SYNOPSIS

Objective

There has been an abundance of research evaluating prenatal and postnatal smoking abstinence programs. However, few researchers have tested postpartum relapse interventions that address secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure. Pregnant women exposed to SHS are more likely to relapse. This article explores the similarities and differences among postpartum interventions that incorporate SHS education. Generating knowledge about the components of postpartum relapse prevention interventions that do and do not achieve prolongation of abstinence is integral to the development of effective SHS interventions that help women achieve lifelong abstinence.

Methods

We used a methodological review of 11 randomized, controlled trials testing the efficacy of relapse prevention interventions that address SHS exposure. We compared intervention strength, biomarker validation of home smoking and SHS, as well as abstinence and relapse rates. We examined three predictors of postpartum relapse: (1) partner smoking in the home, (2) adoption of home smoking restrictions, and (3) motivation/confidence to remain abstinent.

Results

Findings revealed a need for more comprehensive SHS interventions and a clear delineation of abstinence/relapse terminology. Biomarker validation of home smoking and SHS was primarily measured by self-report, passive nicotine monitors, and hair nicotine levels. Furthermore, studies using nurse- and pediatrician-led interventions resulted in the lowest relapse rates.

Conclusion

A comprehensive intervention that specifically prioritizes parental education on the health effects of SHS on the family, empowerment of the mother and family members to remain abstinent and adopt a smoke-free home smoking policy, and partner influence on smoking could result in a significant reduction in postpartum relapse rates.

During the past two decades, there has been an abundance of research evaluating prenatal and postnatal smoking abstinence programs.1,2 However, few researchers have tested postpartum relapse interventions that address secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure. Several studies have found that pregnant women exposed to SHS are more likely to relapse.3,4

Tobacco is the single most modifiable cause of poor pregnancy outcomes. Throughout the past decade, national smoking abstinence rates during pregnancy have decreased to 11%, yet nearly two-thirds of mothers who quit during pregnancy relapsed within one year.5 Postpartum smoking relapse may be as high as 85%, and of those who relapse, 67% resume smoking at three months, and up to 90% by six months.6–8 Women exposed to SHS in their homes are less likely to remain abstinent than those who live with nonsmokers.4 Many investigators have examined smoking abstinence in the context of the woman's pregnancy, while excluding the postpartum period. Other investigators have included relapse prevention interventions in the prenatal period, but have not carried the intervention into the postpartum period. There are even fewer intervention studies addressing postpartum smoking relapse and SHS exposure during and after pregnancy.

We evaluated selected studies that addressed both smoking relapse prevention and the effects of home exposure to SHS during the postpartum period. First, we conducted a brief overview of the characteristics of women who smoke during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Then we explored specific components of the studies, including sample characteristics; recruitment criteria; study designs; measurements of abstinence, relapse, and SHS; postpartum interventions specific to SHS; and other intervention characteristics and relapse rates. Due to their influence on smoking abstinence rates, three predictors of postpartum relapse emerged: (1) having a husband or partner smoking in the home, (2) adoption of a home smoking policy, and (3) confidence and/or motivation to remain abstinent.

BACKGROUND

There is strong evidence that a baby's health is the primary motivator in a mother's decision to quit smoking during pregnancy. However, high relapse rates suggest that mothers are less aware of the adverse effects of SHS on their babies.8,9 There is no debate that smoking and SHS exposure during pregnancy places pregnant women at greater risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes. Smoking during pregnancy contributes to a higher risk for experiencing infertility, premature rupture of membranes, preterm delivery, and delivering a low birthweight or small-for-gestational-age infant.5 In 2006, the U.S. Surgeon General reported that there was no safe level of SHS exposure, and in fact, SHS exposure causes premature death in infants and adults. SHS exposure also increases the risk of respiratory and ear infections, as well as the frequency and severity of asthma events in children, and is responsible for approximately 3,000 cases of lung cancer deaths among nonsmokers each year. Clearly, women who sustain abstinence throughout pregnancy and the postpartum period can significantly reduce the health effects of smoking and SHS on themselves and their infants.10 Although the effects of SHS exposure on children are well-documented, there are limited studies addressing SHS exposure in the home and postpartum smoking relapse.

