Abstract

Rationale and Objectives

Existing cardiac imaging methods do not allow for improved temporal resolution when considering a targeted region of interest (ROI). The imaging method presented here enables improved temporal resolution for ROI imaging (namely, a reconstruction volume smaller than the complete field of view). Clinically, temporally targeted reconstruction would not change the primary means of reconstructing and evaluating images, but rather would enable the adjunct technique of ROI imaging, with improved temporal resolution compared with standard reconstruction (~20% smaller temporal scan window). In gated cardiac CT scans improved temporal resolution directly translates into a reduction in motion artifacts for rapidly moving objects such as the coronary arteries.

Materials and Methods

Retrospectively electrocardiogram gated coronary angiography data from a 64-slice CT system were utilized. A motion phantom simulating the motion profile of a coronary artery was constructed and scanned. Additionally, an in vivo study was performed using a porcine model. Comparisons between the new reconstruction technique and the standard reconstruction are given for an ROI centered on the right coronary artery, and a pulmonary ROI.

Results

In both a well controlled motion model and a porcine model results show a decrease in motion induced artifacts including motion blur and streak artifacts from contrast enhanced vessels within the targeted ROIs, as assessed through both qualitative and quantitative observations.

Conclusion

Temporally targeted reconstruction techniques demonstrate the potential to reduce motion artifacts in coronary CT. Further study is warranted to demonstrate the conditions under which this technique will offer direct clinical utility. Improvement in temporal resolution for gated cardiac scans has implications for improving: contrast enhanced CT angiography, calcium scoring, and assessment of the pulmonary anatomy.

Keywords: Cardiac CT, Super-short Scan, Region-Of-Interest Imaging, Targeted Reconstruction

Introduction

The use of electrocardiogram (ECG) gated computed tomography (CT) in the assessment of coronary artery disease has been rapidly escalating in recent years, and is increasingly recognized as an accurate, noninvasive means to detect obstructive coronary artery disease (1). The utility of cardiac CT has been demonstrated in both calcium scoring and contrast enhanced coronary angiography (2). It has been recommended that calcium scoring be applied to the asymptomatic population for risk assessment; while CT angiography may serve as an alternative or adjunct to invasive coronary catheterizations for a subset of symptomatic patients (1, 2). Scanning with state-of-the-art 64 slice MDCT scanners has demonstrated a high negative predictive value for the identification of significant lesions (i.e. those stenoses that are greater than 50%) (1, 3), thereby demonstrating significant clinical utility of 64 slice MDCT scanners. In order to lower the heart rate, β blocker medication is routinely prescribed to the patient prior to scanning. However, due to the intrinsic requirement for mechanical rotation of both the source and detector in MDCT scanners, motion blurring can still occur in the reconstructed coronary angiography images. In a recent study using a state-of-the-art 64-slice scanner, some motion artifacts were present in approximately one-half of the examined coronary segments, and moderate motion artifacts were present in 14% of the examined coronary segments (4). To combat these artifacts one vendor recently released a dual source scanner (5) which offers significant gains in temporal resolution. However, since there is currently a large installation base of single source scanners the task of improving image quality on these scanners is of significant consequence. Therefore, a need remains to improve upon the current image reconstruction techniques for single source CT scanners. The technique proposed in this work enables improved temporal resolution for regions of interest (ROIs).

Standard clinical reconstruction of the entire field of view (FOV) requires projection data acquired over an angular range of 180° plus the angle covered by the fan beam (“fan angle”) (6). Current state-of-the-art cardiac imaging methods do not allow for improved temporal resolution when considering a targeted ROI. Recently, it has been shown that reconstruction of an ROI is possible with a reduced angular scan range (7–9). By reducing the angular range required to reconstruct ROI images, the temporal resolution is improved and motion artifacts are reduced. Thus, we refer to this technique as Spatially and Temporally Targeted Reconstruction (STTaR).

In this work we demonstrate the first controlled motion phantom experiments on a clinical system and the first in vivo results utilizing STTaR.

Clinically, STTaR would be offered as a complementary tool when reviewing image data. We envision STTaR’s niche in clinical scanning as follows. First, the standard scan protocol and standard image reconstruction will be used, and state-of-the-art methods of visualizing and analyzing the data will be employed. Second, temporally targeted ROI reconstruction can be performed for improved visualization of targeted vessels. In clinical practice the ROIs may be either manually selected or an automated procedure may be utilized.

In addition to evaluation of the coronary arteries, other important information may be obtained from theses exams. For example the increased longitudinal detector coverage has enabled simultaneous evaluation of the heart, aorta and pulmonary arteries in a single breath hold. Known as the “triple rule out”, these exams evaluate the entire cardiopulmonary system and have been proposed as a means of rapidly triaging patients to assess both coronary and non-coronary chest pain (10). Additionally, when performing CT cardiac imaging the number of incidental findings has been significant. It has been recently shown that important or emergent findings were present in nearly one quarter of all dedicated coronary CTA exams (11). Therefore, it is also critical to provide diagnostic quality images in anatomy other than just the coronary arteries, such as the lungs. Thus, in this work imaging results will be presented for both cardiac and lung based ROIs to demonstrate the applicability of STTaR to both sites.

Materials and Methods

Controlled Motion Phantom

A motion phantom was constructed to simulate vessel motion using a simplified motion profile. In order to provide reasonable x-ray attenuation a standard quality assurance CTDI phantom was employed (i.e. a 16 cm diameter uniform acrylic phantom). The simulated ‘vessel’ of interest was a nylon rod of 1.6 mm diameter and a length of 3.5 cm. A manually driven vertical stage (Velmex, Bloomfield, NY) was used to position the vessel within the central hole of the CTDI phantom. A second stage (Velmex, Bloomfield, NY) was used to generate the motion profile of repeated side to side motion. The ‘vessel’ was attached to a 23 cm long nylon rod to keep the linear stages out of the field of view. In order to achieve a smooth motion profile a servo motor was employed and controlled by an Aries servo driver (Parker Hannifin, Rohnert Park, CA). The servo driver was operated in the velocity control mode where the desired velocity profile may be input as a voltage signal. The voltage signal used here was produced by a synthesized function generator (Global Specialties, Cheshire, CT). The voltage signal driving the stages was digitized using a USB data acquisition device (Labjack, Lakewood, CO). The digitized motion profile is shown in Figure 1. The motion profile assumes a rest period of 20%, followed by a sinusoidal velocity profile (similar to the motion model used in Ref. (12)). In this work we have simulated a heart rate of 60 beats per minute, and the peak vessel velocity is nearly 8 cm/s (within the range of measured coronary velocities (13–15)). Several positions within the cardiac cycle have been labeled in Figure 1 for reference as they will be referred to when the reconstruction results are presented. Reconstructed images of the phantom at different cardiac phases were used to estimate the degree of motion induced artifacts for the standard and STTaR reconstructions. Finally, noise measurements were made to validate the expected increase in quantum noise in the STTaR algorithm as less projection data is utilized for each reconstruction.

