Abstract

The limited potency of nitrous oxide mandates the use of a hyperbaric chamber to produce anesthesia. Use of a hyperbaric chamber complicates anesthetic delivery, ventilation, and electrophysiological recording. We constructed a hyperbaric acrylic-aluminum chamber allowing recording of single unit activity in spinal cord of rats anesthetized only with N2O. Large aluminum plates secured to each other by rods that span the length of the chamber close each end of the chamber. The 122 cm long, 33 cm wide chamber housed ventilator, intravenous infusion pumps, recording headstage, including hydraulic microdrive and stepper motors (controlled by external computers). Electrical pass-throughs in the plates permited electrical current or signals to enter or leave the chamber. In rats anesthetized only with N2O we recorded extracellular action potentials with a high signal-to-noise ratio. We also recorded electroencephalographic activity. This technique is well suited to study actions of weak anesthetics such as N2O and Xe at working pressures of 4–5 atm or greater. The safety of such pressures depends on the wall thickness and chamber diameter.

Keywords: Anesthesia, hyperbaric, electrophysiology, nitrous oxide, nociception, pain, spinal cord

1. Introduction

Recordings of neuronal action potentials have expanded our knowledge of the neurophysiology of the central nervous system, including spinal nociceptive processing. Such techniques have furthered our knowledge of how anesthetics suppress nociceptive processing and thereby produce immobility, a key anesthetic end-point (De Jong and Wagman, 1968;Jinks, Martin et al., 2003). Similarly, measurement of anesthetic effects on electroencephalographic (EEG) activity has advanced our understanding of how anesthesia produces unconsciousness, another critical clinical end-point. Isoflurane, halothane, barbiturates (such as pentobarbital) and urethane are often used in experimental procedures, yet these anesthetics have diverse receptor effects (Krasowski and Harrison, 1999;Hara and Harris, 2002). Thus, data interpretation can be difficult when trying to determine what receptor effect is important to a particular anesthetic endpoint. Some anesthetics, however, have more focused receptor effects. For example, nitrous oxide (N2O) and xenon have important effects at the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor (Jevtovic-Todorovic, Todorovic et al., 1998;de Sousa, Dickinson et al., 2000). In addition, the anatomic sites of action of N2O are better described as compared to other anesthetics (Sawamura, Kingery et al., 2000).

At clinically relevant concentrations most inhaled anesthetics can produce anesthesia under normobaric conditions, but N2O and xenon are weak anesthetics and require a hyperbaric chamber for use as a sole anesthetic (Antognini, Lewis et al., 1994;Gonsowski and Eger, 1994;Eger, Liao et al., 2006). Performing simple studies (such as determination of anesthetic requirements, i.e., minimum alveolar concentration, MAC) in a hyperbaric chamber is relatively straightforward (Gonsowski and Eger, 1994). But more complex neurophysiological experiments in whole animals (such as single unit recording in spinal cord) are technically demanding even at normobaric conditions, and have rarely been attempted under hyperbaric conditions (Smallman, Dickenson et al., 1989).

We constructed an inexpensive hyperbaric chamber that permits recording of spinal extracellular action potentials and EEG activity in intact animals anesthetized solely with N2O under hyperbaric conditions, thereby allowing investigation of N2O effects in the absence of other anesthetic drugs.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Chamber Construction

The hyperbaric chamber was patterned after a much smaller chamber used previously to determine minimum alveolar concentration (MAC) in rats (Gonsowski and Eger, 1994). The acrylic cylinder wall (thickness 1.27 cm, inside diameter 33 cm, and length 122 cm) was manufactured by Spartech-Townsend (Pleasant Hill, IA, USA). The ends were sanded and smoothed to ensure a good seal.

