Abstract

Here we define the expression of ∼100 transcription factors (TFs) in progenitors and neurons of the developing mouse medial and caudal ganglionic eminences, anlage of the basal ganglia and pallial interneurons. We have begun to elucidate the transcriptional hierarchy of these genes with respect to the Dlx homeodomain genes, which are essential for differentiation of most γ-aminobutyric acidergic projection neurons of the basal ganglia. This analysis identified Dlx-dependent and Dlx-independent pathways. The Dlx-independent pathway depends in part on the function of the Mash1 basic helix-loop-helix (b-HLH) TF. These analyses define core transcriptional components that differentially specify the identity and differentiation of the globus pallidus, basal telencephalon, and pallial interneurons.

Keywords: CGE, Dlx, Mash, MGE, transcription factor

Introduction

The combination of transcription factors (TFs) that are expressed in a cell are a fundamental signature of its identity. This information is essential for understanding the transcriptional networks that are operating to control the state of the cell, whether during development or in maturity. Furthermore, understanding the transcriptional hierarchy provides useful information for engineering stem and progenitor cells to become cells of specific phenotypes. Toward elucidating the TF codes expressed in stem/progenitor and their derivatives in the developing basal ganglia and their derivatives, including cortical interneurons, we have systematically identified and characterized the expression of TFs in the prenatal mouse subpallium, defining those TFs that are expressed in stem/progenitors and those expressed in postmitotic cells. Previously, we had identified 2 major transcriptional pathways in the developing subpallium, regulated by the Dlx1&2 and Mash1 genes (Anderson, Eisenstat, et al. 1997; Anderson, Qiu, et al. 1997; Casarosa et al. 1999; Yun et al. 2002; Castro et al. 2006; Long et al. 2007, 2009). Here we evaluated the effects of null mutations of Dlx1&2, Mash1, or Dlx1&2 and Mash1 on the expression of many of these subpallial TFs. In previous publications, we focused on the TF codes and effect of the Dlx1&2 and Mash1 mutations on the developing septum, lateral ganglionic eminence (LGE), and olfactory bulb (Long et al. 2007, 2009).

Here we investigated these parameters in the medial ganglionic eminence (MGE) and caudal ganglionic eminence (CGE). The MGE is the anlage for the pallidum (globus pallidus [GP] are related pallidal cell groups), interneurons that tangentially migrate to the pallium (cortex and hippocampus), striatum (Sussel et al. 1999; Marín and Rubenstein 2001; Colombo et al. 2007; Wonders and Anderson 2006; Xu et al. 2008), and oligodendrocytes (Kessaris et al. 2006; Petryniak et al. 2007). The CGE is the anlage for distinct subtypes of pallial interneurons (Xu et al. 2004; Butt et al. 2005; Wonders and Anderson 2006; Miyoshi et al. 2007); it is currently unknown whether the CGE also produces neurons that remain in the subpallium.

Our analysis, based on gene expression array data, followed by in situ hybridization, provides a nearly comprehensive description of the TFs expressed in stem/progenitor cells and their derivatives of the embryonic day (E) 15.5 MGE and CGE in mice with different dosages of Dlx1&2 and Mash1.

Materials and Methods

RNA Preparation and Gene Expression Array Analysis

RNA was isolated from E15.5 mouse embryos using the dissected cortex, the combined LGE and MGE and their mantle, or the MGE from control (mixture of wild type and Dlx1/2+/−; ratio not known) or Dlx1/2−/− brains (Cobos et al. 2007; Long et al. 2009). RNA was purified and shipped to the National Institute of Health Neuroscience Consortium (TGEN, Phoenix, AZ; http://arrayconsortium.tgen.org/) where biotin-labeled cRNA hybridization probes were generated using the Affymetrix's GeneChip IVT Labeling Kit (Santa Clara, CA), which simultaneously performs in vitro transcription (a linear ∼20- to 60-fold amplification) and biotin labeling. The samples were hybridized to the Affymetrix Mouse Genome 430 2.0 array. TGEN uses GeneChip Operating Software (GCOS) to scan the arrays and to perform a statistical algorithm that determines the signal intensity of each gene (for details, see Cobos et al. 2007; Long et al. 2009); the hybridization results of these arrays are available at http://arrayconsortium.tgen.org and are entitled as ruben-affy-mouse-313340 (MGE project) and 2R01MH049428-11 (LGE/MGE and cortex project).

Animals

Mice were maintained in standard conditions with food and water ad libitum. All experimental procedures were approved by the Committee on Animal Health and Care at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Mouse colonies were maintained at UCSF in accordance with National Institutes of Health and UCSF guidelines. Mouse strains with a null allele of Dlx1&2 and Mash1 were used in this study (Anderson, Qiu, et al. 1997; Casarosa et al. 1999). These strains were maintained by backcrossing to C57BL/6J mice. For staging of embryos, midday of the “vaginal” plug was calculated as E0.5. Polymerase chain reaction genotyping was performed as described (Anderson, Qiu, et al. 1997; Casarosa et al. 1999). Because no obvious differences in the phenotypes of Dlx1&2+/+ and Dlx1&2+/− and Mash1+/+ and Mash1+/− brains have been detected, they were both used as controls.

Tissue Preparation and In Situ Hybridization

Preparation of sectioned embryos and in situ hybridization were performed using digoxigenin riboprobes on 20-μm frozen sections cut on a cryostat using methods described in Long et al. (2007).

Results

Identification of TFs Expressed in Cells of the Embryonic Mouse MGE and CGE

To understand mechanisms that regulate patterning and differentiation of the mouse embryonic basal ganglia and its derivatives, such as the striatum, GP, and telencephalic interneurons, we have attempted to identify most of the TFs that have key roles in regulating its development at E15.5. We used gene expression array analysis of RNA prepared from E15.5 mouse basal ganglia (LGE, MGE, and CGE combined), MGE, and neocortex, followed by informatic methods to identify known TFs. We then compared the expression of the basal ganglia versus the cortex, control versus Dlx1&2−/− basal ganglia, and control versus Dlx1&2−/− MGE; this is an extension of the analysis of the LGE and septum that we recently reported (Long et al. 2009).

Table 1 lists TFs that are expressed in the E15.5 basal ganglia, providing expression levels in the basal ganglia, MGE, and cortex. We have eliminated TFs whose expression was below the level of 30 units (we usually cannot detect expression by in situ hybridization of most genes below this level) and general transcriptional components. In this paper, we have focused on TFs expressed in the MGE and CGE. We do not have array results for the CGE; however, as it is composed of both LGE and MGE parts (Flames et al. 2007), we believe that the basal ganglia sample approximates the CGE, although it is probably biased toward the dorsal CGE (dCGE) (also see Supplementary Table 1 for LGE/dCGE differences). Flames et al. (2007) proposed subdivisions of the LGE, MGE, CGE, and preoptic area (POA)—these were based on analysis at E11.5 and E13.5; those subdivisions are more difficult to discern at E15.5, so herein we have not used this nomenclature.

Table 1.