It is important to identify the characteristics of women who are more likely to relapse. Spontaneous quitters are more likely to maintain long-term postpartum abstinence than those that receive interventional support of education. Prior research has identified several factors commonly associated with spontaneous cessation, including younger age, first pregnancy, higher self-confidence, and waiting longer to smoke the first cigarette of the day.11 Furthermore, experts in smoking cessation consistently identify women who are SHS exposed, poor, depressed, less educated, and heavy smokers as more at risk for postpartum relapse.12,13 Government reports as well as published reviews consistently report age, race/ethnicity, smoking frequency, education, and marital status as predictors of smoking during pregnancy.4,5,8 Although pregnancy is an opportune time to quit smoking, only 18% to 25% of women quit upon confirmation of their pregnancy.14 Women who smoke during pregnancy are often young (15 to 24 years of age), Caucasian, moderate to heavy smokers (≥20 cigarettes per day), less educated (<12 years of education), and unmarried.8,14

The postpartum period is generally defined as the six weeks following birth.15 Women who experience postpartum relapse are generally defined as those who quit before or during pregnancy and then resume smoking within one year of the delivery.8 Characteristics of women who relapse are similar to those who smoke during pregnancy, with the exception of education level and marital status. Women who relapse are more likely to be married or living with a partner and have a high school education.16,17 Fingerhut et al. reported that there was limited evidence showing that education influenced relapse rates; however, educational level greatly impacted the likelihood of smoking and quitting during pregnancy.8

METHODS

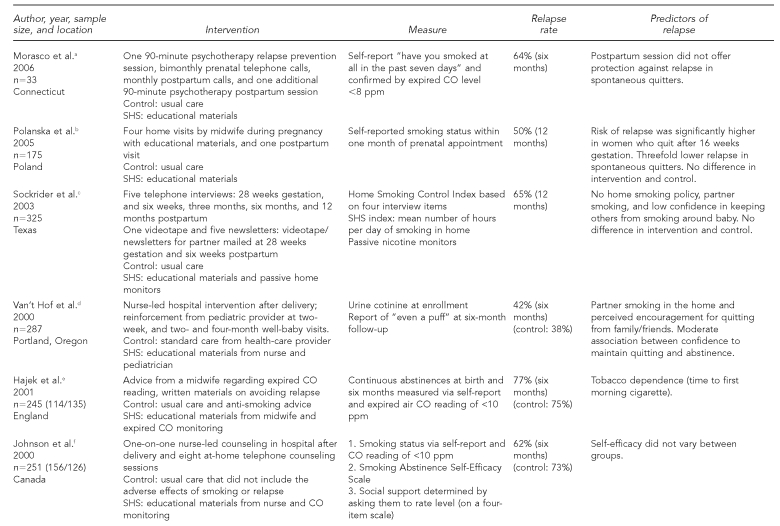

We gathered information via a literature search of Medline, PubMed, Cinahl, and Psych Abstracts. We examined studies published from 1995 to 2008. Keywords or versions of these keywords that were used in this search included environmental tobacco smoke, SHS, passive smoking, smoking, pregnancy, postpartum, relapse, and abstinence. As of May 2008, advanced searches ranged from 6,228 studies to as few as 50 when we combined specific terms. We also used government websites to collect statistical data as well as to identify guidelines for pregnant and postpartum women with regard to tobacco use. The following characteristics of studies are included in Figure 1: author (year), sample size/location, intervention(s), measures, relapse rates, and predictors of relapse.

Figure 1.

Studies, interventions, measures, relapse rates, and predictors of relapse for postpartum smoking

aMorasco BJ, Dornelas EA, Fischer EH, Oncken C, Lando HA. Spontaneous smoking cessation during pregnancy among ethnic minority women: a preliminary investigation. Addict Behav 2006;31:203-10.

bPolanska K, Hanke W, Sobala W. Smoking relapse one year after delivery among women who quit smoking during pregnancy. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 2005;18:159-65.

cSockrider MM, Hudmon KS, Addy R, Dolan Mullen P. An exploratory study of control of smoking in the home to reduce infant exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Nicotine Tob Res 2003;5:901-10.

dVan't Hof SM, Wall MA, Dowler DW, Stark MJ. Randomised controlled trial of a postpartum relapse prevention intervention. Tob Control 2000;9(Suppl 3):III64-6.

eHajek P, West R, Lee A, Foulds J, Owen L, Eiser JR, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a midwife-delivered brief smoking cessation intervention in pregnancy. Addiction 2001;96:485-94.

fJohnson JL, Ratner PA, Bottorff JL, Hall W, Dahinten S. Preventing smoking relapse in postpartum women. Nurs Res 2000;49:44-52.

gRatner PA, Johnson JL, Bottorff JL, Dahinten S, Hall W. Twelve-month follow-up of a smoking relapse prevention intervention for postpartum women. Addict Behav 2000;25:81-92.

