Abstract

The nuclear factor Acinus has been suggested to mediate apoptotic chromatin condensation after caspase cleavage. However, this role has been challenged by recent observations suggesting a contribution of Acinus in apoptotic internucleosomal DNA cleavage. We report here that AAC-11, a survival protein whose expression prevents apoptosis that occurs on deprivation of growth factors, physiologically binds to Acinus and prevents Acinus-mediated DNA fragmentation. AAC-11 was able to protect Acinus from caspase-3 cleavage in vivo and in vitro, thus interfering with its biological function. Interestingly, AAC-11 depletion markedly increased cellular sensitivity to anticancer drugs, whereas its expression interfered with drug-induced cell death. AAC-11 possesses a leucine-zipper domain that dictates, upon oligomerization, its interaction with Acinus as well as the antiapoptotic effect of AAC-11 on drug-induced cell death. A cell permeable peptide that mimics the leucine-zipper subdomain of AAC-11, thus preventing its oligomerization, inhibited the AAC-11–Acinus complex formation and potentiated drug-mediated apoptosis in cancer cells. Our results, therefore, show that targeting AAC-11 might be a potent strategy for cancer treatment by sensitization of tumour cells to chemotherapeutic drugs.

Keywords: AAC-11, Acinus, cell death, DNA fragmentation, peptide

Introduction

Apoptosis is a multistep, multipathway cell-death programme that plays a variety of crucial roles in multicellular organisms, allowing the elimination of unwanted cells without affecting the viability of adjacent cells, regulating healthy development and protecting against disease. It has been shown in various tumours that dysregulation of apoptosis was closely correlated with oncogenesis and malignant phenotype of tumour cells (Johnstone et al, 2002). Apoptosis also contributes to the antitumour activity of most chemotherapeutic drugs, and it is now known that apoptosis resistance has a critical function in the efficiency of chemotherapy (Igney and Krammer, 2002; Johnstone et al, 2002). Therefore, the unfolding of the complex pathways involved in apoptosis signalling has stimulated intensive efforts to restore apoptosis in cancer cells for therapeutic purpose. At the molecular level, apoptosis relies on the timing activation of caspases, a group of cysteine proteases involved in both the signalling and the execution phase of cell death (Alnemri et al, 1996). Cleavage of specific target proteins by activated caspases leads to the characteristic morphological and biochemical markers of apoptotic cell death, including cell and nuclear shrinkage, DNA cleavage into nucleosomal fragments, chromatin aggregation and apoptotic body formation. The expression of genes that regulate apoptotic cell death has an important function in determining the sensitivity of tumour cells to chemotherapy. For instance, the pro-survival Bcl2 family members, such as Bcl-xL and Bcl2, are overexpressed in several malignancies and promote tumour progression and resistance to therapy (Cory and Adams, 2002). Among the antiapoptotic proteins is AAC-11 (antiapoptosis clone 11) (Tewari et al, 1997). AAC-11, also called Api5 or FIF (Van den Berghe et al, 2000; Morris et al, 2006), is a poorly studied nuclear protein whose expression has been shown to prevent apoptosis after growth factor deprivation (Tewari et al, 1997; Kim et al, 2000). How AAC-11 prevents apoptosis is currently unknown, but a recent study indicates that its antiapoptotic action seems to be mediated, at least in part, by the suppression of the transcription factor E2F1-induced apoptosis (Morris et al, 2006). The AAC-11 gene has been shown to be highly expressed in multiple cancer cell lines as well as in some metastatic lymph node tissues and in B-cell chronic lymphoid leukemia (Tewari et al, 1997; Kim et al, 2000; Van den Berghe et al, 2000; Sasaki et al, 2001; Clegg et al, 2003; Morris et al, 2006; Krejci et al, 2007). AAC-11 expression seems to confer a poor outcome in subgroups of patients with non-small cell lung carcinoma, whereas its depletion seems to be tumour cell lethal under condition of low-serum stress (Sasaki et al, 2001; Krejci et al, 2007). Interestingly, AAC-11 overexpression has been reported to promote both cervical cancer cells growth and invasiveness (Kim et al, 2000). Combined, these observations implicate AAC-11 as a putative metastatic oncogene and suggest that AAC-11 could constitute a therapeutic target in cancer.

In this study, we show that AAC-11 modulates cellular sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs. AAC-11 interacts with, and negatively regulates Acinus, a protein involved in apoptotic DNA fragmentation. AAC-11 can form homo-oligomers, through a leucine-zipper (LZ) motif, and oligomerization-deficient mutants of AAC-11 can no longer inhibit apoptosis nor interact with Acinus. Finally, a cell permeable peptide that mimics the LZ subdomain of AAC-11 was able to prevent its oligomerization, inhibiting AAC-11 interaction with Acinus and blocking its antiapoptotic properties. Our data and others (Morris et al, 2006) suggest, therefore, that AAC-11 may be a potential therapeutic target and that manipulation of the antiapoptotic pathways maintained by AAC-11, through targeting the oligomerization state of the LZ of AAC-11, may enhance drug-mediated cancer therapy.

Results

Down regulation of AAC-11 increases sensitivity to anticancer drugs

To address the role of AAC-11 in chemotherapeutic drugs-mediated apoptosis, we stably transfected U2OS cells with two tetracycline-inducible pSingle-tTS-shRNA constructs (pS AAC-11 #1 and #2), expressing two distinct shRNA molecules directed against AAC-11. As seen in Figure 1A, a significant reduction of AAC-11 protein level was detected after 48 h of induction of RNA interference with doxycycline for both pS AAC-11 #1 and #2 clones compared with a control clone containing the empty vector.

Figure 1.

Deregulation of AAC-11 increases drug-induced cell death. (A) U2OS cells stably transfected with empty vector (pSingle-tTS) or the AAC-11 shRNA expression constructs (pS AAC-11 #1 and pS AAC-11 #2) were cultured in the presence or absence of doxycycline (1 μg/ml) for 48 h. Cells were lysed and the lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (B) U2OS control or AAC-11 shRNA-stable clones were cultured in the presence or absence of doxycycline for 48 h. Cells were exposed to cisplatin (CDDP, 20 μM), etoposide (ETO, 20 μM), camptothecin (CPT, 10 μM), paclitaxel (PTX, 1 nM) or 5-fluorouracil (5-FU 1 mM) for 16 h or left untreated. The percentage of apoptotic cells was assessed by flow cytometry. Each bar represents the mean±s.d. from three independent experiments. (C) The indicated cell lines were transfected with mock or AAC-11 specific siRNAs. After 48 h, cells were lysed and the lysates immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (D) The indicated cell lines were transfected with mock or AAC-11 specific siRNAs. After 48 h, cells were treated as in (B) and the percentages of apoptotic cells were determined as in (B). (E) AAC-11 expression modulates drug-induced cell death. U2OS clones stably expressing T7-tagged AAC-11 or T7-tagged AAC-11 LL/RR were treated as in (B) and the percentages of apoptotic cells were determined as in (B). Expression of T7-tagged constructs was determined by immunoblotting with an anti-T7 antibody. (F) Jurkat or MCF7/Fas/casp3 cells were transfected with either AAC-11 or AAC-11 LL/RR together with a GFP-reporter plasmid. At 36 h after transfection, the cells were exposed to etoposide (ETO, 20 μM) for 16 h or treated with anti-Fas antibody (0.5 μg/ml) plus cycloheximide for 4 h or left untreated and percentages of apoptotic cells were determined as in (B).

