Abstract

Drosophila melanogaster is a leading genetic model system in nervous system development and disease research. Using the power of fly genetics in traumatic axonal injury research will significantly speed up the characterization of molecular processes that control axonal regeneration in the CNS. We developed a versatile and physiologically robust preparation for the long-term culture of the whole Drosophila brain. We use this method to develop a novel Drosophila model for CNS axonal injury and regeneration. We first show that, similar to mammalian CNS axons, injured adult wild-type fly CNS axons fail to regenerate, whereas adult-specific enhancement of protein kinase A activity increases the regenerative capacity of lesioned neurons. Combined, these observations suggest conservation of neuronal regeneration mechanisms after injury. We next exploit this model to explore pathways that induce robust regeneration and find that adult-specific activation of c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase signaling is sufficient for de novo CNS axonal regeneration injury, including the growth of new axons past the lesion site and into the normal target area.

Keywords: axon, Drosophila, explant, injury, regeneration, signal transduction

Introduction

Drosophila melanogaster is a leading genetic model organism in deciphering neuroscience problems such as memory formation or odor processing (Hallem and Carlson, 2004; Margulies et al., 2005), as well as modeling neurodegenerative diseases (Shulman et al., 2003; Bilen and Bonini, 2005). Recently, we and others developed methods to study traumatic brain injury in the fly CNS. Similar to their mammalian homologs, fly CNS neurons respond to injury by transient upregulation of the stress response c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase (JNK) pathway (Leyssen et al., 2005) and by Wallerian degeneration of their distal axonal stumps (Berdnik et al., 2006; Hoopfer et al., 2006; MacDonald et al., 2006).

The principle problem in CNS injury is the lack of efficient regeneration, which underlies long-term functional impairments. Molecular pathways that modulate axonal regeneration are therefore promising targets in the treatment of injuries. Mammalian studies suggest that stimulating intracellular cAMP signaling helps overcome growth inhibition of injured CNS axons (Cai et al., 2001; Neumann et al., 2002; Qiu et al., 2002).

Thus far, molecular insights into axonal regeneration have been gained from vertebrate models. However, an invertebrate model would lend itself to a faster and larger-scale genetic analysis. A model for PNS axon regeneration in Caenorhabditis elegans has been described (Yanik et al., 2004), but no paradigms are available yet to study regenerating CNS axons in worms or flies.

A significant impediment to developing a CNS axonal injury model in Drosophila is the inaccessibility of the adult fly CNS to reproducible, live, physical manipulation. To solve this problem, we optimized a method to explant, immobilize, and culture the Drosophila brain (Gibbs and Truman, 1998; Wang et al., 2003; Gu and O'Dowd, 2006), increasing its accessibility to various manipulations. We show that a subpopulation of neurons, the small lateral neurons ventral (sLNv), retain their morphological and functional properties for up to 1 week in culture. Using a microdissection technique, sLNv axons are reliably severed, and their response to injury is studied over several days. We find that the distal, severed, axon fragments degenerate in this preparation, as has been shown in vivo (Berdnik et al., 2006; Hoopfer et al., 2006; MacDonald et al., 2006). More importantly, as in mammals, very limited and weak regeneration of CNS axons occurs in the wild-type (wt) fly brain. Instead, injured adult CNS axons appear to form retraction bulbs with small local filopodial sprouts and in only a minority of cases is de novo growth observed. Also, as in mammalian systems, the regrowth capacity of injured LNv axons is significantly enhanced by genetic, adult-specific, increase in protein kinase A (PKA) activity in the LNv.

Our previous observations that injured fly brains upregulate JNK signaling (Leyssen et al., 2005) and the requirement of c-Jun for PNS regeneration (Raivich et al., 2004) lead us to hypothesize that JNK may play an important role in CNS axonal regeneration as well. We exploited the brain culture system to show that activation of JNK signaling strongly enhances CNS axonal regeneration after injury, including the growth of novel axons reentering the correct target area.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila lines and fly husbandry.

The PDF–Gal4 line was obtained from P. Taghert (Washington University Medical School, St. Louis, MO), UAS>CD2,y+>CD8–GFP was from G. Struhl (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, New York, NY), UAS–CD8–GFP, UAS–BskDN and UAS–hepCA was from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (University of Indiana, Bloomington, IN), UAS–PKAc5.9F, UAS–PKAcA75F, UAS–PKAmC* was from D. Kalderon (Columbia University, New York, NY), and tubPGAL80ts was from R. L. Davis (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX). The UAS–PKAc alleles were checked and verified by sequencing with the forward primer 5′AGGAGTTCGAGGACAAGTGG3′ and the reverse primer 3′CTAATGTTCCTGCTACTGCTA 5′. All flies were raised on standard fly food at room temperature, except when indicated. Flies of the genotype PDF–Gal4,UAS–CD8–GFP; UAS–CD8–GFP were created by recombination. To visualize single sLNv neurons, adult flies of the genotype hs–FLP; PDF–Gal4, UAS–LacZ/UAS>CD2,y+>CD8–GFP were heat shocked at 37°C for 45 min. They were left to recover at 28°C for at least 2 d to maximize green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression, dissected, and examined.

Culturing whole-brain explants on culture plate inserts.

Millicell low height culture plate inserts (catalog #PICMORG50; Millipore) were first coated with laminin (3.3 μg/ml; catalog #354232; BD Biosciences) and polylysine (33.3 μg/ml; catalog #354210; BD Biosciences). Adult female flies were collected within 4 d after eclosion and placed on ice. Before dissection, a fly was washed in 70% ethanol for a few seconds and placed in a sterile Petri dish containing ice-cold Schneider's Drosophila Medium (Invitrogen). The brains were quickly and carefully dissected out in this medium (<3 min/brain) and washed in ice-cold dissection medium. For larval brains, the same procedure was followed. The eye/antennal disc complex was left attached to the brains. After dissection and washing, up to 12 brains were placed in a drop of medium on the membrane of the culture plate insert. Culture medium (1.1 ml) was then added to the Petri dishes that were kept in a plastic box in a humidified incubator at 25°C. The culture medium was refreshed every 2 d. The culture medium used is modified from Gibbs and Truman, 1998) [10,000 U/ml penicillin, 10 mg/ml streptomycin, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 10 μg/ml insulin in Schneider's Drosophila Medium (Invitrogen)]. For the culture of larval brains, 1 μg/ml of Ecdysone was added. For additional details, see supplemental material (available at www.jneurosci.org).

Immunohistochemistry.

Freshly dissected brains of adult flies were processed for immunohistochemistry as described previously (Hassan et al., 2000). Primary antibodies were mouse anti-β-galactosidase (1:1000; Promega), rabbit anti-GFP (1:1000; Molecular Probes), rabbit anti-pigment dispersing factor (PDF) (1:40,000; P. Taghert), and rat anti-TIMELESS (TIM) (1:1000; A. Sehgal, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA). Cultured brains were first fixed by replacing the culture medium in the Petri dish with fixation solution (3.7% formaldehyde in PBS) for 30 min. Then 1 ml of fixation solution was carefully added on top of the filter for 2 h. Brains that detached from the membrane were excluded from additional analysis. Immunolabeling was performed as for freshly dissected samples.

Imaging and quantifications.

Living brains on the culture plate inserts were visualized with a Leica MZ FLIII stereomicroscope. Images were acquired on a Leica DC300F digital camera using Leica IM50 software. Overview images of brains were made at a total magnification of 100× and more detailed images at 200×. For confocal microscope image acquisition, a Leica TCS SL system was used. Confocal stacks at 0.5 μm distances were obtained, and projection images were generated with Leica confocal software. Snapshots of the LNv neurons were taken ∼6 h after injury from living brains in culture. Culture medium (550 μl) was put on top of the filter covering the brains in which a 63× water-dip lens was immersed to take the snapshots. Quantification of the newly grown sprouts was performed with NIH ImageJ and the Zeiss KS300 image analysis software. Student's t tests were used to calculate the significance of axonal length and distances covered by novel axons. χ2 tests were used to test significance for the percentage of brains showing regrowth and the percentage of axonal regrowth. p values >0.05 were considered nonsignificant; *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001. The contralateral, uninjured sLNv tract was used as a measure of the health of the preparation. Brains in which the uninjured sLNv tract showed signs of degeneration (supplemental Fig. S2, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) were excluded from analysis (∼10%). Representative images were used in the figures, which were prepared in Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe Systems).

Electrophysiological recordings of LNv in cultured brains.

For each electrophysiological recording experiment, all explants were maintained in 12 h light/dark cycle. Electrophysiological recordings were made using modification of previously described methods (Sheeba et al., 2008a,b) as originally developed by Gu and O'Dowd (2006). The composition of the external (bath) solution was as follows: 101 mm NaCl, 1 mm CaCl2, 4 mm MgCl2, 3 mm KCl, 5 mm glucose, 1.25 mm NaH2PO4, and 20.7 mm NaHCO3, 250 mOsm, pH 7.2. The composition of the standard internal solution was as follows: 102 mm K-gluconate, 0.085 mm CaCl2, 1.7 mm MgCl2, 17 mm NaCl, 0.94 mm EGTA, and 8.5 mm HEPES, 235 mOsm, pH 7.2. Dissected Drosophila adult fly brains (yw; pdf–Gal4; UAS–dORK–NC1–GFP/+) were cultured for 3 d and immobilized to prevent detachment by the perfusion flow. The insert was visualized using a BX51WI microscope (Olympus), and all patch-clamp recordings were made using this microscope under a continuous perfusion of the external solution, which was bubbled by a gas mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Microelectrodes at 10 MΩ resistance were fabricated from glass borosilicate capillaries using a PP-83 two-step gravity puller (Narishige). Pipettes were directed to neurons close to the explant brain surface using a MP-285 micromanipulator (Sutter Instruments). Cell attached seals of 2–3 GΩ were formed by gentle negative pressure. Whole-cell configurations were established by subsequent short negative pressure pulses. Current-clamp recordings were made using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices) connected to a Digidata 1322A acquisition system (Molecular Devices). Experiments were controlled by the pClamp 8.2 Clampex software (Molecular Devices). Whole-cell capacitance and series resistance compensations were applied in whole-cell configuration. Recordings were low-pass Bessel filtered at 5 kHz. Data analysis was performed using the pClamp 8.2 Clampfit software (Molecular Devices). Traces were low-pass filtered by the three-point boxcar method, electrical interference filtered at 60 Hz, leak current subtracted, and corrected for liquid junction potential as described by Sheeba et al. (2008a).