hMcBride CM, Curry SJ, Lando HA, Pirie PL, Grothaus LC, Nelson JC. Prevention of relapse in women who quit smoking during pregnancy. Am J Public Health 1999;89:706-11.

iWall MA, Severson HH, Andrews JA, Lichtenstein E, Zoref L. Pediatric office-based smoking intervention: impact on maternal smoking and relapse. Pediatrics 1995;96(4 Pt 1):622-8.

jSeverson HH, Andrews JA, Lichtenstein E, Wall M, Akers L. Reducing maternal smoking and relapse: long-term evaluation of a pediatric intervention. Prev Med 1997;26:120-30.

kSecker-Walker RH, Solomon LJ, Flynn BS, Skelly JM, Lepage SS, Goodwin GD, et al. Smoking relapse prevention counseling during prenatal and early postnatal care [published erratum appears in Am J Prev Med 1996;12:71-2]. Am J Prev Med 1995;11:86-93.

SHS = secondhand smoke

CO = carbon monoxide

ppm = parts per million

MOMS = modification of maternal smoking

ng/ml = nanograms per milliliter

We only reviewed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that clearly identified postpartum relapse prevention in their title or purpose. The selected studies also had to describe an educational intervention addressing SHS in the home. Another key element for study inclusion was the timing of the intervention. The intervention targeted women during the postpartum period who had quit smoking before or during pregnancy. All studies included in the final review had to include a six- and/or 12-month point prevalence, and had to be published in English. Ultimately, we chose nine trials for this critical review; two trials had further long-term evaluations published after the original study was completed.3,16,18,19 A total of 11 studies are summarized in Figure 1.

Operational definition of SHS

SHS or passive smoke is defined as the “smoke inhaled by an individual not actively engaged in smoking but due to exposure to ambient tobacco smoke.”20 SHS consists of two components: sidestream smoke and mainstream smoke. Sidestream smoke refers to the smoke emitted from the burning end of tobacco products, while mainstream smoke refers to the smoke exhaled by smokers.

Recruitment criteria

Recruitment criteria for the selected studies was varied. Four of the seven studies initially enrolled both ex-smokers and current smokers. Three studies excluded participants who were current smokers at enrollment and did not quit during pregnancy and/or were smoking at the postpartum enrollment period.3,19,21 The remaining studies had differing smoking status requirements for inclusion. These studies required that the pregnant smoker had already achieved abstinence for a specified period of time. Women who were abstinent for a month (30 days) or 28 days were deemed eligible for inclusion. In addition to the abstinence period, studies varied regarding the timing of recruitment. Two studies specified enrollment periods based on the woman's gestational age: the 20th week of gestation17 and the 28th week of gestation.22 Two studies enrolled subjects in their first trimester,21,23 while Ratner et al. recruited women upon admission to labor and delivery.18 Mothers were also recruited during postpartum hospitalization24 and at their infant's first pediatric visit.3

RESULTS

Study sample characteristics

In the reviewed studies, participants generally were in their mid-20s, Caucasian, employed, married or living with a partner, and had achieved at least a high school education. Most participants recruited for the RCTs lived in the northern United States (e.g., Oregon, Washington, and Minnesota), with the exception of one study that took place in England21 (Figure 1). The postpartum period in the selected studies ranged from the first six weeks to one year following birth. Sample sizes ranged from 33 to 2,901 participants. One study did not report age of participants, but rather the age at which the women started smoking. In this study, the reported mean age of initiation was approximately 16 years.23 Of the nine studies reviewed, Sockrider et al.17 recruited the largest pool of nonwhite participants (27%).

Measurement of abstinence, relapse, and SHS

Although most researchers clearly defined smoking status upon enrollment, they often differed in the conceptual and operational definitions of relapse and abstinence (Figure 2). To add to this complexity, abstinence measures and terminology often differ across types of interventions and study populations. This is also true of postpartum relapse research. Historically, relapse described a phenomenon or a medical condition that had returned, such as cancer or a fever.25 Relapse in the postpartum smoking literature is typically defined as any return to smoking, “even a puff.”26,27 Relapse has also been synonymous with the term “lapse” in tobacco abstinence literature.28

Figure 2.