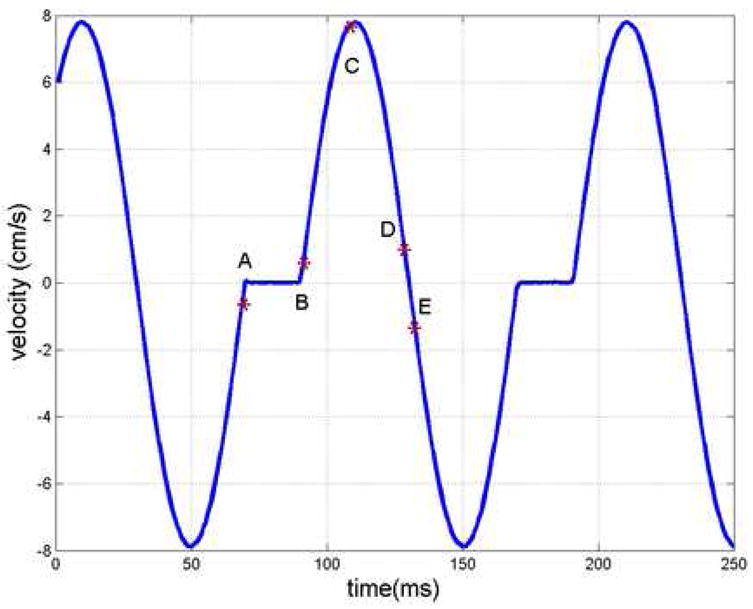

Figure 1.

The digitized velocity profile prescribed to simulate vessel motion during the cardiac cycle. The units on the ordinate have been converted from voltage to velocity by the constant factor prescribed to the servo driver. The letters labeling different positions in the cardiac cycle will be used as reference for the subsequent reconstruction results.

Porcine Model

The prospect of improved ROI reconstruction using STTaR techniques was explored using x-ray projection data acquired from an anesthetized male 47 kg swine. The protocol utilized in this animal study was approved by the institutional review board, and complies with the guidelines for care of animals given by the National Institutes of Health. The swine was anesthetized initially with a combination of 4 mg/kg telazol IM and 2 mg/kg xylazine IM. An ear vein line was used for the administration of thiopental 8 mg/kg IV to enable tracheostomy. The tracheostomy was performed and the pig was attached to an anesthesia machine and ventilated with ~2% isoflurane. A 50-second continuous axial scan was performed using a power injection of 75 cc iodixanol (Visipaque 320 mg I/mL, Amersham Healthcare http://www.amersham.com) at a rate of 8 cc/sec. Data acquisition was initiated after a five-second delay. Note that only a small fraction of this data was utilized in the results presented here and by no means would a 50 second scan be required clinically. The ventilator was turned off during the acquisition to prevent respiratory motion, and the ECG signal was simultaneously recorded. The heart rate was approximately 83 beats/min during the acquisition presented in this work. An example full FOV reconstruction is given in Figure 2(a) in order to demonstrate the porcine cardiac anatomy.

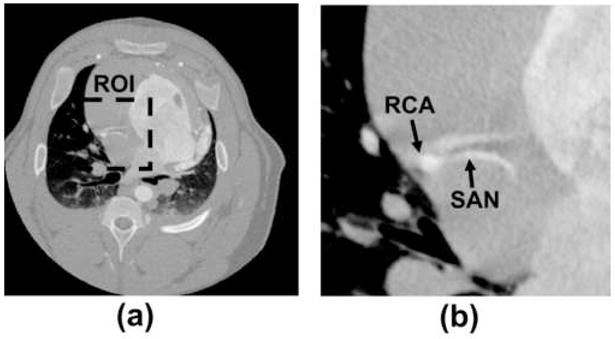

Figure 2.

(a) The central image slice full FOV reconstruction to demonstrate the porcine coronary anatomy. As an example in this work we demonstrate the concept of temporally targeted reconstruction STTaR for the ROI given by the dashed line. (b) The right coronary artery and the sinoatrial nodal artery (SAN) are contained within this ROI.

Scan Parameters

All of the scans were performed on a state-of-the-art clinical 64-slice MDCT scanner (GE Healthcare Lightspeed VCT, Waukesha, Wisconsin) installed at the University of Wisconsin hospital (Madison, WI). In both the phantom and porcine acquisitions a ‘cine mode’ with a 0.4 second gantry rotation period was employed. The porcine scan was performed with x-ray parameters of 120 kVp and 500 mA. Since the acrylic phantom is significantly less attenuating than the porcine model the mA was adjusted based on the approximate path length ratio, thus x-ray parameters of 120 kVp and 300 mA were used for the phantom experiments.

Image Reconstruction

The proposed STTaR technique for coronary imaging will be described first in the context of an axial acquisition. In order to exactly reconstruct the entire FOV in fan-beam tomography a short scan data acquisition is required (i.e. 180° + fan angle) (6). This reconstruction may be performed either by rebinning the projection data to the parallel beam geometry or by pre-weighting the fan-beam data before performing a fan-beam reconstruction (6, 16).

It has been demonstrated that projection data acquired over a smaller angular range (i.e. less than 180° + fan angle) are sufficient for an exact reconstruction of an ROI within the FOV (7–9). This technique is often referred to as a super-short scan in the reconstruction literature. In MDCT the acquisition time directly dictates the temporal resolution of the images, and therefore, targeted ROI reconstruction methods have the potential to reduce motion artifacts because data acquired over a smaller angular range is required for reconstruction.

