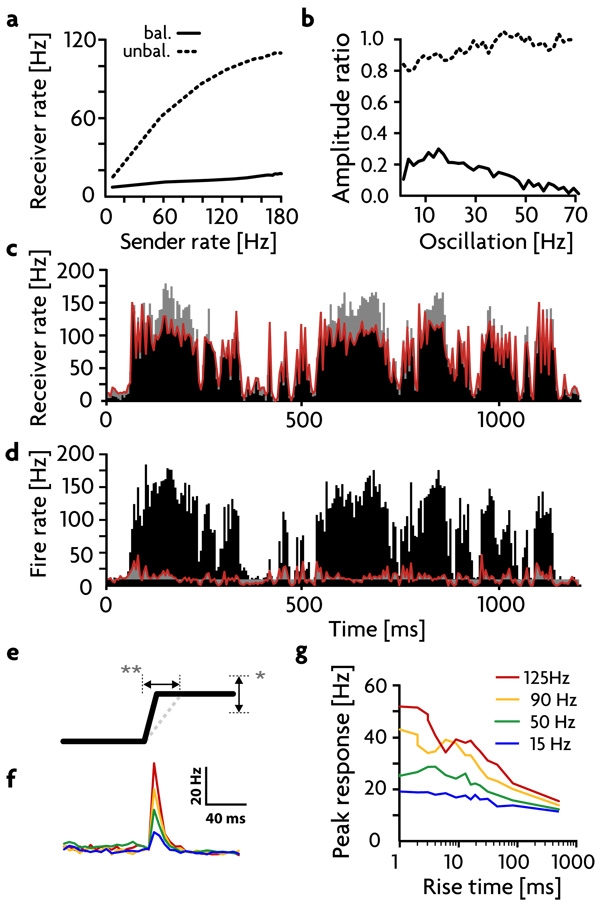

To further quantify the gating mechanism, we studied responses to different types of input (Fig. 3a & b). The firing rates of excitatory receiver neurons are relatively unaffected by constant input rates in the balanced gated-off state (solid trace in Fig. 3a) but rise sharply as a function of input rate when the pathway is gated on (dashed trace in Fig. 3a). The rise begins to saturate at high rates due to the residual inhibition produced locally, even at low gain. Gating is also evident in the amplitudes of firing-rate fluctuations for excitatory neurons in the receiver region when the input signal is oscillatory (Fig. 3b). In addition, gating occurs when filtered white noise (with a 50 ms time constant12) is used as the input signal (Fig. 3c, d). In the gated-on state, this complex, irregular signal is transmitted with similarity values12,14 (defined in the methods) of ~90%, sufficient to propagate the signal across several layers14. In the balanced, gated-off state (Fig. 3d), the output of the excitatory receiver group is greatly decreased in amplitude, and the similarity between input and output is reduced to ~25%.

Figure 3. Response Analysis.

a) Firing rates of the excitatory receiver neurons as a function of different constant sender firing rates, in the balanced (solid trace) and unbalanced (dashed trace) states. b) Ratio of receiver to sender excitatory firing-rate oscillation amplitudes at different oscillation frequencies, in the balanced (solid trace) and unbalanced (dashed trace) states. c,d) Response to a random time filtered signal in the unbalanced (c) and balanced (d) states. Red trace: average firing rate of the excitatory receiver neurons. Black histogram: rates of the sender neurons. Deviations from the signal in c) and from the average background rate in d) are colored grey. e) Schematic of an input step. Step size (*) and step duration (**) are varied independently. f) Average responses of the excitatory receiver neurons in the balanced state to instantaneous steps of different sizes. g) Peak amplitude of the responses in these neurons to steps of different sizes (legend) and durations (horizontal axis).

A close inspection of the responses in the balanced state (Fig. 3d) shows that detailed balance does not completely cancel signals when input firing rates change rapidly. Rapid changes in the signal can evoke a response in the excitatory receiver neurons before inhibition can balance excitation because of the time lag between the monosynaptic excitation and the canceling disynaptic inhibition acting on the receiver neurons. This effect would be even more dramatic if excitatory and inhibitory synapses were subject to different amounts or types of short-term plasticity. Such partial gating of transients allows large signals with rapid onsets to be propagated, which may induce upstream control circuits to activate gain modulation and open the gate. To further investigate this effect, we activated the sender neurons with step-like input rates of various step sizes and rise times (Fig. 3e). Short rise times produce fairly strong responses in excitatory receiver neurons that depend on the step size (Fig. 3f & g), even in the balanced gated-off state, but these diminish as the rise time of the step increases, illustrating the transient nature of this transmission.

The gain changes used to gate signals on have been fairly large, so we next examined different degrees and types of gain modulation in the inhibitory receiver neurons. Beginning with no gain change (Δ Gain = 0), we decreased the responsiveness and thus the firing rate of the inhibitory receiver population. This causes the firing rate of the excitatory receiver neurons and its similarity to the sender signal in the gated-on state (Fig. 4a, solid red trace) to increase. At Δ Gain ~80%, the signal similarity of the activity of the inhibitory neurons goes rapidly to zero (Fig. 4a, solid blue trace), and the similarity of the excitatory receiver activity plateaus at ~90%. Alternatively, it is possible to reach this same plateau level with a gain shift of only 30% (Fig. 4a, dotted traces) by modulating the inhibitory population asymmetrically, which means modifying only the responsiveness to excitatory inputs.

