Abstract

The skin epidermis and its appendages provide a protective barrier that guards against loss of fluids, physical trauma, and invasion by harmful microbes. To perform these functions while confronting the harsh environs of the outside world, our body surface undergoes constant rejuvenation through homeostasis. In addition, it must be primed to repair wounds in response to injury. The adult skin maintains epidermal homeostasis, hair regeneration, and wound repair through the use of its stem cells. What are the properties of skin stem cells, when do they become established during embryogenesis, and how are they able to build tissues with such remarkably distinct architectures? How do stem cells maintain tissue homeostasis and repair wounds and how do they regulate the delicate balance between proliferation and differentiation? What is the relationship between skin cancer and mutations that perturbs the regulation of stem cells? In the past 5 years, the field of skin stem cells has bloomed as we and others have been able to purify and dissect the molecular properties of these tiny reservoirs of goliath potential. We report here progress on these fronts, with emphasis on our laboratory’s contributions to the fascinating world of skin stem cells.

The mammalian skin epidermis has long been an archetype for exploring homeostasis and injury repair in a stratified epithelium. It maintains a single inner (basal) layer of proliferative cells that adhere to an underlying basement membrane (BM), rich in extracellular matrix (ECM) and growth factors, which separates the epidermis from the underlying dermis (Fig. 1A). Cells in the basal layer are responsible for generating the layers of nondividing cells that undergo a program of terminal differentiation as they move outward and are continually shed from the skin surface. To maintain this self-perpetuating barrier that keeps harmful microbes out and essential body fluids in, the basal epidermal layer must perfectly balance proliferation and differentiation. How it does this is still under investigation. Although the process of epidermal homeostasis might seem to be a simple one, the microenvironment of the basal stem cell niche is multi-faceted and can change both suddenly due to injury and also progressively with cumulative damage from harmful UV rays and other external assaults that can eventually lead to cancer. As our molecular understanding of epidermal homeostasis expands, the layers of complexity are beginning to unravel.

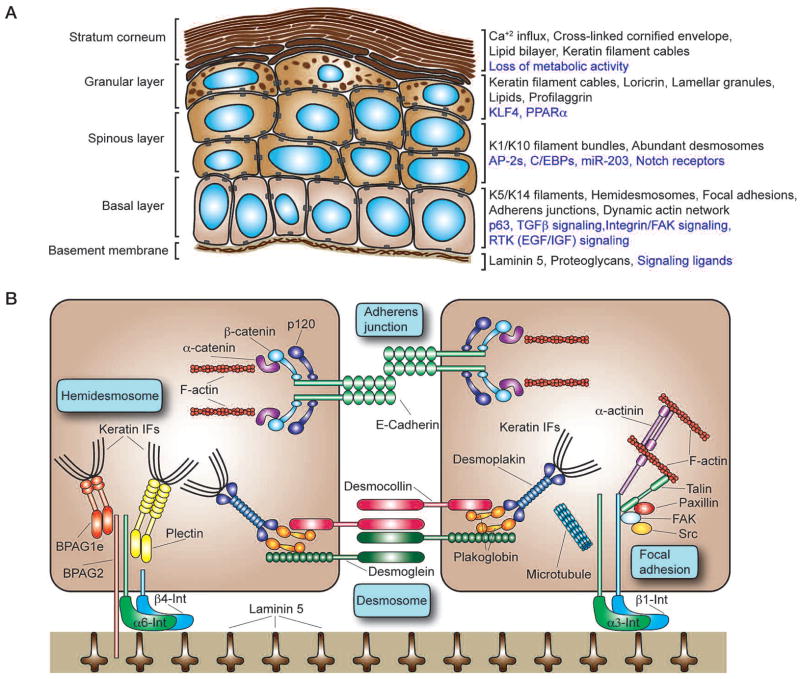

Figure 1.

The cellular architecture of the epidermis and major components of the epidermal cytoskeleton. (A) Program of epidermal differentiation illustrating the BM at the base, the proliferative basal layer, and the three differentiation stages: spinous layer, granular layer, and outermost stratum corneum. Shown at the right are key molecular markers described in the text. (Black text) Structural and cytoskeletal components present in each layer; (purple text) regulatory mechanisms and signaling activity necessary for proper function of each layer. (B) Key components of the cytoskeleton in basal layer keratinocytes. Keratin IFs connect to the BM via hemidesmosomes, whose core components include homodimers of the plakin proteins plectin and BPAG1e, the transmembrane collagen BPAG2, and a heterodimer composed of α6 and β4 integrin. Intercellularly, the keratin network is also linked at adjacent cells by desmosomes that are composed of the desmosomal cadherins desmocollin and desmoglein, the linker protein plakoglobin, and a homodimer of the plakin protein desmoplakin. Analogously, the actin cytoskeleton attaches to the underlying BM through focal adhesions that are composed of an α3β1 integrin heterodimer core linked to actin filaments (F-actin) by talin and α-actinin. Paxillin, FAK, and Src are also associated with focal adhesions and help to orchestrate signaling events regulating cell adhesion and motility. Microtubules can also contact focal adhesions, helping to regulate their turnover. Between adjacent cells, the actin cytoskeleton is linked through adherens junctions that associate through homotypic interactions between E-cadherin molecules. Heterodimers composed of β-catenin and α-catenin regulate the link between E-cadherin and the actin cytoskeleton, whereas p120-catenin stabilizes E-cadherin interactions by binding to E-cadherin’s cytoplasmic domain.

THE EPIDERMIS: ARCHITECTURE

Basal epidermal cells must remain proliferative and also protect themselves from the physical traumas of our environment. To do so, they possess an abundant infrastructure of 10-nm intermediate filaments (IFs) composed of keratins 5 and 14 (K5 and K14). At the base of each cell, keratin IFs fasten through plakin proteins (BPAG1e and plectin) to hemidesmosomes that provide mechanical strength to the cytoplasm below the nucleus of the columnar basal cells (Fig. 1B). Hemidesmosomes also anchor the cells to their underlying BM through a transmembrane collagen (BPAG2) and an α6β4 integrin core that adheres to laminin 5 in the BM. At intercellular borders, keratin filaments also bind to desmoplakin, a plakin component of desmosomes, thereby completing the fortifying infrastructure of the IF cytoskeleton. Desmosomes also use their robust transmembrane core of desmosomal cadherins (desmogleins and desmocollins) to reinforce cell–cell adhesion. The physiological significance of this structural IF network is underscored by mutations in genes that perturb keratin IFs, hemidesmosomes, or desmosomes, which typically lead to cell degeneration and subsequent skin blistering (Fuchs and Cleveland 1998).

To maintain their proliferative capacity and their ability to migrate in response to injury, basal cells must also possess elaborate and dynamic actin and microtubule cytoskeletons. The actin cytoskeleton indirectly links to the underlying BM beneath the epidermis through α3β1-rich focal adhesions (FAs) that also use laminin 5 as their ligand and to neighboring cells through E-cadherin-rich adherens junctions (AJs) (Fig. 1B). Intracellularly, the α3β1 integrin core associates with a complex array of actin-binding proteins and regulatory kinases that in turn act on effectors of Rho-GTPases to orchestrate actin dynamics, focal adhesion, and migration (Watt 2002; Lorenz et al. 2007; Schober et al. 2007). Transmembrane E-cadherins form homotypic intercellular and intracellular interactions that are stabilized through binding of their cytoplasmic domain to p120-catenin. At a second site, the cytoplasmic domain of E-cadherin binds to β-catenin that in turn binds α-catenin, a mediator of actin dynamics (Perez-Moreno and Fuchs 2006). AJs act in conjunction with FAs to coordinate actin dynamics across the epithelial tissue and also organize the underlying cortical belt of actin fibers that reinforce the plasma membrane of each epidermal cell. Through a number of still unfolding mechanisms, microtubules associate with actin, FAs, and AJs to polarize the cytoskeleton, asymmetrically distribute proteins and organelles within the cell, and orchestrate adhesion and directed movements within the cell. Below, we highlight some of the ways in which these dynamics are important to epidermal stem cells and tissue homeostasis.

Intercellular and cell-substratum junctions must be robust enough to provide mechanical strength, but they must also be dynamic in order to allow for a flux of epidermal cells upward through the tissue during normal homeostasis and to orchestrate repair after wounding. A frequent paradigm not only in the regulation of normal homeostasis and migration but also in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) process that can drive tumorigenesis is the inverse regulation of cadherin-dependent intercellular junctions and integrin-dependent cell motility (Frame et al. 2002). Although many details of the underlying regulatory mechanism remain elusive, the Src tyrosine kinase and small GTPases are central players in the process (Frame et al. 2002). Src is itself a downstream substrate of focal adhesion kinase (FAK), which is activated by α3β1 integrin, and Src activation can result in activation of p190RhoGAP. This leads to reduced Rho-GTPase and ROCK activities as well as actin stress fibers, features that promote FA turnover and enhance cell migration in keratinocytes in vitro and that are required for normal wound repair in vivo (Lorenz et al. 2007; Schober et al. 2007). Activated Src is also known to phosphorylate E-cadherin and p120-catenin, and these marks appear to weaken intercellular junctions by promoting their endocytosis. It has been proposed that internalized E-cadherin results in the activation of an additional GTPase, Rap1, that in turn controls the polarized redistribution of integrins and/or integrin regulators to new adhesion sites, thereby enhancing integrin-mediated cell–matrix adhesion (Balzac et al. 2005).