Definitions of smoking relapse, abstinence, and biomarker validation

aMorasco BJ, Dornelas EA, Fischer EH, Oncken C, Lando HA. Spontaneous smoking cessation during pregnancy among ethnic minority women: a preliminary investigation. Addict Behav 2006;31:203-10.

bBiochemically validated postpartum abstinence

cVan't Hof SM, Wall MA, Dowler DW, Stark MJ. Randomised controlled trial of a postpartum relapse prevention intervention. Tob Control 2000;9(Suppl 3):III64-6.

dHajek P, West R, Lee A, Foulds J, Owen L, Eiser JR, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a midwife-delivered brief smoking cessation intervention in pregnancy. Addiction 2001;96:485-94.

eJohnson JL, Ratner PA, Bottorff JL, Hall W, Dahinten S. Preventing smoking relapse in postpartum women. Nurs Res 2000;49:44-52.

fRatner PA, Johnson JL, Bottorff JL, Dahinten S, Hall W. Twelve-month follow-up of a smoking relapse prevention intervention for postpartum women. Addict Behav 2000;25:81-92.

gWall MA, Severson HH, Andrews JA, Lichtenstein E, Zoref L. Pediatric office-based smoking intervention: impact on maternal smoking and relapse. Pediatrics 1995;96(4 Pt 1):622-8.

hSeverson HH, Andrews JA, Lichtenstein E, Wall M, Akers L. Reducing maternal smoking and relapse: long-term evaluation of a pediatric intervention. Prev Med 1997;26:120-30.

iSecker-Walker RH, Solomon LJ, Flynn BS, Skelly JM, Lepage SS, Goodwin GD, et al. Smoking relapse prevention counseling during prenatal and early postnatal care [published erratum appears in Am J Prev Med 1996;12:71-2]. Am J Prev Med 1995;11:86-93.

NR = not reported

CO = carbon monoxide

ppm = parts per million

ng/mg = nanograms per milliliter

Recently, there has been increased interest in the differentiation of abstinence terminology in tobacco abstinence research.25,29–32 In these studies, a “lapse” accounts for an instance of smoking, while “relapse” generally refers to a return to baseline smoking, or a resumption of smoking at least five cigarettes for three consecutive days. In this context, a lapse is considered a temporary event, while a relapse indicates a more permanent condition. Choice of abstinence terminology is an important consideration in research design. Frequently, women view the term “relapse” in a negative context or as a failure, but may not necessarily view “lapse” this way.9,33 Smokers who experienced a lapse during the study period were less likely to achieve abstinence.26

Measurement of abstinence, home smoking, and SHS exposure

The Society for Research on Nicotine recommends that clinical trials report multiple measures of abstinence.30 Minimally, a prolonged or sustained abstinence, point prevalence as a second measure, and a guideline of seven consecutive days of smoking or smoking on at least one day of two consecutive weeks to define relapse are recommended.27 Abstinence measures were frequently defined as not smoking, even a puff, in the past seven days.3,17 McBride et al. further differentiated abstinence into three postpartum outcomes: postpartum cessation, postpartum relapse, and postpartum seven-day prevalent abstinence.22 Self-report of postpartum smoking abstinence was primarily defined as no smoking in the seven days prior to follow-up or no return to smoking in the six months or a year following delivery.10,16

Self-reported abstinence is not often a reliable measure with pregnant and postpartum women.31 For social desirability reasons, many pregnant women underreport their smoking status9 and extent of SHS exposure.34 Biomarker validation is recommended to confirm smoking and SHS exposure in this population. Biomarkers can be used to identify the extent of exposure and/or consumption of tobacco. The most popular biomarkers for quantifying maternal SHS exposure during pregnancy include saliva, serum, expired carbon monoxide (CO), urine or hair cotinine, and hair nicotine.

Seven of the nine studies biochemically validated smoking status upon enrollment, while only three studies performed additional biochemical validation of smoking status during postpartum14,17,20 (Figure 2). Expired CO and salivary or urinary cotinine were the most used biomarkers to validate smoking status. Johnson et al. defined and confirmed abstinence when participants reported not smoking any cigarettes for six or 12 months, and if their expired CO level was <10 parts per million (ppm).16 Secker-Walker et al. defined abstinence as no report of smoking and cotinine/creatinine ratio <80 nanograms per milliliter.23 Another study used self-report of no smoking for seven days and salivary cotinine to define abstinence.22 Although biomarker validation has repeatedly been cited as a reliable measure of tobacco use, clinicians reported anxiety in confronting patients with biomarker feedback.35