List of TFs expressed in the E15.5 basal ganglia (BG) and identified gene expression array analysis (not including general TFs)

| E12 ISH | E15 ISH | TF name | BG/cortex | Ctx expression | BG expression | BG expression−/− | MGE expression | MGE expression−/− |

| TFs | ||||||||

| * | Arx | 4.64 | 487 | 2262 | 618 | 3648 | 948 | |

| Asb2 | 3.18 | 11 | 35 | 32 | 11 | 14 | ||

| Asb4 | 4.81 | 16 | 77 | 125 | 419 | 992 | ||

| * | ATBF1 | 30.44 | 18 | 548 | 503 | 124 | 246 | |

| * | BF1 (FoxG1) | 0.75 | 5121 | 3856 | 3116 | 4142 | 4781 | |

| Bhlhb5 | 0.32 | 3822 | 1219 | 1053 | 28 | 189 | ||

| * | Brn2 (POU3F2) | 0.56 | 149 | 83 | 93 | 89 | 86 | |

| * | Brn4 (POU3F4) | 7.18 | 28 | 201 | 114 | 501 | 209 | |

| * | Brn5 (POU6F1) | 0.16 | 19 | 3 | 10 | 1 | 6 | |

| * | CoupTF1 (NR2F1) | 1.31 | 2414 | 3154 | 3561 | 1479 | 3857 | |

| CoupTFII (NR2F2) | 3.38 | 102 | 345 | 339 | 73 | 110 | ||

| * | Ctip1 (Bcl11a, Evi9) | 1.06 | 1522 | 1616 | 1052 | 891 | 692 | |

| * | Ctip2 (Bcl11b, Rit-1b) | 1.43 | 1106 | 1579 | 792 | 1441 | 1748 | |

| * | Cux2 | * | ||||||

| Dach2 | 2.79 | 33 | 92 | 171 | 153 | 277 | ||

| * | Dbx1 | 1.83 | 18 | 33 | 27 | 17 | 28 | |

| * | Dlx1 | 9.84 | 120 | 1181 | 7 | 3278 | 2 | |

| * | * | Dlx2 | 7.06 | 50 | 353 | 15 | 1069 | 15 |

| * | Dlx5 | 7.76 | 96 | 745 | 80 | 751 | 49 | |

| * | Dlx6 | 9.80 | 15 | 147 | 21 | 172 | 5 | |

| * | Dlx6 antisense (Evf1, Evf2) | 4.00 | 11 | 44 | 4 | 22 | 2 | |

| * | Dlxin | * | ||||||

| * | Ebf1 | 21.33 | 27 | 576 | 132 | 144 | 96 | |

| Ebf2 | 1.59 | 17 | 27 | 42 | 17 | 29 | ||

| * | * | Ebf3 | 0.66 | 74 | 49 | 198 | 12 | 50 |

| * | Egr3 | 2.05 | 21 | 43 | 18 | 45 | 25 | |

| * | Emx1 | 0.31 | 323 | 100 | 75 | 33 | 4 | |

| * | Emx2 | 0.43 | 356 | 152 | 177 | 105 | 94 | |

| * | * | ER81 (Etv1) | 3.23 | 66 | 213 | 137 | 820 | 283 |

| * | ESRG (ESRRG, NR3B3) | 1.57 | 21 | 33 | 26 | 20 | 25 | |

| * | Evi3 (Zfp521, EHZF) | * | ||||||

| Fah | 3.55 | 22 | 78 | 42 | 59 | 36 | ||

| * | Fez (FezF1) | * | ||||||

| * | Fez-l (FezF2) | * | ||||||

| * | FoxO3a | 0.75 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 17 | 19 | |

| * | FoxO4 | 0.46 | 13 | 6 | 36 | 17 | 23 | |

| * | FoxP1 | 2.60 | 149 | 388 | 122 | 96 | 81 | |

| * | FoxP2 | 2.53 | 34 | 86 | 90 | 31 | 14 | |

| * | FoxP4 (mFKHLA) | 1.30 | 43 | 56 | 43 | 30 | 38 | |

| * | FXR1alpha1 (NR1H4) | 2.10 | 10 | 21 | 14 | 30 | 21 | |

| * | * | Gbx1 | * | |||||

| * | Gbx2 | 5.33 | 9 | 48 | 63 | 15 | 124 | |

| * | Gli1 (Zfp5) | * | ||||||

| * | * | Gsh1 | 7.57 | 7 | 53 | 156 | 112 | 484 |

| * | Gsh2 | 14.77 | 13 | 192 | 205 | 185 | 308 | |

| * | Hes1 | 0.64 | 171 | 110 | 88 | 131 | 93 | |

| * | * | Hes5 | 1.36 | 167 | 227 | 290 | 702 | 689 |

| * | HesR1 (Hey1) | 1.10 | 106 | 117 | 144 | 137 | 107 | |

| Hlx1 | 3.00 | 11 | 33 | 27 | 2 | 11 | ||

| * | * | Id2 | 0.12 | 1870 | 230 | 686 | 122 | 729 |

| * | Id4 | 0.98 | 197 | 194 | 196 | 214 | 294 | |

| * | Ikaros (ZNFN1A1) | 2.27 | 11 | 25 | 25 | 36 | 31 | |

| * | Islet1 | 254.00 | 6 | 1524 | 1318 | 1339 | 2264 | |

| Klf4 | 1.33 | 36 | 48 | 45 | 54 | 88 | ||

| Klf5 | 7.14 | 21 | 150 | 92 | 62 | 298 | ||

| * | Lhx1 (Lim1) | 0.36 | 14 | 5 | 22 | 8 | 15 | |

| * | Lhx2 | 0.31 | 2120 | 650 | 774 | 428 | 853 | |

| * | * | Lhx6 | 2.67 | 46 | 123 | 98 | 130 | 167 |

| * | Lhx7 | 252.50 | 2 | 505 | 224 | 1513 | 166 | |

| Lhx9 | 0.68 | 200 | 135 | 200 | 4 | 123 | ||

| * | Lmo1 | 0.62 | 569 | 351 | 362 | 1764 | 1048 | |

| * | Lmo3 (Rbtn3) | * | ||||||

| * | Lmo4 | 2.19 | 360 | 789 | 581 | 697 | 761 | |

| * | Maf A | * | ||||||

| * | Maf B | 1.07 | 122 | 131 | 167 | 53 | 72 | |

| * | Maf C | 1.04 | 28 | 29 | 20 | 18 | 3 | |

| * | Mash1 (Ascl1) | 4.51 | 63 | 284 | 330 | 536 | 941 | |

| Med6 | 6.03 | 64 | 386 | 229 | 344 | 275 | ||

| * | Mef2c | 0.44 | 398 | 174 | 151 | 48 | 26 | |

| * | Meis1 | 4.67 | 49 | 229 | 154 | 115 | 142 | |

| * | Meis2 (MRG1B) | 1.23 | 1489 | 1827 | 1275 | 1067 | 1078 | |

| Msc (MyoR) | 3.21 | 14 | 45 | 49 | 2 | 4 | ||

| Myt1l | 0.74 | 1018 | 757 | 933 | 276 | 566 | ||

| Neurog2 | 0.23 | 1508 | 341 | 211 | 9 | 66 | ||

| * | Nex1 (NeuroD6) | 0.12 | 5163 | 620 | 881 | 1 | 78 | |

| * | NHLH2 (Hen2, NSCL2) | * | ||||||

| * | Nkx2.1 (Ttf1) | 0.46 | 65 | 30 | 47 | 31 | 24 | |

| * | Nkx2.2 | 7.00 | 3 | 21 | 30 | 1 | 20 | |

| * | Nkx5.1 (Hmx1) | 1.67 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 2 | |

