SYNOPSIS

Objective

The Alaska Division of Public Health has stated that infants may safely share a bed for sleeping if this occurs with a nonsmoking, unimpaired caregiver on a standard, adult, non-water mattress. Because this policy is contrary to recent national recommendations that discourage any bed sharing, we examined 13 years of Alaskan infant deaths that occurred while bed sharing to assess the contribution of known risk factors.

Methods

We examined vital records, medical records, autopsy reports, and first responder reports for 93% of Alaskan infant deaths that occurred between 1992 and 2004. We examined deaths while bed sharing for risk factors including sleeping with a non-caregiver, prone position, maternal tobacco use, impairment of a bed-sharing partner, and an unsafe sleep surface. We used Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System data to describe bed-sharing practices among all live births in Alaska during 1996–2003.

Results

Thirteen percent (n=126) of deaths occurred while bed sharing; 99% of these had at least one associated risk factor, including maternal tobacco use (75%) and sleeping with an impaired person (43%). Frequent bed sharing was reported for 38% of Alaskan infants. Among these, 60% of mothers reported no risk factors; the remaining 40% reported substance use, smoking, high levels of alcohol use, or most often placing their infant prone for sleeping.

Conclusions

Almost all bed-sharing deaths occurred in association with other risk factors despite the finding that most women reporting frequent bed sharing had no risk factors; this suggests that bed sharing alone does not increase the risk of infant death.

Unsafe sleep environments increase the risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) and other causes of sudden unexpected infant deaths.1,2 Some research has suggested that unsafe sleep environments for infants include sharing a sleep surface (bed sharing).3–7 Bed sharing may lead to suffocation by the larger person accidentally overlying the infant or pushing the infant into a dangerous location, such as between the mattress and bed frame or wall. In response to a continued high national SIDS incidence, a halt in the decline in postneonatal mortality rates, and several recent studies concluding that bed sharing increases the risk of infant death, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) released a policy statement in 2005 recommending that infants not share a sleep surface with adults or other children.8

The studies supporting the AAP recommendation, though, had several limitations. Many had no data on important risk factors for SIDS, such as parental smoking and infant sleep position.6,9–11 Others that adjusted for known risk factors found an increased risk only in certain situations, such as bed sharing by people other than the parent(s),4 or bed sharing with infants younger than 8 or 11 weeks of age.3,5 The policy implications of the latter two studies were weakened by a small odds ratio for one5 and a large confidence interval for the other.3 Other studies cited by the AAP found no independent risk associated with bed sharing after adjusting for tobacco use.12–14 Consequently, some authors have criticized the AAP's recommendation against all bed sharing.15–17 Since completing a comprehensive review in 2000 of Alaskan infant deaths, the Alaska Division of Public Health (ADPH) has recommended that infants sleep in the supine position and either in an infant crib or with a nonsmoking, unimpaired caregiver on an adult, non-water mattress.18

Data from the Alaska Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) indicate that the prevalence of infants who always or almost always share a bed increased from 33% of births in 1996 to 43% in 2005.19 The frequent occurrence of bed sharing in Alaska, in combination with the AAP policy statement recommending no bed sharing, led to the current evaluation to determine whether Alaska's policy needed modification. Our goals were to (1) determine the frequency of Alaskan infant deaths occurring while bed sharing and (2) evaluate the presence of known risk factors associated with these deaths to determine whether bed sharing was contributing independently to infant mortality in Alaska.

METHODS

The Maternal-Infant Mortality Review (MIMR) has coordinated ongoing retrospective committee reviews of all Alaskan-resident infant deaths since 1992. At the time of the current study, the MIMR committee had reviewed 891 infant deaths; 95% of the deaths occurred from 1992 through 2004 (99% of Alaskan infant deaths occurring from 1992 through 2002, 81% of deaths occurring in 2003, and 24% of deaths occurring in 2004). Case files comprised birth and death certificates, maternal and infant medical records, autopsy reports, first responder reports, and any existing child protective services reports or public health nurse home interviews. At review sessions, three or four medical experts reviewed each file and came to a consensus decision regarding what they believed were the most probable and contributing causes of death.

We included two categories of deaths in the current analysis: (1) MIMR committee or death certificate report of SIDS or asphyxia as the cause of death and (2) any case with a report that death occurred during sleep, regardless of assigned cause. We did not include deaths not yet reviewed by the committee because these usually did not have complete information available. For deaths that met our criteria, we used a standard data abstraction tool to collect further details from the MIMR case files. For those that occurred in association with bed sharing, we ascertained the presence of five risk factors:

Position: Infant was put to sleep prone (or found prone only if no information was available on position in which infant was put to sleep).

