Abstract

The Healthy Youth Places (HYP) intervention targeted increased fruit and vegetable consumption (FV) and physical activity (PA) through building the environmental change skills and efficacy of adults and youth. HYP included group training for adult school site leaders, environmental change skill curriculum, and youth-led FV and PA environment change team. Sixteen schools were randomized to either implement the HYP program or not. Participants (n =1582) were assessed on FV and PA and hypothesized HYP program mediators (e.g., proxy efficacy) at the end of sixth grade (baseline), seventh grade (post intervention year one) and eighth grade (post intervention year two). After intervention, HYP schools did not change in FV but did significantly change in PA compared to control schools. Proxy efficacy to influence school physical activity environments mediated the program effects. Building the skills and efficacy of adults and youth to lead school environmental change may be an effective method to promote youth PA.

The middle school years may be a critical period for the development of healthy lifestyle behaviors. During this time frame, there are declines in fruit and vegetable consumption (FV) (Lien, Lytle, & Klepp, 2001) and physical activity (PA) (Kimm et al., 2002), and evidence that behavioral decisions impact health behaviors and health outcomes later in life (Telama et al., 2005).

Schools provide places to reach children and youth to influence FV and PA. Some elementary and high school intervention studies have shown positive impacts on FV (Baranowski et al., 2000) and PA (Pate et al., 2005), but few studies have demonstrated impacts on students attending middle school (Sallis et al., 2003).

Middle school interventions may be more effective if they are designed to influence underlying causal processes of behavior change during this critical developmental period. Social cognitive theory targets two modes of individual human agency: personal agency, proxy agency (Bandura, 2006). Direct personal agency has been assessed through individual's self-efficacy beliefs, which is an expectation of one's skills and abilities to organize and execute courses of action required to produce a given outcome. Although self-efficacy has been shown to be an important correlate of health behavior, many adolescents do not have direct control over the social and physical environments that provide opportunities and barriers for their FV and PA choices. Within these contexts, adolescents seek their valued outcomes through proxy agency.

Proxy agency is a socially mediated form of human agency where adolescents try to get other people to act on their behalf to secure their desired outcomes (Bandura, 2006). Adolescents utilize proxy agency when they believe that others, such as parents and school staff, can assist them. Although proxy agency is reflected in self-efficacy assessments, studies of correlates of PA and FV have shown some promise in identifying the proxy agency process of behavior change by developing proxy efficacy scales (Dzewaltowski, Karteroliotis, Welk, Johnston, Nyaronga, & Estabrooks, 2007) and by examining correlates of health behavior with proxy efficacy items in self-efficacy measures (e.g., Reynolds, Yaroch, Franklin, & Maloy, 2002), environmental change efficacy measures (Ryan & Dzewaltowski, 2002) and support seeking measures (Saunders et al., 2002).

A gap in the literature exists such that we have not identified an investigation that directly targeted building youth and adult leaders self and proxy efficacy. Many school-based intervention studies have attempted to promote behavior change through a centralized dissemination model where the expertise and control over implementation resides in the investigative team and dissemination flows in a top down fashion. These types of studies are not designed to build the proxy agency of school leaders or of middle school youth. An alternative to the top-down centralized strategy is a participatory community-building approach that provides control to local decision makers. A participatory community-building approach may be important during the middle school years because this is a developmental period where adolescents are seeking autonomy from adult leadership. In addition to building proxy efficacy, participatory strategies may have more widespread reach because they can be designed so that they can be adopted and implemented by communities and schools with limited reliance on outside experts.

In this paper, we report the intervention outcomes from the Healthy Youth Places (HYP) Project, a school-randomized trial evaluating the effectiveness of a multilevel intervention model designed to develop the skills and efficacy of adult leaders and youth to build middle school environments (healthy places) that promote FV and PA. We hypothesized that youth attending schools receiving the HYP intervention would increase in PA and FV, relative to youth in control schools.

METHOD

School and Youth Participants

A nested cohort design with a priori stratification and school as the unit of randomization and analysis was used to test the primary study hypotheses (See Figure 1) (Murray, Varnell, & Blitstein, 2004). Sixteen middle schools volunteered to participate based on the following eligibility criteria: (1) included seventh and eighth grades, (2) managed on-site at the middle school rather than by the school district, and (3) agreed to participate prior to randomization. The schools were stratified by factors expected to affect the primary outcomes (concentration of lower socioeconomic status [SES] measured by proportion of students eligible for free and reduced lunch, range 1% - 70%; concentration of ethnic diversity measured by proportion of white students, range 38% -95%; and school size, n=260-782) and assigned to three school strata for randomization (Klar & Donner, 2001). The first strata included four small schools (mean size =343 students) with primarily white (mean % = 96.8) and some lower SES (mean % =26.3) students. The second strata included six large homogenous schools (mean size = 547 students) with primarily white students (mean % = 90.7) and some lower SES (mean % = 22.5). The third strata included six large-diverse schools (mean size = 637) with some diversity in ethnicity (mean % white students = 59) and a large proportion of lower SES students (mean % = 55). Within strata, eight schools were randomized to receive the intervention while eight schools served as assessment-only controls.

