Abstract

Aims:

To explore the developmental relationships between early-onset depressive disorders and later use of addictive substances.

Design, Setting, Participants:

A sample of 1545 adolescent twins was drawn from a prospective, longitudinal study of Finnish adolescent twins with baseline assessments at age 14 and follow-up at age 17.5.

Measurements:

At baseline, DSM-IV diagnoses were assessed with a professionally administered adolescent version of Semi-Structured Assessment for Genetics of Alcoholism (C-SSAGA-A). At follow-up, substance use outcomes were assessed via self-reported questionnaire.

Findings:

Early-onset depressive disorders predicted daily smoking (odds ratio 2.29, 95%CI 1.49-3.50, p<.001), smokeless tobacco use (OR = 2.00, 95%CI 1.32-3.04, p=.001), frequent illicit drug use (OR = 4.71, 95%CI 1.95-11.37, p=.001), frequent alcohol use (OR = 2.02, 95%CI 1.04-3.92, p=.037) and recurrent intoxication (OR = 1.83, 95%CI 1.18-2.85, p=.007) three years later. Odds ratios remained significant after adjustment for comorbidity and exclusion of baseline users. In within-family analysis of depression-discordant co-twins (analyses that control for shared genetic and familial background factors), early-onset depressive disorders at age 14 significantly predicted frequent use of smokeless tobacco and alcohol at age 17.5.

Conclusions:

Our results suggest important predictive associations between early—onset depressive disorders and addictive substance use, and these associations appear to be independent of shared familial influences.

Keywords: Adolescent, early-onset depression, substance use, familial factors

Introduction

Our knowledge of the prospective association between two major public health problems of adolescents, depression and the use of addictive substances, remains limited. Externalizing behavior problems, including conduct disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity, and oppositional defiant disorder, have been identified as strong predisposing risk factors for later substance use [1], but the role of internalizing disorders, namely depression and anxiety disorders, is less studied. Prospective studies of the association of depressive disorders with substance use in adolescence warrant study, given the high prevalence of depressive disorders observed among youth with substance use disorders in both clinical and non-clinical populations [2]

Previous research on relationships between depression and smoking in adolescence has suggested bi-directional causation [1, 3-8] and reciprocal relationships [9]. Other hypotheses, e.g., depression enhances genetic predispositions for smoking, emphasize the importance of early-onset depression in developmental trajectories of substance use [10].

Smokeless tobacco use in adolescence has been infrequently studied, but smokeless tobacco is used in early adolescence, and efforts to ban it in some countries, including Finland, have not restricted its use [11]. Adverse physical health-related consequences of smokeless tobacco use are well understood, but whether it potentially contributes to nicotine dependence is, surprisingly, unknown [12]. Cross-sectional designs suggest that smokeless tobacco may associate with mood-related symptoms [13, 14].

Several studies have reported on early drug use as a predictor of depression [15-17], but the role of adolescent depression as a risk factor for later drug use has received less attention. However, a preliminary finding among adolescents in residential treatment showed that baseline depressive symptoms predicted poor substance use treatment outcome [18]. Further, childhood symptoms of depression and anxiety were associated with ecstasy use in adolescents and adults in a population-based Dutch sample [19].

Understanding the nature of the relationship between alcohol use and depressive disorders in adolescence is crucial, because both have been postulated as risk factors for suicidality among adolescents [20]. From an etiological perspective, alcohol may be consumed because of expectations that it relieves depressive mood, a hypothesis described as a negative affect regulation model or self-medication [21]. Previous studies suggest that early symptoms of depression may associate also with later alcohol use in children and adolescents [22, 23], but perhaps, only when associated with high levels of conduct disorder symptoms [24].

Besides causal models, common underlying factors may underlie the observed associations between depression and substance use in adolescence. For example, twin studies from adult populations, including a causal analysis of depression and smoking by Kendler et al 1993 [25], have demonstrated the importance of genetic effects underlying this association. Thus, it is of importance to enhance understanding of the role of familial factors, such as childhood environment or dispositional genetic factors, in these developmental relationships. One approach is to study outcomes among co-twins from pairs discordant for both the predictor (e.g., early-onset depression) and outcome (e.g., substance abuse), an approach that affords an elegant opportunity to control between family confounds of family structure, status, and medical history.

Using prospective and longitudinal data, our purpose was to examine whether early-onset depressive disorders predict future health adverse behaviors: smoking behavior, smokeless tobacco use, illicit drug use, frequent alcohol use and frequent intoxication. We complemented the analysis of twins as individuals by studying co-twins discordant for depression, to ask whether these predictive relationships replicate when controlling for shared genetic and familial background influences.

