Abstract

T0901317 is a potent non-steroidal synthetic liver X receptor (LXR) agonist. T0901317 blocked androgenic stimulation of the proliferation of androgen-dependent LNCaP 104-S cells and androgenic suppression of the proliferation of androgen-independent LNCaP 104-R2 cells, inhibited the transcriptional activation of an androgen-dependent reporter gene by androgen, and suppressed gene and protein expression of prostate specific antigen (PSA), a target gene of androgen receptor (AR) without affecting gene and protein expression of AR. T0901317 also inhibited binding of a radiolabeled androgen to AR, but inhibition was much weaker compared to the effect of the antiandrogens, bicalutamide and hydroxyflutamide. The LXR agonist T0901317, therefore, acts as an antiandrogen in human prostate cancer cells.

Keywords: T0901317, antiandrogen, androgen, AR, LNCaP, PSA, LXR agonist

Introduction

Since the initial discovery as orphan receptors [1,2], liver X receptors (LXRs) have been shown to be important regulators of cholesterol, fatty acid, and glucose homeostasis. Oxysterols are natural ligands for LXR [3–6]. A few non-steroidal synthetic LXR agonists have been developed, including T0901317 [7] and GW3965 [8]. T0901317 is the most commonly used LXR agonist for investigating physiological roles of the LXRs. Treatment with T0901317 has been reported to improve several disease murine models, including lowering of serum and liver cholesterol level, inhibition of atherosclerosis development, stimulation of insulin secretion, improvement of glucose tolerance, activation of anti-inflammatory effects, and reduction of amyloid beta production related to Alzheimer’s disease [9–14]. Recently, we reported that T0901317 suppressed growth of prostate tumors in athymic mice [15].

Prostate cancer is a very common male-specific malignancy. LNCaP, PC-3, and DU-145 are commonly used prostate cancer cell lines. The LNCaP cancer cell line was established from a human lymph node metastatic lesion of prostatic adenocarcinoma. PC-3 and DU-145 cells were established from human prostatic adenocarcinoma metastatic to bone and to brain respectively. The proliferation of LNCaP cells is androgen-dependent but the proliferation of PC-3 and DU-145 cells is androgen-insensitive. LNCaP cells express androgen receptor (AR), however, PC-3 and DU-145 cells express very little or no AR. AR, an androgen-activated transcription factor, belongs to the steroid nuclear receptor family. Development of the prostate is dependent on androgen signaling mediated through AR, and AR is also important during the development of prostate cancer [16]. LNCaP cells express prostate specific antigen (PSA) upon androgen treatment. PSA is the most commonly used marker for detecting prostate tumor growth in patients. Treatment of LNCaP, PC-3, and DU-145 cells with LXR agonists (T0901317, 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol, or 24(S)-hydroxycholesterol) suppresses the proliferation of these cancer cells [15].

In 1941, Charles Huggins reported that androgen ablation therapy caused regression of primary and metastatic androgen-dependent prostate cancer [17]. However, 80–90% of the patients develop androgen-independent tumors 12–33 months after androgen ablation therapy [18]. To study the progression of prostate cancer, we generated androgen-independent LNCaP sublines (104-R1, 104-R2, and CDXR) from an androgen-dependent LNCaP subline (104-S) after androgen deprivation [19–21]. These androgen-independent LNCaP cells have elevated AR expression and express PSA upon androgen treatment. Androgens paradoxically inhibit the proliferation of these androgen-independent prostate cancer cells [20–24], which is relieved after knockdown or loss of AR expression [21,23,24]. Elevation of AR expression is often observed in advanced prostate tumors in patients [25,26]. T0901317 treatment in athymic mice delays the progression of prostate tumors towards androgen-independency [24]. Since AR and AR signaling is very important for proliferation and progression of prostate cancer cells [19–27] and LXR agonist T0901317 suppresses proliferation and progression of prostate cancer cells [15,24], we determined if T0901317 interacts with androgen receptor and if T0901317 affects AR signaling.