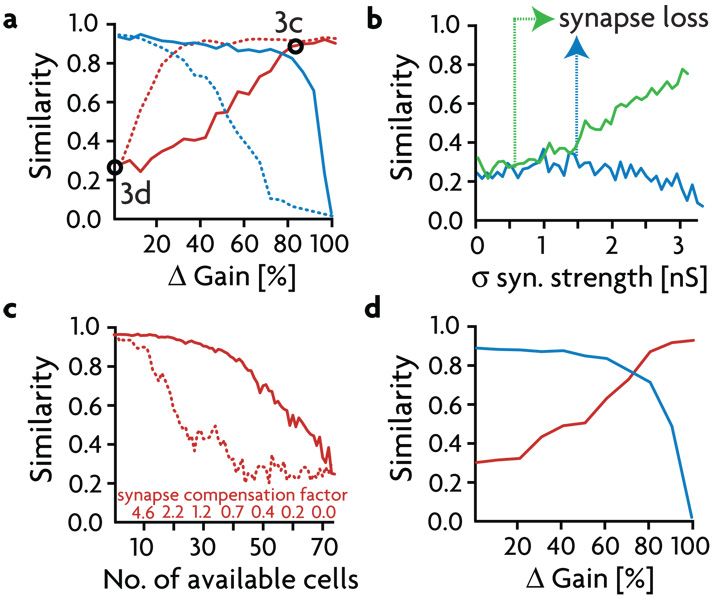

Figure 4. Gain Properties.

a) Maximum values of the cross-correlations (termed "similarity", see methods) between the sender region and the excitatory and inhibitory receiver cells (red and blue respectively) for different gains. Solid lines show similarity values for symmetric gain reduction, dashed lines show similarity for asymmetric gain reduction, when only the gain of the excitatory synapses onto the inhibitory receiver cells is changed. b) Similarity values between excitatory receiver activity and the signal in the balanced (gated-off) state as a function of increasing the variability (standard deviation σ) of the synaptic strengths of the excitatory (green trace) and inhibitory (blue trace) pathways. The arrows mark the variability limits beyond which the tails of the strength distributions get rectified to zero. c) Effect of reducing the number of inhibitory receiver neurons on the ability to gate signals off. Similarity values in the balanced state for decreasing numbers of inhibitory receiver cells, without and with synapse strength compensation (solid and dotted line, respectively). d) Operation of the gating mechanism with only 20 inhibitory receiver neurons by compensating synapse strength and shortened refractory times to allow for more rapid inhibitory firing. Similarity between the signal and the excitatory (red trace) and inhibitory (blue trace) receiver activity is plotted as a function of change in inhibitory gain.

The gating mechanism is robust to a number (but not all, see below) of different perturbations of the network. Fig. 4b shows a plot of the similarity of responses in the receiver region to the signal, when it is gated off, as a function of the variability in the strengths of the inhibitory (blue trace) or excitatory sender synapses (green trace) onto the excitatory receiver cells. Synaptic strength variance does not have a dramatic effect in either case until the variance gets large enough to force significant numbers of synapses to zero strength (which occurs at a different point for excitatory and inhibitory synapses because of their different initial strengths), changing the mean synaptic strength. After this point, the high degree of variability in the excitatory synaptic strengths makes it difficult to shut the signal off (Fig. 4b, green trace).

We also tested the robustness of gating a signal off to the loss of its most critical components, the inhibitory neurons in the receiver region (Fig. 4c). The effect of decreasing the number of available interneurons (originally 73) is roughly linear (solid trace), until gating off fails completely when less than 40 cells are available. It is possible to partially rescue gating by up-regulating the strengths of all remaining inhibitory synapses proportional to the number of deleted neurons and thus deleted synapses (dotted trace). However, gating still fails when less than 25 inhibitory cells are available because such a small population of inhibitory neurons cannot fire a sufficient number of action potentials to provide balancing membrane currents, even if their synapses are strengthened to unrealistically high values. If the inhibitory receiver neurons are allowed to spike at rates as high as 600 Hz, it is possible to further rescue the balance mechanism, and successfully gate signals in as many as 600 excitatory cells with as few as 20 inhibitory neurons (Fig. 4d).

Pathologies

The basic requirement to achieve a state of detailed balance is local inhibition strong enough to cancel signals in the gated-off state. In addition, the gain modulation used to unbalance and gate-on a pathway must not have an excessively destabilizing effect on the global excitatory-inhibitory balance of the network. With this in mind, we examined additional ways in which network gating can fail when tuning is relaxed. Fig. 5 shows gated off and gated on states with no signal and in the presence of an oscillatory signal. With proper tuning (Fig. 5b), the excitatory neurons of the receiver subnetwork respond robustly only when the signal is present and gating is on, although there is a weak transient response when the signal is present but gating is off.

Figure 5. Network Pathologies.

(a) Average firing rate of the sender neurons without and with an oscillatory input. (b–d). Responses of excitatory (red histogram) and inhibitory (blue trace) receiver neurons with: b) Correct tuning. c) Weakened local inhibition, leading to a gating deficit. d) A hyperactive receiver region causing a response to the gating modulation. Conditions shown in the different columns are: No signal and no modulation. No signal but gated on. Signal on and gated on. Signal on but gated off. Firing rates are calculated in 5 ms bins.

We considered two different de-tuning conditions. First, we reduced the strength of all synapses from the local inhibitory neurons by 60% (Fig. 5c). This causes baseline firing rates in the absence of a signal to rise slightly, but the effect is not large because the bulk of the inhibition is not affected. Little change is seen in the response to the gain modulation alone, but activating the input shows that the gating mechanism has been compromised. Due to the weakened inhibition, excitatory inputs to the excitatory receiver neurons cannot be fully cancelled by local inhibition, and the signal can never be fully gated off.

