SYNOPSIS

Objectives

Population-based landline telephone surveys are potentially biased due to inclusion of only people with landline telephones. This article examined the degree of telephone coverage bias in a low-income population.

Methods

The Charles County Cancer Survey (CCCS) was conducted to evaluate cancer screening practices and risk behaviors among low-income, rural residents of Charles County, Maryland. We conducted face-to-face interviews with 502 residents aged 18 years and older. We compared the prevalence of health behaviors and cancer screening tests for those with and without landline telephones. We calculated the difference between whole sample estimates and estimates for only those respondents with landline telephones to quantify the magnitude of telephone coverage bias.

Results

Of 499 respondents who gave information on telephone use, 80 (16%) did not have landline telephones. We found differences between those with and without landline telephones for race/ethnicity, health-care access, insurance coverage, and several types of cancer screening. The absolute coverage bias ranged up to 6.5 percentage points. Simulation scenarios showed the magnitude of telephone coverage bias decreases as the percent of the population with landline telephone coverage increases, and as landline telephone coverage increases, the estimates from a landline telephone survey would approximate the estimates from a face-to-face survey.

Conclusions

Our findings highlighted the need for targeted face-to-face surveys to supplement telephone surveys to more fully characterize hard-to-reach subpopulations. Our findings also indicated that landline telephone-based surveys continue to offer a cost-effective method for conducting large-scale population studies in support of policy and public health decision-making.

Most population-based surveys are conducted by telephone interviews. Telephone surveys are popular for a variety of reasons: they are more economical, faster to complete, and less prone to interviewer bias, and they present no interviewer safety issues. Telephone surveys rely on the underlying assumption that the results obtained from those who are reached and who agree to the interview are generalizable to the population as a whole. Telephone coverage bias is the expected difference between the results estimated from a telephone survey sample and the true population value. Because the sampling frame of random-digit dialed (RDD) telephone surveys is landline telephone numbers, the surveys are prone to telephone coverage bias, as they do not reach households without landline telephones,1–3 and populations without landline telephones are significantly different from those with telephones.4,5 The magnitude of this bias is proportional to the percent of the population without a landline telephone and the magnitude of the differences between the populations with and without landline telephones; therefore, estimates from RDD surveys could be under- or overestimates, depending on the direction of the difference between the populations with and without landline telephones. The bias can be significant among low-income, rural, and minority households, as these subpopulations may have different characteristics and behaviors.6

In the United States, telephone coverage is constantly increasing, and since 1970, more than 90% of the U.S. population has had telephone service in the home (referred to as landline telephones). The growth in telephone coverage over time was approximately 3% per year until 2000. Since 2000, the number of landline telephones has declined, most likely due to the exclusive use of cellular telephones and replacement of dial-up Internet service with broadband service.7 Due to these changes in the trends of telephone coverage, we would expect telephone coverage bias to be higher in subpopulations that have lower landline telephone coverage, such as young adults with only cellular telephones, low-income adults with only cellular telephones or no landline telephones, and deaf or hearing-impaired people who have limited access to telephone-based communication.6,8,9

This analysis sought to determine the magnitude of telephone coverage bias that could be encountered in telephone-based surveys, when the studied population is known to be rural and of low income.

METHODS

We conducted the Charles County Cancer Survey (CCCS) to evaluate cancer screening practices and risk-prevention behaviors, as well as demographic factors, among low-income and rural residents of Charles County, Maryland. Two different questionnaires were used: one to examine cancer screening practices and risk behaviors in residents aged 40 years and older, and the other to examine cancer prevention and risk behaviors in residents aged 18 to 39 years. In the demographic portion of the survey, respondents were asked whether they had a home telephone (landline telephone) and whether they had a cellular telephone.