| Nkx5.2 | * | |||||||

| * | Nkx6.1 | 15.00 | 1 | 15 | 8 | 14 | 16 | |

| * | Nkx6.2 | 1.24 | 100 | 124 | 112 | 76 | 74 | |

| * | Nolz1 (Zfp503) | * | ||||||

| * | Npas1 | 0.50 | 12 | 6 | 2 | 16 | 5 | |

| Nr4a2 | 0.72 | 132 | 95 | 114 | 37 | 50 | ||

| * | Nur77 (NR4A1) | 1.18 | 65 | 77 | 51 | 36 | 26 | |

| * | * | Oct6 (POU3F1) | 1.30 | 74 | 96 | 25 | 76 | 62 |

| Olig1 | 5.73 | 79 | 453 | 638 | 318 | 896 | ||

| * | Olig2 | 5.66 | 29 | 164 | 281 | 654 | 859 | |

| * | * | Otp | 0.88 | 8 | 7 | 16 | 9 | 15 |

| * | Otx1 | 0.31 | 129 | 40 | 53 | 2 | 22 | |

| * | * | Otx2 | 0.46 | 76 | 35 | 71 | 151 | 359 |

| * | Pak3 | 1.33 | 179 | 238 | 526 | 230 | 395 | |

| * | Pax6 | 0.42 | 200 | 83 | 103 | 27 | 16 | |

| * | * | Pbx1 | 1.03 | 180 | 186 | 126 | 191 | 137 |

| * | Pbx3 | 7.28 | 76 | 553 | 671 | 209 | 700 | |

| * | Peg3 (End4, Gcap4, Pw1, Zfp102) | 1.22 | 381 | 463 | 818 | 512 | 568 | |

| * | Phox2a (Arix, Pmx2) | 0.73 | 22 | 16 | 22 | 4 | 10 | |

| * | Prox1 | 3.07 | 14 | 43 | 56 | 34 | 94 | |

| * | RALDH3 (ALDH6) | * | ||||||

| * | RARß | 14.26 | 19 | 271 | 40 | 56 | 28 | |

| * | RORb | 0.70 | 60 | 42 | 83 | 31 | 39 | |

| * | RXRg (NR2B3) | 21.29 | 14 | 298 | 48 | 57 | 26 | |

| * | * | Sall3 (msal1, spalt) | 0.84 | 68 | 57 | 145 | 90 | 171 |

| * | Sim1 | 1.19 | 37 | 44 | 44 | 35 | 38 | |

| * | Six3 | 9.70 | 33 | 320 | 153 | 188 | 253 | |

| Solt | 1.09 | 238 | 260 | 200 | 759 | 340 | ||

| * | Sox1 | 3.60 | 15 | 54 | 35 | 105 | 140 | |

| * | Sox11 | 0.77 | 6142 | 4716 | 3765 | 5005 | 3203 | |

| * | Sox4 | 0.73 | 827 | 602 | 865 | 507 | 1046 | |

| Sox5 | 0.17 | 1023 | 172 | 223 | 243 | 347 | ||

| Sox6 | 1.14 | 258 | 294 | 406 | 711 | 836 | ||

| Sox8 | 4.24 | 29 | 123 | 85 | 63 | 96 | ||

| * | * | Sp8 (Btd) | 2.41 | 63 | 152 | 81 | 44 | 6 |

| * | Sp9 | * | ||||||

| * | Tbr1 | 0.33 | 646 | 215 | 270 | 29 | 5 | |

| * | Tbr2 | 0.16 | 1030 | 169 | 111 | 2 | 1 | |

| * | TCF4 | 0.30 | 2771 | 818 | 1245 | 2066 | 2272 | |

| * | Tle4 | * | ||||||

| * | Tlx | 1.44 | 16 | 23 | 18 | 9 | 4 | |

| Tox | 0.86 | 182 | 156 | 257 | 215 | 532 | ||

| Trp53 | 0.82 | 124 | 102 | 80 | 109 | 120 | ||

| * | Trp53bp1 | 0.66 | 212 | 140 | 153 | 127 | 91 | |

| * | Tshz1 | * | ||||||

| * | Tshz2 | * | ||||||

| * | * | Vax1 | 2.69 | 13 | 35 | 22 | 31 | 17 |

| Zbtb20 | 0.76 | 507 | 385 | 746 | 139 | 359 | ||

| Zfhx1b | 0.31 | 1037 | 321 | 388 | 310 | 140 | ||

| * | Zfp618 | * | ||||||

| * | Zic1 | 1.45 | 593 | 859 | 1592 | 613 | 604 | |

| Non-TFs | ||||||||

| * | Adamts5 | 1.39 | 31 | 43 | 28 | 133 | 31 | |

| Adrenergic receptor, alpha 2a | 7.38 | 13 | 96 | 102 | 41 | 50 | ||

| Ankyrin repeat and SOCS box–containing protein 4 | 7.13 | 15 | 107 | 152 | 784 | 1425 | ||

| B3galt5 | 12.00 | 5 | 60 | 29 | 94 | 72 | ||

| Bcl11b | 1.43 | 1106 | 1579 | 792 | 1441 | 1748 | ||

| Bdkrb1 | 1.69 | 16 | 27 | 10 | 17 | 21 | ||

| Cad7, type 2 | 0.44 | 55 | 24 | 159 | 29 | 38 | ||

| * | Cad8 | * | ||||||

| Calb1 | 9.41 | 34 | 320 | 177 | 236 | 174 | ||

| Calcr | 3.20 | 5 | 16 | 91 | 42 | 88 | ||

| Camk2a | 10.26 | 23 | 236 | 122 | 50 | 136 | ||

| Cap1 | 1.13 | 460 | 518 | 309 | 222 | 369 | ||

| Carnitine deficiency–associated gene expressed in ventricle 3 | 0.14 | 63 | 9 | 60 | 3 | 15 | ||

| * | Ccr4 | 0.23 | 22 | 5 | 23 | 3 | 3 | |

| Cd69 | 1.63 | 8 | 13 | 4 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Cfh | 2.00 | 10 | 20 | 11 | 13 | 5 | ||

| Clca1 | 1.60 | 5 | 8 | 39 | 24 | 35 | ||

| Clca2 | 1.50 | 10 | 15 | 31 | 4 | 18 | ||

| Coatomer protein complex, subunit gamma 2, antisense 2 | 4.23 | 242 | 1024 | 1680 | 74 | 363 | ||