The ends of the cylinder fit into circular grooves 1.3 cm wide and 1 cm deep in two aluminum plates (5.1 cm thick, 50 cm tall, 50 cm wide; Figure 1). A smaller groove in this groove permitted placement of a rubber gasket that acted as a seal. Electrical pass-throughs (each with 12 wires) traversed the center of each plate, permitting passage of electrical current as needed for delivery of electrical power or for monitoring (Conax Technologies, Buffalo, NY). Six rods passed through holes drilled outside the larger groove, and nuts affixed to the rods allowed compression of the cylinder between the plates sufficient to prevent gas leakage at 4 atm. Two acrylic cradles supported the cylinder at either end. Six threaded holes inside the circular groove traversed one plate. External valves (Swagelok, Solon, OH) were screwed into each hole and attached to: a pressure gauge for measuring pressures up to 60 pounds/square inch (4.1 atm); a N2O gas line; a water bath inlet and outlet (see below); sampling port; and plastic tubing for the hydraulic microdrive. The other plate had eight holes drilled through the inner side of the groove; four for ventilation of the animals, two for electrical pass-throughs and two for passage of computer cables. Equipment placed in the chamber included a: power strip; rodent ventilator; small computer fan for circulating gases in the chamber; two pumps for administration of intravenous fluids and drugs; an arterial pressure transducer, with its pressure bag; a head stage for recording extracellular action potentials; two motors and a microdrive for adjusting the spinal recording electrode; and stereotaxic frame (Figure 2–Figure 4). Chamber integrity was tested several times by pressurizing the chamber to 5 atm (absolute) to insure that the seals would hold and that rupture would not occur. Furthermore, we tested the functioning of the various mechanical and electrical systems (ventilator, microdrives, pumps) to detect and solve problems. For example, we found that one of the ventilators we tested (CIV-101, Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH) stopped working when pressures reached approximately 0.5 atm above ambient pressure (e.g., 1.5 atm absolute). The reason for this was unclear, but it underscored the need to test all equipment at the desired working pressures.

Figure 1.

These photographs of the aluminum plates that were used for the ends of the chamber show the sides that faced the inside of the cylindrical chamber (upper panel) and the sides that faced the outside (lower panel). The circular grooves accomodated gaskets inside of the plates that ensured a seal. The main electrical pass-throughs traverse the middle of the plates. Smaller pass-throughs are clustered around the center. The ventilation circuit is seen on the right in the lower panel (note the collapsed reservoir bag). The heating coil for warming the animal, the pressure gauge and the circuit board for the motors are labeled.

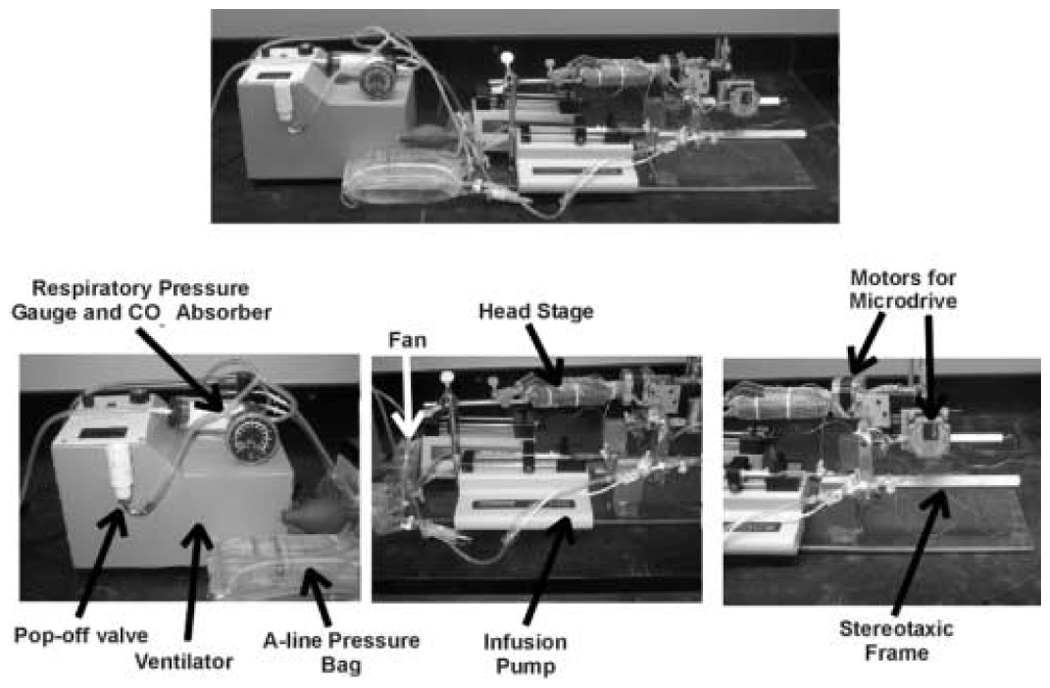

Figure 2.