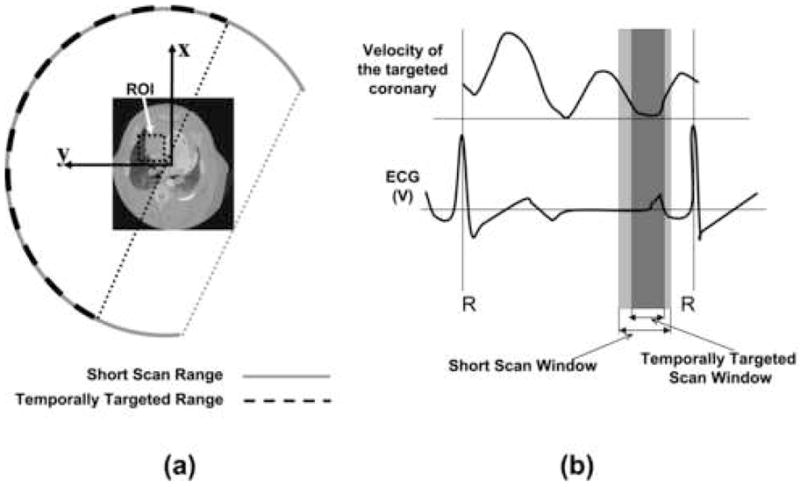

An ROI will be selected, from the standard reconstructed image (e.g. the short scan reconstruction), either manually or using an automated procedure to determine which ROIs would benefit most from STTaR. A demonstration of STTaR is given in Figure 3. In this case, the ROI is centered about the RCA. The reduction in the angular range of projection data required for STTaR is demonstrated in (a). The required range of projection data for an exact reconstruction is given by connecting the two end-points of the scanning segment (the dotted lines in Figure 3(a)) and ensuring that the desired ROI is within this bounded area. Therefore, to reconstruct the entire FOV the angular range of required data is significantly greater than the range required to apply STTaR to the ROI. The reduction in the range of projection data required directly yields a decrease in the temporal window required to perform the data acquisition (Figure 3(b)). On average a reduction in the scan temporal window of approximately 20% may be achievable. Thus, one may expect a reduction in motion artifacts will be achieved by improving the temporal resolution of the scanner for ROI imaging. The temporal resolution improvement is dependent upon the size and position of the ROI.

Figure 3.

The required angular scan range for the short scan and the temporally targeted scan are shown in (a). For this sample ROI analytic reconstruction supported using the data highlighted by the dashed line, while for reconstruction of the entire field of view the angular range is given by the solid line. The time required to obtain the projection data is shown with respect to a hypothetical ECG signal and a schematic motion profile (b). The wider (light) region corresponds to the full field of view reconstruction, while the central (dark) region corresponds to the temporal window for the temporally targeted reconstruction.

The axially acquired 64-row data has been reconstructed using an extension of the fan-beam filtered backprojection algorithm via the application of a geometrical weighting and cone-beam backprojection proposed by Feldkamp, Davis and Kress (FDK) (17). The super-short scan reconstruction framework (used here to provide temporal targeting) has been described in detail in the reconstruction literature (7, 8, 18–21). The fan-beam reconstruction formula utilized for STTaR in this work is given by Eq. 33 of Ref (7) and Eq. 40 of Ref. (8) The weighting function used here was from Eq. 29 and Eq. 46 of Ref (7). The reconstruction steps are explicitly described in the Appendix for completeness. The ‘gold-standard’ short scan reconstruction described in Ref. (16) was conducted for comparison with STTaR. In order to match the spatial resolution between the two reconstruction techniques for static objects, a window function ( , where k is the frequency parameter, and kN is the Nyquist frequency) was applied to the gold standard reconstruction (22).

In this study the raw projection data were pre-processed with the manufacturer’s software (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, Wisconsin), and image reconstructions were performed with in-house software (UW Madison) written in C++. We have employed multiple reconstruction grid spacings in the images presented here. All volumetric images were reconstructed with isotropic voxels. In the phantom studies a central ROI was imaged with voxels of linear dimension 0.06 mm. In the porcine model the full FOV images were reconstructed with voxels of linear dimension of 0.49 mm, and the ROI reconstructions were performed on a grid with linear dimension of 0.14 mm for each voxel. After reconstruction the images were analyzed to assess the potential benefits or disadvantages of STTaR, using both qualitative and quantitative metrics. Multiple ROIs were reconstructed in order to assess possible improvements for contrast enhanced coronary artery imaging, as well as contrast enhanced pulmonary artery imaging.

Given the volumetric nature of the reconstructed data multiple means of presenting the data were utilized including: thin transverse slices, maximum intensity projection images (MIPs), minimum intensity projection images, and volumetric rendering based on an isosurface of the reconstructed values. In all cases identical display parameters were used in comparing the images both with and without STTaR. The image display and processing for the thin slices, MIPs and minimum intensity projections was conducted using Matlab (Mathworks, Natick MA). Volume rendering was performed using GE Healthcare’s MicroView software.

Each of the ROI images generated from each of the presentation techniques mentioned above were independently reviewed by all authors who each qualitatively evaluated the motion artifacts in the ROIs both with and without STTaR. The reviewers qualitatively judged the motion contamination via the presence or absence of significant motion artifacts, as well as qualitatively determining the motion blur based upon how distinctly one could visualize the vessel edge. In all of the reconstructed ROIs there was agreement among the observers regarding which of the reconstructed volumes had a lower degree of motion contamination between the volumes with and without temporal targeting. Additionally, using the controlled motion phantom the ability of each algorithm to accurately reconstruct the moving ‘vessel’ was assessed both qualitatively and quantitatively. The degree of motion-induced streak artifacts was qualitatively observed for images reconstructed using data taken from different fractions of the cardiac cycle. After examining the reconstructed images contour plots were used to visualize the distortion in the shape of the reconstructed ‘vessel’ relative to the ideal circular cross section. An unconstrained non-linear optimization procedure (Matlab, Mathworks, Natick MA) was used to fit the contours in the reconstruction image (for a constant HU) to an ellipse. As a measure of distortion in the reconstructed images the eccentricity of each ellipse was calculated. The eccentricity of an ellipse may vary from 0 to 1, where the circular limit has an eccentricity of 0 and the line limit has an eccentricity of 1. For each image reconstruction algorithm 50 images were reconstructed by varying the position of the gating window utilized. The eccentricity values corresponding to the reconstructed images were compared for the two reconstruction algorithms. Additionally, noise measurements were made to validate the anticipated increase in quantum noise in the STTaR algorithm as less projection data is utilized for each reconstruction.

Results

Controlled Motion Phantom

STTaR intrinsically uses a smaller range of the projection data which leads directly to improved temporal resolution. Images of the motion phantom were reconstructed using the standard reconstruction algorithm with 643 views angles (261ms) to reconstruct each image. The STTaR used only 499 view angles (203ms) per reconstruction, resulting in a 22% shorter temporal window. Since the velocity of the coronary arteries and surrounding vessels is not constant throughout the cardiac cycle the improvement in temporal resolution has a varying impact on image quality at different points throughout the cycle. Here we present a comparison of conventional and STTaR images reconstructed for five different acquisition windows within the simulated cardiac cycle, centered on points A,B,C,D, and E in Figure 1. The motion profile consists of a static component (from 0% to 20% of the cycle) followed by a sinusoidal component (20% to 100%). The center positions of the five gating windows are A:96%, B:25%, C:39%, D:57%, and E:65%. Note these values pertain to the motion model and do not correspond to positions in the R-R interval of an actual ECG signal.