| Cobl | 9.40 | 10 | 94 | 87 | 24 | 25 | ||

| * | Crabp1 | 6.88 | 68 | 468 | 116 | 113 | 12 | |

| * | Crym | 0.35 | 329 | 114 | 41 | 18 | 33 | |

| * | CXCR4 | 0.88 | 307 | 271 | 81 | 415 | 211 | |

| * | CXCR7 | 3.96 | 408 | 1614 | 708 | 4602 | 1651 | |

| * | CyclinD2 | 1.18 | 1802 | 2126 | 1631 | 3051 | 1700 | |

| * | Dact1 | * | ||||||

| Dlc1 | 1.79 | 78 | 140 | 73 | 45 | 40 | ||

| * | Drd1a | 1.32 | 31 | 41 | 17 | 5 | 4 | |

| Egfl6 | 0.29 | 21 | 6 | 21 | 13 | 15 | ||

| Erbb2ip | 0.42 | 95 | 40 | 150 | 73 | 47 | ||

| * | ErbB4 | 4.67 | 3 | 14 | 7 | 12 | 2 | |

| Gabra1 | 9.57 | 7 | 67 | 94 | 18 | 40 | ||

| * | GAD1 (GAD67) | 5.46 | 321 | 1753 | 1358 | 583 | 520 | |

| GABA-A receptor, subunit gamma 1 | 6.11 | 9 | 55 | 78 | 18 | 12 | ||

| Gcnt2 | 1.90 | 50 | 95 | 42 | 70 | 58 | ||

| Gng4 | 5.00 | 15 | 75 | 77 | 14 | 39 | ||

| Gpr88 | 110.50 | 2 | 221 | 50 | 23 | 18 | ||

| Granulin | 1.35 | 287 | 388 | 194 | 360 | 402 | ||

| Gucy1a3 | 2.62 | 188 | 492 | 179 | 655 | 174 | ||

| H2-K | 2.77 | 13 | 36 | 12 | 2 | 13 | ||

| H2-Q1 | 1.96 | 26 | 51 | 17 | 32 | 18 | ||

| Hist1h1c | 1.99 | 139 | 277 | 128 | 473 | 288 | ||

| Htr3a | 2.07 | 92 | 190 | 62 | 223 | 113 | ||

| Ivd | 0.87 | 229 | 199 | 96 | 144 | 183 | ||

| Kcnj9 | 10.67 | 3 | 32 | 24 | 9 | 1 | ||

| Kruppel-like factor 5 | 7.14 | 21 | 150 | 92 | 62 | 298 | ||

| Lck | 2.80 | 10 | 28 | 15 | 10 | 19 | ||

| Lgals1 | 1.96 | 266 | 522 | 274 | 1212 | 589 | ||

| Lor | 13.50 | 2 | 27 | 35 | 10 | 16 | ||

| Mbp | 2.10 | 70 | 147 | 105 | 115 | 119 | ||

| Moxd1 | 6.60 | 5 | 33 | 25 | 7 | 16 | ||

| Myh6 | 13.08 | 13 | 170 | 89 | 59 | 95 | ||

| Ncdn | 1.89 | 323 | 610 | 309 | 269 | 390 | ||

| * | NP2 | 1.18 | 150 | 177 | 248 | 17 | 57 | |

| * | Nphx | * | ||||||

| Npy2r | 7.75 | 4 | 31 | 30 | 36 | 26 | ||

| Olfm3 | 32.00 | 4 | 128 | 159 | 78 | 63 | ||

| Omg | 12.25 | 4 | 49 | 65 | 37 | 91 | ||

| Ostb | 9.33 | 3 | 28 | 18 | 23 | 5 | ||

| * | Penk1 | 13.31 | 13 | 173 | 79 | 39 | 34 | |

| Phka1 | 0.44 | 36 | 16 | 38 | 32 | 17 | ||

| * | PK2 | * | ||||||

| * | PKR1 | * | ||||||

| Pla2g4b | 0.93 | 126 | 117 | 52 | 121 | 124 | ||

| Plaa | 0.48 | 33 | 16 | 78 | 21 | 25 | ||

| Pre B-cell leukemia TF 3 | 15.65 | 122 | 1909 | 2013 | 696 | 2110 | ||

| Presenilin 1 | 0.50 | 10 | 5 | 11 | 9 | 7 | ||

| Prok2 | 11.80 | 5 | 59 | 63 | 27 | 108 | ||

| Protease, cysteine, 2 (NEDD8 specific) | 0.33 | 69 | 23 | 86 | 118 | 82 | ||

| Purg | 1.61 | 57 | 92 | 48 | 52 | 58 | ||

| Pyruvate carboxylase | 1.34 | 41 | 55 | 17 | 10 | 17 | ||

| Rbp1 | 9.70 | 213 | 2066 | 889 | 2917 | 1452 | ||

| Resp18 | 129.50 | 2 | 259 | 245 | 33 | 61 | ||

| Rnasep1 | 1.61 | 62 | 100 | 43 | 107 | 106 | ||

| * | Robo2 | * | ||||||

| Rpl22 | 1.70 | 2909 | 4952 | 2182 | 7650 | 5885 | ||

| Rrbp1 | 1.08 | 37 | 40 | 7 | 18 | 21 | ||

| Rrp4 | 2.14 | 14 | 30 | 15 | 13 | 11 | ||

| S100 calcium-binding protein A10 (calpactin) | 2.04 | 103 | 210 | 103 | 520 | 189 | ||

| Scmh1 | 0.35 | 98 | 34 | 212 | 43 | 33 | ||

| * | Sema3a | 0.93 | 195 | 181 | 185 | 59 | 76 | |

| Sema6d | 0.61 | 33 | 20 | 84 | 38 | 26 | ||

| * | Shb | 1.31 | 274 | 358 | 178 | 410 | 213 | |

| Slco1a1 | 2.36 | 11 | 26 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| Snx6 | 1.46 | 174 | 254 | 129 | 258 | 110 | ||

| Spp1 | 4.84 | 31 | 150 | 57 | 32 | 17 | ||

| Syndecan 1 | 1.75 | 193 | 338 | 160 | 470 | 301 | ||

| Syt6 | 1.73 | 48 | 83 | 41 | 54 | 21 | ||

| Tac1 | 86.55 | 11 | 952 | 457 | 310 | 174 | ||

| * | Thbs1 | 0.87 | 204 | 178 | 69 | 166 | 86 | |

| * | Tiam2 | 0.27 | 895 | 239 | 55 | 438 | 42 | |

| Top2b | 13.95 | 19 | 265 | 44 | 56 | 19 | ||

| Trhr | 0.40 | 45 | 18 | 28 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Uty | 0.77 | 135 | 104 | 7 | 45 | 80 | ||

| V1ra5 | 0.50 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 9 | ||

| * | Viaat | 10.76 | 42 | 452 | 38 | 617 | 24 | |

| Vsnl1 | 7.82 | 28 | 219 | 255 | 54 | 133 | ||

| Wnt5a | 0.83 | 82 | 68 | 38 | 110 | 87 | ||

| Wnt7a | 2.01 | 160 | 321 | 158 | 513 | 441 | ||

| Zfp145; PLZF | 2.10 | 31 | 65 | 29 | 2 | 2 | ||

Note: Asterisks in columns 1 and 2 indicate if the results were verified by in situ hybridization. Columns to the right indicate the raw hybridization scores for the individual genes for hybridization using RNA isolated from control E15.5 cortex, combined LGE, MGE, and CGE (BG), MGE, or from Dlx1&2−/− BG (for details, see Long et al. 2009) or Dlx1&2−/− MGE (for details, see Cobos et al. 2007). ISH, in situ hybridization.

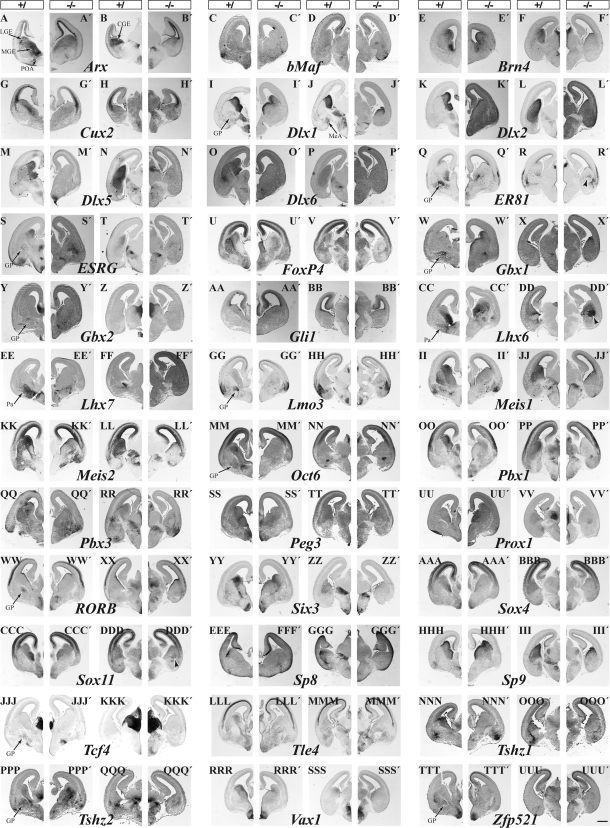

To evaluate the array results, we used in situ hybridization on coronal sections of E15.5 forebrain as indicated by asterisks in Table 1 (Figs 1 and 2; Supplementary Figs 1, 2, and 3). These results largely confirm the TF expression in the subpallium and allowed us to identify TFs that are expressed in progenitor zone (ventricular zone [VZ] and subventricular zone [SVZ]) and mantle zone (MZ) of the LGE, MGE, and CGE. For example, this analysis identifies several TFs that are expressed in the GP (Arx, Dlx1, ER81 (Etv1), Gbx1, Lhx6, Lhx7(8), Oct6 (POU3F1), ROR-beta, TCF4, Tshz2, and Zfp521 (Evi30)) (Figs 1 and 2). It also enabled us to evaluate differential expression between the LGE, MGE, and CGE.

Figure 1.

TFs whose expression is reduced in either the LGE/MGE (left pair) or CGE (right pair) in the Dlx1&2−/− mutants as shown by in situ hybridization on coronal hemisections from E15.5 forebrains. Control: left section; Dlx1&2−/−: right section. Magnification bar: 500 μm.

Figure 2.

TFs whose expression is increased in either the LGE/MGE (left pair) or CGE (right pair) in the Dlx1&2−/− mutants as shown by in situ hybridization on coronal hemisections from E15.5 forebrains. Control: left section; Dlx1&2−/−: right section. Magnification bar: 500 μm.

TFs that are specifically expressed in progenitor cells of MGE are Lhx6, Lhx7(8), Nkx2.1; those preferentially expressed in the MGE (compared with the LGE) include ER81 (Etv1), Sox4, and Sox11 (also see Flames et al. 2007). TFs that are expressed in progenitor cells of the LGE and not detected in the MGE by this assay include ESRG, FoxP1, FoxP2, FoxP4, Sp8; TFs preferentially expressed in the LGE (compared with the MGE) include ATBF1 (Zfhx3), COUP-TF1 (NR2F1), CTIP2 (Bcl11b), Ebf1, Islet1, Meis1, Meis2, Oct6 (POU3F1), Pbx1, Pbx3, Six3, and TCF4. Of note, the MGE expression of many of these genes is within a narrow corridor between SVZ and mantle and may correspond to the ventral migration of LGE cells (López-Bendito et al. 2006).