Injury of sLNv axonal tracts in cultured brains.

Under visual control at 100× using a Leica MZ FLIII stereomicroscope, the tip of an Eppendorf Microdissector (catalog #920 00 401-6) was placed on the axonal tract (see Fig. 3). The Piezo Power MicroDissection device was activated (frequency between 30 and 60 Hz, and amplitude 75–100% = 1.5 μm) that cut the axons. The injury was verified at 200× magnification. Axons were only injured on one side of the brain. For cohorts of injury that were compared at different time points, the brains of female sibling flies were dissected, cultured, and injured on the same day and fixed and stained at the appropriate time. Experiments were performed at least in duplicate. For the catalytic subunit of PKA (PKAc) and JNK injury experiments, flies were raised at 18°C, and <1-week-old flies were shifted to 28°C 2 d before culturing. Adult brains were dissected, cultured, injured, imaged with a water-dip lens, and kept at 25°C for 3 d and then processed and quantified as double blinds.

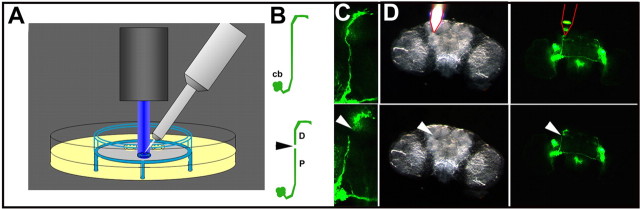

Figure 3.

Injury to the sLNv axonal bundle. A, Schematic showing the setup for the injury of sLNv axonal tracts in explanted brains on a culture plate insert. The axonal GFP pattern is observed using a stereomicroscope equipped with a GFP filter (blue ray). The microdissector (gray) tip is positioned on an axonal tract using a micromanipulator. The schematic is not drawn to scale. B, Schematic of sLNv before (top) and after (bottom) injury. cb, Cell body; D, distal part of the axon; P, proximal part of the axon; arrowhead, injury. C, Fluorescent signal in sLNv of the same brain before (top) and after (bottom) injury. Arrowhead indicates the disruption in GFP signal after axotomy. D, Bright-field (left) and GFP (right) images during (top) and after (bottom) the injury procedure. The microdissector tip is indicated by a red outline, and the injury site is indicated by an arrowhead. The genotype of the fly is PDF–Gal4, UAS–CD8–GFP; UAS–CD8–GFP. Images are made with a stereomicroscope at 200× (C) or 100× (D).

TARGET system.

The efficiency of TubPGAL80ts in our experimental setup was tested by raising flies of the genotype PDF–Gal4,UAS–CD8–GFP; Tubulin-Gal80ts/+ at 18°C and counting the number of sLNv cells that expressed GFP. Adult flies were then shifted to 28°C, and the number of sLNv cells expressing GFP were counted.

Results

The LNv as a model for CNS axonal injury in Drosophila

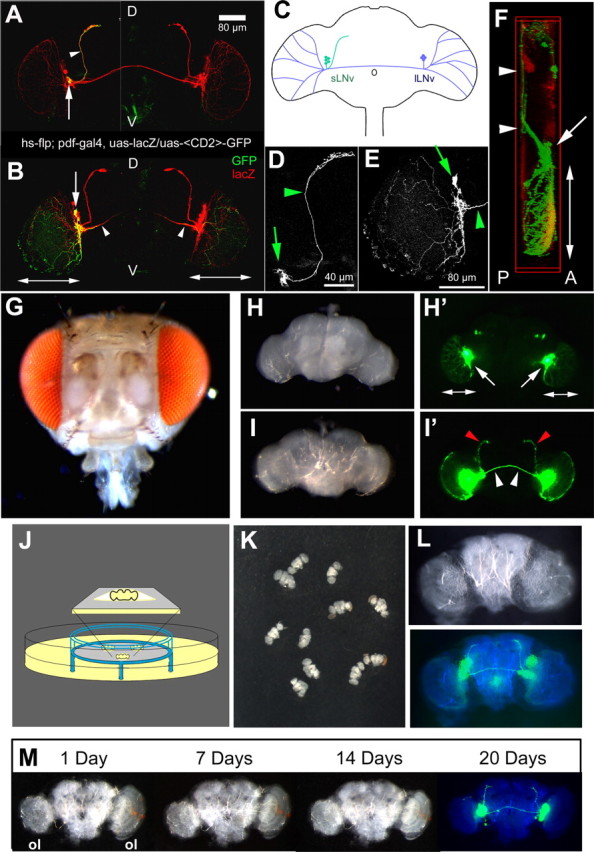

As a first step in the development of a model for CNS axonal tract injury in Drosophila, we identified a subpopulation of neurons in the adult brain that (1) forms stereotypic axonal tracts, (2) is easy to reach, i.e., superficial in the brain, and (3) can be genetically manipulated. The LNv fit all these requirements. These neurons are a component of the neuronal circuit that controls circadian rhythmicity of fly behaviors (Renn et al., 1999; Kaneko and Hall, 2000). There are two subpopulations of LNv (Fig. 1A–E): the sLNv composed of four to five neurons with small cell bodies (Fig. 1A,D, arrow) and dorsally projecting axons (Fig. 1A,D, arrowhead) and the large LNv (lLNv) with large cell bodies (Fig. 1B,E, arrow) and extensive ipsilateral optic lobe neurites (Fig. 1B,E; double pointed arrow) as well as a commissural axon (Fig. 1B, arrowheads) projecting toward the contralateral optic lobe. Importantly, the dorsally projecting axons of the sLNv lie superficially on the posterior side of the brain (Fig. 1F, arrowheads). This makes them easily accessible for visualization and physical manipulation in a brain that is dissected out of the head cuticle (Fig. 1, compare H, G) and oriented with the posterior side up (Fig. 1I,I′). Their cell bodies and the optic lobe innervation are found on the anterior side of the brain (Fig. 1F, arrow, double pointed arrows; H′ arrows, double pointed arrows). Transgene expression specifically in the LNv can be achieved using the galactosidase-4 (Gal4)/upstream activating sequence (UAS) system activated by the PDF–Gal4 driver line (Brand and Perrimon, 1993; Kaneko and Hall, 2000) and the LNv axons traced by expressing a membrane-bound fluorescent molecule CD8–GFP in the LNv. This allows easy visualization of the LNv axonal tracts in a living brain using a GFP filter on a stereomicroscope (Fig. 1H,I).

Figure 1.

Description of the LNv neurons and Drosophila brain explant culture on organotypic culture plate inserts. A, B, D, and E are projection images of 1 μm confocal stacks through adult Drosophila brains of the indicated genotype. A and B are compiled from separate images of the brain halves of the same brain. A, A single-cell sLNv FLP-out clone shows the cell body (arrow) and dorsally projecting axon (arrowhead) [both marked with GFP (green)] and LNv [marked by lacZ (red)]. Scale bar, 80 μm. B, A single-cell lLNv FLP-out clone shows the cell body (arrow), commissural axon (arrowhead), and optic lobe innervation (double-pointed arrows) [all marked with GFP (green)] and LNv [marked by lacZ (red)]. C, Schematic of an adult Drosophila brain indicating morphology and localization of the sLNv (green) and the lLNv (blue). D, Higher magnification of the GFP pattern in the single sLNv neuron shown in A. Scale bar, 40 μm. E, Higher magnification of the GFP pattern in the single lLNv neuron shown in B. Arrows indicate the cell bodies, and arrowheads indicate the axons. Scale bar, 80 μm. F, Lateral view of a three-dimensional reconstruction of an adult Drosophila brain. The sLNv dorsal projections and the commissural axons (white arrowheads) are on the posterior side of the brain (P). The LNv cell bodies (arrow) and the optic lobe innervation (double pointed arrow) lie anteriorly (A). Genotype of the flies is PDF–Gal4; UAS–CD8–GFP. G, Intact adult Drosophila head. H, I, Dissected adult Drosophila brain seen in bright field (H, I) or GFP filter (H′, I′) of a stereomicroscope (100× magnification). H, H′, Anterior view. Arrows point to the LNv cell bodies; double pointed arrows indicate optic lobe innervation by the lLNv. I, I′, Posterior view. Red arrowheads indicate the sLNv dorsal projections, and white arrowheads indicate the lLNv commissural axons. Genotype of the flies is PDF–Gal4, UAS–CD8–GFP; UAS–CD8–GFP. J, Schematic of the culture setup. Drosophila brains are positioned on the membrane (gray) of a low height organotypic culture plate insert (blue) that is placed in a Petri dish containing culture medium (yellow). The brain is separated from the air by a thin film of medium (inset). K, Overview image of several adult Drosophila brains positioned on the membrane of a culture plate insert. L, Higher-magnification image of one brain with bright field (top) or GFP filter (bottom; pseudocolored), showing the posterior LNv axonal tracts. M, Gross morphology of a cultured brain over the course of 20 d in culture remains intact. A GFP signal can still be detected after 20 d (ol, optic lobe). All images are taken with a stereomicroscope. The blue panels in L and M are a merge between a bright-field image pseudocolored in blue and the GFP signal in green. The genotype of the flies is PDF–Gal4, UAS–CD8–GFP; UAS–CD8–GFP.