Methods

FinnTwin 12 Study Design

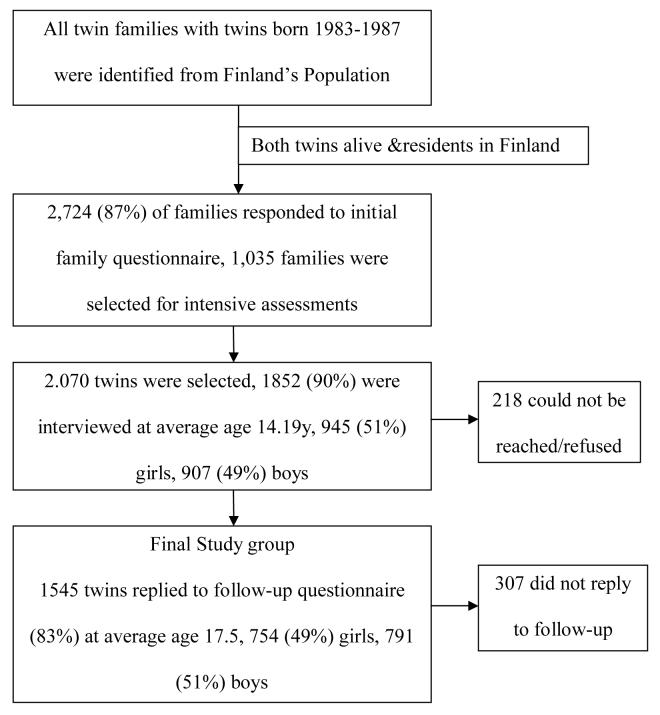

FinnTwin12 (FT12) is an ongoing longitudinal twin study launched in 1994 to investigate the developmental genetic epidemiology of health-related behaviors [26]. An overview of the sampling strategy is presented as Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flow Chart. Data collection and sampling in Finnish Twin Cohort.

From 1994 to 1998, all Finnish families with twins born in 1983-87 were identified from Finland's Population Register Centre and enrolled into a two-stage sampling design [27]. The first-stage study included questionnaire assessments of all twins and parents at baseline (87% participation rate, 2,724 families) conducted during the late autumn of the year in which consecutive twin cohorts reached 11 years, with follow-up of all twins at ages 14 and 17½. Nested within this population representative study was an intensive assessment of a sub-sample of 1035 families, comprising about 40% of all twins, most (72.3%; 748 families) selected at random. About one-quarter of the sub-sample (27.7%; 287 families) was enriched with twins assumed to be at elevated familial risk for alcoholism, based on one or both parents' elevated scores on an 11-item lifetime version of the Malmö-modified Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test [28]. Details about the sub-sample have been described earlier [26]. We report analysis of the full sample to retain statistical power, because results of random sub-set and total sample did not differ significantly from each other (tabular comparison data available on request).

Both co-twins and their parents from this sub-sample were interviewed using the SSAGA (Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism) [29], a widely-used, reliable instrument providing lifetime diagnoses for alcohol dependence, major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and eating disorders. Assessments of non-responders at each stage revealed no evidence of selection associated with family structure, parental age, residential area, type or sex of the twins, or other systematic bias. All interviewers had previous interview experience and were Masters of Psychology, Health Care, or registered nurses; they were trained at Indiana University's Institute of Psychiatric Research using standard COGA-interview training procedures [30]. The mean age at interview was 14.19 years, with 75% of interviews completed between 14.0 and 14.3 months of age, and all interviews completed before age 15. The final interview sample (1852) consisted of 945 boys (51%) and 907 girls (49%), a participation rate of 90%.

Subsequently, during 2000 - 2005 at the average age of 17½, twin participants from all five birth cohorts were approached again with a mailed follow-up questionnaire including substance use assessments. A total of 1545 interviewed adolescents (83% participation rate) born 1983-87 replied at age 17 (754 females, 49% and 791 males, 51%). Non-respondents did not significantly differ from respondents in baseline depression status, sex, or age. Zygosity of twins was determined from well-validated questionnaire method supplemented by information from parents, photographs and genotyping [31, 32, 30]. Data collection procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Helsinki and by the Institutional Review Board of Indiana University, Bloomington.