We also de-tuned the detailed balance by increasing the strength of excitatory synapses within the receiver area by 60% (Fig. 5d). Excitatory synapses onto excitatory and inhibitory neurons were both modulated in this way, so a rough balance was still maintained within the receiver region. As in the case of reduced inhibition, enhanced excitation slightly elevates firing rates in the gated-off, no-signal condition. Activating gain modulation to open the gate causes a significant elevation in the firing rate of excitatory receiver neurons, even when no signal is present. Thus, with altered excitation, the receiver neurons respond to the gating signal as if it were an input. This means that the network falsely transmits internally generated activity (the gating signal) as if it were an external signal. On the other hand, in this condition signal responses in both the gated-on and gated-off states appear normal. We address the implications of these findings in the discussion section.

Multiple Signals

One of the advantages of the gating mechanism we propose is that a group of receiver neurons can remain responsive to one set of incoming signals even while other sets are being cancelled by balancing inhibition. This gives the mechanism the capacity to gate multiple signals. As a first example, the network we have been considering is expanded so that it can gate two signals, rather than one. We then discuss the capacity of detailed balance for switching a large number of signals using a model the simulates a single neuron in the networks we have been using.

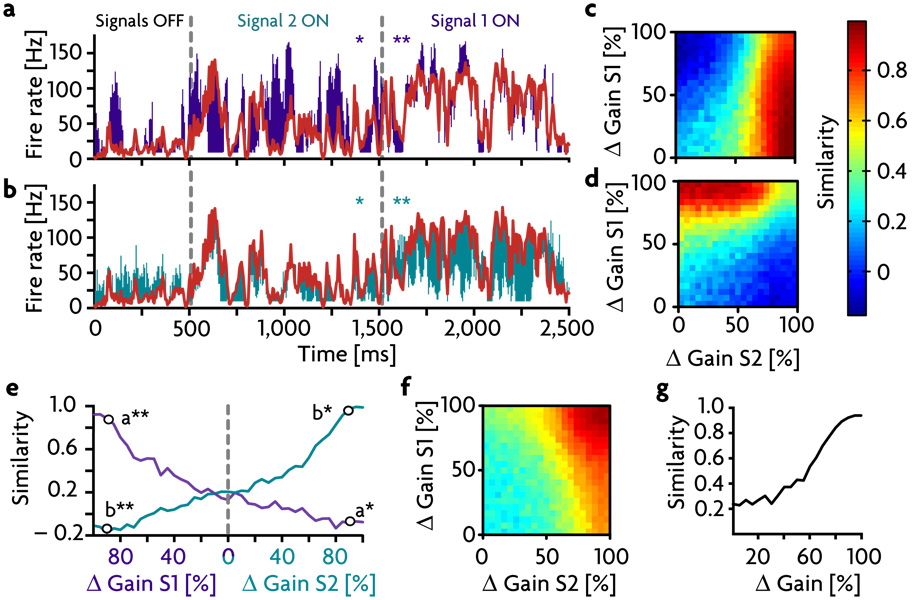

We introduced a second signal to the receiver group (to accommodate two signals, S1 and S2, we modified the network architecture slightly to allow for two separate groups of ~70 inhibitory neurons; methods). Fig. 6a & b show the average firing rate of the excitatory receiver subnetwork compared to signals S1 and S2 respectively. The colored bars indicate the difference between the average firing rate in the receiver region (plotted in red) and each of these signals. When both pathways are balanced (“signals off”), firing in the receiver region stays roughly at the background level, except for transient responses as described above. When one of the pathways is unbalanced to allow propagation of its signal, the response of the receiver group follows that signal accurately, as indicated by the small divergence between the appropriate signal and response pair. Activity of the receiver subnetwork does not follow the signal that is in the off-state, as indicated by the larger colored difference regions for the gated-off signals. This finding can also be confirmed using the similarity measure. Panels c and d show the similarity to S1 and S2, respectively, for all combinations of the two levels of inhibitory gain reduction. The regions where similarity is high for either signal are well separated from each other, and both signals reach similarity values above 85% in the regions where they are gated on. Furthermore, when only one of the two signals is gated on, the other signal tends to weaken, and similarity between receiver activity and the gated-off signal can even become negative due to inhibitory overshoot (Fig. 6e). To compare the gating of two signals with the gating of one, it is useful to examine the similarity value between the combined signal S1+S2 and the firing rate of the receiver cells (Fig. 6f & g). This is much the same as in the single-signal case of Fig. 4a (solid red trace).

Figure 6. Gating Two Signals in a Network.

a,b) Average response of the excitatory receiver subnetwork to two simultaneously delivered signals ( S1 and S2). The colored bars indicate the difference between the average firing rate in the receiver region (plotted in red) and either S1 (purple bars in a) or S2 (green bars in b). First column: Both signal pathways are balanced, the signals are off. Second and third column: Signal pathways 2 and 1 are unbalanced, respectively, by shifting the gain of their respective inhibitory receiver populations to 15% of their control values. c,d) Similarity values between S1 and the excitatory receiver activity (c) and S2 and the same excitatory receiver activity (d) for all possible combinations of the two gain modulations. Both signals reach similarity values of above 85%. e) Similarity values for S1 and S2 for independent gain changes. To the left of the gray line only the gain for S1 is manipulated while the gain for S2 remains 100%, and vice versa on the right side. Black circles indicate the gain values used for panels a & b. f) Similarity values as in c & d) but measured for the combined signal S1+S2. g) Similarity values between S1+S2 and the excitatory receiver subnetwork activity as a function of combined (equal) inhibitory gains, taken from the results along the diagonal of f.

