Abstract

Objectives

On May 1, 1996, Ontario, Canada, amended the Liquor Licence Act to extend the hours of alcohol sales and service in licensed establishments from 1 to 2 a.m. The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of extended drinking hours on two cities in southwestern Ontario, Canada, one of which (London) would be affected by the alcohol control policy of extended drinking hours and the second city (Windsor) would be affected by two alcohol policies, extended drinking hours, and cross-border legal drinking age differences between Ontario and Michigan. Specifically, this study tested whether there were differences in impaired driving and assault charges in London and Windsor, Ontario, concomitant with the extended drinking hour amendment.

Methods

A quasi-experimental design using interrupted time series was used to assess changes. The analyzed data sets were monthly police impaired driving and assault charges data for Ontario, for the 11–12 p.m., 12–1 a.m., 1–2 a.m., 2–3 a.m. and 3–4 a.m. time windows, for 4 years pre- and 3 years post-policy change.

Results

Overall, London and Windsor exhibited significant overall reductions in impaired driving charges and no changes for assault charges aggregated over the 11 p.m.–4 a.m. time period after the drinking hours were extended. Within the different time windows, London showed significant decreases for the 1–2 a.m. Sunday–Wednesday and Thursday–Sunday time periods and a significant increase for the Sunday–Wednesday 3–4 a.m. time period, while Windsor demonstrated significant decreases in impaired driving charges for 1–2 a.m. Sunday–Wednesday and Thursday–Saturday time periods and significant increases for Sunday–Wednesday 2–3 and 3–4 a.m. and for Thursday–Saturday 2–3 a.m. For assault charges, no overall pre–post differences were found for the aggregated 11 p.m.–4 a.m. time period for either city. When the data were disaggregated by hour, a significant decrease was found in London for Thursday–Saturday 1–2 a.m. and significant increases for Sunday–Wednesday 2–3 a.m. and Thursday–Saturday 3–4 a.m. time periods, while no significant decreases were found in Windsor during the 1–2 a.m. time periods and one significant increase occurred during the Thursday–Saturday 2–3 a.m. time period.

Conclusions

These findings, based on police data, suggest no overall effect on charges aggregated over the 11 p.m. to 4 a.m. time window, although some differences were observed for the different hours after 2 a.m., with a possible effect of the one hour extension of drinking in licensed establishments.

Keywords: Drinking Hours, Alcohol Control Policy, Impaired Driving, DUI, DWI, Assaults

INTRODUCTION

On May 1, 1996, the Ontario provincial government amended the Liquor Licence Act to extend hours of alcohol sales and service in licensed establishments from 1 to 2 a.m. to be consistent with closing hours of bordering U.S. states and Canadian provinces. One governmental rationale for extending the drinking hours was as follows: “We believe that permitting licensed establishments to sell and serve alcohol to 2 a.m. will help the tourism and convention industry and the hospitality industry, which loses business when patrons go over the border into New York or Michigan and into Manitoba or Quebec, when Ontario bars and restaurants close.… Ontario has the earliest hours in Canada and in American states bordering Ontario and we believe this change will reduce the number of patrons who cross the border when Ontario’s bars and restaurants close” (Sterling, 1996). Moreover, the government hypothesized that there would be less neighborhood disruption, as patron exodus from establishments would occur over a longer time period, and less likelihood of patrons “loading up” on last call (Liquor Licence Board of Ontario, 1995).

However, years of research have shown a connection between the rates of drinking across populations and rates of alcohol-related problems (e.g., Mann, 2005; Mann and Anglin, 1990; Room et al., 2005; Smart and Mann, 1995; Smart et al., 1998). Although the relationship among physical availability of alcohol, alcohol consumption, and alcohol-related problems is multifaceted and complex, availability theory asserts that alcohol availability influences the levels of alcohol consumption, which in turn influence the levels of alcohol-related problems, such as rates of impaired driving and assaults (Chikritzhs and Stockwell, 2007; Grube and Stewart, 2004; Mann, 2005; Ragnarsdóttir et al., 2002; Rush, et al., 1986; see also www.icap.org/Portals/0/download/all_pdfs/ICAP_Reviews_Eng-//lish/review1.pdf). Based on availability theory, one would hypothesize that extending drinking hours in Ontario could increase general population-based alcohol consumption, which would influence the levels of alcohol-related problems, such as rates of impaired driving and assaults (Adrian et al., 2001; Room et al., 2005; Smart and Mann, 1987).