We next treated the different clones with cisplatin, etoposide, camptothecin, paclitaxel or 5-fluorouracil and evaluated cell death. As shown in Figure 1B, silencing of AAC-11 resulted in a marked increase in etoposide- and camptothecin-induced apoptosis, whereas no difference was noted for cisplatin-, paclitaxel- or 5-fluorouracil-induced cell death. The apoptotic effect of AAC-11 down regulation was also illustrated by a significant increase in caspase-3/7 activity over control cells after etoposide or camptothecin treatment (Supplementary Figure S1). Of note, no differences in growth or cell-cycle phenotypes were observed in AAC-11-depleted cells compared with the control cells (not shown). We further assessed the functional consequences of inhibiting the expression of AAC-11 in various cellular contexts using both cancer cells (HeLa, A549 and Molt-4 cell lines) and normal cells (a B-lymphoblastoid cell line (LCL), generated by infection of normal human B cells with Epstein–Barr virus, and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs)). All these cells express substantial amounts of AAC-11 (Figure 1C). Interestingly, knockdown of AAC-11 by two distinct siRNA heteroduplexes derived from the above-described shRNAs resulted in a specific increase in sensitivity to etoposide and camptothecin for all the tested cells (Figure 1D). Thus, these results suggest that AAC-11 might be associated with cellular chemosensitivity. A recent report indicated that increased expression of AAC-11 protected primary liver cells to UV-induced apoptosis (Wang et al, 2008). We, therefore, next sought to determine whether increases of AAC-11 protein levels might alter cell death sensitivity against chemotherapeutic reagents. AAC-11 possess a LZ domain and mutation of two conserved leucines, at positions 384 and 391, within the LZ domain, to arginines has been shown to abrogate the protection of AAC-11 to growth factor withdrawal (Tewari et al, 1997). This indicates that the LZ domain might be important for the antiapoptotic function of AAC-11. Thus, we generated U2OS cell lines that stably expressed T7-tagged versions of either the wild-type AAC-11 or the leucines to arginines mutant (LL/RR mutant). Both forms were expressed at similar levels (Figure 1E). As shown in Figure 1E, overexpression of wild-type AAC-11, but not the LL/RR mutant, significantly decreased etoposide- or camptothecin-induced apoptosis, whereas in agreement with the previous experiments, cisplatin-, paclitaxel- or 5-fluorouracil-induced cell death was not affected. Here again, no difference in growth or cell-cycle phenotypes were observed in cells expressing AAC-11 compared with the control cells (not shown). Interestingly, expression of AAC-11 did not alter etoposide- or camptothecin-induced reduction of mitochondrial potential, cytochrome c release from mitochondrial to cytosol or effector caspase activation (Supplementary Figure S2). The same data were obtained when HeLa, A549 or Molt-4 cells were used (not showed). These results suggest that AAC-11 did not prevent caspases activation but rather modulates drug-induced cell death at a level below caspase-3. Finally, AAC-11 expression was able to negatively modulate death receptor-mediated apoptosis both in type I (MCF7/Fas/casp3) (Scaffidi et al, 1998) and type II cells (Jurkat). Indeed, as shown in Figure 1F, apoptosis induced by the agonist Fas antibody was considerably reduced in the AAC-11 expressing cells compared with AAC-11 LL/RR expressing cells or control cells. As AAC-11 antiapoptotic effects were irrelevant to the cell type, our results suggest that the mitochondrial amplification loop did not affect AAC-11 regulation of Fas-induced apoptosis.

AAC-11 interacts with Acinus

Using a Drosophila-based model system, Morris et al have recently proposed a crosstalk between the AAC-11 and E2F1 signalling pathways (Morris et al, 2006). In this model, AAC-11 was found to suppress E2F1-dependent apoptosis, without blocking E2F1 general transcriptional activity (Morris et al, 2006). Interestingly, the E2F1-AAC-11 interaction seemed to be conserved from flies to human (Morris et al, 2006). As flies, in contrast to mammals, have only one activator E2F gene, one can suspect that the E2F, and by extension, the AAC-11 signalling pathways might be easier to dissect in a Drosophila based system. Moreover, fly AAC-11 is highly similar to its human counterpart (Supplementary Figure S3). To gain access into the AAC-11 signalling pathway, we used fly AAC-11 as a bait in a yeast two-hybrid assay to screen a highly complex, random primed Drosophila embryo cDNA library. By this approach, multiple overlapping fragments of the putative apoptotic CG10473 gene were identified, allowing us to narrow down the precise interaction domain of CG10473 to amino acids 298–390 (Figure 2A). CG10473 is the ortholog of human Acinus (Supplementary Figure S4), a nuclear protein that has been described to mediate apoptotic chromatin condensation (Sahara et al, 1999). Acinus is expressed in three main isoforms, termed Acinus-L, Acinus-S and Acinus-S', and containing, respectively, 1341, 583 and 565 residues (Sahara et al, 1999). Because of its role in the apoptotic process, we decided to study the physiological role of the AAC-11–Acinus interaction in human. To determine whether AAC-11 binds to Acinus in mammalian cells, we transfected 293T cells with expression vectors encoding T7-tagged AAC-11 and Flag-tagged Acinus-L. As shown in Figure 2B, AAC-11 was detectable in Flag immunoprecipitates. To confirm the AAC-11–Acinus interaction at the endogenous level, endogenous Acinus was immunoprecipitated from HeLa whole cell extracts using an anti-Acinus antibody. As shown in Figure 2C, AAC-11 was efficiently co-immunoprecipitated with Acinus, but not with a control antibody, indicating that endogenous AAC-11 and Acinus interact physiologically. Of note, etoposide treatment for 2 h, a period during which no significant Acinus cleavage was noted, did not seem to modulate AAC-11–Acinus interaction (Figure 2C). Alignment of CG10473 with Acinus indicates that the AAC-11 interaction domain of CG10473 corresponds to amino acids 840–918 of Acinus (Supplementary Figure S4). To confirm whether the interaction we detected by yeast two-hybrid analysis could be extended to Acinus, T7-tagged AAC-11 was expressed in 293T cells together with several Flag-tagged deletions mutants of Acinus. In agreement with the two hybrid data, AAC-11 co-precipitated specifically with Acinus-L, Acinus-S and Acinus (840–918), but not Acinus (1–840) (Figure 2D). In vitro binding between a purified AAC-11-GST fusion protein and 35S labelled Acinus-S indicated a direct interaction (Supplementary Figure S5). To extend the characterization of the AAC-11–Acinus interaction, we expressed T7-tagged Acinus-S with several forms of truncated Flag-tagged AAC-11. As shown in Figure 2E, a COOH deletion of AAC-11 containing the LZ domain (amino acids 1–400) was still able to co-precipitate Acinus-S, whereas deletion of this domain abrogated the AAC-11–Acinus interaction. This suggests that the LZ region of AAC-11 is necessary for the interaction with Acinus. To assess whether the LZ domain of AAC-11 is sufficient for interaction with Acinus, we expressed Flag-tagged Acinus-S together with GFP-tagged AAC-11 (361–400) (primarily the LZ domain) either untouched or mutated at the two leucines (AAC-11 (361–400) LL/RR). As shown in Figure 2F, Acinus-S was indeed able to interact with AAC-11 (361–400). However, substitution of the two leucines with arginines totally abolished the interaction with Acinus. Combined, these results indicate that the LZ domain of AAC-11 is necessary and sufficient for interaction with Acinus. Indirect immunofluorescence studies using HeLa cells transfected or not with GFP-tagged AAC-11 or AAC-11 LL/RR indicated that AAC-11–Acinus interaction takes place in the nucleus, as considerable overlaps of the nuclear speckles corresponding to endogenous Acinus and GFP-AAC-11, but not GFP-AAC-11 LL/RR, were observed (Figure 2G). Of note, no relocalization of endogenous Acinus was detected after AAC-11 expression. As the LZ domain is involved in oligomerization, we investigated the possibility that this motif could form homo-oligomers. GFP-tagged AAC-11 (361–400) or GFP-AAC-11 (361–400) LL/RR were co-expressed with a vector encoding GST-tagged AAC-11 (361–400). Immunoprecipitation analysis indicate that wild-type LZ can form oligomers through self-association, whereas the LL/RR mutant can no longer oligomerize (Figure 2H). Taken together, these data suggest that a functional LZ domain is required for assembly of the AAC-11–Acinus complex.