A long-term, whole-brain explant culture

The LNv axons are, like the rest of the brain, separated from the environment by a hard cuticle (Fig. 1G). To overcome this barrier for visualization and micromanipulation of the axonal tracts, we attempted to remove the cuticle while keeping the brain alive and healthy. Explant cultures of Drosophila brains have already been successfully used to study axon remodeling during metamorphosis (Gibbs and Truman, 1998; Brown et al., 2006) and studying neuronal activity (Wang et al., 2003; Gu and O'Dowd, 2006). It is therefore in principle possible to keep Drosophila brains alive ex vivo. However, induction of reliable axonal injury and subsequent visualization require the explant preparation to be immobilized to make the precise micromanipulation of the brains possible.

The problem of immobilization as well as long-term survival of mammalian brain slice preparations has been solved by using culture plate inserts (Stoppini et al., 1991; Belenky et al., 1996; Collin et al., 1997; Weissman et al., 2004). These inserts consist of a porous membrane attached to a plastic ring and are placed in a Petri dish filled with medium (Fig. 1J). When positioned on the culture plate insert, the explant attaches to the membrane and is covered by a small film of medium (Fig. 1J). At this liquid–air interface, exchange of nutrients and air takes place, ensuring optimal conditions for the health of the explanted tissue. To obtain healthy, immobilized and easily accessible Drosophila brain preparations, we modified the culture media and conditions described for Drosophila tissues (Gibbs and Truman, 1998) in combination with the physical support of the culture plate insert described for mammalian brain slices.

The Drosophila brain is <300 μm thick (the thickness of mammalian brain slices). We therefore reasoned that Drosophila whole-brain explants could be used. Whole brains were dissected, thus leaving the connectivity pattern within the brain preserved. Figure 1J shows a schematic of the setup we used for these experiments (for details, see Materials and Methods). Brains from transgenic adult flies, expressing GFP under control of the PDF–Gal4 are carefully and rapidly dissected out of the head cuticle in ice-cold dissection medium. The dissected brains are transferred to the coated culture plate insert (Fig. 1K), and culture medium is added to the Petri dish. When examined with a fluorescence stereomicroscope, the axonal pattern of the posteriorly located sLNv dorsal projections and lLNv commissural axons is easily visualized (Fig. 1L). Explanting and culturing the brains using this new protocol thus simultaneously solves the accessibility, immobilization, and visualization problems inherent in whole animal preparations.

Using the medium described by Gibbs and Truman, 1998) (see Materials and Methods), a relatively high percentage (∼70%; n = 18) of the sLNv axon bundles innervating the dorsal brain remained intact (supplemental Fig. S1A, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). To further improve the health of the sLNv axons, we made a few changes to the composition of the medium (supplemental Fig. S1A, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). We found that a medium lacking antibiotics and the fungicide Amphotericin B increases the percentage of intact sLNv axons at day 4 (94%; n = 16). This high percentage of morphologically intact axons was maintained up to 6 d in culture (supplemental Fig. S2, Text 1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). We therefore used these conditions that enhanced the preservation of sLNv morphology for all additional experiments.

To examine the evolution of the gross morphology of cultured brains, we imaged brain explants every day over a period of 20 d (Fig. 1M) (n = 6). General brain morphology remains remarkably constant over this period of time. The only obvious change is an overall flattening of the preparation after a few days, a phenomenon well known to occur on culture plate inserts (Stoppini et al., 1991). Slight asymmetries in the contact face between the brain and the filter are also accentuated by this process [Fig. 1M, note the difference in optic lobe (ol) size]. Importantly, strong GFP expression in LNv cell bodies and axons is maintained (Fig. 1M, last panel), suggesting that the LNv neurons continue to express this protein for >20 d. On a global morphological level, the brains therefore support the culture conditions very well for at least 3 weeks.

Functional characteristics of the LNv are maintained in cultured brains

To test whether the LNv neurons also retain their functional properties in an explanted brain, we examined three characteristic features of the LNv. First, if the LNv retain their fate in culture, they should continue to express the LNv-specific PDF hormone (Renn et al., 1999). Indeed, a strong PDF immunosignal is observed in 7-d-old cultured brains in cell bodies and axonal bundles of the sLNv (Fig. 2A), suggesting that the hormone is still expressed and transported into axons. Second, if the circadian-rhythm-controlling LNv neurons function like in a living fly, they should retain their cyclic molecular clock properties in explants. This clock can be traced by immunostaining against PERIOD (PER) and TIM proteins (Hardin, 2005). In flies that have been entrained in 12 h light/dark cycles, high levels of these proteins are normally detected 22 h after lights on [Zeitgeber time 22 (ZT22)], which corresponds to the end of the night, whereas low levels are detected 10 h after lights on (ZT10), close to the end of daytime. To test whether this molecular oscillation is intact in explanted brains, we immunostained 3-d-old explants from entrained flies at two time points corresponding to the entrainment schedule, 10 and 22 h after lights on (ZT10 and ZT22). We find that the LNv express significantly higher levels of PER and TIM proteins at ZT22, as is the case in vivo (Fig. 2B,C). In addition, the relative change in the levels of TIM in explanted brains at the different time points is similar to those reported in vivo (Sehgal et al., 1994; Kaneko and Hall, 2000; Nitabach et al., 2002; Shafer et al., 2002). This means that the LNv not only retain their identity but also preserve their unique molecular characteristics in explants. In addition, FasII staining after 3 d in culture shows that other neuronal populations remain healthy in the explant (data not shown). Third, we tested whether neurons in the explant brains retain electrophysiological properties such as the firing of spontaneous action potentials. We attempted to record from large LNv as we have done previously in acute dissected brains (Sheeba et al., 2008a,b). However, for unknown technical reasons, we were not able to form high-quality gigaohm pipette seals on LNv. Although we cannot rule out the possibility that compromised health of LNv neurons in long-term cultures may have contributed to the difficulty of making recordings, we note that these neurons remain morphologically normal, and all LNv neurons tested appear to retain clock cycling. Thus, methodological reasons appear to be the more likely cause of the difficulties of making LNv recordings in long-term cultures.

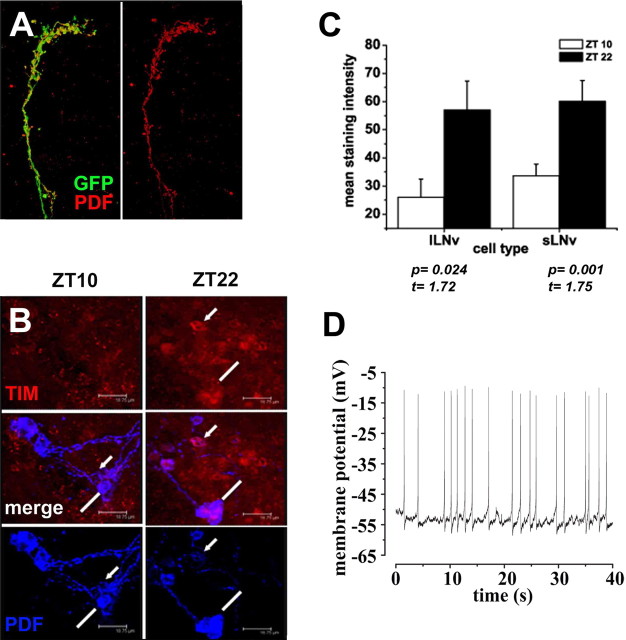

Figure 2.

The functional characteristics of the LNvs are maintained in cultured brains. Brains were maintained in a 12 h light/dark cycle. A, Immunostaining for PDF (red) shows the presence of PDH in the sLNv dorsal projection after 7 d in culture. B, Immunolabeling of small (arrow) and large (line) LNv in a 3-d-old cultured brain. Time points ZT10 and ZT22 correspond to 10 and 22 h after lights on. A significantly reduced level of TIM (red) is seen in the brains after 10 h of light (ZT10), whereas cells show higher levels and nuclear localization during the late hours of the night (ZT22) in both the large and small LNv. C, Quantification of TIM levels in brain explants (t test for lLNv ZT10 vs ZT22, t = 1.72, p = 0.024; t test for sLNv ZT10 vs ZT22, t = 1.75, p = 0.001, n = 5 brains for each comparison). The genotype of the fly in A is PDF–Gal4, UAS–CD8–GFP; UAS–CD8–GFP and in B is yw; pdf–Gal4; dORK–NC1/+. D, Spontaneous action potentials of an unidentified surface neuron in a 3-d-old cultured brain. Large-amplitude spontaneously firing action potentials and afterhyperpolarizations are observed in whole-cell patch current-clamp recordings.

To investigate the general health of the cultured brain, unidentified neurons close to the explant brain surface were probed using whole-cell patch-clamp recordings (Gu and O'Dowd, 2006; Sheeba et al., 2008a,b). The cells were accessible to the patch pipette in brains oriented with the anterior side up. Compared with the relative ease of making recordings from acutely dissected whole brains, it was difficult to establish a cell-attached configuration and to break into the membrane after establishing the cell-attached configuration. Despite this technical difficulty, whole-cell patch-clamp recordings in current-clamp mode were made successfully from two different unidentified neurons in 3-d-old cultured brains. Both cells show healthy spontaneous action potential firing. One of the two recorded neurons exhibited a resting membrane potential of −53 mV and spontaneous firing frequency of 0.5/s (Fig. 2D), and the other neuron exhibited a resting membrane potential of −45 mV and spontaneous firing frequency of 0.9/s. These electrophysiological values are similar to those obtained from identified LNv neurons in freshly dissected whole-brain preparations (Sheeba et al., 2008a). A third unidentified neuron recorded from a 3-d-old explant brain was initially silent but could be induced to fire action potentials by depolarizing current injection (data not shown).