Non-caregiver: Infant was sleeping with someone who was not the primary person responsible for the infant's care at the time of death, including those sleeping with a caregiver and other people.

Maternal tobacco use: Either prenatal or postnatal cigarette or chew use by the mother was reported in any of the records available.

Impairment of bed-sharing partner: Infant was sleeping with any person impaired by alcohol, tobacco, or other drug use at the time of death.

Surface: Infant was sleeping on a sofa or water bed.

To compare demographic characteristics of infant deaths while bed sharing with all infant deaths, we used a dataset of linked birth and death certificate records for all Alaskan infant deaths from 1992 to 2004, provided by the Alaska Bureau of Vital Statistics.

PRAMS is an ongoing population-based randomized surveillance system that samples approximately 18% of Alaskan mothers of newborns two to six months after a live birth. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) designed the PRAMS sampling, implementation, and weighting methodologies, which are described elsewhere.20,21 From 1996 through 2003, there were approximately 79,912 Alaskan births; 14,777 (18.5%) were sampled for PRAMS, and 11,837 mothers responded to a mail or phone survey (response rate = 80.1%). The mean infant age at the time the mother responded was 3.2 months (range: 2.2–9.9). We compared weighted proportions of selected demographic characteristics of survey respondents with all births in Alaska on an annual basis to ensure the sample was representative. For example, survey respondents compared with all births in 2003 were similar on examined characteristics, including maternal education <12 years (14.2% vs. 14.3%), Alaska Native race (25.0% vs. 24.4%), unmarried status (35.2% vs. 34.3%), and low birthweight birth (5.1% vs. 5.1%).

During birth years 1996–1999, Alaska PRAMS asked women, “How often does your new baby sleep in the same bed with you?” During 2000–2004, the question was modified to, “How often does your new baby sleep in the same bed with you or anyone else?” We identified frequent bed sharing by responses of always or almost always, and infrequent bed sharing by responses of sometimes, rarely, or never (rarely was not a response option during 1996–1999). We linked PRAMS data to birth certificates for 10,860 respondents who had non-missing data for the question about bed-sharing habits. This question was designed to be skipped by women whose infants were not living with them at the time they responded to the survey. Among respondents with missing data on bed sharing (n=703), 16.4% reported that their infant had died before they completed the survey. We analyzed PRAMS data using SPSS® Version 16.022 to adjust for the survey design.

We used PRAMS data to examine background population prevalences of certain risk factors of interest among all births and among women whose infants frequently bed share. Risk factors on PRAMS included maternal cigarette smoking habits currently and during the last three months of pregnancy, prenatal smokeless tobacco or chew use, prenatal marijuana use, number of alcoholic drinks in an average week during the three months before pregnancy and currently, and the position in which the infant was most often laid down to sleep. We combined information on prenatal or current smoking on PRAMS with smoking reported on the birth certificate to create a single smoking risk factor category, and combined PRAMS or birth certificate reports of prenatal smokeless tobacco use to create a single chew risk factor category. To measure the prevalence of women who may have consumed some alcohol every day, we assigned women who drank seven or more drinks per week into the category of daily drinker.

The MIMR records and PRAMS data used for this study were collected by ongoing surveillance programs of ADPH. An employee with legal access to these data for the purpose of developing public health recommendations conducted all analyses. Thus, no institutional review board (IRB) approval or review was sought or obtained for this study. Alaska PRAMS is reviewed annually by IRBs at CDC and the University of Alaska Anchorage.