Baseline Assessments

Depressive disorders

The Finnish translation of the adolescent SSAGA (C-SSAGA-A) yields diagnostic information on all criteria of DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn) major depressive disorder (MDD) [33]. Because of the low prevalence of DSM-IV MDD, (2.32%) and the clinical significance of minor depressive disorder in adolescents [34-36], we chose to include minor depressive disorder cases along with major depressive disorder cases in our analyses under the heading Depressive Disorder (DD). Minor depressive disorder (MD) was defined as meeting all criteria for MDD, except for the number of symptoms required. MD required the presence of at least two symptoms of MDD, one of them being depressed/irritable mood or anhedonia nearly every day for at least two weeks, and excluding adolescents with a previous history of DSM-IV MDD or dysthymia (presence of depressed/irritable mood nearly every day over a year and a report of at least two additional symptoms). All cases of depressive disorders were classified as early-onset depressive disorder cases, (age of onset between 5 to 14 years) [36].

Psychiatric diagnoses and covariates

Other major types of disorders including generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), attention-defiant-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD), as well as alcohol abuse and dependence diagnoses, were assessed according to DSM-IV criteria without considering impairment. Smoking, smokeless tobacco and illicit drug use were each analyzed in multi-item sections in the same interview.

The assessments of substance use at follow-up

Outcome variables at age 17½ were based on self-report questionnaire including detailed questions about substance use:

Smoking behavior

“Have you ever tried smoking” and a multi-categorical follow-up: “Which of the following best describes your current smoking”. The response alternatives were: 1) I smoke 20 cigarettes or more/day; 2)10-19 cigarettes/day; 3)1-9 cigarettes/day; 4) I smoke once a week or more often, not daily; 5) I smoke less than once a week; 6) I'm no longer smoking; and 7) I have experimented with smoking, but I don't smoke. Alternatives 1, 2 and 3 were defined as daily smokers, 4 and 5 as occasional smokers; and 7 as experimenters. In multinomial regressions, the never smokers formed the reference group. In final models, when excluding previous users, the adolescents who were not currently smoking (6) were also excluded to avoid the inclusion of potential former heavy smokers.

Smokeless tobacco use

“Have you ever tried smokeless tobacco? How many times so far?” The alternatives were 1) No, I haven't (defined as abstainers); 2) once (defined as experimenters); 3) 2-50 times; 4) more than 50 times; and 5) I use smokeless tobacco regularly. Alternatives 3), 4) and 5) were considered users. Those who had never used smokeless tobacco were defined as abstainers and formed the reference group.

Illicit drug use

“Have you ever tried illicit drugs (marijuana, hash or similar drugs). Response options were: 1) never (abstainers); 2) 1-3 times (experimenters); 3) 4-9 times or 10-19 times (moderate use); and 4) more than 20 times (frequent use). In multinomial regressions, the abstainers formed the reference group.

Alcohol use frequency and intoxication

“How often do you use alcohol, even in small amounts, like half a bottle of beer or a sip of wine?” and “How often do you use so much alcohol that you become intoxicated?” Nine response options were given: 1) daily; 2) a couple times a week; 3) once a week; 4) a couple times in a month; 5) once a month; 6) once in a couple months; 7) 2-4 times a year; 8) once a year or more rarely; and 9) I don't use alcohol. In multinomial analyses, since only one person reported daily alcohol use, categories 1) and 2) were collapsed as frequent users; 3), 4) and 5) as moderate users; 6), 7) and 8) as occasional users; and 9) as abstainers. To assess intoxication, alternatives 1), 2), and 3) were considered frequent intoxication, 4), 5) and 6) were considered recurrent and 7), 8) as occasional intoxication. In both drinking frequency and frequency of intoxication, alternative 9) was considered as abstaining and non-intoxicating, respectively, and used as reference category.

Statistical Analysis

Univariate and multivariate associations of baseline early depressive disorders with follow-up substance use were examined with multinomial logistic regression using never-users as the reference group. To investigate whether these associations replicate after controlling for shared genes and shared family environments, including differences in family structure, status, parenting styles, parental models and family history, conditional logistic regression analyses were conducted among all informative twin pairs discordant for both predictor (early-onset depressive disorders at 14) and follow-up outcome (substance use/abuse at 17½).

First, a multinomial logistic regression model to study the association of depressive disorder with the outcomes was examined. Second, potential confounding covariates (baseline alcohol use disorders, smoking, smokeless tobacco use, and illicit drug use) and comorbid psychiatric disorders were added to the model. Finally, to investigate whether depressive disorders also predicted substance use in those who were not users at baseline, users of each outcome variable in question, (for example, smokers at baseline when predicting future smoking) were excluded from the analysis. The same protocol was used in conditional logistic regression, with conditioning on the twin pair. Odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals were calculated and are reported.