How many signals can be canceled and then gated on by a population of inhibitory neurons? To address this question, we studied a single excitatory receiver neuron, rather than the full network that we have been considering up to this point. As discussed above for the two-signal case, configuring a network for multiple signals takes a fair amount of modification and readjustment, and this made it unpractical to consider a wide range of different numbers of signals within a full network. Instead, we set up the mechanism of detailed balance in a single integrate-and-fire neuron that receives 800 excitatory and 200 inhibitory inputs. The critical component in determining the capacity of detailed balance for switching multiple signals is the population of inhibitory afferents, because they are less numerous than their excitatory counterparts and must cancel the excitatory effects of the signals, while at the same time allowing a particular signal to get through when modulated. We chose 200 inhibitory inputs to match the number that appear to influence a single pyramidal neuron in cortical circuits26.

The single neuron model acts much like any of the excitatory receiver neurons in the full network because we adjusted its input to match what a typical neurons receives when the network is intact. The excitatory and inhibitory neurons that provide input to this model neuron are represented by Poisson spike trains generated from firing rates that encode various numbers of signals directly rather than through additional model neurons. For this reason, we refer to them as inputs or afferents rather than as neurons although, of course, they correspond to neurons in the full network. Detailed balance is achieved by distributing the signals across the excitatory and inhibitory afferents and adjusting synaptic strengths so that all signals are cancelled in the default state. To gate a particular signal on, we set the gains of all the inhibitory afferents that carry that signal to zero, essentially shutting them off. We used this extreme form of modulating because we wished to compute the maximum capacity of the system, not a capacity limited by restricting the amount of modulation.

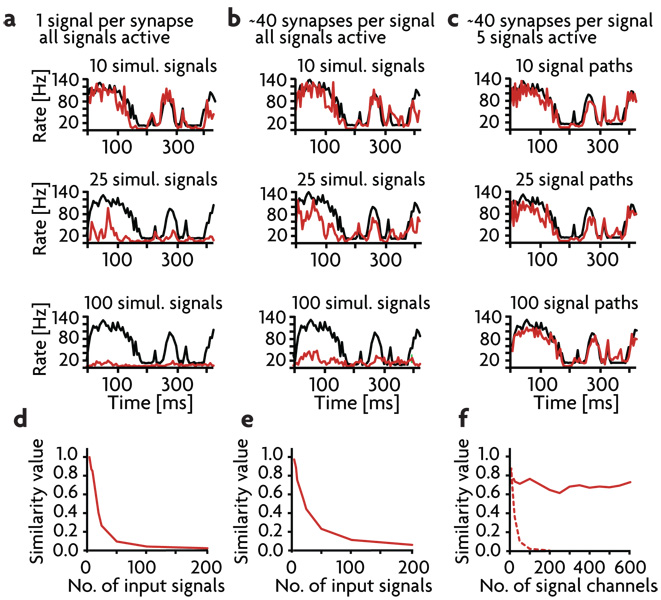

Each signal consists of a mean firing rate plus independent filtered white noise fluctuations (as used in Fig.3 c & d). To begin, we distributed M signals across the afferents so that each excitatory and inhibitory afferent carries only one signal. Obviously, the maximum number of signals that can be distributed in this way is M = 200, the number of inhibitory afferents. Performance, measured in terms of a similarity index (see methods), falls rapidly as a function of the number of signals being gated, and this way of distributing and gating multiple signals does not allow for switching of more than around 10 signals (Figs. 7a, d). The problem is not in canceling out the signals that are not being gated on, but in being able to fully gate on the chosen signal.

Figure 7. Multiple Signals into a Single Cell.

a–c) Firing rates of the output signal (red), averaged over 200 runs, compared to the input signal (black). 1st row: 10 simultaneous signal paths. 2nd row: 25 simultaneous signals paths. 3rd row: 100 simultaneous signal paths. a) Each afferent to the model neuron carries only one signal. b) Each afferent carries 40 signals. c) Each afferent can carry 40 signals but only 5 signals are present at a given time. d–f) Similarity values as a function of the number of signals being gated in a–c). d) With one signal per afferent, gating is limited to less than about 20 signals. e) Overlapping several signals onto each afferent improves performance slightly. f) When only 5 signals are present at a given time, unlimited numbers of signals can be gated when 40 signals are carried on each afferent (solid trace), but performance is still limited if each afferent carries a single signal (dashed trace).

One problem with the scheme of having one signal per inhibitory afferent is that the number of afferents being gain modulated to zero to gate a given signal on is small. For example, only 10 inhibitory afferents carry any particular signal when M = 20. This problem can be addressed by distributing the M signals across the excitatory and inhibitory afferents so that each afferent carries more than one signal (Fig. 7b). Gating works best if each signal is carried on around 40 inhibitory and 160 excitatory afferents (chosen randomly for each signal from all the available afferents of each type), which means that each inhibitory afferent carries on average 40M/200 signals, rather than 1 as before. In this case, because of the overlap in the signals, when a particular signal is gated on by setting the gains of the inhibitory afferents carrying that signal to zero, this upsets the detailed balance for the other non-gated signals. To compensate for this, the gains of the remaining inhibitory afferents are adjusted so that the non-gated signals are cancelled as nearly as possible by the remaining active inhibitory afferents. In other words, through a procedure discussed in the methods, the gains on the remaining active afferents are increased to compensate for those missing due to gating of the chosen signal. Performance with this distribution of signals is better than for the one signal per afferent case, but detailed balance still cannot handle more than 30 signals (Figs. 7b, e).

What is limiting the ability of the detailed balance scheme to switch large numbers of signals? The limitation is, in fact, not a deficit of the detailed balance scheme, but a fundamental problem with encoding multiple signals using firing rates that no switching scheme can avoid. This is the problem of keeping firing rates positive. As discussed above, each signal corresponds to a mean firing rate plus positive and negative fluctuations about this mean. Although the mean rate carries no information about the signal, it cannot be set to zero or half of the signal would be lost due to firing-rate rectification. Adding together M signals, results in a total input that has a mean proportion to M and a fluctuating signal that is only proportion to because the M signals are independent of each other. Thus, there is a strong tendency for the mean input to drown out the signals to which we want the postsynaptic neuron to respond27. Of course, because of the balancing inhibition, the mean excitatory input is canceled, but this cancellation is subject to fluctuations due to the spiking nature of the inputs. As a result, there is a fundamental limitation in the number of signals from which a single signal can be extracted, independent of the method by which this is done.