RESULTS

Population characteristics

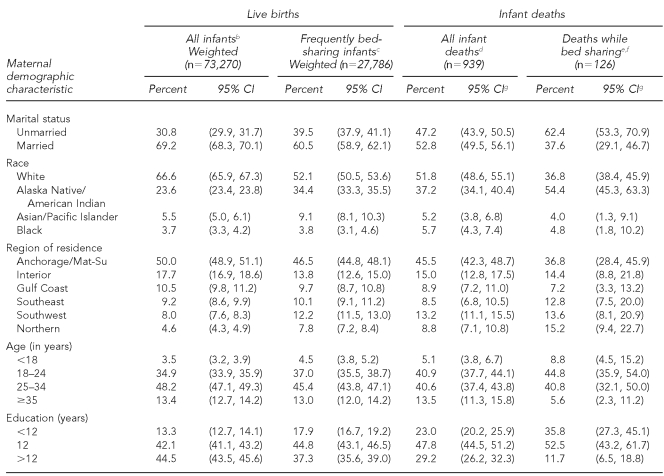

We first examined maternal demographic information for four populations of interest during the study period: all live births, infants whose mothers reported that they always or almost always shared a bed, all infant deaths, and infant deaths that occurred while bed sharing (Table 1). Because data sources differed for each population, we were unable to perform statistical tests of differences; however, we did observe variations in point estimates. Differences were most pronounced when comparing all live births with infants who died while bed sharing, with the latter group having a higher prevalence of mothers who were unmarried, Alaska Native, residents of Southwest or Northern Alaska, young, and less educated. The maternal characteristics of infants who always or almost always shared a bed were similar to those of all live births, but differed from those of infants who died while bed sharing.

Table 1.

Distribution of selected maternal demographic characteristics with 95% CIs among Alaskan live births, 1996–2003, and infant deaths, 1992–2004a

aBased on data from the Alaska PRAMS, BVS, and MIMR

bPrevalences calculated using weighted PRAMS data for women delivering during 1996–2003 whose infant was living with them at the time they responded to the PRAMS survey.

cPrevalences calculated using weighted PRAMS data for women delivering during 1996–2003 who responded that their infant always or almost always slept in the same bed with the mother or anyone else. During 1996–1999, the survey question did not include the phrase or anyone else.

dData provided by the Alaska BVS

eData provided by the Alaska MIMR

fAbout 81% of 2003 and 24% of 2004 infant deaths had been reviewed by the MIMR committee at the time of this study. Of 1992–2002 infant deaths, 15% (n=45) did not have bed-sharing data available. Thus, some deaths while bed sharing may not have been included.

gExact binomial CIs

CI = confidence interval

PRAMS = Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System

BVS = Bureau of Vital Statistics

MIMR = Maternal-Infant Mortality Review

Risk factors among all infants

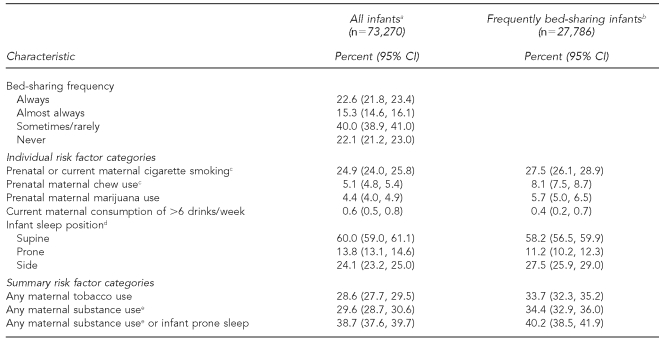

Data from PRAMS indicated that among infants born in Alaska in 1996–2003, 37.9% (95% confidence interval [CI] 36.9, 38.9) always or almost always shared a bed with their mother or someone else (Table 2). Among women whose infants frequently shared a bed and for whom all relevant data were known, 40.2% (95% CI 38.5, 41.9) reported at least one of the following risk factors: prenatal or current cigarette smoking, prenatal chew use, prenatal marijuana use, current daily drinking, or placing their infant to sleep in the prone position most often. While frequent bed-sharing prevalence increased modestly during the study period, we noted little difference between trends when the analysis was repeated and stratified by women who had at least one risk factor and women with none (data not shown).

Table 2.

Risk factor prevalences among all infants and infants who frequently bed share; Alaska PRAMS, 1996–2003

aPrevalences calculated using weighted PRAMS data for women delivering during 1996–2003 whose infant was living with them at the time they responded to the PRAMS survey.

bPrevalences calculated using weighted PRAMS data for women delivering during 1996–2003 who responded that their infant always or almost always slept in the same bed with the mother or anyone else. During 1996–1999, the survey question did not include the phrase or anyone else.

cIncludes any tobacco use reported on the birth certificate or PRAMS. Prenatal smoking reported on PRAMS includes only the last three months of pregnancy.

dPosition in which infant is most often placed to sleep. About 2% of the total population indicated more than one sleep position; results not shown.

eIncludes any tobacco or marijuana use, or current alcohol consumption of >6 drinks/week.