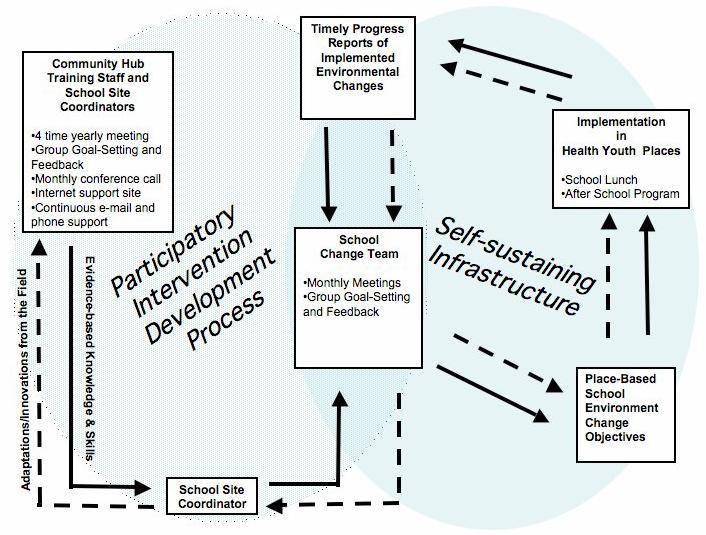

Figure 1.

The Healthy Youth Places Intervention Model.

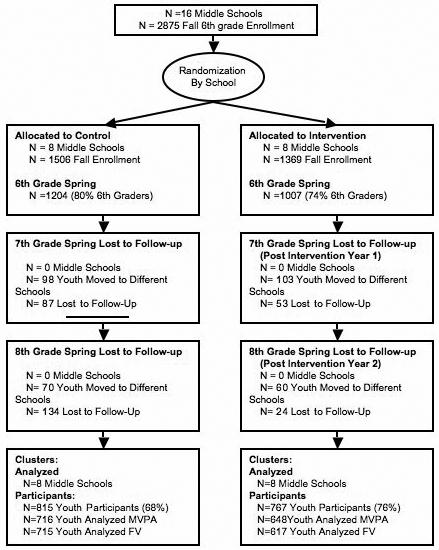

Students attending the middle schools during sixth grade (baseline year) and whose parents or guardians provided written informed consent for their children to participate in the assessments were eligible for participation in the study (see Figure 2). Of the 2875 sixth graders enrolled on the 20th day of the school year children, 74% of children in intervention schools (n = 1007) and 80% of children in the control schools (N =1204) had parental consent and participated in the spring sixth grade baseline assessments. At baseline sixth grade children in intervention and control schools were comparable in age [Mean yr=12.36 (.40) vs. 12.40 (.43)], sex (46% vs. 47.2% boys), socioeconomic status (29.8% free and reduced vs. 36.8%), and BMI [Mean Kg/m2= 19.15 (3.98) vs. 19.18 (3.78)]. The ethnicity of intervention group (white=77.7%, black 10.0%, Hispanic, 4.67%, American Indian 1% Asian 3.5%) was also comparable to that of the control group (white=78.7%, black 9.0%, Hispanic, 4.2%, American Indian 2.5% Asian 1.4%).

Figure 2.

The process of recruitment of schools and children into the cohort for participation in the Healthy Youth Places Study.

Figure 2 illustrates that the study cohort included 815 youth attending control schools and 767 children attending intervention schools. Control and intervention students were comparable on sex (% Female =53.6 vs. 54.18), ethnicity (% white =87.35 vs. 81.07), socioeconomic status (% not free and reduced = 68.80 vs. 73.76), and BMI [Kg/M2=18.93(3.72) vs. 19.00 (3.64)]. Across sixth, seventh and eighth grades some students were lost to follow up and several students were moved from one school to another new school building by the school district in the eighth grade. The new additional school implemented the intervention, and these students were followed to their new school and included in study cohort. Those lost to follow-up were lower in socioeconomic status (45% free and reduced) and more diverse (63.3% white, 15% black, 7.5% Hispanic, 2.7% American Indian, and 2.1% Asian) than the baseline sample).

Intervention Program

The multilevel intervention model was designed to target the development of the personal and proxy agency of adult leaders and youth to build middle school environments (healthy places) that promote FV and PA. The intervention model was designed to influence direct personal agency by building youth self-efficacy for FV and PA. Proxy agency is a socially mediated form of agency exerted by youth when they try to get other people who have expertise or influence to act on their behalf to secure their desired outcomes. The intervention model was designed to influence proxy efficacy by building youth's confidence that they could influence others, teachers and parents, to assist them in building healthy places.

Three tiers (levels) of intervention were used to develop the capacity of adult leaders and youth to build middle school environments (healthy places): project level, school level, place level. Figure 1 depicts the intervention model for which the rationale for has been published previously (Dzewaltowski, Estabrooks & Johnson, 2002).

At the project level, expert staff delivered continuous group staff training intervention to paid school site coordinators from the eight intervention schools. For the group staff training, school site coordinators from the eight intervention schools were linked together as part of a “performance community hub” to facilitate sharing and problem solving. They attended four training sessions yearly and participated in monthly conference calls. These training sessions (with periodic e-mail, phone, video and web support) emphasized theory-based principles of behavior change and strategies to engage students in advocacy for PA and FV environmental change.

To facilitate participatory planning, site coordinators were instructed and worked with a place-based planning and monitoring system that required them to target a place for environmental change (school lunch, after school program, classroom), to develop environmental change objectives that reached and appealed to youth and to develop a place that would either build youth's environmental change skills or would provided options for physical activity or fruit and vegetable consumption in a positive social environment. The participatory planning and monitoring system also require sites to promote and market their environmental changes. Environmental change was defined as implemented practices, programs, and policies that promote elements critical to encouraging healthful FV and PA options in school settings. A positive social environment was characterized by the CASH elements (Connection, Autonomy, Skill building, and Healthy norms).