Equipment placed into the chamber included a ventilator, with pop-off valve, respiratory pressure gauge and CO2 absorber; Arterial line (A-line) pressure bag and transducer; infusion pumps (one is behind the other); fan to circulate chamber gases; the headstage for the neuronal recording; motors for the microdrive (microdrive not shown); and the stereotaxic frame. Note that the stereotaxic frame is attached to an acrylic plate, and that some of the other equipment rests on this plate, thus facilitating the movement of the equipment in and out of the chamber.

Figure 4.

A close-up view of the motor and microdrive assembly reveals the motors rigidly attached to a customized holder that, in turn, was attached to the frame. The motors drove an electrode holder which controlled the hydraulic microdrive.

2.2 Animal Studies

The animal care and use committee at the University of California, Davis approved this study. Adult male rats were housed in a 12 hour lights on, 12 hours lights off temperature controlled room. The rats were anesthetized with isoflurane for placement of a 14 gauge tracheostomy and ventilation with a Harvard rodent ventilator Model 630. A catheter (PE-50) was placed into a carotid artery to monitor blood pressure. A catheter (PE-50) was placed into a jugular vein for fluid and drug administration. A Y port attached to the venous catheter permitted two simultaneous infusions. A laminectomy gave access to the lumbar spinal cord. The arterial catheter was attached to the transducer; the wires of the transducer cable were attached to electrical pass-throughs and then to another cable on the outside. One port on the venous Y-port was attached to a syringe mounted on a pump controlled by computer. The wires of the computer cable from this pump were attached to electrical pass-throughs. A second syringe and infusion pump was attached to the other venous port and pancuronium was infused (approximately 0.1–0.2 mg/kg/hr).

Vertebral clamps were placed on the spine and the rat secured to a stereotaxic frame attached to an acrylic plate (1.27 cm thick, 22.1 cm wide and 68.6 cm long). The beveled sides of the acrylic plate allowed the inserted plate to easily rest on the inside of the chamber. This plate also held the two infusion pumps and the headstage, allowing these to be moved in and out of the chamber as a unit (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The equipment has been placed partly into the chamber. The stereotaxic frame, motors and microdrive protrude from the chamber. The cylinder rests on two acrylic holders. The other aluminum plate is at the back.

A rectal temperature probe was used to measure body temperature, and the cable was attached to an electrical pass-through. Rats become hypothermic during anesthesia unless actively warmed. Normal body temperature was maintained by using water from a bath outside the chamber passed into the chamber; within the chamber, the water passed through coiled copper tubing (≈100cm long, 0.5 cm outside diameter). A “hot-cold” pack (Ortho-Med, Portland, OR) was wrapped around the copper tubing to distribute heat.

Copper tubing was used for the heating system because it would not collapse under the pressures applied in the chamber, but could be easily bent to the desired shape. The heating tubing, the ventilation tubing and the tubing for the hydraulic microdrive were the only tubes that passed between the inside and the outside of the chamber. As the chamber pressure increased, it was possible for the pressure to collapse the tubing, and prevent fluid movement. The use of metal tubing (or some other stiff material) prevented collapse. The tubing for the hydraulic microdrive was made of stiff plastic. Furthermore, this tubing had a small radius (around 0.5 mm), and because of LaPlace’s law (wall tension = pressure × radius), it was able to withstand collapse when the pressure difference across the wall was high. Likewise, the ventilation tubing had small diameter and thick walls. The integrity of these tubes, water bath and hydraulic microdrive were confirmed at pressures exceeding 4 atm absolute, thus ensuring that the systems would work properly.

Vertebral clamps from the stereotaxic frame suspended the rat, thereby allowing the careful placement of the heating device under the rat during final movement of the aluminum plate into position at the end of the chamber. During the course of an experiment the large aluminum plate acted as a heat sink and became warm, and once near normal body temperature was achieved, usually the water bath could be turned off.