In analysis of twins as individuals, p-values and confidence intervals were adjusted using standard procedures for survey data [37] to correct for the non-independence of observations within twin pairs. All full models are available from first author at request. Analyses were conducted using the statistical software Stata 9.2.

Results

The prospective analysis of early-onset depressive disorders and use of addictive substances

Early onset depressive disorder predicted elevated levels of use for five measured outcomes of substance use/abuse at age 17½. Table 1 presents the distribution of the five outcomes at age 17½ (smoking behavior, smokeless tobacco use, illicit drug use, alcohol use and intoxication frequency) by depressive disorder status at baseline age 14. Thus, to cite an example, 39% of adolescent twins with depressive disorders at age 14 reported daily smoking at age 17½, compared to 26% of adolescents without baseline depressive disorders, a 1.5 elevation in risk; 30.5% of those without DD at baseline reported they were never smokers at follow-up, compared to less than 20% of those with baseline DD. Similarly, frequent use of illicit drugs at age 17 was elevated 3.6 times among those with DD at age 14. Overall, early-onset depressive disorders were robustly associated with elevated levels of addictive substance use, and, with but one exception, DD elevated prevalence of substance use/abuse consistently among both women and men.

Table 1.

Distribution of smoking behavior, smokeless tobacco use, illicit drug use and alcohol use at three-year-follow-up (mean age 17.5) among adolescents with and without depressive disorders (DD, DSM-IV major or minor depressive disorder) at baseline age 14.

| DD at Baseline | No baseline DD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| females | males | all | females | males | all | |

| Smoking behavior |

||||||

| Never-smokers | 18.8% | 22.2% | 19.9% | 29.4% | 31.5% | 30.5% |

| Experimentation | 32.9% | 27.8% | 31.2% | 33.4% | 33.6% | 33.5% |

| Occasional | 9.4% | 9.7% | 9.5% | 11.2% | 9.0% | 10.0% |

| Daily1 | 38.9% | 40.3% | 39.4% | 26.0% | 25.9% | 26.0% |

| Smokeless tobacco |

||||||

| Never | 76.0% | 50.0% | 67.6% | 87.8% | 61.7% | 74.4% |

| Experimentation | 15.3% | 11.1% | 14.0% | 7.3% | 11.7% | 9.6% |

| Use | 8.7% | 38.9% | 18.5% | 4.9% | 26.6% | 16.0% |

| Illicit drug use |

||||||

| Never | 74.7% | 86.0% | 78.4% | 87.1% | 88.1% | 87.6% |

| Experimentation | 17.3% | 5.6% | 13.5% | 9.1% | 8.2% | 8.6% |

| Moderate (4-19 times) | 4.7% | 4.2% | 4.5% | 3.4% | 2.2% | 2.8% |

| Frequent (>20 times) | 3.3% | 4.2% | 3.6% | 0.5% | 1.5% | 1.0% |

| Alcohol use |

||||||

| Abstainers | 10.7% | 5.5% | 9.0% | 11.5% | 12.5% | 12.0% |

| Occasional | 21.3% | 27.8% | 23.4% | 25.2% | 21.5% | 23.3% |

| Moderate | 60.0% | 51.4% | 57.2% | 56.9% | 57.9% | 57.4% |

| Frequent2 | 8.0% | 15.3% | 10.4% | 6.4% | 8.1% | 7.3% |

| Intoxication |

||||||

| Never | 16.7% | 11.1% | 14.9% | 21.9% | 19.2% | 20.5% |

| Occasional | 26 .7% | 23.6% | 25.7% | 31.8% | 27.9% | 29.8% |

| Recurrent3 | 50.0% | 59.7% | 53.2% | 39.4% | 45.4% | 42.5% |

| Frequent | 6.6% | 5.6% | 6.2% | 6.9% | 7.5% | 7.2% |

1-20 cigarettes or more/day

at least a couple times a week or daily

a couple times in a month to at least once in a couple months

Results of multinomial logistic regression analyses of early-onset depressive disorders as predictors of substance use at age 17.5 are presented in Table 2. Two models were used. Model 1, which adjusted for sex differences and clustered sampling of twins, shows that at three-year follow-up, early-onset depressive disorders strongly predicted all later substance use. Model 2 reports results of a model that adjusted for other early-onset psychiatric disorders, as well as all other types of previous substance use, and excluded all participants with previous use of a particular substance, for example previous smokers. Results from Model 2 suggest that depression predicted future daily smoking even among those who were not daily smokers at baseline. Similar patterns of significant associations after excluding baseline users were observed for smokeless tobacco use, frequent illicit drug use, frequent alcohol use and recurrent intoxication among adolescents.