To show that the limited capacity seen in Fig. 7a & b is a result of this fundamental restriction on firing-rate coding, and not a limitation of the detailed balance approach, we restricted the number of signals present on the afferents to the neuron at any given time. In other words, we set up the postsynaptic neuron so that it could extract any one out of M input signals, but at any given time we restricted the number of signals present to 5 out of these M possibilities (Fig. 7c). This seems like a reasonable situation for in vivo switching. Out of the myriad of possible stimuli that can activate a neuron, only a few are likely to be present at any given time. The number 5 is arbitrary, the key is to restrict the number of signals at any given time to a number that does not make the signals undetectable due to the problem discussed above. When the input signals are restricted in this way, the capacity is still limited when each afferent is only allowed to carry one signal, but when each signal is distributed across 40 afferents, the switching capacity is enormous (Fig. 7c,f). There is no decrease in similarity for the gated on signal over the entire range from 1 to 600 possible signals. This shows that the limited performance for the one-signal-per-afferent case in Fig. 7a is a result of having too few afferents per signal. On the other hand, the poor performance when 40 afferents are used per signal in Fig. 7b does not represent a limitation of detailed-balance gating, but rather a basic limitation of rate-based coding. When this latter limitation is avoided, detailed balance can switch extremely large numbers of signals.

Discussion

We have proposed an extension of the concept of global balance that offers an alternative to the more traditional model of gating by using inhibitory neurons to deactivate a signaling pathway28,29,14. This inverts the usual scheme of allowing signal propagation by default and disrupting the signal flow to gate a pathway off. Instead in our model, the balanced gated off state is the default. In complex networks, gating presumably occurs in parallel along the multiple pathways responsible for transmitting different aspects of a stimulus. It may be easier for a system to keep track of what is interesting in a broad band signal stream, than to keep track of all the uninteresting stimulus features that should be suppressed. If one feature of a stimulus warrants further processing, a control mechanism can select it by unbalancing its respective module, allowing the signal to propagate further downstream. We used gain modulation to unbalance signal-carrying pathways and gate signals on, but ordinary subtractive inhibition of inhibitory interneurons could also be used in our scheme.

Other discussions of signal switching in balanced neural circuits, either by shifting inhibition or through gain modulation, can be found in Refs. 2, 19 and 30. Continuous temporally and strengthwise correlated (balanced) excitatory and inhibitory input activity has been reported in vivo through recordings from pairs of pyramidal cells in the rat somatosensory cortex during spontaneous and sensory-evoked activities31. It has also been demonstrated that inhibition can be used to adjust the gain of a downstream circuit that receives balanced input, and thus control behavioral responses in a context-dependent manner32. These findings fit well into the framework of our hypothesis.

Although we found that gating is robust to a number of perturbations, it would be interesting to study how a homeostatic mechanism might impose and maintain a detailed balance. Spike-timing dependent plasticity has been shown to generate a global balance between excitation and inhibition33,34, but detailed balanced is likely to require some additional competitive as well as homeostatic mechanisms. In developing systems, this might involve tuning AMPA and immature, excitatory GABA synapses to the same degree.

Failure to maintain a precise balance between excitation and inhibition due to various abnormalities of synaptic transmission is commonly hypothesized as a basis for mental disorders such as schizophrenia35–39 and autism40,41. While it is natural to think that such an imbalance might lead to basic instabilities, such as those associated with epilepsy, it is more difficult to understand how they would lead to cognitive and behavioral disorders. Our results provide a suggestion. If we associate the local inhibitory neurons in our model network with parvalbumin positive (PV+) inhibitory neurons in cortex, the failure of gating in this model with reduced inhibition (Fig. 5c) could provide a functional basis for the hypothesis that reduced GABA production in PV+ interneurons may contribute to gating problems in schizophrenia35. Similarly, the inability to discriminate between external and internal activity could be related to the hallucinations and delusions that have been hypothesized to arise from defective dopaminergic regulation36,37 or NMDA current anomalies38. Although these latter anomalies correspond to hypofunction of NMDA conductances, this is associated with a hyper-excitability of the affected circuits39, so we modeled the overall effect by increasing excitation (Fig. 5d).

The mechanism we have proposed makes a distinctive prediction concerning inhibitory activity in a signal receiving region. Although excitatory neurons receiving a signal should respond more vigorously in an attentive (gating on) than in a non-attentive (gating off) state, at least some local inhibitory interneurons should follow a signal more reliably in the inattentive state, and decorrelate their activity from the stimulus with attention.

In studying the capacity of detailed balance to switch multiple signals, we ran into a fundamental limitation of multi-signal coding by firing rates that affects any switching scheme. However, once this limitation was avoided by keeping too many of the possible signals from being present at any given time, we found an enormous capacity to gate multiple signals. Thus, detailed balance offers a powerful and dynamic way of controlling signal flow in complex and multiply interconnected circuitry.

Methods

Neuron Model

The model used for all our simulations is a leaky integrate-and-fire neuron, characterized by a time constant, τ = 20 ms, and a resting membrane potential, Vrest = −60 mV. Whenever the membrane potential crosses a spiking threshold of −50 mV, an action potential is generated and the membrane potential is reset to the resting potential, where it remains clamped for a 5 ms refractory period. To set the scale for currents and conductances in the model, we used a membrane resistance of 100 MΩ.