Materials and methods

Materials

N-(2,2,2-trifluoro-ethyl)-N-[4-(2,2,2-trifluoro-1-hydroxy-1-trifluoromethyl-ethyl)-phenyl] benzenesulfonamide (T0901317) was purchased from Alexis Biochemicals (San Diego, CA). 22(R)-Hydroxycholesterol and 24(S)-hydroxycholesterol were purchased from Steraloids (Newport, RI). 17β-hydroxy-17-methylestra-4,9,11-trien-3-one (R1881) and (2RS)-4′-cyano-3-(4-fluorophenylsulfonyl)-2-hydroxyl-2-methyl-3′-(trifluoromethyl)-propionanilide (Casodex, bicalutamide) were obtained from Perkin Elmer (Boston, MA) and Astrazeneca (Wilmington, DE), respectively. [17α-methyl-3H]-7α,17α-dimethyl-19-nortestosterone (mibolerone) ([3H]DMNT) and hydroxyflutamide were obtained from Perkin Elmer (Boston, MA) and Schering-Plough (Kenilworth, NJ), respectively.

Cell Culture

Androgen-dependent LNCaP 104-S cells were maintained and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) supplemented with 1 nM dihydrotestosterone (DHT), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlas, Fort Collins, CO), 50 I.U. penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin (Cellgro, Mediatech) [19–21]. Androgen-independent LNCaP 104-R2, human prostate cancer PC-3, and Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK 293) cells were maintained and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% dextran-coated charcoal stripped fetal bovine serum (CS-FBS), 50 I.U. penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin [19–21]. Trypsin (Mediatech) was used for cell passage.

Cell Proliferation Assay

Cell number was analyzed by measuring DNA content with the fluorescent dye Hoechst 33258 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) as described previously [28].

Luciferase-Reporter Assay

cDNAs of wild-type AR were subcloned into the MV12 retroviral vector, a vector modified from MV7 vector [29] by switching the neomycin resistant gene (neo) to hygromycin resistant gene (hph). HEK 293 cells were transduced with MV12 retrovirus expressing human wild type AR cDNA and PC-3 cells were transfected with LNCX-2 plasmid containing wild type human AR or LNCaP cells’ mutant AR cDNA. HEK 293 cells and PC-3 cells constitutively expressing wild type AR or mutant AR were generated after infection with packaged recombinant virus and hygromycin selection. HEK 293 cells were then denoted as HEK 293-AR6. 3×104 cells were seeded in each well in DMEM containing 10% CS-FBS. AR-expressing HEK 293 cells were transiently transfected with phRL-CMV renilla luciferase plasmid (normalization vector; 1 ng/well), 3× ARE Δ56-c-fos GL3 (reporter gene vector; 50 ng/well), Bluescript SKII+ (carrier; 750 ng/well) using the calcium phosphate precipitate method [30]. The 3X ARE Δ56-c-fos GL3 reporter vector was prepared by ligating three copies of an ARE duplex (5′-TCGAGTCTGGTACAGGGTGTTCTTTTG) and inserting this duplex in front of the c-fos minimal promoter (−56 to +109) in the Sma I site of the pGL3 vector (Promega, Madison, WI). After 4 hr the medium was changed and the indicated compounds were added. After an additional 48 hr, luciferase activity was measured using a Dual-Luciferase kit (Promega,) and a Monolight luminometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Western Blotting Analysis

Cells were lysed in Laemmli buffer without bromophenol blue dye. AR and PSA protein expression was determined by immunoblotting using anti-AR (AN-21) and anti-PSA (DAKO, Elostrup, Denmark) antibodies as described previously [19–24].

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (QRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated with the TRIZOL Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and contaminating DNA was removed using DNase I (DNA-free, Ambion, Austin, TX). The cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using the Omniscript RT synthesis kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). TaqMan primer/probes were designed using Primer Express (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). A QuantiTect Probe PCR kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and ABI Prism 7700 cycler (Applied Biosystems) were used in a dual-labeled probe protocol. Primers and probe used for androgen receptor (AR), prostate specific antigen (PSA), and sterol response element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c) mRNA detection were as described [24, 31, 32]. All transcript levels were normalized to human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase levels as described [24]. The 5′-end and 3′-end of the all probes was labeled with the reporter-fluorescent dye (carboxyfluorescein) and quencher dye (6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine) respectively.