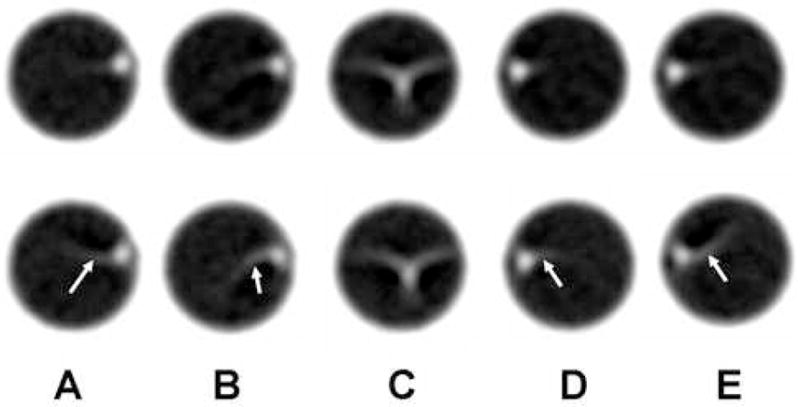

The images shown in Figure 4 compare the standard and STTaR reconstruction techniques. In these cross-sectional images the reconstructed vessel appears as a relatively bright compact object, and motion-induced artifacts arising from this object are visible. At gating points A, B, D, and E the STTaR images demonstrated a reduction in motion-induced artifacts compared to the standard short scan reconstructions (arrows in Figure 4). However, during the high-velocity portion of the cycle where motion-induced artifacts were most severe (point C) the improvement in temporal resolution with STTaR was not sufficient to dramatically alter the vessel appearance.

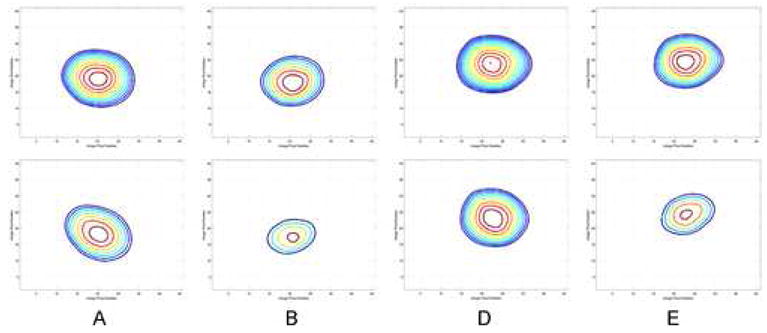

Figure 4.

A comparison between the STTaR phantom reconstructions (top row) and the standard reconstructions (bottom row). Each image corresponds to a different gating window (A–E) where the gating windows have been represented pictorially in Figure 1 by the labels (A–E).

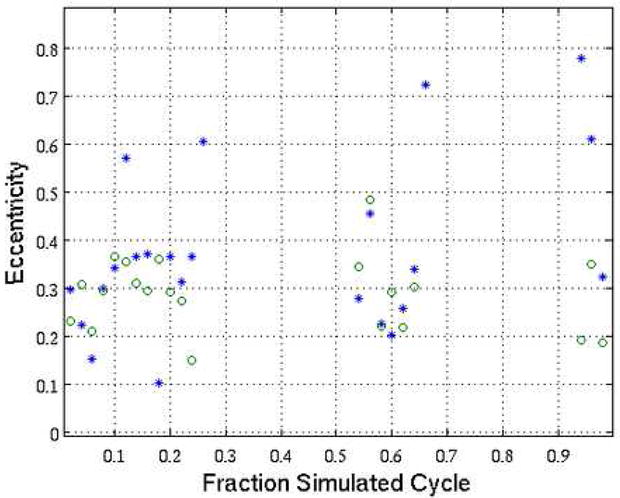

In the image reconstructions for points A, B, D, and E the circular shape of the vessel was clearly distorted. This is demonstrated in Figure 5 with contour plots of the vessel image instensity. In order to quantify the fidelity of the shape of the reconstructed ‘vessel’, the eccentricity of an elliptical fit to the outermost contour in the maps from Figure 5 was evaluated for acquisition windows centered at 50 points throughout the motion cycle (i.e. centered on 0%, 2%, 4%, etc.). The results are shown in Figure 6. For some portions of the motion cycle the reconstructed vessel did not take on an elliptical shape due to the extreme motion artifact (see for example Figure 4C) and a reliable fit could not be obtained. In the portions where a good fit was obtained the STTaR images had eccentricity values closer to 0 (the eccentricity of an ideal circle) and demonstrated better fidelity in vessel shape compared to the standard short scan reconstructions. The mean eccentricity of the data plotted in Figure 6 was 0.38 for the standard reconstruction and 0.32 for the STTaR reconstruction.

Figure 5.

The contour plots corresponding to the reconstructed images given in Figure 4(A,B,D,E). The top row results are contours from STTaR and the bottom row are contours from the standard reconstruction results. The outermost contour corresponds to −419 HU and each additional inner contour corresponds to an additional 16 HU.

Figure 6.

The eccentricity values of fits to the contours at −419 HU from reconstructions conducted with a gating window centered on the plotted positions in the simulated cycle. The standard reconstruction is represented by asterisk while the STTaR results are plotted with circles.

Since the STTaR technique will be used clinically as a retrospective technique in which a subset of the acquired data is utilized, fewer total photons are used in the reconstruction process and it is expected that the quantum image noise will be higher. Measurements of the voxel standard deviation were conducted in four homogeneous regions of the acrylic CTDI phantom outside of the central hole. Each region contained 900 voxels. All images for this analysis were acquired without ‘vessel’ motion in order to prevent motion induced streaks from influencing the quantum noise measurements. The ratio of the measured standard deviations was for the standard short scan reconstruction relative to STTaR reconstruction. The standard deviation in the reconstructed voxel values was expected to vary with an inverse square root dependence on the exposure, based on fundamental CT physics (23, 24). In this experiment 643 view angles were used for the standard reconstructions and 499 view angles were used for the STTaR case. No mA modulation was used in these acquisitions. Therefore, we expected the ratio of the standard deviations to be . Thus, the measured quantum fluctuations were slightly higher in the STTaR reconstruction results, and the experimental and theoretical ratios were in good agreement.

Porcine Model

A comparison of the effective data acquisition window (i.e. the time, the angular range, and the percentage of the RR interval) between STTaR and the short scan reconstruction for this acquisition is provided in Table 1. The full FOV temporal window was centered at %RR=0.68, and each STTaR image was generated with a subset of the data used for the full FOV image (Table 1). The results presented here will be separated into two sections based on the anatomy of interest. The improvements using STTaR will be given first for the coronary case, and then for the pulmonary case.

Table 1.

