SUMMARY

While increasing evidence suggests that salt-sensitive hypertension is a disorder of the central nervous system, little is known about the critical proteins (e.g., ion channels or exchangers) that play a role in the pathogenesis of the disease.

Central pathways involved in the regulation of arterial pressure have been investigated. In addition, systems such as the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis, initially characterized in the periphery, are present in the central nervous system, and seem to play a role in the regulation of arterial pressure.

Central administration of amiloride, or its analogue benzamil hydrochloride, has been shown to attenuate several forms of salt-sensitive hypertension. In addition, intracerebroventricular (ICV) benzamil effectively blocks pressor responses to acute osmotic stimuli, such as ICV hypertonic saline. Amiloride or its analogues have been shown to interact with the brain renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and to effect the expression of endogenous ouabain-like compounds; both could play a role in the interaction between amiloride compounds and arterial pressure. Peripheral treatments with benzamil, even at higher doses than those given centrally, have little or no effect on arterial pressure. These data provide strong evidence that benzamil-sensitive proteins (BSPs) of the central nervous system play a role in cardiovascular responsiveness to sodium.

Mineralocorticoids have been linked to human hypertension; many patients with essential hypertension respond well to pharmacological agents antagonizing the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR), and certain genetic forms of hypertension are due to chronically elevated levels of aldosterone. The deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA) -salt model of hypertension is a benzamil-sensitive model that incorporates several factors implicated in the etiology of human disease, including mineralocorticoid action and increased dietary sodium. The DOCA-salt model is ideal for investigating the role of BSPs in the pathogenesis of hypertension, because mineralocorticoid action has been shown to modulate the activity of at least one benzamil-sensitive protein, the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC).

Characterizing the BSPs involved in the pathogenesis of hypertension may provide a novel clinical target. Further studies are necessary to determine which BSPs are involved, and where in the nervous system they are located.

Keywords: Sympathetic Nervous System, Epithelial Sodium Channel (ENaC), Acid Sensitive Ion Channel (ASIC), Aldosterone, DOCA, Benzamil, Salt-sensitive Hypertension

INTRODUCTION

Evidence suggests that in humans, hypertension is a disorder of the central nervous system; specifically, sympathetic nervous activity (SNA) is increased in the human disease state [1, 2]. Furthermore, increasing dietary sodium has been shown to affect both arterial pressure and SNA [3–9]. In addition, several animal models of salt-sensitive hypertension exhibit increased SNA, or increased levels of plasma norepinephrine (an indicator of increased sympathetic drive) [10–12]. While high sympathetic tone seems to be a hallmark of many salt-dependent models of hypertension, central administration of amiloride, or its analogue benzamil, attenuates both the level of hypertension reached and circulating levels of norepinephrine [13]. These data suggest an interaction between benzamil-sensitive proteins (BSPs) and SNA; however, it remains to be shown where within autonomic pathways the BSPs mediating this interaction are located. This review will address what is known about the neural pathways involved in the regulation of arterial pressure, as well as the characteristics of known benzamil-sensitive proteins. In addition, we will attempt to summarize possible interactions between the activity of BSPs and central neural control of cardiovascular function.

THE ETIOLOGY OF SALT-SENSITIVE HYPERTENSION

Central Pathways

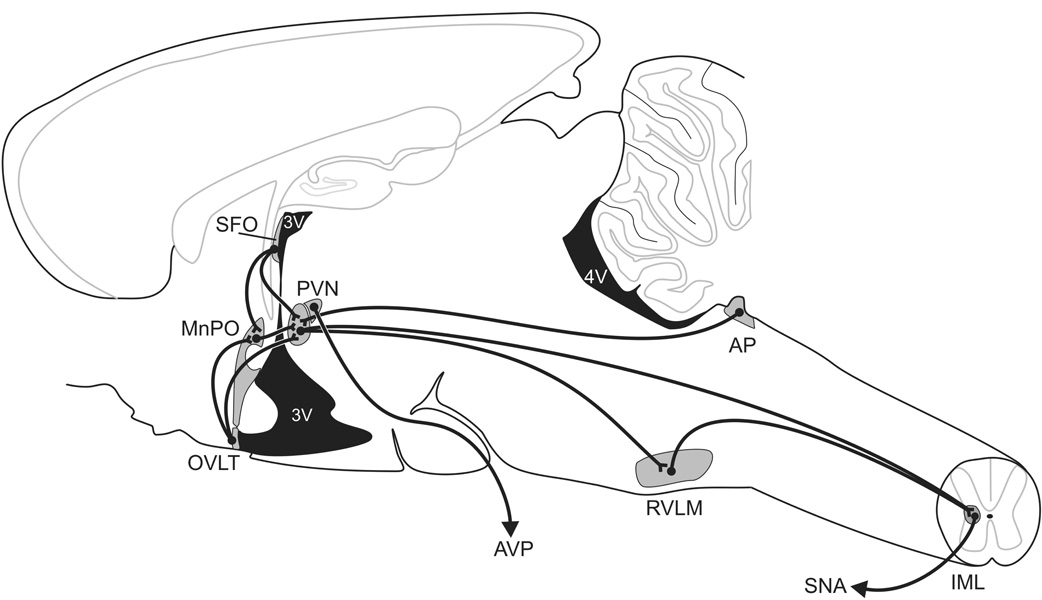

Some of what is currently understood about the neural pathways mediating salt-dependent forms of hypertension has come from studies employing acute osmotic stressors, and extrapolating those results to long-term salt sensitivity of arterial pressure. Drawing on these results, Figure 1 summarizes the hypothetical central pathways involved in the pathogenesis of salt-dependent hypertension. The CVOs, with their fenestrated capillaries, exhibit a weakened blood brain barrier; because of this, CVOs are uniquely situated in the CNS-- able to sense changes in plasma osmolality or hormone levels and to drive subsequent neural activity (e.g., [14], figure 1). Discrete lesions of the area postrema (AP), a hindbrain CVO, prevent MAP increases in the DOCA-salt model of hypertension [15]. Lesions of the anteroventral third ventricle (AV3V region), which contains both the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis (OVLT), and projections from subfornical organ (SFO) to downstream targets, decrease MAP in the DOCA-salt model [16] and other salt-sensitive models of hypertension [17, 18]. OVLT and SFO are forebrain CVOs.