Lack of efficient spontaneous regeneration in the Drosophila CNS

Having made the superficial sLNv axonal tracts accessible to micromanipulation, we designed a simple, inexpensive, and accurate setup to sever them using a Piezo Power MicroDissection device (Fig. 3A) (for details, see supplemental text 1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). Briefly, the sharp tip of the microdissector is positioned on the sLNv axonal tract using a micromanipulator. The device is activated, causing an oscillation of the tip and thereby severing of the axons (Fig. 3B–D, arrowhead). The GFP-labeled axons are directly visualized throughout the procedure (Fig. 3C,D), and successful injury was readily observed. To further confirm the success of the injury procedure, we examined brains shortly after making the lesion using confocal microscopy. We find that, in 100% of the cases (n = 18), the dorsally projecting axonal bundle was fully severed.

We also noted that, immediately after the injury, the severed axons retracted away from the lesion site, a process that has been observed previously in the mouse spinal cord (Kerschensteiner et al., 2005). On average, the stable gap size from the retracted site of injury until the beginning of the distal stump was 36.14 μm with 67% of the samples showing a gap size of ∼20 ± 22.35 μm or more (mean ± SD; n = 18).

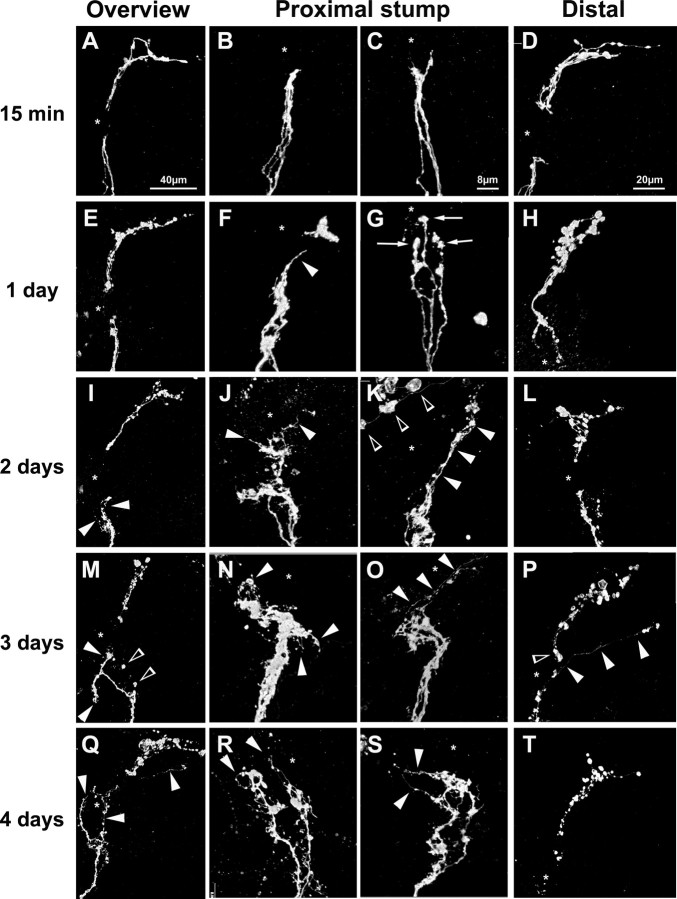

A key difference between injury to PNS versus CNS axons in mammals is that PNS axons regenerate spontaneously, whereas CNS axons essentially fail to regenerate. To test whether, similar to mammals, the fly CNS fails to spontaneously regenerate after injury, we used the explant system to lesion sLNv axonal tracts in cultured brains and examined their morphology at different times after injury. When injured brains are examined within 15 min after the lesion, the proximal axonal stump is uniform in width (Fig. 4A–C), and the distal, unconnected axonal ends appear smooth and continuous (Fig. 4D). One day later (Fig. 4E–H), the proximal axons develop bulbar enlargements at their tips (Fig. 4G, arrows), and on these bulbs what appears like filopodial sprouts are formed in 59% of brains (Fig. 4F, arrowhead) (n = 17). The distal axonal ends appear more vesicular and fragmented (Fig. 4H). Over the next 4 d, an increase in proximal sprouting is observed. In most cases, the extensive axonal sprouts either remain stalled (Fig. 4J,N,R) [57% (8 of 14) on day 2; 47% (8 of 17) on day 3; 34% (5 of 15) on day 4] or grow laterally for short distances (Fig. 4M,S; filled arrowheads) [36% (5 of 14) on day 2; 35% (6 of 17) on day 3; 40% (6 of 15) on day 4]. In no case did these sprouts reach or traverse the lesion site. LNv cell body counts show that all these neurons survive (data not shown). These experiments thus provide good evidence that the proximal severed axonal stump is extensively remodeled over a period of several days, but the large majority of axons completely fail to regrow after injury. The distal axonal ends undergo progressive fragmentation and degeneration (Fig. 4D,H,L,P,T). Together, these findings suggest that, as in mammals, injured wild-type adult Drosophila CNS axons do not regenerate.

Figure 4.

Response of sLNv axons to injury. A–D, At 15 min after the lesion, all axons are clearly severed (B, C, asterisk). The distal axon ends appear uniform and continuous (D). E–H, At 1 d after the lesion, the proximal stumps form bulbous ends (G, arrows) from which axonal spikes can grow (F, arrowhead). The distal axon ends appear more vesicular (H). I–L, At 2 d after the lesion, axonal sprouts are formed (I–K, filled arrowheads). The distal axonal ends appear vesicular (L). M–P, At 3 d after the lesion, axonal sprouts are still present on the proximal stump. In some cases, axons grow away from the target area (M, filled arrowheads), and degenerated fragments of axons can be observed (open arrowheads). In other cases, axons remain stalled before the lesion site (N). The distal axonal fragments appear vesicular (P, open arrowhead). Q–T, At 4 d after the lesion, axonal sprouts of different lengths (filled arrowheads) grow laterally (Q, S) or toward the injury site (Q, filled arrowheads). The distal axons are fragmented (T). * indicates lesion site. The genotype of the flies is PDF–Gal4, UAS–CD8–GFP; UAS–CD8–GFP. All panels are projections of confocal 0.5 μm stacks. Scale bars: overview pictures, 40 μm; proximal stumps, 8 μm; distal stubs, 20 μm.

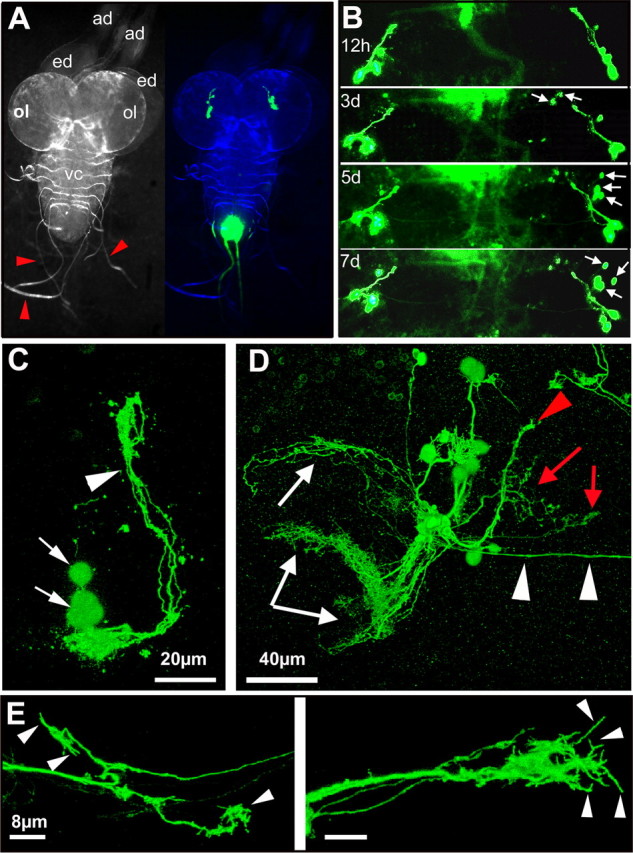

Intact axonal outgrowth in larval brain explants

One caveat is that the failure to efficiently regenerate axons may be attributable to culture conditions rather than the intrinsic characteristics of the adult fly brain and its neurons. We therefore tested whether developing axons can grow in an explanted brain under our culture conditions, taking advantage of the extensive axonal reorganization that takes place during metamorphosis from the larval to an adult CNS. Figure 5A shows a Drosophila CNS very shortly before pupariation. The sLNv neurons are present and have already formed their dorsal projections, but the lLNv are not visible at this stage. Larval brains were imaged each day over a period of 7 d. We observe that new LNv cell bodies start to express GFP (Fig. 5B, arrows), suggesting that lLNv are born and acquire their correct PDF-positive identity in the explant. Next, confocal imaging studies of brains at 24 h versus 5 d in culture were performed. At 24 h in culture, only the four sLNv cell bodies (Fig. 5C, arrows) and their dorsal projections (Fig. 5C, arrowhead) are apparent. However, after 5 d in culture, we find axons projecting toward the brain center and the optic lobes in 100% of the cases (n = 13) (Fig. 5D, white arrows and arrowheads). Finally, to visualize the morphology of the growth cones on newly formed axons in brain explants, we imaged the tips of the axonal bundles that project toward the contralateral side of the brain at high resolution. We find that these axons form extensive growth cones with a large number of small sprouts (Fig. 5E, arrowheads). When growing larval axons were injured, outgrowth was still observed after 5 d in culture (data not shown). However, because uninjured axons also grow during this period, it is very difficult to ascertain whether the growth observed is regenerative or developmental. Nonetheless, these data clearly show that the culture conditions used are not per se growth inhibitory.

Figure 5.