We selected areas identified to have low-income households through previous outreach efforts by the Charles County Department of Health to be the source population for the survey. The areas included a mobile home park, Section 8 apartments and housing units, and pockets of homes and trailers in rural areas of the county. In addition, surveys were also administered at two health clinics for low-income patients. Personnel from the Charles County Department of Health and interviewers hired specifically for this project conducted the surveys as face-to-face interviews. Prior to the start of the survey, we conducted rigorous training of the interviewers to ensure standardized questionnaire administration and scoring. The Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) of the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and the University of Maryland, Baltimore, School of Medicine approved the survey questionnaire and protocol.

For each household approached, all interested residents living in the home who were aged 18 years and older were invited to participate in the survey. The interviewer explained the nature and purpose of the survey, and read a verbal statement of informed consent, which the IRBs had previously approved, to each prospective participant. If verbal consent was given, the interviewer administered the survey in person at that time. Each respondent received a $10 gift certificate for participating in the survey.

We obtained convenience samples of approximately 250 people for each age group (18 to 39 years, and 40 years and older), and analyzed information on demographic variables, health insurance, recent physical examination, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and folic acid intake for the entire sample. Questions on cancer screening were analyzed as follows: (1) ever had a colonoscopy, for adults aged 50 years and older; (2) ever had a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test, for African American men aged 45 years and older and all other men aged 50 years and older; (3) ever had a mammogram, for all women aged 40 years and older; and (4) ever had an oral cancer examination, for all adults aged 40 years and older.

Data analysis

We analyzed the data using SAS® version 9.110 in four steps:

We determined the prevalence for each variable of interest (e.g., demographics, health-care access, cancer screening, and lifestyle/behavioral factors) in the overall sample and according to telephone status (among those respondents with and those without landline telephones). Sample proportions were used in the analysis. Although our sampling methods allowed more than one family member per household to be included, repeated measurement analysis to control for within-household correlations revealed that our results did not change due to inclusion of more than one family member per household.

We performed a bivariate analysis to identify differences between respondents with and without landline telephones. We calculated proportions, 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and p-values.

We calculated the magnitude of telephone coverage bias for each variable that differed between respondents with and without landline telephones. We defined coverage bias as the difference between the overall sample estimate and the estimate for those with landline telephones. Telephone coverage bias is the expected difference between the estimates from a telephone survey sample and the true population value. If we could include all households with a landline telephone in a survey and they all responded to the interview, the landline telephone bias would be the difference between the estimate from that survey and the actual population parameter (which would be based on responses of all households with and without landline telephones) due to incomplete landline telephone coverage.

- To assess the impact of telephone coverage on bias estimates and on observed prevalence of health indicators, using colonoscopy as an example, we calculated the expected prevalence in the population (assuming that our overall sample prevalence is an unbiased estimate of the population prevalence) and expected coverage bias based on the following equations:

where,

- A = prevalence of colonoscopy among individuals with landline telephones, using A=0.59, which is the sample prevalence of colonoscopy for those with land-line telephones

- B = percentage of individuals with landline telephones, using B as a sequence of difference values 0%–100%

- C = prevalence of colonoscopy among individuals without landline telephones, using C=0.18, which is the sample proportion of colonoscopy for those without landline telephones in our sample of face-to-face interviews

- 1 – B = percentage without landline telephones

RESULTS

We approached 714 households for interviews; 169 households (24%) did not answer; 103 households (14%) refused enumeration; three households (<1%) were ineligible following enumeration; at 34 households (5%), enumeration was not conducted for other reasons (e.g., household was vacant); and 405 (57%) households were found to be eligible. Of the 405 eligible households, 312 (77%) participated in the survey, resulting in 446 interviews. An additional 56 interviews were conducted at the participating clinics.

A total of 502 individuals (median age of 39 years) participated in the CCCS. The study population was predominantly female (68%) and African American (72%). Approximately 75% of respondents had completed at least a high school education, and 54% were self-employed or employed for wages at the time of the survey. More than half (53%) of respondents reported an annual household income of less than $20,000 (Table 1). Of 499 respondents, 43% had only landline telephones, 41% said they had both landline and cellular telephones, 12% had a cellular telephone only, and 4% had neither (data not shown).

Table 1.