Figure 2.

Physical interaction between Acinus and the LZ domain of AAC-11. (A) Selection of Drosophila Acinus (CG10473) fragments that interact with Drosophila AAC-11 in the yeast-two-hybrid system. Black lines indicate the fragments of CG10473 that interact with Drosophila AAC-11. Domains of CG10473 from Superfamily (supfam.org) SSF54928 (RBD) and SSF69060 (ARPC3) are indicated. The minimal interacting domain is from aa 298 to aa 390. (*) indicates a fragment identified two times in the screen. (B) 293T cells were cotransfected with T7-AAC-11 together with Flag-tagged Acinus. Cell lysates were subjected to anti-Flag immunoprecipitation (IP) followed by immunoblotting (IB) with anti-T7. In these and all the following experiments, the expression of proteins under investigation was determined by direct immunoblotting. (C) Endogenous AAC-11 interacts with endogenous Acinus. Cell extracts (500 μg of proteins in 0.3 ml) derived from HeLa cells exposed or not to etoposide (20 μM, 2 h) were subject to immunoprecipitation with a control antibody or anti-Acinus antibody followed by immunoblotting with anti-AAC-11 antibody. (D) AAC-11 interacts with a domain encompassing residues 840 to 918 of Acinus. 293T cells were cotransfected with T7-AAC-11 together with the indicated Acinus Flag-tagged constructs. Immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis was performed as in (B). (E, F) The LZ domain of AAC-11 mediates its interaction with Acinus. (E) 293T cells were cotransfected with T7-Acinus-S together with the indicated AAC-11 Flag-tagged constructs. Immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis was performed as in (B). (F) 293T cells were cotransfected with Flag-Acinus-S together with the indicated AAC-11 LZ GFP-tagged constructs. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-GFP and blotted with anti-Flag. (G) Nuclear colocalization of endogenous Acinus and GFP-AAC-11. HeLa cells either nontransfected (control) or transfected with GFP-AAC-11 or GFP-AAC-11 LL/RR were fixed in paraformaldehyde and immunolabelled with anti-Acinus antibody (red) and analysed by confocal microscopy. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. (H) The LZ of AAC-11 can oligomerize. 293T cells were cotransfected with GST-tagged AAC-11 LZ together with the indicated AAC-11 LZ GFP-tagged constructs. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-GFP and blotted with anti-GST.

AAC-11 interaction prevents caspase-3 mediated Acinus cleavage

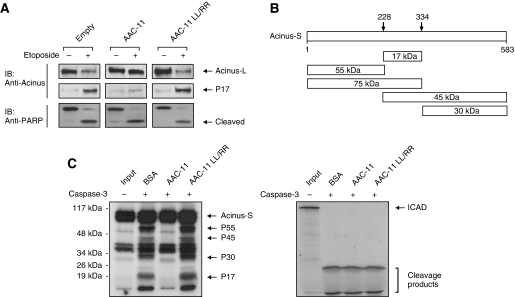

Acinus is cleaved by caspase-3 during apoptosis, producing a p17 active fragment that has been reported to mediate chromatin condensation in the nucleus (Sahara et al, 1999). As our results suggest that AAC-11 can negatively modulate drug-induced apoptosis without preventing effector caspases activation, and that AAC-11 interacts with Acinus, we tested the possibility that binding of AAC-11 could prevent degradation of Acinus by caspase-3 during apoptosis. We first examined the cleavage status of Acinus after drug treatment in U2OS cell lines stably expressing either wild-type AAC-11 or the leucines to arginines mutant (LL/RR mutant). The cells were treated with 20 μM etoposide for 12 h, lysed and the lysates analysed by western blotting using an anti-Acinus antibody that recognizes the full length as well as the p17 forms. As seen in Figure 3A, treatment of the control cells generated a substantial amount of the p17 band, concomitant with a strong reduction of the full-length Acinus. Drug treatment also induced PARP cleavage, indicating caspase-3 activation. Interestingly, expression of AAC-11, but not the LL/RR mutant, strongly prevented p17 generation, as well as Acinus cleavage, compared with the control cells (Figure 3A). On the other hand, PARP cleavage was still observed, confirming our earlier observations that AAC-11 expression does not prevent caspases activation. Combined, these data suggest that AAC-11 might inhibit Acinus apoptotic cleavage and this property might stem from its binding to Acinus. Acinus-S contains several caspase cleavage sites (Sahara et al, 1999), so its apoptotic cleavage can generate several fragments (Figure 3B). To determine whether the observed effect of AAC-11 on Acinus processing was direct, we designed an in vitro Acinus activation system. For that purpose, we incubated recombinant, active caspase-3 with in vitro translated Acinus-S that has been pre-incubated with BSA, recombinant AAC-11 or recombinant AAC-11 LL/RR. Interestingly, caspase-3 was able to process Acinus that has been pre-incubated with BSA or AAC-11 LL/RR (Figure 3C, left panel), with generation of the expected fragments, including p17. However, very little processing was observed when Acinus-S was pre-incubated with wild-type AAC-11. This effect cannot be due to a direct inhibition of caspase-3 by AAC-11, as AAC-11 did not prevent a complete cleavage of ICAD (inhibitor of caspase-activated DNAse), a known caspase-3 substrate (Figure 3C, right panel). Finally, in agreement with the reduced Acinus apoptotic cleavage when AAC-11 was overexpressed (Figure 3A), depletion of AAC-11 in U2OS cells markedly augmented apoptotic Acinus degradation (Figure 4H). The same results were obtained when HeLa, A549 or Molt-4 cells were used (not showed). Therefore, our results strongly suggest that AAC-11, on binding, can block Acinus apoptotic processing by caspase-3 both in vivo and in vitro.

Figure 3.

AAC-11 modulates Acinus apoptotic cleavage. (A) U2OS clones stably expressing T7-tagged AAC-11 or T7-tagged AAC-11 LL/RR were exposed to etoposide (20 μM) for 12 h or left untreated. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (B) Schematic representation of Acinus-S. The putative caspase-3 cleavage sites, as well as the corresponding fragments with theoretical molecular weights are represented. (C) 35S-labelled Acinus-S (left panel) or ICAD (right panel) were pre-incubated with recombinant AAC-11, AAC-11 LL/RR or with BSA for 2 h at 4°C. Active caspase-3 was then added and the reaction mixtures were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The samples were then analysed by SDS–PAGE and autoradiography.

Figure 4.