Axonal outgrowth and growth cone formation in explanted larval brains. A, Morphology of the third-instar larval CNS (left) (ad, antennal disc; ed, eye disc; ol, future optic lobe; vc, ventral cord; red arrows, nerves). The GFP signal in the brain lobes (right) corresponds to the sLNv neurons. B, Morphological changes in the GFP pattern over time include the appearance of new GFP-positive cell bodies (arrows). C, Detail of the GFP expression pattern after 24 h in culture showing the sLNv cell bodies (arrows) and the dorsally projecting axons. Scale bar, 20 μm. D, Detail of the GFP expression pattern after 5 d in culture showing dorsally projecting axons of the sLNv (red arrowhead). New axonal tracts project toward the contralateral brain half (white arrowheads), the future optic lobes (white arrows), and the central brain (red arrows). Scale bar, 40 μm. E, Detail of the growth cones of the commissure. Note the presence of filopodia at the axonal end (arrowheads). Scale bar, 8 μm. A and B are stereomicroscope images. The blue panel in A is a merge between a bright-field image pseudocolored in blue and the GFP signal in green. C–E are projection images of 0.5 μm confocal stacks. The genotype of the flies is PDF–Gal4, UAS–CD8–GFP; UAS–CD8–GFP.

Together, these results indicate that larval LNv axons can grow in explanted brains and that this growth correlates with the formation of elaborate growth cones. This morphology contrasts with the dystrophic growth cones of injured adult brain axons (Fig. 4), indicating that, rather than being inhibited by the culture conditions per se, injured Drosophila adult brain neurons, like their mammalian counterparts, essentially fail to regenerate.

The role of PKAc in stimulating growth after injury is conserved

Mammalian CNS axon injury studies show that elevating cAMP levels can enhance regrowth after injury (Neumann et al., 2002; Qiu et al., 2002). These studies also suggest that a major effector of the cAMP signaling pathway for regrowth is PKA because cAMP-induced regrowth can be blocked by PKA inhibitors (Qiu et al., 2002). Together, these studies imply a crucial role for PKA in the regenerative capacity of injured CNS neurons. If axonal injury in the explanted Drosophila brain is to serve as a genetic paradigm for the study of traumatic axonal injuries in the CNS, modulation of the regenerative response, such as switching the damaged neurons to a stronger growth state, should be possible. To test whether PKAc activity could modulate the regenerative capacity of cut CNS axons in our injury paradigm, we used the binary Gal4–UAS system to overexpress different UAS–PKAc alleles specifically in the LNv neurons. Transgenes encoding PKAc5.9, a wild-type, fully active, Flag-tagged, PKAc allele [henceforth, PKAcwt (Kiger et al., 1999)], and PKAcA75, a mutant allele with at least 1000-fold less catalytic activity (Kiger and O'Shea, 2001) than PKAcwt, were used to genetically manipulate PKAc activity. Both transgenes were expressed in the LNv together with CD8–GFP using the pdf–Gal4 driver. To overcome the developmental effects of PKAc overexpression and allow delivery of PKAc activity specifically in adult neurons before inducing the injury onward, we turned to the TARGET system (McGuire et al., 2003). The TARGET system uses a ubiquitously expressed, temperature-sensitive (ts) Gal80 (tubP–GAL80ts) to repress Gal4 activity at the permissive temperature. Using this approach, we primarily suppressed developmental expression and thus developmental effects of increased PKAc activity (data not shown).

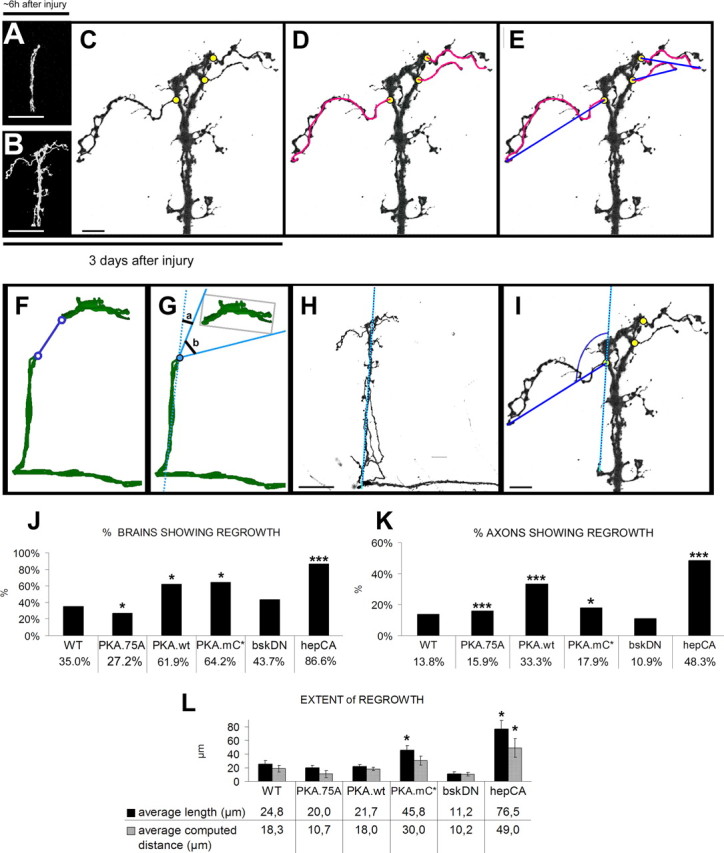

To assess the capacity of PKA to induce axonal regeneration, we imaged each injured brain ∼6 h (Fig. 6A) and 3 d (Fig. 6B) after injury. By comparing the images from the same axon stump 6 h and 3 d after the injury, the novel axons were identified (Fig. 6C, yellow circles; D, pink lines) and their response was quantified based on the following criteria (for additional details on the definition of these criteria, see supplemental Text 2, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). First, we calculated the penetrance of the regenerative response at the level of individual brains, by determining the percentage of brains showing regrowth after injury. Specifically, we counted the number of brains sprouting at least one new axon after injury. Second, we calculated the penetrance of the regenerative response at the level of individual axons. Specifically, we counted the number of newly generated axons and divided this by the total number of injured axons, thus determining the propensity of single axons to regenerate. Third, we calculated the extent of axonal regrowth, by measuring the length of each newly grown axon extension by freehand tracing (Fig. 6D, pink lines). In addition, we computed the direct distance these new axons cover as a straight line from the site of injury to the tip of the new axonal sprout (Fig. 6E, blue lines) to test whether regenerated axons can bridge the lesion gap and grow toward the original target area. In wild-type brains, this gap was measured to be 36 μm. Using these three criteria, we are able to objectively quantify the regenerative response at the level of individual brains as well as at the level of single axons.

Figure 6.

Quantification of novel axonal outgrowth after injury. A, Injured axons were imaged ∼6 h after injury to verify the injury and capture the morphology of the cut proximal stump. Scale bar, 40 μm. B, The same brain was fixed and processed for imaging 3 d after injury, and the proximal stump was imaged again at the same magnification as A. Scale bar, 40 μm. C, By comparing the images from the same axon stump ∼6 h and 3 d after the injury, the novel axons were identified, and their point of origin from the cut axonal stump was determined (yellow circles). Based on this determination of novel growth, the percentage of brains showing regrowth was calculated by counting the number of brains that sprouted at least one novel axon from the site of injury. Scale bar, 8 μm. D, To measure the extent of regrowth, the length of a novel axon is traced by free-hand tracing (pink lines), as a criterion for how long the novel axons can grow. E, In addition to the length of the new axons, the distance these novel axons can cover in a straight line is also measured (blue line), as a criterion to measure how far the novel axons reach. F, The size of the gap induced by axonal lesion was measured in micrometers by drawing a line connecting the proximal stump and closest distal stub (n = 18). G, Measurement of the direction of normal target area to a reference line running with the axonal shaft. The results of F and G were calculated as averages (n = 18). H, I, The direction of the novel axons was measured by first drawing a reference line running parallel with the axonal shaft (H) and then measuring the angle of the novel axon to the reference line (I). Scale bars: H, 40 μm; I, 8 μm. J, Graph showing the percentage of brains regrowing at least one axon with different genetic manipulations. The value is calculated as the number of brains regrowing at least one novel axon after injury as a percentage of the total number of brains. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001. K, Graph showing the percentage of axonal regrowth. This is calculated as the number of newly grown axons on the total number of cut axons. To calculate the total number of cut axons, the number of examined brains was multiplied by four (the average number of sLNv in one brain hemisphere). *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001. L, A comparative graph showing the extent of regrowth under different genetic manipulations. The black bars represent the average length of the new axons, and the gray bars represent the average computed distance of the new axons. For statistical analysis, values of the different genotypes were compared with the values for WT brains. *p < 0.05.

At day 3 after injury, the percentage of brains showing regrowth after injury in control samples is 35% (n = 20) (Fig. 6J). Expression of the catalytically mutant version PKAA75 significantly decreases the percentage of brains sprouting new axons from the site of injury to 27.2% (n = 11; p = 0.0402). Conversely, significantly more brains expressing PKAwt sprouted new axons from the injury site (61.9%; n = 21; p = 0.0078) (Figs. 6J, 7A–C). The regenerated axons transport PDF, showing they are functionally connected to the original bundle (supplemental Fig. S3A–C, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). These results suggest that PKA activity can increase the percentage of brains showing regrowth after injury.

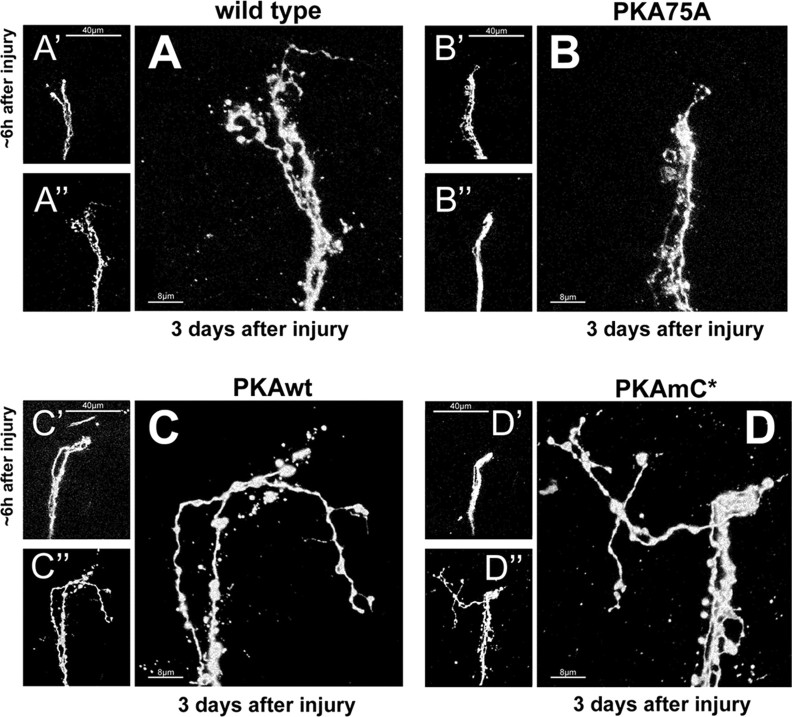

Figure 7.

