Abstract

The purpose of the present study was to assess the clinical efficacy of radiofrequency (RF) cervical zygapophyseal joint neurotomy in patients with cervicogenic headache. A total of thirty consecutive patients suffering from chronic cervicogenic headaches for longer than 6 months and showing a pain relief by greater than 50% from diagnostic/prognostic blocks were included in the study. These patients were treated with RF neurotomy of the cervical zygapophyseal joints and were subsequently assessed at 1 week, 1 month, 6 months, and at 12 months following the treatment. The results of this study showed that RF neurotomy of the cervical zygapophyseal joints significantly reduced the headache severity in 22 patients (73.3%) at 12 months after the treatment. In conclusion, RF cervical zygapophyseal joint neurotomy has shown to provide substantial pain relief in patients with chronic cervicogenic headache when carefully selected.

Keywords: Cervicogenic Headache, Zygapophyseal Joint, Radiofrequency Neurotomy

INTRODUCTION

Cervicogenic headache, first described by Sjaastad (1), is characterized as unilateral fronto-temporal headache with clinical symptomatology similar to migraine (1, 2). Useful clinical diagnostic criteria were published in 1990 (3) and revised in 1998 (4). However, the concept of cervicogenic headache is not universally accepted, and the precise pathology in the neck that gives rise to the pain has not been completely understood. Among the candidate structures are the upper cervical nerves (greater and lesser occipital nerves), nerve roots, cervical muscles, cervical discs and zygapophyseal (facet) joints, and atlantoaxial and atlantooccipital joints. Cervicogenic headache may arise not only from the upper, but also from the middle and even from the lower cervical area (4). Various treatment modalities directed to these structures have been attempted. Among the published approaches, radiofrequency (RF) neurotomy of the cervical facet joints (5, 6) seems promising.

The purpose of the study was to assess the clinical efficacy of RF cervical zygapophyseal joint neurotomy in patients with chronic cervicogenic headache to determine whether there was sufficient merit or usefulness in the procedure to justify its use in these patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

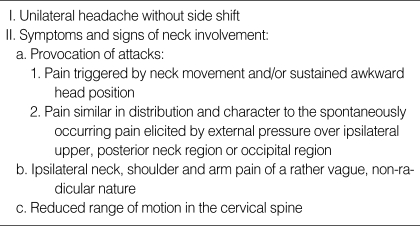

Patients were selected from the out patient clinic at our institution during the March 2001-February 2003 period. Major criteria for the diagnosis of cervicogenic headache are (modified criteria from 1990 [3]) listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Major criteria for diagnosis of cervicogenic headache

There were 46 with chronic (>6 months of duration) cervicogenic headache who met the above criteria. Among them, a total of thirty patients showed greater than 50% of pain relief from two diagnostic/prognostic C3-C4 cervical medial branch blocks and were followed up for more than 12 months. Those patients who needed multi-level cervical blocks and those who were involved in litigation or compensational programs were excluded. Selected patients had relatively severe complaints inhibiting activity of daily living, participation in work or social life, and inadequate effect of appropriate prophylactic and/or therapeutic headache medication. There were 16 men and 14 women ranging in age from 35 to 67 yr with a mean age of 54 yr. Radiographic examinations of the cervical spine were carried out in order to evaluate an abnormal posture or flexion-extension impairment. There were no definitive structural abnormalities that could cause neurologic deficits on computed tomogram or magnetic resonance imaging study of brain or cervical spine. These patients were treated with RF neurotomy on medial branch of posterior primary ramus and then were assessed at 1 week, 1 month, 6 months, and at 12 months following the treatment. All procedures were performed by a single neurosurgeon.