A second problem could also occur with specific populations in U.S.–Canada cross-border jurisdictions. The minimum drinking age in Ontario is 19, whereas in all American states it is 21 years of age. An unintended consequence of extending drinking hours in Ontario could be increased availability of alcohol for underage U.S. patrons who cross the border to legally consume alcohol in Canada (Clapp et al., 2001). Substantive cross-border drinking occurs, with police reporting problems such as impaired driving and assaults (Clapp et al., 2001; see also http://www.statenews.com/article.phtml?pk=28540). Thus, increased alcohol availability through extended drinking hours could increase cross-border drinking, leading to increased alcohol-related harms. This amendment provided the opportunity to evaluate an important alcohol policy.

The Evidence

Research on hours and days of service is limited. Vingilis et al. (2005) found that most studies on the effects of extended hours of service have found mixed results. Most studies have examined collision or hospital data and few have examined police data. Yet impaired driving and alcohol-related assaults have been a public concern related to liberalization of alcohol control policies (e.g., DeJong and Hingson, 1998; Measham and Brain, 2005; Room et al., 2005; Single and Tocher, 1992; Wagenaar et al., 2000).

Chikritzhs and colleagues (Chikritzhs and Stockwell, 2002; Chikritzhs et al., 1997) evaluated the public health and safety impact of extended trading permit hours in Perth, Australia. The extended trading permit allowed an additional hour of serving alcohol, typically at peak times, such as early on Saturday or Sunday, to some but not all applicants. Chikritzhs et al. (1997) conducted a study of 20 pairs of hotels matched on levels of assault prior to the introduction of late trading and wholesale purchase of alcohol in Perth between 1991 and 1995. Levels of monthly assaults more than doubled in hotels that had received extended hours permits compared to no changes in hotels with normal hours, but no significant increases in road crashes were found related to the extended trading permits. Subsequent evaluations (Chikritzhs and Stockwell, 2002, 2007) examined the impact of extended trading hours on levels of violent assaults on or near licensed establishments between 1991 and 1997 and on breath alcohol concentrations (BACs) of apprehended impaired drivers. They found significant increases in monthly assault rates for hotels with extended trading permits after the introduction of extended trading hours that were mostly accounted for by increased volumes of alcohol purchase by late trading hotels (Chikritzhs and Stockwell, 2002). For impaired driving offenses, late trading hours were associated with varied results and interaction effects. For females apprehended between 10:01 p.m. and 12 a.m. who had last drunk at an extended drinking hours hotel, lower BACs were found, whereas for males aged 18–25 years who were apprehended between 12:01 a.m. and 2:00 a.m. and had last drunk at an extended drinking hours hotel, BACs were significantly higher when compared to patrons of non-extended trading hours hotels, although the study was confounded by changes in the legal BAC limit, which significantly reduced BACs after the legal limit was reduced from .08 to .05 mg/100 mL (Chikritzhs and Stockwell, 2007).

Vingilis and colleagues examined the impact of extended drinking hours on casualties and found a complex pattern of outcomes, whereby in Ontario as a whole, no increases were found in alcohol-related, police-reported motor vehicle collision (MVC) driver fatalities (Vingilis et al., 2005) or in MVC injuries based on hospital trauma data, although increases in non-MVC injuries based on hospital trauma data were found for the time period during which the drinking hour was extended (Vingilis et al., 2007). A survey of licensed establishments in Ontario, reported by Vingilis et al. (2005), suggested that some licensed establishments did not implement the extended drinking hours. This would suggest that alcohol availability might not have increased greatly in the province as a whole, despite the regulation change. Moreover, a number of road safety initiatives that occurred within a two-year interval before and after the change in hours of sale (Boase and Tasca, 1998; Mann et al., 2000, 2002) may have created a declining trend in the drinking driving problem that masked the effects of a small increase in alcohol availability. Finally, the limited number of alcohol-related driver fatalities and the rarity of MVC fatalities may have made the MVC data set a less sensitive measure to detect changes.