Table 2.

The Odds Ratios of multi-level smoking status, illicit drug use, smokeless tobacco use, alcohol frequency and intoxication at follow-up (age 17.5) according to early-onset depressive disorders at baseline (age 14) among Finnish twins born 1983-87(N=1545).

| Model 1 (Bivariate OR, 95%CI) |

Model 2 (Multivariate OR, 95%CI) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | p | OR | 95%CI | p | |

| Smoking behavior | ||||||

| Never-smokers | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Experimentation | 1.40 | .91-2.16 | .127 | 1.28 | .82-2.02 | .278 |

| Occasional | 1.37 | .77-2.44 | .278 | 1.27 | .68-2.36 | .453 |

| Daily 1 | 2.29 | 1.49-3.50 | <.001 | 2.14 | 1.33-3.45 | .002 |

| Smokeless tobacco use | ||||||

| Never-users | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Experimentation | 1.88 | 1.20-2.96 | .006 | 1.71 | 1.04-2.80 | .035 |

| Use | 2.00 | 1.32-3.04 | .001 | 2.08 | 1.31-3.29 | .002 |

| Illicit drug use | ||||||

| Never-users | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Experimentation | 1.66 | 1.05-2.64 | .030 | 1.38 | .85-2.25 | .191 |

| Moderate (4-19 times) | 1.67 | .80-3.45 | .169 | 1.00 | .41-2.40 | .995 |

| Frequent (>20 times) | 4.71 | 1.95-11.37 | .001 | 3.75 | 1.07-13.21 | .039 |

| Alcohol use | ||||||

| Abstainers | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Occasional | 1.31 | .75-2.31 | .344 | 1.31 | .73-2.37 | .355 |

| Moderate | 1.32 | .80-2.20 | .279 | 1.24 | .73-2.11 | .419 |

| Frequent 2 | 2.02 | 1.05-3.91 | .036 | 2.14 | 1.00-4.57 | .049 |

| Intoxication | ||||||

| Never | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Occasional | 1.19 | .73-1.95 | .481 | 1.17 | .71-1.95 | .533 |

| Recurrent 3 | 1.83 | 1.18-2.85 | .007 | 1.65 | 1.04-2.62 | .034 |

| Frequent | 1.26 | .62-2.58 | .526 | .99 | .43-2.27 | .973 |

Abbreviations: CI=Confidence Intervals; OR=Odds Ratios.In all models, the abstainers/never users were used as reference category.

1-20 cigarettes or more/day

at least a couple times a week or daily

a couple times in a month to at least once in a couple months. All analysis adjusted for demographics (sex, age), multivariate analyses adjusted also for baseline risk behaviors and other psychopathology. In multivariate analysis, users at baseline (daily smokers, smokeless tobacco users, illicit drug users and subjects with alcohol use disorders) were excluded from the analysis.

Substance use outcome among adolescent twin pairs discordant for early-onset depressive disorders

In the total sample, 150 twin pairs were discordant for baseline early-onset depressive disorders (i.e., one twin in each pair met criteria for DD while the co-twin did not); these 150 pairs formed the target study group for our within pair-analysis. Among these 150 pairs, we then identified the subset of pairs discordant as well for each substance use outcome at follow-up, asking of these informative pairs, whether it was the depressed co-twin that exhibited substance use/abuse at follow-up. For example, 46 of the 150 twin pairs discordant for depressive disorder at age 14 were discordant as well for daily smoking at age 17.5. And in 30 of these 46 doubly discordant twin pairs, the co-twin depressed at baseline was the daily smoking twin at follow-up (30/16 = unadjusted odds ratio = 1.875). We then employed conditional logistic regression models to adjust these odds ratios for sex differences and observed (Table 3) significant sex-adjusted associations for smokeless tobacco and frequent alcohol use. Additional conditional logistic regression analyses demonstrated that the relationships with smokeless tobacco and frequent alcohol use remained significant after excluding the opposite-sex twin pairs. Reflecting the moderately high twin correlations invariably observed for adolescent substance use, only a limited number of twin pairs were discordant for several measured outcomes (as few as 16 of the 150 pairs discordant for baseline DD), constraining power of our discordant twin analysis. But these within-family replications of results of analyses of twins as individuals offer incisive control for familial confounds, including family structure, status, and parental history. Results from twin discordant for baseline depressive disorder confirm that early-onset depressive disorders significantly predict smokeless tobacco use and frequent alcohol use after ruling out familial 3rd variable confounds.