A RF generator (RFG-3C Graphic, Radionics Inc., Burlington, MA, U.S.A.) with the SMK-C10 cannula (22 gauge; length, 10 cm; exposed tip, 5 mm) was used with appropriate connections and a wide diathermy ground plate. All procedures were monitored by repeated radiographic screening with a C-arm image intensifier. Percutaneous RF neurotomy was performed under aseptic conditions, with the patient lying in the prone position. No sedation or systemic analgesic was used. The electrode was inserted parallel to the medial branch of the C3-C4 facet joint with a percutaneously posterolateral approach along a parasagittal plane, tangential to the lateral margin of the articular pillar, and was directed toward the target point under repeated C-arm image intensifier screening. The target point was a point of intersection of 2 lines diagonally drawn from supero-anterior and superoposterior to infero-posterior and infero-anterior articular pillar. The levels of lesioning were C3-C4 (Fig. 1). When the target point was reached, the position of the electrode was confirmed and recorded on anteroposterior and lateral films. Correct position was verified by stimulating current for both sensory and motor threshold. Usual thresholds for these were 0.3-0.9 V and 0.6-1.8 V, respectively. The target nerve was then anesthetized by the injection of 0.5 mL of 1% lidocaine before lesion production. Final lesion was generated at 80℃ for 90 sec. The average operative time was 19 min. Patients were discharged from the hospital after 1 to 2 hr of monitoring to see whether there were any discomforts or signs of complications. Follow-up visits were made at 1 week, 1 month, 6 months, and at 12 months. The followings were taken as outcome parameters: Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), number of headache-days per week and amount of analgesic intake per week. Results were defined as successful if preoperative pain was relieved by more than 75%.

Fig. 1.

The target point and C3-C4 lesioning. A point of intersection of 2 lines diagonally drawn from supero-anterior and superoposterior to infero-posterior and infero-anterior articular pillar.

RESULTS

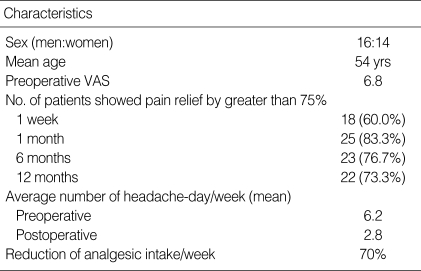

All patients well tolerated the procedure without additional analgesics or anesthetics. Eighteen (60%), 25 (83.3%), 23 (76.7%), and 22 (73.3%) patients showed pain relief by greater than 75% at 1 week, 1 month, 6 months, and at 12 months, respectively (Table 2). The average headache-days per week decreased from 6.2 days to 2.8 days, and the average analgesic intake per week showed a 70% reduction. There were no major complications related to the procedures. However, ataxia was seen in 4 patients immediately after the procedure, which was resolved completely within a few hours to 2 or 3 days. Three patients obtained short-lasting relief (3 months). None of the patients reported cutaneous numbness, dysesthesia, or worsening of pain. However, 12 patients complained of soreness on the posterior neck for 2-7 days following the procedures. These possible side effects were preoperatively explained to all patients and no specific measures were necessary except temporary oral analgesics for 2-5 days postoperatively. All such symptoms disappeared within a week. Interestingly, most of the patients showed definitive improvement after at least 2-4 weeks following the procedures. There were no instances of postoperative infection or other complications related to the procedures.

Table 2.

Characteristics of study subjects

VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

DISCUSSION

The term "cervicogenic headache" is denoted for the headache that originates from disorders of the neck (1). However, it is not a detailed description and is still controversial whether use of this term is appropriate as two currently major international organizations relevant to head pain, namely, the International Headache Society (IHS) and International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), disagree with the view point (7, 8).

Symptoms and signs of cervicogenic headache such as mechanical precipitation of attacks imply involvement of the neck. A reliable diagnosis of cervicogenic headache can be made based on the criteria established in 1990 and 1998 by the Cervicogenic Headache International Study Group (3, 4). Currently, positive response after an appropriate nerve block is an essential diagnostic feature of the disorder.

Pathologic conditions such as fractures, congenital abnormalities, bone tumors, rheumatoid arthritis, whiplash injury, and/or other distinct pathologies all may be related to the development of cervicogenic headache, but most authors believe that these conditions should be described as underlying pathologies, and those without definitive structural pathologies should only be regarded as primary cervicogenic headache. The authors used the diagnostic criteria from 1990 (3) as the clinical diagnostic tool, and confirmed the diagnosis by C3-C4 cervical medial branch block. Some authors recommend that when the diagnosis of cervicogenic headache is suspected, attempts should be made to confirm the diagnosis with the objective tests of cervical facet block and C2 nerve diagnostic blocks (4, 8, 9). Although many cervical structures are suggested as the cause of cervicogenic headache, most authors agree that upper cervical nerves are the main cause. Among the upper cervical structures, we believe that C3-C4 cervical medial branches are the main culprit. Based on anatomical innervation of these branches to the upper cervical and occipital region, these may cause neck pain and radiating pain to the posterior and temporal areas of the head. Bovim et al. reported that C2 nerve block seemed to be the most informative procedure and C4 and C5 nerve block was of little value in the work-up of cervicogenic headaches (9). Stovner et al. reported that RF neurotomy of facet joints C2-C6 was not beneficial in cervicogenic headache in a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled study (10). Other studies have shown what can be achieved if patients are carefully selected, using objective criteria under controlled conditions, and if meticulous surgical technique is used (6, 11-14). In a recent report of randomized controlled trial of treatment for cervicogenic headache (15), the authors did not find evidence that RF treatment of cervical facet joints and upper dorsal root ganglions was a better treatment than other conservative management. And in a recent review, Martelletti and van Suijlekom (16) concluded that a consensus on a standard treatment for cervicogenic headache does not exist because of the great variability in patient selection and clinical effects.