The temporal parameters of the projection data utilized for the temporally targeted and the standard short scan reconstruction. Note that the cardiac window is heart-rate dependent (ie. if the heart rate was reduced this ratio of the data acquisition period to the time between R waves would be reduced.)

| Temporally Targeted | Short Scan | |

|---|---|---|

| Angular Range | 180° | 235° |

| Cardiac Window (% RR) | 27 | 36 |

| Acquisition Time | 200 ms | 261 ms |

Coronary Region of Interest

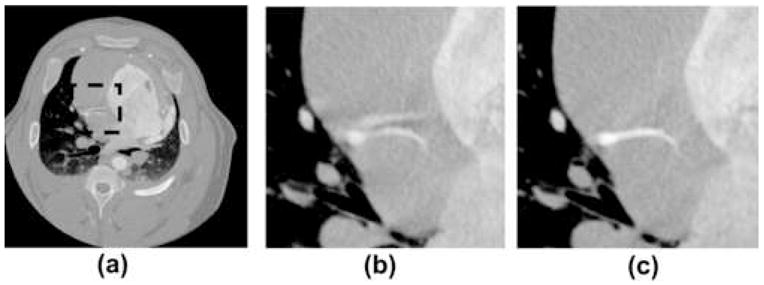

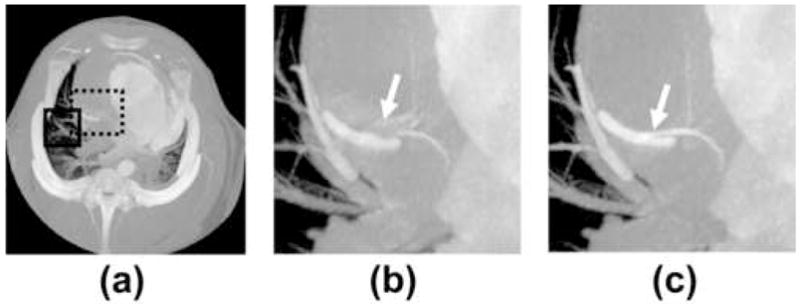

The ability of STTaR to reduce motion artifacts in the coronary arteries is demonstrated here via multiple presentations of the targeted ROI both with and without STTaR. The axial images of the full FOV along with the coronary ROI are given in Figure 7. The motion induced streaking artifacts which led to an artifactual vessel (Figure 7(b)) within this plane have been suppressed with STTaR (Figure 7(c)). This type of artifact may be due to the “atrial kick” causing this vessel to move in a biphasic manner resulting in two ‘dwell’ times (25). The ability of the STTaR technique to reduce the acquisition window may potentially reduce these artifacts. Maximum intensity projection images through the full FOV (Figure 8) as well as through the regions of interest (Figure 8 and Figure 9) also highlight the increased temporal resolution of STTaR. The arrows in the comparison images with and without temporal targeting show the improved vessel sharpness for STTaR, and the ability to visualize more bifurcations in the STTaR image. Finally, an isosurface rendering (Figure 10) illustrates the two additional bifurcations visible with STTaR as well as the lack of an artifactual vessel caused by motion induced streaking (see arrows in Figure 10).

Figure 7.

A comparison of single axial slice images with and without temporal targeting. (a) The axial slice of the short scan with the RCA ROI highlighted. (b) The standard spatially targeted ROI reconstruction. (c) The spatially and temporally targeted axial slice of the ROI. Display window [−1000 HU 1000 HU].

Figure 8.

Comparison of the MIPs through the coronary ROI in the z (SI) direction: (a) through the full field of view [0 HU 900 HU], (b) through the coronary ROI (dashed line) without temporal targeting [−590 HU 780 HU], and (c) through the coronary ROI with temporal targeting [−590 HU 780 HU]. Additionally in (a) the pulmonary ROI used is denoted by the solid line.

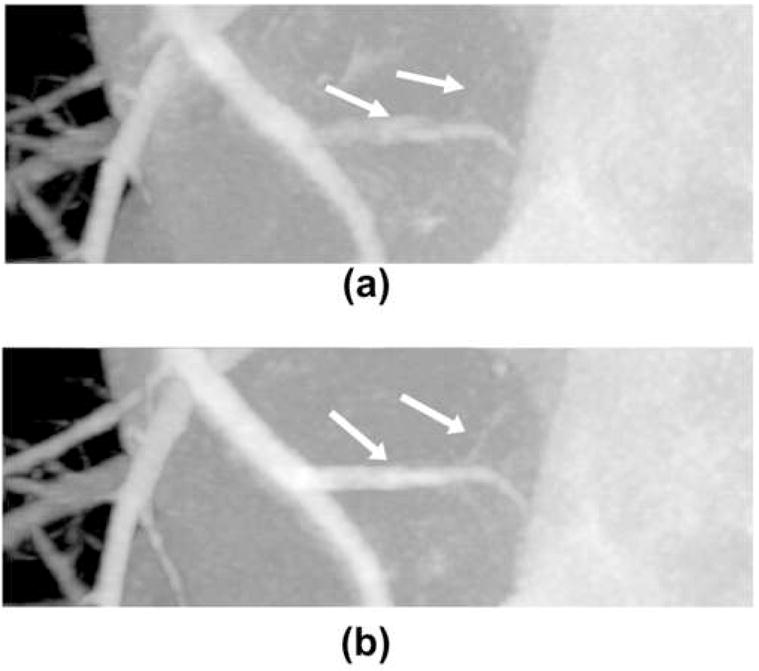

Figure 9.

MIPs through the ROI in the x (AP) direction. (a) Without temporal targeted reconstruction. (b) With temporal targeted reconstruction. Display window [−590 HU 780 HU].

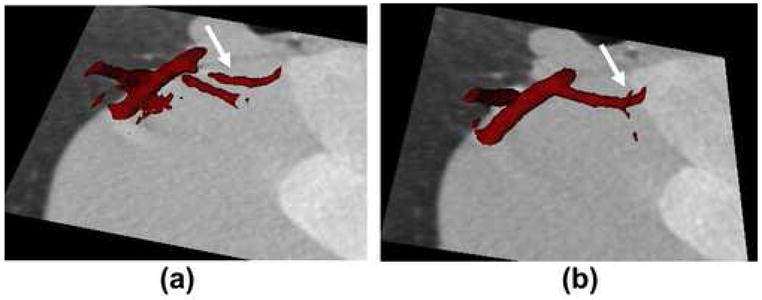

Figure 10.

A comparison of the isosurface rendering results: (a) without temporal targeting, and (b) with temporal targeting.