A role for Acinus and AAC-11 in oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation. (A) U2OS cells were transfected with siRNA to Acinus or mock siRNA. After 48 h, cells were lysed and the lysates immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (B) Deregulation of Acinus does not inhibit apoptotic chromatin condensation. U2OS cells were transfected with siRNA to Acinus or mock siRNA. After 48 h, the cells were exposed to etoposide (ETO, 10 μM, 16 h) followed by 1 μM staurosporine (STS) for another 4 h or left untreated. DAPI stainings of these cells were then visualized under a fluorescence microscope. Results show the mean values±standard deviation from triplicate with 200 nuclei counted per condition. (C) A role for Acinus in oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation. U2OS cells were transfected with mock siRNA or siRNA to Acinus in the absence or together with Flag-tagged Acinus-L in which two silent mutations preventing interaction between siRNA and the Acinus mRNA were introduced (Acinus mut). After 48 h, the cells were treated as in (B). Subsequently, all DNA samples were extracted and separated on 1.5% agarose gels. (D) AAC-11 expression does not modulate drug-induced chromatin condensation. U2OS clones stably expressing T7-tagged AAC-11 or T7-tagged AAC-11 LL/RR were treated as in (B) and apoptotic chromatin condensation was measured as in (B). (E) AAC-11 expression prevents oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation. U2OS clones stably expressing T7-tagged AAC-11 or T7-tagged AAC-11 LL/RR the cells were treated as in (B). Subsequently, all DNA samples were extracted and separated on 1.5% agarose gels (top) or sub-G1 fraction was determined by flow cytometry (bottom). Each bar represents the mean±s.d. from three independent experiments. (F) AAC-11 expression does not prevent CAD DNAse activity. U2OS-stable clones were exposed to staurosporine (1 μM) for 2 h or left untreated. CAD was immunoprecipitated from the cell lysates with an anti-CAD antibody and the purified CAD immunocomplexes were incubated with plasmid DNA. The reaction samples were then separated by 1.8% agarose gel electrophoresis to visualize DNA degradation. (G) AAC-11 expression does not prevent H2AX phosphorylation. U2OS-stable clones were treated as in (F). Cell lysates were then analysed by western blotting using the indicated antibodies. (H) Deregulation of AAC-11 increases apoptotic oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation. U2OS control or AAC-11 shRNA-stable clones were cultured in the presence or absence of doxycycline (1 μg/ml) for 48 h. Cells were treated as in (B). Oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation was then estimated.

A role for Acinus and AAC-11 in DNA fragmentation

Acinus has been originally implicated to function in apoptotic chromatin condensation after cleavage by caspases (Sahara et al, 1999; Hu et al, 2005). However, Acinus has been recently proposed to rather contribute to oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation during apoptosis (Joselin et al, 2006). To gain access to the function of Acinus, we knocked down the expression of endogenous Acinus by RNA interference. Control immunoblotting revealed that Acinus was virtually totally depleted by its specific siRNA 48 h after transfection (Figure 4A). We next treated the transfected cells with etoposide/staurosporine and evaluated the influence of Acinus deregulation on chromatin condensation. As shown in Figure 4B, knocking down of Acinus did not prevent apoptotic chromatin condensation compared with control cells, but even seemed to slightly increase chromatin condensation. Of note, as described by Joselin et al (2006), we observed that effector caspases activation, after staurosporine treatment, was increased in apoptotic Acinus knockdown cells compared with control cells (Supplementary Figure S6). This increased activity might explain the acceleration of chromatin condensation in Acinus-depleted cells. Interestingly, down regulation of Acinus substantially prevented oligosomal DNA laddering (Figure 4C). Ectopic expression of a form of Acinus-L that cannot be degraded by the Acinus siRNA used, through introduction of silent mutations, significantly restored drug-induced DNA fragmentation (Figure 4C), indicating that the effect of the siRNA could be explained by specific silencing of Acinus. Therefore, our results suggest that, in our system, Acinus might not be involved in apoptotic chromatin condensation but rather is required for efficient DNA laddering during apoptosis.

AAC-11 suppresses Acinus cleavage from caspase-3 (Figure 3A), indicating a possible role for AAC-11 in the regulation of Acinus function in cell death. Therefore, we first analysed chromatin condensation in the stable U2OS cells expressing either AAC-11 WT or LL/RR mutant. On treatment with etoposide/staurosporine, both cell lines showed robust, comparable chromatin condensation, at a level similar to that of control cells (Figure 4D). Similar data were obtained when AAC-11 was expressed in HeLa cells (not showed). We next examined whether deregulation of AAC-11 altered apoptotic chromatin condensation. Here again, down regulation of AAC-11 did not alter etoposide/staurosporine-induced chromatin condensation (Supplementary Figure S7). The same data were obtained when HeLa cells were used (data not shown). Therefore, our results indicate that AAC-11 does not seem to modulate apoptotic chromatin condensation. We next investigated whether apoptotic DNA fragmentation was affected by AAC-11 expression. For that purpose, we examined the process of internucleosomal DNA cleavage in the different stable U2OS cell lines. Upon treatment with staurosporine, substantial DNA fragmentation occurred in control cells as well as AAC-11 LL/RR expressing cells as indicated by the appearance of the oligonucleosomal ladder (Figure 4E, top). However, DNA fragmentation was strongly reduced in AAC-11 expressing cells (Figure 4E, top). In line with these results, the percentage of Sub-G1 cells after etoposide treatment reached only 20% in cells expressing AAC-11 compared with 43 and 42% in cells expressing AAC-11 LL/RR and control cells, respectively (Figure 4E, bottom). The caspase-3 downstream target CAD (caspase-activated DNAse) has been reported to be an important DNAse associated with DNA fragmentation (Widlak et al, 2001). CAD is activated by the caspase-3-dependent cleavage of its inhibitor, ICAD, which sequesters CAD in healthy cells (Liu et al, 1997; Sakahira et al, 1998). To determine whether CAD activation still occurs when AAC-11 was expressed, extracts from the different cell lines prepared were analysed by western blotting with antibodies to CAD and ICAD. A similar amount of ICAD was degraded after 2 h of staurosporine treatment in all cell lines, indicating that AAC-11 did not prevent apoptotic ICAD cleavage (Supplementary Figure S8). We next investigated whether CAD activity was regulated by AAC-11. For that purpose, we used immunoprecipitated CAD from extracts prepared from the different cell lines treated or not with staurosporine, and measured its activity on naked DNA. Here again, CAD from all the tested extracts strongly cleaved the DNA at a similar level, indicating that AAC-11 does not seem to inhibit CAD DNAse activity (Figure 4F). Phosphorylation of the histone variant H2AX has been shown to be required for DNA ladder formation as it is critical for CAD-mediated DNA degradation, both in vivo and in vitro (Lu et al, 2006). We, therefore, determined whether H2AX phosphorylation was affected by AAC-11 expression. Western blotting analysis using an antibody that recognized H2AX phosphorylated at serine 139 indicated that etoposide induced a strong, comparable phosphorylation of H2AX in all cell lines (Figure 4G). Finally, silencing of AAC-11 markedly increased apoptotic DNA fragmentation after drug treatment (Figure 4H). As a corollary, substantial Acinus cleavage occurred in apoptotic cells (Figure 4H). Combined, these results indicate that both Acinus and AAC-11 may selectively regulate DNA fragmentation, but not chromatin condensation. As AAC-11, through binding to Acinus, prevents the apoptotic cleavage of Acinus (Figure 3A), it is possible that AAC-11 regulates Acinus role in apoptotic DNA laddering and that caspase cleavage of Acinus is required for DNA fragmentation.