Preparation of Cell Extract for Ligand Binding Assay

HEK 293-AR6 cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% CS-FBS and harvested at confluence (~107 cells per 10 cm plate) using trypsin. Cells were stored frozen at −90°C. The cell pellet was thawed on ice and homogenized using a Dounce homogenizer in Buffer A pH 7.2 containing 25 mM NaH2PO4, 1.5 mM EDTA, 2mM dithiothreitol, 10 mM NaF, 10 mM Na2MoO4, 10% glycerol, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, and 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride. The homogenate was sonicated for 1 min and then centrifuged at 8,700 × g for 15 min. Supernatant was saved and centrifuged at 27,000 × g for 30 min. Supernatant was frozen on dry ice, and stored at −90°C.

Androgen Receptor Ligand Binding Assay

Cell extracts (2.5 mg protein) were incubated on ice with 0.1 nM 3H-7α,17α-dimethyl-19-nortestosterone ([3H]DMNT), 70 Ci/mmol in 0.5 ml Buffer A with and without competitor. AR bound [3H]DMNT was measured using a hydroxylapatite-filter bounding assay [33].

Data Analysis

Data are presented as the mean plus standard deviation (SD) of at least 3 experiments or is representative of experiments repeated at least 3 times.

Results and Discussion

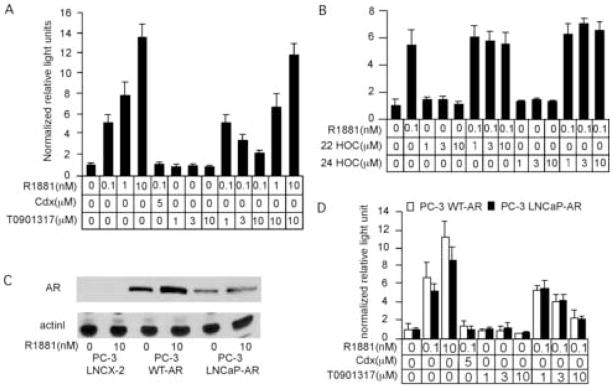

To determine the effect of T0901317 on AR signaling in LNCaP prostate cancer cells, we treated androgen-dependent LNCaP 104-S and androgen-independent LNCaP 104-R2 cells with increasing concentrations of T0901317 in the absence or presence of the synthetic androgen R1881 at 0.1 nM (Fig. 1A). T0901317 suppressed the proliferation of 104-S cells in both conditions (with or without R1881). The suppression of proliferation of 104-S cells caused by T0901317 was less when androgen was present because proliferation of 104-S cells was stimulated by 0.1 nM R1881. T0901317 also suppressed the proliferation of 104-R2 cells in the absence of R1881. Proliferation of 104-R2 cells was suppressed by 0.1 nM R1881. However, T0901317 showed a dose-dependent rescue effect against androgenic suppression on proliferation of 104-R2 cells. This was similar to the effect of antiandrogen bicalutamide on the proliferation of 104-S and 104-R2 cells, except that bicalutamide has no effect on 104-R2 cell proliferation in the absence of androgen [20]. Therefore, T0901317 appears to act both as an LXR agonist and as an antiandrogen in LNCaP sublines. Other LXR agonists 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol and 24(S)-hydroxycholesterol suppressed proliferation of 104-S and 104-R2 cells in both conditions (with or without 0.1 nM R1881) and did not rescue proliferation of 104-R2 cells from androgenic suppression (Fig. 1B and 1C). Therefore, inhibition of prostate cancer proliferation by LXR agonists is independent of AR antagonistic function of T0901317 against AR and the antiandrogenic effect of T0901317 is not being mediated through LXR signaling.

Fig 1.

The effect of LXR agonists on proliferation of androgen-dependent LNCaP 104-S cells and androgen-independent LNCaP 104-R2 cells. LNCaP 104-S and 104-R2 cells were treated with increasing concentration of T0901317 (A), 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol (22HOC) (B), or 24(S)-hydroxycholesterol (24HOC) (C) in the presence or absence of 0.1 nM R1881 for 96 hours. Relative cell number was determined using a fluorometric DNA assay described in Materials and Methods. Relative cell number of 104-S cells was normalized to cell number of 104-S cells at 0.1 nM R1881 and relative cell number of 104-R2 cells was normalized to cell number of 104-R2 cells at 0 nM R1881.