Injury experiments at 18–28°C of PKA alleles with tubPGAL80ts. A, A′, A″, Injury on control brain. A′, Snapshot taken from a control brain ∼6 h after injury. A″, The same brain was fixed at day 3 and imaged again. A, A high magnification of the proximal stump. Scale bars: A′, A″, 40 μm; A, 8 μm. B, B′, B″, Overexpression of PKAc.A75. B′, Snapshot ∼6 h after injury. B″, The same brain imaged at day 3. B, High magnification of proximal stump. Scale bars: B′, B″, 40 μm; B, 8 μm. C, C′, C″, Overexpression of PKAcwt has a strong positive effect on the penetrance of regrowth but not the extent of axonal growth. C′, Snapshot of a brain ∼6 h after injury. C″, Snapshot of the same brain 3 d after injury. C″, High magnification of proximal stump. Scale bars: C′, C″, 40 μm; C, 8 μm. D, D′, D″, Overexpression of PKAmC* induces significantly more regrowth. Also, the length of the newly grown axons is significantly bigger but not the average distance they bridge. D′, Snapshot of a brain ∼6 h after injury. D″, Snapshot of the same brain 3 d after injury. D, High magnification of proximal stump. Scale bars: D′, D″, 40 μm; D, 8 μm. Genotypes are as follows: A, A′, A″ is PDF–Gal4, UAS–CD8–GFP; tubPGAL80ts/+; B, B′, B″ is PDF–Gal4, UAS–CD8–GFP; tubPGAL80ts/UAS–PKAc.A75; C, C′, C″ is PDF–Gal4, UAS–CD8–GFP; tubPGAL80ts/+; UAS–PKAc5.9F/+; and D, D′, D″ is PDF–Gal4, UAS–CD8–GFP; tubPGAL80ts/UAS–PKAmC*.

Next we asked whether, in addition to increasing the percentage of brains showing regrowth after injury, PKA has also an effect on the percentage of axons showing regrowth as well as on the length and the distance the new axons cover. In control brains, the percentage of axonal regrowth is 13.7% (11 of 80), the length of a newly extended axon is 24.8 μm, and the average distance in a straight line a new axon can bridge is 18.3 μm (Fig. 6K,L). Expression of PKAwt significantly increases the percentage of axonal regrowth [33.3% (28 of 84); p ≤ 0.001), but not the average length of the new axons (21.7 μm; n = 21; p = 0.62) or the distance they are able to cover (18 μm; n = 21; p = 0.96) (Fig. 6K,L).

In conclusion, PKAcwt enhances both the percentage of brains showing regrowth as well as the percentage of regenerating axons, but it did not have an effect on the extent of regrowth in terms of the length and distance the new sprouts cover. Because the PKAcwt allele is subject to negative regulation by the endogenous regulatory subunit of PKA, a constitutively active PKAc allele, PKAmC* (Li et al., 1995), was also tested in the injury model. As expected, PKAmC* also significantly increased both the percentage of brains and axons showing regrowth after injury [64.2%, n = 14, p = 0.019 and 17.8% (10 of 56), p = 0.0053, respectively] (Fig. 6J,K). Furthermore, LNv expressing activated PKAc did grow significantly longer axons than controls (45.8 μm; p = 0.023) (Fig. 6L). Interestingly, the average distance these new axons had moved from the point of injury was not significantly different from wild type (30 μm; p = 0.17) (Figs. 6L, 7D).

Together, these data suggest that, at a certain threshold, PKAc activity can enhance the potential of damaged axons to regrow. Constitutive activation of PKAc can increase the length of newly generated axons but not the distance they cover. These results show that our injury model is amenable to modifying the regenerative response of damaged neurons. In addition, these results are in agreement with the observations in mammalian CNS regeneration studies and strongly suggest conservation of injury, regrowth, and regeneration processes. Importantly, despite the robust growth induced by constitutively active PKAmC*, the average distance covered by these axons (30 μm) is still short of bridging the gap (36 μm) between the lesion site and the normal target area.

Activated JNK signaling induces regeneration back into the original target area

Our analyses so far suggest that the brain explant system is a robust, quantifiable, and genetically amenable system for the study of conserved axonal injury and regeneration processes. The data also clearly highlight the need for the discovery of pathways that might induce better regeneration. We hypothesized that a good candidate may be the JNK pathway. First, JNK is a general stress response pathway (Leppa and Bohmann, 1999). Second, we have shown that JNK signaling is necessary and sufficient for axonal extension in the fly CNS (Srahna et al., 2006) and that it is transiently induced by brain injury in Drosophila (Leyssen et al., 2005). Third, c-Jun is necessary for spontaneous regeneration in the mouse PNS (Raivich et al., 2004). Despite these hints in flies and mammals, a role for JNK activity in CNS regeneration has not been investigated.

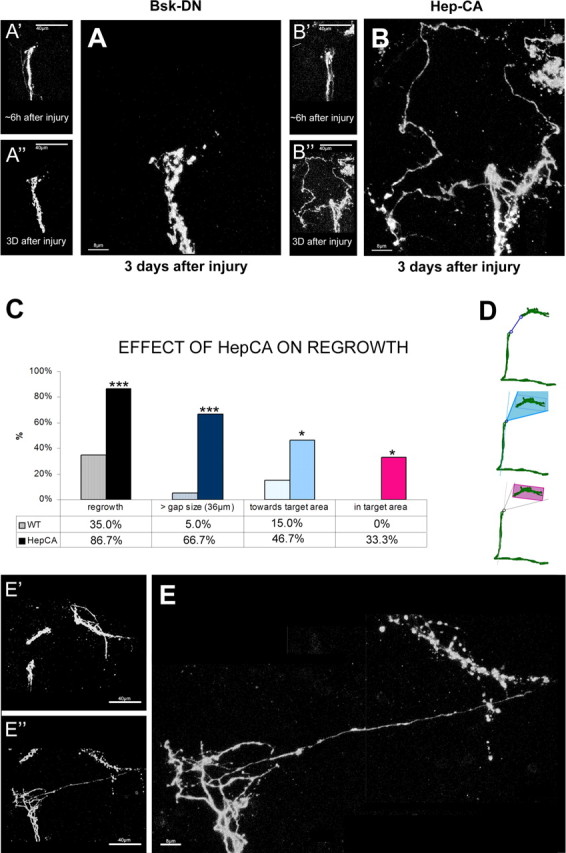

To test a role for JNK in CNS axonal regeneration, we inactivated JNK signaling solely in the adult LNv neurons by overexpressing a dominant-negative allele of the Drosophila JNK Basket (BskDN) (Boutros et al., 1998; Reed et al., 2001; Srahna et al., 2006) and examined axonal regeneration using the three main criteria described above. Adult-specific inhibition of JNK signaling in injured LNv does not significantly alter the percentage of brains or single axons showing regrowth [43.7%, n = 16, p = 0.26 and 10.9% (7 of 64), p = 0.059, respectively] (Figs. 6J,K, 8A). In contrast, JNK inhibition shows a strong tendency to reduce the length of the newly extended axons from 24.8 μm in control neurons to 11.2 μm (p = 0.053). As a result, the average gap bridged by these axons is reduced from 18.3 to 10.2 μm (p = 0.18) (Fig. 6L). These data suggest that JNK signaling is not necessary for injured neurons to initiate axonal regrowth but may rather regulate the extent of this regrowth.

Figure 8.

Injury experiments at 18–28°C injury experiments on JNK signaling with tubPGAL80ts. A, A′, A″, Injury on brains expressing a BskDN allele in the LNv: A′, A″, a snapshot of the brain ∼6 h after injury and 3 d after injury; A, a higher magnification of the injured proximal stump 3 d after injury. Scale bars: A′, A″, 40 μm; A, 8 μm. B, B′, B″, C′, C″, Injury on brains expressing a HepCA allele. B′, C′ and B″, C″, Snapshot ∼6 h and 3 d after injury, respectively. B, Higher magnification showing massive growth. Scale bars: B′, B″, 40 μm; B, 8 μm. C, D, Quantifying the extent of growth observed in brains expressing HepCA compared with control brains. C, Percentage of brains regrowing at least one novel axon longer than 36 μm (dark blue bar), the percentage of brains growing at least one novel axon toward the target area (light blue bar), and the percentage of brains growing at least one novel axon into the target area (pink bar). D, Schematic drawing of the different quantifications described above in C. All values are significant (*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001). E, E′, E″, Example of HepCA-expressing neurons showing regrowth back into the target area. Scale bars: E′, E″, 40 μm; E, 8 μm. Genotypes are as follows: A, A′, A″ is PDF–Gal4, UAS–CD8–GFP; tubPGAL80ts/BskDN; B, B′, B″, E, E′, E″ is PDF–Gal4, UAS–CD8–GFP; tubPGAL80ts/+; UAS–hepCA.