AAC-11 contributes to Acinus signalling

If the physiological function of the physical AAC-11–Acinus interaction were to control Acinus-mediated DNA fragmentation, then inhibition of this interaction would be expected to stimulate apoptotic DNA fragmentation. Acinus interacts with AAC-11 through the LZ motif of AAC-11, and the oligomerization status of the LZ is crucial for this interaction (see above). Therefore, targeting the LZ of AAC-11 might prevent its binding to Acinus. For this purpose, we designed cell-permeable peptides spanning the LZ of AAC-11 as agents to inhibit oligomerization of the LZ domain of AAC-11. The wild-type peptide (Figure 5A) consisted of the region from residues 363–398 of the AAC-11 fused at the N terminus to an internalization sequence derived from the Antennapedia/Penetratin protein. The mutant peptide was identical except that leucines 384 and 391 in the LZ were mutated to arginines. Cellular uptake analysis of the two peptides indicated that their intracellular concentrations after 1 h incubation were similar (Figure 5B). The same results were obtained when HeLa, A549 and Molt-4 cells were used (not shown). We first tested the effect of the AAC-11 peptides on the LZ–LZ interaction. Cells coexpressing GFP-tagged AAC-11 (361–400) and GST-tagged AAC-11 (361–400) were incubated in the absence or with 10 μM of the peptides. Immunoprecipitation analysis indicated a drastic decrease in the LZ–LZ interaction in the presence of the wild-type peptide, whereas no inhibition was observed when the mutant peptide was used (Figure 5C). Our results thus indicate that the AAC-11 peptide acts as an inhibitor of AAC-11 LZ–LZ oligomerization in vivo. We then determined the ability of the different peptides to disrupt the AAC-11–Acinus interaction in vivo. As seen in Figure 5D, incubation of U2OS cells with the wild-type peptide disrupted the formation of the endogenous AAC-11–Acinus complex, whereas the amount of AAC-11 that co-immunoprecipitated with Acinus in the presence of the mutated peptide remained comparable to that of the control. Combined, the above data indicate that the wild-type peptide could indeed interfere with the oligomerization state of the LZ of AAC-11, thus preventing AAC-11 interaction with Acinus. We next investigated whether the wild-type peptide, given its ability to interfere with AAC-11–Acinus complex formation, was also able to inhibit the protective effect of AAC-11 on apoptotic cleavage of Acinus. U2OS cells were exposed with the peptides and treated with etoposide. Acinus processing in the different extracts was then evaluated by western blotting. As shown in Figure 5E, apoptotic processing of Acinus was largely increased when cells were incubated with the wild-type peptide, but not the mutant peptide. Interestingly, drug-induced oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation was markedly amplified (Figure 5F), fitting with our results that Acinus, after activation by caspases, is involved in apoptotic DNA laddering. Together, these data suggest that the LZ peptide is capable of inhibiting AAC-11–Acinus interaction and that AAC-11 constitutes a negative regulator of Acinus role in DNA fragmentation.

Figure 5.

(A) Sequences of the wild-type and mutant peptides corresponding to the LZ subdomain of AAC-11. The Antennapedia sequence is in bold. In the mutant peptide, mutations (leucines to arginines) are underlined. (B) Fluorimetry quantification of the cellular uptake of fluorescein-labelled peptides after 1 h in U2OS cells. Each bar represents the mean±s.d. from three independent experiments. (C) The wild-type peptide prevents LZ–LZ interaction. 293T cells were cotransfected with GFP-AAC-11 (361–400) together with GST-AAC-11 (361–400). At 24 h after transfection, cells were exposed for 3 h to the indicated peptides (10 μM), lysed and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-GFP and blotted with anti-GST. (D) The wild-type peptide disrupts endogenous AAC-11–Acinus interaction. U2OS cells were exposed for 3 h to the indicated peptides (10 μM), lysed and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Acinus antibody and blotted with an AAC-11-1 antibody. (E, F) The wild-type peptide enhances Acinus apoptotic degradation and oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation. (E) U2OS cells were exposed for 3 h to the indicated peptides (10 μM). The cells were then exposed to etoposide (20 μM) for 12 h, lysed and the lysates were immunoblotted with an anti-Acinus antibody. (F) U2OS cells were exposed for 3 h to the indicated peptides (10 μM). The cells were then exposed to staurosporine (1 μM) for 4 h or left untreated. Oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation was then estimated.

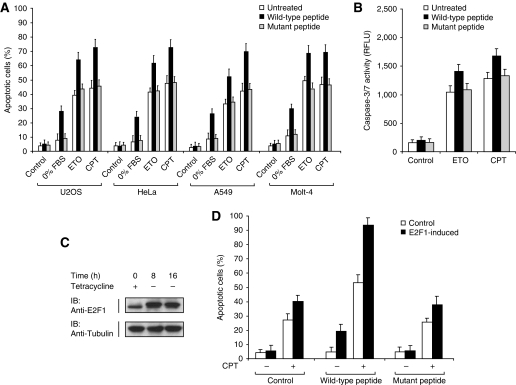

LZ peptide sensitizes cancer cells to drugs and E2F1-mediated cell death

As AAC-11 is highly expressed in several cancers, and its depletion drastically enhances the cytotoxic action of chemotherapeutic drugs, AAC-11 could constitute an attractive therapeutic target for the development of drugs capable of promoting death of tumour cells. Our results and others' (Tewari et al, 1997) indicate that the integrity of the LZ domain of AAC-11 is essential for its antiapoptotic properties. If the AAC-11 peptide increases apoptosis by disrupting the LZ structure, similarly to the LL/RR mutation, then this peptide should potentiate drug-induced cytotoxicity. We, therefore, evaluated the capacity of the LZ peptide to induce cell death a panel of cancer cells when added alone or in combination with chemotherapeutic drugs. Incubation for 20 h with the peptides did not result in significant cell death (Figure 6A). However, substantial apoptosis was detected in growth factor-deprived cells with the wild-type peptide, but not the mutant peptide (Figure 6A). Moreover, incubation of the cells with the wild-type peptide, but not the mutant peptide, elicited a marked increase in the proportion of apoptotic cells after treatment with etoposide or camptothecin in all cell lines (Figure 6A). The potentiation of drug-induced cell death by the wild-type peptide in U2OS cells was also illustrated by an increase in caspase-3/7 activity over the mutant peptide (Figure 6B). Same data were obtained with HeLa, A549 or Molt-4 cells (not shown). These results support the idea that targeting AAC-11, through a LZ peptide, drastically stimulates drug- or growth factor deprivation-induced apoptosis, and that AAC-11 may be used as a potential therapeutic target.

Figure 6.

The wild-type peptide increases drug-induced cell death. (A) U2OS, HeLa, A549 or Molt-4 cells were exposed for 3 h to the indicated peptides (10 μM). The cells were then exposed to etoposide (ETO, 20 μM) or camptothecin (CPT, 10 μM) for 16 h or cultivated under low-serum conditions or left untreated. The percentages of apoptotic cells were then determined as in Figure 1(B). (B) The wild-type peptide increases drug-induced effector caspases activity. U2OS cells were exposed for 3 h to the indicated peptides (10 μM) and exposed to etoposide (ETO, 20 μM) or camptothecin (CPT, 10 μM) for 5 h and caspase-3/7 activity was measured. (C) Induction of E2F1 in U2OS-E2F1 cells after removal of tetracycline. U2OS-E2F1 cells cultured in normal serum conditions were plated and the induction of E2F1 was blocked with 1 μg/ml tetracycline. After 24 h, the tetracycline was removed by washing the cells with fresh complete media and the cells were collected 8 and 16 h later. The cells lysates were immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies. (D) The wild-type peptide enhances E2F1- and camptothecin-induced apoptosis. U2OS cells cultured in normal serum conditions were exposed for 3 h to the indicated peptides (10 μM). E2F1 was then induced or not, and the cells exposed to camptothecin (CPT, 10 μM) for 16 h or left untreated. The percentages of apoptotic cells were then determined as in Figure 1(B).