PRAMS = Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System

CI = confidence interval

Risk factors among infant deaths

Of 891 infant deaths that occurred during 1992–2004 and were available for analysis, we identified 291 (33%) that resulted from SIDS or asphyxia or that occurred during sleep. Of these, 246 (84%) had bed-sharing information available, of which 126 (51%) occurred while bed sharing. These 126 deaths (14% of the 891 deaths reviewed) formed the study group for further analyses.

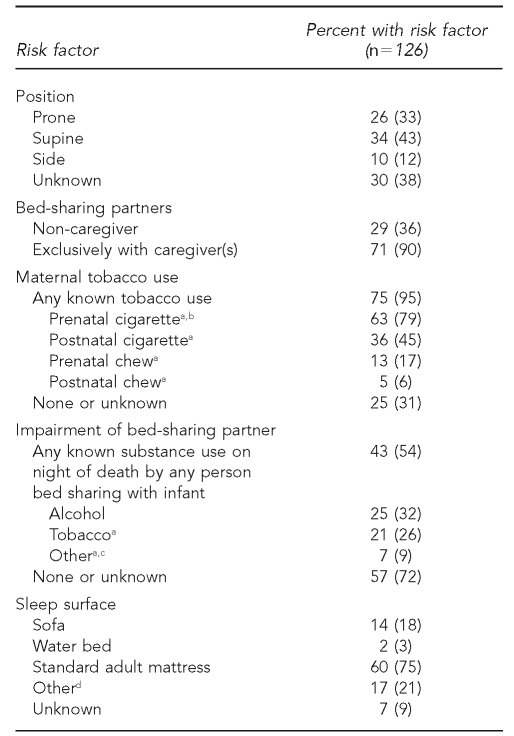

Among the 126 infants who died while bed sharing, we identified 39 (31%) with a single risk factor, 44 (35%) with two risk factors, and 36 (29%) with more than two risk factors. Thus, unlike the data from PRAMS that indicated that the majority of infants who frequently bed shared had no risk factors, 94% of the infants who died while bed sharing had at least one of the five risk factors in our initial evaluation. The most prevalent factor, present in 75% of bed-sharing deaths, was evidence of either prenatal or postnatal maternal tobacco use (Table 3). The second most common, among 43%, was sharing a bed with a person who had documented use of alcohol, tobacco, or other impairment-causing drugs on the night of death. In these cases, impairment from tobacco use was included only if a police report or medical record specifically noted tobacco use on the night of death by the person who was sleeping with the infant. Respondents most frequently noted alcohol consumption, identified in 25% of cases, as causing impairment.

Table 3.

Distribution of risk factors among all infant deaths occurring while bed sharing; Alaska Maternal-Infant Mortality Review, 1992–2004

aSubcategories within risk factor categories were not exclusive.

bPrenatal cigarette use included one mother with prenatal marijuana use, but not tobacco use.

cOther substances causing impairment on the night of death included carbamazepine (used as an anticonvulsant but can cause drowsiness), antidepressants, opiates, tranquilizers, marijuana, and cocaine.

dOther sleep surfaces included the floor, crib, futon sofa or futon bed, makeshift beds of foam pads, a rollout mattress, trailer mattress, and cotton blankets inside a tent on the beach.

Thirty-three (26%) infants slept prone. This category included 18 infants put to sleep prone and 15 with no information on the position in which they were put to sleep but who were found prone. Infants who were found prone but put to sleep supine were not included in the prone sleep risk category.

A total of 110 (87%) infants shared a bed with a caregiver, including 65 with one parent, 40 with both parents, and five with other caregivers. Ninety of these 110 caregiver-infant groups were exclusive of other people, while 20 included non-caregivers (primarily siblings of the infant) (n=17), and were, therefore, identified as high risk. Sixteen additional infants were sleeping with someone other than a caregiver; of these, 14 slept with one or more siblings.

Twenty-one (17%) infants slept on a sofa or water bed at the time of death, while 76 (60%) slept on a standard adult mattress. Other identified sleep surfaces included the floor, crib, futon sofa or futon bed, makeshift beds of foam pads, a rollout mattress, trailer mattress, and cotton blankets inside a tent on the beach.