The CGE contains at least 2 subdivisions; the ventral part is a caudal extension of the MGE and the dorsal part is a caudal extension of the LGE (Flames et al. 2007). However, whereas the LGE is largely dedicated to generating projection neurons of the striatum, accumbens, olfactory tubercle, and interneurons of the olfactory bulb (Long et al. 2007, 2009), the dCGE is known to generate interneurons of the neocortex and hippocampus (Xu et al. 2004; Butt et al. 2005; Miyoshi et al. 2007). Thus, there must be molecular differences in the progenitors of the LGE and CGE. Therefore, we qualitatively compared TF expression in the VZ/SVZ of these regions using in situ hybridization (Figs 1 and 2). Supplementary Table 1 summarizes our nonquantitative conclusions. We found TFs that are preferentially expressed in the LGE (green color, i.e., ATBF1 [Zfhx3] and Islet1), equally expressed in the LGE and dCGE (yellow color, i.e., Dlx genes), and preferentially expressed in the dCGE (red color, i.e., Arx, COUP-TFI (NR2F1), Mash1, Prox1, Sall3, Sox1, Sox4, and Sp9).

Below we describe how loss of either Dlx1&2 or Mash1 function affects the expression of many of these TFs and selected non-TFs. The analysis was performed using in situ hybridization on E15.5 coronal sections; in general, the gene expression array results (Table 1) were in accord with the histological analysis. Analysis at E12.5 was also performed in the Dlx1&2−/− mutants for selected genes (column 1 in Table 1) and showed similar results (data not shown) (for the LGE and septum, see Long et al. 2009).

Dlx1&2 Functions in the MGE

Dlx1&2 are required, to varying degrees, to promote expression of several TFs in MGE progenitors (VZ and SVZ), including Arx, bMaf, Brn4, Cux2, Dlx1, Dlx2, Dlx5, Dlx6, ER81 (Etv1), Gli1, Lhx6, Lhx7, Pbx1, Peg3, Sox4, Sox11, and Vax1 (Fig. 1), and non-TFs, including CXCR4, CXCR7 (RDC1), CyclinD2, GAD67, Gucy1a3, Shb, Tiam2, and Thbs (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Dlx1&2 repress the expression of a set of TFs, including antisense-Dlx6, COUP-TF1, Ctip2, Gbx1, Gsh1, Gsh2, Id2, Id4, Ikaros, Islet1, Lhx2, Mash1, Nkx2.1, Olig2, Otp, Prox1, Sall3, Six3, and Sox1 (Fig. 2), and non-TFs, including Dact1 and PKR1 (Supplementary Fig. 1). Some TFs do not show a discernable expression change, such as Sp9 (Fig. 1HHH–III′). The MGE produces several types of cells including projection neurons of the GP and interneurons that migrate to the cortex and hippocampus. Dlx1&2−/− mutants produce a small GP but with reduced numbers of neurons expressing ER81 (Etv1), Gbx1, Gbx2, Lhx6, Lhx7/8, Lmo3, Meis1, Oct6 (POU3F1), Pbx3, RORβ, Tcf4, Sema3a, Tshz2, and Zpf521 (Fig. 1) and non-TFs Cad8, Gad67 (Gad1), Robo2, and Sema3a (Supplementary Fig. 1). On the other hand, some TFs show increased expression in the MGE mantle zone including ATBF1, Ebf1, ESRG, Fez, FoxP2, Islet1, and Pbx3 (Fig. 2); this may be due to ectopic accumulation of cells from striatal and/or POA migrations (López-Bendito et al. 2006) or ectopic expression of these TFs in the pallidal MZ.

Most interneuron precursors fail to migrate into the cortex in Dlx1&2−/− mutants (Anderson, Eisenstat, et al. 1997; Pleasure et al. 2000; Cobos et al. 2005) and appear to remain as ectopia in the basal ganglia, some of which express neuropilin 2 (NP2) (Marín et al. 2001). Here we show that these ectopia to form in a caudal position within the CGE and continue to express many TF and non-TF markers characteristic of immature interneurons, including bMaf, ErbB4, Lhx6, NP2, and neurexophilin-1 (Nphx) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Surprisingly, there are also large ectopia that express GP markers: ER81 (Etv1) and Nkx2.1 (Ttf1) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Finally, there are ectopia expressing other genes (Pbx1, Prox1, and Sox11) that currently are not known to mark specific cell types (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Dlx1&2 Functions in the CGE

Dlx1&2 are required to promote expression of several TFs in the CGE including Arx, Brn4, Dlx1,2,5,6, ESRG, FoxP1, FoxP4, Meis1, Meis2, Oct6 (POU3F1), Pbx1, Pbx3, Prox1, Six3, Sox4, Sox11, Sp8, Tle4, Tshz1, and Vax1 and non-TFs including CXCR4, CXCR7 (RDC1), ErbB4, Gad67 (Gad1), Gucy1a3, Robo2, Shb, Tiam2, and Thbs. The reduction of some genes probably corresponds to the block of MGE-derived interneuron tangential migration (i.e., bMaf, Cux2, Lhx6; Fig. 1C–D′,G–H′,CC–DD′).

Dlx1&2 repress the expression of several TFs including antisense-Dlx6, COUP-TFI (NR2F1), Ctip2 (Bcl11b), Gbx1, Gsh1, Gsh2, Id2, Ikaros, Islet1, Lmo1, Mash1, Olig2, Otp, and Sall3 and several non-TFs including Dact1 and PKR1 (Fig. 2). Several genes show little change in expression including FoxP2, Hes5, Id4, Lhx2, Otx2, Pax6, Sox1, and Sp9 (Figs 1 and 2); this is unlike the LGE, which has increased Hes5, Lhx2, and Sp9 expression (Figs 1 and 2; Supplementary Table 2; Anderson, Qiu, et al. 1997; Yun et al. 2002; Long et al. 2007, 2009).

Finally, as noted above, there are ectopic accumulations of cells in the CGE expressing several markers characteristic of the GP or cortical interneurons (i.e., bMaf, ER81 (Etv1), ErbB4, Lhx6, Nkx2.1 (Ttf1), NP2, Nphx, Pbx1, Prox1, and Sox11; Supplementary Fig. 2).

Dlx1&2−/−;Mash1−/− Compound Mutants Define Genes Epistatic to Dlx1&2, Mash1, or Both Dlx1&2 and Mash1

Whereas many aspects of MGE and CGE differentiation are lost in the Dlx1&2−/− mutants, many aspects are maintained (Figs 1 and 2; Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2). The maintained characteristics may be regulated by TFs whose expression persists in mutant LGE progenitors (Fig. 2) (Long et al. 2009). A good candidate of this type of TF is Mash1, due to its overexpression in the Dlx1&2−/− mutants (Fig. 2) (Yun et al. 2002; Long et al. 2009). As MASH1 and DLX2 proteins are coexpressed in progenitors of the dorsal LGE (dLGE) (Porteus et al. 1994; Yun et al. 2002), they have the potential to regulate the developmental programs of these cells in parallel and/or in series. Here, we explored the hypothesis that Mash1 has a critical role in maintaining certain aspects of MGE and CGE differentiation in the Dlx1&2−/− mutants, as it does in the LGE (Long et al. 2009).

We studied the expression of TFs and selected other genes in the MGE and CGE in Dlx1&2−/−, Mash1−/−, and Dlx1&2−/−;Mash1−/− mutants at E15.5, concentrating on genes whose expression persists in Dlx1&2−/− mutants (Supplementary Fig. 3). Expression of these genes fell into 4 general classes (Supplementary Table 3):

Class I genes appear to be epistatic only to Dlx1&2−/−. Expression of Class Ia genes (ER81, Gli1, Gsh1, and Sp8) is reduced or lost in the Dlx1&2−/− mutants and is not overtly affected in the Mash1−/− mutants, and the triple mutant phenocopies the Dlx1&2−/− mutant. Class Ib genes are ectopically expressed in the Dlx1&2−/− mutants and are not overtly modified by loss of Mash1−/−.