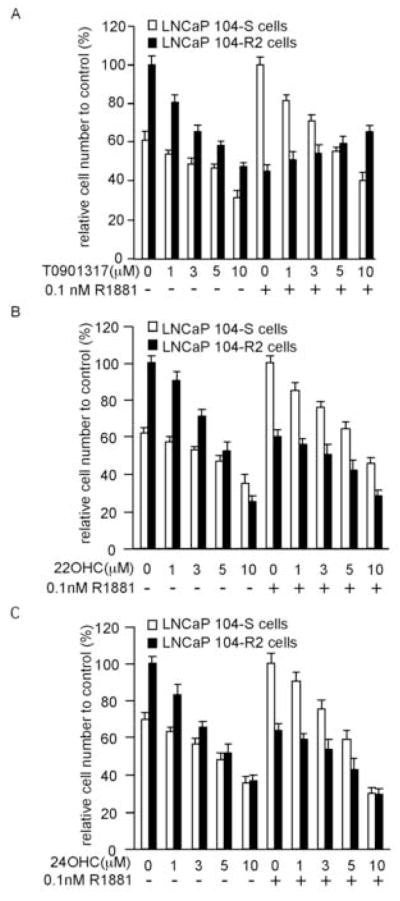

LNCaP cells express a mutant AR (T877A) that displays relaxed ligand binding specificity [34,35]. To determine whether T0901317 could affect signaling of wild-type AR, we used a luciferase reporter gene assay to determine the effect of T0901317 on androgen-induced AR transcriptional activity in human embryonic kidney HEK 293 cells expressing wild-type AR. Androgen-induced AR transcription activity was increased by R1881 and blocked by bicalutamide (Fig. 2A). T0901317 also showed a dose-dependent suppression on AR transcriptional activity induced by 0.1nM R1881. Increasing concentrations of R1881 from 0.1 nM to 10 nM rescued androgen-induced AR transcription in cells treated with 10 μM T0901317, suggesting that T0901317 may compete with androgen for binding to the AR (Fig. 2A). In contrast to T0901317, other LXR agonists 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol and 24(S)-hydroxycholesterol did not suppress AR transcription, again confirming that antiandrogen activity of T0901317 is not through LXR signaling (Fig. 2B). In PC3 cells retrovirally expressing wild-type or mutant AR (T877A) (Fig. 2C), T0901317 inhibited R1881-induced luciferase activity in both cell lines with similar effectiveness, confirming that the T877A mutation is not responsible for the effect of T0901317 on AR activity (Fig. 2D).

Fig 2.

Inhibition of androgen-induced AR transcription activity by T0901317. HEK 293 cells overexpressing AR were transiently transfected with 3X ARE-Δ56-c-fos GL3 promoter for AR transcriptional activity assay and CMV-RL renilla luciferase reporter vector for normalization. After transfection, the cells were treated with varying concentration of synthetic androgen R1881, antiandrogen bicalutamide, and T0901317 (A), 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol (B), or 24(S)-hydroxycholesterol (B) for 48 hours. Reporter gene assay was performed to determine the transcriptional activity of AR. (C) Expression of AR in PC-3 cells transduced with LNCX-2 empty vector, LNCX-2 vector encoding wild type AR, or LNCX-2 vector encoding LNCaP mutant AR was determined by Western blot analysis. Actin was used as loading control. (D) PC-3 cells overexpressing wild type or LNCaP mutant AR was transiently transfected with 3X ARE-Δ56-c-fos GL3 promoter for AR transcriptional activity assay and CMV-RL renilla luciferase reporter vector for normalization. After transfection, the PC-3 cells were treated with varying concentration of synthetic androgen R1881, antiandrogen bicalutamide, and T0901317 for 48 hours. Reporter gene assay was performed to determine the transcriptional activity of AR.