Figure 1. Central Pathways.

CVOs (AP, OVLT, SFO) have a weakened blood-brain barrier due to their fenestrated capillaries. These CNS sites may be important for sensing circulating hormones and/or plasma osmolality [14]. The CVOs send projections to integrative and regulatory sites, such as the MnPO (involved in salt appetite and regulating drinking behavior) and the PVN (critical for defense of homeostasis; e.g., [19]). These pathways continue onto pre-sympathetic areas, such as the RVLM and the IML of the spinal cord [35], which allows for modulation of sympathetic activity and arterial pressure [95, 96].

The CVOs feed unto midbrain sites, and then to bulbospinal pathways that are critical for control of sympathetic nervous activity [19]. Activity of the median preoptic area (MnPO), a downstream target of the OVLT and SFO, seems to play a role in many models of hypertension, [20–22], salt appetite [23], and drinking behavior (of interest because drinking is increased in some forms of salt-sensitive hypertension) [24, 25]. The MnPO, in turn, sends projections to the Zona Incerta (ZI) and to the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN). The ZI plays a role in osmotically induced drinking. In single-cell electrophysiological studies, ZI has been shown to be responsive to changes in osmolality in the AV3V region and at MnPO [26]; firing rates of ZI were affected by both hyperosmotic stimuli (ICV hypertonic saline of varying concentrations) and a hypoosmotic stimulus (distilled water) injected at upstream connection sites. In addition, in electrophysiological recordings from ZI of conscious animals, firing rates increase to the sight of water following osmotic stress (ICV hypertonic saline administration) but not in control animals [27]. Finally, lesions of ZI or ZI antagonism (through local injection of pharmaceutical agents) disrupts drinking behavior in response to osmotic stressors [28–32].

The PVN, another downstream target of the CVOs and the MnPO [33], has been implicated in the control of MAP. The PVN is a hypothalamic nucleus, which plays a role in regulating neuroendocrine responses, such as modulating systemic vasopressin levels through activity of its magnocellular neurons. In addition, the PVN is a presympathetic site, sending projections from parvocellular neurons to the intramediolateral cell column of the spinal cord and to the rostroventrolateral medulla [34–36]. Lesions of the PVN attenuate several forms of hypertension [37, 38]. In addition, OVLT, MnPO, and PVN all show increased activity, as measured by c-Fos immunoreactivity, following acute DOCA-salt treatment [39].

Ultimately, integration of these upstream sites are thought to affect SNA by converging on sympathetic premotor neurons in the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM). The RVLM is believed to be the key brainstem site for regulation of spinal sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the intermediolateral cell column (IML) of the spinal cord [40].

The Role of Central Mineralocorticoids in Salt-sensitive Hypertension

Aldosterone, the primary mineralocorticoid, is a steroid hormone secreted by the adrenal gland, which plays a major role in sodium balance and body fluid homeostasis. Unlike many other steroid hormones, aldosterone does not readily cross the blood-brain barrier [41– 43], and so it has been hypothesized that the CVOs may be critical for driving aldosterone-sensitive responses in the CNS [44]. Basic research implicates mineralocorticoids in the control of arterial pressure. Chronic intracerebroventricular (ICV) infusion of aldosterone results in increased arterial pressure [45, 46]. While systemic administration of aldosterone, or its precursor deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA), also leads to increased arterial pressure, ICV infusion of MR antagonists blocks the hypertensive effect of systemic mineralocorticoids [45, 47], indicating that central responses are necessary for the hypertensive effects seen in systemic aldosterone treatment. Furthermore, following ICV administration of MR antagonists, Dahl salt-sensitive rats remain normotensive, even on a high salt diet [48, 49].

BENZAMIL-SENSITIVE PROTEINS

The Deg/ENaC Superfamily

Benzamil and other amiloride-analogues act at two large classes of proteins. The first are members of the Degenerin/Epithelial Sodium Channel (Deg/ENaC) Superfamily of ion channels. All family members share a common topology, with subunits containing two membrane-spanning regions and a large, cysteine-rich extracellular loop. Mammalian family members include the ENaCs and the acid sensitive ion channels, or ASICs. In both groups, the proteins form multimers composed of four subunits. Two subunits, which are the main structural components of the channel, are repeated. The remaining subunits are modulatory or accessory components of the channel [50–55].

ENaCs are sodium channels, and are involved in salt homeostasis. ENaCs play a critical role in sodium reabsorption in the distal nephron, as well as at the lung and colon [55, 56]. ENaCs may also play a role in the arterial baroreceptor reflex [57]. A δ subunit, sharing much homology with the α subunit, has been identified. Although δ ENaC has a broad neural distribution, to date, it has only been found in primates, and so probably does not play a role in rodent sodium homeostasis [58]. At least one lab has shown the presence of the benzamil-blockable Epithelial Sodium Channel (ENaC) in many autonomic regulatory sites; however, these results remain to be replicated by other labs [59]. In attempts to replicate these findings, using primers published in this study, we were unable to amplify a clear, single RT product [60].

The ASICs are proton gated, non-selective cation channels, which are widely expressed in neural tissue. ASICs play a role in such diverse functions as nociception, response to ischemic events, and ability to taste salt. Gating properties and channel function are dramatically affected by the particular subunits present, and so the specific multimer formed may dictate the physiological function of the channel.

Ion Transport Systems

The second large class of benzamil-sensitive proteins are ion transport systems. These include the Na+/H+ exchanger, the Na+/Ca++ exchanger, the Na+ pump, and the Ca++ pump. The Na+/H+ ion exchanger, or antiport, is a membrane-localized protein found in a wide variety of cell types. It relies on secondary active transport to facilitate the movement of ions (i.e., ion flux generated by active transport at other proteins, such as the Na+/K+ ATPase generate the gradients needed to run these ion exchangers). Increased activity of the Na+/H+ exchanger has been linked to primary hypertension in humans [61].