Seven (6%) cases had none of the risk factors initially considered; however, all but one was associated with additional factors that likely contributed to the deaths. Thus, 99% of the infant deaths had at least one known mortality risk factor. Two of the seven had severe underlying medical illnesses. Four others were exposed to other risk factors, including heavy cigarette smoking in the house by adults other than the mother and unsafe sleep environments (e.g., multiple inappropriate items in the bed or the infant slept on nonstandard sleep surfaces). The final infant was sleeping with an adult who had just returned home from working a night shift, which may have contributed to extreme exhaustion.

DISCUSSION

After reviewing the circumstances of 93% of Alaskan infant deaths that occurred during 1992–2004, we found that 13% of all deaths and 51% of all SIDS, asphyxiation, and sleep-related deaths occurred while the infant was sharing a sleep surface. Despite this high bed-sharing prevalence among infant deaths, our investigation found that bed sharing likely was not an independent risk factor for death. In Alaska, parents commonly share a bed with their infant, with more than a third of mothers of newborns during 1996–2003 indicating on the PRAMS survey that their infant always or almost always slept in the same bed with her or someone else. Sixty percent of women whose infants frequently bed share reported no behaviors known to be associated with increased infant mortality risk; yet, infants of these women were not represented among the deaths because 99% of the bed-sharing deaths occurred in the presence of known infant mortality risk factors. Taken together, these results suggest that infant bed sharing in the absence of other risk factors is not inherently dangerous, and thus do not support a recommendation against all infant bed sharing.

It is likely that some of the infants who died while bed sharing would not have died if they had not shared a bed on the night of death. However, to prevent these deaths, all infants would have had to avoid bed sharing and some of these infants would have died under other circumstances. We do not know if overall mortality would have been reduced if no infants had bed shared. To achieve lower infant mortality, our data indicate that the appropriate risk factors to address are those that contribute to infant death in any sleep environment, specifically prone sleep position and parental substance use.

For this analysis, we focused on risk factors for infant mortality with strong support in the literature. The association between sleep position and SIDS has been described in many studies.1,2,23 Similarly, studies are consistent in demonstrating the danger of infants sleeping with people who are impaired by alcohol or non-tobacco drugs.5,12,13 Sleep surfaces such as a sofa or water bed place infants at risk whether they sleep alone or with another person.4,12,24 The risk associated with other sleep surfaces is unknown, and most likely situation-specific. Studies have consistently associated maternal prenatal tobacco smoking and SIDS,2,25 and have also identified maternal tobacco use as an important confounder of the association between SIDS and bed sharing.4,5,12,13 This confounding could result from the effect of prenatal tobacco exposure on an infant's neuromuscular and cardio-respiratory system development, thereby making the infant more susceptible to asphyxiation when placed in a compromising situation that might occur on an adult bed (e.g., soft bedding, pillows, or heavy blankets).2,6,11 Smoking also affects adult sleep quality, including blunting arousal,26,27 which could make smokers sleeping with an infant less likely to awaken when the infant is in distress.

Other researchers have hypothesized that bed sharing with a smoker leads to passive infant smoke exposure through breathing secondhand smoke or rebreathing expired air from the smoker, which can cause hypoxia.13 The chemical exposure and birth outcomes from maternal prenatal smokeless tobacco use are similar to that of cigarette use,28–30 although we are unaware of any studies that link smokeless tobacco with infant mortality. In Alaska, prenatal chew use occurs primarily among Alaska Native women in the Southwestern region, where prevalence reaches 56% and involves a homemade mixture of tobacco and ash.31,32 The cultural practice of Alaska Native mothers to pre-chew infant food could also provide a mechanism for postnatal exposure to nicotine. The majority of deaths associated with maternal tobacco use in our study were thus categorized due to cigarette smoking (87%), and we believe our conclusions would not have changed if chew use had been excluded.

The MIMR data used in this study were limited primarily by a lack of bed-sharing information for 15% of infant deaths (n=45) and incomplete information on all risk factors of interest for some deaths. The data provided by PRAMS were subject to limitations due to self-report, similar to all survey results. Eight percent of respondents skipped the question about bed-sharing practices, either legitimately or because they chose not to respond. Women who legitimately skipped this question included those whose infants died before they received the survey, and we therefore did not have information on these infants' earlier bed-sharing habits. Some studies have found that among infants of nonsmoking mothers, the risk of bed sharing occurs only when the infant is younger than 8 weeks of age,5 and 40% of the bed-sharing deaths in our study occurred during this time. However, the mean infant age among PRAMS respondents was 3.7 months; thus, PRAMS data may not accurately describe the background prevalence of bed sharing during the period of greatest risk. Finally, our study conclusions were limited by the use of descriptive techniques. Due to the small number of annual births and unexpected infant deaths in Alaska, a longitudinal cohort study to examine this issue would be impractical and lengthy.