Next, we tested whether activation of JNK signaling might positively influence axonal regeneration after injury. To this end, we expressed a constitutively active form of the Drosophila JNKK Hemipterous (HepCA) (Adachi-Yamada et al., 1999) specifically in injured adult LNv. As in previous experiments, we imaged the severed LNv axons at ∼6 h and 3 d after injury. We observe that JNK activation significantly enhances all aspects of axonal regrowth after injury. First, the percentage of brains showing regrowth expressing HepCA was 86.6% (n = 15; p = 0.0001) compared with 35% of control brains (Fig. 6J). Second, the percentage of axonal regrowth increased 3.5-fold to 48.3% compared with control brains (13.7%) (Fig. 6K). Third, the average length of the new axons is increased approximately threefold to 76.7 μm (p = 0.001) (Fig. 6L). In addition, these new axons cover an average distance of 49 μm (p = 0.01), almost 2.5-fold the length observed in control brains and well beyond the ∼36 μm necessary to bridge the injury gap (Figs. 6L, 8B). Although the average distance covered by novel axons in control brains is only 18.3 μm (almost half of the average gap size induced by the lesion), occasionally (1 of 20) there is a brain that can grow an axon able to cover a distance longer than 36 μm. In contrast, 66.6% (11 of 15; p < 0.001) of all HepCA-overexpressing brains can grow at least one axon able to bridge the gap of 36 μm (Fig. 8C,D, top panel).

True axonal regeneration is defined by the direct regrowth of the cut axons themselves into the denervated target area (Adachi-Yamada et al., 1999; Harel and Strittmatter, 2006; Yiu and He, 2006; Raivich and Makwana, 2007). In our samples, the target area is clearly demarcated by the remnants of the distal stump (Fig. 6G, gray box). Therefore, the number of axons growing toward and into the target area can be precisely quantified (Fig. 6G–I) (supplemental Text 2, Figs. S3D,E, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). We find that 46.6% (7 of 15) of HepCA-expressing brains grow at least one axon toward the target area (Fig. 8B–D). Because activation of JNK signaling results in axons that are of sufficient length to potentially bridge the injury gap, we finally quantified the number of brains in which novel axons reenter the denervated target area (Fig. 8D, bottom panel, shaded pink). We do not find any examples of this in genetic controls. In contrast, one in three of all HepCA-expressing brains show novel axons reentering the target area (5 of 15; p = 0.02) (Fig. 8C–E).

Discussion

Why a Drosophila model for traumatic axonal injury?

Drosophila melanogaster is a leading genetic model organism not only in basic neuroscience but also in biomedical research. Using the power of this genetic model organism, difficult problems such as the molecular mechanisms behind human neurodegenerative diseases are being successfully addressed (Shulman et al., 2003; Bier, 2005; Bilen and Bonini, 2005). These advances have depended primarily on the development of good Drosophila models for these human diseases (Feany and Bender, 2000). Very recently, the first models for axonal severing in the CNS of the fly have been developed and have unveiled a marked conservation in the molecular mechanisms underlying neuronal responses to injury in flies and mammals (Leyssen and Hassan, 2007). Although these valuable paradigms hold promise to significantly enhance our insights into axonal degeneration in the future, they do not allow the evaluation of axonal regeneration. Increased insight into the process of regeneration is crucial from a therapeutic point of view that aims at stimulating axons to reconnect to their postsynaptic target. In this work, we describe a protocol that allows, in addition to a versatile series of manipulations, the precise and reliable severing of sLNv axons in explanted adult Drosophila brains. This technique provides, for the first time, the opportunity to study axonal regeneration in the Drosophila CNS and use genetic screens to identify factors that promote axonal regeneration.

The responses of injured axons in the Drosophila brain

The regenerative responses of injured axons in Drosophila brain explants show remarkable similarities to those seen in mammals. First, the distal, severed ends of the axons became fragmented in a manner that is reminiscent of Wallerian degeneration in mammals, as was described also in living Drosophila (Hoopfer et al., 2006; MacDonald et al., 2006). In both cases, unconnected axons were rapidly split into small vesicles, which then disappeared. A major advantage of the explant model is that it also allows the study of the proximal, injured axon. One day after injury, the proximal axonal stump forms a bulbar structure that shows morphological similarities to the dystrophic retraction bulbs seen in injured mammalian CNS axons (Silver and Miller, 2004). This structure is extensively remodeled and develops small, and occasionally longer, thin axonal sprouts. Similar morphological changes have been described recently in severed, GFP-marked axons of the mouse spinal cord (Kerschensteiner et al., 2005).

The lack of efficient regeneration of injured Drosophila axons in brain explants is not attributable to the experimental setup. First, sLNv neurons in the preparation appear healthy both morphologically and functionally. Second, axons in explanted larval brains do form elaborate growth cones and grow large distances over the course of a few days. Third, the proximal axonal stumps are clearly dynamic and capable of sending out axonal sprouts. We therefore suggest that the lack of efficient sLNv axonal regeneration is an intrinsic feature of the adult fly brain. Indeed, we show that the adult-specific, cell-autonomous manipulation of the catalytic activity of PKA can stimulate a generally dormant regrowth capacity. A significantly larger proportion of lesioned brains become capable of extending new axons at the cut tip. This is very similar to the mammalian cAMP-based enhancement of regrowth (Cai et al., 2001; Neumann et al., 2002; Qiu et al., 2002). In both cases, regrowth is achieved by increasing PKA catalytic activity, either reducing the negative regulation of PKAc through adding of cAMP in the mammalian studies or overexpressing a catalytic mutant version of PKA that is free from endogenous inhibition. In summary, the data presented herein support the concept that the fly CNS is closer in its response to injury to the mammalian CNS than the mammalian PNS. The mammalian PNS regenerates spontaneously, whereas, in contrast, both the fly and mammalian CNS fail to regenerate except when additional signals are activated. In the case of PKA, the same signal enhances regeneration in both models. This, in addition to several other details, such as the anatomy of the retracting injured axons and the appearance of a lesion gap, support the conservation of key injury response mechanisms between the two CNS systems.

JNK signaling regulates axonal regeneration

In mammalian models for CNS regeneration, several modes of neuronal repair are proposed. These neuronal recoveries can be accomplished directly by either the transected axons itself or by sprouts from unlesioned axons in the neighborhood into the denervated target area (Raivich and Makwana, 2007). However, what is defined as true axonal regeneration is the reentry of the cut axons themselves onto the denervated target area. Axonal regeneration encompasses several types of neuronal responses that can be grossly divided into the following steps: (1) regrowth of the cut axons, (2) guidance of the newly growing axons toward the normal area of innervation, and finally (3) reinnervation of the denervated target area.

Despite the promising results of PKA manipulation, a constitutively active form of PKA is not sufficient to produce axons that can extend into the original target area. We therefore tested the hypothesis that JNK signaling might support better regeneration. Our data suggest that JNK is likely to be a key pathway in CNS axonal regeneration after injury. Inhibiting JNK activity results in a high tendency to inhibit the length of the newly grown axons compared with control brains, whereas its constitutive activation results in a massive increase in the penetrance and extent of regeneration, with one-third of all brains showing regenerated axons reentering the target area. It is surprising that activation of only a single pathway is sufficient to enhance the three major anatomical criteria of regeneration. This may be explained by at least two alternative models. It may be that LNv neurons, and presumably other CNS neurons as well, retain their proper guidance and targeting signals well into adult life, and as such genetic manipulations stimulating the frequent growth of lengthy axons can result in axons reaching the correct target area. Alternatively, JNK activation may act as a reprogramming signal allowing neurons to reactivate their specific developmental pathways. Although we do not exclude a role for JNK in axonal navigation, our previous work (Leyssen et al., 2005; Srahna et al., 2006) shows that JNK can stimulate different cell types to grow longer axons, without influencing their guidance properties. In this context, it may seem surprising that the induction of JNK signaling observed during axonal injury (Leyssen et al., 2005) is not sufficient to induce regeneration. However, it is in fact likely that the transient upregulation of JNK does play a role in stimulating growth after injury because, when injured axons express dominant-negative forms of JNK, they show a strongly reduced regrowth tendency compared with wild-type brains (Fig. 6), although this reduction remained just below statistical significance. The reason why activated JNK signaling has such a dramatic influence on regeneration is twofold. First, an activated form of the protein is no longer subject to endogenous negative regulation. Second, this form is expressed as a UAS transgene, which means that its expression is permanent and not transient, in contrast to what we observe under wild-type injury conditions.

Future applications of the injury paradigm and of Drosophila whole-brain culture

Because the system described here is amenable to cell-type-specific and adult-specific manipulation of gene activity, future genetic screens will be able to identify new molecules involved in CNS axonal regeneration. A selected set of several hundreds of genes could easily be screened for enhancing the regenerative response of damaged neurons using this novel injury paradigm. Alternatively, genome-wide primary reverse genetic screens for axon outgrowth can be performed using the LNv to enrich for a set of genes involved in the induction of axonal outgrowth. These can then be taken further to test for their capacity of inducing regeneration after injury. These kinds of approaches will result in a selection of potential regeneration genes and as such result in a very valuable contribution to the studies of axonal regeneration. Such molecules should be prime candidates for additional testing in mammalian systems. In addition, the brain culture system makes a living Drosophila brain accessible for various micromanipulations. We show that cultured brains retain overall axonal integrity, expression of immunohistochemical markers, molecular characteristics, such as circadian oscillation of protein expression, and electrophysiological activity for several days in the explant culture. Many other applications for this explant and culture technology can be imagined: direct visualization of dynamic processes such as vesicular transport (e.g., by expression of Synaptobrevin–GFP), activity of neurons in networks (Miesenbock and Kevrekidis, 2005) in a living brain, addition of pharmacological compounds to the culture medium to interfere with pathways or molecules of interest, transplantation of transgenic cell populations from one brain to the other, and study of cell migration in living Drosophila brain tissue.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the a Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (FWO) Aspirant Doctoral Fellowship (M.L.); an Institunt voor Innovatie door Wetenschap en Technologie Postdoctoral Fellowship (M.K.); Flanders Institute for Biotechnology (VIB), an EMBO Young Investigator Award, a Katholieke Universiteit Leuven Concerted Research Action Grant, FWO Grants G.0444.05 and G.0543.08, and a Johnson & Johnson Corporate Office of Science and Technology/VIB Proof of Concept Grant (B.A.H.); and National Science Foundation Grants IBN-0323466 and IBN-0092753 and National Institutes of Health Grant R01-NS046750 (T.C.H.). We thank Paul Taghert, John Kiger, Ron Davis, and the Bloomington Stock Center (University of Indiana, Bloomington, IN) for antibodies and flies. We are grateful to Pierre Vanderhaeghen and Lara Passante for their help with slice culture techniques and Balint Rubovszky for technical assistance with the electrophysiological recordings. We also thank members of the Hassan laboratory for helpful discussions and particularly Sven Vilain for the drawings in the figures and Patrik Verstreken for comments on this manuscript.