Biomarker validation of home smoking and SHS was primarily measured by self-report (survey), passive nicotine monitors,17 and hair nicotine levels.36 Sockrider et al. found a significant association between home nicotine monitors and self-report of SHS exposure in the home at six and 12 months (r=0.53; r=0.55; both p-values <0.0001).17 A survey questionnaire in one study assessed postpartum mothers' knowledge and attitudes regarding the health effects of passive smoking and environmental tobacco smoke.19

SHS interventions and postpartum relapse

In the selected studies, part or all of the intervention was delivered during the postpartum period. The interventions varied among studies, but all incorporated an educational component on the health effects of SHS in the home. The SHS intervention was often limited to written materials via a handout, pamphlet, video, or booklet describing an array of postpartum information ranging from health effects of SHS and tips on staying smoke-free, to tips on maintaining a smoke-free home. No study focused solely on the impact of SHS on postpartum relapse. Sockrider et al. designed an intervention to reduce postpartum relapse and home exposure to SHS that included (1) education regarding health effects of SHS and effects of a home smoking policy, and (2) specific newsletters/video for significant others at two time points.17 Another study examined a partner-focused intervention in which the partner/spouse received an educational letter by mail.19

We examined three other interventional characteristics: timing and duration, delivery personnel, and intensity. Although the majority of studies included an intervention both during and after pregnancy, timing varied. Interventions conducted during pregnancy began as early as the first prenatal visit (first trimester of pregnancy) to as late as 28 weeks gestation (third trimester). Postpartum interventions occurred from as early as 24 hours following delivery (while the mother was hospitalized) to six weeks after delivery, and then two, four, and/or six months after delivery. Regardless of onset, all studies concluded at either six or 12 months following delivery.

Personnel delivering the intervention varied among studies. Counseling interventions were primarily conducted by nurses, although pediatricians, training abstinence counselors, and research assistants were also used. Counseling by a nurse/midwife or pediatrician did not appear to have a significant impact on relapse rates when compared with trained abstinence counselors or research assistants.3,16

All study interventions included counseling and educational materials regarding the adverse effects of smoking and SHS exposure; however, mode of delivery differed. Pamphlets, videos, newsletters, no-smoking signs, and self-help booklets were used. Telephone and individual counseling sessions ranged from 10 minutes to one hour in length. Postpartum contact ranged from two to eight times, with the longest postpartum session lasting 90 minutes.37

Regardless of intervention intensity, relapse rates were consistently high at the six- and 12-month postpartum period. Relapse rates ranged from 42% to 77% at the six-month period to 57% to 79% at the 12-month period. McBride et al.22 and Van't Hof et al.24 demonstrated the lowest relapse rates at the six-month assessment. The studies had two similarities: (1) nurses were used to deliver the first counseling session, and (2) intervention implementation occurred at least three times within the first four months following delivery. McBride et al. included three postpartum telephone counseling sessions within the first four months postpartum, while Van't Hof et al. reinforced abstinence from a pediatric provider at well-baby visits three times within the first four months postpartum. Four studies also reported long-term relapse rates at 12 months. Of these studies, McBride reported the lowest return to smoking (57%).

Predictors of postpartum relapse related to SHS

Peer-reviewed research on predictors of postpartum relapse encompasses an array of biobehavioral, psychosocial, and socioeconomic variables. In the review, the most commonly cited factors that influenced pre/postnatal smoking behavior and home SHS exposure included age, education, income, spontaneous quitting, husband or partner smoking, depression, self-efficacy, motivation or confidence to quit, and home smoking restrictions. Secker-Walker et al. was the only study to specify “longest time abstinent before first prenatal visit” to be a predictor of relapse.23 Polanska et al. reported a threefold lower relapse in spontaneous quitters.38 Although socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, depressive symptoms, and level of addiction certainly influence relapse, this article focuses on three predictors that link prenatal and postpartum SHS exposure to postpartum relapse: (1) having a husband or partner smoking in the home, (2) adoption of home smoking restrictions, and (3) motivation/confidence or self-efficacy to remain abstinent.