Selected demographic characteristics of the survey sample, Charles County Cancer Survey, 2005

CI = confidence interval

Individuals without landline telephones were more likely than those with landline telephones to be white and to have an income of $20,000 to <$35,000 (Table 2). Gender, age, marital status, and education level did not differ by telephone status.

Table 2.

Selected demographic characteristics of the survey sample by landline telephone status, Charles County Cancer Survey, 2005

CI = confidence interval

NA = not available

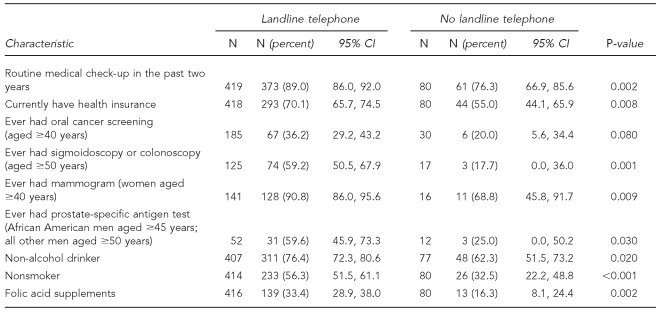

As shown in Table 3, respondents without landline telephones were less likely than respondents with landline telephones to have had a routine medical checkup in the past two years (76% vs. 89%) or to have current insurance coverage (55% vs. 70%). Respondents without landline telephones were also less likely than those with landline telephones to have ever had a colonoscopy (18% vs. 59%), a mammogram (69% vs. 91% among women), or a PSA test (25% vs. 60% among men). The prevalence of non-alcohol drinkers (in the last 30 days) and nonsmokers was significantly lower among people without landline telephones, as was use of folic acid supplements. Body mass index, vegetable and fruit consumption, and frequency and duration of physical activity did not differ by landline telephone status (data not shown). The data provided moderate evidence that the prevalence of oral cancer screening was lower among respondents without land-line telephones (20% vs. 36%).

Table 3.

Health-care access, cancer screening, and health behavior indicators by landline telephone status, Charles County Cancer Survey, 2005

CI = confidence interval

We assessed the magnitude of telephone coverage bias for variables that differed by telephone coverage status in the bivariate analysis (Table 4). In our sample of mainly low-income adults, the difference between the percentage obtained from the entire sample and the percentage obtained from only those with landline telephones (i.e., the telephone coverage bias) ranged from 2.1 to 6.5 percentage points. We found the largest differences for ever having had a PSA test (6.5 percentage points), ever having had a colonoscopy (5.0 percentage points), and nonsmoking status (3.8 percentage points). It is worth noting that the prevalence estimates for the overall sample were included in the CIs for estimates from participants with landline telephones only.

Table 4.

Magnitude of telephone coverage bias in estimates of health behavior indicators, Charles County Cancer Survey, 2005

aTelephone coverage bias = prevalence for whole sample – prevalence among respondents with landline phones, in percentage points

CI = confidence interval

To demonstrate the effect of landline telephone coverage on telephone coverage bias, we ran a series of calculations using CCCS data on prevalence of ever having had a colonoscopy among people with and without landline telephones. Under the scenario shown in the Figure, the magnitude of telephone coverage bias decreases as the percent of population with landline telephone coverage increases. For example, at 75% telephone coverage, the magnitude of bias is approximately 10%. When telephone coverage increases to 95%, the magnitude of the bias declines to only 2%.

To assess the effect of telephone coverage on the prevalence of health outcome measures estimated from face-to-face surveys, we calculated the expected prevalence of colonoscopy with varying levels of telephone coverage. Under the second scenario shown in the Figure, the expected prevalence of colonoscopy in a face-to-face survey would be 49%, assuming a prevalence of 59% among people with landline telephones (based on the findings in CCCS) and landline telephone coverage of 75% in the overall population. Similarly, with 95% telephone coverage, the expected prevalence of colonoscopy as estimated by a face-to-face survey would be 57%. Thus, as telephone coverage increases, the estimates from a telephone survey would approximate the expected estimates from a face-to-face survey.