References

- Adachi-Yamada T, Fujimura-Kamada K, Nishida Y, Matsumoto K. Distortion of proximodistal information causes JNK-dependent apoptosis in Drosophila wing. Nature. 1999;400:166–169. doi: 10.1038/22112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenky M, Wagner S, Yarom Y, Matzner H, Cohen S, Castel M. The suprachiasmatic nucleus in stationary organotypic culture. Neuroscience. 1996;70:127–143. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00327-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdnik D, Chihara T, Couto A, Luo L. Wiring stability of the adult Drosophila olfactory circuit after lesion. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3367–3376. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4941-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bier E. Drosophila, the golden bug, emerges as a tool for human genetics. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:9–23. doi: 10.1038/nrg1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilen J, Bonini NM. Drosophila as a model for human neurodegenerative disease. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:153–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.110304.095804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutros M, Paricio N, Strutt DI, Mlodzik M. Dishevelled activates JNK and discriminates between JNK pathways in planar polarity and wingless signaling. Cell. 1998;94:109–118. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81226-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown HL, Cherbas L, Cherbas P, Truman JW. Use of time-lapse imaging and dominant negative receptors to dissect the steroid receptor control of neuronal remodeling in Drosophila. Development. 2006;133:275–285. doi: 10.1242/dev.02191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai D, Qiu J, Cao Z, McAtee M, Bregman BS, Filbin MT. Neuronal cyclic AMP controls the developmental loss in ability of axons to regenerate. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4731–4739. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-04731.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin C, Miyaguchi K, Segal M. Dendritic spine density and LTP induction in cultured hippocampal slices. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:1614–1623. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.3.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feany MB, Bender WW. A Drosophila model of Parkinson's disease. Nature. 2000;404:394–398. doi: 10.1038/35006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs SM, Truman JW. Nitric oxide and cyclic GMP regulate retinal patterning in the optic lobe of Drosophila. Neuron. 1998;20:83–93. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80436-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu H, O'Dowd DK. Cholinergic synaptic transmission in adult Drosophila Kenyon cells in situ. J Neurosci. 2006;26:265–272. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4109-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallem EA, Carlson JR. The odor coding system of Drosophila. Trends Genet. 2004;20:453–459. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin PE. The circadian timekeeping system of Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2005;15:R714–R722. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel NY, Strittmatter SM. Can regenerating axons recapitulate developmental guidance during recovery from spinal cord injury? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:603–616. doi: 10.1038/nrn1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan BA, Bermingham NA, He Y, Sun Y, Jan YN, Zoghbi HY, Bellen HJ. atonal regulates neurite arborization but does not act as a proneural gene in the Drosophila brain. Neuron. 2000;25:549–561. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoopfer ED, McLaughlin T, Watts RJ, Schuldiner O, O'Leary DD, Luo L. Wlds protection distinguishes axon degeneration after injury from naturally occurring developmental pruning. Neuron. 2006;50:883–895. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko M, Hall JC. Neuroanatomy of cells expressing clock genes in Drosophila: transgenic manipulation of the period and timeless genes to mark the perikarya of circadian pacemaker neurons and their projections. J Comp Neurol. 2000;422:66–94. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000619)422:1<66::aid-cne5>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerschensteiner M, Schwab ME, Lichtman JW, Misgeld T. In vivo imaging of axonal degeneration and regeneration in the injured spinal cord. Nat Med. 2005;11:572–577. doi: 10.1038/nm1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiger JA, Jr, O'Shea C. Genetic evidence for a protein kinase A/cubitus interruptus complex that facilitates processing of cubitus interruptus in Drosophila. Genetics. 2001;158:1157–1166. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.3.1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiger JA, Jr, Eklund JL, Younger SH, O'Kane CJ. Transgenic inhibitors identify two roles for protein kinase A in Drosophila development. Genetics. 1999;152:281–290. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.1.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppa S, Bohmann D. Diverse functions of JNK signaling and c-Jun in stress response and apoptosis. Oncogene. 1999;18:6158–6162. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyssen M, Hassan BA. A fruitfly's guide to keeping the brain wired. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:46–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyssen M, Ayaz D, Hebert SS, Reeve S, De Strooper B, Hassan BA. Amyloid precursor protein promotes post-developmental neurite arborization in the Drosophila brain. EMBO J. 2005;24:2944–2955. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Ohlmeyer JT, Lane ME, Kalderon D. Function of protein kinase A in hedgehog signal transduction and Drosophila imaginal disc development. Cell. 1995;80:553–562. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90509-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald JM, Beach MG, Porpiglia E, Sheehan AE, Watts RJ, Freeman MR. The Drosophila cell corpse engulfment receptor Draper mediates glial clearance of severed axons. Neuron. 2006;50:869–881. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulies C, Tully T, Dubnau J. Deconstructing memory in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2005;15:R700–R713. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire SE, Le PT, Osborn AJ, Matsumoto K, Davis RL. Spatiotemporal rescue of memory dysfunction in Drosophila. Science. 2003;302:1765–1768. doi: 10.1126/science.1089035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miesenbock G, Kevrekidis IG. Optical imaging and control of genetically designated neurons in functioning circuits. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:533–563. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.051804.101610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann S, Bradke F, Tessier-Lavigne M, Basbaum AI. Regeneration of sensory axons within the injured spinal cord induced by intraganglionic cAMP elevation. Neuron. 2002;34:885–893. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00702-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitabach MN, Blau J, Holmes TC. Electrical silencing of Drosophila pacemaker neurons stops the free-running circadian clock. Cell. 2002;109:485–495. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00737-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J, Cai D, Dai H, McAtee M, Hoffman PN, Bregman BS, Filbin MT. Spinal axon regeneration induced by elevation of cyclic AMP. Neuron. 2002;34:895–903. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00730-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raivich G, Makwana M. The making of successful axonal regeneration: genes, molecules and signal transduction pathways. Brain Res Rev. 2007;53:287–311. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raivich G, Bohatschek M, Da Costa C, Iwata O, Galiano M, Hristova M, Nateri AS, Makwana M, Riera-Sans L, Wolfer DP, Lipp HP, Aguzzi A, Wagner EF, Behrens A. The AP-1 transcription factor c-Jun is required for efficient axonal regeneration. Neuron. 2004;43:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed BH, Wilk R, Lipshitz HD. Downregulation of Jun kinase signaling in the amnioserosa is essential for dorsal closure of the Drosophila embryo. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1098–1108. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00318-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renn SC, Park JH, Rosbash M, Hall JC, Taghert PH. A pdf neuropeptide gene mutation and ablation of PDF neurons each cause severe abnormalities of behavioral circadian rhythms in Drosophila. Cell. 1999;99:791–802. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81676-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehgal A, Price JL, Man B, Young MW. Loss of circadian behavioral rhythms and per RNA oscillations in the Drosophila mutant timeless. Science. 1994;263:1603–1606. doi: 10.1126/science.8128246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer OT, Rosbash M, Truman JW. Sequential nuclear accumulation of the clock proteins period and timeless in the pacemaker neurons of Drosophila melanogaster. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5946–5954. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-14-05946.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeba V, Gu H, Sharma VK, O'Dowd DK, Holmes TC. Circadian- and light-dependent regulation of resting membrane potential and spontaneous action potential firing of Drosophila circadian pacemaker neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2008a;99:976–988. doi: 10.1152/jn.00930.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeba V, Sharma VK, Gu H, Chou YT, O'Dowd DK, Holmes TC. Pigment dispersing factor-dependent and -independent circadian locomotor behavioral rhythms. J Neurosci. 2008b;28:217–227. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4087-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman JM, Shulman LM, Weiner WJ, Feany MB. From fruit fly to bedside: translating lessons from Drosophila models of neurodegenerative disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2003;16:443–449. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000084220.82329.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver J, Miller JH. Regeneration beyond the glial scar. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:146–156. doi: 10.1038/nrn1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srahna M, Leyssen M, Choi CM, Fradkin LG, Noordermeer JN, Hassan BA. A signaling network for patterning of neuronal connectivity in the Drosophila brain. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e348. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoppini L, Buchs PA, Muller D. A simple method for organotypic cultures of nervous tissue. J Neurosci Methods. 1991;37:173–182. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(91)90128-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JW, Wong AM, Flores J, Vosshall LB, Axel R. Two-photon calcium imaging reveals an odor-evoked map of activity in the fly brain. Cell. 2003;112:271–282. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman TA, Riquelme PA, Ivic L, Flint AC, Kriegstein AR. Calcium waves propagate through radial glial cells and modulate proliferation in the developing neocortex. Neuron. 2004;43:647–661. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanik MF, Cinar H, Cinar HN, Chisholm AD, Jin Y, Ben-Yakar A. Neurosurgery: functional regeneration after laser axotomy. Nature. 2004;432:822. doi: 10.1038/432822a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yiu G, He Z. Glial inhibition of CNS axon regeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:617–627. doi: 10.1038/nrn1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]