However, Vingilis and colleagues (2006) found evidence of increased alcohol-related casualties, based on police MVC reporting forms, when they examined the impact of extended drinking hours on cross-border drinking of Windsor, Ontario, and Detroit, Michigan, where the closing hours in Windsor became the same as in Detroit. The Windsor–Detroit region was chosen for study because of documented problems of cross-border drinking. In Windsor, a region with a high licensed establishment density, a significant increase was found for alcohol-related MVC casualties, after the drinking hours were extended. However, the Detroit region showed a statistically significant decrease in alcohol-related MVC casualties concomitant with Ontario’s drinking hour extension. No similar trends were found for the province of Ontario and the state of Michigan as a whole. Moreover, a significant decrease was found for MVC casualties involving vehicles with Ontario license plates in the Detroit region, suggesting that persons from Windsor were less likely to cross the border for an extra hour of drinking when the drinking period was extended in Ontario. For MVC casualties involving vehicles with U.S. license plates in the Windsor region, a total of 69 occurred and 20 involved drivers between the ages of 16 and 20. Although the intervention time series analyses indicated no pre–post change for MVC casualties for drivers of all ages or for 12- to 20-year-olds with U.S. plates, on average for U.S.-license-plated drivers of all ages, 0.769 MVC casualties occurred monthly preintervention and 0.906 MVC casualties occurred monthly postintervention, while for U.S.-license-plated drivers aged 16–20, on average 0.262 MVC casualties occurred monthly before the policy change compared to 0.281 MVC casualties monthly after the policy change. Thus, the results of the different casualty data sets show mixed results.

Yet, heavy imbibing may still have consequences, in terms of “neighborhood disruption,” which the government suggested the extended regulatory change would decrease. Two recent newspaper and magazine articles from two Ontario cities provide some anecdotal evidence of potential differential effect of extended drinking hours on alcohol-related harms related to licensed establishments. Balkissoon (2007), writing a cover story in a Toronto, Ontario magazine, stated:

The crowd stretches the length of Richmond Street from Peter to Simcoe, full of attitude and soaked in booze. It’s 2:30 a.m. and although the clubs are closing their doors nobody wants to go home. … One group of partiers tries, unsuccessfully, to thread through another group holding court on Peter Street. Shoulders bump, slurred swearwords are exchanged, there is some pushing, and suddenly a pile of boys are rolling around on the pavement, making mean faces and throwing punches. … But not everyone goes home the way they came. … In 2006, the police laid 448 people in the district with assault; 17 were additionally charged with aggravated assault—a beating causing serious bodily harm. (p. 46)

Similarly, Morgan (2007) wrote in a London, Ontario, newspaper:

He [Valente, owner of local bar and grill] also shared the opinion of the downtown club owner that the main problem is not so much student drinking, but the extended bar hours which came into effect in 1996, changing closing time from 1:00 am to 2:00 am. “Having the province pushing bar hours back makes no sense,” said Valente. Closing time aside, behavioural problems associated with student drinking have long been a concern for local authorities. … [T]he downtown club owner told Scene, “I never had any fights (in my bar) until eight years ago.” (p. 4)

These anecdotes point to a variety of alcohol-related harms that have been observed and suggest that it would be important to examine the impact of extended drinking hours on crime-related harms, such as impaired driving or assaults.

The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of extended drinking hours on two cities in southwestern Ontario, one city (London) that would be affected by the extended drinking hours change and the second city (Windsor) that would be affected by the extended drinking hours change and cross-border drinking. Specifically, this study tested whether there were differences in impaired driving and assault charges in London and Windsor, Ontario, concomitant with the extended drinking hour amendment. London, within the county of Middlesex, is 200 kilometers due east of Windsor, with a population of 348,000. London is home to one university and community college. Windsor, within the county of Essex, Canada’s southernmost city with a regional population of 279,000, is situated on the south shore of the Detroit River and Lake St. Clair, at the center of the Great Lakes basin and directly across from Detroit, Michigan. Over 16 million vehicles cross the Windsor–Detroit border every year, making this border crossing the busiest U.S.–Canada crossing (http://www.tc.gc.ca/mediaroom/releases/nat/2004/04-hlll). Windsor is also home to one university and one community college. Both cities are situated within a rural, agricultural region, have major vehicle manufacturing economies, and socio-demographics are highly similar for both cities (Alder et al., 1996; Vingilis et al., 1999).

METHODS

London Police Services and Windsor Police Services data sets were used, which include monthly impaired driving and assault offences for the 11:00–11:59 p.m. (denoted as 11 p.m.–12 a.m.), 12:00–12:59 a.m. (12–1 a.m.), 1.00–1:59 a.m. (1–2 a.m.),] 2:00–2:59 a.m. (2–3 a.m.), and 3:00–3:59 a.m. (3–4 a.m.) time windows, for 4 years pre- and 3 years post-policy change in London and Windsor, Ontario. Moreover, the data were further broken down by day of week (Sunday–Wednesday and Thursday–Saturday evenings) to examine weekday vs. weekend patterns, as a post-policy survey by the Liquor Licence Board of Ontario found that licensed establishments in smaller communities often maintained their 1 a.m. closing time for Sunday through Wednesday nights because of lack of sufficient business but kept open until 2 a.m. on Thursday through Saturday nights (Bolton, 1996).