At the school level, adult site coordinators led the delivery of the change team intervention. This tier mirrored the community hub intervention, with the school site coordinator acting as a facilitator and resource for youth-led school advocacy groups, known as “change teams.” The change team was the hub of intervention activities at the school. Students were instructed on the place-based environmental planning and logging system and followed a step-by-step process to implement their environmental change efforts. Key youth and adult place leaders (individuals with a high degree of responsibility and involvement in the targeted classroom, school lunch, and after-school program) were participants on the school change teams. The school change teams created awareness and visibility within their school regarding the importance of physical activity and good nutrition. A video workgroup at each intervention site, provided with a twice yearly training, a computer, digital video camera, and video editing software, developed site-specific videos that highlighted ways that students could incorporate FV and PA into specific school settings. As an incentive for participation, control schools were also delivered the computer, video camera, and video editing software but were provided with no training on its use.

Places targeted for implementation included the classroom, school lunch and the after school program. The goal of the place level interventions was to reach all children in the intervention grade cohort, build their skills and efficacy for environmental change, and offer them the opportunity for exposure to implemented school environmental changes. In the classroom, a seventh and eighth grade curriculum (“Students Building and Promoting Healthy Places”) that targeted building the knowledge and skills for environmental change was implemented to help facilitate student leadership.

The seventh grade curriculum included eight lessons that introduced students to the planning process and steps to environmental change and taught youth environmental change skills (team work and collaboration, physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption information gathering, analysis of environmental change plans and efforts, and communication and marketing). The eighth grade curriculum included four lessons that reinforced the place-base planning process and youth planned environmental changes in both school lunch and after school program. Students completed the eighth grade curriculum by learning how to promote their environmental change efforts.

Process Evaluation

The process of implementing the three tiers of intervention was evaluated as follows. The project team delivered the performance community intervention. Receipt of the performance community intervention was evaluated by site coordinator attendance and by a survey of the site coordinators. The survey assessed the site coordinators self-efficacy to lead and train others to build healthy places on a 0 (not sure) to 5 (sure) scale. The At the school level, delivery of the intervention was evaluated by site coordinators self-reporting their change team meetings by logging implemented programs, policies, and practice environmental changes at the school site, which were evaluated by two independent raters (Fawcett et al., 1995). Teachers also self-reported their implementation of the curriculum. Receipt of the intervention was assessed by youth responding to a survey of their awareness of the project and their participation in project activities.

Outcome Evaluation

Students participated in a school data collection at baseline (sixth grade, spring), post-intervention year 1 (seventh grade, spring) and post-intervention year 2 (eighth grade, spring) where, with a few exceptions, one intervention school and one control school were visited each week primarily during the month of April. Trained research assistants visited each school and presented definitions of physical activity (type, intensity, and duration) and servings of fruit and vegetables. Students then completed a questionnaire measuring several psychosocial variables. After completing the psychosocial questionnaire, students were taught how to complete the Previous Day Physical Activity Recall (PDPAR)(Weston, Petosa, & Pate, 1997). On the three subsequent days, students completed the PDPAR assessments in a classroom setting. On the last day of recall, students were provided with all three days of their PDPAR logs and were asked to complete any missing time periods. FV consumption and self-reported height and weight (body mass index, [BMI]) was then measured by the validated Youth/Adolescent Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) (Rocket et al., 1997).

Outcome Measures

PDPAR

The PDPAR is a wide used self-report instrument in physical activity research that has been shown to be significantly associated with objective accelerometer and heart rate measures of physical activity during after school time (Weston et al., 1997). A small sub sample of students at 4 intervention and 4 control schools wore an accelerometer during the data collection week that provided validity information for the PDPAR protocol in this study. Correlations with the accelerometer and the PDPAR were greater than .5 (Welk, Dzewaltowski, & Hill, 2004). The PDPAR uses a time-grid of 30-minute intervals to help children record their previous day's activity after school between the hours of 3:00 pm and 11:30 pm (17 blocks). For each time block, the child enters a code representing the predominant activity in which they participated and rates its intensity (light, moderate, hard, very hard). Intensity ratings were evaluated according to the established protocol where each activity code is assigned an estimated MET level using the Compendium of Physical Activities. The outcome variable for the PDPAR was the percent of 30-minute blocks a child spends in moderate and vigorous (≥4 METS, MVPA) or vigorous (≥6 METS, VPA) categories after school each day.

YAQ

The Youth Adolescent QuestionnaireYAQ is a widely used food frequency questionnaire that assesses adolescents' diets and heights and weights in large studies where 24-hour food recalls are not feasible (Rockett et al., 1997). The validity and reliability of the instrument is previously established by comparing two YAQ assessments made one year apart with 24-hour dietary recalls. The correlation for different dietary outcome variables ranged from .21 for sodium and .58 for folate with an average of .54 (Rockett & Colditz, 2003). The outcome variable of the FFQ for this study is an estimate of the number of servings of FV per day. Self-reported height and weights were used to compute body mass index (BMI). BMI scores were converted to percentiles using the age and sex specific norms from the CDC growth charts.

Youth Psychosocial Survey

Youth completed a survey developed by the study authors to assess several constructs. Reported here are measures of self-efficacy, proxy efficacy, and group norm.

Self-efficacy scales measured students' confidence to be physically active or to eat fruit and vegetables daily. For physical activity self-efficacy, students reported their confidence to be physically active 1 to 7 days per week on a 0 (“not at all sure”) to 5 (“completely sure”) scale. Physical activity was defined for the youth as “any activity that is as hard as brisk walking, makes your heart beat faster, and lasts for about 30 minutes or more each day. Things like walking to school, riding your bike, aerobic dance, and sports are different kinds of physical activities.” This measure was a refinement of a one-item measure that was shown to predict physical activity in this age group (Ryan & Dzewaltowski, 2002). For this study we report results from a three item scale, students confidence to be physically active 5 to 7 days per week, because a previous investigation demonstrated that these items represented a unique factor structure that included the physical activity behavioral goal (Dzewaltowski, et al., 2007). For fruit and vegetable consumption self-efficacy, students reported their confidence to eat 1 to 6 servings of fruit and vegetables daily. For this study we report results from a three-item scale, students confidence to eat 4 to 6 servings week, because a previous investigation demonstrated that these items represented a unique factor structure that included the fruit and vegetable consumption behavioral goal of 5 or more servings per day (Gyurcsik, Dzewaltowski, Karteroliotis, Estabrooks, & Hill, 2002).