Increasing evidence underscores the coordinate regulation not only of FA and AJ dynamics but also of actin and microtubule dynamics in epithelial cells. Microtubules contribute to adhesion dynamics by targeting and promoting FA turnover (Kaverina et al. 1999) and enhancing intercellular junction formation between keratinocytes (Kee and Steinert 2001). Although the underlying mechanisms remain to be elucidated, loss-of-function studies suggest a role for both α3β1 integrins and α-catenin in orienting the mitotic spindle properly in the epidermis (Lechler and Fuchs 2005), whereas p120-catenin appears to be involved in cadherin-independent stabilization of microtubules (Ichii and Takeichi 2007). Whether at cell-substratum junctions or cell–cell junctions, harmonizing actin and microtubule networks is critical for establishing cellular polarity, without which the epidermal basal layer cannot properly separate proliferative and differentiating compartments to generate correct tissue architecture.

Basal epidermal cells must integrate signals from multiple pathways in order to set their rate of proliferation. In addition to cell migration and adhesion, integrin signaling has a major role in basal layer growth control. In part, this is likely mediated through the ability of integrins to activate the Src family tyrosine kinases, which are potent activators of the Ras–mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling cascade (Lorenz et al. 2007; Schober et al. 2007). Additionally, transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) for epidermal and insulin growth factors (EGFs and IGFs) have critical roles in stimulating basal cell proliferation (Barrandon and Green 1987a; Zenz and Wagner 2006; Scholl et al. 2007).

Whereas integrin and RTK signaling function as accelerators for epidermal proliferation, signaling through the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) pathway acts as the brake (Shi and Massagué 2003). Upon TGF-β ligand engagement, the TGF-β transmembrane receptor, which possesses serine/threonine kinase activity, becomes activated and subsequently phosphorylates Smad2 or Smad3 transcription factors. These phosphorylated Smads join larger transcription factor complexes to regulate downstream target genes, some of which encode cell cycle inhibitors. Intriguingly, when the TGF-β receptor II subunit is missing in the skin epidermis, the activity of αβ1 integrins and FAK are elevated, leading to a enhanced wound repair and cell migration (Guasch et al. 2007).

When coupled with prior studies identifying direct associations between RTKs and integrins (Lee and Juliano 2004), these data suggest a regulatory network where the activity of one type of transmembrane receptor will affect the activity of others. An additional twist comes from the fact that α-, β-, and p120 catenins each influence actin dynamics and/or proliferation in ways that appear to extend beyond their roles in cadherin-mediated intercellular adhesion. Counterbalancing these regulatory circuits are additional underlying mechanisms that can act to offset excessive proliferation with enhanced differentiation and/or apoptosis, thereby restoring normalcy to tissue morphology and minimizing the phenotypic consequences of genetic mutations.

As epidermal cells exit the basal layer and cease to proliferate, they progress upward through three distinct differentiation stages: spinous layer, granular layer, and stratum corneum (Fig. 1A). The major structural change at the basal-to-spinous-layer transition is the switch from K5 and K14 IFs in the basal layer to K1 and K10 suprabasally. Discovered three decades ago, this switch is transcriptionally controlled and remains among the most faithful of indicators that a cell has withdrawn from the cell cycle and is committed to terminally differentiate (Fuchs and Green 1980). Additional structural changes occurring at this time include switches in expression of desmosomal cadherins and the initial expression of a few components of the “cornified envelope” that are deposited beneath the plasma membrane for late-stage differentiation events.

To orchestrate these changes in structure and function, the basal/spinous transition is accompanied by dramatic changes in the expression of transcription factors. One transcription factor that is likely to have a key role in regulating the self-renewal and long-term proliferative capacity of the basal layer is p63, a member of the p53 family of proto-oncogenes. The ΔN isoform of p63 is preferentially expressed in basal epidermal cells (Laurikkala et al. 2006), and although the exact functions of p63 are still under investigation, it appears that p63 is necessary for basal cells to maintain proliferative potential. In its absence, the epidermis fails to stratify and differentiate properly during embryonic development (Mills et al. 1999; Yang et al. 1999; Senoo et al. 2007). In contrast to p63, which is down-regulated in the basal-to-spinous-layer switch, elevated levels of several AP-2 and C/EBP family members are associated with the terminal differentiation program (Maytin and Habener 1998; Wang et al. 2006). Loss-of-function studies also unveil an essential role for Notch signaling in governing the basal-to-spinous-layer fate switch, and in this regard, it is notable that Notch ligands are expressed both basally and suprabasally, whereas Notch receptors are suprabasal (Powell et al. 1998; Rangarajan et al. 2001; Pan et al. 2004; Blanpain et al. 2006; Nguyen et al. 2006a; Lee et al. 2007; Moriyama et al. 2008) Exactly how Notch, AP-2s, and C/EBPs cooperate to regulate the basal-to-spinous switch remains to be elucidated.

Adding another level of complexity to the process is the microRNA miR-203, which is expressed in suprabasal layers of the epidermis and was recently shown to directly target ΔNp63 mRNA for translational repression (Yi et al. 2008). Another miR-203 target is Zpf280, a nuclear protein expressed not only in epidermal stem cells, but also in embryonic stem cells (Yi et al. 2008). As the field continues to unfold, it will be interesting to see the extent to which miR-203 and other microRNAs function in stem cell fate commitment. If miR-203 targets are primarily basal genes, miR-203 might be viewed as a fine-tuner of commitment, accelerating repression of basal markers in suprabasal cells. A tantalizing possibility for future investigation is the notion that the gene encoding miR-203 could itself be a target for Notch signaling.

Although AP-2 and C/EBP families appear to function in conjunction with Notch signaling to regulate the basal-to-spinous switch early in suprabasal differentiation, the transcription factors KLF4 and PPARα seem to regulate genes expressed later in the process (Segre et al. 1999; Di-Poi et al. 2004). As cells enter the granular layer, the primary cornified envelope protein loricrin is expressed, and lamellar granules packed full of lipids appear. Profilaggrin is also expressed at this time, and soon afterward, it is processed to generate filaggrin, a protein that bundles keratin filaments into indestructible cables. As granular cells transit to the stratum corneum, all metabolic activity ceases, and an influx of calcium results in activation of transglutaminases that initiate γ-glutamyl-ε-lysine cross-links to produce the cornified envelope characteristic of this layer. Lamellar granules are extruded onto this scaffold, where they form a lipid bilayer that temporarily seals the dead, protective cells at the body surface (de Guzman Strong et al. 2006; Elias 2007).

The process of terminal differentiation is in a continual flux so that dead surface cells are continually sloughed off and replaced by inner cells differentiating and moving outward. In human epidermis, the self-renewing capacity of epidermal stem cells is enormous, and within 4 weeks, a basal cell has terminally differentiated and exited at the skin surface. In mice, the postnatal trunk epidermis becomes thinner and proliferation slows substantially as the hair coat develops and becomes the primary line of physical protection.

THE EPIDERMIS: HOMEOSTASIS

Researchers have known for decades that stem cells exist within the basal layer of adult epidermis, but it remains unknown whether all cells within the basal layer are stem cells. Early work on epidermal homeostasis defined the epidermal proliferative unit (EPU) as an architecturally discernible structure composed of a bed of approximately ten basal cells overlaid by a stack of increasingly larger and flatter cells (Potten 1974). EPU proliferation studies and genetic marking of epidermal clonal units have led to the hypothesis that there is one self-renewing, slower-cycling stem cell in the center of each EPU and that the other basal cells are so-called “transit-amplifying” (TA) cells, i.e., committed cells that divide several times and then exit the basal layer and terminally differentiate (Potten 1974; Mackenzie 1997). In support of this notion are in vitro studies that show that human epidermal cells with the highest level of surface β1 integrins give rise to the largest colonies (holoclones) that can be passaged long-term, whereas cells with lower levels of β1 integrins produce smaller meroclones that do not survive passaging (Barrandon and Green 1987b; Jones et al. 1995). Regional variations within the BM and microenvironment have been described to explain how distinct populations of integrin-rich stem cells and TA cells might arise within the basal layer if its residents divide symmetrically (Lavker and Sun 1982; Jensen et al. 1999). However, recent studies suggest that basal epidermal cells can divide asymmetrically, affording an alternative view of how one basal stem cell and one committed cell might arise (Lechler and Fuchs 2005; Clayton et al. 2007).

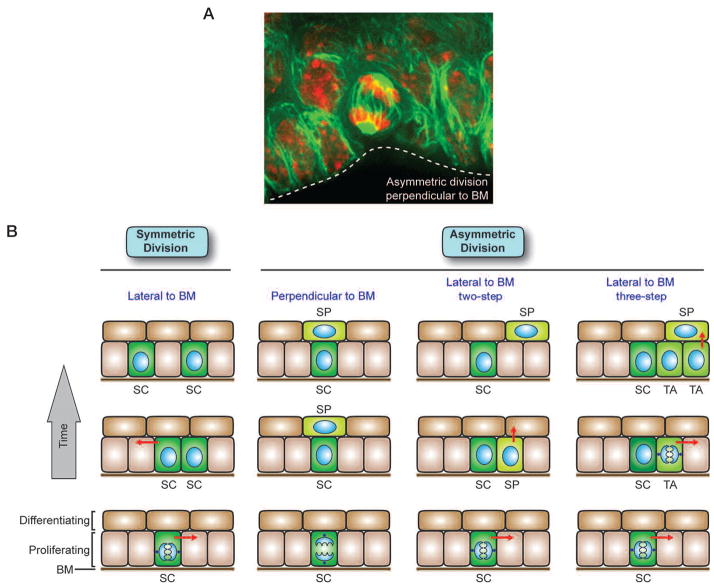

During embryogenesis in the mouse, some basal cells shift their spindle orientation from parallel to the BM to a more angled orientation, resulting in asymmetric divisions at the onset of stratification (Fig. 2A) (Lechler and Fuchs 2005). Approximately 70% of embryonic basal cell mitoses appear to be asymmetric relative to the underlying BM (Lechler and Fuchs 2005). As the animal matures, a marked reduction in basal cell divisions occurs that has posed technical difficulties in measuring division orientations in postnatal mice. However, asymmetric divisions have been detected in tongue, ear, and tail skin (Lechler and Fuchs 2005; Clayton et al. 2007). Intriguingly, mitotic basal cells about to undergo an asymmetric division display a cortical crescent of proteins that in lower eukaryotes are essential for proper spindle orientation (Lechler and Fuchs 2005). Additional experiments will be needed to ascertain whether these proteins function similarly in mammalian epidermis and whether asymmetric divisions are essential for epidermal homeostasis and/or wound repair.