Warm agar was poured over the laminectomy wound, and a small section of agar was removed to expose the underlying spinal cord. The aluminum plate was positioned to guide the warming pad under the rat. The animal was then ventilated using the ventilator inside the chamber. The fresh gas flow to the ventilator was passed through the aluminum plate (Figure 5). Exhaust from the ventilator passed through a valve in the plate and then to a scavenging system. Two platinum needle electrodes (Astro-Med, West Warwick, RI) were placed into each hindpaw, with one near the heel and the other in a digit. The ends of the electrodes connected to pass-throughs. The tungsten recording electrode (FHC, Bowdoinham, ME) was advanced into the spinal cord with a hydraulic microdrive (Model 1600, Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA). We listened for local field potentials when touching the ipsilateral hindpaw, to ensure that the electrode was at a lumbar segment receiving sensory input from the hindpaws.

Figure 5.

An O2 and N2O tank supplied gas to two flowmeters. The solid arrows indicate the flow of gas. The N2O/O2 mixture passed directly to the chamber (if stopcock #1 was open) and through a third flowmeter for additional control. Because the chamber was flushed at high flow rates (8–10 liters/min), the third flowmeter (set at 1 liter/min) was needed to prevent excess flow of gas into the isoflurane vaporizer, through stopcock #2 and into the ventilator system. The gas flowing through stopcock #1 was used to flush the chamber when the chamber was closed. The expired gas from the ventilator flowed through a CO2 absorber. There was a respiratory pressure gauge and ‘pop-off’ valve proximal to the CO2 absorber. The pop-off valve prevented excessive pressure build-up and the risk of barotrauma to the lungs. The exhaust passed through the aluminum plate to a system with three stopcocks (#3, #4, #5), a reservoir bag and an exhaust/scavenging system, which prevented buildup of excess pressure in the system. A second N2O tank connected directly to the hyperbaric chamber was used to pressurize the chamber (stopcock #6). Immediately prior to pressurizing, Stopcock 1 was closed to stop the N2O/O2 mixture from flowing into the chamber. Stopcock 2 was turned so that the ventilator obtained its fresh gas from the ambient gas in the chamber (dotted arrow); stopcocks 3 and 4 were turned off to block flow into the reservoir bag and stopcock 5 was turned so that the ventilator exhaust returned to the chamber (dotted arrow). Small tubing (5/16 inch outside diameter, 3/16 inch inside diameter) was used so that the high chamber pressures could be tolerated in the part of the system outside the chamber. Plastic ties secured the tubes to the stopcocks.

The chamber was closed and sealed. The nuts on the six rods were tightened in an alternating manner so that no single side of the cylinder received excessive compression, thus minimizing the chance of fracturing the cylinder. The chamber was flushed with N2O/oxygen (40%:60%) at 8 liters/min. After 60 min of flushing, gas from the chamber contained <1% nitrogen. Immediately before pressurizing the chamber, administration of isoflurane/ N2O/oxygen from outside the chamber to the ventilator was discontinued, and stopcocks on the gas flow circuit were switched so that the ventilator gas flow inlet obtained gas from the ambient gas in the chamber (N2O/O2, ≈60%:40%; see Figure 5). The chamber was pressurized with N2O, achieving 2 ATA (1.5 atm N2O, 0.4–0.5 atm O2) within 2–3 min. Thus, as the isoflurane concentration in the rat decreased, the N2O partial pressure increased. A small fan (wrapped in wire screening to minimize electrical noise) mixed the N2O as it entered the chamber. The exhaled isoflurane exhausted into the chamber was quickly diluted by the 100 L volume of chamber gas.

Single unit activity was recorded using the tungsten microelectrode that was secured to the hydraulic microdrive. The hydraulic tubing from the microdrive was attached to one of the valves in the plate, and the hydraulic tubing from the microdrive motor was attached to the valve on the outside of the plate. The electrode was attached to a head stage (Tucker-Davis, Alachua, FL) wrapped with metal screen grounded to one of the plates. The fiberoptic cable from the head stage was attached to a pass-through in one of the aluminum plates.

The electrode holder could be manipulated remotely using a computer program and control board (A300SMC, Salem Controls, Yadkinville, NC) that controlled the two stepper motors. The wires from the motors were attached to pass-throughs. Corresponding wires on the outside were attached to the control board. The motors were rigidly attached to a custom-made holder bolted to a modified clamp secured to the stereotaxic frame (Figure 4). The motors turned small axles that held the hydraulic microdrive. One motor moved the electrode in the X-plane, the other in the Y-plane, and the microdrive in the Z-plane.