Proxy efficacy, measured from 0 to 5, indicated student's confidence in their skills and abilities to get others to act on his or her interests to create supportive environments for physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption (Dzewaltowski et al, 2007). Students responded to items targeting key leaders (teachers and school staff, after school program staff, and parents) of school, school lunch, and after school environments. An example question was, “How sure are you that you can get the after-school program staff to plan physical activities for you and the other members of the after-school program?” Physical activity Proxy Efficacy-School consisted of six items that captured the influence of school staff on children's PA. Physical Activity Proxy Efficacy-Parents included four items that measured children's confidence in their parents' support for their PA. Physical Activity Proxy Efficacy-Peers included two items, such as “Get a friend to do physical activities with you?” Fruit and Vegetable Proxy Efficacy-School included nine items that captured student's confidence that they could influence school staff. Finally, Fruit and Vegetable Proxy Efficacy-Parents included three items such as, “get your parents to help you include cut-up vegetables with dressing (like carrot sticks and ranch dressing) in your lunch?”

The youth survey also included one item measures of physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption group norm. For example, fruit and vegetable group norm was assessed from agree (1) to disagree (5) with the statement “my group of friends try to get me to eat fruits and vegetables during my meals and snacks.”

Statistical Analyses

Generalized linear mixed model analysis and the SAS PROC GLIMMIX were used to analyze the physical activity outcome of percentage of 30-minute blocks of activity (51 blocks across three days). We also summed the 30-minute blocks of physical activity for each day across three days and categorized students if they participated in one or more VPA block per day or two or more MVPA blocks per day standard. The analysis of the standard categorization roughly corresponds to physical activity guidelines of 30 minutes of VPA three times weekly or daily MVPA of 60 minutes and is consistent with the analysis of the LEAP project (Pate et al., 2005). The FV and psychosocial outcomes were evaluated using general linear mixed model regression with SAS PROC MIXED (Littell, Milliken, Stroup, & Wolfinger, 1996).

For all outcome analyses, condition (intervention vs. control) and strata were modeled as fixed effects. School and time were included as random effects nested within strata. Comparisons of least squared means were evaluated at P<.05, two-tailed tests. Possible effect modifications due to demographic factors (gender, race, free and reduce lunch eligibility, BMI) were tested. Due to a limited amount of diversity in the sample, race categories were collapsed into white and other. Covariate terms were added to represent the main effect and their interaction with the strata and condition over time. Non-significant main effect covariates were included in the model. Non-significant interaction (four way, three way, two way) terms were deleted in a stepwise deletion processes (Milliken & Johnson, 2002).

If the primary behavioral outcome was significant (MVPA, VPA, FV), the process by which changes in self-and proxy efficacy mediated the impact of the intervention was evaluated by, a multilevel mediating variable analysis was performed using the mixed model and an approximate standard error test of the mediation effect (Krull & MacKinnon, 2001).

RESULTS

Sixth graders reported that 8.5 percent and 15 percent of the 30-minute time blocks after school were VPA and MVPA, respectively (Table 2). Fifty-five percent of sixth graders were meeting the standard of one or more 30-minute VPA block per day and 61 percent were meeting standard of two 30-minute MVPA blocks per day. The majority of sixth graders were not consuming the recommended number of 5 servings of FV per day. Fruits were eaten more often than vegetables.

Process Evaluation

The project team implemented the performance community training as planned. Site coordinator attendance was 97% (range 75 -100%) in the first intervention year and 91% in the second intervention year (range 75-100%). Survey of the site coordinators on their self-efficacy to lead and train others to implement the intervention was high (4.00 on a 0 to 5 scale; SD =.45) at the beginning the project and did not change after year 2 (3.79, SD= 1.05) and year 3 (4.10, SD =.66).

At the school sites, site coordinators formed changed teams during the first intervention year and began meeting regularly during the spring. During year two, the site coordinators held average of 15.8 meetings (range 16-27). The site coordinators reported an average of 26.5 implemented program, policy or practice changes (range 10-39). These changes occurred school wide (mean = 13, range = 2-21) or during school lunch (mean = 5, range 2-14) and the after school program (mean =11.75, range 1-26). During seventh grade school teachers reported implementing 5.6 lessons (range 3-8) in the classroom for 13.5 hours (range 4.7-18.9), which was on average 64.4 % of the intended lessons (range 34-116), but implemented lessons exceeded the lesson time goal (mean 122.6% range 66%- 188%). During eighth grade school teachers reported implementing 3.25 lessons in the classroom (range 0-4) for 5.89 hours (range 0-9.96), which was on average 81.2% of the intended lessons (range 0-100%) and 60.1% of the intended lesson time goal (range 0%-99.6%).

Youth surveys revealed that 31.6% heard about Healthy Places (16.7-49.5%). 35.6% perceived that there was media promoting PA after school (15.9-46.7%), 15.2% perceived that there was media promoting fruit and vegetable consumption (6.3-34.1%), 31.0 % thought school staff promoted PA after school (range 12.7-42.7%) and 14% thought school staff promoted fruit and vegetable consumption (range 7.9-35.3).

Youth surveys revealed that 37.5% heard about the change team (range 16.7-49.5%), 14.9% participated on the change team (range 10.7-19.8%), 23.4% heard about the video team (9.5-52.0%), and 7.2 % participated on the video team. Twenty percent of the intervention school students reported attending the after school program compared to nine percent in control schools during the eighth grade year.