DISCUSSION

Our study showed significant differences in some demographic factors and health risk behaviors between individuals with and without landline telephones. Other investigators have also reported evidence supporting the presence of such differences. In 1997, Arday et al.11 investigated the effect of RDD telephone survey methods and face-to-face survey methods on smoking estimates by comparing results from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS, an RDD telephone survey)12 with results from the Current Population Survey (CPS, a population-based survey).13 They reported that for three study periods (1985, 1989, and 1992–1993), smoking prevalence estimates from the BRFSS were lower than overall smoking prevalence estimates from the CPS.11 According to Ford, significant differences between individuals with and without telephones were observed in demographics and lifestyle characteristics, including health status, smoking, and physical activity.14

Although our results revealed absolute telephone coverage bias as high as 6.5 percentage points, the point estimates for the overall sample were within the CIs of the estimates of those with landline telephones. This finding supports the use of RDD telephone survey methods to assess and collect information about the general population. Similar to our results, the study by Arday et al. comparing BRFSS and CPS found an absolute bias ranging from 0.7 to 2.0 percentage points.11 In addition, data from the household-based National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) suggested that the difference in health indicators between all households and those with telephones was less than 1%. These -differences were of similar magnitude when the analysis was restricted to respondents below the poverty level with telephone coverage of 83%.15 The higher magnitude of bias observed in our study compared with the previously described studies could be explained by the higher noncoverage in our sample compared with the NHIS, BRFSS, and CPS.

Other biases could arise due to the mode of -interview. Response bias could be encountered in telephone surveys due to higher nonresponse than face-to-face surveys. Although nonresponse rates are higher in telephone surveys, they are also increasing in face-to-face surveys, such as the NHIS.16,17 Proper weighting methods could be used to minimize the magnitude of nonresponse bias in telephone surveys. On the other hand, studies have shown that respondents in telephone surveys tend to report more health-related events than respondents in face-to-face interviews, suggesting that telephone interviews provide more accurate estimates.18

Another growing concern that is jeopardizing telephone surveys is the increase in cellular telephone usage, replacing landline telephones. In the past, the lack of landline telephones was due largely to affordability. With the increasing trend toward cellular telephone use, more individuals are electing not to have landline telephones.19 These individuals may be different from those who have landline telephones. Data from the NHIS were used to assess the possible impact of the increase in cellular telephone use on estimates obtained from telephone surveys. The authors concluded that the bias resulting from exclusion of cellular telephone users was sufficiently small that a change in methods was not warranted.20

We performed our survey as part of the Maryland Cancer Surveys project, which also performs a biennial statewide landline telephone survey on cancer screening and risk behaviors. We partnered with the Charles County Department of Health to use their knowledge of the county demographics to reach a low-income population for this face-to-face survey. Because this was a convenience sample, the results may not be generalizable to the rural, low-income population of Charles County or to the rural areas of Maryland as a whole. Our sampling frame allowed more than one member to participate per household, which is different from most RDD telephone surveys. We conducted repeated measurement analysis to control for within-household correlations arising due to the enrollment of more than one member per household. We found that all variables that were significantly associated with landline telephone status in the unadjusted analysis (i.e., analysis not adjusting for interhousehold correlations) remained significant (data not shown). In our bias study, we assumed that telephone survey respondents were similar to the subpopulation with landline telephones in our sample. Thus, estimates for respondents with landline telephones in our survey would be expected to approximate estimates from telephone surveys. This assumption could be invalid if this subpopulation is systematically more or less likely to respond to a telephone survey than a face-to-face survey.

CONCLUSION

As demonstrated in the CCCS and other surveys,11,14 people without landline telephones differ in important ways from those who do have telephones. We found telephone coverage bias in our rural, low-income sample to be higher than bias calculated in previous studies that looked at this question in larger populations. This finding highlights the continuing need for such targeted face-to-face surveys to supplement telephone surveys as a means of more fully characterizing hard-to-reach subpopulations. Such surveys can be invaluable for identifying unique needs of groups not reached by telephone surveys, including those of low-income and non-English-speaking people. However, our findings also indicate that estimates derived from telephone-based surveys can provide reasonable representations of the overall population prevalence. Thus, telephone surveys continue to offer a cost-effective method for conducting large-scale population studies in support of policy and public health decision-making.