Two types of Canadian Criminal Code offense categories were examined. Impaired driving is a class of Criminal Codes offenses that includes operation of a motor vehicle while impaired by alcohol or a drug; exceeds 80 mg of alcohol in 100 mL blood (section 253 (a)(b)), and refuses to provide breath sample (section 254(5)). Assaults are Criminal Code offenses that include assault—a person who intentionally applies force without consent of another person or who attempts or threatens to apply force (section 265 (1a–c), 266 (a) (b); assault with a weapon/causing bodily harm (section 267 (1ab); and aggravated assault (section 268(2)).

Statistical Time Series Analyses

The impaired driving and assault charges data sets were totaled into monthly counts collapsed over the 11 p.m.–4 a.m. time periods and disaggregated according to hour (11 p.m.–4 a.m.), generating six time series for each data set. Monthly data for 4 years pre-intervention and 3 years post-intervention were chosen to ensure adequate power; a sample of 84 monthly data points with the intervention month at 48 months has an 86.7% chance of detecting a step intervention whose magnitude is one standard deviation with an alpha of .05 (McLeod and Vingilis, 2005). Due to data availability, the London impaired driving and assault charges time series comprised n = 85 monthly observations beginning May 1992 and ending May 1999, and the Windsor impaired driving and assault charges time series comprised n = 60 monthly observations beginning January 1994 and ending December 1998. As in the detailed statistical description provided in Vingilis et al. (2005), following exploratory analyses, the simple step intervention model (Box and Tiao, 1976) was fitted to test statistically for the presence of shifts in the level of the time series. After the model was fit, plots of the residual autocorrelation function were examined to check for possible autocorrelation. If autocorrelation was found, then a suitable model was determined for Nt, and the model was refit using maximum likelihood estimation. In most cases, our analysis identified the term Nt as white noise so linear regression analysis could be used. In some cases the data were adequately represented by the Poisson distribution, whereas in other cases it was necessary to use a negative binomial regression (Venables and Ripley, 2002) due to overdispersion in the data. The log link function was used. Poisson and negative binomial regression were fit using exact maximum likelihood estimation (Currie, 1995). In general, we found that these models agreed very well with the results obtained by fitting the normal linear regression model as might be expected from the robustness result of Hjort (1994).

RESULTS

Impaired Driving Charges

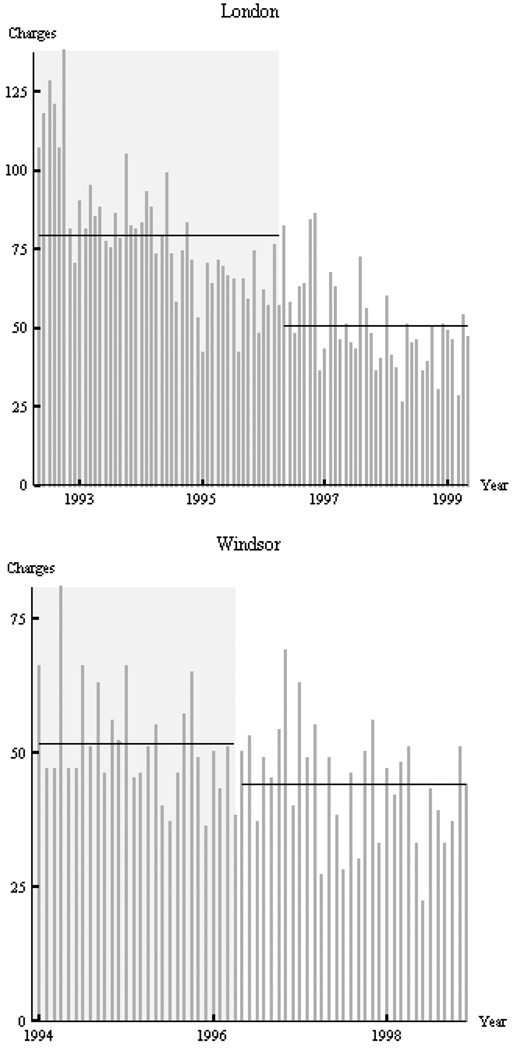

London and Windsor total monthly impaired driving charges pre–post policy change were aggregated over the 11 p.m.–4 a.m. time periods to determine whether there had been overall increases in impaired driving charges over the evening drinking hours in relation to the introduction of extended drinking hours (Figure 1). As can be seen, overall impaired driving charges significantly decreased for the 11 p.m. to 4 a.m. time window in both London (p < .01) and Windsor (p <.01).