We modeled synapses onto each neuron as conductances, so the sub-threshold membrane voltage obeys

Reversal potentials are Eex = 0 mV and Einh = −80 mV. The synaptic conductances gex and ginh are expressed in units of the resting membrane conductance. When the neuron receives a presynaptic action potential, the appropriate postsynaptic variable is increased, gex → gex Δ gex for an excitatory spike and ginh → ginh + Δginh for an inhibitory spike. Otherwise, these parameters obey the equations

with synaptic time constants τex = 5 ms and τinh = 10 ms. Ib is a constant background current used to maintain network activity (see below). The integration time step for our simulations was 0.1 ms. All simulations were programmed in C.

Network Architecture

The network we studied is composed of 20,164 leaky integrate-and-fire neurons, laid out on a 1422 grid. Neurons are either excitatory or inhibitory. The ratio of inhibitory neurons is roughly one in four, but the geometric organization of neurons on the grid constrains the final numbers to 15,123 excitatory cells and 5,041 inhibitory cells. Inhibitory neurons are divided into two groups of 3,361 and 1,680 neurons that differ in their connectivity pattern. All excitatory neurons and 65% of the inhibitory neurons have a random connectivity of 2% to the rest of the network (red cells in Fig. 1a). The 1,680 inhibitory neurons of the second group each target 40% of their 500 closest neighbors and thus act locally42 (blue cells in Fig. 1a). To avoid boundary effects, the network has the topology of a torus. We used 20,000 cells because this was the largest network that we could study within reasonable computation times. It has been shown previously that the activity in such networks becomes independent of size at about 10,000 neurons8,11,16. Other network parameters were chosen in keeping with both general properties of cortical circuits and previous work11,12,14,16,42.

Signal Path

In additional to the general architecture, we introduced a specific pathway from one region of the network to another, which we call sender and receiver subnetworks (green and red area in Fig. 1b respectively). The two subnetworks are chosen to be sufficiently distant from each other to exclude possible interactions through local inhibitory neurons. Synapses from a given excitatory sender neuron are allocated to contact either the excitatory or the locally inhibitory neurons of the receiver region, but not both. This division is made for the sake of tuning simplicity. The numbers of neurons and projecting synapses for the sender subnetwork were chosen to supply each of the ~500 excitatory receiver and ~70 inhibitory receiver neurons with 50 synapses from the sender subnetwork, a number necessary for critical spike propagation with appropriate tuning of synaptic strengths (see below). In addition, the number of neurons in both subnetworks was chosen to be as large as possible without interfering with overall network activity during signal propagation14. The final numbers are: 494 excitatory-excitatory sender neurons, 234 excitatory-inhibitory sender neurons, 463 excitatory receiver neurons and 73 inhibitory receiver neurons.

Tuning Conditions

Except for synapses along the signaling pathway, and those mentioned further below, all synapses of the same cell type had the same strength. A background current (Ib ) of 0.03 nA was delivered to every neuron and the three sets of strengths were adjusted to allow asynchronous background activity within the network. The postsynaptic conductances of correspond to 0.5 mV EPSPs and −0.4 mV and −1.1 mV IPSPs respectively, as obtained from spike triggered averages in the active network. To propagate signals from the sender subnetwork to the excitatory receiver subnetwork, we set the synapses between those two groups to = 0.9 nS. The synapses between sender neurons and inhibitory receiver neurons were left unchanged, and the inhibitory synapses between the inhibitory and the excitatory neurons in the receiver subnetwork were strengthened to = 4.65 nS. The extra tonic excitation that the inhibitory receiver neurons receive from background activity through the projections from the sender subnetwork was compensated by strengthening global inhibition to these cells to = 9.4 nS. Under these conditions the system is sufficiently balanced to prevent correlated inputs in the sender subnetwork from modulating the firing pattern of the excitatory receiver subnetwork.

To allow propagation, the balance between the excitatory and the inhibitory signal was modified by decreasing the gain of the inhibitory receiver neurons. In integrate-and-fire neurons such a gain change is equivalent to reducing the strength of all synapses by 85% in the case of symmetric gain changes and by 30% in the asymetric case in which only the response amplitude to excitatory inputs is altered. These values were chosen to minimize similarity values in the gated-off state (Fig. 4a).

To compensate for cell loss (Fig. 4c), we calculated the decrease of over-all synaptic strength and redistributed the difference equally among the remaining synapses in the pathway. The gating mechanism can function with only 20 inhibitory receiver neurons when we strengthen their synapses threefold to 15 nS (approximately the same strength as two globally inhibitory neurons) and allowed them to fire at rates of up to 600 Hz (Fig. 4d).

Two input signals

To propagate and control an additional signal to the receiver region, a second inhibitory receiver subnetwork is necessary. Some of the globally acting inhibitory neurons in the receiver region can be recruited as locally inhibitory for that purpose by generating a new local architecture for them. An additional set of Poisson input spike trains is generated and connected synaptically to both the shared excitatory receiver subnetwork and the new inhibitory receiver subnetwork. As before, the synapses of the Poison population are tuned to drive their respective target subnetworks in the absence of additional correlated signal input. To balance two active signals at the same time, some of the synapses within the network must also be retuned. See Table 1 for a complete listing of all modified synapses.

Table 1.