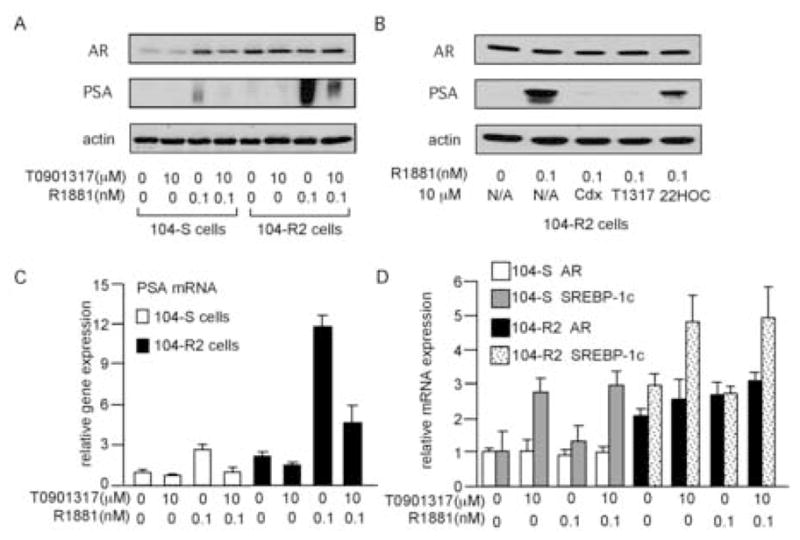

We then determined if T0901317 suppresses the expression of the endogenous androgen-regulated AR target gene PSA. T0901317 did not alter the expression level of AR protein (Fig. 3A, 3B) or mRNA (Fig. 3D), but suppressed the expression level of PSA protein (Fig. 3A, 3B) and mRNA (Fig. 3C) in both LNCaP 104-S and 104-R2 cells when 0.1 nM R1881 was present. The antiandrogen bicalutamide did not affect AR protein expression level either and suppressed PSA protein expression level (Fig. 3B). In contrast, the other LXR agonist 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol did not affect the expression level of AR and has a mild suppressive effect on PSA protein expression compared to bicalutamide and T0901317 (Fig. 3B). Since 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol does not suppress the AR transcription (Fig. 2B), it is possible that 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol may suppress PSA expression through AR-independent activation of PSA gene expression [36]. Agonistic effects of T0901317 on LXR in both LNCaP 104-S and 104-R2 cells were confirmed by T0901317-induced stimulation of the LXR target gene, sterol response element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c; Fig. 3D).

Fig 3.

Effect of T0901317 on protein and gene expression of AR, PSA, and SREBP-1c. Protein expression of AR and PSA (A,B), and mRNA expression of PSA (C), AR (D), and SREBP-1c (D) in 104-S and 104-R2 cells treated with the indicated concentration of R1881 and T0901317, bicalutamide, or 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol for 96 hours were determined by Western blotting and QRT-PCR. Actin was used as loading control. In order to demonstrate the PSA expression in 104-S cells treated with 0.1 nM R1881, the film in (A) is over-exposed compared to the film in (B). The bicalutamide, T0901317, and 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol are denoted as Cdx, T1317, and 22HOC respectively in (B). The mRNA expression of PSA (C), AR (D), and SREBP-1c (D) were normalized to the mRNA level of 104-S cells treated with 0 μM T0901317 and 0 nM R1881 respectively.