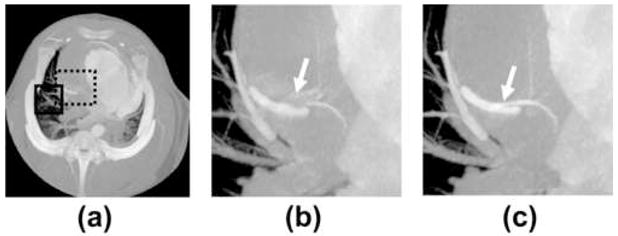

Pulmonary Region of Interest

Images of vessels and airways in close proximity to the heart, particularly in the lingula and right middle lobe suffer from artifacts caused by cardiac motion. It is therefore logical that ECG gated reconstruction of the lung offers significant motion suppression (10, 26). Likewise, STTaR offers the possibility for improved temporal resolution and thus a reduction in blurring artifacts. ECG gated reconstructions were performed both with and without temporal targeting in an ROI adjacent to the right atrium, within the right middle lobe. Comparison MIPs in the z direction through this ROI (Figure 11) demonstrate a reduction in the vessel blurring as denoted by the arrows in Figure 11(a) and Figure 11(b). Additionally, one may generate minimum intensity projection images (Figure 12), which highlight the airways. A comparison between the minimum intensity projection images with and without STTaR shows that here further branching is visualized when utilizing STTaR.

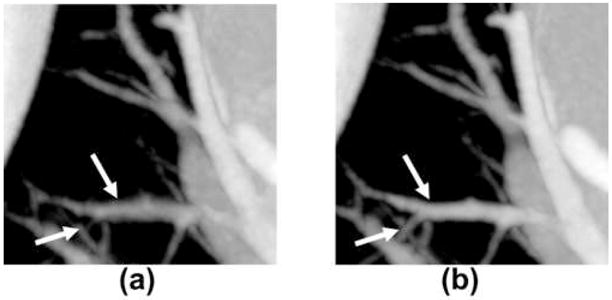

Figure 11.

Comparison MIPs through the pulmonary ROI: (a) without temporal targeting, and (b) with temporal targeting. Diplay window [−660 HU 650 HU].

Figure 12.

Minimum intensity projections through: the entire field of view [−50 HU 650 HU], the pulmonary ROI without temporal targeting [−920 HU −400 HU] and the pulmonary ROI with temporal targeting [−920 HU −400 HU].

Discussion

The concept of temporally targeted cardiac reconstruction has been demonstrated with a well-controlled vessel motion phantom and in vivo with a porcine model. This method uses recently developed mathematically exact reconstruction techniques to reduce the required angular range of projection data for an image region-of-interest. The STTaR (Spatially and Temporally Targeted Reconstruction) technique demonstrated a reduction in motion-induced streak artifacts in the phantom study, as well as improved fidelity in the shape of the reconstructed ‘vessel’. An ECG gated contrast enhanced exam was performed in a porcine model to highlight the clinical potential of STTaR in coronary and pulmonary angiography. A reduction of motion artifacts and blurring was achieved with STTaR in the right coronary and pulmonary artery anatomy that was the focus of this study, for both slice-based and MIP-based visualization formats.

The right coronary artery (RCA) is generally the most challenging coronary artery to image. Multiple imaging modalities, including electron beam CT (EBCT) (14), multislice CT (15) and bi-plane angiography (13) have all demonstrated that the RCA displays both the highest speed among the coronaries as well as the greatest range of motion. Therefore, significant motion artifacts are expected when imaging the RCA (Figure 2). In this study a clear motion artifact was found adjacent to the sinoatrial nodal artery (SAN), which bifurcates from the RCA. The motion artifact appeared as a duplicate artifactual vessel within the image presented in Figure 2. Since this artery contained significant motion artifact in the standard short scan reconstruction, it was selected to demonstrate the improvement that STTaR may provide (Figures 7–11)

The reconstruction algorithm employed here was of the filtered backprojection type in the native geometry (7, 8, 18–20). A major feature of this type of algorithm is the possibility to perform a super-short scan, in which the acquired projection data span less than 180 degrees plus fan angle. Another recently developed class of analytic, exact algorithms performs a differentiation operation on the projections, followed by backprojection, and finally filtering in image space (27–30). The temporal benefits of one of these algorithms was thoroughly studied with computer simulated projections through motion phantoms (31). The work presented here differs from earlier literature (31) in that filtered backprojection reconstruction was used and in vivo data have been utilized to illustrate the potential benefit of STTaR. However it should be noted that the two classes of reconstruction algorithms enable similar gains in motion artifact reduction, and either may be employed in the STTaR method.

Data acquisition in this study was performed in an axial mode, whereas current cardiac protocols are typically helically based. For small cone-angles fan beam formulas may be applied directly to interpolated helical data (32–35). For the moderate cone-angles of current state-of-the-art 64-slice scanners, FDK-type approximations that utilize heuristic filtering and exact 3D backprojection may be employed (17, 36–38). We note that for a helical acquisition the z extent of the targeted ROI (for a given cardiac phase) may be limited, depending on the synchronization between the heart rate and the gantry rotation rate. The relatively large detector z coverage of current cardiac CT scanners has enabled low dose prospective step-and-shoot acquisition for cardiac imaging (39). This mode has recently been implemented commercially (LightSpeed VCT XT, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, Wisconsin; and Brilliance CT, Philips Medical Systems, Netherlands). In this mode temporal targeting can be applied to regions of interest having large z extent. Therefore the full benefits of the STTaR technique will likely be realized with step-and-shoot acquisitions. The STTaR technique will also be well-suited to systems employing axial acquisition and even larger detectors, which enable whole heart coverage in a single gantry rotation and may eliminate the need for helical cardiac scanning (40).

As noted in the description of the reconstruction algorithm and associated references, the range of projection data required for STTaR is dependent upon the size and position of the region of interest. Therefore, each exam may require a different range of projection data for the STTaR technique based on the selected ROI’s size and position.

The two limiting cases are when the full field-of-view (FOV) is selected for reconstruction and when a small peripheral ROI is reconstructed. In the case of full FOV imaging STTaR is equivalent to standard short scan reconstruction and offers no improvement or loss in the temporal resolution. In the case of a small peripheral ROI reconstruction the temporal window may be cut to roughly two-thirds of that required for a short scan. Realistic cardiac imaging scenarios will lie between these two limits. For example in this paper a 20% reduction in the temporal window was demonstrated in vivo. It must be emphasized that STTaR is not proposed to replace the full FOV short scan reconstruction, but rather provides an additional option with improved temporal resolution that can be applied whenever a region-of-interest reconstruction is of clinical interest. Furthermore, in such a supplemental reconstruction one has the freedom to select how much of the projection data contributes to the STTaR image, ranging from the minimum dictated by data sufficiency conditions (7–9) up to the standard 180 degrees plus fan angle used in a short scan reconstruction. Increasing the amount of projection data contributing to the image comes at the cost of temporal resolution, however this may be desirable under certain circumstances owing to the improved quantum statistics.