Fruit and Vegetable Outcomes

Table 2 illustrates that the intervention and control schools did not change differently over time on FV, fruit, or vegetables. Although there was no intervention effect for FV, the HYP schools decreased in self-efficacy for FV consumption (p=.04) and increased in student friend group norm for FV (p=.03) compared to controls. There was a (.34) difference in change in self-efficacy for FV between sixth and seventh grade (p=.01). There was a .25 difference in change in student friend group norm for FV between sixth and seventh grade (p=.008).

Physical Activity Outcomes

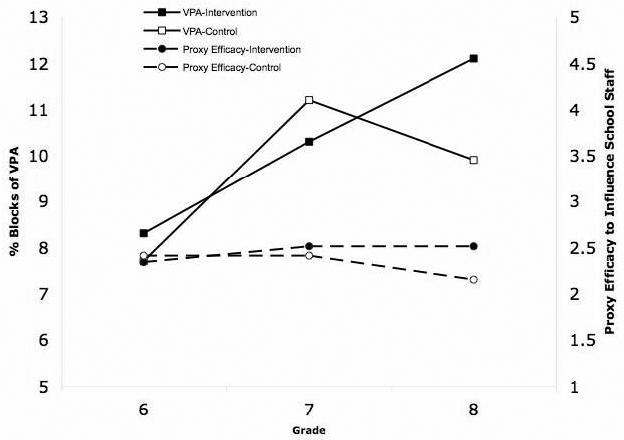

After the sixth grade baseline year, the mixed model analysis that controlled for gender, race, and SES showed that the cohort of students attending intervention and control schools changed differently over time on VPA and MVPA. From sixth grade to after the first intervention year (seventh grade), there was a trend (p=.068) in the changes between intervention and control schools (Figure 2). From seventh grade to after the second intervention year (eighth grade) intervention schools increased and the control schools decreased in VPA (p=.006). Similar results were found for MVPA. Gender, race or SES did not interact with the intervention effects overtime (Table 2).

To evaluate the impact of loss of students across the study, we also recruited new students each year. In the cohort there were 815 students in the invention group and 767 students in the control group. The sixth grade sample (control n =1204; intervention n=1007) and eight grade sample (control n = 984; intervention n =1043) were then compared in a nested cross section analysis (Stevens et al., 2005). A mixed model analysis (gender, race, and SES covariates) on all students in the sixth, seventh, and eighth grade cross sections showed a significant condition by time interaction for VPA and MVPA (p=.001). Therefore, loss of students did not appear to explain the physical activity outcomes found in the cohort.

Figure 2 illustrates that the intervention schools increased compared to controls on proxy efficacy for changing PA school environments. There was a .43 difference in change from sixth grade to eighth grade (p=.0001). There was also a significant difference in change between intervention and control schools on self-efficacy for PA (p=.02). Control schools increased compared to intervention schools between sixth and eighth grade (Table 2).

As stated above, intervention schools changed differently over time on the primary physical activity outcome measures (VPA, MVPA) and an intermediate outcome measure (proxy efficacy for changing PA school environments) compared to control schools (See Table 2). School proxy efficacy for PA was added to the VPA and MVPA mixed models to determine if the changes in physical activity due to the intervention could be explained or mediated by proxy efficacy. For VPA, inclusion of the mediator increased the difference in change between sixth and seventh grade. The change between conditions was significant (p=.03) and the mediation test was significant (p=.003). By controlling for proxy efficacy, the intervention group change from sixth to eighth grade decreased from 1.9 to 1.78 and the control group change increased from 3.5 to 3.65. No mediation effect was found between seventh and eighth grade. Therefore, proxy efficacy was mediating variable for the intervention group and suppressor variable for the control group. The suppression effect in the control group was likely due to an increase in physical activity over time that was not influenced by changes in proxy efficacy. These findings support the hypothesis that proxy efficacy mediated the increase in physical activity found in the intervention group. Consistent results were found for MVPA, with the exception that the mediation test from seventh to eighth grade was significant (p=.05).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that an intervention designed to build the skills and efficacy of adult school leaders and youth can increase proxy efficacy to change school environments and influence the physical activity of middle school students. Across their sixth, seventh, and eighth grade years during the after school hours of 3:00 to 11:30 p.m. children in intervention schools increased in vigorous physical activity by 3.7 percent and children in the control schools increased 2.26 percent. Because children reported the primary behavior they performed in 17 30-minute blocks per day, the 1.47 percent difference in increase in reported 30 minute physical activity blocks is approximately 7.5 minutes per day on the previous day physical activity recall scale. Increased opportunities for after school sports in seventh grade may have contributed to increased physical activity for both intervention and control students. Control schools changed in a more positive manner on self-efficacy for physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption. The intervention may have made students more aware of the difficulty in changing these two behaviors and this decreased their confidence to perform these two behaviors.

The Healthy Youth Places multilevel intervention has several unique components. At the project level, the expert project team trained school site coordinators and school staff in the skills needed to promote fruit and vegetable consumption and physical activity within their schools. The significant effects on physical activity that occurred without direct involvement of the project team at the school sites is noteworthy because it demonstrates the effectiveness of school-level training aimed at building the capacity and skills of school staff. Although implementation at each school site varied, the project-level intervention was implemented consistently to all schools by the project team and this allowed for testing a standardized intervention protocol. Many school-based interventions rely on project staff to ensure that the programs are implemented with fidelity at all treatment sites. This level of support often varies across sites and is unlikely to be duplicated in future dissemination efforts. We chose to have a standardized training protocol and not have the expert training staff involved in the programming activities at the site. This allowed us to evaluate a model that would be more likely to translate into practice. Although the current program was delivered to only eight schools, the number of schools participating in the group training sessions could easily have been increased. An expert training team could easily lead the project level intervention for a larger number of schools or lead several community hub groups simultaneously.