CONCLUSIONS

Among women in our study who reported their infant always or almost always shared a bed, 28% also reported cigarette smoking, with smaller proportions indicating other risk factors such as putting their infant to sleep prone, illicit drug use, and frequent alcohol use. This secondary finding suggests that Alaska needs to increase efforts to provide education about safe infant sleep environments and ensure that all families are provided with accurate and complete information on risk factors for infant mortality, that they can provide a safe sleeping environment for their infants, and that they can make an informed choice about sharing a bed with their infant. Some agencies, including the AAP, have simplified their recommendations for safe sleep and advised against all bed sharing. The ADPH message recognizes the profound cultural, social, and potential health benefits (such as breastfeeding and parent-infant bonding33,34) associated with bed sharing. Moreover, Alaska has taken the position that issues of autonomy and equity demand the most accurate presentation of available data to the public.

Through its lack of focus, a recommendation against all infant bed sharing also may result in public criticism from groups focused on other outcomes (such as breastfeeding) and skepticism from mothers who recognize that their infant is at little or no risk from bed sharing. Thus, the ADPH reaffirms that (1) parents always put their infants to sleep on their back unless told otherwise by a medical provider, (2) infants never sleep on a water bed or couch, and (3) infants sleep in an infant crib or with a nonsmoking, unimpaired caregiver on a standard, adult, non-water mattress.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Alaska Maternal-Infant Mortality Review (MIMR) committee members for their time spent reviewing the circumstances of infant deaths in Alaska; Renee Rudd, previously of the Alaska Division of Public Health, for providing access to the Alaska MIMR case files; and Kathy Perham-Hester for providing data from the Alaska Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System.

Footnotes

This article was supported in part by an appointment to the Applied Epidemiology Fellowship Program administered by the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists and funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cooperative Agreement #U60/CCU007277. This article was also supported in part by project H18 MC – 00004-11 from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau (Title V, Social Security Act), Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moon RY, Horne RS, Hauck FR. Sudden infant death syndrome. Lancet. 2007;370:1578–87. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61662-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan FM, Barlow SM. Review of risk factors for sudden infant death syndrome. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001;15:144–200. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tappin D, Ecob R, Brooke H. Bedsharing, roomsharing, and sudden infant death syndrome in Scotland: a case-control study. J Pediatr. 2005;147:32–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hauck FR, Herman SM, Donovan M, Iyasu S, Merrick Moore C, Donoghue E, et al. Sleep environment and the risk of sudden infant death syndrome in an urban population: the Chicago Infant Mortality Study. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5 Part 2):1207–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carpenter RG, Irgens LM, Blair PS, England PD, Fleming P, Huber J, et al. Sudden unexplained infant death in 20 regions in Europe: case control study. Lancet. 2004;363:185–91. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)15323-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kemp JS, Unger B, Wilkins D, Psara RM, Ledbetter TL, Graham MA, et al. Unsafe sleep practices and an analysis of bedsharing among infants dying suddenly and unexpectedly: results of a four-year, population-based, death-scene investigation study of sudden infant death syndrome and related deaths. Pediatrics. 2000;106:E41. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.3.e41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horsley T, Clifford T, Barrowman N, Bennett S, Yazdi F, Sampson M, et al. Benefits and harms associated with the practice of bed sharing: a systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:237–45. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.3.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. The changing concept of sudden infant death syndrome: diagnostic coding shifts, controversies regarding the sleeping environment, and new variables to consider in reducing risk. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1245–55. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scheers NJ, Rutherford GW, Kemp JS. Where should infants sleep? A comparison of risk for suffocation of infants sleeping in cribs, adult beds, and other sleeping locations. Pediatrics. 2003;112:883–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.4.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unger B, Kemp JS, Wilkins D, Psara R, Ledbetter T, Graham M, et al. Racial disparity and modifiable risk factors among infants dying suddenly and unexpectedly. Pediatrics. 2003;111:E127–31. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.2.e127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drago DA, Dannenberg AL. Infant mechanical suffocation deaths in the United States, 1980–1997. Pediatrics. 1999;103:e59. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.5.e59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blair PS, Fleming PJ, Smith IJ, Young J, Nadin P, Berry PJ, et al. Babies sleeping with parents: case-control study of factors influencing the risk of the sudden infant death syndrome. CESDI SUDI research group. BMJ. 1999;319:1457–61. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scragg R, Mitchell EA, Taylor BJ, Stewart AW, Ford RP, Thompson JM, et al. Bed sharing, smoking, and alcohol in the sudden infant death syndrome. New Zealand Cot Death Study Group. BMJ. 1993;307:1312–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6915.1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klonoff-Cohen H, Edelstein SL. Bed sharing and the sudden infant death syndrome. BMJ. 1995;311:1269–72. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7015.1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleming P, Blair P, McKenna J. New knowledge, new insights, and new recommendations. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:799–801. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.092304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gessner BD, Porter TJ. Bed sharing with unimpaired parents is not an important risk for sudden infant death syndrome. Pediatrics. 2006;117:990–1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2727. author reply 994-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartick M. Bed sharing with unimpaired parents is not an important risk for sudden infant death syndrome: letter to the editor. Pediatrics. 2006;117:992–3. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-3165. author reply 994-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gessner BD, Ives GC, Perham-Hester KA. Association between sudden infant death syndrome and prone sleep position, bed sharing, and sleeping outside an infant crib in Alaska. Pediatrics. 2001;108:923–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.4.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoellhorn KJ, Perham-Hester KA, Goldsmith YW. Anchorage: Maternal and Child Health Epidemiology Unit, Section of Women's, Children's and Family Health, Division of Public Health, Alaska Department of Health and Social Services; 2008. Alaska maternal and child health data book 2008: health status edition. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS): methodology. [cited 2008 Nov 14]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/PRAMS/methodology.htm.