Figure.

Magnitude of absolute coverage bias and expected colonoscopy prevalence by various phone coverage percentages,a,b Charles County Cancer Survey, 2005

aExpected colonoscopy prevalence and expected coverage bias calculated as follows:

Expected prevalence of colonoscopy in the population = [(A*B) + (C *(1–B))] * 100

Expected coverage bias = expected colonoscopy prevalence – A

bCalculations are based on these assumptions:

A = Prevalence of ever having colonoscopy among respondents with landline telephones = 59%

B = Percentage of individuals with landline telephones, using B as a sequence of difference values 0%–100%

C = Prevalence of ever having colonoscopy among respondents with no landline telephones = 18%

Footnotes

This survey project was supported by the Maryland Cigarette Restitution Fund Program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Groves RM, Biemer PP, Lyberg LE, Massey JT, Nicholls WL, Waksberg J, editors. Telephone survey methodology. New York: John Wiley – Sons, Inc.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Groves RM. Theories and methods of telephone surveys. Annu Rev Sociol. 1990;16:221–40. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weeks MF, Kulka RA, Lessler JT, Whitmore RW. Personal versus telephone surveys for collecting household health data at the local level. Am J Public Health. 1983;73:1389–94. doi: 10.2105/ajph.73.12.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groves RM. Actors and questions in telephone and personal interview surveys. Public Opin Q. 1979;43:190–205. doi: 10.1086/268512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcus AC, Crane LA. Telephone surveys in public health research. Med Care. 1986;24:97–112. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198602000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keeter S. Estimating telephone noncoverage bias with a telephone survey. Public Opin Q. 1995;59:196–217. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Federal Communication Commission, Industry Analysis and Technology Division, Wireline Competition Bureau (US) Trends in telephone service. 2007. [cited 2008 Apr 15]. Available from: URL: http://www.fcc.gov/wcb/iatd/trends.html.

- 8.Barnett S, Franks P. Telephone ownership and deaf people: implications for telephone surveys. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1754–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.11.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bindman AB, Grumbach K, Keane D, Lurie N. Collecting data to evaluate the effect of health policies on vulnerable populations. Fam Med. 1993;25:114–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.SAS Institute. Inc. SAS®: Version 9.1. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arday DR, Tomar SL, Nelson DE, Merritt RK, Schooley MW, Mowery P. State smoking prevalence estimates: a comparison of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System and concurrent population surveys. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1665–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.10.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. 2008. [cited 2008 Apr 15]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/BRFSS/index.htm.

- 13.Census Bureau (US) Current Population Survey: a joint effort between the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Census Bureau. [cited 2008 Apr 15]. Available from: URL: http://www.census.gov/cps.

- 14.Ford ES. Characteristics of survey participants with and without a telephone: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:55–60. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00225-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson JE, Nelson DE, Wilson RW. Telephone coverage and measurement of health risk indicators: data from the National Health Interview Survey. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1392–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.9.1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Modi M. National Health Interview Survey, 1995–2004 redesign. Surveys measuring well-being. 2000. [cited 2008 Apr 15]. Available from: URL: http://www.nber.org/∼kling/surveys/NHIS.htm.

- 17.Pleis JR, Lethbridge-Cejku M. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2005. Vital Health Stat. 2006;10(232) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groves RM. Research on survey data quality. Public Opin Q. 1987;51(4 Pt 2):S156–72. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blumberg SJ, Luke JV. Wireless substitution: early release of estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, July–December 2007. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statisics (US); 2008. [cited 2008 Sep 8]. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/wireless200805.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blumberg SJ, Luke JV, Cynamon ML. Telephone coverage and health survey estimates: evaluating the need for concern about wireless substitution. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:926–31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]