Under normobaric conditions, extracellular action potentials are usually sought using tactile stimulation applied to the freely accessible hindpaw. In the present experiment we applied electrical search stimuli via the needle electrodes in the hindpaw. The electrode was advanced into the spinal cord using the hydraulic microdrive in 5 micron steps while we applied electrical stimuli to the hindpaw. The stimulus was a short burst (250–500 ms) of a 100 Hz pulse at 30mA. Once we found an action potential and maximized the signal-to-noise ratio, we investigated the neuronal response to characterize its firing pattern. We applied a 2 sec, 100 Hz stimulus at 30mA (Model NS252, Fisher-Paykel, Auckland, New Zealand) to a hindpaw to determine whether the neuron responded to the noxious stimulus. We also applied a “windup” stimulus, consisting of a series of 20 pulses (0.1 ms duration, 30–80 mA, 1Hz) and we sometimes used a Pulsar6i stimulator (FHC, Bowdoinham, ME) at 30–80V for delivery of the windup stimuli. We determined the threshold for neuronal firing by increasing the current of single pulses and noting the current which produced an action potential in the C-fiber latency range (100–400ms) on at least 50% of trials. The windup stimulus was > 2–3 times the threshold.

The N2O/O2 mixture was sampled by opening a valve and withdrawing ≈50 ml into a glass syringe. The gas sample was injected into an anesthetic agent analyzer (Rascal II, Ohmeda, Salt Lake City, UT). The N2O concentration, multiplied by the total pressure in the chamber, provided the N2O partial pressure. During data collection we usually maintained N2O partial pressure at 1.5 atm or greater. In our laboratory the MAC for N2O in rats is 1.7–1.9 atm (Antognini, Lewis et al., 1994;Leduc, Atherley et al., 2006). Thus we used partial pressures that would assure unconsciousness (Dwyer, Bennett et al., 1992) but would permit robust evoked responses to noxious stimulation.

EEG activity, blood pressure, and action potentials were recorded to computer using Chart5 software (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO). EEG activity was recorded from small stainless steel screws placed into the skull before placing each rat into the chamber. The EEG wires were attached to pass-through wires, and then to an amplifier (Bioamp, ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO). At the end of the procedures, the chamber was flushed with N2O while depressurizing, followed by initiation of isoflurane anesthesia. The chamber was opened and the animal euthanized with intravenous potassium chloride.

2.3 Data Analysis

Data are presented as mean and standard error of the mean (SEM). The number of action potentials before the 100 Hz stimulation was compared to the number in the 1 min period after stimulation using a paired t-test. Windup was expressed as the number of action potentials occurring in the A-fiber (0–100 ms) C-fiber (100–400 ms) and combined C-fiber + afterdischarge (100–1000 ms) ranges after each of the twenty stimuli. The power spectrum of the EEG activity was calculated using the spectrum function of the Chart5 program.

3. Results

The hyperbaric chamber maintained pressures of 4 atm (absolute) without any significant leaking. Anesthesia appeared to be adequate in these rats. When the effects of pancuronium were allowed to dissipate, spontaneous organized movement did not occur, aside from twitching of the whiskers, consistent with what others have reported (Gonsowski and Eger, 1994). Although most rats tolerated the recording conditions and hyperbaric pressures, several rats died suddenly. These deaths were most likely due to a blockage of the tracheal tube, as we have experienced similar blockage in rats during experiments at normobaric pressures. However, in the setting of a hyperbaric chamber, death occurred before the chamber could be depressurized and the blockage removed.

We recorded responses of 18 neurons from 18 rats during N2O anesthesia at 1.5 atm. The recording depth was 776 ± 106 microns, which corresponds to the deep dorsal horn and intermediate lamina of the spinal cord. The signal-to-noise ratio was usually large, in the range of 5-to-1 and 10-to-1. Mean arterial pressure was 152 ± 5 mmHg, and the temperature was 37.6 ± 0.2 C. In 10 rats we determined responses to the 100 Hz stimulus (Fig. 6, upper panel shows an individual response). In the other eight rats we determined responses to the wind-up stimulus. The neuronal response during the short 2 sec 100 Hz stimulus was obscured by the electrical artifact produced by the stimulator. Summary data are shown in Figure 6 (lower panel). Most neurons had no spontaneous activity, although a few had spontaneous activity. The number of action potentials significantly increased after application of the stimulus. The responses were typically high immediately after stimulation and diminished over the ensuing 20–60 sec. Bursting was occasionally observed.