Figure 2.

Roles for symmetric and asymmetric cell division in epidermal development and homeostasis. (A) Immunofluorescence image of a cell in the basal layer of an E15.5 embryonic tongue undergoing asymmetric division perpendicular to the BM (dotted white line). The microtubule network is marked by green fluorescent protein (GFP), and DNA is marked by red propidium iodide. (B) Self-renewing stem cells (SC) exist in the basal layer of the epidermis. Symmetrical divisions lateral to the BM produce two stem cells, a process that can serve to refill vacancies in the basal layer or increase the area of the epidermis during development. Asymmetric divisions can occur both laterally and perpendicular to the BM. In the two-step asymmetric division model, a stem cell divides asymmetrically to preferentially partition proliferation-associated factors into the stem cell daughter and provide differentiation-inducing components to the other daughter, fated to become a spinous (SP) cell. If the spindle orientation was perpendicular to the BM, the division could result in direct positioning of the SP daughter away from the BM, whereas lateral spindle orientation relative to the BM would then necessitate subsequent delamination of the committed SP daughter. In the three-step asymmetric division model, a transit-amplifyng (TA) intermediate arises, which has been postulated to divide three to four times before delaminating (arrows) and entering into a terminal differentiation program. Once the spinous cells have separated from the BM, they enter a program of terminal differentiation as they move outward and are eventually sloughed from the skin surface (see Fig. 1). Differentiating cells are continually replaced by a flux of inner cells committing to terminally differentiate and move outward. Immunofluorescence image courtesy of Terry Lechler (when in the Fuchs lab).

Although the extent to which asymmetric divisions control epidermal dynamics remains unknown, it is nevertheless intriguing to consider the potential consequences of such divisions. If the divisions occur at an angle relative to the plane of the basement membrane, the basal daughter cell would inherit the majority of the growth-promoting RTKs and integrins (Fig. 2B). Such divisions appear to be prevalent in embryogenesis, where they occur concomitant with stratification (Lechler and Fuchs 2005). In contrast, lineage-tracing studies suggest that many of the asymmetric divisions in adult tail skin result in both daughters retaining contact with their substratum, reflecting a division lateral to the basement membrane (Fig. 2B) (Clayton et al. 2007). In this model, it was noted that the Notch antagonist Numb is asymmetrically distributed in cells dividing lateral to the BM (Clayton et al. 2007). Differential partitioning of Notch signaling between the daughter cells of a lateral divison could result in one daughter being primed to undergo a basal-to-spinous-layer transition. Consistent with this notion, activated Notch signaling results in a decrease in integrin expression in basal keratinocytes (Blanpain et al. 2006).

These different models also have distinct implications for the numbers of epidermal stem cells and their organization in the basal layer. The EPU model predicts a small number of basal stem cells that reside individually in spatially organized niche microenvironments and are surrounded by TA cells (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the asymmetric division models predict a large, homogeneous population of basal progenitors that give rise to spinous cells through differential partitioning of proteins between daughters. The lateral asymmetric division model implies that asymmetric divisions are intrinsic to the epidermal stem cell, alleviating the need for a microenvironmental change to trigger commitment. The perpendicular asymmetric division model suggests that the BM itself may constitute the epidermal stem cell niche, naturally positioning committed progeny upward in a column. This perpendicular asymmetric division model is analogous to that of Drosophila germ cell development, where preservation of contact with the niche maintains stemness, and perpendicular asymmetric divisions drive the fate determination of committed daughter cells that depart from the niche (Fuller and Spradling 2007). Finally, lateral symmetric divisions would yield two stem cells and could provide a mechanism to replenish old or damaged basal stem cells or increase the area of the epidermis during development (Fig. 2B).

Irrespective of the role of the BM in governing basal cell division and the basal-to-suprabasal transition, its mechanophysical properties, along with those of the underlying dermis, are also likely to impact the behavior of basal cells (Dobereiner et al. 2005). The ECM polymers and growth factors of the BM also provide a complex repertoire of stimuli for basal cells. Among them is laminin 5, which, as outlined above, promotes anchorage and signaling/migration through its respective abilities to act as a ligand for both α6β4 and α3β1 integrins (Owens and Watt 2003; Raghavan et al. 2003; Manohar et al. 2004). The BM is also rich in ECM ligands for more minor epidermal integrins, proteoglycans, and both positive and negative growth factors (Fuchs 2007). Together, these features of the BM create a microenvironment that enables basal epidermal stem cells to maintain homeostasis under normal conditions and to respond appropriately to injury.

The epidermis has a huge proliferative capacity, but the balance of proliferation and differentiation is easily perturbed. This feature quite possibly represents a necessary molecular trade-off for a tissue that has to be adaptable enough to quickly repair wounds without depleting proliferative capacity over time. Disruptions of even a single component of the proliferation regulatory network can have serious consequences for the epidermis, as evidenced by the fact that mice harboring loss-of-function mutations in TGF-β receptor II or gain-of-function mutations in TGF-α or integrins display an increased susceptibility to squamous cell carcinomas (SQCCs), whereas those with loss-of-function mutations in FAK are more resistant to tumorigenesis than normal (McLean et al. 2004; Janes and Watt 2006; Guasch et al. 2007; Marinkovich 2007). As additional regulators of basal cell activity are discovered and links between known pathways become clearer, our understanding of the interplay between the BM and microenvironment and how they cooperate to regulate epidermal stem cell biology should continue to deepen.

THE HAIR FOLLICLE: MORPHOGENESIS

One of the most extraordinary features of the vertebrate epidermis is its ability to generate highly specialized elaborate appendages, including the feathers of birds, scales on a snake, hoofs of a horse, wool of a sheep, and hairs, nails, and sweat (eccrine) and oil (sebaceous) glands of our skin. Notably, although all of these appendages seem to be quite distinct, they all begin development in a similar way (Mikkola 2007), and knowledge of this process has been gained by studying the embryonic skin at a stage at which it exists as a single-layered epithelium.

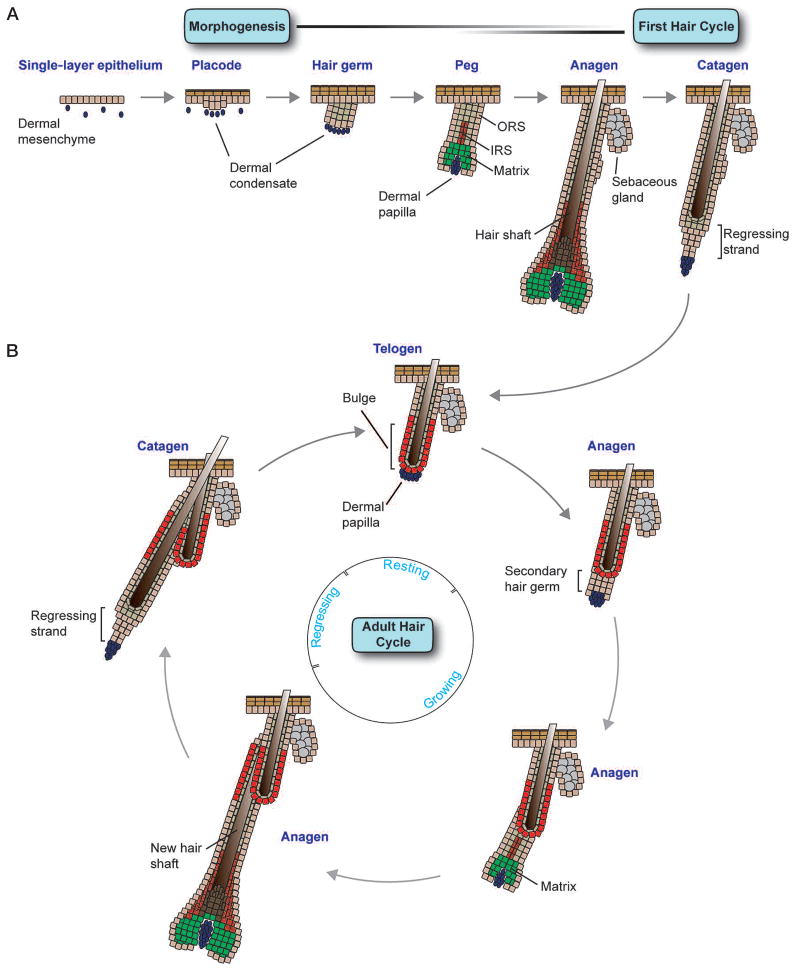

Before hair follicle morphogenesis, a uniform layer of epithelial cells overlies a disperse population of dermal cells. At about E14.5 of mouse development, mesenchymal-epithelial interactions result in the formation of the first wave of hair placodes that appear as small epidermal invaginations into the dermis (Fig. 3A). Once specified, signals from the epithelium cause dermal cells to aggregate and form a dermal condensate under each placode. This specification process occurs in four overlapping waves, with rare primary guard hairs being specified at E14.5 and the remainder of follicles being specified from E15.5 to P0. Once placodes have formed, they become highly proliferative and grow downward into the dermis, forming hair germs and then hair pegs. The most proliferative cells in peg-stage follicles are at the bottom leading edge of the follicle, and these cells give rise to the epithelial matrix as they surround the dermal condensate that then becomes the dermal papilla (DP). Although the matrix is transient, proliferating and differentiating only during the growth (anagen) phase of the hair cycle, the DP remains permanently associated with each follicle.