A central aspect of the intervention at the school level is that emphasis was placed on building the capacity of school staff to create environmental change rather than on the implementation of a specific curriculum or program. Pate and colleagues recently demonstrated an increase in physical activity among high school girls using a similar facilitative approach (Pate et al., 2005). A facilitative approach was also successful in the El Paso CATCH study intervention, which successfully slowed the increase in risk of overweight and overweight seen in control children (Coleman et al., 2005). The positive results from the present investigation and these two studies (El Paso CATCH, LEAP) demonstrate the potential advantages of community-driven development models using evidence-based principles for school-based interventions. The contribution of the present project is the development of a standardized protocol for a community-driven process rather than utilizing a process where direct contact by the project team is used to achieve implementation. Community-driven process interventions may be more likely to be disseminated and have greater effects across contexts because adaptation of the intervention is part of the intended intervention strategy.

The intervention placed youth in a leadership role to help change the school lunch and after school environments and taught them environmental change skills. This resulted in intervention schools students increasing in confidence that they could influence school staff to provide supportive physical activity environments compared to control school students (proxy efficacy). Furthermore, there was a mediation suppression effect, such that changes in proxy efficacy between sixth and seventh grade could account for changes in the intervention schools' physical activity but not in control schools (MacKinnon, Krull, & Lockwood, 2000). The middle school years are a critical period where youth need environments that provide social connection and opportunities for autonomy and personal mastery through acquiring skills (Dzewaltowski, Estabrooks, & Johnston, 2002). A central process of health behavior change for this age group may be the establishment of a sense of personal agency or self-efficacy and autonomy in youth, and this can best be accomplished by providing experiences that show youth how to meet these needs (Bandura, 2006).

Other studies have reported positive FV(Lytle et al., 2004) and PA(Sallis et al., 2003) outcomes from changing middle school environments but investigators have reported that barriers to implementing these interventions need to be better understood and overcome. The lessons learned from this study can facilitate future school-based projects. While physical activity outcomes were positive, additional work is needed to determine how to effect change in FV. Although schools were managed at the site, school food service decisions were sometimes controlled at the district level, so changes in these environments may require an addition district-level intervention. Overall FV changes were not significant, but several schools made important changes in school lunch quality. Intervention students' group norm for fruit and vegetable consumption increased compared to control schools. The measures used to detect FV consumption (food frequency questionnaire) may not have been sensitive enough to change – particularly because the new food offerings at some schools were not specifically listed as a food choice on the instrument. Future studies need to adopt measures that include specific foods that environmental changes implement.

There are a number of strengths in this present study. We sampled schools (n=16) with diverse characteristics and resources. The inclusion of different sized schools from different sized communities demonstrates that the effects may generalize to settings with diverse characteristics. Another strength is the use of a group randomized design and statistical methods that controlled for the intraclass correlation within schools.

It is also important to acknowledge some limitations. Schools in this study were volunteers and not selected randomly from a population of schools based on specific setting characteristics. These schools may have had greater motivation to change, which may explain the improvements shown in the control schools over time. Another limitation is the difficulty in identifying the key components of the intervention that most strongly contributed to the effects that we observed. The use of different doses of intervention would have allowed us to examine possible differences in program outcomes. Future work building from these community-driven approaches can examine this possibility.

Implications for Practice

A major challenge for practitioners is to influence the fruit and vegetable consumption and physical activity of youth through the delivery of an intervention that is both effective and has a reach into the target population to have public health impact. Delivery of evidence-based interventions by public health behavior change experts individually and in small groups is not likely to have enough reach large enough percentage of the target population. If public health behavior change experts target building the capacity of others through a multilevel intervention model, one expert or a small group of experts may be able to influence others with an intervention that has both effectiveness and reach.

The present study provided support for the Healthy Youth Places intervention, which included a framework to promote fruit and vegetable consumption and physical activity by training building adult leaders and youth with the goal to build their skills and efficacy for school environmental change. Although the intervention has a small physical activity effect, the multilevel intervention model was shown to be feasible and was could be easily implemented with a large number of sites to reach enough youth to have public health impact. The community hub component of the intervention included four group trainings, a monthly conference call, and continuous internet and phone support. It would be possible to deliver this intervention to a group of site leaders in a county, region of a state, or across a whole state. We deliberately choose not to provide school site visits to support the site coordinators delivery of the intervention because we recognized that if the community hub training was delivered across a state that this would not be feasible. Finally, the present study provided support for placing adolescents in a leadership role to facilitate environmental change. Health professionals should note that the skills and efficacy of youth to provide them with the control to influence others is an important strategy for working youth during the middle school years.

Figure 3.

The effect of the intervention on percent of 30 minute blocks of vigorous physical activity per day after school from 3:00 until 11:30 and proxy efficacy to influence school staff to change school environments.

Table 1.