Figure 6.

The upper panel shows an individual example of neuronal response to the 2 second 100 Hz stimulus (arrow). This neuron had little or no spontaneous activity, but demonstrated significant activity after electrical stimulation (80mA) was applied to the receptive field on the hindpaw. The N2O partial pressure was 1.5 atm. The summary data for responses to 100 Hz stimulus (n=10) are shown in the lower panel. Spontaneous activity was low, but stimulation of the receptive filed on the hindpaw evoked significant neuronal activity. * p < 0.01 compared to the pre-stimulus spontaneous activity. The N2O partial pressure was 1.5 atm during these experiments.

The wind-up stimuli progressively increased the number of action potentials after each successive stimulus (Fig. 7). Figure 8 provides an example of EEG activity. The power spectrum shows that the lower frequencies contain most of the EEG power.

Figure 7.

The upper panel shows an individual example of windup responses to a 1 Hz stimulus. This neuron responded to the 1 Hz stimulus (20 pulses, 30 volts) with increasing number of action potentials, i.e., wind-up. The lower panel shows summary data for neuronal responses (n=8) to repetitive electrical stimulation (20 pulses at 1 Hz). The number of action potentials progressively increased with each successive stimulus applied to the receptive field on the hindpaw. The data are shown for the A-fiber (latency 0–100 ms), C-fiber (100–400 ms) and combined C-fiber + afterdischarge (100–1000 ms) ranges. The N2O partial pressure was 1.5 atm.

Figure 8.

The upper tracing shows an example of electroencephalographic (EEG) activity recorded when the N2O partial pressure was 2 atm. The panel below the raw EEG tracing shows the corresponding power spectrum that was generated using a Fourier transform. Most of the EEG power was concentrated in lower frequencies, i.e., below 5 Hz.

4. Discussion

The main purpose of the present study was to show that spinal neuronal responses could be recorded during N2O anesthesia. While the complex requirements of recording in hyperbaric conditions do not support the routine use of N2O as an alternative to other anesthetic techniques, an investigator may be interested in the specific effects of N2O. The weak potency of N2O, however, limits its usefulness and hampers its investigation. A hyperbaric chamber as presently described permits determination of N2O anesthetic effects on neurophysiological activity in intact animals in the absence of other confounding anesthetics. We were able to record action potentials and showed that, during N2O anesthesia, spinal neurons responded to noxious stimulation. This included increased evoked activity in response to a 100 Hz stimulus as well as neuronal windup (Figure 6 and Figure 7). Although some rats died suddenly (presumably because of tracheal blockage) most rats tolerated the hyperbaric conditions. In addition, EEG activity was maintained during N2O anesthesia. Because N2O acts primarily at the NMDA receptor, and the anatomic sites of action of N2O are known (Sawamura, Kingery et al., 2000), the use of N2O as the sole anesthetic facilitates data interpretation.

Although in the present study we focused on N2O anesthesia and its effect on nociceptive processing, this hyperbaric chamber could be used for other experimental purposes. For example, human patients occasionally require hyperbaric oxygen treatment for various diseases (such as wound infections and carbon monoxide poisoning). Hyperbaric oxygen appears to diminish chronic pain (Kiralp, Yildiz et al., 2004), although its acute effects are unknown. Thus, our technique could be used to explore the poorly understood effects of hyperbaric oxygen on nociceptive processing. Lastly, the hyperbaric chamber could be used to investigate the EEG actions of N2O and xenon, and along with simple modification to permit recording of single unit activities in brain, might help to elucidate the mechanisms of the EEG effects of these drugs.

4.1 Safety Issues

Several safety issues apply to the use of a hyperbaric chamber. Rupture of the chamber can cause serious injury. Thus working pressures must remain well below the burst strength of the chamber. The burst strength of the chamber is directly related to the material being used, the wall thickness and Laplace’s law. A thicker wall and smaller chamber radius permits the safe use of higher pressures. Data from the manufacturer suggests that a chamber with 1.27 cm wall thickness and inside diameter 33 cm should withstand pressures of 20 atm, well above those needed during N2O anesthesia.