Figure 3.

Embryonic hair follicle morphogenesis and the adult hair cycle. (A) The process of follicle morphogenesis occurs in several overlapping waves that begin at E14.5 when small invaginations termed placodes appear in the basal layer of the epidermis, accompanied by aggregations of dermal cells termed dermal condensates. Cells of the placode proliferate and grow downward into the dermis to form hair germs (~E16.5–E17.5). Next, during the peg stage (~E18.5–P0), transit-amplifying matrix cells appear at the base of the follicle and encapsulate the dermal papilla (DP). The upper portion of the follicle also becomes separated into the outer root sheath (ORS) and inner root sheath (IRS) at this time. Soon thereafter (~P1–P3), fully differentiated hair shafts and sebaceous glands (SGs) appear, and follicle morphogenesis reaches completion at about P9. At this time, follicles reach their maximum length, marking entrance into the anagen phase of the first hair cycle. After production of the first hair coat, follicles transition to the catagen phase of the hair cycle (~P16–P19), where the matrix undergoes apoptosis and degenerates into a regressing epithelial strand that draws the DP upward to rest just below the base of the first “club” hair, which is surrounded by the newly formed adult bulge niche. (B) Direct contact between the DP and adult bulge cells indicates the onset of telogen (~P20). Soon thereafter, at about P21, bulge stem cells are activated and a secondary hair germ grows downward from the base of the bulge niche, signaling entry into the anagen phase of the next hair cycle. The emergence of a new hair follicle from the side of the original club hair lends the stem cell niche its characteristic “bulge” morphology and divides the CD34-positive stem cells into two populations based on high or low integrin expression levels and adherence to the BM. In a process that has many similarities to that of initial hair follicle morphogenesis, the secondary germ expands and gives rise to a new matrix that begins to produce the differentiated lineages of the IRS and hair shaft. This new hair shaft then exits from the same channel as the existing club hair. After several weeks of growth, anagen ceases and follicles enter catagen, again drawing the DP upward to rest below the bulge stem cell niche. After a variable period of time, bulge stem cells are again activated to initiate a new hair growth cycle. For a comprehensive analysis of the details and classification of hair follicle morphogenesis and adult hair cycling, see Muller-Rover et al. (2001), Stenn and Paus (2001), and Schmidt-Ullrich and Paus (2005).

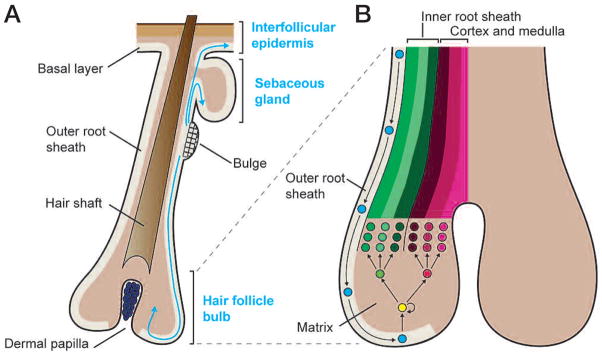

The matrix produces two differentiating structures: a three-layered inner root sheath (IRS) and a three-layered central hair shaft. The IRS forms first, providing the channel for the emerging hair. Both of these structures are internal to the outer root sheath (ORS), whose cells are in direct contact with the basement membrane and are topologically contiguous with the basal layer of the interfollicular epidermis. Reciprocal signaling between the DP and TA matrix cells in the bottom portion of the hair follicle, or bulb, allows the matrix progeny to engage in the distinct programs of gene expression that generate the full complement of differentiated cell lineages in the hair follicle.

At birth, sebaceous gland precursor cells appear in the upper portion of the ORS, and the sebaceous gland forms shortly thereafter (Horsley et al. 2006). For most backskin follicles, maturation is completed toward the end of the first postnatal week, when follicle downgrowth stops and the upward-moving, terminally differentiated hairs break through the skin surface (for review, see Schmidt-Ullrich and Paus 2005). As the hair shaft elongates, neural-crest-derived melanocytes, located on the epithelial side of the BM of the hair bulb, provide pigment to the differentiating cells of the hair shaft, giving them their color. In humans, melanocytes also disperse within the basal layer of the epidermis.

The developmental decision to form a hair follicle is the result of mesenchymal-epithelial cross-talk that integrates multiple instructive signals necessary to initiate hair follicle morphogenesis. These signaling cues include Wnt/β-catenin, sonic hedgehog (Shh), fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), and bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs). Several lines of evidence suggest that activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in epithelial cells is a key initial step in placode formation. The bipartite transcription factor complex composed of the DNA-binding protein LEF1 and its activation partner (stabilized β-catenin) can be readily detected in the nuclei of developing placode cells, and the “Wnt reporter” gene TOPGAL, containing an enhancer element composed of multimerized LEF1 binding sites, confirms the specific transcriptional activity of these complexes in the placode (van Genderen et al. 1994; Zhou et al. 1995; DasGupta and Fuchs 1999; Millar 2002). Notably, when the Wnt inhibitor Dickoff 1 (Dkk1) was expressed ectopically or when β-catenin was conditionally targeted for ablation in epithelial cells, hair follicle morphogenesis was blocked altogether, whereas mice lacking LEF1 displayed a reduced number of follicles (van Genderen et al. 1994; Huelsken and Birchmeier 2001; Andl et al. 2002). Strong evidence for Wnt signaling as a sufficient, instructive cue for placode formation came from experiments expressing excessive stabilized β-catenin in the epithelium, which resulted in super-furry mice exhibiting ectopic hair follicles within their interfollicular epidermis (Gat et al. 1998). Recently, Cotsarelis and colleagues (Ito et al. 2007) showed that when the skin of mice is severely wounded, endogenous Wnt signaling is elevated in the regenerating epithelium and this leads to the induction of hair follicle formation from epidermal stem cells. Taken together, these findings underscore the role for Wnt signaling and stabilized β-catenin in governing the choice of whether to become epidermis or hair follicle.

In contrast to Wnt signaling, which is activated during placode formation, BMP signaling must be inhibited for placode morphogenesis to progress. One dermal cue that appears to be particularly critical is the BMP inhibitory protein Noggin, whose absence severely impairs hair follicle morphogenesis (Botchkarev et al. 1999) as well as hair cycling (Botchkarev et al. 2001). When skin is genetically engineered to overexpress Noggin, genes controlling cell cycle progression are enhanced (Sharov et al. 2006). Consistent with these findings, mice conditionally null for the BMPR1a receptor in the epithelium form the correct number of hair follicles, which are later blocked in differentiation of the IRS and hair shaft (Kobielak et al. 2003; Andl et al. 2004; Ming Kwan et al. 2004; Yuhki et al. 2004). The interplay between the Wnt and BMP pathways is highlighted by the requirement of BMP inhibition for proper LEF1 expression in the placode (Jamora et al. 2003; Kobielak et al. 2003; Andl et al. 2004; Zhang et al. 2006a).

Interestingly, although this paradigm serves the bulk of follicle morphogenesis, the external cues that trigger these internal regulatory processes differ for the formation of the large primary guard hairs. The guards are the first hair follicles to appear in embryonic backskin, and they are uniquely dependent on a ligand–receptor complex composed of the TNF-related ectodysplasin (EDA) and the EDA receptor (EDAR) (Schmidt-Ullrich and Paus 2005). Notably, EDA/EDAR signaling results in induction of two BMP inhibitors different from Noggin (Pummila et al. 2007). EDA is itself a target of Wnt signaling (Laurikkala et al. 2001) that is already active in all other hair follicles at this stage, as judged from TOPGAL reporter activity and LEF1/β-catenin (DasGupta and Fuchs 1999). Thus, although the initiating events may differ, the recipe for hair follicle morphogenesis has many common ingredients across different hair types.

To drive hair follicle morphogenesis, signaling pathways ultimately have to elicit changes in the expression and dynamics of the ECM, cytoskeleton, and cell–matrix and cell–cell junction proteins in order to remodel the epithelium from its single layer to a hair placode. Several changes that accompany this process involve down-regulation of some adhesion proteins, such as E-cadherin, and up-regulation of others, such as P-cadherin (Jamora et al. 2003). One intriguing intersection between signaling and cytoskeletal organization is that the E-cadherin gene itself harbors a functional LEF1-binding site and is down-regulated concomitant with the appearance of Wnt reporter activity in developing placodes (Jamora et al. 2003). Additional links between signaling and cytoskeletal organization are Cdc42 and Rac1, both essential for maintaining follicle stem cells (Benitah et al. 2005; Chrostek et al. 2006; Wu et al. 2006). Although best understood for their roles in actin–cell junction dynamics and cell junction formation, Cdc42 and Rac1 also seem to act as effectors of Wnt signaling. It has been posited that Cdc42 functions in β-catenin stabilization (Wu et al. 2006) and that Rac1 functions in nuclear β-catenin localization (Wu et al. 2008). These new findings provide tantalizing glimpses as to how external cues received by the single layer of epidermal cells can translate into the early steps of hair follicle morphogenesis.