Table 3.

Substance use outcomes at age 17.5 in twin pairs (N=150 pairs) discordant for Early-Onset Depressive Disorders and substance use at follow-up.

| No. of pairs* |

OR | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily Smoking | 32/46 | 1.83 | .98-3.42 |

| Smokeless Tobacco | 19/32 | 5.63 | 1.27-24.8 |

| Drug Use | 11/16 | 1.67 | .40-6 97 |

| Frequent Alcohol Use | 14/22 | 3.75 | 1.07-13.20 |

| Regular Drunkenness | 31/56 | 1.43 | .82-2.53 |

Abbreviations: CI=Confidence Intervals; OR=Odds Ratios.

Fraction of pairs discordant both for depressive disorder at baseline and substance use at follow-up in which the co-twin depressed at baseline was the twin who met the substance use outcome. For smokeless tobacco use, this fraction was 4 of 4 sister-sister pairs and 7 of 9 brother-brother-pairs, but only 8 of 19 sister-brother twin pairs.

The odds ratios were calculated using conditional logistic regression. The odds ratios were adjusted for sex, other covariates examined were conduct disorder, attention-deficit (ADHD), oppositional-deficit (ODD), substance use and generalized anxiety disorders, but none were significant predictors. All models excluded baseline users.

Discussion

Results of this prospective longitudinal study show that depressive disorders at age 14 were positively associated with elevated levels of later addictive substance use, in both boys and girls and even among those who were not users at baseline. Analysis of twins discordant for early-onset depressive disorders confirm predictive associations of early-onset depressive disorders with smokeless tobacco use and frequent drinking at age 17½, in within-family replications with co-twins matched on half or all their segregating genes, and on their family structure, socioeconomic status, and household environment.

Recent findings suggest the importance of baseline depression to smoking initiation within a 1-year follow-up period [38]. In comparison, our study demonstrates the association of early depressive disorders to progression of daily smoking at a 3-year follow-up. Thus, our results add new evidence that the relationship of depressive disorders and smoking in adolescence may be an important factor in the developmental pathway of persistent smoking behavior.

This study demonstrates that smokeless tobacco use has similarities to other forms of tobacco use, and that early-onset depression may enhance vulnerability to smokeless tobacco use in later adolescence. Because of the central role of nicotine in the neurobiology of nicotine dependence and continued tobacco use [39], symptoms of dependence can probably develop very quickly in smokeless tobacco users in the same way that symptoms of dependence develop very quickly in adolescent smokers [40]. In addition to prospective relationship of depression to later smokeless tobacco use, this is, to our knowledge, the first study reporting that the predictive association of depression and smokeless tobacco remained after controlling for familial confounds. This novel finding suggests that influences other than family environments, for example, the influence of peers or dispositional personality traits on this health-adversing behavior may be of importance in this association.

In this study, early-onset depressive disorders predicted advanced drug use 3 ½ years later. However, many cases with future illicit drug use were minor depressive disorder cases; by addressing the broader phenotype of adolescent depression, our results suggest the clinical significance of sub-threshold cases in adolescence. The association with early-onset depressive disorders and illicit drug use was non-significant in twin pairs discordant for early-onset depressive disorders, but the limited number of discordant pairs for these analyses warrants caution. However, based on previous research regarding cannabis use and depression [16], familial factors are likely to partly explain the association of adolescent depression and multiform illicit drug use.

Given the strong association between alcohol use and smoking at both the societal and biological levels [41], teasing apart smoking effects from alcohol effects is difficult. However, our findings of positive associations of alcohol frequency and recurrent intoxication reflect potential hazardous drinking habits among depressed adolescents. Significant association in discordant twins suggested that the association is not accounted for by common familial factors.

Using age-standardized, large-sample prospective twin data from adolescent boys and girls, this study has many important strengths. First, many other studies have used self-report measures instead of professionally administered interviews to assess depressive disorders in adolescence. Second, we controlled for comorbidity, which is of importance because evidence suggests linkage of substance use to several psychiatric disorders, especially externalizing disorders, Third, our within-family analysis of depression-discordant twin pairs offered us an incisive control of the role of familial factors in these developmental relationships.