Anatomically, the cervical zygapophyseal joints are innervated by articular branches derived from the medial branches of the cervical dorsal rami (17). The C4-C8 dorsal rami arise from their respective spinal nerves just outside the intervertebral foramina and pass dorsally over the root of the ipsisegmental transverse process. The medial branches of the typical cervical dorsal rami are small (diameter, approximately 1 mm) and curve medially, hugging the waists of their ipsisegmental articular pillars, covered by the tendinous slips of the origin of the semispinalis capitis. Each typical cervical zygapophyseal joint receives a dual innervation, from the medial branch above and from the medial branch below its location. The medial branches of the C3 dorsal ramus differ in their anatomy from those of lower cervical levels. A deep medial branch passes around the waist of the C3 articular pillar in a manner analogous to that of typical medial branches; this branch participates in the innervation of the C3-C4 zygapophyseal joint. The superficial medial branch of C3 is large (diameter, approximately 1.5-2.0 mm) and is known as the third occipital nerve. It winds around the lateral aspect and then the posterior aspect of the C2-C3 zygapophyseal joint. Articular branches may also arise from a communicating loop that crosses the back of the joint between the third occipital nerve and the C2 dorsal ramus (17). Beyond the C2-C3 zygapophyseal joint, the third occipital nerve furnishes muscle branches to the semispinalis capitis and becomes cutaneous over the suboccipital region. In this respect, the C3 dorsal ramus is the only cervical dorsal ramus below C2 that regularly has a cutaneous distribution. Those from C4 to C7 typically lack any cutaneous branches (17). Therefore, on anatomical grounds, pain suspiciously resulting from the C2-C3 levels can be blocked by coagulating the ipsilateral third occipital nerve as it crosses the lateral aspect of the joint, and pain stemming below C2-C3 can be blocked by coagulating the cervical medial branches as they pass around the waists of the articular pillars above and below (18).

During the last decade, percutaneous RF neurotomy has been increasingly used in the treatment of chronic cervical pain and cervicobrachial pain. The rationale for this technique is that nociceptive transmission from the cervical zygapophyseal joint and muscles as well as ligaments can be blocked by coagulating the medial branches of the dorsal rami that innervate these structures (17, 18). At typical cervical levels, RF neurotomy achieves complete relief of pain, provided that patients have had complete relief of pain following diagnostic blocks for chronic cervical zygapophyseal joint pain (5, 17). Those blocks can be placebo-controlled or comparative local anesthetic blocks (11, 12). Similarly, for patients with headache mediated by the third occipital nerve, complete relief of pain can be achieved if meticulous and demanding techniques are followed (13). Because of many possible etiologies in cervicogenic headache, however, we believe that complete relief of pain is difficult to achieve, especially in chronic cases. Also, many authors agree that RF denervation of the C2-C3 facet joint procedure is technically difficult and does not guarantee good outcome (10, 17). Having these factors in mind, we selected the patients with C3-C4 cervical level lesion with good postoperative results.

Some authors reported a lengthy operation time to denervate just one joint and, to practice third occipital neurotomy, about 90 min (5, 13). They do not rely on a stimulation test for adjusting electrode tip. However, we believe that through a stimulation tests, both sensory and motor threshold, surgeons can confirm the exact location of the electrode tip and reduce operation time. Also, a lengthy operation not only gives rise to patient discomfort caused by the prone position, but also results in a higher dose of radiation exposure to both the patient and surgeon. Moreover, during the long operation, much needle manipulation may be necessary. In these cases, pain relief can be derived from other mechanisms including myofascial trigger point theory (14). Even with these adequate physiologic monitorings, the average duration of operation in our series was 19 min. The plane of insertion of electrodes is a critical factor. Electrodes must lie parallel to the nerve for the nerve to be incorporated in the radial lesion. Under these circumstances, however, the electrode must be within 2 mm of the nerve for adequate coagulation (18).