The Na+/Ca++ exchanger is a bidirectional transporter, whose activity depends on the electrochemical gradients present at the membrane. The Na+/Ca++ exchanger’s activity is coupled to that of the Na+/H+ antiport, and may also play a role in hypertension; while benzamil treatment has been shown to reduce certain models of salt-sensitive hypertension, Keep and colleagues [62] found that amiloride analogues with greater affinity for the Na+/Ca++ exchanger (and very low affinity for Na+ channels) are equally effective in blocking the hypertensive effect of DOCA-salt treatment.

While amiloride and benzamil are inhibitors of these proteins, the ion transport systems have higher affinity for other amiloride analogues, such as 3',4'-dichlorobenzamil; 2',4'-dimethylbenzamil; 5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl) amiloride; and 5-(N-methyl-N-isobutyl) amiloride.

DOCA-SALT HYPERTENSION

DOCA-salt: a neural model

Although peripheral effects of DOCA-salt hypertension (i.e., renal and vascular) are well documented [63], the model is considered a neurogenic form of hypertension. Lesions of the AV3V region [16], or of the AP [15], attenuate DOCA-salt hypertension. In addition, following treatment with a sympatholytic agent, such as hexamethonium, DOCA animals show greater decreases in MAP than control animals [64, 65]. Furthermore, SNA and plasma norepinephrine levels are increased upon DOCA-salt treatment [66]. DOCA [67] or other mineralocorticoid [68] treatment has been shown to increase levels of plasma vasopressin, as well as salt appetite [69], further indication of increased CNS activity following mineralocorticoid treatment. Thirst may also be increased in DOCA-salt hypertension; however, this is often conflated with salt appetite, as animals are frequently given saline in place of drinking water. Finally, ICV benzamil treatment attenuates DOCA-salt hypertension, while peripheral benzamil administration has no effect [13, 70]. Taken together, these data provide strong evidence that the DOCA-salt model is driven by neural activity.

DOCA-salt Hypertension, Mineralocorticoid Receptors, and Benzamil-Sensitive Proteins

The MR is a cytoplasmic receptor with broad neural distribution, which is typically found in association with heat shock and other chaperone proteins. When MR binds ligand, the protein undergoes a conformational change, which frees it from its chaperone proteins and exposes a nuclear translocation signal. In the nucleus, MR acts as a transcription factor [71]. Because of these properties of the MR, nuclear localization of the protein can be taken as an index of MR activity. Indeed, recent studies have shown that MR adjacent to the AP in neurons of the nucleus of the tractus solitarius (NTS) translocate to the cellular nucleus following aldosterone treatment [72]. This unique population of neurons expresses the enzyme 11 β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2, or HSD2. HSD2 catalyzes glucocorticoids; because MR have a nearly equal affinity for aldosterone and the more prevalent glucocorticoids, under normal conditions, MR are thought to be nearly completely occupied by glucocorticoid. However, HSD2 plays a permissive role in neuronal responsiveness to aldosterone through MR. Cells expressing HSD2 are able to respond to changes in aldosterone level, despite higher systemic levels of glucocorticoid. In fact, the HSD2 neurons of the NTS may play a role in modulating responses to DOCA treatment; following one week of DOCA, activity in these neurons is increased [73].