Yet our study also has limitations, and these should be taken into account when assessing generalizability of our results: Bipolar disorder is uncommon at this age [42], but it was not covered by the interview. The assessment of substance use outcomes at age 17½ was based on self-reports, vulnerable to self-report bias. Further, although our analyses of depression-discordant co-twins represents a new, and perhaps important effort in understanding the association of early-onset depressive disorders and substance use in the context of familial confounds, our sample of doubly discordant twin pairs was limited: our results are more suggestive than definitive. We confirmed significant associations of early-onset depressive disorders and use of smokeless tobacco and alcohol, but given the small number of informative twin pairs, the lack of association for other outcomes should not be interpreted as evidence that familial confounds underlie those associations. Finally, a small part of the sub-sample of twins we studied was enriched for alcoholism risk. However, we have performed a series of model-fitting analyses to diverse phenotypes to test for potential bias introduced by the sample enrichment, and we find no evidence that model-fitting results were systematically affected [43]. Nor do direct comparisons of the sub-samples suggest bias.

In the context of our study's strengths and limitations, results highlight the importance of early-onset depressive disorders in the development of substance use. In particular, since the predictive relationships were significant among those who were not users at baseline, early-onset depressive disorders may have an important role in the developmental pathway of progression of substance use to substance dependence later in life. This study suggests, if not confirms, that predictive associations between early-onset depressive disorders and smokeless tobacco use and early-onset depressive disorders and alcohol use are not explained by differences in the familial environments supporting future substance use in youth. If confirmed, these novel findings have important implications for educational purposes in treatment and prevention programs in adolescent health care.

Acknowledgements

Finnish Graduate School of Psychiatry (ES), The Centre of Excellence in Complex Disease Genetics, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA-12502 and AA-09203 to RJR), the Academy of Finland (100499, 205585, and 118555 to JK) and Yrjo Jahnsson Foundation.