Figure 1.

Number of impaired driving charges between 11 p.m. and 4 a.m. in London and Windsor. The regression lines indicate the linear trends. The shaded area corresponds to the pre-intervention time period up to and including April 1996.

The data were disaggregated to examine changes for individual hours between 1 and 4 a.m. to determine whether the downward trends observed in the aggregate data shown in Figure 1 were due to shifts in peak late evening, impaired driving charges from 1–2 a.m. to 2–3 a.m. time windows after the introduction of the extended drinking hours, effective May 1, 1996. In London, significant decreases were found after the introduction of the extended drinking hours for the Sunday–Wednesday 1–2 a.m. time period (p < .0001) and for the Thursday–Saturday 1–2 a.m. time period (p < .0001), whereas only one significant increase was found for the Sunday–Wednesday 3–4 a.m. (p = .004) time period. In Windsor, significant decreases were found commensurate with the introduction of the extended drinking hours for the Sunday–Wednesday 1–2 a.m. time period (p = .00004) and for the Thursday–Saturday 1–2 a.m. time period (p < .00001), and significant increases were found for the Sunday–Wednesday 2–3 a.m. (p = .014) and 3–4 a.m. (p = .037) time periods and for the Thursday–Saturday 2–3 a.m. (p = .0004) time period.

Assault Charges

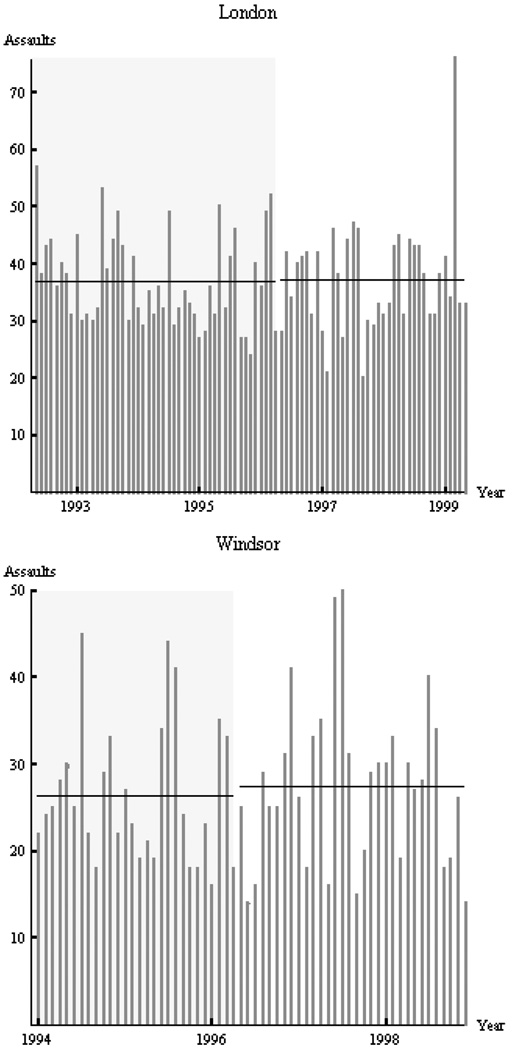

Figure 2 displays the London and Windsor total monthly assault charges pre–post policy change aggregated over the 11 p.m.–4 a.m. time periods. No significant pre–post differences were found for London and Windsor in relation to the extended drinking hours. For the disaggregated data, in London, a significant decrease was found for the Thursday–Saturday 1–2 a.m. time period (p = .004) and the trend was nearing significance for the Sunday–Wednesday 1–2 a.m. (p = .07), whereas significant increases were found for the Sunday–Wednesday 2–3 a.m. (p = .03) and Thursday–Saturday 3–4 a.m. (p =.02) time periods. In Windsor, no significant pre–post decreases and only one significant pre–post increase were found with the introduction of the extended drinking hours for the Thursday–Saturday 2–3 a.m. (p = .001) time period, whereas for the Sunday–Wednesday 2–3 a.m. time period, the trend was nearing significance (p = .07).