Synapse Modifications: Overview of synaptic alterations, sorted by synapse type (rows) and purpose of modification (columns). The synaptic strengths appearing in column 2 were multiplied by the factors appearing in columns 4, 5 and 6. The asterisk indicates that this value is 3.1 times the scaled value (scaled by 0.4).

| Synapse Groups | Healthyc | Inh. Deficit | Hyperex. Receiver | 2 Signals | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.8 nS | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.9 | ||||

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 1.0 | |||||

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | |||||

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 1.3 | |||||

| 1.5 nS | All | 1.0 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| 3.1 | 3.1* | 3.1 | 3.3 | |||||

| 4.0 | ||||||||

| 7.5 nS | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.32 | ||||

| 1.2 | ||||||||

| 0.75 |

Pathologies

We chose two ways to disrupt the detailed balance mechanism, which are summarized in Table 1. First, a deficiency in the locally inhibitory neurons, including those of the inhibitory receiver subnetwork, was introduced by decreasing their synaptic strengths to = 0.6 nS. Second, we induced a hyper-excitability of the receiver region by increasing all the excitatory synapses from the rest of the network onto the receiver neurons to = 1.28 nS and = 1.28 nS. These two manipulations are independent and can be combined without retuning.

Multiple input signals to a single cell

In the later part of the paper, we modeled the gating of multiple signals in a single integrate-and-fire cell that receives 800 excitatory and 200 inhibitory synapses modeled as Poisson processes with temporally changing spiking probabilities. To avoid unrealistically high membrane currents when many inputs arrive at the cell, synaptic strengths are tuned down to Δgex = 0.014 nS and Δginh = 0.044 nS with PSPs of 0.13 mV and −0.22 mV at Vrest, respectively. When we drove each afferent with more than one signal, the overlap (effectively a summation of spiking probabilities for each synapse) demanded a rescaling of the input rates to a dynamic signal range between 0 and 150 Hz.

The following procedure is used to compute the inhibitory gain factors needed to gate on one signal among many. First, to specify which signal is connected to which inhibitory afferent, we define an N by M matrix B with Bia = 1 if inhibitory afferent i receives signal a and Bia = 0 if it does not. The total inhibitory input due to signal a is then Ca = ΣiBia. We next choose a particular signal, say signal 1, to gate on. We do this by setting the gains for all the inhibitory neurons receiving signal 1, that is all neurons with Bi1 = 1, to zero. We then adjust the firing-rates (gains) of the remaining inhibitory afferents to compensate for these missing afferents for all other signals (missing because their gains are zero). If n afferents receive signal 1, we define an N−n by M−1 matrix B̃, which is just B with signal 1 and all of the afferents connected to signal 1 removed. Define C̃ to be a vector with M−1 components given by C̃a =Ca+1 for a=1,2,K M−1. The inhibition missing because the afferents receiving signal 1 have been turned off can be replaced if the firing rates of the afferents not receiving signal 1 are multiplied by a row vector of gain factors α such that αB̃=C̃. This equation is “solved” in the sense of minimizing the square of the difference between the two sides summed over a, by setting α=pinv(B̃) C̃, where pinv(B̃) is the pseudo-inverse of B̃. The gains of all inhibitory afferents receiving signal 1, on the other hand, are set to zero. This determines the complete set of gains used to gate signal 1 on and leave all other signals off. To gate signal 1 off, all the gains are set to 1. A similar procedure is used for any other signal that we wish to gate.

Response Properties of the Balance Mechanism

To supply a signal to the network, we generated Poisson input spike trains with a firing rate r0 (t) as a source of input to the network. Each input spike generated by that group increased the excitatory synaptic conductances in neurons of the sender region by gex → gex + Δg0. The synaptic strength Δg0 was tuned so that the firing rates of the sender neurons reproduced the input signal, that is, they tracked the input firing rate r0 (t).

We used a correlation measure12,14 to determine how similar firing rates in the receiver region were to the input. To do this, we calculated the population firing rate r(t) in 5 ms bins by counting spikes and also determined its time-average value r̄. The correlation is then

where the brackets denote an average over time, r0 (t) and r̄0 are the firing rate and average for the input, and σri σr0 are the standard deviations of the corresponding firing rates. We used the activity of the input as a reference rather than the sender subnetwork to distinguish signal transmission from propagation of fluctuations arising in the sender. Signal propagation between subnetworks is then characterized by reporting the maximum value (over τ) of C(τ), which we call the similarity14. For the analysis of multi-signal gating in a single integrate-and-fire cell, we used a similarity measure that was not normalized by σri to avoid overestimating the quality of the output signal in cases when the output firing rate was greatly diminished.