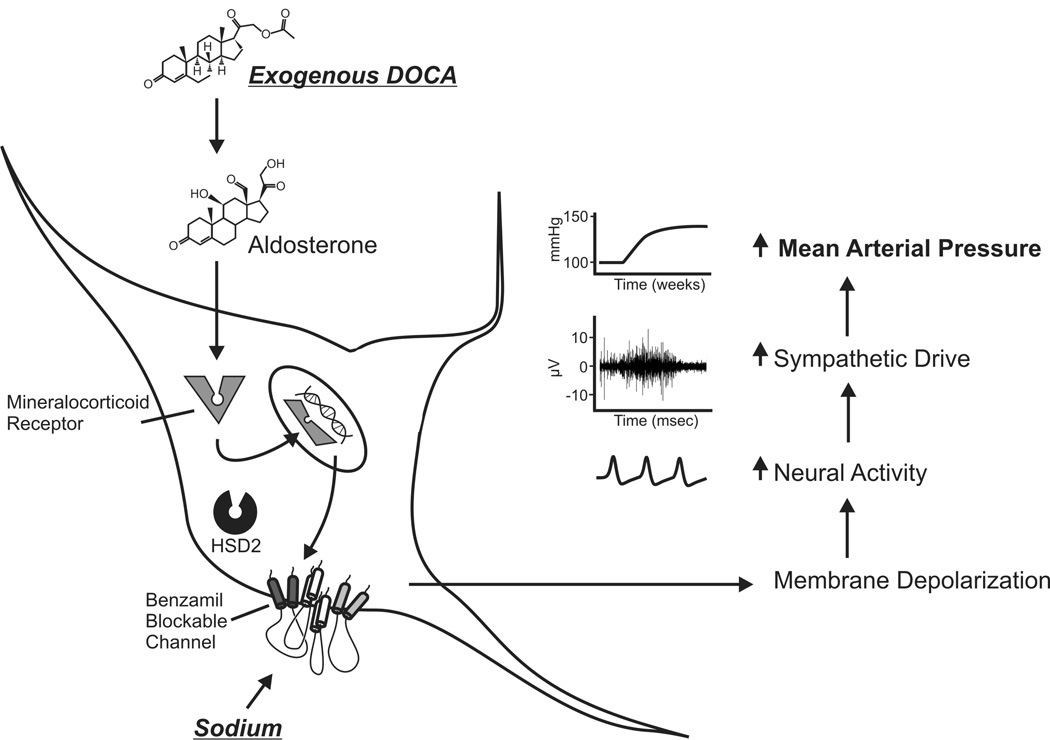

The DOCA-salt model is an ideal model for investigating the role of BSPs in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Figure 2 summarizes the putative relationship between mineralocorticoid action, high-salt diet, and benzamil-blockable channels. Interactions between the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) and ENaCs have been well established [e.g., 68, [74]]. MR is a transcription factor for the α subunit of the ENaC, a BSP known to play a role in sodium transport at the kidneys [75]. Not only has MR activity been linked to the expression of BSPs, but also to the enzymes that regulate the plasma membrane localization of these channels [74]. In addition to direct effects on ENaC transcription, MR is a regulator of Sgk1, a kinase that plays a role in trafficking ENaCs to the cell membrane and in increasing sodium transport across ENaCs. An additional outcome of MR activation and subsequent Sgk1 activity is the inhibitory phosphorylation of Nedd-4. Nedd-4 plays a role in ubiquitin-mediated degradation of ENaC channels. Because of these effects, ICV infusion of MR antagonist will not only block direct aldosterone effects, but may also cause long-term changes in sodium permeability of neurons. While the relationship between MR and ENaCs has been shown, this interaction remains to be established for ASICs or other BSPs.

Figure 2. Model of the Role of BSPs in the Pathogenesis of DOCA-Salt Hypertension.

We propose that benzamil-sensitive ion channels play a role in DOCA-salt hypertension. Following DOCA treatment and subsequent increased MR activity, there would be an increased localization of BSPs to the membrane of HSD2 expressing cells. We believe that this increase in membrane-localized BSPs is likely to occur at sodium-sensitive sites, such as the OVLT, because BSPs seem to play a role both in chronic models such as DOCA-salt hypertension, as well as in acute sensitivity to CSF sodium levels. Membrane localization of BSPs would increase neural activity in the presence of high sodium levels; this in turn, could modulate activity at downstream sites, and thereby regulate SNA and increases in arterial pressure.

Our model is based on the assumption that the BSPs involved in the model are ion channels. Because ENaCs have an established role in sodium homeostasis in the periphery, it has been hypothesized that they subserve this role in the central nervous system. In addition, benzamil has high affinity for the ENaC, and even low doses of benzamil can block acute pressor responses to osmotic stimuli. However, as noted earlier, amiloride analogues can also interact with ion transport systems, and these systems have been shown to play a role in the regulation of arterial pressure.

Benzamil and DOCA-salt Hypertension

DOCA-salt hypertension is attenuated by central treatment with amiloride, or its analogue benzamil [13, 70]. Benzamil is a fairly specific blocker, targeting the ENaC and ASIC proteins, and only at higher doses, certain ion transport systems. While ICV benzamil treatment attenuates DOCA-salt hypertension and decreases vasopressin and norepinephrine levels, systemic benzamil treatment has no significant effect (even when given at much higher doses), indicating a critical role for central BSPs.

Early studies of the effect of benzamil on DOCA-salt hypertension employed tail-cuff measurements in animals with established hypertension. We have recently used radio telemetry transmitters to record MAP in awake, behaving animals, 24 hours a day. These studies suggests that DOCA-salt hypertension develops in several distinct phases; generally, there is an initial rapid rise in MAP, followed by a slower, more prolonged period of increasing MAP, and that benzamil plays a role in attenuating the later, more slowly-developing phase of hypertension [76].

OTHER INTERACTIONS BETWEEN BENZAMIL AND SALT-SENSITIVE CARDIOVASCULAR RESPONSES

Sodium Sensitivity and BSPs

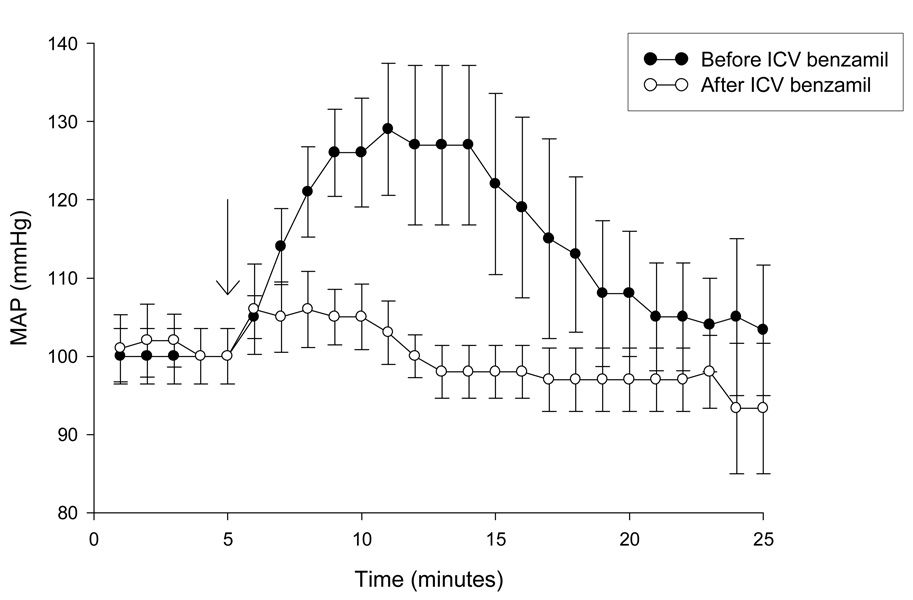

Administration of benzamil will block not only DOCA-salt hypertension, but genetic models of hypertension that are driven by high salt diet [77, 78]. Therefore, it is likely that the BSPs play a role in sodium sensitivity; specifically, we hypothesize that when MR binds ligand, there is a subsequent upregulation of BSPs, which would increase membrane permeability to sodium. This response, in the face of transient increases in plasma sodium levels, would lead to membrane depolarization and an increase in neuronal activity, driving sympathetic outflow and increases in MAP (see figure 2). In addition to a role in salt-sensitive forms of hypertension, BSPs seem to play a role in pressor responses to acute stimuli. The rapid rise in arterial pressure, typically seen following ICV hypertonic saline, is blocked by ICV benzamil (figure 3).

Figure 3. Acute Pressor Response to ICV Saline is Blocked by Benzamil Hydrochloride.