Once the placode forms, signaling events downstream from Wnts/BMPs drive the downgrowth and maturation of hair follicles. Shh is an early gene expressed downstream from Wnt/BMP receptor signaling (and EDA/EDARs in the case of guard hairs) once placodes have formed (Oro et al. 1997; Gat et al. 1998; Morgan et al. 1998; St-Jacques et al. 1998). Without Shh, hair follicles arrest at the placode stage and fail to form a dermal condensate, suggesting critical roles for Shh in proper epithelial-mesenchymal signaling and the dramatic expansion of cells involved in the transition from a placode to a mature follicle (Hardy 1992; St-Jacques et al. 1998; Oro and Higgins 2003; Levy et al. 2007). That said, many facets of Shh’s role in skin appendage formation remain mysterious. This is perhaps best exemplified by recent studies showing that abrogation of Shh responsiveness in the epithelium by conditional targeting of the transmembrane protein Smoothened leads to hair follicles that adopt features of mammary glands during development (Gritli-Linde et al. 2007).

THE HAIR FOLLICLE BULGE: A RESERVOIR OF SLOW-CYCLING MULTIPOTENT ADULT STEM CELLS

As a normal feature of skin homeostasis, the hair follicle undergoes cyclic bouts of degeneration and regeneration, producing a new hair with each cycle. During the hair growth phase of the hair cycle (anagen), the DP acts as a signaling center for the epithelial-mesenchymal cross-talk that regulates the balance between matrix cell proliferation and hair production (Schmidt-Ullrich and Paus 2005; Alonso and Fuchs 2006). TA matrix cells proliferate rapidly during anagen but then disappear when follicle growth ceases. After the anagen phase of the first hair cycle in postnatal mice, which is an extension of initial follicle morphogenesis, follicles enter a destructive phase (catagen) (Fig. 3A). Beginning at about P16, this stage is initially characterized by massive apoptosis of matrix cells. During the ensuing 3 days, the hair bulb of each follicle degenerates into an epithelial strand that contracts, dragging the DP upward to the base of the permanent, noncycling portion of the follicle.

In mice, these backskin follicles remain in a dormant resting phase (telogen) for several days before initiating the next anagen phase (Fig. 3B). The anagen and catagen phases are relatively constant in length, whereas the telogen phase of the second adult hair cycle lasts more than 3 weeks and the third is even longer. The ability of old club hairs to remain in their socket through several rounds of hair cycling means that only a portion of the hair coat is replaced during each cycle. Although the first several rounds of the hair cycle are synchronized, individual follicles become more asynchronous as animals age, concomitant with the extension of time spent in the telogen phase of the cycle.

The ability of the postnatal hair follicle to regenerate necessitates a reservoir of stem cells. Although long surmised, it has only recently been established that follicular stem cells reside in a niche within the ORS (Fig. 3B). This niche is located at the base of the telogen-phase follicle. In approximately 3-week-old mice, as the new follicle develops adjacent to the previous one, these stem cells reorganize, creating a bulge in the ORS that allows the new hair to share the same orifice as the club hair.

Lineage-tracing experiments identified the bulge as the source of cells that can give rise to new hair follicles in normal homeostasis, the interfollicular epidermis during wound repair, and the sebaceous gland when its own resident stem cells are defective (Fig. 4A) (Morris et al. 2004; Tumbar et al. 2004; Horsley et al. 2006). Clonal expansion of individually marked bulge cells, followed by engraftment, revealed that the bulge contains multipotent stem cells, rather than a heterogeneous mixture of epidermal, sebaceous gland, and hair follicle stem cells (Blanpain et al. 2004; Claudinot et al. 2005). The ability to culture and clonally expand bulge stem cells has also underscored their long-term potential for self-renewal and their intrinsic ability to maintain multipotency outside the niche. That said, the in vivo microenvironment of the stem cell niche is clearly important in directing cell fates, because bulge stem cells normally function in cyclic hair follicle growth and contribute to the interfollicular epidermis only when a wound creates a signal that recruits them to this lineage (Ito et al. 2005; Levy et al. 2005, 2007).

Figure 4.

Multipotency of bulge epithelial stem cells and lineage decisions in the hair follicle. (A) Epithelial stem cells reside in a specialized niche in the upper ORS of each hair follicle and can give rise to all three epithelial lineages of the skin. During normal homeostasis, bulge stem cells are periodically activated to form a new hair follicle. During the hair follicle growth period (anagen), bulge cells migrate down the lower ORS toward the matrix, which is a specialized population of highly proliferative transit-amplifying cells responsible for producing a new hair. Bulge stem cells can also migrate to and differentiate along an SG lineage when sebaceous progenitors are absent or impaired. In a wound environment, bulge stem cells can also migrate upward and out of the hair follicle to contribute to regeneration of the interfollicular epidermis. (B) As bulge progeny migrate down the ORS, they subsequently enter the matrix. Matrix cells then detach from the BM and differentiate along one of six hair lineages, three of which comprise the IRS and three the cortex and medulla of the hair shaft. Intimate contact with the dermal papilla is essential for maintaining the high proliferative capacity of the matrix and driving lineage decisions.

Nucleotide pulse-chase experiments show that the cells within the bulge proceed through the cell cycle, but they retain the label longer than other epithelial cells within the skin (Bickenbach and Mackenzie 1984; Cotsarelis et al. 1990; Potten 2004). Recent studies monitoring dilution of the histone label over multiple hair cycles in pulse-chased inducible histone H2B–GFP mice led to the conclusion that most if not all bulge stem cells divide an average of three times during the hair cycle (Waghmare et al. 2008). Both nucleotide and H2B–GFP pulse-chase experiments further show that at the start of each new hair cycle, some label-retaining cells exit from the base of the bulge, lose their label, and proliferate to form the new hair follicle (Taylor et al. 2000; Tumbar et al. 2004). Together, these studies support the pioneering observations of Barrandon and coworkers on whisker follicles (Oshima et al. 2001) that showed that stem cells migrate from the bulge along the ORS to the base of the follicle where they become rapidly proliferating TA matrix cells (Fig. 4B). The ability of bulge cells to periodically exit their niche throughout anagen provides an explanation for how the size of the bulge remains constant during the hair cycle despite the continuous slow division of bulge cells during anagen.

When coupled with the view that stem cells divide asymmetrically (Morrison and Kimble 2006), the label-retaining feature of bulge cells has revived the hypothesis that a self-renewing daughter stem cell might be able to selectively retain the master DNA template strands, thereby minimizing the number of replication-associated DNA mutations it acquires (Cairns 1975). The notion is attractive, and a possible mechanistic basis has recently been proposed for how such segregation of DNA strands might occur within the existing framework for DNA replication (Lew et al. 2008). That said, pulse-chase experiments with nucleotides and histone H2B–GFP label the same bulge stem cells (Tumbar et al. 2004; Waghmare et al. 2008). Given that nucleosomal histones distribute evenly between the two DNA daughter strands, and H2A–H2B dimers exchange between different nucleosomes throughout the genome during interphase (Luger and Hansen 2005), if the immortal strand hypothesis is true, new biology would be needed to explain nonrandom segregation of nucleosomes in cycling bulge cells. At present, the simplest explanation for the existing data is that bulge cells divide cycle less frequently than their progeny but still segregate their DNA randomly.

ADULT FOLLICLE STEM CELLS: HOW DO THEY DIFFER FROM RAPIDLY PROLIFERATING EPIDERMAL CELLS?

To understand the special features of the bulge, we and other investigators have conducted microarray profiling on purified bulge cells. Approximately 150 genes are preferentially expressed in the bulge relative to the proliferating basal cells of the epidermis (Blanpain et al. 2004; Morris et al. 2004; Tumbar et al. 2004). The purification of bulge stem cells has been accomplished by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) based on either (1) bulge cell surface markers α6 integrin and CD34 coupled with K14-GFP transgene expression (Blanpain et al. 2004), (2) K15-GFP transgene expression (Morris et al. 2004), or (3) the H2B–GFP pulse-chase experiment outlined above (Tumbar et al. 2004). Although each of these different procedures marks slightly different cell populations, the array data are in quite good agreement, enabling researchers to exploit this information to learn more about follicle stem cells. Additionally, some of the markers, e.g., Lgr5, are up-regulated not only in the bulge, but also in other stem cells (Barker et al. 2007), suggesting that common features of stemness are reflected in these transcriptional arrays and are intrinsic to the hair follicle stem cells.

Like the embryonic epidermis, bulge cells are Wnt-responsive, as judged from their expression of two LEF1-related DNA-binding proteins (TCF3 and TCF4) and several Wnt receptor proteins (Fzds). However, at least in telogen, most bulge cells appear to be in a state of Wnt inhibition, as judged from the array data and the lack of detectable nuclear β-catenin or Wnt reporter (TOPGAL) activity (Fig. 5) (DasGupta and Fuchs 1999). These findings are consistent with recent studies showing that TCF3 can function as a repressor when β-catenin is absent or underrepresented and that TCF3 on its own functions to repress the differentiation of skin stem cells (Nguyen et al. 2006b). Nevertheless, bulge stem cells seem to require at least a low level of Wnt signaling to maintain their identity, because conditional ablation of β-catenin in adult bulge cells results in their loss and subsequent hair follicle degeneration (Lowry et al. 2005). Coupled with the finding that transgenically elevating the levels of stabilized β-catenin results in early bulge cell activation and premature entry into anagen, it appears that bulge stem cells are responsive to a gradient of Wnt activity, with low levels required for self-renewal and higher levels driving activation (Van Mater et al. 2003; Lo Celso et al. 2004; Lowry et al. 2005).