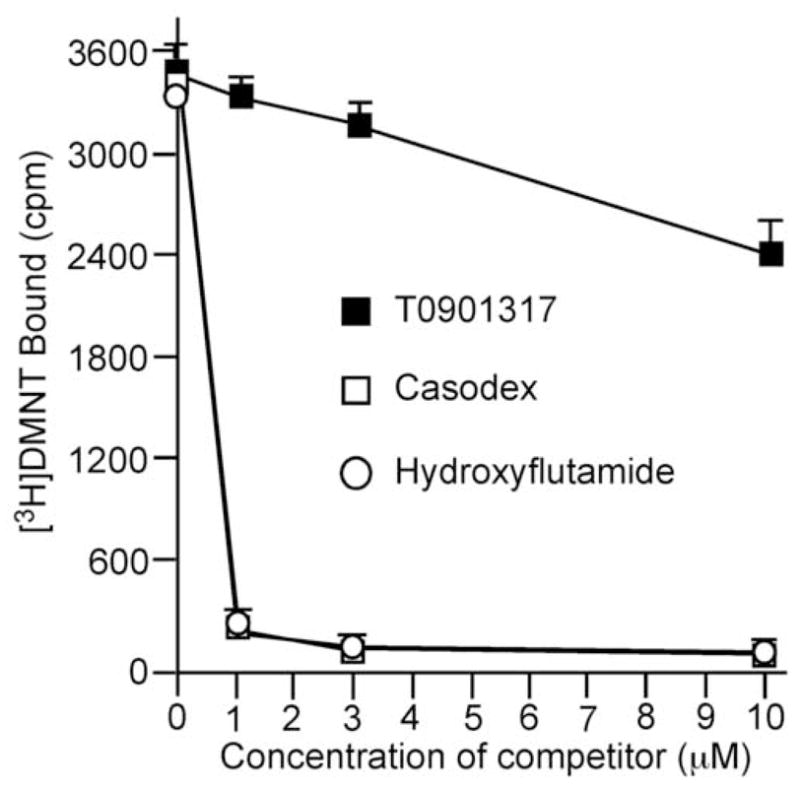

An AR ligand binding assay was then carried out to determine if T0901317 competes with androgen for AR binding. Bicalutamide and hydroxyflutamide were used as positive controls. As shown in Fig. 4, 1 μM of bicalutamide or hydroxyflutamide effectively inhibited AR binding of 0.1 nM [3H]DMNT by 95%. T0901317 reduced AR bound [3H]DMNT, indicating that T0901317 competed with androgen for AR binding. However, T0901317 was a much weaker antiandrogen compared with bicalutamide and hydroxyflutamide. T0901317 at 10 μM only reduced AR binding of 0.1 nM 3H-DMNT by 33%.

Fig 4.

Competition between T0901317 and androgen for AR binding. [3H]dimethylnortestosterone ([3H]DMNT) AR ligand binding assay was performed to determine competition between T0901317 (filled square) at indicated concentration and 0.1 nM [3H]DMNT for AR binding. Antiandrogen bicalutamide (open square) and hydroxyflutamide (open circle) were used as positive controls.