Class II genes appear to be epistatic only to Mash1−/− (i.e., Hes5CGE: i.e., in only the CGE).

Class III genes appear to be altered in both the Dlx1&2−/− and Mash1−/− mutants, and in most cases, these phenotypes are exacerbated in the triple mutants. There are 5 subtypes of Class III genes based on their differentiation responses in the Dlx1&2−/− and Mash1−/− mutants:

IIIa (ArxMGE, Dlx1, Dlx5, and Gad67CGE): decreased in Dlx1&2−/− and increased in Mash1−/−;

IIIb (ArxCGE, Meis2, Six3, Sox1, Sp9, and Vax1): decreased in both Dlx1&2−/− and Mash1−/−;

IIIc (Dact1, Hes5MGE, Olig2, and Sox1): increased in Dlx1&2−/− and decreased in Mash1−/−;

IIId (Islet I): increased in the VZ of the CGE (and LGE; but reduced in the SVZ and MZ of the LGE) and not greatly modified by Mash1 dosage; and

IIIe (Tshz2): increased in Dlx1&2−/− and ectopic in Mash1−/−.

Class IV (ER81 in the MGE) genes show a modest decrease in the number of labeled GP neurons in Dlx1&2−/−, Mash1−/−, and Dlx1&2−/−;Mash1−/− mutants.

Of note, several TFs continue to be expressed in the Dlx1&2−/−;Mash1−/− mutants, albeit generally at lower levels, in the CGE (Gsh1, Islet1, Olig2, and Sp9) and MGE (ER81, Islet1, Olig2, and Sp9) (Supplementary Fig. 3), demonstrating that some fundamental aspects of CGE and MGE specification such as GAD67 expression (Supplementary Fig. 1) are not fully dependent on Dlx and Mash1.

Discussion

We report a comprehensive analysis of the TFs, excluding general TFs, that are expressed in the developing (E15.5) mouse MGE and CGE. Although we cannot rule out that there are additional important TFs, we expect that they will be present in our gene expression array data sets (http://arrayconsortium.tgen.org) and are entitled as ruben-affy-mouse-313340 (MGE project) and 2R01MH049428-11 (LGE/MGE and cortex project). This paper complements our TF analysis in developing septum and LGE (Long et al. 2009) and the work of Flames et al. (2007), which used a subset of these TFs to define E13.5 subpallial progenitor zones. We then defined the response of many of these genes in mice lacking expression of Dlx1&2, Mash1, or Dlx1&2 and Mash1. We expect that this analysis will provide an important foundation for establishing the transcriptional circuitry that controls cell fate and differentiation of MGE and CGE derivatives. This information will be extremely useful in understanding normal pathways that control the development and evolution of the basal ganglia and pallial interneurons and will help predict the effect of mutations, whether they are in experimental animals or in humans. Furthermore, understanding the transcriptional hierarchies will be essential in engineering stem cells.

TF Profile in the VZ and SVZ of the dCGE

Flames et al. (2007) demonstrated that the CGE is a composite of the caudal LGE (the dCGE) and MGE (the ventral part). Here we show that although the dCGE does share many properties with the LGE, there are several important differences (Supplementary Table 1). We find TFs that are preferentially expressed in the LGE (green color, i.e., ATBF1 (Zfhx3) and Islet1), equally expressed in the LGE and dCGE (yellow color, i.e., Dlx genes), and preferentially expressed in the dCGE (red color, i.e., Arx, COUP-TFI (NR2F1), Mash1, Prox1, Sall3, Sox1, Sox4, and Sp9). We propose that 1) the TFs preferentially expressed in the LGE are important in development of striatal projection neurons and olfactory bulb interneurons; 2) the TFs preferentially expressed in the dCGE are important in development of cortical interneurons (subsets of neuropeptide-Y-, calretinin-, and vasoactive intestinal peptide-expressing pallial interneurons; see Zhao et al. 2008); and 3) TFs that are equally expressed in the LGE and dCGE have general roles in regulating the development of telencephalic γ-aminobutyric acidergic (GABAergic) neurons.

Within the dCGE, there is a VZ and a SVZ, but a MZ is not clearly distinct; this feature is exemplified by the expression of the Dlx genes whose combinatorial expression defines these 3 differentiation zones in the LGE and MGE (Fig. 1). At this point, it is unclear whether or not the CGE produces subpallial nuclei, although a caudal nucleus, such as the central nucleus of the amygdala, is a possibility (Carney et al. 2006; García-López et al. 2008).

It is possible that the CGE primarily consists of a large SVZ where pallial interneurons are produced and partially mature. In addition, many MGE-derived interneurons (Lhx6+) migrate through the CGE; it is possible that local CGE factors regulate their development; this idea is discussed below in the section of subpallial neuronal ectopia in the Dlx1&2−/− mutants.

Role of Dlx1&2 in dCGE Development

Dlx1&2 have a profound role in promoting differentiation of the dCGE, as exemplified by the reduced expression of Arx, Brn4, Dlx5, Dlx6, ESRG, FoxP4, Meis1, Meis2, Pbx1, Pbx3, Prox1, Six3, Sox4, Sox11, Sp8, Tle4, Tshz1, and Vax1 in the Dlx1&2−/− mutants.

These findings are similar to the phenotype of dLGE and septum, but not ventral parts of these primordia (Long et al. 2009). Thus, the dLGE and dCGE share similar dependence on Dlx1&2.

In the dLGE and dCGE, Dlx1&2 may have their strongest functions in the SVZ, as exemplified by reduced Sp9 expression in the SVZ and not in the VZ. Furthermore, Dlx1&2 are required to repress the expression of COUP-TFI, Ctip2, Mash1, and Sall3, supporting the model that Dlx1&2 promote the maturation of SVZ progenitors (see Yun et al. 2002; Long et al. 2007, 2009). Below we discuss the role of Mash1 in CGE development and the effect of removing Mash1 function in Dlx1&2−/− mutants. Elevated levels of antisense-Dlx6 transcripts are intriguing (Fig. 2), suggesting that the Dlx1&2 are required to repress this potential inhibitor of Dlx6 function (Faedo et al. 2004; Feng et al. 2006).

Several genes are ectopically expressed in the mutant dCGE, including markers of the MGE (Gsh1 and Gbx1), the ventral pallium (Id2 and Lmo1), dLGE (Ikaros and Islet1), and diencephalon (Otp) (Fig. 2). These results show that Dlx1&2 are required to specify the identity of dCGE progenitors, a finding that is also apparent in the dLGE (Long et al. 2009).

MGE TFs and the Function of Dlx1&2

Several TFs appear to preferentially, or exclusively, mark MGE progenitors and their derivatives: Cux2, ER81, Gbx1, Gbx2, Gsh1, Lhx6, Lhx7, Nkx2.1 (TTF-1), Nkx6.2, Prox1, ROR-beta, and TCF4. The MGE also shares molecular features with the LGE/dCGE, such as expression of Arx, Brn4 (POU3f4), Dlx1&2/5/6, Mash1, Sp9, and Vax1 (Figs 1 and 2; Flames et al. 2007).

The preoptic (POA) progenitor and mantle zones are rostroventral to the MGE (Flames et al. 2007) and express many of the same genes as the MGE but also have their distinct molecular features, including expression of COUP-TFI, Dbx1, Lhx2, Nkx5.1, Nkx5.2 (Hmx2 and Hmx3), and Nkx6.2 (Wang et al. 2004; Flames et al. 2007). Here we did not explicitly investigate the effect of the Dlx1/2 and Mash1 mutations on POA development.

Although regional identity of Dlx1&2−/− MGE does not appear to be greatly disturbed, its differentiation of the GP and pallial interneurons is impeded, perhaps secondary to increased notch signaling, as reflected by increased Mash1 and Hes5 expression (Fig. 2; see Yun et al. 2002). Increased expression of the Pak3 kinase has also been implicated in cytoskeletal dysregulation leading to premature neurite extension and inhibition of migration (Cobos et al. 2007).