The smoking behavior of the woman's partner has consistently been cited as a strong predictor of postpartum smoking relapse.3,10 Women who lived with another smoker were four times more likely to relapse than those who did not live with a smoker.4 In another study, only 8.4% of mothers who maintained abstinence through the 12-month assessment had husbands who smoked, compared with 20.8% of mothers with nonsmoking husbands.3 Van't Hof et al. also reported significantly higher relapse rates for those women who reported a greater number of smokers among family and friends.24 One year following birth, women with smoking partners were 1.8 times more likely to be daily smokers than those with partners who remained abstinent or were occasional smokers.18

Three of the nine studies examined the impact of having a home smoking policy or home smoking restrictions on postpartum relapse.3,17,22 Having a smoke-free policy in the home was defined as not having the mother, her partner, other household members, or visitors smoke in the home and was a significant predictor of intention to quit smoking in the next six months. Women living in smoke-free homes also could prolong time to relapse following abstinence.39 Implementing a smoke-free policy at the six-month postpartum assessment was significantly associated with increased abstinence.17 Two studies posted “no smoking” signs in the home to assist mothers in maintaining a smoke-free environment.17,19

Motivation and confidence to quit smoking during pregnancy is typically high,16,23 but it is not a consistent predictor of smoking abstinence. Johnson et al. found that approximately 90% of mothers who quit smoking during pregnancy intended to remain smoke-free postpartum.16 A mother's confidence in her ability to control smoking in the home is also a significant factor in controlling infant's SHS exposure.17 Hajek et al. reported an early association between a mother's desire to quit smoking, nicotine dependence, and abstinence up to birth.21 We examined self-efficacy and confidence to achieve abstinence in all studies, but they were not shown to be consistent predictors of relapse. Van't Hof et al. reported that a mother's level of confidence to stay abstinent significantly affected relapse rates.24 In another study, self-efficacy significantly predicted postpartum relapse at three months, but was not a reliable predictor during the six- to 12-month period.16,18 Secker-Walker et al. reported that a woman's level of belief that smoking is harmful to the fetus predicts relapse; however, this belief was not associated with her motivation and confidence to remain abstinent.23

Differentiating among the terms “lapse,” “relapse,” and “abstinence” may offer postpartum women opportunities for short-term success and lessen the despair they feel with relapse.9,39,40 Despite the terminology debate, self-report has been a popular determinant of abstinence and relapse; however, many researchers use biomarker validation of self-reported abstinence.

DISCUSSION

During the past two decades of research, interventions tested in RCTs during and after pregnancy have not resulted in prolongation and/or an increase in postpartum abstinence rates. Unfortunately, many studies fail to include a six-month and/or 12-month point prevalence. The vast majority of mothers who quit smoking during pregnancy intend to remain smoke-free postpartum; however, smoking abstinence interventions repeatedly failed to achieve postpartum smoking abstinence.16,23 In the selected studies, pre/postpartum education content regarding SHS was offered using a variety of methods; however, no study tested a comprehensive SHS educational intervention. SHS interventions were typically limited to written educational resources (e.g., pamphlets, mailings, and home no-smoking signs). Of the studies that examined postpartum relapse and SHS interventions, most agreed that increased relapse rates were associated with partner smoking, low self-efficacy or confidence to remain abstinent, and home exposure to SHS. Interventions that failed to address home exposure to SHS during the postpartum period may have contributed to high relapse rates.

It is challenging to analyze postpartum relapse research due to varied definitions of abstinence/relapse terminology, differing biomarkers to confirm abstinence/relapse, lack of postpartum biomarker confirmation of abstinence, and inconsistent timing of postpartum interventions. Standardized abstinence terminology and abstinence measures are needed to advance quality postpartum tobacco abstinence research. Confirmation of abstinence is best achieved when self-report measures are validated with biomarkers both during enrollment and at all points during follow-up. In the two studies that reported the lowest relapse rates, nurses or pediatricians delivered the intervention at least three times within the first four postpartum months.

Achieving abstinence is important not only during pregnancy, but also during the postpartum period to reduce SHS exposure in the home. Approximately one-half to two-thirds of all children in the U.S. younger than age 5 are at risk of home exposure to SHS.10 Active smokers and those exposed to SHS inhale the same smoke constituents and are likely to incur similar health-related effects. To ensure the health of women of childbearing age, their children, and their families, future studies need to test interventions designed for the postpartum period.41 Additional research is needed to test long-term interventions beyond the first six months postpartum. Generally, there has been limited research on home exposure to SHS and postpartum relapse. By prohibiting smoking in the home, SHS can be greatly reduced, if not eliminated, and relapse rates can also be reduced. A comprehensive intervention that specifically prioritizes parental education on the health effects of SHS on the family, empowerment of the mother and family members to remain abstinent and adopt a smoke-free home smoking policy, and partner influence on smoking could result in a significant reduction in postpartum relapse rates. Lastly, social pressures have influenced many to view smoking during pregnancy in a negative context; however, this effect is often diminished after the birth of the infant.