Figure 2.

Number of assault charges between 11 p.m. and 4 a.m. in London and Windsor. The regression lines indicate the linear trends. The shaded area corresponds to the pre-intervention time period up to and including April 1996.

DISCUSSION

These findings, based on Canadian Criminal Code charges police data, suggest no overall effect of the one-hour extension of drinking in licensed establishments on impaired driving and assault charges in both locales. Over the 11 p.m. to 4 a.m. time period, the number of impaired driving charges significantly decreased in both London and Windsor, although there seemed to be a temporal shift in charges, whereby significant reductions were observed in both London and Windsor during the 1–2 a.m. time periods, the time period when historically licensed establishments had closed. However, after the drinking hours were extended, in London the Sunday–Wednesday 2–3 a.m. time period showed a significant increase, whereas three of the four time periods after 2 a.m. in Windsor demonstrated significant increases in impaired driving charges.

The assault charges, on the other hand, showed no overall change over the 11 p.m. to 4 a.m. time period. The examination of the disaggregated data revealed that in London a significant decrease was found for Thursday–Saturday 1–2 a.m. and significant increases for the Sunday–Wednesday 2–3 a.m. and Thursday–Saturday 3–4 a.m. time periods, whereas in Windsor no significant decreases during the 1–2 a.m. time periods and one significant increase during the Thursday–Saturday 2–3 a.m. time period were found. These findings would suggest some decrease in impaired driving charges but no changes in assault charges commensurate with the extended drinking hours. These data are congruent with the findings of Vingilis and colleagues. Their studies found no significant changes in MVC fatalities for Ontario as a whole (Vingilis et al., 2005), whereas their trauma study found no significant pre–post differences in MVC injuries but significant increases in non-MVC injuries, which included assaults, presenting at Ontario emergency departments (Vingilis et al., 2007). These findings would support the contention that road safety initiatives may have deterred impaired driving behavior. For example, Boase and Tasca (1998) found that the overall collision rate for novice drivers of all ages decreased by 31% after Ontario’s Graduated Licensing Program was implemented in 1994. Similarly, Mann et al. (2002) found a reduction of 17.3% in the proportion of fatally injured drivers who were over the legal limit after the Administrative Licence Suspension Law was introduced at the end of 1996. Furthermore, the Administration Licence Suspension Law and the Graduated Licensing Law were modeled in the initial time series analyses of the MVC, drinking–driving fatality data conducted in our first study of extended drinking hours. (Vingilis et al., 2005) modeled in the Administrative Licence Suspension Law and the Graduated Licensing Law. Initial analyses did find an effect for the Administrative Licence Suspension Law but not for the Graduated Licensing Law, possibly because the Graduated Licensing Law coincided too closely with the extended drinking hours policy change for a distinct statistical effect to be found. Moreover, there was little difference in pre–post changes between the two cities, suggesting that cross-border drinking might not have augmented the effect of extended drinking hours in Windsor.

It is important to point out that there are a number of limitations with this study. First, the number of charges laid is directly dependent on availability of police officers to lay charges. Thus, the number of charges laid represents detected and sanctioned offenses, not necessarily the true number of offenses committed. Second, the impaired driving and assault charges may not have emanated from the licensed establishments. Unfortunately, the charges data did not provide information on where the offender had his last drink before the charges were laid. Third, we have no direct evidence of how many of the charges laid in Windsor were to persons from the Michigan area, so direct information is not available on cross-border drinking-related harms.

That said, this study extends our knowledge as, although much has been written about alcohol availability theory, very little research has been conducted on the effect of extended drinking hours on impaired driving and assaults. Yet, the literature on strategies to reduce impaired driving or assaults discuss alcohol control policies, such as hours of sale, as important influences (Babor et al., 2003; DeJong and Hingson, 1998; Stewart, 2007; Vingilis, 2007). For example, Babor et al. (2003) assessed 31 different alcohol control policies that could affect alcohol-related harms according to four criteria: evidence of effectiveness; quality and consistency of evidence; cross-cultural generalizability; and monetary and other costs of implementation and sustainability. Hours or days of sale ranked third. The results of this study suggest that with the one-hour extension of drinking hours in Ontario, there was no evidence of change in the overall alcohol-related harms of impaired driving and assault charges in two Ontario cities. Despite no overall changes in offenses, these findings do not support the governmental rationale that the extended drinking hours policy would lead to less neighborhood disruption, as patron exodus from establishments would occur over a longer time period, and less likelihood of patrons “loading up” on last call. Although total impaired driving charges decreased (but possibly for reasons other than the alcohol control policy), the total assault charges stayed the same. Moreover, when the impaired driving and assault charges data were disaggregated by hour, results suggested a temporal shift in alcohol-related harms from peaking after 1 a.m. to peaking after 2 a.m.