Regional identity of the mutant MGE is probably preserved by the continued expression of Nkx2.1 (which may be increased; Fig. 2), a TF required from MGE specification (Sussel et al. 1999). However, despite preserved Nkx2.1 expression, expression of Cux2 and Lhx7(8) are clearly reduced (Fig. 1). Cux2 is expressed in tangentially migrating interneurons (Cobos et al. 2006), and its function is linked to the development of reelin-expressing interneurons (Cubelos et al. 2008). Lhx7(8) is expressed in the SVZ of the ventral MGE (Flames et al. 2007) and its derivatives in the pallidum and striatal interneurons where it is required for the cholinergic phenotype (Zhao et al. 2003; Mori et al. 2004; Fragkouli et al. 2005).

Lhx6 is expressed in MGE progenitors and in pallidal neurons, striatal interneurons, and pallial interneurons, and it promotes tangential migration, integration into the cortical plate, and differentiation of somatotstatin+ and parvalbumin+ interneurons (Sussel et al. 1999; Marin et al. 2000; Alifragis et al. 2004; Liodis et al. 2007; Zhao et al. 2008). Its expression is reduced in the MGE of the Dlx1&2−/− mutant (Fig. 1; Petryniak et al. 2007) and is reduced in the cortex, secondary to reduced interneuron migration (Cobos et al. 2006).

Here we report a large Lhx6+ ectopia in a superficial part of the dCGE (Fig. 1; Supplementary Fig. 2), suggesting that these cells correspond to interneurons that have failed to migrate to the cortex. However, this ectopia is also Nkx2.1+ (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. 2). As Nkx2.1 is not expressed in pallial interneurons (Sussel et al. 1999), this suggests several interesting possibilities, including the following: 1) Dlx1&2 are required to repress Nkx2.1 in interneurons—perhaps persistent Nkx2.1 expression contributes to the defect in tangential migration and 2) this ectopia could be a misplaced GP. We think that this hypothesis is less likely because the ectopia also expresses Nphx, a marker of tangentially migrating interneurons and not of the GP, and because the ectopia does not express the following GP markers: Arx, Dlx1, Gbx1, Lhx6, Lhx7(8), Oct6 (POU3F1), ROR-beta, TCF4, Tshz2, and Zfp521 (Evi30) (Fig. 1). There are other ectopia in the CGE and MGE that are located outside of the Lhx6/Nkx2.1/Nphx ectopia and that express ER81, ErbB4, NP2, Prox1, and Sox11 (Supplementary Fig. 2); these may correspond to distinct subtypes of neurons that failed to disperse (for NP2, see Marín et al. 2001).

Transcriptional and Neurogenic Pathways Downstream of Dlx1&2 and Mash1

We studied the expression of TFs and selected other genes in the MGE and CGE in Dlx1&2−/−, Mash1−/−, and Dlx1&2−/−;Mash1−/− mutants at E15.5, concentrating on genes whose expression persists in Dlx1&2−/− mutants (Supplementary Fig. 3). Expression of these genes fell into 4 general classes (Supplementary Table 3). Ongoing studies are aimed to establish whether these phenotypes are the result of direct transcriptional control. Several TFs continue to be expressed in the Dlx1&2−/−;Mash1−/− mutants, albeit generally at lower levels, in the CGE (Gsh1, Islet1, Olig2, and Sp9) and MGE (ER81, Islet1, Olig2, and Sp9) (Supplementary Fig. 3); in addition, GAD67 expression is weakly maintained. Thus, ER81, Gsh1, Islet1, Olig2, Sp9, or other TFs (i.e., Gsh2 or Nkx2.1) may be maintaining some of the fundamental features of the embryonic basal ganglia in the triple mutant. Furthermore, whereas some telencephalic cell types are reduced in Dlx1&2−/−, Mash1−/−, and Dlx1&2−/−;Mash1−/− mutants (striatal, pallidal, and pallial GABAergic, dopaminergic, and cholinergic neurons) (Marin et al. 2000; Long et al. 2007, 2009), oligodendrocyte generation is promoted (Petryniak et al. 2007). Finally, early stages of neurogenesis are dependent on Mash1 (i.e., Sox1), and not on Dlx1&2 (Supplementary Fig. 3). Thus, this analysis is beginning to dissect the complementary roles of Dlx1&2 and Mash1 in promoting the differentiation of the subpallium.

Non-TF Gene Dysregulation in Dlx1&2−/− Mutants

The subpallial progenitor zones produce GABAergic, cholinergic, and dopaminergic neurons, oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes. The Dlx genes are essential for the differentiation of many of these neurons (Marin et al. 2000; Yun et al. 2002; Long et al. 2007) and repress glial differentiation (Yun et al. 2002; Petryniak et al. 2007). We have begun to identify some of the key effector genes whose expression is downstream (directly/indirectly) of Dlx1&2. Supplementary Figure 2 shows some salient examples; others are described in Cobos et al. (2007) and Long et al. (2009).

Dlx1&2 promote GABAergic differentiation through promoting expression of the enzymes that synthesize GABA: GAD67 (Gad1) and GAD65 (Gad2) and the pump that concentrates GABA in synaptic vesicles (vGAT) (Supplementary Fig. 1; Anderson et al. 1999; Stühmer et al. 2002; Long et al. 2007, 2009; Eisenstat D, Cobos I and Rubenstein JLR, unpublished data).

Alterations in migration may be contributed by reduced expression of cytokine receptors (CXCR4 and CXCR7) and the neuregulin receptor, ErbB4. Migration defect may also be contributed by alterations in Gucy1a3, NP2, Robo2, Shb, Thbs, and Tiam2 expression (Supplementary Fig. 1). Defective differentiation of striatal and pallidal neurons is indicated by reduced expression of Cad8, Robo2, and Sema3a and several other genes (see Long et al. 2009).

Dlx1&2 repress several non-TFs in progenitor cells including Dact1 and PK2 (Supplementary Fig. 1; for additional genes, see Cobos et al. 2007 and Long et al. 2009); some of these are complementary to changes in the Mash1−/− mutant (Supplementary Fig. 3). These changes in progenitor properties are associated with persistent CyclinD2 expression in the LGE/dCGE SVZ (Supplementary Fig. 1) and elevated proliferation in the SVZ of the LGE/dCGE (Anderson, Qiu, et al. 1997). On the other hand, there is reduced CyclinD2 expression in the MGE SVZ, which is consistent with the reduce proliferation of this region (Anderson, Qiu, et al. 1997; Petryniak et al. 2007). We do not know why proliferation in the LGE/dCGE and MGE respond differently in the Dlx1&2−/− mutant.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary materials can be found at http://www.cercor.oxfordjournals.org/.