Recently, a functional interaction between AAC-11 and E2F1 has been suggested (Morris et al, 2006). Using a Saos-2 cell line containing an inducible E2F1 expression system, Morris et al showed that AAC-11 efficiently suppressed E2F1-induced apoptosis (Morris et al, 2006). Even known deregulated E2F1 activity leads to uncontrolled cell proliferation, E2F1 can also efficiently induce apoptosis through p53-dependent and p53-independent pathways, and therefore constitutes an effective mechanism for suppressing tumorigenesis. We, therefore, tested whether the AAC-11 peptide could potentiate E2F1-dependent apoptosis. For that purpose, we used a U2OS tetracycline-off E2F1 inducible system (Hofland et al, 2000) to investigate the effect of the AAC-11 peptide to E2F1-induced cytotoxicity. In this system, the expression of E2F1 is induced by incubating the cells in tetracycline-free medium. As shown in Figure 6C, removal of tetracycline from the media caused a marked increase in E2F1 protein expression, as measured by western blot analysis. Overexpression of E2F1 did not result in an increase of spontaneous apoptosis (Figure 6D). However, incubation of the cells with the wild-type AAC-11 peptide, but not the mutant peptide, resulted in a significant apoptosis in the absence of any treatment (Figure 6D). This indicates that the AAC-11 peptide might ‘prime' the cells to E2F1-mediated apoptosis, resulting in cell death due to the E2F1 overexpression itself. Moreover, incubation of cells overexpressing E2F1 with the AAC-11 peptide resulted in a massive apoptosis after camptothecin treatment (Figure 6D). As most human cancers express high level of E2F1, either related to the lack of the retinoblastoma protein (pRB) or even in the presence of pRB, our data indicate that the AAC-11 peptide could be of therapeutic interest in a wide array of malignancies.

Discussion

In this report, we identify AAC-11 as an antiapoptotic protein involved in sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs. Silencing of AAC-11 in a panel of cancer and normal cells markedly enhanced sensitivity to the anticancer agents camptothecin and etoposide, whereas its overexpression had the opposite effect, interfering with drug-induced apoptosis. These results confirm the antiapoptotic properties of AAC-11 and are in keeping with a recent report in which increased expression of AAC-11 was found to protect primary liver cells from UV-induced apoptosis (Wang et al, 2008). Our data and that of others (Morris et al, 2006) indicate that AAC-11 negatively regulates E2F1-dependent apoptosis. The relationship of E2F1 expression to chemotherapeutic drugs-induced apoptosis has yielded various results. However, several reports have shown an increase in cellular toxicity to both etoposide and camptothecin on E2F1 expression, whereas sensitivity to cisplatin, 5-FU or paclitaxel remained unchanged or was diminished (Banerjee et al, 1998, 2000; Hofland et al, 2000; Nip and Hiebert, 2000; Yang et al, 2001; Dong et al, 2002; Obama et al, 2002). Therefore, the observed specificity for AAC-11 in etoposide- and camptothecin-induced cellular toxicity may reflect the crucial role of AAC-11 in E2F1-mediated cell death. Our results show that AAC-11 modulates Fas-mediated apoptosis, both in type I and II cells. As E2F1 has been shown to sensitize tumour as well as primary cells to apoptosis mediated by Fas ligand, irrelevantly of the mitochondrial amplification loop (Salon et al, 2006), the decrease of apoptosis observed when AAC-11 is expressed may again underline the importance of this protein in E2F1-mediated apoptosis.

Using a yeast two-hybrid approach, we identified Acinus as a binding partner of AAC-11. During apoptosis, Acinus is cleaved by caspases to produce an active fragment (p17) that has been shown to induce chromatin condensation (Sahara et al, 1999). Our findings indicate that AAC-11, on binding, prevents caspase-3-mediated cleavage of Acinus, both in vivo and in vitro, thus preventing generation of the p17 active fragment. AAC-11 binds to a region of Acinus (residues 840–918), which is very close to the caspase-3 cleavage sites (987 and 1093). Hence, AAC-11 bound to Acinus might prevent access of caspase-3 to its cleavage sites by steric hindrance. Another possibility is that AAC-11 might induce a conformational change of Acinus that would render the caspase cleavage sites inaccessible. Nevertheless, AAC-11, through direct interaction, does efficiently protect Acinus from apoptotic cleavage. However, determination of the detailed structural organization of the AAC-11–Acinus complex, as well as the precise mechanism by which AAC-11 prevents caspase-3 to cleave Acinus, awaits structural determination.