In practice, pressure limits are assessed by determining whether the chamber safely and completely (without leaks) contains a pressure well beyond that needed for the specific experiment to be performed. To accomplish this safely, the chamber is sealed and filled with water. The chamber then is pressurized to a pressure 50% greater than the greatest working pressure to be applied. Because water is not compressible, rupture would produce evidence of a leak but the leak would not be explosive. We used aluminum plates because aluminum is easy to machine and strong enough to withstand the maximum pressures to be used. We initially used acrylic plates but pressures of 2–3 atm caused bulging and rupture.

Because N2O supports combustion, its use in a hyperbaric chamber increases the risk of a fire. The ensuing rapid increase in pressure could lead to an explosive bursting of the chamber. Hence, to minimize such a catastrophic outcome, any electric equipment used in the hyperbaric chamber must be inspected to ensure there are no bare wires or other faulty electrical connections. In addition, using the least amount of electrical equipment is advised. We emphasize that we tested the safety limits of the chamber within pressure ranges that we intended to use. If an investigator chooses to use higher pressures, he or she must carefully test their system under controlled conditions similar to those needed for their particular experiment to insure that rupture and fire will not occur.

4.2 Neurophysiological recordings

Determination of recording depth is often accomplished by making a lesion at the recording site, usually with direct current. Various factors prevented us of this approach. First, because of the fire hazard, we wanted to minimize the electric current passing through the chamber. Secondly, and perhaps most importantly, attaching additional cables to the recording electrode might introduce a source of electrical noise that would not be correctable once the chamber was closed and at pressure.

One limitation to the use of a hyperbaric chamber is the inability to search for single units and characterize receptive field properties, as is normally performed, e.g., by touching the hindpaw while advancing the recording electrode into the spinal dorsal horn. This technique also permits determination of receptive field size and the appropriate placement of a stimulus in the middle of the receptive field. A motor-controlled device could be constructed that would permit the investigator to indirectly touch the hindpaw and thereby assess the receptive field and neuronal responses to non-noxious and noxious mechanical stimulation. For reasons of simplicity, we decided to use an electrical search stimulus, as has been done previously in hyperbaric chambers (Smallman, Dickenson et al., 1989). Thus, we maximized the chance of finding a suitable neuron by placing electrodes spanning the entire paw of each hindlimb. Furthermore, the use of C-fiber strength electrical current (instead of tactile stimuli), while increasing our ability to find neuronal activity, might lead to sensitization. Nonetheless, electrical stimuli are well accepted methods to assess spinal nociceptive processing.

In summary, we have described a hyperbaric chamber that is readily constructed and uses immediately available materials. The equipment that normally would be used for recording extracellular action potentials can be easily modified for use in the chamber. We found that, at N2O partial pressures close to those needed to produce immobility, spinal neuronal responses to electrical stimulation of the hindpaw could be recorded. EEG activity was also recorded under these hyperbaric conditions. This hyperbaric chamber could be used to explore the anesthetic actions of weak anesthetics, such as N2O and xenon, as well as the effects of hyperbaric oxygen on nociceptive processing.

TABLE 1.

APPROXIMATE TIMES NEEDED FOR PROCEDURES

| PROCEDURE | TIME |

|---|---|

| Anesthetic induction | 10 min |

| Tracheostomy, jugular catheter, carotid catheter | 20 min |

| Laminectomy | 20 min |

| Transfer to chamber, secure to stereotaxic frame | 10 min |

| Insert microelectrode, hindpaw needles, optimize signal-to-noise | 30 min |

| Close chamber, flush with N2O and oxygen | 70 min |

| Pressurize with N2O, eliminate isoflurane, search for neuron | 45–120 min |

| Test neuronal responses | 15–20 min |

| Change N2O partial pressure, equilibrate | 15 min |

| Test neuronal responses | 15–20 min |

| Change N2O partial pressure, equilibrate | 15 min |

| Test neuronal responses | 15–20 min |

| Depressurize chamber, add isoflurane, open chamber | 5 min |

TABLE 2.