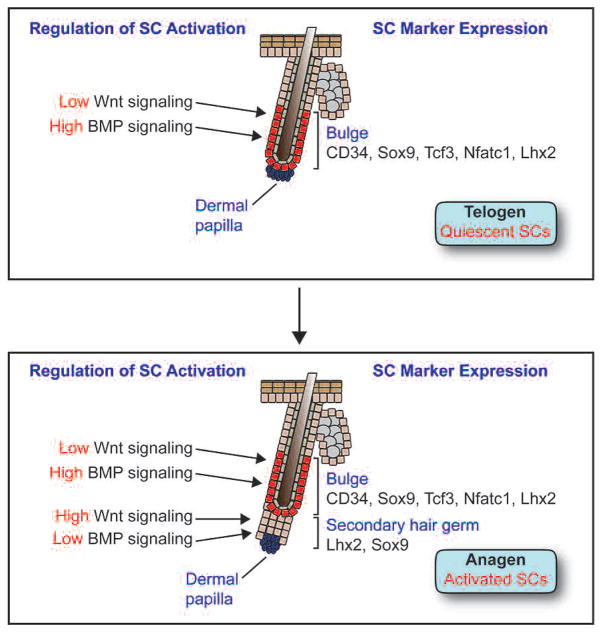

Figure 5.

Regulation of stem cell identity and activity in the adult bulge stem cell niche. (Top) In telogen-phase hair follicles, stem cells residing in the bulge are quiescent and express the markers CD34, Sox9, Tcf3, Nfatc1, and Lhx2. High levels of BMP signaling maintain stem cells in a quiescent state, whereas low levels of Wnt signaling may help to maintain stem cell identity but are insufficient to drive SC activation. (Bottom) In early anagen-phase hair follicles, stem cells in the bulge proliferate and give rise to a secondary hair germ that loses most stem cell markers but still retains Sox9 and Lhx2 expression. In contrast to the bulge, BMP signaling is down-regulated and Wnt signaling is up-regulated in the germ, allowing cells to proliferate rapidly in order to produce a new hair follicle.

In adult hair follicles, the role of Wnt signaling extends beyond stem cells to the TA matrix cells. In fact, our initial studies on LEF1/TCFs emanated from our identification of functional, conserved LEF1-binding sites in the promoters of the hair keratin gene family (Zhou et al. 1995). Moreover, the strongest Wnt reporter activity occurs in matrix cells as they withdraw from the cell cycle, initiate hair keratin gene expression, and commit to terminally differentiate (DasGupta and Fuchs 1999). Perhaps most intriguing is that in humans and mice, stabilizing mutations in β-catenin results in pilomatricomas, which are tumors composed of proliferating matrix-like cells and differentiated hair shaft cells (Gat et al. 1998; Chan et al. 1999). Thus, although β-catenin stabilization and TCF3/4 are required to activate the follicle stem cells and initiate the follicle lineage, a much stronger signal involving Wnt3 (Millar et al. 1999) and LEF1 is required for hair shaft differentiation. Coupled with requirements of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in placode formation, these results highlight the manner in which a single signaling pathway functions at multiple times and locations to direct different aspects of hair follicle function. Interestingly, it was recently shown that human and mouse SQCCs are also dependent on β-catenin (Malanchi et al. 2008), raising the possibility that Wnts have even broader roles in skin tumorigenesis than previously thought.

BMP signaling is another pathway that exerts its effects at multiple points in follicle function, including the regulation of bulge stem cells (Fig. 5). In the absence of BMPr1a, otherwise quiescent bulge stem cells begin to proliferate rapidly and display markers of activated stem cells, e.g., Lhx2, Sox4, Sox9, and Shh, demonstrating that in contrast to Wnt signaling, active BMP signaling maintains bulge cell quiescence in vivo (Kobielak et al. 2007). However, these abnormally activated stem cells are later blocked in terminal differentiation stages because they can no longer receive the BMP signals necessary for IRS and hair shaft differentiation (Millar 2002; Kobielak et al. 2003; Andl et al. 2004; Yuhki et al. 2004). Although the BMPr1a-deficient bulge cells are no longer slow-cycling and do not express appreciable CD34, follicle cells lacking BMPR1a are still able to repair epidermis in a wound response and they generate what appear to be long-lived tumors (Zhang et al. 2006a; Kobielak et al. 2007). When taken together with the recent studies of Huelsken and colleagues (Malanchi et al. 2008), these studies are tantalizing in that they suggest that relative quiescence may not be an essential hallmark of follicle stem cells, at least in their tumorigenic state.

In vitro, bulge stem cells respond to BMP signaling by transient withdrawal from the cell cycle (Blanpain et al. 2004). In vivo, BMPs are made not only by telogen-phase bulge cells (Blanpain et al. 2004), but also by the surrounding dermis (Plikus et al. 2008). Interestingly, BMP expression in the dermis decreases in late telogen, coinciding with the timing of elevated WNT/β-catenin activity in follicle stem cells (Plikus et al. 2008). When coupled with the expression of multiple BMP antagonists by the DP (Rendl et al. 2005, 2008), these data suggest a model whereby the telogen-phase bulge niche receives multiple BMP signals that maintain its stem cells in a quiescent state, but as threshold levels of BMP inhibitors (and most likely additional stimulants) accumulate, the balance is tipped from stem cell quiescence to activation. How this mechanism might govern the age-related increase in telogen length still remains a mystery. However, the fact that bulge cells in the whisker follicle are able to initiate a new anagen without coming near the DP suggests that additional signaling pathways also operate to regulate bulge stem cell activity (Oshima et al. 2001).

The effects of BMPs on bulge stem cells appear to be mediated through the canonical pathway, based on the presence of phosphorylated Smad1 in the bulge and the fact that conditional loss of its partner SMAD4 results in features that partially resemble those of the BMPr1a null state (Yang et al. 2005). There are likely to be many downstream effectors of BMP/SMAD signaling that maintain stem cell quiescence, but one key direct target appears to be NFATc1, encoding a transcription factor specifically expressed in the bulge (Tumbar et al. 2004; Horsley et al. 2008). Whereas BMP signaling dramatically enhances NFATc1 transcription, NFATc1’s nuclear localization and activity depend on a calcium/calcineurin-mediated mechanism. Although the underlying mechanisms remain to be elucidated, loss of NFATc1 leads to continuous cycling of hair follicles without resting in telogen. Moreover, the immunosuppressive drug cyclosporine A (CsA), which inhibits calcineurin, acts on the bulge to promote proliferation (Horsley et al. 2008). This finding is particularly intriguing in light of the well-known side effects of CsA on promoting hair growth and the established, often negative, effects of calcium on cell cycle control. From these data, a model emerges whereby BMP and calcium act coordinately to regulate NFATc1 and an additional downstream BMP effector PTEN (a dual specificity phosphatase implicated in β-catenin stabilization), which together function by holding bulge cells in a relatively quiescent, slow-cycling state (Fig. 5) (Zhang et al. 2006b; Kobielak et al. 2007; Horsley et al. 2008).

HOMEOSTASIS IN THE SEBACEOUS GLAND

An appendage of the hair follicle, sebaceous glands (SGs) are located above the bulge and just below the hair shaft orifice at the skin surface. The major role of the gland is to generate terminally differentiated sebocytes that degenerate to release lipids and sebum and lubricate the skin surface as they are expelled from the SG into the hair canal. Because of this holocrine manner of secretion, SG homeostasis necessitates a population of progenitor cells that can regenerate the differentiated cells constantly being lost. Lineage tracing by retrovirus-mediated gene transfer suggests that a small population of cells near or at the base of the SG might be stem cells (Ghazizadeh and Taichman 2001).

Recently, the transcriptional repressor protein Blimp1 was identified in a genetic screen for hair follicle transcription factors, and it was shown to mark a small population of cells at the SG base (Horsley et al. 2006). These Blimp1-positive cells appeared to be in close association with the BM that surrounds the gland and are contiguous with the BM underlying the epidermis and surrounding the hair follicle. Accordingly, the Blimp1-positive SG cells also express K5 and K14, markers of the basal layer in epidermis and follicles. Genetic lineage-tracing experiments revealed that Blimp1-positive SG cells can regenerate the entire gland, including the sebocytes. When Blimp1 was conditionally targeted for ablation, SGs became larger. The likely explanation for this alteration stems from Blimp1’s ability, first detected in B lymphocytes (Chang et al. 2000), to transcriptionally repress c-myc, a gene known to induce SG hyperplasia and sebocyte differentiation at the expense of hair follicle differentiation (Arnold and Watt 2001; Waikel et al. 2001). However, if Blimp1 controls production of differentiated cells by SG progenitors, why don’t the enlarged glands eventually degenerate after an initial period of hyperplasia?

Although further studies are needed, the underlying explanation could be rooted in the ability of bulge stem cells to become mobilized when the SG progenitor cell population is depleted. As judged from BrdU pulse and pulse-chase experiments, Blimp1-negative bulge cells show signs of active cycling and reduced label retention in the absence of Blimp1-marked SG progenitors (Horsley et al. 2006). In this regard, the behavior of bulge stem cells in response to a loss of Blimp1 in SG progenitors resembles their response to the epidermis lost upon injury in normal mice. Such a precursor–product relationship between the bulge and other skin stem cell populations has also been documented by engraftment experiments with isolated bulge stem cells (Fig. 4) (Blanpain et al. 2004; Claudinot et al. 2005).