Acinus, after caspases cleavage, has been proposed to induce chromatin condensation (Sahara et al, 1999; Hu et al, 2005). Surprisingly, we found that knocking down of Acinus did not prevent apoptotic chromatin condensation, but rather slightly accelerated it. However, DNA fragmentation was impaired in Acinus knockdown cells. This indicates that, at least in our system, Acinus is required for apoptotic DNA fragmentation but not for chromatin condensation. Our results are in line with those of Joselin et al (2006), who, using a different setup, established a role for Acinus in DNA fragmentation. Interestingly, expression of AAC-11, but not the AAC-11 LZ mutant, which can no longer bind to Acinus, resulted in an inhibition of drug-induced DNA fragmentation, whereas chromatin condensation was not affected. Conversely, depletion of AAC-11 resulted in a marked increase in DNA fragmentation, concomitant with massive apoptotic Acinus cleavage. This indicates that Acinus cleavage, which is prevented by AAC-11 overexpression, is required for DNA fragmentation in our system. The caspase-3 target CAD has been reported to be the most important apoptotic nuclease (Widlak et al, 2001). In the absence of stimulation, CAD remains inactive through binding to its inhibitor ICAD. Our data indicate that AAC-11 expression, and, as a corollary, inhibition of Acinus apoptotic cleavage did not prevent caspase-mediated degradation of ICAD or the nuclease activity of CAD in vitro. We also did not detect a direct interaction between CAD/ICAD with Acinus or AAC-11 (data not shown). Phosphorylation of the histone variant H2AX, which has been shown to be required for DNA laddering on DNA damage (Lu et al, 2006), still occurred in AAC-11 overexpressing cells. Thus, at this moment, the precise mechanism by which Acinus and AAC-11 contribute to DNA fragmentation remains unclear. Recent observations suggest that, on induction of caspase-3-dependent apoptosis, CAD, which displays a preference for A/T rich chromatin region, becomes progressively associated with a subnuclear compartment called the nuclear matrix (Lechardeur et al, 2004). Of note, this compartment is involved in multiple nuclear functions, including RNA processing and regulation, and DNA at nuclear matrix is A/T rich (Nickerson, 2001). Recent observations suggest that Acinus-L contains a SAP domain, presumably involved in DNA binding with preference for A/T rich sequences (Aravind and Koonin, 2000). Even known this remains to be tested, it is therefore possible that Acinus may tether CAD to the chromatin and therefore is required for CAD access to its substrate DNA in A/T rich regions. Interestingly, our data indicate that AAC-11 does not prevent caspases activation but might specifically prevent apoptotic Acinus processing, thus suggesting that the antiapoptotic action of AAC-11 may reflect, at least partially, its inhibition of apoptotic DNA fragmentation. These observations are very similar to that of Lu et al who have shown that although caspase-3 and CAD were activated, apoptosis as well as DNA fragmentation were inhibited in H2AX deficient cells after UV or etoposide treatment (Lu et al, 2006). Therefore, our data suggest that AAC-11, like H2AX, cooperate with caspase-3 to determine the final cellular fate and confirm the role of the caspase-3/AAC-11/Acinus/CAD pathway in apoptosis. It is noteworthy that deregulation of AAC-11 in the P53 negative osteosarcoma Saos-2 has been shown to be lethal under condition of low-serum stress but has yielded no difference in cell death induced by different stimuli (Morris et al, 2006). Therefore, AAC-11 and Acinus roles in the apoptotic process may be cell-line specific and thus depend on the genetic background of the cell. In line with this hypothesis, overexpression of E2F1, which apoptotic function seems to be regulated by AAC-11, markedly increased the sensitivity to etoposide of the P53 positive OsACL and U2OS cells but the cooperative effect of E2F-1 and etoposide was not observed in Saos-2 cells (Yang et al, 2001). It is also likely that the antiapoptotic effect of AAC-11 involves alternative pathways that remain to be characterized. AAC-11 possesses a LZ domain that dictates its interaction with Acinus. Interestingly, mutation of the LZ, through substitution of two leucines to arginines, not only prevented AAC-11 to associate with Acinus, but also abolished the antiapoptotic effect of AAC-11 on drug-induced cell death. The latter observation is consistent with an earlier report in which the same mutation has been shown to abrogate AAC-11-mediated protection to growth factor withdrawal (Tewari et al, 1997). The wild-type LZ domain of AAC-11, but not the LL/RR mutant, can form oligomers, implying that the oligomeric status of the LZ of AAC-11 is critical for its physiologic function and suggesting that targeting the oligomerization state of the LZ of AAC-11 might prevent both its antiapoptotic function and its binding to Acinus. We, therefore, designed cell-permeable peptides corresponding to the LZ subdomain of AAC-11. Our data indicate that the wild-type peptide, but not the LL/RR mutant, not only abolished LZ oligomerization but also disrupted the endogenous AAC-11–Acinus complex. Moreover, the wild-type peptide, without inducing spontaneous apoptosis on its own, was able to drastically increase drug-induced apoptosis and caspase-3 activation, as well as apoptotic DNA fragmentation, similar to what observed when AAC-11 was down regulated. This increased caspase-3 activation might be explained because the peptide-treated cells are already ‘primed' by an increased apoptosis due to the inhibition of the antiapoptotic properties of AAC-11. Our data indicate that silencing of AAC-11, or treatment of cells with the wild-type peptide result in a virtually total degradation of Acinus after drug treatment. We, as well as Joselin et al, have noted an increase in staurosporin-induced effector caspase activation when Acinus was silenced (Joselin et al, 2006). Therefore, the complete degradation of Acinus in the absence of AAC-11 or when the cells are treated with the wild-type peptide might also participate in the increase of drug-induced caspase activity. Finally, the wild-type peptide was also able to potentiate E2F1-induced apoptosis, keeping with the recent observation that AAC-11 is a potent suppressor of E2F1-dependent apoptosis (Morris et al, 2006).

The results presented in this paper lead to two major conclusions. First, our data suggest that AAC-11 could constitute a potential therapeutic target in cancer. Most cancer cells express elevated levels of AAC-11 and AAC-11 expression seems to confer a poor outcome in subgroups of patients with non-small cell lung carcinoma (Sasaki et al, 2001). Moreover, AAC-11 overexpression has been reported to promote both cervical cancer cells growth and invasiveness (Kim et al, 2000). Our data indicate that incubation of U2OS cells with the AAC-11 peptide decreases mobility and invasiveness (data not shown). Targeting AAC-11 may therefore represent a promising approach to sensitize cancer cells to anticancer drug-induced apoptosis. Supporting this strategy, reduction in AAC-11 expression by siRNA led to a drastic increase of cell death after treatment by the anticancer drugs etoposide and camptothecin. Second, our findings suggest potential therapeutic applications using the AAC-11 peptide as prototypical drugs that can be used in combination with conventional therapies. The apoptotic effect of the AAC-11 peptide provides indeed proof of concept for the development of strategies based on the disruption of AAC-11 LZ oligomerization. Our goal now is to search for new peptides as well as small organic compounds able to inhibit specifically the protein–protein interactions within the LZ of AAC-11. Finding drug-like compound modulators of protein–protein interaction has long been regarded as intractable. However, recent developments suggest that such interaction domains may constitute a prospective target for small molecule inhibitors (Oltersdorf et al, 2005). The data contained in this paper suggest that it might be possible to generate AAC-11 specific inhibitors, acting on the oligomerization state of the LZ of the protein, that could be use to sensitize cancer cells for cancer therapy induced apoptosis.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Cells were cultivated in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (HeLa, A549 or 293T cells) or RPMI 1640 (U2OS, LCL, Jurkat or Molt-4 cells) (Gibco), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 mM HEPES buffer (Gibco), 200 μg/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate. HUVECs were purchased from Clonetics (San Diego, CA), and cultured in BulletKit media according to the manufacturer's instructions. The human osteosarcoma cell line U2OS-TA (referred here as U2OS-E2F1), a U2OS tetracycline-off E2F1 inducible system, was a gift from Dr Maxwell Sehested (Hofland et al, 2000). U2OS-E2F1 cells were cultivated in RPMI 1640 (Gibco) containing 25 mM HEPES buffer (Gibco) supplemented with 10% TET-approved FBS (Gibco), 200 μg/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 μg/ml puromycin and 1 μg/ml tetracycline.

Yeast two-hybrid screening procedure

Two-hybrid screen was performed using a cell-to-cell mating protocol as described earlier (Fromont-Racine et al, 2002) using Drosophila AAC-11 as bait and a highly complex, random primed Drosophila embryo cDNA library. Positive clones were obtained using the HIS3 reporter gene selection.

Reconstitution of in vitro Acinus activation system

In vitro translated Acinus-S was incubated for 2 h at 4°C with BSA, recombinant His-tagged AAC-11 or AAC-11 LL/RR in buffer A (20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM sodium EDTA, 1 mM sodium EGTA, 5 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.1 mM PMSF). Active caspase-3 was then added and the reaction mixtures incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The samples were then analysed by SDS–PAGE and autoradiography.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Data

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Nicholas J Dyson (Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center and Harvard Medical School, Charlestown, MA, USA), Professor Yoshihide Tsujimoto (Department of Medical Genetics, Biomedical Research Center, Osaka University Medical Scholl, Osaka, Japan), Dr Maxwell Sehested (Department of Pathology, Laboratory and Finsen Centers, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark) and Dr Christian Schwerk (Institute of Molecular Medicine, The University of Duesseldorf, Duesseldorf, Germany) for sharing reagents. We thank Professor John A Hickman (Institut de Recherches Servier, Cancer Research and Drug Discovery, 78290 Croissy-sur-Seine, France) for helpful discussions. We thank Christelle Doliger and Niclas Setterblad at the Imagery Department of the Institut Universitaire d'Hématologie IFR105 for the confocale microscopy. The imagery department is supported by grants from the Conseil Regional d'Ile-de-France and the Ministère de la Recherche. PR is supported by Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer.