Pentobarbital anesthetized rats (n=6) were instrumented for direct measurement of mean arterial pressure (MAP) via a femoral arterial catheter. MAP was measured by connecting the catheter to a volume displacement pressure transducer coupled to a Grass polygraph. Under stereotaxic guidance, the tip of a 23-gauge stainless steel cannula was placed in the lateral cerebral ventricle. After obtaining baseline MAP for 5 minutes, 50 µL of 1.5% saline was injected over 30 seconds. MAP was recorded for an additional 20 minutes post injection. 20µL of 20nM benzamil hydrochloride (e.g., 0.4 picomoles) was then delivered ICV into the lateral ventricle. A second injection of saline was administered 5 minutes after the benzamil injection, and MAP recorded for 20 minutes. Arrow indicates time of ICV hypertonic saline injection.

In this experiment, male Sprague-Dawley rats (n=6, 250–310 grams) were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital and were instrumented for direct measurement of mean arterial pressure (MAP) via a femoral arterial catheter. MAP was measured by connecting the catheter to a volume displacement pressure transducer coupled to a Grass polygraph.

Under stereotaxic guidance, the tip of a 23-gauge stainless steel cannula was placed in the lateral cerebral ventricle. After obtaining baseline MAP for 5 minutes, 50 µL of 1.5% saline was injected over 30 seconds. MAP was recorded for an additional 20 minutes post injection. 20µL of 20 nM benzamil hydrochloride (e.g., 0.4 picomoles benzamil) was then delivered ICV into the lateral ventricle. A second injection of saline was administered 5 minutes after the benzamil injection, and MAP recorded for 20 minutes.

Although not examined in our study, Brooks and colleagues have shown that acute pressor responses contain both a vasopressinergic and a non-vasopressinergic component: following V1 antagonism, pressor responses to intravenous hypertonic saline are attenuated but not blocked [79]. Nishimura and colleagues have demonstrated that ICV benzamil treatment not only eliminated the pressor response to an acute injection of 1.5M NaCl, but also attenuated levels of sympathetic discharge and plasma vasopressin as compared to control animals [13]. Central benzamil treatment blocks nearly all pressor response to acute hypertonic saline (figure 3), suggesting that both vasopressinergic and other mechanisms are sensitive to benzamil treatment. However, pressor responses to more chronic stimuli, such as DOCA-salt treatment, are merely attenuated. The molecular substrate for this acute/chronic dichotomy remains to be elucidated; however, it is likely that even in chronic protocols, activity of vasopressinergic neurons is altered following ICV benzamil [76].

The Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS)

The RAAS is a well-studied system, which may serve as a “sensor” to the CNS; plasma hormone concentrations of this system change in response to dietary sodium levels. The RAAS may be involved in the DOCA-salt model; changes in the RAAS have been measured, both in the brain and the kidney, following DOCA-salt treatment. Renin and angiotensin-converting-enzyme mRNAs are downregulated in the kidney, following DOCA-salt treatment; however, mRNA levels for these transcripts do not change in the brain. Conversely, following ICV benzamil treatment, mRNAs for critical members of the RAAS are downregulated in the brain, but not at the kidney. Peripheral benzamil treatment has no effect on the members of the RAAS, either in the brain or the kidney. These data indicate that benzamil-sensitive proteins of the central nervous system have the ability to modulate activity of the central RAAS, and thereby modulate arterial pressure. [70]

Endogenous Ouabain-like Compounds and Hypertension

Endogenous Digitalis-like compounds (also termed ouabain-like compounds or endobains) were first found in human-derived tissues in 1991 [80], and these compounds have been implicated in human essential hypertension [81–83]. Endogenous ouabain-like compounds have since been characterized in bovine-derived and murine-derived tissues [84]. Ouabain is a well-known inhibitor of the Na+/K+ ATPase, as well as the Na+/Ca++ exchanger and sodium pump.

Using immunoassay, Gottlieb and colleagues found endobains increased in the plasma of heart failure patients [85]. In addition, plasma endobains have been shown to increase with sodium intake in humans [86, 87]; high sodium intake also leads to endobain increase in a variety of tissue-types in rats [88]. Furthermore, chronic infusions of ouabain have been shown to produce hypertension in the rat [89–91]. Increasing levels of ouabain-like compounds affect the central RAAS and could explain increased SNA [92].

Administration of benzamil has been shown to block the effect of increasing ouabain levels [93, 94]. In addition, benzamil can act directly at several ouabain-sensitive proteins (e.g., Na+/Ca++ exchanger, Na+ pump). These data suggest a potential interaction between endobains and BSPs of the central nervous system.

CONCLUSION

Evidence from multiple animal models suggests a critical role for BSPs in the pathogenesis of salt-sensitive hypertension; however, the specific proteins involved have not been characterized. While it has long been hypothesized that the ENaC may play a role in the central control of cardiovascular responses, finding ENaC in the CNS has proven difficult. While at least one lab has shown the presence of CNS ENaCs [59], other labs have been unable to replicate this result, or have only found evidence for certain ENaC subunits [60]. Furthermore, in a study testing the efficacy of several amiloride analogues in blocking DOCA-salt hypertension, Keep and colleagues found that even amiloride analogues with low affinity for sodium channels were able to attenuate DOCA-salt hypertension. They concluded that the antihypertensive effects of amiloride analogues may be due to inhibiting Na+/Ca+ exchange in the brain [62]. Investigations of the RAAS or of endobains provide further evidence that other proteins, either in the place of, or in addition to the ion channels, may be the BSPs involved in salt-sensitive hypertension. Proper characterization of the BSPs involved in salt-sensitive hypertension is critical, both for our understanding of the disease, and as an avenue for the development of novel clinical treatments.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Mr. Ope Daramola for technical assistance in studies of the role of benzamil in acute pressor responses to ICV hypertonic saline. We also thank Mr. Steve Davidson for his help in preparing figures for this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AP