Funding

Nina Ireland; Larry L. Hillblom Foundation; National Institute of Mental Health RO1 MH49428-01; National Institute of Mental Health R37 MH049428-16A1; K05 MH065670 to JLRR; MIRG-CT-2007-210080; National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression Young Investigator Award to IC; National Institute of Mental Health F32 MH070211 to GBP.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Susan Yu for her help in putting the paper together. Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Alifragis P, Liapi A, Parnavelas JG. Lhx6 regulates the migration of cortical interneurons from the ventral telencephalon but does not specify their GABA phenotype. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5643–5648. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1245-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S, Mione M, Yun K, Rubenstein JL. Differential origins of neocortical projection and local circuit neurons: role of Dlx genes in neocortical interneuronogenesis. Cereb Cortex. 1999;9:646–654. doi: 10.1093/cercor/9.6.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SA, Eisenstat D, Shi L, Rubenstein JLR. Interneuron migration from basal forebrain: dependence on Dlx genes. Science. 1997;278:474–476. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SA, Qiu M, Bulfone A, Eisenstat D, Meneses JJ, Pedersen RA, Rubenstein JLR. Mutations of the homeobox genes Dlx-1 and Dlx-2 disrupt the striatal subventricular zone and differentiation of late-born striatal cells. Neuron. 1997;19:27–37. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80345-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt SJ, Fuccillo M, Nery S, Noctor S, Kriegstein A, Corbin JG, Fishell G. The temporal and spatial origins of cortical interneurons predict their physiological subtype. Neuron. 2005;48:591–604. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney RS, Alfonso TB, Cohen D, Dai H, Nery S, Stoica B, Slotkin J, Bregman BS, Fishell G, Corbin JG. Cell migration along the lateral cortical stream to the developing basal telencephalic limbic system. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11562–11574. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3092-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casarosa S, Fode C, Guillemot F. Mash1 regulates neurogenesis in the ventral telencephalon. Development. 1999;126:525–534. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.3.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro DS, Skowronska-Krawczyk D, Armant O, Donaldson IJ, Parras C, Hunt C, Critchley JA, Nguyen L, Gossler A, Göttgens B, et al. Proneural bHLH and Brn proteins coregulate a neurogenic program through cooperative binding to a conserved DNA motif. Dev Cell. 2006;11:831–844. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobos I, Borello U, Rubenstein JLR. Dlx transcription factors promote migration through repression of axon and dendrite growth. Neuron. 2007;54:873–888. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobos I, Broccoli V, Rubenstein JLR. The vertebrate ortholog of Aristaless is regulated by Dlx genes in the developing forebrain. J Comp Neurol. 2005;483:292–303. doi: 10.1002/cne.20405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobos I, Long JE, Thwin MT, Rubenstein JL. Cellular patterns of transcription factor expression in developing cortical interneurons. Cereb Cortex. 2006;(16):i82–i88. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhk003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo E, Collombat P, Colasante G, Bianchi M, Long J, Mansouri A, Rubenstein JLR, Broccoli V. Inactivation of Arx, the murine ortholog of the XLAG gene, leads to severe disorganization of the ventral telencephalon with impaired neuronal migration and differentiation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4786–4798. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0417-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubelos B, Sebastián-Serrano A, Kim S, Redondo JM, Walsh C, Nieto M. Cux-1 and Cux-2 control the development of Reelin expressing cortical interneurons. Dev Neurobiol. 2008;68:917–925. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faedo A, Quinn JC, Stoney P, Long JE, Dye C, Zollo M, Rubenstein JL, Price DJ, Bulfone A. Identification and characterization of a novel transcript down-regulated in Dlx1/Dlx2 and up-regulated in Pax6 mutant telencephalon. Dev Dyn. 2004;231:614–620. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Bi C, Clark BS, Mady R, Shah P, Kohtz JD. The Evf-2 noncoding RNA is transcribed from the Dlx-5/6 ultraconserved region and functions as a Dlx-2 transcriptional coactivator. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1470–1484. doi: 10.1101/gad.1416106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flames N, Gelman DM, Pla R, Rubenstein JLR, Puelles L, Marín O. Delineation of multiple subpallial progenitor domains by the combinatorial expression of transcriptional codes. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9682–9695. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2750-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fragkouli A, Hearn C, Errington M, Cooke S, Grigoriou M, Bliss T, Stylianopoulou F, Pachnis V. Loss of forebrain cholinergic neurons and impairment in spatial learning and memory in LHX7-deficient mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:2923–2938. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-López M, Abellán A, Legaz I, Rubenstein J, Puelles L, Medina L. Histogenetic compartments of the mouse centromedial and extended amygdala based on gene expression patterns during development. J Comp Neurol. 2008;506:46–74. doi: 10.1002/cne.21524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessaris N, Fogarty M, Iannarelli P, Grist M, Wegner M, Richardson WD. Competing waves of oligodendrocytes in the forebrain and postnatal elimination of an embryonic lineage. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:173–179. doi: 10.1038/nn1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liodis P, Denaxa M, Grigoriou M, Akufo-Addo C, Yanagawa Y, Pachnis V. Lhx6 activity is required for the normal migration and specification of cortical interneuron subtypes. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3078–3089. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3055-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JE, Garel S, Dolado M, Yoshikawa K, Osumi N, Zhou QY, Alvarez-Buylla A, Rubenstein JLR. Dlx-dependent and independent regulation of olfactory bulb interneuron differentiation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3230–3243. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5265-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JE, Swan C, Liang WS, Cobos I, Potter GB, Rubenstein JLR. Dlx1&2 and Mash1 transcription factors control striatal patterning and differentiation through parallel and overlapping pathways. J Comp Neurol. 2009;512:556–557. doi: 10.1002/cne.21854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Bendito G, Cautinat A, Sánchez JA, Bielle F, Flames N, Garratt AN, Talmage DA, Role LW, Charnay P, Marín O, et al. Tangential neuronal migration controls axon guidance: a role for neuregulin-1 in thalamocortical axon navigation. Cell. 2006;125:127–142. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin O, Anderson SA, Rubenstein JL. Origin and molecular specification of striatal interneurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6063–6076. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06063.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín O, Rubenstein JL. A long, remarkable journey: tangential migration in the telencephalon. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:780–790. doi: 10.1038/35097509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín O, Yaron A, Bagri A, Tessier-Lavigne M, Rubenstein JL. Sorting of striatal and cortical interneurons regulated by semaphorin-neuropilin interactions. Science. 2001;293:872–875. doi: 10.1126/science.1061891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi G, Butt SJ, Takebayashi H, Fishell G. Physiologically distinct temporal cohorts of cortical interneurons arise from telencephalic Olig2-expressing precursors. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7786–7798. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1807-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori T, Yuxing Z, Takaki H, Takeuchi M, Iseki K, Hagino S, Kitanaka J, Takemura M, Misawa H, Ikawa M, et al. The LIM homeobox gene, L3/Lhx8, is necessary for proper development of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:3129–3141. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petryniak MA, Potter GB, Rowitch DH, Rubenstein JL. Dlx1 and Dlx2 control neuronal versus oligodendroglial cell fate acquisition in the developing forebrain. Neuron. 2007;55:417–433. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleasure SJ, Anderson S, Hevner R, Bagri A, Marin O, Lowenstein DH, Rubenstein JLR. Cell migration from the ganglionic eminences is required for the development of hippocampal GABAergic interneurons. Neuron. 2000;28:727–740. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porteus MH, Bulfone A, Liu JK, Puelles L, Lo LC, Rubenstein JL. DLX-2, MASH-1, and MAP-2 expression and bromodeoxyuridine incorporation define molecularly distinct cell populations in the embryonic mouse forebrain. J Neurosci. 1994;14:6370–6383. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06370.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stühmer T, Anderson SA, Ekker M, Rubenstein JL. Ectopic expression of the Dlx genes induces glutamic acid decarboxylase and Dlx expression. Development. 2002;129:245–252. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.1.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussel L, Marin O, Kimura S, Rubenstein JLR. Loss of Nkx2.1 homeobox gene function results in a ventral to dorsal respecification within the basal telencephalon: evidence for a transformation of the pallidum into the striatum. Development. 1999;126:3359–3370. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.15.3359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Grimmer JF, Van De Water TR, Lufkin T. Hmx2 and Hmx3 homeobox genes direct development of the murine inner ear and hypothalamus and can be functionally replaced by Drosophila Hmx. Dev Cell. 2004;7:439–453. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonders CP, Anderson SA. The origin and specification of cortical interneurons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:687–696. doi: 10.1038/nrn1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Cobos I, Rubenstein JLR, Anderson SA. Origins of cortical interneuron subtypes. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2612–2622. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5667-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Tam M, Anderson SA. Fate mapping Nkx2.1-lineage cells in the mouse telencephalon. J Comp Neurol. 2008;506:16–29. doi: 10.1002/cne.21529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun K, Fischman S, Johnson J, Hrabe de Angelis M, Weinmaster G, Rubenstein JLR. Modulation of the notch signaling by Mash1and Dlx1&2 regulates sequential specification and differentiation of progenitor cell types in the subcortical telencephalon. Development. 2002;129:5029–5040. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.21.5029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Flandin-Blety P, Long JE, dela Cuesta M, Westphal H, Rubenstein JL. Distinct molecular pathways for development of telencephalic interneuron subtypes revealed through analysis of Lhx6 mutants. J Comp Neurol. 2008;510:79–99. doi: 10.1002/cne.21772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Marín O, Hermesz E, Powell A, Flames N, Palkovits M, Rubenstein JL, Westphal H. The LIM-homeobox gene Lhx8 is required for the development of many cholinergic neurons in the mouse forebrain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9005–9010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1537759100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.