Least square means and standard errors (SE) for physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption adjusted for gender, SES, ethnicity, and BMI by condition (C) and grade (G).

| (C) | Cohort Least squares means (SE) |

Cohort Least squares means (SE) adjusted by covariates |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 6th | 7th | 8th | C × G | 6th | 7th | 8th | C × G | |

| Physical Activity | |||||||||

| VPA Blocks | I | 8.68 (0.93) |

10.67 (1.01) |

11.98 (1.12) |

p=.11 | 8.37 (0.92) |

10.30 (1.08) |

12.10 (1.24) |

p=.003 |

| C | 8.41 (0.89) |

11.12 (1.11) |

10.58 (1.07) |

7.68 (0.84) |

11.20 (1.15) |

9.94 (1.04) |

|||

| VPA Standard | I | 56.39 (4.14) |

58.20 (4.08) |

60.07 (4.05) |

p=.91 | 56.62 (4.39) |

58.73 (4.25) |

60.69 (4.19) |

p=.31 |

| C | 54.50 (4.09) |

55.81 (4.08) |

56.50 (4.07) |

53.31 (4.32) |

60.80 (4.18) |

56.60 (4.18) |

|||

| MVPA Blocks | I | 15.23 (1.34) |

16.61 (1.43) |

17.46 (1.49) |

p=49 | 15.26 (1.47) |

16.52 (1.55) |

17.89 (1.65) |

p=.005 |

| C | 14.62 (1.29) |

16.87 (1.43) |

16.62 (1.41) |

14.09 (1.36) |

17.67 (1.62) |

15.94 (1.49) |

|||

| MVPA Stand. | I | 61.98 (4.69) |

62.27 (4.70) |

64.35 (4.59) |

p=.99 | 62.24 (5.16) |

61.62 (5.16) |

65.81 (4.89) |

P=.23 |

| C | 59.74 (4.74) |

59.97 (4.74) |

62.53 (4.63) |

59.32 (5.21) |

64.42 (4.98) |

61.61 (5.08) |

|||

| Fruit and Vegetable | |||||||||

| FV | I | 3.11 (0.20) |

2.91 (0.20) |

2.84 (0.20) |

p=.75 | 3.31 (0.21) |

3.14 (0.21) |

3.08 (0.21) |

p=.99 |

| C | 3.07 (0.19) |

2.89 (0.19) |

2.76 (0.19) |

3.11 (0.20) |

2.93 (0.20) |

2.85 (0.20) |

|||

| Fruit | I | 1.90 (0.11) |

1.76 (0.11) |

1.68 (0.11) |

p=.97 | 2.04 (0.11) |

1.94 (0.11) |

1.87 (0.11) |

p=.99 |

| C | 1.80 (0.10) |

1.68 (0.11) |

1.58 (0.10) |

1.87 (0.11) |

1.77 (0.11) |

1.70 (0.10) |

|||

| Veg. | I | 1.21 (0.10) |

1.14 (0.11) |

1.16 (0.10) |

1.28 (0.11) |

1.17 (0.11) |

1.19 (0.11) |

p=.11 | |

| C | 1.26 (0.10) |

1.20 (0.10) |

1.18 (0.10) |

p=.88 | 1.26 (0.10) |

1.20 (0.10) |

1.21 (0.10) |

||

| Physical Activity Proxy Efficacy For Environmental Change | |||||||||

| Parents | I | 3.71 (.09) |

3.70 (.09) |

3.56 (.09) |

p=.16 | 3.63 (.09) |

3.59 (.09) |

3.48 (.09) |

p=.17 |

| C | 3.75 (.09) |

3.85 (.09) |

3.55 (.09) |

3.66 (.09) |

3.74 (.09) |

3.47 (.08) |

|||

| Peers | I | 3.61 (.08) |

3.70 (.08) |

3.62 (.08) |

p=.44 | 3.53 (.08) |

3.61 (.08) |

3.59 (.08) |

p=.48 |

| C | 3.64 (.08) |

3.85 (.08) |

3.69 (.08) |

3.55 (.81) |

3.74 (.08) |

3.62 (.08) |

|||

| School | I | 2.37 (.07) |

2.52 (.07) |

2.52 (.07) |

p=.001 | 2.34 (.08) |

2.51 (.08) |

2.51 (.08) |

p=.001 |

| C | 2.49 (.07) |

2.47 (.07) |

2.19 (.07) |

2.41 (.08) |

2.40 (.08) |

2.14 (.08) |

|||

| Physical Activity Self Efficacy | |||||||||

| 5-7 days | I | 3.45 (.09) |

3.59 (.10) |

3.50 (.09) |

p=.02 | 3.31 (.09) |

3.51 (.09) |

3.38 (.09) |

p=.02 |

| C | 3.34 (.09) |

3.68 (.09) |

3.69 (.09) |

3.22 (.09) |

3.58 (09) |

3.62 (.09) |

|||

| Physical Activity Group Norm | |||||||||

| I | 3.37 (.07) |

3.50 (.07) |

3.34 (.07) |

p=.49 | 3.25 (.10) |

3.26 (.10) |

3.18 (.10) |

p=.66 | |

| C | 3.37 (.07) |

3.50 (.07) |

3.44 (.07) |

3.31 (.09) |

3.41 (.09) |

3.27 (.09) |

|||

| Fruit and Vegetable Proxy Efficacy For Environmental Change | |||||||||

| Parents | I | 3.60 (.12) |

3.45 (.12) |

3.29 (.12) |

p=.27 | 3.42 (.10) |

3.40 (.10) |

3.30 (.10) |

p=.28 |

| C | 3.49 (.12) |

3.48 (.12) |

3.38 (.12) |

3.55 (.11) |

3.38 (.10) |

3.23 (.10) |

|||

| School | I | 2.48 (.08) |

2.35 (.08) |

2.33 (.08) |

p=.71 | 2.44 (.09) |

2.32 (.09) |

2.31 (.09) |

p=.65 |

| C | 2.36 (.08) |

2.30 (.08) |

2.19 (.08) |

2.32 (.09) |

2.27 (.09) |

2.16 (.09) |

|||

| Fruit and Vegetable Self-efficacy | |||||||||

| 5 to 7 Servings |

I | 2.82 (.10) |

2.72 (.10) |

2.69 (.11) |

p=.28 | 2.88 (.12) |

2.68 (.12) |

2.66 (.12) |

p=.04 |

| C | 2.59 (.10) |

2.69 (.10) |

2.53 (.10) |

2.53 (.11) |

2.67 (.12) |

2.49 (.11) |

|||

| Fruit and Vegetable Group Norm | |||||||||

| I | 2.60 (.07) |

3.21 (.07) |

3.22 (.07) |

p=.05 | 2.60 (.07) |

3.44 (.07) |

3.36 (.07) |

p=.03 | |

| C | 2.63 (.06) |

3.46 (.07) |

3.38 (.07) |

2.60 (.07) |

3.19 (.07) |

3.20 (.07) |

|||

I= Intervention Condition (N=684 Analyzed For MVPA; N=617 Analyzed for fruit and vegetable consumption; The other variables N varied slightly due to missing data).