area postrema

- ASIC

Acid Sensitive Ion Channel

- AV3V

anteroventral third ventrical region

- BSP

Benzamil-sensitive protein

- CNS

Central Nervous System

- CVO

circumventricular organ

- Deg

degenerin

- DOCA

deoxycorticosterone acetate

- ENaC

Epithelial Sodium Channel

- HSD2

11-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2

- ICV

intracerebroventricular

- IML

intermediolateral cell column

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- MnPO

median preoptic area

- MR

mineralocorticoid receptor

- NTS

nucleus of the tractus solitarious

- OVLT

organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis

- PVN

paraventricular nucleus

- RAA

Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone

- SFO

subfornical organ

- SNA

sympathetic nervous activity

- ZI

zona incerta

References

- 1.Wallin BG, Delius W, Hagbarth KE. Comparison of sympathetic nerve activity in normotensive and hypertensive subjects. Circ Res. 1973;33(1):9–21. doi: 10.1161/01.res.33.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miura Y, DeQuattro V. Biochemical evaluation of sympathetic nerve tone in essential hypertension. Jpn Circ J. 1975;39(5):583–589. doi: 10.1253/jcj.39.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Staessen J, et al. Sympathetic tone and relation between sodium intake and blood pressure in the general population. Br.Med.J. 1989;299:1502–1503. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6714.1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinberger MH, et al. Salt sensitivity, pulse pressure, and death in normal and hypertensive humans. Hypertension. 2001;37(part 2):429–432. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.2.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawasaki T, et al. The effect of high-sodium and low-sodium intakes on blood pressure and other related variables in human subjects with idiopathic hypertension. Am.J.Med. 1978;64:193–198. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(78)90045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sullivan JM, Ratts TE. Sodium sensitivity in human subjects: hemodynamic and hormonal correlates. Hypertension. 1988;11:717–723. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.11.6.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinberger M. Salt-sensitivity of blood pressure in humans. Hypertension. 1996;27(2):481–490. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.3.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luft FC, et al. Nocturnal urinary electrolyte excretion and its relationship to the rennin system and sympathetic activity in normal and hypertensive man. J Lab Clin Med. 1980;95(3):395–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dichtchekenian V, et al. Salt sensitivity in human essential hypertension: effect of renin-angiotensin and sympathetic nervous system blockade. Clin Exp Hypertens A. 1989;11 Suppl 1:379–387. doi: 10.3109/10641968909045444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mark AL. Sympathetic neural contribution to salt-induced hypertension in Dahl rats. Hypertension. 1991;17 suppl I:I-86–I-90. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.17.1_suppl.i86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Folkow B, et al. Effects of 240-fold variations in sodium intake on cardiovascular function and neuroeffect characteristics in normotensive (WKY) and hypertensive (SHR) rats. Acta Physiol Scand. 1985;124 Supplementum 542:191. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folkow B, Ely DL. Dietary sodium effects on cardiovascular and sympathetic neuroeffector functions as studied in various rat models. Journal of Hypertension. 1987;5:383–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishimura M, et al. Benzamil blockade of brain Na+ channels averts Na(+)-induced hypertension in rats. Am J Physiol. 1998;274(3 Pt 2):R635–R644. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.3.R635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cottrell GT, Ferguson AV. Sensory circumventricular organs: central roles in integrated autonomic regulation. Regul Pept. 2004;117(1):11–23. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruner CA, et al. Area postrema ablation and vascular reactivity in deoxycorticosterone-salt-treated rats. Hypertension. 1988;11:668–673. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.11.6.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berecek KH, et al. Vasopressin-central nervous system interactions in the development of DOCA hypertension. Hypertension. 1982;4 suppl II:II-131–II-137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon FJ, et al. Effect of Lesions of the Anteroventral Third Ventricle (AV3V) on the Development of Hypertension in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Hypertension. 1982;4:387–393. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.4.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goto A, et al. Effect of an anteroventral third ventricle lesion on NaCl hypertension in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Am J Physiol. 1982;243(4):H614–H618. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1982.243.4.H614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKinley MJ, et al. Interaction of circulating hormones with the brain: the roles of the subfornical organ and the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol Suppl. 1998;25:S61–S67. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1998.tb02303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Budzikowski AS, Leenen FH. ANG II in median preoptic nucleus and pressor responses to CSF sodium and high sodium intake in SHR. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281(3):H1210–H1216. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.3.H1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanaka J, et al. Differences in electrophysiological properties of angiotensinergic pathways from the subfornical organ to the median preoptic nucleus between normotensive Wistar-Kyoto and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Exp Neurol. 1995;134(2):192–198. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1995.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simon JK, Zhang T-X, Ciriello J. Renal denervation alters forebrain hexokinase activity in neurogenic hypertensive rats. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;256:R930–R938. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.256.4.R930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanaka J, Hori K, Nomura M. Diminished salt appetite in spontaneously hypertensive rats following local administration of the angiotensin II antagonist saralasin in the median preoptic area. Behav Pharmacol. 1997;8(8):752–756. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199712000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cunningham JT, et al. The effects of ibotenate lesions of the median preoptic nucleus on experimentally-induced and circadian drinking behavior in rats. Brain Res. 1992;580(1–2):325–330. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90961-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bastos R, et al. Ventromedial hypothalamus lesions increase the dipsogenic responses and reduce the pressor responses to median preoptic area activation. Physiol Behav. 1997;62(2):311–316. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(97)88986-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mok D, Mogenson GJ. Contribution of zona incerta to osmotically induced drinking in rats. Am J Physiol. 1986;251(5 Pt 2):R823–R832. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1986.251.5.R823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mungarndee SS, et al. Hypothalamic and zona incerta neurons in sheep, initially only responding to the sight of food, also respond to the sight of water after intracerebroventricular injection of hypertonic saline or angiotensin II. Brain Res. 2002;925(2):204–212. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03283-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rowland N, Grossman SP, Grossman L. Zona incerta lesions: regulatory drinking deficits to intravenous NaCl, angiotensin, but not to salt in the food. Physiol Behav. 1979;23(4):745–750. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(79)90169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Czech DA, Stein EA, Blake MJ. Naloxone-induced hypodipsia: a CNS mapping study. Life Sci. 1983;33(8):797–803. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(83)90786-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walsh LL, Grossman SP. Zona incerta lesions: disruption of regulatory water intake. Physiol Behav. 