With these clinical, anatomical, and technical considerations, we undertook an audit of our experience with this procedure. The patients selected for the study were those who had significant pain relief without definitive complications or worsening of symptoms when diagnostic blocks were preoperatively performed under stringent, controlled conditions. The procedure was based on antecedent anatomical studies of the target nerves; electrodes were introduced parallel to the target nerves, and multiple lesions were made to incorporate the nerves. The limitations of this study lie in the fact that it was not a controlled, randomized study, and the number of subjects was small. Also, data from long-term follow-up evaluation was not included. However, this study included results from carefully selected patients with up to 12-month period of follow-up evaluation. Therefore, we believe it represents a moderate duration of pain relief without any serious side effects in the majority of these chronically disabling patients.

References

- 1.Sjaastad O, Saunte C, Hovdhal H, Breivik H, Grinbaek E. "Cervicogenic" headache. A hypothesis. Cephalalgia. 1983;3:249–256. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1983.0304249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fredriksen TA, Hovdal H, Sjaastad O. "Cervicogenic headache". Clinical manifestation. Cephalalgia. 1987;7:147–160. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1987.0702147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sjaastad O, Fredriksen TA, Pfaffenrath V. Cervicogenic headache: diagnostic criteria. Headache. 1990;30:725–726. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1990.hed3011725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sjaastad O, Fredriksen TA, Pfaffenrath V. Cervicogenic headache: diagnostic criteria. The Cervicogenic Headache International Study Group. Headache. 1998;38:442–445. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1998.3806442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lord SM, Barnsley L, Wallis BJ, McDornald GJ, Bogduk N. Percutaneous radio-frequency neurotomy for chronic cervical zygapophyseal-joint pain. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1721–1726. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612053352302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Suijlekom HA, van Kleef M, Barendse GA, Sluijter ME, Sjaastad O, Weber WE. Radiofrequency cervical zygapophyseal joint neurotomy for cervicogenic headache. A prospective study of 15 patients. Funct Neurol. 1998;13:297–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Cephalalgia. 1998;8(Suppl 7):1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) Cervicogenic Headache. In: Merskey H, Bogduk N, editors. Classification of Chronic Pain. Description of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of Pain Terms. 2nd ed. Seattle: IASP Press; 1994. pp. 94–95. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bovim G, Berg R, Dale LG. Cervicogenic headache: anesthetic blockades of cervical nerves (C2-C5) and facet joint (C2/C3) Pain. 1992;49:315–320. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90237-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stovner LJ, Kolstad F, Helde G. Radiofrequency denervation of facet joints C2-C6 in cervicogenic headache: a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled study. Cephalalgia. 2004;24:821–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2004.00773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lord SM, Barnsley L, Bogduk N. The utility of comparative local anaesthetic blocks versus placebo-controlled blocks for the diagnosis of cervical zygapophyseal joint pain. Clin J Pain. 1995;11:208–213. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199509000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnsley L, Lord S, Bogduk N. Comparative local anaesthetic blocks in the diagnosis of cervical zygapophyseal joints pain. Pain. 1993;55:99–106. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90189-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Govind J, King W, Bailey B, Bogduk N. Radiofrequency neurotomy for the treatment of third occipital headache. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiat. 2003;74:88–93. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.1.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaeger B. Are "cervicogenic" headaches due to myofascial pain and cervical spine dysfunction? Cephalalgia. 1989;9:157–164. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1989.0903157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haspeslagh SR, Van Suijlekom HA, Lame IE, Kessels AG, van Kleef M, Weber WE. Randomised controlled trial of cervical radiofrequency lesions as a treatment for cervicogenic headache [ISRCTN07444684] BMC Anesthesiol. 2006;6:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martelletti P, Van Suijlekom HA. Cervicogenic headache: practical approaches to therapy. CNS Drugs. 2004;18:793–805. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200418120-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bogduk N. The clinical anatomy of the cervical dorsal rami. Spine. 1982;7:319–330. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198207000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lord SM, Barnsley L, Bogduk N. Percutaneous radiofrequency neurotomy in the treatment of cervical zygapophyseal joint pain: a caution. Neurosurgery. 1995;36:732–739. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199504000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]