References

- 1.King SM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Childhood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology in the prediction of early substance use. Addiction. 2004;99:1548–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kandel DB, Johnson JG, Bird HR, Weismann MM, Goodman SH, Lahey BB, Regier DA, Schwab-Stone ME. Psychiatric comorbidity among adolescents with substance use disorders: findings from the MECA study. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1999;38:693–9. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu L, Anthony JC. Tobacco smoking and depressed mood in late childhood and early adolescence. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1837–40. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.12.1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodman E, Capitman J. Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking among teens. Pediatrics. 2000;106:748–55. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.4.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patton GC, Carlin JB, Coffey C, Wolfe R, Hibbert M, Bowes G. Depression, anxiety, smoking initiation: a prospective study over 3 years. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1518–22. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.10.1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang MQ, Fitzhugh EC, Green BL, Turner LW, Eddy JM, Westerfield RC. Prospective social-psychological factors of adolescent smoking progression. J Adolesc Health. 1999;24:2–9. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rice F, Lilford KJ, Thomas HV, Thapar A. Mental Health and functional outcomes of maternal and adolescent reports of adolescent depressive symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;36:1162–70. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3180cc255f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dierker LC, Vesel F, Sledjeski EM, Costello D, Perrine N. Testing the dual pathway hypothesis to substance use in adolescence and young adulthood. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87:83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Windle M, Windle RC. Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking among middle adolescents: prospective associations and intrapersonal and interpersonal influences. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:215–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Audrain-McGovern J, Lerman C, Wileyto EP, Rodriguez D, Shields PG. Interacting Effects of Genetic Predisposition and Depression on Adolescent Smoking Progression. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1224–30. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huhtala HS, Rainio SU, Rimpela AH. Adolescent snus use in Finland in 1981-2003: trend, total sales ban and acquisition. Tob Control. 2006;15:392–7. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.015313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haukkala A, Vartiainen E, de Vries H. Progression of oral snuff use among Finnish 13-16-year-old students and its relation to smoking behavior. Addiction. 2006;101:581–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coogan PF, Geller A, Adams M. Prevalence and correlates of smokeless tobacco use in a sample of Connecticut students. J Adolesc. 2000;23:129–35. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tercyak KP, Audrain J. Psychosocial correlates of alternate tobacco product use during early adolescence. Prev Med. 2002;35:193–8. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brook JS, Cohen P, Brook DW. Longitudinal study co-occurring psychiatric disorders and substance use. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:322–30. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199803000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lynskey MT, Glowinski AL, Todorov AA, Bucholz KK, Madden PA, Nelson EC, et al. Major depressive disorder, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt in twins discordant for cannabis dependence and early-onset cannabis use. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1026–32. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayatbakhsh MR, Najman JM, Jamrozik K, Mamun AA, Alati R, Bor W. Cannabis and anxiety and depression in young adults: a large prospective study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:408–17. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31802dc54d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subramaniam G, Stitzer M, Clemmey P, Kolodner K, Fishman M. Baseline Depressive Symptoms Predict Poor Substance Use Outcome Following Adolescent Residential Treatment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:1062–1069. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31806c7ad0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huizink AC, Ferdinand RF, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in childhood and use of MDMA: prospective, population based study. BMJ. 2006;332:825–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38743.539398.3A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galaif ER, Sussman S, Newcomb MD, Locke TF. Suicidality, depression, and alcohol use among adolescents: a review of empirical findings. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2007;19:27–35. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2007.19.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sher K, Grekin E, Williams N. The development of alcohol use disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2004;1:493–523. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumpulainen K, Roine S. Depressive symptoms at the age of 12 years and future heavy alcohol use. Addict Behav. 2002;27:425–36. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00182-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu L, Anthony JC. Tobacco smoking and depressed mood in late childhood and early adolescence. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1837–1840. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.12.1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pardini D, White HR, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Early adolescent psychopathology as a predictor of alcohol use disorders by young adulthood. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(Suppl 1):38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kendler KS, Neale MC, MacLean CJ, et al. Smoking and major depression. A causal analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:36–43. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820130038007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rose RJ, Dick DM, Viken RJ, Kaprio J. Drinking or abstaining at age of 14? A genetic epidemiological study. Alcohol Clin. Exp Res. 2001;25:1594–1604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaprio J, Pulkkinen L, Rose RJ. Genetic and Environmental Factors in Health-related behaviors: Studies on Finnish twins and twin families. Twin Res. 2002;5:366–71. doi: 10.1375/136905202320906101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seppa K, Sillanaukee P, Koivula T. The efficiency of a questionnaire in detecting heavy drinkers. Br J Addict. 1990;12:1639–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1990.tb01654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buzholz KK, Cadoret R, Cloninger CR, Dinwiddie SH, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JI, Jr., et al. A new, semi-structured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: a report on the reliability of the SSAGA. J Stud Alcohol. 1994;55:149–58. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edenberg HJ. The collaborative study on the genetics of Alcoholism: an update. Alcohol Res. Health. 2002;26:214–218. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaprio J, Rimpela A, Winter T, Viken RJ, Rimpela M, Rose RJ. Common genetic influences on BMI and age at menarche. Human Biology. 1995;67:739–753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldsmith HH. A zygosity questionnaire for young twins: A research note. Behavior Genetics. 1991;21:257–269. doi: 10.1007/BF01065819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th edn (DSM-IV) American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kessler RC, Walters EE. Epidemiology of DSM-III-R major depression and minor depression among adolescents and young adults in the National Comorbidity Survey. Depress Anxiety. 1998;7:3–14. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6394(1998)7:1<3::aid-da2>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.González-Tejera G, Canino G, Ramirez R, Chávez L, Shrout P, Bird H, et al. Examining minor and major depression in adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46:888–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sihvola E, Keski-Rahkonen A, Dick DM, Pulkkinen L, Rose R, Marttunen M, Kaprio J. Minor depression in adolescence; Phenomenology and clinical correlates. J Aff Disord. 2007;97:211–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams RL. A note on robust variance estimation for cluster-correlated data. Biometrics. 2000;56:645–646. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Munaò MR, Hitsman B, Rende R, Metcalfe C, Niaura R. Effects of progression to cigarette smoking on depressed mood in adolescents: evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Addiction. 2008;103:162–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The Health Consequences of smoking: Nicotine Addiction. Reports of Surgeon General. 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 40.DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Fletcher K, O'Loughlin J, Pbert L, Ockene JK, et al. Symptoms of tobacco dependence after brief intermittent use: the Development and Assessment of Nicotine Dependence in Youth-2 study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:704–10. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.7.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li TK, Volkow ND, Baler RD, Egli M. The biological bases of nicotine and alcohol co-addiction. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;16:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hudziak JJ, Althoff RR, Derks EM, Faraone SV, Boomsma DI. Prevalence and genetic architecture of Child Behavior Checklist-juvenile bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:562–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rose RJ, Dick DM, Viken RJ, Pulkkinen L, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Kaprio J. Genetic and environmental effects on conduct disorder, alcohol dependence symptoms and their covariation at age 14. Alcohol Clin. Exp Res. 2004;28:1541–8. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000141822.36776.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]