In summary, this study confirms that the relationship between the alcohol policy of hours of sale and alcohol-related harms is complex (Room et al., 2005; Vingilis, 2007; see also www.icap.org/Portals/0/download/all_pdfs/ICAP_Reviews_English/review1.pdf). The literature on availability theory suggests that factors affecting aggregate alcohol consumption are strongly related to availability factors only when other conditions remain unchanged (Room et al., 2005; Vingilis, 2007; see also www.icap.org/Portals/0/download/all_pdfs/ICAP_Reviews_English/review1.pdf). Availability factors are mediated by a variety of cultural, political, and legal factors (www.icap.org/Portals/0/download/all_pdfs/ICAP_Reviews_English/review1.pdf). Moreover, the fact that the extended drinking hour change was only an increase of one hour and that evidence suggests that some establishments did not extend their drinking hours (Vingilis et al., 2005) may not have been sufficient to significantly affect consumption and harms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Alcohol and Alcohol Abuse.

Footnotes

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

REFERENCES

- Adrian M, Ferguson BS, Her M. Can Alcohol Price Policies Be Used to Reduce Drunk Driving? Evidence from Canada. Subst. Use Misuse. 2001;36(13):1923–1957. doi: 10.1081/ja-100108433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alder A, Vingilis E, Mai V. Community Health and Well-Being in Southwestern Ontario: A Resource for Planning. London, Ontario: Middlesex-London Health Unit-University of Western Ontario; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Babor T, Caetano R, Creswell S, et al. Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity—Research and Public Policy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Balkissoon D. Party Monsters. Toronto Life. 2007;41(8):44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Boase P, Tasca L. Graduated Licensing System Evaluation: Interim Report ’98. Toronto, Canada: Ministry of Transportation Ontario; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton T. Inspector Survey. Toronto, Canada: Liquor Licensing Board of Ontario; 1996. [Unpublished data] [Google Scholar]

- Box GEP, Tiao GC. Intervention Analysis with Applications to Economic and Environmental Problems. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1976;70:70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Canada. Martin’s Annual Criminal Code 1991. Aurora, Ontario, Canada: Canada Law Book Inc.; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Chikritzhs T, Stockwell T. The Impact of Later Trading Hours for Australian Public Houses (Hotels) on Levels of Violence. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2002;63(5):591–599. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikritzhs T, Stockwell T. The Impact of Later Trading Hours for Hotels (Public Houses) on Breath Alcohol Levels of Apprehended Impaired Drivers. Addiction. 2007;102:1609–1617. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikritzhs T, Stockwell T, Masters L. Evaluation of the Public Health and Safety Impact of Extended Trading Permits for Perth Hotels and Night Clubs. Sydney, Australia: National Centre for Research into the Prevention of Drug Abuse, Curtin University of Technology; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Clapp JD, Voas RB, Lange JE. Cross-Border College Drinking. J. Saf. Res. 2001;32:299–307. [Google Scholar]

- Currie ID. Maximum-Likelihood-Estimation and Mathematica. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. C. Appl. Stat. 1995;44(3):1609–1617. [Google Scholar]

- DeJong W, Hingson R. Strategies to Reduce Driving under the Influence of Alcohol. Annu. Rev. Publ. Health. 1998;19:359–378. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grube JW, Stewart K. Preventing Impaired Driving Using Alcohol Policy. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2004;5:199–207. doi: 10.1080/15389580490465229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjort NL. The Exact Amount of T-Ness That the Normal Model Can Tolerate. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1994;89(426):665–675. [Google Scholar]

- Liquor Licence Board of Ontario. Minister’s Briefing Note: Extended Hours. Toronto, Ontario: Liquor Licence Board of Ontario; 1995. [December 18, 1995]. [Google Scholar]

- Mann RE. Availability as a Law of Addiction. Addiction. 2005;100(7):924–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann RE, Anglin L. Alcohol Availability, per Capita Consumption, and the Alcohol-Crash Problem. In: Wilson J, Mann R, editors. Drinking and Driving: Advances in Research and Prevention. New York: Guilford Press; 1990. pp. 205–225. [Google Scholar]