T0901317 has been reported to increase plasma and liver triglycerides in some mice models, indicating that T0901317 may not be a good candidate for a therapeutic agent [7]. In spite of its undesirable side effects, T0901317 is still a popular reagent for LXR signaling-related research. Administration of the LXR agonist T0901317 in mouse disease models was reported to be effective for treatment of atherosclerosis, diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, and cancer [9–15]. The concentration of T0901317 to exhibit these therapeutic effects in vitro range between 1–10 μM [10–15]. Our observation indicated that in this range of concentration, T0901317 acts as a weak antiandogen against AR. Since cells in several tissues or organs besides prostate also express AR, the antiandrogenic effect of T0901317 may affect observed therapeutic results if the experiments were conducted in cells expressing AR. The LXR agonist T0901317 has been reported to interact with other receptors as well. T0901317 was shown to have agonistic activity against farnesoid X receptor (FXR) [37]. T0901317 inhibited mRNA and protein expression of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) expression in hepatocytes [38]. Our results revealed that LXR agonist T0901317 acts as an antiandrogen for AR in prostate cancer cells by competing with androgen for ligand binding to AR and suppresses AR transcription. T0901317 did not affect gene or protein expression of AR. Since other LXR agonists, such as 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol and 24(S)-hydroxycholesterol, did not exhibit antiandrogenic activity, we believe that the unique non-steroidal T0901317 structure allows T0901317 to bind to AR and FXR and exhibit antagonist or agonist activity.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by US National Institute of Health grants CA58073 and AT00850, and a fund from Yen Chuang Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Song C, Kokontis JM, Hiipakka RA, Liao S. Ubiquitous receptor: a receptor that modulates gene activation by retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10809–10813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shinar DM, Endo N, Rutledge SJ, Vogel R, Rodan GA, Schmidt A. NER, a new member of the gene family encoding the human steroid hormone nuclear receptor. Gene. 1994;147:273–276. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janowski BA, Willy PJ, Devi TR, Falck JR, JR, Mangelsdorf DJ. An oxysterol signalling pathway mediated by the nuclear receptor LXR alpha. Nature. 1996;383:728–731. doi: 10.1038/383728a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forman BM, Ruan B, Chen J, Schroepfer GJ, Jr, Evans RM. The orphan nuclear receptor LXRalpha is positively and negatively regulated by distinct products of mevalonate metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10588–10593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehmann JM, Kliewer SA, Moore LB, Smith-Oliver TA, Oliver BB, Su JL, Sundseth SS, Winegar DA, Blanchard DE, Spencer TA, Willson TM. Activation of the nuclear receptor LXR by oxysterols defines a new hormone response pathway. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3137–3140. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song C, Liao S. Cholestenoic acid is a naturally occurring ligand for liver X receptor alpha. Endocrinology. 2000;141:4180–4184. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.11.7772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schultz JR, Tu H, Luk A, Repa JJ, Medina JC, Li L, Schwendner S, Wang S, Thoolen M, Mangelsdorf DJ, Lustig KD, Shan B. Role of LXRs in control of lipogenesis. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2831–2838. doi: 10.1101/gad.850400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins JL, Fivush AM, Watson MA, Galardi CM, Lewis MC, Moore LB, Parks DJ, Wilson JG, Tippin TK, Binz JG, Plunket KD, Morgan DG, Beaudet EJ, Whitney KD, Kliewer SA, Willson TM. Identification of a nonsteroidal liver X receptor agonist through parallel array synthesis of tertiary amines. J Med Chem. 2002;45:1963–1966. doi: 10.1021/jm0255116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao G, Liang Y, Broderick CL, Oldham BA, Beyer TP, Schmidt RJ, Zhang Y, Stayrook KR, Suen C, Otto KA, Miller AR, Dai J, Foxworthy P, Gao H, Ryan TP, Jiang XC, Burris TP, Eacho PI, Etgen GJ. Antidiabetic action of a liver x receptor agonist mediated by inhibition of hepatic gluconeogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1131–1136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210208200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terasaka N, Hiroshima A, Koieyama T, Ubukata N, Morikawa Y, Nakai D, Inaba T. T0901317, a synthetic liver X receptor ligand, inhibits development of atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient mice. FEBS Lett. 2003;536:6–11. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03578-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blaschke F, Leppanen O, Takata Y, Caglayan E, Liu J, Fishbein MC, Kappert K, Nakayama KI, Collins AR, Fleck E, Hsueh WA, Law RE, Bruemmer D. Liver X receptor agonists suppress vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and inhibit neointima formation in balloon-injured rat carotid arteries. Circ Res. 2004;95:110–123. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000150368.56660.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Efanov AM, Sewing S, Bokvist K, Gromada J. Liver X receptor activation stimulates insulin secretion via modulation of glucose and lipid metabolism in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes. 2004;53:S75–S78. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.suppl_3.s75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walcher D, Kummel A, Kehrle B, Bach H, Grub M, Durst R, Hombach V, Marx N. LXR activation reduces proinflammatory cytokine expression in human CD4-positive lymphocytes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1022–1028. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000210278.67076.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koldamova RP, Lefterov IM, Staufenbiel M, Wolfe D, Huang S, Glorioso JC, Walter M, Roth MG, Lazo JS. The liver X receptor ligand T0901317 decreases amyloid beta production in vitro and in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4079–4088. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411420200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukuchi J, Kokontis JM, Hiipakka RA, Chuu CP, Liao S. Antiproliferative effect of liver X receptor agonists on LNCaP human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7686–7689. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santos AF, Huang H, Tindall DJ. The androgen receptor: a potential target for therapy of prostate cancer. Steroids. 2004;69:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huggins C, Steven RE, Hodges CV. Studies on prostatic cancer. Arch Sug. 1941;43:209–223. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hellerstedt BA, Pienta KJ. The current state of hormonal therapy for prostate cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52:154–179. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.52.3.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kokontis J, Takakura K, Hay N, Liao S. Increased androgen receptor activity and altered c-myc expression in prostate cancer cells after long-term androgen deprivation. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1566–1573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kokontis JM, Hay N, Liao S. Progression of LNCaP prostate tumor cells during androgen deprivation: hormone-independent growth, repression of proliferation by androgen, and role for p27Kip1 in androgen-induced cell cycle arrest. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:941–953. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.7.0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kokontis JM, Hsu S, Chuu CP, Dang M, Fukuchi J, Hiipakka RA, Liao S. Role of androgen receptor in the progression of human prostate tumor cells to androgen independence and insensitivity. Prostate. 2005;65:287–298. doi: 10.1002/pros.20285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Umekita Y, Hiipakka RA, Kokontis JM, Liao S. Human prostate tumor growth in athymic mice: inhibition by androgens and stimulation by finasteride. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11802–11807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chuu CP, Hiipakka RA, Fukuchi J, Kokontis JM, Liao S. Androgen causes growth suppression and reversion of androgen-independent prostate cancer xenografts to an androgen-stimulated phenotype in athymic mice. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2082–2084. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chuu CP, Hiipakka RA, Kokontis JM, Fukuchi J, Chen RY, Liao S. Inhibition of Tumor Growth and Progression of LNCaP Prostate Cancer Cells in Athymic Mice by Androgen and Liver X Receptor Agonist. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6482–6486. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linja MJ, Savinainen KJ, Saramaki OR, Tammela TL, Vessella RL, Visakorpi T. Amplification and overexpression of androgen receptor gene in hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3550–3555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ford OH, 3rd, Gregory CW, Kim D, Smitherman AB, Mohler JL. Androgen receptor gene amplification and protein expression in recurrent prostate cancer. J Urol. 2003;170:1817–1821. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000091873.09677.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feldman BJ, Feldman D. The development of androgen-independent prostate cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:34–45. doi: 10.1038/35094009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rago R, Mitchen J, Wilding G. DNA fluorometric assay in 96-well tissue culture plates using Hoechst 33258 after cell lysis by freezing in distilled water. Anal Biochem. 1990;191:31–34. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90382-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirschmeier PT, Housey GM, Johnson MD, Perkins AS, Weinstein IB. Construction and characterization of a retroviral vector demonstrating efficient expression of cloned cDNA sequences. DNA. 1988;7:219–225. doi: 10.1089/dna.1988.7.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen CA, Okayama H. Calcium phosphate-mediated gene transfer: a highly efficient transfection system for stably transforming cells with plasmid DNA. Biotechniques. 1988;6:632–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fukuchi J, Hiipakka RA, Kokontis JM, Hsu S, Ko AL, Fitzgerald ML, Liao S. Androgenic suppression of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 expression in LNCaP human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7682–7685. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gelmini S, Tricarico C, Petrone L, Forti G, Amorosi A, Dedola GL, Serio M, Pazzagli M, Orlando C. Real-time RT-PCR for the measurement of prostate-specific antigen mRNA expression in benign hyperplasia and adenocarcinoma of prostate. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2003;41:261–265. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2003.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liao S, Witte D, Schilling K, Chang C. The use of a hydroxylapatite-filter steroid receptor assay method in the study of the modulation of androgen receptor interaction. J Steroid Biochem. 1984;20:11–17. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(84)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Veldscholte J, Ris-Stalpers C, Kuiper GG, Jenster G, Berrevoets C, Claassen E, van Rooij HC, Trapman J, Brinkmann AO, Mulder E. A mutation in the ligand binding domain of the androgen receptor of human LNCaP cells affects steroid binding characteristics and response to anti-androgens. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;173:534–540. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kokontis J, Ito K, Hiipakka RA, Liao S. Expression and function of normal and LNCaP androgen receptors in androgen-insensitive human prostatic cancer cells. Altered hormone and antihormone specificity in gene transactivation. Receptor. 1991;1:271–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yeung F, Li X, Ellett J, Trapman J, Kao C, Chung LW. Regions of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) promoter confer androgen-independent expression of PSA in prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:40846–40855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002755200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Houck KA, Borchert KM, Hepler CD, Thomas JS, Bramlett KS, Michael LF, Burris TP. T0901317 is a dual LXR/FXR agonist. Mol Genet Metab. 2004;83:184–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Y, Yan C, Wang Y, Nakagawa Y, Nerio N, Anghel A, Lutfy K, Friedman TC. Liver X receptor agonist T0901317 inhibition of glucocorticoid receptor expression in hepatocytes may contribute to the amelioration of diabetic syndrome in db/db mice. Endocrinology. 2006;147:5061–5068. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]