Health-care professional-led interventions should also incorporate the five As (ask, advise, assess, assist, and arrange) tool, a 5- to 15-minute brief counseling tool that addresses smoking during pregnancy. This counseling tool is offered in a variety of settings (e.g., obstetrician/gynecologist offices, pediatric offices, and family medicine clinics) and is endorsed by multiple health-care professional organizations, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Academy of Pediatrics, and the March of Dimes. Consistent and repeated use of the evidence-based tool coupled with information on the adverse health effects of home exposure to SHS could greatly extend the negative social effects of smoking during pregnancy far beyond birth and become a long-term motivator for families to adopt a smoke-free home policy.

Limitations

Homogeneity of the study participants posed a significant limitation to the generalizability of the findings from the reviewed studies. The majority of the selected studies recruited Caucasian participants as the vast majority of their participants.17,19,22,24 Three studies did not report ethnicity.16,21,23 Unclear or unstated definitions of abstinence, relapse, lapse, and postpartum abstinence caused confusion when comparing postpartum relapse rates across studies. We found methodological differences across all studies. SHS educational interventions were not clearly defined and may have been limited to a pamphlet, newsletter, or handout.

CONCLUSION

Future research is needed to examine SHS exposure and postpartum relapse, including (1) targeting a multiethnic population, (2) focusing on best practices for SHS measurement (urinary and saliva cotinine, hair nicotine, expired CO, and home monitoring devices), (3) exploring maternal views on biomarker validation and choice of terminology (lapse vs. relapse), (4) including a family-based comprehensive SHS educational intervention that is not limited to written materials, and (5) frequent reinforcement of the content during the first four months following delivery. Although timing of the intervention and choice of personnel did not significantly influence postpartum relapse rates, studies using nurse- and pediatrician-led interventions resulted in the lowest relapse rates.

Footnotes

This study was completed in part by a United States Public Health Service grant supporting the University of Kentucky General Clinical Research Center #M01RR02602.

This article was made possible by grant #K12DA14040 from the Office of Women's Health Research and the National Institute on Drug Abuse at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIH.