- Mann RE, Smart RG, Stoduto G, Adlaf EM, Vingilis E, Beirness D, Lamble R. Changing Drinking-Driving Behaviour: The Effects of Ontario’s Administrative Driver’s Licence Suspension Law. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2000;162:1141–1142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann RE, Smart RG, Stoduto G, Vingilis E, Beirness D, Lamble R. The Early Effects of Ontario’s Administrative Driver’s Licence Suspension Law on Driver Fatalities with a BAC > 80 mg% Can. J. Publ. Health. 2002;93:176–180. doi: 10.1007/BF03404995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod AI, Vingilis E. Power Computations for Intervention Analysis. Technometrics. 2005;47:174–181. doi: 10.1198/004017005000000094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Measham F, Brain K. “Binge Drinking,” British Alcohol Policy and the New Culture of Intoxication. Crime Media Cult. 2005;1(3):262–283. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan C. Reduced Student Business Hurts Local Bars. Scene. 2007;546:4. [Google Scholar]

- Ragnarsdóttir P, Kjartansdóttir A, Daviosdóttir S. Effect of Extended Alcohol Serving-Hours in Reykjavik. In: Room R, editor. The Effects of Nordic Alcohol Policies. What Happens to Drinking and Harm When Alcohol Controls Change? Helsinki, Finland: NAD Publications; 2002. pp. 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Room R, Babor T, Rehm J. Alcohol and Public Health. Lancet. 2005;365:519–530. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17870-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush BR, Gliksman L, Brook R. Alcohol Availability, Alcohol Consumption and Alcohol-Related Damage. The Distribution of Consumption Model. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1986;47:1–10. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1986.47.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Single E, Tocher B. Legislating Responsible Alcohol Service: An Inside View of the New Liquor Licence Act of Ontario. Br. J. Addiction. 1992;87:1433–1443. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb01922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart RG, Mann RE. Large Decreases in Alcohol-Related Problems Following a Slight Reduction in Alcohol Consumption in Ontario 1975–83. Br. J. Addiction. 1987;82:285–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb01482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart RG, Mann RE. Treatment, Health Promotion and Alcohol Controls and the Decrease of Alcohol Consumption and Problems in Ontario: 1975–1993. Alcohol Alcohol. 1995;30(3):337–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart RG, Mann RE, Suurvali H. Changes in Liver Cirrhosis Death Rates in Different Countries in Relation to per Capita Alcohol Consumption and Alcoholics Anonymous Membership. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1998;59(3):245–249. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling Hon N. Statement by The Honourable Norman W. Sterling, Minister of Consumer and Commercial Relations [Ontario]. Changes to Liquor Regulations. 1996. [April 17, 1996]. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart K. Overview and Summary. Traffic Safety and Alcohol Regulation: A Symposium; Transportation Research Circular No. E-C123; Washington, DC. Transportation Research Board of the National Academies; 2007. pp. 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Venables WN, Ripley BD. Modern Applied Statistics with S. 4th ed. New York: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Vingilis E. Limits on Hours of Sales and Service, Effects on Traffic Safety. Traffic Safety and Alcohol Regulation: A Symposium; Transportation Research Circular No. E-C123; Washington, DC. Transportation Research Board of the National Academies; 2007. pp. 120–128. [Google Scholar]

- Vingilis E, McLeod AI, Seeley J, Mann RE, Stoduto G, Compton C, Beirness D. Road Safety Impact of Extended Drinking Hours in Ontario. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2005;37:549–556. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vingilis E, McLeod AI, Seeley J, Mann RE, Voas R, Compton C. The Impact of Ontario, Canada’s Extended Drinking Hours on Cross-Border Cities of Windsor and Detroit. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2006;38(1):63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vingilis E, McLeod AI, Stoduto G, Seeley J, Mann RE. Impact of Extended Drinking Hours in Ontario on Motor-Vehicle Collision and Non-Motor-Vehicle Collision Injuries. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:1–7. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vingilis ER, Brown U, Sarkella J, Stewart M, Hennen BK. Cold/Flu Knowledge, Attitudes and Health Care Practices: Results of a Two-City Telephone Survey. Can. J Publ. Health. 1999;90:205–208. doi: 10.1007/BF03404508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar AC, Harwood EM, Toomey TL, Denk CE, Zander KM. Public Opinion on Alcohol Policies in the United States: Results from a National Survey. J. Publ. Health Pol. 2000;21(3):303–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]