1973;11(6):885–887. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(73)90285-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winn P, et al. Excitotoxic lesions of the lateral hypothalamus made by N-methyl-d-aspartate in the rat: behavioural, histological and biochemical analyses. Exp Brain Res. 1990;82(3):628–636. doi: 10.1007/BF00228804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grossman SP. A reassessment of the brain mechanisms that control thirst. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1984;8(1):95–104. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(84)90023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawano H, Masuko S. Synaptic contacts between nerve terminals originating from the ventrolateral medullary catecholaminergic area and median preoptic neurons projecting to the paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus. Brain Res. 1999;817(1–2):110–116. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01233-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ranson RN, et al. The paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus sends efferents to the spinal cord of the rat that closely appose sympathetic preganglionic neurons projecting to the stellate ganglion. Exp Brain Res. 1998;120(2):164–172. doi: 10.1007/s002210050390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hosoya Y, et al. Descending input from the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus to sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the rat. Exp Brain Res. 1991;85(1):10–20. doi: 10.1007/BF00229982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stocker SD, Cunningham JT, Toney GM. Water deprivation increases Fos immunoreactivity in PVN autonomic neurons with projections to the spinal cord and rostral ventrolateral medulla. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287(5):R1172–R1183. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00394.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herzig TC, Buchholz RA, Haywood JR. Effects of paraventricular nucleus lesions on chronic renal hypertension. Am.J.Physiol.Heart Circ.Physiol. 1991;261:H860–H867. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.3.H860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Darlington DN, Shinsako J, Dallman MF. Paraventricular lesions: hormonal and cardiovascular responses to hemorrhage. Brain Res. 1988;439(1–2):289–301. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91486-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pietranera L, et al. Changes in Fos expression in various brain regions during deoxycorticosterone acetate treatment: relation to salt appetite, vasopressin mRNA and the mineralocorticoid receptor. Neuroendocrinology. 2001;74(6):396–406. doi: 10.1159/000054706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sved AF, Ito S, Sved JC. Brainstem mechanisms of hypertension: role of the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2003;5(3):262–268. doi: 10.1007/s11906-003-0030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pardridge WM. Transport of protein-bound hormones into tissues in vivo. Endocr Rev. 1981;2(1):103–123. doi: 10.1210/edrv-2-1-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pardridge WM, Mietus LJ. Transport of steroid hormones through the rat blood-brain barrier. Primary role of albumin-bound hormone. J Clin Invest. 1979;64(1):145–154. doi: 10.1172/JCI109433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pardridge WM, Mietus LJ. Regional blood-brain barrier transport of the steroid hormones. J Neurochem. 1979;33(2):579–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1979.tb05192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Geerling JC, Kawata M, Loewy AD. Aldosterone-sensitive neurons in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 2006;494(3):515–527. doi: 10.1002/cne.20808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gomez-Sanchez EP, Fort CM, Gomez-Sanchez CE. Intracerebroventricular infusion of RU28318 blocks aldosterone-salt hypertension. American Journal of Physiology. 1990;258:E482–E484. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1990.258.3.E482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kageyama Y, Bravo EL. Hypertensive mechanisms associated with centrally administered aldosterone in dogs. Hypertension. 1988;11(6 Pt 2):750–753. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.11.6.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Janiak PC, Lewis SJ, Brody MJ. Role of central mineralocorticoid binding sites in development of hypertension. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:R1025–R1034. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.259.5.R1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gomez-Sanchez EP, Fort C, Thwaites D. Central mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism blocks hypertension in Dahl S/JR rats. Am.J.Physiol.Endocrinol.Metab. 1992;262:E96–E99. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1992.262.1.E96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rahmouni K, et al. Involvement of brain mineralocorticoid receptor in salt-enhanced hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2001;38(4):902–906. doi: 10.1161/hy1001.091781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tavernarakis N, et al. Structural and functional features of the intracellular amino terminus of DEG/ENaC ion channels. Curr Biol. 2001;11(6):R205–R208. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lingueglia E, et al. Molecular biology of the amiloride-sensitive epithelial Na+ channel. Exp Physiol. 1996;81(3):483–492. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1996.sp003951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barbry P, et al. The amiloride sensitive sodium channel. Nephrologie. 1996;17(7):389–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vigne P, et al. A new type of amiloride-sensitive cationic channel in endothelial cells of brain microvessels. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:663–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Benos DJ, Stanton BA. Functional domains within the degenerin/epithelial sodium channel (Deg/ENaC) superfamily of ion channels. J Physiol. 1999;520(Pt 3):631–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00631.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mano I, Driscoll M. DEG/ENaC channels: a touchy superfamily that watches its salt. Bioessays. 1999;21(7):568–578. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199907)21:7<568::AID-BIES5>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Capasso G, et al. Channels, carriers, and pumps in the pathogenesis of sodium-sensitive hypertension. Semin Nephrol. 2005;25(6):419–424. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Drummond HA, Welsh MJ, Abboud FM. ENaC subunits are molecular components of the arterial baroreceptor complex. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;940:42–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ji HL, et al. Delta-subunit confers novel biophysical features to alpha beta gamma-human epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) via a physical interaction. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(12):8233–8241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512293200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Amin MS, et al. Distribution of epithelial sodium channels and mineralocorticoid receptors in cardiovascular regulatory centers in rat brain. Am J Physiol. 2005;289(6):R1787–R1797. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00063.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abrams JM, et al. LB166: Acid-sensitive ion channels (ASICs) in the lamina terminalis of rat brain. EB 2006 Late Breaking Abstracts. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Siffert W, Dusing R. Sodium-proton exchange and primary hypertension. An update. Hypertension. 1995;26(4):649–655. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.26.4.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Keep RF, et al. Effect of amiloride analogs on DOCA-salt-induced hypertension in rats. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;276(6 Pt 2) doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.6.H2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu CT, Nichols BL, Hazlewood CF. Effects of DOCA on circulation, renal functions, body fluids and tissue electrolytes. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1976;220(2):311–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fink GD, Johnson RJ, Galligan JJ. Mechanisms of increased venous smooth muscle tone in deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertension. Hypertension. 2000;35:464–469. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Takeda K, Bunag RD. Augmented sympathetic nerve activity and pressor responsiveness in DOCA hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1980;2:97–101. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.2.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reid JL, Zivin JA, Kopin IJ. Central and Peripheral Adrenergic Mechanisms in the Development of Deoxycorticosterone-Saline Hypertension in Rats. Circulation Research. 1975;37:569–579. doi: 10.1161/01.res.37.5.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yu M, Gopalakrishnan V, McNeill JR. Role of endothelin and vasopressin in DOCA-salt hypertension. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132(7):1447–1454. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pietranera L, et al. Mineralocorticoid treatment upregulates the hypothalamic vasopressinergic system of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Neuroendocrinology. 2004;80(2):100–110. doi: 10.1159/000081314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saravia FE, et al. Changes of hypothalamic and plasma vasopressin in rats with deoxycorticosterone-acetate induced salt appetite. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1999;70(1–3):47–57. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(99)00094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nishimura M, et al. Regulation of brain renin-angiotensin system by benzamil-blockable sodium channels. Am J Physiol. 1999;276(5 Pt 2):R1416–R1424. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.5.R1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pascual-Le Tallec L, Lombes M. The mineralocorticoid receptor: a journey exploring its diversity and specificity of action. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19(9):2211–2221. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Geerling JC, et al. Aldosterone target neurons in the nucleus tractus solitarius drive sodium appetite. J Neurosci. 2006;26(2):411–417. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3115-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Geerling JC, Loewy AD. Aldosterone sensitive NTS neurons are inhibited by saline ingestion during chronic mineralocorticoid treatment. Brain Res. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.07.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bhargava A, Pearce D. Mechanisms of mineralocorticoid action: determinants of receptor specificity and actions of regulated gene products. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2004;15(4):147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mick VE, et al. The alpha-subunit of the epithelial sodium channel is an aldosterone-induced transcript in mammalian collecting ducts, and this transcriptional response is mediated via distinct cis-elements in the 5'-flanking region of the gene. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15(4):575–588. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.4.0620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Abrams JM, et al. Experimental Biology. Washington DC: 2007. Intracerebroventricular benzamil attenuates the maintenance phase of DOCA-salt hypertension: role of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gomez-Sanchez EP, Gomez-Sanchez CE. Effect of central infusion of benzamil on Dahl S rat hypertension. Am J Physiol. 1995;269(3 Pt 2):H1044–H1047. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.3.H1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang H, Leenen FH. Brain sodium channels mediate increases in brain "ouabain" and blood pressure in Dahl S rats. Hypertension. 2002;40(1):96–100. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000022659.17774.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brooks VL, Freeman KL, Qi Y. Time course of synergistic interaction between DOCA and salt on blood pressure: roles of vasopressin and hepatic osmoreceptors. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291(6):R1825–R1834. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00068.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hamlyn JM, et al. Identification and characterization of a ouabain-like compound from human plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(14):6259–6263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.14.6259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Manunta P, et al. Left ventricular mass, stroke volume, and ouabain-like factor in essential hypertension. Hypertension. 1999;34(3):450–456. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.3.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Iwamoto T, Kita S. Hypertension, Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, and Na+, K+-ATPase. Kidney Int. 2006;69(12):2148–2154. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Trevisi L, Pighin I, Luciani S. Vascular endothelium as a target for endogenous ouabain: studies on the effect of ouabain on human endothelial cells. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2006;52(8):64–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Haddy FJ. Role of dietary salt in hypertension. Life Sci. 2006;79(17):1585–1592. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gottlieb SS, et al. Elevated concentrations of endogenous ouabain in patients with congestive heart failure. Circulation. 1992;86(2):420–425. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hasegawa T, et al. Increase in plasma ouabainlike inhibitor of Na+, K+-ATPase with high sodium intake in patients with essential hypertension. J Clin Hypertens. 1987;3(4):419–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bernini G, et al. Endogenous digitalis-like factor and ouabain immunoreactivity in adrenalectomized patients and normal subjects after acute and prolonged salt loading. Am J Hypertens. 1998;11(1 Pt 1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(97)00306-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Leenen FHH, Harmsen E, Yu H. Dietary sodium and central vs. peripheral ouabain-like activity in Dahl salt-sensitive vs. salt-resistant rats. Am.J.Physiol.Heart Circ.Physiol. 1994;267:H1916–H1920. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.5.H1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yuan CM, et al. Long-term ouabain administration produces hypertension in rats. Hypertension. 1993;22:178–187. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.22.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Huang BS, et al. Chronic central versus peripheral ouabain, blood pressure, and sympathetic activity in rats. Hypertension. 1994;23:1087–1090. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.23.6.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Leenen FH, Harmsen E, Yu H. Dietary sodium and central vs. peripheral ouabain-like activity in Dahl salt-sensitive vs. salt-resistant rats. Am J Physiol. 1994;267(5 Pt 2):H1916–H1920. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.5.H1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pamnani MB, et al. Vascular sodium-potassium pump activity in various models of experimental hypertension. Clin Sci (Lond) 1980;59 Suppl 6:179s–181s. doi: 10.1042/cs059179s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang H, Leenen FH. Brain sodium channels and central sodium-induced increases in brain ouabain-like compound and blood pressure. J Hypertens. 2003;21(8):1519–1524. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200308000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Calvino MA, Pena C, Rodriguez de Lores Arnaiz G. An endogenous Na+, K+-ATPase inhibitor enhances phosphoinositide hydrolysis in neonatal but not in adult rat brain cortex. Neurochem Res. 2001;26(11):1253–1259. doi: 10.1023/a:1013923608220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dampney RA. Brain stem mechanisms in the control of arterial pressure. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1981;3(3):379–391. doi: 10.3109/10641968109033672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.McAllen RM, May CN. Differential drives from rostral ventrolateral medullary neurons to three identified sympathetic outflows. Am.J.Physiol.Regul.Integr.Comp.Physiol. 1994;267:R935–R944. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.267.4.R935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]