TRACING THE EMBRYONIC ROOTS OF ADULT STEM CELLS IN THE FOLLICLE

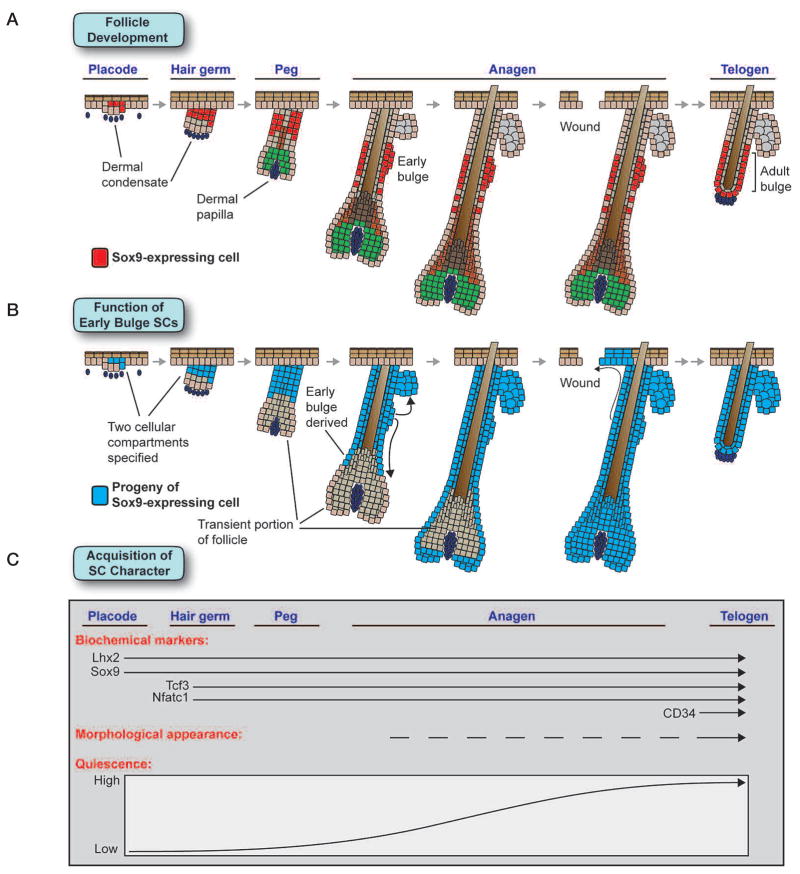

Major questions in stem cell biology are where and when adult stem cell niches become established. We recently exploited the relatively slow-cycling behavior of adult follicle stem cells to trace their developmental origins (Nowak et al. 2008). Our embryonic pulse-chase studies revealed that, surprisingly, label-retaining cells are specified early in skin development and later become adult bulge stem cells. Moreover, we have discovered that these early label-retaining cells express a number of bulge-preferred transcription factors even though the widely used bulge marker CD34 (Trempus et al. 2003) is not expressed in these early bulge cells. Sox9 (Vidal et al. 2005) and Tcf3 (Nguyen et al. 2006b) emerged as key potential regulators of stem cell identity, marking both early and adult stem cells. Moreover, in contrast to CD34, these transcription factors also mark the trail of follicle stem cells that appear to migrate from the bulge to the TA matrix during anagen (Nowak et al. 2008).

By taking advantage of Sox9 as a marker of early bulge cells, we discovered that the hair placode that we recently transcriptionally profiled on the basis of P-cadherin and K14-GFP-actin expression (Rhee et al. 2006) is not a homogeneous cluster of cells but rather consists of two populations that can be distinguished by their differential expression of Lhx2 and Sox9. Our Sox9 genetic marking studies suggest that the early basal placode cells that are marked by Lhx2 and high P-cadherin expression are transient rather than long-lived progenitors (Fig. 6). They give rise to the initial hair bulb but then seem to disappear entirely by approximately P7. In contrast, the Sox9-expressing suprabasal placode cells give rise not only to the long-lived self-renewing stem cells of the bulge, but also to the entire pilosebaceous unit. Moreover, the early emergence of a niche of Sox9-positive label-retaining cells is accompanied by their concomitant expression of Lhx2, Nfatc1, and Tcf3. Thereafter, these markers identify the multipotent stem cell niche of the hair follicle.

Figure 6.

Embryonic specification of the hair follicle stem cell population. (A) Sox9, a gene essential for specifying the hair follicle stem cell population, is expressed in suprabasal cells of the placode at the first stage of hair follicle morphogenesis. As development proceeds, Sox9 remains in the upper portion of the ORS, marking the early follicle stem cell population, as well as in their progeny that migrate down the ORS toward the matrix. In adult follicles, Sox9 remains expressed in the bulge stem cell niche. (B) Genetic marking studies of Sox9-expressing cells show that hair follicles are initially composed of two cell populations, Sox9-expressing early stem cells and transient Sox9-negative cells that give rise to the initial matrix. As follicle morphogenesis proceeds, the progeny of Sox9-expressing cells move down the ORS and completely replace the initial matrix population. Additionally, progeny of Sox9-positive cells give rise to the SG lineage and can help repair the interfollicular epidermis in a wound environment. By the time hair follicle morphogenesis has finished, hair follicles are entirely derived from Sox9-expressing cells. (C) Markers and functional characteristics of the hair follicle stem cell population are acquired in a stepwise manner. The transcription factors Lhx2 and Sox9 are expressed at the first placode stage of morphogenesis, whereas Tcf3 and Nfatc1 appear later at the hair germ stage. Although all four of these genes mark both early and adult stem cells, CD34 is only up-regulated in adult follicle stem cells. Morphologically, the location of early stem cells in the follicle can be inferred by a thickening in the ORS that appears during late stages of morphogenesis and becomes much more pronounced when the adult bulge stem cell niche forms during the first telogen. Although all early stem cells divide at least several times during follicle morphogenesis, they gradually increase their slow-cycling character as the rate of hair follicle growth decreases. Adult stem cells in resting telogen hair follicles are highly quiescent, but they undergo periods of reduced quiescence in the growing anagen phase of the hair cycle.

Although the functional significance of separate TA and stem cell populations in development remains unclear, precedence exists in blood development, where a transient burst of primitive hematopoietic progenitors drives initial blood formation before being later replaced by definitive hematopoietic stem cells (Orkin and Zon 2008). The existence of a transient Sox9-independent population explains why in mouse embryos, conditionally targeted for Sox9, HF maturation and hair production begin normally but then halt midstream (Vidal et al. 2005; Nowak et al. 2008). These findings also provide compelling support for the notion that whether in the postnatal hair cycle or during morphogenesis, the matrix relies upon input from early Sox9-positive stem cells for its maintenance and cannot enhance its own self-renewal to compensate for a lack of bulge stem cell input. These studies further strengthen the evidence that stem cell migration occurs during hair follicle morphogenesis and that the fueling of the matrix by Sox9-positive bulge cells is functionally required for hair production (Fig. 6).

Another surprising finding that emerged from targeting Sox9 ablation in the embryo was that the early bulge cells are required not only to complete hair follicle morphogenesis, but also to initiate SG morphogenesis. Our studies further revealed that without early bulge stem cells, wound repair of the IFE is markedly impaired and also that early Sox9-derived progeny contribute long-term to repopulating wounded IFE with close to 100% efficiency (Nowak et al. 2008). Prior lineage-tracing studies with bulge stem cells genetically marked by K15-CrePR suggest that adult bulge cells may contribute only transiently to wound repair (Ito et al. 2005). Our studies raise the possibility that early bulge stem cells may have greater potential than their adult counterparts. These studies provide major new insights into the existence and usage of a follicle stem cell population at a stage and for a purpose that has hitherto been unanticipated. Future exploration of the relationship between embryonic and adult skin stem cells will undoubtedly open new avenues for defining the features of stemness in the skin.

UNIFYING FEATURES OF SKIN STEM CELLS

An emerging view of skin stem cells is that there appears to be three different niches for skin stem cells: the follicle bulge, the base of the sebaceous gland, and the basal layer of the epidermis. It has not yet been resolved whether the basal layer contains a subset of stem cells as originally posited (Potten 1974) or whether the basal compartment is composed of a single progenitor population, as more recently proposed (Clayton et al. 2007). However, at least in the developing mouse skin, the division rates of cells within the basal layer of the epidermis are significantly more uniform than those in the hair follicle, where the emergence of stem cells is coincident with their adoption of slow-cycling behavior (Nowak et al. 2008).

Are there unifying features of keratinocyte stem cells and the activation mechanisms that guide them along specific lineages? Although the answers to these questions are still at the molecular drawing board, it seems reasonable to predict that, given the similarities in their niche environments and their common developmental origin, certain features should be shared among all three stem cell populations. Notably, all three progenitor populations express K5, K14, and ΔNp63. Although ΔNp63 has also been implicated in differentiation, it remains one of the best candidates to date for a common gatekeeper for proliferation in epithelial stem cells (Truong et al. 2006; Senoo et al. 2007). Cells within all three progenitor pools also express E-cadherin and display elevated levels of adherens junctions. A reduction in E-cadherin appears to be an essential feature in mobilizing embryonic epidermal cells to invaginate to form a hair follicle (Jamora et al. 2003), and reductions in α-catenin and p120-catenin have also been linked to epithelial cancers, a less organized form of invagination (Scott and Yap 2006; Reynolds 2007). Such studies make it tempting to speculate that the mobilization of stem cells to exit their niches and either form a hair follicle or repair wounds may entail the remodeling of intercellular junctions.

The three progenitor compartments are also typified by their proximity to an underlying BM, and all three types of progenitors express integrins, including α6β4 and α3β1, as well as their associated proteins. The higher the integrin level, the greater the proliferative potential, as judged from the early studies of Jones and Watt on cultured epidermal stem cells (Jones et al. 1995). One intriguing aspect is the up-regulation of β6 integrin and the presence of the αvβ6 integrin ligand tenascin C that occurs in bulge stem cells as they transit from telogen to anagen (Tumbar et al. 2004). Similar changes are seen in the epidermal basal layer in response to injury (Fassler et al. 1996) and in tumorigenesis (Guasch et al. 2007), leading to the speculation that these changes might be important in understanding how stem cells become activated to migrate from their niche and differentiate along a specific lineage.