There were several limitations of this feasibility study. First, this study was conducted only to demonstrate improvements in image quality in a controlled motion phantom and to highlight the potential of STTaR for in vivo ECG-gated cardiac scanning. In order to conclusively demonstrate clinical utility, a quantitative study with a statistically significant number of exams must be conducted. A second limitation is that the heart rate of the pig was higher than the average rate for single source CT coronary angiography (2, 4). However, one of the aims of our work is to increase the range of heart rates where diagnostic information may be gained, potentially reducing the reliance on beta blockers for clinical coronary CTA. Third, images produced with STTaR techniques will have a higher quantum noise variance than the full FOV short scan images as fewer photons are used in the reduced scan angle reconstruction. In the best temporal case (small peripheral ROI) of a ~1/3 reduction in temporal window the standard deviation of the quantum noise would theoretically increase by 22%; however in the more representative case of the 20% reduction in the temporal window achieved here the increase in quantum noise is considerably smaller as demonstrated through experimental measurements.

Considering that motion artifacts are often the dominant reason for non-diagnostic image quality (2, 4), the improved temporal resolution afforded by the STTaR technique may be clinically useful even with a modest increase in quantum noise. As discussed above, during reconstruction the operator has the option of choosing the tradeoff between temporal resolution and quantum noise that best suits the situation, without need to repeat the scan or alter the exam protocol in any way. Thus, these techniques will result in no additional patient dose, and we would only suggest their application when the improved temporal resolution justifies the increased quantum noise.

Finally, a complete comparison to state-of-the-art multi-segment reconstructions has not been included here. In the clinical implementation, we envision the STTaR technique being utilized with low dose prospectively triggered step-and-shoot acquisitions. In these prospective axial acquisitions projection data may not available for multi-segment (multi-beat) reconstructions. Therefore, the STTaR technique will be well suited for acquisitions where multi-segment reconstructions are not feasible. While a clinical comparison to multi-segment techniques would be of interest it is beyond the scope of our current work.

In conclusion, temporally targeted reconstruction techniques demonstrate the potential to reduce motion artifacts in ECG gated coronary CT. As demonstrated here through both a controlled motion phantom acquisition and an in vivo acquisition on a state-of-the-art clinical volumetric CT scanner a modest improvement temporal resolution (~20%) can offer improvements in image quality. These improvements were seen through both qualitative observation of the reduction in streak artifacts and a quantitative measure of the shape of the reconstructed vessel.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the assistance of Dr. Michael Van Lysel, Larry Whitesell and Donna Juno for their assistance with the porcine model. Pre-processing of the acquired projection data was performed at GE Healthcare and we thank Dr. Jiang Hsieh for his assistance in this process. Our computer network administrator is Dr. Orhan Unal and we thank him for his support. We acknowledge the use of Tony Reina’s publicly available function to calculate ellipse eccentricity from MatlabCentral (Mathworks). This work was partially supported by NIH grants 1R01 EB 005712, 5T32CA009206, a grant from GE Healthcare, and the Herman I. Shapiro Distinguished Graduate Fellowship (S.L.).

Grants: NIH grants R01EB005712, 5T32CA009206

Herman I. Shapiro Distinguished Graduate Fellowship (SL)

A research grant from GE Healthcare

Appendix

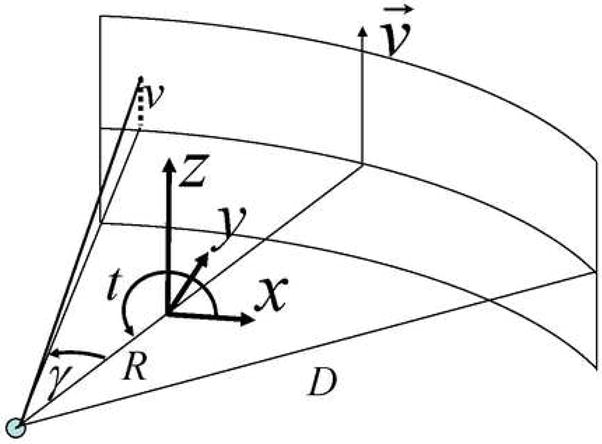

As described in the text the reconstruction algorithm used here has been previously published. However, for clarity in presentation this appendix has been included to describe the steps carried out in reconstructing an image volume from the measured projection data. The axial scan used here corresponds to a source trajectory of a single circle which is parameterized as follows, (xs, ys, zs) = R(cost,sin t,0), t∈ [ti,t f ], where R is the radius, t is the view angle parameter, and the beginning and ending points used in the reconstruction are ti and t f respectively. Our parameterization of the third generation multi-detector CT geometry is shown in Figure 13. The pre-processed data which is the input for the reconstruction algorithm will be referred to as gm (γ,v,t), where these parameters are defined in Figure 13. The reconstruction is conducted according to the following steps.

Figure 13.

The parameterization of the acquisition geometry for the equi-angular detector used in this study. Each collected data point is parameterized by three parameters: the view angle parameter (t), the fan angle (γ) and the height in the detector plane (v). The radius of the trajectory is given by R and the distance from the source to detector is given by D (distance measured along the incident x-ray direction for v= 0).

I) Pre-weight

The pre-processed data are weighted using the heuristic ‘cosine’ weight (17)

II) Differentiate

The differentiation operation was performed numerically using a three point method and the differentiated data are computed as

III) Filter

For each row in the detector plane after the data has been differentiated apply a modified Hilbert filter.

IV) Weight Filtered Data

The weighting function suggested by Noo (7) was used here to provide a smooth weighting that properly weights conjugate rays. As suggested by Noo we have assigned the free parameter to be d = 10°. In our notation this weighting is expressed as:

V) Backproject

A voxel based backprojection is performed via bilinear interpolation on the detector plane of the filtered and weighted data. In order to reconstruct the value for a given point in image space (x, y, z) the following relations are employed