C= Control Condition (N=716 Analyzed for MVPA, N=715 for fruit and vegetable consumption, The other variables N varied slightly due to missing data).

References

- Bandura A. Adolescent development from an agentic perspective. In: Pajares F, Urdan T, editors. Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents. Information Age Publishing; Greenwich, Connecticut: 2006. pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Baranowski T, Baranowski J, Cullen KW, Marsh T, Islam N, Zakeri I, et al. Squire's Quest! Dietary outcome evaluation of a multimedia game. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2003;24:52–61. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00570-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman KJ, Tiller CL, Sanchez J, Heath EM, Sy O, Milliken G, et al. Prevention of the epidemic increase in child risk of overweight in low-income schools: the El Paso coordinated approach to child health. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159:217–224. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.3.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzewaltowski DA, Estabrooks PA, Johnston JA. Healthy youth places promoting nutrition and physical activity. Health Education Research. 2002;17:541–551. doi: 10.1093/her/17.5.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzewaltowski DA, Karteroliotis K, Welk G, Johnston JA, Nyaronga D, Estabrooks PA. Measurement of self-efficacy and proxy efficacy for middle school youth physical activity. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 2007;29:310–332. doi: 10.1123/jsep.29.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett SB, Sterling TD, Paine-Andrews A, Harris KJ, Francisco VT, Richter PP, et al. Evaluating community efforts to prevent cardiovascular disease. Centers for Disease Control; Atlanta, Georgia: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gyurcsik NC, Dzewaltowski DA, Karteroliotis K, Estabrooks PA, Hill JL. Self-efficacy as a determinant of fruit and vegetable consumption in middle school children: Measurement and predictive validity. Annals of Behavior Medicine. 2002 April;24(Supplement):S136. [Google Scholar]

- Kimm SY, Glynn NW, Kriska AM, Barton BA, Kronsberg SS, Daniels SR, et al. Decline in physical activity in black girls and white girls during adolescence. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347:709–715. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klar N, Donner A. Current and future challenges in the design and analysis of cluster randomization trials. Statistics in Medicine. 2001;20:3729–3740. doi: 10.1002/sim.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krull JL, MacKinnon DP. Multilevel modeling of individual and group level mediated effects. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2001;36:249–277. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3602_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lien N, Lytle LA, Klepp KI. Stability in consumption of fruit, vegetables, and sugary foods in a cohort from age 14 to age 21. Preventive Medicine. 2001;33:217–226. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littell R,C, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD. SAS system for mixed models. SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, N.C.: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lytle LA, Murray DM, Perry CL, Story M, Birnbaum AS, Kubik MY, et al. School-based approaches to affect adolescents' diets: Results from the TEENS study. Health Education and Behavior. 2004;31:270–287. doi: 10.1177/1090198103260635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science. 2000;1:173–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1026595011371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milliken GA, Johnson DE. Analysis of messy data: Analysis of covariance. III. Chapman & Hall/CRC; Boca Raton: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Murray DM, Varnell SP, Blitstein JL. Design and analysis of group-randomized trials: A review of recent methodological developments. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:423–432. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pate RR, Ward DS, Saunders RP, Felton G, Dishman RK, Dowda M. Promotion of physical activity among high-school girls: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:1582–1587. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.045807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds KD, Yaroch AL, Franklin FA, Maloy J. Testing mediating variables in a school-based nutrition intervention program. Health Psychology. 2002;21:51–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockett HRH, Breitenbach M, Frazier AL, Witschi J, Wolf AM, Field AE, et al. Validation of a youth/adolescent food frequency questionnaire. Preventive Medicine. 1997;26:808–816. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockett HRH, Colditz GA. Evaluation of dietary assessment instruments in adolescents. Current Opinion in Clincal Nutrtion and Metabolic Care. 2003;6:557–562. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200309000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan GJ, Dzewaltowski DA. Relationships among types of self-efficacy and after-school physical activity in youth. Health Education and Behavior. 2002;29:491–504. doi: 10.1177/109019810202900408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, McKenzie TL, Conway TL, Elder JP, Prochaska JJ, Brown M, et al. Environmental interventions for eating and physical activity: A randomized controlled trial in middle schools. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2003;24:209–217. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00646-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders RP, Pate RR, Felton G, Dowda M, Weinrich MC, Ward DS, et al. Development of questionnaires to measure psychosocial influences on children's physical activity. Preventive Medicine. 1997;26:241–247. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J, Murray DM, Catellier DJ, Hannan PJ, Lytle LA, Elder JP, et al. Design of the Trial of Activity in Adolescent Girls (TAAG) Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2005;26:223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telama R, Yang X, Viikari J, Valimaki I, Wanne O, Raitakari O. Physical activity from childhood to adulthood: a 21-year tracking study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;28:267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welk GJ, Dzewaltowski DA, Hill JL. Comparison of the computerized ACTIVITYGRAM instrument and the previous day physical activity recall for assessing physical activity in children. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 2004;75:370–380. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2004.10609170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston AT, Petosa R, Pate RR. Validation of an instrument for measurement of physical activity in youth. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1997;29:138–143. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199701000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]