Although keratinocytes with proliferative capacity are often associated with an underlying BM, some bulge stem cells seem to be suprabasal. Thus, during the second postnatal anagen, the α6-integrin–low bulge stem cells are uniquely positioned between two differentiated hair shafts in mature follicles, yet they are nevertheless CD34-positive, slow-cycling, and transcriptionally and functionally similar to the α6-integrin–high bulge cells that appear earlier in the niche (Blanpain et al. 2004). How these α6-integrin–low cells manage to maintain their stem cell features and migrate downward to contribute to future hair follicle development will be a valuable area of future study. In a similar vein, the Sox9-positive cells that first appear in developing placodes appear to be primarily suprabasal, again hinting at the possibility of cells to possess stem cell character, at least transiently, in the absence of basement adherence.

The similarities in keratinocyte stem cell behavior may extend further to shared principles and pathways, even if the precise players differ. One example is Blimp1, which appears to mark SG progenitors and repress c-myc expression (Horsley et al. 2006), whereas Miz1 seems to have a similar c-myc repressive function in the epidermal basal layer (Gebhardt et al. 2006). The outcome of c-Myc expression is keratinocyte proliferation in both the SG and epidermis, leading to the postulate that c-Myc might control the conversion of stem cells to transit amplifying, i.e., committed cells (Waikel et al. 2001; Frye et al. 2003). In this regard, it is intriguing that later in the epidermal lineage, Ovo1, yet another transcriptional repressor of c-Myc, is expressed suprabasally, where it may act to prevent proliferation after TA cells commit to terminally differentiate (Nair et al. 2006).

Another signaling pathway likely to impact on more than one keratinocyte stem cell niche is Notch, which controls selective cell-fate determination through close-range interactions not only in the epidermis, but also in the hair follicle and the SG (Yamamoto et al. 2003; Pan et al. 2004; Vauclair et al. 2005; Blanpain and Fuchs 2006; Estrach et al. 2006; Nguyen et al. 2006a). The studies to date support a role for Notch in activating the keratinocyte switch from the undifferentiated to differentiated fate.

Although Notch signaling appears to have a similar role throughout different keratinocyte populations in the skin, other signaling pathways seem to have more potent effects on one lineage over another. Thus, in the follicle bulge, stem cells enter the new hair cycle when threshold levels of stabilized β-catenin are reached (Gat et al. 1998; Huelsken et al. 2001; Van Mater et al. 2003; Lo Celso et al. 2004; Lowry et al. 2005). Conversely, a negative role for Wnt signaling has been proposed for SG fate determination, because SG hyperplasia occurs when a truncated version of LEF1 is expressed that is unable to associate with β-catenin (Merrill et al. 2001; Niemann et al. 2002). Although epidermal stem cells are seemingly unaffected by loss of β-catenin (Huelsken and Birchmeier 2001), they adopt a hair follicle cell fate when β-catenin is stabilized through either genetic manipulation or wounding (Gat et al. 1998; Ito et al. 2007). When taken with the recent observation that the basal epidermal layer of chemically induced β-catenin dependent SQCCs is positive for a number of bulge markers, including CD34 and Sox9 (Malanchi et al. 2008), Wnt/β-catenin signaling emerges as a promoting force for the establishment of bulge SC.

Given that cell-fate signaling pathways are often interdependent on one another, subtle perturbances of a single pathway can exert a potent impact on lineage determination, as recently demonstrated by Watt and colleagues (Estrach et al. 2006). In the precortex of the hair follicle (DasGupta and Fuchs 1999), where Wnt signaling is particularly high, the Wnt target gene Jag1 is expressed, leading to active Notch signaling in these cells and promoting proliferation and differentiation to produce hair (Estrach et al. 2006). Conversely, in the absence of Jag1, hair follicles fail to form, but the epidermis is unaffected. Thus, by activating expression of other signaling genes, Wnt signaling can accentuate its effects on a particular lineage within the skin.

CONCLUSIONS

In closing, the existence of different skin stem cell niches and the ability of cells in these niches to respond differentially to environmental cues has been an exciting new development in the skin field. Increasing knowledge about these stem cell populations during the past 5 years has begun to shed light on the similarities and differences among these niches. Important questions for the future are now raised. Are these different stem cell populations multipotent as recent studies suggest (Ito et al. 2007)? Is the multipotency of stem cells in response to wounding a reflection of mechanical disruption of the niche or a response to growth/differentiation factors released in a wound response? To what extent do the gene expression programs of other progenitor populations overlap with that of follicle stem cells and do these similarities reflect their self-renewing undifferentiated features? When do these different proliferative epithelial compartments form during skin development and how are their differences in gene expression influenced by their distinct in vivo microenvironments? What factors control the differences in the slow-cycling ability of different stem cell populations within the skin? The answers to these questions will bring us closer to a complete understanding of how stem cells are maintained in their undifferentiated growth-restricted state and what prompts them to become activated, exit their niches, and embark upon distinct lineages.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Howard Green, who many years ago inspired the field of skin stem cell biology with his pioneering work on human epidermal culture. Through his application of cultured keratinocytes to the treatment of burn patients, he taught the field the importance of bringing basic biology to a clinical setting. We thank former Green lab members James Rheinwald, Henry Sun, Fiona Watt, and Yann Barrandon, who helped to build the framework of molecular skin biology and who have provided valuable advice and insights to Elaine and her laboratory over the years. We are particularly grateful to the many members of the Fuchs lab, past and present, who contributed so mightily over the years to formulating our current knowledge of the molecular, cellular, and developmental biology of the skin and its associated genetic disorders. Finally, we thank our many colleagues in the field, both friends and competitors, for giving us the constructive criticism and motivation to do the best science possible and for making the field an enjoyable and interactive one. E.F. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. J.N. is supported by the National Institutes of Health MSTP grant GM07739. This work has been supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Starr Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Advance online articles have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet appeared in the paper journal (edited, typeset versions may be posted when available prior to final publication). Advance online articles are citable and establish publication priority; they are indexed by PubMed from initial publication. Citations to Advance online articles must include the digital object identifier (DOIs) and date of initial publication.

References

- Alonso L, Fuchs E. The hair cycle. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:391–393. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andl T, Reddy ST, Gaddapara T, Millar SE. WNT signals are required for the initiation of hair follicle development. Dev Cell. 2002;2:643–653. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andl T, Ahn K, Kairo A, Chu EY, Wine-Lee L, Reddy ST, Croft NJ, Cebra-Thomas JA, Metzger D, Chambon P, et al. Epithelial Bmpr1a regulates differentiation and proliferation in postnatal hair follicles and is essential for tooth development. Development. 2004;131:2257–2268. doi: 10.1242/dev.01125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold I, Watt FM. c-Myc activation in transgenic mouse epidermis results in mobilization of stem cells and differentiation of their progeny. Curr Biol. 2001;11:558–568. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00154-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzac F, Avolio M, Degani S, Kaverina I, Torti M, Silengo L, Small JV, Retta SF. E-cadherin endocytosis regulates the activity of Rap1: A traffic light GTPase at the crossroads between cadherin and integrin function. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4765–4783. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J, Kujala P, van den Born M, Cozijnsen M, Haegebarth A, Korving J, Begthel H, Peters PJ, Clevers H. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449:1003–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrandon Y, Green H. Cell migration is essential for sustained growth of keratinocyte colonies: The roles of transforming growth factor-α and epidermal growth factor. Cell. 1987a;50:1131–1137. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90179-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrandon Y, Green H. Three clonal types of keratinocyte with different capacities for multiplication. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1987b;84:2302–2306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.8.2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benitah SA, Frye M, Glogauer M, Watt FM. Stem cell depletion through epidermal deletion of Rac1. Science. 2005;309:933–935. doi: 10.1126/science.1113579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickenbach JR, Mackenzie IC. Identification and localization of label-retaining cells in hamster epithelia. J Invest Dermatol. 1984;82:618–622. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12261460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanpain C, Fuchs E. Epidermal stem cells of the skin. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:339–373. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanpain C, Lowry WE, Pasolli HA, Fuchs E. Canonical notch signaling functions as a commitment switch in the epidermal lineage. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3022–3035. doi: 10.1101/gad.1477606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanpain C, Lowry WE, Geoghegan A, Polak L, Fuchs E. Self-renewal, multipotency, and the existence of two cell populations within an epithelial stem cell niche. Cell. 2004;118:635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchkarev VA, Botchkareva NV, Nakamura M, Huber O, Funa K, Lauster R, Paus R, Gilchrest BA. Noggin is required for induction of the hair follicle growth phase in postnatal skin. FASEB J. 2001;15:2205–2214. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0207com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchkarev VA, Botchkareva NV, Roth W, Nakamura M, Chen LH, Herzog W, Lindner G, McMahon JA, Peters C, Lauster R, McMahon AP, Paus R. Noggin is a mesenchymally derived stimulator of hair-follicle induction. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:158–164. doi: 10.1038/11078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns J. Mutation selection and the natural history of cancer. Nature. 1975;255:197–200. doi: 10.1038/255197a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan EF, Gat U, McNiff JM, Fuchs E. A common human skin tumour is caused by activating mutations in β-catenin. Nat Genet. 1999;21:410–413. doi: 10.1038/7747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang DH, Angelin-Duclos C, Calame K. BLIMP-1: Trigger for differentiation of myeloid lineage. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:169–176. doi: 10.1038/77861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrostek A, Wu X, Quondamatteo F, Hu R, Sanecka A, Niemann C, Langbein L, Haase I, Brakebusch C. Rac1 is crucial for hair follicle integrity but is not essential for maintenance of the epidermis. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6957–6970. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00075-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]