References

- Alnemri ES, Livingston DJ, Nicholson DW, Salvesen G, Thornberry NA, Wong WW, Yuan J (1996) Human ICE/CED-3 protease nomenclature. Cell 87: 171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravind L, Koonin EV (2000) SAP—a putative DNA-binding motif involved in chromosomal organization. Trends Biochem Sci 25: 112–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee D, Gorlick R, Liefshitz A, Danenberg K, Danenberg PC, Danenberg PV, Klimstra D, Jhanwar S, Cordon-Cardo C, Fong Y, Kemeny N, Bertino JR (2000) Levels of E2F-1 expression are higher in lung metastasis of colon cancer as compared with hepatic metastasis and correlate with levels of thymidylate synthase. Cancer Res 60: 2365–2367 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee D, Schnieders B, Fu JZ, Adhikari D, Zhao SC, Bertino JR (1998) Role of E2F-1 in chemosensitivity. Cancer Res 58: 4292–4296 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clegg N, Ferguson C, True LD, Arnold H, Moorman A, Quinn JE, Vessella RL, Nelson PS (2003) Molecular characterization of prostatic small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Prostate 55: 55–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cory S, Adams JM (2002) The Bcl2 family: regulators of the cellular life-or-death switch. Nat Rev 2: 647–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong YB, Yang HL, Elliott MJ, McMasters KM (2002) Adenovirus-mediated E2F-1 gene transfer sensitizes melanoma cells to apoptosis induced by topoisomerase II inhibitors. Cancer Res 62: 1776–1783 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromont-Racine M, Rain JC, Legrain P (2002) Building protein–protein networks by two-hybrid mating strategy. Meth Enzymol 350: 513–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofland K, Petersen BO, Falck J, Helin K, Jensen PB, Sehested M (2000) Differential cytotoxic pathways of topoisomerase I and II anticancer agents after overexpression of the E2F-1/DP-1 transcription factor complex. Clin Cancer Res 6: 1488–1497 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Yao J, Liu Z, Liu X, Fu H, Ye K (2005) Akt phosphorylates acinus and inhibits its proteolytic cleavage, preventing chromatin condensation. EMBO J 24: 3543–3554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igney FH, Krammer PH (2002) Death and anti-death: tumour resistance to apoptosis. Nat Rev 2: 277–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone RW, Ruefli AA, Lowe SW (2002) Apoptosis: a link between cancer genetics and chemotherapy. Cell 108: 153–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joselin AP, Schulze-Osthoff K, Schwerk C (2006) Loss of Acinus inhibits oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation but not chromatin condensation during apoptosis. J Biol Chem 281: 12475–12484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JW, Cho HS, Kim JH, Hur SY, Kim TE, Lee JM, Kim IK, Namkoong SE (2000) AAC-11 overexpression induces invasion and protects cervical cancer cells from apoptosis. Lab Invest 80: 587–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krejci P, Pejchalova K, Rosenbloom BE, Rosenfelt FP, Tran EL, Laurell H, Wilcox WR (2007) The antiapoptotic protein Api5 and its partner, high molecular weight FGF2, are up-regulated in B cell chronic lymphoid leukemia. J Leukoc Biol 82: 1363–1364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechardeur D, Xu M, Lukacs GL (2004) Contrasting nuclear dynamics of the caspase-activated DNase (CAD) in dividing and apoptotic cells. J Cell Biol 167: 851–862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Zou H, Slaughter C, Wang X (1997) DFF, a heterodimeric protein that functions downstream of caspase-3 to trigger DNA fragmentation during apoptosis. Cell 89: 175–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Zhu F, Cho YY, Tang F, Zykova T, Ma WY, Bode AM, Dong Z (2006) Cell apoptosis: requirement of H2AX in DNA ladder formation, but not for the activation of caspase-3. Mol Cell 23: 121–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris EJ, Michaud WA, Ji JY, Moon NS, Rocco JW, Dyson NJ (2006) Functional identification of Api5 as a suppressor of E2F-dependent apoptosis in vivo. PLoS Genetics 2: e196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson J (2001) Experimental observations of a nuclear matrix. J Cell Sci 114: 463–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nip J, Hiebert SW (2000) Topoisomerase IIalpha mediates E2F-1-induced chemosensitivity and is a target for p53-mediated transcriptional repression. Cell Biochem Biophys 33: 199–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obama K, Kanai M, Kawai Y, Fukushima M, Takabayashi A (2002) Role of retinoblastoma protein and E2F-1 transcription factor in the acquisition of 5-fluorouracil resistance by colon cancer cells. Int J Oncol 21: 309–314 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oltersdorf T, Elmore SW, Shoemaker AR, Armstrong RC, Augeri DJ, Belli BA, Bruncko M, Deckwerth TL, Dinges J, Hajduk PJ, Joseph MK, Kitada S, Korsmeyer SJ, Kunzer AR, Letai A, Li C, Mitten MJ, Nettesheim DG, Ng S, Nimmer PM et al. (2005) An inhibitor of Bcl-2 family proteins induces regression of solid tumours. Nature 435: 677–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahara S, Aoto M, Eguchi Y, Imamoto N, Yoneda Y, Tsujimoto Y (1999) Acinus is a caspase-3-activated protein required for apoptotic chromatin condensation. Nature 401: 168–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakahira H, Enari M, Nagata S (1998) Cleavage of CAD inhibitor in CAD activation and DNA degradation during apoptosis. Nature 391: 96–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salon C, Eymin B, Micheau O, Chaperot L, Plumas J, Brambilla C, Brambilla E, Gazzeri S (2006) E2F1 induces apoptosis and sensitizes human lung adenocarcinoma cells to death-receptor-mediated apoptosis through specific downregulation of c-FLIP(short). Cell Death Differ 13: 260–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki H, Moriyama S, Yukiue H, Kobayashi Y, Nakashima Y, Kaji M, Fukai I, Kiriyama M, Yamakawa Y, Fujii Y (2001) Expression of the antiapoptosis gene, AAC-11, as a prognosis marker in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 34: 53–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaffidi C, Fulda S, Srinivasan A, Friesen C, Li F, Tomaselli KJ, Debatin KM, Krammer PH, Peter ME (1998) Two CD95 (APO-1/Fas) signaling pathways. EMBO J 17: 1675–1687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tewari M, Yu M, Ross B, Dean C, Giordano A, Rubin R (1997) AAC-11, a novel cDNA that inhibits apoptosis after growth factor withdrawal. Cancer Res 57: 4063–4069 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berghe L, Laurell H, Huez I, Zanibellato C, Prats H, Bugler B (2000) FIF [fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2)-interacting-factor], a nuclear putatively antiapoptotic factor, interacts specifically with FGF-2. Mol Endocrinol (Baltimore, Md) 14: 1709–1724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Lee AT, Ma JZ, Wang J, Ren J, Yang Y, Tantoso E, Li KB, Ooi LL, Tan P, Lee CG (2008) Profiling microRNA expression in hepatocellular carcinoma reveals microRNA-224 up-regulation and apoptosis inhibitor-5 as a microRNA-224-specific target. J Biol Chem 283: 13205–13215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widlak P, Li LY, Wang X, Garrard WT (2001) Action of recombinant human apoptotic endonuclease G on naked DNA and chromatin substrates: cooperation with exonuclease and DNase I. J Biol Chem 276: 48404–48409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang HL, Dong YB, Elliott MJ, Wong SL, McMasters KM (2001) Additive effect of adenovirus-mediated E2F-1 gene transfer and topoisomerase II inhibitors on apoptosis in human osteosarcoma cells. Cancer Gene Ther 8: 241–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Data