- 21.Gilbert BC, Shulman HB, Fischer LA, Rogers MM. The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS): methods and 1996 response rates from 11 states. Matern Child Health J. 1999;3:199–209. doi: 10.1023/a:1022325421844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.SPSS Inc. SPSS: Version 16.02 for Windows. Chicago: SPSS Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scragg RK, Mitchell EA. Side sleeping position and bed sharing in the sudden infant death syndrome. Ann Med. 1998;30:345–9. doi: 10.3109/07853899809029933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramanathan R, Chandra S, Gilbert-Barness E, Franciosi R. Sudden infant death syndrome and water beds. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1700. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198806233182518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leach CE, Blair PS, Fleming PJ, Smith IJ, Platt MW, Berry PJ, et al. Epidemiology of SIDS and explained sudden infant deaths. CESDI SUDI research group. Pediatrics. 1999;104:e43. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.4.e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wetter DW, Young TB. The relation between cigarette smoking and sleep disturbance. Prev Med. 1994;23:328–34. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1994.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang L, Samet J, Caffo B, Punjabi NM. Cigarette smoking and nocturnal sleep architecture. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:529–37. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.England LJ, Levine RJ, Mills JL, Klebanoff MA, Yu KF, Cnattingius S. Adverse pregnancy outcomes in snuff users. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:939–43. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00661-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hurt RD, Renner CC, Patten CA, Ebbert JO, Offord KP, Schroeder DR, et al. Iqmik—a form of smokeless tobacco used by pregnant Alaska natives: nicotine exposure in their neonates. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005;17:281–9. doi: 10.1080/14767050500123731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta PC, Sreevidya S. Smokeless tobacco use, birth weight, and gestational age: population based, prospective cohort study of 1,217 women in Mumbai, India. BMJ. 2004;328:1538. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38113.687882.EB. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Renner CC, Enoch C, Patten CA, Ebbert JO, Hurt RD, Moyer TP, et al. Iqmik: a form of smokeless tobacco used among Alaska natives. Am J Health Behav. 2005;29:588–94. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2005.29.6.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perham-Hester KA. State of Alaska Epidemiology Bulletin 2007. 1. Vol. 28. Anchorage: State of Alaska, Department of Health and Social Services; 2007. Prenatal smokeless tobacco and iq'mik use in Alaska. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McKenna JJ, McDade T. Why babies should never sleep alone: a review of the co-sleeping controversy in relation to SIDS, bedsharing and breastfeeding. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2005;6:134–52. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.ABM clinical protocol #6: guideline on co-sleeping and breastfeeding. Revision, March 2008. Breastfeed Med. 2008;3:38–43. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2007.9979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]