REFERENCES

- 1.Crawford MA, Woodby LL, Russell TV, Windsor RA. Using formative evaluation to improve a smoking cessation intervention for pregnant women. Health Commun. 2005;17:265–81. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1703_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Windsor R. Smoking cessation or reduction in pregnancy treatment methods: a meta-evaluation of the impact of dissemination. Am J Med Sci. 2003;326:216–22. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200310000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Severson HH, Andrews JA, Lichtenstein E, Wall M, Akers L. Reducing maternal smoking and relapse: long-term evaluation of a pediatric intervention. Prev Med. 1997;26:120–30. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.9983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahn RS, Certain L, Whitaker RC. A reexamination of smoking before, during, and after pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1801–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smoking during pregnancy—United States, 1990–2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(39):911–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheibmeir M, O'Connell KA. In harm's way: childbearing women and nicotine. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1997;26:477–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1997.tb02730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ershoff DH, Quinn VP, Mullen PD. Relapse prevention among women who stop smoking early in pregnancy: a randomized clinical trial of a self-help intervention. Am J Prev Med. 1995;11:178–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fingerhut LA, Kleinman JC, Kendrick JS. Smoking before, during, and after pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:541–4. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.5.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bottorff JL, Johnson JL, Irwin LG, Ratner PA. Narratives of smoking relapse: the stories of postpartum women. Res Nurs Health. 2000;23:126–34. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(200004)23:2<126::aid-nur5>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Office of the Surgeon General (US) Washington: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center on Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health (US); 2006. The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: a report of the Surgeon General. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solomon L, Quinn V. Spontaneous quitting: self-initiated smoking cessation in early pregnancy. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(Suppl 2):S203–16. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001669132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bullock L, Everett KD, Mullen PD, Geden E, Longo DR, Madsen R. Baby BEEP: a randomized controlled trial of nurses' individualized support for poor rural pregnant smokers. Matern Child Health J. 2008 May 22; doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0363-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lumley J, Oliver SS, Chamberlain C, Oakley L. Interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(issue 4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001055.pub2. CD001055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Office of the Surgeon General (US). Women and smoking: a report of the Surgeon General. Washington: Department of Health and Human Services (US); 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lowdermilk DL, Perry SE, Piotrowski KA. Maternity nursing. 6th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2003. Genetics, conception, and fetal development. In: Lowdermilk DL, Perry SE, editors; pp. 576–84. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson JL, Ratner PA, Bottorff JL, Hall W, Dahinten S. Preventing smoking relapse in postpartum women. Nurs Res. 2000;49:44–52. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200001000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sockrider MM, Hudmon KS, Addy R, Dolan Mullen P. An exploratory study of control of smoking in the home to reduce infant exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5:901–10. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001615240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ratner PA, Johnson JL, Bottorff JL, Dahinten S, Hall W. Twelve-month follow-up of a smoking relapse prevention intervention for postpartum women. Addict Behav. 2000;25:81–92. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wall MA, Severson HH, Andrews JA, Lichtenstein E, Zoref L. Pediatric office-based smoking intervention: impact on maternal smoking and relapse. Pediatrics. 1995;96(4 Pt 1):622–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klerman L. Protecting children: reducing their environmental tobacco smoke exposure. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(Suppl 2):S239–53. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001669213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hajek P, West R, Lee A, Foulds J, Owen L, Eiser JR, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a midwife-delivered brief smoking cessation intervention in pregnancy. Addiction. 2001;96:485–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96348511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McBride CM, Curry SJ, Lando HA, Pirie PL, Grothaus LC, Nelson JC. Prevention of relapse in women who quit smoking during pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:706–11. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.5.706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Secker-Walker RH, Solomon LJ, Flynn BS, Skelly JM, Lepage SS, Goodwin GD, et al. Smoking relapse prevention counseling during prenatal and early postnatal care. Am J Prev Med. 1995;11:86–93. [published erratum appears in Am J Prev Med 1996;12:71-2] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van't Hof SM, Wall MA, Dowler DW, Stark MJ. Randomised controlled trial of a postpartum relapse prevention intervention. Tob Control. 2000;9(Suppl 3):III64–6. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.suppl_3.iii64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simonelli MC. Relapse: a concept analysis. Nurs Forum. 2005;40:3–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2005.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Curry SJ, McBride C, Grothaus L, Lando H, Pirie P. Motivation for smoking cessation among pregnant women. Psychol Addict Behav. 2001;15:126–32. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.2.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chalmers K, Gupton A, Katz A, Hack T, Hildes-Ripstein E, Brown J, et al. The description and evaluation of a longitudinal pilot study of a smoking relapse/reduction intervention for perinatal women. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45:162–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wileyto P, Patterson F, Niaura R, Epstein L, Brown R, Audrain-McGovern J, et al. Do small lapses predict relapse to smoking behavior under bupropion treatment? Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:357–66. doi: 10.1080/1462220042000202463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Zvolensky MJ. Distress tolerance and early smoking lapse. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25:713–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5:13–25. [published erratum appears in Nicotine Tob Res 2004;6:863-4] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buchanan L. Implementing a smoking cessation program for pregnant women based on current clinical practice guidelines. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2002;14:243–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2002.tb00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shiffman S, Balabanis MH, Paty JA, Engberg J, Gwaltney CJ, Liu KS, et al. Dynamic effects of self-efficacy on smoking lapse and relapse. Health Psychol. 2000;19:315–23. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.4.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marlatt GA. Taxonomy of high-risk situations for alcohol relapse: evolution and development of a cognitive-behavioral model. Addiction. 1996;91(Suppl):S37–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeLorenze GN, Kharrazi M, Kaufman FL, Eskenazi B, Bernert JT. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in pregnant women: the association between self-report and serum cotinine. Environ Res. 2002;90:21–32. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2001.4380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaffney KF, Baghi H, Zakari NM, Sheehan SE. Postpartum tobacco use: developing evidence for practice. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2006;18:71–9. xii–xiii. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al-Delaimy WK, Crane J, Woodward A. Is the hair nicotine level a more accurate biomarker of environmental tobacco smoke exposure than urine cotinine? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56:66–71. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.1.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morasco BJ, Dornelas EA, Fischer EH, Oncken C, Lando HA. Spontaneous smoking cessation during pregnancy among ethnic minority women: a preliminary investigation. Addict Behav. 2006;31:203–10. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Polanska K, Hanke W, Sobala W. Smoking relapse one year after delivery among women who quit smoking during pregnancy. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2005;18:159–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gilpin EA, White MM, Farkas AJ, Pierce JP. Home smoking restrictions: which smokers have them and how they are associated with smoking behavior. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1:153–62. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hendershot CS, Marlatt GA, George WH. Relapse prevention and the maintenance of optimal health. In: Shumaker SA, Ockene JK, Riekert KA, editors. The handbook of health behavior change. 3rd ed. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2008. pp. 127–50. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mullen PD, Quinn VP, Ershoff DH. Maintenance of nonsmoking postpartum by women who stopped smoking during pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:992–4. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.8.992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]