Acknowledgments

The idea of detailed balance was originally suggested to us by Gina Turrigiano. Research supported by the National Science Foundation (IBN-0235463), the Swartz Foundation, the Patterson Trust Fellowship Program in Brain Circuitry and by an NIH Director's Pioneer Award, part of the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, through grant number 5-DP1-OD114-02. Thanks to Jonathan Peelle, Max Schiff, Pablo Jercog, Rafael Yuste, and the anonymous referees for helpful suggestions.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Shu Y, Hasenstaub A, McCormick DA. Turning on and off recurrent balanced cortical activity. Nature. 2003;423:288–293. doi: 10.1038/nature01616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haider B, Duque A, Hasenstaub AR, McCormick DA. Neocortical network activity in vivo is generated through a dynamic balance of excitation and inhibition. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:4535–4545. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5297-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shadlen MN, Newsome WT. Noise, neural codes and cortical organization. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1994;4:569–579. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(94)90059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Troyer TW, Miller KD. Physiological Gain Leads to High ISI Variability in a Simple Model of a Cortical Regular Spiking Cell. Neural Comput. 1997;9:971–983. doi: 10.1162/neco.1997.9.5.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amit DJ, Brunel N. Model of global spontaneous activity and local structured activity during delay periods in the cerebral cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 1997;7:237–252. doi: 10.1093/cercor/7.3.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Vreeswijk C, Sompolinsky H. Chaos in neuronal networks with balanced excitatory and inhibitory activity. Science. 1996;274:1724–1726. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunel N. Dynamics of networks of randomly connected excitatory and inhibitory spiking neurons. J. Physiol. Paris. 2000;94:445–463. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(00)01084-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar A, Schrader S, Aertsen A, Rotter S. The high-conductance state of cortical networks. Neural Comput. 2007;20:1–43. doi: 10.1162/neco.2008.20.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abeles M. Corticonics: neural circuits of the cerebral cortex. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1991. 280 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aertsen A, Diesmann M, Gewaltig MO. Propagation of synchronous spiking activity in feedforward neural networks. J. Physiol. Paris. 1996;90:243–247. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(97)81432-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diesmann M, Gewaltig MO, Aertsen A. Stable propagation of synchronous spiking in cortical neural networks. Nature. 1999;402:529–533. doi: 10.1038/990101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Rossum MC, Turrigiano GG, Nelson SB. Fast propagation of firing rates through layered networks of noisy neurons. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:1956–1966. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01956.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vogels TP, Rajan K, Abbott LF. Neural Networks Dynamics. Ann. Rev. Neurosci. 2005;28:357–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vogels TP, Abbott LF. Signal Propagation and Logic Gating in Networks of Integrate-And-Fire Neurons. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:10786–10795. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3508-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Destexhe A, Contreras D. Neuronal computations with stochastic network states. Science. 2006;314:85–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1127241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar A, Rotter S, Aertsen A. Conditions for propagating synchronous spiking and asynchronous firing rates in a cortical network model. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:5268–5280. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2542-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Posner MI, editor. Cognitive Neuroscience of Attention. NY: Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Germuska M, Saha S, Fiala J, Barbas H. Synaptic distinction of laminar-specific prefrontal-temporal pathways in primates. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16:865–875. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salinas E. Context-dependent selection of visuomotor maps. BMC Neuroscience. 2004;5:47–68. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-5-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Disney AA, Aoki C, Hawken MJ. Gain modulation by nicotine in macaque v1. Neuron. 2007;56:701–713. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Disney AA, Aoki C. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in macaque V1 are most frequently expressed by parvalbumin-immunoreactive neurons. J. Comp. Neurol. 2008;507:1748–1762. doi: 10.1002/cne.21616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Disney AA, Domakonda KV, Aoki C. Differential expression of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors across excitatory and inhibitory cells in visual cortical areas V1 and V2 of the macaque monkey. J. Comp. Neurol. 2006;499:49–63. doi: 10.1002/cne.21096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiang Z, Huguenard JR, Prince DA. Cholinergic switching within neocortical inhibitory networks. Science. 1998;281:985–988. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5379.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gil A, Connors BW, Amitai Y. Differential regulation of neocortical synapses by neuromodulators and activity. Neuron. 1997;19:679–686. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80380-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell JF, Sundberg KA, Reynolds JH. Differential attention-dependent response modulation across cell classes in macaque visual area V4. Neuron. 2007;55(1):131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Binzegger T, Douglas RJ, Martin KA. A quantitative map of the circuit of cat primary visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:8441–8453. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1400-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abbott LF. Theoretical neuroscience rising. Neuron. 2008;60:489–495. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson CW, Van Essen DC. Shifter circuits: a computational strategy for dynamic aspects of visual processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:6297–6301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.17.6297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olshausen BA, Anderson CH, Van Essen DC. A neurobiological model of visual attention and invariant pattern recognition based on dynamical routing of information. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:4700–4719. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-11-04700.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pouille F, Scanziani M. Routing of spike series by dynamic circuits in the hippocampus. Nature. 2004;429:717–723. doi: 10.1038/nature02615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okun M, Lampl I. Instantaneous correlation of excitation and inhibition during ongoing and sensory-evoked activities. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11(5):535–537. doi: 10.1038/nn.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baca SM, Marin-Burgin A, Wagenaar DA, Kristan WB., Jr Widespread inhibition proportional to excitation controls the gain of a leech behavioral circuit. Neuron. 2008;57:276–289. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song S, Miller KD, Abbott LF. Competitive Hebbian Learning Through Spike-Timing Dependent Synaptic Plasticity. Nature Neurosci. 2000;3:919–926. doi: 10.1038/78829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morrison A, Aertsen A, Diesmann M. Spike-timing-dependent plasticity in balanced random networks. Neural Comput. 2007 Jun;19(6):1437–1467. doi: 10.1162/neco.2007.19.6.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis DA, Hashimoto T, Volk DW. Cortical inhibitory neurons and schizophrenia. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006;6:312–324. doi: 10.1038/nrn1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seeman P. Dopamine receptors and the dopamine hypothesis of schozophrenia. Synapse. 1987;1:133–152. doi: 10.1002/syn.890010203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moore H, West AR, Grace AA. The regulation of forebrain dopamine transmission: relevance to the pathophysiology and psychopathology of schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry. 1999;46:40–55. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tamminga C. Schizophrenia and glutamatergic transmission. Crit. Rev. Neurobiol. 1998;12:21–36. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v12.i1-2.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jackson ME, Homayoun H, Moghaddam B. NMDA receptor hypofunction produces concomitant firing rate potentiation and burst activity reduction in the prefrontal cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:8467–8472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308455101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rubenstein JL, Merzenich MM. Model of autism: increased ratio of excitation/inhibition in key neural systems. Genes Brain Behav. 2003;2:255–267. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-183x.2003.00037.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tabuchi K, Blundell J, Etherton MR, Hammer RE, Liu X, Powell CM, Sudhof TC. A neuroligin-3 mutation implicated in autism increases inhibitory synaptic transmission in mice. Science. 2007;318:71–76. doi: 10.1126/science.1146221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aviel Y, Mehring C, Abeles M, Horn D. On embedding synfire chains in a balanced network. Neural Comput. 2003;15:1321–1340. doi: 10.1162/089976603321780290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]