PARTS LIST

| PART | COMPANY | PART NUMBER |

|---|---|---|

| Water Bath | Boekel Scientific, Inc Feasterville, PA | Model GD120L |

| Valves | Swagelok, Solon OH | SS-1RM4-S4-A SS-0RM2-52-A SS-43M4-A |

| Head stage (with fiberoptic cable) | Tucker-Davis, Alachua, FL | - - - - - |

| Amplifiers | Tucker-Davis, Alachua, FL | RA16 |

| Oscilloscope | Tektronix, Beaverton, OR | Model 2211 |

| Hydraulic Microdrive | Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA | Model 630 |

| Pass-through (with 12 wires) | Conax Technologies, Buffalo, NY | 1 inch |

| Pressure Gauge | Ametek, US Gauge, Feasterville, PA | - - - - - |

| Ventilator | Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA | Model 687 |

| Motor | Oriental Motor Co Torrance, CA | Vexta PK264M-01A |

| IV Pump (with cable) | Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL | Model 101 |

| Pressure Bag, Transducer | Medex, Dublin, OH | MX-4705 |

| Acrylic cylinder | Spartech-Townsend, Pleasant Hill, IA | 1.27 cm (0.5 inch) |

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grants NIH GM57970 (UCD), GM61283 (UCD) and 1POGM47818 (UCSF).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- Antognini JF, Lewis BK, Reitan JA. Hypothermia minimally decreases nitrous oxide anesthetic requirements. Anesth. Analg. 1994;79:980–982. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199411000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong RH, Wagman IH. Block of afferent impulses in the dorsal horn of monkey. A possible mechanism of anesthesia. Exp. Neurol. 1968;20:352–358. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(68)90078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa SL, Dickinson R, Lieb WR, Franks NP. Contrasting synaptic actions of the inhalational general anesthetics isoflurane and xenon. ANESTHESIOLOGY. 2000;92:1055–1066. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200004000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer R, Bennett HL, Eger EI, Heilbron D. Effects of isoflurane and nitrous oxide in subanesthetic concentrations on memory and responsiveness in volunteers. ANESTHESIOLOGY. 1992;77:888–898. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199211000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eger EI, Liao M, Laster MJ, Won A, Popovich J, Raines DE, Solt K, Dutton RC, Cobos FV, Sonner JM. Contrasting roles of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor in the production of immobilization by conventional and aromatic anesthetics. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:1397–1406. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000219019.91281.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonsowski CT, Eger EI. Nitrous oxide minimum alveolar anesthetic concentration in rats is greater than previously reported. Anesth. Analg. 1994;79:710–712. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199410000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K, Harris RA. The anesthetic mechanism of urethane: the effects on neurotransmitter-gated ion channels. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:313–318. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200202000-00015. table. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Todorovic SM, Mennerick S, Powell S, Dikranian K, Benshoff N, Zorumski CF, Olney JW. Nitrous oxide (laughing gas) is an NMDA antagonist, neuroprotectant and neurotoxin [see comments] Nat. Med. 1998;4:460–463. doi: 10.1038/nm0498-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinks SL, Martin JT, Carstens E, Jung SW, Antognini JF. Peri-MAC depression of a nociceptive withdrawal reflex is accompanied by reduced dorsal horn activity with halothane but not isoflurane. ANESTHESIOLOGY. 2003;98:1128–1138. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200305000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiralp MZ, Yildiz S, Vural D, Keskin I, Ay H, Dursun H. Effectiveness of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the treatment of complex regional pain syndrome. J Int. Med. Res. 2004;32:258–262. doi: 10.1177/147323000403200304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasowski MD, Harrison NL. General anaesthetic actions on ligand-gated ion channels. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 1999;55:1278–1303. doi: 10.1007/s000180050371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leduc ML, Atherley R, Jinks SL, Antognini JF. Nitrous oxide depresses electroencephalographic responses to repetitive noxious stimulation in the rat. Br. J Anaesth. 2006;96:216–221. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawamura S, Kingery WS, Davies MF, Agashe GS, Clark JD, Kobilka BK, Hashimoto T, Maze M. Antinociceptive action of nitrous oxide is mediated by stimulation of noradrenergic neurons in the brainstem and activation of [alpha]2B adrenoceptors. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:9242–9251. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09242.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smallman K, Dickenson AH, Halsey MJ. Electrophysiological studies on the effects of opiates on dorsal horn nociceptive neurones at 51 atmospheres absolute. Pain. 1989;38:57–64. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90073-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]