For these retrospective reconstructions the parameters ti and tf are selected such that the coronary/pulmonary ROI lies within the convex hull formed by connecting the two ending points of the arc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hoffmann MH, Shi H, Schmitz BL, et al. Noninvasive coronary angiography with multislice computed tomography. Jama. 2005;293:2471–2478. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Budoff MJ, Achenbach S, Blumenthal RS, et al. Assessment of coronary artery disease by cardiac computed tomography: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Committee on Cardiovascular Imaging and Intervention, Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention, and Committee on Cardiac Imaging, Council on Clinical Cardiology. Circulation. 2006;114:1761–1791. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.178458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leschka S, Alkadhi H, Plass A, et al. Accuracy of MSCT coronary angiography with 64-slice technology: first experience. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1482–1487. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leschka S, Wildermuth S, Boehm T, et al. Noninvasive coronary angiography with 64-section CT: effect of average heart rate and heart rate variability on image quality. Radiology. 2006;241:378–385. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2412051384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flohr TG, McCollough CH, Bruder H, et al. First performance evaluation of a dual-source CT (DSCT) system. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:256–268. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-2919-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kak AC, Slaney M. Principles of Computerized Tomographic Imaging. Bellingham, WA: IEEE; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noo F, Defrise M, Clackdoyle R, Kudo H. Image reconstruction from fan-beam projections on less than a short scan. Phys Med Biol. 2002;47:2525–2546. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/47/14/311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen G-H. A new framework of image reconstruction from fan beam projections. Med Phys. 2003;30:1151–1161. doi: 10.1118/1.1577252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pan X, Zou Y, Xia D. Image reconstruction in peripheral and central regions-of-interest and data redundancy. Med Phys. 2005;32:673–684. doi: 10.1118/1.1844171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savino G, Herzog C, Costello P, Schoepf UJ. 64 slice cardiovascular CT in the Emergency Department: concepts and first experiences. Radio med. 2006;111:481–496. doi: 10.1007/s11547-006-0044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayer F, Nguyen SA, Schoepf UJ, Ravenel JG. Extra-cardiac Findings at Cardiac CT. RSNA Annual Meeting; 2006. p. 207. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kachelrieβ M, Kalender WA. Electrocardiogram-correlated image reconstruction from subsection spiral computed tomography scans of the heart. Med Phys. 1998;25:2417–2431. doi: 10.1118/1.598453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shechter G, Resar JR, McVeigh ER. Rest period duration of the coronary arteries: implications for magnetic resonance coronary angiography. Med Phys. 2005;32:255–262. doi: 10.1118/1.1836291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mao S, Lu B, Oudiz RJ, Bakhsheshi H, Liu S, Budoff MJ. Coronary Artery Motion in Electron Beam Tomography. JCAT. 2000;24(2):253–258. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200003000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vembar M, Garcia MJ, Heuscher DJ, et al. A dynamic approach to identifying desired physiological phases for cardiac imaging using multislice spiral CT. Med Phys. 2003;30:1683–1693. doi: 10.1118/1.1582812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker DL. Optimal short-scan convolution reconstruction for fan beam CT. Med Phys. 1982;9:254–257. doi: 10.1118/1.595078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feldkamp LA, Davis LC, Kress JW. Practical cone-beam algorithm. J Opt Soc Am A. 1984;1:612–619. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kudo H, Noo F, Defrise M, Clackdoyle R. New super-short-scan algorithm for fan-beam and cone-beam reconstruction. IEEE NS-MIC. 2002;M5-3:902–906. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen GH, Tokalkanahalli R, Zhuang T, Nett BE, Hsieh J. Development and evaluation of an exact fan-beam reconstruction algorithm using an equal weighting scheme via locally compensated filtered backprojection (LCFBP) Med Phys. 2006;33:475–481. doi: 10.1118/1.2165416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu H, Wang G. Feldkamp-type VOI reconstruction from super-short-scan cone-beam data. Med Phys. 2004;31:1357–1362. doi: 10.1118/1.1739298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kudo H, Noo F, Defrise M, Clackdoyle R. New super-short-scan algorithm for fan-beam and cone-beam reconstruction. IEEE NSS-MIC. 2002;M5-3:902–906. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nett BE, Zhuang T-L, Leng S, Chen G-H. Arc based cone-beam reconstruction algorithm using an equal weighting scheme J. X-Ray Sci Tech. 2007;15:19–48. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chesler DA, Riederer SJ, Pelc NJ. Noise due to photon counting statistics in computed X-ray tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1977;1:64–74. doi: 10.1097/00004728-197701000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brooks RA, Di Chiro G. Statistical limitations in x-ray reconstructive tomography. Med Phys. 1976;3:237–240. doi: 10.1118/1.594240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung CS, Karamanoglu M, Kovacs SJ. Duration of diastole and its phases as a function of heart rate during supine bicycle exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H2003–2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00404.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hofmann LK, Zou KH, Costello P, Schoepf UJ. Electrocardiographically gated 16-section CT of the thorax: cardiac motion suppression. Radiology. 2004;233:927–933. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2333030826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zou Y, Pan X. Exact image reconstruction on PI-lines from minimum data in helical cone-beam CT. Phys Med Biol. 2004;49:941–959. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/6/006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhuang T, Leng S, Nett BE, Chen G-H. Fan-beam and cone-beam image reconstruction via filtering the backprojection image of differentiated projection data. Phys Med Biol. 2004;49:5489–5503. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/24/007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ye Y, Zhao S, Yu H, Wang G. A general exact reconstruction for cone-beam CT via backprojection-filtration. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2005;24:1190–1198. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2005.853626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pack JD, Noo F, Clackdoyle R. Cone-beam reconstruction using the backprojection of locally filtered projections. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2005;24:70–85. doi: 10.1109/tmi.2004.837794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.King M, Pan X, Yu L, Giger M. Region-of-interest reconstruction of motion-contaminated data using a weighted backprojection filtration algorithm. Med Phys. 2006;33:1222–1238. doi: 10.1118/1.2184439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu H. Multi-slice helical CT: scan and reconstruction. Med Phys. 1999;26:5–18. doi: 10.1118/1.598470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noo F, Defrise M, Clackdoyle R. Single-slice rebinning method for helical cone-beam CT. Phys Med Biol. 1999;44:561–570. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/44/2/019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kachelriess M, Schaller S, Kalender WA. Advanced single-slice rebinning in cone-beam spiral CT. Med Phys. 2000;27:754–772. doi: 10.1118/1.598938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taguchi K, Aradate H. Algorithm for image reconstruction in multi-slice helical CT. Med Phys. 1998;25:550–561. doi: 10.1118/1.598230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang G, Lin TH, Cheng PC, Shinozaki DM. A general cone-beam reconstruction algorithm. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1993;12:486–496. doi: 10.1109/42.241876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hein I, Taguchi K, Silver MD, Kazama M, Mori I. Feldkamp-based cone-beam reconstruction for gantry-tilted helical multislice CT. Med Phys. 2003;30:3233–3242. doi: 10.1118/1.1625443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang X, Hsieh J. A filtered backprojection algorithm for cone beam reconstruction using rotational filtering under helical source trajectory. Med Phys. 2004;31:2949–2960. doi: 10.1118/1.1803672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hsieh J, Londt J, Vass M, Li J, Tang X, Okerlund D. Step-and-shoot data acquisition and reconstruction for cardiac x-ray computed tomography. Med Phys. 2006;33:4236–4248. doi: 10.1118/1.2361078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kido T, Kurata A, Higashino H, et al. Cardiac imaging using 256-detector row four-dimensional CT: preliminary clinical report. Radiat Med. 2007;25:38–44. doi: 10.1007/s11604-006-0097-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]